Abstract

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) is the principal omega-3 fatty acid in mammalian brain gray matter, and emerging preclinical evidence suggests that DHA has neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties. This study investigated relationships among DHA status, neurocognitive performance, and cortical metabolism measured with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) in healthy developing male children (aged 8–10 years, n = 38). Subjects were segregated into low-DHA (n = 19) and high-DHA (n = 19) status groups by a median split of erythrocyte DHA levels. Group differences in 1H MRS indices of cortical metabolism, including choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), glutamine + glutamate + γ-aminobutyric acid (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), were determined in the right and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (R/L-DLPFC, BA9) and bilateral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, BA32/33). Group differences in neurocognitive performance were evaluated with the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test and identical-pairs version of the continuous performance task (CPT-IP). Subjects in the low-DHA group consumed fish less frequently (P = 0.02), had slower reaction times on the CPT-IP (P = 0.007), and exhibited lower mI (P = 0.007), NAA (P = 0.007), Cho (P = 0.009), and Cr (P = 0.01) concentrations in the ACC compared with the high-DHA group. There were no group differences in ACC Glx or any metabolite in the L-DLPFC and R-DLPFC. These data indicate that low-DHA status is associated with reduced indices of metabolic function in the ACC and slower reaction time during sustained attention in developing male children.

Keywords: Docosahexaenoic acid, myo-inositol, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Anterior cingulate cortex, Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, omega-3 fatty acid, omega-6 fatty acid

Introduction

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) is the principal long-chain omega-3 fatty acid in mammalian cortical gray matter and comprises approximately 15–20% of total fatty acid composition of the adult frontal cortex.1,2 Human cortical DHA accrual begins in utero during the second and third trimester3,4 and continues to increase rapidly during childhood and adolescence1,5 in association with rapid changes in the frontal cortical gray matter density.6 Emerging clinical evidence suggests that higher DHA status during pre- and post-natal development is associated with better neurocognitive trajectories and IQ in childhood.7–14 However, there is currently nothing known about the relationship between DHA status and human cortical metabolism during development.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) is a non-invasive imaging technique that measures concentrations of different chemical indices of cortical metabolism. For example, myo-inositol (mI) is metabolized from glucose via 1L-mI 1-phosphate synthase and is predominantly concentrated in astroctyes,15,16 and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) is primarily localized to neurons and is positively correlated with mitochondrial metabolism.17,18 While there is currently little known about DHA status and 1H MRS indices of cortical metabolism, we previously reported that perinatal deficits in brain DHA accrual were associated with selective mI reductions in the adult rat medial prefrontal cortex measured by in vivo 1H MRS.19 Moreover, emerging data suggest that DHA status is associated with different imaging measures of functional cortical activity in adult subjects.20

In the present study, we investigated the relationship between DHA status and different chemical indices of cortical metabolism in the right and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (R/L-DLPFC, BA9) and bilateral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, BA32/33) of healthy male children. Low- and high-DHA status was defined by a median split of erythrocyte DHA levels. Importantly, erythrocyte DHA composition is positively correlated with habitual dietary fish intake,21–23 and non-human primate24 and rodent25 studies have found that erythrocyte and cortical DHA levels are positively correlated. Based on our preclinical 1H MRS findings, our specific prediction was that low erythrocyte DHA status would be associated with lower cortical mI concentrations compared with high erythrocyte DHA status.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Subjects were healthy male children 8–10 years of age that had no personal or first-degree family history of Axis I psychiatric disorders as determined by the Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes.26 Subjects were screened to ensure that they could receive an MRS exam safely (e.g. had no ferromagnetic metal in their body and were not claustrophobic), were right-hand dominant by the Crovitz test for handedness,27 were not taking (current or lifetime) psychoactive medications, and did not have a history of seizures, major medical illness, or traumatic brain injury. Children were excluded if their birth was associated with obstetric complications (e.g. preterm delivery), ascertained from the biological mother, or if they were taking DHA-containing supplements. Socioeconomic status was estimated from annual household income. Duration of breastfeeding was acquired from the biological mother, and a validated Omega-3 Dietary Intake Questionnaire was administered to the parent to estimate the child’s current dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake.28 Subjects provided written assent and their legal guardians provided written informed consent for study participation after the study procedures were fully explained. This study was approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board.

Sustained attention task

Sustained attention was evaluated with the identical-pairs version of the continuous performance task (CPT-IP) as previously described.29,30 Subjects were presented with a series of one-digit numbers and asked to respond with a button press using their right index finger when they saw the same number repeated twice sequentially. Numbers were presented at 750 ms intervals. Targets constituted 12.5% of the presentations (five per block) and were randomly distributed. The attention task was alternated with a control task consisting of the number ‘1’ presented at the same rate as the CPT-IP. The control task required subjects to press the response button five times in order to control for finger movement. Both experimental and control tasks were presented in epochs of 30 seconds each for a total of 40 numbers per epoch. Five blocks consisting of one epoch each of the active and control tasks were obtained, as was an additional control epoch at the start of the session. Responses were electronically recorded to permit calculation of response parameters (i.e. sensitivity, ‘A’ and response bias, ‘B’). Prior to all imaging sessions, subjects were given a training session during which they were required to demonstrate an understanding of the CPT-IP task. Performance on the CPT-IP task was evaluated using percent correct selections, errors of commission, discriminability (0.5+ ((hit rate–false alarm rate)(1 + hit rate–false alarm rate))/(4 × hit rate (1–false alarm rate)), and reaction time to target (ms). The CPT-IP task was administered using PsyScope® software on a Macintosh computer.

Kaufman brief intelligence test

Vocabulary and matrices scores (expressed as national percentile ranks) on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT) were evaluated.31

Gas chromatography

Whole blood (20 ml) was collected into ethylenediami-acid Vacutainer tubes and centrifuged for 20 minutes (3000 × g, 4°C). Plasma and buffy coat were removed and erythrocytes washed 3× with 0.9% NaCl and stored at −80°C. The total fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes was determined using saponification and methylation methods described previously.32,33 Fatty acid composition was determined with a Shimadzu GC-2014 (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., Columbia MD, USA). Analysis of fatty acid methyl esters was based on area under the curve calculated with Shimadzu Class VP 4.3 software. Fatty acid identification was based on retention times of authenticated fatty acid methyl ester standards (Matreya LLC Inc., Pleasant Gap, PA, USA). All samples were processed by a technician blinded to treatment. Composition data are expressed as the weight percent of total fatty acids (mg fatty acid/100 mg fatty acids).

1H MRS acquisition

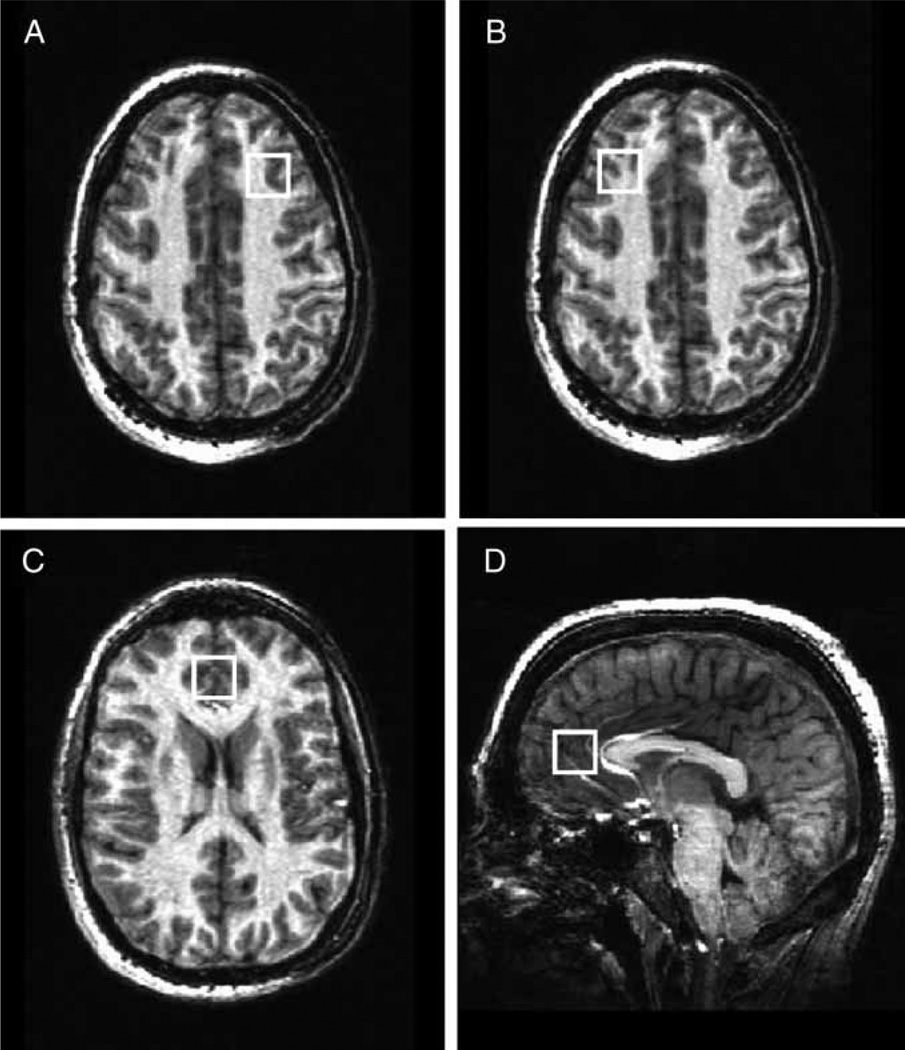

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 1H MRS data were acquired on a Varian 4 T whole-body scanner (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). A 1H TEM (Transverse ElectroMagnetic) head coil was used as a transmitter/receiver. A multi-slice scout image was initially acquired for MRS voxel positioning. The scout image was followed by the acquisition of three-dimensional whole-head MRI using MDEFT (Modified Driven Equilibrium Fourier Transform) pulse sequence for tissue segmentation.34 After MRS voxel positioning, the magnetic field homogeneity was optimized using an automatic shim method FASTMAP (Fast Automatic Shimming Technique by Mapping Along Projections).35 A typical water line width in the MRS voxel was 10–12 Hz. Three single-voxel PRESS (Point RESolved Spectroscopy) spectra were collected in bilateral (BA32/33) and R/L-DLPFC, BA9 (Fig. 1). Spectra were acquired with repetition time 2000 ms, echo time 23 ms, voxel size 8 cc and 64 averages with water suppression by the VAPOR (Variable Pulse powers and Optimizing Relaxation delays) method.36 For computations of metabolite levels and eddy current correction, one reference spectrum without water suppression was collected at the same voxel position with the same parameters except four averages were acquired, and receiver gain reduced.

Figure 1.

Voxel placement in the left (A) and right (B) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, BA9), and bilateral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, BA32/33) (C,D).

To determine the tissue content within MRS voxels, MDEFT images were processed using a contrast-driven algorithm in SPM (Statistical Parametrical Mapping; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). The tissue segmentation data are presented in the percentage of gray matter (%GM), white matter (%WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (%CSF). For the determination of metabolite levels, localized spectra were analyzed using LCModel (Linear Combination of Model spectra) with the water reference in unsuppressed-water spectra.37 All metabolite data except for glutamine + glutamate + γ-aminobutyric acid (Glx) were corrected with T1 and T2 relaxation losses using available values.38 Metabolite levels were also corrected with tissue segmentation data. The differences of water concentrations, T1 and T2 relaxation times in GM, WM, and CSF were also taken into consideration for computation. All metabolite levels are presented as absolute concentrations (mM).

Statistical analyses

Group (low-DHA, high-DHA) differences in demographic variables and primary outcome measures were evaluated with unpaired t-tests (two-tailed) and adjusted for multiple comparisons (α = 0.01). Chi-square tests were used for dichotomous variables. The distribution of primary outcome measures was pre-examined for normality using Bartlett’s test. Effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d, with small, medium, and large effect sizes being equivalent to d-values of 0.30, 0.50, and 0.80, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to identify relationships between primary outcome measures (two-tailed, α=0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using GB-STAT (Version 10.0, Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Springs MD, USA).

Results

Subject characteristics

Forty-eight subjects were screened, and 38 subjects met the entrance criteria and received an MRI and 1H MRS scan. A median split of subjects based on erythrocyte DHA composition yielded low-DHA (n = 19) and high-DHA (n= 19) groups, and group differences in erythrocyte fatty acid composition are presented in Table 1. Mean erythrocyte DHA levels in the low-DHA group (2.5 ± 0.2%) were significantly lower than the high-DHA group (4.1 ± 0.2%, P < 0.0001, d= 1.6). The low-DHA group also exhibited lower eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) composition and lower EPA +DHA (‘omega-3 index’), and greater arachidonic acid (AA)/DHA and AA/ EPA +DHA ratios compared with the high-DHA group. Compared with the high-DHA group, the low-DHA group also exhibited greater linoleic acid (18:2n-6), but not fatty acid products of linoleic acid including arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) or docosatetraenoic acid (22:4n-6). Comparison of low-DHA and high-DHA group demographics is presented in Table 2. The mean annual household income, an index of socioeconomic status, in the low-DHA ($75.8 ± 4.5 thousand dollars) and high-DHA ($72.6 ± 7.5 thousand dollars) groups did not differ significantly (P = 0.72). The only variable that differed significantly between groups was weekly fish intake frequency, which was significantly greater in the high-DHA group compared with the low-DHA group (P = 0.02). Among all subjects (n = 38), erythrocyte DHA (r=+0.57, P = 0.0002) and EPA (r=+0.39, P = 0.02) compositions were positively correlated with weekly fish intake frequency.

Table 1.

Erythrocyte fatty acid composition

| Fatty acid* | Low-DHA (n = 19) |

High-DHA (n = 19) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0001 |

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 19.5 ± 0.3 | 19.8 ± 0.2 | 0.41 |

| Stearic acid (18:0) | 19.9 ± 0.1 | 19.9 ± 0.1 | 0.75 |

| Oleic acid (18:1n-9) | 14.2 ± 0.2 | 14.2 ± 0.2 | 0.85 |

| Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 0.2 | 0.009 |

| Arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) | 20.9 ± 0.2 | 20.9 ± 0.4 | 0.93 |

| Docosatetraenoic acid (22:4n-6) | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.49 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.69 ± 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.47 |

| EPA + DHA (omega-3 index) | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 0.0001 |

| AA/EPA | 74.1 ± 13.1 | 47.8 ± 7.9 | 0.08 |

| AA/DHA | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 0.0001 |

| AA/EPA + DHA | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 0.0001 |

Data are expressed as weight percent of total fatty acids (mg fatty acid/100 mg fatty acids) ± SEM. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at [alpha]= 0.05

Table 2.

Group demographics

| Low-DHA (n = 19) |

High-DHA (n = 19) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 0.35 |

| Gender (% male) | 100 | 100 | |

| Race (n) | |||

| Caucasian | 17 | 16 | 0.49 |

| African American | 0 | 2 | 0.24 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.51 |

| Siblings (n) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.11 |

| Height (cm) | 137.4 ± 2.3 | 140.9 ± 3.1 | 0.28 |

| Body weight (kg) | 34.5 ± 3.1 | 38.5 ± 2.2 | 0.29 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.8 ± 1.3 | 18.9 ± 1.1 | 0.46 |

| Breastfeeding duration (months) | 9.7 ± 2.4 | 10.4 ± 2.5 | 0.83 |

| Fish intake (times/week) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Vitals and labs | |||

| Temperature (Celcius) | 97.9 ± 0.3 | 97.6 ± 0.2 | 0.42 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 77.9 ± 2.5 | 81.9 ± 3.2 | 0.35 |

| Blood pressure – systolic | 104.7 ± 2.1 | 109.5 ± 2.3 | 0.14 |

| Blood pressure – diastolic | 62.7 ± 2.4 | 63.5 ± 2.6 | 0.81 |

| WBC (K/Ul) | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 0.13 |

| RBC (M/Ul) | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 0.73 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 85.1 ± 1.5 | 92.1 ± 3.8 | 0.12 |

Values are group mean ± SEM.

Neurocognitive performance

Group differences in KBIT scores and CPT-IP performance measures are presented in Table 3. There were no group differences in KBIT vocabulary or matrices scores. On the CPT-IP, reaction time was significantly slower in the low-DHA group compared with the high-DHA group (P = 0.007, d = 1.0). There were no significant group differences for other CPT-IP performance measures.

Table 3.

Neurocognitive performance

| Low-DHA (n = 19) |

High-DHA (n = 19) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| KBIT | |||

| Vocabulary | 78.3 ± 4.7 | 85.1 ± 2.3 | 0.21 |

| Matrices | 87.8 ± 3.3 | 82.1 ± 4.3 | 0.31 |

| CPT-IP | |||

| Percent correct | 82.3 ± 3.8 | 83.2 ± 4.4 | 0.87 |

| Discriminability | 0.96 ± 0.1 | 0.95 ± 0.1 | 0.64 |

| Commision errors | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.71 |

| Reaction time (ms) | 693.1 ± 12.6 | 638.5 ± 14.4 | 0.007 |

Values are group mean ± SEM.

KBIT, Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (National percentile rank). Values in bold indicate statistical significance at [alpha]= 0.05

1H MRS

Group differences in metabolite concentrations in ACC 1H MRS spectra are presented in Fig. 2. Subjects in the low-DHA group exhibited significantly lower mI (−22%, P = 0.007, d= 1.0), NAA (−18%, P = 0.007, d = 1.0), choline (Cho) (−21%, P = 0.009, d= 0.9), and creatine (Cr) (−17%, P = 0.01, d= 0.9) concentrations in the ACC compared with the high-DHA group. There were no group differences in ACC Glx (P = 0.49). There were no significant group differences in L-DLPFC and R-DLPFC metabolite concentrations (Table 4). Among all subjects, ACC mI concentrations were significantly greater than the R-DLPFC (+30%, P < 0.0001) and LDLPFC (+29%, P < 0.0001), ACC Cho concentrations were significantly greater than the L-DLPFC (+19%, P < 0.0001), but not R-DLPFC (P = 0.19), and ACC Cr concentrations were significantly greater than the R-DLPFC (+21%, P< 0.0001) and L-DLPFC (+26%, P < 0.0001). NAA and Glx concentrations in the ACC did not differ significantly from those observed in the L-DLPFC and R-DLPFC.

Figure 2.

Concentrations (mM) of choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), glutamine + glutamate + γ-aminobutyric acid (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) in the anterior cingulate cortex of low-DHA (n = 19) and high-DHA (n = 19) groups. Data are expressed as group mean ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared with low-DHA.

Table 4.

DLPFC metabolite concentrations

| Hemisphere* | Low-DHA (n = 19) |

High-DHA (n = 19) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-DLPFC | |||

| Cho | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.77 |

| Cr | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 0.42 |

| Glx | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 0.78 |

| mI | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 0.67 |

| NAA | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 0.66 |

| R-DLPFC | |||

| Cho | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.28 |

| Cr | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.27 |

| Glx | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 0.17 |

| mI | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 0.71 |

| NAA | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 0.96 |

Values are group mean metabolite concentrations (mM)±SEM.

Correlations

Among all subjects (n = 38), erythrocyte DHA was positively correlated with ACC mI (r=+0.36, P = 0.03), and both erythrocyte DHA (r = −0.52, P = 0.001) and ACC mI (r = −0.36, P = 0.04) were inversely correlated with reaction time. Erythrocyte DHA and CPT-IP reaction time were not significantly correlated with other metabolite concentrations in the ACC or L/R-DLPFC. Erythrocyte EPAwas positively correlated with ACC mI (r=+0.62, P = 0.0002) and ACC NAA (r=+0.55, P = 0.0009), ACC Cho (r=+0.47, P = 0.005), and ACC Cr (r=+0.53, P = 0.001), but not reaction time (r = −0.11, P = 0.54). Erythrocyte EPA +DHA (omega-3 index) was positively correlated with ACC mI (r=+0.37, P = 0.03), but not other metabolites, and was inversely correlated with reaction time (r = −0.39, P = 0.03). Erythrocyte linoleic acid (18:2n-6) was not significantly correlated with ACC mI (r = −0.11, P = 0.57) or reaction time (r=+0.12, P = 0.54).

Discussion

Based on our preclinical observation that low cortical DHA status was associated with lower mI concentrations in the rat medial prefrontal cortex,19 we hypothesized that low erythrocyte DHA status would be associated with lower cortical mI concentrations in healthy developing children. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that mI concentrations were significantly lower in the ACC of low-DHA subjects compared with high-DHA subjects. Consistent with a deficit in ACC functional integrity,39–41 subjects in the low-DHA group had slower reaction times on the CPT-IP compared with the high-DHA group. Among all subjects, erythrocyte DHA was positively correlated with ACC mI, and both erythrocyte DHA and ACC mI were inversely correlated with reaction time. We additionally found that low-DHA subjects had lower NAA, Cho, and Cr concentrations in the ACC compared with the high-DHA subjects. There were no significant group differences in metabolite concentrations in either the L-DLPFC or R-DLPFC. Together, these data suggest that low erythrocyte DHA status is associated with reduced indices of metabolic function in the ACC and slower reaction time during sustained attention in male children.

The mean erythrocyte DHA composition exhibited by healthy male children in the high-DHA group is similar to that previously reported for a larger cohort of healthy adolescent and adult subjects residing in the USA,23 and approximately one-half that observed in healthy adolescents and adults residing in Japan.42 The mean erythrocyte DHA level observed in the low-DHA group was approximately one-half that observed in the high-DHA group, and this difference (−39%) is similar in magnitude to the erythrocyte DHA deficits previously observed in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) compared with healthy subjects.43–45 Consistent with prior studies,21–23 erythrocyte EPA and DHA compositions were positively correlated with habitual dietary fish intake frequency, which was significantly greater in the high-DHA group compared with the low-DHA group. Despite evidence for limited conversion of EPA to DHA in human subjects,46 erythrocyte EPA composition was also positively correlated with ACC mI, NAA, Cho, and Cr concentrations.

Consistent with the observation that low cortical DHA status was associated with lower mI concentrations in the rat medial prefrontal cortex,19 the present study found that lower DHA status was associated with lower mI concentrations in the ACC of healthy male children. Because mI concentrations are several-fold greater in astrocytes than neurons, the astrocyte mI pool is likely the major contributor to the mI peak acquired 1H MRS.15,16 It is relevant, therefore, that mI is metabolized from glucose via 1L-mI 1-phosphate synthase, and DHA is required for the normal growth and functional maturation of cortical astrocytes.47 Moreover, DHA-deficient rats exhibit reduced astrocyte-specific glucose transporter expression48 and glucose uptake49 in the frontal cortex. While we did not observe significant group differences in fasting plasma glucose levels, lower ACC mI concentrations in the low-DHA group may reflect reduced astrocyte-mediated glucose uptake. Together, these translational findings suggest that additional studies are warranted to further evaluate whether DHA status is associated with astrocyte-mediated vascular coupling in the ACC of developing children.

Subjects in the low-DHA group also exhibited significantly lower NAA concentrations in the ACC compared with the high-DHA group. NAA is primarily localized to neurons15,16 and is positively correlated with mitochondrial metabolism.17,18 In our rat 1H MRS study, cortical DHA status was not associated with basal NAA concentrations in medial prefrontal cortex.19 However, rodent studies have found that cortical NAA concentrations decrease in association with neuronal loss or dysfunction following acute ischemia50–53 and that higher DHA status is neuroprotective against ischemia-induced cortical atrophy.54,55 Moreover, previous 1H MRS studies have consistently observed lower NAA, Cho, and Cr in human cortical infarcts during the acute or subacute phase of ischemia.56–58 While the observed deficits in ACC NAA, Cho, and Cr in the low-DHA versus high-DHA group were smaller (~20%) than those commonly observed in cerebral infarcts following ischemia (~60%), the similar pattern may reflect a less severe disruption in ACC blood flow in the low-DHA group. It may be relevant, therefore, that structural MRI studies have found that greater habitual long-chain omega-3 fatty acid intake is associated with larger ACC gray matter volumes,59 and that greater ACC volumes are associated with faster reaction times.39 Together, these findings suggest that DHA status is positively correlated with ACC structural and functional integrity.

Although this study employed healthy, typically developing children, the present findings may take on additional significance in view of evidence from cross-sectional studies that ADHD patients exhibit erythrocyte DHA deficits,43–45 smaller ACC volumes,60 and reduced ACC activation during performance of different cognitive tasks.61–63 Additionally, ADHD patients commonly exhibit slower mean reaction times during the performance of sustained attention tasks.64 Moreover, compared with healthy subjects, patients with major depressive disorder exhibit erythrocyte32 and postmortem ACC65 DHA deficits, significant reductions in ACC mI and NAA concentrations and ACC cortical thickness,66 and reduced ACC activation during the performance of attention tasks.67 These associations suggest that low erythrocyte DHA status may represent a modifiable risk factor for progressive deficits in ACC functional and structural integrity in these psychiatric disorders.

In summary, the present 1H MRS data support the hypothesis that low-DHA status is associated with deficits in cortical metabolism in developing children, as evidenced by lower mI, NAA, Cho, and Cr concentrations in the ACC of low-DHA versus high-DHA groups. While it is not currently known why DHA status was more closely associated with the ACC versus DLPFC metabolite concentrations, it may reflect regional differences in metabolic demands as evidenced in part by greater mI levels in the ACC versus R/L-DLPFC. Nevertheless, this finding represents an important extension of our preclinical observation that low cortical DHA status was associated with lower mI concentrations in rat medial prefrontal cortex.19 Future prospectives are warranted to determine whether increasing DHA status through dietary supplementation can increase indices of ACC metabolism and functional integrity in developing children, and whether early DHA intervention is protective against the structural and functional ACC deficits observed in patients with psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institute of Health grants MH083924 to R.K.M., and DK59630 to P.T., and an investigator-initiated research grant from Martek Biosciences Corporation to R.K.M. Martek did not have any role in the design, implementation, analysis, and interpretation of the research. R.K.M. received investigator-initiated research funding from Martek Biosciences Inc., the Inflammation Research Foundation, Janssen, NARSAD, NIA, and NIMH, and is a consultant for the Inflammation Research Foundation. S.M.S. has received research grant support from Eli Lilly, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Nutrition 21, Repligen, NIDA, NIAAA, NARSAD, Thrasher Foundation, and is a consultant for Pfizer. M.P.D. has received research grant support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Johnson and Johnson, Shire, Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Repligen, Somerset, Sumitomo, Thrasher Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, and is a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, France Foundation, Kappa Clinical, Pfizer, Medical Communications Media, Shering-Plough. C.M.A. has received research grant support from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Johnson and Johnson, Shire, Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Repligen, Somerset, and is a consultant for AstraZeneca and Janssen.

Footnotes

None of the other authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Carver JD, Benford VJ, Han B, Cantor AB. The relationship between age and the fatty acid composition of cerebral cortex and erythrocytes in human subjects. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNamara RK, Liu Y, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P. The aging human orbitofrontal cortex: decreasing polyunsaturated fatty acid composition and associated increases in lipogenic gene expression and stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;78:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clandinin MT, Chappell JE, Leong S, Heim T, Swyer PR, Chance GW. Intrauterine fatty acid accretion rates in human brain: implications for fatty acid requirements. Early Hum Dev. 1980a;4:121–129. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(80)90015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martínez M, Mougan I. Fatty acid composition of human brain phospholipids during normal development. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2528–2533. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clandinin MT, Chappell JE, Leong S, Heim T, Swyer PR, Chance GW. Extrauterine fatty acid accretion in infant brain: implications for fatty acid requirements. Early Hum Dev. 1980b;4:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(80)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giedd JN, Lalonde FM, Celano MJ, White SL, Wallace GL, Lee NR, et al. Anatomical brain magnetic resonance imaging of typically developing children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:465–447. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher O, Burden MJ, Muckle G, Saint-Amour D, Ayotte P, Dewailly E, et al. Neurophysiologic and neurobehavioral evidence of beneficial effects of prenatal omega-3 fatty acid intake on memory function at school age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1025–1037. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson SE. Early determinants of development: a lipid perspective. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1523S–1529S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27113G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drover JR, Hoffman DR, Castañeda YS, Morale SE, Garfield S, Wheaton DH, et al. Cognitive function in 18-month-old term infants of the DIAMOND study: a randomized, controlled clinical trial with multiple dietary levels of docosahexaenoic acid. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNamara RK, Carlson SE. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in brain development and function: potential implications for the pathogenesis and prevention of psychopathology. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:329–349. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan AS, Astwood JD, Gautier S, Kuratko CN, Nelson EB, Salem N., Jr Effects of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on neurodevelopment in childhood: a review of human studies. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helland IB, Smith L, Saarem K, Saugstad OD, Drevon CA. Maternal supplementation with very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and lactation augments children’s IQ at 4 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:39–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karr JE, Alexander JE, Winningham RG. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cognition throughout the lifespan: a review. Nutr Neurosci. 2011;14:216–225. doi: 10.1179/1476830511Y.0000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohlboeck G, Glaser C, Tiesler C, Demmelmair H, Standl M, Romanos M, et al. LISAplus Study Group. Effect of fatty acid status in cord blood serum on children’s behavioral difficulties at 10 y of age: results from the LISAplus Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1592–1599. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.015800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D. Multinuclear NMR studies on the energy metabolism of glial and neuronal cells. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:289–298. doi: 10.1159/000111347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin JL, Bollard M, Nicholson JK, Bhakoo K. Spectral profiles of cultured neuronal and glial cells derived from HRMAS (1)H NMR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:375–384. doi: 10.1002/nbm.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates TE, Strangward M, Keelan J, Davey GP, Munro PM, Clark JB. Inhibition of N-acetylaspartate production: implications for 1H MRS studies in vivo. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1397–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciccarelli O, Toosy AT, De Stefano N, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Miller DH, Thompson AJ. Assessing neuronal metabolism in vivo by modeling imaging measures. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15030–15033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3330-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara RK, Able JA, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Lindquist DM. Perinatal omega-3 fatty acid deficiency selectively reduces myo-inositol levels in the adult rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo 1H-MRS study. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:405–411. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800382-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara RK. Deciphering the role of docosahexaenoic acid in brain maturation and pathology with magnetic resonance imaging. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.03.011. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao J, Schwichtenberg KA, Hanson NQ, Tsai MY. Incorporation and clearance of omega-3 fatty acids in erythrocyte membranes and plasma phospholipids. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2265–2272. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.072322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fekete K, Marosvölgyi T, Jakobik V, Decsi T. Methods of assessment of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status in humans: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:2070–2084. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27230I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sands SA, Reid KJ, Windsor SL, Harris WS. The impact of age, body mass index, and fish intake on the EPA and DHA content of human erythrocytes. Lipids. 2005;40:343–347. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-1392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor WE, Neuringer M, Lin DS. Dietary effects on brain fatty acid composition: the reversibility of n-3 fatty acid deficiency and turnover of docosahexaenoic acid in the brain, erythrocytes, and plasma of rhesus monkeys. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:237–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNamara RK, Sullivan J, Richtand NM. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency augments amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in adult mice: prevention by chronic lithium treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fristad MA, Glickman AR, Verducci JS, Teare M, Weller EB, Weller RA. Study V: Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (ChIPS): psychometrics in two community samples. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1998;8:237–245. doi: 10.1089/cap.1998.8.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crovitz HF, Zener K. A group-test for assessing hand- and eyedominance. Am J Psychol. 1962;75:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benisek D, Bailey-Hall E, Oken H, Masayesva S, Arterburn L. 93rd Annual AOCS Meeting. Canada: Montreal, Quebec; 2002. Validation of a simple food frequency questionnaire as an indicator of long chain omega-3 intake; p. S96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler CM, Sax KW, Holland SK, Schmithorst V, Rosenberg L, Strakowski SM. Changes in neuronal activation with increasing attention demand in healthy volunteers: an fMRI study. Synapse. 2001;42:266–272. doi: 10.1002/syn.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNamara RK, Able JA, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Eliassen J, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation increases prefrontal cortex activation during sustained attention in healthy boys: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1060–1067. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman brief intelligence test. 1st ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Selective deficits in erythrocyte docosahexaenoic acid composition in adult patients with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metcalfe LD, Schmitz AA, Pelka JR. Rapid preparation of fatty acid esters from lipids for gas chromatographic analysis. Anal Chem. 1966;38:514–515. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J-H, Garwood M, Menon R, Adriany G, Andersen P, Truwit CL, et al. High contrast and fast three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging at high fields. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:308–312. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruetter R, Boesch C. Fast, noniterative shimming of spatially localized signals. In vivo analysis of the magnetic field along axes. J Magn Reson. 1992;96:323–334. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tkac I, Staruck Z, Choi IY, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1 ms echo time. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:649–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<649::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Provincher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentration from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hetherington HP, Mason GF, Pan JW, Ponder SL, Vaughan JT, Twieg DB, et al. Evaluation of cerebral gray and white matter metabolite differences by spectroscopic imaging at 4.1 T. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:565–571. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casey BJ, Trainor R, Giedd J, Vauss Y, Vaituzis CK, Hamburger S, et al. The role of the anterior cingulate in automatic and controlled processes: a developmental neuroanatomical study. Dev Psychobiol. 1997;30:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naito E, Kinomura S, Geyer S, Kawashima R, Roland PE, Zilles K. Fast reaction to different sensory modalities activates common fields in the motor areas, but the anterior cingulate cortex is involved in the speed of reaction. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1701–1709. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paus T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:417–424. doi: 10.1038/35077500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ItomuraM, Fujioka S, Hamazaki K, Kobayashi K, Nagasawa T, Sawazaki S, et al. Factors influencing EPA+DHA levels in red blood cells in Japan. In Vivo. 2008;22:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen JR, Hsu SF, Hsu CD, Hwang LH, Yang SC. Dietary patterns and blood fatty acid composition in children with attention- deficit hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colter AL, Cutler C, Meckling KA. Fatty acid status and behavioural symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: a case-control study. Nutr J. 2008;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens LJ, Zentall SS, Deck JL, Abate ML, Watkins BA, Lipp SR, et al. Essential fatty acid metabolism in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:761–768. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brenna JT, Salem N, Jr, Sinclair AJ, Cunnane SC International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids, ISSFAL. Alpha-linolenic acid supplementation and conversion to n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;80:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joardar A, Sen AK, Das S. Docosahexaenoic acid facilitates cell maturation and beta-adrenergic transmission in astrocytes. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:571–581. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500415-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pifferi F, Roux F, Langelier B, Alessandri JM, Vancassel S, Jouin M, et al. (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid deficiency reduces the expression of both isoforms of the brain glucose transporter GLUT1 in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:2241–2246. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.9.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ximenes da Silva A, Lavialle F, Gendrot G, Guesnet P, Alessandri JM, Lavialle M. Glucose transport and utilization are altered in the brain of rats deficient in n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1328–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bjartmar C, Kidd G, Mörk S, Rudick R, Trapp BD. Neurological disability correlates with spinal cord axonal loss and reduced N-acetyl aspartate in chronic multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demougeot C, Marie C, Giroud M, Beley A. N-acetylaspartate: a literature review of animal research on brain ischaemia. J Neurochem. 2004;90:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malisza KL, Kozlowski P, Peeling J. A review of in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy of cerebral ischemia in rats. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:487–496. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-2-3-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woo CW, Lee BS, Kim ST, Kim KS. Correlation between lactate and neuronal cell damage in the rat brain after focal ischemia: an in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic (1H-MRS) study. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:344–350. doi: 10.3109/02841850903515395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belayev L, Khoutorova L, Atkins KD, Bazan NG. Robust docosahexaenoic acid-mediated neuroprotection in a rat model of transient, focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:3121–3126. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.555979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blondeau N, Widmann C, Lazdunski M, Heurteaux C. Polyunsaturated fatty acids induce ischemic and epileptic tolerance. Neuroscience. 2002;109:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duijn JH, Matson GB, Maudsley AA, Hugg JW, Weiner MW. Human brain infarction: proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 1992;183:711–718. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.3.1584925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lanfermann H, Kugel H, Heindel W, Herholz K, Heiss WD, Lackner K. Metabolic changes in acute and subacute cerebral infarctions: findings at proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1995;196:203–210. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.1.7784568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Federico F, Simone IL, Lucivero V, Giannini P, Laddomada G, Mezzapesa DM, et al. Prognostic value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:489–494. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conklin SM, Gianaros PJ, Brown SM, Yao JK, Hariri AR, Manuck SB, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acid intake is associated positively with corticolimbic gray matter volume in healthy adults. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Semrud-Clikeman M, Pliszka SR, Lancaster J, Liotti M. Volumetric MRI differences in treatment-naive vs. chronically treated children with ADHD. Neurology. 2006;67:1023–1027. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237385.84037.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the counting stroop. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1542–1552. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith AB, Taylor E, Brammer M, Halari R, Rubia K. Reduced activation in right lateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate gyrus in medication-naïve adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during time discrimination. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:977–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamm L, Menon V, Ringel J, Reiss AL. Event-related FMRI evidence of frontotemporal involvement in aberrant response inhibition and task switching in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1430–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000140452.51205.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Epstein JN, Hwang ME, Antonini T, Langberg JM, Altaye M, Arnold LE. Examining predictors of reaction times in children with ADHD and normal controls. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16:138–147. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conklin SM, Runyan CA, Leonard S, Reddy RD, Muldoon MF, Yao JK. Age-related changes of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the anterior cingulate cortex of individuals with major depressive disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Järnum H, Eskildsen SF, Steffensen EG, Lundbye-Christensen S, Simonsen CW, Thomsen IS, et al. Longitudinal MRI study of cortical thickness, perfusion, and metabolite levels in major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:435–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Halari R, Simic M, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos A, Cleare A, Brammer M, et al. Reduced activation in lateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate during attention and cognitive control functions in medication-naïve adolescents with depression compared to controls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:307–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]