Abstract

Importance

Youth in poor neighborhoods have high emotional problem rates. Understanding neighborhood influences on these rates is crucial for designing neighborhood-level interventions.

Objective

To do exploratory analysis of associations between housing mobility interventions for children in high-poverty neighborhoods and subsequent mental disorders during adolescence.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration in 1994-1998 randomized 4,604 volunteer public housing families with children in high-poverty neighborhoods into Low-poverty voucher (LPV) or Traditional voucher (TRV) interventions to encourage moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods or a Control group. An evaluation 10-15 years later (June 2008-April 2010)interviewed (blinded to assignment) participants aged 0-8 at randomization and 13-19 at follow-up. Response rates were 86.9-92.9%.

Interventions

LPV (n=1,430) received vouchers to move to low-poverty neighborhoods with enhanced mobility counseling. TRV (n=1,081) received geographically unrestricted vouchers. Controls (n=1,178) received no intervention.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Twelve-month DSM-IV major depressive, panic, post-traumatic stress (PTSD), oppositional-defiant, intermittent explosive, and conduct disorders assessed post hoc with a validated research diagnostic interview.

Results

3,689 children were randomized and 2,872 interviewed (1,407 boys, median age 16 range: 13-19; 1,465 girls, median age 16, range 13-19). Boys had significantly elevated rates of major depression in LPV (7.1% [95% CI, 4.1-10.1%]; OR, 2.2 [95% CI, 1.2-3.9]) versus Controls (3.5% [95% CI, 2.3-4.6%]), PTSD in LPV (6.2% [95% CI, 4.7-7.7%]; OR, 3.4 [95% CI, 1.6-7.4]) and TRV (4.9% [95% CI, 3.0-6.8%]; OR, 2.7 [95% CI, 1.2-5.8]) versus Controls (1.9% [95% CI, 0.9-2.9%]), and conduct disorder in LPV (6.4% [95% CI, 4.7-8.1%];OR, 3.1[95% CI, 1.7-5.8]) versus Controls (2.1% [95% CI, 1.1-3.2%]). TRV girls had reduced rates of major depression (6.5% [95% CI, 4.5-8.4%]; OR, 0.6 [95% CI, 0.3-0.9 ]) versus Controls (10.9% [95% CI, 8.4-13.4%]) and conduct disorder (0.3% [95% CI, 0.0-0.7%]; OR, 0.1 [95% CI, 0.0-0.4]) versus Controls (2.9% [95% CI, 1.1-4.7%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Interventions to encourage moving from high-poverty neighborhoods were associated with elevated depression, PTSD, and conduct disorder among boys and reduced depression and conduct disorder among girls. Better understanding of interactions among individual, family, and neighborhood risk factors is needed to guide future public housing policy changes.

Observational studies consistently find youth in poor neighborhoods have high rates of emotional problems even after controlling individual-level risk factors,1 raising the possibilities that neighborhood characteristics affect emotional functioning2 and that neighborhood-level interventions might reduce these problems. Available data are unclear on these possibilities, though, because observational studies are subject to selection bias (i.e., families with emotional problems selecting into poorer neighborhoods). Despite this uncertainty, available data have been presumptively characterized as documenting neighborhood effects,3 causal pathways have been hypothesized,4 and interventions have been implemented.5

It is important to evaluate causal claims regarding neighborhood effects experimentally. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) attempted to do this in a housing-mobility experiment known as the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration (MTO) in 1994-1998 by randomizing volunteer low-income public housing families with children to receive vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods.6,7 An interim evaluation 4-7 years after randomization showed that the intervention caused families to move to better neighborhoods (e.g., lower poverty and crime rates, social ties with more affluent people).8 Significant reductions in psychological distress and depression were also found among intervention versus control adolescent girls but increased behavior problems were found among intervention versus control adolescent boys.9-11 Given the importance of these sex differences, clinically significant mental disorders were included in a long-term (10-15 years after randomization) evaluation survey. We present here the first data regarding associations of MTO randomization with these disorders among adolescents. Prior long-term evaluation reports documented effects on improved neighborhood characteristics,12,13 reduced adult extreme obesity and diabetes,14 and improved adult subjective well-being.13 The long-term evaluation found significantly reduced psychological distress among female youth,15 but measures of mental disorders were not examined in previous reports. The intervention had no detectable effects on economic self-sufficiency.13

Methods

Objectives

The primary MTO objectives were to move families to lower-poverty neighborhoods and increase educational achievement and economic self-sufficiency. Mental disorders were post hoc outcomes. The current report presents exploratory analyses evaluating long-term associations of intervention randomization with 12-month mental disorders among participants who were in early childhood (ages 0-8) at randomization and adolescence (ages 13-19) at long-term follow-up (June 2008-April 2010).

Study Design

MTO families (n= 4,604) were recruited by public housing authorities in 1994-1998 for a randomized rent-subsidy voucher lottery.16 Volunteer families were assigned an identification number and randomized using a computerized random-number generator. Families had to reside in public or project-based assisted housing in high-poverty census tracts (>40% families in poverty) in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, or New York; be eligible for Section 8 housing; and have 1+ children age <18. Housing authorities sent recruitment letters, held information sessions, and asked families to complete pre-applications within a short recruitment time window (within 4 weeks of invitation). Signed consents and baseline questionnaires were obtained in intake sessions prior to randomization. Families were then randomized into 1 of 3 groups. In the Low-poverty voucher group, families were offered a standard rent-subsidy voucher but with the restriction on use to low-poverty census tracts (<10% residents poor in 1990). Census tracts contain 2,500-8,000 people and are defined by the Census Bureau to be “homogeneous with respect to population characteristics, economic status, and living conditions.”17 Vouchers provided subsidies for private-market housing equal to the difference between a rent threshold and the family's rent contribution (30% of income, identical to public housing).18Families remained eligible for vouchers so long as they met income and other criteria. Families also received short-term housing counseling for their initial housing search.6,7 After 1 year, families in the Low-poverty voucher intervention group could use their voucher to relocate to a different tract, including those with higher poverty rates, or could remain in the tract where they originally moved even if the poverty rate of that tract fell out of the “low-poverty” range. In the Traditional voucher group, families were offered a standard rent-subsidy voucher without restriction on location and standard mobility counseling.6,7 In the Control group, families were offered no new assistance. Enhanced mobility counseling was offered to Low-poverty voucher group families because of restrictions on where they could move. The protocol was approved by the Office of Management and Budget and HUD. Twenty-three percent of invited families applied.6 Forty-eight percent of Low-poverty and 63% of Traditional voucher group families used their vouchers to move.7

Interim (4-7 years after randomization) and long-term (10-15 years after randomization) evaluation surveys were carried out with baseline household heads and residents who were children at baseline randomization and adolescents at follow-up. Most interim evaluation adolescents were in middle childhood or early adolescence (ages 9-16) at randomization. The 3,689 long-term evaluation adolescents, in comparison, were ages 0-8 at randomization. Long-term evaluation adolescents were selected December, 2007 and interviewed June 2008-April 2010. Interviewers were blinded to group assignment. We targeted 3,501 of the 3,689 long-term evaluation adolescents for interview, including all those from households with 1-3 baseline children and 3 randomly selected adolescents from households with 4+ baseline children (median number of children in these households 1; Range 1-5). Large households were under-sampled to reduce household burden.

Long-term recruitment began with telephone contacts followed by online tracking and telephone networking to locate hard-to-recruit cases. Potential respondents were offered $50 for completing interviews. Although most interviews were face-to-face, some were by telephone for logistical reasons. A random 35% of hard-to-recruit non-respondents were selected near the ending of fieldwork for final intensive recruitment with increased financial incentives.19(P64) Written informed parent consent and adolescent assent were obtained before interviews. These procedures were approved by the Office of Management and Budget, HUD, and the Institutional Review Boards of the National Bureau of Economic Research, University of Chicago, University of Michigan, and Northwestern University.

Measures

Baseline household head questionnaires focused largely on socio-demographics and neighborhood experiences (e.g., social networks, crime victimization). Mental disorders were not assessed (either for heads or for children). Item-level missing data on the variables assessed was <5% for all but 5 variables (youth low birth weight; hospitalization before first birthday; baseline health problems that restricted normal activities; parent education; whether someone read to the child more than once daily during his/her early childhood; 5.5-11.2% missing). Item-level missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation (MI) method20 and 20 MI pseudo-samples. The MI imputations were generated using SAS.21 There were no missing values on the intervention variable.

The long-term evaluation interview included the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),22 a widely-used psychiatric diagnostic evaluation known to have good concordance with blinded clinical diagnoses of the disorders considered here.23 Diagnoses were made for DSM-IV disorders present in the 12 months before interview. CIDI questions were read word-for-word and responses recorded in pre-specified (mostly yes-no) format. Diagnoses were generated by CIDI algorithms operationalizing DSM-IV inclusion criteria. Item-level missing data were <1% for each symptom question and were recoded conservatively to assume the symptom was absent. We focused on 6 DSM-IV/CIDI mood (major depression), anxiety (panic, post-traumatic stress [PTSD]), and disruptive behavior (oppositional-defiant, intermittent explosive, conduct) disorders. Bipolar disorder was also assessed, but was not analyzed due to low prevalence and insufficient statistical power to detect meaningful associations with the individual interventions. (eTable 1 available at http://www.jama.com.)

Statistical Analysis

HUD determined sample size based on MTO budget ($70 million Congressional authorization, additional vouchers from local housing authorities, and nonprofit agencies donating counseling). Randomization was designed to yield equal numbers of families within cities using vouchers in each Intervention group. The number of Control group families invited was set to equal the mean number invited in the 2 Intervention groups. As voucher use percentages were determined only after randomization, proportions randomized across groups were modified during the study to adjust for observed rates of voucher use. HUD determined that this design would yield 0.80 power to detect intervention effects of $2,000 increased earnings in each intervention group with .05-level 1-sided tests.6(pE-4, Exhibit E4) Post hoc power calculations showed that the long-term adolescent sample had at least 0.80 power to detect odds-ratios (ORs) of each of the 2 interventions with each of the 6 disorders considered here of 1.4-1.8 for boys and girls combined. (eTable 1 available at http://www.jama.com.)

Intention-to-treat24 logistic regression analysis25 was used to estimate associations of the Interventions with the outcomes. A weight corrected for across-time variation (the random assignment period was from 1994-1998) in Intervention-versus-Control group selection ratios. Case-level MI based on 20 pseudo-samples was used to adjust for the fact that not all baseline participants completed follow-up interviews. The Taylor series method26 implemented in SUDAAN27 was used to adjust for weighting and clustering (cities, housing projects, families). The significance of sex differences was assessed by estimating a logistic regression equation to predict each disorder that included dummy variables for each intervention, a dummy variable for sex, and 2 dummy variables for the interactions of interventions with sex. A 2 degree of freedom χ2 test was used to evaluate the significance of the interactions. In cases where the test was significant, associations of the interventions with the disorder were considered separately for boys and girls. The evaluation of sex differences was carried out because significant sex differences had been found in previous interim evaluations9-11 and because a qualitative component of the interim evaluation found that low income girls were more likely than boys to profit from the intervention due to differences both in neighborhood experiences and in social skills needed to capitalize on the opportunities created by moving to a better neighborhood.28-30 The 6 mental disorders were considered separately based on evidence that risk factors vary across these disorders.31,32 The Benjamini-Hochberg method33 implemented in SAS21 was used to adjust significance tests across outcomes for the false discovery rate (FDR).

Logistic regression coefficients and standard errors were exponentiated to create ORs and 95% confidence intervals. Mental disorder prevalence estimates in intervention and control groups were used to calculate absolute risk (AR) and absolute risk reduction (ARR). The jack-knife repeated replications method26 implemented in SAS21 was used to generate confidence intervals for the estimates of AR and ARR. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated using .05 level 2-sided tests.

Results

Response Rates

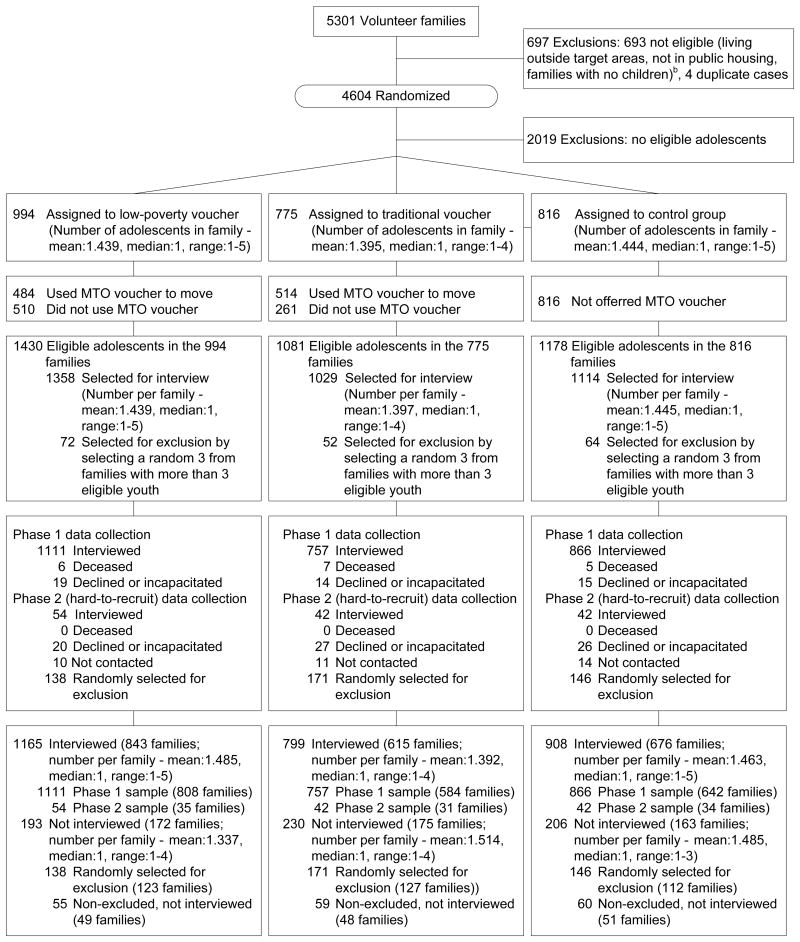

The 3,689 long-term evaluation adolescents were ages 0-8 (median age 4) at baseline and ages 13-19 (median age 16) at the time of the long-term follow-up interviews. A total of 2,872 adolescents were interviewed (1,407 boys and 1,465 girls from 2,134 families; including 1,165 in the Low-poverty voucher intervention group [843 families], 799 in the Traditional voucher intervention group [615 families], and 908 in the Control group [676 families]) from the 3,689 eligible in the baseline sample (a 77.8% participation rate). An additional 643 adolescents were randomly selected for exclusion (188 in families with 4+ eligible respondents; 455 hard-to-recruit) and 174 lost to follow-up (including 18 known to be deceased). (Figure) The weighted response rates were 92.9% (Low-poverty voucher group), 86.9% (Traditional voucher group), and 89.4% (Control group) using the American Association of Public Opinion Research RR1w definition.34(P51) Respondents were more likely to be girls (50.4% [95% CI, 48.3-52.6%] respondents; 38.4% [95% CI, 29.4-47.1%] non-respondents) and Non-Hispanic Black (64.5% [95% CI, 55.9-73.1%] respondents; 51.8% [95% CI, 42.4-61.3%] non-respondents) but did not differ significantly from non-respondents on numerous other baseline personal, family, and neighborhood characteristics. (eTable 2 available at http://www.jama.com.) 22.2% of baseline participants did not complete follow-up interviews. The 18 baseline participants known to be deceased (6 in the Low-poverty voucher group, 7 in the Traditional voucher group, and 5 in the Control group) were excluded from the analysis sample and MI was used to generate 20 pseudo-samples from the remaining 3,671 long-term evaluation adolescent participants (1,424 in the Low-poverty voucher group, 1,074 in the Traditional voucher group, and 1,173 in the Control group). These MI samples were the basis of the analyses reported below.

Figure. Study flow of the long-term MTO adolescent sample evaluationa.

aTarget respondents for the adolescent long-term evaluation included all baseline residents of randomized MTO households who were ages 0-8 at randomization between 1994-1998, 13-17 at selection in December 2007, and 13-19 at interview between June 2008 and April 2010. All adolescents in the eligible age range who lived at baseline in households containing three or fewer youth ages 10 to 20 were targeted for follow-up, while a random three youth were targeted from baseline households with four or more youth. A weight of n/3, where n = the number of eligible youths in the baseline household, was used to adjust for the under-sampling of youths from baseline households containing more than three eligible youth. The term “Phase 1” data collection refers to the efforts made to contact and interview all target respondents until the end of the field period, at which point a random 35% of target respondents who had not yet either been interviewed, were deceased, declined to participate, or were incapacitated (incarcerated or unable to be interviewed due to a barrier related to health or language) were selected for a more intensive “Phase 2” data collection effort that included expanded tracing efforts (e.g., using private investigators to trace target respondents who had not yet been located) and increased financial incentives to obtain interviews from hard-to-recruit youths. A weight of 1/.35 was used to adjust for the under-sampling of the hard-to-recruit youths who were interviewed.

Sample Characteristics

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of adolescents were largely comparable across the Low-poverty voucher, Traditional voucher, and Control groups for both boys (Table 1) and girls (Table 2). Most respondents were Non-Hispanic Black (61.8-66.2%) or Hispanic (27.7-33.2%). The vast majority of respondents were ages 0-5 years of age at baseline (82.2-87.9%), with mean age of 3.6 in each group and range of 0-7 in the Low-poverty voucher group, 0-8 in Traditional voucher and Control groups. The vast majority of baseline families received Aid to Families with Dependent Children (79.1-85.1%). Mean baseline neighborhood poverty rates were 53.6-54.9%.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the MTO adolescent boy long-term evaluation sample in the Low-poverty voucher intervention group, the Traditional voucher intervention group, and the Control groupa.

| Low-poverty Voucher Group (n=713) |

Traditional Voucher Group (n=533) |

Control Group (n=604) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | Est | (95% CI) | P valuec | nb | Est | (95% CI) | P valuec | nb | Est | (95% CI) | P valued | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| I. Respondent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age at baselinee | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 (%) | 602 | 82.2 | (77.9-86.5) | 0.72 | 421 | 82.9 | (79.0-86.8) | 0.99 | 502 | 83.0 | (78.4-87.5) | 0.81 |

| Mean | -- | 3.6 | (3.4-3.9) | 0.82 | -- | 3.6 | (3.4-3.9) | 0.95 | -- | 3.6 | (3.5-3.9) | 0.91 |

| Median (Range) | -- | 4.0 | (0-7) | -- | -- | 4.0 | (0-8) | -- | -- | 4.0 | (0-8) | -- |

| Required special medicine/equipment | 69 | 9.8 | (7.0-12.7) | 0.97 | 64 | 11.2 | (8.4-13.9) | 0.40 | 57 | 9.7 | (7.2-12.3) | 0.68 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic (Any race) | 184 | 27.7 | (19.7-35.7) | 0.34 | 178 | 30.3 | (21.5-39.1) | 0.83 | 197 | 31.0 | (23.9-38.0) | 0.45 |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 14 | 2.0 | (-0.2-4.1) | 0.85 | 9 | 1.8 | (-0.2-3.7) | 0.97 | 12 | 1.8 | (0.4-3.2) | 0.90 |

| African-American (Non-Hispanic) | 483 | 66.2 | (56.7-75.6) | 0.59 | 322 | 63.3 | (53.2-73.4) | 0.99 | 372 | 64.3 | (56.3-72.3) | 0.83 |

| Other race (Non-Hispanic) | 31 | 4.2 | (2.0-6.4) | 0.26 | 23 | 4.6 | (1.4-7.9) | 0.18 | 21 | 3.0 | (1.4-4.6) | 0.17 |

| II. Baseline characteristics of the sample adult | ||||||||||||

| High school diploma (% yes) | 297 | 40.8 | (36.9-44.8) | 0.95 | 207 | 40.5 | (34.3-46.6) | 0.96 | 248 | 40.6 | (35.6-45.7) | 0.99 |

| Currently in school (% yes) | 111 | 15.5 | (12.1-18.9) | 0.15 | 102 | 18.3 | (14.9-21.8) | 0.98 | 108 | 18.4 | (14.4-22.4) | 0.37 |

| Employed (% yes) | 156 | 22.0 | (17.6-26.3) | 0.79 | 114 | 20.1 | (15.5-24.7) | 0.69 | 127 | 21.3 | (16.8-25.7) | 0.97 |

| Never married (% yes) | 485 | 67.4 | (61.7-73.2) | 0.40 | 354 | 67.6 | (60.4-74.8) | 0.46 | 416 | 70.4 | (65.1-75.6) | 0.38 |

| Younger than 18 at birth of first child (% yes) | 217 | 29.6 | (24.1-35.1) | 0.35 | 165 | 31.7 | (25.5-37.8) | 0.12 | 160 | 26.3 | (20.1-32.5) | 0.17 |

| Single mother (% yes) | 613 | 85.5 | (81.2-89.8) | 0.49 | 463 | 86.9 | (82.2-91.6) | 0.95 | 521 | 87.1 | (83.7-90.4) | 0.64 |

| III. Baseline household characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Income (%) | ||||||||||||

| ≤$7,000 | 130 | 17.0 | (11.5-22.6) | 0.85 | 83 | 16.6 | (10.1-23.2) | 0.73 | 96 | 17.5 | (11.1-24.0) | 0.76 |

| $7,001-9,000 | 117 | 16.5 | (12.3-20.6) | 0.90 | 107 | 19.6 | (15.5-23.8) | 0.31 | 102 | 16.8 | (13.2-20.4) | 0.70 |

| $9,001-12,000 | 148 | 20.6 | (16.3-24.9) | 0.33 | 147 | 27.5 | (20.9-34.1) | 0.26 | 143 | 23.1 | (18.9-27.4) | 0.87 |

| $12,001-17,000 | 164 | 23.5 | (19.0-28.0) | 0.05 | 84 | 15.8 | (11.7-19.8) | 0.28 | 119 | 18.2 | (14.2-22.1) | 0.36 |

| $17,001+ | 152 | 22.4 | (17.8-27.0) | 0.43 | 109 | 20.5 | (15.9-25.1) | 0.20 | 142 | 24.3 | (19.8-28.8) | 0.21 |

| Receives AFDC (% yes) | 596 | 83.5 | (79.8-87.3) | 0.08 | 435 | 82.3 | (77.5-87.1) | 0.24 | 476 | 79.1 | (74.8-83.5) | 0.08 |

| Household size (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1-2 | 67 | 9.9 | (6.9-13.0) | 0.50 | 55 | 8.7 | (5.8-11.6) | 0.90 | 54 | 8.4 | (5.7-11.2) | 0.61 |

| 3 | 153 | 21.7 | (18.0-25.3) | 0.01 | 139 | 25.1 | (20.6-29.6) | 0.31 | 166 | 27.9 | (23.6-32.3) | 0.03 |

| 4 | 196 | 28.0 | (24.0-32.0) | 0.05 | 131 | 25.2 | (20.3-30.1) | 0.36 | 135 | 22.6 | (19.0-26.1) | 0.07 |

| 5+ | 297 | 40.4 | (35.4-45.5) | 0.85 | 208 | 41.0 | (36.2-45.7) | 0.98 | 249 | 41.1 | (36.6-45.5) | 0.90 |

| IV. Baseline neighborhood characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Family member victimized past 6 months (% yes) | 293 | 40.8 | (36.9-44.7) | 0.13 | 235 | 44.0 | (37.8-50.1) | 0.81 | 264 | 44.8 | (40.2-49.4) | 0.29 |

| Lived in neighborhood 5 or more years (% yes) | 383 | 52.4 | (47.2-57.6) | 0.57 | 307 | 57.4 | (52.1-62.7) | 0.30 | 325 | 54.3 | (49.2-59.4) | 0.91 |

| Moved more than 3 times in the 5 years (% yes) | 75 | 10.9 | (7.9-13.9) | 0.19 | 51 | 10.0 | (6.8-13.3) | 0.10 | 90 | 14.6 | (10.5-18.7) | 0.10 |

| Family in neighborhood (% yes) | 447 | 64.9 | (57.4-72.4) | 0.38 | 321 | 59.9 | (54.3-65.4) | 0.68 | 377 | 61.7 | (54.8-68.6) | 0.75 |

| Mean poverty rate in census tractf | -- | 53.8 | (49.3-58.4) | 0.79 | -- | 54.9 | (50.1-59.7) | 0.67 | -- | 54.2 | (49.7-58.7) | 0.94 |

| V. City (%) | ||||||||||||

| Baltimore | 78 | 11.9 | (5.5-18.3) | 0.84 | 71 | 13.3 | (6.0-20.6) | 0.61 | 76 | 12.5 | (6.2-18.9) | 0.99 |

| Boston | 125 | 17.4 | (9.7-25.2) | 0.50 | 103 | 20.1 | (11.0-29.1) | 0.77 | 128 | 19.2 | (11.1-27.4) | 0.74 |

| Chicago | 215 | 23.2 | (9.9-36.5) | 0.78 | 109 | 25.4 | (10.9-39.8) | 0.49 | 108 | 22.2 | (10.8-33.5) | 0.62 |

| Los Angeles | 148 | 24.8 | (12.4-37.2) | 0.61 | 126 | 23.0 | (12.2-33.7) | 0.85 | 170 | 23.4 | (11.3-35.5) | 0.78 |

| New York City | 147 | 22.6 | (15.0-30.2) | 0.99 | 124 | 18.3 | (11.8-24.8) | 0.15 | 122 | 22.7 | (14.7-30.6) | 0.47 |

Abbreviation: MTO, Moving to Opportunity; AFDC, Aid to Families with Dependent Children.

Based on multiply-imputed data (described in the text) to adjust for the fact that 22.2% of eligible baseline respondents did not participate in the long-term evaluation survey.

The n's are the mean number of respondents in the group with the outcome averaged across the 20 multiply imputed pseudo-samples.

Compared to controls.

Compared to both intervention groups combined.

Age at long-term follow-up interview had a median age of 16 for both the Low-poverty Voucher Group and Traditional Voucher Group, and a median age of 17 in the control group. The range was 13-19 for all three groups.

The mean poverty rate in census tract is the fraction of residents living below the poverty threshold in the household's baseline census tract. The poverty rate is linearly interpolated from the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses. See http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/about/overview/measure.html for information on how the Census Bureau defines the poverty threshold.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the MTO adolescent girl long-term evaluation sample in the Low-poverty voucher intervention group, the Traditional voucher intervention group, and the Control group a.

| Low-poverty Voucher Group (n=711) |

Traditional Voucher Group (n=541) |

Control Group (n=569) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | % | (95% CI) | P valuec | nb | % | (95% CI) | P valuec | nb | % | (95% CI) | P valued | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| I. Respondent characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age at baselinee | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 (%) | 613 | 83.8 | (79.8-87.9) | 0.86 | 457 | 87.9 | (84.4-91.4) | 0.02 | 479 | 83.5 | (79.6-87.3) | 0.20 |

| Mean | -- | 3.6 | (3.4-3.9) | 0.76 | -- | 3.5 | (3.2-3.7) | 0.06 | -- | 3.7 | (3.4-3.9) | 0.22 |

| Median (Range) | -- | 4.0 | (0-8) | -- | -- | 4.0 | (0-8) | -- | -- | 4.0 | (0-8) | -- |

| Required special medicine/equipment | 60 | 8.1 | (5.7-10.4) | 0.53 | 38 | 6.6 | (3.9-9.4) | 0.89 | 39 | 6.9 | (3.7-10.1) | 0.75 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic (Any race) | 215 | 33.2 | (24.7-41.7) | 0.74 | 163 | 28.2 | (20.7-35.6) | 0.25 | 194 | 32.0 | (24.6-39.4) | 0.75 |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 11 | 2.2 | (-0.4-4.7) | 0.66 | 12 | 2.0 | (-0.3-4.2) | 0.48 | 15 | 2.8 | (0.9-4.6) | 0.57 |

| African-American (Non-Hispanic) | 464 | 61.8 | (51.9-71.6) | 0.89 | 341 | 65.7 | (56.6-74.8) | 0.32 | 341 | 62.3 | (53.8-70.8) | 0.72 |

| Other race (Non-Hispanic) | 19 | 2.9 | (0.8-4.9) | 0.94 | 24 | 4.2 | (1.7-6.6) | 0.32 | 19.0 | 2.9 | (1.2-4.7) | 0.62 |

| II. Baseline characteristics of the sample adult | ||||||||||||

| High school diploma (% yes) | 278 | 38.4 | (32.2-44.7) | 0.63 | 195 | 35.8 | (29.0-42.5) | 0.82 | 212 | 36.7 | (32.1-41.2) | 0.86 |

| Currently in school (% yes) | 135 | 19.4 | (15.2-23.6) | 0.48 | 93 | 16.8 | (13.0-20.7) | 0.79 | 94 | 17.6 | (13.7-21.4) | 0.75 |

| Employed (% yes) | 151 | 22.3 | (18.6-25.9) | 0.93 | 109 | 18.8 | (15.3-22.3) | 0.19 | 127 | 22.1 | (18.3-25.9) | 0.49 |

| Never married (% yes) | 483 | 67.3 | (62.6-72.0) | 0.33 | 370 | 69.5 | (64.2-74.8) | 0.86 | 390 | 70.2 | (64.4-75.9) | 0.51 |

| Younger than 18 at birth of first child (% yes) | 216 | 28.0 | (22.9-33.1) | 0.19 | 164 | 31.1 | (25.3-36.9) | 0.90 | 177 | 31.5 | (26.7-36.2) | 0.35 |

| Single mother (% yes) | 633 | 87.8 | (84.2-91.5) | 0.48 | 470 | 87.1 | (83.3-91.0) | 0.28 | 504 | 89.3 | (86.2-92.4) | 0.32 |

| III. Baseline household characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Income | ||||||||||||

| ≤$7,000 | 143 | 17.6 | (12.0-23.2) | 0.22 | 74 | 14.9 | (8.3-21.5) | 0.80 | 79 | 15.7 | (9.9-21.5) | 0.68 |

| $7,001-9,000 | 134 | 19.5 | (15.4-23.7) | 0.31 | 125 | 22.9 | (17.3-28.5) | 0.09 | 99 | 16.9 | (13.7-20.1) | 0.13 |

| $9,001-12,000 | 174 | 25.3 | (20.2-30.3) | 0.98 | 138 | 25.7 | (20.1-31.3) | 0.91 | 150 | 25.4 | (20.5-30.2) | 0.96 |

| $12,001-17,000 | 144 | 20.3 | (15.5-25.2) | 0.55 | 109 | 19.4 | (15.6-23.2) | 0.31 | 127 | 22.3 | (17.8-26.7) | 0.38 |

| $17,001+ | 113 | 17.2 | (13.5-20.9) | 0.31 | 93 | 17.0 | (12.9-21.1) | 0.25 | 112 | 19.8 | (16.0-23.5) | 0.21 |

| Receives AFDC (% yes) | 598 | 82.9 | (78.9-86.9) | 0.23 | 453 | 85.1 | (81.3-89.0) | 0.07 | 449 | 80.2 | (76.4-83.9) | 0.08 |

| Household size (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1-2 | 72 | 10.8 | (7.8-13.9) | 0.16 | 54 | 9.6 | (6.8-12.4) | 0.62 | 54 | 8.7 | (6.7-10.7) | 0.22 |

| 3 | 186 | 27.4 | (23.3-31.4) | 0.52 | 132 | 24.3 | (19.5-29.2) | 0.70 | 150 | 25.6 | (21.4-29.9) | 0.87 |

| 4 | 191 | 26.4 | (22.7-30.1) | 0.75 | 128 | 22.9 | (18.6-27.3) | 0.38 | 144 | 25.4 | (21.6-29.2) | 0.81 |

| 5+ | 262 | 35.4 | (30.1-40.8) | 0.20 | 227 | 43.1 | (36.6-49.6) | 0.50 | 221 | 40.2 | (34.6-45.8) | 0.67 |

| IV. Baseline neighborhood characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Family member victimized past 6 months (% yes) | 324 | 45.8 | (40.3-51.2) | 0.26 | 207 | 37.9 | (32.3-43.5) | 0.44 | 232 | 41.5 | (34.9-48.1) | 0.84 |

| Lived in neighborhood 5 or more years (% yes) | 359 | 49.3 | (44.8-53.8) | 0.04 | 287 | 51.2 | (44.6-57.8) | 0.21 | 310 | 55.7 | (51.1-60.4) | 0.05 |

| Moved more than 3 times in the 5 years (% yes) | 66 | 9.3 | (7.0-11.6) | 0.12 | 62 | 12.9 | (8.7-17.2) | 0.68 | 70 | 11.9 | (9.1-14.8) | 0.52 |

| Family in neighborhood (% yes) | 435 | 64.6 | (58.6-70.6) | 0.65 | 354 | 65.6 | (60.5-70.8) | 0.47 | 364 | 63.1 | (56.5-69.7) | 0.52 |

| Mean poverty rate in census tractf | -- | 53.7 | (49.0-58.3) | 0.93 | -- | 53.7 | (49.4-57.9) | 0.94 | -- | 53.6 | (49.4-57.7) | 0.93 |

| V. City (%) | ||||||||||||

| Baltimore | 74 | 10.9 | (3.5-18.3) | 0.59 | 79 | 14.3 | (5.8-22.9) | 0.02 | 58 | 10.1 | (2.9-17.3) | 0.12 |

| Boston | 146 | 21.7 | (13.2-30.3) | 0.47 | 92 | 17.7 | (10.1-25.3) | 0.46 | 125 | 19.9 | (12.0-27.8) | 0.97 |

| Chicago | 219 | 23.7 | (11.7-35.8) | 0.56 | 110 | 24.7 | (13.7-35.7) | 0.35 | 102 | 22.3 | (11.8-32.9) | 0.40 |

| Los Angeles | 140 | 23.5 | (12.5-34.5) | 0.92 | 121 | 21.6 | (10.4-32.9) | 0.47 | 161 | 23.2 | (11.3-35.1) | 0.80 |

| New York City | 132 | 20.1 | (13.6-26.7) | 0.09 | 139 | 21.6 | (15.2-28.0) | 0.36 | 123 | 24.5 | (16.7-32.3) | 0.13 |

Abbreviation: MTO, Moving to Opportunity, AFDC; Aid to Families with Dependent Children.

Based on multiply-imputed data (described in the text) to adjust for the fact that 22.2% of eligible baseline respondents did not participate in the long-term evaluation survey.

The n's are the mean number of respondents in the group with the outcome averaged across the 20 multiply imputed pseudo-samples.

Compared to controls.

Compared to both intervention groups combined.

Age at long-term follow-up interview had a median age of 16 for both the Low-poverty Voucher Group and Traditional Voucher Group, and a median age of 17 in the control group. The range was 13-19 for all three groups.

The mean poverty rate in census tract is the fraction of residents living below the poverty threshold in the household's baseline census tract. The poverty rate is linearly interpolated from the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses. See http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/about/overview/measure.html for information on how the Census Bureau defines the poverty threshold.

Twelve-month Mental Disorder Prevalence

The most prevalent 12-month mental disorders were intermittent explosive disorder (14.2-16.0% prevalence among boys and girls, respectively) and oppositional-defiant disorder (6.8-8.4%) followed by major depressive disorder (5.5-7.9%), PTSD (4.4-6.6%), conduct disorder (4.3-1.6%), and panic disorder (4.1-3.7%). (eTable 3 available at http://www.jama.com.)

Associations of Interventions with DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders for Boys and Girls Combined

Adjusting for FDR, respondents in the Low-poverty voucher group had significantly elevated prevalence of PTSD (7.2% [95% CI, 5.7-8.6%]; OR, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.2-2.7]) compared to the Control group (4.2% [95% CI, 3.2-5.2%]). (Table 3) None of the other 11 comparisons of Low-poverty or Traditional voucher groups with the Control group was significant. ORs comparing the Low-poverty voucher group with the Control group were in the range 0.7-1.6 (P=0.13-0.84). ORs comparing the Traditional voucher group with the Control group were in the range 0.9-1.1 (P=0.70).

Table 3. Associations of the MTO interventions with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI disorders among long-term evaluation sample adolescent boys and girls combineda.

| Low-poverty Voucher Group (n=1,424) |

Traditional Voucher Group (n=1,074) |

Control Group (n=1,173) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | (95% CI) | Est | (95% CI) | Est | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| I. Major Depressive Disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 6.8 | (-12.0-25.6) | 6.1 | (-20.1-32.4) | 7.1 | (-21.8-35.9) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 0.3 | (-27.0-27.6) | 1.0 | (-30.7-32.7) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 1.0 | (0.6-1.4) | 0.9 | (0.6-1.3) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.84 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (98) | (66) | (84) | |||

| II. Panic Disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 3.1 | (2.2-4.1) | 4.1 | (2.8-5.3) | 4.7 | (3.2-6.1) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 1.5 | (-0.2-3.3) | 0.6 | (-1.6-2.8) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 0.7 | (0.4-1.1) | 0.9 | (0.5-1.5) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.17 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (52) | (44) | (58) | |||

| III. Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 7.2 | (5.7-8.6) | 4.7 | (3.6-5.8) | 4.2 | (3.2-5.2) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -3.0 | (-4.5- -1.5) | -0.5 | (-1.9-1.0) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 1.8 | (1.2-2.7) | 1.1 | (0.7-1.8) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.03 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (105) | (54) | (48) | |||

| IV. Oppositional-defiant disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 6.2 | (4.8-7.6) | 8.8 | (7.5-10.0) | 8.2 | (6.3-10.1) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 1.9 | (-0.1-4.0) | -0.6 | (-2.8-1.6) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 0.7 | (0.5-1.1) | 1.1 | (0.8-1.5) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.17 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (97) | (89) | (98) | |||

| V. Intermittent explosive disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 13.6 | (11.5-15.8) | 15.4 | (13.4-17.3) | 16.7 | (14.9-18.6) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 3.1 | (-0.2-6.4) | 1.3 | (-1.3-4.0) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 0.8 | (0.6-1.0) | 0.9 | (0.7-1.2) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.13 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (202) | (161) | (196) | |||

| VI. Conduct Disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 3.9 | (3.0-4.9) | 2.2 | (1.0-3.4) | 2.5 | (1.5-3.5) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -1.4 | (-2.7- -0.1) | 0.3 | (-1.2-1.8) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 1.6 | (1.0-2.6) | 0.9 | (0.5-1.7) | 1.0 | -- |

| P value b | 0.13 | 0.70 | ||||

| (n) c | (55) | (21) | (28) | |||

Abbreviations: MTO, Moving to Opportunity; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Based on a series of logistic regression equations comparing respondents in the Low-poverty and Traditional voucher intervention groups with respondents in the Control group ignoring whether or not intervention families used their vouchers. The equations are based on multiply-imputed data (described in the text) to adjust for the fact that 22.2% of eligible baseline respondents did not participate in the long-term evaluation survey.

The P values evaluate the significance of odds-ratios using the Benjamini-Hochberg method33 to adjust for the false discovery rate. These P values are higher than those implied by the 95% CIs, as the latter are based on models for separate outcomes.

The n's are the mean number of respondents in the group with the outcome averaged across the 20 multiply imputed pseudo-samples.

The ORs comparing the Low-poverty and Traditional voucher groups with the Control group varied significantly by respondent sex for 3 of the 6 outcomes after adjusting for FDR: major depression (χ 22=14.1, P=0.007), PTSD (χ 22=9.0, P=0.028), and conduct disorder (χ 22=11.7, P=0.011). Sex differences in these ORs were not significant, in comparison, for panic disorder (χ 22=6.2, P=0.08), oppositional-defiant disorder (χ 22=4.4, P=0.16), or intermittent explosive disorder (χ 22=1.3, P=0.60). Based on these results, the remaining analyses focused on major depression, PTSD, and conduct disorder separately for boys and girls.

Associations of Interventions with DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders Among Boys

Adjusting for FDR, boys had significantly elevated rates of major depression in the Low-poverty voucher group (7.1% [95% CI, 4.1-10.1%]; OR, 2.2 [95% CI, 1.2-3.9]) compared to the Control group (3.5% [95% CI, 2.3-4.6%]), of PTSD in both the Low-poverty voucher group (6.2% [95% CI, 4.7-7.7%]; OR, 3.4 [95% CI, 1.6-7.4]) and the Traditional voucher group (4.9% [95% CI, 3.0-6.8%]; OR, 2.7 [95% CI, 1.2-5.8]) compared to the Control Group (1.9% [95% CI, 0.9-2.9%]), and of conduct disorder in the Low-poverty voucher group (6.4% [95% CI, 4.7-8.1%]; OR, 3.1 [95% CI, 1.7-5.8]) compared to the Control group (2.1% [95% CI, 1.1-3.2%]).(Table 4) Neither of the other 2 comparisons between Intervention and Control groups was significant, with ORs in the range 1.7-2.0 (P=0.23).

Table 4. Associations of the MTO interventions with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI disorders among long-term evaluation sample adolescent sa.

| Low-poverty Voucher Group (n boys = 713, n girls = 711) |

Traditional Voucher Group (n boys = 533, n girls = 541) |

Control Group (n boys = 604, n girls = 569) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | (95% CI) | Est | (95% CI) | Est | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| I. Boys | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 7.1 | (4.1-10.1) | 5.7 | (3.8-7.7) | 3.5 | (2.3-4.6) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -3.7 | (-6.9- -0.4) | -2.3 | (-4.5- -0.1) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 2.2 | (1.2-3.9) | 1.7 | (0.9-3.4) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | 0.03 | 0.23 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (52) | (30) | (22) | |||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 6.2 | (4.7-7.7) | 4.9 | (3.0-6.8) | 1.9 | (0.9-2.9) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -4.3 | (-6.1- -2.5) | -3.0 | (-5.0- -1.0) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 3.4 | (1.6-7.4) | 2.7 | (1.2-5.8) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | 0.007 | 0.05 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (44) | (26) | (10) | |||

| Conduct Disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 6.4 | (4.7-8.1) | 4.2 | (1.9-6.5) | 2.1 | (1.1-3.2) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -4.2 | (-6.4- -2.1) | -2.1 | (-4.5-0.4) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 3.1 | (1.7-5.8) | 2.0 | (0.8-5.1) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | < .001 | 0.23 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (42) | (19) | (13) | |||

| II. Girls | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 6.5 | (4.7-8.3) | 6.5 | (4.5-8.4) | 10.9 | (8.4-13.4) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 4.4 | (1.5-7.3) | 4.4 | (1.3-7.5) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 0.6 | (0.3-1.0) | 0.6 | (0.3-0.9) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | 0.06 | 0.04 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (46) | (35) | (61) | |||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 8.2 | (6.1-10.2) | 4.5 | (3.2-5.7) | 6.7 | (4.8-8.5) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | -1.5 | (-3.8-0.9) | 2.2 | (0.0-4.4) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 1.2 | (0.8-2.1) | 0.7 | (0.3-1.2) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | 0.40 | 0.33 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (60) | (28) | (38) | |||

| Conduct Disorder | ||||||

| Absolute Risk (%) | 1.5 | (0.8-2.1) | 0.3 | (0.0-0.7) | 2.9 | (1.1-4.7) |

| Absolute Risk Reduction (%) | 1.4 | (-0.5-3.3) | 2.6 | (0.7-4.5) | ||

| Odds Ratio | 0.5 | (0.2-1.4) | 0.1 | (0.0-0.4) | 1.0 | -- |

| P valueb | 0.20 | 0.02 | -- | |||

| (n)c | (11) | (2) | (15) | |||

Abbreviations: MTO, Moving to Opportunity; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Based on a series of logistic regression equations comparing respondents in the Low-poverty and Traditional voucher intervention groups with respondents in the Control group ignoring whether or not intervention families used their vouchers. The equations are based on multiply-imputed data (described in the text) to adjust for the fact that 22.2% of eligible baseline respondents did not participate in the long-term evaluation survey.

The P values evaluate the significance of odds-ratios using the Benjamini-Hochberg method33 to adjust for the false discovery rate. These P values are higher than those implied by the 95% CIs, as the latter are based on models for separate outcomes.

The n's are the mean number of respondents in the group with the outcome averaged across the 20 multiply imputed pseudo-samples.

Associations of Interventions with DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders Among Girls

Adjusting for FDR, girls in the Traditional voucher intervention group had significantly reduced rates of major depression (6.5% [95% CI, 4.5-8.4%]; OR, 0.6 [95% CI, 0.3-0.9 ]) compared to the Control group (10.9% [95% CI, 8.4-13.4%]) and of conduct disorder in the Traditional voucher group (0.3% [95% CI, 0.0-0.7%]; OR, 0.1 [95% CI, 0.0-0.4]) compared to the Control group (2.9% [95% CI, 1.1-4.7%]). (Table 4) Number needed to treat among girls (NNT=the inverse of ARR) was 23 for major depression and 38 for conduct disorder. None of the other 4 comparisons between Intervention and Control groups was significant, with ORs in the range 0.5-1.2 (P=0.06-0.40).

Comment

Our post hoc exploratory analysis found that interventions to encourage moving from high-poverty neighborhoods were associated with increased depression, PTSD and conduct disorder among adolescent boys and reduced depression and conduct disorder among adolescent girls who were randomized at ages 0-8. These sex differences were broadly consistent with interim MTO results,8,9,11 which qualitative evidence suggested were due to girls profiting more than boys from moving to better neighborhoods because of sex differences in both neighborhood experiences and in the social skills needed to capitalize on the new opportunities presented by their improved neighborhoods.28-30 The magnitudes of the protective associations of the interventions with 12-month DSM-IV/CIDI disorders among girls were modest in intention-to-treat comparisons (NNT=23-38), although these estimates would, of course, be larger if restricted to movers. It is noteworthy, though, that the ORs were comparable in size to those published in studies of risk factors considered to be of high policy significance in accounting for the outcomes considered here. For example, the elevated ORs of the MTO interventions with PTSD among boys were comparable to the ORs found between combat exposure and PTSD in epidemiological studies of the military,35 while the reduced OR of the MTO interventions with major depression among girls was comparable to the inverse of the OR found in previous research between sexual assault and major depression in epidemiological studies of young women.36 Furthermore, it is important to recognize that these associations were evaluated 10-15 years after randomization. It is not clear if the magnitudes of the associations were stable over this entire time period, but, if so, they would be substantial despite the relatively high levels of NNT. For example, ARR for major depression among girls would be 58.3 person-years per 100 respondents over 15 years if ORs were temporally stable over that entire time period.

That only 23% of eligible families volunteered for MTO reduced external validity. However, it is important to recognize that the public housing population is large and that even this small fraction represents a very large number (over 300,000) of low-income U.S. children,37 making the volunteer families significant from a policy perspective even though they are only a minority of all public housing families. A question might be raised in this regard whether the added costs of developing a special housing intervention for such a small proportion of public housing recipients could be justified by the small proportion accepting the offer, but this concern is mitigated by the fact that many housing economists believe the true costs of housing vouchers are actually lower than those of conventional public housing because of the greater efficiency of the open housing market.18

It is nonetheless difficult to draw policy implications from these results because of the finding that associations have different signs among boys and girls, suggesting that the interventions might have had harmful effects on boys but protective effects on girls. Future government decisions regarding widespread implementation of MTO-like changes in public housing policy will have to grapple with this complexity based on the realization that no policy decision will have benign effects on both boys and girls. The most realistic way to grapple with this complexity might be to attempt to develop more nuanced assignment rules than currently exist or additional intervention elements to mitigate the adverse effects of the intervention on boys while maintaining the protective effects on girls.

Development of such refinements would require a better understanding than we currently have of interacting influences among individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics in leading to child and adolescent mental disorders. While MTO was not designed to produce this kind of understanding, the results reported here should create an impetus to do so by documenting that neighborhoods matter. The challenge for future research is to increase understanding enough to guide allocation of the substantial amount of money spent on public housing in the U.S. each year (more than $36 billion in fiscal year 201238)to maximize the health and well-being of all family members rather than to maximize value for some family members at the expense of other family members.

MTO had several strengths, including an experimental design, large sample size, and long (10-15 year) follow-up. It also had several noteworthy limitations: that only 23% of eligible families volunteered and that the experiment was implemented when unemployment was much lower than today,39 both of which reduce generalizability of results;40 that families offered vouchers had rather severe time limits on enrollment and practical constraints on finding new housing that might have artificially reduced uptake;41 that non-respondents might have differed systematically from respondents; that the CIDI and other mental health measures were not administered at baseline; and that, as with all policy experiments, the MTO design made it impossible to trace out intervening processes that account for aggregate intervention effects. In addition, MTO was under-powered to detect effects of the 2 separate intervention arms on uncommon adolescent mental disorders. Despite these limitations, we found significant associations of the MTO interventions to reduce neighborhood-level poverty with several important adolescent mental disorders, providing rigorous evidence that experimental manipulation of incentives to move is associated with adolescent emotional functioning. However, as the interventions were also associated with changes in many other aspects of neighborhoods and participant experiences, pathways accounting for the associations of the interventions with adolescent mental disorders remain unclear, creating a challenge for future research to develop nuanced decision rules for matching public housing families with neighborhoods to maximize the health and well-being of all family members.

Conclusions

Interventions to encourage moving from high-poverty neighborhoods were associated with elevated major depression, PTSD, and conduct disorder among boys and reduced major depression and conduct disorder among girls. Better understanding of interactions among individual, family, and neighborhood risk factors is needed to guide future public housing policy changes in light of these sex differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support & Role of the Sponsor: Support for the current report was provided by a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (C-CHI-00808), which assisted with the design of the data collection protocol for the long-term MTO study and reviewed this manuscript prior to submission to ensure the manuscript does not violate the confidentiality of MTO program participants, but had no other involvement with the study. The other funders of the project had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. These funders are the following: the National Science Foundation (SES-0527615), the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD040404, R01-HD040444), the Centers for Disease Control (R49-CE000906), the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH077026), the National Institute for Aging (P30 AG012810, R01-AG031259, P01-AG005842-22S1), the National Opinion Research Center's Population Research Center (through R24-HD051152-04 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development), University of Chicago's Center for Health Administration Studies, the U.S. Department of Education/Institute of Education Sciences (R305U070006), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Russell Sage Foundation. The work of Duncan was additionally supported in part by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator in Health Policy award, while the work of Ludwig was additionally supported in part by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator in Health Policy award, a Russell Sage Foundation visiting scholar award, and a visiting scholar award from LIEPP at Sciences Po. Outstanding assistance with the data preparation and analysis was provided by Joe Amick, MPA, Ryan Gillette, MPP, Ijun Lai, MPP, Jordan Marvakov, PhD, Nicholas Potter, MS, Matt Sciandra, MPP, Fanghua Yang, MPP Sabrina Yusuf, MPP, and Michael Zabek, BA at the National Bureau of Economic Research and by Irving Hwang, MA, Maria Petukhova, PhD, Nancy A. Sampson, BA, and Benjamin Wu, MS, at Harvard Medical School, each of whom was an employee of our research team for this study. The survey data collection effort was led by Nancy Gebler, MA, PMP at the University of Michigan's Survey Research Center under subcontract to our research team. Helpful comments were provided by Todd M. Richardson, MPP and Mark D. Shroder, PhD of HUD.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Kessler and Ludwig had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kessler, Duncan, Gennetian, Katz, Kling, Sanbonmatsu, Ludwig

Acquisition of data: Gennetian, Sanbonmatsu, Ludwig

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kessler, Duncan, Gennetian, Katz, Kling, Sampson, Sanbonmatsu, Zaslavsky, Ludwig

Drafting of the manuscript: Kessler

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Duncan, Gennetian, Katz, Kling, Sampson, Sanbonmatsu, Zaslavsky, Ludwig.

Statistical analysis: Kessler, Duncan, Katz, Kling, Zasavsky, Ludwig

Obtaining funding: Katz, Kling, Ludwig

Study supervision: Kessler, Gennetian, Sampson, Sanbonmatsu, Zaslavsky, Ludwig

Administrative, technical, or material support: Gennetian, Sanbonmatsu

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline Inc., Health Core Inc., Health Dialog, Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc., Integrated Benefits Institute, J & J Wellness & Prevention, Inc., John Snow Inc., Kaiser Permanente, Lake Nona Institute, Matria Inc., Mensante, Merck & Co, Inc., Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc., Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US Inc., SRA International, Inc., Takeda Global Research & Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst. Dr. Kessler has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly & Company, Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Johnson & Johnson, Plus One Health Management and Wyeth-Ayerst. Dr. Kessler has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Analysis Group Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs., Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US, Inc., and Walgreens Co. Dr. Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc. Dr Gennetian has served on advisory boards for Family Self Sufficiency TWG, Administration for Children and Families; and NORC, University of Chicago. Dr Katz has served on advisory boards for Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation and the Russell Sage Foundation. Dr Ludwig serves on advisory boards (uncompensated) for UCAN (Chicago), and the Board on Children, Youth and Families IOM/NAS; and has served as a consultant for the MacArthur Foundation Network on Children and Housing and the MDRC Early Childhood Institute. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: Any errors and all opinions are our own. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as those of the Congressional Budget Office, HUD, or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Dr Ronald C. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr Greg J. Duncan, School of Education University of California, Irvine.

Dr Lisa A. Gennetian, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Dr Lawrence F. Katz, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Department of Economics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Dr Jeffrey R. Kling, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Congressional Budget Office, Washington, District of Columbia.

Ms. Nancy A. Sampson, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr Lisa Sanbonmatsu, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Dr Alan M. Zaslavsky, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr Jens Ludwig, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, Chicago Illinois.

References

- 1.Leventhal T, Dupere V, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood influences on adolescent development. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 411–443. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galster GC. The mechanism(s) of neighborhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. In: van Ham M, Manley D, Bailey N, Simpson L, Maclennan D, editors. Neighborhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhui KS, Lenguerrand E, Maynard MJ, Stansfeld SA, Harding S. Does cultural integration explain a mental health advantage for adolescents? Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):791–802. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed May, 1 2013];Healthy Communities Program. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/healthycommunitiesprogram/

- 6.Feins JD, Holin MJ, Phipps AA, Magri D. Implementation assistance and evaluation for the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration: final report. [Accessed October 6, 2006];1995 www.abtassociates.com/reports/D19950045.pdf.

- 7.Feins JD, Hollin MJ, Phipps A. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration: Program operations manual (revised) [Accessed October 6, 2010];1996 http://www.abtassociates.com/reports/D19960002.pdf.

- 8.Orr L, Feins JD, Jacob R, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Interim Impacts Evaluation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75(1):83–119. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leventhal T, Dupere V. Moving to Opportunity: does long-term exposure to ‘low-poverty’ neighborhoods make a difference for adolescents? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(5):737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osypuk TL, Tchetgen EJ, Acevedo-Garcia D, et al. Differential mental health effects of neighborhood relocation among youth in vulnerable families: results from a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1284–1294. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig J. Guest editor's introduction. Cityscape. 2012;14:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults: evidence from a randomized experiment. Science. 2012;337:1505–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes--a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gennetian LA, Sciandra M, Sanbonmatsu L, et al. The long-term effects of Moving to Opportunity on youth outcomes. Cityscape. 2012;14:137–168. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goering J, Feins JD, Richardson TM. What have we learned from housing mobility and poverty deconcentration? In: Goering J, Feins JD, editors. Choosing a Better Life? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census Tracts and Block Numbering Areas. [Accessed March 5, 2011]; http://www.census.gov/history/www/programs/geography/tracts_and_block_numbering_areas.html.

- 18.Olsen EO. Housing programs for low-income households. In: Moffitt RA, editor. Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2003. pp. 365–442. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebler N, Hudson ML, Sciandra M, Gennetian LA, Ward B. Achieving MTO's high effective response rates: strategies and tradeoffs. Cityscape. 2012;14(2):57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):472–489. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® Software, Version 9.2 for Unix. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, et al. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gravel J, Opatrny L, Shapiro S. The intention-to-treat approach in randomized controlled trials: are authors saying what they do and doing what they say? Clin Trials. 2007;4(4):350–356. doi: 10.1177/1740774507081223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression, Second Edition. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN (Release 10.0.1) [Computer Software] Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs X, Popkin SJ, Goering J. Moving to Opportunity: The Story of an American Experiment to Fight Ghetto Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter PL. “Black” cultural capital, status positioning, and schooling conflicts for low-income African American youth. Social Problems. 2003;50(1):136–155. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clampet-Lundquist S, Kling JR, Edin K, Duncan GJ. Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighborhoods: how girls fare better than boys. AJS. 2011;116(4):1154–1189. doi: 10.1086/657352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin KA, Greif Green J, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions. [Accessed April 12, 2012];2012 www.aapor.org/Standard_Definitions/1481.htm.

- 35.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):843–852. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maercker A, Michael T, Fehm L, Becker ES, Margraf J. Age of traumatisation as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder or major depression in young women. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:482–487. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Public housing: image versus facts. [Accessed May 1, 2013];1995 http://www.huduser.org/periodicals/ushmc/spring95/spring95.html.

- 38.Congressional Budget Office. Growth in means-tested programs and tax credits for low income households. [Accessed May 12, 2013];2013 http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43935.

- 39.Lee MA, Mather M. U.S. labor force trends. Popul Bull. 2008;63(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goering J, Kraft J, Feins D, McInnis D, Holin MJ, Elhassan H. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Current Status and Initial Findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shroder MD. Locational constraint, housing counseling, and successful lease-up in a randomized housing voucher experiment. J Urban Econ. 2002;51(2):315–338. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.