Abstract

In many developing countries including those of sub-Saharan Africa care of the critically ill is poorly developed. We therefore sought to elucidate the characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients to better define the burden of disease and identify strategies for improving care. We conducted a cross sectional observation study of patients admitted to the intensive care unit at Kamuzu Central Hospital in 2010. Demographic, patient characteristics, clinical specialty and outcome data was collected. There were 234 patients admitted during the study period. Older age and admission from trauma, general surgery or medical services were associated with increased mortality. The lowest mortality was among obstetrical and gynecologic patients. Use of the ventilator and transfusions were not associated with increased mortality. Head injured patients had the highest mortality rate among all diagnoses. Rationing of critical care resources using admitting diagnosis or scoring tools can maximize access to critical care services in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, improvements on critical care services will be central to future efforts at reducing surgical morbidity and mortality and improving outcomes in all critically ill patients.

Keywords: Surgical Diseases, Critical care, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

In many developing countries, including those of sub-Saharan Africa, care of the critically ill is poorly developed1 and as such, care is viewed as complex and unaffordable for many developing countries. Critical care, however, is necessary to meet the Millennium Development Goals of reducing acute illness, morbidity and mortality in both genders and all age groups.2

The majority of hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa have no critical care services and where it does exist such facilities are rudimentary.1

The University of North Carolina has an established presence at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe, Malawi since 2007 and observed that many surgical patients meet criteria for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, but many of them die.3 Our hypothesis for this study is that critically ill surgical patients have a high mortality. We therefore sought to elucidate the characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU to better define the burden of disease and identify strategies for improving critical care services.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all patients admitted to the KCH Intensive Care Unit (KCH-ICU) from January to December 2010. KCH is a tertiary 600-bed hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi. It is the referral center for the entire Central region of Malawi, with a catchment population of 9 million.

KCH-ICU is a 4-bed unit that provides care for critically ill patients from all clinical services. The ICU team is comprised of one full-time non-physician healthcare provider and nine nurses without specialty training and the admitting service’s consultant provides oversight. The ICU has three ventilators, invasive pressure monitoring equipment and pulse oximetry. Diagnostic capabilities include a clinical laboratory for basic investigations (complete blood count, chemistry, microbiology). Radiology services include portable radiography and ultrasonography only.

Data was obtained from the ICU logbook include patient demographics (age and gender), admitting service (surgery, medicine, obstetrics/gynecology or trauma), admission diagnosis, ventilator use and outcome (death versus discharge from ICU). Data was analyzed with Stata 11.2. Descriptive statistics were calculated using chi2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank for the age variable. Both the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board and the Malawi National Health Research Council approved this study.

Results

The ICU admitted 234 patients during the study period. One hundred and two (55%) were female, and the median age was 26.5 years (range 4–88). The majority of patients (82%) were admitted from one of the three surgical services: general surgery, trauma or obstetrics/gynecology.

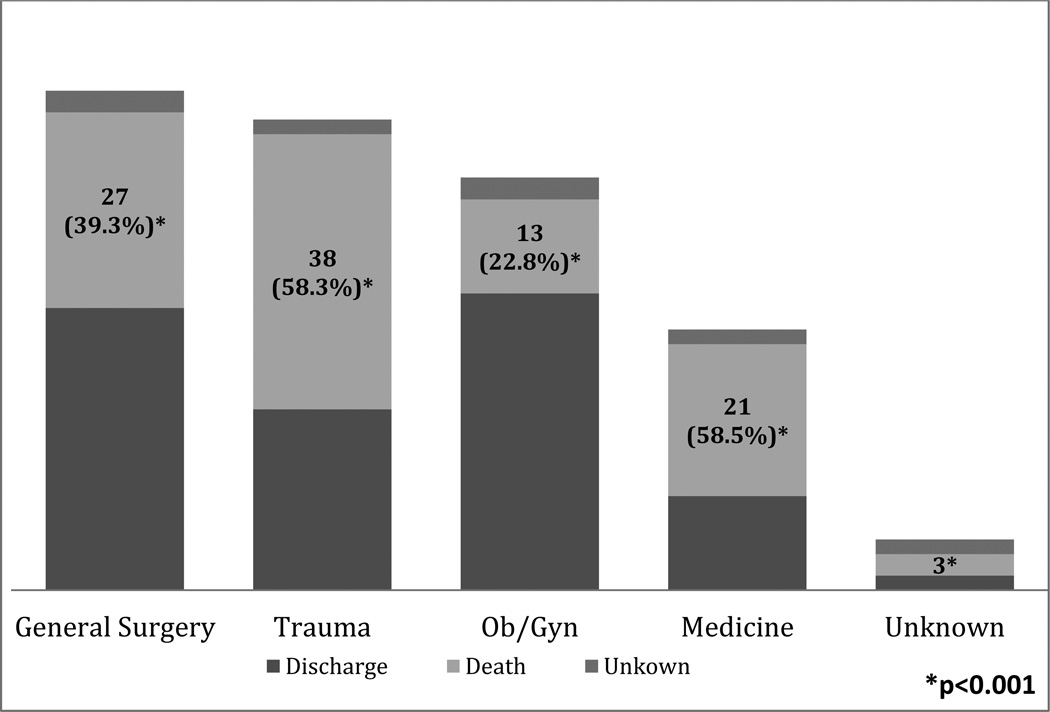

The majority (89%) of the patients admitted to the ICU required ventilator support for at least part of their stay. The median length of stay was 3 days (range 1–31) (Table 2). There was a high overall mortality rate (44%) with significant differences in the mortality rate among the four services (Figure 1). The highest mortality rate was seen in medicine and trauma patients (55 and 57 %, respectively) while obstetrics/gynecology patients had the lowest rate (22%). Of the 102 patients that died, 78 (76%) came from one of the three surgical services. Patients who died were significantly older than patients who survived with a median age of 34 vs. 30 (p=0.025).

Figure 1.

Distribution of critical care mortality based on admitting service.

Discussion

Among patients admitted to the KCH-ICU, age and admitting service were associated with outcome. Older patients and patients from general surgery, trauma surgery, and medical services had worse outcomes. Use of the ventilator and blood transfusions were not associated with outcome. Surgical patients made up the majority of ICU admissions, similar to other ICUs in developing countries.4

The mortality rate in our study population (43.8%) is high compared to other ICUs in the region (27–30%).4,5 The majority of subjects in our study (88.4%) were mechanically ventilated unlike other reports (12%–13.7%). This explanation is supported by the higher mortality rate among the subset of mechanically ventilated subjects in other studies (53–83%).5 Obstetrical and gynecologic patients were least likely to die in the ICU, with the diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage having the lowest mortality rate (23.5%). We believe this may be attributable to the availability of transfusion capabilities6,7 and younger age cohort.

Much of critical care involves relatively inexpensive training in how to recognize, respond to, and monitor acute illness. Simple interventions that are known to be effective, such as early fluid resuscitation and antibiotics in septic shock, can be achieved with education and efficient utilization of available resources.8

We demonstrated a high mortality rate among head injured patients (57.1%) similar to other studies in sub-Saharan Africa. More stringent criteria for admission may be useful to appropriately select patients likely to benefit from intensive care. In many developing countries, health care practitioners, due to local socio-cultural norms and beliefs, do not universally accept the concept of brain death.9 A reorientation of the concept of medical futility may need to be reinforced to medical providers and the public at large in Malawi.

Providing critical care in a developing country is extremely challenging. The WHO states that every hospital where surgery and anesthesia are performed should have an ICU, defined as a specialized unit with more skilled nursing care than on general wards, 24 hour monitoring and the provision of oxygen.10 The lack of prioritization of critical care in resource-poor settings is based on a presumed lack of effectiveness in improving population health. This is further compounded by lack of trained personnel, low nurse-to-patient ratios and higher disease complexity due to delayed presentation. In sub-Saharan Africa, the focus of the local Ministry of Health has been on providing basic and preventative health services as these countries are faced with a choice of funding prevention efforts versus providing funds for tertiary care services. The relegation of critical care services and indeed care of surgical diseases is misplaced.

The limitations of this study include the inability to determine severity of illness on ICU admission using APACHE III scores and the attribution of the cause of death due to the paucity of autopsy data.

Significant improvements are needed in critical care service delivery in sub-Saharan Africa. Increased resources could improve mortality rates in the critically ill and translate to improvement in the overall health care system to benefit all patients.

Summary: The burden of surgical diseases in sub Saharan Africa is high. A cross sectional observational study was conducted to assess the burden of surgical diseases on critical care services. Improvements on critical care services will be central to future efforts at reducing surgical morbidity and mortality and improving outcomes in all critically ill patients.

Table 1.

Bivariate analysis of based on outcome

| N (%) | Survived | Died | Missing data |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects | 233 (100%) | 118 (50.6%) | 102 (43.8%) | 13 (5.6%) | - |

| Gender | 0.29 | ||||

| Male | 103 (44.2%) | 47 (45.6%) | 51 (49.5%) | 5 (4.9%) | |

| Female | 130 (55.8%) | 71 (54.5%) | 51 (39.2%) | 8 (6.2%) | |

| Age (years) | 0.0049 | ||||

| 0–18 | 34 (14.6%) | 20 (58.9%) | 11 (32.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | |

| 18–40 | 97 (41.6%) | 49 (50.2%) | 42 (43.4%) | 6 (6.2%) | |

| >40 | 41 (17.6%) | 18 (43.9%) | 22 (53.7%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Missing | 61 (26.2%) | 31 (50.8%) | 27 (44.3%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Admitting Specialty | 0.004 | ||||

| General Surgery | 68 (29.2%) | 36 (52.9%) | 28 (4.2%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| Trauma Surgery | 65 (27.9%) | 26 (40%) | 37 (56.9%) | 2 (3.1%) | |

| Obs-Gynecology | 55 (23.6%) | 40 (72.3%) | 12 (21.8%) | 3 (5.5%) | |

| Medicine | 33 (14.2%) | 13 (39.4%) | 18 (54.6%) | 2 (6.1%) | |

| Missing | 12 (5.2%) | 3 (25%) | 7 (58.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Ventilator use | 0.101 | ||||

| Yes | 206 (88.4%) | 98 (47.6%) | 96 (46.6%) | 12 (5.8%) | |

| No | 14 (6.0%) | 10 (71.3%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unknown | 13 (5.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Transfusion | 0.727 | ||||

| Yes | 143 (61.4%) | 66 (53.9%) | 58 (40.6%) | 8 (5.6%) | |

| No | 60 (25.8%) | 27 (45%) | 29 (48.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | |

| Unknown | 30 (12.9%) | 14 (46.7%) | 15 (50%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Top 8 Admitting diagnosis | 0.068 | ||||

| Abdominal Sepsis | 40 (17.2%) | 22 (55%) | 16 (40%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Head injury | 35 (15.0%) | 14 (40%) | 20 (57.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Injury, all other | 29 (12.5%) | 12 (41.4%) | 16 (55.2%) | 1 (3.5%) | |

| Respiratory failure | 19 (8.1%) | 10 (52.6%) | 7 (36.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Postpartum Hemorrhage | 17 (7.3%) | 12 (70.6%) | 4 (23.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Bowel obstruction | 16 (6.9%) | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Postpartum Sepsis | 14 (6.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Eclampsia | 11 (4.7%) | 7 (63.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

References

- 1.Baker T. Critical care in low-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2009 Feb;14(2):143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004 Sep 4–10;364(9437):900–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuel JC, Akinkuotu A, Villaveces A, Charles AG, Lee CN, Hoffman IF, et al. Epidemiology of injuries at a tertiary care center in Malawi. World J Surg. 2009 Sep;33(9):1836–1841. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towey RM, Ojara S. Practice of intensive care in rural Africa: an assessment of data from Northern Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2008 Mar;8(1):61–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oji A. Intensive care in a developing country: a review of the first 100 cases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1986 May;68(3):122–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prata N, Mbaruku G, Campbell M, Potts M, Vahidnia F. Controlling postpartum hemorrhage after home births in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Jul;90(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarus JV, Lalonde A. Reducing postpartum hemorrhage in Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Jan;88(1):89–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner L. An Anthropological exploration of contemporary bioethics. J. Med Ethics. 1998;24:127–133. doi: 10.1136/jme.24.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Surgical Care at the District Hospital. World Health Organization Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]