Abstract

Thyrotropin (TSH) activation of the TSH receptor (TSHR), a 7-transmembrane-spanning receptor (7TMR), may have osteoprotective properties by direct effects on bone. TSHR activation by TSH phosphorylates protein kinases AKT1, p38α, and ERK1/2 in some cells. We found TSH-induced phosphorylation of these kinases in 2 cell lines engineered to express TSHRs, human embryonic kidney HEK-TSHR cells and human osteoblastic U2OS-TSHR cells. In U2OS-TSHR cells, TSH up-regulated pAKT1 (7.1±0.5-fold), p38α (2.9±0.4-fold), and pERK1/2 (3.1±0.2-fold), whereas small molecule TSHR agonist C2 had no or little effect on pAKT1 (1.8±0.08-fold), p38α (1.2±0.09-fold), and pERK1/2 (1.6±0.19-fold). Furthermore, TSH increased expression of osteoblast marker genes ALPL (8.2±4.6-fold), RANKL (21±5.9-fold), and osteopontin (OPN; 17±5.3-fold), whereas C2 had little effect (ALPL, 1.7±0.5-fold; RANKL, 1.3±0.6-fold; and OPN, 2.2±0.7-fold). β-Arrestin-1 and -2 can mediate activatory signals by 7TMRs. TSH stimulated translocation of β-arrestin-1 and -2 to TSHR, whereas C2 failed to translocate either β-arrestin. Down-regulation of β-arrestin-1 by siRNA inhibited TSH-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38α, and AKT1, whereas down-regulation of β-arrestin-2 increased phosphorylation of AKT1 in both cell types and of ERK1/2 in HEK-TSHR cells. Knockdown of β-arrestin-1 inhibited TSH-stimulated up-regulation of mRNAs for OPN by 87 ± 1.7% and RANKL by 73 ± 2.4%, and OPN secretion by 74 ± 10%. We conclude that TSH enhances osteoblast differentiation in U2OS cells that is, in part, caused by activatory signals mediated by β-arrestin-1.—Boutin, A., Eliseeva, E., Gershengorn, M. C., Neumann, S. β-Arrestin-1 mediates thyrotropin-enhanced osteoblast differentiation.

Keywords: TSH receptor, signaling, phosphokinases, bone, osteopontin

Thyrotropin (TSH) activation of the TSH receptor (TSHR), a 7-transmembrane-spanning receptor (7TMR), stimulates the function of thyroid follicular cells (thyrocytes), leading to biosynthesis and secretion of thyroid hormones. The TSHR is involved in several thyroid pathologies (1), and thyroid diseases are known to affect the equilibrium between bone resorption and deposition. Hyperthyroidism and use of thyroid hormones to suppress TSH in patients with thyroid cancer or goiter have an adverse effect on bone and are associated with osteoporosis (2). Juvenile acquired and poorly controlled hypothyroidism is associated with delayed bone age and growth arrest (3). Recently it has been shown that TSH may play a direct role in bone homeostasis hitherto attributed solely to thyroid hormones (4, 5). TSH displayed osteoprotective effects in mice by preventing bone loss after ovariectomy (6). TSH has also been shown to inhibit osteoclast differentiation in mouse bone marrow-derived cells (4) and induce osteoblastogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cell cultures (7).

Although β-arrestins were discovered as cellular factors that inhibit signaling by G-protein-coupled 7TMRs by sterically inhibiting G-protein coupling, they are now known to be important scaffolding proteins for internalization, desensitization, and activation of several G-protein-independent signal transduction pathways (8). There are 2 isoforms, β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2, that have some overlapping and some distinct functions, and the same β-arrestin exhibits different functions with different 7TMRs. Three general paradigms have been found. 1) For example, for the angiotensin type 1A receptor (9) and the vasopressin type 2 receptor (10), β-arrestin-2 activates extracellular-signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2; p44/p42MAPK), whereas β-arrestin-1 inhibits. 2) For the β-adrenergic type 2 receptor (11) and the parathyroid hormone 1 receptor (PTH1R; ref. 12), both β-arrestin isoforms are required for ERK1/2 signaling. 3) For the protease-activated receptor type 1 (13), β-arrestin-1 activates ERK1/2 and β-arrestin-2 inhibits.

The physiological actions of TSH have been thought to be mediated by classic heterotrimeric G-protein-signaling pathways. TSH binds to TSHR, a 7TMR, and activates several G proteins, including Gαs, which stimulates the cAMP pathway, and Gαq/11, which stimulates the phosphoinositide pathway (14). In addition, TSHR has been found to activate the mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK1/2 (15) and p38 kinase (16) and AKT (17). The activation of these 3 kinases by other 7TMRs is known to be mediated, in part, by β-arrestins (8). Recently parathyroid hormone (PTH), which serves as the primary regulator of bone and mineral metabolism and acts through its 7TMR PTH1R, has been shown to promote translocation of both β-arrestin-1 and -2 and activation of ERK1/2 (12). Moreover, the findings obtained using a β-arrestin signaling-biased agonist suggest that the β-arrestin-2-dependent pathway selectively contributes to anabolic bone formation and does not stimulate bone resorption (18). At the same time, nonselective PTH-mediated osteoblast-osteoclast coupling is cAMP-dependent, and sustained cAMP signaling in the absence of β-arrestin interaction promotes bone turnover (19, 20). Most reported physiological actions of TSH are mediated by G proteins, and to our knowledge, β-arrestin-mediated TSHR signaling pathways and their potential role in bone physiology have not been reported.

In this study we use U2OS cells, a cell line derived from a human osteosarcoma that has been shown to differentiate into osteoblasts under appropriate conditions (21), to study the effects of TSHR activation in a model system of human bone precursors. We show that TSHR activation leads to the up-regulation of osteoblast marker genes and that this effect is mediated by β-arrestin-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of human embryonic kidney (HEK)-EM 293 expressing TSHR (HEK-TSHR) cells, U2OS expressing TSHR (U2OS-TSHR) cells, U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1 cells, and U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells

The generation of a stable HEK-TSHR cell line was described previously (22). We established a U2OS-TSHR cell line using the expression vector for human TSHR that was described elsewhere (23). U2OS [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) HTB-96; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA] cells were transfected with the cDNA encoding TSHR using FuGene X-treme Gene transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Hygromycin (250 μg/ml; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used as a selection marker. Subsequently, positive clones were enriched for TSHR by FACS (BD FACS ARIA 2; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using Alexa647-anti-TSHR antibody. U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1 cells and U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells were purchased from DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA, USA).

HEK-TSHR cells were grown in DMEM (Life Technologies). U2OS-TSHR cells were cultured in EMEM (ATCC). DMEM and EMEM were supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. For U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1 and U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells, EMEM was also supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 500 μg/ml geneticin (Cellgro; Corning, Manassas, VA, USA).

Phospho-kinase array

HEK-TSHR cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well in DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 h, cells were serum starved overnight in DMEM containing 10 mM HEPES. Subsequently, cells were treated with 10 μM bovine TSH (bTSH; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 or 15 min. Following incubation, plates were placed on ice; cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed. Cell lysates (300 μg total protein/sample) were applied to nitrocellulose membranes and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions for the human Phospho-Kinase Array (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The membranes were exposed to an autoradiography Biomax light film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) for the detection of the signal. This phosphokinase array allowed the simultaneous detection of the relative levels of 46 kinase phosphorylation sites.

Measurement of phosphorylation of phosphokinases by ELISA

HEK-TSHR cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1.3 × 105 cells/well in DMEM containing 10% FBS and incubated for 48 h. U2OS-TSHR cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 24 h in EMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 or 48 h, cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing 10 mM HEPES overnight, bTSH or the small molecule ligand C2 (24) were added to the cells without replacing medium, and cells were incubated for 5 to 30 min at 37°C in a humidified incubator. Following incubation, plates were placed on ice; cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer 6 from the Surveyor IC human/mouse/rat phospho-kinase immunoassay kit (R&D Systems). Phospho-ERK1 (T202/Y204)/ERK2 (T185/Y187), phospho-p38α (T180/Y182), and phospho-AKT1 (S473) were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were analyzed in a SpectraMax Plus384 Absorbance Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Protein assay

Total protein was determined by the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, using BSA as a standard.

Transfection of HEK-TSHR and U2OS-TSHR cells with siRNA

HEK-TSHR and U2OS-TSHR cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.3 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with On-TargetPlus Smart pool human β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 siRNA or On-TargetPlus nontargeting pool siRNA using DharmaFect 1 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). At 48 h after transfection, cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing 10 mM HEPES overnight, bTSH was added to the wells without replacing medium, and cells were incubated for 5 min up to 60 min at 37°C in a humidified incubator. Measurements of phosphorylation of phosphokinases and data analysis were performed as described above.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was purified using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was prepared using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RT-PCR was performed in 25 μl reactions using cDNA prepared from 100 ng or less of total RNA and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Levels of mRNA were measured using primers and probes from Applied Biosystems. Quantitative RT-PCR results were normalized to GAPDH to correct for differences in RNA input.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates prepared in lysis buffer 6 for phosphokinase ELISAs were also used for Western blot analysis. Next, 30 μg total protein was separated in 10% NuPage Novex Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transferred to an Invitrolon PVDF membrane (Invitrogen) for immunoblotting. β-Arrestin-1 was detected with a rabbit monoclonal anti-β-arrestin-1 antibody (diluted 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). β-Arrestin-2 was detected with rabbit monoclonal anti-β arrestin-2 antibody (diluted 1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). GAPDH was detected with a rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (dilution: 1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology).

Measurement of cAMP production

U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells

We seeded 2.2 × 105 cells/well into 24-well plates. After 24 h, the cells were incubated for 60 min in HBSS/10 mM HEPES with 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; Sigma-Aldrich) and increasing concentrations of TSH or the small molecule ligand C2 (24) at 37°C. After aspiration of the incubation medium, cells were lysed using lysis buffer of the cAMP-Screen Direct System (Applied Biosystems), and total cAMP content was determined as described by the manufacturer. The chemiluminescence signal was measured in a Victor3 V 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA).

HEK-TSHR cells

The total cAMP content in the cell lysates prepared in lysis buffer 6 for phospho-kinase ELISAs was determined using the cAMP-Screen Direct System according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, HEK-TSHR cells were transfected with nontargeting siRNA, β-arrestin-1 siRNA, or β-arrestin-2 siRNA as described above. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were serum starved overnight and then treated with 10 μM TSH for 5 min up to 60 min. The samples were not treated with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. The chemiluminescence signal was measured, and the data analysis was performed as described above.

β-Arrestin assay

β-Arrestin-1 and -2 translocation to the TSHR after receptor activation with TSH or the small molecule ligand C2 was measured with the DiscoveRx PathHunter β-arrestin protein complementation assay (DiscoveRx), which measures recruitment of β-arrestin to TSHR. We seeded 2.5 × 104 cells/well into 96-well plates (Corning Costar 3610; Sigma-Aldrich) in PathHunter Cell Plating 5 reagent (DiscoveRx) 24 h before the experiment. U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1 cells and U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells were exposed to TSH concentrations between 0 and 10 μM and to C2 concentrations between 0 and 100 μM for 240 min or 90 min, respectively, in PathHunter Cell Plating 5 reagent, and afterward the signal (β-arrestin-1 or -2 translocation to the TSHR) was detected using the PathHunter Detection Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Osteopontin (OPN) secretion measurement by ELISA

U2OS-TSHR cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.3 × 105 cells/well. The β-arrestin-1 or -2 genes were knocked down by siRNA (see above). At 24 h after transfection with the siRNAs, the cells were incubated with or without 2 μM TSH for 5 d. Cell culture supernatants were used to determine OPN secretion levels by ELISA (OPN human ELISA kit; Abcam) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Data and statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Data are expressed as means ± se. The data were analyzed by Student's t test or 1-way ANOVA; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

TSH-induced TSHR activation leads to activation/phosphorylation of several phosphokinases in HEK-TSHR cells

As activation of signaling protein kinases has been found to be involved in bone homeostasis, we began our study to identify which phosphokinases are activated by TSH by using a phosphokinase array that allows the simultaneous detection of the relative levels of 46 kinase phosphorylation sites. We identified ERK1/2, the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38α, and AKT1 as the kinases that were strongly phosphorylated after TSHR activation (Supplemental Fig. S1). We confirmed in separate ELISAs for each phosphokinase that TSH-induced TSHR activation leads to phosphorylation of AKT1 (4.6±0.67-fold over basal), p38α (9.5±1.55-fold over basal), and ERK1/2 (13.6±2.96-fold over basal) in HEK-TSHR cells (Supplemental Fig. S2).

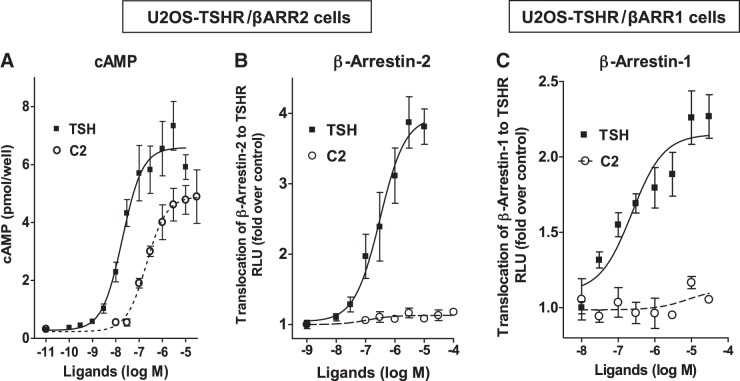

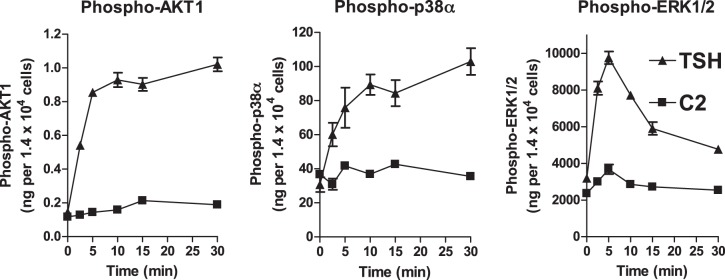

Unlike TSH, C2 does not stimulate phosphorylation of AKT1, ERK1/2, and p38α

Potential effects of TSHR activation on bone metabolism have been proposed (4, 25), and treatment with TSH has been shown to inhibit bone loss associated with ovariectomy in mice, a model of postmenopausal osteoporosis in humans (6). We have developed a small molecule ligand C2 (24) that is like TSH an agonist for cAMP signaling and might have potential for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Since it is known that PTH anabolic effects in bone are mediated in part by activation of protein kinases (18), we determined whether TSH and C2 cause phosphorylation of AKT1, ERK1/2, or p38α in U2OS cells, which are derived from a human osteosarcoma and are a model of osteoblast precursors (21). These cells have only a very low endogenous expression level of TSHR; therefore, we generated a cell line that stably expresses TSHR (U2OS-TSHR) and has the genotypic background of osteoblast lineage cells. While TSH-induced TSHR activation led to increases in phosphorylation of AKT1 (7.1±0.5-fold over basal), p38α (2.9±0.4-fold), and ERK1/2 (3.1±0.2-fold) as observed in HEK-TSHR cells, small molecule agonist C2 had only a weak effect on phosphorylation of AKT1 (1.8±0.08-fold over basal), p38α (1.2±0.09-fold), or ERK1/2 (1.6±0.19-fold) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

TSH, but not C2, stimulates phosphorylation of AKT1, ERK1/2, and p38α. U2OS-TSHR cells were serum starved overnight in EMEM and incubated with 2 μM TSH or 10 μM C2. At the indicated times, cells were lysed and analyzed by quantitative ELISA. The amount of phosphorylated phosphokinase in nanograms was normalized to the cell number in each sample. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with triplicate samples and are presented as means ± se.

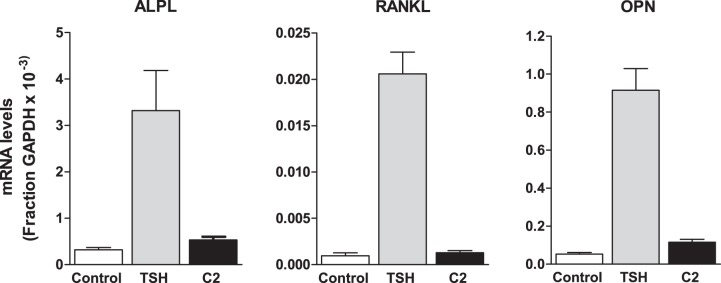

TSH, but not C2, stimulates osteoblastic differentiation of U2OS-TSHR cells

Next, we compared the effects of TSH and the small molecule agonist C2 on bone-specific gene expression. U2OS-TSHR cells were treated with 2 μM TSH or 10 μM C2 for 3 d. All studied osteoblastic markers showed increases in TSH-induced gene expression. We found that TSH treatment up-regulated alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) 8.2 ± 4.6-fold, receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL) 21 ± 5.9-fold, and OPN 17 ± 5.3-fold (Fig. 2). In contrast to TSH, C2 had little or no stimulating effect on ALPL (1.7±0.51-fold), OPN (2.2±0.72-fold), and RANKL (1.3±0.6-fold) gene expression (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

TSH, but not small molecule agonist C2, stimulates gene expression of osteoblastic markers. U2OS-TSHR cells were treated with 2 μM TSH or 10 μM C2 in serum-free EMEM. Data represent gene expression levels after 3 d. Samples were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are from 3 experiments with duplicate samples and are presented as means ± se.

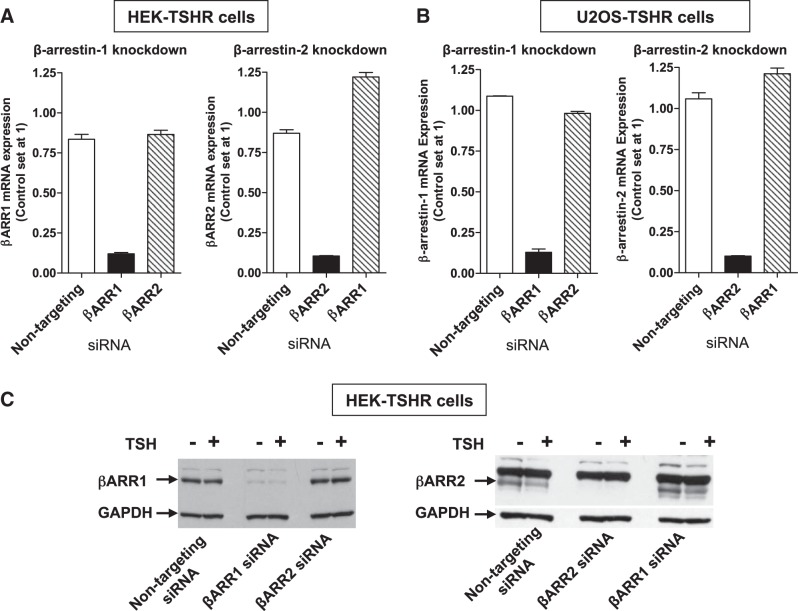

Activation by TSH, but not by C2, leads to translocation of β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 to the TSHR

We showed previously that C2 is an agonist for cAMP production, like TSH (24). As C2 has no or little effect on phosphorylation of phosphokinases (Fig. 1) and does not up-regulate osteoblast markers (Fig. 2), we compared TSH and C2 induction of β-arrestin translocation to the TSHR. We used engineered U2OS cells that were made to express TSHR and β-arrestin-1 (U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1) or TSHR and β-arrestin-2 (U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2) (DiscoveRx). We demonstrated TSH-stimulated translocation of both β-arrestins to the TSHR (Fig. 3B, C). The EC50 for TSH for recruitment of both β-arrestins was 300 nM (95% confidence interval, β-arrestin-1: 82–667 nM, β-arrestin-2: 132–720 nM) compared to 19 nM (95% confidence interval 10–35 nM) for cAMP production (Fig. 3A). Although C2 shows almost full efficacy for cAMP production in U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells when compared to TSH (Fig. 3A), its activation of the TSHR does not lead to translocation of either β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 (Fig. 3B, C).

Figure 3.

Activation by TSH, but not by small molecule agonist C2, leads to translocation of β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 to the TSHR. Arrestin translocation to the TSHR (B, C) was measured with the DiscoveRx PathHunter β-arrestin protein complementation assay. C2-induced TSHR activation leads to cAMP production (A), but, unlike TSH, C2 does not activate translocation of β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 to the TSHR (B, C). For the PathHunter β-arrestin translocation assay, U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-1 cells and U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of TSH and C2 for 240 or 90 min, respectively. For the cAMP assay, U2OS-TSHR/β-arrestin-2 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of TSH and C2 in HBSS with 1 mM IBMX for 60 min. Total cAMP levels were measured by ELISA. Data are from 2 experiments with duplicate samples and are presented as means ± se.

β-Arrestin-1 mediates TSHR-induced phosphorylation of signaling protein kinases in HEK-TSHR cells and in U2OS-TSHR cells

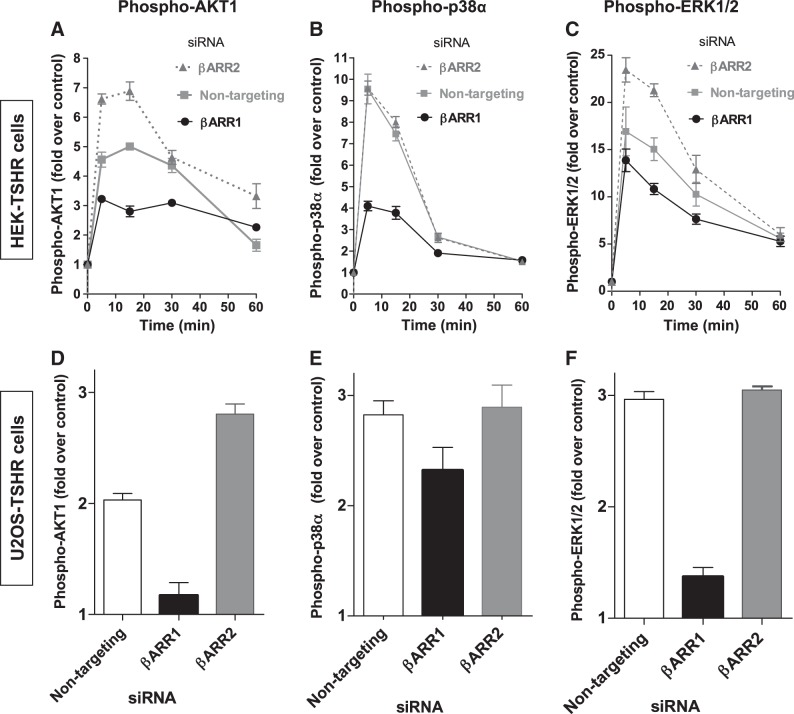

To determine whether β-arrestins mediate activation of phosphokinases by TSH, β-arrestin-1 and -2 were knocked down separately using siRNA as described in Materials and Methods. The knockdowns were confirmed by RT-qPCR in HEK-TSHR and U2OS-TSHR cells (Fig. 4A) and by immunoblots in HEK-TSHR cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 in HEK-TSHR and U2OS-TSHR cells by siRNA demonstrated by RT PCR (A, B) and by immunoblotting (C). A, B) HEK-TSHR cells (A) cells and U2OS-TSHR cells (B) were transfected with 50 or 100 nM nontargeting, β-arrestin-1 (βARR1), or β-arrestin-2 (βARR2) siRNA, respectively. At 72 h after transfection, βARR1 and βARR2 mRNAs were measured in parallel with experiments that determined the phosphorylation of phosphokinases. mRNA level in nontreated control cells was set at 1. Data are from 4 independent experiments with duplicate samples. C) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from nontreated (−), TSH-treated (+), and control HEK-TSHR cells (nontargeting siRNA) and after knockdown of βARR1 or βARR2 with siRNA. Antibodies used were targeted at β-arrestin-1, β-arrestin-2, and GAPDH. Blots are representative of 2 independent experiments.

After confirming the knockdown of β-arrestin-1 and -2, we tested whether β-arrestins play a role in phosphorylation/activation of phosphokinases by TSH and which β-arrestin is involved in activatory signaling. First, HEK-TSHR cells transfected with nontargeting, β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 siRNAs were stimulated with 10 μM TSH for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, and the phosphorylation of AKT1, p38α, and ERK1/2 was measured. In cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (control), the largest increase of TSH-induced phosphorylation was measured at 5 min for p38α and ERK1/2 (9.5±0.7- and 17±2.5-fold over control, respectively) and at 15 min for AKT1 (5.0±0.1-fold over control) (Fig. 5A–C). Knockdown of β-arrestin-1 led to a decrease in phosphorylation of all 3 phosphokinases at 5, 15, and 30 min compared to cells treated with nontargeting siRNA. At the times of largest TSH-induced increases, phosphorylation for AKT1, p38α, and ERK1/2 was decreased by 55 ± 11, 64 ± 5.8, and 30 ± 7.1%, respectively. In contrast, knockdown of β-arrestin-2 did not change the phosphorylation of p38α (Fig. 5B) but increased the phosphorylation of AKT1 and ERK1/2 at all time points measured (Fig. 5A, C). An increase of phospho-AKT1 of 47 ± 19% and of phospho-ERK1/2 of 41 ± 21% over control was measured. It has been shown that β-arrestin-2 has a predominant role in TSHR internalization and desensitization (26), which could explain why phosphorylation of AKT1 and ERK1/2 is increased after knockdown of β-arrestin-2. We measured cAMP production in HEK-TSHR cells after knockdown of β-arrestin-1 or -2 (Supplemental Fig. S3). We observed an increase in cAMP production in the cells treated with β-arrestin-2 siRNA compared to cells treated with nontargeting siRNA at all time points. The increase in cAMP production was 1.6 ± 0.2-, 1.9 ± 0.1-, 3.2 ± 1.4-, and 2.9 ± 1.0-fold over control at 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively. In contrast, in cells in which β-arrestin-1 was knocked down, cAMP production was not increased. These data for cAMP signaling confirm that β-arrestin-2 plays a pivotal role in TSHR desensitization.

Figure 5.

β-Arrestin-1 mediates TSHR phosphorylation of signaling protein kinases. TSH-induced phosphorylation of phosphokinases in HEK-TSHR cells (A–C) and U2OS-TSHR cells (D–F). Cells were transfected with nontargeting, β-arrestin-1 (βARR1), or β-arrestin-2 (βARR2) siRNA. 48 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved overnight and then treated with 10 μM TSH for the indicated times. Phosphorylation/activation of AKT1 (A, D), p38α (B, E), and ERK1/2 (C, F) in cell lysates was measured by ELISA. Amount of phosphorylated phosphokinase in nanograms was normalized to milligrams total protein in each sample. Data represent TSH-induced phosphorylation as fold over non-TSH treated controls. Data are from 2 experiments with duplicate samples and are presented as means ± se.

In U2OS-TSHR cells we found that like in HEK-TSHR cells (Fig. 5A–C), knockdown of β-arrestin-1, but not β-arrestin-2, decreased phosphorylation of AKT1, p38α, and ERK1/2 (Fig. 5D–F). TSH-induced AKT1, ERK1/2, and p38α phosphorylation was reduced by 83 ± 20, 81 ± 7.4, and 38 ± 9.4% in cells transfected with β-arrestin-1 siRNA, respectively. In cells transfected with β-arrestin-2 siRNA, TSH-induced AKT1 phosphorylation was increased 75 ± 15% over nontargeting control (Fig. 5D), while there was no difference for p38α and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (106±13 and 104±2.9%, respectively) compared to cells transfected with nontargeting control siRNA (Fig. 5E, F).

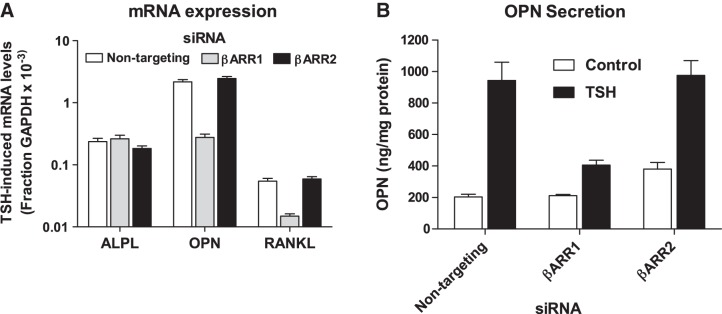

TSH effects on osteoblastogenesis are in part mediated by β-arrestin-1

Using a similar approach, we examined involvement of β-arrestins in mediation of TSH-induced expression of osteoblastic markers. Knockdown of β-arrestin-1, but not β-arrestin-2, inhibited TSH-induced up-regulation of RANKL and OPN gene expression by 73 ± 2.4 and 87 ± 1.7%, respectively, but had no effect on ALPL (Fig. 6A). The effect on OPN mRNA expression was supported by measuring secretion of OPN protein into the medium of U2OS-TSHR cell cultures. TSH stimulated a 4.6 ± 0.6-fold increase in OPN secretion that was decreased by 74 ± 10% by knockdown of β-arrestin-1 but not β-arrestin-2 (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

β-Arrestin-1-mediated signaling is essential for up-regulation of osteoblastic markers OPN and RANKL in U2OS-TSHR cells. A) TSH-induced changes of bone-specific gene expression after β-arrestin-1 (βARR1) and β-arrestin-2 (βARR2) knockdown in U2OS-TSHR cells. U2OS-TSHR cells were transfected with 100 nM of nontargeting, βARR1, or βARR2 siRNA. After 24 h, cells were incubated with or without 2 μM TSH for 5 d. Subsequently the cells were lysed and gene expression levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data are from 5 independent experiments with triplicate samples and are presented as means ± se. B) OPN secretion in cell culture supernatants. Cell culture medium collected from 3 experiments in A was used to determine OPN secretion by ELISA. Data are from 3 experiments with duplicate samples and are presented as means ± se.

DISCUSSION

Here we showed that TSH-mediated activation can lead to translocation of both β-arrestin-1 and -2 to TSHR. We confirm that TSH stimulation causes the activation/phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38α and AKT1 but most notably, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of these kinases is in part mediated by β-arrestin-1. Indeed, for TSHR activation by TSH of ERK1/2 and AKT1, β-arrestin-2 inhibits phosphorylation. These findings are similar to those previously noted for the protease-activated receptor type 1-mediated activation of ERK1/2 (13). Therefore, in the TSHR system, β-arrestin-1 is a mediator of activatory signals, whereas β-arrestin-2 mediates inhibitory signals consistent with its previously suggested role in TSHR desensitization of cAMP signaling (26), which we confirmed (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Of particular importance, we showed that stimulation of differentiation of human osteoblast U2OS cell precursors by TSH was mediated in part by β-arrestin-1. The TSH-mediated effect on differentiation was demonstrated by the increases in osteoblast gene markers. Although the effects of TSH to stimulate osteoblast differentiation had been shown previously in mouse cells (7), to our knowledge this is the first such demonstration in a human model cell system. Moreover, the importance of the β-arrestin-1 signaling pathway in these responses to TSH had not been appreciated previously.

TSHR signals via multiple transduction pathways (14) including signaling via Gα proteins from all 4 G-protein subfamilies, Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13 (27), and TSHR activation of some protein kinases has been found to be mediated in part by G proteins. For example, TSHR activation of ERK1/2 was found to be mediated in part by Gα13 (28) and that of AKT by Gαs (29). The idea that activation of these protein kinases by 7TMRs may be mediated by G proteins and β-arrestins is well known (8). Since our data show that knockdown of β-arrestin-1 only partially inhibits protein kinase activation, it is likely that G-protein-mediated pathways account for the remainder of the activation of these kinases.

The potencies for TSH stimulation of the translocation of both β-arrestins to the TSHR were ∼300 nM. This value is 16-fold higher than that for cAMP stimulation but lower than those for negatively cooperative TSH binding and TSH stimulation of phosphoinositide signaling (EC50∼900 nM; refs. 30, 31). We previously provided evidence that these differences in potency were because the binding of a single TSH to TSHR was sufficient for coupling to Gαs with subsequent activation of adenylyl cyclase and production of cAMP, whereas coupling to Gαq/11 leading to activation of phospholipase C and phosphoinositide signaling required binding of 2 TSH molecules to a TSHR homodimer (or oligomer; ref. 30). Although evidence has been presented that several 7TMRs can form heterodimers that can interact with β-arrestins for internalization, a requirement for 7TMR dimerization for binding to β-arrestins remains controversial (32). Nevertheless, to account for the apparent potency of TSH to stimulate β-arrestin translocation, which is intermediate between those for cAMP and phosphoinositide signaling, we suggest that the translocation of β-arrestins to TSHR may occur when one TSH is bound to a TSHR homodimer (or even to a TSHR monomer if one is present) but that translocation is enhanced by the binding of 2 TSH molecules to a TSHR homodimer.

The majority of previous studies and most of our experiments that showed TSHR activation of protein kinases were performed in cells engineered to overexpress TSHRs. The rat thyroid cancer cell line FRTL-5, which endogenously expresses TSHR, was used to show activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and AKT (29) and ERK1/2 by TSH (15). In contrast, TSH was reported previously not to stimulate any mitogen-activated protein kinases in primary cultures of dog and human thyrocytes (33). We observed that activation of ERK1/2, p38α and AKT1 by TSHR occurs in primary cultures of human thyrocytes (34), suggesting that these pathways are important in human thyroid physiology as well.

The effects of TSH stimulation of the β-arrestin-1-mediated, activatory signaling pathway had not been previously delineated in any cell type. Based on the known effects of TSH on thyrocyte differentiation and development (35), it is likely that some aspects of these effects of TSH are mediated by β-arrestin-1. Our results identify a role of β-arrestin-1 in TSH-mediated effects in bone. The small molecule TSHR agonist C2 has been characterized previously as a fully efficacious ligand when compared to TSH in HEK-TSHR cells (24). In primary cultures of human thyrocytes, both TSH and C2 increase mRNA levels for thyroglobulin, thyroperoxidase, sodium iodide symporter, and deiodinase type 2 and deiodinase type 2 enzyme activity. We demonstrated that C2 elevated serum thyroxine and stimulated thyroidal radioiodide uptake in mice after its absorption from the gastrointestinal tract following oral administration (24). In contrast, C2 failed to activate translocation of either β-arrestin to TSH receptor or result in robust phosphorylation of AKT1, p38α, and ERK1/2, despite the fact that it exhibits full efficacy for cAMP signaling in U2OS-TSHR cells also. These findings elucidate the reason why C2, unlike TSH, had no or little effect on osteoblastic gene expression in U2OS-TSHR cells.

Since the β-arrestin-2 signaling pathway has been shown to elicit anabolic effects of PTH1R signaling in bone (18), our data provide additional evidence of the significance of β-arrestin signaling by 7TMRs in bone physiology. We show for the first time that TSH mediates activatory TSHR signaling through β-arrestin-1 and not β-arrestin-2, and that this pathway might play an important role in stimulating differentiation of precursor cells toward an osteoblast phenotype.

It will be important to determine the roles of these pathways in other nonthyroidal cells, in particular in tissues involved in human disease. As it is known that TSH stimulates AKT1 phosphorylation in orbital fibroblasts obtained from patients with Graves' disease (17, 36), it is possible that the β-arrestin pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of Graves' ophthalmopathy. Therefore, future studies will address the physiological role of β-arrestin-1-mediated pathways in thyrocytes and nonthyroidal tissues. We suggest that a biased agonist that activates TSHR-mediated β-arrestin-1 signaling but not cAMP signaling will be a tool to study this pathway and may have clinical use as an osteoprotective agent in bone diseases, such as osteoporosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (1 Z01 DK047044).

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 7TMR

- 7-transmembrane-spanning receptor

- ALPL

- alkaline phosphatase

- ERK1/2

- extracellular-signal regulated kinase 1/2

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- HEK-TSHR

- HEK-EM 293 expressing thyrotropin receptor

- OPN

- osteopontin

- PTH

- parathyroid hormone

- PTH1R

- parathyroid hormone 1 receptor

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand

- TSH

- thyrotropin

- TSHR

- thyrotropin receptor

- U2OS-TSHR

- U2OS expressing thyrotropin receptor

REFERENCES

- 1. Davies T. F., Ando T., Lin R. Y., Tomer Y., Latif R. (2005) Thyrotropin receptor-associated diseases: from adenomata to Graves disease. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1972–1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greenspan S. L., Greenspan F. S. (1999) The effect of thyroid hormone on skeletal integrity. Ann. Intern. Med. 130, 750–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rivkees S. A., Bode H. H., Crawford J. D. (1988) Long-term growth in juvenile acquired hypothyroidism: the failure to achieve normal adult stature. N. Engl. J. Med. 318, 599–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abe E., Marians R. C., Yu W., Wu X. B., Ando T., Li Y., Iqbal J., Eldeiry L., Rajendren G., Blair H. C., Davies T. F., Zaidi M. (2003) TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell 115, 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wojcicka A., Bassett J. H., Williams G. R. (2013) Mechanisms of action of thyroid hormones in the skeleton. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830, 3979–3986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun L., Vukicevic S., Baliram R., Yang G., Sendak R., McPherson J., Zhu L. L., Iqbal J., Latif R., Natrajan A., Arabi A., Yamoah K., Moonga B. S., Gabet Y., Davies T. F., Bab I., Abe E., Sampath K., Zaidi M. (2008) Intermittent recombinant TSH injections prevent ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4289–4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baliram R., Latif R., Berkowitz J., Frid S., Colaianni G., Sun L., Zaidi M., Davies T. F. (2011) Thyroid-stimulating hormone induces a Wnt-dependent, feed-forward loop for osteoblastogenesis in embryonic stem cell cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16277–16282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dewire S. M., Ahn S., Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2007) Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 483–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei H., Ahn S., Shenoy S. K., Karnik S. S., Hunyady L., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) Independent beta-arrestin 2 and G protein-mediated pathways for angiotensin II activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10782–10787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ren X. R., Reiter E., Ahn S., Kim J., Chen W., Lefkowitz R. J. (2005) Different G protein-coupled receptor kinases govern G protein and beta-arrestin-mediated signaling of V2 vasopressin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1448–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shenoy S. K., Drake M. T., Nelson C. D., Houtz D. A., Xiao K., Madabushi S., Reiter E., Premont R. T., Lichtarge O., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gesty-Palmer D., Chen M., Reiter E., Ahn S., Nelson C. D., Wang S., Eckhardt A. E., Cowan C. L., Spurney R. F., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) Distinct beta-arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10856–10864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuo F. T., Lu T. L., Fu H. W. (2006) Opposing effects of beta-arrestin1 and beta-arrestin2 on activation and degradation of Src induced by protease-activated receptor 1. Cell. Signal. 18, 1914–1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Latif R., Morshed S. A., Zaidi M., Davies T. F. (2009) The thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor: impact of thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies on multimerization, cleavage, and signaling. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 38, 319–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iacovelli L., Capobianco L., Salvatore L., Sallese M., D'Ancona G. M., De Blasi A. (2001) Thyrotropin activates mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in FRTL-5 by a cAMP-dependent protein kinase A-independent mechanism. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pomerance M., Abdullah H. B., Kamerji S., Correze C., Blondeau J. P. (2000) Thyroid-stimulating hormone and cyclic AMP activate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade: involvement of protein kinase A, rac1, and reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40539–40546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Turcu A. F., Kumar S., Neumann S., Coenen M., Iyer S., Chiriboga P., Gershengorn M. C., Bahn R. S. (2013) A small molecule antagonist inhibits thyrotropin receptor antibody-induced orbital fibroblast functions involved in the pathogenesis of Graves ophthalmopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, 2153–2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gesty-Palmer D., Flannery P., Yuan L., Corsino L., Spurney R., Lefkowitz R. J., Luttrell L. M. (2009) A beta-arrestin-biased agonist of the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R) promotes bone formation independent of G protein activation. Sci. Transl. Med. 1, 1ra1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bisello A., Chorev M., Rosenblatt M., Monticelli L., Mierke D. F., Ferrari S. L. (2002) Selective ligand-induced stabilization of active and desensitized parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38524–38530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrari S. L., Pierroz D. D., Glatt V., Goddard D. S., Bianchi E. N., Lin F. T., Manen D., Bouxsein M. L. (2005) Bone response to intermittent parathyroid hormone is altered in mice null for {beta}-Arrestin2. Endocrinology 146, 1854–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salvatori L., Caporuscio F., Coroniti G., Starace G., Frati L., Russo M. A., Petrangeli E. (2009) Down-regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor induced by estrogens and phytoestrogens promotes the differentiation of U2OS human osteosarcoma cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 220, 35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neumann S., Kleinau G., Costanzi S., Moore S., Jiang J. K., Raaka B. M., Thomas C. J., Krause G., Gershengorn M. C. (2008) A low-molecular-weight antagonist for the human thyrotropin receptor with therapeutic potential for hyperthyroidism. Endocrinology 149, 5945–5950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaschke H., Neumann S., Moore S., Thomas C. J., Colson A. O., Costanzi S., Kleinau G., Jiang J. K., Paschke R., Raaka B. M., Krause G., Gershengorn M. C. (2006) A low molecular weight agonist signals by binding to the transmembrane domain of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) and luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LHCGR). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9841–9844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neumann S., Huang W., Titus S., Krause G., Kleinau G., Alberobello A. T., Zheng W., Southall N. T., Inglese J., Austin C. P., Celi F. S., Gavrilova O., Thomas C. J., Raaka B. M., Gershengorn M. C. (2009) Small-molecule agonists for the thyrotropin receptor stimulate thyroid function in human thyrocytes and mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12471–12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abe E., Sun L., Mechanick J., Iqbal J., Yamoah K., Baliram R., Arabi A., Moonga B. S., Davies T. F., Zaidi M. (2007) Bone loss in thyroid disease: role of low TSH and high thyroid hormone. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1116, 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frenzel R., Voigt C., Paschke R. (2006) The human thyrotropin receptor is predominantly internalized by beta-arrestin 2. Endocrinology 147, 3114–3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laugwitz K. L., Allgeier A., Offermanns S., Spicher K., Van Sande J., Dumont J. E., Schultz G. (1996) The human thyrotropin receptor: a heptahelical receptor capable of stimulating members of all four G protein families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 116–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buch T. R., Biebermann H., Kalwa H., Pinkenburg O., Hager D., Barth H., Aktories K., Breit A., Gudermann T. (2008) G13-dependent activation of MAPK by thyrotropin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20330–20341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Gregorio G., Coppa A., Cosentino C., Ucci S., Messina S., Nicolussi A., D'Inzeo S., Di Pardo A., Avvedimento E. V., Porcellini A. (2007) The p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K mediates TSH-cAMP-PKA growth and survival signals. Oncogene 26, 2039–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Allen M. D., Neumann S., Gershengorn M. C. (2011) Occupancy of both sites on the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor dimer is necessary for phosphoinositide signaling. FASEB J. 25, 3687–3694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Urizar E., Montanelli L., Loy T., Bonomi M., Swillens S., Gales C., Bouvier M., Smits G., Vassart G., Costagliola S. (2005) Glycoprotein hormone receptors: link between receptor homodimerization and negative cooperativity. EMBO J. 24, 1954–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Milligan G. (2008) A day in the life of a G protein-coupled receptor: the contribution to function of G protein-coupled receptor dimerization. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153(Suppl. 1), S216–S229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vandeput F., Perpete S., Coulonval K., Lamy F., Dumont J. E. (2003) Role of the different mitogen-activated protein kinase subfamilies in the stimulation of dog and human thyroid epithelial cell proliferation by cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate and growth factors. Endocrinology 144, 1341–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neumann S., Eliseeva E., Gershengorn M. (2013) Beta-arrestin 1 mediates TSH receptor signaling. Paper presented at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the American Thyroid Association, A-45 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Postiglione M. P., Parlato R., Rodriguez-Mallon A., Rosica A., Mithbaokar P., Maresca M., Marians R. C., Davies T. F., Zannini M. S., De Felice M., Di Lauro R. (2002) Role of the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor signaling in development and differentiation of the thyroid gland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15462–15467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar S., Nadeem S., Stan M. N., Coenen M., Bahn R. S. (2011) A stimulatory TSH receptor antibody enhances adipogenesis via phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation in orbital preadipocytes from patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 46, 155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.