Abstract

Further understanding is needed of the functionalities and efficiency of social media for health intervention research recruitment. Facebook was examined as a mechanism to recruit young adults for a smoking cessation intervention. An ad campaign targeting young adult smokers tested specific messaging based on market theory and successful strategies used to recruit smokers in previous clinical trials (i.e. informative, call to action, scarcity, social norms), previously successful ads, and general messaging. Images were selected to target smokers (e.g., lit cigarette), appeal to the target age, vary demographically, and vary graphically (cartoon, photo, logo). Facebook’s Ads Manager was used over 7 weeks (6/10/13 – 7/29/13), targeted by age (18–25), location (U.S.), and language (English), and employed multiple ad types (newsfeed, standard, promoted posts, sponsored stories) and keywords. Ads linked to the online screening survey or study Facebook page. The 36 different ads generated 3,198,373 impressions, 5,895 unique clicks, at an overall cost of $2,024 ($0.34/click). Images of smoking and newsfeed ads had the greatest reach and clicks at the lowest cost. Of 5,895 unique clicks, 586 (10%) were study eligible and 230 (39%) consented. Advertising costs averaged $8.80 per eligible, consented participant. The final study sample (n=79) was largely Caucasian (77%) and male (69%), averaging 11 cigarettes/day (SD=8.3) and 2.7 years smoking (SD=0.7). Facebook is a useful, cost-effective recruitment source for young adult smokers. Ads posted via newsfeed posts were particularly successful, likely because they were viewable via mobile phone. Efforts to engage more ethnic minorities, young women, and smokers motivated to quit are needed.

Keywords: social media, Facebook, participant recruitment, young adult, tobacco, smoking cessation

1. INTRODUCTION

Studies of tobacco use and other health behaviors have reported great challenges in recruiting young adults.1,2 More successful methods have reached youth in settings where they frequent (e.g., schools, bars/nightclubs), emphasized privacy and flexibility, and made use of peer “informants” to determine recruitment locations.3,4 With the potential for wider reach and greater engagement, social media sites, such as Facebook and Twitter, are widely popular among young adults, and are demonstrating utility in health-related research5. Social media are used most often and by an overwhelming majority of online 18 to 29 year olds (89%), with Facebook alone visited by 70% of young adults on a typical day.6 Social media can meet young adults where they frequent, at any hour of the day, with the potential for private interactions, and the appearance of peer outreach. Further, marketing campaigns on Facebook offer the opportunity to target advertisements by age, location, or keywords, for engaging research participants who meet specific recruitment criteria.

A 2012 review of approximately 20 studies using social media for research recruitment found that social media appears cost-effective, efficient, and successful in engaging a diverse range of individuals.7 In the area of health research, use of Facebook has largely centered on recruitment of adults for cross-sectional surveys. Examples include studies of nutrition education programming with low-income Pennsylvania residents;8 adult therapy preferences;9 adult sexual orientation;10 and birth preferences of pregnant women, with costs of $11.11 per enrollee.11 Intervention studies have used Facebook to recruit Veterans for a web intervention targeting alcohol problems and post traumatic stress disorder symptoms12 and a depression prevention intervention,13 though Facebook’s targeting was found to be too specific and more costly than Google (AUD $11.55 per participant from Google vs. AUD $19.89 per participant from Facebook). One group is using Facebook to implement respondent-driven sampling (Decide2Quit.org); results are forthcoming.14,15 Another group showed that participants recruited to smoking cessation clinical trials through Facebook did not differ from those recruited through more traditional means on smoking characteristics or demographics other than age; Facebook recruits were younger.16

A few studies have reported on Facebook recruitment of young adults; most have been cross-sectional survey studies -- on post-traumatic stress;17 general health;18 sexual health;19,20 tobacco;21 and other substance use22 – with one longitudinal intervention trial, promoting sexual health.23 In a national online survey study of young adult smokers, a Facebook ad campaign reported a cost of $4.28 per valid, completed survey,21 which was more cost-effective than buying ads on other websites ($43 per completed survey) or recruiting via a survey sampling company ($19 per completed survey), and was better targeted with more valid results than free advertisements on Craigslist.24 While Facebook has demonstrated utility as a channel for reaching young adult smokers age 18 to 25, engaging this same group in a cessation intervention is anticipated to be more challenging, given the greater time commitment of longitudinal research and possible expectations inherent in a treatment study.

To provide further understanding of the functionalities and efficiency of social media for health intervention research recruitment, the current study reports on a Facebook ad campaign targeting young adults for a smoking cessation study. This study reports on recruitment methods, time, and cost; examines ad types that were more or less successful; and presents characteristics of the participants ultimately receiving the intervention.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

The study aimed to recruit men and women who were English literate and 18 to 25 years of age, who indicated they go on Facebook 4 or more days per week, and had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lives and currently smoked at least 1 cigarette per day on 3 or more days of the week. Intention to quit was not required for study participation. Access to a camera through phone or computer was required for bioconfirmation of nonsmoking status during the trial. All participants reporting no smoking in the past 7 days at follow-up assessments were sent saliva cotinine test strips and asked to send video or pictures to study staff showing them collecting a saliva sample and the result of the cotinine test.

2.2 Facebook Recruitment Campaign

Using consumer and target (young adult) marketing strategies, and strategies found to be successful in previous recruitment of smokers for clinical trials,25,26 ad content messaging was targeted using the following themes: general/informative (e.g., “Looking for people who smoke. Join and you can get up to $180. Click here to learn more.”); a call to action (e.g., “Smoking Intervention! No matter what your status is, Tobacco Status Project values you! Join & you may get $180”); scarcity (e.g., “UCSF Smoking Research. Only a few spaces left in Tobacco Status Project. Click to see if you are eligible.”); social norms (e.g., “1 in 5 adults smoke. What stat do you want to be? Don't wait! Join the Tobacco Status Project today.); target those motivated to quit (e.g., “Thinking about quitting? Start with the Tobacco Status Project!”); reused from a previous project with young adult smokers21 (e.g., “Smoked recently? Join the UCSF Tobacco Status Project and earn up to $180.”). Images were designed to men and women of different ethnicities, and varied in style (cartoon, photography, study logo). Some ads mentioned the study incentive (up to $180 over 1 year). Our university Internal Review Board approved 21 texts and 22 images and allowed investigators to interchange text and images.

Facebook’s Ads Manager program was used from 6/10/13 – 7/29/13 to create ads to appear either in the “newsfeed” (a streaming list of updates from Facebook connections [“friends”] or advertisers) or right-side (far right column) of a user’s Facebook page. Ad types available at the time of the campaign and used for the present study included:

“Standard” ads: appeared only on the right column of a Facebook page. These ads could link to a study’s Facebook page or an external website;

Newsfeed ads: appeared in a user’s newsfeed, could be viewed on Facebook’s desktop or mobile applications, and could link to either a Facebook page or external website;

Promoted posts: made it more likely that a post would appear in the newsfeed of those who already “like” a page and could be viewed via mobile technology; and

Sponsored stories: targeted Facebook friends of users who liked our study Facebook page and indicated that a user’s Facebook friend had some connection with our page (e.g., “XX commented on/likes Tobacco Status Project’s link”), through right-side or newsfeed posts.

All ads targeted by age (18 to 25), location (U.S.), and language (English). Some standard or newsfeed ads further targeted by “keywords,” or participants’ interests specified in their Facebook profiles. Two sets of keywords were used in our campaign, including “Cigarette,” “Tobacco,” and “Smoking” (broad targeting), or broad targeting keywords and “Nicotine,” “Health effects of tobacco,” and “Electronic cigarette” (specific targeting). Standard and newsfeed ads included a short headline, a picture, a description of the study (up to 90 characters) and a link to the study’s online screening survey conducted through Qualtrics software (external website) or the study’s public Facebook page with information about the study and links to the external screening survey. All ads met Facebook’s advertising size and word count specifications in June 2013.27 Images could not include more than 20% text, and advertising content could not include sale or promotion of alcohol, drugs or tobacco. All ads were reviewed and approved by Facebook staff before they could be run. In some cases, ads were initially rejected by Facebook and needed to be revised before they could be run. This was always due to imaging including more than 20% text, and with small changes to image/text size we were able to get all IRB-approved images approved by Facebook.

A daily spending limit could be specified for each ad and for the entire campaign. The likelihood that a given ad was shown on a target user’s page was determined by an algorithm managed by Facebook that incorporated the ad’s prior success, competition from other ads in the marketplace, the spending limit, and in some cases, whether the user was a friend of someone who already had a connection with our study Facebook page (e.g., Promoted posts, Sponsored stories). Bids could be made for either ad impressions (views by Facebook users) or clicks on an ad, and we only specified paying for clicks in this campaign. The program “optimized” the daily spending limit for each ad throughout the campaign – i.e., ads that yielded more clicks were shown more, in order to maximize clicks throughout the life of the campaign.

It was not possible to link specific ad impressions and clicks to study enrollment. Facebook’s advertising program has a feature called “conversion tracking” that allows advertisers to link clicks on a website (e.g., our consent form) to a specific ad. Though used successfully by our group in the past21, this tracking feature did not function properly in the current evaluation. For example, statistics for a given ad differed extremely when viewed by staff at the same time on two different computers. The Facebook help center was unable to resolve the problem for us during the study recruitment period.

2.3 Study Enrollment & Participation

The Facebook recruitment ads linked to either the study’s public Facebook page, with information and links to a secure external eligibility screener and consent form, or directly to the eligibility screener and consent. In order to be considered “consented,” participants had to indicate willingness to be enrolled in the study for one year, participate in a Facebook group, read an online consent form, and answer three questions correctly about the study and its risks. Eligible and consented participants were then asked to verify their identity through email or Facebook. Participants were then sent a link to the password-protected baseline assessment that included readiness to quit smoking. All those who completed baseline assessments were invited to a “secret” (Facebook’s terminology for private) Facebook group tailored to their Transtheoretical Model28 readiness to quit (Ready to quit, Thinking about quitting, Not ready to quit), and delivered 90 days of Facebook content. These intervention secret groups were entirely independent of the study’s public Facebook page with information about the study itself and how to be assessed for eligibility. Participants were assessed at the end of treatment (3-month follow-up) and 6- and 12-months post-baseline and given up to $130 in gift cards for completing all assessments. Some participants were further randomized to receive a $50 gift card for engaging in the intervention, for a total of $180 possible compensation for study participation.

2.4 Measures

Campaign advertisements were coded in mutually-exclusive categories based on: (a) Image type: single person, social, cigarette-only, or logo; (b) whether smoking was overtly portrayed in the image (yes, no, logo); (c) gender(s) portrayed in the ad: male-only, female-only, mixed gender, or gender-neutral; (d) message-type: general/informative, market-theory based (social norm, threat, scarcity, call to action), previously successful with young adult smokers21 (“Smoke Cigarettes?” Join a UCSF online study about smoking habits. Sign up & earn $130 or more”) or targeting a specific subset of the population (not ready to quit vs. ready to quit and those who already “liked” our page); (e) Facebook ad-type: standard, newsfeed, sponsored stories, promoted posts; (f) timing of ad in campaign: first 3 weeks, second 4 weeks; (g) Facebook placement: right-side, newsfeed; and (h) where the ad linked: study consent page or study Facebook page.

The following variables made available from Facebook were used to evaluate the success of the campaign and individual ads: daily budget (specified by the advertiser), total amount spent on the campaign, duration of the campaign, the estimated audience a given ad could reach based on targeting, total (non-unique) impressions an ad made on users Facebook pages, actual reach of a given ad to unique users, total cost of a given ad, unique clicks, unique click-through rate (unique clicks/unique users who saw an ad), and the average cost per unique click.

In the study’s eligibility screen, one item asked participants how they heard about the study (Facebook ad, study Facebook page, another social networking website, a friend, or other). Baseline measures used to describe our sample included: gender, age, ethnicity, employment and student status, family and personal income, and zip code (used to generate region of residence), measured with a demographic questionnaire used in our prior research.29,30 The Smoking History Questionnaire29,31,32 assessed average days smoking per week and cigarettes per smoking day, age of initiation, lifetime and past year quit attempts, and time to first cigarette upon waking (<30 min or >30 min). The Smoking Stages of Change scale assessed readiness to quit smoking cigarettes28 categorizing smokers into one of three pre-action stages of change: Precontemplation, no intention to quit within the next 6 months; Contemplation, intention to quit within the next 6 months but no 24-hr quit attempt in the past year; and Preparation, intention to quit within the next month and a 24-hr quit attempt in the past year.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

For the overall campaign, the amount spent and length of time needed to enroll and assign the targeted N=48 cases to Facebook groups were calculated. Differences in advertisement characteristics were examined for five metrics deemed most important to evaluate advertisement: reach, total amount spent, unique clicks, unique click-through rate, and cost per unique click. ANOVA and t-tests were run for cost-per-unique-click and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U for two-group tests or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA for >2 group tests) for other variables due to extreme skew. The cost-per-unique click metric was then used to identify individual ads as most successful (lowest third cost per unique click), moderately successful (middle third cost per unique click), or least successful (highest cost per unique click). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the intervention sample.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Ad campaign

In total, 36 ads were run over 7-weeks (see online Supplemental Material for the ads used). They included five different standard ads each week for 3 weeks (15 total); two sponsored stories and three promoted posts in the third week; and in the last 4 weeks, 16 ads with picture/text combinations chosen based on success in the first 3 weeks and desired targeting of smokers who were motivated to quit. Facebook removed the three promoted posts after one day citing “too much text in the image”; advertising metrics were calculated for the short time they ran.

During the seven-week campaign, our ads made 3,198,373 impressions, yielding 5,895 unique clicks at an overall cost of $2,024. The average cost per unique click on an ad was $0.34. Table 1 characterizes the 36 campaign ads by type of messaging, image, and advertising types, and shows features of advertisements that related to Facebook’s advertising metrics. Compared to ads with logos, ads that had images of a cigarette alone, directly portrayed smoking in any way, or portrayed mixed genders reached more unique users. Promoted posts compared to standard ads and ads that linked to our study’s Facebook page rather than the Qualtrics eligibility page also reached more unique users. Newsfeed ads resulted in more unique clicks than promoted posts, and more was spent on newsfeed ads than either promoted posts or standard ads. Higher unique click-through rates were obtained for images of a logo vs. smoking, general messages vs. market theory strategy, and newsfeed ads vs. other ad types and right side ads. Finally, ads with an image of a cigarette averaged a lower cost per unique click than social images. The success of individual ads varied by ad and by Facebook metric. Figure 1a–c illustrates, as an example, two sets of three ads that were deemed highly successful, moderately successful, or unsuccessful based on the metric of cost per unique click.

Table 1.

Characteristics of campaign ads by Facebook advertising metrics (N=36)

| N | Reach | Cost | Unique clicks | UCTR | CUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Z, p | Median | Z, p | Median | Z, p | Median | Z, p | Mean (SD) | F/t, p | ||

| Image type | 15.34, .002a | 2.40, .493 | 4.47, .215 | 6.41, .093 | 2.95, .047b | ||||||

| Single person | 10 | 13375 | 63.29 | 115 | .29 | .47 (.36) | |||||

| Social | 9 | 10232 | 54.25 | 70 | .18 | .66 (.25) | |||||

| Cigarette | 5 | 63553 | 67.21 | 263 | .25 | .25 (.16) | |||||

| Logo | 11 | 2527 | 9.06 | 20 | 1.14 | .57 (.25) | |||||

| Smoking Image | 11.96, .003c | 3.02, .221 | 3.52, .171 | 6.59, .037c | .63, .539 | ||||||

| Smoking | 21 | 21923 | 55.57 | 96 | .24 | .47 (.34) | |||||

| Non-smoking | 4 | 9822 | 62.30 | 119 | .98 | .60 (.15) | |||||

| Logo | 11 | 2527 | 9.06 | 20 | 1.14 | .57 (.25) | |||||

| Gender Image | 10.05, .018d | 7.14, .067 | 6.02, .111 | 7.22, .065 | 1.14, .346 | ||||||

| Neutral | 13 | 3366 | 20.29 | 33 | 1.12 | .54 (.25) | |||||

| Female | 8 | 12864 | 40.31 | 88 | .29 | .36 (.13) | |||||

| Male | 7 | 18649 | 31.01 | 42 | .18 | .63 (.30) | |||||

| Mixed | 8 | 39373 | 72.12 | 119 | .98 | .52 (.43) | |||||

| Text Messaging type | 2.21, .530 | .18, .979 | 1.02, .796 | 8.70, .034e | 1.45, .248 | ||||||

| General | 14 | 8445 | 45.34 | 88 | 1.18 | .48 (.30) | |||||

| Targeted messaging (a-priori) | 8 | 31890 | 54.57 | 83 | .17 | .55 (.25) | |||||

| Previously successful | 6 | 12669 | 38.40 | 113 | .43 | .35 (.14) | |||||

| Designed during campaign | 7 | 18135 | 26.36 | 42 | .30 | .67 (.39) | |||||

| Ad type | 12.95, .005f | 12.91, .005g | 10.46, .015h | 17.73, <.001i | .47, .707 | ||||||

| Standard | 21 | 18135 | 54.25 | 70 | .22 | .50 (.27) | |||||

| Newsfeed | 4 | 20757 | 152.59 | 604 | 2.64 | .54 (.61) | |||||

| Sponsored story | 6 | 4333 | 33.97 | 49 | 1.15 | .63 (.19) | |||||

| Promoted post | 4 | 27704 | 4.82 | 9 | 2.79 | .41 (.26) | |||||

| Ad timing | 105, .092 | 127, .340 | 129, .374 | 189, .324 | 1.51, .227 | ||||||

| First 3 weeks | 15 | 10433 | 54.57 | 96 | .57 | .61 (.25) | |||||

| Last 4 weeks | 21 | 9020 | 9.06 | 23 | .81 | .44 (.32) | |||||

| Ad placement | 2.35, .126 | .70, .402 | .25, .621 | 11.22, .001 | .43, .672 | ||||||

| Right side | 28 | 10433 | 49.84 | 55 | .30 | .52 (.26) | |||||

| Newsfeed | 8 | 4299 | 79.13 | 64 | 2.64 | .47 (.44) | |||||

| Linked to: | 5.65, .017 | .46, .496 | .33, .569 | 1.60, .206 | .29, .772 | ||||||

| Eligibility Page (Qualtrics) | 18 | 7515 | 36.43 | 55 | .85 | ||||||

| Facebook page | 18 | 31977 | 55.57 | 96 | .20 | .53 (.23) | |||||

| Audience | −.06 | .731 | −.13 | .446 | −.10 | .553 | −.19 | .269 | .50 (.37) | ||

Reach is defined as the number of unique users who saw an ad. UCTR=unique click-through rate; CUC=cost per unique click. Tests of group differences with two groups used Mann-Whitney U-test, and more than two-groups used Kruskal-Wallace one-way ANOVA for all variables except for CPUC (ANOVA/t-tests). Significant findings are in bold text.

Significant pairwise comparison: Cigarette vs. Logo

Significant pairwise comparisons: Cigarette vs. Logo; Cigarette vs. Social

Significant pairwise comparison: Smoking vs. Logo

Significant pairwise comparison: Neutral vs. Mixed

Significant pairwise comparison: General vs. Targeted messaging

Significant pairwise comparisons: Promoted posts vs. Standard

Significant pairwise comparison: Promoted posts, vs. Newsfeed; Standard vs. Newsfeed

Significant pairwise comparison: Promoted posts vs. Newsfeed

Significant pairwise comparison: Standard vs. Newsfeed

Figure 1.

Examples of two successful ads (1a), moderately successful ads (1b), and unsuccessful (1c) ads from the Facebook campaign based on the cost per unique click metric. Ad type included Standard, Newsfeed, Sponsored stories, and Promoted posts; Total Reach is the number of unique users who saw an ad; Total Unique Clicks is the number of unique clicks an ad received during the time it was turned on; Unique Click-Through Rate is the number of unique clicks divided by the number of unique users who saw an ad.

3.2 Recruitment results

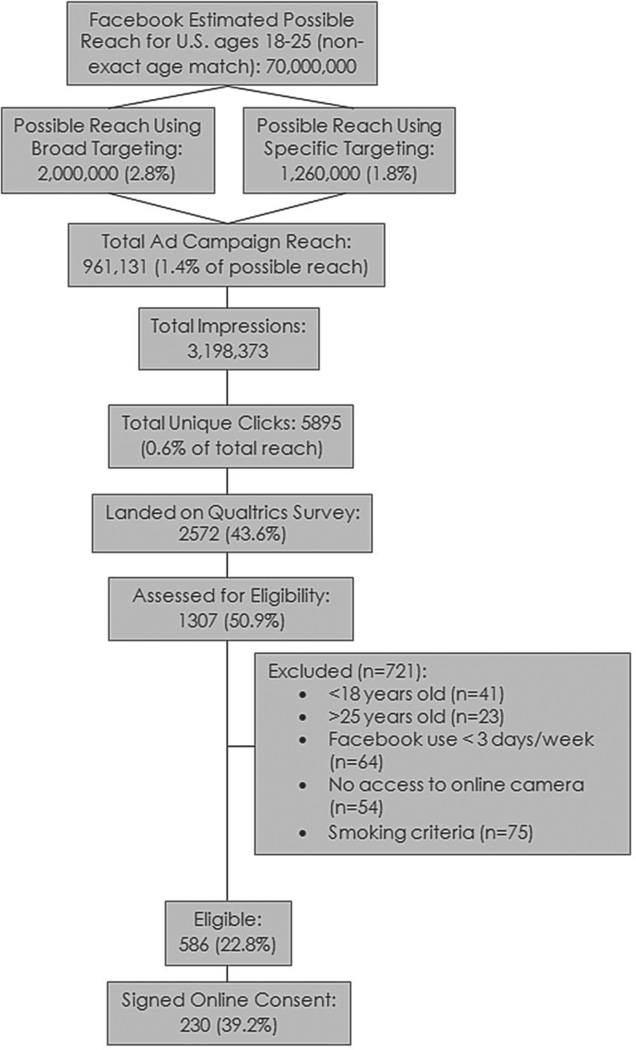

Figure 2 summarizes the numbers of potential Facebook accounts reached through various target characteristics, the clicks our ads received, and the number of consented participants. Of respondents who were assessed for eligibility (n=1307), 86% indicated they heard about the study from a Facebook ad or from our Facebook page (9%), with some respondents hearing about the study from friends (4%), and <1% hearing about it some other way. The final cost of the Facebook ad campaign was $8.80 per eligible, consented participant. Recruitment was so successful in the last two weeks of the campaign that assignment to Facebook intervention groups was made for 79 participants instead of the proposed 48 participants to evaluate usability and feasibility of the intervention.

Figure 2.

Facebook ad campaign reach and recruitment process. Unless otherwise indicated, percentages in each box are the number reported in that box out of the number reported in the box above. Broad targeting included “interests” specified in a Facebook profile including cigarette, tobacco, and smoking. Specific targeting included broad target keywords and additional smoking-related keywords (e.g., nicotine, health effects of tobacco, electronic-cigarette). Excluded participants were either found to be ineligible for reasons listed in the figure or left the online survey before reaching the consent page.

3.3 Participant characteristics

Participants who were assigned to our Facebook group (n=79) were mostly men (79%), Caucasian (89%), and residing in an urban area (90%). All four regions of the US were represented, with the largest group of participants from the Midwest (42%), followed by the West (24%), South (22%, and Northeast (13%). One third attended school full-time (26%) or part-time (12%), and most were either employed full-time (41%) or unemployed but actively looking for work (33%). Most smoked daily (73%), and the sample averaged 11 cigarettes per day on smoking days (SD 8.3) and 2.7 years of smoking (SD 0.7). Participants had a median of 3 lifetime quit attempts. At the time of baseline assessment, stage of change was 42% in precontemplation, 45% in contemplation, and 13% in preparation.

4. DISCUSSION

Overall, this campaign demonstrated Facebook to be an efficient and affordable method for enrolling young adults in a smoking cessation intervention study. At less than $10 per consented participant, this method was less expensive than costs reported in other Internet (not Facebook) advertising used to recruit young adults for survey research ($43 per completed survey).24 Further, other Internet-based recruitment mechanisms that have proven successful at recruiting for smoking cessation interventions, such as Google’s AdWords program,33,34 are not as easy to target to a specific demographic population, resulting in the need to screen participants thoroughly. Given minimal cost for staff time to run a Facebook advertising campaign (less than one hour per day campaign was running), and the ability to target specific study populations by location, demographics, or keywords, this strategy shows great promise for other areas of clinical trial research.

Advertisement features that were most related to metrics of ad success included images of cigarettes (high reach), study logo, and general information messaging (high unique click-through rate). Given the small amount of space given for images and text across all types of Facebook ads, complex images (e.g., multiple people) and sophisticated targeted messaging may have clouded the main study message or confused users. Overt images may be complicated in studies of stigmatized or illegal behaviors (risky sexual behavior, other drug use) because Facebook may not approve the ads. Simplicity, however, seems important for any campaign. Additionally, newsfeed ads were more successful than other ad types or placement (right side) on almost all metrics. This speaks to the importance of designing ads that can be viewed on mobile phones, especially to target young, non-White, and low-income users who are most likely to access the Internet only using a cell-phone.35 Finally, ads that linked to the study’s public Facebook page had wider reach than those linking directly to our eligibility screener but were not successful on any other metric, suggesting that mixing links could maximize campaign reach and efficiency. There were no differences on any ad campaign metrics between ads run during the first 3 weeks and those run in the second 4 weeks, suggesting our strategy of basing later ads on success of early ads was not successful, or that other ad features were more prominent predictors of reach, cost, and click metrics.

The high proportion of smokers unmotivated to quit who enrolled in our study is consistent with our survey research using Facebook for recruitment,21 and further demonstrates that treatment models not requiring cessation are particularly appropriate with this population. Motivational tailoring is built into the design of the intervention for which this campaign recruited, and main outcomes will be reported elsewhere.

One potential limitation of using Facebook for recruitment relates to representativeness of a study sample. For example, the final sample that was assigned to a Facebook intervention group was more predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian urban-residing men than typical users of social media6 or the American young adult smoking population reported in previous surveys.36 Some intervention or study design features may have appealed more to Caucasian men than other socio-demographic groups. Future studies could employ campaigns on Twitter or other social media websites that, while used less often overall than Facebook, appeal strongly to ethnic minorities including African Americans.37 Facebook’s advertising program allows for targeting based on gender and location (including zip code) that could be employed to more-directly target non-Caucasian, women, and rural-residing young people in future campaigns. Unfortunately we were unable to evaluate the demographic characteristics of those who clicked on ads (data unavailable from Facebook) with those who enrolled in the study. However, the large majority of online young adults in the US are currently using Facebook (84%), without difference in use by ethnicity or urban/rural residence; and the lowest-income Internet users are more likely to use Facebook than those with the highest income.37 Facebook is an efficient and cost-effective way to reach a very large national sample of young adults in a short amount of time. Further, our study (and its recruitment advertisements) offered compensation of up to $180 for participation, limiting generalizability to studies without such compensation. Lastly, Facebook’s conversiontracking feature could not be used to determine which advertisements led to enrolled participants. Thus metrics used here only dealt with advertisement reach, clicks, and cost, rather than specific links to study enrollment. Although efforts were made by study staff, we were unable to resolve this issue during the 7-week campaign. Since the campaign was run, Facebook has changed its Ads Manager program, including making conversion tracking more prominent and presumably easier (although this has not been verified by these authors).38 Future Facebook campaigns should make all efforts to incorporate conversion tracking to evaluate links between specific ads and study eligibility and enrollment.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Using Facebook for intervention study recruitment with young adults, this study built upon strategies learned in previous experience and benefited from testing a wide range of marketing strategies targeted to the study population. Particular utility was found in targeting more directly mobile users by buying a greater proportion of newsfeed ads, and focusing on simple (yet obvious) images and messaging. Future investigations should examine systematic comparisons of different advertising types and messages, and compare paid and unpaid Facebook advertising campaigns. Given that young adults are increasingly conducting daily communications online, rather than face-to-face or telephone, traditional methods of recruitment and assessment are increasingly obsolete. Researchers desiring to reach young adults for recruitment and to change health behaviors (especially stigmatized behavior) should consider social media as a viable option for recruitment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Facebook used to recruit young adults to a smoking cessation intervention.

36 ads generated 5,895 unique clicks, at $2,024 ($0.34/click), $8.80 per eligible, consented participant.

Images of smoking and newsfeed ads had the greatest reach and clicks at the lowest cost.

Facebook can be a useful, cost-effective recruitment source for young adult smokers.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant numbers K23 DA032578 and P50 DA09253; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004; National Institute of Mental Health grant number R01 MH083684; and the State of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program grant number 21BT-0018. We thank Shivali Gupta for assisting with coding advertisements for analysis. We thank Jocel Dumlao and Giuseppe Cavaleri for survey design.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement: All authors declare no completing interests associated with this study.

Financial Disclosures: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Bost ML. A descriptive study of barriers to enrollment in a collegiate health assessment program. J. Community Health Nurs. 2005;22(1):15–22. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies J, McCrae BP, Frank J, et al. Identifying male college students’ perceived health needs, barriers to seeking help, and recommendations to help men adopt healthier lifestyles. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2000 May;48(6):259–267. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalkhoran S, Neilands TB, Ling PM. Secondhand smoke exposure and smoking behavior among young adult bar patrons. Am. J. Public Health. 2013 Nov;103(11):2048–2055. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg CJ, Nehl E, Sterling K, et al. The development and validation of a scale assessing individual schemas used in classifying a smoker: implications for research and practice. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2011 Dec;13(12):1257–1265. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold J, Pedrana AE, Sacks-Davis R, et al. A systematic examination of the use of online social networking sites for sexual health promotion. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:583. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duggan M, Brenner J. The Demographics of Social Media Users - 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. Available from: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-media-users.aspx,. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan GS. Online social networks for patient involvement and recruitment in clinical research. Nurse Res. 2013;21(1):35–39. doi: 10.7748/nr2013.09.21.1.35.e302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohse B, Wamboldt P. Purposive facebook recruitment endows cost-effective nutrition education program evaluation. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2(2):e27. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers VL, Griffin MQ, Wykle ML, Fitzpatrick JJ. Internet versus face-to-face therapy: emotional self-disclosure issues for young adults. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009 Oct;30(10):596–602. doi: 10.1080/01612840903003520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vrangalova Z, Savin-Williams RC. Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012 Feb;41(1):85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arcia A. Facebook Advertisements for Inexpensive Participant Recruitment Among Women in Early Pregnancy. Health Educ. Behav. 2013 Sep 30; doi: 10.1177/1090198113504414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brief DJ, Rubin A, Keane TM, et al. Web intervention for OEF/OIF veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013 Oct;81(5):890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0033697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan AJ, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ. Internet-based recruitment to a depression prevention intervention: lessons from the Mood Memos study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e31. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadasivam RS, Volz EM, Kinney RL, Rao SR, Houston TK. Share2Quit: Web-Based Peer-Driven Referrals for Smoking Cessation. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2(2):e37. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadasivam RS, Cutrona SL, Volz E, Rao SR, Houston TK. Web-based peer-driven chain referrals for smoking cessation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2013;192:357–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frandsen M, Walters J, Ferguson SG. Exploring the viability of using online social media advertising as a recruitment method for smoking cessation clinical trials. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2014 Feb;16(2):247–251. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu JL, Snider CE. Use of a social networking web site for recruiting Canadian youth for medical research. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013 Jun;52(6):792–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed N, Jayasinghe Y, Wark JD, et al. Attitudes to Chlamydia screening elicited using the social networking site Facebook for subject recruitment. Sex Health. 2013 Jul;10(3):224–228. doi: 10.1071/SH12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young EJ, Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, et al. Measuring effectiveness of the cervical cancer vaccine in an Australian setting (the VACCINE study) BMC Cancer. 2013;13:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Johns MM, Glowacki P, Stoddard S, Volz E. Innovative recruitment using online networks: lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Sep;73(5):834–838. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen P, Gold J, Pedrana A, et al. Sexual health promotion on social networking sites: a process evaluation of The FaceSpace Project. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013 Jul;53(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reaching young adult smokers through the Internet: Comparison of three recruitment mechanisms. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2010;12(7):768–775. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnoll RA, Cappella J, Lerman C, et al. A novel recruitment message to increase enrollment into a smoking cessation treatment program: preliminary results from a randomized trial. Health communication. 2011 Dec;26(8):735–742. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.566829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Free CJ, Hoile E, Knight R, Robertson S, Devries KM. Do messages of scarcity increase trial recruitment? Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2011 Jan;32(1):36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Facebook. Facebook Advertising Guidelines. [Accessed 23 June, 2013];2013 https://http://www.facebook.com/ad_guidelines.php. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change for smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, et al. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Public Health. 2006 Oct;96(10):1808–1814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of self-reported smoking in an anonymous online survey with young adults. Health Psychol. 2011 May 16;30(6):693–701. doi: 10.1037/a0023443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramo DE, Delucchi K, Hall SM, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Marijuana and tobacco co-use in young adults: Patterns use and thoughts about use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(2):301–310. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramo DE, Delucchi K, Liu H, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Young adults who smoke tobacco and marijuana: Analysis of thoughts and behaviors. Addict. Behav. 2014;39(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon JS, Akers L, Severson HH, Danaher BG, Boles SM. Successful participant recruitment strategies for an online smokeless tobacco cessation program. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S35–S41. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz RF, Barrera AZ, Delucchi K, Penilla C, Torres LD, Perez-Stable EJ. International Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 year. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2009;11(9):1025–1034. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duggan M, Smith A. Cell Internet Use 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. Sep 16, Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Cell-Internet.aspx,. [Google Scholar]

- 36.King B, Dube S, Kaufmann R, Shaw L, Pechacek T. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged >18 years-United States, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2011;60(35):1207–1212. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6035.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duggan M, Smith A. Social Media Update 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. Sep 16, http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Cell-Internet.aspx,. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Facebook. How does conversaion tracking work? [Accessed 8 May, 2014];2014 https://http://www.facebook.com/help/288926164560357?sr=1&sid=0HB3eBlA2Jh9sfnro. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.