Abstract

Objective To investigate risks of recurrence of cerebral palsy in family members with various degrees of relatedness to elucidate patterns of hereditability.

Design Population based cohort study.

Setting Data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, linked to the Norwegian social insurance scheme to identify cases of cerebral palsy and to databases of Statistics Norway to identify relatives.

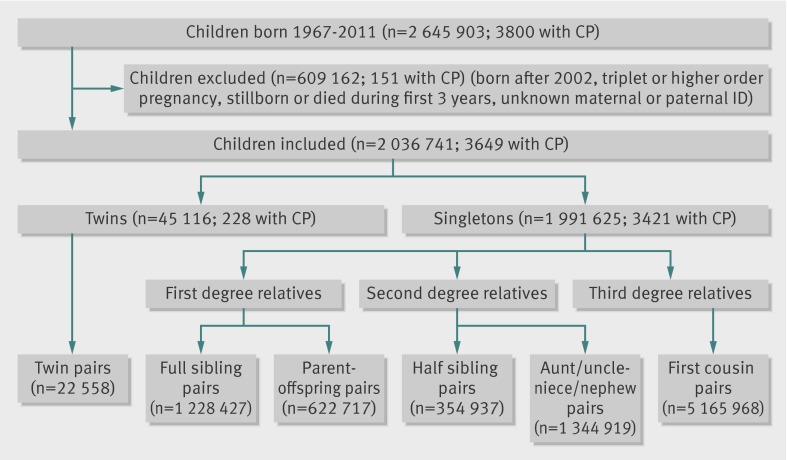

Participants 2 036 741 Norwegians born during 1967-2002, 3649 of whom had a diagnosis of cerebral palsy; 22 558 pairs of twins, 1 851 144 pairs of first degree relatives, 1 699 856 pairs of second degree relatives, and 5 165 968 pairs of third degree relatives were identified.

Main outcome measure Cerebral palsy.

Results If one twin had cerebral palsy, the relative risk of recurrence of cerebral palsy was 15.6 (95% confidence interval 9.8 to 25) in the other twin. In families with an affected singleton child, risk was increased 9.2 (6.4 to 13)-fold in a subsequent full sibling and 3.0 (1.1 to 8.6)-fold in a half sibling. Affected parents were also at increased risk of having an affected child (6.5 (1.6 to 26)-fold). No evidence was found of differential transmission through mothers or fathers, although the study had limited power to detect such differences. For people with an affected first cousin, only weak evidence existed for an increased risk (1.5 (0.9 to 2.7)-fold). Risks in siblings or cousins were independent of sex of the index case. After exclusion of preterm births (an important risk factor for cerebral palsy), familial risks remained and were often stronger.

Conclusions People born into families in which someone already has cerebral palsy are themselves at elevated risk, depending on their degree of relatedness. Elevated risk may extend even to third degree relatives (first cousins). The patterns of risk suggest multifactorial inheritance, in which multiple genes interact with each other and with environmental factors. These data offer additional evidence that the underlying causes of cerebral palsy extend beyond the clinical management of delivery.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy is the most common cause of physical disability in children, affecting approximately two in 1000 live births.1 Cerebral palsy comprises several more or less distinct subtypes with a wide spectrum of severity of motor disability, often accompanied by visual impairment, intellectual deficit, or epilepsy.2 A diagnosis cannot be reliably made until the age of at least 2 years,3 sometimes not until several years later for milder cases.4

Cerebral palsy originates from damage to the immature brain, the causes of which are still largely unknown. However, several risk factors in pregnancy and the perinatal period have been identified, among them preterm delivery, multiple fetuses, atypical intrauterine growth, intrauterine exposure to infection, placental pathology, congenital malformations, birth asphyxia, perinatal infection, and perinatal stroke.5 6 7 8 Previous studies have recognised a possible heritable component of cerebral palsy. The condition recurs more than expected among twins,9 10 11 as well as among siblings in general,12 13 14 15 and an excess risk of cerebral palsy in children with a parent or other family member affected by the condition has been reported.15 16 Several candidate genes or single nucleotide polymorphisms have been investigated to explain familial clustering of cerebral palsy,17 18 with extensions to interactions with clinical factors and other genes,19 although positive findings have proved hard to replicate.

We used data from a large population based cohort to systematically investigate recurrence of cerebral palsy among twins and first, second, and third degree relatives and thus to shed light on patterns of inheritance.

Methods

Data sources

The Central Population Registry of Norway was established in 1964 and was based on the national census of 1960.20 The registry assigns a unique 11 digit national identification number to each resident, together with a link to the parents’ identification numbers. The parental links are considered virtually complete for people born after 1954, which allows the construction of population based pedigrees. The unique personal identifier also permits record linkage among national registries.

Established in 1967, the Medical Birth Registry of Norway is based on compulsory notification of all live and still births in Norway from 16 weeks of gestation (and beginning in 2001, from 12 weeks).21 The birth registry includes information on maternal health, complications of pregnancy, plurality, gestational age, and the condition of the newborn. The birth registry is routinely linked to the population registry to obtain dates of death.

The Norwegian social insurance scheme provides cash benefits to families of children with chronic disease or disability, irrespective of family income.22 A basic benefit is provided if a child’s condition involves significant long term expenses and an attendance benefit if the child needs extra nursing. A disability pension can also be provided later in life to those unable to support themselves. The benefits are provided on the basis of a doctor’s diagnosis, coded in the insurance system in accordance with ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision) or ICD-10. We identified cases of cerebral palsy as people receiving benefits/disability pension on the basis of ICD-9 codes 342-344 or ICD-10 codes G80-G83. Using this strategy to identify cerebral palsy cases from the insurance system has previously been validated and found to be satisfactory.23 The insurance data were last updated in December 2007. We obtained data on education from Statistics Norway.

Study population and units of analyses

We excluded children born during 2003-11 to allow all affected cohort members a minimum of five years to be registered with a diagnosis of cerebral palsy (by the end of 2007, when the insurance data were last updated). The resulting study cohort consisted of 1 991 625 singletons and 45 116 twins born during 1967-2002 who survived at least three years and had known identification of both parents (figure). We used record linkage with the insurance system to identify cases of cerebral palsy and with the Central Population Registry relations and generations database to identify relatives within the cohort.

Selection of study population and identification of pairs of relatives

Using data from the birth registry, we linked 22 558 pairs of twins by identifying people who shared the same parents and whose dates of birth were no more than one day apart. To investigate recurrence of cerebral palsy among first degree relatives, we linked singleton births with the same mothers and fathers, thus identifying 1 228 427 unique full sibling singleton pairs, with each pair contributing only once. We also identified the first two children in sibships with two (or more) singletons, providing 620 309 full sibling pairs of first and second births. Next, we identified all members of the birth cohort who had subsequently become a parent of at least one other cohort member, constructing 372 198 mother-offspring pairs and 250 519 father-offspring pairs. To investigate recurrence among second degree relatives, we identified 152 496 half sibling singleton pairs within the cohort who had the same mother but different fathers and 202 441 pairs with the same father but different mothers, with each pair contributing only once. We also identified a total of 114 551 half sibling pairs by selecting the first two in sibships with two (or more) half siblings. In addition, we identified 1 344 919 aunt/uncle-niece/nephew singleton pairs These were pairs in which one set of grandparents of the niece/nephew was identical to the parents of the aunt/uncle, excluding parent-offspring pairs. To investigate recurrence among third degree relatives, we identified a total of 5 165 968 unique first cousin pairs, identified as people sharing one set of grandparents but not sharing a parent.

Statistical methods

For the analysis of twins, we identified twin pairs concordant for cerebral palsy (both members with the condition) and those discordant for cerebral palsy (one affected and one unaffected). No obvious way exists to assign the “exposure” of cerebral palsy to one twin and the “outcome” of cerebral palsy to the other. In this setting, the preferred calculation is the proband-wise concordance rate, which is analogous to the absolute recurrence risk in siblings.24 This concordance rate is calculated as follows: (No of concordant pairs × 2) divided by ((No of concordant pairs × 2) + (No of discordant pairs)). We then estimated the relative risk of recurrence in twins as the proband-wise concordance rate divided by the prevalence of cerebral palsy in the twin population.

The Norwegian twin data do not include information on zygosity. We indirectly explored the role of zygosity by repeating our twin analysis with stratification by like-sex and unlike-sex status, with the rationale that all unlike-sex twin pairs are dizygous, whereas like-sex twins are a mix of monozygous and dizygous twins.

In sibling and cousin pairs, we considered cerebral palsy status in the older person to be the “exposure,” and the status of the younger person was the “outcome.” We estimated relative risks of recurrence as the absolute risk of cerebral palsy in cohort members at risk (younger sibling, offspring, niece/nephew, or younger first cousin of affected person) divided by the absolute risk of cerebral palsy in the reference population (younger sibling, offspring, niece/nephew, or younger first cousin of unaffected person). We investigated the associations between exposure and outcome in log-binomial regression models, using Intercooled Stata version 12.1. In sibling analyses, we adjusted for the following potential confounding factors, on the basis of the possibility that they could be causes of cerebral palsy in both siblings: parental educational level (less than high school, high school, more than high school) as a marker of social status, parental age at birth of first sibling (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, ≥35, extended to 35-39, 40-44, ≥45 for fathers), and time period of first delivery (1967-71, 1972-77, 1978-84, 1985-91, 1992-2002). Parental educational level was missing in approximately 1% of sibling pairs. Results of analyses without these pairs were very similar to those when we used a separate category for missing education in the models. In all analyses, we used robust estimations of variances to account for correlations between pairs of siblings and parent-offspring by the same parents, pairs of aunt/uncle-niece/nephew by the same aunt/uncle, and pairs of first cousins sharing the same grandparents. We tested for interactions between cerebral palsy status and sex of the index relative by including interaction terms in the models. We used χ2 tests to test for differences in proportions.

The role of genetics in cerebral palsy might differ between children born preterm and those born at term.5 We therefore did a sub-analysis with stratification according to preterm (23-36 weeks) and term (37-44 weeks) gestational ages of both relatives, excluding the 145 275 cohort members with missing gestational age or with unlikely gestational ages (as determined by birth weight at least three standard deviations from the mean for gestational age).25 Only pairs of relatives in which both had reached term (37-44 weeks) had sufficient numbers for analysis.

To investigate the possibility of differential transmission through mothers or fathers, we stratified analyses by sex of parent in parent-offspring and half sibling analyses and by type of cousin relationship in first cousin analyses (shared maternal grandparents, shared paternal grandparents, or maternal grandparents of one were paternal grandparents of the other) and included interaction terms in statistical models.

We assessed to what degree a diagnosis of cerebral palsy affected reproduction by comparing the rates of parenthood among adults affected with cerebral palsy with rates in unaffected adults. We also investigated whether having a first born singleton with cerebral palsy affected the parents’ probability of having a second child.

Results

The prevalence of cerebral palsy registered in the insurance system was 1.8 per 1000 for children born during 1967-2002 (figure). The rate was higher in twins (5.1 per 1000) than in singletons (1.7 per 1000).

The cohort contained 22 558 sets of twins in which both survived at least three years. Nine pairs were concordant for cerebral palsy and 210 pairs were discordant, yielding an overall proband-wise concordance rate of 7.9%. When we stratified twins by like-sex and unlike-sex, the proband-wise concordance rates were 8.3% for like-sex and 6.7% for unlike-sex pairs (P for difference=0.68). The overall relative recurrence risk of cerebral palsy among twins was 15.6 (95% confidence interval 9.8 to 24.8) (table 1).

Table 1.

Recurrence of cerebral palsy (CP) among relatives. Singletons and twins born in Norway 1967-2002 surviving first three years of life

| Relatives | Prevalence of CP (per 1000) | Relative risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | ||

| Twins | |||

| Prevalence in twin population | 228/45 116 (5.1) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Proband-wise concordance rate | 18/228 (78.9) | 15.6 (9.8 to 24.8) | — |

| First degree | |||

| Full siblings: | |||

| Sibling without CP | 1929/1 226 413 (1.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Sibling with CP | 30/2014 (14.9) | 9.5 (6.6 to 13.5) | 9.2 (6.4 to 13.1)* |

| Parent-offspring: | |||

| Parent without CP | 813/622 480 (1.3) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Parent with CP | 2/237 (8.5) | 6.5 (1.6 to 25.6) | — |

| Second degree | |||

| Half siblings: | |||

| Half sibling without CP | 762/354 163 (2.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Half sibling with CP | 5/774 (6.5) | 3.0 (1.2 to 7.2) | 3.0 (1.1 to 8.6)† |

| Aunt/uncle-niece/nephew: | |||

| Aunt/uncle without CP | 1930/1 342 559 (1.4) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Aunt/uncle with CP | 3/2360 (1.3) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.7) | — |

| Third degree | |||

| First cousin with CP | 8472/5 156 811 (1.6) | 1 (reference) | — |

| First cousin without CP | 23/9157 (2.5) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.7) | — |

*Adjusted for maternal age at birth of older sibling (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, ≥35), maternal educational level (below high school, high school, above high school), and period of first birth (1967-71, 1972-77, 1978-84, 1985-91, 1992-2002).

†Adjusted for parental age at birth of older sibling (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, ≥35 for mothers, extended to 35-39, 40-44, ≥45 for fathers), parental educational level (below high school, high school, above high school), and period of first birth (1967-71, 1972-77, 1978-84, 1985-91, 1992-2002).

Among full siblings (first degree relatives), the absolute recurrence risk of cerebral palsy was 14.9 per 1000—a 9.2 (6.4 to 13.1)-fold excess risk in younger siblings of affected people compared with siblings of unaffected people (table 1). Sex of the index case did not affect relative recurrence risk (P for interaction=0.78). Excess risk was practically unchanged when we restricted the analysis to the first two siblings (9.9 (5.9 to 16.6)-fold). The 151 parents who were themselves affected by cerebral palsy had a total of 237 children, of whom two had cerebral palsy. This represents a 6.5 (1.6 to 25.6)-fold excess risk compared with parents not affected by cerebral palsy (table 1). Both affected children were born to mothers with cerebral palsy (none to fathers with cerebral palsy). These numbers are too small for us to be able to interpret possible difference in transmission between mothers and fathers (P for interaction=0.98).

Among half siblings (who are second degree relatives), the estimated relative recurrence risks were approximately 3.0 (1.1 to 8.6)-fold (table 1). Results did not differ between maternal and paternal half siblings (P for interaction=0.93). Excess risk was similar when we restricted analyses to the first two siblings (3.7 (0.9 to 14.9)-fold). We found no evidence of excess risk of cerebral palsy in people with an aunt or uncle affected by cerebral palsy (also second degree relatives). Relative recurrence risk was higher for half siblings than for uncle/aunt-niece/nephew pairs, but with limited statistical evidence of a real difference (P for interaction between type of second degree relative and cerebral palsy risk=0.09).

Among third degree relatives (5.1 million unique pairs of first cousins), we found a 1.5 (0.9 to 2.7)-fold increased risk in younger first cousins of a person with cerebral palsy (table 1). This risk was higher (2.8 (1.0 to 7.4)-fold) if the cousins shared paternal grandparents (that is, if their fathers were brothers), although this difference may have occurred by chance (P for interaction=0.10). The sex of the index case did not affect relative recurrence risk among first cousins (P for interaction=0.34).

The risk of cerebral palsy is well known to be greater among preterm infants, which suggests that some of the causes of cerebral palsy in people born preterm may differ from the causes among those born at term. When we restricted analyses to pairs of relatives in which both reached term (37-44 weeks), the relative recurrence risks were generally not attenuated (table 2).

Table 2.

Recurrence of cerebral palsy (CP) among term born relatives (37-44 weeks gestational age). Singletons born in Norway 1967-2002, surviving first three years of life

| Relatives | Prevalence of CP (per 1000) | Relative risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | ||

| First degree | |||

| Full siblings: | |||

| Sibling without CP | 1128/977 707 (1.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Sibling with CP | 16/1185 (13.5) | 11.7 (7.2 to 19.1) | 11.4 (7.0 to 18.5)* |

| Parent-offspring: | |||

| Parent without CP | 427/494 403 (0.9) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Parent with CP | 2/140 (14.3) | 16.5 (4.2 to 64.9) | — |

| Second degree | |||

| Half siblings: | |||

| Half sibling without CP | 308/258 818 (1.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Half sibling with CP | 1/410 (2.4) | 2.0 (0.3 to 14.6) | 2.0 (0.3 to 14.4)† |

| Aunt/uncle-niece/nephew: | |||

| Aunt/uncle without CP | 1002/1 059 936 (0.9) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Aunt/uncle with CP | 2/1505 (1.3) | 1.4 (0.4 to 5.6) | — |

| Third degree | |||

| First cousin with CP | 4493/3 998 069 (1.1) | 1 (reference) | — |

| First cousin without CP | 14/5053 (2.8) | 2.5 (1.1 to 5.7) | — |

*Adjusted for maternal age at birth of older sibling (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, ≥35), maternal educational level (below high school, high school, above high school), and period of first birth (1967-71, 1972-77, 1978-84, 1985-91, 1992-2002).

†Adjusted for parental age at birth of older sibling (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, ≥35 for mothers, extended to 35-39, 40-44, ≥45 for fathers), parental educational level (below high school, high school, above high school), and period of first birth (1967-71, 1972-77, 1978-84, 1985-91, 1992-2002).

Only 11% of the 2885 people with cerebral palsy born before 1992 had themselves become a parent by 2011, compared with 51% of the 1.4 million who were unaffected. Among the 1590 women who had a first born singleton affected by cerebral palsy during 1967-97, 68% (1079) had another singleton by 2003, compared with 73% (616 101) of the 840 225 women who had a first born singleton unaffected by cerebral palsy. Thus, having a first born child with cerebral palsy reduced the chance of having a subsequent child by 7% (relative risk 0.93, 0.89 to 0.96).

Consanguinity is relevant in an analysis of familial risk. However, our data included too few consanguineous relations for us to be able to detect possible effects on relative risks of recurrence.

Discussion

We used national registries and linkages among families in Norway to identify 3649 cases of cerebral palsy among two million births. This resource allowed us to estimate the familial risk of cerebral palsy across a broad range of family relationships. We found a 15-fold increased risk of cerebral palsy among co-twins of cerebral palsy cases, a sixfold to ninefold increased risk among first degree relatives of a person with cerebral palsy, an up to threefold increased risk among second degree relatives, and a 1.5-fold increased risk among third degree relatives. Relative recurrence risks were apparently independent of the sex of the index case and persisted when analyses were restricted to term births.

Comparison with other studies

Other studies have suggested a familial risk for cerebral palsy, although none has considered the full range of family relationships within a single population. Studies on multiple births have reported prevalences of cerebral palsy in twins similar to ours.9 10 11 Two twin studies noted similar prevalence in like-sex and unlike-sex pairs,9 10 although their small numbers of pairs concordant for cerebral palsy did not allow comparison of proband-wise concordance rates.

The largest previous study of cerebral palsy in siblings was based in a Swedish registry including almost 4000 cases.14 Among singleton siblings, a 4.8-fold increased risk of recurrence of hospital admission for cerebral palsy was seen. An Australian case-control study comprising almost 600 cases reported an odds ratio of 4 for cerebral palsy among siblings of cerebral palsy cases.15 Our estimate of the relative recurrence risk for cerebral palsy among siblings is considerably higher (ninefold) than these earlier estimates. However, none of these previous studies was able to distinguish recurrence among full and half siblings. If we pool our sibling data, the relative recurrence risk is reduced to 7.4. Also, our full linkage of registered cerebral palsy cases from insurance data may have provided more complete description of familial risk.

We have identified only one previous study investigating recurrence of cerebral palsy from parents to offspring. In a British study from 1992, 88 respondents with congenital cerebral palsy had 122 children, of whom two had cerebral palsy (16 per 1000).16 We found two affected cases among 237 children of parents themselves affected by cerebral palsy (8 per 1000).

We know of no other study that has systematically estimated risk for second or third degree relatives. An Australian case-control study reported a 1.7-fold increased risk of cerebral palsy for a child with a “more distant” relative with cerebral palsy,15 which is comparable to our finding of a 1.5 relative recurrence risk among third degree relatives.

Study strengths and limitations

No previous study has provided a population based survey of the range of familial risks for cerebral palsy. The uniform ascertainment of cases within a well established population constitutes a major strength of this study. The estimation of risks within a single study also makes the pattern of stronger recurrence among closer relatives more interpretable, being less susceptible to bias from alternative methods of case ascertainment in diverse smaller studies.

Another strength of the study is the ability to adjust for characteristics of the family (including parental age, educational level, and time period) by using registry information. That such adjustments had little effect on the relative recurrence risk estimates is reassuring, suggesting that residual confounding by measured variables was not a serious problem. We cannot, of course, exclude the possibility of confounding by unmeasured variables.

A major limitation of the study is the lack of information on cerebral palsy subtypes. Different subtypes may have different causes.5 Although the ICD-9/10 diagnoses in the Norwegian insurance system contain some subtype information, more than 90% of cases were coded “unspecified cerebral palsy.” In a Swedish registry study,14 sibling recurrence risks tended to be specific to the subtype. Our estimates of relative recurrence risk might have been even higher for specific subtypes if we had been able to identify them.

Another limitation is our inability to identify cases of cerebral palsy with post-neonatal causes. Although these cases could in principle bias our results, they are estimated to constitute only about 6% of our cases,26 and their practical consequence is slight.

Selective fertility probably affects the observed recurrence risks. For example, only 11% of people with cerebral palsy who were 19 or older had themselves become parents, compared with 51% of unaffected people. This observation might be related to biological factors, but it is even more likely to be influenced by social challenges among people with impairments such as cerebral palsy, which limit opportunities to develop relationships.27 Those who do participate socially, and thus have a chance of become parents themselves, have less severe motor and intellectual impairments.27 To the extent that the genetic contribution to cerebral palsy is stronger for more severe cases, the observed recurrence risk from parent to child would be biased towards lower risks. Likewise, having a first born child with cerebral palsy reduced a mother’s probability of having a second child by 23%. Parents of the most serious cases are probably more likely to refrain from having more children owing to the burden of care, again biasing the observed familial risk downward. Recurrence risk may be further underestimated by the failure to identify babies who ultimately would have been diagnosed as having cerebral palsy but were stillborn or died before the age of 3 years.

Cerebral palsy identified through the insurance system has been validated.23 Nevertheless, we are likely to have missed milder cases, who might be less likely to apply for benefits. Having one family member with cerebral palsy may raise awareness of one’s lawful rights, so that benefits are also claimed for milder cases. This could result in a differential misclassification leading to a strengthening of the observed associations. The fact that healthcare in Norway is free of charge and universally accessible reduces this concern somewhat.

We could not take into account the possible role of birth asphyxia in the recurrence of cerebral palsy, as the medical birth registry does not contain information on acid/base status of the newborn. However, as birth injury is believed to contribute to only a relatively small proportion of cerebral palsy cases,4 this is probably not a major concern.

Interpretation of results

The pattern of stronger associations in more closely related family members points to a genetic cause,28 but this is not the only possible interpretation. Aggregation of conditions within families can also reflect a shared environment or shared interactions between genes and environment.29 The “dose-response” relation, from a 15-fold increased risk among twins to a 1.5-fold increased risk among third degree relatives, is compatible with multifactorial inheritance, in which several genes act in concert with each other and with the environment to produce the phenotype.30 It is, however, important to keep in mind that our measures of familial risk may not be generalisable to genetically different populations.

For a doctor counselling a pregnant woman, our findings imply an excess risk of cerebral palsy if cases of cerebral palsy exist in her family—the closer the relationship between the unborn child and the affected relative, the higher the risk. However, the risk remains low in absolute terms (table 1), and this fact should also be communicated. To the extent that the observed patterns of familial risk reflect genetic causes of cerebral palsy, they offer additional evidence that the underlying causes extend beyond clinical management of delivery.

Not all associations fit the expectation of familial risk. For example, aunt/uncle-niece/nephew relationships (which are second degree) showed no increased risk of cerebral palsy, whereas half siblings (also second degree) did. This could reflect a lack of power to identify small risks. Also, in the presence of an affected co-twin, like-sex twins had only a slightly higher risk of cerebral palsy than did unlike-sex twins, despite the fact that like-sex twins on average share more genes than unlike-sex twins. In the setting of a multiple pregnancy, the high risks associated with factors such as preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and the ill health of one twin affecting the other may all overshadow the genetic risk.

Preterm birth is also a strong risk factor for cerebral palsy in singletons. Given that preterm delivery tends to be repeated in sibships,31 we expected the risk of cerebral palsy recurrence to be higher if the older sibling with cerebral palsy was born preterm. In fact, we observed the opposite: relative recurrence risks were generally higher when both relatives were born at or close to term. If preterm cerebral palsy is more often caused by prematurity itself, a term born child with cerebral palsy might be more strongly related to genetic risk, which would repeat more often among its (term-born) relatives.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that cerebral palsy includes a genetic component, with a stronger recurrence among relatives with closer genetic relationship. This offers additional evidence that the underlying causes of cerebral palsy extend beyond the clinical management of delivery. However, the similar risks of cerebral palsy of co-twins of affected like-sex and unlike-sex twin pairs suggest that genetic influences are only part of a wide range of causes. In pursuing the enigma of cerebral palsy, future aetiological studies should consider the possibility of genetic causes as well as genetic susceptibility to environmental causes.

What is already known on this topic

Cerebral palsy is most often caused by in utero brain injury, but what inflicts the damage is usually not known

What this study adds

These data suggest that cerebral palsy includes a genetic component, with a stronger recurrence among relatives with closer genetic relationship

This offers additional evidence that the underlying causes of cerebral palsy extend beyond the clinical management of delivery

Contributors: MCT analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AJW and RTL reviewed the analyses and drafts of the manuscript and provided critical comments. DM proposed the study, reviewed the analyses and drafts of the manuscript, and provided critical comments. All the authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. MCT is the guarantor.

Funding: The study has been supported by grants from the University of Bergen and the Western Norway Regional Health Authority and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The authors’ institutions had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from the University of Bergen, the Western Norway Regional Health Authority and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2010/2949-6), as well as the individual registry owners (the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration, the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Statistics Norway, and the tax administration).

Transparency declaration: The lead author (MCT) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g4294

References

- 1.Prevalence and characteristics of children with cerebral palsy in Europe. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;44:633-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:8-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paneth N. Establishing the diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008;51:742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanley F, Blair E, Alberman E. Cerebral palsies: epidemiology and causal pathways: Mac Keith Press, 2000.

- 5.Nelson KB. Causative factors in cerebral palsy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008;51:749-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair E, Watson L. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;11:117-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2008;359:262-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntyre S, Taitz D, Keogh J, Goldsmith S, Badawi N, Blair E. A systematic review of risk factors for cerebral palsy in children born at term in developed countries. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:499-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petterson B, Nelson KB, Watson L, Stanley F. Twins, triplets, and cerebral palsy in births in Western Australia in the 1980s. BMJ 1993;307:1239-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grether JK, Nelson KB, Cummins SK. Twinning and cerebral palsy: experience in four northern California counties, births 1983 through 1985. Pediatrics 1993;92:854-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Li Z, Lin Q, Zhao P, Zhao F, Hong S, et al. Cerebral palsy and multiple births in China. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustavson KH, Hagberg B, Sanner G. Identical syndromes of cerebral palsy in the same family. Acta Paediatr Scand 1969;58:330-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Naarden Braun K, Autry A, Boyle C. A population-based study of the recurrence of developmental disabilities—Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program, 1991-94. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005;19:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. High familial risks for cerebral palsy implicate partial heritable aetiology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2007;21:235-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Callaghan ME, MacLennan AH, Gibson CS, McMichael GL, Haan EA, Broadbent JL, et al. Epidemiologic associations with cerebral palsy. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:576-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley J. The offspring of people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1992;34:972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Callaghan ME, Maclennan AH, Gibson CS, McMichael GL, Haan EA, Broadbent JL, et al. Fetal and maternal candidate single nucleotide polymorphism associations with cerebral palsy: a case-control study. Pediatrics 2012;129:e414-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Callaghan ME, MacLennan AH, Haan EA, Dekker G. The genomic basis of cerebral palsy: a HuGE systematic literature review. Hum Genet 2009;126:149-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Callaghan ME, Maclennan AH, Gibson CS, McMichael GL, Haan EA, Broadbent JL, et al. Genetic and clinical contributions to cerebral palsy: a multi-variable analysis. J Paediatr Child Health 2013;49:575-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammer H. Det sentrale folkeregister i medisinsk forsning “The Central Population Registry in medical resarch”. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2002;122:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway: epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:435-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norwegian Social Insurance Scheme 2014. www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/asd/dok/veiledninger_brosjyrer/2014/det-norske-trygdesystemet-2014.html?id=716026.

- 23.Moster D, Lie RT, Irgens LM, Bjerkedal T, Markestad T. The association of Apgar score with subsequent death and cerebral palsy: a population-based study in term infants. J Pediatr 2001;138:798-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGue M. When assessing twin concordance, use the probandwise not the pairwise rate. Schizophr Bull 1992;18:171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skjaerven R, Gjessing HK, Bakketeig LS. Birthweight by gestational age in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:440-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen GL, Irgens LM, Haagaas I, Skranes JS, Meberg AE, Vik T. Cerebral palsy in Norway: prevalence, subtypes and severity. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2008;12:4-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan SS, Wiegerink DJ, Vos RC, Smits DW, Voorman JM, Twisk JW, et al. Developmental trajectories of social participation in individuals with cerebral palsy: a multicentre longitudinal study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoury MJ, Beaty TH, Liang KY. Can familial aggregation of disease be explained by familial aggregation of environmental risk factors? Am J Epidemiol 1988;127:674-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo SW. Familial aggregation of environmental risk factors and familial aggregation of disease. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:1121-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tissot R. Human genetics for 1st year students: multifactorial inheritance. www.uic.edu/classes/bms/bms655/lesson11.html.

- 31.Melve KK, Skjaerven R, Gjessing HK, Oyen N. Recurrence of gestational age in sibships: implications for perinatal mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:756-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]