SUMMARY

Cardiac tissue undergoes renewal with low rates. Although resident stem cell populations have been identified to support cardiomyocyte turnover, the source of the cardiac stem cells and their niche remain elusive. Using Cre/Lox-based cell lineage tracing strategies, we discovered that labeling of endothelial cells in the adult heart yields progeny with cardiac stem cell characteristics that express Gata4 and Sca1. Endothelial-derived cardiac progenitor cells were localized in the arterial coronary walls with quiescent and proliferative cells in the media and adventitia layers, respectively. Within myocardium, we identified labeled cardiomyocytes organized in clusters of single-cell origin. Pulse-chase experiments showed that generation of individual clusters was rapid, but confined to specific regions of the heart, primarily in the right anterior and left posterior ventricular walls and the junctions between the two ventricles. Our data demonstrate that endothelial cells are an intrinsic component of the cardiac renewal process.

INTRODUCTION

Classically, the heart was thought of as a post-mitotic organ without intrinsic mechanisms to replace cardiomyocytes (CMs). However, recent studies documented moderate annual CM renewal rates, averaging from 0.4% to 1% (Bergmann et al., 2009; Murry and Lee, 2009). The origins of cardiac tissue renewal mechanisms have been actively pursued, leading to the identification of several distinct cardiac cell types with stem cell characteristics proposed to contribute to maintenance of the adult mammalian heart (Boudoulas and Hatzopoulos, 2009). One such population consists of cells that form cardiospheres in suspension and differentiate to CMs, endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (Messina et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007). Cardiac stem cells (CSCs) also include c-Kit expressing cells, which generate CMs, ECs and SMCs after injury (Beltrami et al., 2003; Rota et al., 2008; Ellison et al., 2013). A different CSC type consists of Side Population (SP) cells (Hierlihy et al., 2002; Martin et al., 2004; Mouquet et al., 2005). The potential of SP cells to differentiate to cardiac cells is higher in the subgroup that expresses Stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1) (Pfister et al., 2005). Sca1+ cells independently isolated from adult cardiac tissue express early regulators of cardiac differentiation such as Gata4 and, when stimulated, Nkx2.5 and sarcomeric proteins (Oh et al., 2003). Sca1+ cells home to infarcted myocardium, yielding CMs around the injury area and improving cardiac function (Oh et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006). Recent transcriptional profiling suggests c-Kit+ cells represent a less differentiated phenotype, whereas SP and Sca1+ cells are more committed to the cardiac lineage (Dey et al., 2013).

Adult organs, including the brain, gut, bone marrow and hair follicles, harbor stem cells in specialized niches, allowing for spatial and temporal regulation of the renewal process (Li and Clevers, 2010; Fuentealba et al., 2012). The niche supports quiescent stem cells that, upon stimulation, give rise to transient amplifying progenitors which differentiate to mature, tissue-specific cell types. In the heart, by contrast, little is known about the origins of CSCs or the structural organization of the CSC niche.

We recently showed that after acute ischemic injury in the adult heart, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) produces bipotent cells that generate both endothelial cells and myofibroblasts during scar formation (Aisagbonhi et al., 2011). Other groups have documented the ability of adult ECs to generate multipotent stem-like cells via EndMT in the bone, demonstrating a degree of EC plasticity and ability to differentiate to alternative cell types (Medici et al., 2010). Based on these findings, we hypothesized ECs may also contribute to the maintenance of cardiac tissue during homeostasis. Using constitutive and inducible fate mapping strategies to track cells expressing endothelial genes in the adult mouse heart, we discovered ECs generate cells with CSC characteristics. EC-derived cells were organized in a radial manner within coronary arteries, with quiescent and proliferative cells residing in the media and adventitia layers, respectively. Distal to the coronary niche, we identified labeled CMs organized in clusters of single cell origin. EC pulse-chase experiments demonstrated CM renewal was rapid but spatially restricted. Our data reveal that cells with EC properties are part of the intrinsic cardiac renewal program and that coronary arteries constitute a structural component of the cardiac stem cell niche.

RESULTS

Endothelial fate mapping labels cardiomyocytes in the adult heart

To investigate the potential role of the endothelium for maintenance of the normal, uninjured adult heart, we analyzed cell fate in the hearts of 3-5 month-old Tie1-Cre-LacZ or Tie1-Cre-YFP mice, generated by crossing Tie1-Cre mice to ROSA-β-galactosidase (LacZ) or ROSA-Enhanced Yellow Fluorescence Protein (YFP) reporter mice, respectively (Gustafsson et al., 2001; Soriano, 1999; Srinivas et al., 2001) (Figure 1A). In double transgenic animals, the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter constitutively drives reporter gene expression in ECs and their progeny.

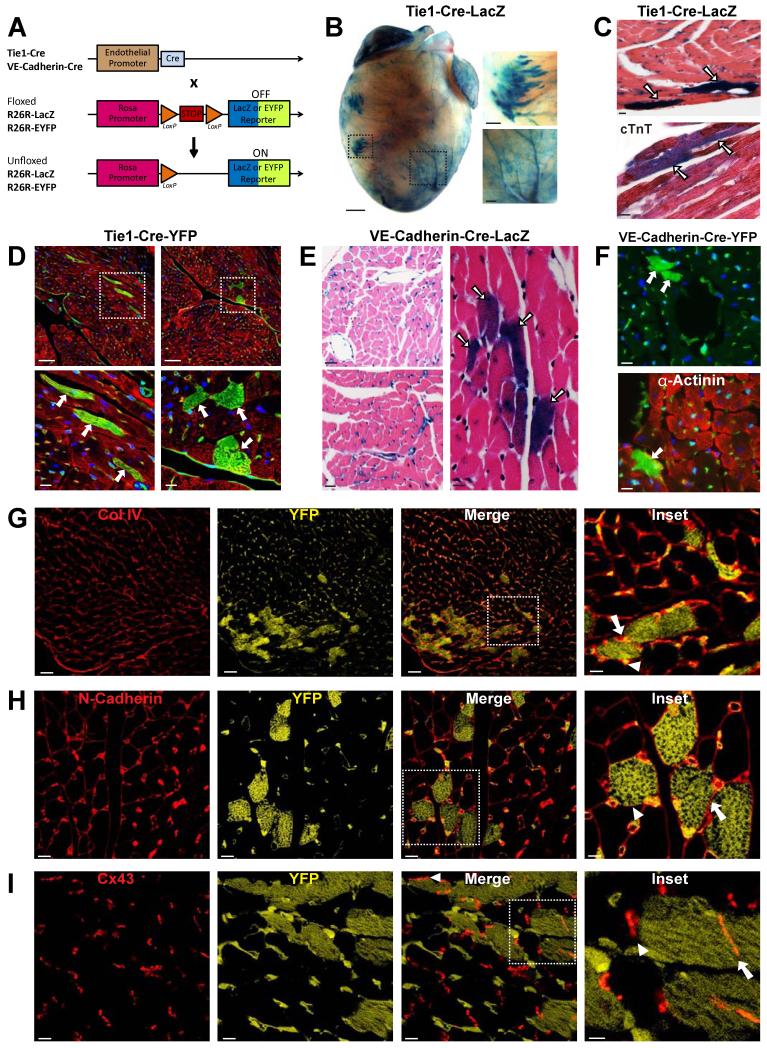

Figure 1. Lineage tracing of endothelial cell fate leads to cardiomyocyte labeling in the adult heart.

(A) Schematic drawing of gene loci used for EC lineage tracing and fate mapping. (B) Whole mount X-gal staining of hearts from 3 month old Tie1-Cre-LacZ mice shows EC labeling and clusters of non-ECs in the ventricles. Right panels represent boxed areas showing a cluster of labeled non-ECs (upper panel) and ECs (lower panel). Scale bars 1mm in original image, 250μm in insets. (C) Upper panel: Histological analysis of X-gal-stained cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-LacZ mice shows CM staining (arrows). Lower panel: labeled non-ECs co-stain for cardiac Troponin T (cTnT; arrows). Scale bars 10μm. (D) IF analysis of cardiac tissue from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice stained for YFP (green) shows ECs and CMs, the latter co-stained for α-Actinin (red). YFP+ CMs (arrows) are shown sectioned longitudinally (left) and transversely (right). DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear counter-staining. Lower panels depict boxed areas to showcase sarcomeric structures in YFP+ CMs. Scale bars 50μm (top panels), 10μm (bottom panels). (E) Histological analysis of X-gal-stained cardiac tissue from VE-Cadherin-Cre-LacZ mice shows staining of ECs (left panels). A labeled CM cluster is highlighted in the right image. Scale bars 25μm (left panels), 10μm (right panel). (F) IF analysis of cardiac tissue from VE-Cadherin-Cre-YFP mice co-stained for YFP (top and bottom, green) and α-Actinin (bottom; red). DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear counter-staining. Scale bars 10μm. (G-I) IF analysis of cardiac tissue from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice indicating YFP (yellow) and basal membrane Collagen IV (G; Col IV, red), membrane cell adhesion protein N-cadherin (H; red) and gap junction protein Connexin 43 in intercalated discs (I; Cx43, red). YFP antibody marks both ECs and EC-derived CMs. Higher magnification inserts are shown in the right panels. Arrows indicate adjacent YFP+/YFP+ CMs, arrowheads indicate adjacent YFP+/YFP- CMs. Scale bars 30μm (G) and 10μm (H,I) in original images, and 10μm (G) and 5μm (H,I) in insets. See also Figure S1.

Tie1-Cre-LacZ hearts were stained with X-gal to visualize β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity and thus Tie1+ cells and their derivatives. In addition to marking ECs as expected, we detected labeled cells of non-endothelial appearance that were organized in clusters (Figure 1B). Histological analysis showed the β-gal+ clusters were CMs, based on morphology and co-staining for cardiac Troponin T (Figure 1C). To exclude that CM staining was due to aberrant β-gal activity in CMs, we stained cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice with antibodies recognizing YFP and the CM marker α-Actinin. Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis showed robust EC staining, but also revealed the presence of YFP+ CMs with proper sarcomeric structures (Figure 1D). EC-derived CMs in sections appeared in clusters, in agreement with the pattern observed in whole-mount images.

To eliminate the possibility that CM staining was due to ectopic Tie1 promoter activity in cardiac cells, we used mice expressing β-gal directly under the Tie1 promoter to mark ECs, but not their progeny (Korhonen et al., 1995). Histological analysis at 2 days, 2 weeks, 1 month, and 2 months of age detected exclusive EC labeling, without β-gal+ CMs (Figure S1). These results indicate the labeled CMs observed in Tie1-Cre-LacZ and Tie1-Cre-YFP hearts are progeny of Tie-1+ cells and not due to ectopic Tie1 expression in CMs.

To further confirm that ECs give rise to CMs, we used an independent mouse line with endothelial-specific Cre expression under the control of the Vascular Endothelial (VE)-Cadherin gene transcription regulatory elements (Alva et al., 2006) (Figure 1A). The VE-Cadherin promoter-based labeling produced comparable results to the Tie1-Cre-LacZ or Tie1-Cre-YFP mice. Specifically, histological sections obtained from 3-5 month-old VE-Cadherin-Cre crossed to ROSA-LacZ (VE-Cadherin-Cre-LacZ) or ROSA-YFP (VE-Cadherin-Cre-YFP) hearts showed labeling of both ECs and CMs (Figure 1E,F).

IF analysis showed EC-derived, YFP+ CMs were surrounded by normal basal membrane (Collagen IV staining), properly expressed cell-adhesion membrane molecules (N-Cadherin), and formed gap junctions (Connexin 43) among themselves, as well as non-EC derived CMs, suggesting they are functionally integrated with neighboring YFP(−) CMs (Figure 1G-I). Taken together, our results show that in adult mice fate mapping using endothelial genetic labeling yields cells with functional and structural properties of CMs.

Endothelial-derived myocytes first appear 2 weeks after birth

During development, mesodermal progenitor cells, which differentiate to ECs, CMs, and SMCs, also express the endothelial-specific gene Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (Vegfr2; Kattman et al., 2006). This raised the possibility that the labeled CM clusters in the adult heart are derived from early embryonic cells with endothelial characteristics. To distinguish whether EC-derived CMs are of embryonic or adult origin, we used End-SCL-CreERT mice with inducible Cre recombinase expression under the control of the 5′ endothelial-specific enhancer of the Stem Cell Leukemia (SCL) gene (Göthert et al., 2004). End-SCL-CreERT mice were crossed to the ROSA-LacZ or ROSA-YFP reporter lines to generate End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ or End-SCL-CreERT-YFP mice, respectively. These double transgenic mice allow for specific labeling of mature ECs after tamoxifen induction of Cre-recombinase activity.

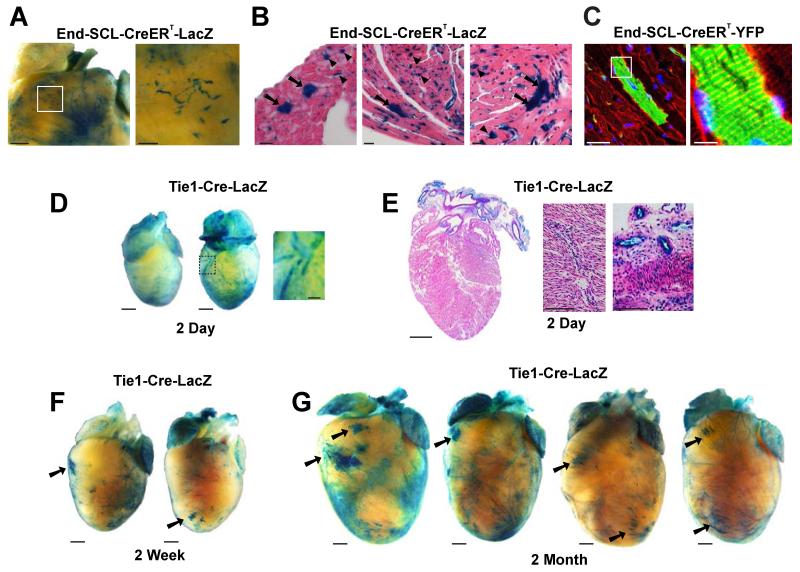

End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ and End-SCL-CreERT-YFP adult mice were continuously fed a diet containing 0.8% tamoxifen to tag and lineage trace ECs. Whole-mount staining with X-gal and histological analysis of End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ hearts after 6 weeks of tamoxifen diet showed EC as well as CM labeling (Figure 2A,B), similar to the constitutively active endothelial-specific Cre models described in Figure 1. Labeling of CMs, which co-stained for sarcomeric α-Actinin, was also observed after 12 weeks on tamoxifen (Figure 2C). Of note, we did not detect CM labeling, and found extremely rare EC labeling (<1%), in control End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mice without tamoxifen administration, indicating tight regulation of inducible Cre recombinase activity. No labeled cells were present in ROSA-STOP-LacZ mice on tamoxifen (Figure S2).

Figure 2. Endothelial-derived cardiomyocytes appear in the adult heart.

(A,B) Images of X-gal stained hearts from 5 month old End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mice, fed tamoxifen chow for 6 weeks to induce Cre recombinase in adult ECs and their progeny. Whole mount staining in A shows EC and CM labeling. Scale bar 1mm in original image, 250μm in inset. Histological sections in B depict labeled CMs (arrows) and ECs (representative arrowheads). Scale bars 20μm. (C) Labeling of cardiac ECs and CMs in End-SCL-CreERT-YFP double transgenic line after 12 weeks of tamoxifen diet. Sections stained for YFP (green) and α-Actinin (red). Right panel: magnification of boxed area highlights sarcomeric structures in YFP+ CM. Scale bars 10μm (left), 50 μm (right). (D,E) Whole mount images (D) and sections (E) of X-gal stained neonatal hearts from 2 day old Tie1-Cre-LacZ mice shows EC, but not CM labeling. Scale bars 1mm in original images, 250μM in magnified areas. (F,G) X-gal staining of hearts from weanling (2 weeks) and young adult (2 months) mice show EC-derived CM clusters appear around 2 weeks of age. Scale bars 1mm. See also Figure S2.

To test whether the observed CM staining is due to ectopic activity of the Tie1 or Endothelial-SCL promoter/enhancer elements in non-ECs, we stained cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP and End-SCL-CreERT-YFP mice with antibodies recognizing Cre protein. IF analysis showed that Cre expression is restricted to ECs, supporting an endothelial origin of labeled CMs (Figure S2). We confirmed the endothelial specificity of Tie1 expression by co-staining cardiac sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice for Tie1 and α-Actinin. We did not detect co-labeling of Tie1 in YFP+ or YFP- CMs, showing that CMs do not express Tie1 (Figure S2). Collectively, these results indicate the observed labeling is not due to 1) leaky activity of the inducible Cre fusion protein, 2) expression of β-gal and YFP without Cre activity, or 3) aberrant Tie1 or Cre expression in CMs.

To further exclude the possibility that EC-derived CMs are marked during development, we isolated and X-gal stained hearts from neonatal and young Tie1-Cre-LacZ mice. Staining of hearts from perinatal day P2, weanling (P14) and young adult (2 months) mice indicated that while cardiac vasculature was labeled at each time point (Figure 2D-G; also Figure S1), CM clusters first appeared within the postnatal heart by 2 weeks of age (Figure 2F,G).

In brief, we used three independent, constitutive (Tie1, VE-Cadherin) or inducible (End-SCL) endothelial-specific promoters, with two independent reporters (LacZ, YFP) that all showed similar labeling of ECs and CM clusters. Thus, our data support the idea that a subset of CMs in the adult mouse heart is postnatally derived from ECs.

Clusters of endothelial-derived cardiomyocytes originate from single cells

The clustering of EC-derived CMs suggested they were clonally related. To test this model, we crossed the Tie1-Cre line to the ROSA-Confetti multi-fluorescent reporter to generate Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice. The Confetti line carries four distinct fluorescent protein genes (red, yellow, nuclear green and membrane-bound cyan) in the ROSA locus (Snippert et al., 2010). The fluorescent protein coding sequences are organized in tandem among alternating LoxP sites in a way that recombination of the ROSA-Confetti allele leads to stochastic expression of RFP, YFP, nuclear GFP (nGFP) or membrane CFP (mCFP). The construct is designed such that random recombination activates only one of the fluorescent protein genes, allowing stochastic labeling of each targeted cell and its descendants with a single color (Figure 3A). As a result, this fate mapping strategy can distinguish whether cells in a cluster are clonally related (i.e., generated from a single, labeled progenitor cell), or if each cell in a cluster has been independently derived. In the first case, the entire cluster should have CMs of one color; if the latter is true, individual clusters should consist of cells expressing different colors (Greif et al., 2012).

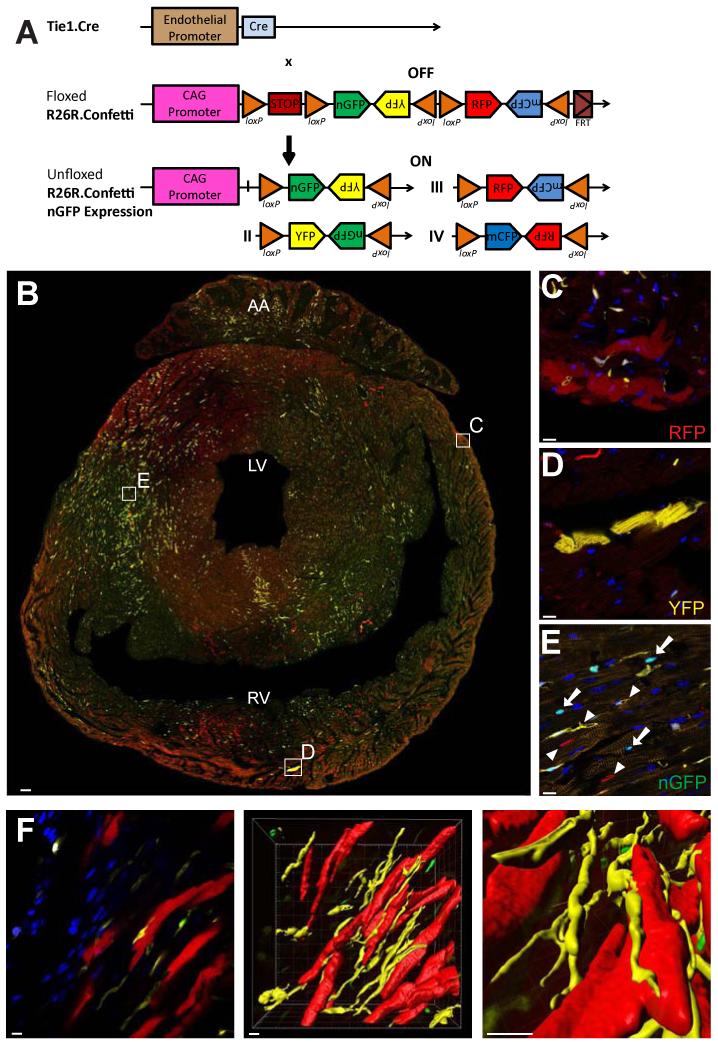

Figure 3. Endothelial-derived cardiomyocytes are of clonal origin.

(A) Schematic drawing of the ROSA-Confetti reporter gene locus. (B-E) Epifluorescence analysis for RFP, YFP and nGFP expression in transverse cardiac sections from adult Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice depicts ECs and CMs expressing RFP, YFP and nGFP. CM clusters marked in boxed areas in B are magnified in C-E. Individual CMs in each cluster express the same fluorescent protein. Scale bars 100μm in B, 10μm in C-E. (F) 3-D reconstruction of a representative CM cluster (each CM expressing RFP), and adjacent ECs expressing YFP. Scale bars 10μm. See also Figure S3.

Epifluorescence examination of cardiac sections from adult Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice detected ECs expressing RFP, YFP and nGFP in equal proportions (Figure S3; in our hands, expression of mCFP in cardiac sections was too weak to reliably detect; therefore we focused further analysis on RFP, YFP, and nGFP). Among labeled CMs, each individual cluster was marked by expression of the same single fluorescent protein (Figure 3B-E). To calculate the probability (P) that each cluster would randomly consist of CMs expressing the same fluorescent protein without being derived from a single cell, we recorded the size and color of CM clusters with ≥3 cells in sections of three independent Tie1-Cre-Confetti mouse hearts (Figure S3). The probability that the observed labeling patterns in this analyzed set of CMs are due to random recombination events is P<10−36, indicating that labeled CMs in each cluster are not independently derived, but originate from a single cell.

Using 3-D reconstruction images, we documented that in many instances individual CM clusters were marked by a different fluorescent color than neighboring microvasculature, suggesting CM labeling was not due to fusion with ECs (Figure 3F). Furthermore, CMs in the same cluster were not always contiguous but often interspersed with unlabeled CMs, a pattern also observed in other organs that might be indicative of tissue repair in the adult versus de novo development in the embryo (Kopinke et al., 2011; Bowman et al., 2013). Collectively, the staining patterns in Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice indicate that each labeled CM cluster has originated from a single parental cell expressing EC markers. It is also possible that rare, proliferating CMs transiently express endothelial markers, and thus become labeled before expansion to form clusters.

Cardiac myocyte progeny of endothelial cells are regionally restricted

Whole-mount heart staining indicated EC-derived CM clusters were localized in specific areas (Figures 1B & 2F,G). To determine overall distribution patterns throughout right and left ventricles, we systematically mapped the location of CM progeny following EC lineage tracing. Complete sets of serial transverse cardiac tissue sections from five Tie1-Cre-YFP mice were analyzed using confocal microscopy. The results revealed clusters of labeled CMs were present in both left and right ventricles, most frequently around coronary blood vessels in subepicardial regions (Figure 4A,B). The locations of clusters containing ≥4 YFP+ CMs were placed in a diagram of four heart planes from base to apex. We found YFP+ CM clusters were primarily localized in three regions of the heart: the anterior free wall of the right ventricle; the junction areas between right and left ventricles and adjacent septum; and the lateral free posterior wall of the left ventricle (Figure 4C).

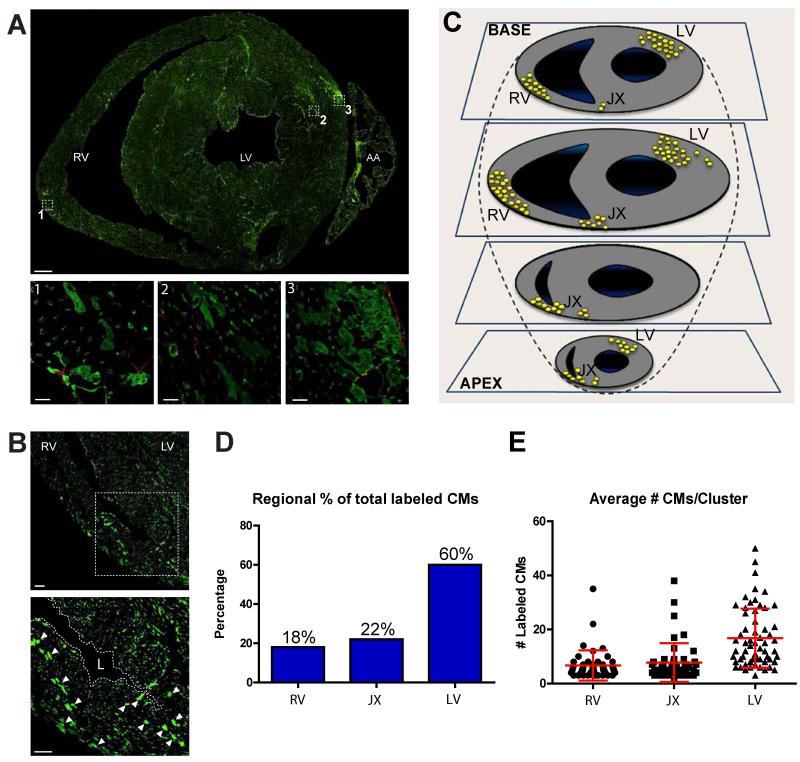

Figure 4. Endothelial-derived cardiomyocytes are localized to three specific heart areas.

(A) Transverse cardiac section from adult Tie1-Cre-YFP mice stained for YFP reveals EC-derived YFP+ CMs are found in both left and right ventricles, most frequently in perivascular (insets 1,2,3) and subepicardial (insets 1,3) areas. Scale bars 500μm in original image, 10μM in insets. (B) Clusters of CMs are also localized at the junction of the left and right ventricles and adjacent septum. Scale bars 50μm. (C) Schematic drawing depicting the location of all clusters ≥4 YFP+ CMs identified in serial sections of 5 Tie1-Cre-YFP mice. (D) Quantification of CM cluster locations shows 60% are present in the left ventricle and the remaining 40% in the right ventricle and junction areas. (E) Quantification of CM number in each cluster shows clusters in the left ventricle are on average double in size compared to clusters in the right ventricle. Abbreviations: AA, atrial appendage; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; JX, junction; L, lumen.

Each cluster consisted of up to 50 CMs. 60% of the observed clusters were in the left ventricle with the remaining 40% equally distributed in the right ventricle and junction areas. Furthermore, left ventricle clusters consisted on average of twice as many cells per cluster than those in the right ventricle (Figure 4D,E). Taking into account the number of clusters in each heart and the number of cells per cluster, we calculated the total number of YFP+ CMs represent ca. 0.3% of the approximately 8 million CMs in the mouse heart (Adler et al., 1996; /). These data indicate that in both ventricles, cardiogenic endothelium seeds specific cardiac areas, representing a relatively small fraction of the CM population.

Pulse labeling of endothelial cells leads to rapid long-term cardiomyocyte labeling

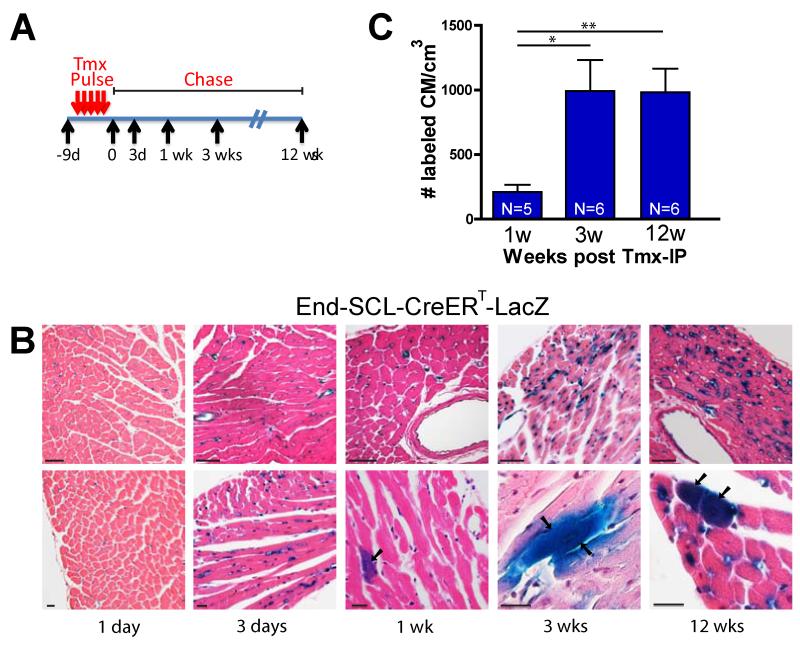

To test whether ECs are the originating cells, or represent an intermediate, transient step in the cardiogenic process, we pulsed-chased ECs using the inducible End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mouse described above. Adult mice were given a series of closely spaced tamoxifen injections (‘pulse’) and hearts were isolated at various time-points after the final injection (‘chase’) (Figure 5A). Hearts were then stained with X-gal to visualize labeled CMs in transverse sections. Analysis of cardiac tissue sections immediately (i.e., 1 day after the end of the pulse), and 3-days later showed exclusive labeling of ECs, whereas labeled CMs appeared one week after the pulse and persisted up to 12 weeks, the last time point examined (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Pulse-chase labeling of endothelial cells leads to rapid long-term labeling of cardiomyocyte progeny.

(A) Schematic drawing of the pulse-labeling experimental design. (B) Histological analysis of hearts stained with X-gal and counter-stained with H&E to visualize ECs and labeled CMs in transverse sections at indicated time points. After a 1- and 3-day chase, labeling of only cardiac ECs was observed, whereas labeled CMs appeared by one week after the pulse and persisted at 3 months. Arrows indicate X-gal+ CMs. Scale bars 50μm (upper), 20μm (lower panels). (C) Quantification of CM numbers at different chase time points shows maximum CM labeling within 3 weeks which remains constant thereafter. N indicates number of mice used for analysis. Values reported as mean +/− S.D. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. See also Figure S4.

The number of labeled CMs per volume of cardiac tissue was quantified for each of the time-points. The data indicate labeled CMs appeared in low numbers one week after the pulse, increased over a period of 3 weeks, and remained relatively constant at least up to 12 weeks (Figure 5C). These results suggest cells labeled by EC-specific Cre expression represent an originating cell rather than a transient subpopulation in the CM generation process, since in the latter case CM numbers would decline after a single pulse. Alternatively, it is likely EC-derived CMs have long life spans beyond the examined 12-week period. In either case, the duration required to achieve maximum CM labeling after the pulse suggests the process is efficient and reaches a steady state within approximately 3 weeks.

The SCL gene, as well as Tie1 and VE-Cadherin, are also expressed in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), raising the possibility that labeled CMs are of bone marrow origin. One advantage of the SCL 5′ enhancer is that it is not expressed in adult HSCs (Göthert et al., 2004), which suggests labeled CMs are derived from ECs and not bone marrow cells. To directly test whether HSCs contribute CMs in the adult heart, we used a method independent of lineage tracing. Specifically, we analyzed cardiac tissues from mice transplanted with fluorescently tagged bone marrow cells (Figure S4). IF analysis showed bone marrow derived cells present in the adult heart were primarily F4/80+ macrophages and FSP-1+ fibroblasts, with no labeling of CMs, consistent with previous studies (Murry et al., 2004). The results of the transplantation studies excluded that labeled CM clusters are derived from HSCs.

Endothelial fate mapping identifies quiescent and proliferating perivascular cells expressing early cardiac markers

The results above indicate ECs represent an originating source of CMs, rather than a transient cell type. This model predicts EC lineage tracing will mark intermediate, proliferating cell populations that express early cardiac markers, but have not yet differentiated to CMs.

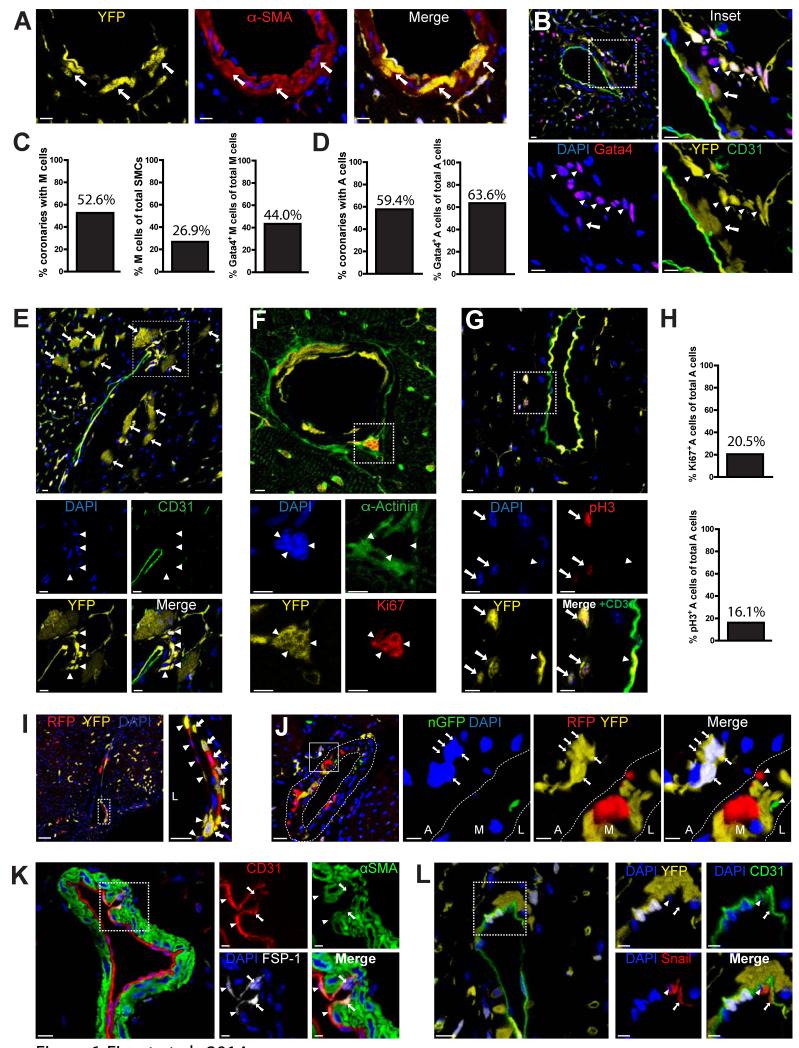

In support of this model, examination of cardiac tissue sections obtained from Tie-Cre-YFP, Tie-Cre-LacZ and End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mice revealed that besides ECs and CMs, EC fate mapping marked two additional cell types (Figure 6A,B & S5A-C). The first resided in the media layer of coronary arteries and was marked by expression of α Smooth Muscle Actin (αSMA) (Figure 6A). YFP+/αSMA+ double positive cells in the media layer of coronary vessels, termed M cells, also expressed the early cardiac transcription factor Gata4, but lost expression of the EC marker CD31 (arrow, Figure 6B). Serial histological analysis revealed that half of the coronary artery sections had M cells, which constituted approximately 30% of the SMC population in those coronary arteries. Moreover, 44% of the YFP+/αSMA+ M cells expressed nuclear Gata4 protein (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Endothelial fate mapping yields two distinct types of perivascular cells.

(A-G) IF analysis of cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice. (A) YFP+/αSMA+ cells (termed M cells) are present in the media layer of coronary arteries (arrows). Scale bars 10μm. DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining in these and subsequent IF images. (B) YFP+/CD31− cells (termed A cells) are present within, or immediately adjacent to, the adventitia layer of coronary vessels. Magnification inset shows both M (arrows) and A (arrowheads) cells acquire expression of Gata4 protein (see also Figure S5A). Scale bars 10μm. (C) Quantification using cardiac tissue serial sections revealed 52.6% of coronary arteries contain EC-derived M cells (left graph). In those coronaries, ~25% of SMCs are EC-derived M cells (middle) and 44% of M cells express Gata4 (right). (D) Quantification using serial sections revealed approximately half of coronary arteries contain endothelial-derived A cells (left graph) and ~65% of A cells express Gata4 (right). (E) A cells are often found in close proximity to YFP+ CMs (arrows). YFP+ A cells lost CD31 expression (arrowheads in magnified boxed areas below). Scale bars 10μm. (F) A cells (arrowheads in magnified boxed area) do not express α-Actinin, but stain positive for proliferation marker Ki-67. (G) A cells (arrows in magnified boxed area) stain positive for proliferation marker pH3. Arrowheads indicate YFP+ ECs. Scale bars 5μm. (H) Ki-67+ (top graph) and pH3+ (bottom) cells represent ~20% and 16% of A cells, respectively. (I,J) Epifluorescence analysis of cardiac sections from Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice. (I) Images show heterogeneous labeling of M cells expressing either RFP or YFP (arrows). Arrowheads indicate RFP+ or YFP+ ECs. Scale bars, 50μm for original and 20μM for Inset. (J) Clusters of A cells are uniformly marked by a single color fluorescent protein (YFP). In the magnified area, arrows point to YFP+ A cells. Heterogeneous labeling of fluorescent M cells (with RFP, YFP, or nGFP) is seen in the media layer (arrowheads, Merge). Scale bars, 20μm for original, 5μm for Insets. (K) IF analysis of cardiac sections from C57Bl/6 mice indicate a rare population of CD31+/FSP1+ ECs. (L) Cardiac sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice show a subpopulation of coronary ECs express Snail. Arrowheads indicate nuclear co-staining; arrows indicate cytoplasmic co-staining. Scale Bars, 10μm for originals, 5μM for insets. Abbreviations: L, M, and A in 6I & 6J insets stand for lumen, media, and adventitia, respectively, of the coronary arterial wall. See also Figure S5.

The second subpopulation, termed A cells, was found within, or immediately adjacent to the adventitia layer of coronary vessels (Figure 6B, E-G). Approximately half of the coronary arteries had A cells, and nearly 65% of them expressed Gata4 (Figure 6B, 6D, & S5A). A cells did not express EC markers, noted by the absence of CD31 expression, and were also negative for mature CM markers such as α-Actinin (Figure 6E,F). A cells were often small in size, and found in clusters that stained with antibodies recognizing cell-cycle markers Ki67 and phospho-Histone H3 (pH3) (Figure 6F,G). Around 20% of A cells stained positive for proliferation markers (Figure 6H). The proliferative phenotype was a unique property of A cells among all labeled cell types identified in the cell fate mapping experiments.

Furthermore, lineage tracing using Tie1-Cre-Confetti mice indicated coronary ECs and M cells were heterogeneously labeled and expressed different color fluorescent proteins (Figure 6I,J). In contrast, A cell clusters were uniformly marked by the same color fluorescent protein, suggesting A cell clusters expand from a single cell, consistent with their expression of proliferation markers (Figure 6J & S5D). Pulse-chase analysis of ECs using the inducible End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mouse showed that EC-derived perivascular M & A cells can be detected as early as 3 days after the end of the tamoxifen pulse (Figure S5C).

IF analysis showed no Cre recombinase protein expression in labeled M and A cells, supporting an endothelial origin (Figure S5E). Consistent with this possibility, staining of heart tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP and wild-type C57Bl/6 mice with antibodies recognizing mesenchymal markers illustrated that a rare subpopulation of coronary endothelium, representing ca. 2.5% of coronary ECs, expresses the mesenchymal marker FSP-1 (Zeisberg et al., 2007), as well as proteins known to initiate mesenchymal transformation such as Snail (Timmerman et al., 2004) (Figure 6 K,L & S5F,G). Subcellular Snail localization was observed in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments, a pattern that depends on the activation state of Snail (Domínguez et al., 2003). These data lend support to the idea that labeled perivascular cells of EC origin are derived by EndMT.

Endothelial progeny in perivascular areas include Sca-1+ cardiac progenitor cells

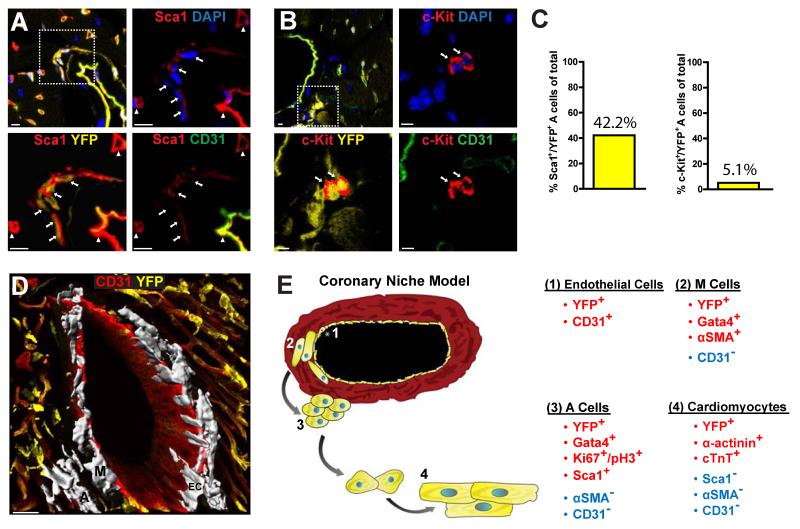

The results of the lineage tracing experiments and the identification of EC-derived intermediate cell populations suggested these intermediates represent cardiac progenitor cells. To test this possibility, we stained cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice with antibodies recognizing Sca1 and c-Kit, two established cell surface markers of CSCs. The results showed M cells did not express either marker. However, 42% of the YFP+ A cells stained positive for Sca1, whereas only a small subset (5%) of A cells stained positive for c-Kit (Figure 7A-C). Further histological analysis showed the majority (>70%) of perivascular, Sca1+/CD31− cells expressed YFP. These results suggest a significant fraction of Sca1+ CSCs are descendants of ECs. 3-D reconstruction of a coronary artery, using z-stack imaging, provided a physical depiction of the spatial arrangement of M and A cells within the coronary niche (Figures 7D & S6).

Figure 7. Endothelial fate mapping yields cardiac progenitor cells.

(A,B) IF analysis of cardiac tissue sections from Tie1-Cre-YFP mice illustrates YFP+/CD31- A cells express Sca1 (panel A) whereas a small subpopulation expresses c-Kit (panel B). Arrows in magnified areas in panel A indicate YFP+/Sca1+ cells, and arrowheads indicate Sca1+ ECs. Arrows in (B) indicate cKit+ cells in magnified areas. DAPI was used for nuclear counter staining. Scale bars 5μm. (C) Serial section analysis of cardiac tissue measured ~40% and 5% of A cells are Sca1+ or c-Kit+, respectively. (D) 3-D reconstruction illustrates endothelial-derived M and A cells (highlighted in white; representative cells marked with ‘M’ and ‘A’, respectively) within the coronary niche. ‘EC’ indicates coronary ECs. Scale bar 30μM. (E) Schematic drawing of the cardiac stem cell niche model illustrates the spatial organization of EC progeny and their corresponding expression profiles. See also Figure S6.

Considering the results described above and taking into account the cellular spatial relationships, (i.e., distance from coronary endothelium), we propose the following model (Figure 7E): endothelial, or endothelial-like cells give rise to quiescent, perivascular cells in the coronary wall that lose EC markers and acquire SMC characteristics. These cells, termed M cells, express early cardiac differentiation markers such as Gata4. Further distal to the vascular wall, M cells are replaced by A cells, which lose SMC characteristics, but maintain expression of Gata4, and acquire markers of CSCs such as Sca1+. A cells proliferate, leave the coronary niche, and differentiate to CMs. Thus, EC-derived YFP+ M and A perivascular cells within the medial and adventitial layers of coronary vessels likely serve as intermediate populations during generation of adult CMs.

Although the proposed model is consistent with the observed data, alternative interpretations may also explain the pattern of the lineage tracing results. For example, low level expression of endothelial genes in cardiac fibroblasts with cardiogenic potential could account for some of the observed labeling patterns. Or, as mentioned above, rare proliferating CMs may transiently express endothelial genes, and thus become labeled before expansion. While we did not observe expression of endothelial markers in fibroblasts and CMs, we cannot fully exclude these possibilities.

DISCUSSION

Current evidence showing low rates of CM apoptosis suggests a renewal mechanism is required to maintain cardiac tissue (Anversa et al., 2006; Ellison et al., 2007), yet there is little information regarding the native regenerative mechanisms during cardiac homeostasis. We have used Cre/Lox technology to generate a fate map of vascular cells in the healthy, adult heart. Our data show 1) ECs retain cardiogenic potential in the adult heart, similar to the differentiation capacity of cardiovascular progenitor cells during the early stages of cardiac development, 2) the EC-based cardiogenic process is rapid, but restricted to specific areas of the myocardium, 3) approximately 0.3% of the adult heart is comprised of endothelial-derived CMs, 4) the EC-based regenerative mechanism generates both quiescent (M cells) and proliferative (A cells) progeny expressing early stage cardiac differentiation genes such as Gata4, 5) Sca1+ cardiac stem cells are EC progeny and, 6) the coronary arteries serve as a structural component of the cardiac stem cell niche.

Although the classical role of ECs is to ensure proper functioning of the inner wall in blood vessels, evidence increasingly points to a more direct and active role of ECs in organ development, homeostasis, and tissue repair. ECs display exceptional differentiation potential and plasticity during development and disease. During development, ECs in the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta transform to budding blood cells and migrate to hematopoietic organs, ultimately residing in the bone marrow (Lancrin et al., 2009). This particular type of EC is called the hemogenic endothelium. In the adult, besides the angiogenic response of ECs to build new blood vessels after ischemia, they also undergo mesenchymal transition after injury (EndMT), producing SMA+ myofibroblasts in the heart, lung and kidney, supporting a fibrogenic potential of ECs (Zeisberg et al., 2007; Arciniegas et al., 2007; Zeisberg et al., 2008; Aisagbonhi et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012).

Our results indicate ECs also have cardiogenic potential in the adult. This notion is compatible with embryonic development when all three types of cardiovascular cells (ECs, SMCs, and CMs) are derived from multipotent progenitor cells expressing EC markers such as Vegfr2 (Kattman et al., 2006). Furthermore, inactivation of SCL/TAL1 can transform vasculature to cardiac cells, turning the yolk sac from a hematopoietic tissue to a contracting sheet of CMs (Van Handel et al., 2012). This striking outcome suggests, at least early in development, EC to CM transition can be accomplished by switching off a single transcriptional regulator.

Collectively, the data presented here during cardiac homeostasis, and previous work showing ECs contribute to angiogenesis and fibrosis after injury, indicate ECs remain multipotent in the adult. However, it is not clear if this is a universal property of mature cardiac ECs, or confined to specific EC subpopulations within coronary arteries. It is also likely that a multipotent cardiovascular stem cell expressing EC markers exists in the adult and is genetically labeled using EC lineage tracing approaches. Finally, the cardiogenic endothelium may represent one mechanism of cardiac regeneration, but our findings do not exclude proliferation of resident CMs, or alternative sources of CSCs (Senyo et al., 2013; Malliaras et al., 2013).

Although the site of the original cell type with EC characteristics that gives rise to CMs remains currently undetermined, our data provide evidence that the majority (>70%) of Sca1+ CSCs are derived from cells with endothelial characteristics. We found EC-derived Sca1+ perivascular cells lost endothelial markers and gave rise to CD31−/Sca1+ cells. These cells expressed early cardiac markers such as Gata4, but lacked mature CM characteristics such as sarcomeric structures and α-Actinin expression. In support of this finding, Sca1+ CSCs continuously replace myocardial cells in the adult heart (Uchida et al., 2013). In contrast, we found limited overlap between endothelial-derived YFP+ cells and c-Kit+ cells, suggesting the majority of c-Kit+ cells in the heart belong to a different lineage.

An important finding of EC lineage tracing during cardiac homeostasis is the emergence of the coronary arteries as the site of the CSC niche. Previous studies show the vasculature is an integral component of most well characterized stem cell niches in various organs, such as the bone marrow and the subventricular zone (SVZ) in the brain (Li and Clevers, 2010; Fioret and Hatzopoulos, 2014). Our data suggest this biological strategy extends to the heart, with the coronary vessels serving as the CSC niche. In support of this finding, vascular progenitor cells have been observed in the walls of coronary arteries in the human heart (Bearzi et al., 2009).

Moreover, our data show EC-derived Gata4+ cells around coronary arteries can be divided into subpopulations based on several criteria (location, size, molecular markers, and proliferation status), indicating the CSC niche is organized in a radial manner with the vasculature at the center. M-cells, closest to the lumenal ECs, are quiescent and combine smooth muscle and early cardiac characteristics, whereas A cells further afield in the adventitia are proliferative and acquire expression of Sca1. In many respects, the CSC niche shares similarities with the neuronal stem cell niches in the brain. Here, neuronal stem cells in the SVZ give rise to astrocytes (a mesenchymal cell population similar to αSMA+ cells), which differentiate to groups of proliferating cells before joining the rostral migratory stream (Fuentealba et al., 2012). The cardiac renewal process is also confined to a small subpopulation of mature CMs, similar to the adult brain where renewal is mainly restricted to the olfactory bulb and dentate gyrus.

Our data indicate ECs, through the process of EndMT, are capable of generating cells with CSC characteristics in the uninjured, adult heart. We and others have shown that TGF-β/BMP and Wnt signaling regulate EndMT after injury, and it is likely these pathways also regulate the process during homeostasis (Zeisberg et al., 2007; Aisagbonhi et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012). In addition, Sonic hedgehog signaling has been shown to activate Sca1+ cells with stem cell properties residing in the adventitia layer of the arterial wall, and may also influence cardiogenic EC fate (/). The mechanisms that direct trafficking of the endothelial-derived cardiac progenitors remain to be determined. It is possible that A cells enter the circulation and are recruited to distal heart areas by chemoattractants such as SDF-1, similarly to mesenchymal stem cells (Wynn et al., 2004; Laird et al., 2008). Alternatively, local gradients of chemoattractants may recruit cells from their niche.

It is intriguing that adult ECs can give rise to myofibroblasts after cardiac injury (Zeisberg et al., 2007; Aisagbonhi et al., 2011). The striking parallels on the origins of CSCs and myofibroblasts raise the possibility the two processes are intrinsically linked. Thus, EC-derived CSCs may switch to a pro-fibrotic phenotype in the disease environment after injury, and alter their differentiation from CMs to myofibroblasts to preserve ventricular integrity. This scenario is reminiscent of the situation in skeletal muscle where myoblasts switch from a regenerative to a pro-fibrotic phenotype with aging (Brack et al., 2007). The ability of endogenous cardiac cells to change fate based on their environment is further supported by a recent, exciting finding which showed after cardiac injury, murine cardiac fibroblasts can be reprogrammed in vivo into CMs (Qian et al., 2012).

Our results also show EC-derived CMs represent a small number of the total cardiac cell pool and are confined to specific areas. The first observation likely reflects the slow rate of cardiac renewal necessary during cardiac homeostasis, a fact also supported by the low number of new CMs generated annually in the human and mouse hearts (Bergmann et al., 2009; Murry and Lee, 2009). The second suggests renewal may take place in specific sites characterized by high attrition rates due to work overload or structural constrains. In support of this possibility, clinical studies showed cardiac tissue fibrosis often appears in the perivascular space, or the insertion points between ventricles (Biernacka and Frangogiannis, 2011; Karamitsos and Neubauer, 2013), sites that contain the majority of the labeled clusters we identified in the mouse hearts.

Our model may also provide novel insight into how coronary arterial disease can lead to heart failure. It is likely that inflammation, oxidative stress, ischemia, calcification, and fibrosis around coronary vessels negatively impact the niche environment, disturbing the normal proliferation and differentiation of CSCs. This effect could compromise cardiac homeostasis, weaken the heart muscle, and eventually lead to hypertrophy and remodeling. Therefore, our findings may open novel opportunities to establish the intrinsic cardiac molecular mechanisms, and identify factors that prevent a pro-fibrotic fate switch after injury in favor of cardiac regeneration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

ECs and their progeny were genetically labeled using Cre-LoxP recombination tools to activate expression of β-gal or various fluorescent proteins under the control of the ubiquitously active ROSA gene locus (Soriano, 1999). Three independent transgenic mouse lines were used to direct constitutive or inducible Cre recombinase activity specifically in ECs: the Tie1-Cre and VE-Cadherin-Cre lines (Gustafsson et al. 2001; Alva et al., 2006) and the endothelial-SCL-Cre-ERT line, which drives a Tamoxifen-inducible Cre-ERT recombinase under control of the 5′ endothelial-specific enhancer of the stem cell leukemia (SCL) gene locus (Göthert et al., 2004). The EC-specific Cre lines were crossed to R26RstopLacZ (Soriano, 1999) or R26RstopYFP (Srinivas et al., 2001) mice to generate double transgenics. The Tie1-Cre mouse line was also bred with the multi-fluorescent reporter R26RstopConfetti (Snippert et al., 2010). Finally, transgenic mice expressing β-gal directly under the Tie1 promoter (Korhonen et al., 1995) were used to assess Tie1 expression in cardiac tissue.

Whole mount β-gal activity staining assay

Whole mouse hearts were isolated into cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 1 hr at 4°C in 1× PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After fixation, hearts were washed thrice with 1× PBS for 15 min each, and placed overnight (O/N) at 30°C in X-gal staining solution (1 mg/ml X-gal, 5 mM potassium ferro- and ferricyanate, 2 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.02% NP-40 in 1× PBS). Whole-mount hearts were photographed, stored in 10% phosphate buffered formalin at room temperature (RT) O/N and embedded in paraffin for sectioning.

Immuno- and epifluorescence

For cryosectioning, freshly isolated hearts were perfused with 1× PBS, bisected transversely, and fixed in 4% PFA dissolved in 1× PBS for 2 hrs at RT. Hearts were rinsed thrice in 0.1% TX-100 solution in 1× PBS for 5 min each, embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT; VWR), sectioned and stored at −70°C. Slides were thawed at RT and rehydrated in 1× PBS for 30 min to remove OCT. Sections were washed twice in 0.1% TX-100 solution for 3 min each, and permeabilized in 0.5% TX-100 solution for 20 min at RT. Sections were then blocked in 0.1% TX-100 solution containing 2% BSA and 10% normal goat serum (Sigma) for 30 min at RT, and incubated with primary antibodies O/N at 4°C. Afterwards, slides were washed four times in 1X PBS for 10 min each, incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 hr at RT, washed four times in 1× PBS for 10 min each, and mounted with VECTASHIELD fluorescent mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Antibody sources and dilutions are included in the Supplement.

Imaging and 3-D Reconstruction

A series of confocal images (z-stack) were acquired sequentially on 100μm cardiac sections. Image stacks were attained for each channel using an LSM 710 META inverted microscope (Zeiss). Images were maximally projected using ZEN or ImageJ software and reconstructed into 3-D Z-series using Imaris (Bitplane) image analysis software.

Quantification of endothelial-derived cardiomyocytes per volume of cardiac tissue

Cardiac cross-sections from End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ mice, previously stained with X-gal for β-gal activity and counterstained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E), were analyzed to determine the number of labeled CMs per volume of cardiac tissue. Transverse cardiac sections were imaged (Nikon AZ-100M widefield) and the average area was calculated using the Region Measurements function of MetaMorph Image Analysis Software. The μm/pixel calibration value was used to convert pixels into area of tissue in μm2. Volume of total cardiac tissue in μm3 was calculated by multiplying the area obtained per section by the 10 μm thickness of tissue for each slide. A total of 352 slides (with 4 separate sections per slide; total of 1,408 sections) were imaged to analyze and estimate global cardiac CM labeling in the End-SCL-CreERT-LacZ pulsechase (N=17 mice) lineage tracing experiments.

Statistical analysis

All values were reported as mean +/− S.D. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test for all statistical analysis comparisons. Statistical significance was expressed as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Endothelial cells have cardiogenic potential in the adult heart.

The endothelial-based cardiogenic process is rapid but spatially restricted.

Endothelial cells produce quiescent and proliferative cardiac stem cells.

Coronary arteries serve as radially organized cardiac stem cell niches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. H. Scott Baldwin, Douglas Sawyer, Chris Brown, Joey Barnett, and Ela Knapik for stimulating discussions, technical help, and generously sharing tools. We are indebted to Dr. David Harrison and Jing Wu for generously providing hearts from mice engrafted with fluorescently-labeled bone marrow. We also thank Drs. Bryan Shepherd and Chun Li, in the Department of Biostatistics at Vanderbilt, for assistance with statistical analyses. This work was supported by Training in Pharmacological Sciences Grant T32GM007628 and American Heart Association pre-doctoral fellowships to B.A.F., and NIH grants U01HL100398 and R01HL083958 to A.K.H. B.A.F. performed all experiments and wrote the manuscript; J.D.H. and D.T.P. helped with tissue section staining, imaging and quantification. A.K.H. supervised experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Information for this article includes Supplemental References, Experimental Procedures (Tamoxifen preparation & administration, antibody specifications, analysis of regional YFP+ CM location and global YFP+ CM percentage, statistical analysis of CM clusters, quantification of perivascular YFP+ cells, bone marrow engraftment), and six Figures.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Adler CP, Friedburg H, Herget GW, Neuburger M, Schwalb H. Variability of cardiomyocyte DNA content, ploidy level and nuclear number in mammalian hearts. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 1996;429:159–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00192438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisagbonhi O, Rai M, Ryzhov S, Atria N, Feoktistov I, Hatzopoulos AK. Experimental myocardial infarction triggers canonical Wnt signaling and endothelial-to- mesenchymal transition. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011;4:469–483. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alva JA, Zovein AC, Monvoisin A, Murphy T, Salazar A, Harvey NL, Carmeliet P, Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:759–767. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anversa P, Kajstura J, Leri A, Bolli R. Life and death of cardiac stem cells a paradigm shift in cardiac biology. Circulation. 2006;113:1451–1463. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniegas E, Frid MG, Douglas IS, Stenmark KR. Perspectives on endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: potential contribution to vascular remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007;293:L1–L8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00378.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearzi C, Leri A, Monaco FL, Rota M, Gonzalez A, Hosoda T, Pepe M, Qanud K, Ojaimi C, Bardelli S, et al. Identification of a coronary vascular progenitor cell in the human heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:15885–15890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907622106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka A, Frangogiannis NG. Aging and cardiac fibrosis. Aging Dis. 2011;2:158–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudoulas KD, Hatzopoulos AK. Cardiac repair and regeneration: the Rubik’s cube of cell therapy for heart disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 2009;2:344–358. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AN, van Amerongen R, Palmer TD, Nusse R. Lineage tracing with Axin2 reveals distinct developmental and adult populations of Wnt/β-catenin-responsive neural stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:7324–7329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305411110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, Lee M, Kuo CJ, Keller C, Rando TA. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science. 2007;317:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1144090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-Y, Qin L, Barnes C, Charisse K, Yi T, Zhang X, Ali R, Medina PP, Yu J, Slack FJ, et al. FGF regulates TGFβ signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via control of let-7 miRNA expression. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1684–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey D, Han L, Bauer M, Sanada F, Oikonomopoulos A, Hosoda T, Unno K, De Almeida P, Leri A, Wu JC. Dissecting the molecular relationship among various cardiogenic progenitor cells. Circ. Res. 2013;112:1253–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doevendans PA, Daemen MJ, Muinck E.D. de, Smits JF. Cardiovascular phenotyping in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;39:34–49. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez D, Montserrat-Sentis B, Virgos-Soler A, Guaita S, Grueso J, Porta M, Puig I, Baulida J, Franci C, Garcia de Herreros A. Phosphorylation regulates the subcellular location and activity of the Snail transcriptional repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5078–5089. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.5078-5089.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison GM, Torella D, Karakikes I, Nadal-Ginard B. Myocyte death and renewal: modern concepts of cardiac cellular homeostasis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2007;4:S52–S59. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison GM, Vicinanza C, Smith AJ, Aquila I, Leone A, Waring CD, Henning BJ, Stirparo GG, Papait R, Scarfò M, et al. Adult c-kit pos cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell. 2013;154:827–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioret BA, Hatzopoulos AK. Comparative analysis of adult stem cell niches. In: Ao A, Hao J, Hong C, editors. Chemical Biology in Regenerative Medicine: Bridging Stem Cells and Future Therapies. Wiley-The Atrium, Southern Gate; Chichester, United Kingdom: Sep 1st, 2014. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba LC, Obernier K, Alvarez-Buylla A. Adult neural stem cells bridge their niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göthert JR, Gustin SE, van Eekelen JAM, Schmidt U, Hall MA, Jane SM, Green AR, Göttgens B, Izon DJ, Begley CG. Genetically tagging endothelial cells in vivo: bone marrow-derived cells do not contribute to tumor endothelium. Blood. 2004;104:1769–1777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greif DM, Kumar M, Lighthouse JK, Hum J, An A, Ding L, Red-Horse K, Espinoza FH, Olson L, Offermanns S, et al. Radial construction of an arterial wall. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson E, Brakebusch C, Hietanen K, Fässler R. Tie-1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in endothelial cells of embryoid bodies and transgenic mice. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:671–676. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Handel B, Montel-Hagen A, Sasidharan R, Nakano H, Ferrari R, Boogerd CJ, Schredelseker J, Wang Y, Hunter S, Org T, et al. Scl represses cardiomyogenesis in prospective hemogenic endothelium and endocardium. Cell. 2012;150:590–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierlihy AM, Seale P, Lobe CG, Rudnicki MA, Megeney LA. The postnatal heart contains a myocardial stem cell population. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamitsos TD, Neubauer S. The prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement CMR in nonischemic cardiomyopathies. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2013;15:326. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopinke D, Brailsford M, Shea JE, Leavitt R, Scaife CL, Murtaugh LC. Lineage tracing reveals the dynamic contribution of Hes1+ cells to the developing and adult pancreas. Development. 2011;138:431–441. doi: 10.1242/dev.053843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen J, Lahtinen I, Halmekytö M, Alhonen L, Jänne J, Dumont D, Alitalo K. Endothelial-specific gene expression directed by the tie gene promoter in vivo. Blood. 1995;86:1828–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DJ, von Adrian UH, Wagers AJ. Stem cell trafficking in tissue development, growth, and disease. Cell. 2008;132:612–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancrin C, Sroczynska P, Stephenson C, Allen T, Kouskoff V, Lacaud G. The haemangioblast generates haematopoietic cells through a haemogenic endothelium stage. Nature. 2009;457:892–895. doi: 10.1038/nature07679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Seinfeld J, Galang G, Tseliou E, Cheng K, Sun B, Aminzadeh M, Marbán E. Cardiomyocyte proliferation and progenitor cell recruitment underlie therapeutic regeneration after myocardial infarction in the adult mouse heart. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013;5:191–209. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CM, Meeson AP, Robertson SM, Hawke TJ, Richardson JA, Bates S, Goetsch SC, Gallardo TD, Garry DJ. Persistent expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter, Abcg2, identifies cardiac SP cells in the developing and adult heart. Dev. Biol. 2004;265:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Battaglia M, Latronico MVG, Coletta M, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ. Res. 2004;95:911–921. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici D, Shore EM, Lounev VY, Kaplan FS, Kalluri R, Olsen BR. Conversion of vascular endothelial cells into multipotent stem-like cells. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/nm.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouquet F, Pfister O, Jain M, Oikonomopoulos A, Ngoy S, Summer R, Fine A, Liao R. Restoration of cardiac progenitor cells after myocardial infarction by self-proliferation and selective homing of bone marrow-derived stem cells. Circ. Res. 2005;97:1090–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194330.66545.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Virag JI, Bartelmez SH, Poppa V, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Lee RT. Turnover after the fallout. Science. 2009;324:47–48. doi: 10.1126/science.1172255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, Nakamura T, Gaussin V, Mishina Y, Pocius J, Michael LH, Behringer RR, Garry DJ, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu SP, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident Sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:9349–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711382105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister O, Mouquet F, Jain M, Summer R, Helmes M, Fine A, Colucci WS, Liao R. CD31-but not CD31+ cardiac side population cells exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation. Circ. Res. 2005;97:52–61. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173297.53793.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu J, Srivastava D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota M, Padin-Iruegas ME, Misao Y, Angelis AD, Maestroni S, Ferreira-Martins J, Fiumana E, Rastaldo R, Arcarese ML, Mitchell TS, et al. Local activation or implantation of cardiac progenitor cells rescues scarred infarcted myocardium improving cardiac function. Circ. Res. 2008;103:107–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu T-D, Guerquin-Kern J-L, Lechene CP, Lee RT. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2013;493:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, Giacomello A, Abraham MR, Marbán E. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin C-S, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev. Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertran E, Perez-Pomares JM, Diez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, et al. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida S, De Gaspari P, Kostin S, Jenniches K, Kilic A, Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Grosse Kreymborg K, Renz H, Walsh K, et al. Sca1-derived cells are a source of myocardial renewal in the murine adult heart. Stem Cell Rep. 2013;1:397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Hu Q, Nakamura Y, Lee J, Zhang G, From AHL, Zhang J. The role of the Sca-1+/CD31-cardiac progenitor cell population in postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1779–1788. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, O’Neill L, Evans CA, Wraith JE, Fairbairn LJ, Bellantuono I. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 104:2643–2645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg EM, Potenta SE, Sugimoto H, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:2282–2287. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.