To the Editor

We advise caution in applying the claim-based algorithm developed by Callahan et al1 to identify suicidal behavior using claims data. The Callahan et al. method uses external cause of injury codes (E-codes) in combination with diagnosis codes for poisoning derived from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) coding scheme to identify hospitalizations for suicide attempts.

In recent years there has been considerable concern that suicidal behavior is a potential adverse outcome of prescription drug use such as antidepressant and anticonvulsant agents.2 Non-fatal, deliberate self-harms resulting in emergency department treatments and hospitalizations can be identified in administrative databases using E-codes.3-5 These codes are part of the ICD-9-CM and are used to provide information about the cause and intent of an injury or poisoning. E-coding is mandatory in about half of US states,6 and the completeness of E-codes in state hospital discharge databases typically exceeds 90%.7 As part of a study of effects of safety warnings for antidepressants and suicidality in youth, we assessed the completeness of E-codes in commercial health plan databases.

Methods

Our analysis included 10 geographically distinct healthcare organizations in the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN)8 within the HMO Research Network (HMORN). The health plans had a combined population of 9 million enrollees in 2010. This analysis was part of a longitudinal study of effects of Food and Drug Administration warnings for antidepressants and suicidality in youth that was approved by the institutional review board of each participating organization.

We used data from the HMORN Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW).9-13 The VDW is a common data model in which the data elements at each site are harmonized to enable collaborative, multi-site research projects. The VDW contains demographics, health plan enrollment, inpatient and outpatient utilization (e.g., diagnoses, procedures, service dates), and pharmacy dispensings. The quality of these data has been previously validated;9-13 however, the reliability of E-codes in the VDW has not been assessed.

We calculated the completeness of E-codes, defined as the proportion of encounters with an injury/poisoning ICD-9-CM code that had a valid E-code indicating the cause for the encounter.3 As in prior research,3 we identified hospitalizations and ED visits with a primary or secondary diagnosis of injury/poisoning. We focused on injuries that are likely methods of deliberate self-harm: open wound injuries, superficial injuries, and poisonings. Because E-code collection and reporting requirements vary temporally and by region, we assessed E-code completeness rates from 2000 through 2010 by MHRN site and care setting. A V-code (supplemental information about factors influencing health service use) was introduced in 2005 indicating suicidal ideation (ICD-9: V62.84). In a sensitivity analysis, we calculated E-code completeness, while also including V62.84 that could be used in place of E-codes to identify a suicidal related encounter.

Results

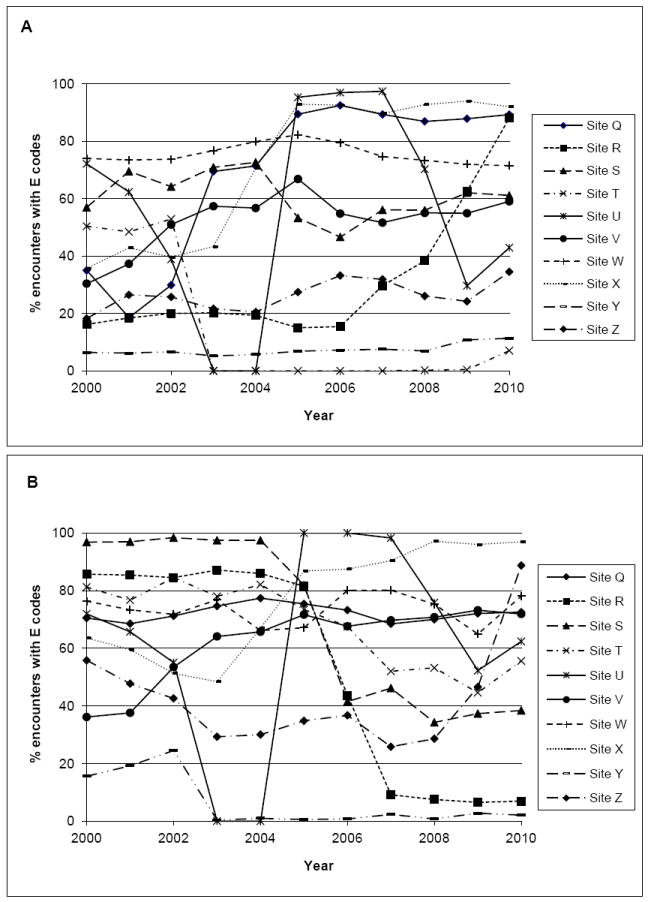

Figure 1 presents E-code completeness rates in emergency department and hospital settings over time. E-code completeness varied widely across study sites (e.g., ranging from 7% to 92% in the emergency department setting in 2010), across treatment settings (e.g., ranging from 7% to 56% at one study site in 2010), and across years (e.g., ranging from 36% in 2000 to 92% in 2010 at one study site). Only two sites had consistent, reasonable levels of E-code recording over this period (range: 65% to 82%). Our investigation indicates the suicidal ideation code did not substitute or compensate for lack of E-codes with injury/poisoning diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Proportion of injury and poisoning encounters that had a valid E-code in (A) emergency rooms and (B) hospitals by study site (2000-2010)

Comment

In our analysis of VDW data from 10 HMORN sites between 2000 and 2010, we found that E-code completeness varied across study sites, across treatment settings, and across years of observation. There are several possible reasons for the low rates of and/or variability in E-code completeness observed: E-codes have no relevance for payments;3 not all diagnosis codes are transformed into the VDW from source data; and recording practice for E-codes may vary across sites, possibly due to state regulations, health plan policies, or the clinical software used. The incompleteness we observed in this study limits the usefulness of the available E-coded data. Other studies also found high missingness of E-codes in hospital and emergency department settings.3,14-17

Despite the high positive predictive value of 85% reported by Callahan et al1, there are two issues relating to the use of the algorithm: (1) the completeness of E-codes in the dataset, and (2) the dependence on valid E-coded data.

We agree with Callahan et al that it is important to develop and use alternative diagnosis codes that can identify suicide attempts. In the absence of complete E-codes, Patrick et al developed and tested algorithms for identifying hospitalizations for deliberate self-harm in a population aged 10 and over.3 This study used the US National Inpatient Sample data and data from British Columbia; both data sources had E-code completeness rates above 85 percent. The gold standard for deliberate self-harm was defined as hospitalizations with a diagnosis of E950-958. Patrick et al found that an algorithm combining diagnoses for psychiatric disorders (including depression) and injury/poisoning can produce a positive predictive value as high as 87.8% for identifying hospitalizations for deliberate self-harm (with specificity of 99.4% and sensitivity of 57.3%).

In the context of our study on the impact of Food and Drug Administration warnings for antidepressants and suicidality in youth, Patrick’s algorithm would introduce selection bias because rates of depression diagnosis declined after the warning.24,25,28 A diagnosis of ‘poisoning by psychotropic agents’ alone outperformed other injury/poisoning types; its positive predictive value was 79.7% with specificity of 99.3% and sensitivity of 38.3%.3 While psychotropic drug poisoning underestimate rates of suicide attempts because of its low sensitivity, it can be useful for detecting suicide attempts in study settings that have low or inconsistent E-code rates over time. Such consistency is required for longitudinal analyses of trends in deliberate self-harms.

In summary, our analysis confirmed that E-codes were substantially incomplete in commercial insurance claims databases. We observed that E-code completeness varied widely across MHRN sites, across treatment settings, and over time. Completeness improved at some sites and deteriorated at other sites. Psychotropic drug poisonings may be useful for identifying deliberate self-harm requiring hospitalization in commercial plan databases when E-codes are missing. Further research is warranted to validate the reliability of algorithms using data from emergency departments. Importantly, greater efforts are needed to improve the use of external cause of injury codes in commercial health plan databases.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant: U19MH092201). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

All authors report grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study. Dr. Zhang received personal fees from Policy Analysis Inc. outside the submitted work. Dr. Penfold received research funding from Bristol-Meyers Squibb for a study regarding antipsychotic augmentation therapy for major depression in adults only.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: No other financial disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Callahan ST, Fuchs DC, Shelton RC, et al. Identifying suicidal behavior among adolescents using administrative claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013 Feb 15; doi: 10.1002/pds.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Strategies for quantifying the relationship between medications and suicidal behaviour: what has been learned? Drug Saf. 2011 May 1;34(5):375–395. doi: 10.2165/11589350-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patrick AR, Miller M, Barber CW, Wang PS, Canning CF, Schneeweiss S. Identification of hospitalizations for intentional self-harm when E-codes are incompletely recorded. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010 Dec;19(12):1263–1275. doi: 10.1002/pds.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, et al. Comparative safety of antidepressant agents for children and adolescents regarding suicidal acts. Pediatrics. 2010 May;125(5):876–888. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, et al. Variation in the risk of suicide attempts and completed suicides by antidepressant agent in adults: a propensity score-adjusted analysis of 9 years’ data. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 May;67(5):497–506. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walkup JT, Townsend L, Crystal S, Olfson M. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying suicide or suicidal ideation using administrative or claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012 Jan;21(Suppl 1):174–182. doi: 10.1002/pds.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; Data Committee Injury Control and Emergency Health Services Section APHAaSaTIPDA. How States are Collecting and Using Cause of Injury Data: 2004 Update to the 1997 Report. [Dec 26, 2012];2005 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mental Health Research Network. Mental Health Research Network. [April 2, 2013]; https://sites.google.com/a/mhresearchnetwork.org/mhrn/

- 9.Li LL, Miroshnik I. VDW data sources: Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2012;10(3):191. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardee R, Hart G, Tolbert W, Key D, Ross T. VDW data sources: Group Health. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2012;10(3):193. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chimmula S, Dhuru R, Folck B, et al. VDW data sources: Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2012;10(3):193. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavel H, Gupta A, Tabano D. VDW data sources: Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2012;10(3):196. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butani A, Ovans L. VDW data sources: HealthPartners Research Foundation. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2012;10(3):196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DE, DeLorenzo MA, Lucas FL, Wennberg DE. Epidemiology and short-term outcomes of injured medicare patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Dec;52(12):2023–2030. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt PR, Hackman H, Berenholz G, McKeown L, Davis L, Ozonoff V. Completeness and accuracy of International Classification of Disease (ICD) external cause of injury codes in emergency department electronic data. Inj Prev. 2007 Dec;13(6):422–425. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.015859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence BA, Miller TR, Weiss HB, Spicer RS. Issues in using state hospital discharge data in injury control research and surveillance. Accid Anal Prev. 2007 Mar;39(2):319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annest JL, Fingerhut LA, Gallagher SS, et al. Strategies to improve external cause-of-injury coding in state-based hospital discharge and emergency department data systems. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(RR01):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]