Abstract

Solvent-based on-column focusing is a powerful and well known approach for reducingthe impact of pre-column dispersion in liquid chromatography. Here we describe an orthogonal temperature-based approach to focusing called temperature-assisted on-column solute focusing (TASF). TASF is founded on the same principles as the more commonly used solvent-based method wherein transient conditions are created thatlead to high solute retention at the column inlet. Combining the low thermal mass of capillary columns and the temperature dependence of solute retentionTASF is used effectivelyto compress injection bands at the head of the column through the transient reduction in column temperature to 5 °C for a defined 7 mm segment of a 6 cm long 150 μm I.D. column. Following the 30 second focusing time, the column temperature is increased rapidly to the separation temperature of 60 °C releasing the focused band of analytes. We developed a model tosimulate TASF separations based on solute retention enthalpies, focusing temperature, focusing time, and column parameters. This model guides the systematic study of the influence of sample injection volume on column performance.All samples have solvent compositions matching the mobile phase. Over the 45 to 1050 nL injection volume range evaluated, TASF reducesthe peak width for all soluteswith k’ greater than or equal to 2.5, relative to controls. Peak widths resulting from injection volumes up to 1.3 times the column fluid volume with TASF are less than 5% larger than peak widths from a 45 nL injection without TASF (0.07 times the column liquid volume). The TASF approach reduced concentration detection limits by a factor of 12.5 relative to a small volume injection for low concentration samples. TASF is orthogonal to the solvent focusing method. Thus, it canbe used where on-column focusing is required, but where implementation of solvent-based focusing is difficult.

Keywords: Volume overload, capillary HPLC, on-column focusing, temperature

1. Introduction

Small volume samples are commonly encountered in the fields of metabolomics, proteomics, forensics, neurochemistry and single cell analysis [1-4]. The high complexity and mass limited nature of such small samples necessitates the enhanced detection sensitivity offered by reductions in column diameter that limit sample dilution.[5,6]. The recent significant improvements in column technology, i.e. sub-2 μm fully porous and core-shell particles [7-10], while welcome also create a problem—sensitivity to solute dispersion from pre-column processes including volume overload. Volume overload occurs when the relative contribution of the injection plug width to dispersion is large compared to that produced by on-column convective dispersion[11,12]. In this work we describe an approach to mitigate the detrimental effects of pre-column dispersion created by volume overload in capillary columns using temperature-assisted on-column solute focusing (TASF).

One potential solution to the volume overload problem is to reduce the injected volume. For example 5-nL injection volumes are possible in theory with various split- and timed-injection methods [13,14], but achieving them with currently available instrumentation is non-trivial. Such a small injection volume with current valve technology is not possible as a reduction in sample volume does not necessarily produce a proportional reduction in the effective volume loaded onto the column due to dispersion contributions by valve passages and all other pre-column volumes [15]. Fortunately, on-column focusing is a simple and effective process that can minimize the effects of volume overload [5,16]. On-column focusing occurs when injected solute bands are compressed at the head of the column due to high solute retention and their subsequent elution at a much higher velocity by the mobile phase. Upon injection the sample solvent system becomes the mobile phase for the period of time required to flush the loaded sample through the injection zone [12,17-19]. This solvent-based focusing works particularly well for aqueous samples injected into a reversed phase column. Recently the effect has seen a resurgence as a means to mitigate pre-column dispersion [20,21] and to counteract the dilution of first dimension analyte bands in online multi-dimensional liquid chromatography [22-28]. Application of solvent-based on-column focusing in capillary scale columns has been more widespread because of their greater susceptibility to volume overload [29-34].

The one fundamental requirement for on-column focusing is the establishment of high retention conditions at the head of the column. The means to attain this retention are not limited to changes in sample solvent composition. The mobile phase has a very strong influence on solute retention; this is why solvent-based focusing works well, but temperature also influences solute retention in LC albeit to a much smaller extent. The effect of temperature on retention is determined by the solute’s partial molar enthalpy of retention. Increases in column temperature in RPLC generally decrease solute retention. In fact, high temperature liquid chromatography has exploited elevated temperature’s influence on retention, selectivity, solvent viscosity and analyte diffusivity to attain fast, efficient separations in a wide variety of applications discussed in the following reviews and book[35-38].

Increasing column temperature can decrease the effectiveness of solvent-based focusing in reversed phase chromatography in particular. A significant increase in column temperature generally leads to a decrease in retention which may call for a commensurate reduction in solvent strength to maintain constant retention. [39]Thus, in comparison to near-room temperature separations, high temperature separations may use weaker, more aqueous mobile phases. In such cases, the contrast between retention in water from the sample and retention in the more aqueous mobile phase decreases, thus on-column focusing becomesless powerful.

In contrast, TASF benefits from elevated separation temperatures. TASF is based on the premise that the transient reduction in column temperature for a short column segment, ca. < 1 cm, for a short period of time, <1 min., will increase solute retention fostering effective on-column focusing. The freezing point of the mobile phase and pressure limitations of the pumping system set the minimum achievable column temperature to near −20 °C for typical aqueous/organic/reversed-phase systems. [40]

Capillary columns offer low thermal mass and small radial temperature gradients allowing rapid changes in column temperature during the chromatographic run. Temperature programming and various temperature ‘pulsing’ techniques have been successfully used with capillary scale columns. These methods have emphasized the benefits of rapid column heating to generate temperature gradients, increase analysis speed or tune chromatographic selectivity [41-45]. Only the Greibrokk group has explored the potential for sub-ambient column temperatures to focus large injection volumes onto capillary columns. In their work temperature programming initiated at sub-ambient temperatures, ca. 5 °C, was used to focus samples of retinyl esters, polyolefin based Irganox antioxidants and ceramides made in 80-100% acetonitrile prior to separation using a neat acetonitrile mobile phase and C18 column [46-50]. High hydrophobicity and poor analyte solubility in water, necessary for on-column focusing was common to all of this work.

The primary method used to achieve sub-ambient column temperatures involves the use of programmable column ovens with cooling capabilities where the entire column is cooled via convection. There are two noteworthy limitations to this approach: 1) due to air’s low heat capacity, rapid changes in column temperature are difficult to obtain, 2) reduction in column temperature significantly increases mobile phase viscosity. Cooling the entire column to sub-ambient temperatures puts serious restrictions on achievable linear velocities due to maximum pump pressure limitations. For example, cooling a 5 cm long column to 5 °C would increase column pressureby a factor of 3, compared to an identical60 °C isothermal analysis. Reducing the temperature of only short segments of the column is an effective solution to the pressure problem. Cooling 1 cm of the hypothetical 5 cm column to 5 °C, while holding the remaining 4 cm at 60 °C, does significantly increase backpressure, albeit only by 35% relative to the 60 °C isothermal column. Maximum pump pressure is a limitation to TASF and needs to be considered, although the recent improvements in pump technology and increases in maximum operating pressure have lessened its influence.

To solve the problems associated with convection ovens two alternative cooling methods have been suggested. Holm and coworkers [51] developed a device where a single Peltier type thermoelectric cooler was used to cool an aluminum block through which a short segment of the column passes allowing large volume samples of the same Irganox antioxidants described above to be focused. After focusing, the column was moved manually, in space, from the cold zone to a programmable column oven where the separation was performed. Collins et al. presented another application of thermoelectric column cooling where an array of ten independently controlled 1.2 cm square Peltier units were aligned allowing precise temperature control for capillary monolith synthesis and temperature programmed separations of alkylbenzene mixtures[52]. In a second approach to temperature assisted focusing Eghabali et al. cooleda 1 cm long section of the column, near its outlet, cryogenically to approximately −20 °C [53]. Heating was achieved using boiling water. What is unique about this focusing method was placement of the cold trap at the column outlet. This was done to trap and re-focus specific analytes (proteins) within regions of interest improving the observed signal-to-noise ratio (S/N).

In this paper, we describe an efficient approach to on-column focusing we refer to as TASF. We view this method as orthogonal to the conventionally used solvent-based on-column focusing methods so it can be employed independently or in conjunction with solvent-based methods. We report on the efficacy of the TASF method applied injection volumes ranging from about 7% to 150% of the column’s fluid volume. Samples of solutes were made in mobile phase to avoid solvent focusing. The TASF approach was found to effectively reduce pre-column dispersion for all injection volumes tested. This method is ideal for applications where on-column focusing is required to mitigate volume overload and focus analyte bands, but where sample solvent compositions are fixed and not significantly different from the mobile phase, i.e. where implementation of solvent-based focusing is difficult.

2.Theory

The signal observed in a chromatographic separation is influenced by all the components in the system and their individual contributions to the observed variance of the chromatographic band. The variance of the signal observed by the detector, in time units is given by:

| (1) |

where and are the variances induced by the injector, column and detector; accounts for the sum of all other sources of dispersion in the chromatographic system, i.e. tubing, connections, etc. We note that the formulation shown is based on the assumption of independence of the processes contributing each term and that there is no mass overload (i.e., the system operates where the solute distribution isotherms are linear). In the ideal case the column is the dominant contributor to the observed band variance, but this is not generally true when high efficiency capillary columns are employed. The dispersion resulting from extra-column processes, primarily those related to the injection volume and connection tubing, become more significant.

Figure 1 shows that the column consists of three segments. The first is a short segment inside the injector/fitting that is void of packing and held at room temperature. The void ensures that all analytes reach the cooled focusing segment at the same time. Since this section of the column has no stationary phase, all solutes arrive at the next segment, the trapping zone, at the same time. This simplifies trapping although it adds considerably to pre-column bandspreading. The trapping zone is under temperature control by a Peltier thermoelectric device (TEC). It is followed by the remainder of the column at a constant temperature. For more details about the experimental setup, see section 3.3.1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of instrument configuration used to implement the TASF approach. The Peltier cooling element (TEC) is shown in red and blue. The importance of the pre-column void is apparent due to the size of the nut and PEEK sleeve used to connect the column to the injection valve stator. The pop-out at the bottom of the figure highlights how the TEC should be aligned with the top of the packed bed for effective TASF implementation. The size of the TEC dictates the maximum length of the trapping zone; the remainder of the column length was maintained at constant temperature by the resistive heater shown in red.

We can divide the observed peak time variance into three segments, the pre-column , column and post-column :

| (2) |

The pre-column variance is defined as:

| (3) |

where is the broadening due to the injection time and represents the dispersion in the void section. The importance of this region is described in detail in the supplemental material (S2.2).

The column variance is composed of two terms: the variance due to the trapping, variable temperature segment and the isothermal, separation section of the column :

| (4) |

Assuming the largest contribution to is from broadening induced by the Poiseuille flow profile in the connection tubing between the column outlet and the flow cell, can be calculated from Taylor theory as:

| (5) |

where v is the average linear velocity, r is the radius of the connecting tubing, l is its length, and Dm,i,2 is the solute diffusion coefficient for solute i in the isothermal section of the column.

The time variance from the injection of a volume Vinj onto a column of radius a is given by Eq. 6:

| (6) |

where ∊tot, is the column’s total porosity, v, is the interstitial velocity, and and are the retention factors for solute on the trapping and separation sections of the column. The term in the square brackets corresponds to the well-known relationship that the length variance of a rectangular concentration profile of width is w2/12. [54]The width (w) is related to the injection volume (Vinj), the liquid filled cross sectional area of the column (πa2∊tot), and a compression factor from retention at the head of the column. The term outside the brackets converts this length variance into a time variance as the band elutes from the isothermal, separation portion of the column.

The contribution to observed bandspreading due to the void at the head of the column in Eq. 3 is difficult to model theoretically due to its short length and relatively wide diameter. Thus, this variance was estimated experimentally. Details are provided in section 2.2 of the supplemental information. In particular, we estimate the variance for an unretained compound from the void in an isothermal column (no trapping). This variance is decreased by the factor in the trapping zone in a TASF experiment and increased by the factor at the column outlet as shown in Eq. 7.

| (7) |

Thus, combining Eqs. 6 and 7 we have an expression for the pre-column time variance of:

| (8) |

The primary advantage of TASF is exploited in the first term of Eq. 8 as is smaller than .

The column variance can be increased or decreased by cooling a segment of the column. Knox’s recent formulation emphasizing the importance of mass transport in the flowing mobile phase [55] was used to determine column variance. From plate theory the length variance due to the column is given by:

| (9) |

where H is the height equivalent to a theoretical plate and L is the length of the column. Converting to reduced parameters, we obtain the following expression for the length variance in an isothermal column:

| (10) |

where dp is the particle diameter, and vi is the reduced velocity for solute i. and n is mobile zone’s velocity dependence. The B- and C-coefficients of Eq. 10 have their usual meanings related to axial diffusion and mass transfer into and out of the stationary zone. The A- , D-, and n coefficients relate to mobile zone broadening caused by the flow path structure and tortuosity and mass transport among flow paths [55].

Because there are two segments of the column that may be at different temperatures, we must calculate the length variances for the trapping and separation segments of the column independently and add the result. Although the physical length of the trapping segment of the column is fixed at LT, the effective length of the trapping zone experienced by solute i, Li,1, depends on its velocity in the trapping zone and the focusing time tfocus as shown by Eq. 11. Thus,

| (11) |

The variance due to the trapping segment of the column is:

| (12) |

where vi,1 is the reduced velocity for solute in the trapping segment of the column. Analogously the variance due to the remainder of the column is given by:

| (13) |

where vi,2 is the reduced velocity for solute i at the column temperature. Adding Eqs. 12 and 13 yields a column distance variance for TASF separations as:

| (14) |

It is instructive to point out when the column is not subjected to TASF, i.e. when vi,1 = vi,2, and Li,1 = 0 Eq. 14 reduces to Eq. 10. Also note that, under the assumptions that the parameters A,B,C,D, and n vare independent of k’, the temperature dependence resides in the reduced velocities. When the separation is clearly B-term dominated, h1 < h2, so there is a small decrease in column variance due to trapping. In the more common situation in which velocity-dependent mass transport is dominant, the opposite is true.

Converting the column variance in length units to time units gives:

| (15) |

Table 1 shows the relevant time variance equations (5, 6, 7, 15) which can be substituted into Eq. 2 to obtain an observed band variance for isothermal and TASF separations.

Table 1.

Time variance equations used to calculate individual contributions to observed peak variance due to the injection, pre-column void, and post-column tubing utilizing the TASF approach.

| Variance Contribution |

Equation Number | Equation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection | 6 |

|

|

| Pre-column Void | 7 |

|

|

| Column | 15 |

|

|

| Post-column Tubing | 5 |

|

3. Materials and methods

3.1 Reagents and solutions

Methyl, ethyl, n-propyl, and n-butyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoate (parabens) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Standard solutions of each paraben were prepared by first dissolving in acetonitrile, then diluting to the desired concentration and solvent composition with deionized water. DI water was from an in-house Millipore Milli-Q Synthesis A10 water purification system (Billerica, MA) and was used without further treatment. Phosphoric acid was from Fisher Scientific (HPLC grade, Fair Lawn, NJ), and HPLC grade acetonitrile was from Spectrum Chemical (New Brunswick, NJ). All mobile phases were vacuum degassed and filtered twice through 0.45 μm nylon filters (Millipore).

3.2 van‘t Hoff retention studies

3.2.1 Instrumentation

A Jasco X-LC 3000 system consisting of a 3059AS autosampler, dual 3085PU semi-micro pumps, 3080DG degasser, 3080MX high pressure mixer, CO-2060 thermostated column compartment, 3177UV variable wavelength UV absorbance detector, and LC-Net II/ADC from Jasco Inc. (Easton, MD) was used to evaluate the temperature dependence of solute retention. Data analysis and instrument module control was achieved with EZChrom Elite software from Agilent Technologies (version 3.2.1, Santa Clara, CA).

3.2.2 Chromatographic conditions

A mixture of 25 μM uracil and 50 μMmethylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben and butylparaben was made in mobile phase. Samples were injected onto a Waters Acquity BEH C18 column (50 mm × 1.0 mm I.D.; 1.7 μmdp; Waters Corp., Millford, MA). Isocratic separations were made at a flow rate of 200μL/min with a mobile phase consisting of 80% 10 mM H3PO4, pH 2.7, 20% acetonitrile. The column temperature was varied from 25 to 75 °C in 10 °C steps, the injection volume was 1.0 μL, and peaks were detected by absorbance of UV light at 210 and 220 nm. Injections at each temperature were performed in triplicate with the order of the subsequent temperature analysis selected at random.

3.3 TASF instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

3.3.1 Column preparation

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the instrument used for TASF separations. Capillary columns were prepared by packing 1.7 μm BEH C18 particles (Waters) into 150 μm I.D. fused-silica capillaries from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ). Columns were fritted by sintering 2 μm, solid borosilicate spheres (Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA) into the end of the column blank using an electrical arc. Particles were slurried in isopropanol (Spectrum) at a concentration of 50 mg/mL, sonicated for 25 minutes and packed using the downward slurry method at 27500 psi using a Model DSHF-302 pneumatic amplification pump from Haskel (Burbank, CA). The packing solvent was acetone (Sigma). Care was taken to pack columns of defined length, ca. 5-6 cm, by limiting the volume of slurry, and subsequent mass of particles, loaded into the packing system. This allowed columns to be packed leaving a 2 cm section free of stationary phase at the head of the column.

3.3.2 TASF instrumentation

Packed columns were fitted directly to a Cheminert injection valve (Model 07Y-03BH, VICI Valco, Houston, TX) equipped with a 2 μLsample loop. The sample loop was over-filled with sample. Injection volume was controlled by controlling the injection time. By this means we achieved estimated injection volumes from 45 to 1950 nL. A PeakSimple module and associated software (Version 393, SRI Instruments, Las Vegus, NV) were used to actuate the valve. An Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano high pressure gradient pump (Thermo Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA) with a an upper pressure limit of 800 bar delivered mobile phase and UV absorbance detection at 210 nm was achieved by a Waters Acquity TUV detector equipped with a 10 nL flow cell (Waters). Data acquisition and export was achieved through connection of the analog output of the Acquity TUV to the Jasco ADC described in the van‘t Hoff studies.The ADC sampling frequency was 25 Hz, with analysis performed using PeakFit (v4.12, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA).

As shown in Fig. 1 two different temperature control assemblies were used to regulate column temperature during the chromatographic run. A Peltier based thermoelectric cooling element (TEC) from Custom Thermoelectic (part number 03111-5L31-03CF, Bishopville, MD) controlled the first 7 mm of the column. Utilization of a TEC allowed first cooling the head of the column to 5 °C for 30 s during the injection process, followed by a rapid heating period to the separation temperature of 60 °C by reversing TEC polarity. To promote rapid heat transfer between the TEC and column a gallium-indium based eutectic was used at the interface between the TEC and column [56,57]. After the desired focusing time TEC polarity was changed manually using a two position switch. An Agilent 6286A DC power supplypowered the TEC, temperature was regulated by manually tuning the current delivered at fixed potential. A Type T thermocouple (COCO-003, Omega, Stamford, CT) and a Eurotherm 2416 temperature controller (Invensys Eurotherm, Ashburn, VA) were used to monitor TEC temperature.Over the course of a day’s experiments temperature was found to be relatively stable, ±1 °C. The TEC was fixed to a custom aluminum, water cooled heat sink. A chilled ethylene glycol/water mixture was used to regulate heat sink temperature.The flow rate forthe ethylene glycol/water mixture was 1 L/min; it was delivered by a Kryo-Thermostat WK 5 chilled circulator (Lauda-Brinkmann, Delran, NJ).

The second, isothermal section of the column was heated using a Love Model 1500 proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller (Dwyer Instruments, Michigan City, IN) connected to a Kapton resistive heater (KHLV-103/10-P, Omega). The heater was attached to an aluminum block onto which the column was placed. A temperature sensor (SA1-RTD, Omega) was fitted inside the aluminum block and the signal was fed back to the controller; temperature control precision in the isothermal section of the column was found to be about ±0.1 °C.

3.3.3 Injection volume studies

A series of 15 injection volumes from 45 to 1050 nLwere performed with and without transiently cooling the head of the column to test the ability of the TASF methodology to alleviate dispersion due to pre-column volumes and volume overload. The column used in all injection volume experiments was 60 mm × 150 μm I.D. and left with a 2 cm void. The flow rate was 3μL/min, the mobile phase was 80:20 10 mM H3PO4/acetonitrile and the UV detection wavelength was 210 nm. Isothermal separations utilized a column temperature of 60 °C. TASF separations employed the same analysis temperature; the focusing temperature was set to 5 °C. The head of the column was held at this temperature for 30 s before manually reversing the polarity on the TEC, heating the column to 60 °C. Isothermal column backpressure was near 330 bar and 470 bar at the 5 °C focusing temperature. Samples were made in mobile phase at concentrations such that the mass of each solute injected onto the column was between 3.5 and 9 ng. Table S3 provides details regarding injection volume and sample concentrations used.

3.3.4 Limit of quantitation study

Separations were performed with two injection volumes, 60 and 1875 nL. After determining the ethylparabenlimit of quantitation for the Acquity TUV detector using the 10σ value for detector noise,solute concentrations for each injection volume were selected. The 60 nL injections were performed with samples composed of 1.25 μMethylparaben; the 1875 nL sample was made at 100 nM. The chromatographic conditions for these separations were nominally identical to those used in the injection volume studies described in Section 3.3.2 with one notable difference. Focusing conditions were tailored for the separation of ethylparaben to increase usable injection volumes for TASF separations. Ethylparaben optimization was performed by increasingthe focusing time from 30 to 45 s for the 1875 nL sample. A detailed description related to selection of this focusing time is reserved for Section 4.5.

The following procedure was used to address issues related to carryover between subsequent injections. Two new 2.0 mL glass syringes from Hamilton (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV) were used, the first to flush the injection valve with acetonitrile between samples; the second for the paraben samples. The paraben sample syringe was rinsed three times with acetonitrile before changing to a different concentration sample. Before injection of paraben samples onto the column, 0.5 mL of acetonitrile was flushed through the 2 μL sample loop while the valve was in the load-position. The valve was actuated to the inject-position and mobile phase was passed through the sample loop for five minutes at a flow rate of 3 μL/min. An injection blank consisting of mobile phase was performed to confirm no sample carryoverfollowing this cleaning procedure. This procedure was repeated between samples.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Temperature dependence of retention factors

A series of van‘t Hoff studies were performed using a commercially available Acquity BEH C18 columnprior to implementation of TASF experiments. Partial molar enthalpies of retention for each solute were determined fromvan‘t Hoff plots (Eq. S1) and retention data over the 25-75 °C temperature range(Table 2). Inspection of residuals indicated there was no significant change in retention enthalpy with temperature. The high degree of linearity allowed extrapolation to the sub-ambient focusing temperature of 5 °C. The ability to predict solute retention factors at specific focusing and separation temperatures was critical to modeling the potential of the TASF approach.

Table 2.

Partial molar enthalpies of retention for methylparaben through butylparaben obtained from slopes of the van‘t Hoff plots(Fig. S1). Chromatographic conditions can be found in section 3.2.2.

| Solute | −ΔH0/R (K) | Error | Intercept | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylparaben | 1999 | 11 | −5.09 | 0.03 |

| Ethylparaben | 2219 | 15 | −4.87 | 0.05 |

| Propylparaben | 2566 | 21 | −4.98 | 0.07 |

| Butylparaben | 2961 | 26 | −5.24 | 0.08 |

4.2 Simulation of TASF chromatograms

Equations 5, 6, 7 and 15 were used to determine the void, column, and post-column variances and assess the relative contribution of experimentally accessible parameters on observed peak variance. To determine the total dispersion of a hypothetical Gaussian peak with no volume overload, combination Eqs. 5, 7, and 15 yield:

| (16) |

Assuming a rectangular injection plug the variance due to injection was redefined as:

| (17) |

where describes the variance of a rectangle.

Solving the convolution integral [54]for a rectangular pulse and a Gaussian distribution yields:

| (18) |

uponsubstitution of Eqs. 16 and 17 where C0 is sample concentration and tR,t is the retention time for solute t. The equation used to determine tR,i is provided in section S2.2. A total of ten injection volumes were simulated by substitution of the values reported in Table 3 into each term of Eqs. 16 and 17. Injection volumes used in calculations are reported in Table S2.

Table 3.

Parameters involved in isothermal and TASF simulations.

| Parameter | Determination | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ts | 0.5 min | |

| Vinj | 45-1050 nL (See Table S2) | |

| F | 3 μL/min | |

| Tf | 5 °C | |

| Tsep | 60 °C | |

| van‘t Hoff Plot Slope | Experiment | See Table 2 |

| van‘t Hoff Plot Intercept | ||

| Dm (310 K) | Literature[40,62] | See Table S1 |

| η(T) | Literature[63,64] | See Eq. S2 |

| ∈ tot | Literature [65] | 0.537 |

| A | 20 | |

| B | 4.5 | |

| C | Literature [55] | 0.01 |

| D | 0.42 | |

| n | 1 | |

| dp | 1.7 μm | |

| L | 6.0 cm | |

| φ | 0.2 | |

| Experiment | 0.000571 min2 | |

| dpost col | 25 μm | |

| lpost col | 25 cm |

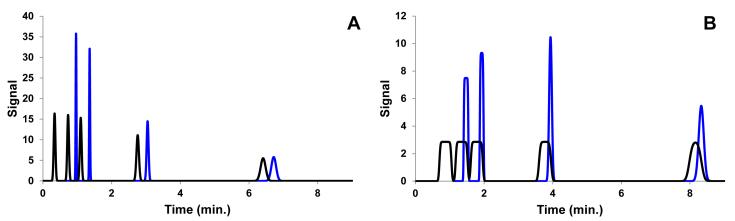

Figure 2 shows two overlays generated from Eq. 18. The blue trace in both panels illustrates the effect of a 5 °C focusing temperature on the observed chromatogram for two injection volumes, 45 and 1050 nL. These injection volumes were selected to mimic experimental results. Using our system the smallest achievable injection volume was 45 nL. The largest sample used in the injection volume studies was 1050 nL. In order of elution, peaks were simulated for uracil, methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben using appropriate van‘t Hoff parameters and diffusion coefficients. In this calculation uracil was used to mark system dead time and was defined to have no retention at either the focusing or separation temperatures. Due to this definition uracil peak shape does not improve when the TASF approach is used at either injection volume. TASF mitigates pre-column induced dispersion. Simulations assumed all pre-column dispersion was due to volume overload and the pre-column void. For the 45 nL injection volume shown in panel A peak heights increased from 15.9 and 15.1 to 34.9and 30.4 units for methylparaben and ethylparaben when using TASF. To determine the influence of the pre-column void on observed peak width a hypothetical system with no pre-column void, i.e. , was simulated. Figure S2 demonstrates the influence of the pre-column void with 5 and 45 nL injections. A 5 nL injection volume was also selected because it corresponds to just under 1% of the column volume, analogous to a commonly used 1 μL injection onto a 5 cm × 2.1 mm I.D. column. Under the simulated conditions with a 5 nL injection volume, implementation of TASF actually degrades column efficiency by 22% (methylparaben) due to the reduction in column efficiency at 5 °C. Increasing the injection volume to 45 nL, still without a pre-column void, already shows improvement in observed column efficiency when using TASF. This result indicates that a 45 nL injection volume does correspond to volume overload for this column.

Figure 2.

Simulated isothermal (———) and TASF (———) separations of paraben mixtures made in mobile phase generated using Eq. 17. The first peak in each panel is uracil, the void time marker was defined to have no retention at separation and focusing temperatures. A 45 nL injection is shown in panel A, panel B shows a 1050 nL injection. Peak area for each solute was held constant at both injection volumes to allow easy comparison of peak shape between injection volumes. Values used for simulations can be found in Table 3.

Panel B of Fig. 2 demonstrates the ability of TASF to focus large volume samples onto the head of the column. Defining the liquid volume of the column as the fluid volume of the column (πa2L∊tot) excluding the pre-column void, a1050 nLinjection corresponds to 160% of the column volume. The simulated chromatogram clearly shows significant volume overload. Although TASF with a 5 °C focusing temperature decreased peak width for all solutes, this temperature (5 °C)did not suffice to increase retention for methylparaben and ethylparabento create Gaussian peaks. Retention factors calculated from the van‘t Hoff parameters in Table 2 are shown in Table S1. To solve this problem further reductions focusing temperaturewouldbe required for further reductions in peak width for low retention solutes such asmethylparaben and ethylparaben.

In order to visualize the effect of TASF over a wide range of injection volumes a metric easily relatable to experimental data was required. The flat-topped peaks obtained at large injection volumes are not well fit by various Gaussian modifications, e.g. exponentially modified Gaussian (EMG) or 5-parameter EMG. However, experimental values for the full width at half maximum (FWHM) can be measured readily. The following approximation was made to allow generation of FWHM vs. Vinj plots.

| (18) |

Equation 18 combines the FWHM of a Gaussian peak, σt,G, calculated from Eq. 16 and adds it to the injection variance width, . The square root of the sum accurately estimates the FWHM of peaks from purely Gaussian to purely rectangular over the range of values used here with a maximum error of 12%. Systematic increases in the overestimation values for FWHM values with increased injection value were observed. Figure 3 was generated from a series of ten injection volumes ranging from 45 to 1050 nL and values in Table 2. Panels A-D correspond to methylparaben through butylparaben; TASF separations with a 5 °C focusing temperature are shown in blue. Isothermal separations at 60 °C are in black. Red dashed lines indicate a 5% increase in FWHM for 45 nL isothermal injections. A 5% increase in FWHM is approximately equal to a 10% reduction in column efficiency. Benefits obtainable with TASF across all injection volumes are most prominent for low retention solutes at low injection volumes and high retention solutes at large injection volumes. At 5 °C TASFreduces the observed FWHM for a 45 nL injection of methylparabenby a factor of 2.2, speaking to the method’s ability to reduce pre-column dispersion. TASF is only able to reduce the width of the observed small injection volume butylparaben band by 5% for a 45 nL injection. This explains why the relative difference between FWHM values for the isothermal and TASF separations show in panels A-D of Fig. 3 decreases with increasing isothermal retention factor. At injection volumes greater than the column volume TASF is able to limit the rate of increase for observed FWHM values. This effect is most apparent when comparing panels A and D for methylparaben and butylparaben. At an injection volume of 450 nL the TASF FWHM value for methylparaben has risen above the 5% increase line for a 45 nL injection. This does not occur for butylparaben at 5 °C until about 1500 nL.

Figure 3.

Simulated isothermal (●) and TASF (●) separations where the injection volume of paraben samples made in solvent systems identical to the mobile phase was varied from 45 to 1050 nL. Panels A, B, C, and D correspond to simulations for methylparaben through butylparaben, respectively. Red dashed lines represent a 5% increase in the FWHM for a 45 nLisothermal injection for each solute. Increases in simulated FWHM values with increasing in injection volume were due to the pre-column void and volume overload. TASF reduced peak FWHM for all solutes across all injection volumes under the conditions reported in Table 3.

4.3 Experimental determination of the effect of TASF on peak width

A series of fifteen injection volumes were performed under isothermal and TASF conditions with paraben samples prepared in mobile phase. Example chromatograms are shown in Fig. 4; both panels display TASF separations with 5 °C focusing temperatures in blue and 60 °C isothermal separations in black. These experimental results mirror the simulated results of Fig. 2. Panel A corresponds to a 45 nL injection and B a 1050 nL injection. Estimating the column volume to be 640 nL, the 45 nL injection corresponded to 7% of the column volume and the 1050 nL injection 160%. The increase in peak height for TASF analyses was the method’s most obvious advantage. The peak height values for methylparaben and ethylparabenin panel A of Fig. 4 increased by 20% relative to their peaks in the isothermal separation. At both injection volumes, Fig. 4 panels A and B, methylparaben, ethylparaben, and propylparaben benefitted most from TASF. At the retention factor extremes characterized by uracil, no retention, and butylparaben, k’60 °C = 38.4, the influence of TASF was reduced. Uracil, with k’ = 0, cannot be focused and butylparaben with its large k’ is focused without the assistance of reduced temperature. Of course, TASF would improve the butylparaben peak width had larger volumes been injected. These results indicate that under experimental conditions there was an optimal retention factor ratio present between the focusing and separation segments of the column. Panel B of Fig. 4 demonstrates the potential for TASF to minimize volume overload. The inset in panel B shows the propylparaben peak from an isothermal separation with a 1050 nL injection volume. It shows that flat topped peaks characteristic of volume overload were obtained even for relatively high retention compounds. When TASF was used the large volume sample was effectively focused in the cold trap increasing peak heights for methylparaben, ethylparaben, and propylparaben by factors of 3.2, 4.2 and 3.4, respectively.

Figure 4.

Demonstration of the potentiation for the TASF approach to reduce observed peak width for samples made in mobile phase at multiple injection volumes. Isothermal (———) separations were performed at 60 °C. A 5 °C focusing temperature and 30 s focusing time were used with the TASF approach (———). Panel A shows results from a 45 nL injection, panel B a 1050 nL injection. The pop-out in panel B illustrates the flat topped peak profiles observed for the isothermal propylparabenpeak. For chromatographic conditions see Section 3.3.3.

Figure 5 shows measured peak width at half height for each solute as a function of injection volume. These experimental results correspond to the simulated results in Fig. 3. Panels A, B, C, and D of Fig. 5 present the results of these experiments for methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben, respectively. Isothermal separations are plotted as black circles; TASF experiments are blue. Red dashed lines correspond to a 5% increase in FWHM for a 45 nL injection. Error bars were calculated from the standard error for each measured FWHM, with n = 3. Qualitatively, the shape of the plots and relative increase in FWHM between isothermal and TASF experiments mimic the results predicted by the simulations. Low retention solutes are more susceptible to volume overload-related increases in FWHM. The ability of TASF to limit the rate of FWHM increase with increasing injection volume for samples made in mobile phase was impressive. Methylparaben, with an isothermal retention factor of 2.5 was the only solute tested where volume overload induced dispersion increased FWHM values by more than 5% of the value for a 45 nL injection with TASF on. These results demonstrate experimentally the capability of TASF to focus all samples made in mobile phase despite a large pre-column void and modest focusing temperature of 5 °C.

Figure 5.

Results from volume overload experiments performed under isothermal (●) and TASF (●) conditions with paraben mixtures made in mobile phase. Panels A, B, C, and D correspond to methylparaben through butylparaben peaks, respectively. Red dashed lines represent a 5% increase in the FWHM for a 45 nL injection for each solute. TASF was able to reduce observed FWHM values relative to its isothermal counterpart for every solute at each injection volume. For chromatographic conditions see Section 3.3.3.

While the guidance from the theory is quite good, there are discrepancies between the predicted and experimental results. For example, the predicted benefit of TASF for small volume injections and low k’ solutes is better than we realize experimentally. One factor is our uncertainty about the variance contributed by the void. This variance is most important for low k’ compounds. Another factor is our lack of knowledge of the actual temperature inside the column. We model the changes in temperature as a step function, but they are actually not. In addition, the temperature changes are initiated by a manual switch. We are in the process of addressing these limitations.

4.4 Improvements in concentration detection limit offered by temperature assisted solute focusing

As part of our initial assessment of the practical implementation of the TASF approach, we evaluated improvements in the concentration detection limits for the targeted determination of ethylparaben. Assuming constant peak area, reductions in observed peak width due to TASF result in taller peaks with enhanced S/N ratios. To demonstrate our ability to model the effect of TASF and realize the benefits in practice, an experiment was designed to address the following question. Knowing the signal required to be 10-times the standard deviation of the baseline, can you quantitate an injection using TASF to create a narrow peak at the detection limit from a volume overloaded injection at a concentration well below the isothermal detection limit?

In this example the standard state retention enthalpy for the target analyte, ethylparaben, was experimentally determined. Its retention factor and elution velocity in the 5 °C, 7 mm long trapping section at a flow rate of 3 μL/min were calculated to be 18.0 and 0.15 mm/s. For effective focusing, the leading edge of the ethylparaben band must remain within the trapping zone, i.e. not elute from the trap during the focusing time. This condition places a limit on the maximum allowable injection volume given the defined trap length and temperature. Assuming no dispersion from either the leading or trailing edges of the ethylparaben band it will take 7 s for the leading edge of the band to reach the trapping zone and a further 47 s for it to reach the end of the trapping zone. The total injection time is thus 54 s. The presence of dispersion and other nonidealities of our model will cause the band’s front edge to reach the end of the trapping zone in a time shorter than 54 s. Experimentally, a focusing time of 45 s was used with an injection time of 37.5 s (1875 nL).

The chromatograms in Fig. 6 show the results for two injections of ethylparaben under isothermal (black traces) and the optimized ethylparaben TASF conditions (blue traces). Panel A shows a 60 nL injection of 1.25 μMethylparaben in mobile phase with a 30 s focusing time. Due to the 1.2 s long injection required to achieve a 60 nL injection volume, increasing the focusing time to 45 s to accommodate larger injection volumes was unnecessary. The red dashed line is at an absorbance value equal to ten times the standard deviation of the baseline noise. The 60 nL injection was designed to act as a control and establish the detection limits for the TASF separations. The detection limit for ethylparaben using the TASF approach and a 60 nL injection was 7.5 × 10−14 moles. Panel B shows a more powerful demonstration of TASF’s ability to improve concentration detection limits. To highlight this, the time axes of panels A and B were plotted to roughly center the ethylparabenpeaks for isothermal and TASF separations, while the length of each window was held constant at 0.8 minutes. Increasing focusing time and injection volume resulted in an increase in ethylparaben retention time and peak width. Ethylparaben concentration in the 1875 nL sample was 100 nM, 1.9 × 10−13 moles on-column. The most impressive aspect of the TASF methodology came from the comparison of the 1875 nL isothermal and TASF separations. A red arrow is used to highlight what we believe to be the severely broadened ethylparaben peak which is not distinguishable from the baseline noise. The isothermal column is clearly volume overloaded. Only using TASF we were able to focus the large volume sample, nearly three times the fluid volume of the column, to achieve a quantifiable peak. This ability reduced the concentration detection limits for this analysis by a factor of 12.5, relative to the 60 nL injection.

Figure 6.

Chromatograms from the limit of quantitation study performed following optimization of TASF conditions for the separation of ethylparaben. Ethylparaben concentrations for 60 nL (A) and 1875 nL (B) injections were 1.25 μM and 100 nM. These concentrations were selected to be just above the detector’s limit of quantitation, shown by red dashed lines. The TASF approach offered reductions in peak width and increases in peak height making previously unquantiafiable isothermal analyses (———) quantifiable when implementing TASF (———). The red arrow in panel B shows what we believe to be the isothermal ethylparaben peak. For chromatographic conditions see Section 3.3.4.

5. Conclusions

We have investigated the efficacy of temperature assisted on-column solute focusing to ameliorate all sources of pre-column dispersion and their associated reductions in column efficiency. The primary advantages to TASFforinducing efficient on-column focusing are as follows.

The approach effectively mitigates increases in peak width introduced by injecting large volumes of samples dissolved in solventsmatching the mobile phase. TASF is orthogonal to solvent-based focusing methods allowing its use to replace or augment solvent-based methods.

A variance based model facilitates accurate in silico simulation of TASF separations based onsolute retention enthalpies, focusing temperature, focusing time, and column parameters.

Optimized TASF analyses will decrease the concentration detection limit when large volumes with respect to the void volume are injected.

Potential applications of TASF: 1. continuous, online microdicodialysis sampling of for the rapid quantitation of neurotransmitters[58-60] where large aqueous samples are injected onto a capillary column operated with less than 5% acetonitrile in the mobile phase and 2. re-focusing fractions of first dimension effluent sampled and injected onto the second dimension column in capillary online comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography, LCxLC[61].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Transient reduction in head-of-column temperature leads to on-column focusing.

A variance-based bandspreading model predicts experimental results

Method mitigates pre-column dispersion in capillary scale separations

The approach permits large-volume injections reducing concentration detection limits

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health though Grant R01GM044842 (SGW) and an Arts & Sciences Fellowship from the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences (SRG). The generous gift of Acquity BEH C18 column, packing material, and Acquity TUV were from Dr. Ed Bouvier and Dr. Moon Chul Jung of Waters Corp. is acknowledged. We thank Tom Gasmire, Josh Byler, and Jim McNerney from the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences Machine and Electronics shops for their efforts to construct the TASF instrument. James Grinias from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill is also acknowledged for helpful discussions regarding column packing. Finally, we thank Prof. Peter Carr from the University of Minnesota and Prof. Dwight Stoll from Gustavus Adolphus College for helpful discussions regarding this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early versiup of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Desmet G, Eeltink S. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:543. doi: 10.1021/ac303317c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Caliguri EJ, Capella P, Bottari L, Mefford IN. Analytical Chemistry. 1985;57:2423. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mefford IN, Caliguri EJ, Grady RK, Capella P, Durkin TA, Chevalier P. Methods in Enzymology. Elsevier; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Newton AP, Justice JB. Analytical Chemistry. 1994;66:1468. doi: 10.1021/ac00081a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Guiochon GA, Colin HM. Microcolumn high-performance liquid chromatography. Elsevier; Amsterdam; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gluckman JC, Novotny MV. Microcolumn separations columns, instrumentation, and ancillary techniques. Elsevier; Amsterdam; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bobály B, Guillarme D, Fekete S. Journal of Separation Science. 2014;37:189. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201301110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fekete S, Guillarme D. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1320:86. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fekete S, Guillarme D. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1308:104. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sanchez AC, Friedlander G, Fekete S, Anspach J, Guillarme D, Chitty M, Farkas T. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1311:90. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Colin H, Martin M, Guiochon G. Journal of Chromatography A. 1979;185:79. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bakalyar S, Phipps C, Spruce B, Olsen K. Journal of Chromatography A. 1997;762:167. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00851-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tsuda T, Nakagawa G. Journal of Chromatography A. 1980;199:249. [Google Scholar]

- [14].McGuffin VL, Novotny M. Analytical Chemistry. 1983;55:580. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Foster MD, Arnold MA, Nichols JA, Bakalyar SR. Journal of Chromatography A. 2000;869:231. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00957-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mills MJ, Maltas J, John Lough W. Journal of Chromatography A. 1997;759:1. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsimidou M, Macrae R. Journal of Chromatography A. 1984;285:178. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vukmanic D, Chiba M. Journal of Chromatography A. 1989;483:189. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Layne J, Farcas T, Rustamov I, Ahmed F. Journal of Chromatography A. 2001;913:233. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)01199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gritti F, Sanchez CA, Farkas T, Guiochon G. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217:3000. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sanchez AC, Anspach JA, Farkas T. Journal of Chromatography A. 2012;1228:338. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Apffel JA, Alfredson TV, Majors RE. Journal of Chromatography A. 1981;206:43. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)82604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Erni F, Frei R. Journal of Chromatography A. 1978;149:561. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Horváth K, Fairchild JN, Guiochon G. Journal of Chromatography A. 2009;1216:7785. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vivó-Truyols G, van der Wal S, Schoenmakers PJ. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:8525. doi: 10.1021/ac101420f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Oda Y, Asakawa N, Kajima T, Yoshida Y, Sato T. Journal of Chromatography A. 1991;541:411. doi: 10.1023/a:1015848806240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Simpkins SW, Bedard JW, Groskreutz SR, Swenson MM, Liskutin TE, Stoll DR. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217:7648. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Groskreutz SR, Swenson MM, Secor LB, Stoll DR. Journal of Chromatography A. 2012;1228:31. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Šlais K, Kouřilová D, Krejčí M. Journal of Chromatography A. 1983;282:363. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ling BL, Baeyens W, Dewaele C. Journal of Microcolumn Separations. 1992;4:17. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vissers J, Deru A, Ursem M, Chervet J. Journal of Chromatography A. 1996;746:1. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Héron S, Tchapla A, Chervet JP. Chromatographia. 2000;51:495. [Google Scholar]

- [33].León-González ME, Rosales-Conrado N, Pérez-Arribas LV, Polo-Díez LM. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217:7507. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].D’Orazio G, Fanali S. Journal of Chromatography A. 2013;1285:118. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vanhoenacker G, Sandra P. Journal of Separation Science. 2006;29:1822. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vanhoenacker G, Sandra P. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2007;390:245. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Teutenberg T. High-Temperature Liquid Chromatography: A User’s Guide for Method Development. RSC Pub; Cambridge: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Teutenberg T. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2009;643:1. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thompson JD, Carr PW. Analytical Chemistry. 2002;74:4150. doi: 10.1021/ac0112622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zarzycki PK, Wlodarczyk E, Lou D-W, Jinno K. Analytical Sciences. 2006;22:453. doi: 10.2116/analsci.22.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Greibrokk T, Andersen T. Journal of Separation Science. 2001;24:899. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jandera P, Blomberg LG, Lundanes E. Journal of Separation Science. 2004;27:1402. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200401852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gu B, Cortes H, Luong J, Pursch M, Eckerle P, Mustacich R. Analytical Chemistry. 2009;81:1488. doi: 10.1021/ac802022z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Causon TJ, Cortes HJ, Shellie RA, Hilder EF. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:3362. doi: 10.1021/ac300161b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pursch M, Eckerle P, Gu B, Luong J, Cortes HJ. Journal of Separation Science. 2013;36:1217. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201200818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Molander P, Haugland K, Hegna DR, Ommundsen E, Lundanes E, Greibrokk T. Journal of Chromatography A. 1999;864:103. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)01006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Molander P, Thommesen SJ, Bruheim IA, Trones R, Greibrokk T, Lundanes E, Gundersen TE. Journal of High Resolution Chromatography. 1999;22:490. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Molander P, Holm A, Lundanes E, Greibrokk T, Ommundsen E. Journal of High Resolution Chromatography. 2000;23:653. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Molander P, Holm A, Lundanes E, Hegna DR, Ommundsen E, Greibrokk T. The Analyst. 2002;127:892. doi: 10.1039/b201651f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Larsen Å, Molander P. Journal of Separation Science. 2004;27:297. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200301706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Holm A, Molander P, Lundanes E, Greibrokk T. Journal of Separation Science. 2003;26:1147. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Collins D, Nesterenko E, Connolly D, Vasquez M, Macka M, Brabazon D, Paull B. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83:4307. doi: 10.1021/ac2004955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Eghbali H, Sandra K, Tienpont B, Eeltink S, Sandra P, Desmet G. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:2031. doi: 10.1021/ac203252u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sternberg JC. 1966;2:205. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Knox JH. Journal of Chromatography A. 2002;960:7. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Anderson TJ, Ansara I. Journal of Phase Equilibria. 1991;12:64. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Prokhorenko V, Kotov V. High Temperature. 2000;38:954. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Liu Y, Zhang J, Xu X, Zhao MK, Andrews AM, Weber SG. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:9611. doi: 10.1021/ac102200q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang J, Liu Y, Jaquins-Gerstl A, Shu Z, Michael AC, Weber SG. Journal of Chromatography A. 2012;125:54. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zhang J, Jaquins-Gerstl A, Nesbitt KM, Rutan SC, Michael AC, Weber SG. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:9889. doi: 10.1021/ac4023605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Haun J, Leonhardt J, Portner C, Hetzel T, Tuerk J, Teutenberg T, Schmidt TC. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:10083. doi: 10.1021/ac402002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Nishida K, Ando Y, Kawamura H. Colloid & Polymer Science. 1983;261:70. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Guillarme D, Heinisch S, Rocca JL. Journal of Chromatography A. 2004;1052:39. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Billen J, Broeckhoven K, Liekens A, Choikhet K, Rozing G, Desmet G. Journal of Chromatography A. 2008;1210:30. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhang Y, Wang X, Mukherjee P, Petersson P. Journal of Chromatography A. 2009;1216:4597. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.