Abstract

Objective:

Knowledge and attitude regarding electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the important parameters for acceptance of ECT as a safe and effective treatment option. Several factors shape the knowledge and attitude of general people such as previous experience of ECT, sources of their information about ECT and prevailing myths about ECT. The present study attempted to examine the knowledge and attitude concerning ECT among patients with psychiatric disorders and their relatives.

Materials and Methods:

Knowledge and attitudes regarding ECT were assessed using the Bengali version of the ECT knowledge and attitude questionnaires, between 100 clinically stable patients with mental illnesses and their healthy relatives.

Results:

Majority of the patients and relatives were unaware of the basic facts about ECT. Relatives were somewhat better informed and more positive about ECT than patients, but the differences between the two groups were not significant. Previous experience of ECT did not have any major impact in knowledge and attitude in both patients and relative groups. Patients obtained information, mostly from media (44%), doctors (23%), and from personal experiences (13%). On the other hand, relatives obtained information almost equally from media (26%), doctors (27%), and experience of friends or relatives (28%). No significant difference was observed in knowledge and attitude in patients who had obtained their facts from doctors (n=23) and from other sources (n=77). Among relatives, those who had obtained their information from doctors (n=27) were better informed than those who had obtained so from other sources (n=73).

Conclusions:

Since patients and relatives have poor knowledge and negative attitude toward ECT, medical professionals should impart proper information about ECT to patients and relatives to increase the acceptability of this treatment.

Keywords: Attitude, electroconvulsive therapy, knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the oldest treatments in psychiatry, which has survived the test of time. Despite controversies surrounding its use it still remains one of the most efficacious treatments for many severe mental disorders.[1,2,3] However, lot of stigma is attached to the use of ECT, which undermines the acceptance of this treatment by the general public.[4,5] In contrast to the negative view about ECT among the general public, studies which have evaluated the knowledge and attitude of mentally ill patients who have received ECT and their relatives, suggest that they are mostly satisfied with the experience if ECT.[6,7,8] Studies which have evaluated the attitude of patients and relatives before and after ECT also show that attitudes become more positive following the experience of the treatment.[9,10,11] Even relatives who have been a part of the process of ECT administration are usually better informed and have more positive attitude toward ECT, than those who have never had such experience of ECT.[12,13]

Fewer studies have evaluated the knowledge and attitude concerning ECT among mentally ill patients who have not received ECT and their relatives.[14,15] This is an important group not only because they might be potential candidates for ECT, but they may also influence perceptions of other patients regarding ECT. India is a vast country with varying treatment standards with respect to ECT. Recently, there has been a lot of concern about the indiscriminate use of ECT in India.[16] More studies on the knowledge and attitude of patients and relatives can inform this debate about the practice of ECT. Hence, the present study attempted to examine the knowledge and attitude concerning ECT among patients with psychiatric disorders and their relatives from Burdwan Medical College, Burdwan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the institute where it was conducted. All the participants were recruited after obtaining proper written informed consent.

Participants

This study involved 100 patients (aged more than 18 years) with mental illnesses and their relatives attending the Department of Psychiatry of a teaching and tertiary-care hospital in Burdhwan. The patients included in the study were clinically stable at the time of assessment. The relatives of the patients were aged more than 18 years, were free from any major physical or psychiatric illnesses, were staying with the patients and were actively involved in their treatment.

Assessments

In their landmark study, Freeman and Kendell[17] developed a series of questionnaires to assess knowledge and attitudes toward ECT among patients who had received ECT. These were modified by Tang et al.[18] and subsequently used in other studies. Following a pilot study, English and Hindi versions of these questionnaires were adapted for use among Indian patients and their relatives, and applied to group of patients who had received ECT.[19] Versions of the same questionnaires were simultaneously validated among a large population of relatives from the same center.[14] The current study employed a Bengali version of these questionnaires. For this purpose, the English version of the questionnaire was translated and back translated using the World Health Organization methodology[20] by bilingual experts.

Data analysis

Being largely a descriptive study, only a bare minimum analysis of the data (using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 14) was done. Descriptive statistics consisted of frequency counts, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Chi-square tests were used for comparisons.

RESULTS

Profile of patients and relatives

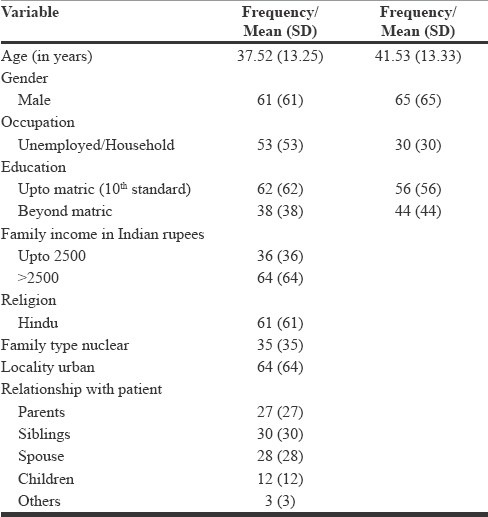

The study included 100 patients and their relatives. The socio demographic profile of the patients and relatives is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of patients and the caregivers

Clinical profile

Among the patients included in the study, 30 were suffering from a psychotic disorder, 19 from bipolar disorder, 33 from depressive disorders, 8 from obsessive compulsive disorder, and 10 were suffering from “other mental disorders due to brain damage and dysfunction and to physical disease.” Of the 100 patients included, only 13 had received ECT in the past.

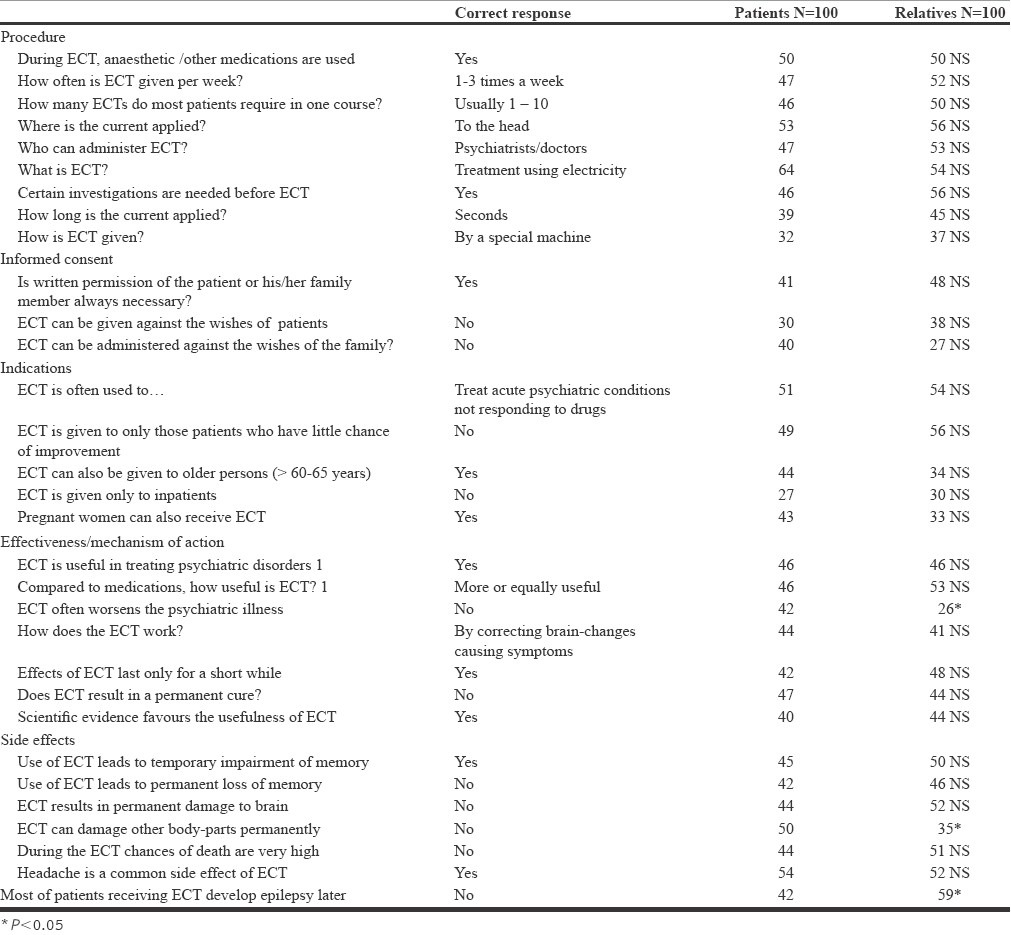

Knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy among patients and relatives

Knowledge about ECT was assessed using a 31-item questionnaire. Each item had three responses: A correct, an incorrect, and a “don’t know” response. Incorrect and “don’t know” responses on any question were combined while analyzing the data, because both signified that the participants were unaware about ECT [Table 2].

Table 2.

Knowledge of ECT among patients and relatives

None of the patient and relative had full knowledge about different aspects of ECT. Majority of the patients and relatives were unaware of the basic facts about the procedure of ECT, informed consent, indications, effectiveness, and side effects. Overall on most of the questions relatives’ had better knowledge than the patients. However, the differences between the two groups were non-significant. Surprisingly, compared to patients, significantly more relatives believed that “ECT can worsen the psychiatric illness for which it is used” and “ECT can damage body parts other than brain.” However, compared to patients, significantly less number of relatives believed that “those who receive ECT later develop epilepsy.” There was no difference in the knowledge of patients who have received ECT in the past (n=13) and those who had not received ECT (n=87), except that those who had received ECT had significantly better knowledge on the item of “ECT is generally useful in the conditions for which it is used” (Chi-square value with Yates correction 4.41; P=0.03), whereas those who had not received ECT had better knowledge with respect to use of ECT in various setups (i.e. ECT can be given to both inpatients and outpatients) (Chi-square value with Yates correction 4.06; P=0.04). Moreover, there was no difference in the knowledge of the relatives whose patient had received ECT in the past and whose patients had never received ECT.

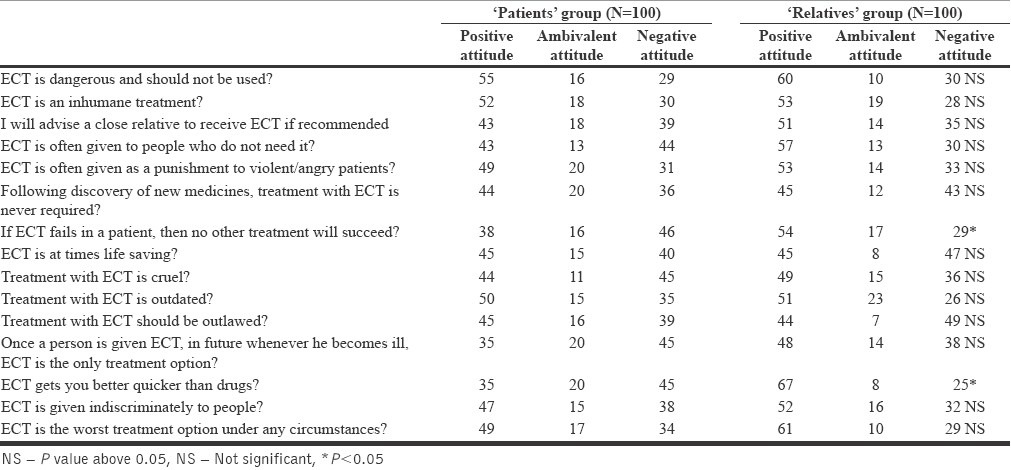

Attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy among relatives

Attitudes toward ECT were assessed using a 15-item questionnaire. Each item had three alternatives based on which responses were categorized into positive, negative, or ambivalent attitudes [Table 3].

Table 3.

Attitudes towards ECT among patients and relatives

Positive attitudes toward ECT were found in slightly less than half of the patients (45%). Positive attitudes were somewhat more common among relatives (53%), but not significantly so for most items. Negative attitudes were quite common among the participants, including patients 29-45%, average 38%) as well as relatives (25-45%, average 33%). Only a few patients (11-20%) and relatives (8-23%) were uncertain about their attitudes to ECT. There was no significant difference between the patients and relatives on different aspects of attitude toward ECT, except that significantly higher percentage of relatives had positive attitude with regard to that “ECT gets a person better quicker than drugs” and a smaller proportion of relatives had negative attitude on the item: “If ECT fails in a patient, then no other treatment will succeed.” There was no difference in attitude of those patients who had received ECT in the past and those who had not received ECT. The same was true for the relatives of patients who had received ECT in the past and those who had not received ECT.

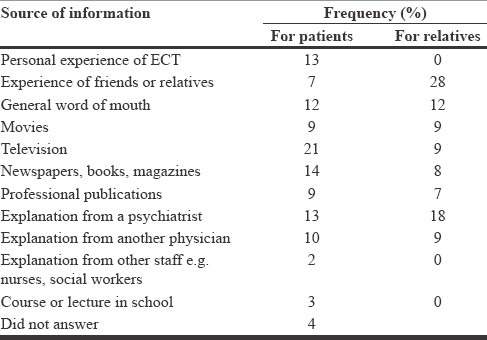

Source of information about electroconvulsive therapy

Patient and relatives were also asked about the sources from which they had derived their information about ECT. The primary source of information in about two-fifth of the patients was media (movies, television, newspapers, books, magazines) and one-fifth of them had obtained the information from a psychiatrist or physician. On the other hand, one-fourth of the relatives had the information from media, psychiatrist or physician or from the experience of a relative or a friend [Table 4].

Table 4.

Primary Source of information regarding ECT obtained by patients and their relatives

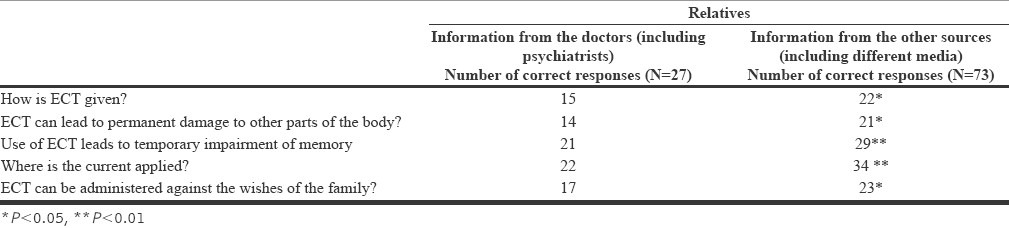

Comparison of knowledge and attitude of patients who had obtained their facts from doctors (n=23) and from other sources (n=77) did not reveal any significant difference. With regard to knowledge of relatives, comparison of those who had obtained their facts from doctors (n=27) and from other sources (n=73) revealed significant differences between the two groups on 5 of the 31 items [Table 5] relating to knowledge of ECT, with all favoring those who had obtained their information from doctors. However, there was no difference in attitude toward ECT between the two groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of knowledge between caregivers who had obtained their information from the doctors (including psychiatrists) and other sources (including media)

DISCUSSION

This study examined the knowledge and attitudes of patients with mental illnesses and their relatives towards ECT. Compared to most of the previous studies, which have evaluated these aspects in patients who have received ECT, the present study predominantly included patients who had never received ECT and their relatives.

Although the awareness about ECT in this population of patients and relatives who had no experience of ECT was similar to those who had been exposed to the treatment, their attitudes to ECT were markedly different.

The majority of the patients and relatives of the present study were unaware of the basic facts about the procedure of ECT, informed consent, indications, effectiveness and side effects. The poor knowledge about ECT among patients observed in the present study was no different from studies of patients who have actually undergone ECT.[11,13,15,17,18,19] Such studies from developing countries suggest that less than a-quarter of patients (0-23%) have complete or near-complete knowledge and understanding of the procedure of ECT.[19,21,22,23] Patients are usually not aware of the various intricate aspects of ECT (e.g. different indications, techniques, adverse effects, mechanism, etc.). Studies from the West have also found that most of the patients have poor knowledge about various aspects of ECT.[11,12,13,17,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] In patients and relatives with no experience of ECT this unawareness is probably a result of lack of access to proper sources of information. The fact that a majority of the participants of the current study obtained their information from the media indicates that this was the most likely cause for their unawareness regarding ECT. Moreover, among relatives those who had obtained their information from doctors were more knowledgeable about ECT.

In the present study, there was no significant difference between the knowledge of patients and the relatives. Only few studies, mainly from developing countries have evaluated the knowledge and attitude toward ECT of relatives of patients with mental disorders. Most of these studies suggest that relatives are better informed.[5] However, most of these studies have evaluated relatives of patient who have received ECT. Awareness of ECT is generally poor among relatives of patients who have not received ECT.[14,15] The lack of differences between patients and relatives could also be due to the small number of patients of this study who had received ECT in the past.

The results also clearly showed that this group of patients, most of whom had never received treatment with ECT, only about half of the participants viewed ECT positively, while a very high proportion had negative perceptions of ECT. Other studies, which have assessed attitudes among patients and relatives with no experience of ECT, have come to similar conclusions.[14,15] These findings are in marked contrast to those obtained among patients and relatives who have had some experience of the treatment. Such patients, and particularly their relatives, usually have very positive attitudes toward ECT.[14,19,5]

Taken together the results of the present study suggest that when patients and relatives have no experience of ECT they are more likely to derive their knowledge and attitudes about ECT from sources such as the media and not doctors who administer ECT. This not only leads to unawareness about ECT, but also engenders negative attitudes about the treatment. Attitudes toward ECT are more likely to be favorable when shaped by personal experience and information obtained from doctors, rather than media portrayals of the treatment. Accordingly, educating patients with psychiatric disorders and their relatives about ECT is a responsibility that mental health professionals need to take more seriously.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fink M. ECT has much to offer our patients: It should not be ignored. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2:1–8. doi: 10.3109/15622970109039978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowman J, Patel A, Rajput K. Electroconvulsive therapy: Attitudes and misconceptions. J ECT. 2005;21:84–7. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000161043.00911.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer M, Bschor T, Pfennig A, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders in primary care. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:67–104. doi: 10.1080/15622970701227829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarti S, Grover S, Rajagopal R. Electroconvulsive therapy: A review of knowledge, experience and attitudes of patients concerning the treatment. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:525–37. doi: 10.3109/15622970903559925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti S, Grover S, Rajagopal R. Perceptions and awareness of electroconvulsive therapy among patients and their families: A review of the research from developing countries. J ECT. 2010;26:317–22. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e3181cfc8ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodaty H, Berle D, Hickie I, Mason C. Perceptions of outcome from electroconvulsive therapy by depressed patients and psychiatrists. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:196–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowman J, Patel A, Rajput K. Electroconvulsive therapy: Attitudes and misconceptions. J ECT. 2005;21:84–7. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000161043.00911.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman JA, Krahn LE, Smith GE, Rummans TA, Pileggi TS. Patient satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:967–71. doi: 10.4065/74.10.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apéria B. Hormone pattern and post-treatment attitudes in patients with major depressive disorder given electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:271–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calev A, Kochav-Lev E, Tubi N, Nigal D, Chazan S, Shapira B, et al. Change in attitude toward electroconvulsive therapy: Effects of treatment, time since treatment, and severity of depression. Convuls Ther. 1991;7:184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malekian A, Amini Z, Maracy MR, Barekatain M. Knowledge of attitude toward experience and satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy in a sample of Iranian patients. J ECT. 2009;25:106–12. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31818050dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr RA, McGrath JJ, O’Kearney RT, Price J. ECT: Misconceptions and attitudes. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1982;16:43–9. doi: 10.3109/00048678209159469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustin J, Rapoport MJ, Krishna M, Matusevich D, Finkelsztein C, Strejilevich S, et al. Are patients’ attitudes towards and knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy transcultural. A multi-national pilot study? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:497–503. doi: 10.1002/gps.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grover SK, Chakrabarti S, Khehra N, Rajagopal R. Does the experience of electroconvulsive therapy improve awareness and perceptions of treatment among relatives of patients? J ECT. 2011;27:67–72. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181d773eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavan BS, Kumar S, Arun P, Bala C, Singh T. ECT: Knowledge and attitude among patients and their relatives. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:34–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathare S. Beyond ECT: Priorities in mental health care in India. Issues Med Ethics. 2003;11:11–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman CP, Kendell RE. ECT: I. Patients’ experiences and attitudes. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:8–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang WK, Ungvari GS, Chan GW. Patients’ and their relatives’ knowledge of, experience with, attitude toward, and satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy in Hong Kong, China. J ECT. 2002;18:207–12. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopal R, Chakrabarti S, Grover S, Khehra N. Knowledge, experience and attitudes concerning electroconvulsive therapy among patients and their relatives. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:201–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organisation. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 21.Arshad M, Arham AZ, Arif M, Bano M, Bashir A, Bokutz M, et al. Awareness and perceptions of electroconvulsive therapy among psychiatric patients: A cross-sectional survey from teaching hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramachandra, Gangadhar BN, Lalitha N, Janakiramaiah N, Shivananda BL. Patients's knowledge about ECT. NIMHANS J. 1992;10:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajkumar AP, Saravanan B, Jacob KS. Perspectives of patients and relatives about electroconvulsive therapy: A qualitative study from Vellore, India. J ECT. 2006;22:253–8. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000244237.79672.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes J, Barraclough BM, Reeve W. Are patients shocked by ECT? J R Soc Med. 1981;74:283–5. doi: 10.1177/014107688107400409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riordan DM, Barron P, Bowden MF. ECT: A patient-friendly procedure? Psychiatr Bull. 1993;17:531–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenaway A. Educating patients and relatives about electroconvulsive therapy: The use of an information leaflet. Psychiatr Bull. 1993;17:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westreich L, Levine S, Ginsburg P, Wilets I. Patient knowledge about electroconvulsive therapy: Effect of an informational video. Convuls Ther. 1995;11:32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greening J, Bentham P, Stemmon J, Staples V, Ambegaokar S, Upthegrove R, et al. The effect of structured consent on recall of information pre- and post-ECT. Psychiatr Bull. 1999;23:471–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taieb O, Flament MF, Corcos M, Jeammet P, Basquin M, Mazet P, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents with mood disorder: Patients’ and parents’ attitudes. Psychiatry Res. 2001;104:183–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malcolm K. Patient's perceptions and knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Bull. 1989;13:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benbow SM, Crentsil J. Subjective experience of electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Bull. 2004;28:289–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter G, Koster K, Rey JM. Electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents: Experience, knowledge, and attitudes of recipients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:594–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199905000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]