Abstract

Objective

Existing research suggests that walkable environments are protective against weight gain, while sprawling neighborhoods may pose health risks. Using prospective data on displaced Hurricane Katrina survivors, we provide the first natural experimental data on sprawl and body mass index (BMI).

Methods

The analysis uses prospectively collected pre- (2003–2005) and post-hurricane (2006–2007) data from the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) project on 280 displaced Hurricane Katrina survivors who had little control over their neighborhood placement immediately after the disaster. The county sprawl index, a standardized measure of built environment, was used to predict BMI at follow-up, adjusted for baseline BMI and sprawl; Hurricane-related trauma; and demographic and economic characteristics.

Results

Respondents from 8 New Orleans-area counties were dispersed to 76 counties post-Katrina. Sprawl increased by an average of 1.5 standard deviations (30 points) on the county sprawl index. Each one point increase in sprawl was associated with approximately .05 kg/m2 higher BMI in unadjusted models (95%CI: .01–.08), and the relationship was not attenuated after covariate adjustment.

Conclusions

We find a robust association between residence in a sprawling county and higher BMI unlikely to be caused by self-selection into neighborhoods, suggesting that the built environment may foster changes in weight.

Keywords: Body mass index, Residence Characteristics, Multilevel Analysis, United States, Disasters

Introduction

Existing research suggests that the built environment matters for weight gain and its antecedents. With few exceptions (Durand et al., 2011), current studies show that residential density and street connectivity are associated with transit use, active transport, and less driving (de Nazelle et al., 2011; Sallis et al., 2012) and with lower odds of overweight and obesity (Ewing et al., 2006; Ewing et al., 2003; James et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Mujahid et al., 2008; Plantinga and Bernell, 2007; Sallis et al., 2009). However, most studies examining the effects of the neighborhood built environment are cross-sectional, and virtually all are observational (O. Ferdinand et al., 2012). As a result, existing studies have been unable to reject endogeneity as an explanation for observed associations, with the possibility of leaner subjects electing to live in more walkable communities, or pressuring their current communities to become more walkable. The threats of confounding by residential self-selection and reverse causation underscore the need for quasi-experimental data to rigorously explore built environment effects on body mass index (BMI) (Handy et al., 2006) (Eid et al., 2007; Frank et al., 2007). In fact, despite the publication of nearly 50 studies on the built environment and BMI or obesity (O. Ferdinand et al., 2012), researchers are still unable to draw conclusions about whether observed relationships are causal (Casazza et al., 2013).

Notwithstanding the Moving to Opportunity experiment (Katz et al., 2001; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2003; Leventhal and Dupere, 2011), random or nearly random assignment to neighborhoods is uncommon. To date, there have been no experimental or quasi-experimental studies published on the effect of sprawl on weight gain. This analysis uses multilevel statistical analysis to explore county-level sprawl as a predictor of BMI in a longitudinal study of low-income, displaced Hurricane Katrina survivors who had little to no control over their neighborhood placement immediately after the disaster, providing the first natural experimental data on urban sprawl and BMI.

Methods

Data Source

The Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) project is a longitudinal study of Hurricane Katrina survivors that offers prospectively collected pre- and post-hurricane data on 1,019 young, poor, predominantly African American parents from New Orleans. Pre-Katrina data were collected as part of MDRC’s Opening Doors Evaluation, a randomized-design program aimed to increase academic persistence in community colleges that included a National Institutes of Health-funded health module. Participants were sought from three community colleges in New Orleans in 2003–2005. Eligible respondents had to be 18–34 years old; the parent of at least one dependent child under 19; have a household income under 200 percent of the federal poverty level; and have a high school diploma or equivalent. Data collection for the 12-month follow-up survey was interrupted when Hurricane Katrina struck on August 29, 2005, and the Opening Doors study was redesigned to become the RISK Project, which followed subjects to their new neighborhoods after the disaster. A qualitative data collection component, consisting of in-depth interviews with a sample of subjects, was also added to help elucidate experiences of trauma, displacement, and related processes. The study was approved by the Harvard and Princeton Institutional Review Boards.

At baseline (November 2003 – February 2005), all 1,019 subjects lived in New Orleans or a surrounding metropolitan area parish. We were able to locate and survey 711 of the original respondents 7 to 19 months after Katrina struck (March 2006 – March 2007), 693 of whom provided information about where they were living (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study participant paths from pre-Katrina (2003–2005) New Orleans-area neighborhoods to post-Katrina (2006–2007) neighborhoods

Roughly 47% were living in the New Orleans metropolitan region, while 53% of subjects (n=369) were displaced from the area at follow-up. To isolate the causal effects of neighborhood sprawl on BMI, we excluded those who remained in the New Orleans area, as this residential location had been self-selected prior to the hurricane. The analysis focused exclusively on subjects who were living outside the New Orleans region at follow-up. The factors that led displaced participants to their post-Katrina neighborhoods have been discussed extensively elsewhere (Fussell, 2012), with illustrative examples gleaned from qualitative in-depth interviews including: seeking out nearby relatives, evacuating to Georgia because east-bound evacuation traffic seemed lightest, and a Dallas-bound bus being turned away in Dallas, Houston, and Mesquite due to full shelters before finally stopping in Wylie, TX. Though our qualitative data suggest that displaced subjects did not select into neighborhoods systematically with regard to sprawl, we test for this possibility empirically.

Of the 369 displaced subjects, 280 had complete baseline and follow-up information on BMI and county of residence, and serve as our study population. At follow-up, the 280 participants (Figure 2) were dispersed across 76 counties in 24 states, including within Louisiana.

Figure 2.

Sample selection flowchart of Hurricane Katrina survivors displaced from New Orleans between baseline (2003–2005) and post-Katrina follow-up (2006–2007)

Outcome

Our outcome of interest was BMI, calculated from self-reported height and weight at each wave. While self-reported BMI is known to be downwardly biased, we have no reason to expect the extent of this bias to vary according to displacement experiences. Previous research has demonstrated that self-reported BMI is valid when compared to clinical measurement, including a study by Willet et al. (Willett et al., 1983) showing that self-reported weights were highly correlated with measured weights (r=0.96).

Exposure

To characterize the built environment, we used a standardized measure of urban sprawl called the county sprawl index, which has been previously associated with physical activity and BMI (Ewing et al., 2006; Ewing et al., 2003; James et al., 2013). The county sprawl index was developed by Smart Growth America (Smart Growth America, 2002) and calculated for all 448 metropolitan counties or statistically equivalent entities in the US. More than 183 million Americans, nearly two thirds of the United States population, lived in these 448 counties in 2000. Six county-level US Census 2000 variables were used to describe two characteristics of sprawl: 1) low residential density, which was a function of gross population; percentage of county population living at low suburban densities; percentage of county population living at moderate-to-high urban densities; and net density in urban areas, and 2) poor street accessibility, captured by average block size, and the percentage of blocks smaller than .01 square miles in area (the typical urban block is bounded by sides roughly .09 miles long).

Sprawling areas are generally less walkable or bikable than compact places. Through principal components analysis, the six census variables were combined to form one factor that explained 63.4% of the total variance among the input variables. This factor was then transformed to a county sprawl index variable with a mean of 100. Higher county sprawl index values indicate a more compact (i.e., less sprawling) county.

Covariates

We adjusted for two types of potential confounders. First, despite the apparent low levels of control that survivors had over neighborhood choice, we sought to account for the possibility that individual characteristics influenced the level of sprawl survivors experienced in their post-Katrina counties. Although our sample was highly homogenous by design, we accounted for social and demographic factors that could affect both selection into neighborhoods and change in BMI, including age, race, sex, number of children, and baseline socioeconomic status, as measured by whether subjects reported receiving welfare or cash assistance. Because social support has been linked to better health and might have provided subjects with more choice over where to live, we also include a validated four point scale of social support at baseline (Cutrona and Russell, 1987).

Similarly, we adjusted for stressful hurricane-related experiences (Brodie et al., 2006). Survey instruments prompted survivors to indicate if they had experienced eight specific Hurricane Katrina-related traumas, including not having enough food, water, or necessary medication/medical attention for themselves or family members; feeling their lives or a family member’s life was in danger; and not knowing whether their children were safe. We used the count of affirmative responses to quantify hurricane-related traumas. We also included a dichotomous variable for whether a subject reported that a close friend or family member was killed in Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Rita. If trauma influenced post-Katrina neighborhood preferences and also spurred changes in weight, hurricane-related stress could confound our associations of interest.

The second type of potential confounders account for the fact that sprawl might serve as a marker for economic opportunity, with cities offering higher wages and more job options, for example. We adjusted for post-Katrina employment status and total household income to test the possibility that observed neighborhood effects were driven by socioeconomic exposures rather than the built environment.

Statistical Analysis

To look for evidence of neighborhood selection by baseline characteristics or hurricane trauma, we performed a series of hierarchical bivariate linear regressions. These models regressed county sprawl at follow up on the following predictors: baseline age, race, gender, social support, whether a subject received welfare at baseline, number of hurricane-related traumas, and the death of family member or friend. We clustered participants in baseline counties with the understanding that neighbors might have been more likely to board the same bus out of New Orleans, and therefore resettle in the same area, and to share similar sociodemographic and traumatic experience profiles.

Our interest in the effect of an area-level exposure on an individual-level outcome created a classic multilevel data structure (Arcaya and Subramanian, 2014; Diez-Roux, 1998), with individuals (level-1) nested within follow-up counties (level-2). We fit a series of multivariable hierarchical linear regression models to test whether county sprawl at follow up predicted BMI at follow up, controlling for baseline sprawl and BMI, and for potential confounders in fully adjusted models. Our estimation of hierarchical, or multilevel, models accounted for the fact that multiple respondents were displaced to the same counties and allowed us to obtain valid standard errors and confidence intervals around parameter estimates despite any statistical dependence among observations within counties. As a sensitivity analysis, we stratified main models according to whether subjects had lost a friend or family member. We also tested whether main model results were sensitive to adjustment for distance between participants’ pre-Katrina and post-Katrina addresses to help us explore whether unmeasured area-level characteristics that were correlated with distance from New Orleans might produce spurious associations between BMI and sprawl. For example, if farther distance moves resulted in relocation to colder climates that were less attractive for physical activity, as well as to more sprawling areas, distance could be an important confounder.

All analyses we conducted in Stata/SE 12.1.

Results

The study population was young, with a mean age of roughly 25, and had an average of 1.9 children at baseline. Nearly 90% of the sample identified as non-Hispanic Black and 94% as female. Although all were under 200% of the poverty line, just 13% received welfare or other cash assistance at baseline. Over 30% of the sample reported that a close friend or relative had died as a result of Hurricanes Katrina or Rita, or their aftermath. Mean baseline BMI was 28.8 kg/m2, and subjects reported enjoying high levels of social support on average (Table 1). Because the original Opening Doors experiment recruited students enrolled in New Orleans-area community colleges, all subjects lived in one of eight relatively dense, walkable counties at baseline (Jefferson, Lafourche, Orleans, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, St. Tammany, or Terrenonne Parish). On average, subjects lived in baseline communities that were roughly 2.2 standard deviations more compact than the national average (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline (2003–2005), and Severity of Hurricane-related Trauma (2005)

| Number reporting | Mean (SD) or Percent |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | ||

| Age at baseline | 280 | 25.1 (4.4) |

| Number of children | 278 | 1.9 (1.2) |

| Social Support (1 = low, 4 = high) | 270 | 3.2 (0.5) |

| Proportion non-Hispanic white | 271 | 6.6 |

| Proportion non-Hispanic black | 271 | 89.3 |

| Proportion Hispanic | 271 | 2.2 |

| Proportion other | 271 | 1.9 |

| Proportion female | 280 | 93.6 |

| Proportion receiving welfare or cash assistance | 275 | 13.1 |

| Hurricane Exposure | ||

| Number of hurricane-related traumas (0 – 8) | 151 | 3.3 (2.8) |

| Had a relative or close friend die in Hurricane Katrina or Rita | 273 | 31.5 |

Table 2.

Sprawl and Body Mass Index for 280 Hurricane Katrina Survivors with Pre-(2003–2005) and Post-Katrina (2006–2007) observations

| Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Katrina 2003–2005 |

Post-Katrina 2006–2007 |

|

| Body Mass Index | 28.8 (7.5) | 29.0 (7.5) |

| Sprawl index of participant counties | 138.6 (16.7) | 108.6 (11.4) |

| National sprawl index (time invariant) | 94.2 (19.7) | |

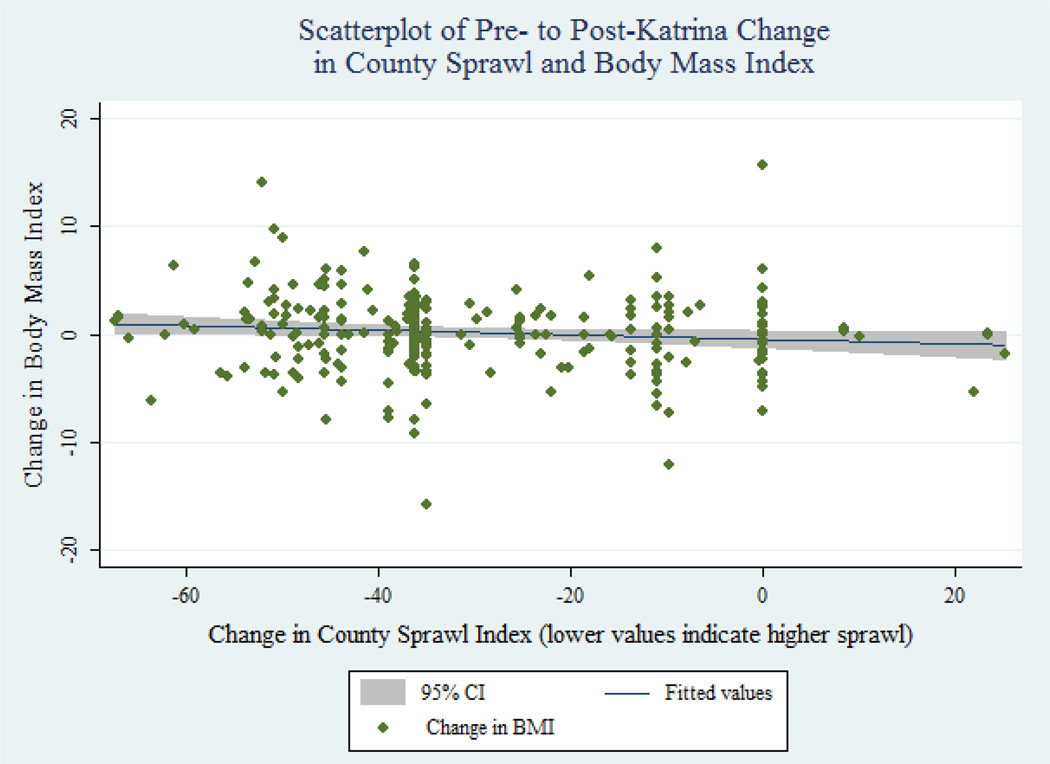

After displacement from New Orleans, subjects were dispersed across 76 counties and the mean county sprawl index dropped by roughly 30 points, or 1.5 standard deviations, indicating that post-Katrina counties were less compact (i.e., more sprawling) than were baseline counties (Table 2, Figure 3). We found no associations between baseline BMI, sociodemographic characteristics, or number of hurricane-related traumas reported and subsequent sprawl, which suggests that observed associations were unlikely to be confounded by self-selection into neighborhoods. Having a close friend or relative die as a result of Hurricane Katrina or Rita was associated with living in a more sprawling county at follow-up (p=.02), but was not associated with weight gain in bivariate analyses.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of Pre- (2003–2005) to Post-Katrina (2006–2007) Change in County Sprawl and Body Mass Index

Main models showed an association between county sprawl at follow-up and BMI, adjusting for sprawl and BMI at baseline (Table 3). Keeping in mind that less compact counties are scored lower on the county sprawl index, each one unit decrease in county sprawl index was associated with approximately .05 higher BMI. A 30 point lower sprawl index, which is roughly equivalent to the difference between the mean pre- and post-Katrina neighborhoods, corresponds to a 1.49 unit increase in BMI, or an approximately 4.3 kg weight gain for a 1.7 meter tall individual.

Table 3.

Associations between Post-Katrina Sprawl and BMI (2006–2007), null and adjusted models

| Model 1 β (se) |

Model 2 β (se) |

Model 3 β (se) |

Model 4 β (se) |

Model 5 β (se) |

Model 6 β (se) |

Model 7 β (se) |

Model 8 β (se) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Katrina County Sprawl Index | −0.047* (0.02) | −0.050* (0.02) | −0.051** (0.02) | −0.051* (0.02 | −0.050* (0.02) | −0.055 (0.03) | −0.059** (0.02) | −0.093* (0.04) |

| Pre-Katrina Body Mass Index | 0.887*** (0.03) | 0.887*** (0.03) | 0.887*** (0.03) | 0.883*** (0.03) | 0.883*** (0.03) | 0.828*** (0.04) | 0.899*** (0.03) | 0.832*** (0.04) |

| Pre-Katrina County Sprawl Index | 0.009 (0.01) | 0.011 (0.01 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.006 (0.01) | 0.005 (0.0 | −0.005 (0.01) | −0.003 (0.02) |

| Age in years at baseline | 0.03 (0.05 | 0.025 (0.05) | 0.032 (0.05) | 0.028 (0.06) | −0.042 (0.08) | −0.06 (0.08) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (reference = non-Hispanic White) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.135 (0.87) | 0.146 (0.88) | 0.557 (0.93) | 0.567 (0.95) | 0.062 (1.14) | −1.36 (1.36) | ||

| Hispanic | 1.071 (1.59) | 1.062 (1.6) | 1.945 (1.73) | 0.875 (1.9) | −0.981 (3.71) | −1.514 (3.88) | ||

| Other race/ethnicity | 0.772 (1.7) | 0.785 (1.7) | 1.116 (1.73) | 1.056 (1.74) | −0.964 (2.59) | −0.911 (3.84) | ||

| Male (reference = female) | 0.483 (0.85) | 0.468 (0.86) | 0.156 (0.88) | −0.11 (0.94) | 1.215 (1.5) | 1.482 (1.7) | ||

| Number of children at baseline | 0.054 (0.19) | 0.073 (0.19) | 0.02 (0.21) | 0.255 (0.33) | 0.756* (0.38) | |||

| Received cash assistance/welfare at baseline | −0.196 (0.62) | −0.208 (0.64) | −0.044 (0.85) | −0.163 (0.92) | ||||

| Generalized Social Support Scale at baseline (1 = low, 4 = high) | 0.035 (0.48) | −0.826 (0.66) | −0.061 (0.73) | |||||

| Number of traumas suffered due to Hurricane Katrina | 0.059 (0.11) | 0.104 (0.12) | ||||||

| Close friend or family member killed as a result of Hurricane Katrina or Rita | 1.109 (0.66) | 0.897 (0.73) | ||||||

| Employed post-Katrina | −0.65 (0.5) | −0.94 (0.65) | ||||||

| Total household income post-Katrina | 0 (0) | −0.001* (0) | ||||||

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Results were consistent when we adjusted for age, race, welfare status, number of children, hurricane-related trauma exposure, gender, and social support, either individually or in fully adjusted multivariable models. Although the sprawl-BMI association was robust to covariate adjustment across all models, confidence intervals widened to include zero when we controlled for the number of hurricane-related traumas reported by participants. This drop in the statistical significance of a stable sprawl parameter estimate reflects the fact that roughly half the sample was missing data on hurricane-related trauma. Consistency across models suggests that observed associations are unlikely to have been confounded by self-selection into neighborhoods. The association between post-Katrina sprawl and BMI was not attenuated after adjusting for employment status and/or total household income, meaning that the sprawl index is not simply functioning as a marker of economic opportunity. In fact, it appears that not adjusting for these factors may mask associations between sprawl and BMI; after adding socioeconomic variables to the model, the coefficient for sprawl nearly doubled from −.05 to −.09 and remains statistically significant. As a sensitivity analysis, we refit all eight models presented in Table 3 with an additional control for distance between pre- and post-Katrina address. Associations between sprawl and BMI estimated in distance-adjusted models were stable when compared to each of the original models. For example, refitting our most basic model that controlled only for baseline sprawl and BMI (Table 3 Model 1), the sprawl coefficient dropped slightly from .047 kg/m2 (p=.02) to .044 kg/m2 (p=. 03) of BMI after adjusting for distance. Covariate adjusted models behaved similarly; the sprawl coefficient estimated from fully adjusted Model 8 remained stable at .09 kg/m2 after adjusting for distance, though statistical significance dropped slightly from p=.01 to p=.04. No models produced substantively different sprawl effect sizes or statistical significance after adjusting for distance.

Models from stratified analyses (Table 4) indicate that sprawl and BMI were associated among those who did, and those who did not, lose a family member or friend as a result of Hurricanes Katrina or Rita. In a fully adjusted model restricted to the bereaved, sample size dropped to 34 and the effect was not statistically significant (p=.1). However, adjusting for baseline and post-Katrina confounders separately provided enough power to show consistent effects of sprawl on BMI that support previous models.

Table 4.

Associations between Post-Katrina Sprawl and BMI (2006–2007), adjusted models and stratified by having experienced the death of close friend or family member

| No close friend or family member killed in Katrina or Rita |

Close friend or family member killed in Katrina or Rita | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully adjusted (Model 8) β (se) | Fully adjusted (Model 8) β (se) | Adjusted for baseline characteristics only (Model 5) β (se) | Adjusted for post-Katrina SES only (Model 7) β (se) | |

| Post-Katrina County Sprawl Index | −0.098* (0.048) | Ȓ0.127 (0.077) | Ȓ0.074* (0.031) | −0.087* (0.041) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Discussion

Among a displaced population, relocation to a more sprawling area was associated with higher BMI. The average increase in sprawl experienced by displaced RISK participants corresponds to a 4.3 kg weight gain for 1.7 meter tall individuals. At a height of 1.7 meters and a baseline BMI at the sample’s mean of 28.8, this change represents a 5% increase in body weight. Although our observational data do not allow us to rule out endogeneity as an explanation, the association does not appear to be driven by self-selection into more sprawling counties, nor confounded by differences in economic outcomes for residents of sprawling versus more urban areas. We note several additional limitations. First, the analysis includes a relatively small sample size, although power was sufficient to show statistically significant associations. Second, caution should be observed in generalizing these findings to other populations, as the study cohort was drawn from a single geographic area and comprises mostly young, African American, female, and low-income parents.

Third, the county sprawl index presents methodological challenges. This measure characterizes the built environment at the county-level, but sprawl could influence behavior on smaller or larger geographic scales. It is also possible that participants living on the edge of a county could spend the majority of their time in an adjacent county. However, both of these concerns threaten to result in nondifferential exposure misclassification; although the county sprawl index may not capture neighborhood characteristics well for all participants, we do not expect the measure to function better or worse according to BMI or displacement experiences. In other words, exposure misclassification induced by imprecisely measured sprawl would add “noise” to our data, likely biasing results towards the null such that associations may be even stronger than those presented. Our findings may have limited policy relevance in rural areas, as the county sprawl index was designed and calculated for US metropolitan counties only. Finally, previous literature suggests that compact land uses may protect against weight gain by providing opportunities for active travel (de Nazelle et al., 2011; Sallis et al., 2012), but we did not have the data to explore specific mechanisms.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, this study contributes new information to ongoing debates about whether endogeneity and self-selection into neighborhoods explain observed associations between the built environment and BMI(Handy et al., 2006)(Eid et al., 2007; Frank et al., 2007) by using natural experiment data to better isolate causal effects. In the context of disaster research, we note that post-disaster planning should consider how evacuees can access neighborhoods that support health. More broadly, these findings add to a growing evidence base that the built environment can foster changes in weight, underscoring the need to integrate health into public dialogue about land use planning. Zoning laws, subdivision regulations, and other policies that regulate land use and development may have the power to help to slow, and potentially reverse, the tide of the obesity epidemic.

Highlights.

We investigate the effect of sprawl on body mass index among a displaced population

Relocation to more sprawling areas was associated with weight gain

Results did not appear to be driven by self-selection into neighborhoods

Acknowledgements

This paper was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HD046162, RO1HD057599, the National Science Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation. SVS is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Award in Health Policy. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mariana Arcaya, Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard School of Public Health; Cambridge, MA, USA; marcaya@hsph.harvard.edu.

Peter James, Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health; Boston, MA, USA; pjames@hsph.harvard.edu.

Jean Rhodes, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Boston; Boston, MA, USA; Jean.Rhodes@umb.edu.

Mary C Waters, Department of Sociology, Harvard University; Cambridge, MA, USA; mcw@wjh.harvard.edu.

S V Subramanian, Department of Society, Human Development and Health, Harvard School of Public Health; Boston, MA, USA; svsubram@hsph.harvard.edu.

References

- Arcaya M, Subramanian PSV. Ecological Inferences and Multilevel Studies. In: Fischer MM, Nijkamp P, editors. Handbook of Regional Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 1335–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Weltzien E, Altman D, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Experiences of hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters: implications for future planning. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1402–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, Birch LL, Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, Durant N, Dutton G, Foster EM, et al. Myths, Presumptions, and Facts about Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:446–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1208051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell D. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- de Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Anto JM, Brauer M, Briggs D, Braun-Fahrlander C, Cavill N, Cooper AR, Desqueyroux H, et al. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: a review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ Int. 2011;37:766–777. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 1998;88:216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand CP, Andalib M, Dunton GF, Wolch J, Pentz MA. A systematic review of built environment factors related to physical activity and obesity risk: implications for smart growth urban planning. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:e173–e182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid J, Overman H, Puga D, Turner M. Fat City: Questioning the Relationship Between Urban Sprawl and Obesity. Journal of Urban Economics. 2007;63:385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Brownson RC, Berrigan D. Relationship between urban sprawl and weight of United States youth. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:464–474. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Schmid T, Killingsworth R, Zlot A, Raudenbush S. Relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;18:47–57. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Saelens BE, Powell KE, Chapman JE. Stepping towards causation: do built environments or neighborhood and travel preferences explain physical activity, driving, and obesity? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1898–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E. Help from Family, Friends, and Strangers during Hurricane Katrina: The Limits of Social Networks. In: Weber L, Peek LA, editors. Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora. 1st ed. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2012. pp. 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Handy S, Cao X, Mokhtarian P. Self-Selection in the Relationship between the Built Environment and Walking: Empirical Evidence from Northern California. 2006;72(1):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- James P, Troped PJ, Hart JE, Joshu CE, Colditz GA, Brownson RC, Ewing R, Laden F. Urban sprawl, physical activity, and body mass index: Nurses' Health Study and Nurses' Health Study II. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:369–375. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Kling JR, Liebman JB. Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Early Results of a Randomized Mobility Experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001;116:607–654. [Google Scholar]

- Lee IM, Ewing R, Sesso HD. The built environment and physical activity levels: the Harvard Alumni Health Study. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to opportunity: an experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1576–1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupere V. Moving to Opportunity: does long-term exposure to 'low-poverty' neighborhoods make a difference for adolescents? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Harmer P, Cardinal BJ, Bosworth M, Johnson-Shelton D, Moore JM, Acock A, Vongjaturapat N. Built environment and 1-year change in weight and waist circumference in middle-aged and older adults: Portland Neighborhood Environment and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:401–408. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Shen M, Gowda D, Sanchez B, Shea S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Jackson SA. Relation between neighborhood environments and obesity in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1349–1357. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O. Ferdinand A, Sen B, Rahurkar S, Engler S, Menachemi N. The Relationship Between Built Environments and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e7–e13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantinga A, Bernell S. The association between urban sprawl and obesity: Is it a two-way street? Journal of Regional Science. 2007;47:857–879. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Floyd MF, Rodriguez DA, Saelens BE. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012;125:729–737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Conway TL, Slymen DJ, Cain KL, Chapman JE, Kerr J. Neighborhood built environment and income: examining multiple health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart Growth America. Measuring sprawl and its impact: the character and consequences of urban expansion. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, Lipnick R, Speizer FE, Rosner B, Cramer D, Hennekens CH. Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:651–658. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]