Abstract

Higher alcohol consumption, even at moderate levels, has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in epidemiological studies. However, prior studies were conducted in mostly white populations. To assess the relationship of alcohol consumption to postmenopausal breast cancer risk in a multiethnic population of largely never, light, or moderate drinkers, we prospectively examined the association in 85,089 women enrolled in the Multiethnic Cohort in Hawaii and California. During a mean follow-up of 12.4 years, 3,885 incident invasive breast cancer cases were identified. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models, controlling for potential confounders. Higher alcohol consumption was associated with increased risk of breast cancer: compared to nondrinkers, HRs were 1.23 (95% CI: 1.06-1.42), 1.21 (95% CI: 1.00-1.45), 1.12 (95% CI: 0.95-1.31), and 1.53 (95% CI: 1.32-1.77) for 5-9.9, 10-14.9, 15-29.9, and ≥30 g/day of alcohol, respectively. The positive association was seen in African American, Japanese American, Latino, and white, but not Native Hawaiian, women, and in those with tumors that were both positive and negative for estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER/PR). This prospective study supports previous findings that light to moderate alcohol consumption increases breast cancer risk, demonstrates this association in several ethnic groups besides whites, independent of ER/PR status.

Keywords: alcohol, breast cancer, multiethnic population, prospective study

Introduction

Alcohol is a well-established risk factor for breast cancer.1-3 A systematic literature review conducted by the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research in 2008 reported a summary relative risk of 1.08 (95% CI: 1.05-1.11) per 10g/day increase, based on 13 prospective studies.4 More recent prospective studies in western countries confirmed that even moderate drinking was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.5-7 However, previous studies were mostly conducted in ethnically homogeneous, primarily white, populations and could not examine whether the association varies by race/ethnicity. In the present study, we investigated the association between alcohol consumption and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in a large multiethnic population comprised largely of women who never drank alcohol or did so only moderately, which allowed us to separate the analyses by ethnicity as well as hormone receptor status.

Material and Methods

Study population

The Multiethnic Cohort was established to study lifestyle, especially diet, and cancer and has been described in detail elsewhere.8 In brief, more than 215,000 adults aged 45-75 years entered the cohort by completing a 26-page mailed questionnaire in 1993-1996. Participants were mostly African Americans, Native Hawaiians, Japanese Americans, Latinos, and whites who were residents of Hawaii and California, mainly Los Angeles County. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Hawaii and the University of Southern California. Over 99,800 women were postmenopausal at baseline and eligible for the current analyses. Women who did not report their menopausal status but were older than 55 years at cohort entry were assumed to be postmenopausal and accounted for 8.7% of the eligible population. For the current analyses, we excluded women who were not from one of the five targeted racial/ethnic groups (n=6,443) and who had prior breast cancer based on questionnaire report or on information from tumor registry linkages (n=4,683). Additionally, women with invalid dietary information based on total energy intake or its components were excluded (n=3,673). Thus, a total of 85,089 women were included in the final analyses.

Assessment of alcohol consumption and other covariates

Dietary intake during the previous year at baseline was assessed by a self-administered quantitative food frequency questionnaire (QFFQ) with over 180 food items, including alcoholic beverages.8 The QFFQ queried average consumption of regular/draft beer, light beer, white/pink wine, red wine, and hard liquor with nine categories of frequency, ranging from “never or hardly ever” to “4 or more times a day,” and four portion sizes (≤1, 2, 3, and ≥4 cans/bottles/glasses/drinks). Daily intakes of nutrients and ethanol from the QFFQ were calculated using a food composition table that has been developed and maintained by the University of Hawaii Cancer Center for the Multiethnic Cohort Study.8 A calibration study was conducted and showed satisfactory correlations between the QFFQ and three 24-hour recalls for all ethnic and sex groups being studied.9 Correlations for alcohol intake were 0.56-0.88. In addition to the QFFQ, the baseline questionnaire contained questions about demographic factors, anthropometric measures, other lifestyle factors, medication use, medical history, and for women, reproductive history.

Breast cancer case identification

Incident cases of breast cancer were identified by linkage of the cohort to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries covering Hawaii and California. Because emigration outside the catchment area has been low (<5%), few incident cases are likely to have been missed. In addition, the cohort was linked to the Hawaii and California state death files and to the National Death Index file. Case and death ascertainment was complete through December 31, 2007. During the average follow-up period of 12.4 years, a total of 3,885 incident invasive cases were identified among the 85,089 postmenopausal women who were eligible for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Alcohol intake was categorized into 6 groups: nondrinkers (0 g/day), 0.1-4.9 g/day, 5-9.9 g/day, 10-14.9 g/day, 15-29.9 g/day, and ≥30 g/day. We used Cox proportional hazards models with age as the time metric to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of breast cancer and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All Cox models were adjusted for ethnicity as strata variables and age at cohort entry (continuous) as a covariate to account for any cohort effect. The multivariate models were additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (no, yes), education (up to 12 years, more than 12 years), body mass index (BMI: <25, 25–<30, ≥30 kg/m2), age at menarche (≤12, 13–14, ≥15 years), age at first live birth (no children, ≤20, 21–30, ≥31 years), number of children for parous women (1, 2–3, ≥4), age at and type of menopause (natural: age <45, 45–<50, 50–<55, ≥55 years; oophorectomy: age <45, 45–<50, ≥50 years; hysterectomy: age <45, 45–<50, ≥50 years), hormone replacement therapy (no current estrogen use, past estrogen use with or without progestin, current estrogen use without progestin, current estrogen use with past/current progestin), smoking status (never, former, current), physical activity (tertiles of METs/day) and energy intake (log transformed), with adjustment for missing values for any of the categorical variables. The proportionality assumption was tested by Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be valid. A Wald test was used to assess trend by entering the ethnicity-specific median values within the appropriate category as a continuous variable in the model. We examined whether the association of alcohol consumption with breast cancer risk varies by ethnicity using a Wald test of the cross-product terms of the trend variable and the subgroup membership variables. We also conducted analyses separately by estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR) status (ER+/PR+, ER+/PR-, and ER-/PR- cases; there were too few ER-/PR+ cases for meaningful analysis). Breast cancer cases not counted as events, such as ER-/PR- cases in the analysis of ER+/PR+ tumors, were censored at the age of diagnosis. A Wald test was used to test for heterogeneity across subtypes of cancer using competing risk methodology,10 where each subtype was a different event. Since alcohol is an established antagonist to folate status, we examined interaction between alcohol and folate intake in relation to breast cancer, by entering indicator variables for tertile of total folate intake and six categories of alcohol intake in the model. We also examined a possible nonlinear relation between alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk nonparametrically with restricted cubic splines.11 SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Of the postmenopausal women, 63% did not consume alcohol and 21% consumed less than 5 g per day (Table 1). White women tended to drink more alcohol, compared to Japanese American and Latino women. Women who had higher alcohol consumption were more educated, had lower BMI, were more likely to be smokers, and were more likely to use hormone replacement therapy, compared to those who had lower alcohol intake.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 85,089 postmenopausal women by alcohol consumption in the Multiethnic Cohort Study, 1993-1996.

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 0.1-4.9 | 5-9.9 | 10-14.9 | 15-29.9 | ≥30 | |

| No. of participants | 53935 | 18230 | 3817 | 2312 | 3518 | 3277 |

| Age at cohort entry (years) | 62.3 ± 7.9 | 60.5 ± 7.9 | 59.8 ± 8.0 | 61.1 ± 8.0 | 60.4 ± 8.1 | 61.2 ± 8.1 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| African Americans | 20.8 | 20.8 | 20.6 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 19.4 |

| Native Hawaiians | 6.7 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

| Japanese Americans | 33.6 | 18.9 | 11.1 | 13.4 | 9.5 | 6.6 |

| Latinas | 23.5 | 25.2 | 22.0 | 16.0 | 12.7 | 9.1 |

| Whites | 15.4 | 29.2 | 39.3 | 45.8 | 53.7 | 58.9 |

| Family history of breast cancer (%) | 11.5 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 11.5 |

| Education (>high school, %) | 44.2 | 57.4 | 59.9 | 63.3 | 66.9 | 65.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 5.9 | 26.3 ± 5.3 | 26.0 ± 5.3 | 25.3 ± 4.9 | 25.0 ± 4.8 | 24.9 ± 4.8 |

| Smoking status (%) | ||||||

| Never | 62.2 | 51.3 | 40.7 | 39.0 | 33.1 | 21.9 |

| Former | 26.6 | 33.9 | 38.9 | 40.9 | 42.2 | 43.2 |

| Current | 11.3 | 14.8 | 20.4 | 20.1 | 24.7 | 35.0 |

| Age at menarche (%) | ||||||

| ≤12 years | 48.2 | 48.8 | 49.1 | 45.4 | 49.9 | 49.4 |

| 13–14 years | 38.5 | 38.9 | 39.1 | 42.3 | 38.8 | 39.6 |

| ≥15 years | 13.4 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 11.3 | 11.0 |

| Age at first live birth (%) | ||||||

| No children | 11.5 | 13.1 | 14.5 | 16.0 | 16.3 | 18.4 |

| ≤20 years | 30.6 | 29.9 | 33.1 | 29.1 | 28.8 | 30.0 |

| 21–<31 years | 51.8 | 51.0 | 47.8 | 48.6 | 49.5 | 46.3 |

| ≥31 years | 6.2 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 5.3 |

| Number of children for parous women (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 16.6 | 15.5 | 16.1 |

| 2–3 | 46.9 | 50.4 | 51.2 | 51.2 | 54.6 | 54.6 |

| ≥4 | 41.5 | 36.3 | 34.1 | 32.3 | 29.9 | 29.3 |

| Use of hormone replacement therapy (%) | ||||||

| No current or past estrogen use | 49.5 | 41.7 | 38.8 | 40.0 | 37.9 | 39.7 |

| Past estrogen use with or without progesterone | 19.0 | 19.1 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 18.8 | 21.0 |

| Current estrogen-only use | 15.0 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 17.6 | 18.6 | 16.2 |

| Current estrogen use with past/current progesterone | 16.4 | 21.8 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 24.6 | 23.2 |

| Physical activity (METs/day) | 1.60 ± 0.26 | 1.59 ± 0.26 | 1.59 ± 0.27 | 1.61 ± 0.28 | 1.60 ± 0.27 | 1.58 ± 0.28 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1906 ± 946 | 1941 ± 935 | 2036 ± 986 | 1955 ± 900 | 1981 ± 879 | 2240 ± 987 |

| Total folate intake (DFE/day) | 657 ± 518 | 698 ± 538 | 697 ± 538 | 703 ± 534 | 676 ± 516 | 597 ± 462 |

MET, metabolic equivalent; DFE, dietary folate equivalents

Mean ± SD (all such values)

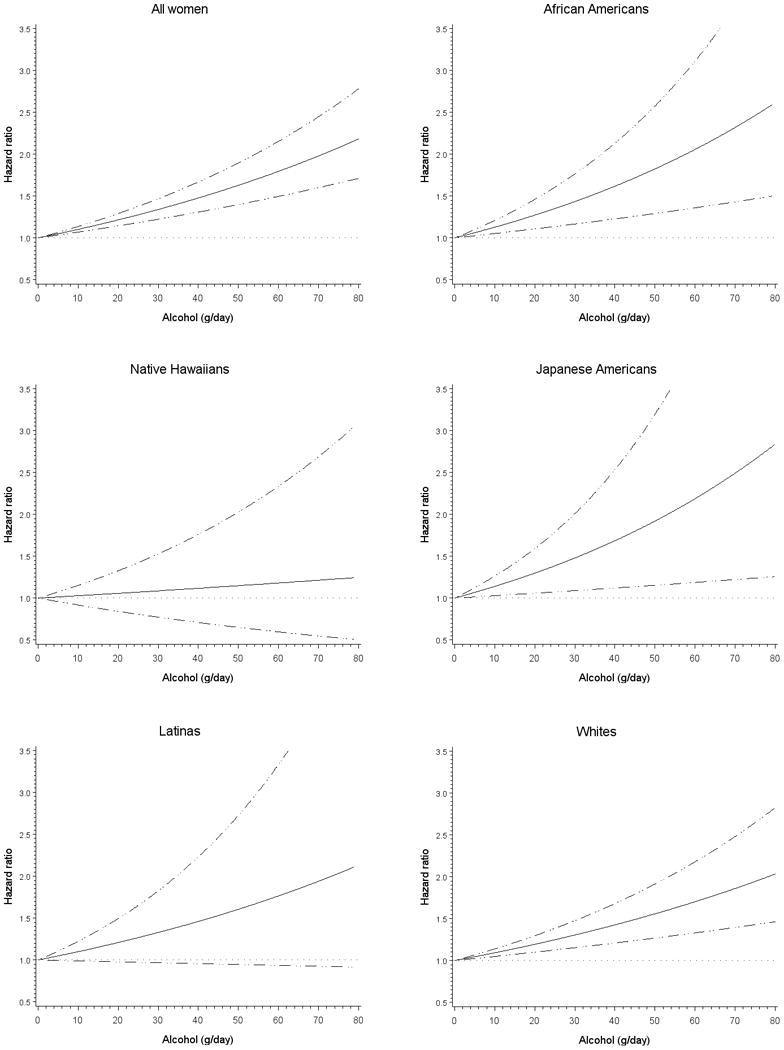

Compared to nondrinkers, women who had ≥5 g of alcohol a day showed an increase in risk of breast cancer and the multivariate HR for 10 g increase was 1.04 (95% CI: 1.02-1.06) (Table 2). The highest intake group of alcohol (≥30 g/d) showed a 53% increase in risk after adjustment for potential confounders. The HRs were very similar with those from the models minimally adjusted for age and race/ethnicity (data not shown). Also, a similar association was found in never smokers, which suggests no evidence of residual confounding by cigarette smoking (HR for 10 g increase = 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02-1.08). The increased risk with higher alcohol consumption was found in African Americans (HR for 10 g increase = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01-1.07), Japanese Americans (HR=1.08; 95% CI: 1.01-1.15), Latinas (HR=1.05; 95% CI: 1.00-1.11), whites (HR=1.04; 95% CI: 1.02-1.07), but not Native Hawaiians (HR=0.98; 95% CI: 0.91-1.05) who showed no significant association (P for heterogeneity across five ethnic groups = 0.37, P for heterogeneity between Native Hawaiians and the other groups = 0.060). As shown in Figure 1, the association between alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk was linear in women overall and in each ethnic group. The positive association between alcohol intake and breast cancer risk was consistently found across ER/PR status (P for heterogeneity = 0.98) (Table 2). We found no significant interaction between alcohol and folate intake in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer risk (P for interaction = 0.69). In analyses specific to alcohol type, the association was stronger for white wine (HR for 10 g increase = 1.11; 95% CI: 1.06-1.15), red wine (HR=1.08; 95% CI: 0.98-1.18), and hard liquor (HR=1.04; 95% CI: 1.01-1.07), while it was not statistically significant for beer (HR=1.02; 95% CI: 0.98-1.06; p for heterogeneity across four types <0.001).

Table 2. Risk of breast cancer according to alcohol consumption by race/ethnicity and hormone receptor status among postmenopausal women in the Multiethnic Cohort Study, 1993-2007.

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | P for trend | 10 g/day increment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 0 | 0.1-4.9 | 5-9.9 | 10-14.9 | 15-29.9 | ≥30 | |||

| All women | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 2342 | 802 | 207 | 126 | 181 | 227 | ||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 0.98 (0.91-1.07) | 1.23 (1.06-1.42) | 1.21 (1.00-1.45) | 1.12 (0.95-1.31) | 1.53 (1.32-1.77) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | ||||||||

| 0 | 0.1-4.9 | 5-9.9 | 10-29.9 | ≥30 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||||||

| African Americans | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 471 | 165 | 47 | 38 | 48 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 1.01 (0.84-1.21) | 1.46 (1.07-1.98) | 0.81 (0.58-1.13) | 1.89 (1.39-2.59) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | |

| Native Hawaiians | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 231 | 55 | 19 | 20 | 12 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 0.76 (0.56-1.02) | 1.04 (0.65-1.68) | 0.90 (0.57-1.44) | 0.83 (0.46-1.50) | 0.59 | 0.98 (0.91-1.05) | |

| Japanese Americans | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 886 | 183 | 24 | 34 | 18 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 1.07 (0.91-1.25) | 1.22 (0.81-1.83) | 1.17 (0.83-1.66) | 1.89 (1.17-3.04) | 0.011 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) | |

| Latinas | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 380 | 148 | 33 | 34 | 16 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 1.00 (0.83-1.22) | 1.27 (0.88-1.81) | 1.30 (0.91-1.85) | 1.68 (1.01-2.79) | 0.022 | 1.05 (1.00-1.11) | |

| Whites | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 374 | 251 | 84 | 181 | 133 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 0.99 (0.84-1.17) | 1.19 (0.93-1.51) | 1.29 (1.08-1.56) | 1.43 (1.16-1.76) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02-1.07) | |

| ER/PR status* | ||||||||

| ER+PR+ | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 1077 | 337 | 85 | 159 | 106 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 0.92 (0.81-1.04) | 1.14 (0.91-1.42) | 1.35 (1.13-1.61) | 1.61 (1.30-2.00) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.03-1.08) | |

| ER+PR- | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 193 | 85 | 26 | 25 | 21 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 1.27 (0.98-1.65) | 1.89 (1.24-2.89) | 1.11 (0.72-1.72) | 1.72 (1.06-2.79) | 0.054 | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | |

| ER-PR- | ||||||||

| No. of cases | 279 | 119 | 33 | 40 | 28 | |||

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (referent) | 1.18 (0.94-1.47) | 1.57 (1.08-2.27) | 1.24 (0.87-1.75) | 1.58 (1.04-2.38) | 0.025 | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | |

Adjusted for ethnicity, age at cohort entry, family history of breast cancer, age at first live birth, age at menarche, age and type of menopause, number of children, hormone replacement therapy, smoking status, education, physical activity, BMI, and energy intake.

P for heterogeneity = 0.37 for five ethnic groups, 0.060 for Native Hawaiians vs. the other groups, and 0.98 for three ER/PR status.

Figure 1.

Multivariate association between alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk overall and by race/ethnicity among postmenopausal women in the Multiethnic Cohort Study, 1993-2007. Association estimated by Cox regression based on restricted cubic splines. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals for adjusted estimates.

Discussion

In this large multiethnic population, alcohol consumption of ≥5 g/day was related to an increased risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. The increased risk with higher alcohol intake was consistently found in African American, Japanese American, Latino, and white, but not Native Hawaiian, women and appeared to be independent of ER/PR status.

Alcohol is a well-established risk factor for breast cancer, and recent large prospective studies confirmed earlier reports that even moderate consumption of alcohol was associated with breast cancer risk.5-7 Moderate drinking is defined as having up to 1 drink (14 grams of pure alcohol) per day for women.12 In the present study, an increased risk of breast cancer was statistically significant at these levels of consumption, supporting the previous findings from other cohorts, as well as in light drinkers at levels of consumption as low as 5 to 9.9 g/day. In this multiethnic population, Native Hawaiians did not show an increased risk with higher consumption of alcohol compared to non-drinkers, while a positive relationship was found in the other four ethnic groups. Native Hawaiians are a particularly interesting population with regard to breast cancer. In an earlier study, we showed that Native Hawaiian women have the highest incidence of breast cancer in the Multiethnic Cohort Study.13 Furthermore, whereas adjustment for most known risk factors for breast cancer largely accounted for differences in breast cancer incidence among the other four groups of the MEC, this adjustment only exaggerated the higher incidence in the Native Hawaiian women.13 In addition, we also had reported earlier that Native Hawaiian women had the highest circulating levels of androgens and estrogens and the lowest levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) of the five ethnic groups in the cohort.14 Taken together, these observations suggest that there may be some unique factors contributing to the risk of breast cancer in this population; further investigations to uncover these factors should be illuminating.

A meta-analysis of 4 prospective and 16 case-control studies concluded that alcohol consumption was associated with increased risks for ER+/PR+ and ER+/PR-, but not ER-/PR- tumors.15 Recent studies also supported the meta-analysis, reporting that alcohol use was more strongly associated with risk of hormone receptor-positive tumors.5,6,16 However, we did not find any indication of a varying alcohol-breast cancer association by hormone receptor status in our population. This finding suggests that the association between alcohol and the development of breast cancer is not fully explained by the ER-mediated action of estrogens, or that the association by receptor status is not consistent across ethnic groups.15 Since, however, our study had less statistical power to study the relationship by hormone receptor status than did the meta-analyses, the current finding should be considered with caution.

Several studies have reported that the detrimental effects of alcohol on breast cancer risk may be attenuated by folate. A review of 11 studies that examined the interaction between alcohol and folate intake concluded that the increased risk of breast cancer associated with moderate or high alcohol consumption may be reduced by adequate folate intake.17 However, most prospective studies published since that review found no significant interaction between folate and alcohol consumption in relation to breast cancer risk 5,18-23, although one study suggested that folate intake may modify the alcohol-breast cancer risk relationship.24 These findings are likely confounded by the folate fortification of grains in the US in 1998. The findings from our study did not support the interaction between folate and alcohol intake.

Our study has several strengths, including a prospective design, a large sample size of multiethnic women of light to moderate drinkers, a validated QFFQ, and other comprehensive information that enabled us to control for various confounding factors for breast cancer and to examine ethnic-specific associations. However, certain limitations of the study also need to be considered. Some measurement error in estimation of alcohol consumption by use of the QFFQ was inevitable. Since alcohol consumption was measured at baseline only, we were not able to examine lifetime consumption and timing of exposure to alcohol in relation to breast cancer. In addition, we had no information on drinking patterns such as heavy episodic or binge drinking, which may also affect the risk of breast cancer.6,25

In conclusion, our findings support the hypothesis that moderate alcohol consumption increases risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. We also found that light drinking may also be associated with higher risk and that the alcohol effect holds generally in four ethnic groups, African Americans, Japanese Americans, Latinas, and whites, but not in Native Hawaiians, independent of hormone receptor status.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health [R37 CA54281].

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- ER

estrogen receptor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- PR

progesterone receptor

- QFFQ

quantitative food frequency questionnaire

References

- 1.Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, van den Brandt PA, Folsom AR, Goldbohm RA, Graham S, Holmberg L, Howe GR, Marshall JR, Miller AB, Potter JD, Speizer FE, et al. Alcohol and breast cancer in women: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. JAMA. 1998;279:535–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Key J, Hodgson S, Omar RZ, Jensen TK, Thompson SG, Boobis AR, Davies DS, Elliott P. Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:759–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity,and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Systematic Literature Review Continuous Update Report. The associations between food, nutrition and physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. Washington DC: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lew JQ, Freedman ND, Leitzmann MF, Brinton LA, Hoover RN, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Park Y. Alcohol and risk of breast cancer by histologic type and hormone receptor status in postmenopausal women: the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:308–17. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2011;306:1884–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, Kan SW, Reeves GK, Brown A, Green J. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:296–305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Stram DO, Monroe KR, Earle ME, Nagamine FS. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:346–57. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stram DO, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Monroe KR, Park S, Henderson BE, Nomura AM, Earle ME, Nagamine FS, Kolonel LN. Calibration of the dietary questionnaire for a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:358–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therneau TM, Grambsh PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. 7th. Washington DC: U.S. Goverment Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Wilkens LR, Hankin JH, Feigelson HS, Wan PC, Stram DO, Nomura AM. Breast cancer in a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: risk factor-adjusted incidence in Japanese equals and in Hawaiians exceeds that in whites. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:795–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setiawan VW, Haiman CA, Stanczyk FZ, Le Marchand L, Henderson BE. Racial/ethnic differences in postmenopausal endogenous hormones: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1849–55. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki R, Orsini N, Mignone L, Saji S, Wolk A. Alcohol intake and risk of breast cancer defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status--a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1832–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li CI, Chlebowski RT, Freiberg M, Johnson KC, Kuller L, Lane D, Lessin L, O'Sullivan MJ, Wactawski-Wende J, Yasmeen S, Prentice R. Alcohol consumption and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer by subtype: the women's health initiative observational study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1422–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Wolk A. Folate and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:64–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruti SS, Ulrich CM, White E. Folate and one-carbon metabolism nutrients from supplements and diet in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:624–33. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy CM, Assaf A, Cyr M, Burkholder G, Coccio E, Rohan T, McTiernan A, Paskett E, Lane D, Chetty VK. Alcohol and folate intake and breast cancer risk in the WHI Observational Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:551–62. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0167-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Sun J, Gapstur SM. Folate and other one-carbon metabolism-related nutrients and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1708–15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Folate intake and risk of breast cancer by estrogen and progesterone receptor status in a Swedish cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3444–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tjonneland A, Christensen J, Olsen A, Stripp C, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ocke MC, Thiebaut A, Fournier A, Clavel-Chapelon F, et al. Alcohol intake and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:361–73. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki R, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Shimazu T, Tsugane S. Alcohol consumption-associated breast cancer incidence and potential effect modifiers: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:685–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai M, Minami Y, Kakizaki M, Kakugawa Y, Nishino Y, Fukao A, Tsuji I, Ohuchi N. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in Japanese women: the Miyagi Cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:817–25. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morch LS, Johansen D, Thygesen LC, Tjonneland A, Lokkegaard E, Stahlberg C, Gronbaek M. Alcohol drinking, consumption patterns and breast cancer among Danish nurses: a cohort study. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:624–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]