Abstract

A hallmark feature of Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is generation of autonomous (Ca2+-independent) activity by T286 autophosphorylation. Biochemical studies have shown that “autonomous” CaMKII is ∼5-fold further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM, but demonstration of a physiological function for such regulation within cells has remained elusive. In this study, CaMKII-induced enhancement of synaptic strength in rat hippocampal neurons required both autonomous activity and further stimulation. Synaptic strength was decreased by CaMKIIα knockdown and rescued by reexpression, but not by mutants impaired for autonomy (T286A) or binding to NMDA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2B (GluN2B; formerly NR2B; I205K). Full rescue was seen with constitutively autonomous mutants (T286D), but only if they could be further stimulated (additional T305/306A mutation), and not with two other mutations that additionally impair Ca2+/CaM binding. Compared to rescue with wild-type CaMKII, the CaM-binding-impaired mutants even had reduced synaptic strength. One of these mutants (T305/306D) mimicked an inhibitory autophosphorylation of CaMKII, whereas the other one (Δstim) abolished CaM binding without introducing charged residues. Inhibitory T305/306 autophosphorylation also reduced GluN2B binding, but this effect was independent of reduced Ca2+/CaM binding and was not mimicked by T305/306D mutation. Thus, even autonomous CaMKII activity must be further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM for enhancement of synaptic strength.—Barcomb, K., Buard, I., Coultrap, S. J., Kulbe, J. R., O'Leary, H., Benke, T. A., Bayer, K. U. Autonomous CaMKII requires further stimulation by Ca2+/calmodulin for enhancing synaptic strength.

Keywords: hippocampus, neuron, signal transduction

Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is an important mediator of neuronal plasticity, and generation of autonomous activity by T286 autophosphorylation is a hallmark feature of its regulation (reviewed in ref. 1). Indeed, this form of CaMKII autonomy is necessary for both long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) of synaptic strength (2, 3), two opposing forms of synaptic plasticity. Notably, “autonomous” CaMKII is not fully active, but is instead significantly further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM (∼5-fold), a mechanism proposed to prevent complete uncoupling from subsequent Ca2+ signals (reviewed in ref. 1). Although such further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII activity was first described >25 yr ago (4–6), the physiological functions of this regulation has remained elusive. Lack of functional evidence may be partially due to the inherent difficulties of the corresponding experiments. In addition, in common perception, autonomous and fully stimulated CaMKII activity is often viewed as essentially equal, in that several reports have indicated nearly full activation of autonomous CaMKII (up to 80%), with only minimal further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM (reviewed in ref. 7). However, recent results have demonstrated that this apparent conflict regarding further Ca2+/CaM stimulation of autonomous CaMKII is due to substrate-specific effects (8). Significant further stimulation was found to be the default for “traditional” substrates, whereas a higher level of autonomous activity was found only for T-site-binding substrates (8) and for another, LTD-related substrate class (3). Notably, based on biochemical experiments, it was recently proposed that the presence or absence of further Ca2+/CaM stimuli leads to differential substrate-class selection by autonomous CaMKII, which in turn promotes either LTP or LTD (3). In the current study, we addressed a potential physiological function of “stimulated autonomy” of CaMKII by comparing the effect of several specific regulation-impaired CaMKIIα mutants on miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) amplitudes. These mEPSCs are a postsynaptic response to nonstimulated presynaptic release of individual synaptic vesicles, and their amplitude provides a readout of synaptic strength in cultured hippocampal neurons. The mEPSCs are measured in the presence of pharmacological blockade of action potentials, as dissociated hippocampal cultures show high basal neuronal activity and action-potential firing, which also provides CaMKII stimulation by Ca2+/CaM before these experimental measurements. As CaMKII forms 12meric holoenzymes (reviewed in ref. 1), some of the specific CaMKII mutants may additionally exert a dominant negative effect on endogenous wild-type CaMKIIα. To prevent this potentially confounding effect and to allow a direct comparison between all mutants, a knockdown/reexpression approach that minimized potential crosstalk with endogenous kinase was introduced. The results demonstrate that enhancing synaptic strength by CaMKII requires not only autonomous activity but also its further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM, even when constitutive autonomous activity is allowed for extended periods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

mGFP-CaMKIIα expression vectors are described elsewhere (9, 10). The new Δstim mutation abolishes Ca2+/CaM binding by LIL299/303/304Q triple mutation, introduced in this study into the T286D/T305/306A mutant. Our shRNA (pSilencer2.1-U6-puro vector; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) targets the CaMKIIα 5′-untranslated region (UTR) sequence GCTGGTTCTCCATTTGCAC. CaMKIIα (purified after baculovirus/Sf9 expression), GFP-CaMKIIα and its mutants [in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell extracts], CaM, and GST-NMDA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2B (GluN2B; formerly GluNR2B) C terminus (purified after bacterial expression) were prepared and quantified according to published methods (11–13).

Culture and transfection of hippocampal neurons

Medium-density, dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared from newborn rat pups (14) and maintained on 15 mm coverslips at 37°C with 5% CO2 in neurobasal A medium supplemented with B27 and l-glutamine (Life Technologies). Nonneuronal cell division was prevented with FdU); 50% of the medium was exchanged at 6 d in vitro (DIV). Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) transfection was performed at 10–12 DIV, using a 3:1 ratio of shRNA to CaMKII vectors.

Immunocytochemistry and imaging

Images were collected by fluorescence microscopy in z stacks (0.2 μm steps) and analyzed with SlideBook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO, USA) (13, 14). Briefly, neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/sucrose, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, stained with anti-CaMKIIα antibody (1:1000; CBα2) or anti-shank antibody (1:500; Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO, USA) and Texas Red-labeled secondary antibody (1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), and embedded in ProLong antifade reagent (Life Technologies). Knockdown efficiency was determined by CaMKIIα immunofluorescence intensity in the soma (on a single, deconvolved optical plane). Synaptic localization of GFP-CaMKII and its mutants was determined 48 h after knockdown/reexpression, by the ratio of GFP-CaMKII fluorescence intensity at synapses (as determined by shank protein colocalization) relative to dendrites (on z-stack projection images). This ratio of synaptic localization was independent of total GFP-CaMKII expression levels (as determined by lack of any correlation between the localization ratio and the expression level).

mEPSC recording and analysis

mEPSCs were recorded at 12–13 DIV (2 d after transfection) from neurons with pyramidal morphology (15, 16). Transfected neurons were identified by GFP fluorescence, and neurons with medium-level GFP intensity were chosen. Whole-cell, voltage-clamp recordings were obtained with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at room temperature. The external solution contained (in mM): NaCl, 135–150 (adjusted to the osmolarity of the culture medium); KCl, 3; HEPES, 10; d-glucose, 10; MgSO4, 1; CaCl2, 2; and picrotoxin, 0.1 (pH 7.35, adjusted with NaOH). The internal pipette solution contained (in mM): CsMeSO4, 135; KCl, 10; HEPES, 10; MgCl2, 4; EGTA, 10; Na2-ATP, 4; Na3-GTP, 0.3; and QX-314, 5 (Tocris Cookson, Inc., Ellisville, MO, USA) (pH 7.25 adjusted with CsOH). Recordings with resting potentials above −50 mV were excluded. Neurons were held in voltage clamp at −70 mV in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 μM). mEPSCs were detected and measured with the MiniAnalysis Program (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA), and confirmed manually. Detection criteria for AMPAR-mediated mEPSCs included amplitudes >5 pA and rise times from 20 to 80% of <3 ms. Multiple events that overlapped and events with poor baselines were excluded. The mean amplitudes were calculated based on the medians of all events per individual neuron. The cumulative distribution plots include all events in all neurons for each condition.

CaM overlay and Western analysis

Preparation of protein extracts from brain or transfected HEK293 cells, in vitro CaMKII phosphorylation reactions, and the subsequent Western blot analysis or CaM overlay were performed as described previously (11, 12, 14, 17). For CaM overlay, gel electrophoresis and electroblot analysis were performed as for Western analysis. However, instead of immunodetection, membranes were incubated with biotinylated CaM (1:2400 dilution; STI Signal Transduction Products, San Clemente, CA, USA or Calbiochem, San Jose, CA, USA), with the same buffers as were used for Western blot analysis, but supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2. After 30 min incubation at room temperature, bound biotinylated CaM was detected with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), with 2 drops each of solutions A and B, combined in 15 ml buffer 20–30 min before exposure to the membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% BSA before incubation with biotinylated CaM or the phospho-T305 antibody (1:1000; Assay Biotech, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and in 5% dry milk before incubation with the antibodies against phospho-T286 (1:3000; PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO, USA) or CaMKIIα (CBα2; 1:2000; made in house).

Site-specific autophosphorylation of CaMKII

CaMKII (400 nM; subunit concentration) was phosphorylated at T286 in the presence of 1 μM CaM, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 nM ATP for 10 min on ice (a temperature that suppressed phosphorylation at other sites). Then, half of the reaction was stopped by 5 μM staurosporine (to prevent additional phosphorylation) before 3 mM EGTA was added, and the mixture was warmed to 30°C. For the other half of the reaction, additional T305/306 phosphorylation was induced by adding 3 mM EGTA and incubating for 10 min at 30°C before addition of 5 μM staurosporine. In both cases, these additions diluted the original T286 phosphorylation reaction 1:4, but maintained a concentration of 50 mM PIPES (pH 7.2). Note that the additional autophosphorylation reaction causes phosphorylation at residues other than T305/306 (although only T305/306 phosphorylation interferes with Ca2+/CaM binding; refs. 18, 19) and a band shift in the Western blot analysis that can also alter the quantification of the immunodetection (in this study, a nonsignificant reduction to 92±11%); this effect was corrected for in the quantification of GluN2B binding.

CaMKII binding to GluN2B in vitro

Binding of CaMKII to immobilized GST fusion proteins with the cytoplasmic C terminus of GluN2B was conducted and analyzed essentially as previously reported (11, 13), and induced by either prephosphorylation at T286 or T286D mutation. The binding reactions contained 30–50 nM CaMKII (subunits), 50 mM PIPES (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5–1 mM EGTA, 100 mg/ml BSA, and either 50% of the site-specific phosphorylation reaction or 12.5% HEK cell extract (for binding of the GFP-CaMKII T286D mutants). For comparing binding of the T286D mutants, binding reactions were adjusted to contain equal amounts of HEK cell extract, and 100 μM ADP (but no ATP or kinase inhibitors) was added.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative distributions were compared by KS test. Other analyses were by ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis, unless indicated otherwise. Bar graphs represent means ± sem, and n indicates the number of neurons or individual binding reactions analyzed.

RESULTS

Efficient CaMKIIα knockdown to allow efficient reexpression for postsynaptic analysis

To allow CaMKII reexpression after knockdown, a plasmid-based shRNA was designed to target a 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the CaMKIIα mRNA that is lacking in our expression vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, this shRNA reduced CaMKIIα expression in cultured hippocampal neurons (11–12 DIV) efficiently and to the same extent as a previously described shRNA (20) that targets the coding region (Fig. 1). Based on immunofluorescence intensity, CaMKIIα levels were reduced by >80% (Fig. 1). This result is likely an underestimate, as the method does not allow for subtraction of nonspecific background staining. Based on this conservative knockdown estimate and the ∼4-fold overexpression achieved by our CaMKII expression vectors in 12 DIV neurons 2 d after transfection (21), knockdown/reexpression results in a ∼1:20 ratio of endogenous to reexpressed CaMKII (i.e., on average, <1 endogenous CaMKII subunit in every 12meric holoenzyme). Thus, any measurable holoenzyme characteristics after knockdown/reexpression are determined by the reexpressed CaMKII.

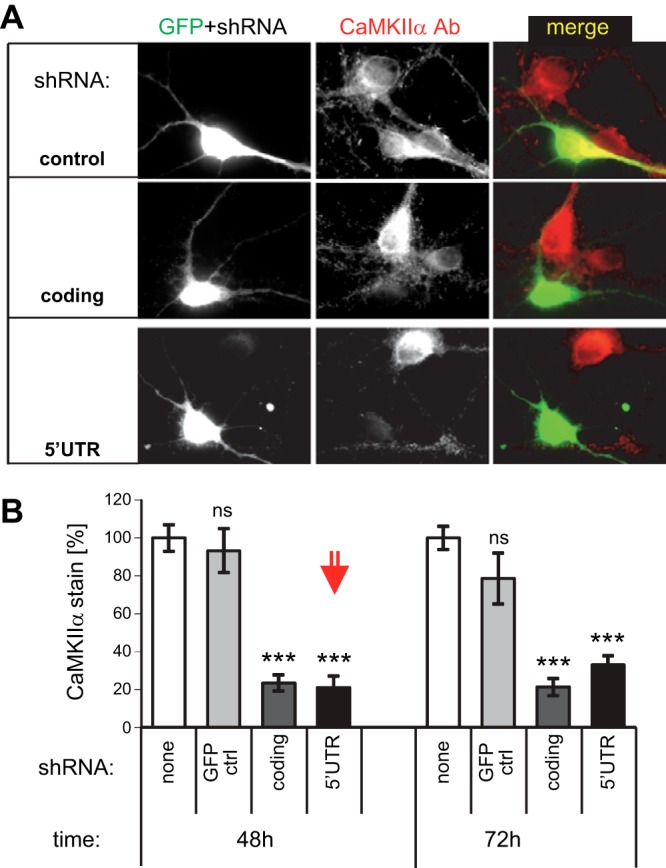

Figure 1.

Efficient knockdown of CaMKIIα expression in hippocampal neurons with shRNAs directed against the coding region (coding) or the 5′-UTR. A) Immunostaining of CaMKIIα in hippocampal cultures expressing GFP (as a transfection marker), with or without 2 different shRNAs, 48 h after transfection. B) Quantification showed equally efficient knockdown of endogenous CaMKIIα by 2 shRNAs (targeting the 5′-UTR or the coding region). The level of knockdown after 48 h (the condition used in further experiments, red arrow) was not further increased at 72 h after transfection, and no difference was seen between nontransfected and GFP-transfected control neurons. ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

In hippocampal cultures, endogenous CaMKIIα reaches maximal expression around 10 DIV (22). However, even at 12 DIV, the detected immunoreactivity of endogenous CaMKIIα in dissociated hippocampal cultures was only 10 ± 3% compared with that in native hippocampal tissue. Thus, the CaMKIIα overexpression in these neurons is still lower than the endogenous levels in the intact hippocampus.

Our transfection method efficiently cotransfects mixed plasmids (22), but transfects <1% of the neurons. Thus, any effect measured in the transfected neurons is mediated by postsynaptic CaMKII signaling, as presynaptic effects from other transfected neurons are drowned by the excess of nontransfected neurons. Indeed, our analysis showed no evidence of any contribution of CaMKII expression levels in presynaptic neurons. The results obtained for the mEPSC amplitudes (Fig. 2) were unaffected by excluding the highest and lowest 10% from the analysis, precluding the possibility that a few extreme events caused by the effects of presynaptic CaMKII expression could have distorted the results.

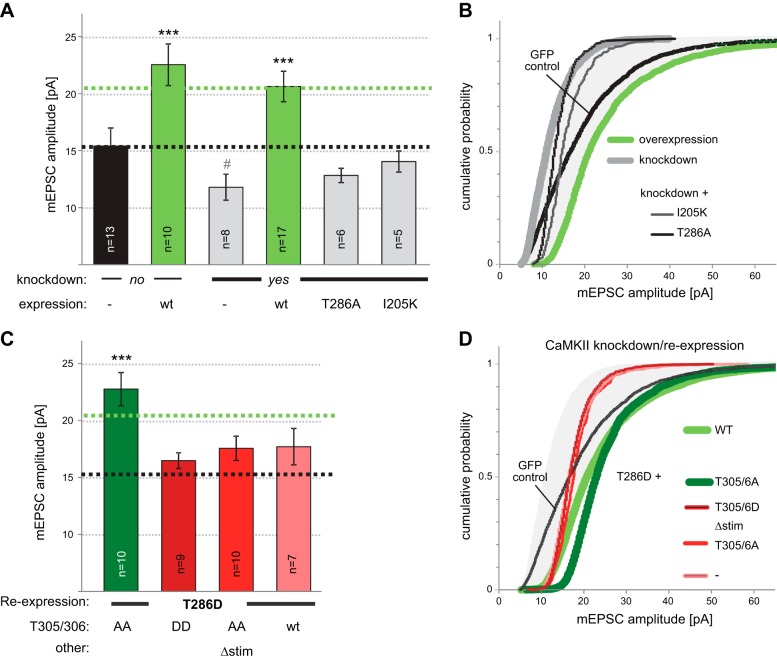

Figure 2.

Even constitutively autonomous CaMKIIα (T286D) requires further Ca2+/CaM stimulation for full enhancement of synaptic strength, as measured by mEPSC amplitude in hippocampal neurons after shRNA knockdown, mutant reexpression, or both. A) Mean amplitude was increased by overexpression of CaMKIIα, decreased by knockdown, and fully rescued by reexpression (to the same level as seen after overexpression). No significant rescue was observed with the autonomy-incompetent T286A mutant or the GluN2B-binding–incompetent I205K mutant. ***P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. no-knockdown, nonoverexpressing control; t test. B) Cumulative probability plots of mEPSC amplitude distribution for the conditions in panel A. C) Full rescue was observed with a T286D mutant, but only when its further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM was enabled by additional T305/306A mutation. Two different mutants that abolish Ca2+/CaM binding were used: T305/306D, which mimics inhibitory phosphorylation, and the Δstim mutant developed in this study, which does not introduce any negatively charged residues. Groups identified by gray, green, or red showed no difference within the groups, but differed from the other groups (ANOVA). ***P < 0.001 vs. control group. D) Cumulative probability plots of mEPSC amplitude distribution for the conditions in panel C.

Rescue of mEPSC amplitude required autonomy and binding to synaptic proteins

Consistent with a previous report (23), overexpression of GFP-CaMKIIα in hippocampal neurons significantly increased mEPSC amplitude, a measure of enhanced synaptic strength (Fig. 2A; for sample traces, see Supplemental Fig. S1A). By contrast, but also consistent with the previous results (23), mEPSC frequency, a measure of synapse number or presynaptic release probability, was unchanged (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Knockdown of endogenous CaMKIIα had the opposite effect, decreasing mEPSC amplitudes (Fig. 2A). Again, mEPSC frequency was not affected (Supplemental Fig. S1B). The apparent decrease in mean mEPSC amplitude compared to GFP control was significant only by t test (Fig. 2A), but the cumulative distribution of the individual mEPSC amplitudes was significantly shifted to lower amplitudes (Fig. 2B). This knockdown effect was completely rescued by reexpressing wild-type GFP-CaMKIIα. In fact, reexpression enhanced mEPSC amplitude to a level similar to that in overexpression without knockdown (Fig. 2A), an overshoot expected given the similar elevation in total CaMKIIα levels.

In contrast to wild-type GFP-CaMKIIα, no rescue of mean mEPSC amplitude was seen with the autonomy-incompetent T286A mutant (Fig. 2A). Rescue was also not seen with the I205K mutant, which shows impaired binding to GluN2B (24) and densin-180 (25), consistent with previous observations with GluN2B mutants that impair CaMKII binding (26, 27). Thus, enhancement of synaptic strength mediated by CaMKII required both CaMKII autonomy and synaptic protein interactions.

It should be noted that the T286A and I205K mutants significantly altered the distribution of mEPSC amplitudes compared with the GFP control (Fig. 2B), even though they did not significantly change their mean. In fact, expression of any CaMKII mutant resulted in tighter mEPSC distributions (i.e., steeper cumulative probability plots; Fig. 2), independent of their effects on mean mEPSC amplitude.

Rescue of mEPSC amplitude requires stimulated autonomy

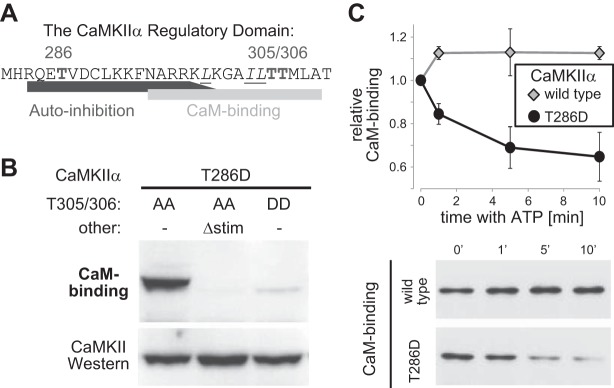

The full rescue of mEPSC amplitude after reexpression of wild-type GFP-CaMKIIα was also seen for constitutively autonomous T286D mutants, but only if they could be further stimulated (additional T305/306A mutation) and not if such stimulation was prevented (additional T305/306D, or Δstim, mutation) (Fig. 2C, D). Inhibitory T305/306 autophosphorylation in the Ca2+/CaM-binding region (Fig. 3A) blocks Ca2+/CaM stimulation (18, 28). Although the T305/306A mutation prevents this effect, the T305/306D mutation mimics it (due to the negatively charged D residues). The Δstim mutation is a combination mutant that also prevents Ca2+/CaM binding (Fig. 3B), but without introducing any charged residues. Here, the Δstim mutant also included the T305/T306A mutation, to prevent introduction of charges by autophosphorylation. The inhibitory autophosphorylation at T305/306 is triggered for autonomous CaMKII after dissociation of Ca2+/CaM (18) and would be expected to occur in the constitutively autonomous T286D mutants on addition of ATP (unless T305/306 is also mutated). Indeed, incubation with ATP in the absence of Ca2+/CaM did not affect wild-type CaMKII, but resulted in reduced Ca2+/CaM binding for a T286D mutant without additional mutations (Fig. 3C), as expected from T305/306 hyperphosphorylation. Thus, T286D T305/306A is the only constitutively autonomous mutant that can be efficiently further stimulated within cells. Indeed, T286D T305/306A was also the only autonomous mutant that fully rescued the mEPSC amplitude, whereas T286D without additional mutations behaved instead like the triple phosphomimetic T286D T305/306D mutant (as expected, on the basis of T305/306 hyperphosphorylation, disruption of Ca2+/CaM binding, or both). The distribution of mEPSC amplitudes was virtually identical for the T286D mutant and the mutants that additionally directly prevent Ca2+/CaM binding (Fig. 2D). By contrast, the T286D T305/306A mutant differed dramatically, the mean of mEPSCs was instead more similar to the wild-type, and the distribution of mEPSCs was shifted to even higher amplitudes compared with the wild-type. Together, these results show that both autonomy and its further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM are necessary for CaMKII-mediated enhancement of synaptic strength. Compared to reexpression of wild-type CaMKII, reexpression of constitutively autonomous mutants that cannot be further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM in fact reduced synaptic strength.

Figure 3.

Mutations and autophosphorylation reactions that interfere with Ca2+/CaM binding to CaMKII. A) Sequence of the CaMKIIα regulatory domain. Marked are the autophosphorylation sites T286 (generates autonomous activity) and T305/306 (interferes with Ca2+/CaM binding). Underlined and in italics are the residues mutated in Δstim to prevent Ca2+/CaM binding. B) GFP-CaMKII mutations T305/306D and Δstim prevent Ca2+/CaM binding, as determined by Ca2+/CaM overlay (top panel). Equal CaMKII amounts were verified by Western blot analysis (bottom panel). All mutants included an additional T286D mutation (as in Fig. 2). C) Incubation of GFP-CaMKII with ATP (without stimulation by Ca2+/CaM) reduced subsequent binding of Ca2+/CaM for the CaMKII T286D mutant, but not for wild-type kinase. Ca2+/CaM binding was assessed by Ca2+/CaM overlay.

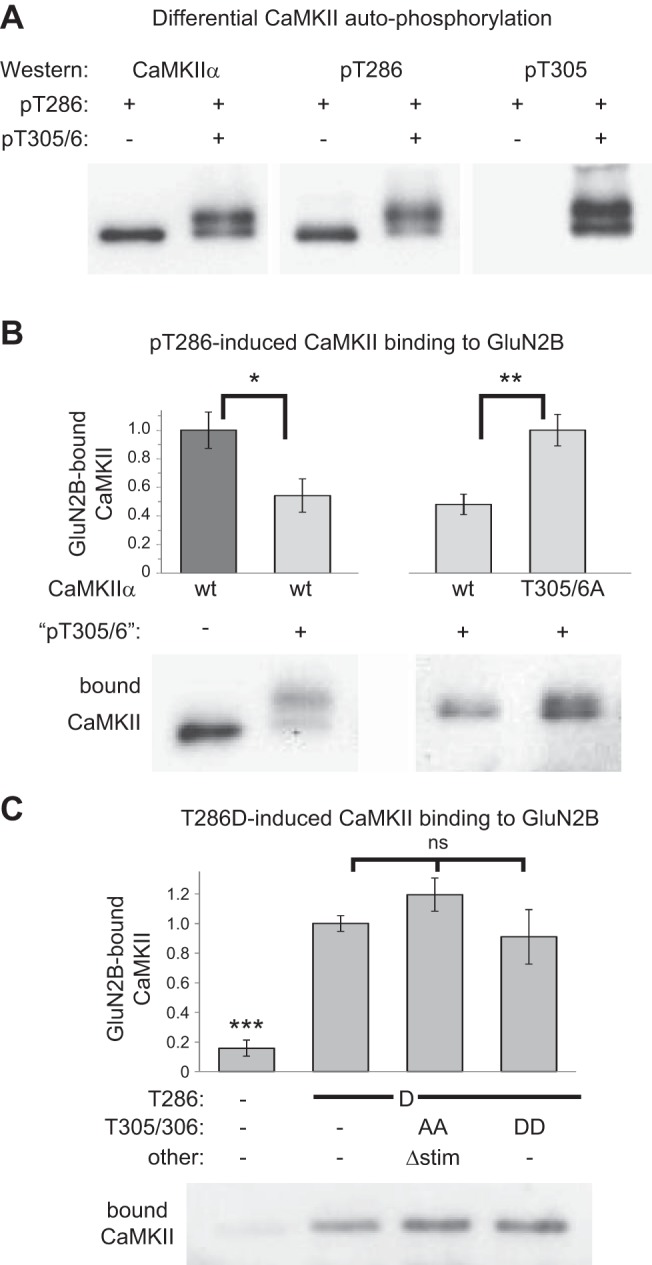

T305/306 phosphorylation directly reduces binding to GluN2B

CaMKII binding to GluN2B participates in enhancing synaptic strength (26, 27), consistent with our findings with the CaMKII I205K mutant (Fig. 2A). Thus, we decided to test the effects of T305/306 phosphorylation on CaMKII/GluN2B interaction. T305/306 phosphorylation had been suggested to reduce CaMKII binding to GluN2B (29); however, these experiments did not differentiate between a direct effect of the phosphorylation and an indirect effect via reduced Ca2+/CaM binding. Thus, in the current study, we devised a strategy to directly compare GluN2B binding of T286-phosphorylated CaMKII in the absence of Ca2+/CaM, either with or without additional T305/306 phosphorylation. (Note that either T286 phosphorylation or Ca2+/CaM binding alone is sufficient to induce CaMKII binding to GluN2B; refs. 24, 29, 30). Briefly, CaMKII was phosphorylated at T286 in the presence of Ca2+/CaM for 5 min on ice, conditions that prevent phosphorylation at T305/306 (12). Then, additional T305/306 phosphorylation was either induced (by chelation of Ca2+ and warming to 30°C) or prevented (by addition of staurosporine, to inhibit kinase activity before chelation of Ca2+ and warming). Indeed, this strategy resulted in the desired phosphorylation states, as determined by Western blot analysis with phosphoselective antibodies (Fig. 4A; note that the additional phosphorylation resulted in an additional band shift). The subsequent reactions to compare binding to immobilized GluN2B were performed in exactly the same buffer composition, both containing staurosporine to prevent any further phosphorylation. Notably, CaMKII binding to GluN2B is enhanced by nucleotides (13), but this effect is mimicked rather than prevented by the nucleotide-competitive inhibitor staurosporine (31). Even in the absence of Ca2+/CaM, the phospho-T286-induced CaMKII binding to GluN2B was significantly reduced by additional T305/306 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Next, binding of wild-type CaMKII and the T305/306A mutant was compared after pretreatment that induces T286 and T305/306 phosphorylation in wild-type CaMKII (as this treatment induces phosphorylation at other sites, as well, although without affecting Ca2+/CaM binding; ref. 18). As expected, under these conditions, GluN2B binding was significantly reduced for wild-type CaMKII compared with the T305/306A mutant (Fig. 4B), further validating that phosphorylation at T305/306 reduces binding. However, this phosphorylation effect was not mimicked by T305/306D mutation (Fig. 4C). In this case, binding in the absence of Ca2+/CaM was induced by T286D mutation, as the T286 phosphorylation cannot be induced for Ca2+/CaM-binding-incompetent CaMKII mutants; note that T286 autophosphorylation requires Ca2+/CaM binding, not only for kinase activation but also for exposing T286 as a substrate (32, 33). As expected, T286D mutation substituted for T286-phosphorylation in inducing CaMKII binding to GluN2B. However, additional mutation at T305/306 (either to A or D) had no significant effect (Fig. 4C). Thus, CaMKII T305/306D mutation did not cause the phospho-T305/306-induced reduction in GluN2B binding that was identified in this study, and the effect of this mutation on synaptic strength (Fig. 2C) cannot be explained by reduced GluN2B binding.

Figure 4.

T305/306 phosphorylation and T305/306D mutation reduces the CaMKII binding to GluN2B stimulated by T286 phosphorylation or T286D mutation in biochemical assays. A) A new strategy to generate T286-phosphorylated CaMKII in vitro, with or without additional T305/306 phosphorylation (see Materials and Methods for detail), was successful, as determined by Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against CaMKII, phospho-T286, or phospho-T305. B) CaMKII binding to the immobilized GluN2B cytoplasmic C terminus was reduced by the treatment that induced additional T305/306 phosphorylation (left panel). This treatment reduced binding of GFP-wild-type CaMKII compared to its T305/306A mutant (right panel). Binding was done in absence of Ca2+/CaM and instead induced by T286 phosphorylation (n=6). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; t test. C) GFP-CaMKII T286D mutation allowed GluN2B binding without autophosphorylation or Ca2+/CaM addition (n=9) This T286D-induced binding was not significantly affected (ns) by additional T305/306D or T305/306A mutation (in the latter case with the additional Δstim mutation that, similar to T305/306D, prevents Ca2+/CaM binding). ***P < 0.001.

Synaptic localization of the CaMKII mutants

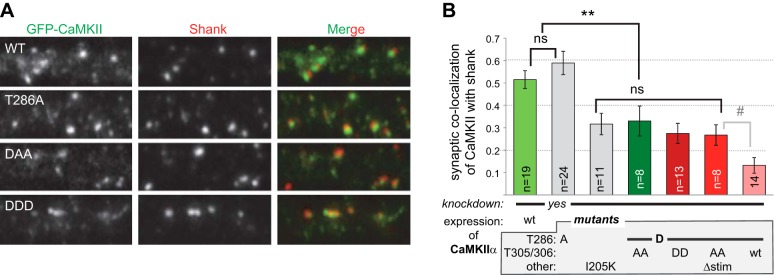

The differential effects of the various constitutively autonomous CaMKII mutants on mEPSC amplitudes could be explained by two distinct principal mechanisms: further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII by Ca2+/CaM may be required either to promote synaptic localization or to enhance activity of already localized kinase. Thus, synaptic localization of the CaMKII mutants was compared by their colocalization with a synaptic marker, shank (Fig. 5A). Localization of wild-type CaMKII and T286A were not distinguishable; if present at all, localization of the T286A mutant appeared slightly enhanced (Fig. 5B). Thus, lack of mEPSC rescue by the T286A mutant was not due to reduced synaptic localization. By contrast, localization of the GluN2B-binding-impaired I205K mutant was reduced by approximately half (Fig. 5B), consistent with the extent of the reduced CaMKII/NMDAR association in mice with a GluN2B mutation that blocks CaMKII binding (26). Although T286D mutants are competent for GluN2B binding (24), they all also showed significantly reduced synaptic localization (Fig. 5B). However, all of the T286D mutants with additional mutations that either allow or prevent further Ca2+/CaM stimulation showed the same level of reduced synaptic localization. Thus, differential localization was not the cause of their diverse effects on mEPSC amplitude (as shown in Fig. 2A). The T286D mutant without additional mutation appeared to localize to synapses even less (Fig. 5B), consistent with reduced GluN2B binding by T305/306 phosphorylation but not by T305/306 mutation (Fig. 4). However, this further reduction in synaptic localization was statistically significant only in a t test and not by ANOVA. Taken together, these results show that neither the requirement of autonomy nor its further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM stimulation for enhancement of synaptic strength was due to regulation of synaptic localization. Thus, instead, further stimulation of local autonomous CaMKII activity is essential for full enhancement of synaptic strength, thereby providing the first direct evidence of a physiological function of this long-known CaMKII regulation.

Figure 5.

Synaptic localization of CaMKIIα and its mutants indicates requirement of Ca2+/CaM binding for local regulation (nor regulation of localization). A) Synaptic localization of GFP-CaMKII in hippocampal neurons was assessed by colocalization with shank as the synaptic marker. Endogenous CaMKIIα was knocked down by shRNA. B) Quantification showed equal synaptic localization of wild-type CaMKII and T286A, whereas localization of all T286D mutants was reduced to an equal degree. Further reduced localization of the T286D mutant without additional mutation became significant only in a t test. #P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms by which CaMKII enhances synaptic strength have been the subject of intensive investigation for >20 yr (reviewed in refs. 1, 34). This study showed a requirement not only for phospho-T286-induced autonomous CaMKII activity (2, 12) but also for its further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM, even when autonomous activity is allowed for prolonged periods. The ability of Ca2+/CaM to further stimulate autonomous CaMKII activity had been thought to prevent complete uncoupling of CaMKII signaling from subsequent cellular Ca2+ stimuli, while allowing a form of molecular memory by the lower level of autonomous CaMKII activity (8). However, the actual physiological effects of this regulatory principle on synaptic strength remained to be elucidated. In the current study, the readout of synaptic strength was mEPSC amplitude in dissociated hippocampal neurons, where the level of CaMKIIα expression limits mEPSC amplitude. Overexpression of CaMKIIα in these neurons increases the amount of CaMKII by ∼4-fold (21) and increases mEPSC amplitude (23). However, the CaMKIIα level in native hippocampus is even higher and likely no longer limits synaptic strength (35). Notably, the full increase in mEPSC amplitude was also seen in constitutively autonomous CaMKII mutants (T286D), but only when they could be further stimulated by Ca2+/CaM (additional T305/306A mutation) and not when such stimulation was prevented (either by T305/306D mutation or by combining T305/306A mutation with the Δstim mutations that prevent Ca2+/CaM binding without introducing any charged residues). A T286D mutant without any additional mutation also failed to enhance synaptic strength, consistent with hyperphosphorylation at T305/306 (which also prevents Ca2+/CaM binding) triggered by autonomous CaMKII activity (18, 28). Although all T286D mutants showed reduced basal localization to excitatory synapses, compared with wild-type CaMKII (or T286A), this reduction was to the same level for all of them. Thus, further Ca2+/CaM stimulation of the constitutively autonomous CaMKII mutants was necessary for local regulation of activity rather than for regulation of basal localization. Notably, T286 phosphorylation or T286D mutation is not known to impair any CaMKIIα interaction with synaptic proteins; on the contrary, it instead appears to enhance several such interactions (reviewed in refs. 1, 36, 37). However, the reduced localization of T286D mutants to excitatory synapses under basal conditions is consistent with results in a previous report, which instead showed increased localization to inhibitory synapses (38). Notably, the T286D mutant without additional T305/306 mutation appeared to localize to synapses even less than T286D mutants with T305/306 mutation. Although this difference was significant only by t test (and not by ANOVA), it indicated that T305/306 phosphorylation could have a further reducing effect on synaptic localization that is not mimicked by the T305/306D mutation. Indeed, whereas T305/306 phosphorylation was found to directly reduce CaMKII binding to GluN2B, the T305/306D mutation had no effect. Thus, CaMKII T305/306D mutation mimics some but not all effects of phosphorylation at these sites. It blocks Ca2+/CaM binding after T305/306 phosphorylation (18, 28), but not the reduction in GluN2B binding identified in the current study. By contrast, T286D mutation mimics the effects of T286 phosphorylation both regarding generation of autonomous activity (39, 40) and CaMKII binding to GluN2B (24, 29, 30).

A previous study that tested the effect of autonomous CaMKII with additional T305/306 mutations in neurons obtained slightly different results (35), warranting some detailed discussion. In that study, the only Ca2+/CaM-binding–incompetent mutant was the T305/306D phosphomimetic, and the synaptic localization of the mutants was not compared. Thus, the results did not allow distinction between functions of Ca2+/CaM-stimulated activity or localization, or other potential direct effects of T305/306 phosphorylation. In contrast to the results in the current study and those in other work, this previous study found no effect of wild-type CaMKII overexpression on synaptic strength (35), probably because of the lower endogenous CaMKII expression in dissociated hippocampal neurons compared to higher expression in organotypic cultures, which may no longer be limiting for synaptic strength. In contrast to the approach used in the current study, in the previous study, endogenous CaMKII was not knocked down during the overexpression. CaMKII forms 12meric holoenzymes, and some mutants may exert additional dominant negative effects on endogenous wild-type CaMKII within these holoenzymes. Although such dominant negative effects can be used advantageously to disrupt endogenous CaMKII signaling (41), they also have the potential to confound the interpretation of results when the intent is to examine the direct effect of a specific lack- or gain-of-function mutation. This confounding effect can be further complicated when comparing mutants, and only some but not all have additional dominant effects on endogenous CaMKII. Indeed, the previous study indicated such a dominant negative effect. Although a T286/305/306D mutant failed to fully rescue synaptic strength in the current study, it reduced synaptic strength in the previous study (35). Notably, however, when the effect of T286/305/306D mutant reexpression was compared to wild-type reexpression (i.e., conditions with equal total CaMKII levels), the mutant reduced synaptic strength also in the current study. Thus, all of these results are consistent with our conclusion that stimulated autonomy of CaMKII is necessary to enhance synaptic strength, whereas lack of such stimulation reduces it. These opposing effects can be explained by differential substrate-class selection by autonomous CaMKII in the presence vs. absence of additional Ca2+/CaM stimulation, specifically including differential substrate-site selection on AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit 1 (GluA1; formerly GluR1; ref. 3).

Studying the functional requirement for further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII by Ca2+/CaM has an inherent limitation: It requires using autonomous mutants such as T286D and cannot be achieved with actual T286-phosphorylated CaMKII. It is impossible to induce T286 phosphorylation on CaMKII mutants that cannot bind Ca2+/CaM, because of the requirement of Ca2+/CaM binding not only to the kinase subunit, but also to the substrate subunit during the intersubunit intraholoenzyme T286 phosphorylation reaction (32, 33). For instance, lack of LTP in mice with the Ca2+/CaM-binding–impaired CaMKII T305/306D mutant (42) is readily explained by lack of any stimulation and T286 autophosphorylation; facilitated LTP in mice with the CaMKII T305/306AV mutant (42) could be due to generally facilitated stimulation and T286 autophosphorylation. Thus, although these mice provided important information about neuronal functions of CaMKII regulation (and the results obtained with them are consistent with our findings here), they cannot provide any direct information about the role of further stimulation of autonomous CaMKII. The requirement to use the constitutively autonomous T286D mutants for studying cellular functions of further Ca2+/CaM-stimulated autonomy is a restriction, but it also alleviates the necessity to induce T286 phosphorylation by neuronal stimulation that would trigger other signaling cascades and thus has the advantage that the results solely reflect the direct effect of the CaMKII mutants, without the influence of additional confounding pathways. This advantage is particularly important in our experimental system of dissociated hippocampal neurons, as the high endogenous neuronal activity readily provides the required additional Ca2+/CaM stimulation of autonomous CaMKII (and as dissociated cultures do not allow for the normal electrical LTP-stimulus paradigms in the first place). In addition, the inherent limitation of our study is further mitigated by the fact that the CaMKII T286D mutation induces autonomous activity very similar to that seen after T286 phosphorylation (39, 40). Although T286 phosphorylation is reversed rapidly after LTP stimuli (43, 44), the autonomy of the T286D mutant is constitutive. Thus, an alternative finding of enhanced synaptic strength by prolonged constitutive autonomy could not have ruled out the requirement for additional stimulation when autonomy is more short-lived. However, even prolonged constitutive autonomy required further stimulation to enhance synaptic strength. If it is present at all, further enhancement of the rate of kinase activity by Ca2+/CaM should be functionally even more significant for the T286 phosphorylated form of CaMKII compared with the T286D mutant that is needed to study such functions experimentally.

The results of this study show that stimulated and autonomous CaMKII activities are not functionally equivalent. Even when autonomous activity was allowed over prolonged periods, further stimulation by Ca2+/CaM was necessary to enhance synaptic strength. Interestingly, the lack of such stimulation did not simply result in a lack of function, but instead had the opposite effect, decreasing synaptic strength.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01NS081248 (to K.U.B), R01NS076577 (to T.B), T32GM007635 (to K.B. and H.O.), and P30NS04154 (to the University of Colorado Center) and by a Thorkildsen fellowship (to I.B.).

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- CaM

- calmodulin

- CaMKII

- Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II

- DIV

- days in vitro

- GluN2B

- NMDA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2B

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- LTD

- long-term depression

- LTP

- long-term potentiation

- mEPSC

- miniature excitatory postsynaptic current

- UTR

- untranslated region

REFERENCES

- 1. Coultrap S. J., Bayer K. U. (2012) CaMKII regulation in information processing and storage. Trends Neurosci. 35, 607–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giese K. P., Fedorov N. B., Filipkowski R. K., Silva A. J. (1998) Autophosphorylation at Thr286 of the alpha calcium-calmodulin kinase II in LTP and learning. Science 279, 870–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coultrap S. J., Freund R. K., O'Leary H., Sanderson J. L., Roche K. W., Dell'Acqua M. L., Bayer K. U. (2014) Autonomous CaMKII mediates both LTP and LTD using a mechanism for differential substrate site selection. Cell Reports, 6, 431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller S. G., Kennedy M. B. (1986) Regulation of brain type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase by autophosphorylation: a Ca2+-triggered molecular switch. Cell 44, 861–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lou L. L., Lloyd S. J., Schulman H. (1986) Activation of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase by autophosphorylation: ATP modulates production of an autonomous enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83, 9497–9501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schworer C. M., Colbran R. J., Soderling T. R. (1986) Reversible generation of a Ca2+-independent form of Ca2+(calmodulin)-dependent protein kinase II by an autophosphorylation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8581–8584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffith L. C. (2004) Regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activation by intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. J. Neurosci. 24, 8394–8398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coultrap S. J., Buard I., Kulbe J. R., Dell'Acqua M. L., Bayer K. U. (2010) CaMKII autonomy is substrate-dependent and further stimulated by Ca2+/calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17930–17937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bayer K. U., LeBel E., McDonald G. L., O'Leary H., Schulman H., De Koninck P. (2006) Transition from reversible to persistent binding of CaMKII to postsynaptic sites and NR2B. J. Neurosci. 26, 1164–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Leary H., Lasda E., Bayer K. U. (2006) CaMKIIbeta association with the actin cytoskeleton is regulated by alternative splicing. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4656–4665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coultrap S. J., Bayer K. U. (2012) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). In Neuromethods: Protein Kinase Technologies (Mukai H., ed) pp. 49–72, Humana, New York [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coultrap S. J., Barcomb K., Bayer K. U. (2012) A significant but rather mild contribution of T286 autophosphorylation to Ca2+/CaM-stimulated CaMKII activity. PLoS One 7, e37176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Leary H., Liu W. H., Rorabaugh J. M., Coultrap S. J., Bayer K. U. (2011) Nucleotides and phosphorylation bi-directionally modulate Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) binding to the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit GluN2B. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31272–31281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vest R. S., Davies K. D., O'Leary H., Port J. D., Bayer K. U. (2007) Dual mechanism of a natural CaMKII inhibitor. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5024–5033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robertson H. R., Gibson E. S., Benke T. A., Dell'Acqua M. L. (2009) Regulation of postsynaptic structure and function by an A-kinase anchoring protein-membrane-associated guanylate kinase scaffolding complex. J. Neurosci. 29, 7929–7943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steinmetz C. C., Buard I., Claudepierre T., Nagler K., Pfrieger F. W. (2006) Regional variations in the glial influence on synapse development in the mouse CNS. J. Physiol. 577, 249–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buard I., Coultrap S. J., Freund R. K., Lee Y. S., Dell'Acqua M. L., Silva A. J., Bayer K. U. (2010) CaMKII “autonomy” is required for initiating but not for maintaining neuronal long-term information storage. J. Neurosci. 30, 8214–8220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanson P. I., Schulman H. (1992) Inhibitory autophosphorylation of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase analyzed by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 17216–17224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colbran R. J. (1993) Inactivation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by basal autophosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7163–7170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoogenraad C. C., Feliu-Mojer M. I., Spangler S. A., Milstein A. D., Dunah A. W., Hung A. Y., Sheng M. (2007) Liprinalpha1 degradation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates LAR receptor tyrosine phosphatase distribution and dendrite development. Dev. Cell 12, 587–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vest R. S., O'Leary H., Coultrap S. J., Kindy M. S., Bayer K. U. (2010) Effective post-insult neuroprotection by a novel Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20675–20682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fink C. C., Bayer K. U., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., Schulman H., Meyer T. (2003) Selective regulation of neurite extension and synapse formation by the beta but not the alpha isoform of CaMKII. Neuron 39, 283–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thiagarajan T. C., Piedras-Renteria E. S., Tsien R. W. (2002) alpha- and betaCaMKI: inverse regulation by neuronal activity and opposing effects on synaptic strength. Neuron 36, 1103–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bayer K. U., De Koninck P., Leonard A. S., Hell J. W., Schulman H. (2001) Interaction with the NMDA receptor locks CaMKII in an active conformation. Nature 411, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiao Y., Jalan-Sakrikar N., Robison A. J., Baucum A. J., 2nd, Bass M. A., Colbran R. J. (2011) Characterization of a central Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIalpha/beta binding domain in densin that selectively modulates glutamate receptor subunit phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24806–24818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halt A. R., Dallpiazza R. F., Zhou Y., Stein I. S., Qian H., Juntti S., Wojcik S., Brose N., Silva A. J., Hell J. W. (2012) CaMKII binding to GluN2B is important for Morris water maze task recall in the early consolidation phase. EMBO J. 31, 1203–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barria A., Malinow R. (2005) NMDA receptor subunit composition controls synaptic plasticity by regulating binding to CaMKII. Neuron 48, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Colbran R. J., Soderling T. R. (1990) Calcium/calmodulin-independent autophosphorylation sites of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: studies on the effect of phosphorylation of threonine 305/306 and serine 314 on calmodulin binding using synthetic peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 11213–11219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leonard A. S., Bayer K. U., Merrill M. A., Lim I. A., Shea M. A., Schulman H., Hell J. W. (2002) Regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II docking to N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors by calcium/calmodulin and alpha-actinin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48441–48448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strack S., McNeill R. B., Colbran R. J. (2000) Mechanism and regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II targeting to the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23798–23806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barcomb K., Coultrap S. J., Bayer K. U. (2013) Enzymatic activity of CaMKII is not required for its interaction with the glutamate receptor subunit GluN2B. Mol. Pharmacol. 84, 834–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hanson P. I., Meyer T., Stryer L., Schulman H. (1994) Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron 12, 943–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rich R. C., Schulman H. (1998) Substrate-directed function of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28424–28429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lisman J., Yasuda R., Raghavachari S. (2012) Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 169–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pi H. J., Otmakhov N., Lemelin D., De Koninck P., Lisman J. (2010) Autonomous CaMKII can promote either long-term potentiation or long-term depression, depending on the state of T305/T306 phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 30, 8704–8709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Colbran R. J. (2004) Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 378, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Merrill M. A., Chen Y., Strack S., Hell J. W. (2005) Activity-driven postsynaptic translocation of CaMKII. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marsden K. C., Shemesh A., Bayer K. U., Carroll R. C. (2010) Selective translocation of Ca2+/calmodulin protein kinase IIalpha (CaMKIIalpha) to inhibitory synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 20559–20564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fong Y. L., Taylor W. L., Means A. R., Soderling T. R. (1989) Studies of the regulatory mechanism of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: mutation of threonine 286 to alanine and aspartate. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 16759–16763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Waldmann R., Hanson P. I., Schulman H. (1990) Multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase made Ca2+ independent for functional studies. Biochemistry 29, 1679–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loweth J. A., Li D., Cortright J. J., Wilke G., Jeyifous O., Neve R. L., Bayer K. U., Vezina P. (2013) Persistent reversal of enhanced amphetamine intake by transient CaMKII inhibition. J. Neurosci. 33, 1411–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elgersma Y., Fedorov N. B., Ikonen S., Choi E. S., Elgersma M., Carvalho O. M., Giese K. P., Silva A. J. (2002) Inhibitory autophosphorylation of CaMKII controls PSD association, plasticity, and learning. Neuron 36, 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee S. J., Escobedo-Lozoya Y., Szatmari E. M., Yasuda R. (2009) Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature 458, 299–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lengyel I., Voss K., Cammarota M., Bradshaw K., Brent V., Murphy K. P., Giese K. P., Rostas J. A., Bliss T. V. (2004) Autonomous activity of CaMKII is only transiently increased following the induction of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 3063–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.