Abstract

Background

Obesity in women of childbearing age is increasing at an alarming rate. Growing evidence shows that maternal obesity induces detrimental effects on offspring health including pre-disposition to obesity. We have shown that maternal obesity increases fetal intramuscular adipogenesis at mid-gestation. However, the mechanisms are poorly understood. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulate mRNA stability. We hypothesized that maternal obesity alters fetal muscle miRNA expression, thereby influencing intramuscular adipogenesis.

Methods

Non-pregnant ewes received a control diet (Con, fed 100% of NRC recommendations, n = 6) or obesogenic diet (OB; 150% NRC recommendations, n = 6) from 60 days before to 75 days after conception when the fetal longissimus dorsi (LD) muscle was sampled and miRNA expression analyzed by miRNA microarray. One of miRNAs with differential expression between Con and OB fetal muscle, let-7g, was further tested for its role in adipogenesis and cell proliferation in C3H10T1/2 cells.

Results

A total of 155 miRNAs were found with a signal above 500, among which, 3 miRNAs, hsa-miR-381, hsa-let-7g and bta-miR-376d, were differentially expressed between Con and OB fetuses, and confirmed by QRT-PCR analyses. Reduced expression of miRNA let-7g, an abundantly expressed miRNA, in OB fetal muscle was correlated with higher expression of its target genes. Over-expression of let-7g in C3H10T1/2 cells reduced their proliferation rate. Expression of adipogenic markers decreased in cells over-expressing let-7g, and the formation of adipocytes was also reduced. Over-expression of let-7g decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines.

Conclusion

Fetal muscle miRNA expression was altered due to maternal obesity, and let-7g down-regulation may enhance intramuscular adipogenesis during fetal muscle development in the setting of maternal obesity.

Keywords: Maternal obesity, fetus, skeletal muscle, microRNA, adipogenesis, let-7g, muscle, adipocyte

Introduction

Obesity is now an epidemic in the United States, with more than one third of the population age 20 or older are obese (2007–2008) including women of child bearing age1. Associated with the prevalence of obesity in adults, nearly 17% of children and teenagers aged 2–19 years old are obese2. Maternal obesity caused by high-energy diets increases the risk of obesity in offspring3, 4. Skeletal muscle is one of the principal sites for glucose and fatty acid utilization and comprises 40 to 45% of body mass in adults5. In precocial species, the embryo-fetal period is crucial for skeletal muscle development, because no net increase of muscle fiber numbers occurs after birth6. Muscle cells and adipocytes are both derived from mesenchymal stem cells7, and myogenesis and adipogenesis are considered to be competitive processes since inhibition of adipogenesis promotes myogenesis8, 9. Fetal adipogenesis begins around mid-gestation, a stage of development which partially overlaps with secondary myogenesis10. We have conducted a series of studies using the pregnant sheep as a model and show that maternal obesity enhances intramuscular adipogenesis during fetal skeletal muscle development11–14, leading to altered muscle properties in offspring sheep15. However, the detailed mechanisms remain poorly understood.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are single-stranded RNA molecules 21–23 nucleotides in length, which play a crucial role in developmental processes by regulating expression of target genes, many of which govern cell proliferation and differentiation16, 17. It has been estimated that about 30% of all protein-coding genes are regulated by miRNAs18.

Based on our previous observations that myogenesis was impaired while adipogenesis was elevated in fetal muscle of obese sheep by mid-gestation12–14, we hypothesized that maternal obesity altered miRNA expression in fetal muscle, which may play an important role in adipogenic differentiation during fetal muscle development.

Following miRNA screening we identified three miRNAs that were differentially expressed. Of particular interest in relation to adipogenesis was the observation of lower let-7g in OB compared to Con fetal muscle. MiRNA let-7 was first discovered in C. elegans where it was shown to regulate development, cellular proliferation and differentiation19. Shortly after, let-7 was found in other species and conserved from mollusks to vertebrates20. Numerous studies have been conducted on let-7 and 13 different members of the human let-7 family have been identified on 9 different chromosomes21. Let-7g has been reported to be related to colon cancer22, and subsequently shown to repress the growth of lung cancer cells17 and lung tumor development16. Because of the similarity between cancer cells and stem cells, it has been suggested that there may be similar regulatory signaling by let-7g in stem cells23

We found that reduced expression of miRNA let-7g in OB fetal muscle was correlated with higher expression of its target genes and that over-expression of let-7g in C3H10T1/2 cells reduced their proliferation rate, expression of adipogenic markers, adipocyte formation and expression of inflammatory cytokines. For the first time, our data indicate that let-7g inhibits adipogenesis.

Materials and methods

Care and use of animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Wyoming Animal Care and Use Committee. From 60 days before conception to day 75 of gestation (Day of mating = day 0; Term 150 days), multiparous Rambouillet/Columbia ewes were fed either a highly palatable diet of 100% National Research Council (NRC) recommendations (control, Con; n=6)) or an obesogenic diet of 150% NRC recommendations (OB; n=6) on a metabolic body weight (BW) basis (BW0.75)12. All ewes were weighed at weekly intervals and rations adjusted for weight gain, and body condition scored at monthly intervals to evaluate changes in fatness. A body condition score of 1 (emaciated) to 9 (obese) was assigned by two trained observers after palpation of the transverse and vertical processes of the lumbar vertebrae (L2 through L5) and the region around the tail head24. There was no difference in body weight and body condition score before dietary treatments; after 60 days of treatments, both body weight and body condition score were much higher in OB group than in Con group12.

Following a 12h over-night fast, fourteen pregnant sheep (7 Con and 7 OB) were weighed on day 75 of gestation (term 150 days). Sheep were sedated with intravenous ketamine (10 mg/Kg) and general anesthesia was induced and maintained by isoflurane inhalation. The abdomen and uterus were opened and fetuses were quickly removed to obtain weight and length, and the longissimus dorsi (LD) muscle on both sides was immediately collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for analysis. Fetuses from five twin pregnant ewes in each group were selected for further analyses. Though no difference in weight was observed among fetuses of different sexes, the sex of fetuses in each group was balanced. The fetal weight was 268 ± 12 versus 374 ± 10 g (Con versus OB), while the weight of LD muscle was 2.40 ± 0.16 versus 3.46 ± 0.20 g (Con versus OB)12.

MiRNA microarray analysis

miRNA was extracted from the LD muscle of three fetuses of average body weight in each treatment using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and purified by a miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified miRNA was then sent for miRNA microarray analysis (LC Sciences, Houston, TX) based on all known miRNAs of human, rat, mouse, cattle and sheep. Briefly, Con and OB miRNA were labeled with green and red fluorescent dyes respectively. Then, labeled miRNA was applied to an uParaFlo microfluidics chip (Custom Microarray Platform) for hybridization, microarray scan and data extraction. A locally-weighted regression method was used for data normalization which was performed by LC Sciences.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total mRNA was extracted from the fetal LD muscle or C3H10T1/2 cells using TRI reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNAs were used for real-time PCR analyses using a SYBR Green RT-PCR kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Primers used for sheep samples were: follistatin (FST) forward, 5’-GGCTCCGCCAAGCAAAGA-3’, and reverse, 5’-CGTTGAAAATCATCCACTT-3’; tumor necrosis factor receptor super family, member 4 (TNFRSF4) forward, 5’-GCCCACCAGGACATTTCTC-3’, and reverse, 5’-GGCGTCCGAGCTGCTATT-3’; interleukin (IL)-6 forward, 5’-TCATCCTGAGAAGCCTTGAGA-3’, and reverse, 5’-TTTCTGACCAGAGGAGGGAAT-3’; and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) forward, 5’-ACACCATGAGCACCAAAAGC-3’, and reverse, 5’-AGGCACAAGCAACTTCTGGA-3’. Mouse primer sets used were: FST forward, 5’-CCGCCAAGCAAAGAACGGCC-3’, and reverse, 5’-GGGCGCCCCCGTTGAAAATC-3’; TNFRSF4 forward, 5’-GCAGGACAGCGGCTACAAGC-3’, and reverse, 5’-GTGGCGGGTCTGCTTTCCAG-3’; Cyclin D1 forward, 5’-GCGTACCCTGACACCAATCT-3’, and reverse, 5’-ATCTCCTTCTGCACGCACTT-3’; Cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) forward, 5’-CTAGCTCGCGGCCTGTGTCTA-3’, and reverse, 5’-AGCAGGGGATCTTACGCTCGG-3’; proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) forward, 5’-TAGTCGCCACAACTCCGCCAC-3’, and reverse, 5’-CGTCCCAGCAGGCCTCATTGA-3’; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ forward, 5’-GCCTGCGGAAGCCCTTTGGT-3’, and reverse, 5’-CAGCAAGCCTGGGCGGTCTC-3’; CCAAT-enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) forward, 5’-GGTACGGCGGGAACGCAACA-3’, and reverse, 5’-GAAGATGCCCCGCAGCGTGT-3’; tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) forward, 5’-TGGGACAGTGACCTGGACTGT-3’, and reverse, 5’-TTCGGAAAGCCCATTTGAGT-3’25; interleukin 6 (IL6) forward, 5’-GCTGGTGACAACCACGGCCT-3’, and reverse, 5’-AGCCTCCGACTTGTGAAGTGGT-3’. The 18S RNA was used as a control, forward, 5’-TTGTACACACCGCCCGTCGC-3’, and reverse, 5’-CTTCTCAGCGCTCCGCCAGG-3’. PCR conditions were as following: 20 sec at 95 °C, 20 sec at 58°C, and 20 sec at 72 °C for 35 cycles. After amplification, a melting curve (0.01 C/sec) was used to confirm product purity. Data were expressed relative to 18S rRNA as previously described11.

Cell culture

C3H10T1/2 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in maintaining medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics at 37 °C26. Medium was changed every 72 h. HEK 293T cells were purchased from GenHunter Corporation (Nashville, TN) and maintained in the same medium as C3H10T1/2 cells.

Plasmids

All plasmids were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA), which include pCMV-VSV-G (Cat. 8454), pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr (Cat. 8455), Puro.let-7g.Cre (Cat. 17409), Puro.let-7gsm.Cre (Cat. 17410) and GFP.Cre empty vector (Cat. 20781). Plasmids were recovered in LB medium for 16 h at 30 °C, and DNA was extracted using a QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and dissolved in sterile TE buffer. DNA concentration was measured by Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo scientific, Wilmington, DE) and plasmid DNA was adjusted to a concentration of 200 ng/µl.

Lentivirus production and infection

One day before transfection, 1.5 × 105 HEK293T cells were seeded in a 60-mm plate. Transfection was conducted using FuGENE transfection reagent following the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, plasmid DNA was added at a ratio of 10:5:1 (2 µg of target plasmid, 1 µg of pCMV-dR8.2 dvprm, and 200 ng of pCMV-VSV-G). The ratio of total DNA to FuGENE was 4:1. DNA and transfection reagent were mixed for 10 min and the mixture added dropwise to cells. The transfection lasted for 24 h and, the expression of GFP was examined under a fluorescence microscope. Viruses were collected at 48, 72, 96 h after transfection. The collected viral supernatant was filtered through a syringe with 0.45 µm filter and then concentrated with a Lenti-XTM concentrator (Cat. 631231, Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The titer of lentivirus was estimated by using a Lenti-XTM GoStixTM kit (Cat. 631243, Clontech). A titer of approximately 106 infection units (IFU)/ml was reached after concentration. The viral infection of C3H10T1/2 cells was performed with 8–10 µg/ml polybrene and approximately 105 IFU of lentivirus for 24 h. C3H10T1/2 cells were left to recover for at least 48 h before puromycin was used to select drug resistant cells. The selection was continued for 2 weeks.

Cell proliferation analysis

Cell proliferation rate was measured by using a CyQUANT® NF Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Cat. C35007, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Adipogenic differentiation

Adipogenic differentiation was induced as described previously with minor changes27. Briefly, C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded to 20% confluence and treated with 10 µM 5′-azacytidine for 3 days to demethylate genomic DNA and induce multipotency. After reaching confluence, cells were grown in adipogenic medium (5 µg/ml insulin, 1 µg/ml dexamethazone, 27.8 µg/ml isobutylmethylaxanthine and 10 µM troglitazone) for 3 days, and then the above step was repeated once. Following which the medium was changed to DMEM medium supplemented with insulin only (5 µg/ml) for 2 days, and this step was repeated once26, 28–30.

Oil-Red O staining

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed with 60% ethanol and stained with 0.2% (w/v) Oil-Red O in 60% ethanol (Sigma Chemical Co., Saint Louis, MO) for 10 min as described previously26. Then, cells were destained with 60% ethanol for 5 min and used for microscopic observation.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was conducted as previously described, and data were normalized to tubulin11. Antibodies against PPARγ (Cat. No. 2443) and CEBPα (Cat. No. 2295) were purchased from cell signaling (Danvers, MA), and tubulin antibody from Sigma (Cat. No. T4026).

Vector construction and luciferase assay

Expression vector was constructed as described previously31. Briefly, a 1086 bp 3’ UTR fragment of FST gene containing the predicted hsa-let-7g binding site was amplified and subcloned into the Xbal site of the pGL3-control luciferase vector (Cat. No. E1741, Promega, Madison, WI). The primer sequences used for amplification were (Xbal sites are in bold): forward 5'-GCTCTAGAACTCTCCACCAATGTTCAGTG-3' and reverse 5'-GCTCTAGATGCACATTTACATGGTAG-3'. The construct was verified by Xbal digestion and sequencing.

The luciferase assay was performed as previously reported31, 32. Briefly, C3H10T1/2 cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre or Puro.let-7gsm.Cre were seeded at 50,000 cells per well in a 12-well plate the day before transfection. These cells were cotransfected with 400 ng of pGL3-control luciferase vector and 50 ng of Renilla luciferase vector. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). The Renilla luciferase activity served as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted according to our previous studies in sheep6, 11, 33 and cultured cells32. Briefly, each animal was considered as an experimental unit. Data were analyzed as a complete randomized design using GLM (General Linear Model of Statistical Analysis System, SAS, 2000). The differences in the mean values were compared by the Tukey’s multiple comparison, and mean ± standard errors of mean (SEM) were reported. Statistical significance was considered as P < 0.05 for cell culture studies. For miRNA analyses in fetal muscle, however, due to the limited sample size (three samples in each treatment), P < 0.10 was considered as significant.

Results

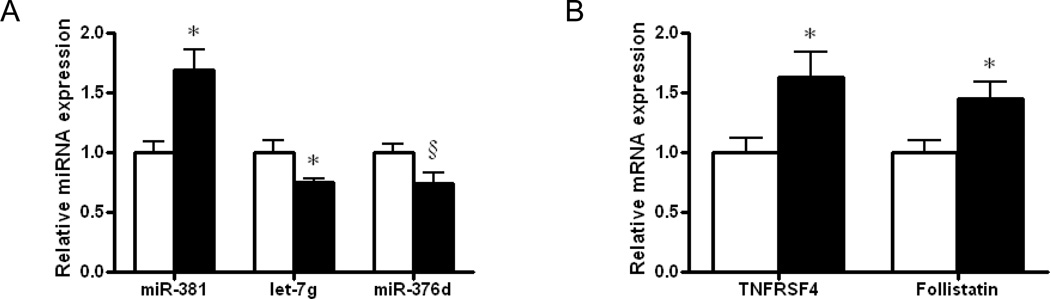

MiRNA Expression in Fetal Muscle

We first analyzed miRNA expression in muscle from fetuses of both control and obese mothers using the miRNA microarray (Supplemental Table 1). To our knowledge, this is the first time to thoroughly analyze the expression of miRNAs in fetal sheep. Of 1030 miRNAs tested, 155 were expressed in sheep fetal muscle (signals > 500). Among these 155 miRNAs, 3 were differentially expressed in fetal muscle of control and obese mothers, which are hsa-miR-381, hsa-let-7g and bta-miR-376d (P < 0.10, Table 1, Figure 1A). Besides, three other miRNAs with signals less than 500 were also differentially expressed (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 1). We then confirmed the expression level of those miRNAs using quantitative RT-PCR. For those three miRNAs expressed at relatively high levels, the results were pretty consistent. The expression miR-381 was 67.0 ± 17.6% higher in OB compared with control fetal muscle (P < 0.05, Figure 1A), while the expression of let-7g and miR-376d was lower in the OB group (24.6 ± 3.3% and 26.0 ± 8.8% respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 1A). There were no significant differences between the two groups of fetuses for those three miRNAs expressed at low levels (P > 0.10, Supplemental Figure 2). We focused on miRNA let-7g, since its expression level was much higher than other two miRNAs with differential expression (Table 1) and its reported role in carcinogenesis, a process related to stem cell proliferation and differentiation which likely has a role in adipogenic differentiation.

Table 1.

MiRNAs differentially expressed between Con and OB fetal skeletal muscle

| MicroRNA | Con | OB | Log2 (OB/Con) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsa-let-7g | 23,060 ± 106 | 21,379 ± 433 | −0.12 | 0.066 |

| Hsa-miR-381 | 2,367 ± 46 | 3,306 ± 93 | 0.50 | 0.002 |

| Bta-miR-376d | 6,991 ± 178 | 4,835 ± 583 | −0.52 | 0.091 |

| Hsa-let-7b | 63 ± 2 | 83 ± 5 | 0.38 | 0.04 |

| Hsa-miR-1306 | 36 ± 1 | 30 ± 2 | −0.32 | 0.10 |

Three muscle samples of fetuses at average body weight within each group were used for microRNA microarray analyses (n = 3) based on all known miRNAs of human, rat, mouse, cattle and sheep.

Figure 1.

Expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) and potential targets of miRNA let-7g in fetal LD muscle of obese (OB ■) versus control sheep (Con □). A) Quantitative real time PCR showed higher expression of miR-381, but less let-7g and miR-376d in OB fetal muscle than in Con muscle. B) mRNA expression of tumor necrosis factor receptor super family, member 4 (TNFRSF4) and follistatin (FST) were increased in OB compared with Con fetal muscle, both are potential targets of hsa-let-7g. C) mRNA expression of TNFα and IL-6 were higher in OB compared with Con fetal muscle (*P < 0.05, §P < 0.10 when compared with Con; Mean ± SEM; n = 10 in Con and n=10 in OB group).

We then analyzed the mRNA expression of two potential target genes of let-7g, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 4 (TNFRSF4) and follistatin (FST), which were both higher in OB fetal muscle (increased by 63.0 ± 21.6% and 45.2 ± 13.6% respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 1B).

To order to identify whether there was a change in the expression of inflammatory cytokines in Con and OB tissues, we further analyzed TNFα and IL-6 mRNA expression, both of which were higher in OB compared to Con tissue (P < 0.05, Figure 1C), indicating inflammatory response in OB fetal muscle.

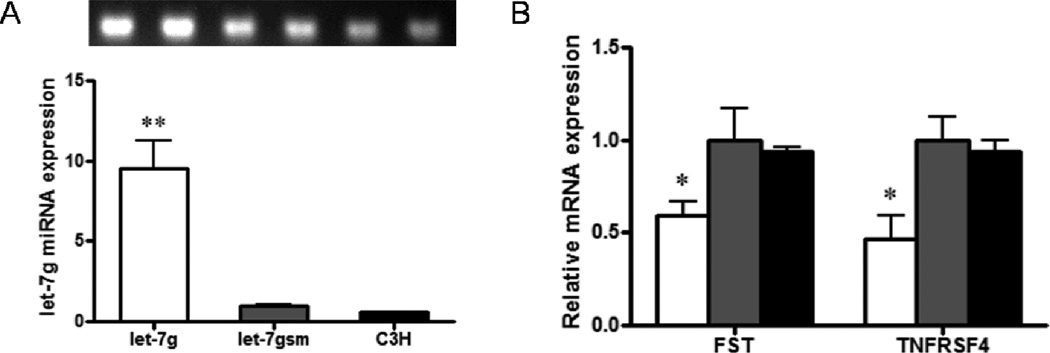

Effect of Let-7g on Expression of Potential Target Genes

We over-expressed let-7g in mesenchymal stem cell line C3H10T1/2 cells using a lentiviral system. To test the efficiency of transfection, we included a GFP empty vector in the lentiviral system, which showed an above 90% transfection and transduction efficiency (Supplemental Figure 3). In cells transfected with lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre, the expression level of let-7g was much higher in over-expressed cells compared with non-treated cells as well as cells infected with a plasmid carrying scrambled sequence (P < 0.01, Figure 2A). We next evaluated the effects of let-7g over-expression on target gene expression; both FST and TNFRSF4 mRNA levels were decreased after let-7g over-expression (40.3 ± 7.0% and 53.5 ± 13.2% lower respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 2B), consistent with the data obtained in fetal sheep muscle in vivo.

Figure 2.

Let-7g, FST and TNFRSF4 expression in stably selected C3H10T1/2 cells. A) Let-7g expression in C3H10T1/2 cells infected with lentiviral plasmids Puro.let-7g.Cre (□), Puro.let-7gsm.Cre ( ), and C3H10T1/2 cells without infection (■); cells infected with Puro.let-7gsm.Cre used as control. B) Let-7g over-expression reduced the mRNA expression of FST and TNFRSF4. (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 when compared with let-7gsm; Mean ± SEM; n = 4).

), and C3H10T1/2 cells without infection (■); cells infected with Puro.let-7gsm.Cre used as control. B) Let-7g over-expression reduced the mRNA expression of FST and TNFRSF4. (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 when compared with let-7gsm; Mean ± SEM; n = 4).

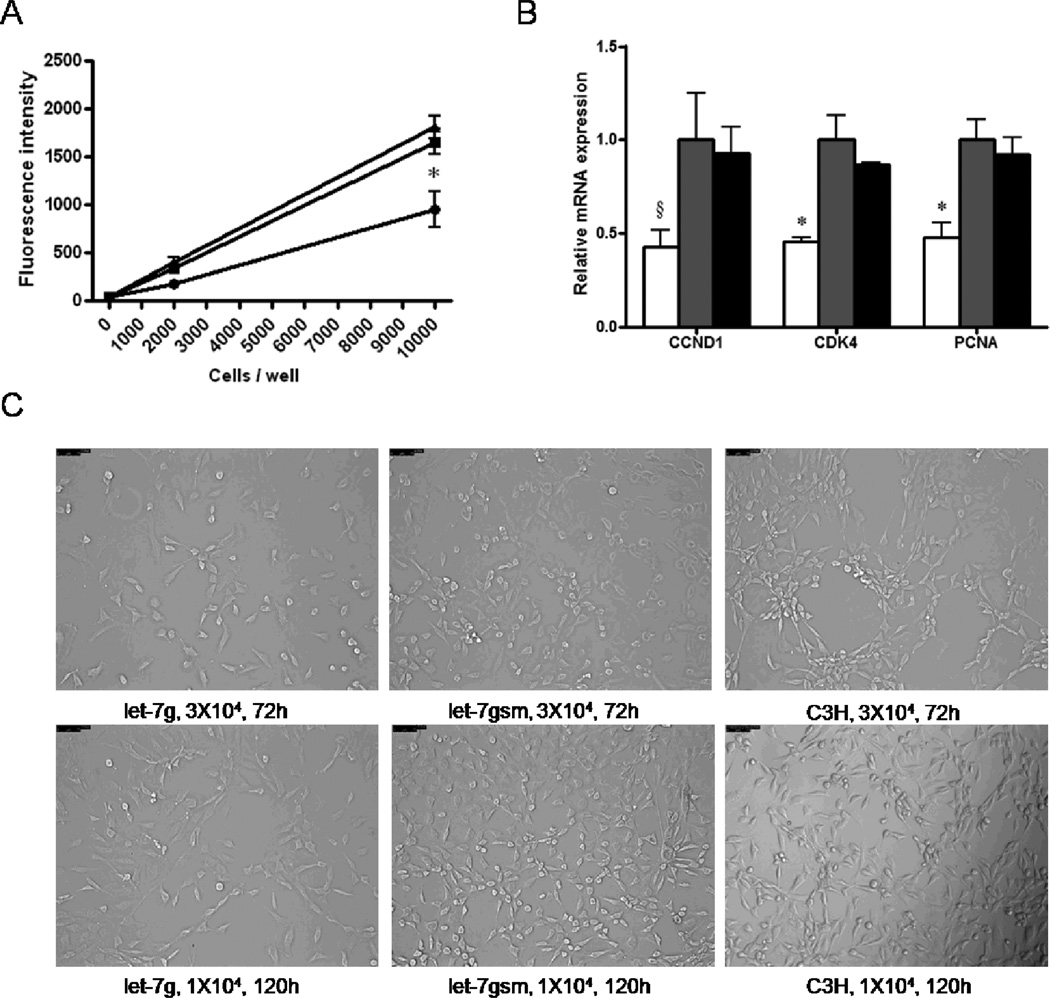

Effect of let-7g on the Proliferation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

C3H10T1/2 cells infected with let-7g grew much slower than control cells, with the cell proliferation rate only 57.3 ± 11.1 % of control cells (P < 0.05, Figure 3A). In addition, several genes related to cell proliferation, including cyclin D1, CDK4 and PCNA, were all lower in let-7g over-expressed cells (57.3 ± 9.1%, 54.6 ± 2.4%, and 52.3 ± 8.3% lower for let-7g, scrambled, and control cells respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 3B), further supporting the role of let-7g in cell proliferation. We then plated the same amount of cells in 6-well plates, and after 72 and 96 h, the density of cells was different in cells infected let-7g compared with non-infected and scrambled infected cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Let-7g suppresses the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. A) Cell proliferation rate was lower in C3H10T1/2 cells infected with lentiviral plasmids Puro.let-7g.Cre compared with C3H10T1/2 cells or C3H10T1/2 cells infected with Puro.let-7gsm.Cre. Either 2×103 or 104 cells were plated in 96-well plates for analysis. B) Cell proliferation related genes, cyclin D1, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and proliferation cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were decreased after let-7g over-expression. C) C3H10T1/2 cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre grew slower than C3H10T1/2 cells and C3H10T1/2 cells infected with Puro.let-7gsm.Cre. Either 104 or 3×104 cells were plated in 6-well plates for analysis. (*P < 0.05, §P < 0.10 when compared with let-7gsm; Mean ± SEM; n = 4 in each group).

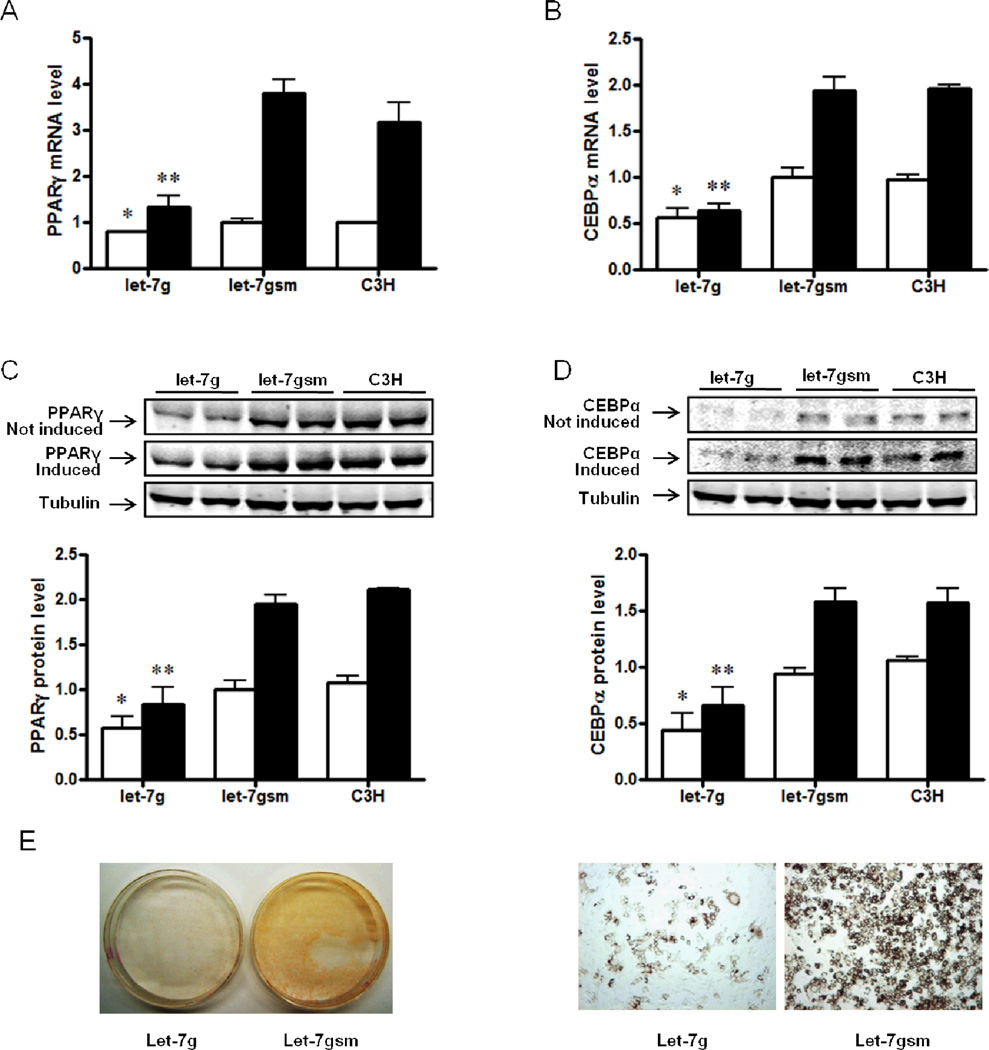

Let-7g and Adipogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

After 6 days of culture without adipogenic induction, Let-7g inhibited the mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) (20.6 ± 1.4% lower, P < 0.05, Figure 4A) and CCAAT-enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) (44.0 ± 9.9% lower, P < 0.05, Figure 4B), both of which are markers of adipogenesis, and also the protein content of PPARγ (42.9 ± 12.7% lower, P < 0.05, Figure 4C) and C/EBPα (56.1 ± 15.2% lower, P < 0.05, Figure 4D). After 6 days of adipogenic differentiation, the mRNA expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα was still much lower in cells over-expressing let-7g (65.0 ± 6.2% and 67.0 ± 3.7% lower respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 5A and 5B), and the protein content of PPARγ and C/EBPα was also less in let-7g over-expressed cells (56.9 ± 9.2% and 58.1 ± 10.3% lower respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 5C and 5D). After 10 days of adipogenic induction, less adipocytes were formed in cells infected with plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre, over-expressing let-7g (Figure 4E). These reductions in the expression of adipogenic markers and adipocyte formation likely were not due to the decrease in cell proliferation, because these data were normalized for the amount of RNA and proteins, or the total number of cells used for analyses.

Figure 4.

Let-7g inhibits expression of adipogenic differentiation markers and adipogenesis in C3H10T1/2 cells treated with 5′-azacytidine. A) mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) without or with adipogenic induction, which were both lower in cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre. B) mRNA expression of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα) without or with adipogenic induction, which were both lower in cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre. C) Protein content of PPARγ without or with adipogenic induction, which were both lower in cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre. D) Protein expression of C/EBPα without or with adipogenic induction, which were both lower in cells infected with Puro.let-7g.Cre. E) After cultured in adipogenic differentiation medium for 10 days, there were less adipocytes formed in C3H10T1/2 cells infected with lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre compared with cells infected with Puro.let-7gsm.Cre plasmid. (Left: 1 × magnification; Right: 100 × magnification). (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 when compared with let-7gsm; Mean ± SEM; n = 4; □, cells without adipogenic induction; ■, cells after adipogenic differentiation).

Figure 5.

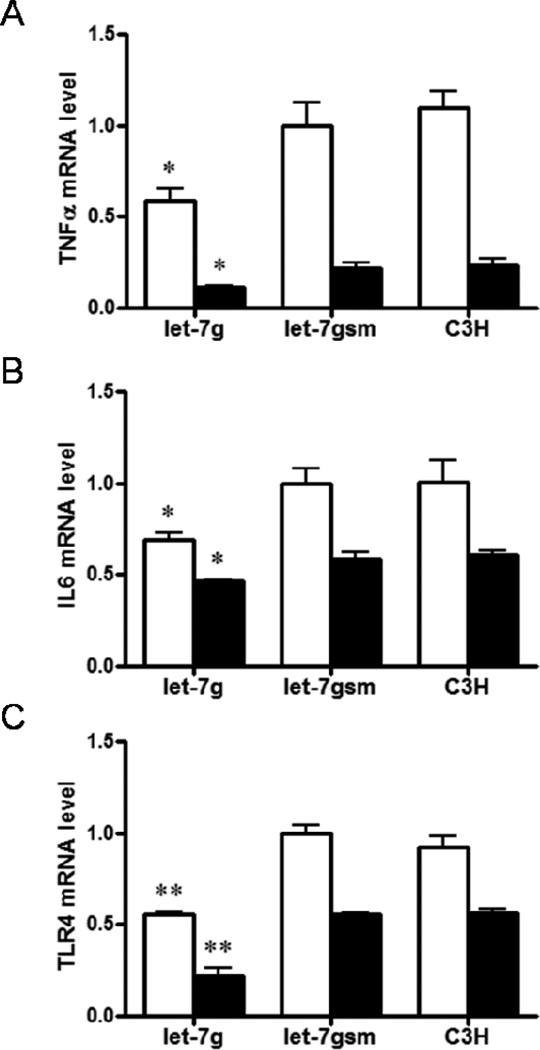

Let-7g inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines in C3H10T1/2 cells treated with 5′-azacytidine. A) Quantitative real time PCR showed a decreased expression of TNFα mRNA in C3H10T1/2 cells infected with lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre; after adipogenic differentiation, mRNA level of TNFα was reduced in all 3 types of cells, but there was difference between cells infected with lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre and C3H10T1/2 cells. B) mRNA expression of IL6 was lower in C3H10T1/2 cells infected with lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre than C3H10T1/2 cells before and after adipogenic differentiation. C) Lentiviral plasmid Puro.let-7g.Cre infection decreased the mRNA level of TLR4 in C3H10T1/2 cells both before and after adipogenic differentiation. (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 when compared with let-7gsm; Mean ± SEM; n = 4; □, cells without adipogenic induction; ■, cells after adipogenic differentiation).

To further analyze the role of Let-7g in adipogenesis, we measured the time course change of Let-7g expression during adipogenesis. The level of Let-7g did not change during the initial stage of adipogenesis, but slightly increased during the late stage of differentiation (Supplemental Figure 4). These data indicate that Let-7g expression is not closely correlated with adipogenic differentiation. The mechanisms regulating Let-7g expression need to be further explored.

Let-7g and the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines

Let-7g over-expression inhibited the expression of inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL6 and TLR4 (by 41.2 ± 6.3%, 30.5 ± 3.6% and 44.4 ± 1.6% respectively, P< 0.05, Figure 5A, B and C), demonstrating the anti-inflammatory effect of let-7g. Interestingly, the mRNA expression of those inflammatory cytokines was all decreased following adipogenic differentiation (49.2 ± 4.8%, 21.0 ± 1.5% and 60.8 ± 8.3% lower for let-7g, scrambled, and control cells respectively, P < 0.05, Figure 5A, B and C).

FST is as a Potential Target of Let-7g

We next investigated whether let-7g directly binds to the mRNA of its potential target gene FST. We cloned the 1086 bp 3’ UTR fragment of FST gene containing the predicted hsa-let-7g binding site and sub-cloned it into the 3’ UTR of luciferase gene. If the 3’ UTR fragment of FST gene is a target of let-7g, the stability of luciferase mRNA will be impaired and less luciferase will be translated. Using luciferase assay, we found that let-7g over-expression led to a modest decrease in luciferase activity (by 26.6 ± 5.7%, P < 0.10, Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that FST is a potential direct target of let-7g, which were consistent with the changes in FST expression in both fetal muscle in vivo and cultured cells in vitro.

Discussion

Obesity is an increasingly serious problem in the United States, as well as many countries around the world. Childhood obesity is also increasing. The high rate of maternal obesity predisposes offspring to obesity34, 35. Our previous studies have shown that myogenesis is impaired and adipogenesis increased in fetal muscle of obese sheep11, 12, 14, and we have demonstrated that chronic inflammation may play a role11, 14. However, the causative mechanisms remain poorly understood. In the current study, we analyzed miRNA expression of fetal sheep muscle at mid gestation. Our results showed that there are several miRNAs with differential expression in fetal muscle of control and obese mothers. Because of the high abundance of let-7g, we next analyzed expression of its potential target genes, including FST and TNFRSF4, which were both up-regulated. The association between let-7g and the expression of FST and TNFRSF4 was further tested in vitro. In C3H10T1/2 cells, with let-7g over-expression, both FST and TNFRSF4 were decreased, indicating that FST and TNFRSF4 are targets of let-7g.

We then tested the role of let-7g in cell proliferation. In let-7g over-expressed cells, we observed a lower proliferation rate, consistent with previous reports that let-7g suppresses growth of cancer cells and lung tumors16, 17. We also observed down-regulation of the cell proliferation markers cyclin D1, CDK4 and PCNA. Cyclin D1 has been used as a marker of cell proliferation and its lower expression represses cell proliferation31. Moreover, knocking down cyclin D1 suppresses cancer cell growth36. CDK4 forms a complex with cyclin D and plays an important role in cell cycle control37. PCNA is another marker of cell proliferation38. In combination, these data show that cell proliferation was decreased by let-7g over-expression.

The detailed mechanisms reducing cell proliferation remain to be investigated. A recent study using hepatocellular carcinoma cells showed that let-7g suppresses expression of c-Myc and increases expression of p16 (INK4A)39. Our data both in vivo and in vitro also showed that FST is one of the targets of let-7g. FST is a myostatin-binding protein which is known to inhibit the activity of myostatin, a negative regulator in cell proliferation40. In addition, FST induces satellite cell proliferation, which then leads to muscle hypertrophy41. Moreover, FST over-expression in human myoblasts promotes proliferation and differentiation, further supporting the role of FST in inducing cell proliferation42. We speculated that the inhibitory effect of let-7g on cell proliferation is partially mediated by targeting FST mRNA. Less let-7g expression in OB fetal muscle promoted FST expression, which enhances cell proliferation. Indeed, the muscle and weights were higher in fetuses of OB compared to those of control sheep12. We next investigated whether let-7g directly binds to the 3’ untranslated region of FST mRNA. We cloned the 1086 bp 3’ UTR fragment of FST and sub-cloned it into the 3’ UTR of luciferase gene. Using luciferase assay, we found that let-7g over-expression led to a modest decrease in luciferase activity. The relatively weak inhibitory effect on luciferase expression could be due to the fact that the cloned FST 3’ UTR might not include all let-7g targeted sequences, and another possibility is that FST is only an indirect target of let-7g, which requires further investigation.

Let-7g also affected adipogenesis. Expression of adipogenic markers was decreased in cells over-expressing let-7g. miRNAs have been reported to be involved in adipogenesis; for example, MiR-143 was reported to regulate adipocyte differentiation, but only in preadipocytes43. Let-7 family miRNAs, including let-7b and let-7c, have also been reported to regulate adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells, but again in preadipocytes44. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a potential role for let-7g in adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. However, there is a chance that the inhibitory role of let-7g on adipogenesis is derived from its ability to inhibit cell proliferation, which needs further studies to elucidate.

Our results further indicated that miRNA let-7g is involved in inflammation. We over-expressed let-7g in C3H10T1/2 cells, resulting in a decrease in the expression of inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL6 and TLR4. Thus, it is highly possible that miRNA let-7g plays a role in the development of chronic inflammation in fetal muscle of obese sheep. Indeed, we observed that the expression of both TNFα and IL6 mRNA was up-regulated in OB compared to Con fetal muscle, showing inflammatory response in OB fetal muscle.

We also analyzed the expression of let-7g during adipogenesis. Its expression is slightly increased during the late stage of adipogenesis, which indicates that adipogenic differentiation is not a major factor regulating let-7g expression. Up to now, there is no report describing factors governing let-7g expression, which warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that maternal obesity affects miRNA expression in fetal skeletal muscle, in which miRNA let-7g could play an important role because of its effects on the suppression of stem cell proliferation and adipogenic differentiation. Let-7g also inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, let-7g may be an important mediator linking obesity, inflammation and adipose tissue development. Such mechanism should be also applicable not only to intramuscular adipogenesis, but also in other adipose depots due to the uniformity in mechanisms regulating adipogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by NIH 1R01HD067449, 1R03HD057506, and USDA-NRI 2008-35206-18826.

Abbreviations

- C/EBP

CCAAT-enhancer binding protein

- Con

Control

- CDK4

Cyclin dependent kinase 4

- FST

follistatin

- IL

interleukin

- OB

Obesogenic

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PCNA

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- QRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFRSF4

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 4

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict to interest.

Supplementary information is available at IJO's website

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathanielsz PW. Animal models that elucidate basic principles of the developmental origins of adult diseases. Ilar J. 2006;47(1):73–82. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ. Fetal programming of coronary heart disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13(9):364–368. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00689-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooyackers OE, Nair KS. Hormonal regulation of human muscle protein metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17:457–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Effect of maternal nutrient restriction in sheep on the development of fetal skeletal muscle. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(6):1968–1973. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang YC, Zhang C, Wang SH, Xiong F, Zhao CP, Peng FN, et al. Activated beta-catenin induces myogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis in BM-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2007;9(7):667–681. doi: 10.1080/14653240701508437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artaza JN, Bhasin S, Magee TR, Reisz-Porszasz S, Shen R, Groome NP, et al. Myostatin inhibits myogenesis and promotes adipogenesis in C3H 10T(1/2) mesenchymal multipotent cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(8):3547–3557. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du M, Yin J, Zhu MJ. Cellular signaling pathways regulating the initial stage of adipogenesis and marbling of skeletal muscle. Meat Sci. 2010;86(1):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan X, Zhu MJ, Xu W, Tong JF, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, et al. Up-regulation of Toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappaB signaling is associated with enhanced adipogenesis and insulin resistance in fetal skeletal muscle of obese sheep at late gestation. Endocrinology. 2010;151(1):380–387. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu MJ, Han B, Tong J, Ma C, Kimzey JM, Underwood KR, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signalling pathways are down regulated and skeletal muscle development impaired in fetuses of obese, over-nourished sheep. The Journal of physiology. 2008;586(10):2651–2664. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong J, Zhu MJ, Underwood KR, Hess BW, Ford SP, Du M. AMP-activated protein kinase and adipogenesis in sheep fetal skeletal muscle and 3T3-L1 cells. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(6):1296–1305. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong JF, Yan X, Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Maternal obesity downregulates myogenesis and beta-catenin signaling in fetal skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(4):E917–E924. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90924.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan X, Huang Y, Zhao JX, Long NM, Uthlaut AB, Zhu MJ, et al. Maternal obesity-impaired insulin signaling in sheep and induced lipid accumulation and fibrosis in skeletal muscle of offspring. Biol Reprod. 2011;85(1):172–178. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, Sharp PA, et al. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403(6772):901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408(6808):86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyerinas B, Park SM, Hau A, Murmann AE, Peter ME. The role of let-7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(1):F19–F36. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima G, Hayashi K, Xi Y, Kudo K, Uchida K, Takasaki K, et al. Non-coding MicroRNAs hsa-let-7g and hsa-miR-181b are Associated with Chemoresponse to S-1 in Colon Cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2006;3(5):317–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanson DW, West TR, Tatman WR, Riley ML, Judkins MB, Moss GE. Relationship of body composition of mature ewes with condition score and body weight. J Anim Sci. 1993;71(5):1112–1116. doi: 10.2527/1993.7151112x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J, Yue W, Zhu MJ, Sreejayan N, Du M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) cross-talks with canonical Wnt signaling via phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser-552. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;395(1):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchildon F, St-Louis C, Akter R, Roodman V, Wiper-Bergeron NL. Transcription factor Smad3 is required for the inhibition of adipogenesis by retinoic acid. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(17):13274–13284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konieczny SF, Emerson CP., Jr 5-Azacytidine induction of stable mesodermal stem cell lineages from 10T1/2 cells: evidence for regulatory genes controlling determination. Cell. 1984;38(3):791–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor SM, Jones PA. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell. 1979;17(4):771–779. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamm JK, Park BH, Farmer SR. A role for C/EBPbeta in regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity during adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18464–18471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Feilotter HE, Pare GC, Zhang X, Pemberton JG, Garady C, et al. MicroRNA-193b represses cell proliferation and regulates cyclin D1 in melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(5):2520–2529. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao JX, Yue WF, Zhu MJ, Du M. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates beta-catenin transcription via histone deacetylase 5. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(18):16426–16434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Means WJ, Hess BW, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Maternal nutrient restriction affects properties of skeletal muscle in offspring. The Journal of physiology. 2006;575(Pt 1):241–250. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rooney KB, Ainge H, Thompson C, Ozanne SE. A systematic review on animal models of maternal high fat feeding and offspring glycaemic control. International Journal of Obesity. 2011;35(3):325–335. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor PD, Poston L. Developmental programming of obesity in mammals. Experimental Physiology. 2007;92(2):287–298. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei M, Zhu L, Li Y, Chen W, Han B, Wang Z, et al. Knocking down cyclin D1b inhibits breast cancer cell growth and suppresses tumor development in a breast cancer model. Cancer Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Iakova P, Wilde M, Welm A, Goode T, Roesler WJ, et al. C/EBPalpha arrests cell proliferation through direct inhibition of Cdk2 and Cdk4. Mol Cell. 2001;8(4):817–828. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubben FJ, Peeters-Haesevoets A, Engels LG, Baeten CG, Schutte B, Arends JW, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a new marker to study human colonic cell proliferation. Gut. 1994;35(4):530–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lan FF, Wang H, Chen YC, Chan CY, Ng SS, Li K, et al. Hsa-let-7g inhibits proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by downregulation of c-Myc and upregulation of p16(INK4A) Int J Cancer. 2011;128(2):319–331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SJ, Lee YS, Zimmers TA, Soleimani A, Matzuk MM, Tsuchida K, et al. Regulation of muscle mass by follistatin and activins. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):1998–2008. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilson H, Schakman O, Kalista S, Lause P, Tsuchida K, Thissen JP. Follistatin induces muscle hypertrophy through satellite cell proliferation and inhibition of both myostatin and activin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(1):E157–E164. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00193.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benabdallah BF, Bouchentouf M, Rousseau J, Tremblay JP. Overexpression of follistatin in human myoblasts increases their proliferation and differentiation, and improves the graft success in SCID mice. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(7):709–718. doi: 10.3727/096368909X470865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esau C, Kang X, Peralta E, Hanson E, Marcusson EG, Ravichandran LV, et al. MicroRNA-143 regulates adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52361–52365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun T, Fu M, Bookout AL, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. MicroRNA let-7 regulates 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(6):925–931. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.