Abstract

The GnRH receptor (GnRHR) mediates the pituitary functions of GnRH, as well as its anti-proliferative effects in sex hormone-dependent cancer cells. Here we compare the signaling of GnRHR in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. We first noticed that the expression level of PKCα, PKCβII and PKCε is much higher in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrope cell lines vs. LNCaP and DU-145 cell lines, while the opposite is seen for PKCδ. Activation of PKCα, PKCβII and PKCε by GnRH is relatively transient in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrope cell lines and more prolonged in LNCaP and DU-145 cell lines. On the otherhand, the activation and re-distribution of the above PKCs by PMA was similar for both gonadotrope cell lines and prostate cancer cell lines. Activation of ERK1/2 by GnRH and PMA was robust in the gonadotrope cell lines, with a smaller effect observed in the prostate cancer cell lines. The Ca2+ ionophore A23187 stimulated ERK1/2 in gonadotrope cell lines but not in prostate cancer cell lines. GnRH, PMA and A23187 stimulated JNK activity in gonadotrope cell lines, with a more sustained effect in prostate cancer cell lines. Sustained activation of p38 was observed for PMA and A23187 in Du-145 cells, while p38 activation by GnRH, PMA and A23187 in LβT2 cells was transient. Thus, differential expression and re-distribution of PKCs by GnRH and the transient vs. the more sustained nature of the activation of the PKC-MAPK cascade by GnRH in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines respectively, may provide the mechanistic basis for the cell context-dependent differential biological responses observed in GnRH interaction with pituitary gonadotropes vs. prostate cancer cells.

Keywords: GnRH, GnRH receptor, Protein kinase C, MAP kinase, Pituitary cells, Prostate cancer cells

1. Introduction

GnRH agonists and antagonists are now part of the treatment of androgen-dependent carcinoma of the prostate (Emons et al., 1997). The dogma is that GnRH agonists desensitize the pituitary and GnRH antagonists block endogenous GnRH activity, both leading to reduced serum testosterone levels known as “chemical castration”. However, several reports have demonstrated evidence of a direct effect of GnRH upon sex hormone-dependent tumors including prostate cancer cells (Bahk et al., 1998; Dondi et al., 1994, 1998; Emons et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Jungwirth et al., 1997; Kraus et al., 2004, 2006; Limonta et al., 1992, 1993, 1999; Moretti et al., 1996; Qayum et al., 1990a,b; Wells et al., 2002). Binding sites, expression of GnRH and its receptor (GnRHR) and direct growth regulatory effects of GnRH in the above cancer cells have been reported (Bahk et al., 1998; Dondi et al., 1994, 1998; Emons et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Jungwirth et al., 1997; Kraus et al., 2004, 2006; Limonta et al., 1992, 1993, 1999; Moretti et al., 1996; Qayum et al., 1990a,b; Wells et al., 2002). Regarding signaling of GnRHR in cancer cells, GnRH was reported either not to affect (Emons et al., 1996), or to stimulate phosphoinositide (PI) turnover (Imai et al., 1993; Keri et al., 1991; Segal-Abramson et al., 1992; Wells et al., 2002). GnRH was also reported to inhibit EGF receptor (EGFR) functions in ovarian and endometrial cancer cell lines; apparently by stimulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases (Grundker et al., 2001). In prostate cancer cells, it is thought that GnRHR signaling includes activation of Gi and PI turnover (Limonta et al., 1999; Wells et al., 2002); as in other cancer cells (Imai et al., 1993; Keri et al., 1991; Segal-Abramson et al., 1992). One possibility that was raised is that enhanced PI turnover will activate PKC, resulting in negative transmodulation of EGFR due to Thr654 phosphorylation (Wells et al., 2002), known to down regulate EGFR and inhibit it’s signaling (Chen et al., 1996a; Davis and Czech, 1987; Lin et al., 1986). In addition; prostate cancer cell’s proliferation depends on functional EGFR autocrine loop, and DU-145 cell growth and xenograft tumor invasion are mediated by the EGFR (Jones et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1993; Putz et al., 1999; Tillotson and Rose, 1991; Turner et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1995). It was also reported that GnRH reduced cAMP levels and EGF binding sites in LNCaP and DU-145 cells (Limonta et al., 1999; Moretti et al., 1996). Others have implicated the MAPK pathway, in particular JNK and p38 in the apoptotic effects elicited by GnRH agonists in prostate cancer cells (Kraus et al., 2004, 2006; Maudsley et al., 2004).

It is now recognized that a single GnRHR type I mediates both the pituitary and the cancer cells effects of GnRH analogs (Morgan et al., 2003; Pawson et al., 2005). We and others have shown the crucial role of the PKC-MAPK cascade in GnRHR signaling in pituitary gonadotropes (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2006, 2010; Kraus et al., 2001; McArdle et al., 2002; Naor, 1990, 1997, 2009; Naor et al., 2000; Sealfon et al., 1997; Shacham et al., 1999, 2001; Stojilkovic et al., 1994).

Thus, signaling at the pituitary level laid the foundation for the search of the mechanism of GnRH action in cancer cells in general and prostate cancer cells in particular. Here we compare selected signaling events in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrop cell lines vs. LNCaP and DU-145 prostate cancer cell lines. We propose that the transient vs. the more sustained nature of the activation of the PKC-MAPK cascade by GnRH in gonadotrope cell lines vs. cancer cells respectively, may provide the mechanistic basis for the differential responses observed in GnRH interaction with pituitary gonadotrope vs. cancer cells.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

αT3-1 and LβT2 cells were kindly provided by Dr. P. Mellon (UCSD, USA). LNCaP and DU-145 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). A stable GnRH agonist, [D-Trp6]-GnRH, PMA and A23187 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for protein transfer were purchased from Millipore Corporation (Bedford, MA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies to active ERK, JNK and p38MAPK (anti-DP, doubly phosphorylated) and polyclonal antibodies to general ERK, JNK and p38 were purchased from Sigma (Rehovot, Israel). The Western blotting detection reagent, ECL was obtained from Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies or goat anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West-Grove, PA, USA). All media and sera were from Biological Industries, Beit-Haemek, Israel. Vectashield mounting medium was from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, CA, USA). ExGen 500 transfection reagent was obtained from Fermentas International, Inc. (Burlington, Canada), FuGENE6 was obtained from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN, USA), and TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent was obtained from Mirus BIO Corporation (Madison, WI, USA).

2.2. Plasmids

GFP-PKCs constructs were obtained from Dr. C. Brodie, Bar-Ilan University, Israel (Blass et al., 2002; Kronfeld et al., 2000; Okhrimenko et al., 2005). GRASP65-RFP construct was kindly provided by Dr. K. Hirschberg (Tel-Aviv University).

2.3. Cell culture

αT3-1 and LβT2 cells were grown in monolayer cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics in humidified 5% CO2 at 37 °C. LNCaP and DU-145 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 containing fetal calf serum (FCS, 10%), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were then starved overnight in 0.1% serum DMEM. GnRH, PMA and A23187 were then added for the length of time as indicated.

2.4. MAPK activation

Cells were grown in 6 well plates and serum starved (0.1% cFCS) for 16 h. The cells were then washed 3 times with DMEM containing 0.1% BSA and incubated with GnRH, or PMA. ERK, JNK and p38MAPK activities were determined by Western blotting, using mouse monoclonal anti-active ERK, JNK and p38, as recently described (Bonfil et al., 2004; Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2009). Total ERK; JNK and p38MAPK were detected with polyclonal antibodies as a control for sample loading. The quantitiation of the WB was carried out as described (Bonfil et al., 2004; Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2009).

2.5. Cell transfection

In general, αT3-1 cells were transiently transfected by ExGen 500, while LβT2 cells by FuGENE6 or by its analog, TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent. LNCaP and DU-145 cells were transiently transfected by LipofectAMINE 2000. Approximately 30 h after transfection, the cells were serum starved (0.1% FCS) for 16 h and later stimulated with GnRH or PMA.

2.6. Confocal microscopy

Subconfluent cells were plated on 18 mm cover slips and transfected with 2 μg GFP-PKCs constructs. 30 h after transfection, cells were serum starved (16 h, 0.1% FCS) and treated with GnRH, or PMA for various time points. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS and cover slips were placed on glass slides with Vectashield mounting medium. Confocal fluorescent images were collected with a 40× magnification lens on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done between control and treatment groups using one-way ANOVA. In some experiments this was followed by a phosteriori Bonferroni t-test, which simultaneously compares means of all examined groups. Three independent experiments were carried out, each in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean of the three experiments. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

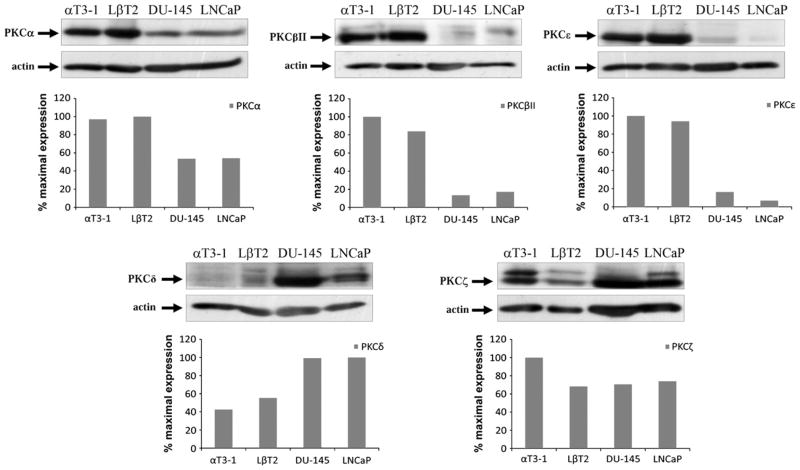

3.1. Expression of various PKCs in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

We first compared the expression of various PKCs in pituitary gonadotrope αT3-1 and LβT2 cell lines vs. the LNCaP and DU-145 prostate cancer cell lines. As seen in Fig. 1 the expression level of PKCε, PKCβII and PKCα are relatively high in gonadotrope cell lines, with lower expression level in the prostate cancer cell lines. In contrast, the expression level of PKCδ is relatively high in the prostate cancer cell lines and lower expression levels were found in the gonadotrope cell lines. The expression level of PKCζ was relatively high in αT3-1 cells and lower expression levels were observed in the other cells examined here. The differences in PKCs expression levels may be linked to downstream signaling as shown below. We therefore decided to further study the activation profile of the various PKCs by GnRH and PMA in αT3-1 gonadotrope cell line and compare them to the LNCaP and DU-145 prostate cancer cell lines.

Fig. 1.

Expression of various PKC isoforms in pituitary gonadotrope vs. prostate cancer cells. Whole-cell lysates from αT3-1, LβT2 gonadotrope cells and the prostate cancer cells LNCaP and DU-145 were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for the presence of the various PKC isoforms with isoform-specific antibodies. Blots were stripped and reblotted for actin for equal protein loading. Data was expressed as a ratio between PKC expression and actin. A representative blot is shown and similar results were observed in two other experiments.

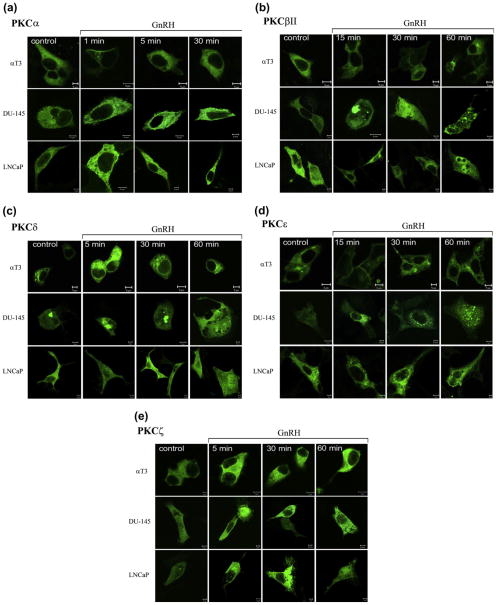

3.2. Activation of various PKCs by GnRH in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

Using GFP-PKCs constructs, we then monitored the cellular distribution of various PKCs in GnRH treated αT3-1 cells vs. LNCaP and DU-145 cells (Fig. 2). Translocation of PKCs to cellular membranes is regarded as a reliable measure for their activation (Dekker and Parker, 1994; Kikkawa et al., 1988; Newton, 1995, 1997, 2003a, b; Nishizuka, 1992a,b). GnRH induced a rapid and transient (1–5 min) translocation of PKCα to the plasma membrane in αT3-1 cells, followed by re-distribution of the isoform to the cytosol (5–30 min), as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) (Fig. 2A). Similar results were observed in LβT2 cells (not shown). On the other hand, translocation of PKCα to the plasma membrane in GnRH-treated LNCaP and DU-145 was somewhat slower and more persistent as it was also observed after 30 min of incubation (Fig. 2A). Translocation of PKCβII to the plasma membrane in αT3-1 cells was slower and was observed 15 min after stimulation with GnRH, increasing up to 30 min, followed by cytosolic re-distribution after 60 min as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) (Fig. 2B). However, re-distribution of PKCβII in DU-145 and LNCaP cells was more persistent and lasted up to 60 min of incubation with GnRH, with appearance of aggregates in the cells. Unlike PKCα and PKCβII, which were evenly distributed in the cytosol, PKCδ was localized to the cytosol and Golgi (Fig. 2C), as indicated by its colocalization with GRASP65 (cis-Golgi-associated protein) (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2005). GnRH stimulation of αT3-1 cells induced a rapid re-distribution of PKCδ from the cytosol and the Golgi to the perinuclear zone, which was detected after 5 min and lasted at least 60 min as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 2C). GnRH stimulation of DU-145 cells induced a slow but sustained re-distribution of PKCδ from the Golgi to the cytosol, whereas plasma membrane staining was observed at 30 min in LNCaP cells. PKCε was found to be cytosolic and a fraction was observed in the Golgi, similar to PKCδ, as indicated by its co-localization with GRASP65 (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010). Following GnRH stimulation of αT3-1 cells, PKCε was transiently re-distributed to the plasma membrane after 15 min, followed by re-distribution of the isoform to the cytosol (30–60 min) as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 2D). PKCε was re-distributed to the perinuclear zone at 15–30 min incubation in DU-145 and LNCaP cells. PKCζ was re-distributed by GnRH to the perinuclear zone of αT3-1 cells after 5 min of incubation, diminishing thereafter (Fig. 2E). In DU-145 and LNCaP cells, PKCζ was re-distributed by GnRH to the plasma membrane (5–60 min). We could not observe consistent activation or re-distribution of the other PKCs present in the cells. Hence, differential expression, activation profiles and re-distribution of selective PKCs is observed in GnRH-treated pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. DU-145 and LNCaP cells.

Fig. 2.

Fate of various PKC isoforms in GnRH-treated αT3-1, DU-145 and LNCaP cells. αT3-1, DU-145 and LNCaP cells were transfected with selective GFP-PKC isoforms constructs as described in Section 2. Serum-starved cells, 48 h after transfection, were treated with GnRH (10 nM) for different time points. Formalin-fixed slides were imaged under a 40× objective on Zeiss confocal microscope. At least 10 images from each treatment were collected and representative image is shown. The scale bar is 5 μm. A, PKCα; B, PKCβII; C, PKCδ; D, PKCε; E, PKCζ.

3.3. Activation of various PKCs by PMA in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

It was interesting to find out if differential localization of various PKCs as above, is dictated by the activating ligand, or is cell-context dependent. To that end we examined the fate of the above PKCs in PMA-activated cells. Incubation of αT3-1 cells with PMA resulted in rapid translocation of PKCα to the plasma membrane (1 min), which lasted the 30 min of the incubation time as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 3A). Similar results were observed in DU-145 and LNCaP cells. PKCβII translocation to the plasma membrane by PMA was observed after 15 min incubation in αT3-1 cells lasting for the 60 min examined as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 3B). Similar results were found in DU-145 and LNCaP cells. PKCδ was re-distributed by PMA from the cytosol and Golgi to the perinuclear zone and the plasma membrane (5–30 min) in αT3-1 cells, with the plasma membrane staining lasting for 60 min as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 3C). Similar results were found in DU-145 and LNCaP cells. PKCε was re-distributed from the cytosol and Golgi to the plasma membrane after 15 min of incubation with αT3-1 cells and the effect lasted for at least 60 min as recently shown (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010) and (Fig. 3D). Similar results were found in DU-145 and LNCaP cells. No significant and consistent changes in PKCζ re-distribution were observed in PMA-treated αT3-1, DU-145 and LNCaP cells (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Fate of various PKC isoforms in PMA-treated αT3-1, DU-145 and LNCaP cells. αT3-1, DU-145 and LNCaP cells were transfected with selective GFP-PKC isoforms constructs as described in Section 2. Serum-starved cells, 48 h after transfection, were treated with PMA (50 nM) for different time points. Formalin-fixed slides were imaged under a 40× on Zeiss confocal microscope. At least 10 images from each treatment were collected and representative image is shown. The scale bar is 5 μm. A, PKCα; B, PKCβII; C, PKCδ; D, PKCε; E, PKCζ.

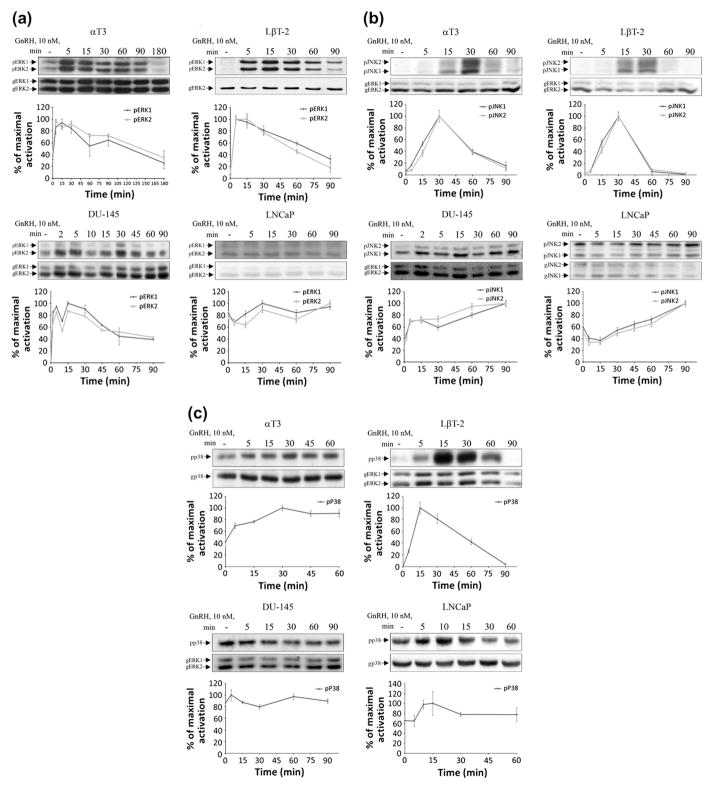

3.4. Activation of MAPKs by GnRH in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

Activation of PKCs is upstream to MAPK activation (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2000). Also, the kinetics of activation of MAPK can dictate the biological outcome of the response (Gesty-Palmer et al., 2006; Marshall, 1995). We therefore examined the activation profile of MAPKs by GnRH, PMA and A23187 in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. Incubation of αT3-1 and LβT2 cells with GnRH (10 nM) resulted in a rapid and robust activation of ERK1/2, with peak ERK1/2 activation at 5 min, declining thereafter to near basal levels after 90 min (Fig. 4A). GnRH enhanced ERK1/2 activation also in DU-145 cells, with a peak at 5–15 min declining thereafter, but still detectable at 90 min. No activation of ERK1/2 was noticed in LNCaP incubated with GnRH for up to 90 min. Also, no significant changes were observed between ERK1 and ERK2 activation in all the cells examined here.

Fig. 4.

Activation of MAPKs by GnRH in pituitary gonadotrope vs. prostate cancer cells. αT3-1, LβT2, DU-145 and LNCaP cells were serum-starved for 16 h before treatment with GnRH (10 nM) for 5–90 min. After the treatment, cell lysates were analyzed for ERK1/2 (A), or JNK1/2 (B), or p38 (C) activity by Western blotting using an antibody for phospho-ERK (pERK) (A), or phospho-JNK (pJNK) (B), or phospho-p38 (p38) (C), accordingly. Total MAPK (gERK1/2, or gJNK1/2, or gp38) was detected with polyclonal antibodies as a control for sample loading. In some cases when the total MAPK was too weak, we used another gMAPK antibody (gERK in B and C), to obtain good levels of expression, since we divide the levels obtained with the pMAPK antibodies to that obtained with the gMAPK antibodies. A representative blot is shown and similar results were observed in two other experiments. In this and subsequent figures, results from three experiments are shown as mean of maximal phosphorylation ± SEM.

JNK1/2 activation by GnRH in αT3-1 and LβT2 cells was transient with maximal response occurring after 30 min; declining to basal levels after 90 min (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, JNK1/2 activation by GnRH in DU-145 and LNCaP cells was sustained and lasted for at least 90 min. Also, no significant changes were observed between JNK1 and JNK2 activation in all the cells examined here. P38 activation by GnRH in αT3-1 cells was sustained and lasted for at least 60 min (Fig. 4C). GnRH enhanced transient p38 activation in LβT2 cells with a peak at 15 min declining thereafter. GnRH had no significant and consistent effect on p38 activity in DU-145 cells up to 90 min, with a small effect observed in LNCaP cells (10 min). The lack of significant effect in prostate cancer cells may be due to high basal levels.

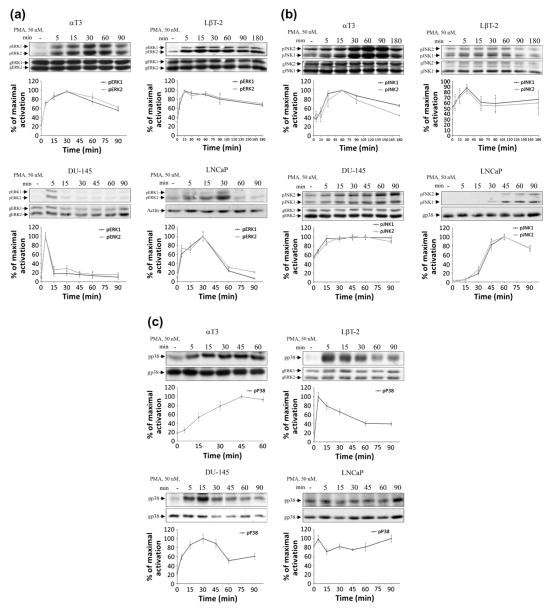

3.5. Activation of MAPKs by PMA in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

It was interesting to examine if the differential activation of MAPKs is ligand-, or cell-context dependent. We therefore examined and compared the activation profile of the various MAPKs by PMA in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. Incubation of αT3-1 and LβT2 cells with PMA (50 nM) resulted in a rapid and robust protracted activation of ERK1/2, with peak ERK1/2 activation at 15–30 min, but still detectable after 90 min (Fig. 5A). In DU-145 cells, the activation was transient with a peak at 5 min and a rapid decline to basal levels thereafter. A slower activation of ERK1/2 by PMA was observed in LNCaP cells, with a peak at 30 min, followed by a decline to basal levels (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Activation of MAPKs by PMA in pituitary gonadotrope vs. prostate cancer cells. αT3-1, LβT2, DU-145 and LNCaP cells were serum-starved for 16 h before treatment with PMA (50 nM) for 5–90 min. After the treatment, cell lysates were analyzed for ERK1/2 (A), or JNK1/2 (B), or p38 (C) activity by Western blotting using an antibody for phospho-ERK (pERK), or phospho-JNK (pJNK), or phospho-p38 (p38), accordingly. Total MAPK (gMAPK) were detected with polyclonal antibodies as a control for sample loading. A representative blot is shown and results from three experiments are shown as mean of maximal phosphorylation ± SEM.

JNK1/2 activation by PMA in αT3-1 and LβT2 cells was slow, peaking after 30 min, and returning to near basal levels after 180 min (Fig. 5B). Somewhat slower (peak at 60 min) but sustained activation profile for JNK1/2 by PMA was noticed in LNCaP cells and a smaller response was observed in DU-145 cells.

A gradual increase in p38 activation by PMA was noticed in αT3-1 cells during the 60 min examined here (Fig. 5C). A more transient response was noticed in LβT2 cells. Activation of p38 by PMA in DU-145 cells was bell shaped up to 60 min, with no effect observed in LNCaP cells, possibly due to high basal levels.

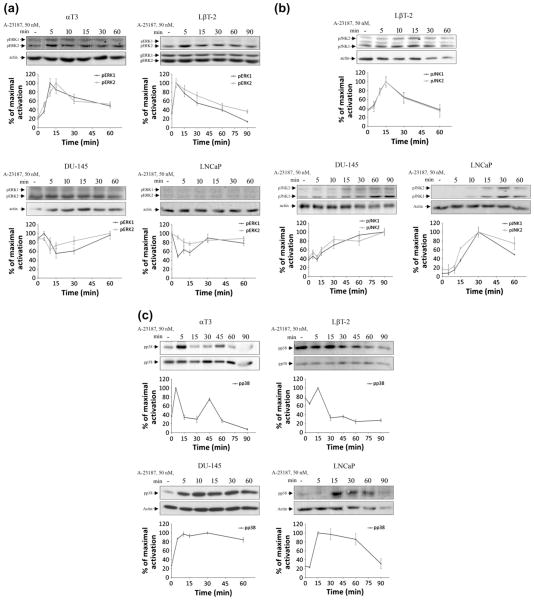

3.6. Activation of MAPKs by the calcium ionophore A23187 in pituitary gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines

Since Ca2+ plays a crucial role in GnRH activation of MAPKs (Mulvaney and Roberson, 2000), we then examined the activation profile of the various MAPKs by the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. Incubation of αT3-1 and LβT2 cells with A23187 resulted in rapid and transient activation of ERK1/2, with a peak at 5–15 min and a gradual decline to basal levels (Fig. 6A). No activation of ERK1/2 by A23187 was found in LNCaP and DU-145 cells, with an actual transient decrease observed, possibly due to activation of a Ca2+-dependent phosphatase.

Fig. 6.

Activation of MAPKs by the calcium ionophore A23187 in pituitary gonadotrope vs. prostate cancer cells. αT3-1, LβT2, DU-145 and LNCaP cells were serum-starved for 16 h before treatment with A23187 (50 nM) for 5–90 min. After the treatment, cell lysates were analyzed for ERK1/2 (A), or JNK1/2 (B), or p38 (C) activity by Western blotting using an antibody for phospho-ERK (pERK) (A), or phospho-JNK (pJNK) (B), or phospho-p38 (p38) (C), accordingly. Total MAPK (gMAPK) and actin (gERK and actin in A; actin in B and gp38 and actin in C) were detected with polyclonal antibodies as a control for sample loading. Data was expressed as a ratio between phospho-MAPK and total MAPK (gMAPK), or actin as indicated. A representative blot is shown and results from three experiments are shown as mean of maximal phosphorylation ± SEM.

A slow rise in JNK1/2 activity was observed in A23187-stimulated LβT2 cells, with a peak at 15 min and a gradual decline to basal levels (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained in αT3-1 cells (not shown). A gradual increase in JNK1/2 activity was observed in A23187-treated LNCaP and DU-145 cells, further maintaining this activation level for at least 90 min.

A biphasic increase in p38 activity was obtained in A23187-treated αT3-1 cells, while p38 activity was initially elevated (5–15 min) and later reduced in A23187-treated LβT2 cells (Fig. 6C). A slow and sustained rise in p38 activity was observed in A23187-treated LNCaP and DU-145 cells.

4. Discussion

Protein kinase C (PKC), a family of 10 isoforms (Kikkawa et al., 1988; Nishizuka, 1992a,b), plays a crucial role in cell signaling. We and others have shown that GnRH activates gonadotrope PKC and that PKC is involved in GnRH-stimulated gonadotropin synthesis and release (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2006, 2010; Harris et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2003; Maccario et al., 2004; Naor et al., 1985, 1989, 2000; Poulin et al., 1998; Stojilkovic and Catt, 1995; Stojilkovic et al., 1994).

The important role of PKC in GnRHR signaling prompted us to compare its expression and activation in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. High expression of PKCα, PKCβII and PKCε was found in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrope cell lines, with much lower expression in LNCaP and DU-145 cells. On the other-hand, PKCδ expression was high in the prostate cancer cells and low in the gonadotrope cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relative expression levels of various PKCs in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines.

| Cells | PKCα | PKCβII | PKCδ | PKCε | PKCζ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αT3-1 | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| LβT2 | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| LNCaP | + | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| DU145 | + | + | +++ | + | ++ |

Data from Fig. 1 was used to prepare the table.

We also noticed that while the activation of PKCα, PKCβII and PKCε by GnRH was relatively transient in αT3-1 and LβT2 cell lines, that observed in LNCaP and DU-145 cell lines was more prolonged. Also, differential re-distribution of PKCδ and PKCε was noticed in GnRH-treated gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines. On the otherhand, the activation and re-distribution of the above PKCs by PMA was similar for both gonadotrope and prostate cancer cell lines (Table 2). Thus, differential expression, activation and re-distribution of selected PKCs may contribute to differential functions of GnRH in the pituitary gonadotropes vs. cancer cells. Indeed, short-term activation of PKC is often associated with short-term events such as secretion and ion-influx. In contrast, sustained activation is suggested to regulate long-term effects such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, migration, or tumorigenesis (Koivunen et al., 2006).

Table 2.

The nature of the activation profile of various PKCs in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines.

| Cells | PKCα

|

PKCβII

|

PKCδ

|

PKCε

|

PKCζ

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GnRH | PMA | GnRH | PMA | GnRH | PMA | GnRH | PMA | GnRH | PMA | |

| αT3-1 | T | S | T | S | S | S | T | S | T | – |

| LNCaP | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | – |

| DU145 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | – |

Since PKC is implicated in MAPK activation by some GPCRs in general and by GnRH in particular (Naor, 2009; Naor et al., 2000) (for reviews), we then compared the activation profile of the various MAPKs in the GnRH target cells (Table 3). Whereas the activation of ERK1/2 by GnRH in αT3-1 and LβT2 cell lines is robust and relatively transient, a less profound and more sustained activation profile was found in DU-145 cells. Interestingly, whereas a transient activation of ERK1/2 was elicited by the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 in the pituitary gonadotrope cell lines, no activation of ERK1/2 by A23187 was found in prostate cancer cell lines. The results are interesting since ERK1/2 is mainly implicated in proliferation and as a pro-survival signal (Seger and Krebs, 1995). Thus, the small magnitude of ERK1/2 activation by GnRH and PMA in prostate cancer cell lines as compared to the gonadotrope cell lines, and the lack of ERK1/2 activation by GnRH in LNCaP cells, are in line with the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of GnRH agonists in prostate cancer cells (Kraus et al., 2004, 2006) (for reviews). Indeed, it was suggested that the spatial and temporal activation of ERK is kernel in determining cellular responses such as survival, proliferation and cell cycle arrest (White et al., 2008).

Table 3.

The nature of the activation profile of MAPKs in gonadotrope cell lines vs. prostate cancer cell lines.

| Cells | ERK1/2

|

JNK

|

p38

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GnRH | PMA | A23187 | GnRH | PMA | A23187 | GnRH | PMA | A23187 | |

| αT3-1 | T | S | T | T | T | T | S | S | T |

| LβT2 | T | S | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

| LNCaP | – | T | – | S | S | S | S | – | S |

| DU145 | S | T | – | S | S | S | – | S | S |

Interestingly, GnRH, PMA and A23187 induced a transient activation of JNK in αT3-1 and LβT2 cells, with a more sustained effect observed in the prostate cancer cell lines. As to p38 activation, GnRH induced a stimulatory effect in gonadotrope cell lines, but not in DU-145 cells. PMA stimulated p38 activation in gonadotrope cell lines and DU-145 cells but not in LNCaP cells. A23187 induced a transient effect of p38 activation in gonadotrope cell lines and a more sustained response in the prostate cancer cells (Table 3).

We have recently demonstrated that PKCα, PKCβII, PKCδ and PKCε are the major players in ERK1/2 and JNK activation by GnRH in gonadotrope cell lines (Dobkin-Bekman et al., 2010). Therefore, the differential expression and activation of the above PKCs is most likely responsible for the activation profile of the MAPKs by GnRH observed here. Indeed, the most common isoenzymes displaying expression alterations during cancer progression are α, β, and δ. Also, it has been previously shown that the activation of PKCδ is required for induction of sustained activation of JNK leading to apoptosis (Reyland et al., 1999). In another study, PKCδ was shown to mediate PMA-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells via the activation of p38 and JNK (Xiao et al., 2009).

Why is the activation profile of the MAPKs important? It was previously shown that transient vs. sustained activation of MAPK may elicit different biological responses (Gesty-Palmer et al., 2006; Marshall, 1995). For example; NGF induces sustained activation of ERK1/2 in PC12 cells, which result in differentiation. On the other hand, EGF stimulates a transient ERK1/2 response in PC12 cells, leading to proliferation (Marshall, 1995; York et al., 1998). A potential mechanism has been proposed. Activation of transcription factors by ERK1/2 results in the induction of immediate early genes. During transient ERK1/2 activation; the immediate early gene responses in the nucleus are relatively short, due to their degradation by the proteasome. In contrast, sustained activation would preserve the activation of the immediate early genes for several hours and this will then dictate biological specificity. Transient vs. sustained activation of ERK1/2 may be determined by receptor density (Murphy and Blenis, 2006). Indeed, the number of GnRHR in the gonadotrope cell lines is much higher than that observed in the prostate cancer cells (Franklin et al., 2003).

Still the question is how is the activation profile of MAPKs relevant to our study? First, we noticed that the activation profile of the various MAPKs by GnRH, PMA and A23187 was in general more sustained in the prostate cancer vs. the gonadotrope cell lines. This was mainly observed in the profile of JNK activation. Indeed, sustained activation of JNK (Chen et al., 1996b; Engedal et al., 2002; Guo et al., 1998; Joo and Yoo, 2009; Mansouri et al., 2003; Reyland et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2004) and p38 (Joo and Yoo, 2009; Mansouri et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004) is thought to mediate apoptosis. This may provide the basis for the pro-apoptotic effects of GnRH agonists and PMA in prostate cancer cells (Kraus et al., 2004, 2006) (for reviews).

Our observation that a single GPCR, the GnRHR elicits distinct responses in different target cells has been also observed in some other GPCRs. The calcium sensing receptor stimulates or inhibits the secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein depending on cellular context and coupling to Gs or Gi (Mamillapalli et al., 2008). However, while we attribute the signaling diversity to the kinetics of the activation of the PKC-MAPK pathway, (Mamillapalli et al., 2008) implicates the receptor and the G proteins as the target for signal diversity.

The main impact of GnRH action on pituitary gonadotropes is the maintenance of the gonadotropic phenotype and stimulation of gonadotropin synthesis and release. On the otherhand, inhibition of cell growth and induction of apoptosis are thought to be the major effects of GnRH analogs in sex hormone sensitive cancer cells (Kraus et al., 2006) (for review). Although Miles et al. (2004) demonstrated pro-apoptotic effects of GnRH in LβT2 gonadotrope cells, the effect was very small (only 10% of the cells), required prolonged incubation time with GnRH and may represent a non-physiological effect. It is thought that sex hormone sensitive cancer cells secrete GnRH and that GnRH interacts with the cells in an autocrine and sustained manner (Qayum et al., 1990a,b). On the other hand, hypothalamic GnRH acts on pituitary gonadotropes in a pulsatile manner. Hence, only cancer cells may be exposed to GnRH for prolonged time and therefore induction of apoptosis may be relevant to cancer cells only. Thus, the transient vs. the more sustained nature of the activation of the PKC-MAPK cascades by GnRH in pituitary gonadotrope vs. prostate cancer cells respectively, may provide the mechanistic basis for the differential biological responses observed in GnRH-target cells in a cell-context dependent manner. Our results presented here may open a vista into further research regarding the mechanistic basis of the differential responses of the GnRHR. For example it is possible that the half-life of the phosphoproteins induced by GnRH in pituitary gonadotropes is shorter as compared to those observed in the cancer cells. This may be the result of the transient vs. the more sustained activation of MAPKs observed in pituitary gonadotropes vs. the cancer cells. Still, since we are using here only cell lines and are comparing mouse and human cells, caution should be applied for the interpretation of the data.

Some sex steroids-dependent cancers such as prostatic cancer are currently treated with GnRH analogs for inhibition of gonadotropin and hence sex steroids, known as “Chemical castration”. The recent recognition of direct anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of GnRH analogs in some cancer cells opens a new vista for treatment of hormone-resistant prostatic cancer. Understanding the signaling of the GnRHR in cancer cells may point to potential combination therapy of GnRH analogs and regulators of signaling molecules directed to inhibit proliferation and support apoptotic pathways.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Mellon for the gonadotrope cell lines. This research was supported by The Israel Science Foundation (Grant No. 221/05), the German-Israeli Foundation for Research and Development (Grant No. I-751-168.2/2002), US–Israel Binational Science Foundation (Grant No. 2007057) and the Adams Super-Center for Brain Studies at Tel-Aviv University (to Z.N) and R01-CA89202 (to M. G. K.).

Abbreviations

- anti-DP antibodies

anti-diphospho-antibodies

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FSH

follicle stimulating hormone

- G-protein

guanine nucleotide binding protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GnRH

gonadotropin releasing hormone

- GnRHR

gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- GRASP65

Golgi reassembly stacking protein of 65 kDa

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PLCβ

phospholipase C-β

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKCs

PKC isoforms

- cPKC

conventional PKCs

- nPKC

novel PKCs

- aPKC

atypical PKCs

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- SEM

standard error of mean

References

- Bahk JY, Hyun JS, Lee H, Kim MO, Cho GJ, Lee BH, Choi WS. Expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH receptor mRNA in prostate cancer cells and effect of GnRH on the proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Urol Res. 1998;26:259–264. doi: 10.1007/s002400050054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blass M, Kronfeld I, Kazimirsky G, Blumberg PM, Brodie C. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase Cdelta is essential for its apoptotic effect in response to etoposide. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:182–195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.182-195.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Kraus S, Shahbazian D, Friedberg I, Seger R, Naor Z. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, and c-Src are involved in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit promoter. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2228–2244. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Xie H, Wells A. Mitogenic signaling from the egf receptor is attenuated by a phospholipase C-gamma/protein kinase C feedback mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 1996a;7:871–881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Wang X, Templeton D, Davis RJ, Tan TH. The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in apoptosis induced by ultraviolet C and gamma radiation. Duration of JNK activation may determine cell death and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1996b;271:31929–31936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ, Czech MP. Stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor threonine 654 phosphorylation by platelet-derived growth factor in protein kinase C-deficient human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6832–6841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker LV, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C – a question of specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:73–77. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin-Bekman M, Naidich M, Pawson AJ, Millar RP, Seger R, Naor Z. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) by GnRH is cell-context dependent. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin-Bekman M, Naidich M, Rahamim L, Przedecki F, Almog T, Lim S, Melamed P, Liu P, Wohland T, Yao Z, Seger R, Naor Z. A pre-formed signaling complex mediates GnRH-activated ERK-phosphorylation of paxillin and FAK at focal adhesions in L{beta}T2 gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1850–1864. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin-Bekman M, Rahamin-Ben Navi L, Shterntal B, Sviridonov L, Przedecki F, Naidich-Exler M, Brodie C, Seger R, Naor Z. Differential role of PKC isoforms in GnRH and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Jun N-terminal kinase. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4894–4907. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondi D, Limonta P, Moretti RM, Marelli MM, Garattini E, Motta M. Antiproliferative effects of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists on human androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line DU 145: evidence for an autocrine-inhibitory LHRH loop. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4091–4095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondi D, Moretti RM, Montagnani Marelli M, Pratesi G, Polizzi D, Milani M, Motta M, Limonta P. Growth-inhibitory effects of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists on xenografts of the DU 145 human androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:506–511. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980518)76:4<506::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Ortmann O, Teichert HM, Fassl H, Lohrs U, Kullander S, Kauppila A, Ayalon D, Schally A, Oberheuser F. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist triptorelin in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. A prospective double blind randomized trial Decapeptyl Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Cancer. 1996;78:1452–1460. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961001)78:7<1452::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Ortmann O, Schulz KD, Schally AV. Growth-inhibitory actions of analogues of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone on tumor cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1997;8:355. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(97)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Muller V, Ortmann O, Schulz KD. Effects of LHRH-analogues on mitogenic signal transduction in cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;65:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engedal N, Korkmaz CG, Saatcioglu F. C-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for phorbol ester- and thapsigargin-induced apoptosis in the androgen responsive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Oncogene. 2002;21:1017–1027. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin J, Hislop J, Flynn A, McArdle CA. Signalling and anti-proliferative effects mediated by gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptors after expression in prostate cancer cells using recombinant adenovirus. J Endocrinol. 2003;176:275–284. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1760275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesty-Palmer D, Chen M, Reiter E, Ahn S, Nelson CD, Loomis CR, Spurney RF, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct beta-arrestin and G protein dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundker C, Volker P, Emons G. Antiproliferative signaling of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in human endometrial and ovarian cancer cells through G protein alpha(I)-mediated activation of phosphotyrosine phosphatase. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2369–2380. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YL, Baysal K, Kang B, Yang LJ, Williamson JR. Correlation between sustained c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase activation and apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in rat mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4027–4034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D, Reiss N, Naor Z. Differential activation of protein kinase C delta and epsilon gene expression by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in alphaT3-1 cells. Autoregulation by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13534–13540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai A, Ohno T, Furui T, Takahashi K, Matsuda T, Tamaya T. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulates phospholipase C but not protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in plasma membrane from human epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1993;3:311–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1993.03050311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Dutkowski CM, Barrow D, Harper ME, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI. New EGF-R selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor reveals variable growth responses in prostate carcinoma cell lines PC-3 and DU-145. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:1010–1018. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<1010::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo SS, Yoo YM. Melatonin induces apoptotic death in LNCaP cells via p38 and JNK pathways: therapeutic implications for prostate cancer. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth A, Pinski J, Galvan G, Halmos G, Szepeshazi K, Cai RZ, Groot K, Vadillo-Buenfil M, Schally AV. Inhibition of growth of androgen-independent DU-145 prostate cancer in vivo by luteinising hormone-releasing hormone antagonist Cetrorelix and bombesin antagonists RC-3940-II and RC-3950-II. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri G, Balogh A, Szoke B, Teplan I, Csuka O. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues inhibit cell proliferation and activate signal transduction pathways in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line. Tumour Biol. 1991;12:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa U, Ogita K, Shearman MS, Ase K, Sekiguchi K, Naor Z, Kishimoto A, Nishizuka Y, Saito N, Tanaka C. The family of protein kinase C: its molecular heterogeneity and differential expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1988;53 (Pt 1):97–102. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1988.053.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen J, Aaltonen V, Peltonen J. Protein kinase C (PKC) family in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S, Naor Z, Seger R. Intracellular signaling pathways mediated by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor. Arch Med Res. 2001;32:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(01)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S, Levy G, Hanoch T, Naor Z, Seger R. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells: role of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, protein kinase B, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5736–5744. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S, Naor Z, Seger R. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone in apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;234:109–123. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfeld I, Kazimirsky G, Lorenzo PS, Garfield SH, Blumberg PM, Brodie C. Phosphorylation of protein kinase Cdelta on distinct tyrosine residues regulates specific cellular functions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35491–35498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limonta P, Dondi D, Moretti RM, Maggi R, Motta M. Antiproliferative effects of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists on the human prostatic cancer cell line LNCaP. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:207–212. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1320049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limonta P, Dondi D, Moretti RM, Fermo D, Garattini E, Motta M. Expression of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone mRNA in the human prostatic cancer cell line LNCaP. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:797–800. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.3.8445038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limonta P, Moretti RM, Marelli MM, Dondi D, Parenti M, Motta M. The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptor in human prostate cancer cells: messenger ribonucleic acid expression, molecular size, and signal transduction pathway. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5250–5256. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CR, Chen WS, Lazar CS, Carpenter CD, Gill GN, Evans RM, Rosenfeld MG. Protein kinase C phosphorylation at Thr 654 of the unoccupied EGF receptor and EGF binding regulate functional receptor loss by independent mechanisms. Cell. 1986;44:839–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XH, Wiley HS, Meikle AW. Androgens regulate proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in culture by increasing transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-alpha) and epidermal growth factor (EGF)/TGF-alpha receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1472–1478. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.6.8263129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Austin DA, Webster NJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone-desensitized LbetaT2 gonadotrope cells are refractory to acute protein kinase C, cyclic AMP, and calcium-dependent signaling. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4354–4365. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccario H, Junoy B, Poulin B, Boyer B, Enjalbert A, Drouva SV. Protein kinase Cdelta as gonadotropin-releasing hormone target isoenzyme in the alphaT3-1 gonadotrope cell line. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79:204–220. doi: 10.1159/000078102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamillapalli R, VanHouten J, Zawalich W, Wysolmerski J. Switching of G-protein usage by the calcium-sensing receptor reverses its effect on parathyroid hormone-related protein secretion in normal versus malignant breast cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24435–24447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801738200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, Zhang Q, Tian L, Wang Y, Siddik ZH, Mills GB, Claret FX. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19245–19256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maudsley S, Davidson L, Pawson AJ, Chan R, de Maturana RL, Millar RP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists promote proapoptotic signaling in peripheral reproductive tumor cells by activating a Galphai-coupling state of the type I GnRH receptor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7533–7544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle CA, Franklin J, Green L, Hislop JN. Signalling, cycling and desensitisation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptors. J Endocrinol. 2002;173:1–11. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1730001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles LE, Hanyaloglu AC, Dromey JR, Pfleger KD, Eidne KA. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-mediated growth suppression of immortalized LbetaT2 gonadotrope and stable HEK293 cell lines. Endocrinology. 2004;145:194–204. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti RM, Marelli MM, Dondi D, Poletti A, Martini L, Motta M, Limonta P. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists interfere with the stimulatory actions of epidermal growth factor in human prostatic cancer cell lines, LNCaP and DU 145. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3930–3937. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K, Conklin D, Pawson AJ, Sellar R, Ott TR, Millar RP. A transcriptionally active human type II gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene homolog overlaps two genes in the antisense orientation on chromosome 1q. 12. Endocrinology. 2003;144:423–436. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney JM, Roberson MS. Divergent signaling pathways requiring discrete calcium signals mediate concurrent activation of two mitogen-activated protein kinases by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14182–14189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LO, Blenis J. MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z. Signal transduction mechanisms of Ca2+ mobilizing hormones: the case of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocr Rev. 1990;11:326–353. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-2-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z. GnRH receptor signaling: cross-talk of Ca2+ and protein kinase C. Eur. J Endocrinol. 1997;136:123–127. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1360123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z. Signaling by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR): studies on the GnRH receptor. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:10–29. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z, Zer J, Zakut H, Hermon J. Characterization of pituitary calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase: redistribution by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8203–8207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z, Dan-Cohen H, Hermon J, Limor R. Induction of exocytosis in permeabilized pituitary cells by alpha- and beta-type protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4501–4504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor Z, Benard O, Seger R. Activation of MAPK cascades by G-protein-coupled receptors: the case of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28495–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC. Regulation of protein kinase C. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC. The ins and outs of protein kinase C. Methods Mol Biol. 2003a;233:3–7. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-397-6:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton ACa. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J. 2003;370:361–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992a;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Membrane phospholipid degradation and protein kinase C for cell signalling. Neurosci Res. 1992b;15:3–5. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(92)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhrimenko H, Lu W, Xiang C, Ju D, Blumberg PM, Gomel R, Kazimirsky G, Brodie C. Roles of tyrosine phosphorylation and cleavage of protein kinase Cdelta in its protective effect against tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23643–23652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Maudsley S, Morgan K, Davidson L, Naor Z, Millar RP. Inhibition of human type i gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) function by expression of a human type II GnRHR gene fragment. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2639–2649. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin B, Rich N, Mas JL, Kordon C, Enjalbert A, Drouva SV. GnRH signalling pathways and GnRH-induced homologous desensitization in a gonadotrope cell line (alphaT3-1) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;142:99–117. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz T, Culig Z, Eder IE, Nessler-Menardi C, Bartsch G, Grunicke H, Uberall F, Klocker H. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor blockade inhibits the action of EGF, insulin-like growth factor I, and a protein kinase A activator on the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qayum A, Gullick W, Clayton RC, Sikora K, Waxman J. The effects of gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues in prostate cancer are mediated through specific tumour receptors. Br J Cancer. 1990a;62:96–99. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qayum A, Gullick WJ, Mellon K, Krausz T, Neal D, Sikora K, Waxman J. The partial purification and characterization of GnRH-like activity from prostatic biopsy specimens and prostatic cancer cell lines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990b;37:899–902. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90440-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland ME, Anderson SM, Matassa AA, Barzen KA, Quissell DO. Protein kinase C delta is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19115–19123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealfon SC, Weinstein H, Millar RP. Molecular mechanisms of ligand interaction with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:180–205. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.2.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal-Abramson T, Giat J, Levy J, Sharoni Y. Guanine nucleotide modulation of high affinity gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors in rat mammary tumors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;85:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. Faseb J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham S, Cheifetz MN, Lewy H, Ashkenazi IE, Becker OM, Seger R, Naor Z. Mechanism of GnRH receptor signaling: from the membrane to the nucleus. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1999;60:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham S, Harris D, Ben-Shlomo H, Cohen I, Bonfil D, Przedecki F, Lewy H, Ashkenazi IE, Seger R, Naor Z. Mechanism of GnRH receptor signaling on gonadotropin release and gene expression in pituitary gonadotrophs. Vitam Horm. 2001;63:63–90. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)63003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS, Catt KJ. Novel aspects of GnRH-induced intracellular signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:739–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS, Reinhart J, Catt KJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors: structure and signal transduction pathways. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:462–499. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-4-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillotson JK, Rose DP. Endogenous secretion of epidermal growth factor peptides stimulates growth of DU145 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 1991;60:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner T, Chen P, Goodly LJ, Wells A. EGF receptor signaling enhances in vivo invasiveness of DU-145 human prostate carcinoma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1996;14:409–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00123400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, Gregori G, Hullinger RL, Andrisani OM. Sustained activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways by hepatitis B virus X protein mediates apoptosis via induction of Fas/FasL and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1/TNF-alpha expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10352–10365. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10352-10365.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Satoh A, Warren G. Mapping the functional domains of the Golgi stacking factor GRASP65. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4921–4928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412407200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Souto JC, Solava J, Kassis J, Bailey KJ, Turner T. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist limits DU-145 prostate cancer growth by attenuating epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1251–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CD, Coetsee M, Morgan K, Flanagan CA, Millar RP, Lu ZL. A crucial role for Galphaq/11, but not Galphai/o or Galphas, in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-mediated cell growth inhibition. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2520–2530. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Gonzalez-Guerrico A, Kazanietz MG. PKC-mediated secretion of death factors in LNCaP prostate cancer cells is regulated by androgens. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:187–195. doi: 10.1002/mc.20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Turner T, Wang MH, Singh RK, Siegal GP, Wells A. In vitro invasiveness of DU-145 human prostate carcinoma cells is modulated by EGF receptor-mediated signals. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1995;13:407–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00118180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York RD, Yao H, Dillon T, Ellig CL, Eckert SP, McCleskey EW, Stork PJ. Rap1 mediates sustained MAP kinase activation induced by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1998;392:622–626. doi: 10.1038/33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]