Abstract

Background

Evidence continues to build for the impact of the marital relationship on health as well as the negative impact of illness on the partner. Targeting both patient and partner may enhance the efficacy of psychosocial or behavioral interventions for chronic illness.

Purpose

The purpose of this report is to present a cross-disease review of the characteristics and findings of studies evaluating couple-oriented interventions for chronic physical illness.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative review of 33 studies and meta-analyses for a subset of 25 studies.

Results

Identified studies focused on cancer, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, HIV, and Type 2 diabetes. Couple interventions had significant effects on patient depressive symptoms (d=0.18, p<0.01, k=20), marital functioning (d=0.17, p<0.01, k=18), and pain (d=0.19, p<0.01, k=14) and were more efficacious than either patient psychosocial intervention or usual care.

Conclusions

Couple-oriented interventions have small effects that may be strengthened by targeting partners’ influence on patient health behaviors and focusing on couples with high illness-related conflict, low partner support, or low overall marital quality. Directions for future research include assessment of outcomes for both patient and partner, comparison of couple interventions to evidence-based patient interventions, and evaluation of mechanisms of change.

Keywords: Couples, Chronic illness, Intervention, Meta-analysis

In their 2001 literature review, Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton [1] described the empirical evidence that negative aspects of marital functioning have indirect influences on health through depression and health habits and direct influences on physiological mechanisms such as cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune function. In the past 10 years evidence has continued to build for the impact of marriage on health and the subsequent implications for individuals living with chronic illness. For example, marital cohesion or quality has been linked with outcomes such as better ambulatory blood pressure in hypertension [2] and better rate of survival over 8 years in congestive heart failure [3], whereas marital strain has been shown to place women with heart disease at greater risk for recurrent coronary events over 5 years [4]. Marital confiding predicted decreased mortality over 8 years in women with Stage II or III breast cancer [5], whereas marital strain was associated with a 46% increase in risk for mortality over 3 years in end-stage renal disease [6]. Other couple characteristics with consistent effects on management of chronic illness include marital conflict, spouse criticism, and lack of congruence between patient and spouse in disease beliefs and expectations [7].

The negative impact of chronic illness on the well spouse also is now well documented in the research literature. Spouses often experience poorer psychological well-being, decreased satisfaction in their relationship with the patient, and burden associated with providing physical assistance [8]. Spouses’ own physical health and self-care may become compromised over time [9–12]. Another unfortunate consequence of an ongoing illness is that spouses’ ability to be supportive may erode over time and their critical or controlling behaviors may increase [13–15]. These findings have been observed across the most common chronic conditions affecting adults including heart disease, chronic pain, rheumatic disease, cancer, and diabetes [16–18].

Awareness of these reciprocal health effects in the marital relationship has led researchers to develop psychosocial or behavioral interventions that include the spouse. Although patient-oriented interventions have been shown to improve psychological well-being and symptom severity for various chronic conditions, the size of observed effects has generally been small [19–22]. Targeting both the patient and spouse may enhance the efficacy of these interventions. In comparison to patient-oriented approaches, couple interventions may have an advantage in long-term maintenance of behavioral changes, and addressing spouses’ concerns may protect against erosion of their support to the patient [23].

The goal of this paper is to review the findings of randomized trials evaluating couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. In contrast to previous reviews [24], we take a cross-disease perspective because the chronic conditions that are leading causes of morbidity and mortality share the common features of being behaviorally driven, influenced by the social environment, and negatively impacting the marital relationship. Therefore, couple-oriented interventions for different conditions share many common features and goals, and this provides the opportunity to evaluate their efficacy as a group. In order to provide a detailed overview of work in this area, we describe characteristics of these studies and summarize statistically significant differences between couple intervention and comparison groups of either patient intervention or usual care. Because it is important to determine the impact of the couple-oriented approach regardless of the statistical significance of between-group differences, we conducted a meta-analysis of three outcomes for which there were an adequate number of effect sizes for aggregation (i.e., patient depressive symptoms, marital functioning, and pain).

Method

Identification of Studies

We searched the literature for published evaluations of interventions that focus on chronic physical illness; are psychologically, socially, or behaviorally oriented; and that involve the active participation of both the patient and spouse/intimate partner (hereafter referred to as “partner”). Studies of populations that were at risk but not yet diagnosed with illness, such as obese individuals and smokers, were excluded. In addition, we excluded studies focused on conditions affecting cognitive functioning (e.g., dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, traumatic brain injury) because family-oriented psychosocial interventions for these populations usually target only the individual identified as caregiver. In order to focus on research that was likely to be methodologically rigorous, we required that studies used a randomized, controlled design in which participants had an equal chance of being assigned to couples intervention or comparison group(s). We conducted computer searches in two databases on the OVID platform: Medline (1950–August 2008) and Psy-cINFO (1967–August 2008). AutoAlerts for searches run in each database through December of 2009 updated the authors on any new publications through that date. The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles, adults (age 19 and older) and English language.

Our strategy was to search for a combination of three main concepts: physical diseases, therapeutics, and dyads. The dyad concept proved to be the most complicated because terms used for this construct vary widely. Ultimately, the search was broadened to include varied terms representing the concept (e.g., couples, significant others, couples therapy) and broad family-related terms (e.g., family, family members, family therapy). The search in PsycINFO closely followed the search strategy used in Medline; however, allowances were made for the database idiosyncrasies such as use of Classification Codes which narrows the search results down to a specific content area in the database (e.g., physical disorders). We also used the ancestry method of examining references in journals and selected articles to identify additional studies not retrieved through database searching.

All couple-oriented RCTs were required to meet four criteria to be included. First, studies had to include the comparison condition of patient-oriented psychosocial intervention, patient usual medical care, or both. Studies with an attention control condition were included. Studies comparing only two or more couple-oriented interventions were excluded because they were not central to the thrust of this paper. Second, we required participation of a partner for every patient as part of the eligibility criteria (i.e., complete dyads). We included this criterion because studies enrolling a subgroup of partners may involve unknown selection effects as a result of not requiring participation from the partner of each patient. Third, because some studies enrolled a mixture of couples and other dyads, we required that at least 75% of the sample consisted of patients and their partner. Fourth, studies had to report psychological, health, or relationship outcomes.

Meta-analytic Procedure

We calculated effect sizes from individual studies using statistics published in the original reports. We computed Cohen’s d values by subtracting the control group mean from the intervention group mean and dividing this value by the pooled sample standard deviation. In cases in which descriptive statistics were not available, we computed d values from inferential statistics using standard formulas. When a study failed to report relevant statistics but indicated that groups did not differ with respect to an outcome, we assumed that there was no difference between the groups (d=0). Because seldom is there no difference at all between two groups, this process represents a very conservative strategy. We computed effect sizes from the first available follow-up because there were not enough studies with a second follow-up to examine the durability of treatment effects. For studies comparing more than one couple intervention with a comparison group, one effect size was calculated by averaging across the effect sizes for each comparison.

The Comprehensive Meta-analysis software program [25] was used to aggregate effect size estimates from individual studies. This program weights each d statistic before aggregation by multiplying its value by the inverse of its variance; this procedure enables larger studies to contribute to effect size estimates to a greater extent than smaller ones. We conducted both fixed effect and random effects meta-analyses. There was little evidence of heterogeneity across studies for the three patient outcomes that we examined, and the findings for the fixed effect and mixed effect analyses were very similar. Therefore, we present findings from the fixed effect models.

We determined whether each aggregate effect size was statistically significant. To examine whether the studies contributing to each aggregate effect size shared a common population value, we computed the heterogeneity statistic H [26]. The H is an easily interpretable measure of heterogeneity within a group of studies and has greater statistical power than the Q test when the number of studies to be included is small. The indirect treatment meta-analysis method was used to evaluate the significance of differences in effect sizes based on the group that was compared to couple intervention (i.e., patient psychosocial intervention or usual care). Based upon a common group across comparisons (i.e., couple-oriented psychosocial/behavioral intervention), this method allows for differences in effect sizes to be evaluated [27].

Results

Characteristics of the Studies

A total of 50 RCTs were identified and 33 of these studies met all criteria for inclusion. These 33 studies were reported in 40 articles. Of the 17 studies that were excluded from our review, three included only a second couple intervention comparison group; six did not require partner participation for every patient; seven did not include a sample of at least 75% partners; and one study reported only satisfaction with the intervention as an outcome.

Table 1 provides a summary of study characteristics. The illness most commonly targeted in this group of studies is cancer (k=13; 39%). Overall, 96.7% of the dyads in these samples were couples. Patients and partners in these studies were in their mid-50s on average. Approximately half of these studies (46%) compared couple-oriented intervention to patient usual medical care only. Consistent with the broader intervention literature, most of the couple interventions were multi-component in nature and often included education of patient and partner regarding chronic illness and its management, enhancement of communication or support within couples, and cognitive-behavioral training. Borrowing from Baucom and colleagues’ [28] system for characterizing family-oriented interventions, most of the couple interventions can be classified as disorder-specific in that they targeted illness-specific issues of both patient and partner, either together or with patient and partner separately in several cases [29–31]. In many cases, these interventions addressed the role of relationship functioning in illness management. In contrast, only three studies used a partner-assisted type of approach as described by Baucom and colleagues, where the partner’s role was to help the patient meet cognitive or behavioral objectives of the intervention (i.e., pain management, problem-solving, or relaxation) [32–34].

Table 1.

Study characteristics (K=33)

| No. of studies | |

|---|---|

| Illness populations | |

| Cardiovascular disease or hypertension | 6 |

| Prostate cancer | 5 |

| Mixed cancer | 4 |

| Breast cancer | 4 |

| Osteoarthritis | 4 |

| Chronic pain | 4 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 |

| HIV | 2 |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 1 |

| Average Age | 54.7 years (patients); 56.1 years (spouses) |

| Group(s) Compared to Couple-Oriented Intervention | |

| Patient usual medical care or attention control |

15 |

| Patient psychosocial/behavioral intervention |

8 |

| Both of the above | 10 |

| Couple-oriented intervention contenta Education |

16 |

| Partner support/communication enhancement |

11 |

| Relationship counseling/enhancement | 10 |

| Cognitive-behavioral/coping skills training | 9 |

| Behavioral therapies/Problem-solving therapy |

9 |

| Exercise/weight loss/health behavior change |

3 |

| Patient outcomes assessed (k=33) | |

| Psychological functioning | 30 |

| Physical health | 23 |

| Marital functioning | 18 |

| Health behaviors | 4 |

| Medication adherence | 1 |

| Spouse outcomes assessed (k=19) | |

| Psychological functioning | 16 |

| Marital functioning | 11 |

| Physical health | 4 |

| Health behaviors | 1 |

Total is greater than 33 because many studies tested multi-component couple interventions

The number of sessions that were included in couple interventions ranged from 3 to 20. Reflecting a recent trend in intervention research, eight couple interventions were implemented either partially or entirely over the telephone [29–31, 35–40]. A total of 14 studies tested a couple-oriented intervention in a group format (i.e., two or more couples received the intervention together).

Assessment of patient outcomes focused primarily on psychological functioning (e.g., depressive symptoms, coping, self-efficacy for managing illness); health indicators such as illness-specific symptoms, sexual function, pain, and general physical functioning; and marital functioning (e.g., satisfaction, partner support).) Physiological outcomes were examined in four studies and included viral load and CD4 cell count in HIV [41], glycosylated hemoglobin and fasting blood sugar in Type 2 diabetes [42], erythrocyte sedimentation rate in rheumatoid arthritis [43], and blood pressure in hypertension [34]. Health behaviors were examined in four studies and included adherence to antiretroviral medication [41] as well as diet or exercise [42, 44, 45].

For partners, pre-post data were collected in 19 out of 33 studies (58%). Assessment of partner outcomes focused primarily on psychological functioning (e.g., depressive symptoms, self-efficacy for helping patient, caregiving stress) and marital functioning (e.g., satisfaction, quality of communication). Partners’ physical health was examined in four studies and included perceived health, weight, and fasting blood sugar. Health behaviors were examined in only one study, which assessed change in partner diet and exercise [42].

Study Findings

Table 2 describes each study according to sample, study groups, timing of follow-up, and significant between-group differences for patient and partner.

Table 2.

Summary of RCTs evaluating couple-oriented interventions (K=33)

| First author (year) | Sample | Groups and follow-Up | Between-group differences for patients | Between-group differences for partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badger, 2007 | 98 breast cancer patients and partners (77% spouses) |

|

No significant differences between groups | No significant differences between groups |

| Patients and partners treated separately | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 1 month | ||||

| Baucom, 2009 | 14 breast cancer patients and spouses |

|

Between-group differences not examined. Between-group effect sizes favored Group 2 at post-intervention and 12 months for psychological functioning, marital functioning, and medical symptoms. |

Between-group differences not examined. Between-group effect sizes favored Group 2 at post-intervention and 12 months for psychological functioning and marital functioning. |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 12 months | ||||

| Campbell, 2007 | 30 African- American prostate cancer patients and partners |

|

2> 1 for bowel symptoms | No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention | ||||

| Canada, 2005 | 51 prostate cancer patients and wives |

|

No significant differences between groups | No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 3 months, 6 months | ||||

| Christensen, 1983 | 20 post-mastectomy patients and husbands |

|

No significant differences between groups | No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention | ||||

| Fife, 2008 | 87 HIV patients and partners |

|

2> 1 for hostility, guilt, constructed meaning, number of coping strategies, total coping strategies, and active coping at post-intervention |

Partner outcomes were assessed but included only as covariates in patient analyses. |

| 2> 1 for total negative affect, hostility, guilt, joviality, and constructed meaning at 3 months | ||||

| Patient and partner treated separately | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 3 months | ||||

| Fridlund, 1991 | 116 post-myocardial in farction (MI) patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for exercise test, pain, exertion, leisure, exercise, sexual intercourse, breathlessness, fatigue, and fitness at 6 months |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 2> 1 for reinfarction, satisfaction with partner situation, physical exercise, sexual intercourse, breathlessness, chest pain, and fitness at 12 months | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 6 months |

||||

| Giesler, 2005 | 99 prostate cancer patients and partners (96% spouses) |

|

2> 1 for sexual function at 4 months | No outcomes were reported. |

| 2> 1 for sexual limitation at 7 months and 12 months |

||||

| Follow-up: 4 months, 7 months, and 12 months | 2>1 for cancer worry at 12 months | |||

| 2> 1 for urinary bother in patients with low depressive symptoms at 4 months and 7 months |

||||

| 2> 1 for physical role function in patients with high depressive symptoms at 12 months |

||||

| Gortner, 1988; Gilliss, 1990 |

67 cardiac surgery patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for self-efficacy in lifting at 3 months, and 1>2 for tolerating emotional distress at 3 months |

No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: 3 months and 6 months post-discharge |

||||

| Hartford, 2002 | 131 coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients and spouses |

|

No significant differences between groups | No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: 3 days, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks post-discharge |

||||

| Keefe, 2005 | 56 advanced cancer patients and partners (most were spouses) |

|

No significant differences between groups | 2>1 for self-efficacy in helping patient to control pain and other symptoms |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention | ||||

| Keefe, 2004 | 84 knee osteoarthritis patients and spouses |

|

4>3 for aerobic fitness; leg extension; and leg flexion |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 4>2 for coping attempts; pain control and rational thinking; and self-efficacy |

||||

| 4> 1 for aerobic fitness, leg extension, leg flexion, bicep curl, coping attempts, pain control and rational thinking, and self-efficacy |

||||

| 3>2 for coping attempts | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention | 2>3 for aerobic fitness, leg extension, leg flexion, and bicep curl |

|||

| 3>1 for coping attempts and self-efficacy | ||||

| 2> 1 for leg extension, leg flexion, and bicep curl. |

||||

| Keefe, 1996, 1999 | 87 knee osteoarthritis patients and spouses |

|

At post-intervention: | No significant differences between groups. |

| 3>2 for pain, pain behavior, psychological disability, coping attempts, self-efficacy, and marital adjustment | ||||

| 1>2 for coping attempts, marital adjustment, and self-efficacy | ||||

| At 6 months: | ||||

| 3>2 for pain control and rational thinking, and pain self-efficacy | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months | 1>3 for marital adjustment | |||

| 1>2 for coping attempts | ||||

| At 12 months: | ||||

| 3>2 for self-efficacy | ||||

| 1>2 for physical disability | ||||

| Kole-Snijders, 1999 |

174 chronic low-back pain patients and significant others (most were spouses) |

|

At post-intervention: | No outcomes were reported. |

| 4, 3>1 for three composite factors: motoric behavior (pain behavior and activity tolerance); coping control (pain coping, pain control); and negative affect (catastrophizing, pain, depression, fear) | ||||

| 4>3 for coping control | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months, 12 months. Group format. | ||||

| Experimental groups 1, 3, and 4 compared at post-intervention. All follow-up time points used to compare groups 2, 3, and 4. |

||||

| Kuijer, 2004 | 48 mixed cancer patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for overinvestment/underbenefit, underinvestment/overbenefit, relationship quality, and depressive symptoms at po st-intervention |

2>1 for overinvestment/underbenefit, underinvestment/overbenefit, and relationship quality at post-intervention |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 3 months | Effects were generally maintained at 3 months. | Effects were generally maintained at 3 months |

||

| Lenz, 2000 | 38 coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients and family members (78% spouses) |

|

No significant differences between groups | No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: 3–4 days post-surgery; 2, 4, 6, and 12 weeks post-discharge | ||||

| Manne, 2005, 2007 |

238 early stage breast cancer patients and husbands |

|

At 6 months: 2> 1 for depressive symptoms |

No outcomes were reported. |

| Follow-up: post-intervention and 6 months | 2> 1 for loss of behavioral and emotional control in women with unsupportive partners and women with more physical impairment |

|||

| 2> 1 for well-being in women with unsupportive partners | ||||

| 2> 1 for depressive symptoms in patients with high emotional processing; high emotional expression; and a high level of acceptance | ||||

| Martire, 2003 | 24 women with hip or knee osteoarthritis and husbands |

|

2> 1 for arthritis self-efficacy at post intervention |

No significant differences between groups |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention | ||||

| Martire, 2007, 2008 |

193 hip or knee osteoarthritis patients and spouses |

|

2>3 for pain and general arthritis severity at 6 months |

3>2 for perceived stress at post-intervention |

| 3>2 for punishing spousal responses at post-intervention, and for supportive spousal responses at 6 months |

3>2 for caregiver mastery at post-intervention in spouses with high marital satisfaction |

|||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 6 months | At 6 months, 3>2 for stress in female spouses and for depressive symptoms in spouses with high marital satisfaction |

|||

| Mishel, 2002 | 240 prostate cancer patients and partners (84% spouses) |

|

2> 1 for cognitive refraining and problem solving at 4 months |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 3>1 for number of symptoms at 4 months for Caucasian men |

||||

| 2> 1 for number of symptoms at 7 months for African-American men |

||||

| Follow-up: 4 months and 7 months. Analyses focused on baseline to 4 months and 4 months to 7 months |

||||

| Moore, 1985 | 43 chronic pain patients and spouses |

|

3, 2> 1 for pain, somatization, and spouse report of patient psychosocial adjustment at post-intervention. |

No outcomes were reported. |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 3 months. Comparisons with Group 1 conducted only with post-intervention data. |

||||

| Nezu, 2003 | 133 mixed cancer patients and family members (95% spouses) |

|

At post-intervention, 3>1 for negative mood, depression, cancer-related problems, psychiatric symptoms, family reported interpersonal/social behavior, global psychological distress, and problem-solving ability |

No outcomes were reported. |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months |

At post-intervention, 2>1 for negative mood, depression, cancer-related problems, psychiatric symptoms, family reported interpersonal/social behavior, global psychological distress, and problem-solving ability |

|||

| Only Groups 2 and 3 were compared at 6 and 12 months. |

||||

| At 6 and 12 months, 3>2 for negative mood and psychiatric symptoms |

||||

| Northouse, 2007 | 235 prostate cancer patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for uncertainty and communication with spouse at 4 months |

2>1 for mental health, patients’ cancer specific quality of life, negative appraisal of caregiving, uncertainty, hopelessness, self-efficacy, communication, general distress from patient symptoms, and distress from patient urinary incontinence at 4 months |

| Follow-up: 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months |

2>1 for physical health, uncertainty communication, and distress from patient urinary incontinence at 8 months |

|||

| 2>1 for physical health, self-efficacy, communication, and active coping at 12 months |

||||

| Radojevic, 1992 | 59 rheumatoid arthritis patients and friends/ family members (81% spouses) |

|

2, 3>1, 4 for reduced joint swelling and number of swollen joints at post intervention and 2 months |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 3>2, 1, 4 for reduced joint swelling and number of swollen joints at post-intervention | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 2 months | ||||

| Remien, 2005 | 215 HIV-positive patients and partners |

|

2> 1 for prescribed medication doses taken at 2 weeks |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 2> 1 for prescribed medication doses taken within time window at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months | ||||

| Follow-up: 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months | ||||

| Riemsma, 2003 | 218 rheumatoid arthritis patients and family members (88% spouses) |

|

2>3 for fatigue and self-efficacy re: other symptoms at 12 months |

No outcomes were reported. |

| 1>3 for fatigue and self-efficacy re: other symptoms at 12 months | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months |

2> 1 for self-efficacy re: other symptoms at 12 months |

|||

| Saarijarvi, 1991a 1991b,1992 |

59 chronic low back pain patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for marital communication at 12 months |

No significant differences between groups. |

| Follow-up: 12 months and 5 years | 2> 1 for depression, anxiety, hostility, and obsessiveness at 5 years |

|||

| Scott, 2004 | 90 women with early stage breast or gynecological cancer and husbands |

|

3>2, 1 for couple coping, communication at post-intervention and 6 months |

3>2, 1 for couple coping, communication at post-intervention and 6 months |

| 3>2, 1 for personal coping effort at 12 months |

3>2, 1 for personal coping effort at 12 months |

|||

| 3>2, 1 for psychological distress at post-intervention | ||||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months and 12 months |

3>2, 1 and 1>2 for avoidance at post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months | |||

| 3>2, 1 for positive sexual self-schema, sexual intimacy, and partner acceptance at post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months | ||||

| Thompson, 1990a & b |

60 male post-myocardial infarction patients and wives |

|

At 3 days, 2> 1 for anxiety re: health and the future |

At 3 days, 2>1 for anxiety re: sexual activity, relations with patient, ability of patient to work, and complications for patient |

| Follow-up: 5 days and 1,3, and 6 months since MI. Anxiety subscales also assessed at 1, 2, and 3 days after MI. |

At 5 days, 2> 1 for depressive symptoms; general anxiety symptoms; and anxiety re: health, ability to work, complications, leisure activity; and the future |

At 5 days, 2>1 for general anxiety symptoms and all specific anxiety scales |

||

| At 1 month, 2>1 for depressive symptoms; general anxiety symptoms; and anxiety re: another MI, complications, leisure activity, and the future |

At 1 month, 2> 1 for general anxiety symptoms and all specific anxiety scales except for relations with patient |

|||

| At 3 months, 2> 1 for depressive symptoms; general anxiety symptoms; and anxiety re: ability to work, another MI, relations with spouse, and leisure activity |

At 3 months, 2>1 for general anxiety symptoms and all specific anxiety scales except for relations with patient |

|||

| At 6 months, 2>1 for general anxiety and anxiety re: health, ability to work, another MI, relations with spouse, and leisure activity |

At 6 months, 2>1 for general anxiety symptoms and all specific anxiety scales except for complications for patient |

|||

| Turner, 1990 | 57 chronic low back pain patients and spouses |

|

3>2 for pain, pain behavior, and spouse report of sickness impact at post intervention | No outcomes were reported. |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months, and 12 months |

||||

| van Lankveld, 2004 |

60 rheumatoid arthritis patients and spouses |

|

No significant differences between groups | Outcomes not described. Authors reported that spouses did not show improvement in any of the outcomes assessed. |

| Follow-up: Post-intervention and 6 months |

||||

| Wadden, 1983 | 31 hypertension patients and spouses |

|

2> 1 for number of in-home practice sessions of relaxation therapy and minutes of in-home practice sessions, at 1 month |

No outcomes were reported. |

| Follow-up: 1 month and 5 months | ||||

| Wing, 1991 | 49 obese Type 2 diabetes patients and overweight spouses |

|

1>2 for decreased calorie intake, and for weight loss in males, at post intervention |

2>1 for weight loss at post intervention and 1 year, and for eating behaviors at post intervention |

| 2> 1 for weight loss in females at post intervention |

1>2 for patient support at 1 year | |||

| Follow-up: Post-intervention, 12 months |

Effects on Patients

A total of 32 studies examined between-group differences whereas one did not [46]. Of these studies, 18 (56%) found consistent differences favoring couple intervention over usual care or patient psychosocial intervention [31, 33–35, 39–41, 44, 47–57]. All types of patient outcomes and chronic illnesses were represented in this group, with the exception of the Type 2 diabetes study which showed mixed effects according to gender (described below). A total of 7 studies (22%) found no differences between groups [29, 30, 32, 38, 43, 58, 59].

Of the remaining seven studies, six showed mixed effects according to outcome variable, patient gender, and type of couple intervention. Cardiac surgery patients in a couple intervention had greater increased efficacy but less tolerance for emotional distress than those receiving a patient-oriented intervention [36, 37]. Osteoarthritis patients in a couple intervention reported more improvement in spouse supportiveness but less improvement in pain and disability than those receiving a patient-oriented intervention [60, 61]. Wing and colleagues found that women with Type 2 diabetes showed greater weight loss from a couple intervention whereas men with Type 2 diabetes showed greater weight loss from patient intervention [42].

Couple-oriented cognitive-behavioral interventions for arthritis patients were more beneficial than cognitive-behavioral patient interventions, but couple-oriented education interventions did not show this advantage [62–64]. Not surprisingly, patient-oriented exercise was more beneficial than a couple-oriented cognitive-behavioral intervention for outcomes that were fitness related [65]. Finally, Riemsma and colleagues reported negative effects of a couple-oriented education intervention on patient fatigue and self-efficacy [45],

Effects on Partners

Between-group differences were examined in 17 of the 33 studies. Of these studies, six (35%) consistently found differences favoring couple intervention over usual care or patient psychosocial intervention [32, 39, 40, 50, 60, 66] (see Table 2). Specifically, couple interventions enhanced partners’ psychological functioning (i.e., self-efficacy stress, mastery, anxiety) and perceptions of marital quality and coping as a couple. Cancer, hypertension, and osteoarthritis were represented in this group of studies. A total of ten studies (59%) found no differences between groups [30, 35–38, 43, 53, 57–59, 62, 63, 67]. The remaining study on obese spouses of adults with Type 2 diabetes found an advantage of couple intervention over patient psychosocial intervention in terms of weight loss and eating behaviors but an advantage of patient psychosocial intervention for enhanced partner support [42],

Many of these studies suffered from methodological problems that could be corrected in future research. First, studies rarely reported findings from both intent-to-treat and completers analyses. That is, it was often unclear if analyses focused on all participants who were randomly assigned to couple intervention regardless of whether they received it, or focused only on participants who received the couple intervention. Findings from completers analyses are valuable but may obscure selection effects and make it difficult to interpret findings from an RCT. Second, little information was provided regarding number of sessions attended by patients and partners. Incomplete implementation is a particular concern in psychosocial and behavioral interventions and less than full participation by partners may underestimate the effects of an intervention designed for couples.

Another methodological limitation is that many of the studies that did not find between-group differences for patient or partner were statistically underpowered to do so (i.e., less than approximately 50 participants per group for the detection of medium-sized effects). However, five of these studies did find significant time effects of couple intervention indicating improvement over time for patients [43], partners [35], or both [38, 58, 59]. Because meta-analysis summarizes the average impact of an intervention regardless of the statistical significance of between-group differences, we conducted this type of analysis in addition to our qualitative review.

Meta-analytic Findings

Our meta-analysis focused on outcomes for which there were an adequate number of effect sizes for aggregation. We set this number at k≥10 for either type of comparison (i.e., couple intervention versus patient psychosocial intervention or usual care) because there is limited statistical power for meta-analysis and bias in the H heterogeneity statistic with fewer than eight to ten studies [26, 68]. Applying this criterion, the following three patient outcomes qualified for meta-analysis: depressive symptoms, marital functioning, and pain. Of the 33 studies identified for our review, a total of 25 were subjected to meta-analysis. The number of studies included in the analyses for depressive symptoms, marital functioning, and pain were 20, 18, and 14, respectively.

We conducted separate analyses according to whether the study compared couple intervention to patient psychosocial intervention or usual care. The study by Nezu and colleagues [33] was not included in the analysis of patient depressive symptoms for the comparison of couple intervention and usual care because the effect size was an extreme outlier (d=4.36). Results were then pooled to determine the overall effect size for studies with either type of comparison group. Because some studies included both comparison groups, there was overlap in these analyses (k= 4 for marital functioning and k=5 for depressive symptoms and pain). For those studies that included both comparison groups, one averaged effect size was submitted in the overall analyses for each outcome.

Depressive symptoms were most often assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale [69] or the Brief Symptom Inventory [70]. Marital functioning was assessed with global measures of relationship quality such as the Dyadic Adjustment Scale [71] or specific measures of partner emotional or instrumental support [72, 73]. Current or usual pain was assessed with visual analogue scales or other established measures such as the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales [74]. For studies involving more than one measure of an outcome, one effect size was calculated by averaging across the effect sizes for each measure.

As shown in Table 3, a statistically significant effect of couple intervention was present in the overall analyses for all three patient outcomes. That is, couple interventions were successful in reducing patients’ depressive symptoms, enhancing marital functioning, and reducing pain. All effect sizes were small in magnitude. An H value of 1 indicates homogeneity of intervention effects; therefore, the values in Table 3 show that that there was little heterogeneity in the effect sizes of this group of studies. The indirect meta-analysis estimate compares the magnitude of effect sizes across the two comparison groups. In all cases the 95% confidence interval overlapped 0 and this indicates that there were no differences in effect sizes as a function of comparison group.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of patient outcomes

| Outcome and comparison | k | Couple-oriented intervention (n) |

Comparison group (n) |

Effect size (d) |

95% CI | HW | Indirect estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||

| Overalla | 20 | 596 | 622 | 0.18** | 0.07–0.27 | 1.10 | |

| COI versus usual care | 15 | 461 | 500 | 0.15* | 0.02–0.27 | 1.13 | 0.04 (−0.26–0.18) |

| COI versus POI | 10 | 269 | 259 | 0.19* | 0.00–0.37 | 0.91 | |

| Marital functioning | |||||||

| Overall a | 18 | 579 | 598 | 0.17** | 0.06–0.27 | 0.95 | |

| COI versus usual care | 11 | 381 | 407 | 0.17* | 0.03–0.31 | 0.76 | 0.01 (−0.20–0.22) |

| COI versus POI | 11 | 312 | 308 | 0.16* | 0.00–0.32 | 1.15 | |

| Pain | |||||||

| Overall a | 14 | 448 | 444 | 0.19** | 0.08–0.30 | 0.92 | |

| COI versus usual care | 11 | 384 | 360 | 0.20** | 0.05–0.34 | 1.07 | 0.02 (−0.21–0.25) |

| COI versus POI | 8 | 260 | 243 | 0.18* | 0.00–0.35 | 0.73 |

COI couple-oriented psychosocial/behavioral intervention, POI patient-oriented psychosocial/behavioral intervention, HW heterogeneity of effect sizes within studies

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

K and n figures combined for each comparison group are more than the total for overall analyses because some studies included both comparison groups

Discussion

In this review, we found that couple-oriented interventions targeted the most common and deadly illnesses in adulthood (e.g., cancer and heart disease) as well as the most disabling (e.g., arthritis) [75]. These illnesses require substantial behavioral changes, self-management, and treatment decision making, all of which are likely to be strongly influenced by the attitudes and behaviors of the spouse. Only one of the studies identified for our review targeted Type 2 diabetes despite its prevalence and the rising incidence of obesity. Clearly more research is warranted with this population.

Findings from our meta-analysis suggest that couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness hold promise. There were small improvements in patient depressive symptoms, marital functioning, and pain. The lack of heterogeneity within studies indicates that the interventions included in our review had similar effects despite varying illness populations and intervention content and suggests that it is useful to take a cross-disease perspective on dyadic interventions. Along these lines, it may be valuable to develop standard couple-oriented intervention content that can be applied to multiple chronic conditions, similar to the approach taken in the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program that was developed for heart disease, lung disease, stroke, and arthritis [76]. It would also be highly useful for researchers to develop a battery of common outcome measures to be used across illness populations in order to better synthesize this literature going forward [77].

The aggregate effects that we found in our meta-analyses were small in magnitude, raising the question of how the impact of couple-oriented interventions could be strengthened. One possible strategy for enhancing their impact is to place greater emphasis on targeting spouse communications and actions that influence patient health behaviors. There is a high rate of concordance between partners’ health-enhancing and health-compromising behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking, dietary habits, body mass index, and level of physical activity) [78–80]. These findings, as well as recent work linking autonomy support and health-related social control with disease management, could inform future couple interventions. Autonomy support includes understanding for an individual’s situation and provision of choices for making health behavior changes [81]. Social control involves attempts to regulate or influence the behaviors of another person through actions, affective responses, and corrective feedback [82]. Based on recent findings in these areas of research, future couple-oriented interventions may be useful in teaching spouses how to support patients’ need to make their own choices, as well as positive tactics for encouraging healthy behaviors such as persuasion, modeling, and reinforcement.

Relatedly, the literature on couple-oriented interventions for at-risk groups (e.g., obese individuals, smokers) that received much attention in the 1970s and 1980s is worth revisiting. Behavioral weight-loss interventions that involve a support partner have been successful and could be applied to ill populations [83, 84]. And although couple-oriented interventions for smoking cessation have had disappointing effects, this has been attributed in part to their failure in achieving substantial change in partner support [85, 86].

A second strategy for strengthening couple interventions is to directly target partners’ well-being and worries about the future. Findings from the family caregiving intervention literature suggest that addressing such issues is necessary for reducing emotional contagion in couples and garnering partners’ ongoing support [8]. Specifically, it is important to provide spouses with information about the illness and possible treatment options; validate their experiences as a provider of support; teach them various stress management skills; and help them to plan for the future. The value of such content seems especially important in consideration of the fact that the partner often suffers from the same chronic condition as the patient due to shared lifestyles and exposure to environmental stressors, as was reported in studies included in our review [47, 60].

Couple-oriented interventions may also have a greater impact on couples with a high level of conflict related to the illness or a low level of partner support for symptom management and behavioral change. Manne and colleagues [52] found that the positive effects of a couple-oriented intervention on breast cancer patients’ depressive symptoms were stronger for patients with husbands who were unsupportive (e.g., critical of how the patient handled cancer and uncomfortable talking about the cancer with her). None of the studies that we reviewed included eligibility criteria related to spouse support or distress, possibly reducing the size of intervention effects.

Overall marital quality may also be an important moderator of treatment effects. It has been argued that marital quality may serve as an interpretive backdrop that alters patients’ appraisal of spousal behaviors and therefore the impact of those behaviors on health [1]. For example, well-intentioned but unhelpful behaviors of the spouse may be perceived positively by patients in happy marriages and negatively by those with dissatisfying marriages. By extension, individuals with low overall marital quality may experience greater benefits from a couple-oriented intervention than those with high marital quality. In future research it will be important to address the extent to which marital problems that existed prior to a chronic illness can be addressed within a couple-oriented intervention.

Approximately half of the studies that we reviewed reported that patients receiving a couple-oriented intervention showed greater improvements than those receiving usual care or patient psychosocial intervention. Of the studies that examined benefits for the partner, approximately one third found that couple-oriented interventions led to improvements in their psychological and marital functioning. Although it is difficult to draw strong conclusions from this relatively small group of studies with different types of intervention content, cognitive-behavioral strategies such as coping skills training for couples seemed to be the most consistently successful.

Baucom and colleagues [28] noted that dyadic family interventions differ in the extent to which they focus on interpersonal issues. Some interventions address communication or relationship issues between patient and family member that might contribute to the maintenance or exacerbation of an illness, whereas other interventions take the approach of enlisting the family member’s help in changing the patient’s behaviors. Most of the couple interventions that we reviewed targeted illness-specific issues of both patient and partner whereas few took the approach of enlisting the partner as a coach in the patient’s psychosocial or behavioral treatment. Although less intensive from a dyadic perspective, the partner-assisted approach might make more sense for couples who are managing the illness well. For these couples, relationship distress would not be a target of intervention. However, information about the illness and tactics for making lifestyle changes may serve to enhance the sense that each partner is working together to manage the illness, and may help to maintain spouse support over the long term. Taking a less intensively dyadic approach with some couples may enhance retention of participants, engagement in the intervention, and generalizability of study findings to a broader population of couples.

A potential trade-off that was salient in this group of studies is that of a group format intervention versus treating individual couples. Treating couples together in a group rather than separately is more economical but limits the ability to discuss relationship issues in depth if necessary or to address the varying needs of couples. As noted by other researchers [87], the most successful interventions may be those that are tailored or adapted to the needs of individual couples.

Improvements in methodological quality and attention to published guidelines for reporting clinical trials [88–90] are much needed in this area of research. The most important and feasible issues to address are use of intention-to-treat analyses, reporting of patient adherence to treatment (e.g., number of sessions attended), and power analyses. Many studies had inadequate statistical power to detect the small intervention effects that are common in psychosocial intervention research, including the additional power that is often needed to detect differences between two active interventions [91].

Limitations of our Review

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of this review. First, our meta-analysis did not include unpublished studies. Our focus was on published, peer-reviewed studies because we thought that they would be most methodologically rigorous and thus yield the strongest conclusions in regard to efficacy. Second, our analyses did not take into account that population effect sizes may be overestimated owing to a tendency for null findings to not appear in the published literature. We did not make statistical corrections for publication bias, because these corrections are often overly conservative when a small number of studies are aggregated, as was true for our outcomes. Because of these decisions, our meta-analytic findings should be considered preliminary and in need of corroboration.

Directions for Future Research

We would like to highlight four design and measurement issues for researchers to consider in future research testing couple-oriented interventions. Our first recommendation is that investigators explicitly reference the models and observational research that led them to use a couple-oriented approach and the specific aspects of the marital relationship that were targeted. We found that the majority of studies failed to describe how theory was used in the development of intervention materials. Other researchers also have noted that couple interventions are rarely conceptually driven nor do they often identify specific targets for change [7]. Although specific theoretical or conceptual models are rarely tested in couple-oriented intervention research, researchers sometimes cite the biopsychosocial model of health and illness, marital and family systems frameworks, or stress and coping models that are modified for the caregiving or care-receiving context.

Second, evaluation of change in marital or spouse factors is critical for establishing that effects of the intervention on primary outcomes occurred through these mechanisms. Although many studies addressed relationship issues, only half (55%) examined change in any indicators of marital functioning. We return to these issues of theory and mechanisms in our description of an additive model for couple-oriented interventions.

A third recommendation is to assess outcomes for the partner as well as for the patient. Failure to assess effects on both patient and partner provides an incomplete picture regarding efficacy. Lack of improvement for the patient may be explained by negative (but unexamined) effects on the partner. For example, a couple-oriented intervention that fails to address the partner’s needs or concerns may lead to more negative marital interactions or lack of support for the patient’s behavioral changes. This phenomenon reflects the cyclical nature of marital interactions in daily life, in that a partner’s affective and behavioral reactions to the patient serve to influence that patient’s health and well-being, which in turn drives future reactions. Assessing the partner’s perspective on change in marital interactions is especially important because individuals do not always recognize having received support even when they benefitted from it [92]. Other research teams have also argued for examining the appraisal and coping strategies of both patient and partner in relation to each other [14, 93–95].

Assessment of both patient and partner paves the way for dyadic analysis as an alternative to focusing separately on patient and partner changes, as exemplified in two of the studies that we reviewed [40, 50], and may include dyadic growth curve modeling [96] or dual change score modeling [97]. In addition, studies that collect daily diary data from both patient and partner (an increasingly common approach) and use multilevel analyses for time-series data can indicate the stronger directional influence in associations between patient and partner functioning. Finally, a dyadic approach to assessment will allow for better cost-benefit analyses as this field progresses. That is, it will be important to weigh the benefits of couple-oriented intervention for both patient and partner against the costs associated with targeting both individuals.

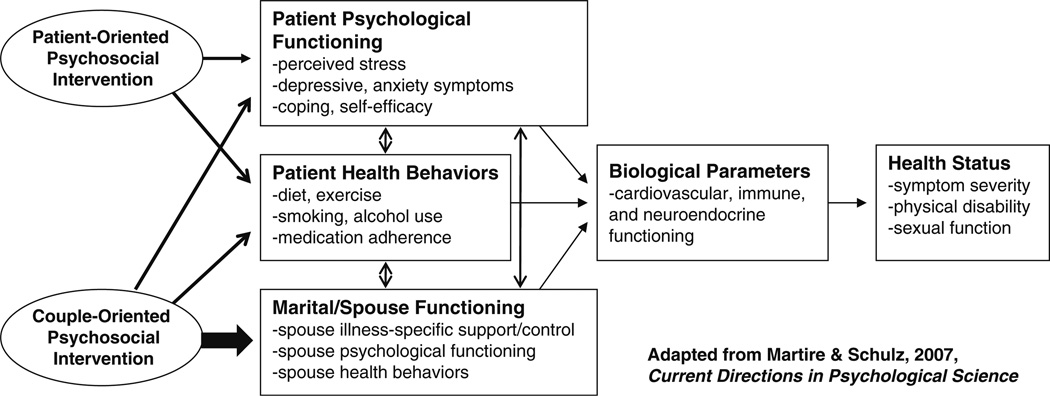

A fourth recommendation for future research is to compare couple- and patient-oriented approaches to intervention. This design feature is especially useful to the field of behavioral medicine due to great interest in the most efficacious psychosocial or behavioral treatments for chronic illness, yet it was included in only half of the studies that we reviewed. This is also a superior study design for examining the unique effects of marriage on health, as depicted in Fig. 1. This model depicts the influence of factors within three broad and interrelated domains (psychological, behavioral, and marital/partner) on patient health. Consistent with other conceptual frameworks [1, 98, 99], this model specifies that marital functioning affects patient health directly through physiological parameters and indirectly through changes in patient psychological functioning and health behaviors. To the marital domain, we add partners’ own psychological functioning and health behaviors because of their linkages with patient functioning in these same areas [80, 100].

Figure 1.

This heuristic model illustrates the potential added benefit to patient health of couple-oriented intervention as compared to patient-oriented intervention, due to its effects on an additional domain of functioning (i.e., marital/partner). Examples of specific constructs are provided for each domain of functioning. Adapted from Martire and Schulz [23]

As depicted in the figure, couple-oriented interventions are likely to have benefits beyond a traditional patient-oriented approach due to their effects on marital/partner functioning (indicated by the largest arrow) in addition to their effects on patients’ psychological functioning or health behaviors. This research question could be tested using an additive/constructive treatment design where a couple component is added to a standard patient intervention [101]. Interventions that successfully modify marital or partner functioning and then measure change in patient outcomes would enhance our understanding of the role of marriage in health. Moreover, these interventions could provide critical information regarding the unique and shared pathways leading to recovery from different health conditions. In contrast to the comparison of couple intervention to usual care, the type of design depicted in Fig. 1 can help to confirm that greater improvements in patient health resulting from couple intervention are due at least in part to change in marital/partner functioning and not only due to change in patient psychological functioning or health behaviors.

Conclusions

The vast majority of adults living with a chronic illness are partnered, and this close relationship plays a critical role in illness management. In turn, chronic illness takes a toll on the well partner. Targeting both patient and partner in a psychosocial or behavioral intervention is an approach that merits evaluation. Few randomized trials have been designed to compare couple- and patient-oriented approaches, making it difficult to evaluate the “relative” efficacy of a couples approach. Our review indicates that couple-oriented interventions are promising but efforts are needed to strengthen future studies both conceptually and methodologically. The added health care costs of targeting the partner may be small when considering the potential benefits to both members of the dyad and subsequent gains for the larger family unit.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grants R01 AG026010, R01 NR009573, and R01 DK060586.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Lynn M. Martire, Email: lmm51@psu.edu, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, The Pennsylvania State University, 118 Henderson Building North, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Richard Schulz, Department of Psychiatry and University Center for Social and Urban Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Vicki S. Helgeson, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Brent J. Small, School of Aging Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Ester M. Saghafi, Health Sciences Library System, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analyses.

- 1.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker B, Helmers K, O’Kelly B, et al. Marital cohesion and ambulatory blood pressure in early hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC. Effect of marital quality on eight-year survival of patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orth-Gomer K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, et al. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: The Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. JAMA. 2000;284:3008–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weihs KL, Enright TM, Simmens SJ. Close relationships and emotional processing predict decreased mortality in women with breast cancer: Preliminary evidence. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:117–124. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815c25cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Dyadic relationship conflict, gender, and mortality in urban hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1518–1525. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1181518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher L. Research on the family and chronic disease among adults: Major trends and directions. Families, Systems & Health. 2006;24:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martire LM, Schulz R. Caregiving and care-receiving in later life: Recent evidence for health effects and promising intervention approaches. In: Baum A, Revenson T, Singer J, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. New York: Taylor & Francis; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredman L, Bertrand RM, Martire LM, Hochberg M, Harris EL. Leisure-time exercise and overall physical activity in older women caregivers and non-caregivers from the Caregiver-SOF Study. Prev Med. 2006;43:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: A prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz R, Beach SR, Hebert RS, et al. Spousal suffering and partner's depression and cardiovascular disease: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:246–254. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318198775b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolger N, Foster M, Vinokur AD, Ng R. Close relationships and adjustment to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:283–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revenson TA. Social support and marital coping with chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens MAP, Martire LM, Cremeans-Smith JK, Druley JA, Wojno WC. Older women with osteoarthritis and their caregiving husbands: Effects of patients’ pain and pain expression. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Kanter RA. Depression and anxiety among partners of European-American and Latino patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1564–1570. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, Kovatchev B, Julian D, Clarke W. The psychosocial impact of severe hypoglycemic episodes on spouses of patients with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1543–1546. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmaling KB, Sher TG. The psychology of couples and illness: Theory, research, and practice. 1st ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dixon KE, Keefe FJ, Scipio CD, Perri LM, Abernethy AP. Psychological interventions for arthritis pain management in adults: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2007;26:241–250. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees K, Bennett P, West R, Davey SG, Ebrahim S. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub2. CD002902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott-Sheldon LA, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder RL. Stress management interventions for HIV+adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychol. 2008;27:129–139. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Vadaparampil ST, Small BJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007;26:660–667. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martire LM, Schulz R. Involving family in psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cochrane BB, Lewis FM. Partner’s adjustment to breast cancer: A critical analysis of intervention studies. Health Psychol. 2005;24:327–332. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-analysis Version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, Meek P, Lopez AM. Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nursing Research. 2007;56:44–53. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartford K, Wong C, Zakaria D. Randomized controlled trial of a telephone intervention by nurses to provide information and support to patients and their partners after elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Effects of anxiety. Heart & Lung. 2002;31:199–206. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.122942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: Nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94:1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, et al. Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: A preliminary study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: Assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1036–1048. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wadden TA. Predicting treatment response to relaxation therapy for essential hypertension. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1989;171:683–689. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African-American prostate cnacer survivors and their intimate partners. Cancer. 2007;109:414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilliss CL, Neuhaus JM, Hauck WW. Improving family functioning after cardiac surgery: A randomized trial. Heart & Lung. 1990;19:648–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gortner SR, Gilliss CL, Shinn JA, et al. Improving recovery following cardiac surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1988;13:649–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenz ER, Perkins S. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients and their family member caregivers: Outcomes of a family-focused staged psychoeducational intervention. Applied Nursing Research. 2000;13:142–150. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2000.7655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1122–1135. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, et al. Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2005;19:807–814. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168975.44219.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wing RR, Marcus MD, Epstein LH, Jawad A. A “family-based” approach to the treatment of obese Type II diabetic patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:156–162. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Lankveld W, van Helmond T, Naring G, de Rooij DJ, van den Hoogen F. Partner participation in cognitive-behavioral self-management group treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:1738–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fridlund B, Hogstedt B, Lidell E, Larsson PA. Recovery after myocardial infarction: Effects of a caring rehabilitation programme. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 1991;5:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1991.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riemsma RP, Taal E, Rasker J. Group education for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their partners. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;49:556–566. doi: 10.1002/art.11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fife BL, Scott LL, Fineberg NS, Zwickl BE. Promoting adaptive coping by persons with HIV disease: Evaluation of a Patient/ Partner Intervention Model. Journal of The Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104:752–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kole-Snijders AMJ, Vlaeyen JWS, Goossens MEJB, et al. Chronic low-back pain: What does cognitive coping skills training add to operant behavioral treatment? Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:931–944. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuijer RG, Buunk BP, De Jong GM, Ybema JF, Sanderman R. Effects of a brief intervention program for patients with cancer and their partners on feelings of inequity, relationship quality and psychological distress. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:321–334. doi: 10.1002/pon.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G. Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2007;26:735–744. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, et al. Feasibility of a dyadic intervention for management of osteoarthritis: A pilot study with older patients and their spousal caregivers. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7:53–60. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore JE, Chaney EF. Outpatient group treatment of chronic pain: Effects of spouse involvement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:326–334. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson DR, Meddis R. A prospective evaluation of in-hospital counselling for first time myocardial infarction men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1990;34:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90080-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner JA, Clancy S, McQuade KJ, Cardenas DD. Effectiveness of behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: A component analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:573–579. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saarijarvi S. A controlled study of couple therapy in chronic low back pain patients: Effects on marital satisfaction, psychological distress and health attitudes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1991;35:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christensen DN. Postmastectomy couple counseling: An outcome study of a structured treatment protocol. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1983;9:266–275. doi: 10.1080/00926238308410913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, Rudy TE, Starz TW. Couple-oriented education and support intervention: Effects on individuals with osteoarthritis and their spouses. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2007;52:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, Rudy TE, Starz TW. Couple-oriented education and support intervention for osteoarthritis: Effects on spouses’ support and responses to patient pain. Families, Systems & Health. 2008;26:185–195. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.26.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, et al. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. Arthritis Care and Research. 1996;9:279–291. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199608)9:4<279::aid-anr1790090413>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, et al. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of knee pain in osteoarthritis: Long-term followup results. Arthritis Care and Research. 1999;12:101–111. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)12:2<101::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Radojevic V, Nicassio PM, Weisman MH. Behavioral intervention with and without family support for rheumatoid arthritis. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom D, et al. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: A randomized controlled study. Pain. 2004;110:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson DR, Meddis R. Wives’ responses to counselling early after myocardial infarction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1990;34:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90081-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saarijarvi S, Alanen E, Rytokoski, Hyyppa MT. Couple therapy improves mental well-being in chronic low back pain patients: A controlled, five year follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1992;36:651–656. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hedges LV, Pigott TD. The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:203–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz SD, Gibofsky A. Social support as a double-edged sword: The relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:807–813. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LEAIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Statistics NCfH: Health, United States. With Special Feature on Medical Technology. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2009. p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39:1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Prog-ress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Franks MM, Pienta AM, Wray LA. It takes two: Marriage and smoking cessation in the middle years. J Aging Health. 2002;14:336–354. doi: 10.1177/08964302014003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pettee KK, Brach JS, Kriska AM, et al. Influence of marital status on physical activity levels among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:541–546. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000191346.95244.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams GC, Lynch MF, McGregor HA, et al. Validation of the "Important Other" Climate Questionnaire: Assessing autonomy support for health-related change. Families, Systems & Health. 2006;24:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lewis MA, Butterfield RM. Antecedents and reactions to health-related social control. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31:416–427. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Black DR, Gleser LJ, Kooyers KJ. A meta-analytic evaluation of couples weight-loss programs. Health Psychol. 1990;9:330–347. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, Mermelstein R, et al. Social support interventions for smoking cessation. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Marshaling social support: Formats, processes, and effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 211–240. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Park EW, Schultz JK, Tudiver FG, Campbell C, Becker LA. Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004;(Issue 3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002928.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]