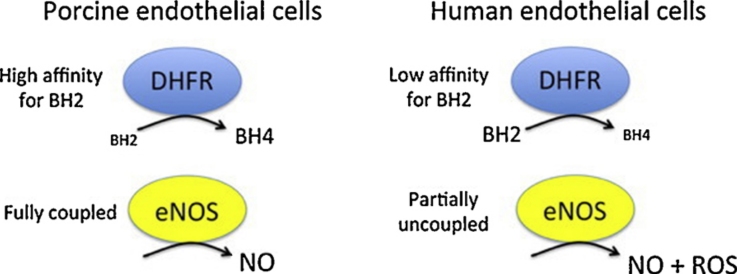

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: amino-BH4, 4-amino-(6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-l-biopterin; BAECs, bovine aortic endothelial cells; BH2, 7,8-dihydro-l-biopterin; BH4, (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-l-biopterin; cGMP, 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate; DAHP, 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine; DEA/NO, 2,2-diethyl-1-nitroso-oxyhdrazine; DHF, 7,8-dihydrofolate; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GTPCH, guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; l-NMA, NG-methyl-l-arginine; l-NNA, NG-nitro-l-arginine; NO, nitric oxide; PAECs, porcine aortic endothelial cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species; THF, 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate

Keywords: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling, Tetrahydrobiopterin recycling, Dihydrofolate reductase, Porcine endothelial cells, Human endothelial cells

Abstract

(6R)-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-l-biopterin (BH4) availability regulates nitric oxide and superoxide formation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). At low BH4 or low BH4 to 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2) ratios the enzyme becomes uncoupled and generates superoxide at the expense of NO. We studied the effects of exogenously added BH2 on intracellular BH4/BH2 ratios and eNOS activity in different types of endothelial cells. Incubation of porcine aortic endothelial cells with BH2 increased BH4/BH2 ratios from 8.4 (controls) and 0.5 (BH4-depleted cells) up to ∼20, demonstrating efficient reduction of BH2. Uncoupled eNOS activity observed in BH4-depleted cells was prevented by preincubation with BH2. Recycling of BH4 was much less efficient in human endothelial cells isolated from umbilical veins or derived from dermal microvessels (HMEC-1 cells), which exhibited eNOS uncoupling and low BH4/BH2 ratios under basal conditions and responded to exogenous BH2 with only moderate increases in BH4/BH2 ratios. The kinetics of dihydrofolate reductase-catalyzed BH4 recycling in endothelial cytosols showed that the apparent BH2 affinity of the enzyme was 50- to 300-fold higher in porcine than in human cell preparations. Thus, the differential regulation of eNOS uncoupling in different types of endothelial cells may be explained by striking differences in the apparent BH2 affinity of dihydrofolate reductase.

1. Introduction

The pterin derivative tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is essential for endothelial NO formation. It binds to endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in immediate vicinity of the heme and promotes the transfer of electrons from the reductase domain to the heme group, where oxygen is reduced and incorporated into the guanidine group of the substrate, l-arginine. At subsaturating concentrations of BH4, autoxidation of the ferrous-oxy and ferrous-superoxy complexes results in release of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide at the expense of the l-citrulline and NO [1]. This phenomenon, referred to as eNOS uncoupling, has been implicated in endothelial dysfunction associated with a variety of cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis, hypertension and diabetes [2–4]. Over the past several years, evidence has accumulated that in addition to BH4 levels, the intracellular ratio of BH4 vs. its oxidation product, dihydrobiopterin (BH2), also determines endothelial function. BH2 competes with BH4 for binding to eNOS but does no provide electrons for reductive oxygen activation [5–7]. Accordingly, eNOS uncouples at low BH4/BH2 ratios even at sufficiently high BH4 concentrations.

Intracellular levels of BH4 and BH4/BH2 ratios are controlled by de novo and salvage pathways [8,9]. Guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH) is the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the de novo biosynthetic pathway. It catalyzes the hydrolysis of GTP to 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate, which is then converted to BH4 by the consecutive action of 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase and sepiapterin reductase. GTPCH activity, and thus de novo synthesis of BH4 is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level by several cytokines and hormones, which either up- or down-regulate GTPCH expression levels, as well as by posttranslational modifications and by interaction of GTPCH with its feedback regulatory protein. Moreover, GTPCH activity can be efficiently inhibited by 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine (DAHP), a pharmacological tool used for the depletion of cellular BH4.

In addition to its de novo biosynthesis, BH4 can be enzymatically regenerated from its oxidation products quinonoid 6,7-[8H]-dihydrobiopterin and 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2) by dihydropteridine reductase and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), respectively. While the role of dihydropteridine reductase in maintaining endothelial function is unclear (the quinonoid 6,7-[8H]-dihydrobiopterin rearranges non-enzymatically to BH2, which is then reduced to BH4 by DHFR), inhibition or knockout of DHFR in cultured endothelial cells has been shown to reduce intracellular BH4:BH2 ratios and NO/l-citrulline formation [10–12], hinting at a critical role of DHFR in regulating eNOS uncoupling. More recently the results obtained with cultured cells have been corroborated by in vivo experiments showing that treatment of BH4-deficient mice with the DHFR inhibitor methotrexate induces reduction of BH4:BH2 ratios und eNOS uncoupling in lung tissue [13].

As demonstrated with human aortic endothelial cells, bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) and the murine endothelial cell line sEnd.1, the capacity of DHFR in reducing BH2 to BH4 is apparently rather low, as the cells respond to extracellular BH2 with a substantial increase in intracellular BH2, diminished NO and enhanced superoxide formation even if DHFR is not inhibited or knocked out [5,12,14]. These findings showing that supplementation of cells with BH2 induces eNOS uncoupling were in striking contrast to our preliminary observation that BH2 restores eNOS function in BH4-depleted porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAECs).

The present study was aimed at clarifying whether cell type-specific differences in BH2-to-BH4 reduction may account for the differential effects of BH2 supplementation on eNOS function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

l-[2,3-3H]Arginine hydrochloride (1.5–2.2 TBq/mmol) was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and purified as described earlier [15]. DEA/NO was obtained from Alexis Corporation (Lausen, Switzerland) and dissolved and diluted in 10 mM NaOH. Dihydroethidium was from Calbiochem – Merck4Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany) and dissolved in DMSO. BH4, BH2 and amino-BH4 were from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Antibiotics and fetal calf serum were purchased from PAA Laboratories (Linz, Austria). Culture media and other chemicals were from Sigma–Aldrich (Vienna, Austria).

2.2. Culture and treatment of endothelial cells

Porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAECs) were isolated as described [16] and cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2, in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated as described [17] and cultured in Medium 199, supplemented with 15% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B, 2 mM l-glutamine, 5000 U/ml heparin, and 10 μg/ml endothelial cell growth factor. The human microvascular endothelial cell line, HMEC-1 [18] was kindly provided by F.J. Candal (Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA, USA) and was maintained in medium MCDB131 supplemented with 15% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 1 mg/ml hydrocortisone. Where indicated, cells were pretreated in culture medium containing DAHP, aminopterin and/or pteridines.

2.3. Determination of endothelial l-[3H]citrulline formation

Intracellular conversion of l-[3H]arginine into l-[3H]citrulline was measured as previously described [19]. Briefly, cells grown in 6-well plates were washed and equilibrated for 15 min at 37 °C in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (incubation buffer). Reactions were started by addition of l-[2,3-3H]arginine (∼106 dpm) and A23187 (1 μM) and terminated after 10 min by washing the cells with chilled incubation buffer. Subsequent to lysis of the cells with 0.01 N HCl, an aliquot was removed for the determination of incorporated radioactivity. To the remaining sample, 200 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 13.0) containing 10 mM l-citrulline was added (final pH ∼5.0), and l-[3H]citrulline separated from l-[3H]arginine by cation exchange chromatography [19].

2.4. Determination of endothelial cGMP formation

Accumulation of intracellular cGMP was determined as previously described [19]. Briefly, cells grown in 24-well plates were washed and preincubated for 15 min at 37 °C in incubation buffer (see above), additionally containing 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine and 1 μM indomethacin. Reactions were started by addition of A23187 (1 μM) and terminated after 4 min by removal of the incubation medium and addition of 0.01 N HCl. Within 1 h, intracellular cGMP was completely released into the supernatant and measured by radioimmunoassay.

2.5. Determination of endothelial reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation

Cells grown on glass coverslips were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in incubation buffer containing 10 μM dihydroethidium, washed and incubated for further 30 min with buffer containing 1 μM A23187. Alternatively, cells were incubated for 4 h in phenol red free culture medium containing 10 μM dihydroethidium and, where indicated, stimulated with 1 μM A23187 1 h prior to the end of incubation. The latter method allowed a more reliable measurement of basal ROS formation and was used for the experiments shown in Fig. 5. Subsequent to incubation, cells were washed with incubation buffer and fluorescence imaging was performed at room temperature using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 setup, equipped with a xenon lamp, polychromator, Chroma filters (exciter: HQ546/12; emitter: HQ605/75; beamsplitter: Q560lp) and a CoolSNAP fx-HQ CCD-camera (Visitron Systems GmbH, Puchheim, Germany). The microscopic fields were selected randomly and the exposure time was 5 s for each image. Routinely, 3 images were taken and at least 50 cells/coverslip were analyzed using the Meta Imaging Series 5.0 software from Universal Imaging Corporation (Downingtown, PA, USA) or the open source image analysis program, ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Values were corrected for background fluorescence measured in cell-free areas.

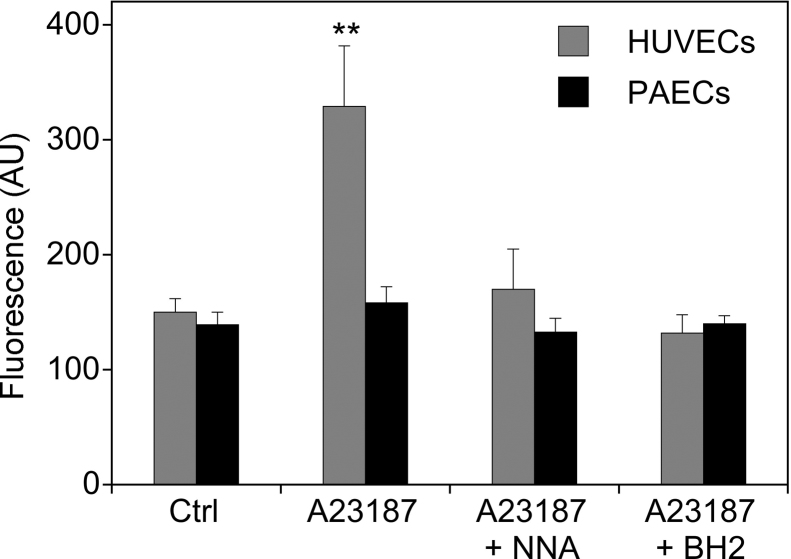

Fig. 5.

Basal and A23187-induced ROS formation in PAECs und HUVECs. Cells grown on glass coverslips were incubated for 4 h in phenol red free culture medium containing 10 μM dihydroethidium. Where indicated, cells were stimulated with A23187 (1 μM) and in the absence or the presence of l-NNA (0.3 mM) during the last hour of incubation. For loading the cells with BH4, BH2 (final concentration 0.1 mM) was added to the culture medium 1 h prior to the addition A23187. ROS formation was quantitated by fluorescence imaging as described in Section 2. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 3–5 independent experiments (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with untreated control).

2.6. Determination of BH4, BH2 and biopterin levels

Intracellular levels of pteridines were quantified by HPLC analysis using a method adapted from Fukushima and Nixon [20] as described previously [21]. Briefly, cells grown in petri dishes (diameter 90 mm) were harvested (∼5 × 106 per petri dish), washed, and resuspended in either 0.1 ml of PBS containing 1 mM DTT (for quantifying biopterin), 0.1 ml of alkaline oxidant solution (0.02 M KI/I2 in 0.1 M NaOH; for quantifying biopterin plus BH2), or 0.1 ml of acidic oxidant solution (0.02 M KI/I2 in 0.1 M HCl; for quantifying biopterin plus BH2 plus BH4). Subsequent to lysis of the cells by sonication, 20-μl aliquots were removed for protein determination, and the remaining samples were incubated for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Then, samples oxidized under alkaline or acidic conditions were mixed with 10 μl of 1 M HCl or water, respectively, and centrifuged. The resulting supernatants were mixed with 10 μl of 0.2 M ascorbic acid and neutralized by addition of 1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8.0. Non-oxidized samples were mixed with 30 μl of water and centrifuged. For HPLC analysis, samples were loaded on a LiChrospher 100 RP 18 HPLC column, 5 μm particle size (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and eluted with 20 mM NaH2PO4, pH 3, containing 5% methanol at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Biopterin was quantified with a fluorescence detector at excitation and emission wavelengths of 350 and 440 nm, respectively, by interpolation in calibration curves that were established daily with authentic BH2 (3–300 nM) oxidized under acidic conditions. BH4 and BH2 levels were calculated based on the amount of biopterin measured after oxidation in acid (biopterin + BH2 + BH4), after oxidation in base (biopterin + BH2), or in non-oxidized samples (biopterin). In accordance with literature data [20], 90.6 ± 6.5% of BH2 and 100.7 ± 3.5% of BH4 were recovered as biopterin after oxidation in acid (mean values ± SD, n = 10). In base, the recovery of BH2 was 86.7 ± 7.4%, whereas only 1.2 ± 0.2% of BH4 was oxidized to biopterin under this condition.

2.7. Determination of DHFR activity in cell cytosols and PD10 eluates

Cells grown in petri dishes were harvested, washed with 10 mM triethanolamine/HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 10 mM DTT and 0.5 mM EDTA and lysed by three cycles of freeze/thawing. Cytosolic fractions were obtained by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h and, where indicated, passed over a Sephadex G 25 column (PD10, GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Vienna, Austria). DHFR activity was measured by a method adapted from published procedures [22,23]. Briefly, cytosolic fractions or PD10 eluates containing 5–20 μg of protein were incubated at 37 °C in a total volume of 0.1 ml of 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM DTT, 20 mM ascorbate, 1 mM EDTA, 50 μM NADPH and either DHF or BH2 at concentrations indicated. After 10 min, reactions were terminated by addition of 10 μl trichloroacetic acid (2 N) and precipitates removed by centrifugation (5 min at 10,000 × g). When DHF was used as substrate, samples were mixed with 10 μl of stabilization solution (containing 1 M ascorbate and 100 mM DTT), loaded on a LiChrospher 100 RP 18 HPLC column, 5 μm particle size (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and eluted with 5 mM KH2PO4, pH 2.3, containing 7% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. THF was quantified with a fluorescence detector at excitation and emission wavelengths of 295 and 365 nm, respectively, by interpolation in calibration curves that were established daily with authentic THF (0.1–5 μM).

When BH2 was used as substrate, samples were mixed with 100 μl of alkaline oxidant solution (0.04 M KI/I2 in 0.4 M NaOH) and incubated for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Then, samples were mixed with 26 μl of 1 M HCl and centrifuged. The resulting supernatants were mixed with 26 μl of 0.2 M ascorbic acid and neutralized by addition of 1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8.0. For HPLC analysis, samples were loaded on a Nucleosil 100-10 SA HPLC column (Macheray-Nagel, Germany) and eluted with 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 3 at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. BH4 was quantified as pterin with a fluorescence detector at excitation and emission wavelengths of 350 and 440 nm, respectively, by interpolation in calibration curves that were established daily with authentic BH4 (0.2–2 μM) oxidized under the same conditions. DHFR acitivty data were corrected for non-enzymatic BH2/DHF reduction measured in heat-inactivated cell cytosols. Enzyme kinetic parameters were calculated by nonlinear regression to the Michaelis–Menten equation by using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software). Specifically, Km and Vmax were derived from fits to the equation f = a · [S]/(b + [S]), with fitting parameters a = Vmax and b = Km, whereas Vmax/Km was obtained by fitting the same result to the equation f = a · [S]/(1 + [S]/b), with fitting parameters a = Vmax/Km and b = Km.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical differences within groups were evaluated by one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Fisher's LSD test. Analyses were performed with KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software).

3. Results

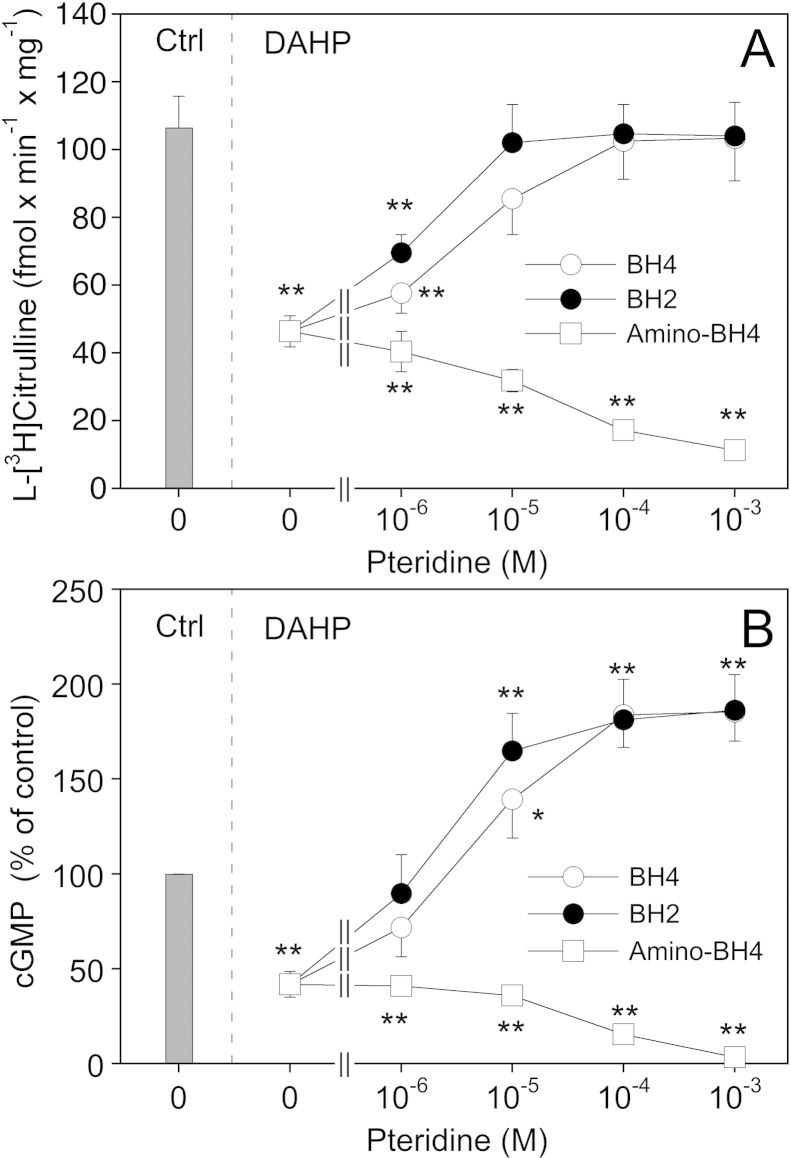

3.1. Effect of pteridine supplementation on eNOS activity in BH4-depleted PAECs

The activity of eNOS in PAECs was monitored by measuring the conversion of 3H-arginine to 3H-citrulline (Fig. 1A) and accumulation of cGMP (Fig. 1B) in the presence of a maximally active concentration of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (1 μM). As shown in panel A, inhibition of de novo biosynthesis of BH4 by preincubating the cells for 24 h with the GTP cyclohydrolase inhibitor DAHP (10 mM) diminished l-[3H]citrulline formation from 106 ± 9 to 46 ± 5 fmol min−1 mg−1. When BH4 (final concentration 1 μM–1 mM) was added to the culture medium 1 h prior to the end of the DAHP treatment, l-[3H]citrulline formation was increased in a concentration-dependent manner and completely restored with 0.1 mM of BH4 (102 ± 11 fmol min−1 mg−1). An even more pronounced effect was observed with BH2, which fully restored l-[3H]citrulline formation at 10 μM. For comparison, we also performed experiments with the 4-amino analog of BH4, a pterin antagonist of NOS [19,24,25]. As expected, a 1-h incubation of DAHP-treated cells with the 4-amino derivative (final concentration 1 μM–1 mM) further reduced l-[3H]citrulline formation down to basal levels (11 ± 2 fmol min−1 mg−1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on eNOS activity in BH4-depleted PAECs. PAECs were pretreated for 24 h with culture medium in the absence (Ctrl) or the presence of 10 mM DAHP. Where indicated, pteridines were added to the medium 1 h prior to the end of the DAHP treatment. Then, cells were washed and l-arginine to l-citrulline conversion (A) or cGMP formation (B) determined as described in Section 2. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 3–5 independent experiments (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with untreated control).

In addition to its effect on arginine-to-citrulline conversion, pretreatment of the cells with DAHP reduced A23187-induced cGMP accumulation to 41.9 ± 6.8% (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, addition of BH4 or BH2 not only antagonized the inhibitory effect of DAHP but also increased cGMP accumulation up to 185 ± 15.4 and 186 ± 18.8%, respectively. In view of these intriguing results we also measured cGMP accumulation in response to a maximally active concentration of DEA/NO (1 μM) and observed that the effect of the NO donor was also increased ∼2-fold upon preincubation of the cells with DAHP (data not shown). These findings suggest that DAHP (presumably via inhibiting endothelial NO production) induces a sensitization of the cGMP response, a phenomenon that might be related to the NO supersensitivity of blood vessels treated with NO synthase inhibitors [26].

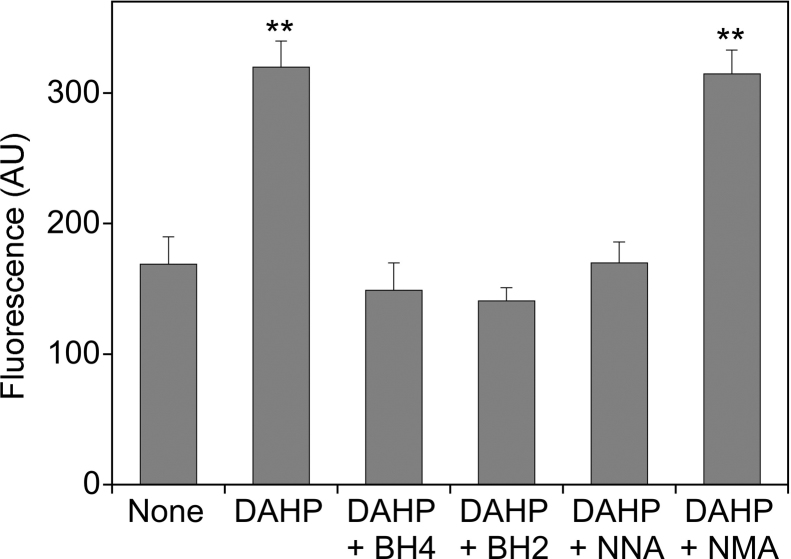

3.2. Effect of pteridine supplementation on ROS formation in BH4-depleted PAECs

To test whether the inhibition of l-citrulline/cGMP formation by DAHP was indeed due to eNOS uncoupling, we measured A23187-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation by single cell microscopy using dihydroethidium as fluorescence dye. As shown in Fig. 2, preincubation of PAECs with DAHP increased the fluorescence signal from 169 ± 21 to 320 ± 20 AU, and the effect was prevented by BH4 (149 ± 21 AU) and by BH2 (141 ± 10 AU). Reduction of DAHP-induced fluorescence by l-NNA (170 ± 16 AU) but not by l-NMA (315 ± 148 AU), which has no effect on uncoupled NADPH oxidation by purified eNOS [27], strongly suggests that the signal reflects eNOS-catalyzed superoxide formation.

Fig. 2.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on ROS formation in BH4-depleted PAECs. PAECs grown on glass coverslips were pretreated for 24 h with culture medium in the absence (Ctrl) or the presence of 10 mM DAHP. Where indicated, BH4 or BH2 (final concentration 0.1 mM) was added to the medium 1 h prior to the end of the DAHP treatment. Then, cells were incubated with dihydroethidium (10 μM, 10 min) and stimulated for 30 min with A23187 (1 μM) in the absence and the presence of l-NNA or l-NMA (0.3 mM, each). ROS formation was quantitated by fluorescence imaging as described in Section 2. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 3–5 independent experiments (**p < 0.01 compared with untreated control).

3.3. Effect of pteridine supplementation on intracellular BH2/BH4 levels in PAECs

The observation that both BH4 and BH2 restored eNOS function suggests that BH2 is reduced efficiently to BH4 by PAECs, and this was confirmed by determination of cellular BH4/BH2 levels. As shown in Table 1, preincubation of the cells with DAHP markedly reduced the intracellular levels of both reduced biopterins. When cells were subsequently incubated with 10 μM BH2, intracellular BH2 remained unchanged (0.2 ± 0.1 pmol/mg), whereas BH4 was almost completely restored (from 0.1 ± 0.1 to 4.3 ± 1.4 pmol/mg as compared to 6.7 ± 0.8 pmol/mg in untreated cells). Similarly, incubation with 0.1 mM BH2 primarily evoked an increase in intracellular BH4 (28.6 ± 6.1 pmol/mg protein), whereas BH2 was barely affected (1.4 ± 0.4 pmol/mg protein). Incubation of DAHP-treated cells with BH4 also led to increased intracellular BH4, but the effect was significantly less pronounced than that induced by BH2 (e.g. 8.7 ± 1.9 and 28.6 ± 6.1 pmol BH4/mg with 0.1 mM BH4 and 0.1 mM BH2, respectively). Similar results were obtained with cells that had not been pre-treated with DAHP. Incubation with BH2 markedly elevated intracellular BH4 without affecting BH2 levels, and application of BH2 was more effective in increasing intracellular BH4 than application of BH4 itself, presumably due to faster cellular uptake of BH2 [28]. To test for a role of DHFR in BH2 reduction, cells were supplemented with BH2 in the presence of the DHFR inhibitor aminopterin. As shown in Table 1, aminopterin caused a pronounced shift from BH4 to BH2, indicating that DHFR is essential for BH4 recycling in PAECs.

Table 1.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on intracellular BH2/BH4 levels in PAECs.

| Treatment | BH4 (pmol/mg protein) | BH2 (pmol/mg protein) | BH4/BH2 (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 8.4 |

| DAHP (10 mM) | 0.1 ± 0.1** | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 21.5 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 28.6 ± 6.1** | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 20.4 |

| +10 μM BH4 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 3.3 |

| +0.1 mM BH4 | 8.7 ± 1.9 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 29.0 |

| BH2 (10 μM) | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 19.8 |

| BH2 (0.1 mM) | 49.0 ± 7.7** | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 18.1 |

| BH4 (10 μM) | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 17.8 |

| BH4 (0.1 mM) | 12.1 ± 4.0 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 17.3 |

| Aminopterin (0.1 mM) | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 1.5 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 2.8 | 1.0 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 30.8 ± 8.4** | 0.4 |

For pteridine supplementation, PAECs were incubated with either BH2 or BH4 for 1 h in culture medium, and intracellular BH2/BH4 levels were measured as described in Section 2. Where indicated, experiments were performed with cells that had been pretreated with DAHP (24 h) or aminopterin (30 min). Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 4–6 independent experiments.

p < 0.01 compared with untreated control.

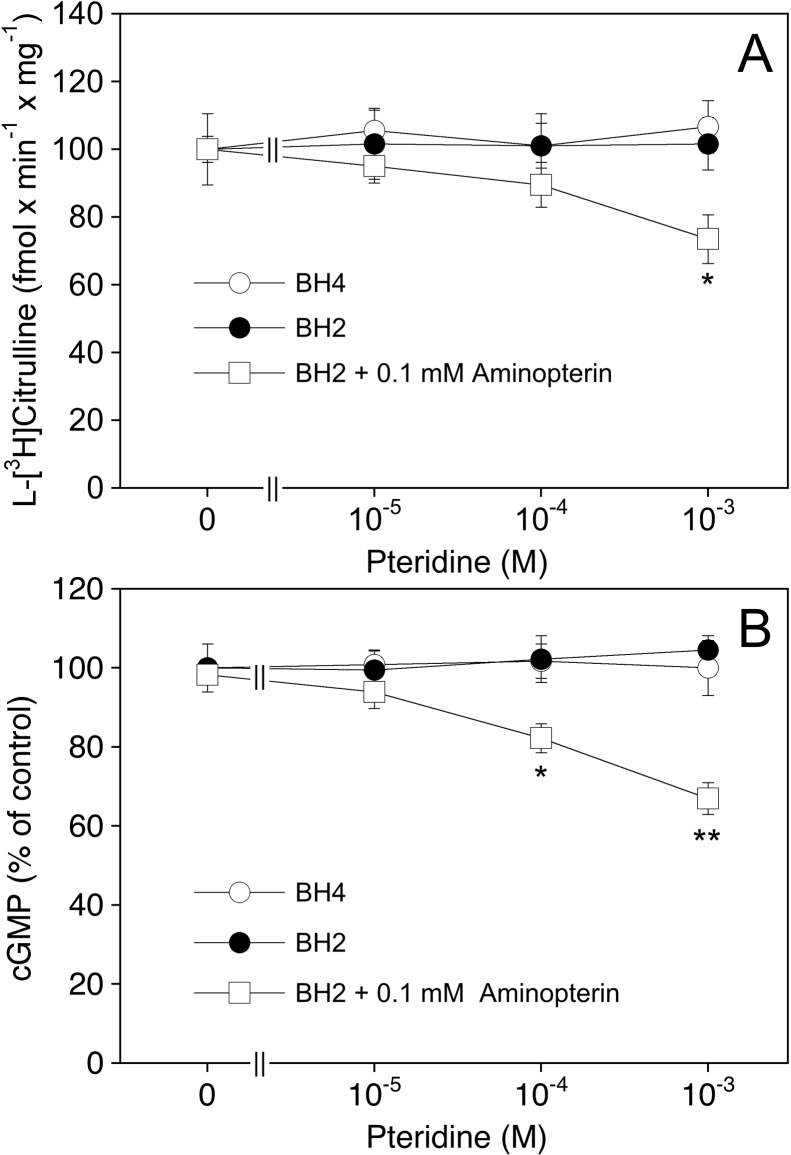

3.4. Effect of pteridine supplementation on eNOS activity in untreated PAECs

To find out how eNOS activity is modulated by the various intracellular BH4 and BH2 levels, we studied the effects of BH4, BH2 and aminopterin on citrulline and cGMP formation in PAECs under control conditions, i.e. in cells that had not been pre-treated with DAHP. As shown in Fig. 3, neither l-[3H]citrulline formation (panel A) nor cGMP accumulation (panel B) were significantly affected by exogenously added BH4 or BH2, suggesting that the basal level of 6.7 ± 0.8 pmol BH4/mg protein (see Table 1) is sufficient for eNOS saturation. Aminopterin (0.1 mM), which increased BH2 levels from 0.8 ± 0.3 to 3.5 ± 1.1 pmol/mg and reduced the BH4/BH2 ratio from 8.4 to 1.5, had no effect alone but slightly reduced l-l-[3H]citrulline formation and cGMP accumulation in the presence of BH2 (to 70–80% of controls at 0.1 mM). These results indicate that inhibition of DHFR results in intracellular accumulation of BH2, which competes with endogenous BH4 for eNOS binding.

Fig. 3.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on eNOS activity in PAECs.

PAECs were pretreated for 1 h with culture medium in the absence or the presence of BH4 or BH2. Where indicated, aminopterin (final concentration 0.1 mM) was added to the medium 30 min prior to addition of BH2. Then, cells were washed and l-arginine to l-citrulline conversion (A) or cGMP formation (B) determined as described in Section 2. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 3–5 independent experiments (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with untreated control).

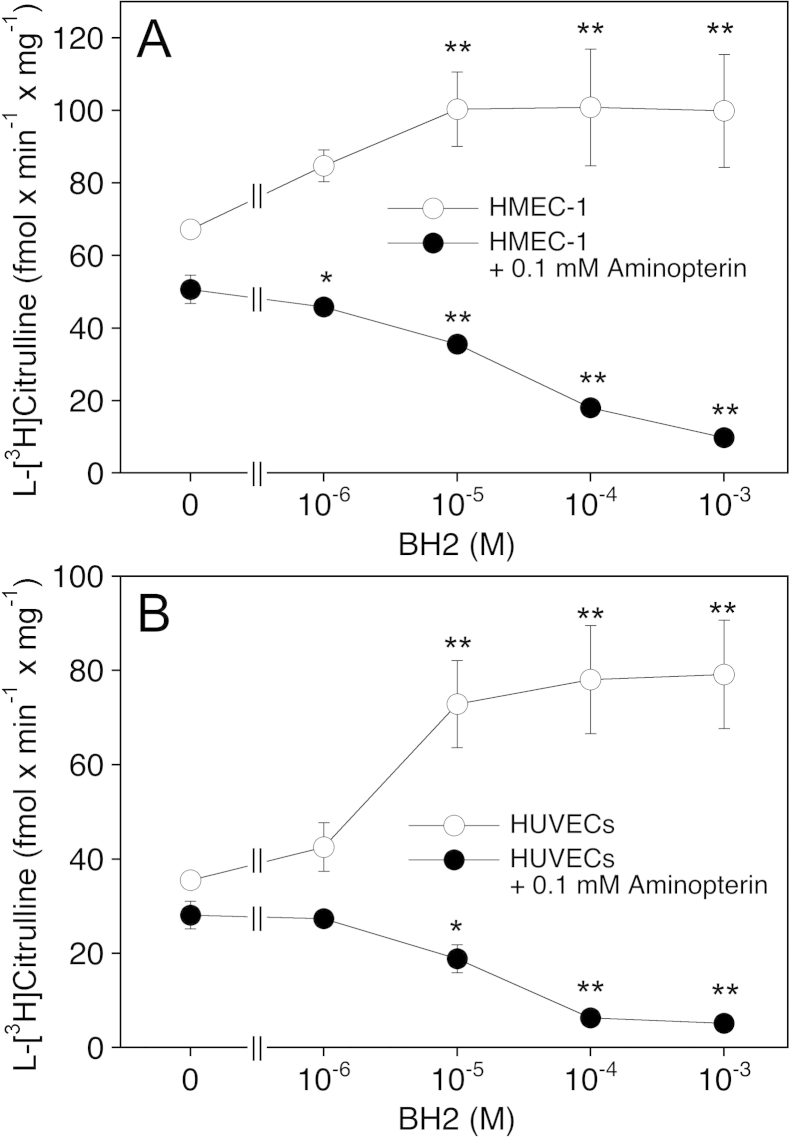

3.5. Comparison with other endothelial cells

In contrast to our observations with PAECs, endothelial cells from other sources (bovine and human aorta as well as the murine sEnd.1 cell line) have been reported to respond to BH2 supplementation with a pronounced increase in intracellular BH2 levels [5,12,14], suggesting that the efficiency of BH4 recycling varies among different types of endothelial cells. To address this issue we performed experiments with the human microvascular endothelial cell line HMEC-1 and cells isolated from human umbilical veins (HUVECs). As shown in Table 2, HMEC-1 cells exhibited rather low levels of BH4 (0.7 pmol/mg) and a BH4/BH2 ratio as low as 1.4. Incubation of the cells with BH2 evoked primarily an increase in intracellular BH4, and upon treatment with 10 μM BH2, both BH4 levels and the BH4/BH2 ratio was comparable to that of untreated PAECs (see Table 1). As expected from the low intracellular biopterin levels, eNOS was significantly less active in HMEC-1 cells than in PAECs, but the formation of l-[3H]citrulline was increased by BH2 supplementation (from 67 ± 5 to a maximum of 101 ± 10 fmol min−1 mg−1 with 10 μM BH2) (Fig. 4A). Incubation with 0.1 mM aminopterin in the absence of BH2 slightly decreased l-[3H]citrulline formation to 51 ± 4 fmol min−1 mg−1. The effect of the DHFR inhibitor was enhanced by co-incubation with BH2, resulting in virtually complete eNOS inhibition at 1 mM BH2. Table 2 shows that the effect of BH2 correlated with a decrease in the BH4/BH2 ratio from 0.36 to 0.03.

Table 2.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on intracellular BH2/BH4 levels in HMEC-1 cells and HUVECs.

| BH4 (pmol/mg protein) | BH2 (pmol/mg protein) | BH4/BH2 (ratio) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMEC-1 cells | |||

| None | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 |

| +1 μM BH2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 8.4 ± 0.6** | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 7.6 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 101.8 ± 6.9** | 15.3 ± 6.1** | 6.7 |

| Aminopterin (0.1 mM) | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.36 |

| +1 μM BH2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.25 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 9.4 ± 0.7** | 0.12 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 90.1 ± 1.6** | 0.03 |

| HUVECs | |||

| None | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.75 |

| +1 μM BH2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 1.00 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 5.4 + 0.7* | 2.9 ± 0.5* | 1.86 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 56.7 ± 4.8** | 29.9 ± 4.5** | 1.90 |

| Aminopterin (0.1 mM) | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.33 |

| +1 μM BH2 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 0.14 |

| +10 μM BH2 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 13.9 ± 0.6 | 0.12 |

| +0.1 mM BH2 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 71.5 ± 0.5 | 0.04 |

For pteridine supplementation, cells were incubated with either BH2 or BH4 for 1 h in culture medium, and intracellular BH2/BH4 levels were measured as described in Section 2. Where indicated, experiments were performed with cells that had been pretreated for 30 min with aminopterin. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 4–6 independent experiments.

p < 0.05 compared with untreated control.

p < 0.01 compared with untreated control.

Fig. 4.

Effect of pteridine supplementation on eNOS activity in HMEC-1 cells and HUVECs. HMEC-1 cells or HUVECs were pretreated for 1 h with culture medium in the absence or the presence of BH2. Where indicated, aminopterin (final concentration 0.1 mM) was added to the medium 30 min prior to addition of BH2. Then, cells were washed, and l-arginine to l-citrulline conversion was determined as described in Section 2. Data are mean values ± S.E.M. of 3–5 independent experiments (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with untreated control).

In untreated HUVECs, basal levels of BH4 (0.3 ± 0.2 pmol/mg, Table 2) and l-[3H]citrulline formation (36 ± 2 fmol min−1 mg−1, Fig. 4B) were even lower than in HMEC-1 cells. Moreover, HUVECs responded to supplementation with BH2 not only with an increase in BH4 levels but also in a substantial elevation of intracellular BH2, leading to BH4/BH2 ratios of 1–2. Nonetheless, incubation with BH2 was accompanied by an increase in l-[3H]citrulline formation up to 79 ± 11 fmol min−1 mg−1. In the presence of aminopterin, supplementation of HUVECs with BH2 evoked primarily an increase in intracellular BH2 and a decrease in l-[3H]citrulline formation down to basal values.

Our data showing that untreated HUVECs exhibit rather low BH4 levels and respond to elevation in intracellular BH4 with an increase in l-[3H]citrulline formation suggest that eNOS is partially uncoupled under basal conditions. Indeed, incubation of untreated HUVECs with A23187 triggered an l-NNA-sensitive increase in dihydroethidium fluorescence that was abolished upon loading the cells with BH4 (Fig. 5). PAECs, which have ∼20-fold higher basal BH4 levels than HUVECs, did not show any eNOS-catalyzed superoxide formation under these conditions.

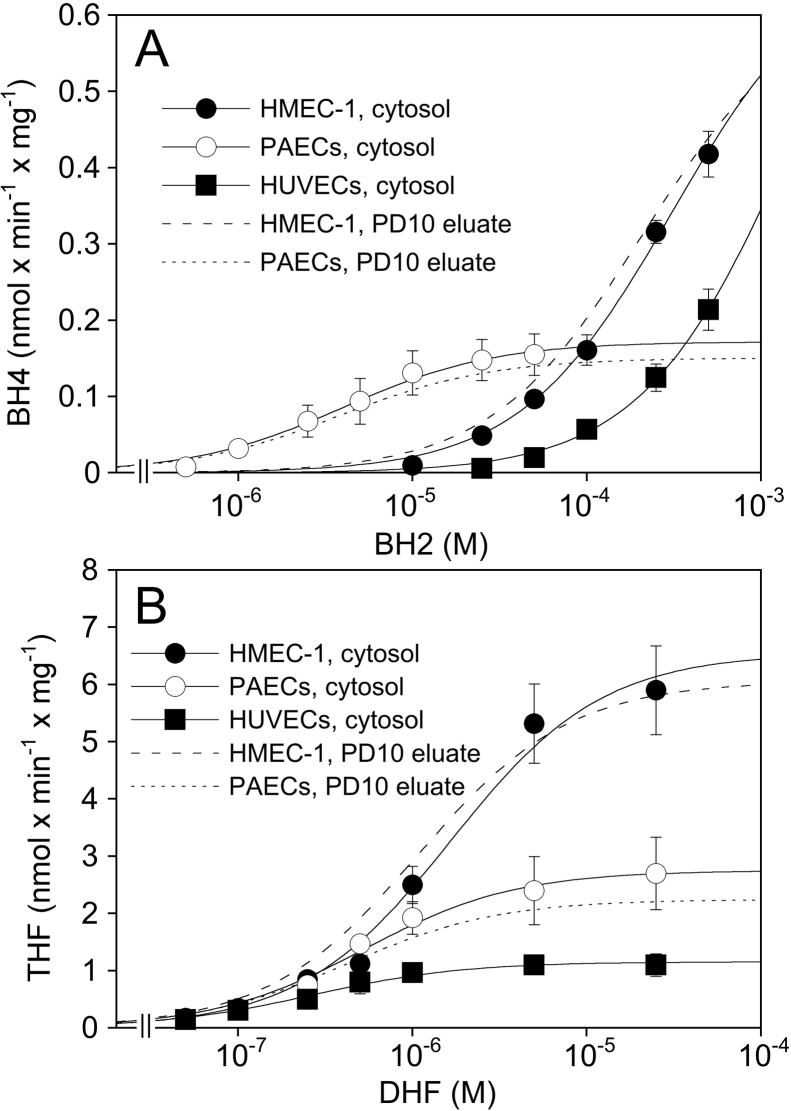

3.6. DHFR activity in porcine and human endothelial cells

These results show that PAECs recycle BH2 more efficiently than HUVECs or HMEC-1 cells. To account for the established role of DHFR in BH4 recycling, we studied kinetics of the enzyme in endothelial cell cytosols with BH2 and DHF as substrates. As evident from the data shown in Fig. 6A and Table 3, reduction of BH2 to BH4 occurred in cytosols of PAECs with a Km of 5.2 ± 1.3 μM and a Vmax of 0.17 ± 0.03 nmol min−1 mg−1. Intriguingly, the Vmax value was about 3- to 5-fold higher in cytosols of HUVECs and HMEC-1 cells, but the human cells exhibited extremely high Km values in the range of 0.25–1.5 mM. Virtually identical results were obtained with cytosols passed over a PD10 column, excluding competition for BH4 binding by low molecular mass components present in the cytosolic fractions of the human cells. Also included in Table 3 are values for the apparent specificity constant (Vmax/Km), amounting to (4.3 ± 0.5) × 104, (2.22 ± 0.13) × 103, and (5.7 ± 0.6) × 102 nmol BH4 min−1 mg−1 M−1, for PAECs, HMEC-1 cells, and HUVECs, respectively. In contrast to the results obtained with BH2, the Km values for DHF were of the same order of magnitude (0.3–1.9 μM) in all three cell preparations (Fig. 6B, Table 3). Aminopterin (0.1 mM) and methotrexate (0.1 mM) completely inhibited enzyme activity measured with either DHF or BH2 as substrate (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

DHFR activity in broken cell preparations. DHFR activity was measured in cell cytosols or PD10 eluates as described in Section 2 using either BH2 (A) od DHF (B) as substrate. The data points shown are from experiments with cytosols and are mean values ± S.E.M. of 4–6 cell preparations. The curves shown were obtained by fitting the mean values to the Michealis–Menten equation. For clarity, results obtained with PD10 eluates (n = 3) are only shown as curve fits without data points.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for DHFR.

| BH2 |

DHF |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol BH4 min−1 mg−1) | Vmax/Km (nmol BH4 min−1 mg−1 M−1) | Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol THF min−1 mg−1) | |

| PAECs | |||||

| Cytosol | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 4.3 ± 0.5 × 104 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

| PD10 eluate | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 3.9 ± 0.7 × 104 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| HMEC-1 cells | |||||

| Cytosol | ∼250 | ∼0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 × 103 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.8 |

| PD10 eluate | ∼250 | ∼0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.4 × 103 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.2 |

| HUVECs | |||||

| Cytosol | ∼1500 | ∼0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.6 × 102 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

Km, Vmax, and Vmax/Km values were derived from individual curve fits to the saturation data as described in Section 2 and are mean values ± S.E.M. from 3 to 6 experiments each performed with a different batch of cytosol or eluate. Due to the incomplete saturation curves (see Fig. 6A), only estimates are given for the Km and Vmax values obtained with BH2 and HMEC-1 cells/HUVECs.

4. Discussion

Our study revealed pronounced differences in BH4 metabolism in endothelial cells derived from different sources. This particularly applies to the DHFR-catalyzed regeneration of BH4 from BH2, a reaction that is considered crucial for cellular BH4 homeostasis [10–12]. As shown in the present study, PAECs exhibit rather high levels of BH4 (∼7 pmol/mg protein) and a BH4/BH2 ratio of 8.4, which is reduced to 1.5 upon inhibition of DHFR with aminopterin. In HUVECs and HMEC-1 cells, basal BH4 levels are less than 1 pmol/mg protein and BH4/BH2 ratios are much lower (1.0 and 0.3 in the absence and the presence of aminopterin, respectively). While these results confirm that DHFR is essential for BH4 recycling in cultured cells, the striking differences in the efficiency of BH2 reduction in different cell types was unexpected. The highly efficient BH4 recycling by PAECs as compared to HMEC-1 cells and HUVECs is unequivocally demonstrated by our observation that incubation of PAECs with BH2 led to an almost exclusive increase in intracellular BH4, whereas the human cells, in particular HUVECs, responded to BH2 supplementation with a rise in both BH4 and BH2. Nonetheless, incubation with BH2 never elicited a decrease in the BH4/BH2 ratios, as reported for BAECs [12] and sEnd.1 cells [5]. While supplementation of PAECs, HMEC-1 cells and HUVECs with 10 μM BH2 resulted in BH4/BH2 ratios of 19.8, 7.6, and 1.9, respectively (present study), ratios of 1, 0.6 and 0.1 have been reported for BH2-treated murine sEnd.1 cells [5], BAECs [12] and human aortic endothelial cells [14], respectively. Although BH4/BH2 ratios may not directly reflect DHFR activity, they appear to be a reliable measure for the efficiency of DHFR-catalyzed BH4 recycling in endothelial cells, the efficiency of which might be ranked as follows: PAECs > HMEC-1 > HUVECs > sEnd.1 > BAECs > human aortic endothelial cells.

The efficient BH4 recycling by PAECs is most likely a consequence of the high BH2 affinity of DHFR in these cells (apparent Km ∼ 3 μM). Assuming a cell volume of 1 pl and a protein content of 100 pg/cell, the data shown in Tables 1 and 2 indicate that the intracellular BH2 concentration of endothelial cells is in the submicromolar range, suggesting that DHFR is operating well below its Km-values, which implies that the apparent specificity constant (Vmax/Km) is the relevant parameter. Accordingly, one can estimate hat PAECs are 19× and 75× more effective than HMEC-1 cells and HUVECs, respectively, in recovering BH4 from BH2 by DHFR.

What are the consequences of the differences in DHFR kinetics on endothelial NO formation? PAECs respond to incubation with BH2 with a marked increase in the BH4/BH2 ratio. Accordingly, eNOS function in BH4-depleted cells can be restored by supplying BH4 or BH2. In accordance with literature data showing that the cellular uptake of BH2 is faster than that of BH4 [28], treatment with BH2 is even more efficient in restoring eNOS activity than BH4. When comparing l-citrulline/cGMP data with cellular BH4 levels, it can be seen that in DAHP-treated cells maximal eNOS activity is regained with 10 μM BH2 (corresponding to 4.3 pmol BH4/mg) but not with 10 μM BH4 (corresponding to 1.3 pmol BH4/mg), suggesting that BH4 levels of 2–4 pmol/mg are required for eNOS coupling. Under basal conditions, BH4 levels are 6.7 pmol/mg and eNOS is saturated with BH4. Accordingly, a further increase in BH4 as induced by treatment of the cells with BH4 or BH2 (this study) or the BH4 precursor sepiapterin [29] has no impact on l-citrulline/cGMP formation. Also, inhibition of DHFR with aminopterin has no effect, since the resulting BH4/BH2 ratio and BH4 level and of 5 and 1.5 pmol/mg, respectively, are still sufficiently high for proper eNOS function. However, when these cells are additionally incubated with BH2, the BH4/BH2 ratio falls below 1, and eNOS uncoupling occurs.

In contrast to PAECs, HUVECs and HMEC-1 cells exhibit basal BH4 levels of only 0.3 and 0.7 pmol/mg, respectively. As a consequence, eNOS is partially uncoupled and l-citrulline formation rather low. The cells respond to incubation with BH2 with an increase in BH4 levels and BH4/BH2 ratios, but the effect is less pronounced than in PAECs. Nonetheless, upon incubation with 10 μM BH2, cellular BH4 levels in HUVECs and HMEC-1 cells are 5.4 and 8.4 pmol/mg, respectively, and thus sufficiently high to promote full eNOS coupling and maximal l-citrulline formation. These data are in accordance with previous reports showing that elevation of BH4 levels in HUVECs by sepiapterin is accompanied by increased eNOS activity measured as formation of l-citrulline and/or cGMP [30–32].

Despite different efficiencies in BH4 regeneration, PAECs, HUVECs and HMEC-1 cells exhibit sufficient DHFR activity to respond to supplementation with BH2 with an increase in the BH4/BH2 ratio and thus no deleterious effect on eNOS occurs. This is not the case in bovine and murine endothelial cells. Treatment of BAECs with BH2 (10 μM, 1 h) has been reported to reduce the BH4/BH2 ratio from 3.8 to 0.6 and to promote a decrease in VEGF-induced nitrite formation and an increase in H2O2 production [12]. Similarly, a decline in the BH4/BH2 ratio that was accompanied by an increase in l-NAME-sensitive superoxide production was observed upon supplementation of sEnd.1 cells with BH2 [5]. Since in both types of cells inhibition of DHFR activity by methotrexate and/or genetic knockdown of the DHFR protein by RNA interference has been shown to reduce basal BH4/BH2 ratios and to increase eNOS-catalyzed ROS formation, DHFR activity in BAECs and sEnd.1 cells is sufficient to prevent eNOS uncoupling under basal conditions but not when cells are challenged with BH2 [11,12].

We cannot explain the striking differences in the apparent BH2 affinities of DHFR in different types of endothelial cells. Since human cells from different sources show pronounced variation in recycling efficiency (see above), our observations are probably not explained by species differences. The virtually identical results obtained with desalted cytosols exclude a substrate-competitive effect of endogenous low molecular mass components of the cells, but we cannot exclude that an unknown protein present in some types of cells interferes with BH2 (but not DHF) binding. Interestingly, the subcellular distribution of DHFR is regulated by various cellular processes, in particular cell cycle, resulting in partial cytosolic, mitochondrial and nuclear localization of the protein under certain conditions [33]. The detailed intracellular distribution of DHFR in the various endothelial cell types is not known, but it is conceivable that the cellular environment has subtle effects on protein conformation and substrate binding. For example, targeting of the enzyme to nuclei requires post-translational modification with the small ubiquitin-like modifier, SUMO [34,35], a reaction that could affect BH2 binding. In any case, further work is necessary to settle this issue.

In conclusion, there are pronounced, cell-type specific differences in endothelial BH4 regeneration. As a consequence, basal BH4/BH2 ratios and thus eNOS function vary from cell type to cell type, and cells respond to extracellular BH2 with either an increase intracellular BH2 or BH4. Thus, depending on the cell type, BH2 supplementation may induce or prevent eNOS uncoupling.

Acknowledgements

We thank Margit Rehn and Kerstin Geckl for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Austria: P22289 (to E.R.W.), P23135 (to A.C.F.G), P24005 and P24946 (to B.M.).

References

- 1.Gorren A.C.F., Mayer B. Nitric-oxide synthase: a cytochrome P450 family foster child. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:432–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt T.S., Alp N.J. Mechanisms for the role of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and vascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:47–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasquez-Vivar J. Tetrahydrobiopterin, superoxide, and vascular dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1108–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Förstermann U. Nitric oxide and oxidative stress in vascular disease. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:923–939. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabtree M.J., Smith C.L., Lam G., Goligorsky M.S., Gross S.S. Ratio of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin to 7,8-dihydrobiopterin in endothelial cells determines glucose-elicited changes in NO vs. superoxide production by eNOS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1530–H1540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00823.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klatt P., Schmid M., Leopold E., Schmidt K., Werner E.R., Mayer B. The pteridine binding site of brain nitric oxide synthase: tetrahydrobiopterin binding kinetics, specificity, and allosteric interaction with the substrate domain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13861–13866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Presta A., Siddhanta U., Wu C., Sennequier N., Huang L., Abu-Soud H.M. Comparative functioning of dihydro- and tetrahydropterins in supporting electron transfer, catalysis, and subunit dimerization in inducible nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:298–310. doi: 10.1021/bi971944c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner E.R., Blau N., Thöny B. Tetrahydrobiopterin: biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem J. 2011;438:397–414. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabtree M.J., Channon K.M. Synthesis and recycling of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and vascular disease. Nitric Oxide. 2011;25:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalupsky K., Cai H. Endothelial dihydrofolate reductase: critical for nitric oxide bioavailability and role in angiotensin II uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9056–9061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409594102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabtree M.J., Tatham A.L., Hale A.B., Alp N.J., Channon K.M. Critical role for tetrahydrobiopterin recycling by dihydrofolate reductase in regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase coupling: relative importance of the de novo biopterin synthesis versus salvage pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28128–28136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugiyama T., Levy B.D., Michel T. Tetrahydrobiopterin recycling, a key determinant of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase-dependent signaling pathways in cultured vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12691–12700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809295200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree M.J., Hale A.B., Channon K.M. Dihydrofolate reductase protects endothelial nitric oxide synthase from uncoupling in tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1639–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitsett J., Rangel Filho A., Sethumadhavan S., Celinska J., Widlansky M., Vasquez-Vivar J. Human endothelial dihydrofolate reductase low activity limits vascular tetrahydrobiopterin recycling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;63C:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klatt P., Pfeiffer S., List B.M., Lehner D., Glatter O., Bächinger H.P. Characterization of heme-deficient neuronal nitric-oxide synthase reveals a role for heme in subunit dimerization and binding of the amino acid substrate and tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7336–7342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt K., Mayer B., Kukovetz W.R. Effect of calcium on endothelium-derived relaxing factor formation and cGMP levels in endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;170:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meda C., Plank C., Mykhaylyk O., Schmidt K., Mayer B. Effects of statins on nitric oxide/cGMP signaling in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62:100–112. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ades E.W., Candal F.J., Swerlick R.A., George V.G., Summers S., Bosse D.C. HMEC-1: establishment of an immortalized human microvascular endothelial cell line. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:683–690. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12613748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt K., Werner-Felmayer G., Mayer B., Werner E.R. Preferential inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase in intact cells by the 4-amino analogue of tetrahydrobiopterin. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukushima T., Nixon J.C. Analysis of reduced forms of biopterin in biological tissues and fluids. Anal Biochem. 1980;102:176–188. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt K., Neubauer A., Kolesnik B., Stasch J.P., Werner E.R., Gorren A.C. Tetrahydrobiopterin protects soluble guanylate cyclase against oxidative inactivation. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:420–427. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.079855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhard J.F., Jr., Chao J.Y., Smith G.K., Duch D.S., Nichol C.A. A sensitive high-performance liquid chromatographic-fluorometric assay for dihydrofolate reductase in adult rat brain, using 7,8-dihydrobiopterin as substrate. Anal Biochem. 1984;140:548–552. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao L., Chalupsky K., Stefani E., Cai H. Mechanistic insights into folic acid-dependent vascular protection: dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR)-mediated reduction in oxidant stress in endothelial cells and angiotensin II-infused mice: a novel HPLC-based fluorescent assay for DHFR activity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner E.R., Pitters E., Schmidt K., Wachter H., Werner-Felmayer G., Mayer B. Indentification of the 4-amino analog of tetrahydrobiopterin as dihydropteridine reductase inhibitor and potent pteridine antagonist of rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Biochem J. 1996;320:193–196. doi: 10.1042/bj3200193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfeiffer S., Gorren A.C.F., Pitters E., Schmidt K., Werner E.R., Mayer B. Allosteric modulation of rat brain nitric oxide synthase by the pterin-site enzyme inhibitor 4-amino-tetrahydrobiopterin. Biochem J. 1997;328:349–352. doi: 10.1042/bj3280349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moncada S., Rees D.D., Schulz R., Palmer R.M. Development and mechanism of a specific supersensitivity to nitrovasodilators after inhibition of vascular nitric oxide synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2166–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.List B.M., Klösch B., Völker C., Gorren A.C.F., Sessa W.C., Werner E.R. Characterization of bovine endothelial nitric oxide synthase as a homodimer with down-regulated uncoupled NADPH oxidase activity: tetrahydrobiopterin binding kinetics and role of haem in dimerization. Biochem J. 1997;323:159–165. doi: 10.1042/bj3230159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa H., Sawabe K., Nakanishi N., Wakasugi O.K. Delivery of exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to cells of target organs: role of salvage pathway and uptake of its precursor in effective elevation of tissue BH4. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86(Suppl. 1):S2–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt K., Werner E.R., Mayer B., Wachter H., Kukovetz W.R. Tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent formation of endothelium-derived relaxing factor (nitric oxide) in aortic endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1992;281:297–300. doi: 10.1042/bj2810297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner-Felmayer G., Werner E.R., Fuchs D., Hausen A., Reibnegger G., Schmidt K. Pteridine biosynthesis in human endothelial cells – impact on nitric oxide-mediated formation of cyclic GMP. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1842–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heller R., Unbehaun A., Schellenberg B., Mayer B., Werner-Felmayer G., Werner E.R. l-Ascorbic acid potentiates endothelial nitric oxide synthesis via a chemical stabilization of tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker T.A., Milstien S., Katusic Z.S. Effect of vitamin C on the availability of tetrahydrobiopterin in human endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;37:333–338. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tibbetts A.S., Appling D.R. Compartmentalization of mammalian folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:57–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson D.D., Woeller C.F., Stover P.J. Small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of thymidylate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1760–1763. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woeller C.F., Anderson D.D., Szebenyi D.M., Stover P.J. Evidence for small ubiquitin-like modifier-dependent nuclear import of the thymidylate biosynthesis pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17623–17631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]