Abstract

Highly iterated palindromes (HIP) have been used as high resolution molecular markers for assessing the genetic variability and phylogenetic relatedness of heterocystous cyanobacteria (subsections IV and V) representing 12 genera of heterocystous cyanobacteria, collected from different geographical areas of India. DNA fingerprints generated using four HIP markers viz. HIP-AT, HIP-CA, HIP-GC, and HIP-TG showed 100 % polymorphism in all the heterocystous cyanobacteria studied and each marker produced unique and strain-specific banding pattern. Furthermore, phylogenetic affinities based on the dendrogram constructed using HIP DNA profiles of heterocystous cyanobacteria suggest the monophyletic origin of this entire heterocystous clade along with a clear illustration of the polyphyletic origin of the branched Stigonematalean order (Subsection V). In addition, phylogenetic affinities were validated by principal component analysis of the HIP fingerprints. The overall data obtained by both the phylogeny and principal component assessments proved that the entire heterocystous clade was intermixed, and there are immediate needs for classificatory reforms that satisfy morphological plasticity and environmental concerns.

Keywords: Heterocystous cyanobacteria, Highly iterated palindromes, Phylogeny, Principal component analysis

Introduction

Cyanobacteria, an ancient gram-negative photosynthetic group of prokaryotes, are one of the most ubiquitously found groups of microbial species on earth (Henson et al. 2004). Evolutionary assessments of cyanobacteria have indicated towards a sluggish pace of evolution as indicated by the similarity of the present forms to the fossilized forms (Henson et al. 2002). The occurrence of cyanobacteria in fresh water blooms, marine ecosystems, rice fields, within limestone, salt subjugated lands, deserts, polar environments, and in symbiotic associations highlights their inherent and genetic abilities to survive comfortably in the above niches and thus comprise a highly diverse and robust clade of prokaryotes (Sigler et al. 2003).

The phylogeny of filamentous heterocystous cyanobacteria that has been inferred from various morphological as well as physiological attributes has brought about the problem of misidentification because morphological and physiological resemblances may not necessarily reflect genetic relatedness (Komárek and Anagnostidis 1989; Ward et al. 1998). This problem has attracted the attention of researchers worldwide which has led to the evolution of more reliable methods for assessing cyanobacterial taxonomy and diversity like DNA base composition studies (Kaneko et al. 2001), DNA hybridization-based assessments (Kondo et al. 2000), gene sequencing approaches (Nübel et al. 1997), and PCR fingerprinting strategies (Versalovic et al. 1991; Rasmussen and Svenning 1998; Shalini and Gupta 2008)

PCR-based techniques based especially on DNA polymorphism and fingerprinting of repetitive DNA fragments have been developed and applied in cyanobacterial phylogenetic studies. RFLP (Iteman et al. 2002), RAPD (Prabina et al. 2005), STRR (Wilson et al. 2000; Chonudomkul et al. 2004; Valério et al. 2009; Akoijam and Singh 2011), and highly iterated palindromes (HIP1) (Orcutt et al. 2002; Zheng et al. 2002; Neilan et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2005) have been attempted with an overall aim to provide better resolution amongst closely related species. The highly iterated palindromes, commonly referred to as HIP1, are a repetitive eight-base sequence (5′GCGATCGC3′) which have been known to be exclusively over-represented in the cyanobacterial genome and more importantly have been regarded to have immense evolutionary footprints because of them being recombinational hotspots (Smith et al. 1998; Selvakumar and Gopalaswamy 2008). The existence of these repetitive sequences was for the first time reported in calcium tolerant strain Synechococcus PCC 6301 (Gupta et al. 1993). Thereafter, repetitive sequences have been widely considered as one of the most accepted tools for assessing the microbial diversity, particularly at a very high resolution in case of closely related microbes representing the same genus (Lee et al. 1996; Garcia-Pichel et al. 2001; Gugger et al. 2002; Roeselers et al. 2007; Valério et al. 2009).

Till now, there have been no well-documented reports on the use of the HIP sequences as high resolution markers for investigating the phylogeny and genetic diversity of heterocystous cyanobacteria and therefore the present communication deals with the use of HIP fingerprinting patterns as a differentiating high resolution molecular marker to assess the genetic diversity of 41 heterocystous cyanobacterial strains representing 12 genera. Further, principal component analysis (PCA) has also been done to assess the consistency of the fingerprinting data along with trying to decipher that whether both the approaches were in coherence or not. Overall, it is a broad attempt to test the genetic diversity, genetic proximity, and genetic affiliations of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria representing both the branched and the unbranched heterocystous lineages.

Materials and methods

Growth and maintenance of cyanobacteria

Forty one heterocystous cyanobacterial strains representing different geographical regions (Table 1) and habitats of India were grown axenically in 150 ml basal medium (BG-110 medium) (Rippka et al. 1979) in Erlenmeyer flasks (capacity 250 ml). The identification of the cyanobacteria was done using the keys of Desikachary (1959). Culture conditions were maintained as per Singh et al. 2013.

Table 1.

List of heterocystous cyanobacteria used in the present study

| S. No | Cyanobacteria | Geographical location/Collection sites |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | A. doliolum Ind 1 | Pond, IIT BHU Workshop, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 2. | A. doliolum Ind 2 | Pond, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 3. | A. oryzae Ind 3 | Dried water body, Vishwanath Temple, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 4. | A. oryzae Ind 4 | Dried water body, Vishwanath Temple, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 5. | Anabaena sp. Ind 5 | Pond, IIT BHU Workshop, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 6. | Anabaena sp. Ind 6 | Paddy field, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 7. | Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8 | Water tank, Mandapum Sea Beach, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India |

| 8. | C. brevissima Ind 9 | Humid and moist rocky crevices as epiphytes on Hydrodictyon, Windham Falls, Barkachha South campus, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 9. | C. brevissima Ind 10 | Bee Falls, Panchamarhi, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| 10. | Calothrix sp. Ind 11 | Panchamarhi, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| 11. | C. muscicola Ind 12 | Paddy field, Agricultural Farm, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 12. | C. muscicola Ind 13 | Paddy Field, Raksaul, Bihar, India |

| 13. | Cylindrospermum sp. Ind 14 | Paddy field, Agricultural Farm, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 14. | C. stagnale Ind 15 | Stagnant waters of paddy field, Agricultural Farm, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 15. | T. tenuis Ind 16 | Pallikaranai Marsh Reserve Forest, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India |

| 16. | T. nodosa Ind 17 | Nanmangalam Reserved Forest, Medavakkam, Tamil Nadu, India |

| 17. | Westiellopsis sp. Ind 19 | Humid and moist rocky crevices, Windham Falls, Barkachha South Campus, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 18. | Westiellopsis sp. Ind 20 | Inside rocky and humid crevices, Arunachal Pradesh, India |

| 19. | H. welwitschii Ind 21 | IARI campus, Centre for collection and utilization of Blue Green Algae (CCUBGA), PUSA, New Delhi, India |

| 20. | H. welwitschii Ind 22 | Doimukh, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh, India |

| 21. | Hapalosiphon sp. Ind 23 | Paddy field, Barkachha South Campus, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 22. | S. bohnerii Ind 24 | Pond in a humid subtropical environment with intervening monsoons, near the IIT BHU Workshop, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 23. | S. bohnerii Ind 25 | Dripping rocks, Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, India |

| 24. | Fischerella sp. Ind 26 | Paddy field, Babatpur, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 25. | Nostochopsis sp. Ind 28 | Soil of paddy field, Narayanpur, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 26. | M. laminosus Ind 29 | Muddy paddy field, Jalandhar, Punjab, India |

| 27. | N. calcicola Ind 30 | Dried Pond, Dept. of Botany, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 28. | N. calcicola Ind 31 | Paddy field, Nashik, Maharashtra, India |

| 29. | N. calcicola Ind 32 | Dried water body, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 30. | N. muscorum Ind 33 | Paddy field, Agricultural Farm, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 31. | N. muscorum Ind 34 | Freshwater pond, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 32. | Nostoc sp. Ind 36 | Paddy field almost devoid of water, Arunachal Pradesh, India |

| 33. | Nostoc sp. Ind 37 | Fresh Water Pond, Arunachal Pradesh, India |

| 34. | Nostoc sp. Ind 39 | Paddy field, Nashik, Maharashtra, India |

| 35. | Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1 | Paddy field, Nashik, Maharashtra, India |

| 36. | Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2 | Paddy field, Nashik, Maharashtra, India |

| 37. | Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3 | Paddy field, Nashik, Maharashtra, India |

| 38. | N. spongiaeforme Ind 41 | Water body, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 39. | N. spongiaeforme Ind 42 | Water Body, Botanical Garden, Dept. of Botany, Banaras Hindu University, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| 40. | Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 Ind 43 | Laboratory of Prof. Peter Wolk, University of Michigan, USA |

| 41. | Fischerella sp. Ind 81 | Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India |

Genomic DNA Isolation and PCR conditions

DNA was isolated from 8-day-old cultures using Himedia Ultrasensitive Spin Purification Kit (MB505). The DNA eluted was stored at −20 °C. All the PCR amplifications were performed in 25 μl aliquots containing 10–20 ng DNA template, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, and 1U/μl Taq DNA polymerase (Merck, India). For all the highly iterated palindrome (HIP) variants (HIP-AT; 5′-GCGATCGCAT-3′, HIP-CA; 5′-GCGATCGCCA-3′, HIP-GC; 5′-GCGATCGCGC-3′, and HIP-TG; 5′-GCGATCGCTG-3′), thermal cycling conditions began with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 30 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s; and one cycle of 72 °C for 5 min (Smith et al. 1998). The amplified gene products were visualized on Bio Rad Gel Documentation system after running in 1.2 % agarose gels.

Phylogenetic analysis of fingerprints

The generated HIP profiles were run on agarose gels of the same concentration for differentiating the strong and the dubious signals/bands. The presence or absence of distinct and reproducible bands in each of the individual DNA fingerprinting pattern generated by HIP-AT, HIP-CA, HIP-GC, and HIP-TG PCR profiles was converted into binary data, and the pooled binary data were used to construct a composite dendrogram, respectively. The BioDiversity Pro software (vers. 2) was used to perform the hierarchical analyses using the Jaccard cluster analysis option. All the reactions were repeated three times.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis was performed for the fingerprints of all the 41 strains in all the four parameters. The software Sigmaplot 11 was used to generate the graphical representation of the values generated by principal component analysis.

Results

Highly iterated palindrome PCR fingerprinting

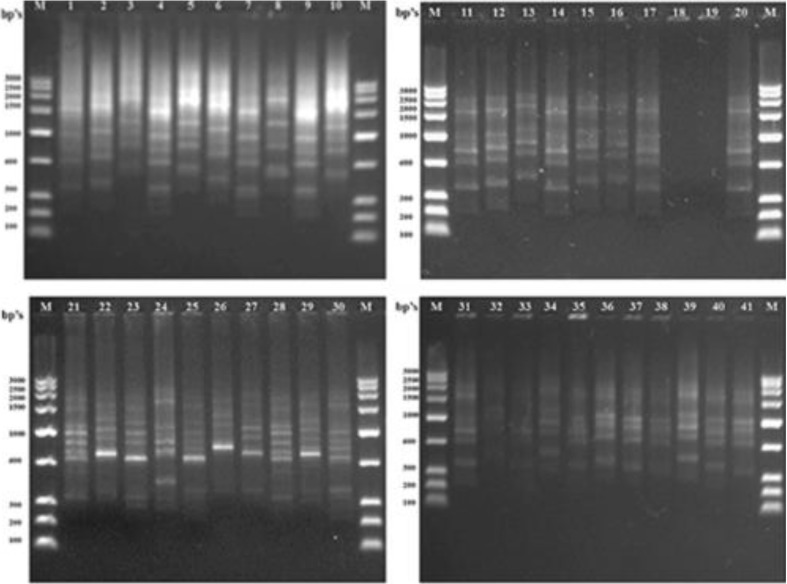

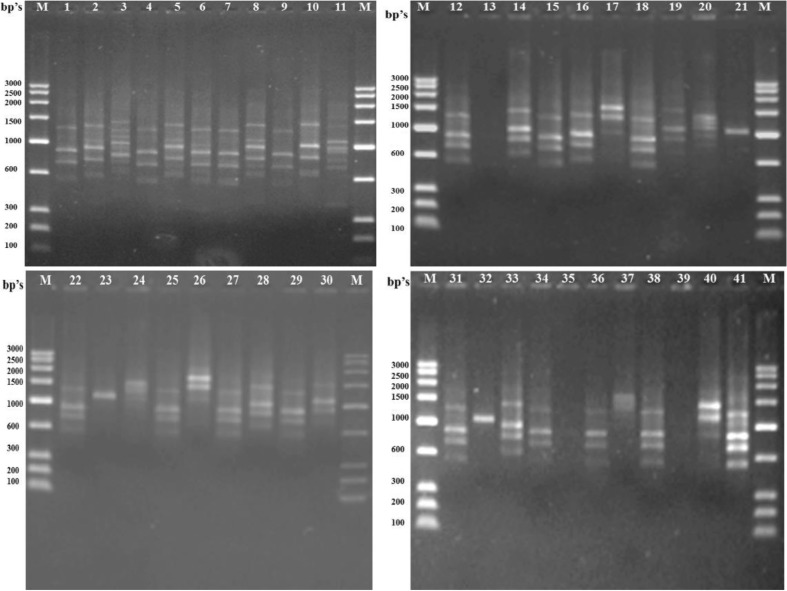

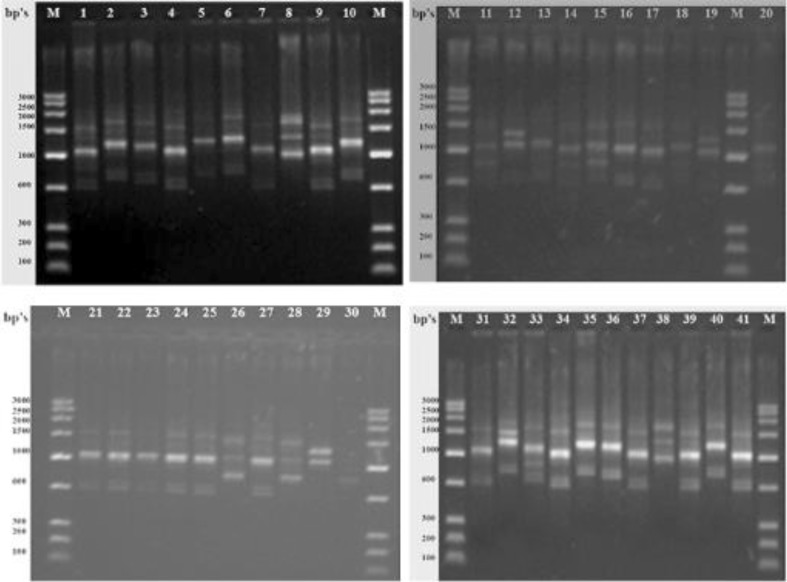

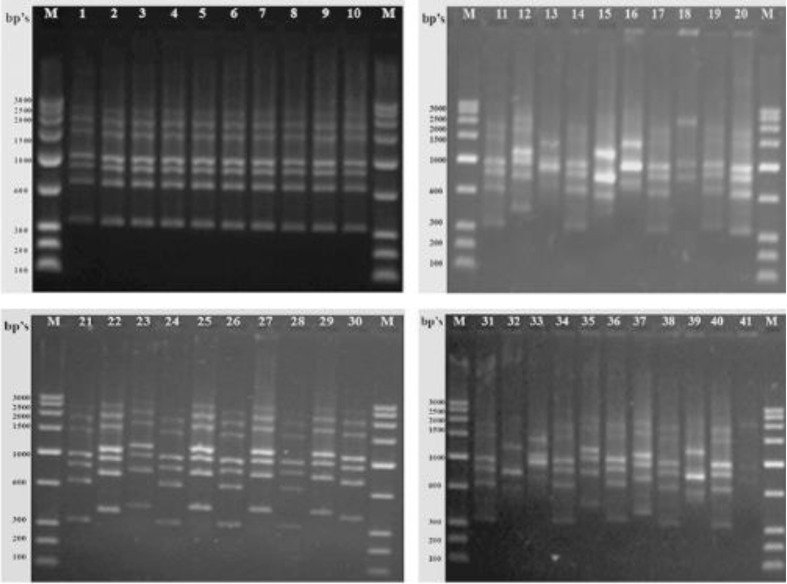

All the markers used, i.e., HIP-AT, HIP-CA, HIP-GC, and HIP-TG, exhibited 100 % polymorphism in all the 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria studied and no similar patterns were evident in any of the markers. The HIP-AT fingerprints revealed bands ranging in size from 100–200 to 2,000–2,500 bp with the maximum bands being present in the range 900–1,000 and 600–700 bp with probabilities of patterns being prominent calculated at 98.55 and 99.64 %, respectively. The maximum visible profiles were noted in Cylindrospermum muscicola Ind13 with six bands (Fig. 1). The HIP-CA fingerprints revealed bands ranging in size from 100–200 to 1,400–1,600 bp with the maximum bands being present in the range 1,200–1,400, 900–1,000, and 800–900 bp with probabilities of patterns being prominent calculated at 99.94, 99.88, and 99.97 %, respectively. The maximum numbers of bands were observed in Anabaena oryzae Ind3, Calothrix brevissima Ind9, Cylindrospermum muscicola Ind12, Hapalosiphon welwitschii Ind22, and Fischerella sp. Ind81 with five bands each (Fig. 2). The HIP-GC fingerprints revealed bands ranging in size from 100–200 to 1,400–1,600 bp with the maximum bands being present in the range 1,000–1,200 bp with probabilities of patterns being prominent calculated at 99.99 %. The maximum visible patterns were seen in Nostoc sp. Ind36 and Nostoc sp. Ind37 with five bands each (Fig. 3). The HIP-TG fingerprints revealed bands ranging in size from 2,000–2,500 to 1,400–1,600 bp with the maximum bands being present in the range 1,000–1,200 bp with probabilities of patterns being prominent calculated at 99.99 %. The maximum visible DNA bands were present in Anabaena doliolum Ind1, Hapalosiphon sp. Ind23, Scytonema bohnerii Ind24, Nostochopsis sp. Ind28, Mastigocladus laminosus Ind29, Nostoc calcicola Ind30, N. calcicola Ind32, and Nostoc muscorum Ind33 with seven bands each (Fig. 4). Thus, the molecular fingerprints using HIP sequences as primers, generated strain-specific profiles of heterocystous cyanobacteria belonging to the Nostocales and Stigonematales orders.

Fig. 1.

Gel photograph showing DNA fingerprints of HIP-AT. Lane M Molecular weight marker (100 bp); Lane (1–41) 1 A. doliolum Ind 1; 2 A. doliolum Ind 2; 3 A. oryzae Ind 3; 4 A. oryzae Ind 4; 5 Anabaena sp. Ind 5; 6 Anabaena sp. Ind 6; 7 Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8; 8 C. brevissima Ind 9; 9 C. brevissima Ind 10; 10 Calothrix sp. Ind 11; 11 C. muscicola Ind 12; 12 C. muscicola Ind 13; 13 Cylindrospermum sp. Ind 14; 14 Cylindrospermum stagnale Ind 15; 15 Tolypothrix tenuis Ind 16; 16 Tolypothrix nodosa Ind 17; 17 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 19; 18 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 20; 19 H. welwitschii Ind 21; 20 H. welwitschii Ind 22; 21 Hapalosiphon sp. Ind 23; 22 S. bohnerii Ind 24; 23 S. bohnerii Ind 25; 24 Fischerella sp. Ind 26; 25 Nostochopsis sp. Ind 28; 26 M. laminosus Ind 29; 27 N. calcicola Ind 30; 28 N. calcicola Ind 31; 29 N. calcicola Ind 32; 30 N. muscorum Ind 33; 31 N. muscorum Ind 34; 32 Nostoc sp. Ind 36; 33 Nostoc sp. Ind 37; 34 Nostoc sp. Ind 39; 35 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1; 36 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2; 37 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3; 38 Nostoc spongiaeforme Ind 41; 39 N. spongiaeforme Ind 42; 40 Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 Ind 43; 41 Fischerella sp. Ind 81

Fig. 2.

DNA fingerprinting pattern generated in 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria using HIP-CA primer. Lane M Molecular weight marker (100 bp); Lane (1–41) 1 A. doliolum Ind 1; 2 A. doliolum Ind 2; 3 A. oryzae Ind 3; 4 A. oryzae Ind 4; 5 Anabaena sp. Ind 5; 6 Anabaena sp. Ind 6; 7 Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8; 8 C. brevissima Ind 9; 9 C. brevissima Ind 10; 10 Calothrix sp. Ind 11; 11 C. muscicola Ind 12; 12 C. muscicola Ind 13; 13 Cylindrospermum sp. Ind 14; 14 C. stagnale Ind 15; 15 T. tenuis Ind 16; 16 T. nodosa Ind 17; 17 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 19; 18 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 20; 19 H. welwitschii Ind 21; 20 H. welwitschii Ind 22; 21 Hapalosiphon sp. Ind 23; 22 S. bohnerii Ind 24; 23 S. bohnerii Ind 25; 24 Fischerella sp. Ind 26; 25 Nostochopsis sp. Ind 28; 26 M. laminosus Ind 29; 27 N. calcicola Ind 30; 28 N. calcicola Ind 31; 29 N. calcicola Ind 32; 30 N. muscorum Ind 33; 31 N. muscorum Ind 34; 32 Nostoc sp. Ind 36; 33 Nostoc sp. Ind 37; 34 Nostoc sp. Ind 39; 35 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1; 36 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2; 37 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3; 38 N. spongiaeforme Ind 41; 39 N. spongiaeforme Ind 42; 40 Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 Ind 43; 41 Fischerella sp. Ind 81

Fig. 3.

Gel photograph showing DNA fingerprints of heterocystous cyanobacteria using HIP-GC primer. Lane M Molecular weight marker (100 bp); Lane (1–41) 1 A. doliolum Ind 1; 2 A. doliolum Ind 2; 3 A. oryzae Ind 3; 4 A. oryzae Ind 4; 5 Anabaena sp. Ind 5; 6 Anabaena sp. Ind 6; 7 Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8; 8 C. brevissima Ind 9; 9 C. brevissima Ind 10; 10 Calothrix sp. Ind 11; 11 C. muscicola Ind 12; 12 C. muscicola Ind 13; 13 Cylindrospermum sp. Ind 14; 14 C. stagnale Ind 15; 15- T. tenuis Ind 16; 16 T. nodosa Ind 17; 17 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 19; 18 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 20; 19 H. welwitschii Ind 21; 20 H. welwitschii Ind 22; 21 Hapalosiphon sp. Ind 23; 22 S. bohnerii Ind 24; 23 S. bohnerii Ind 25; 24 Fischerella sp. Ind 26; 25 Nostochopsis sp. Ind 28; 26 M. laminosus Ind 29; 27 N. calcicola Ind 30; 28 N. calcicola Ind 31; 29 N. calcicola Ind 32; 30 N. muscorum Ind 33; 31 N. muscorum Ind 34; 32 Nostoc sp. Ind 36; 33 Nostoc sp. Ind 37; 34 Nostoc sp. Ind 39; 35 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1; 36 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2; 37 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3; 38 N. spongiaeforme Ind 41; 39 N. spongiaeforme Ind 42; 40 Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 Ind 43; 41 Fischerella sp. Ind 81

Fig. 4.

DNA fingerprints of heterocystous cyanobacterial strains obtained by using HIP-TG primer. Lane M Molecular weight marker (100 bp); Lane (1–41) 1 A. doliolum Ind 1; 2 A. doliolum Ind 2; 3 A. oryzae Ind 3; 4 A. oryzae Ind 4; 5 Anabaena sp. Ind 5; 6 Anabaena sp. Ind 6; 7 Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8; 8 C. brevissima Ind 9; 9 C. brevissima Ind 10; 10 Calothrix sp. Ind 11; 11 C. muscicola Ind 12; 12 C. muscicola Ind 13; 13 Cylindrospermum sp. Ind 14; 14 C. stagnale Ind 15; 15 T. tenuis Ind 16; 16 T. nodosa Ind 17; 17 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 19; 18 Westiellopsis sp. Ind 20; 19 H. welwitschii Ind 21; 20 H. welwitschii Ind 22; 21 Hapalosiphon sp. Ind 23; 22 S. bohnerii Ind 24; 23 S. bohnerii Ind 25; 24 Fischerella sp. Ind 26; 25 Nostochopsis sp. Ind 28; 26 M. laminosus Ind 29; 27 N. calcicola Ind 30; 28 N. calcicola Ind 31; 29 N. calcicola Ind 32; 30 N muscorum Ind 33; 31 N. muscorum Ind 34; 32 Nostoc sp. Ind 36; 33 Nostoc sp. Ind 37; 34 Nostoc sp. Ind 39; 35 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1; 36 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2; 37 Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3; 38 N. spongiaeforme Ind 41; 39 N. spongiaeforme Ind 42; 40 Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 Ind 43; 41 Fischerella sp. Ind 81

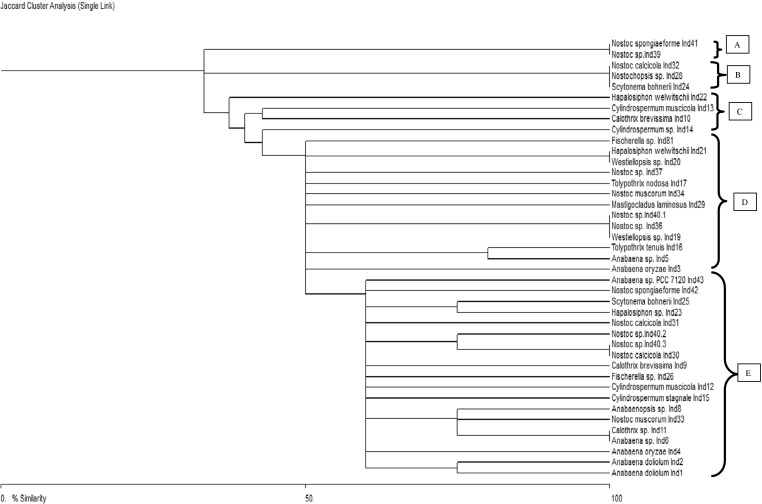

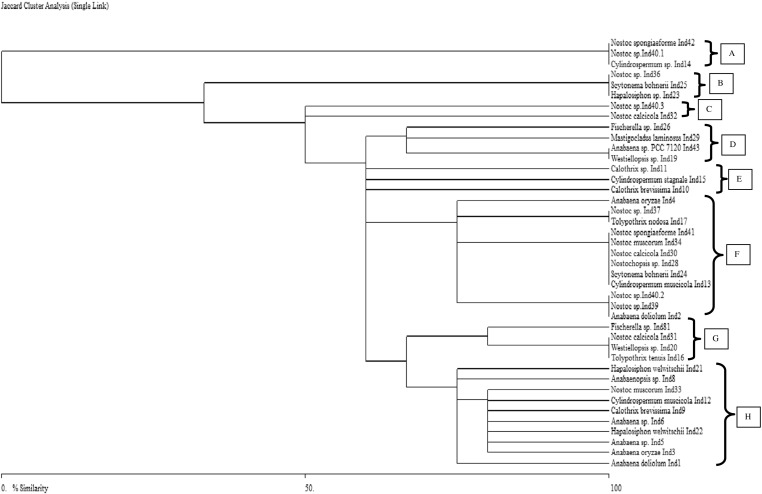

Phylogeny of heterocystous cyanobacteria using HIP-fingerprints

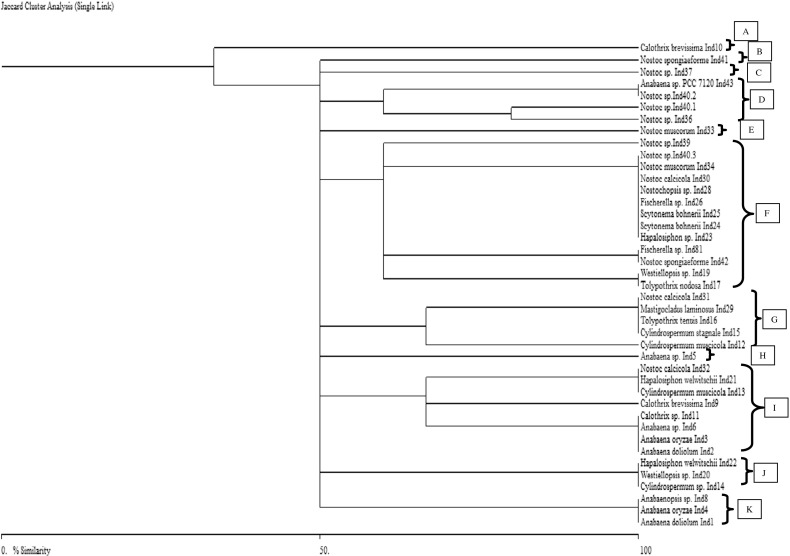

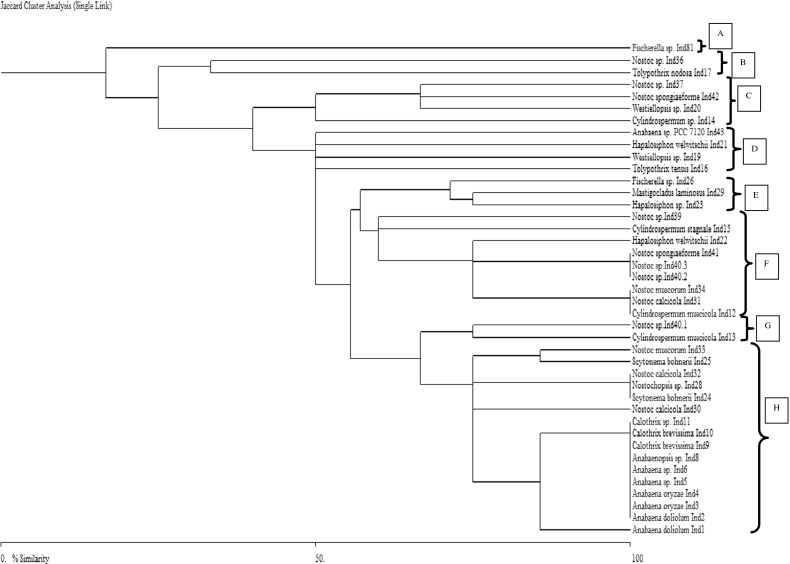

The HIP-AT fragments-based phylogenetic tree showed the presence of five major clusters A, B, C, D, and E. The cluster E was the largest and had representatives of both the unbranched and the branched clades (Fig. 5). Apart from the cluster A, which had only two members of the genus Nostoc, the rest of all the clusters had members of both the Nostocales and Stigonematales groups. The HIP-CA tree had eight major clusters, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. In this tree, clusters A and E had members of only the Nostocales orders while rest of the clusters had members of both the Nostocales and Stigonematales orders present (Fig. 6). Clusters F and H were the larger clusters while the rest were small assemblages. The HIP-GC phylogenetic tree revealed the presence of 11 clusters out of which the cluster F was the largest one followed by the cluster I in terms of members present. Here also, definitely clustered groups of Nostocales and Stigonematales were not evident in most of the well-represented groups (Fig. 7). The HIP-TG phylogenetic patterns also were more or less similar like the rest of the trees with eight major clusters and cluster H being the largest (Fig. 8). Thus, phylogenetic trees constructed using HIP DNA profiles suggest that the entire heterocystous clade representing both unbranched and branched was monophyletic in origin.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic relationships of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria based on HIP-AT fingerprints

Fig. 6.

Dendrogram based on HIP-CA fingerprints reflecting the phylogenetic relationships among heterocystous cyanobacterial strains

Fig. 7.

Dendrogram based on HIP-GC fingerprints depicting the phylogenetic relatedness among 41 heterocystous cyanobacterial strains

Fig. 8.

Phylogenetic relationships of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria based on HIP-TG fingerprinting profile

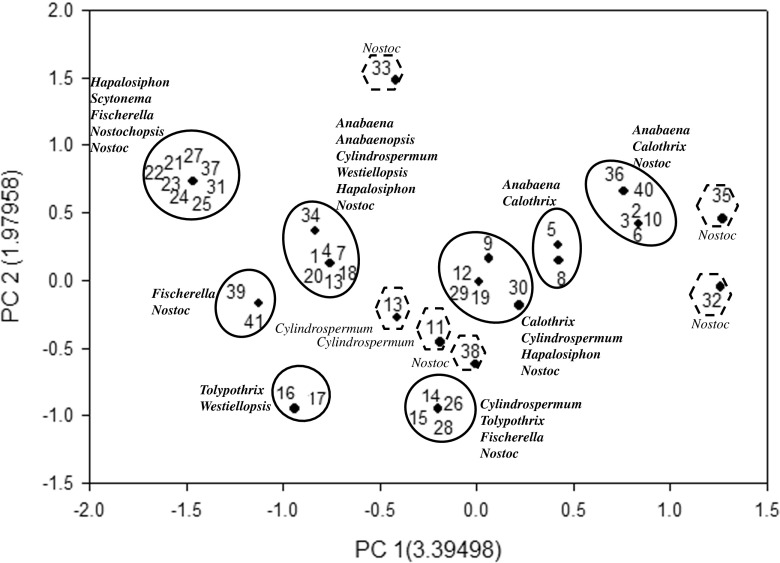

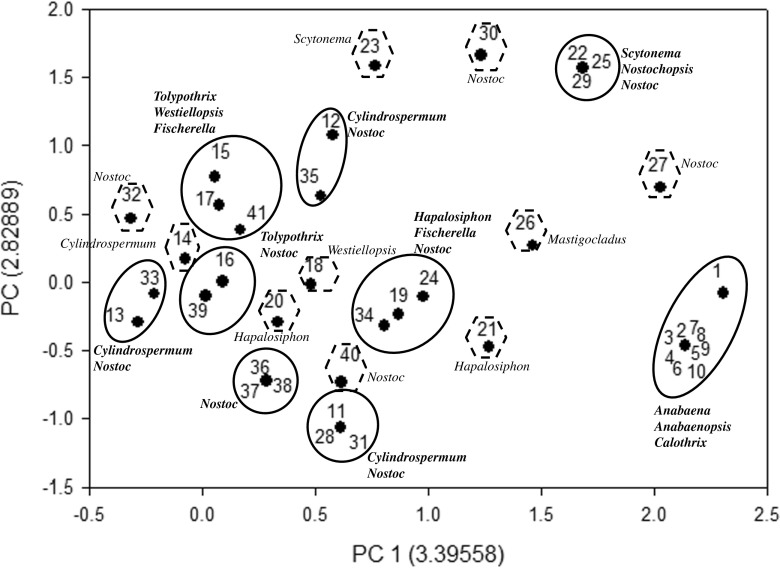

Principal component analysis of heterocystous cyanobacteria based on HIP Fingerprints

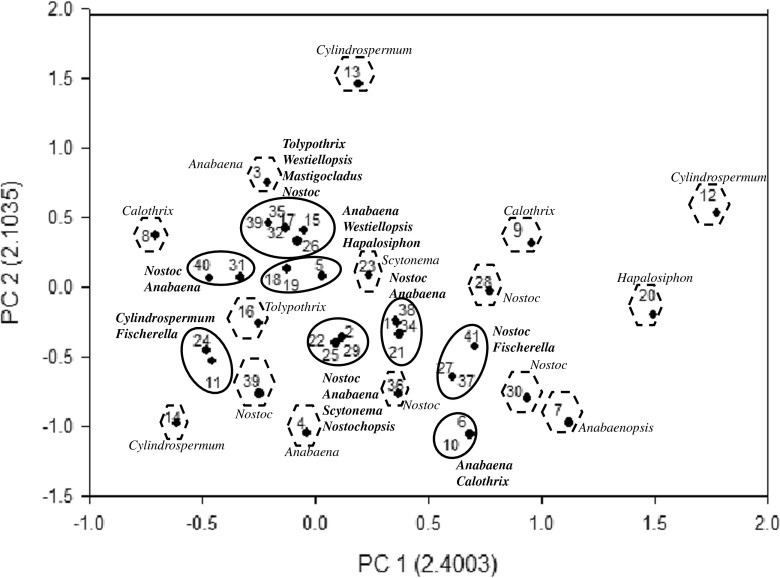

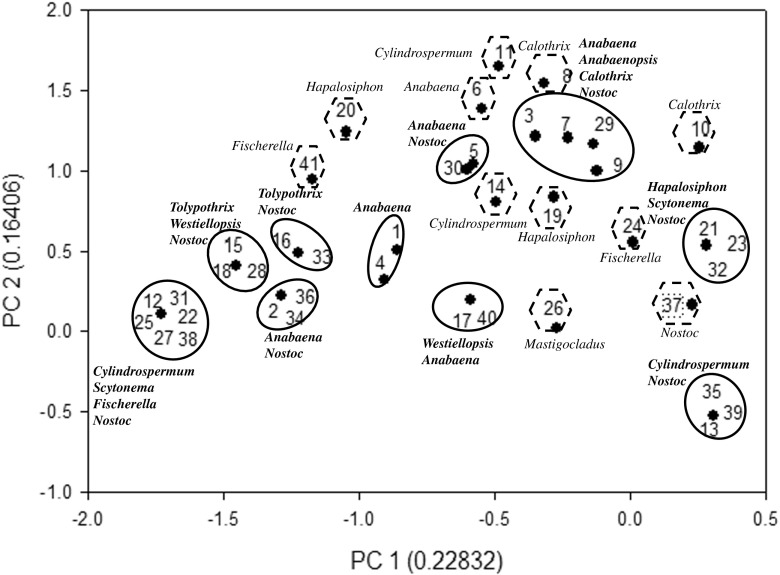

Furthermore, the fingerprints obtained using HIP sequences were utilized for the principal component analysis in order to validate whether the phylogenetic trees (genetic relatedness and genetic proximity) were in coherence with PCA or not. In the HIP-AT analysis, PCA revealed the presence of eight major and 15 minor clusters (Fig. 9). In the major clusters, Nostoc and Anabaena settled into five clusters, Fischerella and Westiellopsis divided into two clusters while Cylindrospermum, Tolypothrix, Mastigocladus, Hapalosiphon, and Scytonema divided into single clusters. The PCA analysis of the HIP-CA fingerprints showed the presence of ten major clusters and 11 minor clusters (Fig. 10). Amongst the major clusters, it was evident that Nostoc participated in eight clusters followed by Anabaena in five, Cylindrospermum, Scytonema, Tolypothrix, and Westiellopsis forming two groups while Fischerella, Anabaenopsis, Calothrix, and Hapalosiphon participated in one group each. In the HIP-GC analysis, PCA showed the presence of eight major and six minor clusters (Fig. 11). Amongst the major clusters, Nostoc strains assembled into six clusters; Hapalosiphon, Fischerella, Anabaena, Cylindrospermum, and Calothrix divided into three clusters; Westiellopsis and Tolypothrix divided into two clusters each; and Scytonema, Nostochopsis, and Anabaenopsis settled into single clusters. The HIP-TG PCA revealed the presence of nine major and ten minor clusters (Fig. 12). In the major clusters, Nostoc occupied seven clusters followed by Cylindrospermum in three; Tolypothrix and Fischerella in two; and Anabaena, Anabaenopsis, Calothrix, Scytonema, Nostochopsis, Hapalosiphon, and Westiellopsis in one cluster, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Principal component analysis based on PCR fingerprints of heterocystous cyanobacterial strains using HIP-AT marker

Fig. 10.

Principal component analysis of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria using HIP-CA as a molecular marker

Fig. 11.

Principal component analysis of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria using fingerprints obtained based on HIP-GC marker

Fig. 12.

Principal component analysis of 41 heterocystous cyanobacteria using the HIP-TG marker

Discussion

The advent of tools of molecular biology has revolutionized classical phylogenetic assessments and thus molecular markers have become an indispensable frame for studying and analyzing classical systematics and taxonomy of heterocystous cyanobacteria (Komárek and Mareš 2012). The presence of highly iterated palindromic sequences in many cyanobacteria has also helped in cyanobacterial molecular typing based on the DNA amplification between the adjacent repeated HIP sequences present in the chromosomal DNA of cyanobacteria (Smith et al. 1998; Robinson et al. 1995; Selvakumar and Gopalaswamy 2008).

In the present study that focused on 12 heterocystous cyanobacterial genera and 41 cyanobacterial strains in total, the HIP primers and their resolution were found to be sufficient for estimating the phylogenetic relationships amongst heterocystous cyanobacteria. The dendrograms constructed using HIP fingerprints (HIP-AT, HIP-CA, HIP-GC, and HIP-TG) showed that the genus Nostoc was most genetically heterogeneous and advanced amongst all the 12 genera (Rajaniemi et al. 2005; Svenning et al. 2005; Willame et al. 2006). One of the interesting features was the differential alignment of the strains Nostoc sp. Ind 40.1, Nostoc sp. Ind 40.2, and Nostoc sp. Ind 40.3 in all the dendrograms constructed. Thus, the HIP marker virtually succeeded in differentiating such closely related strains that were isolated from same habitats as it has also been reported by Selvakumar and Gopalaswamy (2008). Apart from this, another trend obtained was the overall diverging clustering tendency amongst the Nostoc strains which shows that the genus Nostoc is genetically diverse and in fact the most heterogeneous amongst all the genera that we studied. The PCA of the Nostoc strains also highlighted the high level of genetic diversity in the genus Nostoc with its representatives contributing maximally in all the major clusters and the minor clusters. Thus, the phylogenetic trees and the PCA gave a clear picture of Nostoc being a robust and genetically heterogeneous member of the cyanobacterial lineage along with possibly being a forerunner of evolutionary advancements. The genus Anabaena which had six strains apart from the strain Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 showed once again, shifting tendencies which were reflected in all the dendrograms constructed, thus highlighting the genetic diversity and the heterogeneity present in this genus (Ezhilarasi and Anand 2010). PCA analysis supported the phylogenetic inferences with Anabaena being the second most diverse member in the study by finding places in many major and minor clusters. Particularly interesting to note was that if we compared the frequency of clustering of Anabaena with other strains, it was maximal with Nostoc, thus once again fueling the debate of merger of these two genera. The genus Cylindrospermum whose four strains were under study, again vehemently supported the intermixing clustering pattern of heterocystous cyanobacteria with all the four strains showing shifting phylogenetic affiliations in all the trees and the PCA analyses along with, showing proximity with even false branched and true branched heterocystous cyanobacteria (Singh et al. 2013). The strain Calothrix whose three strains were incorporated in the study showed once again very true resemblance with the affinities that were obtained in the structural and the functional gene phylogenetic schemes with all the strains showing phylogenetic affinities of shifting patterns (Rasmussen and Svenning 1998; Lyra et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2013). PCA analysis placed the Calothrix strains at different levels and clusters with its affinities being evident with unbranched, false branched, and even true branched strains. The false branching genera that were studied comprised of Scytonema and Tolypothrix, and their phylogenetic affiliations were also very much like the other unbranched heterocystous cyanobacteria with all the strains showing no clear cut clustering patterns, neither in the phylogenetic trees nor the PCA clusters, that could be in coherence with the traditional scheme of cyanobacterial taxonomy (Gugger and Hoffmann 2004; Palinska et al. 1996). Finally, the only representative of its genera Anabaenopsis sp. Ind 8 also adhered to the trends that were obtained in case of the rest of heterocystous cyanobacteria under study with the strain finding positions at irregular nodes and with different partners in virtually all the trees and the PCA analyses. On shifting to the branched heterocystous clade, the genera under study were Hapalosiphon, Westiellopsis, Fischerella, Nostochopsis, and Mastigocladus. All the strains that were represented by the true branching heterocystous cyanobacteria showed ample proof of the polyphyletic origin of the order Stigonematales along with confirming to the well-postulated intermixing tendencies amongst the subsections IV and V of the heterocystous clade of cyanobacteria (Gugger and Hoffmann 2004; Mishra et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2013). In other words, it is also evident that the branched heterocystous cyanobacteria show very similar phylogenetic affinities with their unbranched heterocystous counterparts, suggesting that the entire heterocystous clade is monophyletic in origin whereas the stigonematalean heterocystous cyanobacteria are polyphyletic in origin. It was also evident from the data that for assessing proximity of small number of strains, DNA fingerprinting was definitely an efficient tool but, for larger number of strains belonging to very closely related orders, the efficiency of fingerprinting technique was markedly masked and therefore we advocate for the inclusion of DNA fingerprints in conjunction with other molecular tools for better resolution of genetic diversity, genetic proximity, and taxonomic affiliation.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, India for financial assistance in the form of project. One of us (Prashant Singh) is also thankful to the CSIR, New Delhi for providing financial assistance in the form of JRF and SRF. The Head, Department of Botany, BHU, Varanasi, India is gratefully acknowledged for providing laboratory facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Akoijam C, Singh A. Molecular typing and distribution of filamentous heterocystous cyanobacteria isolated from two distinctly located regions in North Eastern India. World J Microbiol Biotech. 2011;27:2187–2194. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0684-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chonudomkul D, Yongmanitchai W, Theeragool G, Kawachi M, Kasai F, Kaya K, Watanabe MM. Morphology, genetic diversity, temperature tolerance and toxicity of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) strains from Thailand and Japan. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;48:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikachary TV. Cyanophyta, part I and II. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, India; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ezhilarasi A, Anand N. Characterization of cyanobacteria within the genus Anabaena based on SDS-PAGE of whole cell protein and RFLP of the 16S rRNA gene. ARPN J Agric Biol Sci. 2010;5:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pichel F, Cortes AL, Nübel U. Phylogenetic and morphological diversity of cyanobacteria in soil desert crusts from the Colorado plateau. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1902–1910. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1902-1910.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugger M, Hoffmann L. Polyphyly of the true branching cyanobacteria (Stigonematales) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:349–357. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugger M, Lyra C, Henrikson P, Coute A, Humbert JF, Sihvonen K. Phylogenetic comparison of the cyanobacterial genera Anabaena and Aphanizomenon. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:1867–1880. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Morby AP, Turner JS, Whitton BA, Robinson NJ. Deletion within the metallothionein locus of cadmium-tolerant Synechococcus PCC 6301 involving a highly iterated palindrome (HIP1) Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson BJ, Watson LE, Barnum SR. Molecular differentiation of the heterocystous cyanobacteria, Nostoc and Anabaena, based on complete NifD sequences. Curr Microbiol. 2002;45:161–164. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson BJ, Hesselbrock SM, Watson LE, Barnum SR. Molecular phylogeny of the heterocystous cyanobacteria (subsections IV and V) based on nifD. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:493–497. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iteman I, Rippka R, Tandeau de Marsac N, Herdman M. rDNA analyses of planktonic heterocystous cyanobacteria, including members of the genera Anabaenopsis and Cyanospira. Microbiology. 2002;148:481–496. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Wolk CP, Kuritz T, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Iriguchi M, Ishikawa A, Kawashima K, Kimura T, Kishida Y, Kohara M, Matsumoto M, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Shimpo S, Sugimoto M, Takazawa M, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Complete genomic sequence of the filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. DNA Res. 2001;8:205–213. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.5.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komárek J, Anagnostidis K. Modern approach to the classification system of cyanophytes 4 Nostocales. Arch Hydrobiol Suppl. 1989;82:247–345. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek J, Mareš J. An update to modern taxonomy (2011) of freshwater planktic heterocystous Cyanobacteria. Hydrobiology. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Kondo R, Yoshida T, Yusi Y, Hiroishi S. DNA-DNA reassociation among a bloom-forming cyanobacterial genus, Microcystis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:767–770. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Zo YG, Kim SJ. Non-radioactive method to study genetic profiles of bacterial communities by PCR-single-strand conformation polymorphism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3112–3120. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3112-3120.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra C, Laamanen M, Lehtimäki JM, Surakka A, Sivonen K. Benthic cyanobacteria of the genus Nodularia are non toxic, without gas vacuoles, able to glide and genetically more diverse than planktonic Nodularia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:555–568. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AK, Shukla E, Singh SS. Phylogenetic comparison among the heterocystous cyanobacteria based on a polyphasic approach. Protoplasma. 2013;250:77–94. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilan BA, Saker ML, Fastner J, Törökés A, Burns BP. Phylogeography of the invasive cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:133–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Muyzer G. PCR primers to amplify 16S rDNA from Cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3327–3332. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3327-3332.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt KM, Rasmussen U, Webb EA, Waterbury JB, Gundersen K, Bergman B. Characterization of Trichodesmium spp. by genetic techniques. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2236–2245. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2236-2245.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinska KA, Liesack W, Rhiel E, Krumbein WE. Phenotype variability of identical genotype: the need for a combined approach in cyanobacterial taxonomy demonstrated on Merismopedia like isolates. Arch Microbiol. 1996;166:224–233. doi: 10.1007/s002030050378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabina BJ, Kumar K, Kannaiyan S. DNA amplification fingerprinting as a tool for checking genetic purity of strains in the cyanobacterial inoculum. World J Microbiol Biotech. 2005;21:629–634. doi: 10.1007/s11274-004-3566-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaniemi P, Hrouzek P, Kastovska K, Willame R, Rantala A, Hoffmann L, Komárek J, Sivonen K. Phylogenetic and morphological evaluation of the genera Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, Trichormus and Nostoc (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:11–26. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen U, Svenning MM. Fingerprinting of cyanobacteria based on PCR with primers derived from short and long tandemly repeated repetitive sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:265–272. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.265-272.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stainer RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. doi: 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Robinson PJ, Gupta A, Bleasby AJ, Whitton BA, Morby AP. Singular overrepresentation of an octameric palindrome, Hip1, in DNA from many cyanobacteria. Nucl Acids Res. 1995;23:729–735. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeselers G, Norris TB, Castenholz RW, Rysqaard S, Glud RN, Kuhl M, Muyzer G. Diversity of phototrophic bacteria in microbial mats from Arctic hot springs (Greenland) Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:26–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar G, Gopalaswamy G. PCR based fingerprinting of Westiellopsis cultures with short tandemly repeated repetitive (STRR) and highly iterated palindrome (HIP) sequences. Biologia. 2008;63:283–288. doi: 10.2478/s11756-008-0065-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalini DDW, Gupta RK. Phylogenetic analysis of cyanobacterial strains of genus Calothrix by single and multiplex randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR. World J Microbiol Biotech. 2008;24:927–935. doi: 10.1007/s11274-007-9569-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigler WB, Bachofen R, Zeyer J. Molecular characterization of endolithic cyanobacteria inhabiting exposed dolomite in central Switzerland. Environ Microbiol. 2003;56:18–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Singh SS, Mishra AK, Elster J. Molecular phylogeny, population genetics and evolution of heterocystous cyanobacteria using nifH gene sequences. Protoplasma. 2013;250:751–764. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JK, Parry JD, Day JG, Smith RJ. A PCR technique based on the Hip1 interspersed repetitive sequence distinguishes cyanobacterial species and strains. Microbiology. 1998;144:2791–2801. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning MM, Eriksson T, Rasmussen U. Phylogeny of symbiotic cyanobacteria within the genus Nostoc based on 16S rDNA sequence analyses. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0740-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valério E, Chambel L, Paulino S, Faria N, Pereira P, Tenreiro R. Molecular identification, typing and traceability of cyanobacteria from freshwater reservoirs. Microbiology. 2009;155:642–656. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.022848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski JR. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, Ferris MJ, Nold SC, Bateson MM. A natural view of microbial biodiversity within hot spring cyanobacterial mat communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1353–1370. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1353-1370.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willame R, Boutte C, Grubisic S, Wilmotte A, Komárek J, Hoffmann L. Morphological and molecular characterization of planktonic cyanobacteria from Belgium and Luxembourg. J Phycol. 2006;42:1312–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KM, Schembri MA, Baker PD, Saint CP. Molecular characterization of the toxic cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and design of a species-specific PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:332–338. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.1.332-338.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AE, Sarnelle O, Neilan BA, Salmon TP, Gehringer MM, Hay ME. Genetic variation of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa within and among lakes: Implications for harmful algal blooms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6126–6133. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6126-6133.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Song T, Bao X, Bergman B, Rasmussen U. High cyanobacterial diversity in coralloid roots of cycads revealed by PCR fingerprinting. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2002;40:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]