Abstract

Zoonotoc cutaneous leishmaniasis is endemic in several parts of Iran. Jahrom district is one of the most important endemic foci of leishmaniasis located in Fars province, southern Iran. To identify the vectors of leishmaniasis in this area, a total of 349 sandflies were collected during May to August 2009. They were caught from outdoors in five regions of Jahrom district including villages of Mousavieh, Ghotb-Abad, Heydar-Abad, Fath-Abad and Jahrom County. Eleven species of Phlebotomine (three Phlebotomus spp. and eight Sergentomyia spp.) were detected. To determine the sandflies naturally infected by Leishmania spp., 122 female sandflies were dissected and evaluated microscopically using Giemsa-stained slides. Natural infection of 2 out of 38 (5.26%) P. papatasi and 1 out of 8 (12.5%) P. salehi to Leishmania major was confirmed in the region. Sequencing and nested polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Leishmania were carried out to confirm the microscopic findings. Five (13.16%) P. papatasi and two (25%) P. salehi were positive in nested polymerase chain reaction assay. All positive samples were shown 72–76% similarity with L. major Friedlin. On the basis of our knowledge, this is the first molecular detection of L. major within naturally infected P. salehi in this region in southern Iran.

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) occurs in many parts of the world and is endemic in different parts of Iran (Nadim et al., 1977; Davami et al., 2010). CL is an increasing public health problem in 14 provinces of the country (Pourmohammadi et al., 2008; Razmjou et al., 2009). For the first time, CL was described in southern Iran by Nadim et al. (1977). In this area, the yearly incidence of CL has increased over the last decade (Motazedian et al., 2006). This rise may be due to the propagation of human populations into the habitats of the local vectors and the rodents as reservoir hosts (Dejeux, 2001). Leishmania major is the causative agent of wet lesions of CL and seen in rural areas of the world. In Iran, CL has been found in urban areas where the results of L. tropica infections have been observed (Ardehali et al., 2000). Phlebotomus species are the sole responsible for transmitting the disease in the old world (Azizi et al., 2008). The present study was conducted to determine the vector(s) of CL in Jahrom region in southern Iran.

SANDFLIES AND METHODS

Study Area

The Fars province is located in southern Iran and has an area of ∼122 400 km2. The climate is relatively dusty and dry. The study has been carried out in Jahrom focus of Fars province, southern Iran. This region is situated at ∼53°33′E, 28°30′N, and 1050 m above the sea level (Fars Budget and Planning Organization, 2000). Due to the suitable ecological conditions for leishmaniasis (reservoir hosts, vectors diversity and weather conditions), Jahrom has always been considered as one of the visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and CL focus regions (Fakhar et al., 2008; Davami et al., 2010), (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of Iran, showing the locations of Fars province and the city of Jahrom.

Collection and Examination of Sandflies

Between May and August 2009, sandflies were collected monthly by sticky paper traps (castor oil-coated white papers, 20×32 cm) from outdoor (rodent burrows, agricultural plantations surrounding the houses, near the houses, etc.) in five regions including Jahrom County and four villages of Mousavieh, Heydar-Abad, Ghotb-Abad and Fath-Abad. In each sampling, at least 30 sticky paper traps were set in the evening and collected in the next early morning.

The sandflies were dissected in a drop of sterile saline. Sandflies gut was checked for Leishmania promastigotes under a light microscope, at ×1000 (Mohebali et al., 2004). Then each of the smears was fixed in methanol and Giemsa-stained smear was prepared. To determine the species, sandflies were mounted in Puris Medium (Smart et al., 1965). The identification of the samples was based on specific taxonomic criteria (Theodor and Mesghali, 1964; Lewis, 1982).

DNA Extraction

Smears belonging to female P. papatasi and P. salehi were checked by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay for leishmania kDNA. Two to three smears (∼30 μl) were scraped from the slides and then added to 200 μl lysis buffer [1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.6, 1% v/v) Tween 20] containing 5 μl of a proteinase K solution that had 23 mg enzyme/ml (Motazedian et al., 2002). The specimens in micro-tubes were incubated for 2 hours at 56°C or 12 hours at 37°C before 50 μl of a phenol/chloroform/isoamyl-alcohol solution (25∶24∶1, by volume) was added. After being shaken vigorously, specimens were centrifuged at 12 000 rev/minute or 6000×g for 10 minutes. DNA in the supernatant solutions was precipitated with 200 μl of cold ethanol, resuspended in 50 μl deionized water [produced in a PurelabH UHQ system (Siemens Water Technologies, Warrendale, PA, USA)] and stored at 4°C (Motazedian et al., 2002) before use in the PCR-based assay.

PCR Assay

The nested PCR used to amplify the variable minicircle kDNA area of any Leishmania in the sandfly smears was a slight modification (Moemenbellah-Fard et al., 2003; Ghasemian et al., 2011). The first-round (external) primers were CSB1XR (ATTTTTCGCGATTTTCGCAGAACG) and CSB2XF (CGAGTAGCAGAAACTCCCGTTCA). A reaction mixture containing 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 200 μM of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 2.5 μl of 10X PCR buffer, 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase and 10 pmol of each primer was used in a total reaction volume of 25 μl including 5 μl of DNA sample. The second-round (internal) primers were 13Z (ACTGGGGGTTGGTGTAAAATAG) and LIR (TCGCAGAACGCCCCT). In this step, the mentioned reaction mixture was used in a total reaction volume of 30 μl containing 2 μl of DNA product of the first round. These mixtures were amplified in a programmable thermocycler (Mastercycler gradient; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) for 5 minutes at 94°C (1 cycle) followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 60 seconds and 72°C for 1.5 minutes followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 5 minutes. The WHO reference strains of L. tropica (MHOM/SU/71/K27), L. major (MHOM/SU/73/5ASKH) and L. infantum (MHOM/TN/80/IPT1) were used as standard DNA. A band of 560 bp indicated that L. major kDNA was present in the nested PCR-tested sandfly smear (Davami et al., 2010).

Electrophoresis

A 5-μl sample of the second-round product of PCR was subjected to electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by ultraviolet trans-illumination (Ghasemian et al., 2011).

Sequencing

The PCR bands of all positive samples were cut from the gel and purified by Gel Purification Kit (AccuPrep®, cat. no. k-3035-1; Bioneer, Alameda, CA, USA). The strands of amplified DNA were sequenced (both forward and reverse sequencing) with the PCR primers on an automated sequencer (377XL; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The nucleotide homologies of the sequenced products were studied with the TritrypDB blast programme. The determination of consensus sequences and informative motifs was performed by using FASTA-formatted sequences aligned with the Chromas programme.

RESULTS

In this study, among 349 collected sandflies, three species of Phlebotomus and eight species of Sergentomyia were determined. Phlebotomine consisted of Phlebotomus papatasi, P. salehi, P. sergenti, Sergentomyia sintoni, S. theodori, S. palestinensis, S. baghdadis, S. clydei, S. squamipleuris, S. tiberiadis and S. antennata (Table 1).

Table 1. The types and the numbers of sandflies collected in each of the five study regions in Jahrom focus, southern Iran.

| No. of sandflies collected in Jahrom focus | ||||||||||

| Mousavieh | Gotb-Abad | Heydar-Abad | Fath-Abad | Jahrom | ||||||

| Genus and species | ♀ and ♂ | ♀ and ♂ | ♀ and ♂ | ♀ and ♂ | ♀ and ♂ | |||||

| P.* (P.) papatasi | 9 | 48 | 4 | 33 | 19 | 36 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| P. (P.) salehi | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P. (Para.†) sergenti | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| S.‡ (S.) sintoni | 5 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| S. (S.) theodori | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (Parr.§) palestinensis | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (Parr.) baghdadis | 11 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (Sin.¶) clydei | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (Gr.**) squamipleuris | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (Sin.) tiberiadis | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. (S.) antennata | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 51 | 110 | 8 | 33 | 41 | 53 | 16 | 21 | 6 | 10 |

*Phlebotomus.

†Paraphlebotomus.

‡Sergentomyia.

§Parrotomyia.

¶Sintonius.

**Grassomyia.

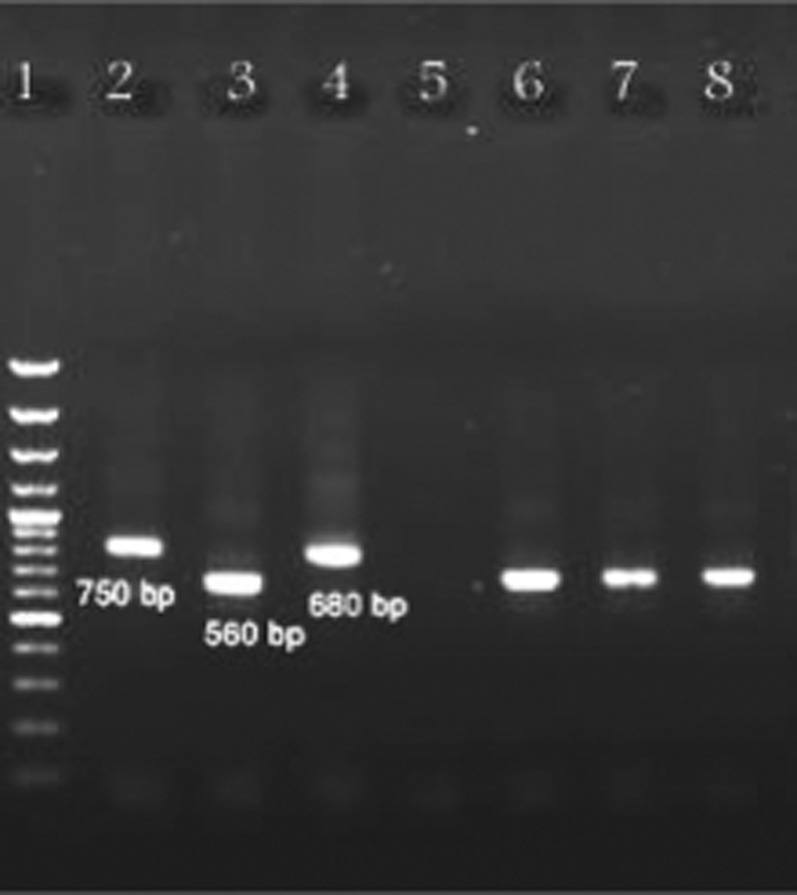

From the 122 female species, L. major was detected in species of P. papatasi and P. salehi. From 38 smears belonging to female of P. papatasi, 2 (5.26%) and 5 (13.6%) of them, and out of 8 species belong to P. salehi, 1 (12.5%) and 2 (25%) of them were positive by parasitology and PCR, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Gel electrophoresis results of nested PCR of Leishmania parasites isolated from sandflies using the primers CSB1XR, CSB2XF, 13Z and LIR; marker (100-bp ladder) (lane 1), reference strain of Leishmania major (560 bp) (lane 2), reference strain of L. tropica (750 bp) (lane 3), reference strain of L. infantum (680 bp) (lane 4), a male sandfly as negative control (lane 5), L. major isolated from Phlebotomus salehi in Heydar-Abad (lane 6), L. major isolated from P. papatasi in Heydar-Abad (lane 7) and L. major isolated from P. papatasi in Mousavieh (lane 8).

L. major was isolated and identified as the causative agent of CL from females of P. papatasi and P. salehi in Heydar-Abad, Mousavieh and Jahrom areas (Table 2). Seven specimens from female of P. sergenti checked for L. tropica, and also 69 specimens of female Sergentomyia spp. checked for Sauroleishmania spp., none of which were found infected.

Table 2. No. of sandflies infected with Leishmania major (L. major) in each of the five study regions in Jahrom focus, southern Iran.

| No. of sandflies infected with L. major in Jahrom focus | ||||||

| P. papatasi* | P. salehi | |||||

| Regions | ♀ | Parasitology pos. | PCR pos. | ♀ | Parasitology pos. | PCR pos. |

| Mousavieh | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ghotb-Abad | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heydar-Abad | 19 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Fath-Abad | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jahrom | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total no. (%) | 38 | 2 (5.26%) | 5 (13.6%) | 8 | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25%) |

*Phlebotomus.

Regarding species identification by using TritrypDB sequence analysis against Trypanosomatidae species, the target sequence of PCR amplifications was shown 72–76% similarity with L. major Friedlin (Leishmania sequence available in the GeneBank).

DISCUSSION

The Fars province is rich in Sandflies fauna because of its high bio-ecological diversity. P. major, P. Keshishiani, P. alexandri and P. papatasi sandflies are reported as the vector(s) of VL and CL in this focus, respectively (Sahabi et al., 1992; Seyedi Rashti et al., 1995; Azizi et al., 2006; Azizi et al., 2008; Azizi et al., 2009). In this region, leishmania transmits to humans by the bite of infected sandfly. P. papatasi and P. salehi are the vectors and wild rodents and dogs serve as the reservoir of infection. The determination of leishmania vectors and their biology is necessary for planning Leishmanial-controlling strategies (Killick-Kendrick, 1999). Molecular-based methods using PCR are well-organized and reliable tools for the detection of Leishmania spp. They are more sensitive and specific than microscopic dissection (Aransay et al., 2000). Although molecular assays such as PCR methods and sequencing have several advantages (high sensitivity and specificity, usable in ethanol-fixed sandflies, checking up many samples in a short period of time and low effort, etc.) and drawbacks (complicated and expensive technique), when they associated with morphological characterization of the sandflies, they will be a powerful epidemiological tool for the determination of the number of sandflies infected with Leishmania spp. in nature (Maia et al., 2009).

In this study, natural infection of P. papatasi and P. salehi by L. major was confirmed by both microscopic and PCR techniques. L. major is the causative agent of CL in Jahrom district, southern Iran (Davami et al., 2010). Le Blancq et al. (1986) isolated L. major in India from P. papatasi and P. salehi. In Fars province, southern Iran, P. papatasi has been reported as the vector of L. major (Rassi et al., 2007; Azizi et al., 2010). P. salehi was described from a single male specimen caught in Yekdar village in Jask district of southern Iran in 1965 for the first time (Mesghali and Rashti, 1968). The main distribution area of this species is from India to Iran (Mesghali and Rashti, 1968). In 1967–1968, natural infection of P. salehi to L. major was reported in Sistan-Baluchestan province in southeast of Iran (Mesghali and Rashti, 1968). The first report of natural leptomonad infection of P. salehi refers to Kasiri and Javadian in Sistan-Baluchestan province from southeast of Iran. Totally, they dissected 667 of P. papatasi and 465 of P. salehi, of which 2.1 and 1.07% of them were found to be infected with promastigote, respectively. Based on the observation of lesions caused after inoculation of promastigotes to the basis of tail or foot pads of Balb/C mice, L. major was characterized as the causative agent of CL (Kasiri and Javadian, 2000).

In this study, based on (1) the observation of promastigotes in dissected sandflies; (2) the use of a high sensitive and specific nested PCR designed for kDNA of Leishmania; and (3) the comparison of the kDNA of sequenced products with GeneBank that confirmed the highest homology of >75% with L. major, it is concluded that the species is L. major.

On the basis of our findings, this is the first molecular detection of L. major within naturally infected P. salehi in this region of Fars province, southern Iran.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS. The authors would like to thank the Office of Vice-Chancellors for Research of Jahrom and Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for financial support of this project.

REFERENCES

- Aransay AM, Scoulica E, Tselentis Y.(2000)Detection and identification of Leishmania DNA within naturally infected sandflies by semi nested PCR on minicircle kinetoplastic DNA. Applied and environmental microbiology 661933–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardehali S, Moattari A, Hatam GR, Hosseini SM, Sharifi I.(2000)Characterization of Leishmania isolated in Iran. 1. Serotyping with species specific monoclonal antibodies. Acta Tropica 31301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Motazedian MH, Asgari Q, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR.(2008)First detection of Leishmania infantum in Phlebotomus (Larroussius) major (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Iran. Journal of Medical Entomology 45726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Motazedian MH, Rafizadeh S, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Mohebali M.(2006)Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) alexandri: a probable vector of Leishmania infantum in Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 10063–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Jalali M, Kalantari M.(2009)The fauna and bioecology of vectors of Leishmaniasis (Phlebotominae sandflies) in Nourabad Mamassani County, Fars Province. Journal of Armaghane-danesh 13102–110.(Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Moemenbellah-Fard MD.(2010)PCR-based detection of Leishmania major kDNA within naturally infected Phlebotomus papatasi in Southern Iran. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104440–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davami MH, Motazedian MH, Sarkari B.(2010)The changing profile of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a focus of the disease in Jahrom district, Southern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 104377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejeux P.(2001)The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 95239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhar M, Motazedian MH, Hatam GR, Asgari Q, Kalantari M, Mohebali M.(2008)Asymptomatic human carriers of Leishmania infantum possible reservoirs for Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis in Southern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 102577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fars Budget, Planning Organization(2000)Position of Fars province: annual report. Management and Planning Press 20–30.(In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemian M, Maraghi S, Samarbafzadeh AR, Jelowdar A, Kalantari M.(2011)The PCR-based detection and identification of the parasites causing human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Iranian city of Ahvaz. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 105209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasiri H, Javadian E.(2000)The natural leptomonad infection of Phlebotomus papatasi and Phlebotomus salehi in endemic foci of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sistan and Bluchestan province (Southeast of Iran). Iranian Journal of Public Health 2915–20. [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R.(1999)The biology and control of phlebotomine sandflies. Clinics in Dermatology 17279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blancq SM, Schnur LF, Peters W.(1986)Leishmania in the old world: the geographical and hostal distribution of L. major zymodemes. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 8099–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DJ.(1982)A taxonomic review of the genus Phlebotomus (Diptera: Psychodidae). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) (Entomology) 45121–209. [Google Scholar]

- Maia C, Afonso MO, Neto L, Dionísio L, Campino L.(2009)Molecular detection of Leishmania infantum in naturally infected Phlebotomus perniciosus from Algarve Region, Portugal. Journal of Vector Borne Disease 46268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesghali A, Rashti MA.(1968)Phlebotominae (Diptera) of Iran. IV. More information about Phlebotomus (Phlebotomus) salehi Mesghali, 1965. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique 61768–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moemenbellah-Fard MD, Kalantari M, Rassi Y, Javadian E.(2003)The PCR-based detection of Leishmania major infections in Meriones libycus (Rodentia: Muridae) from Southern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 97811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Javadian E, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA, Hajjran H, Abaei MR.(2004)Characterization of Leishmania infection in rodents from endemic areas of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 10415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motazedian H, Karamian M, Noyes HA, Ardehali S.(2002)DNA extraction and amplification of Leishmania from archived, Giemsa-stained slides, for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis by PCR. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 9631–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motazedian MH, Mehrabani D, Oryan A, Asgari Q, Karamian M, Kalantari M.(2006)Life cycle of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Larestan, Southern Iran. Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine Research Center 1137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A, Tahvildare-Bidruni GH.(1977)Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran: B. Khorassan, part VI: cutaneous leishmaniasis in Neishabur, Iran. Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique 70171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmohammadi B, Motazedian MH, Kalantari M. Rodent infection with Leishmania in a new focus of human cutaneous leishmaniasis, in northern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2008;102:127–133. doi: 10.1179/136485908X252223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi Y, Gassemi MM, Javadian E, Rafizadeh S, Motazedian H, Vatandoost H.(2007).Vectors and reservoirs of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Marvdasht district, Southern Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 13686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razmjou Sh, Hejazy H, Motazedian MH, Baghaei M, Emamy M, Kalantary M.(2009)A new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Shiraz, Iran. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahabi Z, Seyyedi Rashti MA, Nadim A, Javadian E, Kazemeini M, Abai MR.(1992)A preliminary report on the natural leptomonad infection of Phlebotomus major in an endemic focus of V.L. in Fars Province, south of Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2187–93. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedi Rashti MA, Sahabi Z, Notash KananiA.(1995)Phlebotomus (Larroussius) Keshishiani hchurenkova1936, Another vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2425–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smart J, Jordan K, Whittick RJ.(1965)Insects of Medical Importance Oxfords: Adlen Press; 286–288. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor O, Mesghali A.(1964)On the phlebotominae of Iran. Journal of Medical Entomology 1285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]