Abstract

Objective

We used a consumer panel augmented with state-specific measures of tobacco control activities to examine main effects and interactions among consumer behaviors, particularly menthol cigarette smoking, and tobacco control environment on cessation over a six-year period.

Methods

We used the Nielson Homescan Panel, which tracks consumer purchasing behaviors, and tobacco control information matched to panelist zip code. We focused on 1,582 households purchasing ≥20 packs from 2004–2009. Our analysis included demographics; purchasing behavior including menthol versus nonmenthol use (≥80% of cigarettes purchased being menthol), quality preferences (average price/pack), purchase recency, and nicotine intake (nicotine levels of cigarettes purchased); and tobacco control metrics (taxation, anti-tobacco advertising, smoke-free policies).

Results

Menthol smoking (Hazards Ratio [HR]=0.79, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.64, 0.99), being African American (HR=0.67, CI 0.46, 0.98), being male (HR=0.46; CI 0.28, 0.74), higher quality premium preferences (HR=0.80, CI0.77, 0.91), lower recency (HR=1.04, CI 1.02, 1.05), and higher nicotine intake rates (HR=0.99, CI 0.99, 0.99) were related to continued smoking. No significant interactions were found.

Conclusion

While there were no interactions between menthol use and effects of tobacco control activities, we did find additional support for the decreased cessation rates among menthol cigarette smokers, particularly in the African American population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Menthol is a popular and controversial additive in cigarettes. A preliminary evaluation of the literature by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Center for Tobacco Products (Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, 2011) indicated that menthol’s cooling and anesthetic effects are related to reduced harshness of cigarette smoke, deeper inhalation, increased nicotine absorption (Ahijevych, 1999, Ahijevych and Parsley, 1999), increased addiction (Ahijevych, 1999, Ahijevych and Parsley, 1999), and greater difficulty quitting (Ahijevych and Garrett, 2004). Moreover, despite recent decreases in smoking prevalence, the proportion of menthol smokers has increased, particularly among youth and minority smokers, particularly African Americans (Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, 2011), contributing the smoking-related health disparities.

Contextual factors, particularly tobacco control activities, play a role in continued smoking versus cessation. Some of the most common and effective tobacco control practices include excise taxes on cigarettes, anti-smoking advertising, and smoke-free air policies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). It is plausible that these tobacco control activities and policies may influence some population subgroups differentially. However, no research has examined if these activities differentially affect menthol versus nonmenthol cigarette smokers.

Using the Socio Ecological Model (McLeroy et al., 1988, Stokols, 1996, Richards et al., 1996) as a framework, we examined individual consumer behaviors, particularly menthol cigarette smoking, and tobacco control environment in relation to cessation. Specifically, we used consumer panel data augmented with state-specific measures of tobacco control activities to examine the main effects and potential interactions among consumer behaviors and tobacco control environment on smoking cessation, as indicated by discontinued cigarette purchasing for at least a year among smokers in the panel. This information is particularly timely and relevant, given the recent FDA-issued Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to gather information and input from the public on menthol as a cigarette additive.

2. METHODS

The primary data for the current study is the Nielsen Homescan Panel, which provides a record of consumer packaged goods purchases for a large panel of nationally representative U.S. households. The panel is now a joint venture between IRi and Nielsen (http://www.ncppanel.com/content/ncp/ncphome.html). Each household in the panel is provided an optical scanner to scan barcodes of all consumer packaged goods they purchase, regardless of outlet (e.g., supermarkets, convenience stores, drug stores, gas stations). This broad coverage is important because, unlike many other product categories, smaller retail outlets account for a significant proportion of cigarette sales (American Heart Association and Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, 2012).

We used data collected among the 18,103 panelists observed continuously over the six-year period between January 2004 and December 2009, which included 5,575 cigarette purchasers (30.8%). We further restricted our sample to those who 1) made a cigarette purchase in 2004; 2) made ≥1 cigarette purchase in 2005 or later; 3) purchased ≥20 cigarette packs between 2004 and 2009; and 4) resided in one of the top 75 Designated Market Areas (DMAs) in order to track anti-smoking advertising. These criteria resulted in a final estimation sample of 1,582 panelists (households). In reference to criterion 3, we also examined alternative usage cut-points, specifically 50 and 100 packs of cigarettes. The main findings reported here were not significantly changed.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

We included age, gender, income level, and race/ethnicity in our analyses. If the household included only a single individual, then we used the individual’s age. If the household included two adults, we used the average of the two adult member’s ages. While this approach has limitations, the correlation of male and female adult household member ages was .874. We also included a variable indicating female single member households and male single member households, with the constant being mixed gender adult member households. In addition, exploratory analyses indicated that African American quit rates were significantly different from other races/ethnicities; thus, we chose to categorize race/ethnicity as African American versus other.

Purchasing characteristics

We used the consumer purchase panel to create transaction histories that include a record of the brands, flavors, prices, and machine-tested nicotine content of cigarettes purchased by households for the six-year period from 2004 to 2009. We used each panelist’s first twelve months of activity to initialize the transaction history variables and quality preferences. We defined a menthol smoker to be a smoker that devoted ≥80% of units purchased to menthol cigarettes. We also tested alternative definitions of being a menthol smoker in our statistical models (i.e., ≥20%,≥50%); however, findings did not change significantly. “Quality preference” was operationalized as the average price per pack in each month of a household’s most often purchased brand (Aaker, 1996, Ailawadi et al., 2003). This definition is rooted in academic marketing research related to the concept of brand equity. Specifically, price premiums reflect consumer’s perceptions of brand quality. Thus, our quality preference measure is simply the average price paid during the first year of the data (2004). The highest quartile paid at least $2.55 per pack (exclusive of taxes), the average price was $1.79 and the lower quartile paid less than $1.30. We also included “Recency”, operationalized as the time in months since a cigarette purchase. Recency has been found to be highly predictive of future customer purchasing in a wide range of marketing contexts (Lewis, 2004). We also included the consumer’s previous level of nicotine intake as measured by the machine-tested nicotine levels of the cigarettes purchased in the previous month multiplied by cigarette consumption. For example, for April 2008, nicotine intake would be the machine-tested nicotine levels of the cigarettes purchased in March 2008 multiplied by cigarette consumption. If no cigarettes were purchased in the previous month, then “nicotine intake” used to model behavior in the next month would be zero.

Tobacco control environments

We supplemented the individual consumer information with data on three major tobacco control practices. This information is collected from multiple sources and includes cigarette excise taxes, anti-smoking advertising rating points, and smoke-free restrictions as indicated by the zip codes of each panelist. Cigarette excise taxes were obtained from the Tax Burden on Tobacco report (2011), which provides detailed information on federal, state, and local tax rates and effective dates. For simplicity, we assumed that a smoker purchased only from stores located in the same state that he or she lives and matched the federal, state, and local cigarette excise taxes, respectively. We created a variable that captured the average tax inclusive prices faced by the consumer each month. For anti-smoking advertising, we matched each smoker to a specific Designated Market Area (DMA) based on his or her zip code according to Nielson’s DMA map. We obtained data on adult-targeted anti-smoking advertising gross rating points from A.C. Nielson, for all cable and network television in each DMA. Rather than directly include anti-smoking advertising, we created a variable that defines the stock of health advertising, which is a common approach in the economics and marketing literatures (Little, 1979). The basic procedure is that each month the current stock of anti-smoking advertising is calculated as the sum of the current gross ratings points in the customers (DMA) and the previous stock multiplied by a decay factor of .95. The advertising stock variables are initialized using DMA level gross ratings points for the period from 2000 to 2004. To assess smoke-free restrictions, each smoker was matched to their respective state’s level of smoke-free policies in four common venues - restaurants, bars, private workplaces, and government workplaces - from the CDC’s STATE tracking studies. In each venue, smoke-free restrictions were assigned one of three values: 0 for no restriction, .5 for partial restriction, and 1 for a complete restriction. We took the average of the smoke-free restrictions in the four venues to describe a state’s smoke-free policy level.

Cessation

The outcome in this study was smoking cessation. Specifically, we defined a smoker to have “quit” if he or she did not purchase a pack of cigarettes for at least one year. A recent meta-analyses indicated that 10% of smokers relapse after one year of abstinence (Hughes et al., 2008). Thus, this outcome was defined in order to capture smokers who have quit with low risk of relapse. We also tested alternative definitions of quitting such as no purchases over a 6 month period in our statistical analyses; however, findings were not significantly altered.

Data Analysis

First, we examined the distribution of packs purchased per year. We also examined the extent to which individuals were consistent in purchasing menthol cigarettes per “share of category”. Share of category is a common marketing metric reflecting the proportion of units of a specific type or brand of product in a product category. For example, if a household purchased five packs of menthol cigarettes and 10 packs of other cigarettes the menthol share of customer would be 5/15 = 33.3%.

Then, we conducted descriptive statistics and survival or hazard models examining cessation. Survival models have been used in other marketing research (Lewis, 2006) to study consumer attrition. In our analyses, duration was the time until quitting, and censoring occurred if an individual had not quit prior to the end of the observation period. We examined the main effects of participant demographics, purchasing behaviors, and tobacco control environment on cessation. Then, we tested for interactions between being a menthol cigarette smoker and tobacco control measures including excise tax levels, anti-smoking advertising, and smoke-free air policies. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.

3. RESULTS

Brand/Menthol Loyalty

Table 1 shows the share of category devoted to menthol cigarette expenditures (percentage of menthol packs divided by total packs). In the six-year panel, 52% of smokers purchased only a single brand, and 33% purchased only two brands. Menthol cigarettes accounted for 30.6% of cigarette spending. Roughly 60% of smokers devoted < 10% of expenditures on menthol cigarettes, and >25% allocated >80% of expenditures on menthol cigarettes. Figure 1 shows the distribution of packs purchased per year, indicating that the proportion of nonpurchasers of cigarettes increased from 2004 to 2009. In 2005, 2.09% of the panel purchased zero cigarettes. This “quit” percentage increased to 5.8% in 2006, 10.7% in 2007, 17.6% in 2008, and 23.8% in 2009.

Table 1.

Distribution of share of category devoted to menthol cigarettes versus all cigarettes

| Nicotine Share of Category | Frequency | Percent % | Cumulative Percent % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 657 | 41.5 | 41.5 |

| [0, 10%] | 285 | 17.9 | 59.5 |

| [10, 20%] | 44 | 2.8 | 62.3 |

| [20, 30%] | 26 | 1.6 | 63.9 |

| [30, 40%] | 17 | 1.1 | 64.9 |

| [40, 50%] | 33 | 2.1 | 67.1 |

| [50, 60%] | 21 | 1.3 | 68.4 |

| [60, 70%] | 20 | 1.3 | 69.6 |

| [70, 80%] | 27 | 1.7 | 71.3 |

| [80, 90%] | 29 | 1.8 | 73.2 |

| [90, 100%] | 235 | 14.8 | 88.0 |

| 100% | 190 | 12.0 | 100.0 |

Figure 1.

Distributions of purchased cigarette packs annually

Descriptive Statistics and Hazard Model Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and estimation results from a Cox proportional-hazards model. Menthol smoking (Hazards Ratio [HR]=0.79, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.64, 0.99) and being African American (HR=0.67, CI 0.46, 0.98) were positively related to continued smoking at the end of 2009. Table 3 indicates that African American consumers were more likely than non-African American consumers to purchase menthol cigarettes (54.5% vs. 25.2%, respectively). Quit rates for menthol cigarette smokers were lower compared to nonmenthol smokers (19.8% vs. 27.4%, respectively). For African Americans, the quit rate for nonmenthol smokers was 18.5% versus 17.0% for menthol smokers. In comparison, the corresponding quit rates for non-African American households were 26.8% among nonmenthol smokers and 21.3% among menthol smokers.

Table 2.

Descriptive summary of consumer characteristics and tobacco control environment and the proportional hazard function estimation predicting cessation (Cox Model)

| Variables | Mean (or N) | S.D. (or %) | Hazard ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.01 | 10.43 | 1.01 | [0.99, 1.02] |

| Single Female, N(%) | 415 | 26.2% | 0.87 | [0.64, 1.16] |

| Single Male, N(%) | 151 | 9.5% | 0.46 | [0.28, 0.74] |

| Income* | 59,592 | 37,450 | 1.08 | [0.92, 1.28] |

| African American, N(%) | 189 | 11.9% | 0.67 | [0.46, 0.98] |

| Menthol smoker, N(%) | 454 | 48.6% | 0.79 | [0.64, 0.99] |

| Quality preference | $1.79 | 0.90 | 0.80 | [0.77, 0.91] |

| Recency (months) | 2.49 | 4.13 | 1.04 | [1.02, 1.05] |

| Nicotine intake (mg) | 374 | 548 | 0.99 | [0.99, 0.99] |

| Price + Tax | $3.27 | 1.07 | 1.07 | [1.01, 1.14] |

| Monthly anti-ad GRPs* | 249 | 435 | 1.03 | [0.95, 1.13] |

| Smoke-free policies | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.83 | [0.49, 1.39] |

Cessation rate: 23.7% (n=375/1,582)

Log pseudo-likelihood: −2,63; Observations: 69,711

Note: 1) the analysis has controlled for the panel structure; 2) state dummies are included.

Log used in model.

Table 3.

Menthol cigarette smoking and quit rates among African American versus non-African American panelists

| African American | Non-African American | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmenthol cigarette smokers | Use

|

n=86 | n=1042 | N=1128 |

| Quit | 18.5% | 26.8% | 26.2% | |

|

|

||||

| Menthol cigarette smokers | Use

|

n=103 | n=351 | N=454 |

| Quit | 17.0% | 21.3% | 20.3% | |

|

| ||||

| Total | N=189 | N=1,393 | N=1,582 | |

Note: a. The Chi-square for menthol cigarette smoking by African American is 65.89(1) with a p-value<.01; b. The Chi-square for quit rate by African American is 4.63(1) with a p-value<.05; c. The Chi-square for quit rate by menthol cigarette smoking is 7.34(1) with a p-value<.01.

In terms of other consumer characteristics, males were less likely to quit smoking (HR=0.46; CI 0.28, 0.74). In addition, having higher quality premium preferences (HR=0.80, CI0.77, 0.91), lower recency (HR=1.04, CI 1.02, 1.05), and having higher nicotine intake rates (HR=0.99, CI 0.99, 0.99) were related to lower likelihood of quitting smoking. These terms are both related to the addictive nature of cigarette consumption. Since the recency term increased as time since cigarette purchase, the recency coefficient suggests that quitting was less likely when the consumer had purchased more recently. Therefore, the recency variable is a control term that captures habitual purchasing tendencies. In terms of the tobacco control environment, higher overall cost of cigarettes was positively associated with quitting (HR=1.07, CI 1.01, 1.14). We also examined the interactions among the consumer behavior variables, particularly menthol smoking, and the tobacco control environment variables to assess whether menthol consumption made smokers more or less responsive to tobacco control activity. This model did not yield any significant interactions.

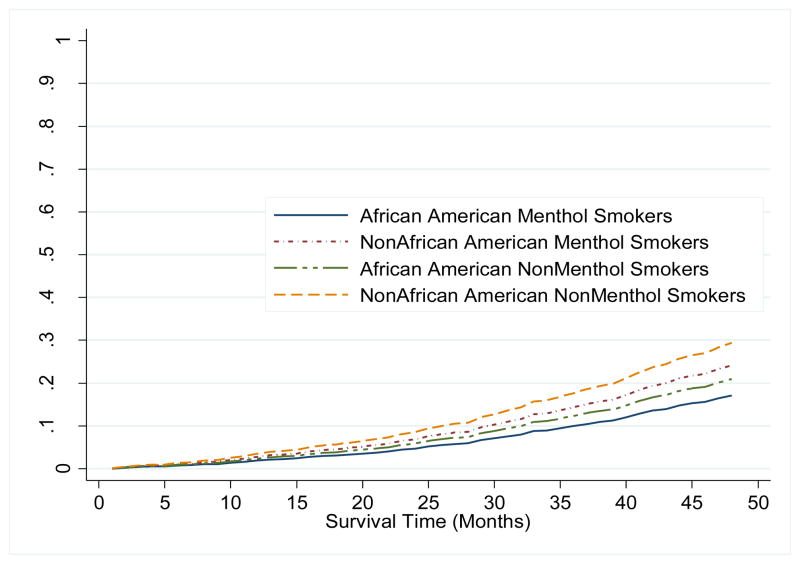

Figure 2 shows the survival plots for menthol and non-menthol smokers of different races. The survival rates are derived from the hazard model after controlling for individual differences and differences in exposure to tobacco control policies. In this context, “survival” corresponded to a consumer continuing to smoke and the quit rate is one minus the survival rate. The figure shows that African American menthol smokers were the most likely to continue smoking while non-African American nonmenthol smokers were the most likely to quit smoking. By the end of 2009, menthol smokers were less likely to quit (17.1% in African Americans, 24.2% in non-African Americans) compared to nonmenthol smokers (21.9% in African Americans, 29.4% in non-African Americans). Moreover, African American menthol and nonmenthol smokers were less likely to quit than non-African American menthol and nonmenthol smokers, respectively.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of quitters over time

Note: the adjusted cumulative quit rate among African American menthol users is 17.1% at the end of 2009; the adjusted cumulative quit rate among African American nonmenthol users is 20.9% at the end of 2009; the adjusted cumulative quit rate among Non-African American menthol users is 24.2% at the end of 2009; the adjusted cumulative quit rate among Non-African American nonmenthol users is 29.4% at the end of 2009.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study provides novel and important data regarding cigarette purchasing behaviors through the use of a rich national multifaceted dataset that monitored the characteristics of cigarette purchases in the actual mark environment for a period of six years and accounted for time and geographical variation in tobacco control activity. In the context of the Socio Ecological Model, while individual level consumer behaviors were significantly associated with cessation, taxation level was the only environmental level factor that was significantly related to cessation. Moreover, interactions across the variables that we assessed on these two broad levels were not found in relation to cessation.

One major finding was that menthol versus nonmenthol smokers were significantly less likely to quit smoking (18% versus 25%), controlling for other individual consumer behaviors and tobacco control environment factors. This is consistent with previous research indicating lower cessation rates of menthol smokers (Ahijevych and Garrett, 2004, Harris et al., 2004, Okuyemi et al., 2004a, Pletcher et al., 2006). Additionally, we documented the strong “flavor” loyalty among menthol smokers, per the distribution of share of category allocated to menthol products.

Another major finding of the current analyses was the lower quit rates among African American households, which adds to the compiling literature suggesting lower quit rates among African American smokers (Choi et al., 2004) and the compounding risk of continued smoking related to menthol cigarette smoking among African Americans (Okuyemi et al., 2004b, Gandhi et al., 2009, Okuyemi et al., 2007). The novel methodology used in this study provides a rich behavioral model of tobacco use among a large representative sample of consumers. Interestingly, income was not associated with cessation in this study. Prior research has indicated that lower likelihood of cessation is associated with lower socioeconomic status as indicated by income (Siahpush, 2009) and education level (CDC, 2011). Numerous studies have documented that raising the price of cigarettes directly reduces both adult and youth smoking, particularly among low-income smokers (CDC, 1998). However, price and overall cost (including excise tax) were major predictors of cessation. There is strong evidence in support of taxation in tobacco control efforts (CDC, 2012), so this finding is not surprising.

In terms of consumer characteristics, households with single men were less likely to quit than mixed gender households, whereas households with single women were not significantly different. In addition, those with lower nicotine intake and those with lower quality premium preferences were more likely to quit smoking. If lower nicotine intake can be assumed to be a proxy for lower consumption and potentially lower addiction (Hyland et al., 2006, Baker et al., 2007), this finding is not surprising, as other research has indicated that lower baseline smoking predicts cessation (Hyland et al., 2006). In terms of quality preference, those who spent less on their cigarettes were more likely to quit smoking. This result is consistent with the marketing literature that has consistently found that lower quality brands tend to be more price elastic (Hoeffler and Keller, 2003) and have less loyal consumers.

Finally, we also documented that tobacco counter-marketing and levels of smoke-free air policies were unrelated to cessation. In addition, we did not find any significant interactions between taxation, anti-tobacco promotions, smoke-free policies, and menthol user quit rates. However, it is possible that the variability of these factors was not large enough to have differential impact on individual-level consumer behavior.

Limitations

Limitations include the reliance on panelists to fully report all cigarette purchases and the assumption that purchasing is equivalent to consumption. An additional issue is that the consumer panel operates at the household level. Furthermore, our definitions of smoker, menthol smoker, and cessation are somewhat arbitrary. We estimated models using other criteria for these definitions and found our results to be robust to different definitions of “smokers” and “menthol users” Finally, we did not include all tobacco control policies in our models, as there was relatively little variability compared to the policies included in the current study.

5. CONCLUSIONS

These findings add to the accumulating literature suggesting lower cessation rates among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers. The novel approach and multi-level data included here provide additional perspective regarding consumer behavior and the impact of policy, community, and individual characteristics in relation to long-term cessation outcomes over a six-year period. While we found no differential influence of tobacco control activities on smoking outcomes among menthol and nonmenthol smokers, these findings provide support for increased regulation of menthol in a similar manner to other cigarette flavorings.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Menthol cigarette smokers are less likely to quit compared to non-menthol cigarette smokers.

African Americans are more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes and less likely to quit smoking.

Menthol and non-menthol smokers are not differentially affected by tobacco control policies.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Dr. Berg’s effort was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1K07CA139114-01A1; PI: Berg). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaker DA. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review. 1996;38:102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ahijevych K. Nicotine metabolism variability and nicotine addiction. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:S69–70. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahijevych K, Garrett BE. Menthol pharmacology and its potential impact on cigarette smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:S17–28. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahijevych K, Parsley LA. Smoke constituent exposure and stage of change in black and white women cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 1999;24:115–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadi KL, Lehmann DR, Neslin SL. Revenue Premium as an Outcome Measure of Brand Equity. J Marketing Res. 2003;67:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association and Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Deadly Alliance: How Big Tobacco and Convenience Stores Partner to Market Tobacco Products and Fight Life-Saving Policies 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, Colby S, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:S555–70. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Response to Increases in Cigarette Prices by Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Age Groups -- United States, 1976–1993. MMWR. 1998;47:605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. 2012 http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html [Online]

- Choi WS, Okuyemi KS, Kaur H, Ahluwalia JS. Comparison of smoking relapse curves among African-American smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1679–83. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, Williams JM. Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:360–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KJ, Okuyemi KS, Catley D, Mayo M, Ge B, Ahluwalia JS. Predictors of smoking cessation among African-Americans enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of bupropion. Prev Med. 2004;38:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffler S, Keller KN. The marketing advantages of strong brands. J Brand Management. 2003;10:421–445. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Peters EN, Naud S. Relapse to smoking after 1 year of abstinence: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1516–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong HH, McNeill A, Fong GT, O’Connor RJ, Cumming KM. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15:iii83–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. The influence of loyalty programs and short-term promotions on customer retention. J Marketing Res. 2004;41:281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Customer acquisition promotions and customer asset value. J Marketing Res. 2006;43:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Little JD. Aggregate advertising models: The state of the art. Operations Res. 1979;27:629–667. [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS, Banks R, Harris KJ, Mosier MC, Nazir N, Powell J. Differences in smoking and quitting experiences by levels of smoking among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2004a;14:127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS. African-American menthol and nonmenthol smokers: differences in smoking and cessation experiences. J National Med Assoc. 2004b;96:1208–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:1979–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Hulley BJ, Houston T, Kiefe CI, Benowitz N, Sidney S. Menthol cigarettes, smoking cessation, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary function: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:1915–22. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L, Potniv L, Kishchuk N, Prlic H, Green L. Assessment of the Integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Promotion. 1996;10:318–327. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promotion. 1996;10:282–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]