Abstract

Miro GTPase, a member of the Ras superfamily, consists of two GTPase domains flanking a pair of EF hand motifs and a C-terminal transmembrane domain that anchors the protein to the mitochondrial outer membrane. Since the identification of Miro in humans, a series of studies in metazoans, including mammals and fruit flies, have shown that Miro plays a role in the calcium-dependent regulation of mitochondrial transport along microtubules. However, in non-metazoans, including yeasts, slime molds, and plants, Miro is primarily involved in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis. Given the high level of conservation of Miro in eukaryotes and the variation in the molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial transport between eukaryotic lineages, Miro may have a common ancestral function in mitochondria, and its roles in the regulation of mitochondrial transport may have been acquired specifically by metazoans after the evolutionary divergence of eukaryotes.

Keywords: mitochondria, Miro, Ras GTPase, metazoan, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Dictyostelium discoideum, Arabidopsis thaliana

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria are essential organelles for aerobic energy production and metabolism in eukaryotic cells. They frequently undergo changes in morphology and intracellular distribution through fusion, fission, and cytoskeleton-dependent transport, presumably to sustain their functional homeostasis. Severely damaged mitochondria can be the target of an autophagic degradation mechanism termed mitophagy (Logan, 2010; Westermann, 2010; Chan, 2012; Otera et al., 2013; Friedman and Nunnari, 2014). The functions and dynamics of mitochondria are linked to evolutionarily conserved proteins localized to the mitochondrial outer membrane. For example, voltage-gated anion channels (VDAC) regulate the flow of metabolites, including ATP and ADP, across the outer membrane (Lemasters and Holmuhamedov, 2006; Colombini, 2012). The translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex is the main pathway for mitochondrial protein transport, while the topogenesis of mitochondrial outer membrane β-barrel (TOB)/sorting and assembly machinery (SAM) complex plays an important role in the assembly of outer membrane proteins (Pfanner et al., 2004; Neupert and Herrmann, 2007; Endo and Yamano, 2010). Dynamin-related GTPases are recruited to the outer membrane and form a ring-like oligomer that constricts mitochondria, leading to fission (Kuroiwa et al., 2006; Bui and Shaw, 2013; Chappie and Dyda, 2013).

The Miro protein is a mitochondrial outer membrane-localized GTPase that is highly conserved throughout eukaryotes. In metazoans, Miro is a component of the protein complex that regulates mitochondrial transport. However, accumulating evidence from studies of non-metazoans, including plants, suggests that Miro is involved in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis. Here, we review the studies investigating Miro GTPases in diverse eukaryotes and reconsider the molecular functions and physiological roles of Miro in the light of eukaryotic evolution.

MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF Miro GTPases

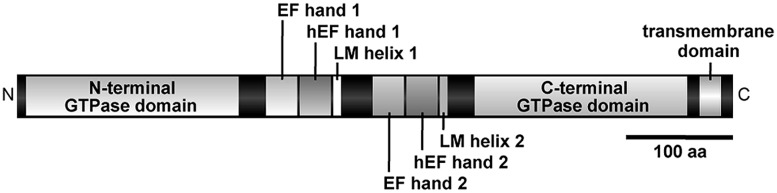

Miro GTPase is anchored to the mitochondrial outer membrane by its C-terminal transmembrane domain, leaving its N-terminus exposed to the cytoplasm. Its cytoplasmic region contains two structurally distinct GTPase domains that are separated by a pair of EF hand motifs (EF hands 1 and 2; Fransson et al., 2003, 2006; Frederick et al., 2004; Guo et al., 2005; Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008; Vlahou et al., 2011; Figure 1). Miro was originally classified as an atypical Rho GTPase based on sequence similarity of the N-terminal GTPase domain to Rho family proteins (Fransson et al., 2003). However, later studies found that both GTP domains lack the conserved G-3 DxxG motif (Bourne et al., 1991) and the Rho-specific insert region (Freeman et al., 1996; Walker and Brown, 2002), suggesting that they represent two independent subfamilies of the Ras GTPase superfamily (Frederick et al., 2004; Wennerberg and Der, 2004; Boureux et al., 2007; Reis et al., 2009). A recent study of Miro in fruit flies showed that its C-terminal GTPase domain is most structurally similar to Rheb, a Ras subfamily member (Mazhab-Jafari et al., 2012; Klosowiak et al., 2013). Correspondingly, the catalytic rates of the two GTPase domains of the budding yeast Miro homolog Gem1p are comparable to those of the Ras family and are significantly slower than those of the dynamin family (Koshiba et al., 2011). The two conserved EF hands of Miro have been shown to bind Ca2+ (MacAskill et al., 2009; Koshiba et al., 2011) and the flanking regions of the EF hands are highly conserved among eukaryotes (Vlahou et al., 2011). Klosowiak et al. (2013) showed that these regions contain non-canonical “hidden” EF hands (hEF hands 1 and 2) followed by single helices (LM helices 1 and 2; Figure 1). The hEF hands have a typical helix–loop–helix structure and stabilize the adjacent EF hands by forming an anti-parallel EF hand β-scaffold. The structure of the Miro LM helices resembles extrinsic ligands bound to EF hand proteins, as reported for the protein complexes of Troponin I and Troponin C (Vinogradova et al., 2005) and molluscan myosin heavy chain and light chain (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996; Klosowiak et al., 2013). The EF–hEF hand pair combined with the LM helix can be found in various Ca2+-binding proteins including the pollen protein polcalcin (Neudecker et al., 2004), the retinal protein recoverin (Tanaka et al., 1995; Ames et al., 2006), and human guanylate cyclase-activating protein GCAP3 (Stephen et al., 2006). Miro is a monomeric protein that assumes a compact and linear conformation in solution and undergoes no significant conformational rearrangement into another stable form and/or oligomerization in response to ions or nucleotides (Klosowiak et al., 2013). Conformational changes of Miro may require an interacting partner, similar to other EF hand proteins (Grabarek, 2006; Klosowiak et al., 2013).

FIGURE 1.

Molecular structure of the Miro GTPase. Schematic representation of the molecular structure of Miro according to Klosowiak et al. (2013). Domain names are described in the text. The bar indicates a length corresponding to 100 amino acid residues.

Miro GTPases EMERGED BEFORE THE DIVERGENCE OF EUKARYOTES

An extensive phylogenetic analysis by Vlahou et al. (2011) showed that at least one Miro homolog is present in almost all eukaryotic genomes. The phylogeny of Miro homologs shows a clear correlation with that of eukaryotic species and no obvious homolog can be found in prokaryotes. This suggests that Miro appeared at an early stage of eukaryotic evolution, perhaps before the divergence of extant eukaryotic species (Vlahou et al., 2011); however, the exceptions are found in several species. First, Miro is absent from eukaryotic species that possess mitosomes and hydrogenosomes instead of canonical aerobic mitochondria, including the phylum Microsporidia and the genus Entamoeba. Second, the genomes of several species possessing aerobic mitochondria, such as the phylum Apicomplexa and the order Mamiellales, lack Miro. Third, Miro homologs in the order Trypanosomatid have a non-functional version of EF hand 2 and lack the N-terminal GTPase domain, possessing instead a novel domain without similarity to any other defined sequences. Fourth, in the class Oligohymenophorea, the C-terminal Miro GTPase domains are replaced by sequences that are not conserved, even within the class. Fifth, Miro homologs from Amoebozoa and Stramenopiles have a non-functional C-terminal GTPase domain that lacks the conserved residues. These variations are found separately in different eukaryotic lineages, suggesting that the molecular structure of Miro was modified independently to meet the functional demands of the protein in each lineage after the divergence of eukaryotes (Vlahou et al., 2011).

METAZOAN Miro GTPases

Miro IS A Ca2+-DEPENDENT REGULATOR OF MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSPORT IN METAZOANS

Mitochondrial transport is essential for neuronal energy supply to the axons and for the transmission of signals from the cell body to the synaptic junctions. Disruption of mitochondrial distribution in neurons is deleterious and is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including dominant optic atrophy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases (Chen and Chan, 2009; Harris et al., 2012; Saxton and Hollenbeck, 2012). In axons, mitochondria are transported along microtubules by the action of kinesins and dyneins as anterograde and retrograde motors, respectively. A screening of genetically mosaic mutant fruit flies identified allelic lethal mutations of Miro that cause abnormal larval locomotion and premature lethality. In the mutant neurons, mitochondria are abnormally clustered in the cell body and are often absent from the synaptic terminals, suggesting a requirement for Miro in anterograde mitochondrial transport along axons (Guo et al., 2005). Subsequent studies showed that Miro forms a protein complex with the kinesin-associated protein Milton (Stowers et al., 2002), which recruits kinesins to mitochondria for anterograde transport (Glater et al., 2006). Two mammalian Milton homologs, GRIF-1 (also known as OIP98, huMilt2, or TRAK2) and OIP106 (also known as huMilt1 or TRAK1; Beck et al., 2002; Stowers et al., 2002; Iyer et al., 2003; Brickley et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2006), associate with Miro, suggesting that Miro is a component of a conserved protein complex involved in mitochondrial transport (Fransson et al., 2006; Wang and Schwarz, 2009; Weihofen et al., 2009). Mitochondrial transport is dependent on cytosolic Ca2+ (Rintoul et al., 2003; Yi et al., 2004), and a role for Miro in its regulation has been demonstrated (Saotome et al., 2008; MacAskill et al., 2009; Wang and Schwarz, 2009; Chang et al., 2011). However, several different models for the underlying mechanism have been proposed. Wang and Schwarz (2009) proposed that Miro interacts with kinesin via Milton independently of Ca2+. In this model, increased cytosolic Ca2+ causes the N-terminal kinesin motor domain to dissociate from microtubules and interact with Miro, resulting in the arrest of mitochondrial transport (Wang and Schwarz, 2009). MacAskill et al. (2009) proposed an alternative model by which Miro directly associates with kinesin without the aid of Milton. In this model, an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ inhibits the association and allows Miro to be released from kinesin (MacAskill et al., 2009). Accumulating evidence suggests that Miro is also involved in the regulation of retrograde mitochondrial transport (Russo et al., 2009; Wang and Schwarz, 2009; Misko et al., 2010; Morlino et al., 2014).

Several neuron-specific proteins that modify the function of Miro in mitochondrial transport were identified recently. Syntaphilin associates with the kinesin that is released from Ca2+-binding Miro, leading to stationary mitochondrial docking through interaction with microtubules in axons (Chen and Sheng, 2013). The hypoxia-inducible protein HUMMR interacts with Miro and the mammalian Milton homologs, and biases axonal transport of mitochondria in the anterograde direction, presumably for the maintenance of neuronal functions and survival during hypoxia (Li et al., 2009). Alex3, another protein associated with Miro-mediated mitochondrial transport machinery in neurons, is unique to Eutherian mammals. Alex3 originated through a Eutherian-specific gene duplication and may be linked to the increase in brain complexity in Eutherians (López-Doménech et al., 2012).

Miro IS A TARGET OF PARKIN-MEDIATED DEGRADATION IN MAMMALIAN CELLS

Recent evidence suggests that Miro-mediated mitochondrial transport is associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD), a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor disturbances. A form of autosomal recessive juvenile PD is caused by mutations in the mitochondria-targeted Ser/Thr kinase PINK1 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin. PINK1 and Parkin operate together in a common pathway involved in the regulation of multiple aspects of mitochondrial quality control, including mitochondrial biogenesis, fusion and fission, transport, and mitophagy (Chen and Chan, 2009; Scarffe et al., 2014). PINK1 and Parkin are recruited to the damaged mitochondrial outer membrane, where they phosphorylate and ubiquitinate various proteins including VDACs and the mitochondrial fusion proteins mitofusins (Geisler et al., 2010; Ziviani et al., 2010; Chen and Dorn, 2013). Recent studies showed that Miro is also a target of the PINK1-Parkin pathway, although its ubiquitination pattern remains unclear (Weihofen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Sarraf et al., 2013; Birsa et al., 2014). The Parkin-mediated proteasomal degradation of Miro leads to the dissociation of kinesin from mitochondria and the subsequent arrest of mitochondrial transport. These events may quarantine the damaged mitochondria to facilitate mitophagic clearance (Wang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Birsa et al., 2014).

Miro IS INVOLVED IN MITOCHONDRIAL MORPHOLOGY AND Ca2+ HOMEOSTASIS IN METAZOANS

Several studies suggest that metazoan Miro plays different roles in mitochondrial dynamics and function other than mitochondrial transport. Overexpression of Miro and its mutant proteins influences mitochondrial morphology (Fransson et al., 2003, 2006; Glater et al., 2006; Saotome et al., 2008; Weihofen et al., 2009). Overexpression experiments showed that Miro and Drp1, a dynamin GTPase associated with mitochondrial fission, function in an antagonistic manner in mitochondrial morphology, suggesting that Miro may play a role in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology by suppressing Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission (Saotome et al., 2008). Miro is also likely to be involved in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis. Chang et al. (2011) showed that mitochondrial Ca2+ content is negatively correlated with the velocity of mitochondrial transport. Overexpression of a non-functional EF hand mutant version of Miro decreased Ca2+ entry into mitochondria, suggesting that Miro is primarily involved in the regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx and homeostasis, which, in turn, influences mitochondrial transport (Chang et al., 2011; Niescier et al., 2013).

NON-METAZOAN Miro GTPases

Miro IS INVOLVED IN THE MAINTENANCE OF MITOCHONDRIAL MORPHOLOGY AND INHERITANCE IN Saccharomyces cerevisiae

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the single-copy Miro homolog Gem1p plays a role in mitochondrial morphology and inheritance. The mitochondrial compartment in wild-type yeast is characterized by a branched network of tubular structures at the cell cortex (Koning et al., 1993; Frederick et al., 2004). In the gem1 knockout mutant, mitochondria show a globular, collapsed tubular, or grape-like morphology without an obvious impact on the mitochondrial membrane structures, suggesting that Gem1p is required for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology. Amino acid substitution experiments suggest that the function of Gem1p in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology requires both the GTPase domains and the EF hands (Frederick et al., 2004). The gem1 knockout mutant also shows impaired cell growth on synthetic glycerol media, implying that Gem1p is required for proper mitochondrial respiration (Frederick et al., 2004). Genetic analysis showed that the GEM1 pathway is independent from the known mitochondrial morphology pathways, including those related to mitochondrial fusion and fission (Frederick et al., 2004). Further analyses suggested that Gem1p is involved in a pathway that influences mitochondrial inheritance and is independent of other pathways mediated by the myosin-interacting proteins Mmr1p and Ypt11p (Frederick et al., 2004, 2008).

Miro PLAYS A ROLE IN MITOCHONDRIA–ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM INTERACTION

Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) physically interact with one another and play roles in various cellular processes, including phospholipid biosynthesis and mitochondrial fission (Rowland and Voeltz, 2012; Friedman and Nunnari, 2014; Vance, 2014). Kornmann et al. (2009) showed that loss of MDM12, a subunit of the ER–mitochondria encounter structure complex (ERMES) that is essential for various mitochondrial functions (Boldogh et al., 2003; Youngman et al., 2004; Meisinger et al., 2007), can be rescued by an artificial tethering of mitochondria and the ER. ERMES localizes to mitochondria–ER contact sites and is visualized as punctate structures, suggesting its critical role in mitochondria–ER interactions (Kornmann et al., 2009). Gem1p interacts with ERMES; however, this interaction is not required for the assembly of the ERMES complex (Kornmann et al., 2011; Stroud et al., 2011). Imaging analysis suggests that Gem1p negatively regulates ER-associated mitochondrial fission (Murley et al., 2013). Studies suggest that the mitochondria–ER interaction mediates the exchange of phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) between the two organelles, allowing phosphatidylcholine (PC) biosynthesis (Rowland and Voeltz, 2012; Vance, 2014). Disruption of ERMES impairs the conversion of PS to PC, and knockout of gem1 has deleterious effects in mutants defective in PS synthesis, suggesting that Gem1p plays a role in lipid exchange through the activity of ERMES (Kornmann et al., 2009, 2011). However, several discrepancies remain to be clarified (Nguyen et al., 2012; Vance, 2014).

Miro IS INVOLVED IN MITOCHONDRIAL HOMEOSTASIS IN Dictyostelium discoideum

The slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum has a single copy of the gemA gene, which encodes a Miro homolog. The gemA knockout mutants show impaired cell growth on nutrient media without any obvious defects in cell division, implying that GemA is involved in mitochondrial function (Vlahou et al., 2011). In D. discoideum, mitochondrial transport is primarily mediated by microtubules (Fields et al., 2002; Vlahou et al., 2011). The gemA mutants show no obvious phenotype with respect to mitochondrial size, morphology, or intracellular distribution. Co-immunoprecipitation assays suggest that GemA does not associate with the Dictyostelium kinesin Kif5. These findings indicate that Miro does not play a role in microtubule-dependent mitochondrial transport in D. discoideum (Vlahou et al., 2011). However, the absence of gemA compromises multiple aspects of mitochondrial function including total mitochondrial mass, ATP accumulation, and oxygen consumption, but does not influence glucose consumption, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, or mitochondrial membrane potential. This suggests that the primary role of Miro in D. discoideum is the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis rather than mitochondrial transport (Vlahou et al., 2011).

Miro INFLUENCES MITOCHONDRIAL MORPHOLOGY IN Arabidopsis thaliana

Plant mitochondria are uniformly spherical and undergo frequent fusion and fission and actin-dependent transport. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains three Miro homologs, namely, MIRO1 (At5g27540), MIRO2 (At3g63150), and MIRO3 (At3g05310). MIRO1 and MIRO2 are expressed throughout the plant (Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008), whereas MIRO3 is expressed specifically in the endosperm (Winter et al., 2007; Bassel et al., 2008; Day et al., 2008). Insertional mutation of the MIRO1 gene has multiple effects on plant growth and development including impairment of pollen tube growth and embryonic lethality at an early stage (Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008; Sørmo et al., 2011). Mutation of the MIRO2 gene enhances the miro1 mutant phenotype and includes defects in female gametogenesis associated with delayed polar nuclear fusion (Sørmo et al., 2011). Imaging analyses showed abnormally enlarged mitochondria in the miro1 mutant, although their inner membrane structures were likely to be normal (Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008). The miro1 mutation also influences mitochondrial inheritance during cell division at an early stage of embryogenesis (Yamaoka et al., 2011); however, the mutant mitochondria undergo continuous cytoplasmic streaming in an actin-dependent manner. In addition, an obvious Milton homolog is absent from the Arabidopsis genome. These findings suggest that the primary role of Arabidopsis Miro is in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology rather than actin-dependent mitochondrial transport (Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008; Yamaoka et al., 2011).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that, in metazoans, Miro is primarily involved in the Ca2+-dependent regulation of mitochondrial transport; however, in non-metazoans, Miro plays a primary role in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis (Table 1). The molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial transport differ between eukaryotic lineages. In metazoans, microtubule-dependent mitochondrial transport is well defined, whereas in budding yeast, mitochondrial transport and inheritance are mediated by multiple myosin-dependent and -independent pathways (Boldogh and Pon, 2007; Frederick and Shaw, 2007; Frederick et al., 2008; Förtsch et al., 2011). Plants use actin filaments and myosins for mitochondrial transport (Avisar et al., 2008; Peremyslov et al., 2008; Prokhnevsky et al., 2008; Sparkes et al., 2008; Avisar et al., 2009), although the molecular interactions linking mitochondria and myosins remain elusive. These differences suggest that each of the eukaryotic lineages independently developed their own mitochondrial transport machinery after divergence from the ancestral eukaryotic cell. In contrast, Miro is present in almost all eukaryotes, and the phylogeny of Miro homologs and eukaryotic lineages correspond well, suggesting that Miro emerged before the divergence of eukaryotes. Therefore, it is possible that Miro has a common ancestral function in every eukaryote that is related to the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis, while it acquired a role in the regulation of mitochondrial transport specifically in metazoans. The presence of cell-type-specific and lineage-specific Miro-interacting partners (Table 1) implies that the molecular nature of Miro promotes its physical interaction with multiple types of proteins. Identification of Mito-interacting partners in non-metazoans will provide further insights into the functions of Miro and the evolution of mitochondrial functions and dynamics.

Table 1.

Molecular function and interacting proteins of Miro GTPase from various eukaryotes.

| Gene names | Mitochondrial functions | Interacting proteins | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metazoans | Mammals | Miro-1, Miro-21 (humans) | Microtubule-dependent transport6-20 | GRIF-1/OIP98/huMilt2/TRAK26,9 |

| OIP106/huMilt1/TRAK16,14 | ||||

| Kinesin9 | ||||

| Dynein20 | ||||

| PINK114-17 | ||||

| Parkin15-17 | ||||

| Mitofusin219 | ||||

| HUMMR (neuron-specific)12 | ||||

| Alex3 (Eutherian neuron-specific)13 | ||||

| Morphology1,6,7,14,21 | – | |||

| Ca2+ homeostasis18 | – | |||

| Mitochondria-ER interaction22 | – | |||

| Drosophila melanogaster | dMiro2/Miro21 | Microtubule-dependent transport2,21 | Milton8,21 | |

| Non-metazoans | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | GEM13 | Morphology3,22,23,26 | – |

| Inheritance3,23 | – | |||

| Mitochondria-ER interaction22,24,25,26 | Mdm34p22,25 | |||

| Mmm1p22,25 | ||||

| Mdm10p25 | ||||

| Mdm12p25 | ||||

| Dictyostelium discoideum | gemA4 | Homeostasis4 | – | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | MIRO1, MIRO2, MIRO35 | Morphology5,27 | – | |

| Inheritance27 | – | |||

Summary table showing gene names, mitochondrial functions, and interacting proteins of Miro from mammals, fruit fly (D. melanogaster), budding yeast (S. cerevisiae), slime mold (D. discoideum), and plant (A. thaliana). Superscript numbers correspond to the following references: (1) Fransson et al. (2003); (2) Guo et al. (2005); (3) Frederick et al. (2004); (4) Vlahou et al. (2011); (5) Yamaoka and Leaver (2008); (6) Fransson et al. (2006); (7) Saotome et al. (2008); (8) Wang and Schwarz (2009); (9) MacAskill et al. (2009); (10) Russo et al. (2009); (11) Chen and Sheng (2013); (12) Li et al. (2009); (13) López-Doménech et al. (2012); (14) Weihofen et al. (2009); (15) Wang et al. (2011); (16) Liu et al. (2012); (17) Birsa et al. (2014); (18) Chang et al. (2011); (19) Misko et al. (2010); (20) Morlino et al. (2014); (21) Glater et al. (2006); (22) Kornmann et al. (2011); (23) Frederick et al. (2008); (24) Kornmann et al. (2009); (25) Stroud et al. (2011); (26) Murley et al. (2013); (27) Yamaoka et al. (2011).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research to Shohei Yamaoka (no. 25840108 and 25120715) and a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research to Ikuko Hara-Nishimura (no. 22000014) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- Ames J. B., Levay K., Wingard J. N., Lusin J. D., Slepak V. Z. (2006). Structural basis for calcium-induced inhibition of rhodopsin kinase by recoverin. J. Biol. Chem. 281 37237–37245 10.1074/jbc.M606913200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avisar D., Abu-Abied M., Belausov E., Sadot E., Hawes C., Sparkes I. A. (2009). A comparative study of the involvement of 17 Arabidopsis myosin family members on the motility of Golgi and other organelles. Plant Physiol. 150 700–709 10.1104/pp.109.136853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avisar D., Prokhnevsky A. I., Makarova K. S., Koonin E. V., Dolja V. V. (2008). Myosin XI-K is required for rapid trafficking of Golgi stacks, peroxisomes, and mitochondria in leaf cells of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Physiol. 146 1098–1108 10.1104/pp.107.113647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassel G. W., Fung P., Chow T. F., Foong J. A., Provart N. J., Cutler S. R. (2008). Elucidating the germination transcriptional program using small molecules. Plant Physiol. 147 143–155 10.1104/pp.107.110841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M., Brickley K., Wilkinson H. L., Sharma S., Smith M., Chazot P. L., et al. (2002). Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of a novel GABAA receptor-associated protein, GRIF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277 30079–30090 10.1074/jbc.M200438200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsa N., Norkett R., Wauer T., Mevissen T. E., Wu H. C., Foltynie T., et al. (2014). K27 ubiquitination of the mitochondrial transport protein Miro is dependent on serine 65 of the Parkin ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M114.563031 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldogh I. R., Nowakowski D. W., Yang H. C., Chung H., Karmon S., Royes P., et al. (2003). A protein complex containing Mdm10p, Mdm12p, and Mmm1p links mitochondrial membranes and DNA to the cytoskeleton-based segregation machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 14 4618–4627 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldogh I. R., Pon L. A. (2007). Mitochondria on the move. Trends Cell Biol. 17 502–510 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boureux A., Vignal E., Faure S., Fort P. (2007). Evolution of the Rho family of ras-like GTPases in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 203–216 10.1093/molbev/msl145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne H. R., Sanders D. A., McCormick F. (1991). The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 349 117–127 10.1038/349117a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley K., Smith M. J., Beck M., Stephenson F. A. (2005). GRIF-1 and OIP106 members of a novel gene family of coiled-coil domain proteins: association in vivo and in vitro with kinesin. J. Biol. Chem. 280 14723–14732 10.1074/jbc.M409095200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui H. T., Shaw J. M. (2013). Dynamin assembly strategies and adaptor proteins in mitochondrial fission. Curr. Biol. 23 R891–R899 10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. C. (2012). Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46 265–287 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K. T., Niescier R. F., Min K.-T. (2011). Mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ as an intrinsic signal regulating mitochondrial motility in axons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 15456–15461 10.1073/pnas.1106862108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappie J. S., Dyda F. (2013). Building a fission machine – structural insights into dynamin assembly and activation. J. Cell Sci. 126 2773–2784 10.1242/jcs.108845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Chan D. C. (2009). Mitochondrial dynamics – fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy – in neurodegenerative diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 R169–R176 10.1093/hmg/ddp326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Dorn G. W. , II. (2013). PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 340 471–475 10.1126/science.1231031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Sheng Z. H. (2013). Kinesin-1-syntaphilin coupling mediates activity-dependent regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport. J. Cell Biol. 202 351–364 10.1083/jcb.201302040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombini M. (2012). VDAC structure, selectivity, and dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818 1457–1465 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day R. C., Herridge R. P., Ambrose B. A., Macknight R. C. (2008). Transcriptome analysis of proliferating Arabidopsis endosperm reveals biological implications for the control of syncytial division, cytokinin signaling, and gene expression regulation. Plant Physiol. 148 1964–1984 10.1104/pp.108.128108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Yamano K. (2010). Transport of proteins across or into the mitochondrial outer membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803 706–714 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S. D., Arana Q., Heuser J., Clarke M. (2002). Mitochondrial membrane dynamics are altered in cluA- mutants of Dictyostelium. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 23 829–838 10.1023/A:1024492031696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förtsch J., Hummel E., Krist M., Westermann B. (2011). The myosin-related motor protein Myo2 is an essential mediator of bud-directed mitochondrial movement in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 194 473–488 10.1083/jcb.201012088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson A., Ruusala A., Aspenström P. (2003). Atypical Rho GTPases have roles in mitochondrial homeostasis and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278 6495–6502 10.1074/jbc.M208609200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson S., Ruusala A., Aspenström P. (2006). The atypical Rho GTPases Miro-1 and Miro-2 have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344 500–510 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick R. L., McCaffery J. M., Cunningham K. W., Okamoto K., Shaw J. M. (2004). Yeast Miro GTPase, Gem1p, regulates mitochondrial morphology via a novel pathway. J. Cell Biol. 167 87–98 10.1083/jcb.200405100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick R. L., Okamoto K., Shaw J. M. (2008). Multiple pathways influence mitochondrial inheritance in budding yeast. Genetics 178 825–837 10.1534/genetics.107.083055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick R. L., Shaw J. M. (2007). Moving mitochondria: establishing distribution of an essential organelle. Traffic 8 1668–1675 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00644.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J. L., Abo A., Lambeth J. D. (1996). Rac “insert region” is a novel effector region that is implicated in the activation of NADPH oxidase, but not PAK65. J. Biol. Chem. 271 19794–19801 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J. R., Nunnari J. (2014). Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 505 335–343 10.1038/nature12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S., Holmström K. M., Skujat D., Fiesel F. C., Rothfuss O. C., Kahle P. J., et al. (2010). PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat. Cell Biol. 12 119–131 10.1038/ncb2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glater E. E., Megeath L. J., Stowers R. S., Schwarz T. L. (2006). Axonal transport of mitochondria requires milton to recruit kinesin heavy chain and is light chain independent. J. Cell Biol. 173 545–557 10.1083/jcb.200601067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek Z. (2006). Structural basis for diversity of the EF-hand calcium-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 359 509–525 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Macleod G. T., Wellington A., Hu F., Panchumarthi S., Schoenfield M., et al. (2005). The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron 47 379–393 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. J., Jolivet R., Attwell D. (2012). Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron 75 762–777 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse A., Cohen C. (1996). Structure of the regulatory domain of scallop myosin at 2 Å resolution: implications for regulation. Structure 4 21–32 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S. P., Akimoto Y., Hart G. W. (2003). Identification and cloning of a novel family of coiled-coil domain proteins that interact with O-GlcNAc transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 278 5399–5409 10.1074/jbc.M209384200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosowiak J. L., Focia P. J., Chakravarthy S., Landahl E. C., Freymann D. M., Rice S. E. (2013). Structural coupling of the EF hand and C-terminal GTPase domains in the mitochondrial protein Miro. EMBO Rep. 14 968–974 10.1038/embor.2013.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning A. J., Lum P. Y., Williams J. M., Wright R. (1993). DiOC6 staining reveals organelle structure and dynamics in living yeast cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 25 111–128 10.1002/cm.970250202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmann B., Currie E., Collins S. R., Schuldiner M., Nunnari J., Weissman J. S., et al. (2009). An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science 325 477–481 10.1126/science.1175088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmann B., Osman C., Walter P. (2011). The conserved GTPase Gem1 regulates endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 14151–14156 10.1073/pnas.1111314108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T., Holman H. A., Kubara K., Yasukawa K., Kawabata S., Okamoto K., et al. (2011). Structure-function analysis of the yeast mitochondrial Rho GTPase, Gem1p: implications for mitochondrial inheritance. J. Biol. Chem. 286 354–362 10.1074/jbc.M110.180034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa T., Nishida K., Yoshida Y., Fujiwara T., Mori T., Kuroiwa H., et al. (2006). Structure, function and evolution of the mitochondrial division apparatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763 510–521 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters J. J., Holmuhamedov E. (2006). Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) as mitochondrial governator – thinking outside the box. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1762 181–190 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lim S., Hoffman D., Aspenstrom P., Federoff H. J., Rempe D. A. (2009). HUMMR, a hypoxia- and HIF-1α-inducible protein, alters mitochondrial distribution and transport. J. Cell Biol. 185 1065–1081 10.1083/jcb.200811033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Sawada T., Lee S., Yu W., Silverio G., Alapatt P., et al. (2012). Parkinson’s disease-associated kinase PINK1 regulates Miro protein level and axonal transport of mitochondria. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002537 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan D. C. (2010). Mitochondrial fusion, division and positioning in plants. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38 789–795 10.1042/BST0380789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Doménech G., Serrat R., Mirra S., D’Aniello S., Somorjai I., Abad A., et al. (2012). The Eutherian Armcx genes regulate mitochondrial trafficking in neurons and interact with Miro and Trak2. Nat. Commun. 3 814 10.1038/ncomms1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAskill A. F., Rinholm J. E., Twelvetrees A. E., Arancibia-Carcamo I. L., Muir J., Fransson A., et al. (2009). Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron 61 541–555 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhab-Jafari M. T., Marshall C. B., Ishiyama N., Ho J., Di Palma V., Stambolic V., et al. (2012). An autoinhibited noncanonical mechanism of GTP hydrolysis by Rheb maintains mTORC1 homeostasis. Structure 20 1528–1539 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisinger C., Pfannschmidt S., Rissler M., Milenkovic D., Becker T., Stojanovski D., et al. (2007). The morphology proteins Mdm12/Mmm1 function in the major β-barrel assembly pathway of mitochondria. EMBO J. 26 2229–2239 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misko A., Jiang S., Wegorzewska I., Milbrandt J., Baloh R. H. (2010). Mitofusin 2 is necessary for transport of axonal mitochondria and interacts with the Miro/Milton complex. J. Neurosci. 30 4232–4240 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6248-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlino G., Barreiro O., Baixauli F., Robles-Valero J., González-Granado J. M., Villa-Bellosta R., et al. (2014). Miro-1 links mitochondria and microtubule Dynein motors to control lymphocyte migration and polarity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34 1412–1426 10.1128/MCB.01177-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murley A., Lackner L. L., Osman C., West M., Voeltz G. K., Walter P., et al. (2013). ER-associated mitochondrial division links the distribution of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in yeast. Elife 2 e00422. 10.7554/eLife.00422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neudecker P., Nerkamp J., Eisenmann A., Nourse A., Lauber T., Schweimer K., et al. (2004). Solution structure, dynamics, and hydrodynamics of the calcium-bound cross-reactive birch pollen allergen Bet v 4 reveal a canonical monomeric two EF-hand assembly with a regulatory function. J. Mol. Biol. 336 1141–1157 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert W., Herrmann J. M. (2007). Translocation of proteins into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76 723–749 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.163409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T., Lewandowska A., Choi J. Y., Markgraf D. F., Junker M., Bilgin M., et al. (2012). Gem1 and ERMES do not directly affect phosphatidylserine transport from ER to mitochondria or mitochondrial inheritance. Traffic 13 880–890 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01352.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niescier R. F., Chang K. T., Min K.-T. (2013). Miro, MCU, and calcium: bridging our understanding of mitochondrial movement in axons. Front. Cell Neurosci. 7:148 10.3389/fncel.2013.00148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otera H., Ishihara N., Mihara K. (2013). New insights into the function and regulation of mitochondrial fission. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833 1256–1268 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peremyslov V. V., Prokhnevsky A. I., Avisar D., Dolja V. V. (2008). Two class XI myosins function in organelle trafficking and root hair development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 146 1109–1116 10.1104/pp.107.113654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N., Wiedemann N., Meisinger C., Lithgow T. (2004). Assembling the mitochondrial outer membrane. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 1044–1048 10.1038/nsmb852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhnevsky A. I., Peremyslov V. V., Dolja V. V. (2008). Overlapping functions of the four class XI myosins in Arabidopsis growth, root hair elongation, and organelle motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 19744–19749 10.1073/pnas.0810730105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis K., Fransson A., Aspenström P. (2009). The Miro GTPases: at the heart of the mitochondrial transport machinery. FEBS Lett. 583 1391–1398 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintoul G. L., Filiano A. J., Brocard J. B., Kress G. J., Reynolds I. J. (2003). Glutamate decreases mitochondrial size and movement in primary forebrain neurons. J. Neurosci. 23 7881–7888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A. A., Voeltz G. K. (2012). Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13 607–625 10.1038/nrm3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo G. J., Louie K., Wellington A., Macleod G. T., Hu F., Panchumarthi S., et al. (2009). Drosophila Miro is required for both anterograde and retrograde axonal mitochondrial transport. J. Neurosci. 29 5443–5455 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saotome M., Safiulina D., Szabadkai G., Das S., Fransson A., Aspenstrom P., et al. (2008). Bidirectional Ca2+-dependent control of mitochondrial dynamics by the Miro GTPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 20728–20733 10.1073/pnas.0808953105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarraf S. A., Raman M., Guarani-Pereira V., Sowa M. E., Huttlin E. L., Gygi S. P., et al. (2013). Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature 496 372–376 10.1038/nature12043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton W. M., Hollenbeck P. J. (2012). The axonal transport of mitochondria. J. Cell Sci. 125 2095–2104 10.1242/jcs.053850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarffe L. A., Stevens D. A., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2014). Parkin and PINK1: much more than mitophagy. Trends Neurosci. 37 315–324 10.1016/j.tins.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J., Pozo K., Brickley K., Stephenson F. A. (2006). Mapping the GRIF-1 binding domain of the kinesin, KIF5C, substantiates a role for GRIF-1 as an adaptor protein in the anterograde trafficking of cargoes. J. Biol. Chem. 281 27216–27228 10.1074/jbc.M600522200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørmo C. G., Brembu T., Winge P., Bones A. M. (2011). Arabidopsis thaliana MIRO1 and MIRO2 GTPases are unequally redundant in pollen tube growth and fusion of polar nuclei during female gametogenesis. PLoS ONE 6:e18530 10.1371/journal.pone.0018530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes I. A., Teanby N. A., Hawes C. (2008). Truncated myosin XI tail fusions inhibit peroxisome, Golgi, and mitochondrial movement in tobacco leaf epidermal cells: a genetic tool for the next generation. J. Exp. Bot. 59 2499–2512 10.1093/jxb/ern114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen R., Palczewski K., Sousa M. C. (2006). The crystal structure of GCAP3 suggests molecular mechanism of GCAP-linked cone dystrophies. J. Mol. Biol. 359 266–275 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers R. S., Megeath L. J., Gorska-Andrzejak J., Meinertzhagen I. A., Schwarz T. L. (2002). Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron 36 1063–1077 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01094-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud D. A., Oeljeklaus S., Wiese S., Bohnert M., Lewandrowski U., Sickmann A., et al. (2011). Composition and topology of the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria encounter structure. J. Mol. Biol. 413 743–750 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Ames J. B., Harvey T. S., Stryer L., Ikura M. (1995). Sequestration of the membrane-targeting myristoyl group of recoverin in the calcium-free state. Nature 376 444–447 10.1038/376444a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance J. E. (2014). MAM (mitochondria-associated membranes) in mammalian cells: Lipids and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841 595–609 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova M. V., Stone D. B., Malanina G. G., Karatzaferi C., Cooke R., Mendelson R. A., et al. (2005). Ca2+-regulated structural changes in troponin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 5038–5043 10.1073/pnas.0408882102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahou G., Eliáš M., von Kleist-Retzow J. C., Wiesner R. J., Rivero F. (2011). The Ras related GTPase Miro is not required for mitochondrial transport in Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90 342–355 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. J., Brown H. A. (2002). Specificity of Rho insert-mediated activation of phospholipase D1. J. Biol. Chem. 277 26260–26267 10.1074/jbc.M201811200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Schwarz T. L. (2009). The mechanism of Ca2+-dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell 136 163–174 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Winter D., Ashrafi G., Schlehe J., Wong Y. L., Selkoe D., et al. (2011). PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell 147 893–906 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihofen A., Thomas K. J., Ostaszewski B. L., Cookson M. R., Selkoe D. J. (2009). Pink1 forms a multiprotein complex with Miro and Milton, linking Pink1 function to mitochondrial trafficking. Biochemistry 48 2045–2052 10.1021/bi8019178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg K., Der C. J. (2004). Rho-family GTPases: it’s not only Rac and Rho (and I like it). J. Cell Sci. 117 1301–1312 10.1242/jcs.01118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann B. (2010). Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 872–884 10.1038/nrm3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D., Vinegar B., Nahal H., Ammar R., Wilson G. V., Provart N. J. (2007). An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS ONE 2:e718 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka S., Leaver C. J. (2008). EMB2473/MIRO1 an Arabidopsis Miro GTPase, is required for embryogenesis and influences mitochondrial morphology in pollen. Plant Cell 20 589–601 10.1105/tpc.107.055756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka S., Nakajima M., Fujimoto M., Tsutsumi N. (2011). MIRO1 influences the morphology and intracellular distribution of mitochondria during embryonic cell division in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 30 239–244 10.1007/s00299-010-0926-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi M., Weaver D., Hajnóczky G. (2004). Control of mitochondrial motility and distribution by the calcium signal: a homeostatic circuit. J. Cell Biol. 167 661–672 10.1083/jcb.200406038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngman M. J., Hobbs A. E., Burgess S. M., Srinivasan M., Jensen R. E. (2004). Mmm2p, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein required for yeast mitochondrial shape and maintenance of mtDNA nucleoids. J. Cell Biol. 164 677–688 10.1083/jcb.200308012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziviani E., Tao R. N., Whitworth A. J. (2010). Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 5018–5023 10.1073/pnas.0913485107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]