Abstract

Objective

Second generation antipsychotics captured the majority of the US antipsychotic market shortly after their introduction. Little is known about how second generation antipsychotics diffused in other countries with different health systems. The objective was to describe trends in antipsychotic use in the US and France from 1998 to 2008.

Methods

After presenting a brief background section on pharmaceutical policies in France and the US, descriptive data on quarterly prescriptions dispensed between 01/1998–09/2008 for oral antipsychotics from Xponent™ for the US, and sales recorded in the GERS database for France are presented. Trends in the share of antipsychotic use for first vs. second generation antipsychotics, and in ingredient-level of second generation antipsychotics use are reported.

Results

In the US, between 1998 and 2008, total antipsychotic use increased by 78%. Total use was consistently higher in France despite a 9% decrease during the period. By 2008, second generation antipsychotics represented 90% of the antipsychotic US market vs. only 40% in France. However, average annual growth rates in second generation antipsychotics use were similar in the two countries. In France, there was a steady increase in use of all but one second generation antipsychotic; whereas trends in the use of newer drugs varied substantially by drug in the US (e.g. use of olanzapine decreased after 2003 whereas use of quetiapine increased).

Conclusions

These results highlight markedly divergent trends in the diffusion of new antipsychotics in France and the US. Some of these differences may be explained by differences in health systems, while others may reflect physicians’ preferences and norms of practice.

The antipsychotic market in the US is dominated by second generation antipsychotics. Seven new drugs introduced between 1989 and 2006 quickly took over 90% of the market for antipsychotics and also expanded the total number of users of antipsychotic medication, with a substantial portion of expanded use owing to off-label indications (1–3). The rapid diffusion of second generation antipsychotics has been controversial in light of evidence of increased metabolic risks (4, 5), and their significantly higher costs relative to first generation antipsychotics (6–8).

Other countries have also seen significant increases in use of more costly second generation antipsychotics (9) (10–13), however, few studies have compared trends in the use of antipsychotics in the US and other countries. We compared trends in use of antipsychotics in the US with that of France for two reasons. First, according to the World Health Organization, France has the highest performing health system (14). Second, physicians in the US and France had access to a somewhat similar list of approved second generation antipsychotics but differed with respect to reimbursement policy, use of cost-sharing, and other functions.

This paper examines trends between1998 and 2008. We present trends in use overall, by class (first vs. second generation antipsychotics) and by product. To provide some context for our findings we briefly present background on health system features in the two countries that may influence medication utilization. While a full examination of the impact of these features on antipsychotic diffusion is beyond the scope of this paper we offer some hypotheses in our discussion section as to how antipsychotic use may be shaped by health system and other factors. We also provide information on the drugs available (i.e., approved by regulators) for use in both countries.

Background on the French and US Health Systems

Health systems support the development and appropriate diffusion of technology through their regulatory approval process, reimbursement policy, post-marketing surveillance of drug safety and provision of safety information to clinicians (Table 1). More detailed overviews of the French system have been published elsewhere (15, 16). Both pharmaceutical systems have similar drug approval processes, pharmacovigilance systems, and offer good coverage for low-income and elderly populations. Conversely, the universality and comprehensiveness of health insurance benefits, and policies regarding drug pricing, and drug promotion regulations differ dramatically between the two countries.

Table 1.

Comparison of US and French pharmaceutical systems

| USA | France | |

|---|---|---|

| Drug approval | ||

| Agency | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | French Drug Agency (ANSM*), European Medicine Agency (EMA) or other European Drug Agency |

| Criteria | Efficacy, safety, product quality | Efficacy, safety, product quality |

| Timing of market launch post-approval | Immediate | Delay (on average 1 year) to allow reimbursement and price decisions |

| Coverage | ||

| Formulary | Varies by payer and plan | National decision by French Ministry for Health |

| Level of coverage (share of cost covered by payer) | Varies by plan, and within plan by drug | National decision by French Ministry for Health according to the severity of disease and value of the drug |

| Price paid to manufacturer | Varies by drug and plan | Nationally set, varies by drug |

| Out-of-pocket cost | Varies by payer and drug 100% of the drug cost for the uninsured (16% of the US population in 2010) | Copayment level varies by therapeutic class (0, 35, 65, 85% of the drug cost). Patients registered with a chronic condition or with a supplemental insurance (94%) typically have no out-of-pocket costs for drugs, but for a deductible of €0.50 per drug package (up to €50 per year) |

| Pharmacovigilance | ||

| Adverse drug reactions collection | Voluntary reporting system | Voluntary reporting. “Noxious and unintended” adverse drug reactions must be reported to ANSM |

| Safety warnings | Public health advisories Safety alerts ‘Dear healthcare provider’ letters |

Various public communications (“mise au point”, “point d’information”) ‘Dear healthcare provider’ letters |

| Type of Label change | Black box warning | Inserted into monograph sections |

| Labelling changes specific to antipsychotic Metabolic risk of second generation antipsychotics |

September 2003 |

None |

| Second generation antipsychotics in dementia | April 2005 | March 2004 |

| First generation antipsychotics in dementia | June 2008 | December 2008 |

| Promotion of prescription drugs | ||

| Direct-to-consumer | Permitted | Banned |

| Drug samples | Permitted | Very restricted |

| To physicians | Regulated | Regulated |

| Physicians per 1 pharmaceutical representative in 2006 (37) | 7.4 | 8.9 |

| Off-label use | ||

| Status | Allowed, although may be restricted by some payers (e.g., prior authorization for antipsychotic use in children) | Allowed if evidence-based and no other alternative |

ANSM: Agence nationale de sécurité des médicaments, formerly known as Afssaps (Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé)

Drug approval and marketing

Approval of new drugs is based on the same criteria in both countries: drug quality, efficacy and safety. However, whereas drugs are typically marketed by manufacturers shortly after approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US, French commercialization awaits price-setting and reimbursement decisions made by separate agencies.

Coverage, payment and pricing

The US system lacks universal coverage, with approximately 49.9 million uninsured individuals in 2010 (17). Insured individuals obtain their coverage through commercial insurers (often employer-sponsored) or through public sources such as Medicare or Medicaid. Adults with severe mental disorders are more likely than those without such disorders to be uninsured (21.0% vs.16.5%), and, when insured, to receive coverage through Medicare or Medicaid (18). In contrast, France mandates enrollment in its health system that includes prescription drug benefits.

Systems for determining reimbursement prices for prescription drugs also differ greatly between the two countries. In the French ambulatory care setting, drug prices are set nationally through negotiation between the health authorities and pharmaceutical firms, and depend on the drug’s innovation (19, 20). Prices paid in the US for drugs vary by payer.

In the US, each payer takes a different approach to coverage of medications including antipsychotics. For example, Medicare requires the plans with which it contracts to cover ‘all or substantially all’ antipsychotics (21). Similarly, the majority of Medicaid programs do not restrict coverage of antipsychotic medications, although some states do impose prior authorization requirements on some (22). Other third party payers may limit coverage of or impose higher cost-sharing for some antipsychotics.

In France, all approved antipsychotics are reimbursed. Under a general rule, patients must pay 35% of the drug cost. However, in practice, few patients pay this share because pharmacy copayments are generally covered by the patient’s supplemental insurance (and 94% had such an insurance in 2008) (23). In addition, patients with ‘chronic psychiatric conditions’ are offered full coverage for healthcare costs related to their chronic disease.

In the US, patient out-of-pocket cost varies by payer and drug. Patients enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries eligible for low-income subsidies face little to no out-of-pocket cost (24). For other Medicare beneficiaries, costs vary widely (22). Commercially insured patients spent on average $46 for a brand-name second generation antipsychotic and $12 for a generic out of pocket each month in 2010 (25). Last, uninsured patients are responsible for the full cost of drugs and large cost differences exist between first generation antipsychotics and most second generation antipsychotics (7).

In France, there is usually no out-of-pocket cost associated with antipsychotic medications apart from a €0.50 deductible per package of drugs purchased (up to a limit of €50 per year). Thus, patients do not spend more for branded or non-preferred drugs over generics as they typically do in the US.

Pharmacovigilance

After drugs have been approved, both the US FDA and French ANSM (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament,) may issue safety warnings as evidence emerges on a drug’s risk profile. The FDA may require labeling changes to be printed in black box warnings or added to the drug’s monograph. In France the new safety information is added to the drug’s monograph and patient information leaflet found in every drug package.

Information concerning the risks of antipsychotics has been handled differently by the two countries’ regulatory agencies. In September 2003, the US FDA issued a warning about the metabolic risks of second generation antipsychotics. No such warning has been issued in France. Both countries’ regulatory agencies issued warnings about increased mortality risk with second generation antipsychotics in demented older adults (in March 2004 in France and April 2005 in the US) that were later expanded to include all antipsychotics in 2008.

Promotion

Promotion to healthcare professionals is regulated in both countries. Promotional materials should be consistent with drug labels and ‘not be false or misleading’; in particular promoting off-label use is forbidden. Drug samples and direct-to-consumer promotion of prescription drugs are permitted in the US but are very restricted in France.

Materials and methods

Data sources

For the US, the data were collected from prescriptions dispensed for oral antipsychotics from IMS Health’s Xponent™ database. Xponent™ directly captures over 70% of all U.S. prescriptions filled in retail pharmacies and utilizes a patented, proprietary projection methodology to represent 100% of prescriptions filled in these outlets. We obtained monthly data on all oral antipsychotic prescriptions that were filled from January 1st 1998 – September 30th 2008 by patients of a 10% random sample of US physicians whose patients filled at least one prescription for an antipsychotic over the period. To extrapolate to all US physicians, we multiplied the prescriptions observed in our dataset by 10.

French prescription fills for oral antipsychotics were extracted from the GERS (Groupement pour l’élaboration et la réalisation de statistiques) database that collects sales to community pharmacies for all pharmaceutical products in France from 1998–2008.

Drugs

Antipsychotics were identified by an anatomical therapeutical and chemical (ATC) classification code starting with ‘N05A’ (excluding lithium N05AN). In some analyses, we report product-specific use among the SGAs available in one or both countries by the end of the study period.

Use of injectable antipsychotics was not included as they are mainly administered in hospitals or physicians’ offices and thus not recorded in our databases.

Analysis

We combined all drug formulations at the ingredient-level and report quarterly market shares or rates of use. For both data sources, we converted drug quantities into a monthly unit of treatment (i.e., quantity needed for 30 days of treatment regardless of strength). For the US, we assume a prescription equaled a 30-day supply. While this might underestimate the total number of prescriptions if a substantial number are filled for a 90-day supply in mail order pharmacies, we do not expect mail order use to vary by class or product. Furthermore, antipsychotics are highly likely to be filled for a 30-day supply because of dispensing limits imposed by most of state Medicaid programs (24), financing a majority of antipsychotics (21).

We converted the French data from number of packages sold each quarter into monthly supplies. For second generation antipsychotics, packages of 30 or 60 tablets of any strength corresponded to a monthly supply (assuming daily intake and that a dispensed package corresponded to a monthly prescription). However, as first generation antipsychotics’ packages are frequently dispensed for quantities other than a month’s supply (i.e., 20 or 50 tablets), we used 2006 IMS estimates of mean tablets used per day for commonly used FGAs to calculate average monthly supplies (26).

To determine population-based rates of antipsychotic use we calculated the number of monthly treatments per 1,000 inhabitants using yearly estimates of population size from the US Census Bureau and its French equivalent (the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques).

Results

Antipsychotic drugs available in each country

More first generation antipsychotics were approved and marketed in France than in the US (15 vs. 11, respectively) during the study period, and the specific drugs available differed, with only 4 first generation drugs (chlorpromazine, haloperidol, pimozide and loxapine) available with oral forms in both countries. By 2008, more second generation antipsychotics were available in the US than in France (7 vs. 5) (Table 2). Four drugs were available in both countries: clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine and aripiprazole. Amisulpride, the first second generation antipsychotic introduced in France, is not commercialized in the US, whereas quetiapine, available since 1997 in the US, was not approved until 2010 in France. On average, second generation antipsychotics were launched 2.1 years (range [18–32] months) earlier in the US than in France.

Table 2.

Availability and labeled indications of oral second generation antipsychotics in the US and in France*

| USA | France | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approval date |

Indications | Approval date |

Marketing date |

Indications | |

| Paliperidone | 12/2006 | Schizophrenia | 06/2007 | - | |

| Aripiprazole | 11/2002 09/2003 09/2004 03/2005 11/2007 10/2007 02/2008 11/2009 |

Schizophrenia Maintenance treatment in schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in BDI Preventive treatment in BDI Major depressive disorder (adjunct) Schizophrenia in children 13–17 yo Acute manic or mixed episodes in BD in children 10–17 yo Irritability in autistic disorder in children 6–17 yo |

06/2004 03/2008 03/2008 |

06/2004 | Schizophrenia in adults and adolescents 15 yo and older Acute treatment of manic episodes in BD Maintenance treatment in BD |

| Ziprasidone | 02/2001 06/2002 08/2004 11/2009 |

Schizophrenia Acute agitation in schizophrenic patients Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in BDI Maintenance treatment in BDI (adjunct) |

- | - | Special authorization (‘autorisation temporaire d’utilisation’) since 2007 |

| Quetiapine | 09/1997 01/2004 01/2004 01/2004 |

Schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic episodes in BDI Acute treatment of depressive episodes in BD Maintenance treatment in BDI |

11/2010 11/2010 11/2010 11/2010 11/2010 |

10/2011 | Schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic episodes in BD Acute treatment of depressive episodes in BD Maintenance treatment in BD Major depressive disorder (adjunct) |

| Olanzapine | 09/1996 03/2000 01/2004 12/2003 03/2009 12/2009 |

Schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in BDI (monotherapy or in combination 07/2003) Maintenance treatment in BDI Depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder with fluoxetine Severe depression (with fluoxetine) Schizophrenia or acute manic or mixed episodes in BD in children 13–17 yo |

09/1996 06/2002 10/2003 |

06/1999 | Schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic episodes in BD Maintenance treatment in BDI |

| Risperidone | 12/1993 03/2002 12/2003 08/2007 10/2006 |

Schizophrenia Maintenance treatment in schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in BD I Schizophrenia and BD in children 13–17 years old Irritability associated with autistic disorder in children |

05/1995 08/2006 08/2006 07/2008 |

02/1996 | Schizophrenia Acute treatment of manic episodes in BD Aggressiveness in children 5yo and older with mental retardation Aggressiveness in patients with dementia |

| Clozapine | 09/1989 | Treatment resistant schizophrenia | 06/1991 | 11/1991 | Treatment resistant schizophrenia Psychotic disorders in Parkinson’s disease |

| Amisulpride | - | - | 01/1986 | 03/1991 | Schizophrenia |

only the second generation antipsychotics approved in at least one of the two countries before September 2008 are presented in this table. Unless otherwise stated, the indication is approved for adults only.

Italicized indications are the indications approved in only one of the two countries.

Abbreviations: BD: bipolar disorder, BDI: bipolar I disorder, yo: years old

The extension of second generation antipsychotics’ labels to cover additional indications also occurred sooner in the US than in France, and, in general, drugs had a greater number of indications in the US (Table 2).

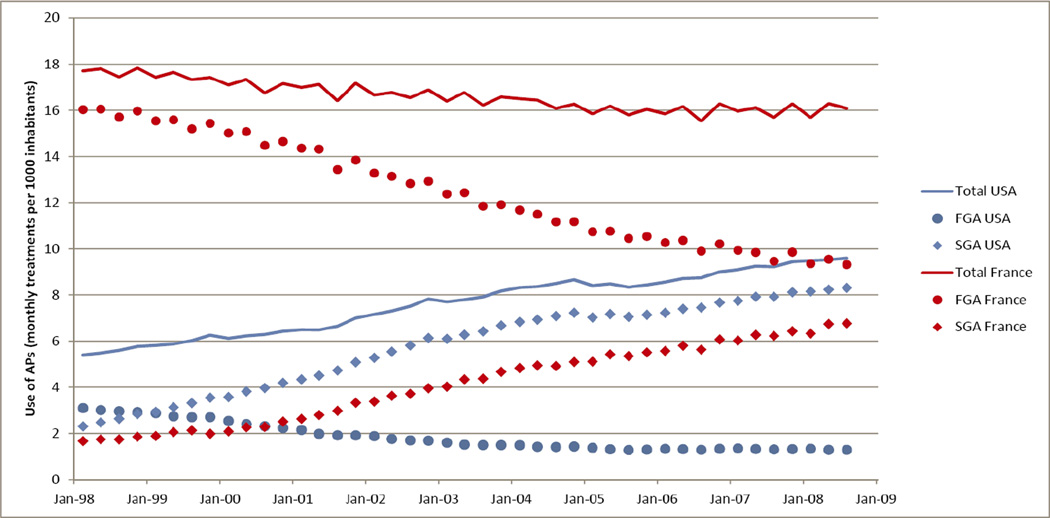

Trends in total antipsychotic use

From 1998 to 2008, the two countries saw different trends in total use (Figure 1). In the US, total antipsychotic use per 1,000 increased by 78%, while in France, it declined slightly by 9%. Yet, the overall level of antipsychotic use was consistently higher in France than in the US during the study period although the gap narrowed, from use in France being more than 3-fold higher in 1998 to less than twice as high in 2008.

Figure 1.

Trends in total antipsychotic, first generation and second generation antipsychotic use in the US and in France

Data for the USA: IMS Xponent™, Data January 1998–September 2008, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved

Data for France: GERS database 1998–2008

Abbreviations: FGA: first generation antipsychotics, SGA: second generation antipsychotics

First-generation vs. second-generation antipsychotics

In 2008, first generation antipsychotics represented 60% of the antipsychotic market compared to only 10% in the US (Figure 2). Indeed, second generation antipsychotics had captured a majority of the market for antipsychotics in the US by 1999. However, the mean annual growth rate in second generation antipsychotic use did not significantly differ between the two countries: 12.7% (se=0.028) in the US vs. 13.9% (se=0.025) in France (p=0.77).

Figure 2.

Evolution of first and second generation antipsychotic market shares in the US and in France

Data for the USA: IMS Xponent™, Data January 1998–September 2008, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved

Data for France: GERS database 1998–2008

Abbreviations: FGA: first generation antipsychotics, SGA: second generation antipsychotics

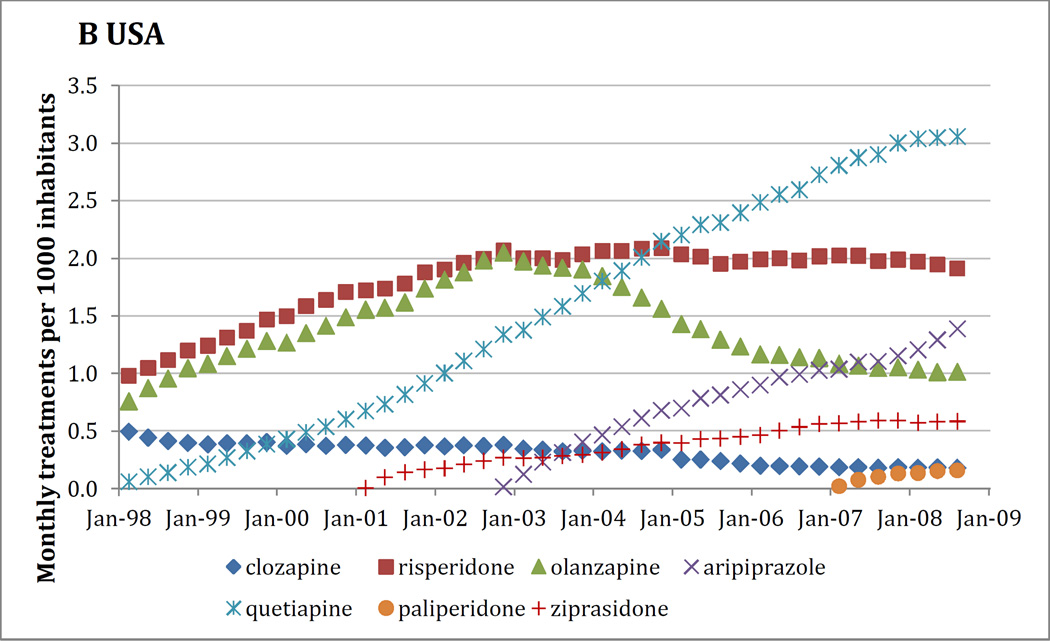

Trends in the use of specific second generation antipsychotics

Trends in product-level use of second generation antipsychotics also followed different patterns (Figure 3). In France, there was a steady increase in use of all newer drugs but amisulpride. Trends in use of the second generation antipsychotics varied substantially by drug in the US where use of clozapine and olanzapine decreased, and risperidone’s leveled off. Even several years after their commercialization and adoption by physicians, use of quetiapine and aripiprazole in the US have seen changes in use: a recent slowing down for quetiapine after a rapid increase in use and a sharp increase for aripiprazole (for example, + 5% and +25% respectively between 2007 and 2008).

Figure 3.

Use of the specific second generation antipsychotics in France (fig 3.A) and in the US (fig 3.B)

Data for the USA: IMS Xponent™, Data January 1998–September 2008, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved

Data for France: GERS database 1998–2008

From 1998 to 2003, France and the US had nearly equivalent levels and upward trends in use of risperidone and olanzapine. After 2003, this increasing trend continued in France, while in the US there was a steep decrease in olanzapine use and stabilization in risperidone use. In 2008, olanzapine accounted for only 12% of the US second generation antipsychotic market, down from 33% in 1998. Opposite trends in clozapine use were observed in the US (decreasing use) and in France (increasing use) although the level of use was low in both countries with shares of 8.7% of the second generation antipsychotic market in France and 2.2% in the US.

In 2008, the US market was slightly less concentrated in the top two drugs. US market leaders were quetiapine with 37% of prescriptions, and risperidone with 23% of use. In contrast, in France, olanzapine and risperidone shared equally approximately 70% of the second generation antipsychotic market.

Discussion

Our study presents three main findings. First, the two countries had divergent trends in antipsychotic use overall, with use per population increasing in the US and declining in France, where the initial level of use was higher. Second, we found large differences between the two countries in the market shares of first and second generations of antipsychotics. By 2008, first generation antipsychotics accounted for only 10% of antipsychotic use in the US while it still made up the majority of use in France. Finally, the product-level market shares for second generation antipsychotics showed different patterns, with the most notable difference in olanzapine’s share of use in the two countries.

The difference in absolute rates of overall antipsychotic use between the two countries is notable. However, because the data available to us were drawn using different sampling strategies we are unable to determine whether these rates are truly different, perhaps due to differences in medication access and affordability, or whether they are an artifact of the way we measured use. As a result we focus more on the divergent trends between the two countries.

Physicians in the US were much more rapid to shift toward use of newer over older antipsychotics than were physicians in France. Due to the huge price differences between first and second generation antipsychotics during the study period (differences that will narrow with the launch of generic second generation antipsychotics), the rapid adoption of newer drugs by US physicians had important economic consequences for payers, particularly Medicare and Medicaid which finance the majority of antipsychotic prescriptions (21).

Physicians’ prescribing of antipsychotics is likely influenced by patients’ clinical characteristics which we were unable to measure. Prescribing is also influenced by physician preferences. The long clinical tradition of combining two first generation antipsychotics (one mainly sedative and one more active on positive symptoms of schizophrenia) in France (27, 28) may not have existed in the US and may explain the higher use of first generation drugs in France than in the US. But the difference in the speed with which second generation antipsychotics captured the antipsychotic market in the two countries may also have been influenced by health system factors, some of which we briefly reviewed. For example, the slower adoption of new second generation antipsychotics in France may be explained by the 2.1-year delay in drug approval. The higher use of second than first generation antipsychotics in the US may also be due in part to the availability of more second generation antipsychotics and the number of indications for which manufacturers sought regulatory approval. Likewise the higher use of first generation antipsychotics in France may also reflect the greater number of first generation drugs available there.

Other findings may not have been predicted based on an assessment of health system differences alone. For instance, there is substantial evidence that choice of medication class is responsive to relative out-of-pocket price (29). Based on this factor alone, one might have expected greater use of first generation antipsychotics in the US, where there is a steeper gradient in cost-sharing between generic and brand name drugs than in France where most patients face no copay for antipsychotics.

US and French regulatory agencies and physicians appear to have responded differently to information regarding the comparative-effectiveness (30, 31) and safety of second generation antipsychotics. The dramatic decrease in olanzapine use in the US beginning in 2003 coincided with an FDA warning in that year on the metabolic effects of new antipsychotics, along with a consensus statement published shortly thereafter ranking olanzapine as having high metabolic risk (32). In response to these concerns, some Medicaid state programs placed restrictions on second generation use after the warnings (22, 33). In contrast, the French drug regulatory agency issued no such warning and did not place any market restrictions on drugs. In addition to differences in the actions of the regulatory agencies, it is possible that French and American physicians differ in their perception of antipsychotic risks. Perceptions of American physicians may have been shaped by the extensive publicity surrounding US lawsuits against olanzapine’s manufacturer (34).

Our study has some limitations. First, this descriptive paper cannot generate causal estimates of the relationships between features of the health system and trends in antipsychotic use. Second, the data for the two countries come from different sources: prescriptions (written and filled) from a random sample of US physicians and sales in the ambulatory care market in France. To compare use between the two countries, we used the most comparable unit available from both sources: monthly treatments. However, to convert the number of sold packages in France to the number of monthly treatments, we had to make assumptions about the average daily dose for first generation antipsychotics as packages are not standardized for monthly treatments. However, while this may lead to some error in differences between countries in first generation antipsychotic use, we do not expect this measurement error to change over time and therefore it cannot explain differences in trend. In addition, unlike US data, French sales capture prescriptions from hospitalists for outpatients and most of the consumption of patients living in nursing homes which are more likely to be first generation antipsychotics in France (i.e. use of low-potency antipsychotics). Thus, it is possible that the use of first generation antipsychotics in France may have been overestimated relative to that of the US. Last, we did not record the use of long-acting or other injectable antipsychotics. Hence we were not able to explore differences in the use of the entire class of antipsychotics. The use of long-acting antipsychotics has been reported to be similar for patients with schizophrenia in the US (26%) (35) and in France (21%) (36) in the early 2000’s and thus should not affect the comparisons.

Conclusions

The diffusion of second generation antipsychotics clearly followed different patterns in the US and France both in terms of their share of the total antipsychotic market as well as individual product market share within second generation drugs. Some of these differences appear to be consistent with health system differences between the two countries such as the timing of drug approval, and the issuance of safety warnings, although these influences need to be further explored. Other differences between the two countries may reflect physicians reaching different conclusions about the comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotics.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gallini was supported by a scholarship from the University Hospital of Toulouse, France, and the Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques, Ministry for Health, France. Dr. Donohue and Dr. Huskamp were partially supported by grant R01MH093359 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Huskamp was also partially supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation investigator award in health policy research. Dr. Gallini’s access to data on antipsychotic utilization in France from Groupement pour l’Elaboration et la Réalisation de Statistiques was authorized under a contract with Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques within France’s Ministry for Health. Dr. Donohue and Dr. Huskamp obtained data on U.S. antipsychotic utilization from IMS Health. We are grateful to Hocine Azeni, MA, who provided expert statistical programming. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on Xponent information services data (1996–2008) obtained under license from IMS Health, Inc. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health, Inc., or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Footnotes

disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Adeline Gallini, University of Toulouse.

Haiden A. Huskamp, Harvard Medical School.

Julie M. Donohue, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- 1.Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2011;20:177–184. doi: 10.1002/pds.2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychiatric services. 2009;60:1175–1181. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie DL, Rosenheck R. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in medicaid. American Journal of Managed Care. 2012;18:e109–e117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorsey ER, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, et al. Impact of FDA black box advisory on antipsychotic medication use. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170:96–103. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrato EH, Dodd S, Oderda G, et al. Prevalence, utilization patterns, and predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy: experience in a multistate Medicaid population, 1998–2003. Clinical therapeutics. 2007;29:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Doshi JA. Policy implications of CATIE. Psychiatric services. 2008;59:695. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Doshi JA. Second-generation antipsychotics: cost-effectiveness, policy options, and political decision making. Psychiatric services. 2008;59:515–520. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguli R, Strassnig M. Are older antipsychotic drugs obsolete? British Medical Journal. 2006;332:1346–1347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7554.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdoux H, Tournier M, Begaud B. Antipsychotic prescribing trends: a review of pharmaco-epidemiological studies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121:4–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caceres MC, Penas-Lledo EM, de la Rubia A, et al. Increased use of second generation antipsychotic drugs in primary care: potential relevance for hospitalizations in schizophrenia patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:73–76. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes J, Prah P, Nazareth I, et al. Prescribing trends in bipolar disorder: cohort study in the United Kingdom THIN primary care database 1995–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prah P, Petersen I, Nazareth I, et al. National changes in oral antipsychotic treatment for people with schizophrenia in primary care between 1998 and 2007 in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2012;21:161–169. doi: 10.1002/pds.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu CS, Lin YJ, Feng J. Trends in treatment of newly treated schizophrenia-spectrum disorder patients in Taiwan from 1999 to 2006. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2012;21:989–996. doi: 10.1002/pds.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The World Health Report 2000. Health systems: improving performance. 2000 http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J, Faden L, Predaris S, et al. Patient access to pharmaceuticals: an international comparison. European Journal of Health Economics. 2007;8:253–266. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodwin VG. The health care system under French national health insurance: lessons for health reform in the United States. American journal of public health. 2003;93:31–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010. 2011 http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p60-239.pdf.

- 18.Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, et al. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:486–494. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drug price setting and regulation in France. 2008 http://www.irdes.fr/EspaceAnglais/Publications/WorkingPapers/DT16DrugPriceSettingRegulationFrance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Pen C. The drug budget silo mentality: the French case. Value in Health. 2003;6(Suppl 1):S10–S19. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.6.s1.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Zuvekas SH. Dual eligibles with mental disorders and Medicare part D: how are they faring? Health affairs. 2009;28:746–759. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polinski JM, Wang PS, Fischer MA. Medicaid's prior authorization program and access to atypical antipsychotic medications. Health affairs. 2007;26:750–760. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Complementary health insurance in France: Wide-scale diffusion but inequalities of access persist. 2011 http://www.irdes.fr/EspaceAnglais/Publications/IrdesPublications/QES161.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prescription drug coverage under Medicaid. 2008 http://aging.senate.gov/crs/medicaid16.pdf.

- 25.Lenderts S, Kalali AH. Average Out-of-Pocket Expenses Across Different Drug Categories and Commercial Third-Party Payers. Psychiatry. 2010;7:12–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avis sur les médicaments. http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_5267/actes-medicaments-dispositifs-medicaux?cid=c_5267. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovess V. The French Consensus Conference on long-term therapeutic strategies for schizophrenic psychoses. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 1995;30:49–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00794941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin K, Begaud B, Verdoux H, et al. Patterns of risperidone prescription: a utilization study in south-west France. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:202–206. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second-vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1) Archives of general psychiatry. 2006;63:1079–1087. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2004;65:267–272. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatric services. 2008;59:540–546. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey RK, Adams JB, Unger DM. Atypical antipsychotics: a case study in new era risk management. Journal of psychiatric practice. 2006;12:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi L, Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, et al. Characteristics and use patterns of patients taking first-generation depot antipsychotics or oral antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Psychiatric services. 2007;58:482–488. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blin P, Olie JP, Sechter D, et al. Neuroleptic drug utilization among schizophrenic outpatients. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2005;53:601–613. doi: 10.1016/s0398-7620(05)84740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.L'information des médecins généralistes sur le médicament. 2007 http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapport-spublics/074000703/0000.pdf. [Google Scholar]