Abstract

Type I spiral ganglion neurons have a unique role relative to other sensory afferents because, as a single population, they must convey the richness, complexity, and precision of auditory information as they shape signals transmitted to the brain. To understand better the sophistication of spiral ganglion response properties, we compared somatic whole-cell current-clamp recordings from basal and apical neurons obtained during the first 2 postnatal weeks from CBA/CaJ mice. We found that during this developmental time period neuron response properties changed from uniformly excitable to differentially plastic. Low-frequency, apical and high-frequency basal neurons at postnatal day 1 (P1)–P3 were predominantly slowly accommodating (SA), firing at low thresholds with little alteration in accommodation response mode induced by changes in resting membrane potential (RMP) or added neurotrophin-3 (NT-3). In contrast, P10–P14 apical and basal neurons were predominately rapidly accommodating (RA), had higher firing thresholds, and responded to elevation of RMP and added NT-3 by transitioning to the SA category without affecting the instantaneous firing rate. Therefore, older neurons appeared to be uniformly less excitable under baseline conditions yet displayed a previously unrecognized capacity to change response modes dynamically within a remarkably stable accommodation framework. Because the soma is interposed in the signal conduction pathway, these specializations can potentially lead to shaping and filtering of the transmitted signal. These results suggest that spiral ganglion neurons possess electrophysiological mechanisms that enable them to adapt their response properties to the characteristics of incoming stimuli and thus have the capacity to encode a wide spectrum of auditory information.

Keywords: accommodation, membrane potential, neurotrophin-3, spiral ganglion, threshold

Introduction

Primary sensory afferents are responsible for accurately conveying external sensory information into higher processing centers of the brain with sensitivity and speed. Most sensory systems accomplish this by decomposing a stimulus into submodalities that are transmitted in parallel. The underlying mechanistic foundation of this process is apparent in the elaborate receptor subtypes and complex afferent innervation patterns that typify the gustatory, olfactory, somatosensory, and visual systems (Wood and Docherty, 1997; Vosshall and Stocker, 2007; Carleton et al., 2010; Dowling, 1979). In contrast, the auditory system is unique in its organizational simplicity. Acoustic information is transmitted into the brain by a single class of primary afferents that make one-to-one connections with inner hair cell sensory receptors (Spoendlin, 1973; Liberman, 1982; Meyer et al., 2009). This organization, which appears at face value to severely limit coding capacity, prompts the question of how the richness and precision of auditory information is sent to the CNS to process the frequency, intensity, timbre, and location of sound that is ultimately perceived (Bizley and Walker, 2010). One goal of this study was to determine whether the intrinsic electrophysiological properties of the neurons themselves may play a role. We focused on the property of accommodation because it is a signature feature used to classify primary afferent submodalities in many sensory systems (Loewenstein and Mendelson, 1965; Cleland et al., 1971; Scroggs and Fox, 1992; Mo and Davis, 1997; Robinson and Chalupa, 1997; Wang et al., 1998).

Our studies show that, based on accommodation and threshold, the overall responses for the population could be placed into three distinct categories, or response modes, and that neurons from older animals could dynamically switch between these modes while preserving many of their basic kinetic features. Therefore, a spiral ganglion neuron having a relatively low threshold could switch from rapid to slow accommodation under appropriate conditions, yet retain its maximal firing frequency. These accommodation categories persisted when neurons were held either at defined holding potentials or at their endogenous resting membrane potentials. Moreover, the underlying electrophysiological parameters that contribute to accommodation and excitability differ in their regulation from those parameters that control timing features. The time courses over which these features change during development are separable, as are their responses to neurotrophin-3 (NT-3).

The structural organization of the organ of Corti is thus augmented by neuronal electrophysiological sophistication. The response modes of spiral ganglion neurons fit into a consistent accommodation profile and, within this stable framework, they are capable of dynamically altering accommodation while retaining other firing characteristics. Further, although the excitability of spiral ganglion neurons decreased during development, we found that their ability to change response modes as induced by membrane depolarization and NT-3 actually increased, thus making them more dynamic with age. Our findings suggest that, rather than being limited by the capabilities of a single class of primary afferent, the peripheral auditory system appears to have the capacity to modulate actively a diverse set of response properties, commensurate with the dynamic nature of the acoustic stimulus that they must encode.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture.

Cochleae were removed from postnatal day 1 (P1)–P14 CBA/CaJ mice of either sex (Jackson Laboratory) as described previously (Liu and Davis, 2007). These ages correspond to prehearing at P1 to ∼P8, hearing onset at ∼P9, and adult hearing by P14 (Mikaelian and Ruben, 1965), which correspond to important developmental and functional milestones. Briefly, the most basal and apical fifth of the spiral ganglion were isolated for tissue culture and plated as explants without exposure to enzymatic treatments. Tissues were positioned onto the center of poly-l-lysine-coated dishes and maintained in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mm l-glutamine, and 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin) for 3–13 d in vitro (DIV) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 95%/5% O2/CO2. The majority of recordings, >90%, were performed between 6 and 10 DIV. The neuronal electrophysiological properties were not affected by the range of DIV (Adamson et al., 2002a and confirmed herein); therefore, the data were grouped. Procedures performed on CBA/CaJ mice were approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board for the Use and Care of Animals (IRB-UCA protocol 90–073).

Electrophysiology.

Filamented borosilicate glass capillary tubes (catalog #BF150-110-10; Sutter Instruments) were pulled on a two-stage vertical puller (PP-83; Narishige). Electrodes were coated with silicone-elastomer (Sylgard; Corning) and fire polished (MF-83; Narishige) just before use. Electrode resistances ranged from 3 to 6 MΩ in the pipette and bath solutions used for this study. Pipette offset current was zeroed just before contacting the cell membrane. Current-clamp measurements were made using the Ifast circuitry of the Axopatch 200A amplifier to reduce improper error currents (Magistretti et al., 1996; Magistretti et al., 1998). The internal solution contained the following (in mm): 112 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, and 10 HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5. The bath solution contained the following (in mm): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.7 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 17 glucose, 13 sucrose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.5; ∼330 mOsm. A liquid junction potential of −5 mV was not corrected.

Recordings were made from neuronal somata at room temperature (RT; 19–22°C). Because the cultures contain neuronal and non-neuronal cells, neurons were confirmed by the presence of a large, transient inward sodium current in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode with a depolarizing voltage step from −60 mV to −30 mV that could be blocked by 0.2 μm tetrodotoxin (Liu et al., 2014). For current-clamp recordings, current steps of 240 ms duration were elicited every 5 s in 10 pA increments. Parameters assessed include action potential (AP) latency and duration, voltage threshold, and accommodation (also referred to as APmax, measured as the maximum number of APs fired in response to suprathreshold stimulation). These parameters were chosen based on their relevance to the auditory system. For example, the difference in timing in the arrival of sound waves to the two ears provides directionality, so analysis of AP parameters such as latency and duration are critical to this timing-based sensory system. Excitability differences such as voltage threshold are important for auditory threshold detection and are also generally important to primary sensory afferents. Finally, accommodation is a widely used feature among primary sensory afferents for encoding sensory information. Voltage threshold was measured as the peak amplitude of the just-subthreshold response using 1 pA increments. A holding potential of −80 mV was chosen to assess responses at a level in which there is minimal voltage-dependent ion channel inactivation. Input resistance was calculated from the slope of the linear region fitted between −80 mV and −60 mV for the voltage to current relationships. For Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, the holding potential was also depolarized to −60 mV to compare accommodation levels with the −80 mV holding potential recordings. Data were digitized at 10 kHz with a CED Power 1401 interface using an IBM-compatible personal computer and filtered at 2 kHz; the programs for data acquisition and analysis were written and generously provided by Dr. Mark R. Plummer (Rutgers University). Acceptable current-clamp recordings met the following criteria: low noise levels (<4 mV peak-to-peak; typically <1 mV peak-to-peak), stable membrane potentials, discernible membrane time constant on step current injection, and overshooting APs (magnitudes of ≥80 mV from baseline).

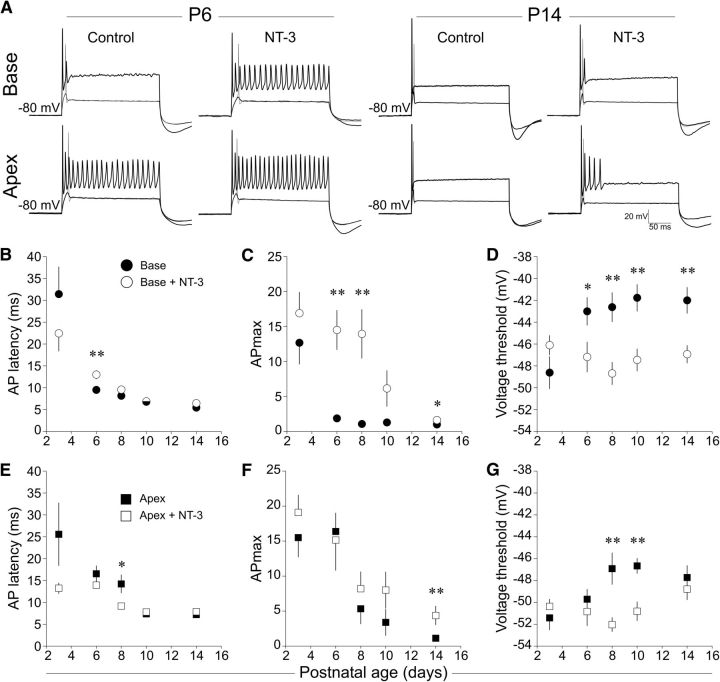

Figure 7.

Differential sensitivity of timing and excitability features to NT-3 exposure suggest distinct regulatory mechanisms. A, Representative whole-cell current-clamp recordings from P6 (left) and P14 (right) neurons from base (top row) and apex (bottom row) under vehicle control and NT-3 treatment conditions. When held at −80 mV, the AP latencies of P6 basal neurons became slower, as did accommodation after exposure to NT-3. By P14, a less robust, though statistically significant, increase in APmax was observed for both basal and apical neurons. B–D, Effects of NT-3 on basal neuron AP latency (B), APmax (C), and voltage threshold (D) for P3, P6, P8, P10, and P14 neurons, as indicated. None of the parameters tested in P3 neurons were modified by exposure to NT-3. The effect on AP latency was only significant at P6 (B). The effect on APmax generally persisted through to P14, but with declining efficacy (C). Voltage thresholds were consistently reduced regardless of postnatal age (D). E–G, Effects of NT-3 on apical neuron AP latency (E), APmax (F), and voltage threshold (G). The effects of NT-3 on these apical neuron properties were generally limited temporally and efficaciously and are consistent with previous studies. For B–D, n = 9, 15, 15, 14, and 13 for control and n = 10, 13, 16, 14, 22 for NT-3 for P3, P6, P8, P10, and P14, respectively; for E–G, n = 10, 16, 15, 13, and 16 for control and n = 11, 14, 15, 17, and 11 for NT-3, respectively.

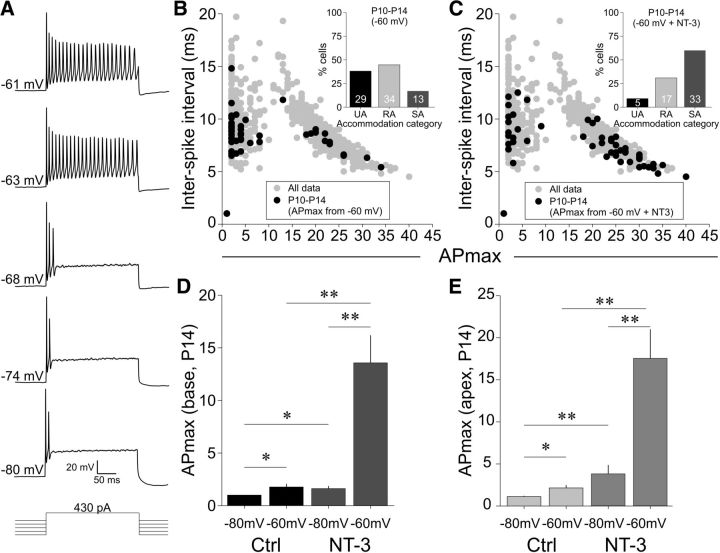

Figure 8.

Membrane depolarization and NT-3 exposure dramatically enhanced APmax, causing the accommodation categories to shift. A, Stacked sweeps from a P14 neuron exposed to NT-3 show the change in firing with holding potential depolarization while the test current injection remained constant (430 pA as shown). Scale bars for the sweeps are displayed with the bottom sweep. B, C, Plots of ISI versus APmax for P10–P14 cells when held at −60 mV (B, black circles) and when held at −60 mV + NT-3 exposure (C, black circles). Insets, Percentage of cells per APmax category. Note the shift in the percentage of cells that now fall into the SA category (compare with Fig. 4D). D, P14 basal neurons had a slight increase in APmax with the change in holding potential (−80 to −60 mV) under vehicle control conditions and a robust increase in APmax when neurons were exposed to NT-3 and also depolarized to −60 mV holding potential. For control (−80 mV to −60 mV), n = 18; for NT-3 (−80 to −60 mV), n = 20. E, Similar to D, membrane potential depolarization and NT-3 exposure strongly affected APmax in P14 apical neurons. For control (−80 mV to −60 mV), n = 14; for NT-3 (−80 to −60 mV), n = 14.

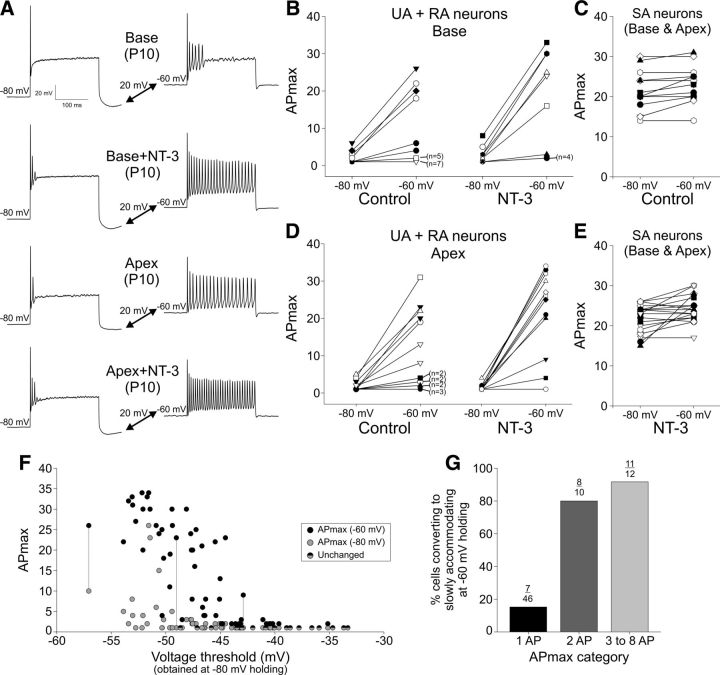

Figure 9.

The combination of membrane depolarization and NT-3 exposure unmasks the slowly accommodating phenotype in P10 neurons. A, Representative sweeps demonstrate the effect of membrane potential and NT-3 on APmax. Base control and NT-3 (top two sets of sweeps) from P10 neurons at a holding of −80 mV and then depolarized to −60 mV. P10 apical neuron recordings from control and NT-3-exposed conditions (bottom two sets of sweeps). The combined effect was robust regardless of location. The instantaneous rates for the second, third, and fourth sweeps are identical at −80 and −60 mV (147, 115, and 161 Hz, respectively). B, For UA and RA neurons, membrane potential depolarization from −80 mV to −60 mV increased APmax under vehicle control conditions and NT-3 exposure markedly enhanced this effect, as shown by the vertical shift in APmax. A line connecting two points is the response of an individual cell at the two different holding potentials and the n's beside some of the points denote multiple cells with that response. D, Same experiment and similar results as in B, but for UA and RA P10 apical neurons. C, E, Membrane potential depolarization had essentially no effect when neurons were initially SA at −80 mV for vehicle control neurons (C) and NT-3-treated neurons (E). For C and E, both basal and apical neurons were combined across multiple age groups. F, Comparison of APmax versus voltage threshold (obtained at −80 mV) for P10 neurons for which APmax was tested at both −80 (black circles) and −60 mV (gray circles). Neurons that were unchanged had an APmax of 1 and are shown by the half-black/half-gray circles. Each gray symbol (−80 mV) is paired vertically to a black symbol (−60 mV). This is illustrated by the three experiments that are connected with dotted vertical lines. G, Depolarization robustly increased APmax primarily for those neurons that fired at least 2 APs at −80 mV. Plotted is the percentage of cells that converted to SA when depolarized to −60 mV holding. The number of cells responding divided by the total number of cells is shown above each bar.

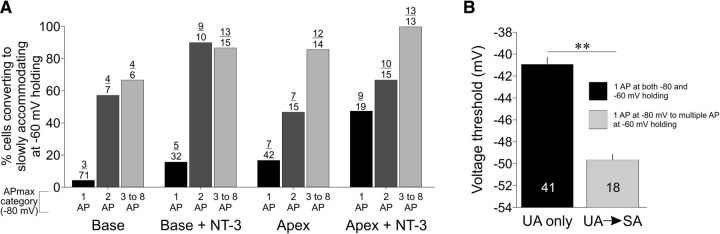

Figure 10.

Voltage threshold predicts the probability that spiral ganglion neurons will convert from RA to SA. A, Plot of all neurons in which accommodation was tested at both holding potentials and displayed as the percentage of cells that converted to SA when depolarized to −60 mV holding. Depolarization promoted conversion to SA primarily for those neurons that fired at least 2 APs at −80 mV under control and NT-3 treatment conditions from either cochlear location. Note that NT-3 exposure increased the percentage of cells that converted to SA for both basal and apical neurons. The number of cells responding divided by the total number of cells is shown above each bar. B, Voltage threshold was compared for two distinct classes of neurons, those that only fired 1 AP regardless of holding potential or NT-3 exposure (UA, black bar) and those that fired 1 AP at −80 mV but then converted to SA at −60 mV holding (UA to SA, gray bar). The voltage threshold was significantly different for these two classes of cells. The n's are shown within the bars and the asterisks indicates statistical significance.

Figure 11.

Membrane depolarization and NT-3 treatment promote a shift from RA to SA without a change in firing rate in P10 and P14 neurons. A, Stacks of sweeps from the same P14 neuron held at −80 mV (left) and then −60 mV (right). Note that, as the test current injection is increased, the number of APs differs between the two holding potentials, but the firing rates do not differ when the sweeps are aligned according to plateau voltage (dashed lines with value in mV). At the top of the sweeps is an expanded time scale of the first 3 APs showing the high degree of overlap. The gray triangle beneath the sweeps is the same experiment shown for the analyses in B and C. B, Number of APs for five different neurons when held at −80 mV (black symbols) and then at −60 mV (open symbols; gray symbol is the experiment shown in A) plotted as a function of plateau membrane voltage (mV). Note the transformation in firing with the change in holding potential. C, Comparison of ISI vs APmax for neurons that had an APmax of 2 at −80 mV and their subsequent ISI versus APmax at −60 mV. Despite the heterogeneity in ISI and APmax, an individual neuron's ISI remained stable with the change in holding potential and firing. The gray symbol represents the experiment shown in A, which had an APmax of 6 at −80 mV.

Measurements of interspike interval (ISI), instantaneous rate, sustained rate, and plateau voltage level were obtained from whole-cell current-clamp recordings. As shown graphically in Figure 2C, inset, ISI was measured as the difference in time between the first two APs. Instantaneous rate is presented as the reciprocal of ISI (1/ISI). Sustained rate, as shown in Figure 2D, inset, was measured as the number of APs divided by the AP train duration. Both instantaneous and sustained rates were converted from milliseconds to seconds. The plateau voltage was measured as the membrane potential at the end of the test pulse for rapidly accommodating neurons. For slowly accommodating neurons that fired for the duration of the test pulse, the plateau voltage was estimated by averaging the voltage for the duration of the test pulse (Mo and Davis, 1997). By applying the same method to rapidly accommodating neurons and comparing that value with the value obtained by direct measurement of the end of the test pulse, we confirmed that this method generates a very close approximation of the direct measurement.

Figure 2.

Diversity of neuronal firing patterns within an overlapping range of rates. A, Stacks of sweeps from three different experiments highlight the heterogeneity of firing patterns observed. Step current injections are shown below each stack, with the number and symbol representing the recording displayed in the graphs below. Holding potential: −80 mV. B–G, Analyses representing the breadth of individual recordings of RA neurons (n = 11; B–D) and SA neurons (n = 15; E–G). B, E, Plots of the number of APs versus plateau voltage level (see Materials and Methods) for RA (B) and SA (E) neurons. B shows a tighter voltage range with relatively sharp peaks for the APmax. E shows a wide range of AP values that were heterogeneous both for the total number of APs and also the voltage range. Note that the voltage level that SA neurons (E) begin to fire multiple APs is more hyperpolarized than the RA neurons (B). C, F, Plots of instantaneous rate. D, G, Plots of sustained rate. The insets in C and D indicate how the measurements were derived, with instantaneous rate being the reciprocal of ISI, and all values were converted from milliseconds to seconds. Scale bars for the sweeps are indicated at the bottom of the third column of sweeps.

Calculation of the endogenous resting membrane potential (RMP) was initially described by Verheugen et al. (1999) and performed according to Liu et al. (2014). Cell-attached single K+ channel recordings (mean conductance of 44 pS) were used to measure noninvasively the RMP, which was calculated based on the K+ reversal potential. The internal solution utilized contains essentially equimolar [K+] across the membrane, which zeroes the net flow of K+ current at 0 mV. Therefore, the direction of the single-channel current depends on the pipette voltage and the current reverses when the pipette voltage equals the RMP. HCN or Cl− channel contamination was ruled out based on the small conductance of HCN and the unequal [Cl−] across the membrane. Use of K-gluconate internal solution confirmed K+ selectivity (Liu et al., 2014). After entry into whole-cell mode, the current injection level was set to the calculated, endogenous RMP and APmax was then assessed. This noninvasive method provides a more accurate method of obtaining RMP because breaking into a cell can alter RMP. Based on the internal solution, RMP values obtained with zero injected current are expected to be depolarized by ∼5 mV on average (Liu et al., 2014).

NT-3 (Peprotech) was prepared as a stock solution from lyophilized powder using sterile water. The stock solution was diluted with sterile distilled water and added at time of plating to a final concentration of 10 ng/ml (1:1000 dilution). This concentration was chosen because it yielded the maximal change in accommodation (Zhou et al., 2005). Vehicle control was 10 μl of sterile distilled water added at time of plating. NT-3 and vehicle control recordings were performed at 6–7 DIV and were typically assessed concurrently from sister cultures. All recordings (untreated, vehicle control, and NT-3) were performed from multiple platings and animals.

Kv1.1 immunocytochemistry.

To compare anti-Kv1.1 immunolabeling at distinct developmental time points, spiral ganglion explants were isolated from P3 and P8 animals on the same day so that fixation, staining, and data acquisition could be performed simultaneously for comparative purposes. After culturing neuron explants for 6 DIV, immunostaining patterns were similar for tissue fixed with either 4% paraformaldehyde (6 min at RT), followed by 0.1% Triton X-100 (15 min at RT) or 100% methanol (6 min at −20°C) and rinsed 3× with 0.01 m PBS, pH 7.4, for 5 min. The tissue was incubated with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h to block nonspecific labeling. Primary antibody was then applied for 1 h at RT and then rinsed 3× with PBS for 5 min. Fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, 1:100, catalog #A11070; Life Technologies; or anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594, 1:100, catalog #A11020; Life Technologies) was subsequently applied for 1 h at RT. The preparations were then rinsed 3× with PBS for 5 min. Finally, 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) was applied for viewing and storage. Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera fitted on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope that was controlled using IPLab software (Scanalytics). Exposure times were held constant when acquiring images within each experiment. Antibody luminance was measured in IPLab with no digital enhancement using a box tool with an area of either 10 × 10 or 15 × 15 pixels to subtract the mean of four background areas from the mean of the three brightest areas inside each neuron. A single experiment consisted of luminance measurements from a minimum of 175 neurons obtained from P3 and P8 apical and basal spiral ganglia isolated on a single day and processed identically; statistical analyses were based on 3 separate experiments. The primary antibodies were as follows: polyclonal Kv1.1 (1:150, catalog #APC-009; Alomone Labs) and neuron-specific class III β-tubulin (1:200, catalog #MMS-435P; Covance). For the display of images in Figure 5A, the brightness, contrast, and gamma were adjusted equally for either the Kv1.1 or β-tubulin antibodies, respectively, using IPLab and Adobe Photoshop.

Figure 5.

Changes in anti-Kv1.1 antibody luminance during the first postnatal week are correlated with concomitant changes in electrophysiological features. A, Representative images of Kv1.1 immunolabeling (green, top) in P3 and P8 basal neurons, respectively, showing the increase in relative Kv1.1 protein levels from P3 to P8 in β-III-tubulin positive (red, bottom panels) spiral ganglion neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm, bottom right applies to all images. B, Average luminance from three separate experiments showing enhanced Kv1.1 protein levels for both basal and apical neurons. Note the emergence of tonotopic differences in Kv1.1 luminance by P8. Asterisks indicate statistical differences (n = 3).

Statistical analyses.

Student's two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed in Microsoft Excel to compare interregion means at a specific age; for example, voltage thresholds between base and apex at P7. For intraregion comparisons (e.g., base threshold vs postnatal age), N-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc pairwise analysis. ANOVA results were obtained with Matlab (Mathworks). A p value <0.05/0.01 denotes a significant difference and is shown with an asterisk (* and **, respectively) unless otherwise indicated. The data are displayed as mean ± SEM, as indicated.

Results

To determine the full range of firing characteristics of spiral ganglion neurons, we provide a composite snapshot of 972 recording paradigms from neurons ranging in age from newborn through hearing onset (P1-P14) encompassing those isolated from the basal, high-frequency to the apical, low-frequency regions with and without 10 ng/ml NT-3 at a holding potential of −80 mV (n = 594), a portion of these (n = 295) that were also tested at −60 mV, and, finally, cells held at their endogenous RMP (n = 80; Fig. 1). Surprisingly, this diverse group of recordings coalesced into three broad populations based solely on accommodation. These groupings are referred to throughout this study as rapid accommodation (RA; APmax = 2–8; see Materials and Methods for APmax definition), unitary accommodation (UA, APmax = 1; a special case of RA described in Fig. 3), and slow accommodation (SA; APmax = 11 or more). The RA group (light gray circles) ceased firing during the test pulse and was thus distinguished from the SA category (gray circles), which fired for the duration of the 240 ms test pulse. The cessation of firing for RA neurons resulted in an observable gap (between an APmax of 8 and 11) that separated them from SA neurons, which is in close agreement with previous studies (Mo and Davis, 1997). Both of the RA and SA groups spanned a wide range of ISIs from 4.5 to 19.7 ms (Fig. 1). This was seen most clearly in the SA neurons because they formed a function extending from neurons with long ISIs, firing relatively few APs (APmax = 11) to neurons with brief ISIs firing up to 40 APs. Although SA neurons fired throughout the test pulse, the APmax versus ISI function was nonlinear and best fitted with a single exponential (R2 = 0.73). The upper limits were likely affected by declining AP and after-hyperpolarization durations, whereas the lower limits were affected by a modest amount of spike-frequency adaptation. Nevertheless, these data show that, although individual neurons have distinct properties, together, they represent a wide range of instantaneous firing frequencies that range from 50 to >200 Hz.

Figure 1.

Spiral ganglion neuron firing falls into separable categories based on accommodation. The graph displays ISI (ms) versus APmax (maximum number of APs at suprathreshold stimulation) for 972 experimental paradigms as described in the Results. RA neurons (light gray circles) fire one AP (assigned an ISI of 1) or cease firing during the 240 ms test pulse. Conversely, SA neurons (dark gray circles) fire throughout the test pulse. Representative sweeps are shown for each category. From these experiments, we observed that the slowest SA neuron (13 APs as shown) will never fire like the fastest neuron (40 APs), indicating that firing rates are not interchangeable. The red line is a single exponential fit (R2 = 0.73) to the SA data (dark gray circles only).

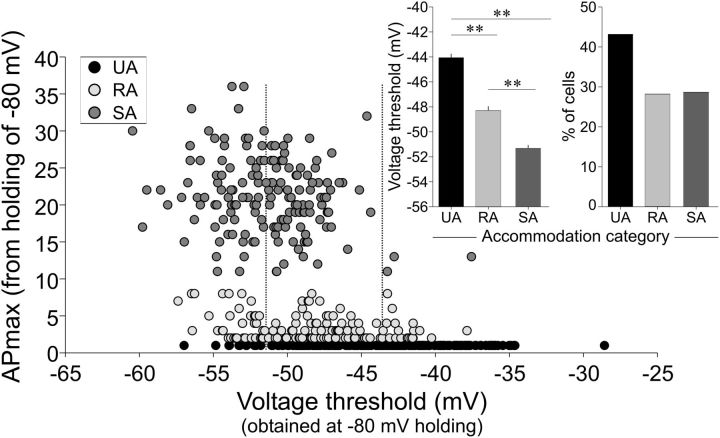

Figure 3.

Voltage thresholds reveal a third distinct accommodation category. Individual control and NT-3 recordings were grouped by APmax according to Figure 1 and threshold level. APmax = 1 (unitary accommodation, UA, black circles, n = 250), APmax = 2–8 (RA, light gray circles, n = 163), and APmax = ≥11 (SA, dark gray circles, n = 166). Both voltage threshold and APmax were obtained at −80 mV. The insets plot voltage threshold (left) and percentage of cells (right) as a function of accommodation category (UA, RA, and SA). The voltage threshold plot confirmed that accommodation was significantly related to threshold. The two vertical black dotted lines in the scatter plot demarcate the mean SA and UA voltage thresholds.

Although the RA and SA classes of accommodating neurons were clearly distinguished, this type of analysis is essentially a single view of a neuron's firing capabilities at one defined voltage level. To extend our analysis, we further evaluated neuronal firing profiles at a series of depolarizing step potentials. The data in Figure 2 provide an analysis of rate/level functions to illustrate the wide dynamic range of spiral ganglion neuron firing properties. Representative current-clamp recordings, chosen to illustrate the breadth of individual response profiles, were categorized as described previously (Mo and Davis, 1997; Adamson et al., 2002a) and based on Figure 1, RA or SA. These recordings were characterized according to the number of APs elicited over a large voltage range (RA, Fig. 2B; SA, Fig. 2E) and were also analyzed for rate/level functions for which the level was set at the plateau membrane voltage (Fig. 2C,D and F,G, respectively). Shown in the example current-clamp recordings (Fig. 2A) and accompanying plots (Fig. 2B,E) are cells that range in accommodation and voltage sensitivities. Column 1 (light gray squares) typifies RA neurons that fired multiple APs but ceased firing during the test pulse. The recording in column 2 (gray circles) fired at a similar rate as the neuron in column 1, but is SA because it fired for the duration of the test pulse. The recording in column 3 (white circles) is also SA, but it showed a distinctly different firing rate from that in column 2. Therefore, even though the neurons in columns 2 and 3 are SA, they possess distinctly different firing profiles, which indicates that the information they encode may differ subtly. In addition, the voltage sensitivities were diverse. For example, the recording in column 3 showed multiple APs at a low voltage (−53 mV) that increased to >30 APs over a 20 mV range (from ∼−40 mV to −20 mV, see profile in Fig. 2E). RA neurons, such as the example in column 1, generally had depolarized thresholds that required higher current injections to fire more than a single AP. They also had much sharper APmax peaks compared with SA neurons, which plateaued, and thus lasted over a wider voltage range (cf. Fig. 2B,E). Shown in Figure 2, C and D, and Figure 2, F and G, are rate/level functions for RA and SA neurons, respectively, which further highlights their distinctive features. These data show that, whereas the APmax differed dramatically between categories of neurons (cf. Fig. 2B,E), the ranges of rates were similar (cf. Fig. 2C,F), indicating that they may be derived from similar populations but with slightly different types and/or ratios of ion channels that sculpt their firing profiles. These data highlight the diversity of voltage threshold and firing sensitivities of spiral ganglion neurons that cover a wide range in terms of both voltage and APmax.

Although accommodation can have a profound effect on sensory afferent signal coding and is a valid distinguishing feature between neurons, we next investigated whether there was an independent measure that would further separate the accommodation categories distinguished by our APmax versus ISI analysis (Fig. 1). RA neurons had elevated threshold levels compared with SA neurons (Fig. 2B,E); therefore, we evaluated directly the threshold levels from the full pool of recordings obtained with our standard holding potential of −80 mV. From this analysis, we found that, although a wide range of voltages were observed, those that fired only a single AP (UA neurons) had the greatest representation at the most depolarized voltage threshold levels, RA neurons (i.e., APmax = 2–8) populated the middle, and SA neurons were shifted to lower voltage thresholds, especially as APmax increased (Fig. 3). When the data were then grouped according to accommodation category, we found that voltage thresholds correlated significantly with APmax such that the single-spiking UA cells had the highest voltage thresholds and thus represent a distinct subcategory of RA neuron. SA neurons had the lowest voltage thresholds and the RA category was intermediate (UA: −44.1 ± 0.3 mV; RA: −48.3 ± 0.3 mV; SA: −51.3 ± 0.2 mV, p < 0.001 for all comparisons; Fig. 3, inset). Together, these data highlight the relationship of voltage threshold to spiral ganglion neuron firing that is shown in Figures 1 and 3 and supports three categorical groupings based on accommodation.

Although 95% of the spiral ganglion is composed of apparently identical type I neurons, the data in Figure 3 suggest that three separate categories can be defined based on their intrinsic firing patterns. However, because the data shown in Figures 1 and 3 are comprised of a composite of neurons removed from specific locations, with a wide range of ages, with and without NT-3, and held at different voltage levels, it is possible that each condition could merely comprise a single category. We therefore subdivided the data to determine whether the firing patterns were distinguished by postnatal age.

By highlighting the data obtained from different aged animals superimposed on the entire dataset, we observed a progression of firing patterns and found that it was the percentage of neurons within each category that shifted over time, not the categories themselves. Figure 4, A–D, describes the changes in ISI versus APmax as a function of age (black circles) overlaid on the full dataset shown in Figure 1A (gray circles); the insets for each figure show the percentage of cells in each accommodation category (all recordings in this figure were assessed at −80 mV holding potential). In Figure 4A, only 1.5% of P1–P2 neurons were UA, with the majority of cells (64.6%) falling into the SA category, thus demonstrating a high level of excitability. As postnatal age increased (P3–P5, P6–P8, and P10–P14; Fig. 4B–D, respectively), the percentage of cells in each category progressively shifted such that, by P14, >75% of the cells were UA. Therefore, unexpectedly, despite differences in the percentage of neurons that compose the three categories highlighted in the total dataset (gray circles), the three accommodation classifications remain unchanged.

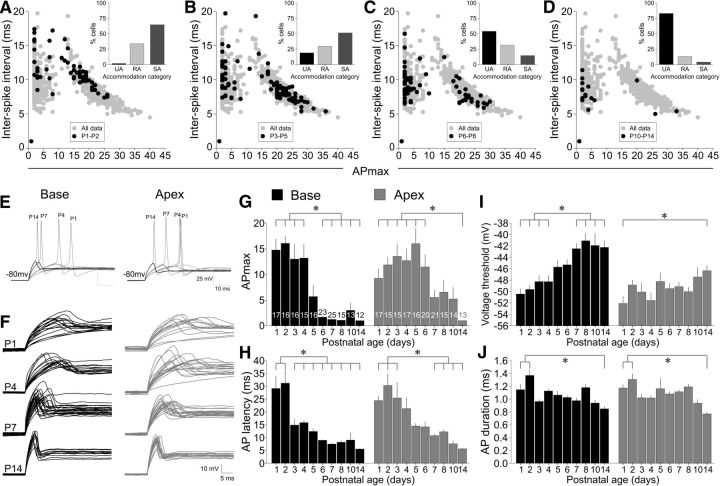

Figure 4.

Differences in the rates of change for timing versus excitability features suggest distinct regulatory mechanisms within a stable accommodation framework. A–D, Overlay of ISI versus APmax data. The black circles are the ages indicated and the gray circles are from Figure 1 for comparison. Insets show the percentage of cells in each accommodation category (UA, RA, and SA). Shown are P1–P2 (A), P3–P5 (B), P6–P8 (C), and P10–P14 (D). Note that the data continue to support the existence of three discrete categories, with the percentage of cells within each category shifting as postnatal age increases. E, Representative sweeps from basal (left) and apical (right) neurons demonstrate the changes in AP latencies and voltage thresholds at P1, P4, P7, and P14. Note the age-related reductions in latency (both regions) and elevations in threshold (most evident in the base). Sweeps reflect the grouped data means in H and I. F, Overlaid threshold sweeps from all basal (left) and apical (right) neuron recordings at P1, P4, P7, and P14. As postnatal age increased, the heterogeneity in timing was reduced, but the heterogeneity in threshold levels persisted. Some threshold responses for P1 neurons from both regions and one P4 apical neuron are too long to fit in the time window displayed. G, APmax levels in response to suprathreshold stimulation start relatively high in both regions and decline faster in the base relative to the apex. Both fire, on average, a single AP by P14. H, AP latency declined in both regions, but ∼2 d faster in the base relative to apex. Also note that AP latency changes temporally precede APmax changes by ∼2 d. I, Voltage thresholds become elevated, particularly in base neurons, as a function of age. J, Changes in AP duration are relatively modest, reaching significance by P14 compared with P1–P2 neurons. Brackets and asterisks indicate statistical significance. Neurons were held at −80 mV for all assessments in this figure. Scale bar values are displayed with the sweeps. n for G–J are shown in G.

Not only did accommodation shift with age, but we also observed the predicted developmental gradient in vitro: basal neurons changed at an earlier time point than apical neurons. As shown in the bar charts of average APmax at P1–P14 (Fig. 4G), basal neurons shifted to the RA profile well before apical neurons. The highly excitable phenotype of basal neurons at early postnatal ages (average of ∼13 APs from P1–P4) was indistinguishable from apical neurons of the same age, declined to ∼1 AP by P7, and remained at that level until P14. Apical neurons also underwent a change in APmax, but the decline began at ∼P7 and also reached a maximum of ∼1 AP by P14. In addition, we only rarely observed (n = 5) spontaneous APs (Lin and Chen, 2000), which were limited to low-threshold neurons in the earliest postnatal cultures (P1–P3).

Interestingly, the time course of this age-dependent change in the electrophysiological profile of basal and apical neurons differed with respect to AP latency. Although the latency of basal neurons became more rapid at earlier postnatal ages than apical neurons, the abrupt phase of the change occurred at an earlier stage than APmax. This is seen in the example traces from current-clamp recordings (Fig. 4E,F), which are representative of the group data (Fig. 4H). In addition, these traces show that APs (Fig. 4E) were well formed at birth, which is consistent with acute slice recordings from late embryonic mice (Marrs and Spirou, 2012), indicating that the basic complements of ion channels are present before birth. Comparisons between neurons from different cochlear regions show that base neurons possessed relatively long AP latencies from P1 to P2 (P1: 29.1 ± 4.9 ms, n = 17) that became dramatically shorter by P3 (14.9 ± 2.4 ms; n = 16) and then progressively shorter until P14 (5.5 ± 0.2 ms, n = 12; p < 0.05). Apical neurons followed a similar pattern but began to decline ∼1–2 d later at ∼P5 (P1: 24.4 ± 1.9, n = 17; P5: 14.5 ± 1.1 ms, n = 16; P14: 5.6 ± 0.2 ms, n = 13; p < 0.05). AP duration, another timing-related feature, was largely unchanged and only reached statistical significance for either region by P14 (Fig. 4J).

Although voltage thresholds from both cochlear locations became significantly elevated and with reduced latency jitter, as shown in the overlaid sweeps (Fig. 4F), basal neurons showed a pronounced elevation of voltage threshold that changed at a slower time course than APmax and latency yet still occurred more rapidly than for apical neurons. Changes in basal neuron voltage thresholds, which were initially relatively hyperpolarized (P1: −50.4 ± 0.9 mV), became more depolarized during the first postnatal week (P7: −42.5 ± 0.9 mV; p < 0.05) and then stabilized during the second postnatal week (P14: −42.3 ± 1.2 mV, p > 0.88). In contrast, apical neurons manifested a more gradual change in voltage thresholds that achieved statistical significance only by P14 relative to P1 (P1: −51.9 ± 1.3 mV; P14: −46.3 ± 0.9 mV, p < 0.05; Fig. 4I). Tonotopic differences in voltage thresholds achieved significance by P6 (−49.5 ± 0.9 mV, −45.3 ± 0.9 mV, respectively; p < 0.01) and retained this difference through P14 (−46.3 ± 0.9 mV, −42.2 ± 1.2 mV, respectively, p < 0.05). Despite the complex, age-related changes that were observed for each of the electrophysiological parameters examined, the consistent blueprint of their accommodation remained unchanged. Whether a neuron was removed from the animal 1 d or a full 2 weeks after birth, the overall profile of their firing features remained stable. Neurons fired a single AP, multiple APs with rapid accommodation, or displayed slow accommodation. The dynamic aspect of their profile, however, was the percentage of cells within each category and how rapidly the neurons were capable of firing.

Notably, the changes in firing features during development were largely complete by the end of the first postnatal week. We next investigated whether these changes correspond to age-related changes in Kv1.1 protein expression, a channel type known to regulate voltage threshold, RMP, and accommodation (Liu et al., 2014). We quantified the relative differences in anti-Kv1.1 antibody immunolabeling and found that it increased significantly between P3 and P8 in both basal and apical neurons and also manifested in a tonotopic distinction, which likely explains the persistence of tonotopic differences in voltage threshold. Shown in Figure 5A are representative images that display the age-related changes in Kv1.1 immunostaining in P3 basal versus P8 basal neurons. These changes were quantified for both basal and apical neurons and are graphed as average luminance in Figure 5B (P3 base luminance: 393.5 ± 12.0; P3 apex: 349.4 ± 11.7; P7 base: 702.4 ± 17.7; P7 apex: 510.5 ± 12.8; n = 3; see figure and legend for statistical comparisons). Changes in luminance are not necessarily correlated with alterations in surface-expressed ion channels, however, we have found that immunocytochemistry broadly correlates with pharmacological assessments using patch-clamp electrophysiology (Adamson et al., 2002b; Chen et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014). Specifically, anti-Kv1.1 antibody luminance levels in apical and basal postnatal spiral ganglion neurons were consistent with whole-cell voltage-clamp α-dendrotoxin-sensitive difference currents (Liu et al., 2014). These differential alterations in Kv1.1 immunostaining and timing and excitability features were accompanied by significant changes in input resistance for basal neurons (P3 base: 258.3 ± 0.02 MΩ, n = 14; P7 base: 192.6 ± 0.01 MΩ, n = 9; p < 0.05), whereas trends for P3 and P8 apical neurons were also consistent with immunocytochemical results, the differences were not significant (P3 apex: 276.7 ± 0.03 MΩ, n = 18; P8 apex: 235.7 ± 0.02 MΩ, n = 13; p > 0.3). Accordingly, we also observed that the RMPs of P1 basal neurons were significantly more depolarized than P8 basal neurons (P1 base: −56.0 ± 0.7 mV, n = 17; P8 base: −62.4 ± 0.8 mV, n = 15, p < 0.05). Changes in apical neuron RMP did not reach significance until P14. These data indicate that, as postnatal age increases, spiral ganglion neurons may incorporate Kv1.1 channels, which consequently affects input resistance, RMP, and firing features.

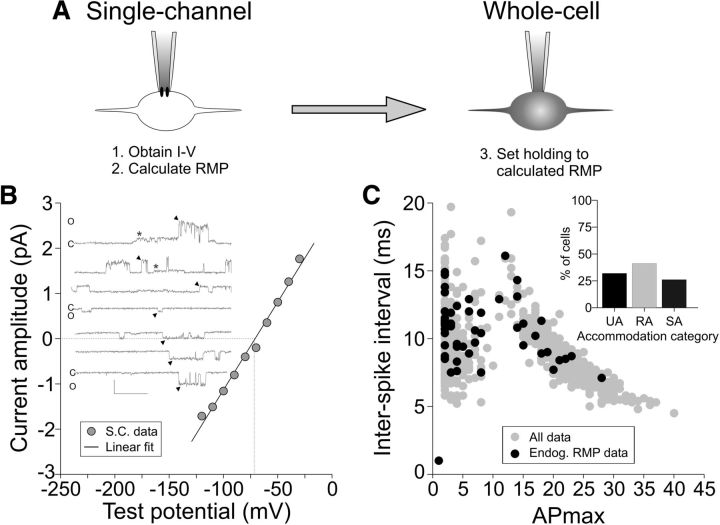

The experiments presented thus far used a defined holding potential (−80 mV) to establish and compare the electrophysiological features of spiral ganglion neurons from birth through hearing onset. However, the RMP of these neurons is typically more depolarized when assessed in vitro (Rusznák and Szûcs, 2009). Although it is customary to measure the endogenous RMP using standard whole-cell current-clamp techniques, we have recently used a noninvasive method to measure the endogenous RMP (Verheugen et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2014). We therefore calculated the endogenous RMP non-invasively in P6–P7 cultures of 36 basal and 44 apical neurons and observed a range of RMP from −53 mV to −78 mV. We held each cell at its calculated, endogenous RMP to assess accommodation and, consistent with the −80 mV data (Fig. 4C), we observed the three accommodation categories but with a shift in the percentage of cells from UA toward the RA and SA categories (Fig. 6). The similarity in accommodation categories when using a defined holding potential versus the calculated RMP indicates their stability and the shift in the percentage of cells within each category highlights their dynamic nature and indicates a direct effect of holding potential on accommodation.

Figure 6.

Noninvasive measurement and holding of neurons at the calculated, endogenous RMP confirms the distribution of the three accommodation categories. A, Single-channel patch-clamp recording was used to obtain an I–V (step 1) from which the endogenous RMP was calculated based on the K+ reversal potential (step 2). The cell was then set to the calculated, endogenous RMP in whole-cell mode (right, step 3). B, Example single-channel recording of a P6 basal neuron at a range of holding potentials and the I–V relationship for this recording. The larger channel (denoted by arrowhead) had a conductance of 38.9 pS and a reversal potential of −70.8 mV (denoted by vertical dotted line) for this cell. The smaller channel (*) was not analyzed. Scale bar, 10 pA, 50 ms. C and O beside individual sweeps refer to the channels being closed or open, respectively. C, Comparison of the ISI versus APmax for all recordings (n = 80) using the endogenous RMP. Inset shows the percentage of cells for each accommodation category.

These results suggest that, as developmental processes proceed, cells move between different accommodation categories without altering the overall framework. To determine potential mediators of these changes, we examined the effects of NT-3, the expression of which is reduced during this same time period. Based upon previous studies, we expected that P5 basal spiral ganglion neurons would be converted from RA to SA, that voltage thresholds would be reduced, and that latencies would be prolonged after exogenous application of NT-3 (Adamson et al., 2002b; Zhou et al., 2005). Here, we expanded on those observations by assessing the effects of NT-3 (10 ng/ml) on basal and apical neurons by examining both earlier (P3, slower but highly excitable), intermediate (P8), and later (P10-P14, faster but reduced excitability) time points. As shown by the representative traces (Fig. 7A) and the group data (Fig. 7B–D), we confirmed our previous results in P6 basal neurons that NT-3 exposure prolonged AP latencies (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 9.5 ± 0.6 ms vs 13 ± 1.1 ms, p < 0.01), increased APmax (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 1.9 ± 0.5 APs vs 14.5 ± 2.8 APs, p < 0.01), and lowered voltage thresholds (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: −43 ± 1.3 mV vs −47.2 ± 1.4 mV, p < 0.05). NT-3 exposure to P3 neurons from either region (Fig. 7B–D,E–G) did not significantly alter AP latency (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 31.4 ± 6.3 ms vs 22.4 ± 4.1 ms, p > 0.24), APmax (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 12.7 ± 3.1 APs vs 16.9 ± 3.0 APs, p > 0.2), or voltage thresholds (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: −48.6 ± 1.5 mV vs −46.1 ± 0.9 mV, p > 0.16), indicating a ceiling effect possibly due to the already high level of excitability possessed by these neurons. P8 base neurons responded equally well to NT-3 application as P6 base neurons, both in terms of increased APmax (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 1.1 ± 0.1 APs vs 13.9 ± 3.5 APs, p < 0.01) and lowered voltage thresholds (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: −42.6 ± 1.3 mV vs −48.7 ± 1.0 mV, p < 0.01). AP latencies were numerically but not significantly prolonged (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 8.2 ± 0.7 ms vs 9.6 ± 0.8 ms, p > 0.21). Interestingly, the effect of NT-3 in basal neurons appeared to diminish as the postnatal age increased such that AP latencies were not significantly different for P10 (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 6.8 ± 0.1 ms vs 6.9 ± 0.5 ms; p > 0.89) or P14 neurons (6.6 ± 0.4 ms vs 6.4 ± 0.2 ms; p > 0.8). Accordingly, APmax was nearly significant for P10 neurons (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 1.3 ± 0.2 APs vs 6.1 ± 2.6 APs, p > 0.07) and significantly different for P14 neurons (vehicle control vs NT-3 exposed: 1.0 ± 0.0 APs vs 1.6 ± 0.2 APs, p < 0.05), but the overall magnitude of the response was clearly reduced. However, the effect on voltage threshold did not diminish, but rather remained equally sensitive to modulation by NT-3 (Fig. 7D) from P6 to P14 (NT-3 exposed: P6, −47.2 ± 1.4 mV; P8, −48.9 ± 1.0 mV; P10, −47.4 ± 1.0 mV; P14, −46.9 ± 0.8 mV; see figure for statistical comparisons). In contrast to basal neurons, apical neurons responded less robustly across all ages, which is consistent with a previous report (Adamson et al., 2002a; see figure legend for details). The effects of NT-3 on basal neurons suggest that timing features such as latency and APmax (which may be a mixture of timing and excitability) are regulated differently than voltage threshold in response to trkC activation. In addition, the consistent effect of NT-3 on voltage thresholds indicates that the decline in the other parameters was not due to reduced trkC expression and further highlights the differential regulation of these parameters. Given the low concentration of NT-3 used in this study, the most parsimonious explanation of the results is that NT-3 works through trkC-dependent pathways, because the involvement of p75NTR receptors is unlikely based on reports that it is not expressed in spiral ganglion neurons after birth (Tan and Shepherd, 2006; Provenzano et al., 2011).

By P14 and in the absence of applied NT-3 (Fig. 4), age-related changes in timing and excitability features, with the exception of voltage thresholds, became more homogenous such that tonotopic differences were minimized. However, in P14 spiral ganglion neurons, application of NT-3 significantly reestablished the tonotopic difference of two important features at −80 mV holding potential: latency (base: 6.4 ± 0.2 ms; apex: 7.7 ± 0.3 ms; p < 0.01) and APmax (Fig. 8D,E) while also having the effect of normalizing voltage thresholds (base: −46.8 ± 0.8 mv; apex: −48.5 ± 0.9 mV; p > 0.2). Similarly, at a holding potential of −60 mV, apical neuron latencies were significantly prolonged relative to the base and thresholds again became equivalent. In contrast to the results at −80 mV holding potential, APmax values at −60 mV holding potential were similar between base and apex. Given that NT-3 expression is higher in the apex than the base in vivo, these data suggest that these differences may be further augmented by the graded concentration of NT-3 along the tonotopic axis in vivo (Fritzsch et al., 1997; Fariñas et al., 2001; Sugawara et al., 2007).

Studies on thalamic relay neurons have shown that relatively small changes in membrane potential can have dramatic consequences on neuronal firing (McCormick and Pape, 1990; Kim and McCormick, 1998). The apparent decrement in the effect of NT-3 on APmax from P10 to P14 was surprising given that P8 base neurons responded robustly. Because NT-3 exposure can reduce the expression of some potassium channels and these changes presumably underlie the effect on basal neurons, we wondered whether P10-P14 neurons, which are generally less excitable, contained an intrinsic barrier that may be posed by an elevated density of potassium channels that attenuated the effect of NT-3. Further, given the observed shift in accommodation categories when holding the neurons at their more depolarized, endogenous RMP (Fig. 6), we hypothesized that an effect of NT-3 on spiral ganglion neurons obtained from these older animals could be unmasked by changing the holding potential from −80 mV to −60 mV, a more physiological voltage (average: −60.7 mV based on values of −59.09 ± 0.94 mV, n = 8; −58.85 ± 1.33 mV, n = 10; −64.27 ± 1.18 mV, n = 12; neurons from the apex, middle, and base, respectively; Liu et al., 2014) with similar values described previously (Lin and Chen, 2000; Marrs and Spirou, 2012), which would promote the inactivation of some potassium channels that ultimately define neuronal firing (Hille, 2001).

We first addressed this “unmasking” issue by assessing the population of cells that were generally least responsive to NT-3-induced changes in APmax, P14 neurons, by obtaining APmax values at both −80 and −60 mV holding potentials for each neuron. When the representative neuron shown in Figure 8A, which was exposed to NT-3, was held at −80 mV, it had an APmax of 2, but as the holding potential was gradually depolarized while maintaining the test current level, the SA phenotype was revealed. As shown in the plots of ISI versus APmax, we witnessed a reiteration of all three accommodation categories and a migration in the percentage of cells that exhibited SA when simply depolarized (Fig. 8B) to an even greater shift when depolarization was combined with NT-3 exposure (Fig. 8C). Indeed, the percentage of cells in each category in Figure 8C is very similar to that of P1–P2 neurons (cf. Fig. 4A, inset). For vehicle control basal and apical neurons, the effect of depolarization to −60 mV had a slight but significant effect on APmax (Fig. 8D, base: 1.8 ± 0.3 APs; Fig. 8E, apex: 2.1 ± 0.3 APs; p < 0.05). In agreement with our hypothesis, however, the effect of depolarization on neurons exposed to NT-3 was much more dramatic; resulting in an 8-fold increase for basal neurons (13.7 ± 3.4 APs vs base at −80 mV; p < 0.01; Fig. 8D) and a 5-fold increase for apical neurons (17.5 ± 3.5 APs vs apex at −80 mV; p < 0.01; Fig. 8E).

As shown in Figure 8, exposure to NT-3 and a 20 mV depolarization produced dramatic changes in APmax, and the specific APmax at −80 mV was an important predictor of APmax at −60 mV holding potential. Example sweeps (Fig. 9A) from P10 base and apex neurons treated with either vehicle or NT-3 highlight the effects observed in the group data (Fig. 9B–G). UA and RA neurons from both regions under vehicle control or NT-3 treatments were assessed for APmax at −80 mV, and then depolarized to −60 mV holding potential, where APmax was reassessed. The majority of vehicle control P10 basal and apical neurons remained UA or RA, but some neurons (four of 24 basal neurons and six of 22 apical neurons) converted to SA with the change in voltage (Fig. 9B,D). However, neurons exposed to NT-3 showed an even greater increase in APmax at −60 mV holding potential, with the majority of neurons (six of 11 basal neurons and nine of 12 apical neurons) shifted to SA (Fig. 9B,D). Therefore, the population of neurons that appeared to have a very limited response to NT-3 when held at −80 mV, in terms of APmax, now exhibited a completely different APmax when held at −60 mV. Notably, this effect was limited to RA neurons because SA neurons did not change significantly with the depolarization protocol (Fig. 9C,E). Figure 9F shows each recording in which APmax was obtained at both −80 and −60 mV holding potentials plotted against the voltage threshold that was obtained at −80 mV. Although not tested here, from previous experiments we predict that the voltage threshold at −60 mV would be ∼5 mV more depolarized (Liu et al., 2014). The gray circles are the APmax values at −80 mV and the black circles are the APmax values at −60 mV, which show the clear shift in APmax with the change in holding potential. The likelihood that a UA or RA cell at −80 mV would convert to SA is plotted in Figure 9G. Evidently, a neuron was far more likely to convert to SA at −60 mV if it had an APmax of at least 2. Further, the data in Figure 9F suggest that the voltage threshold may be a predictor of conversion to SA, because most of the SA neurons (black circles) emerged when voltage thresholds were −45 mV or lower.

We next expanded our analysis to include all of the experiments in which APmax was assessed at both holding potentials and were either UA or RA at −80 mV and then investigated whether the APmax at −80 mV was a predictor of converting to SA at −60 mV and if voltage threshold could predict the response to depolarization. Results presented in Figure 10A address the first issue and demonstrate that the likelihood of a UA or RA neuron converting to SA correlated strongly with APmax at −80 mV. Further, the effect of NT-3 can be seen in the data, with a higher percentage of both basal and apical neurons converting to SA with an original APmax of just 1. Moreover, in every condition, if a cell had an APmax of at least 2, then it was 50% more likely to become SA at −60 mV holding; for cells that fired 3–8 APs at −80 mV, this level increased to >65% for control groups and >85% for NT-3 groups.

To answer the second question, we performed two analyses. First, within the data in Figure 10A, we investigated whether there was an identifiable subcategory of RA neuron based on voltage threshold that would convert to SA. Indeed, those cells that converted to SA had a numerically slight but functionally meaningful reduction in voltage threshold compared with those cells that did not change accommodation category (converted from RA to SA: −48.7 ± 0.5 mV, n = 72; remained RA: −46.8 ± 0.7 mV, n = 28; p < 0.05). The second analysis was done on two very distinct populations—those cells that only fired one AP regardless of treatment condition, age, or voltage compared with those cells that fired a single AP at −80 mV but converted to SA at −60 mV (Fig. 10B). As the graph indicates, voltage threshold strongly predicts these two distinct categories of cells with the voltage threshold of UA neurons being significantly higher than those neurons that converted to SA (−40.9 ± 0.6 mV vs −49.7 ± 0.5 mV; p < 0.001). Interestingly, basal neurons largely comprise the UA only group (30 of 41 cells), whereas mostly apical neurons converted from UA to SA (12 of 18 cells), indicating a tonotopic tendency to these opposing responses.

These studies confirmed that voltage threshold is a strong predictor of whether a neuron will transform from RA to SA, but they do not address whether neurons also transform their inherent firing characteristics, such as ISIs, in concert with the change in accommodation, particularly in older mice. Shown in Figure 11A are voltage traces to depolarizing current steps from a P14 neuron that was held at −80 mV (left sweeps) and then −60 mV (right sweeps). The sweeps are aligned closely to the plateau potentials as shown by the values beside the horizontal dotted lines. This cell was RA when held at −80 mV, transformed to SA when held at −60 mV, and the effect was reversible (data not shown). Dramatic differences in the number of APs were observed for five different P10–P14 cells that transformed from RA to SA with the change in holding potential (Fig. 11B). As shown in the figure, cells that fired <5 APs at −80 mV now fired >20 APs, which indicates the potential dynamic coding capacity of these neurons. Importantly, the ISIs between the first two APs were essentially identical at each level, suggesting that, whereas APmax changed, the instantaneous timing did not (Fig. 11A, inset). This is shown for a larger dataset in Figure 11C, in which all cells with an APmax of 2 at −80 mV were plotted against their subsequent APmax at −60 mV. Remarkably, although the range of ISIs for the dataset is wide, the shift in holding potential does not alter the characteristic ISI of a given cell. Together, these data show that, despite large changes in APmax, the instantaneous rate remains static, reflecting a consistent parameter of the neuronal firing profile.

Discussion

Accommodation is a central feature of all sensory systems. Rapidly accommodating neurons are designed for the detection of time-dependent changes in input, whereas slowly accommodating neurons are more suited to encoding level and duration variations. Further, rather than being static carriers of information, sensory neurons can be plastic, as demonstrated in nociceptive (Woolf and Salter, 2000) and enteric (Mawe et al., 2009; Nurgali, 2009) neurons, giving rise to the notion that primary sensory afferents possess the ability to modify their coding capabilities. Within the single class of type I primary afferents in the auditory system, it would not be unexpected that different levels of accommodation and plasticity are present to encode the dynamic nature of acoustic stimuli while providing a neuronal substrate to process intensity and duration information.

We show in the present study that isolated spiral ganglion neurons can display distinct response modes based on accommodation and threshold, which are robust throughout development, neurotrophin exposure, and RMP level. At early postnatal ages, neurons were highly excitable and basal and apical neurons were equivalent across all timing and excitability features examined. Interestingly, during this early period, external factors such as membrane depolarization and NT-3 had little effect, indicating that spiral ganglion neurons were maximally excitable but minimally dynamic. By P14, however, this situation reversed. The neurons appeared superficially uniform, becoming faster, less excitable, and similar in terms of kinetics and APmax, although tonotopic differences in threshold persisted. However, at this later age, the plastic capabilities of the neurons increased such that they were highly responsive to RMP depolarization and NT-3 exposure, thus restoring the breadth of their response properties. Interestingly, application of NT-3 also reestablished tonotopic differences in latency and APmax. In these experiments, both basal and apical neurons received the same treatment; however, the concentration of NT-3 in vivo is graded and higher in the apex (Fritzsch et al., 1997; Fariñas et al., 2001; Sugawara et al., 2007), which may further enhance the tonotopic bias of these features.

Regulatory controls of accommodation response mode

The three response modes that we identified were defined by APmax and voltage threshold. Importantly, we found that the percentage of neurons within each category can shift while the framework remains stable. For example, RA neurons with low thresholds transitioned into SA neurons when their holding potentials were depolarized from a level at which most voltage-gated ion channels are not inactivated (−80 mV) to a level close to physiological resting potential (−60 mV; Liu et al., 2014). Although less prevalent, we also found UA neurons that could be converted to SA. Generally, the likelihood of transitioning to RA or SA was increased in cells with more hyperpolarized thresholds. Finally, we identified a subgroup of UA neuron that possessed the most depolarized thresholds and never changed response mode regardless of the treatment condition, indicating that these neurons may encode information that is distinct from those that do change response mode. Therefore, threshold is predictive of a neuron's accommodation profile and, further, this correlation is similar to that observed in vivo. Single-unit recordings from spiral ganglion neurons with high spontaneous rates generally display lower thresholds, whereas those with low spontaneous rates have higher thresholds (Liberman, 1982; Schmiedt, 1989; Taberner and Liberman, 2005).

The association of threshold with accommodation is important because it adds an additional parameter that further distinguishes our accommodation classifications indicating that these two parameters may be linked. A potential unifying substrate for this link is the Kv1 family of voltage-gated potassium channels because they are capable of controlling three key interrelated features, resting potential, threshold, and accommodation, in spiral ganglion neurons (Brew and Forsythe, 1995; Mo et al., 2002; Lopantsev et al., 2003; Chi and Nicol, 2007; Liu and Davis, 2007; Mathews et al., 2010; Hao et al., 2013). Interestingly, the increased expression of Kv1.1 during the first postnatal week corresponds closely to the changes in excitability over this same period. Although we focused here on Kv1.1 protein expression, we previously examined Kv1.2 channels, which have a similar expression profile as Kv1.1 (Liu et al., 2014). Further, the Kv1 family of channels are known to form heteromeric and homomeric complexes with differing properties (Ruppersberg et al., 1990; Hopkins et al., 1994), thus adding to the complexity of excitability available to spiral ganglion neurons. Hypothetically, however, a mechanism as simple as depolarization-induced Kv1 inactivation (Dodson et al., 2002) can have a profound effect on the transition to different accommodation classes that would essentially provide instantaneous, yet reversible, regulatory control. Conversely, neurotrophin exposure could activate intracellular signaling systems and engage gene transcription programs that would result in longer-lasting changes in ion channel composition. Beyond Kv1 channels, spiral ganglion neurons possess a wealth of channel types, including rapidly inactivating K+ channels (e.g., Kv3 or Kv4 families) that could be involved (Yamaguchi and Ohmori, 1990; Chen, 1997; Mo and Davis, 1997; Rosenblatt et al., 1997; Adamson et al., 2002b; Mo et al., 2002; Szabó et al., 2002; Hossain et al., 2005; Chen and Davis, 2006; Liu and Davis, 2007; Lv et al., 2012; Kim and Holt, 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014), but the characteristics of Kv1 channels (Johnston et al., 2010) are consistent with our observations.

Timing-related features and threshold are distinct and separately regulated

A distinguishing feature of the accommodation categories is the broadly dispersed and overlapping firing rates observed in both RA and SA neurons that range from 50 to >200 Hz. However, neurons that shifted from RA to SA manifested an increase in APmax, whereas intrinsic timing remained constant. Although the heterogeneity observed within the spiral ganglion may be rooted in differential distributions of ion channels, the source of regulatory control on a feature that remains constant is more difficult to pin down. Nevertheless, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are candidates for maintaining a stable firing rate due to their role in regulating both AP latency and duration (Chen et al., 2011). Although most voltage-gated ion channels evaluated in the spiral ganglion show tonotopic gradations and, therefore, are likely regulated by NT-3 and BDNF (Adamson et al., 2002a), one channel type, Cav2.2, stands out because it is distributed uniformly throughout the ganglion (Chen et al., 2011). Furthermore, because Cav2.2 channels are high-voltage activated, they may be less sensitive to differences in voltage threshold. Therefore, this ion channel and others with similar features would likely remain essentially unchanged with alterations in RMP and NT-3 and are potential candidates for maintaining the constant timing observed in the present study. Further studies are required to test this hypothesis directly.

The distinction between the timing-related features and accommodation and threshold was also evident when recordings were evaluated at different postnatal ages and in response to NT-3. For example, alterations in AP latency, a kinetic feature, arose substantially earlier (P2–P3) than the change in APmax (P4–P6) or voltage threshold (P4–P7). We also observed that the effects of NT-3 on AP latency and voltage threshold further differentiated these electrophysiological parameters. Therefore, neurons may establish their firing rate independently of membrane potential and voltage threshold, and the dissociation of these parameters at different developmental ages and with NT-3 application further supports the idea that distinct ion channel types regulate these electrophysiological features. This conclusion is also consistent with the tonotopic differences in AP latency (linear) and voltage threshold (non-monotonic) described previously (Liu and Davis, 2007).

Implications of the time course of regulation

The auditory system must encode rapidly changing acoustic stimuli, so it may not be surprising that rapid accommodation is predominant among the primary afferents to process this information. Conversely, we hypothesize that the presence of slowly accommodating neurons may contribute to coding stimulus intensity and waveform envelope duration. Although membrane potential changes are capable of instantaneously altering the accommodation response mode of a spiral ganglion neuron, it is the source of these changes that determines the time course of the effect. One might expect that voltage fluctuations due to voltage-gated ion channels, for example, would be essentially instantaneous. Conversely, should critical voltage changes be mediated through a channel type that requires second messenger signaling, such as HCN, an intermediate time course would be predicted. Finally, longer-term changes resulting from gene transcription could alter the balance of ion channels, as expected from exposure to neurotrophins (Ginty et al., 1994; Riccio et al., 1997; Sherwood et al., 1997; Woolf and Costigan, 1999). In such a highly modulated system in which neurotrophins, second messenger-modulated channels, calcium-activated potassium channels, and a profusion of efferent modulation exists (Dulon et al., 2006), one might hypothesize that these and other processes contribute to the plasticity and dynamic firing patterns that we observe. Although the source of each regulatory mechanism is necessarily speculative at this time, it is clear that the combined effects of many contributing factors highlight the intersection of different time scales with specific mechanisms allowing for dynamic changes to occur over multiple temporal domains.

Footnotes

The work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health (Grant RO1 DC01856). We thank Mark R. Plummer for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, Edmund Lee for contributing the data for endogenous RMP analysis, and Hui Zhong (Susan) Xue for expert technical support.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adamson CL, Reid MA, Davis RL. Opposite actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 on firing features and ion channel composition of murine spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2002a;22:1385–1396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01385.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson CL, Reid MA, Mo ZL, Bowne-English J, Davis RL. Firing features and potassium channel content of murine spiral ganglion neurons vary with cochlear location. J Comp Neurol. 2002b;447:331–350. doi: 10.1002/cne.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizley JK, Walker KM. Sensitivity and selectivity of neurons in auditory cortex to the pitch, timbre, and location of sounds. Neuroscientist. 2010;16:453–469. doi: 10.1177/1073858410371009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew HM, Forsythe ID. Two voltage-dependent K+ conductances with complementary functions in postsynaptic integration at a central auditory synapse. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8011–8022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08011.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton A, Accolla R, Simon SA. Coding in the mammalian gustatory system. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in primary auditory neurons. Hear Res. 1997;110:179–190. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(97)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WC, Davis RL. Voltage-gated and two-pore-domain potassium channels in murine spiral ganglion neurons. Hear Res. 2006;222:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WC, Xue HZ, Hsu YL, Liu Q, Patel S, Davis RL. Complex distribution patterns of voltage-gated calcium channel alpha-subunits in the spiral ganglion. Hear Res. 2011;278:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi XX, Nicol GD. Manipulation of the potassium channel Kv1.1 and its effect on neuronal excitability in rat sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2683–2692. doi: 10.1152/jn.00437.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland BG, Dubin MW, Levick WR. Sustained and transient neurones in the cat's retina and lateral geniculate nucleus. J Physiol. 1971;217:473–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson PD, Barker MC, Forsythe ID. Two heteromeric Kv1 potassium channels differentially regulate action potential firing. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6953–6961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06953.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling J. Information processing by local circuits: the vertebrate retina as a model system. In: Schmitt F, Worden F, editors. The neurosciences fourth study program. Cambridge, MA: MIT; 1979. pp. 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Jagger DJ, Lin X, Davis RL. Neuromodulation in the spiral ganglion: shaping signals from the organ of corti to the CNS. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fariñas I, Jones KR, Tessarollo L, Vigers AJ, Huang E, Kirstein M, de Caprona DC, Coppola V, Backus C, Reichardt LF, Fritzsch B. Spatial shaping of cochlear innervation by temporally regulated neurotrophin expression. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6170–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B, Fariñas I, Reichardt LF. Lack of neurotrophin 3 causes losses of both classes of spiral ganglion neurons in the cochlea in a region-specific fashion. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6213–6225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06213.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginty DD, Bonni A, Greenberg ME. Nerve growth factor activates a Ras-dependent protein kinase that stimulates c-fos transcription via phosphorylation of CREB. Cell. 1994;77:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Padilla F, Dandonneau M, Lavebratt C, Lesage F, Noël J, Delmas P. Kv1.1 channels act as mechanical brake in the senses of touch and pain. Neuron. 2013;77:899–914. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Ed 3. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WF, Allen ML, Houamed KM, Tempel BL. Properties of voltage-gated K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes by mKv1.1, mKv1.2 and their heteromultimers as revealed by mutagenesis of the dendrotoxin-binding site in mKv1.1. Pflugers Arch. 1994;428:382–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00724522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain WA, Antic SD, Yang Y, Rasband MN, Morest DK. Where is the spike generator of the cochlear nerve? Voltage-gated sodium channels in the mouse cochlea. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6857–6868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0123-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J, Forsythe ID, Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Going native: voltage-gated potassium channels controlling neuronal excitability. J Physiol. 2010;588:3187–3200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, McCormick DA. The functional influence of burst and tonic firing mode on synaptic interactions in the thalamus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9500–9516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09500.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Holt JR. Functional contributions of HCN channels in the primary auditory neurons of the mouse inner ear. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142:207–223. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC. Single-neuron labeling in the cat auditory nerve. Science. 1982;216:1239–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7079757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Chen S. Endogenously generated spontaneous spiking activities recorded from postnatal spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Davis RL. Regional specification of threshold sensitivity and response time in CBA/CaJ mouse spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2215–2222. doi: 10.1152/jn.00284.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lee E, Davis RL. Heterogeneous intrinsic excitability of murine spiral ganglion neurons is determined by Kv1 and HCN channels. Neuroscience. 2014;257:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein WR, Mendelson M. Components of receptor adaptation in a Pacinian corpuscle. J Physiol. 1965;177:377–397. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopantsev V, Tempel BL, Schwartzkroin PA. Hyperexcitability of CA3 pyramidal cells in mice lacking the potassium channel subunit Kv1.1. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1506–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.44602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv P, Sihn CR, Wang W, Shen H, Kim HJ, Rocha-Sanchez SM, Yamoah EN. Posthearing Ca(2+) currents and their roles in shaping the different modes of firing of spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16314–16330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2097-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Mantegazza M, Guatteo E, Wanke E. Action potentials recorded with patch-clamp amplifiers: are they genuine? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:530–534. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)40004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Mantegazza M, de Curtis M, Wanke E. Modalities of distortion of physiological voltage signals by patch-clamp amplifiers: a modeling study. Biophys J. 1998;74:831–842. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74007-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs GS, Spirou GA. Embryonic assembly of auditory circuits: spiral ganglion and brainstem. J Physiol. 2012;590:2391–2408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews PJ, Jercog PE, Rinzel J, Scott LL, Golding NL. Control of submillisecond synaptic timing in binaural coincidence detectors by K(v)1 channels. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:601–609. doi: 10.1038/nn.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawe GM, Strong DS, Sharkey KA. Plasticity of enteric nerve functions in the inflamed and postinflamed gut. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:481–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape HC. Properties of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurones. J Physiol. 1990;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, Frank T, Khimich D, Hoch G, Riedel D, Chapochnikov NM, Yarin YM, Harke B, Hell SW, Egner A, Moser T. Tuning of synapse number, structure and function in the cochlea. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:444–453. doi: 10.1038/nn.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaelian D, Ruben RJ. Development of hearing in the normal Cba-J mouse: correlation of physiological observations with behavioral responses and with cochlear anatomy. Acta Otolaryngologica. 1965;59:451–461. doi: 10.3109/00016486509124579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]