Abstract

Background

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a neurodegenerative, sporadic disorder of unknown cause. Few familial cases have been described.

Objective

We aim to characterize the clinical, imaging, pathological and genetic features of two familial cases of CBD.

Methods

We describe two first cousins with CBD associated with atypical MRI findings. We performed exome sequencing in both subjects and in an unaffected first cousin of similar age.

Results

The cases include a 79-year-old woman and a 72-year-old man of Native American and British origin. The onset of the neurological manifestations was 74 and 68 years respectively. Both patients presented with a combination of asymmetric parkinsonism, apraxia, myoclonic tremor, cortical sensory syndrome, and gait disturbance. The female subject developed left side fixed dystonia. The manifestations were unresponsive to high doses of levodopa in both cases. Extensive bilateral T1-W hyperintensities and T2-W hypointensities in basal ganglia and thalamus were observed in the female patient; whereas these findings were more subtle in the male subject. Postmortem examination of both patients was consistent with corticobasal degeneration; the female patient had additional findings consistent with mild Alzheimer’s disease. No Lewy bodies were found in either case. Exome sequencing showed mutations leading to possible structural changes in MRS2 and ZHX2 genes, which appear to have the same upstream regulator miR-4277.

Conclusions

Corticobasal degeneration can have a familial presentation; the role of MRS2 and ZHX2 gene products in CBD should be further investigated.

Keywords: corticobasal degeneration, corticobasal syndrome, apraxia, genetics, progressive supranuclear palsy

Introduction

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is clinically defined by progressive asymmetric rigidity, apraxia, alien limb phenomenon, myoclonus, and dystonia with pathology consisting of cortical ballooned neurons, frontoparietal neuronal loss with gliosis, and nigral and basal ganglia degeneration [1]. Some reports suggest increased iron deposition but data is mixed [2,3,4]. In the following decades it became evident that corticobasal syndrome (CBS) is the main presentation in patients with corticobasal pathology, but other pathologies including Alzheimer’s disease, fronto-temporal lobe degeneration (FTLD), progressive supranuclear palsy, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease can present as CBS [1]. Alternatively, CBD pathology can occasionally present as other clinical syndromes such as the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) or primary progressive aphasia [5]. Increased iron deposition may be seen [3], but CBD is considered a sporadic disorder characterized by hyper-phosphorylation of tau protein and microtubule dysfunction of unknown cause.

Two gene mutations usually associated with frontotemporal dementia, microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) [6] and progranulin (PRGN) [5, 7], have rarely presented as CBD. Familial G2019S heterozygous mutation of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) has been reported to cause CBS unresponsive to levodopa [8]. LRRK2 G2019S has also been identified to segregate with tau-positive parkinsonism without apraxia, and Lewy bodies, in an affected family [9]. To date no gene has been associated specifically with CBS.

In this report, we aim to characterize the clinical, imaging, pathological, and genetic features of two familial cases of CBD.

Materials and Methods

Clinical evaluation

Both patients were evaluated by movement disorders experts at a tertiary referral center. The patients were videotaped after obtaining written informed consent from a legal proxy.

Pedigree

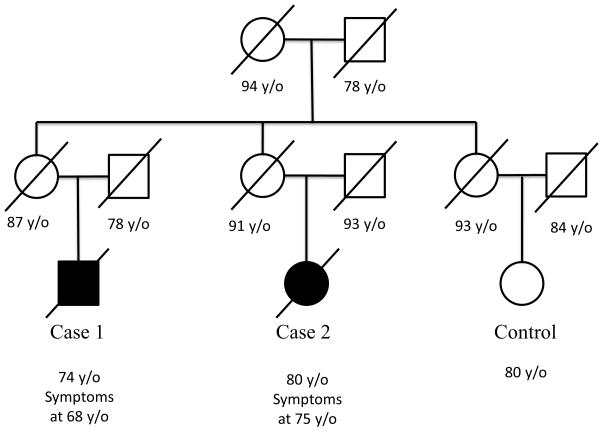

The pedigree was verified using a search of electronically available genealogical records as well as obituary notices. The family is of Native American and English descent (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pedigree of two affected individuals and unaffected control.

Pathological evaluation

Serial coronal sections through the cerebral hemispheres and serial transverse sections through the brainstem were performed on both cases. Microscopic sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin as well as immunologically stained for beta-amyloid, tau, TAR-DNA binding protein (TDP)-43, and alpha-synuclein. Phosphorylated neurofilament protein immunostain was used for selected sections. Perls stain was used to visualize iron deposits.

DNA Hybridization

DNA from individuals was obtained under written informed consent for participation in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. Five μg of DNA was sheared and hybridized to a custom probe set (VCR) as previously described [10]. The DNA was eluted and amplified for 7 PCR cycles prior to sequencing [11].

Sequencing, Alignment, Variant Calling and Annotation

Sequence data was generated on the Illumina GA2 platform and was aligned to the human reference genome (HG18) with BWA [12]. Discrepancies between the aligned reads and the human reference were identified with SAMtools [13]. Variants were filtered for quality, annotated with gene information, gene function and minor allele frequency using internally developed tools and AnnoVar [14].

Structure Prediction and Pathway Analysis

PolyPhen-2 [15] was used for prediction of mutation impact on protein structure and function. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems, Inc., http://www.ingenuity.com, Redwood City, CA) was used to analyze relationships among identified genes and construct a network, with statistical analysis by Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Case 1

This 72-year-old right handed man presented for evaluation of gait imbalance, right-arm tremor and using inappropriate objects to perform certain actions with the right hand beginning at age 68. Two years later, the left side became involved. He began to have difficulty typing. The examination showed impaired vertical opto-kinetic nystagmus and moderate slowing of horizontal and vertical saccades. There was moderate right sided and mild left sided upper and lower extremity bradykinesia and rigidity. He had mild bilateral myoclonic rest and action tremor (video 1). There was mildly asymmetric bilateral ideomotor apraxia and finger agnosia, complete agraphia, and difficulty with serial seven substraction beyond 93 in addition to mild bilateral proprioceptive loss. There was generalized hyperreflexia without Babinski sign. Gait was ataxic with a wide base. During our interview, the patient stated that he “doesn’t like his thumbs, because sometimes they feel like they are not a part of his body”, but no overt alien hand syndrome was noticed. There was no benefit from levodopa except for mild initial improvement of tremor. The patient received a score of 17/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Examination (MOCA). The patient became bedbound and died approximately two years later from pneumonia and sepsis.

Case 2

This is a 79-year-old, right-handed woman, first cousin of case 1. She was referred to our center for evaluation of atypical parkinsonism. The neurological manifestations started at age 74 with postural and kinetic tremor affecting the left hand, followed weeks later by generalized slowness and shuffling gait. At age 75, she noticed deterioration of the left arm tremor, loss of dexterity/motor function, and rapidly progressive elbow, wrist and shoulder joint contracture, leading to complete loss of function and fixed posture of that limb by age 77 (video 1). At that time, a postural and kinetic tremor appeared in the right arm. Her gait became progressively unsteady, associated with several falls, which confined her to a wheelchair. No evidence of alien-limb phenomenon was observed. Work-up was unremarkable, including ceruloplasmin and ferritin levels. The tremor and parkinsonism did not respond to high doses of primidone and levodopa.

Imaging

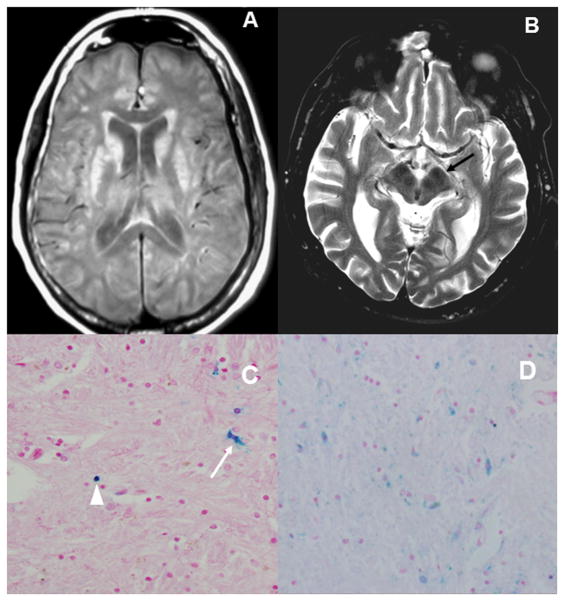

Extensive bilateral T1-W hyperintensities and T2-W hypointensities in the basal ganglia and thalamus were observed in the female patient; whereas these findings were present but subtle in the male subject (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A) Axial T1W MRI in case 2 shows hyperintensities in both caudate nuclei and putamen B) Axial T2W MI in case 1 shows prominent hypointensites in the red nuclei and substantia nigra (arrow); these findings suggests brain deposition of iron/metal in both cases. C) Histopathology via Perls stain of case 2, confirmed astrocyte cytoplasm iron deposits (arrow) and iron in neuronal spheroids (arrowhead). D) Perls stain showing more pronounced iron deposits in case 1.

Neuropathological findings

Postmortem examination of the brains was consistent with corticobasal degeneration in both subjects. Case 1 showed glial tau-positive inclusions, neuronal-tau positive inclusions, astrocytic plaques, scarce swollen (achromasic) neurons in the temporo-parietal and occipital cortex; but frequent achromatic cells were observed in the globus pallidus interna and externa. There was surface-layer spongiosis. Mild asymmetric inter-hemispheric atrophy was observed, more prominent in the right frontal lobe. Marked Perls staining of neuronal spheroids and astrocyte cytoplasm demonstrates abnormal iron deposition (Figure 2) [16]. Staining was in excess of Case 2, showed scattered tau positive inclusions in neurons and glia in the basal ganglia and thalamus. Marked diffuse gliosis was also noted in these areas. Rare ballooned neurons were observed in the parietal lobes. There was marked diffuse cortical atrophy, more prominent in the right parietal lobe. Both cases showed moderate pigment incontinence in the substantia nigra, without any Lewy bodies. Neuropil threads were seen in the gray and white matter of left (sparse) and right (moderate) frontal lobes, gray, including primary motor cortices, and white matter on fronto-parietal cuts (numerous, more prominent on the right), and sparsely in the temporal and occipital lobes. Astrocytic plaques, a hallmark of CBD pathology [17], were seen in the right frontal cortex. Coiled bodies, seen in both PSP and CBD, were seen occasionally in the gray and white matter of the parietal lobes, and rarely in the temporal lobes. Neuronal spheroids and astrocyte cytoplasm were positive on Perls staining (Figure 2).

Genetic Analysis

Case 1 underwent commercial genetic tests for FXTAS, progranulin, and MAPT mutations (Athena Diagnostics, Worcester, MA), which were negative. LRRK2, MAPT, and PRGN mutations were confirmed negative in both cases via exome sequencing. 222 genes were shared between the affected cases (Supplemental Table 1). Genes expressed in neurons and glia as well as cell cycle regulatory genes were selected for Sanger validation and sequencing, with ZHX2 and PLEKHB2 added on subsequent review. FA2H mutation failed Sanger validation.

A mutation in a highly conserved region of the AGBL5 gene in chromosome 2 was observed in both affected subjects; but not in a first cousin of similar age without neurological manifestations. PolyPhen predicts this mutation as benign. Four other genes showed a possible mutation in the affected subjects only: FANCL (E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase), PLEKHB2, MRS2 (Mg2+ transporter), ZHX2 (zinc-finger and homeodomain protein 2) (Supplemental Table 2). PLEKHB2 mutation was predicted as possibly benign, while MRS2 and ZHX2 were possibly damaging. Network of relationships between these genes was constructed via IPA software (Supplementary Figure 1). MRS2, PLEKHB2, and ZHX2 appear to have the same upstream regulator miR-4277 with p=1.99*10−4. Additional network information is listed in Supplemental Table 2. Compound heterozygous and recessive inheritance was not considered, which is a limitation of our study.

Discussion

We report two first cousins of Native American and English origin with CBS and underlying pathology consistent with CBD and modestly increased iron deposition. These subjects showed a similar mutation in a highly preserved region of the AGBL5 (ATP/GTP binding protein-like 5) gene which codes for a recently described tubulin deglutamylating enzyme, a metallocarboxypeptidase called cytosolic carboxypeptidase-like protein 5 (CCP5) [18]. Disruption of microtubule deglutamylation would be an intriguing mechanism for this disorder, but unfortunately this mutation appears to be benign via PolyPhen sequence prediction.

MRS2 gene product is expressed in neuronal cells and to a smaller degree in oligodendrocytes, on the inner membrane of mitochondria [19]. It is a Mg2+ channel whose experimental disruption in rodents has been linked to demyelination as well as findings consistent with mitochondrial disease including elevated CSF lactic acid concentration and reduced ATP concentration. Zinc finger and homeoboxes 2 (ZHX2) gene product functions as a transcriptional regulator [20] and has been implicated in control of neuronal differentiation [21]. These genes have not been previously reported in human late onset neurological disease. While the actual pathogenic mechanism of these mutations in CBD is unclear, it is of interest that MRS2, PLEKHB2, and ZHX2 appear to have the same upstream regulator miR-4277.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Network prediction by IPA software

Supplemental Table 1: Details of identified genes.

Supplemental Table 2: Additional network information as calculated by IPA software

Supplemental File: Exome sequencing raw data

Supplementary Video 1: Clinical features of both cases, including profound apraxia, are demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the advice of Dr. Carsten Janke of Centre de Recherches de Biochimie Macromoleculaire, Montpelier, France.

References

- 1.Mathew R, Bak TH, Hodges JR. Diagnostic criteria for corticobasal syndrome: a comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:405–10. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Double KL, Jellinger K, Zecca L, Youdim MBH. Iron, Neuromelanin, and alpha-Synuclein in Neuropathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. In: Zatta PF, editor. Metal Ions and Neurodegenerative Disorders. World Scientific Publishing Co; Singapore: 2003. pp. 343–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuno Y, Ozeki M, Iwata H, Takeuchi T, Ishihara R, Hashimoto N, et al. A case of clinically and neuropathologically atypical corticobasal degeneration with widespread iron deposition. Acta Neuropathologica. 2002;103:288–94. doi: 10.1007/s004010100460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molinuevo JL, Munoz E, Valldeoriola F, Tolosa E. The eye of the tiger sign in cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration. Mov Disord. 1999;14:169–71. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199901)14:1<169::aid-mds1033>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houlden H, Baker M, Morris HR, MacDonald M, Pickering-Brown S, Adamson J, et al. Corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy share a common tau haplotype. Neurology. 2001;56:1702–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi G, Marelli C, Farina L, Laurà M, Basile AM, Ciano C, et al. The G389R mutation in the MAPT gene presenting as sporadic corticobasal syndrome. Mov Disord. 2008;23:892–95. doi: 10.1002/mds.21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppola C, Rossi G, Barbarulo AM, Di Fede G, Foglia C, Piccoli E, et al. A progranulin mutation associated with cortico-basal syndrome in an Italian family expressing different phenotypes of fronto-temporal lobar degeneration. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:93–7. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen-Plotkin AS, Yuan W, Anderson C, Wood EM, Hurtig HI, Clark CM, et al. Corticobasal syndrome and primary progressive aphasia as manifestations of LRRK2 gene mutations. Neurology. 2008;70:521–7. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000280574.17166.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajput A, Dickson DW, Robinson CA, Ross OA, Dächsel JC, Lincoln SJ, et al. Parkinsonism, LRRK2 G2019S, and tau neuropathology. Neurology. 2006;67:1506–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240220.33950.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bainbridge MN, Wang M, Wu Y, Newsham I, Muzny DM, Jefferies JL, et al. Targeted enrichment beyond the consensus coding DNA sequence exome reveals exons with higher variant densities. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bainbridge MN, Wang M, Burgess DL, Kovar C, Rodesch MJ, D’Ascenzo M, et al. Whole exome capture in solution with 3 Gbp of data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Network prediction by IPA software

Supplemental Table 1: Details of identified genes.

Supplemental Table 2: Additional network information as calculated by IPA software

Supplemental File: Exome sequencing raw data

Supplementary Video 1: Clinical features of both cases, including profound apraxia, are demonstrated.