Abstract

Photoreceptor cell death is the proximal cause of blindness in many retinal degenerative disorders; hence, understanding the gene regulatory networks that promote photoreceptor survival is at the forefront of efforts to combat blindness. Down-regulation of the microRNA (miRNA)-processing enzyme DICER1 in the retinal pigmented epithelium has been implicated in geographic atrophy, an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). However, little is known about the function of DICER1 in mature rod photoreceptor cells, another retinal cell type that is severely affected in AMD. Using a conditional-knockout (cKO) mouse model, we report that loss of DICER1 in mature postmitotic rods leads to robust retinal degeneration accompanied by loss of visual function. At 14 wk of age, cKO mice exhibit a 90% reduction in photoreceptor nuclei and a 97% reduction in visual chromophore compared with those in control littermates. Before degeneration, cKO mice do not exhibit significant defects in either phototransduction or the visual cycle, suggesting that miRNAs play a primary role in rod photoreceptor survival. Using comparative small RNA sequencing analysis, we identified rod photoreceptor miRNAs of the miR-22, miR-26, miR-30, miR-92, miR-124, and let-7 families as potential factors involved in regulating the survival of rods.—Sundermeier, T. R., Zhang, N., Vinberg, F., Mustafi, D., Kohno, H., Golczak, M., Bai, X., Maeda, A., Kefalov, V. J., Palczewski, K. DICER1 is essential for survival of postmitotic rod photoreceptor cells in mice.

Keywords: microRNA, retina, conditional knockout, cell survival, age-related macular degeneration.

Recent reports suggest involvement of the microRNA (miRNA)-processing enzyme, DICER1, in the pathology of geographic atrophy (GA), an advanced form of “dry” age-related macular degeneration (AMD; refs. 1, 2). Dicer1 gene expression is reduced in the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) of patients with GA, and loss of DICER1 activity in the mouse RPE leads to retinal degeneration through disruption of a noncanonical DICER1 activity. In the retina, DICER1 expression has been shown to oscillate according to the circadian rhythm in mice, and this oscillation is phase shifted in aging animals (3). Such DICER1 dysregulation in the aging retina could contribute to age-related changes in retinal morphology and function. Rod photoreceptor cells in the retina are also intimately linked to the pathology of AMD. Loss of parafoveal rods is a normal component of retinal aging in humans, and these same central rods are the first photoreceptors lost in patients with AMD (4). However, little is known about the function of DICER1 in mature rods or its role in pathological processes in the retina.

DICER1 is a nonredundant cytoplasmic RNase III-type endoribonuclease, which is responsible for the second cleavage step in the canonical miRNA biosynthesis pathway. Roles for Dicer1 in development are well established in a wide variety of tissues including the retina. miRNA-mediated regulation of differentiation of retinal cell types has been well characterized in a variety of vertebrate experimental systems, including fly, frog, fish, and mouse (5–12). Loss of Dicer1 in the developing mouse retina leads to defects in both the timing of differentiation of neuroretinal cell types and the survival of retinal progenitors (13–17). In addition, incomplete loss of miR-124a in the developing mouse retina is sufficient to elicit apoptosis of retinal progenitors (7).

The roles of Dicer1 and miRNA gene regulation in the mature retina are less well studied. However, emerging evidence points to functions for miRNAs in coping with various forms of cellular stress (18). Because of their elevated rates of metabolism and protein synthesis, coupled with the need to cope with the toxic by-products of phototransduction, rod photoreceptors can be thought of as a perpetually stressed cell type. Therefore, miRNA gene regulation probably plays a fundamental role in promoting the survival and function of mature rods in health and disease. Consistent with this hypothesis, a cluster of miRNAs that are highly expressed in the eye and enriched in photoreceptors, the miR-183 cluster, has been shown to promote the survival of mature photoreceptors after light damage (19), and loss of these miRNAs leads to age-related retinal degeneration in mice (20). The retinal miRNA transcriptome has been characterized by both microarray and next-generation sequencing (21–28). Expression of >250 different miRNAs in the retina has been reported (21, 24). Therefore, it seems likely that miRNAs other than the miR-183 cluster play essential roles in the function and survival of rods.

To assess the physiological effect of DICER1-mediated RNA processing in rod photoreceptors, we generated mature rod photoreceptor-specific Dicer1 conditional-knockout (cKO) mice. Loss of DICER1 in rods resulted in progressive, early-onset retinal degeneration and functional impairment. Because loss of DICER1 elicits a far more severe phenotype than loss of the miR-183 cluster, additional miRNAs are likely to be important for the survival and function of rods. Using small RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we identified abundant miRNAs of the miR-22, miR-26, miR-30, miR-92, miR-124, and let-7 families expressed in rods as candidate targets to promote rod survival in the context of retinal degenerative disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Rod photoreceptor-specific Dicer1 cKO mice were generated by crossing Dicer1fl/fl mice (ref. 29; obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) with iCre75 mice (a kind gift from Neena Haider, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, USA), which express Cre recombinase specifically in rods from a fragment of the opsin gene promoter (30). Animals used for this study resulted from crossing cKO mice (Dicer1fl/fliCre75+) with control mice (Dicer1fl/fliCre75−) to yield 50% cKO mice and 50% control littermates. Cre control mice (Dicer1+/+iCre75+) were maintained by crossing with C57BL/6J wild-type mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Genotyping was done by PCR as described previously (29, 30). Mice were housed in the animal resource center at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (Cleveland, OH, USA) where they were maintained in a 12-hour light (∼10 lux)/dark cycle and fed a standard chow diet. All animal procedures were approved by the Case Western Reserve University and Washington University (St. Louis, MO, USA) animal care and use committees.

Immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and splinted ligation

For immunoblots, mouse eyes were suspended in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris; pH 8.0) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The protein concentration was normalized using the Bradford assay (31). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Immunoblots were developed using antibodies against Cre recombinase (2D8; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) or RPE65 (32). Immunostaining was performed as described previously (33), with the exception that sections were cut at 5 μm. Splinted ligation to detect mature miRNAs from cKO and control retinas was performed according to Nilsen (34). The ligation oligonucleotide sequence was 5′-CGCTTATGACATT-dideoxy-C-3′. The bridge oligonucleotide sequences were 5′-GAATGTCATAAGCGCGGTGTGAGTTCTACCATTGCCAAA-3′ (miR-182), 5′-GAATGTCATAAGCGAGTGAATTCTACCAGTGCCATA-3′ (miR-183), and 5′- GAATGTCATAAGCGAGGCAAAGGATGACAAAGGGAA-3′ (miR-211).

Ultra-high-resolution spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO)

For in vivo imaging, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 10 μl/g body weight of a mixture containing 10 mg/ml ketamine and 0.4 mg/ml xylazine in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA). Pupils of mice were dilated with a mixture of 0.5% tropicamide and 0.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride (Midorin-P; Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). In vivo retinal imaging was performed using an ultra-high-resolution SD-OCT instrument (Bioptigen, Durhan, NC, USA) in B-scan mode. SLO was performed with a Heidelberg Retinal Angiograph II instrument (Heidelberg Engineering, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Histology

Mouse eyes were fixed for 24 h by rocking in a fixation solution (2 ml/eye) containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS. The tissue was processed through a series of ethanols, xylenes, and paraffins in a Tissue-Tek VIP automatic processor (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA), and 5-μm sections were cut using a Microm HM355 paraffin microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. Stained sections were imaged on a BX60 upright microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and data analysis was performed using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For quantitation of nuclei per column, nuclei were counted manually from 3−7 mice/condition as follows: 4-wk-old control mice (n=5), 4-wk-old cKO mice (n=5), 8-wk-old control mice (n=7), 8-wk-old cKO mice (n=5), 14-wk-old control mice (n=7), 14-wk-old cKO mice (n=5), 14-wk-old age-matched iCre75 mice (n=3), 14-wk-old dark-reared control mice (n=3), and 14-wk-old dark-reared cKO mice (n=5).

Retinoid analysis

To measure the recovery of 11-cis-retinal after photobleaching, 4-wk-old mice were anesthetized, eyes were dilated as above, and mice were exposed to 10,000 lux white light for 10 min. Mice were then moved to darkness and euthanized at the appropriate time points. Eyes were enucleated and stored in the dark at −80°C. For quantification of 11-cis-retinal in the eyes of dark-adapted mice at 4, 8, and 14 wk of age, we kept animals in the dark for ≥16 h before isolating eyes. Retinoid extraction, derivitization, separation, and quantification were performed as described previously (35, 36). All steps were performed under dim red light. Retinoids were separated by normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using an Ultrasphere-Si column (4.6 μm, 250 mm; Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA, USA) by isocratic elution in 10% ethyl acetate and 90% hexane at a flow rate of 1.4 ml/min.

Electroretinogram (ERG), transretinal ERG, and single-cell recordings

Whole-animal ERG recordings were performed as described previously (33, 36). Transretinal ERG recordings also were performed as published previously (37). In brief, dark-adapted (>12 h) mice were euthanized by CO2, and eyes were enucleated under dim red light. The whole retina was dissected under infrared light, placed in a custom-build specimen holder, and perfused at a rate of 4 ml/min with Ringer's solution containing 133.9 mM Na+, 3.3 mM K+, 2.0 mM Mg2+, 1.0 mM Ca2+, 143.2 mM Cl−, 10.0 mM glucose, 0.01 mM EDTA, and 12.0 mM HEPES, buffered to pH 7.5 with NaOH. The solution was supplemented with 0.72 mg/ml Leibovitz's culture medium L-15 to improve retina viability and with 40 μM DL-AP4 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) and 100 μM BaCl2 to isolate the photoreceptor component of the ERG signal. All data were collected at 37°C, sampled at 10 kHz, and low-pass filtered at 300 Hz (8-pole Bessel filter). Test flashes were produced by homogeneous 505 nm LED light that covered the whole measurement area of the retina. Light power was measured by a calibrated optometer and converted to isomerizations (R*) per rod as described previously (38).

An exponential function (Eq. 1)

| (1) |

was fitted to the response amplitude [r(tp)] data, where rmax is the maximal response amplitude of the saturated rod photoresponse, Q is the stimulus strength in R* per rod, and Q1/2 is the best-fitting parameter describing the flash strength producing 50% of the maximal response amplitude. All analyses were done with Clampfit (Molecular Devices) and Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student's t test.

Single-cell suction recordings were done as described previously (37, 39) with retinas similar to those for the transretinal recordings. The retina was chopped into small pieces, and a single rod outer segment was drawn in the suction electrode.

RNA-seq and small RNA-seq analyses

For RNA-seq transcriptome and small RNA-seq analyses, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, eyes were enucleated, and retinas were carefully dissected out and immediately placed in RNALater stabilization reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Retinas were collected between 7:30 and 9:00 AM. For transcriptome analysis, mouse retina RNA-seq libraries were prepared as described previously (40). Pooled total RNA samples from 8 mouse retinas were used for each retina library preparation. Libraries were constructed from 3 independent biological replicates for each genotype. Each library was subjected to 50-bp single-end sequencing on one lane of an Illumina HiScan in the Case Western Reserve University Genomics Core Facility. Data were processed and aligned with the University of California, Santa Cruz, (UCSC) mouse genome assembly and transcript annotation (mm9) using the Genomic Short-read Nucleotide Alignment Program (41). Raw read counts for mouse RefSeq genes were extracted using the HTSeq-count program and used for calculations of reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values. For differential expression analysis, we identified genes with a minimum mean expression level in either control or cKO animals of 10 RPKM, a fold change either >1.25 or <0.75, and a differential expression value of P ≤ 0.05, according to an independent 2-tailed Student's t test.

For small RNA-seq, total RNA was isolated from a pool of 6 retinas/library. After removal of RNALater, QIAzol (Qiagen) was added, and the tissue was disrupted using a TissueLyser II bead mill (Qiagen). RNA was purified from the Qiazol homogenate using the Zymo Direct-zol (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) protocol with on-column DNase I digestion. Libraries were made from 1 μg of total RNA using a TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), amplified with 11 rounds of PCR, and size-selected for miRNA size inserts by gel purification. Each library was prepared to incorporate a unique index sequence, which permitted multiplexing of all 6 libraries for sequencing. Before the final gel purification step of the small RNA sample preparation protocol, a fraction of each pool of adapter ligated sequences was loaded onto a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to generate the traces shown in Supplemental Fig. S3. For quantification of the fractional abundance of 22- to 25-nt RNAs represented in this pool, the area under the peak at ∼140 nt was divided by the total area under the curve between 100 and 1000 nt. Note that the ligated adapters totaled around 120 nt. Final libraries were analyzed and quantified using the Bioanalyzer and pooled in equimolar proportions. The pooled libraries were sequenced as one 50-bp single-end run on a HiSeq 2500 instrument (Illumina) using a rapid-run flow cell. Reads were processed to remove Illumina adapter sequences and associated with samples based on the multiplex identifier. Identical reads were grouped into clusters before being mapped to mouse miRNA sequences from miRBASE (42) using the bowtie program (43). RPKM values for each miRNA in each sample were generated. Changes in miRNA expression were considered statistically significant at values of P < 0.05 based on an independent 2-tailed Student's t test. miRNAs with expression decreased by ≤0.9-fold are included in Table 2. The processed and raw fastq files for both RNA-seq transcriptome analysis and miRNA sequencing analysis were deposited at the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; Bethesda, MD, USA) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE55393).

Table 2.

Protein-coding genes with altered expression in cKO mouse retinas

| Gene | Name | Mean |

SD |

Fold change | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | cKO | Control | cKO | ||||

| Pigs | Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class S | 39.92 | 55.25 | 1.38 | 1.08 | 1.38 | 0.0002 |

| Rgs9bpa | Regulator of G protein signaling 9 binding protein | 137.50 | 252.62 | 5.48 | 10.30 | 1.84 | 0.0004 |

| Lsm14b | LSM14B, SCD6 homolog B (Streptomyces cerevisiae) | 20.39 | 30.11 | 1.44 | 1.02 | 1.48 | 0.0011 |

| Slc38a3 | Solute carrier family 38, member 3 | 260.04 | 369.16 | 11.51 | 16.39 | 1.42 | 0.0012 |

| C2cd2l | C2CD2-like | 137.46 | 184.82 | 7.08 | 7.53 | 1.34 | 0.0014 |

| Fos | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 24.87 | 15.02 | 1.32 | 1.72 | 0.60 | 0.0018 |

| Igsf9 | Immunoglobulin superfamily, member 9 | 34.39 | 46.03 | 2.65 | 2.21 | 1.34 | 0.0047 |

| Nrtn | Neurturin | 26.74 | 37.48 | 0.37 | 1.56 | 1.40 | 0.0050 |

| Tcp11 | t-complex 11, testis-specific | 14.73 | 11.01 | 0.80 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0.0051 |

| Plekhb1 | Pleckstrin homology domain containing, family B (evectins) member 1 | 311.67 | 458.53 | 20.80 | 33.15 | 1.47 | 0.0052 |

| Celf3 | CUGBP, Elav-like family member 3 | 55.16 | 69.32 | 2.63 | 3.42 | 1.26 | 0.0057 |

| Drd4 | Dopamine receptor D4 | 284.30 | 391.55 | 26.67 | 25.18 | 1.38 | 0.0072 |

| Myo7a | Myosin VIIA | 8.44 | 11.76 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.39 | 0.0072 |

| Zfpm1 | Zinc finger protein, FOG family member 1 | 10.35 | 15.52 | 0.97 | 1.43 | 1.50 | 0.0092 |

| Top1mt | Topoisomerase (DNA) I, mitochondrial | 16.46 | 11.82 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.0101 |

| Ctgf | Connective tissue growth factor | 14.63 | 9.39 | 1.22 | 1.49 | 0.64 | 0.0102 |

| Dusp1 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | 22.17 | 13.45 | 1.71 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.0107 |

| 4632415K11Rik | 4632415K11Rik | 24.57 | 35.40 | 2.96 | 2.94 | 1.44 | 0.0108 |

| Unc5a | Unc-5 homolog A (Caenorhabditis elegans) | 23.16 | 28.98 | 1.65 | 0.96 | 1.25 | 0.0111 |

| Elfn1 | Extracellular leucine-rich repeat and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 | 56.42 | 71.59 | 2.85 | 4.64 | 1.27 | 0.0134 |

| Prm1b | Protamine 1 | 0.19 | 913.74 | 0.19 | 193.64 | 4810.27 | 0.0146 |

| Nfil3 | Nuclear factor, interleukin 3 regulated | 11.40 | 8.50 | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.0153 |

| C030046I01Rik | C030046I01Rik | 63.24 | 79.47 | 5.17 | 3.05 | 1.26 | 0.0155 |

| Pgap3 | Post-GPI attachment to proteins 3 | 18.05 | 25.45 | 1.75 | 2.51 | 1.41 | 0.0174 |

| Cirbp | Cold inducible RNA binding protein | 123.29 | 156.39 | 11.18 | 9.57 | 1.27 | 0.0184 |

| Ttyh2 | Tweety family member 2 | 16.68 | 24.80 | 2.29 | 2.80 | 1.49 | 0.0190 |

| Igsf11 | Immunoglobulin superfamily, member 11 | 14.79 | 18.81 | 0.81 | 1.38 | 1.27 | 0.0194 |

| Fam110a | Family with sequence similarity 110, member A | 17.14 | 22.81 | 0.62 | 1.72 | 1.33 | 0.0197 |

| Dmpk | Dystrophia myotonica-protein kinase | 8.60 | 10.79 | 0.56 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 0.0221 |

| Ranbp6 | RAN binding protein 6 | 13.87 | 10.35 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.0227 |

| Lrrc16b | Leucine-rich repeat containing 16B | 17.48 | 22.82 | 0.69 | 1.86 | 1.31 | 0.0266 |

| Penk | Proenkephalin | 47.59 | 34.75 | 2.29 | 4.91 | 0.73 | 0.0292 |

| Hr | Hair growth associated | 20.32 | 26.30 | 2.60 | 1.76 | 1.29 | 0.0363 |

| Hspb6 | Heat shock protein, α-crystallin-related, B6 | 82.73 | 111.65 | 10.65 | 12.49 | 1.35 | 0.0392 |

| Apobec2 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 2 | 11.09 | 15.16 | 0.91 | 1.79 | 1.37 | 0.0398 |

| Sema3f | Sema domain, immunoglobulin domain (Ig), short basic domain, secreted, (semaphorin) 3F | 71.98 | 92.56 | 9.07 | 4.60 | 1.29 | 0.0400 |

| Ntng2 | Netrin G2 | 74.90 | 99.08 | 10.08 | 9.88 | 1.32 | 0.0412 |

| Prima1 | Proline-rich membrane anchor 1 | 10.13 | 12.85 | 0.25 | 1.07 | 1.27 | 0.0418 |

| Bbs12 | Bardet-Biedl syndrome 12 | 11.82 | 8.85 | 1.33 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.0419 |

| Rhbdf2 | Rhomboid 5 homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 9.03 | 11.30 | 0.89 | 0.17 | 1.25 | 0.0434 |

| Clasrp | CLK4-associating serine/arginine rich protein | 22.27 | 28.39 | 0.74 | 2.64 | 1.27 | 0.0478 |

| Rrp1b | Ribosomal RNA processing 1B | 18.84 | 24.37 | 0.49 | 2.32 | 1.29 | 0.0487 |

P values were calculated using a 2-tailed independent Student's t test.

Differential expression of Rgs9bp results from a second transgene present in the iCre75 line (37).

RESULTS

Rod-specific cKO of Dicer1 leads to progressive retinal degeneration

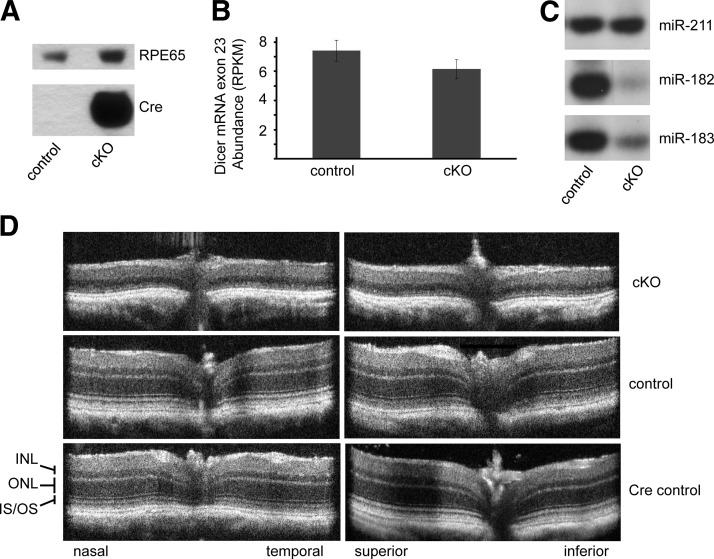

To evaluate the in vivo effect of loss of DICER1 function in mature postmitotic rod photoreceptors, we generated cKO mice by crossing Dicer1fl/fl with iCre75 mice (which express Cre recombinase from a fragment of the mouse Opsin promoter), resulting in mature rod photoreceptor-specific Dicer1 cKO mice (29, 30). By 4 wk of age, cKO mice accumulate high levels of Cre recombinase in their eyes (Fig. 1A). To confirm loss of DICER1 function in rods, we used splinted ligation to measure the abundance of the photoreceptor-enriched miRNAs, miR-182 and miR-183, and found their levels to be dramatically decreased in cKO animals compared with those in control littermates (Fig. 1C). The residual levels of miR-182 and miR-183 are probably attributable to expression in other retinal cell types, including cone photoreceptors. In contrast, the expression level of miR-211, which is found primarily in the inner nuclear layer (INL; ref. 44), was unchanged. Dicer1 mRNA exon 23 (Fig. 1B) showed a subtle expression decrease in the retinas of cKO animals, suggesting that Dicer1 expression remained high in other retinal cell types.

Figure 1.

Dicer1 cKO causes progressive retinal degeneration without regional bias. A) Immunoblot of eye tissue showing Cre expression in 4-wk-old Dicer1 cKO mice and control littermates. RPE65 was used as a loading control. B) Retina-wide RNA-seq transcriptome analysis shows the level of expression of Dicer1 mRNA exon 23 (which is flanked by LoxP sites) in cKO mice and control littermates. C) Splinted ligation reveals the abundance of mature photoreceptor-enriched miR-182 and miR-183 and INL-enriched miR-211 in retinas of Dicer1 cKO mice. D) SD-OCT images of the retinas of 14-wk-old cKO animals and controls. Control mice were Dicer1fl/fliCre75− littermates. Cre control mice were age-matched Dicer1+/+iCre75+. OS, outer segment; IS, inner segment.

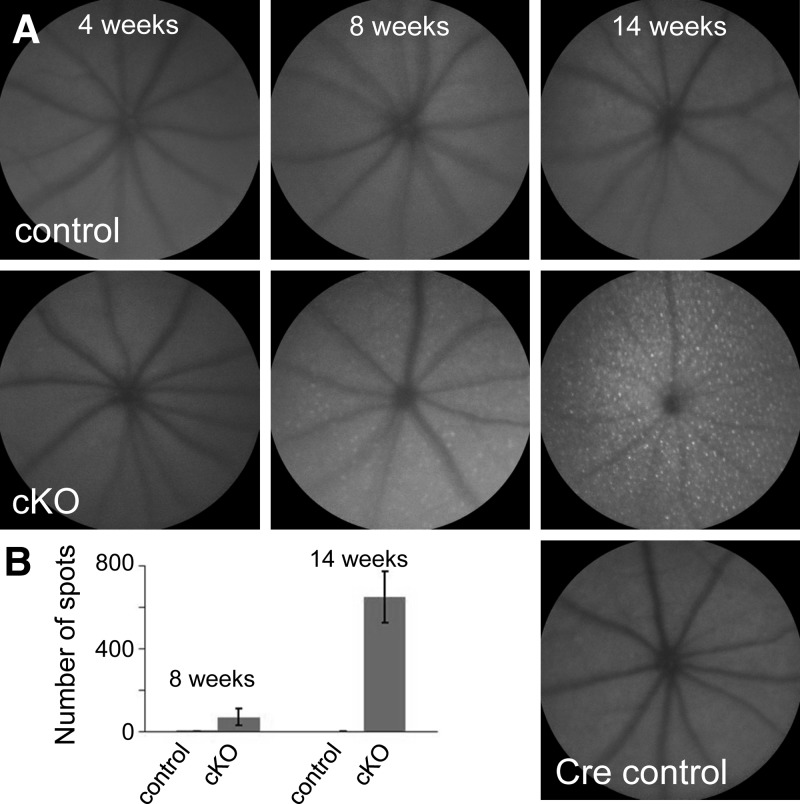

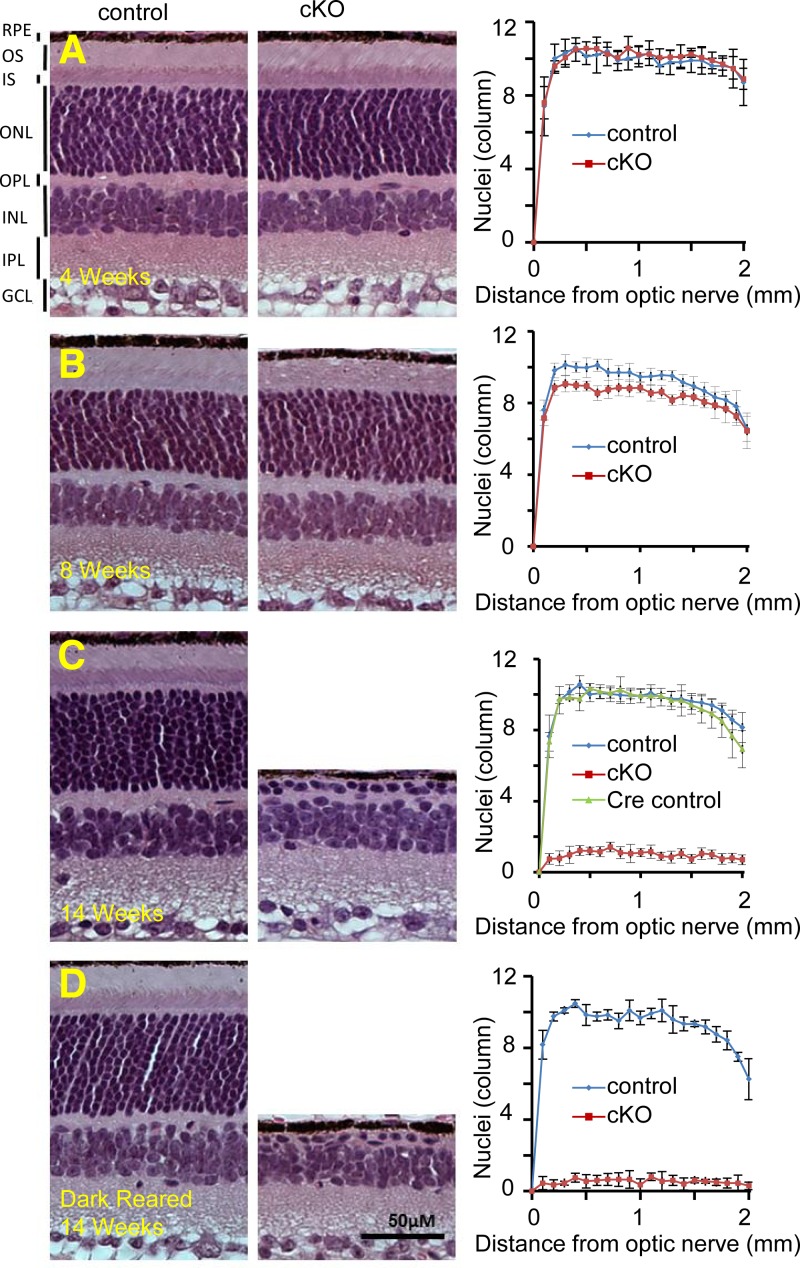

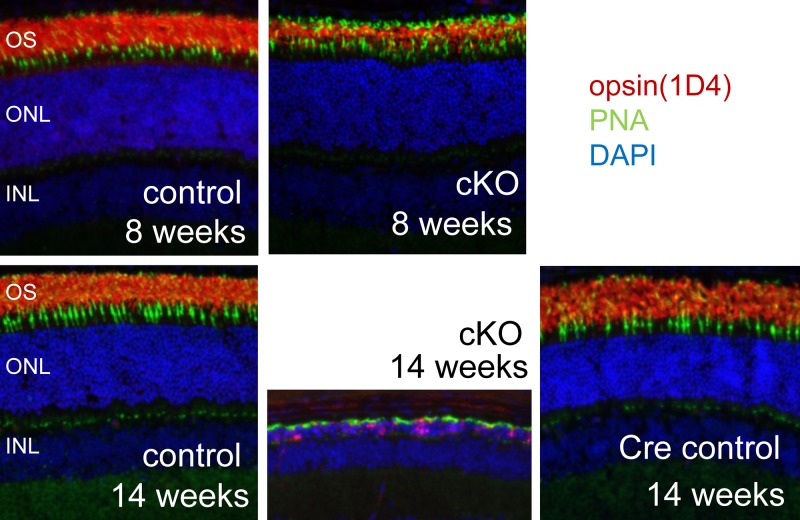

To assess the effect of loss of Dicer1 in rods, we analyzed retinal morphology in vivo in 14-wk-old animals using ultra-high resolution SD-OCT and SLO. SD-OCT revealed severe retinal degeneration without regional bias. At this age, the outer nuclear layer (ONL) was essentially absent throughout the retinas of cKO animals (Fig. 1D). This degeneration was not observed in either control littermates (Dicer1fl/fliCre75−) or age-matched Cre-expressing control animals (Dicer1+/+iCre75+). In addition, SLO revealed accumulation of autofluorescent spots in the backs of the eyes of 14-wk-old cKO animals, consistent with retinal degeneration (Fig. 2). To assess the timing of the onset of retinal degeneration, we analyzed retinal morphology at 4, 8, and 14 wk by SD-OCT (Fig. 1C), SLO (Fig. 2), H&E staining of paraffin sections (Fig. 3), and immunofluorescence (IF; Fig. 4). cKO animals were morphologically indistinguishable from control littermates at 4 wk of age (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 8-wk-old animals showed little change in the ONL, but demonstrated a dramatic loss of organization in the outer segment layer (Figs. 3B and 4), suggesting that disorganization of rod outer segments is the first observable retinal morphological defect in cKO mice. A primary effect of rod-specific Dicer1 cKO on outer segment morphology is supported by both the relative loss of opsin staining by IF (Fig. 4) and loss of outer segment 11-cis-retinal content at this age (Fig. 5A). By 14 wk of age, most of the photoreceptor layer was missing (overall ONL nuclei were reduced by 89.7%), and opsin staining was largely absent from cKO retinas, demonstrating that rod photoreceptor cell death occurs subsequent to outer segment disorganization (Figs. 1C, 3C, and 4). However, some residual cone photoreceptors persisted at this time point as noted by a few remaining ONL nuclei (Fig. 3C), residual peanut agglutinin staining (Fig. 4), and residual photopic ERG responses (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Dicer1 cKO leads to accumulation of autofluorescent spots in the back of the eye. A) SLO photographs reveal autofluorescent deposits in the retinas of cKO animals that are lacking in controls. B) Graph of number of autofluorescent spots in the retinas of cKO animals and control littermates at 8 and 14 wk of age. Error bars = sd from n = 8 eyes at 8 wk and n = 4 eyes at 14 wk. Control mice were Dicer1fl/fliCre75− littermates. Cre control mice were age-matched Dicer1+/+iCre75+.

Figure 3.

Quantification of retinal degeneration in cKO animals. A–C) H&E staining of paraffin sections from the eyes of cKO mice and controls at 4 (A), 8 (B), and 14 (C) wk of age (left panels) followed by graphs of ONL nuclei per column as a function of distance from the optic nerve (right panels). OPL, outer plexiform layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. D) H&E staining of paraffin sections of eyes from 14-wk-old cKO mice and control littermates reared in the dark. Error bars = sd from 3–7 animals. Control mice were Dicer1fl/fliCre75− littermates. Cre control mice were age-matched Dicer1+/+iCre75+.

Figure 4.

Abnormal cKO retinal morphology begins with disorganization of photoreceptor outer segments. IF images of the retinas of 8- and 14-wk-old cKO mice and controls are shown. Rod outer segments are labeled with α-opsin (1D4) antibody (red), cones are labeled with peanut agglutinin (PNA; green), and nuclei are labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). Control mice were Dicer1fl/fliCre75− littermates. Cre control mice were age-matched Dicer1+/+iCre75+.

Figure 5.

Dicer1 cKO leads to functional impairment of the visual system. A) Graph of total 11-cis-retinal content of the eyes of cKO and control animals at 4, 8, and 14 wk of age. Error bars represent the sd from n = 3–4 control animals and 5 cKO animals. B) Graph showing the recovery of 11-cis-retinal as a function of time after photobleaching in 4-wk-old cKO and control animals. Error bars represent sd from n = 3 mice. C−E) Graphs of the amplitudes of ERG scotopic b waves in cKO animals and control littermates at 4 (C), 8 (D), and 14 wk of age (E). Error bars = sd from n = 5–7 animals. Control mice were Dicer1fl/fliCre75− littermates.

Because miR-183 cluster loss-of-function mouse models have previously shown increased sensitivity to light damage, we next tested whether ambient light was required to elicit retinal degeneration in cKO mice (19, 20). To this end, we dark-reared cKO mice and control littermates and observed their retinal morphology at 14 wk of age. Dark rearing failed to rescue retinal degeneration in cKO mice (Fig. 3D). Moreover, 14-wk-old dark-reared cKO mice exhibited morphology similar to that of cKO animals kept under normal laboratory lighting conditions.

Rod-specific Dicer1 cKO does not lead to a primary defect in the visual cycle

The 2 primary functions of rod photoreceptor cells are to capture photons of light and convert them into electrical responses, which are interpreted by the remainder of the central nervous system in a process known as phototransduction (45), and to participate in the regeneration of the visual chromophore, 11-cis-retinal, via the visual (retinoid) cycle (46). Mutations of genes encoding components of either phototransduction or the visual cycle are common causes of retinal degenerative disorders in humans. Therefore, we next sought to determine whether retinal degeneration in cKO animals was due to defects in either of these 2 primary rod photoreceptor functions. To assess visual cycle function, we first measured levels of visual chromophore in the retinas of dark-adapted cKO mice at 4, 8, and 14 wk of age. Consistent with the observed changes in outer segment morphology, we found a dramatic decrease in 11-cis-retinal in the eyes of 8-wk-old cKO animals, and the visual chromophore was nearly absent by 14 wk (Fig. 5A). Visual chromophore content of 4-wk-old animals was similar to that of control littermates.

At 4 wk of age, cKO animals were indistinguishable from control littermates in terms of morphology (Figs. 3 and 4) and 11-cis-retinal levels (Fig. 5A), despite loss of DICER1 activity as evidenced by a reduction in mature photoreceptor-specific miRNAs (Fig. 1C). Therefore, we measured visual cycle efficiency in 4-wk-old animals to determine whether a defect in the visual cycle was the cause of subsequent retinal degeneration. We measured the rate of recovery of visual chromophore after photobleaching in 4-wk-old cKO animals and compared it with that of control littermates. We found no significant differences in the rate of recovery of 11-cis-retinal (Fig. 5B), and the 11-cis-retinal content (Fig. 5A) of dark-adapted 4-wk-old mice was also quite similar between cKO and control animals. Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that rod-specific Dicer1 cKO does not cause a primary defect in the visual cycle and loss of visual chromophore at 8 and 14 wk is due to outer segment disorganization and retinal degeneration.

Rod-specific Dicer1 cKO does not lead to a primary defect in phototransduction

To determine whether retinal degeneration in cKO animals is due to defects in the other primary function of rod photoreceptors, namely phototransduction, we first analyzed ERG responses. Consistent with changes in morphology, in vivo ERG recordings demonstrated clear defects in light responsiveness in 8- and 14-wk-old cKO animals (Fig. 5C−E and Supplemental Fig. S1). Rod-driven scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes were decreased modestly at 8 wk and dramatically at 14 wk of age. Defects in cone-driven photopic responses were slower to develop and less severe. Photopic b-wave amplitudes were similar to those of control animals at 8 wk of age and decreased by only ∼50% at 14 wk of age (Supplemental Fig. S1). Loss of cone photoreceptors due to primary rod dystrophy is a common feature of both mouse models and human diseases. At 4 wk of age, after loss of DICER1 activity but before changes in morphology, we observed a very subtle decline in scotopic ERG response amplitudes, suggesting the possibility of a primary defect in phototransduction (Fig. 5C).

To examine the phototransduction response in greater detail, we used transretinal ERGs to compare light responses of dark-adapted isolated retinas from 4-wk-old cKO and control mice. As we showed recently, iCre75 mice exhibit accelerated photoresponse kinetics with an undershoot observed at the late phase of response termination because of increased abundance of the RGS9 GTPase accelerating complex (37). Therefore, to specifically determine the effect of loss of DICER1 activity on photoresponses, we used age-matched Cre-expressing mice as controls for transretinal ERG and single-cell recordings. Figure 6A, B illustrates rod flash responses to test flashes of varying intensity recorded from Cre control (Dicer1+/+iCre75+) and cKO mouse retinas. The general waveform and maximal amplitude of responses were comparable in Cre-expressing controls and cKO animals (Fig. 6A, B and Table 1). Loss of DICER1 caused a subtle acceleration of response shutoff (Fig. 6C) that was evident as both a shortening of the time to peak (tp) of dim flash responses and a small, although not statistically significant, decrease in the rate-limiting time constant of the saturated rod photoresponse recovery (τD; Table 1 and ref. 47). Consistent with this mild acceleration in response termination, cKO mouse rods were slightly less sensitive than control rods (Fig. 6D and Table 1). Overall, our transretinal ERG results suggest only a very minor effect of DICER1 removal on rod transretinal responses before the onset of rod degeneration.

Figure 6.

Kinetics of phototransduction are only slightly altered in cKO mice. A, B) Dark-adapted rod photoresponses to short 1-ms flashes of 505 nm light recorded by transretinal ERGs from Cre control (A) and Dicer1 cKO (B) mouse retinas. C) Averaged dim flash responses normalized by maximum response amplitude and flash strength (R*/rod) shown for Cre control (black, n=5) and Dicer1 cKO mice (red, n=9). Error bars = sem. D) Normalized response amplitudes plotted as a function of flash strength (R*/rod) for control (black, n=5) and cKO mice (red, n=9). Smooth lines are a plot of Eq. 1 with Q1/2 = 70 and 89 R*/rod for control (black) and cKO (red) mice, respectively.

Table 1.

Mouse rod photoresponse parameters

| Parameter | Cre control | cKO |

|---|---|---|

| Transretinal ERG | ||

| rsat (μV) | 663 ± 73 | 488 ± 41 |

| tp (ms) | 112 ± 3 | 97 ± 2.4** |

| τD (ms) | 72 ± 5 | 64 ± 6 |

| SF (%/R*) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.05* |

| Q1/2 (R*) | 71 ± 8 | 89 ± 4 |

| Single-cell recordings | ||

| Idark (pA) | 12.4 ± 0.4 | 11.6 ± 0.4 |

| I1/2 (phot/μm2) | 26.1 ± 2.0 | 22.7 ± 1.3 |

| tp (ms) | 171 ± 6 | 176 ± 23 |

| τintegr (ms) | 288 ± 18 | 282 ± 17 |

| τD (ms) | 166 ± 10 | 164 ± 10 |

Rod photoresponse parameters for Cre control (Dicer+/+iCre75+) and Dicer cKO (Dicerfl/fliCre75+) mice derived from transretinal and single-cell recordings. For transretinal ERGs: rsat, saturated response amplitude measured at plateau; tp, time to peak of a dim flash response; τD, dominant time constant; SF, fractional sensitivity of a dim flash response; Q1/2, half-saturating flash strength in R* per rod. For single-cell recordings: Idark, dark current measured from saturated responses; I1/2, half-saturating light intensity; tp (time-to-peak) and τintegr (integration time) refer to responses whose amplitudes were <0.2 Idark and fell within the linear range; τD, dominant time constant of recovery after supersaturating flashes determined from the linear fit to time in saturation vs. intensity semilog plots. Data represent means ± sem.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.005 vs. control.

To determine whether the slightly altered transretinal ERG responses of cKO rods were a direct result of altered phototransduction, we next performed single-cell suction electrode recordings from rods of age-matched 4-wk-old Cre control and cKO mice. Consistent with our transretinal ERG recordings, we found that the responses of cKO rods were comparable to those of the control rods (Supplemental Fig. S2A, B). However, in contrast to the transretinal recordings, the single-cell recordings revealed no significant difference in sensitivity or response kinetics between Cre control and cKO rods (Supplemental Fig. S2C, D and Table 1). Thus, the slight change in sensitivity and kinetics observed with transretinal ERG recordings in cKO rods could not be attributed to a direct effect of DICER1 on the rod phototransduction cascade. Rather, it more likely reflects an effect on signal propagation beyond the outer segments of cKO rods.

Dicer1 cKO leads to minor expression changes in protein coding genes.

To begin to understand which genes and gene regulation networks were affected in cKO mice to lead to retinal degeneration, we performed RNA-seq transcriptome analysis, comparing the global retinal transcriptome of 4-wk-old cKO mice and control littermates. We identified 42 differentially expressed genes in cKO mice (Table 2 and Fig. 7A) including 2 genes linked to retinal degenerative disorders in human patients. Bbs12 is associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome, and Myo7a is linked to Usher syndrome. Differentially expressed genes are associated with diverse functions, including signaling, gene regulation, and synapse formation and function (Fig. 7B). miRNAs are thought to act through effecting relatively modest changes in the expression levels of many different genes. Consistent with this notion, the observed expression differences were generally mild. None of the genes were differentially expressed by >2-fold, and expression of only 4 genes was altered by ≥1.5-fold (excluding Prm1 and Rgs9bp, which are altered because of transgenic expression in iCre75 mice; refs. 30, 37). Of the 42 differentially expressed genes, 9, including 3 of the 4 genes altered by >1.5-fold (Fos, Dusp1, and Ctgf), were previously shown to exhibit temporal oscillation in the mouse eye (48). This finding is consistent with reports of diurnal oscillation in expression of the abundant photoreceptor-enriched miR-183 cluster as well as miRNA-mediated regulation of circadian rhythm in a variety of systems (26, 44, 49).

Figure 7.

cKO animals exhibit disregulation of a diverse set of genes. A) Volcano plot showing genes differentially expressed in the retinas of cKO animals. Differentially expressed genes are shown in red. B) Pie chart showing some of the functions of genes differentially expressed in the retinas of cKO animals. C) Volcano plot showing differential expression of miRNAs in control vs. cKO retinas.

Small RNA-seq identifies a limited set of rod photoreceptor-enriched miRNAs

The robust retinal degeneration that resulted from global loss of functional miRNAs in postmitotic rod-specific Dicer1 cKO mice was considerably more severe than the enhanced sensitivity to light damage or age-related retinal degeneration observed previously in miR-183 cluster loss-of-function models (19, 20). This observation suggests that miRNAs other than miRs-96, miR-182, and miR-183 play important roles in the survival and function of mature rod photoreceptors. Therefore, we next sought to identify other miRNAs expressed in postmitotic rods. Because 4-wk-old cKO mice were morphologically and functionally similar to controls despite loss of mature rod miRNAs, they provided a powerful genetic tool for identifying miRNAs enriched in rods. We generated libraries of small RNAs derived from the retinas of 4-wk-old cKO or control mice and subjected them to small RNA-seq analysis. The relative abundance of different small RNA species in the pool of adapter ligated RNAs used to generate small RNA-seq libraries was assessed using a bioanalyzer. We found that the abundance of species corresponding to miRNAs (22- to 25-nt plus adapters), relative to other small RNAs including 5S rRNA and tRNAs, was significantly lower (∼50%) in libraries derived from cKO retinas (Supplemental Fig. S3). This result suggested that in control mice, nearly half of the retinal miRNAs are located in rods. Based on this result, we predicted that retinal miRNAs not present in rods or enriched in other retinal cell types would show increased expression in cKO-derived small RNA-seq libraries. Similarly, miRNAs exhibiting similar expression in cKO and control retinas should be expressed in rods at levels similar to those in the rest of the retina. Finally, miRNAs with decreased expression in cKO animals were considered to be enriched in rods. Using an expression cutoff of 500 RPKM in control libraries, we identified 183 miRNAs abundantly expressed in the mouse retina. The vast majority of retinal miRNAs (162 of 183) were increased in cKO libraries, suggesting that most retinal miRNAs are enriched in other retinal cell types (Fig. 7C). This list includes the highly expressed miR-204 and miR-211 (increased by 1.94- and 1.95-fold, respectively), which were previously shown to localize to the INL (44). Among miRNAs with similar expression levels in cKO and control retinas, we identified the ubiquitously expressed let-7 family miRNAs (let-7a-1, let-7a-2, let-7c-1, let-7c-2, let-7e, let7f-1, let7f-2, and let7g, all increased between 1.25- and 1.39-fold) and the neuron-specific miR-124 family (miR-124-1, miR-124-2, and miR-124-3, all decreased 0.94-fold). Consistent with previous results, miR-183 cluster expression decreased in cKO retinas and is therefore enriched in rods (miR-96, miR-182, and miR-183 were decreased 0.71-, 0.89-, and 0.55 fold, respectively; refs. 20, 26, 44). More interestingly, we found a limited number of additional miRNAs enriched in rods, including miR-92a-1, miR-92a-2, miR-335, miR-423, miR-425, and miR-872 (Table 3). Consistent with their well-characterized role in rod survival, miR-183 cluster miRNAs were among the most highly expressed miRNAs in the mouse retina, with miR-182, in particular, accounting for 37% of mapped reads. Table 4 shows the 12 most highly expressed miRNA families in the mouse retina. Among them, the miR-183 cluster, the miR-124 family, and the miR-92 family were decreased in cKO retinas, whereas the miR-30, let-7, miR-22, and miR-26 families were increased by <1.5 fold, suggesting that they are also highly expressed in rods. These miRNAs are promising candidates as novel factors regulating the survival of rod photoreceptors.

Table 3.

miRNAs with decreased expression in cKO retinas

| miRNA | Control RPKM |

cKO RPKM |

Fold change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| mmu-mir-5097 | 1355 | 1493 | 404 | 197 | 0.298 |

| mmu-mir-182a | 7,295,946 | 254,352 | 4,024,508 | 350,964 | 0.552 |

| mmu-mir-92a-2 | 32,101 | 8677 | 21,543 | 2142 | 0.671 |

| mmu-mir-96 | 11,920 | 2241 | 8443 | 1441 | 0.708 |

| mmu-mir-872a | 5710 | 516 | 4288 | 72 | 0.751 |

| mmu-mir-92a-1 | 57,965 | 11,642 | 44,616 | 2771 | 0.770 |

| mmu-mir-423 | 4047 | 525 | 3133 | 421 | 0.774 |

| mmu-mir-335 | 4605 | 475 | 3600 | 176 | 0.782 |

| mmu-mir-425 | 2510 | 585 | 2111 | 99 | 0.841 |

| mmu-mir-183 | 376,668 | 104,008 | 336,067 | 41,694 | 0.892 |

miR-182 and miR-872 were statistically significantly different between control and cKO retinas.

Table 4.

Altered expression of the most abundant retinal miRNA families

| miRNA family | Control RPKM |

cKO RPKM |

Fraction | Fold change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| miR-183 clustera,b | 7,684,534 | 246,592 | 4,369,017 | 335,262 | 0.3946 | 0.5685 |

| miR-181a | 5,771,324 | 75,700 | 9,460,621 | 128,016 | 0.2964 | 1.6392 |

| miR-30a | 1,312,846 | 9177 | 1,627,361 | 16,228 | 0.0674 | 1.2396 |

| let-7a | 1,181,821 | 8895 | 1,603,482 | 12,524 | 0.0607 | 1.3923 |

| miR-26a | 910,374 | 27,658 | 1,305,147 | 36,300 | 0.0467 | 1.4336 |

| miR-204a | 433,033 | 26,055 | 841,871 | 75,386 | 0.0222 | 1.9441 |

| miR-211a | 268,604 | 16,699 | 524,074 | 45,624 | 0.0138 | 1.9511 |

| miR-124 | 258,734 | 13,538 | 243,921 | 6119 | 0.0133 | 0.9427 |

| miR-9a | 164,086 | 7025 | 268,506 | 3376 | 0.0084 | 1.6364 |

| miR-127a | 159,255 | 26,301 | 390,810 | 14,513 | 0.0082 | 2.4540 |

| miR-22 | 103,975 | 15,437 | 147,321 | 14,682 | 0.0053 | 1.4169 |

| miR-92a | 104,263 | 9277 | 89,884 | 2521 | 0.0054 | 0.8621 |

miR-9-1, miR-9-2, miR-9-3, miR-26a-1, miR-26a-2, miR-26b, miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30d, miR-30e, miR-30f, miR-92b, miR-127, miR-181a-1, miR-181a-2, miR-181b-1, miR-181b-2, miR-181c, miR-181d, miR-204, miR-211, let-7b, let-7d, let-7i, and let-7j were statistically significantly different between control and cKO retinas.

miR-183 cluster includes miR-96, miR-182, and miR-183.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here clearly demonstrate that DICER1 is essential for the survival of mature postmitotic rod photoreceptors. This observation suggests that miRNA and/or DICER1 function in rods could play a role in the pathology of retinal degenerative disorders such as AMD and motivates the search for additional rod photoreceptor miRNAs that affect the survival and function of this important retinal cell type. Rod-specific Dicer1 cKO mice undergo early-onset retinal degeneration beginning with outer segment disorganization and accompanied by loss of visual function. Before degeneration, these mice exhibit no significant abnormalities in either phototransduction or the visual cycle, suggesting that DICER1 loss leads to a primary defect in rod survival. cKO mice did display a slight alteration in photoresponse amplitude and kinetics as observed by transretinal ERG. However, these changes were not apparent in suction electrode recordings from rod outer segments, suggesting that they are independent of phototransduction. Synaptic transmission was probably absent under our transretinal ERG recording conditions. However, one possible explanation for the differences between transretinal ERG and single-cell recordings is that altered ionic currents within the rod inner segment or at the synapse could modify ERG signals (50, 51). It was previously reported that loss of miR-183 cluster activity leads to abnormal synaptic transmission at photoreceptor ribbon synapses (20), and expression of several genes involved in synaptogenesis and synaptic function is altered in cKO animals. Because the rod-enriched miR-183 cluster is the most highly expressed miRNA family in the retina, loss of these miRNAs in cKO mice could potentially modify ionic mechanisms at rod presynaptic termini, leading to changes in transretinal ERG a waves.

We identified a limited set of protein-coding genes that are differentially expressed in cKO mice, including 2 genes, Bbs12 and Myo7a, linked to retinal degenerative disorders in humans. Although the differential expression profile offers promising clues to defects in gene regulation that lead to retinal degeneration, none of the genes were differentially expressed by >2-fold and expression levels of only 4 genes were altered by ≥1.5-fold [excluding Prm1 and Rgs9bp, which were altered because of transgenic expression in iCre75 mice (30, 37)]. Given the significant loss of rod photoreceptor miRNAs, along with the severity of the morphological and functional defects observed in cKO mice, we expected to observe more dramatic differences in gene expression. There are at least 3 plausible explanations for the modest changes observed. First, miRNAs are thought to fine-tune gene expression by eliciting mild repression of expression of groups of genes. The observed small gene expression changes are consistent with this model and could act synergistically to elicit more dramatic cellular consequences. For instance, subtle changes in the expression of multiple genes involved in the same pathway (Fig. 7C) could combine functionally to result in rod photoreceptor cell death. Second, more robust changes in expression of certain genes in rods could be masked by their higher expression in other retinal cell types. This possibility seems unlikely, though, because rods represent >90% of the cells in the mouse retina, and, therefore, must contribute a substantial fraction of its mRNA (52). Finally, miRNAs have been reported to regulate their targets through either mRNA destabilization or translational repression. Because miRNA-mediated translational regulation of direct targets would not be observed by transcriptome analysis, some genes may exhibit much more dramatic dysregulation at the protein level in cKO mice, driving retinal degeneration. Indeed, analysis of predicted miRNA target sites in the 3′-untranslated region of genes that were up-regulated in cKO animals (using TargetScan) did not reveal significant enrichment in target sites for the miRNA families present in rods (53). This result suggests that either rod miRNAs regulate their targets at the level of translation or that rods exhibit abundant noncanonical miRNA target sites lacking perfect seed region complementarity. Systematic analysis of miRNA-target mRNA interactions in the retina will be required to evaluate these possibilities.

Previous reports suggested that, in the RPE, the toxicity associated with DICER1 loss occurs primarily because of defects in noncanonical DICER1 activity, namely cleavage of toxic transcripts of Alu elements (1, 2). It is possible that DICER1 cleavage of RNA molecules other than pre-miRNAs is important for rod survival as well. However, because miRNAs are known to be involved in the survival of rods, it is likely that the phenotype of cKO mice is mediated through loss of mature miRNAs (19, 20). Previous work on the function of miRNAs in postmitotic rods has focused mainly on the miR-183 cluster. Loss of miR-183 cluster activity in mice, caused by either a miRNA sponge transgene expressed specifically in mature rods or a largely inactivating mutation within the cluster, leads to enhanced sensitivity to both light- and age-induced retinal degeneration (19, 20). The early-onset retinal degeneration under normal laboratory lighting conditions that we observed in cKO mice represents a dramatically more severe phenotype. Therefore, it is likely that additional miRNAs are important for the survival and function of rods.

To identify other miRNAs expressed in rods that could be functionally important, we used small RNA-seq to compare the miRNA content of the retinas of cKO mice and control littermates. We were able to identify an age when loss of DICER1 activity and degradation of residual rod miRNAs was complete, but morphological or functional defects had yet to emerge. This allowed identification of changes in retinal miRNA expression patterns that were specific to loss of miRNAs in rods and not due to changes in retinal cell health or physiology. This precise genetic approach identified a list of miRNAs that were either enriched in rods (similar to the miR-183 cluster) or expressed in rods as well as other retinal cell types. In addition to the photoreceptor-enriched miR-183 cluster, this list featured some of the most highly expressed miRNA families in the retina, including the miR-22, miR-26, miR-30, miR-92, miR-124, and let-7 families. These miRNAs are promising candidates as novel factors regulating the survival of rod photoreceptors. Although beyond the scope of this report, assessment of the effect of these miRNAs in rods promises to provide important insight into the gene regulatory networks that govern rod survival.

Both the accessibility and relative isolation of the retinal compartment make visual system pathological conditions attractive candidates for gene therapy approaches. In addition, miRNA-based therapy promises enhanced efficacy by targeting multiple genes in the same pathway. Therefore, manipulating miRNA pathways to promote the survival of retinal cell types is a potentially powerful novel strategy to ameliorate the pathology of retinal degenerative disorders. However, exploring this therapeutic avenue will require a more detailed understanding of the functional significance of retinal miRNAs. The results reported here represent an essential step in this process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neena Haider (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Dr. Jason Chen (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA) for providing mice, Catherine Doller and Scott Howell of the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Visual Science Research Center Histology and Digital Imaging Cores for assistance with histological analysis, and Dr. Leslie T. Webster, Jr. (CWRU) for comments on the article.

This work was supported by funding from the National Eye Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants R01EY0022326 to K.P., R24EY021126 to K.P. and V.J.K., R01EY019312 to V.J.K., EY002687 to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Washington University, and P30EY11373), Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Foundation Fighting Blindness. K.P. is the John H. Hord Professor of Pharmacology.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AMD

- age-related macular degeneration

- cKO

- conditional knockout

- ERG

- electroretinogram

- GA

- geographic atrophy

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- IF

- immunofluorescence

- INL

- inner nuclear layer

- miRNA

- microRNA

- ONL

- outer nuclear layer

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- RNA-seq

- RNA sequencing

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- RPKM

- reads per kilobase per million mapped reads

- SD-OCT

- spectral domain optical coherence tomography

- SLO

- scanning laser ophthalmoscopy

REFERENCES

- 1. Tarallo V., Hirano Y., Gelfand B. D., Dridi S., Kerur N., Kim Y., Cho W. G., Kaneko H., Fowler B. J., Bogdanovich S., Albuquerque R. J., Hauswirth W. W., Chiodo V. A., Kugel J. F., Goodrich J. A., Ponicsan S. L., Chaudhuri G., Murphy M. P., Dunaief J. L., Ambati B. K., Ogura Y., Yoo J. W., Lee D. K., Provost P., Hinton D. R., Nunez G., Baffi J. Z., Kleinman M. E., Ambati J. (2012) DICER1 loss and Alu RNA induce age-related macular degeneration via the NLRP3 inflammasome and MyD88. Cell 149, 847–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaneko H., Dridi S., Tarallo V., Gelfand B. D., Fowler B. J., Cho W. G., Kleinman M. E., Ponicsan S. L., Hauswirth W. W., Chiodo V. A., Kariko K., Yoo J. W., Lee D. K., Hadziahmetovic M., Song Y., Misra S., Chaudhuri G., Buaas F. W., Braun R. E., Hinton D. R., Zhang Q., Grossniklaus H. E., Provis J. M., Madigan M. C., Milam A. H., Justice N. L., Albuquerque R. J., Blandford A. D., Bogdanovich S., Hirano Y., Witta J., Fuchs E., Littman D. R., Ambati B. K., Rudin C. M., Chong M. M., Provost P., Kugel J. F., Goodrich J. A., Dunaief J. L., Baffi J. Z., Ambati J. (2011) DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature 471, 325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yan Y., Salazar T. E., Dominguez J. M., 2nd, Nguyen D. V., Li Calzi S., Bhatwadekar A. D., Qi X., Busik J. V., Boulton M. E., Grant M. B. (2013) Dicer expression exhibits a tissue-specific diurnal pattern that is lost during aging and in diabetes. PLoS One 8, e80029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curcio C. A. (2001) Photoreceptor topography in ageing and age-related maculopathy. Eye 15, 376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sundermeier T. R., Palczewski K. (2012) The physiological impact of microRNA gene regulation in the retina. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 2739–2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baudet M. L., Zivraj K. H., Abreu-Goodger C., Muldal A., Armisen J., Blenkiron C., Goldstein L. D., Miska E. A., Holt C. E. (2012) miR-124 acts through CoREST to control onset of Sema3A sensitivity in navigating retinal growth cones. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanuki R., Onishi A., Koike C., Muramatsu R., Watanabe S., Muranishi Y., Irie S., Uneo S., Koyasu T., Matsui R., Cherasse Y., Urade Y., Watanabe D., Kondo M., Yamashita T., Furukawa T. (2011) miR-124a is required for hippocampal axogenesis and retinal cone survival through Lhx2 suppression. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1125–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conte I., Carrella S., Avellino R., Karali M., Marco-Ferreres R., Bovolenta P., Banfi S. (2010) miR-204 is required for lens and retinal development via Meis2 targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15491–15496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilgers V., Bushati N., Cohen S. M. (2010) Drosophila microRNAs 263a/b confer robustness during development by protecting nascent sense organs from apoptosis. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Decembrini S., Bressan D., Vignali R., Pitto L., Mariotti S., Rainaldi G., Wang X., Evangelista M., Barsacchi G., Cremisi F. (2009) MicroRNAs couple cell fate and developmental timing in retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21179–21184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X., Cassidy J. J., Reinke C. A., Fischboeck S., Carthew R. W. (2009) A microRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell 137, 273–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li X., Carthew R. W. (2005) A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell 123, 1267–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Damiani D., Alexander J. J., O'Rourke J. R., McManus M., Jadhav A. P., Cepko C. L., Hauswirth W. W., Harfe B. D., Strettoi E. (2008) Dicer inactivation leads to progressive functional and structural degeneration of the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 28, 4878–4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Georgi S. A., Reh T. A. (2011) Dicer is required for the maintenance of notch signaling and gliogenic competence during mouse retinal development. Dev. Neurobiol. 71, 1153–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Georgi S. A., Reh T. A. (2010) Dicer is required for the transition from early to late progenitor state in the developing mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 30, 4048–4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinter R., Hindges R. (2010) Perturbations of microRNA function in mouse dicer mutants produce retinal defects and lead to aberrant axon pathfinding at the optic chiasm. PLoS One 5, e10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iida A., Shinoe T., Baba Y., Mano H., Watanabe S. (2011) Dicer plays essential roles for retinal development by regulation of survival and differentiation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 3008–3017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mendell J. T., Olson E. N. (2012) MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell 148, 1172–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu Q., Sun W., Okano K., Chen Y., Zhang N., Maeda T., Palczewski K. (2011) Sponge transgenic mouse model reveals important roles for the microRNA-183 (miR-183)/96/182 cluster in postmitotic photoreceptors of the retina. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31749–31760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lumayag S., Haldin C. E., Corbett N. J., Wahlin K. J., Cowan C., Turturro S., Larsen P. E., Kovacs B., Witmer P. D., Valle D., Zack D. J., Nicholson D. A., Xu S. (2013) Inactivation of the microRNA-183/96/182 cluster results in syndromic retinal degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E507–E516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karali M., Peluso I., Gennarino V. A., Bilio M., Verde R., Lago G., Dolle P., Banfi S. miRNeye: a microRNA expression atlas of the mouse eye. BMC Genomics 11, 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hackler L., Jr., Wan J., Swaroop A., Qian J., Zack D. J. MicroRNA profile of the developing mouse retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 1823–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karali M., Peluso I., Marigo V., Banfi S. (2007) Identification and characterization of microRNAs expressed in the mouse eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krol J., Busskamp V., Markiewicz I., Stadler M. B., Ribi S., Richter J., Duebel J., Bicker S., Fehling H. J., Schubeler D., Oertner T. G., Schratt G., Bibel M., Roska B., Filipowicz W. Characterizing light-regulated retinal microRNAs reveals rapid turnover as a common property of neuronal microRNAs. Cell 141, 618–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Makarev E., Spence J. R., Del Rio-Tsonis K., Tsonis P. A. (2006) Identification of microRNAs and other small RNAs from the adult newt eye. Mol. Vis. 12, 1386–1391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu S., Witmer P. D., Lumayag S., Kovacs B., Valle D. (2007) MicroRNA (miRNA) transcriptome of mouse retina and identification of a sensory organ-specific miRNA cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25053–25066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang F. E., Zhang C., Maminishkis A., Dong L., Zhi C., Li R., Zhao J., Majerciak V., Gaur A. B., Chen S., Miller S. S. (2010) MicroRNA-204/211 alters epithelial physiology. FASEB J. 24, 1552–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ryan D. G., Oliveira-Fernandes M., Lavker R. M. (2006) MicroRNAs of the mammalian eye display distinct and overlapping tissue specificity. Mol. Vis. 12, 1175–1184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harfe B. D., McManus M. T., Mansfield J. H., Hornstein E., Tabin C. J. (2005) The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10898–10903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li S., Chen D., Sauve Y., McCandless J., Chen Y. J., Chen C. K. (2005) Rhodopsin-iCre transgenic mouse line for Cre-mediated rod-specific gene targeting. Genesis 41, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Golczak M., Kiser P. D., Lodowski D. T., Maeda A., Palczewski K. (2010) Importance of membrane structural integrity for RPE65 retinoid isomerization activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9667–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang N., Kolesnikov A. V., Jastrzebska B., Mustafi D., Sawada O., Maeda T., Genoud C., Engel A., Kefalov V. J., Palczewski K. (2013) Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa E150K opsin mice exhibit photoreceptor disorganization. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 121–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nilsen T. W. (2013) Splinted ligation method to detect small RNAs. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maeda A., Maeda T., Imanishi Y., Kuksa V., Alekseev A., Bronson J. D., Zhang H., Zhu L., Sun W., Saperstein D. A., Rieke F., Baehr W., Palczewski K. (2005) Role of photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase in the retinoid cycle in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18822–18832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen Y., Okano K., Maeda T., Chauhan V., Golczak M., Maeda A., Palczewski K. (2012) Mechanism of all-trans-retinal toxicity with implications for Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 5059–5069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sundermeier T. R., Vinberg F., Mustafi D., Bail X., Kefalov V. J., Palczewski K. (2014) R9AP overexpression alters phototransduction kinetics in iCre75 mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 1339–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heikkinen H., Nymark S., Koskelainen A. (2008) Mouse cone photoresponses obtained with electroretinogram from the isolated retina. Vision Res. 48, 264–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shi G., Yau K. W., Chen J., Kefalov V. J. (2007) Signaling properties of a short-wave cone visual pigment and its role in phototransduction. J. Neurosci. 27, 10084–10093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mustafi D., Kevany B. M., Genoud C., Okano K., Cideciyan A. V., Sumaroka A., Roman A. J., Jacobson S. G., Engel A., Adams M. D., Palczewski K. (2011) Defective photoreceptor phagocytosis in a mouse model of enhanced S-cone syndrome causes progressive retinal degeneration. FASEB J. 25, 3157–3176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu T. D., Nacu S. (2010) Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 26, 873–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S. (2011) miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D152–D157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kent W. J. (2002) BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krol J., Busskamp V., Markiewicz I., Stadler M. B., Ribi S., Richter J., Duebel J., Bicker S., Fehling H. J., Schubeler D., Oertner T. G., Schratt G., Bibel M., Roska B., Filipowicz W. (2010) Characterizing light-regulated retinal microRNAs reveals rapid turnover as a common property of neuronal microRNAs. Cell 141, 618–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Palczewski K. (2006) G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 743–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kiser P. D., Golczak M., Palczewski K. (2014) Chemistry of the retinoid (visual) cycle. Chem. Rev. 114, 194–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pepperberg D. R., Cornwall M. C., Kahlert M., Hofmann K. P., Jin J., Jones G. J., Ripps H. (1992) Light-dependent delay in the falling phase of the retinal rod photoresponse. Vis. Neurosci. 8, 9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mustafi D., Kevany B. M., Genoud C., Bai X., Palczewski K. (2013) Photoreceptor phagocytosis is mediated by phosphoinositide signaling. FASEB J. 27, 4585–4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lim C., Allada R. (2013) Emerging roles for post-transcriptional regulation in circadian clocks. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1544–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arden G. B. (1976) Voltage gradients across the receptor layer of the isolated rat retina. J. Physiol. 256, 333–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vinberg F. J., Strandman S., Koskelainen A. (2009) Origin of the fast negative ERG component from isolated aspartate-treated mouse retina. J. Vis. 9, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jeon C. J., Strettoi E., Masland R. H. (1998) The major cell populations of the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 18, 8936–8946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2005) Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.