Abstract

Nanoparticle-based sensor arrays have been used to distinguish a wide range of biomolecular targets through pattern recognition. Such biosensors require selective receptors that generate a unique response pattern for each analyte. The tunable surface properties of gold nanoparticles make these systems excellent candidates for the recognition process. Likewise, the metallic core makes these particles fluorescence superquenchers, facilitating transduction of the binding event. In this report we analyze the role of gold nanoparticles as receptors in differentiating a diversity of important human proteins different, and the role of the polymer/biopolymer fluorescent probes for transducing the binding event. A structure-activity relationship analysis of both the probes and the nanoparticles is presented, providing direction for the engineering of future sensor systems.

Introduction

Nature has generated diverse mechanisms for sensing molecular systems and triggering appropriate responses. The majority of biological recognition processes occur via specific interactions such as antibody-antigen interactions.1 However, sensory processes such as taste and smell use an array of cross-reactive receptors that use differential binding for analyte identification. These receptors bind to their analytes through interactions that are selective rather than specific.2 Such array-based sensing platforms can be trained to create a response fingerprint for each analyte, enabling their detection and differentiation.3 The potential of this method has been demonstrated in numerous biomacromolecule sensing including peptides,4 proteins,5 amino acids,6,7 sugars,8 bacteria,9 and even mammalian cells.10,11 Likewise, a number of synthetic biomolecular platforms including porphyrin,12 oligopeptide functionalized resins,13 polymers,14 have been employed to create these sensor arrays.

Nanoparticles (NPs) provide a versatile scaffold for array-based sensing of biomolecules.15 Gold NPs (AuNPs) offer many advantages in terms of recognition and transduction of binding events.16 The surface of AuNPs can be decorated easily with various ligands of interest. Hence, physicochemical properties including charge, hydrogen-bonding ability, hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity and surface topology, can easily be modulated on the AUNP surface. AuNPs can be readily fabricated in sizes comparable with biomacromolecules, facilitating high affinity interactions.17 In addition, the extraordinary stability and high resistance to exchange by amines (e.g. lysine residues)18 provide stable platforms for recognition. Finally, the strong quenching ability of AuNPs19 provides facile transduction of the recognition process, making AuNPs attractive candidates for application in differential sensing.20

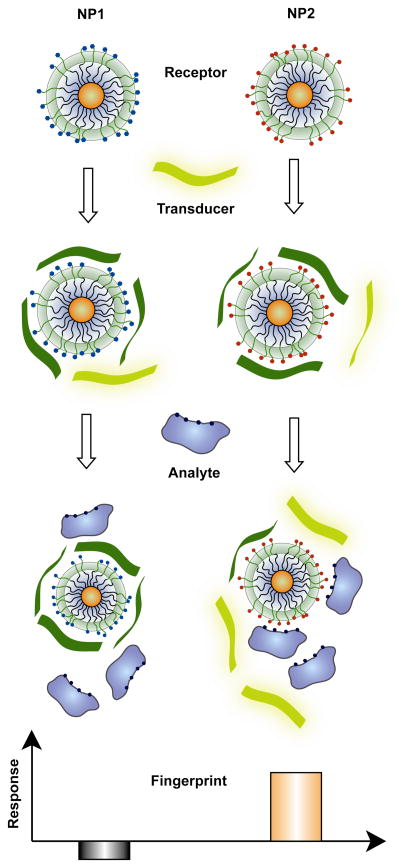

In our research, we have used arrays of AuNPs featuring different ligand structures at their surface to detect and differentiate a diversity of analytes. As shown in Figure 1, the sensor unit is formed by adding a fluorescent probe to a supramolecularly complimentary NP, turning off the probe fluorescence. When analytes are incubated with the NP-probe complexes, there is competitive binding between analyte and NP-probe complexes. Selective displacement of the probe from the particle by the analytes restores fluorescence, transducing the binding event in a “turn on” fashion. The NPs are chosen to possess different affinities for dissimilar analytes depending on the NP structure and analyte surfaces. As a result, each analyte generates a unique signature that allows differentiation and recognition.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of NP/transducer sensor-array. Each nanoparticle and fluorescent probes are mixed followed by incubation with analytes. Depending on the nanoparticle/probe/analyte competitive binding, “lighting up” or further quenching of fluorescence can be observed. Such fluorescence response patterns are distinct and characteristics of each analyte, allowing differentiation.

Our initial biosensing studies involved proteins identification employing AuNPs as the receptors and conjugated polymers as the transducer.14 Our strategy relied on the displacement of the fluorescent probe from the supramolecular complexes between cationic AuNPs and anionic polymers, generating distinct fluorescence response patterns. This system used six NPs, and was able to properly identify seven different proteins in buffer solution. Later studies showed that analogous arrays could differentiate cell state on the basis of cell surface properties.21 However, aggregation problems of the polymers restricted their applicability in complex matrices such as serum. To overcome this issue, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP) as the fluorophore, replacing the polymer transducer with a biopolymer analog. Not only that, the biocompatibility of the probe allowed us to use the system without affecting the target protein conformations. These GFP-AuNP sensor arrays were capable of differentiating bio-relevant changes (500 nM changes in 1 mM overall protein content) in human serum protein.22

Our efforts have concurrently been directed towards enhancing the stability and biocompatibility of synthetic polymers. Recently, we synthesized a new polymer specifically designed to avoid aggregation by introducing oligo(ethylene glycol) chains designed to prevent aggregation. This polymer was used with three nanoparticles to successfully differentiate twelve bacteria including three strains of the same species.23

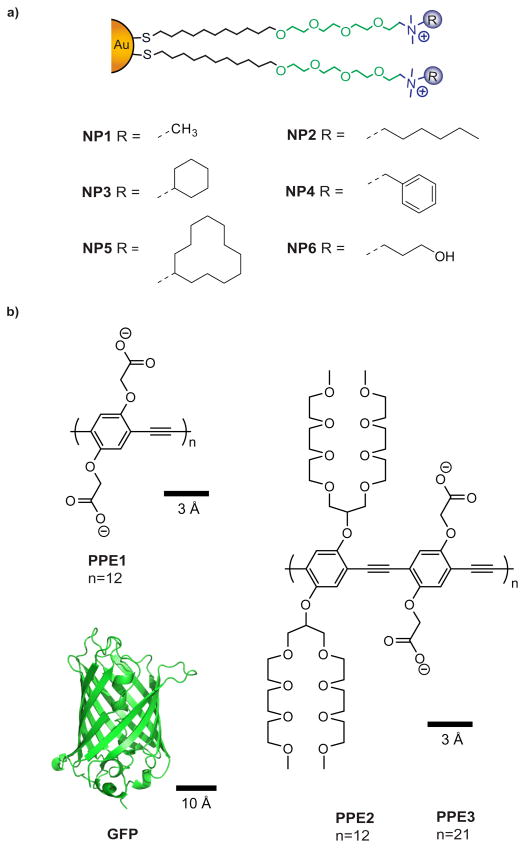

In this report, we analyze the structure-activity relationship of the particle-polymer/biopolymer sensing system, providing insight into how to enhance sensor efficiency. This study uses six AuNPs with variations in hydrophobicity, hydrogen bonding ability and aromatic recognition unit (Figure 2a). We analyzed the effect of structural variation and relative molar emissivity of the transducers using three fluorescent polymers (PPE1, PPE2, PPE3) and GFP as shown in Figure 2b.

Fig. 2.

a) Structure of the nanoparticles and ligands used in the current study, featuring an aliphatic interior, a tetra(ethylene glycol) layer and the head group responsible for analyte recognition. b) Molecular structures and size of the different fluorescent probes including the conjugated polymers (PPE1, PPE2, PPE3) and GFP.

Experimental section

Materials

The ligands (Figure 2) were synthesized according to previous reports24 starting with 11-bromoundecanol, triphenylmethanethiol, tetra(ethylene glycol) and the corresponding tertiary amines, each purchased from Sigma Aldrich. NP gold cores were synthesized according to literature procedure25 using 1-pentanethiol as the stabilizer, and purified by successive precipitation/redispersion cycles of the NPs in ethanol and acetone.

Place exchange reactions26 were performed to functionalize the surface of the NPs using the synthesized ligands, and the resulting cationic gold nanoparticles were purified by dialysis using a 10,000 MWCO membrane to remove the 1-pentanethiol/disulfide and the excess of ligand. TEM (core size), NMR (presence of free ligand), DLS (hydrodynamic size) and LDI-MS (purity) techniques were used to characterize the NPs.

Three different fluorescent polymers were synthesized and characterized according to literature procedures.27 GFP was expressed according to reported methodology,28 starting from cultures of a glycerol stock of GFP in BL21(DE3) that was grown overnight in culture media at 37°C. These initial cultures were then added to a Fernbach flask that contained culture media and the mixture was shaken until the optical density at 600 nm was ~0.6. GFP formation was then induced by adding isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, shaking at 28°C for three hours. The solution was centrifuged and the cells were resuspended, lysed and then the protein was purified using HisPur Cobalt columns and dialysis.

Sensor optimization

Nanoparticle titrations were performed to find the optimal nanoparticle/probe ratio for sensing purposes, measuring the change in fluorescence intensities after the addition of cationic nanoparticles (0–200 nM in 5mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4). The measurement wavelengths were 465nm for the polymers (λex 435nm) and 510nm for GFP (λex 495nm). All the values were normalized using a neutral noninteracting nanoparticle as control (gold core functionalized with a ligand lacking the amine head group) to subtract the effect of absorption effect of gold NP due to its optical properties. The curve fitting was done with Origin 8.0 using a previous reported algorithm29 to find the physicochemical parameters of the binding process, namely binding constant (Ks) and binding sites per nanoparticle (n). The ultimate nanoparticle/probe ratio was chosen to balance sensitivity and dynamic range.

Sensing studies

Fluorescence of the samples was measured in a M5 SpectraMax Molecular Devices plate reader instrument using 96 well black plates. A stock solution of the each fluorescent probe was prepared in 5mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 with a concentration that gave ~1000 a.u. of emission. This solution was then divided and nanoparticles added. The conjugates were added to microwell plate. After 15 minutes of incubation initial fluorescence was recorded, and 10μL of a solution of the analyte proteins (with absorbance of 0.005 at 280 nm, Table 1) was added. After 15 min additional incubation the final fluorescence intensity was determined.

Table 1.

Analytes properties and concentrations used in the study.

| Protein | M.W. (kDa) | Isoelectric Point | Charge at pH 7.4 | ε280 (M−1 cm−1) | Conc.(nM) A280=0.005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Serum Albumin | 69.4 | 5.2 | Negative | 38E+03 | 132 |

| Cytochrome c | 12.3 | 10.7 | Positive | 23E+03 | 216 |

| Acid Phosphatase | 110 | 5.2 | Negative | 26E+04 | 19 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 140 | 5.7 | Negative | 63E+03 | 80 |

| Hemoglobin | 64.5 | 6.8 | Neutral | 13E+04 | 40 |

| Lysozyme | 14.4 | 11.0 | Positive | 38E+03 | 132 |

| Ribonuclease A | 13.7 | 9.4 | Positive | 10E+03 | 500 |

| Myoglobin | 17.0 | 7.2 | Neutral | 14E+03 | 359 |

| Fibrinogen | 340 | 5.5 | Negative | 51E+04 | 10 |

| α-Antitrypsin | 52 | 4.6 | Negative | 28E+03 | 181 |

| Transferrin | 80 | 36.0 | Neutral | 11E+04 | 45 |

| Immunoglobulin G | 150 | 38.0 | Positive | 21E+04 | 24 |

For data analysis, the change in fluorescence was plotted against each descriptor to get the fingerprint patterns for all the analytes. The obtained data were analyzed by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) applying Mahalonobis clustering analysis, using the software Systat 11.30 Canonical score plots were obtained in order to parameterize each case, using the nanoparticle as predictors. A total of 12 different proteins were analyzed using 6 replicates in each case.

Results and discussions

Comparison of the fluorescent probes

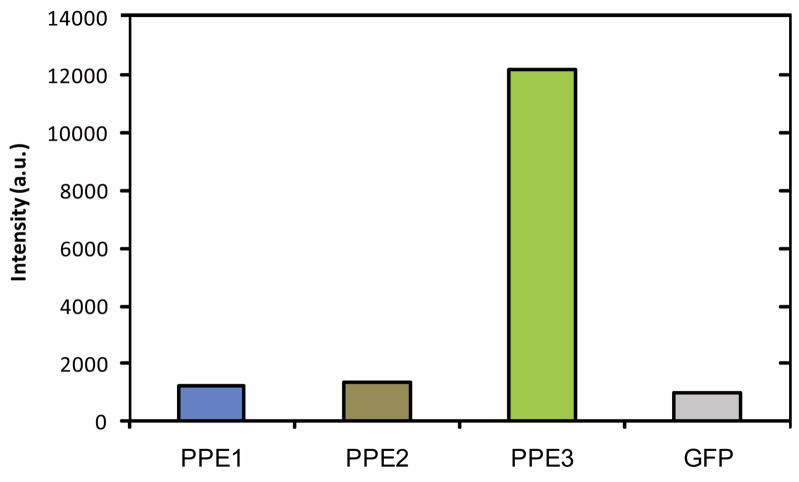

Emissivity is a key determinate of fluorescence sensor design, dictating fluorophore concentrations required for sensing.31 As shown in Figure 3, the fluorescence intensity of PPE1, PPE2 and GFP are similar at 50 nM. However, PPE3 shows a drastic increase in emission. This difference in molar emissivity can be explained by polymer structure and length. The extended conjugation of the aromatic rings of PPE3 provides the possibility of multiple fluorescent units along the chain of the polymer.32 Additionally, PPE3 carries more charges, potentially inhibiting self-quenching. For the below studies we employed concentrations of the probes that produced similar emission intensity (PPE1: 50nM, PPE2: 50nM, PPE3: 5nM, GFP: 150nM).

Fig. 3.

Relative molar emissivity of different fluorescent probes used in the study with a concentration of 50 nM.

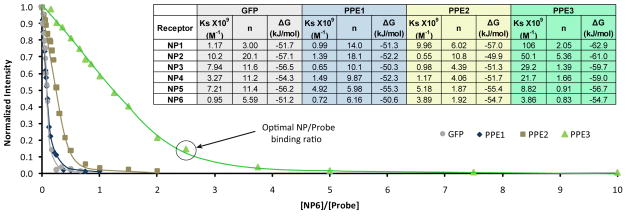

Next, we assessed the complexation between the fluorescent probes and the cationic NPs using fluorescence titrations. The fluorescence of GFP and the polymers were quenched significantly for all six AuNPs (Figure 4 and SI). The complex stability constants (KS) and association stoichiometries (n) obtained through nonlinear least-squares curve-fitting analysis are tabulated in Figure 4. The variation in complex stabilities and the binding stoichiometry demonstrate the significant effect of AuNP head groups in the NP-probe affinity. Difference in the molecular structure and properties of the transducers also play key role in the complex supramolecular interactions, as reflected in the parameters.

Fig. 4.

Titration curves of the different probes with NP6. The circle indicates the point of optimal NP/Probe binding ratio chosen. The table shows the thermodynamic parameters calculated for NPs against the fluorescent probes.

From the binding curves it is apparent that PPE3 binds to the NPs with higher affinity and lower stoichiometries than the other polymers or GFP due to the increased contact area and size of PPE3. In addition to the lower amount of polymer required, the optimum NP concentration ranged from 1–7 nM for PPE3 and 5–25 nM for the other probes, demonstrating that PPE3 allows a more parsimonious use of materials.

Finally, we investigated the ability of the sensor arrays to differentiate analytes. Twelve proteins with diverse structural features including molecular weight and isoelectric point (pI) were used as the target analytes (Table 1). In our protocol we used UV absorbance as a means of decoupling protein concentrations from sensor response. We used standard absorbance (A280 = 0.005) for the sensor studies, diluting stock solutions to obtained the desired levels. These protein solutions were added to the fluorescence-quenched supramolecular complexes using NP/probe ratios obtained from the titrations (Figure 4). The changes in fluorescence (Figure S5) upon addition of protein generate a pattern characteristic of the individual proteins. We used LDA to quantitatively differentiate the fluorescence response patterns. LDA is a statistical technique that maximizes the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance, allowing response patterns to be differentiated. The 72 training cases (12 proteins × 6 replicates) were efficiently clustered into 12 separate groups with 95% confidence ellipses using LDA. Distinction of the groups was reflected in the overall classification accuracy obtained from Jackknifed classification matrix.33

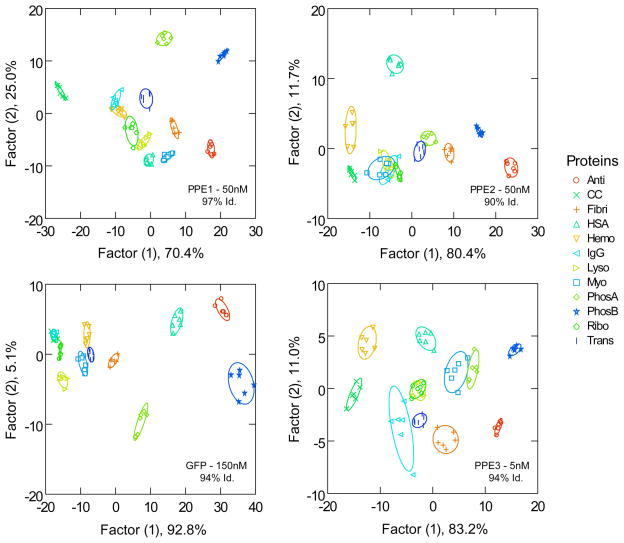

Distinct canonical score plots were obtained from LDA analysis for each transducer and the most significant scores are plotted in Figure 5. It is observed that the PPE1 and PPE2 show considerable differences in classification abilities in spite of their similar relative emissivities and size. In fact, PPE2 possesses the lowest identification efficiency among all the transducers. However, PPE3 features greater capability of differentiation, possibly due to higher binding affinity and molar emissivity. Although the classification accuracy of PPE3 is similar to PPE1, it possesses added advantages of biocompatibility and lack of aggregation in complex media. It is worth noting that PPE3 needs 10-fold less polymer concentration that the other two polymers, indicating much higher sensitivity.

Fig. 5.

Canonical score plots for the fluorescence patterns of the different probes as obtained from LDA use of six NP-probe complexes against twelve analyte proteins (analytes added in a concentration 10–500 nM, with absorbance of 0.005 at 280 nm). The 95% confidence ellipses for the each analyte, the concentration of the probe used and the percentage of identification accuracy are shown on the plots. Acronyms used: Anti=α-Antitrypsin, CC=Cytochrome c, Fibri=Fibrinogen, HSA=Human Serum Albumin, Hemo=Hemoglobin, IgG=Immunoglobulin G, Lyso=Lysozyme, Myo=Myoglobin, PhosA=Phosphatase acidic, PhosB=Phosphatase basic, Ribo=Ribonuclease A, Trans=Transferrin.

In the present study, we achieved high efficiency of identification of the analyte proteins using GFP as well as with PPE1 and PPE3. Compared to the other transducers, GFP shows higher dispersion of clustering on LDA analysis suggesting greater possibility of differentiating multiple analytes at the same time. However, GFP-based sensing required substantially more fluorophore and nanoparticle compared to PPE3.

Nanoparticle surface functionality: structure-activity relationships in sensing

One of the goals for array-based sensor design is maximal differentiation with the minimal number of sensing elements. The head groups of the ligands used in this study were designed to exhibit different physicochemical properties such as hydrophobicity, hydrogen-bonding sites, and π-stacking systems. The purpose of this structural diversity was to obtain clues about which interactions best generated selectivity in analyte binding. Insight into the nature of the multivalent interactions involved in the NP-protein interactions would help us designing appropriate NP surfaces with enhanced selectivity.34,35

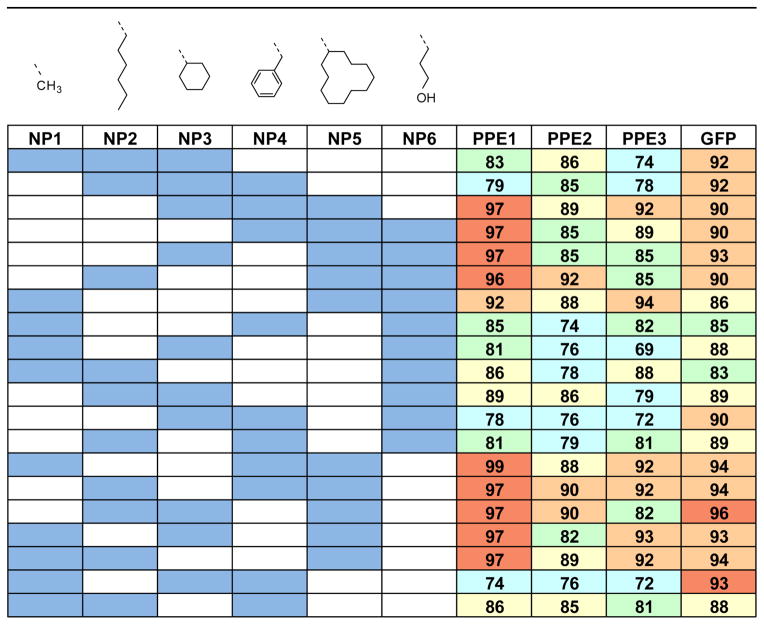

We used a Jackknifed classification matrix to determine which particles were most effective at analyte differentiation. When using only two NPs as predictors the classification is poor, with accuracy below 80%. With a number of combinations, however, three NPs could be used to differentiate all 12 proteins. The accuracy, however, varies depending on the nature of NPs, as evident from Figure 6. All possible combinations of three NPs presented in Figure 6 reveals that the hydrophobic NPs contribute more towards the discrimination of proteins irrespective of the transducer. In general, the combinations containing NP4 and NP6 show poorer differentiation grouping (e.g. NP2-NP4-NP6; NP1-NP4-NP6 combinations). Interestingly, NP5 appears to be highly effective at differentiating analytes, as all highly efficient sets contained this NP.

Fig. 6.

Jackknifed classification matrix for identification using selected combinations with three nanoparticles as predictors in LDA analysis. Combinations with hydrophobic changes on nanoparticle functionality show better identification accuracy.

Conclusions

In this study we demonstrate the versatility of AuNPs in array-based sensing, identifying twelve different proteins using a variety of polymer and biopolymer transducers. Of the transducers, PPE3 shows greatest sensitivity due to its higher intrinsic molar emissivity. The other polymers were equally effective in differentiation, and possess their respective advantages for sensing applications.

From our studies, we also determined some general guidelines for nanoparticle design. First, we found that hydrophobic particles were better able to discriminate among analyte proteins. Second, structure is important, as the cyclododecyl-terminated NP5 was a very effective partner in protein differentiation. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that through tuning of receptor and transducer structure highly effective array based sensors for proteins can be produced.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under Award DE-FG02-04ER46141, the National Science Foundation (NSF) Center for Hierarchical Manufacturing at the University of Massachusetts (NSEC, DMI-0531171), and the NIH (GM077173 and AI073425).

References

- 1.Raftos D, Raison RL. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:479–481. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert KJ, Lewis NS, Schauer CL, Sotzing GA, Stitzel SE, Vaid TP, Walt DR. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2595–2626. doi: 10.1021/cr980102w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umali AP, Anslyn EV. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang T, Edwards NY, Bonizzoni M, Anslyn EV. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11976–11984. doi: 10.1021/ja9041675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miranda OR, You CC, Phillips R, Kim IK, Ghosh PS, Bunz UHF, Rotello VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9856–9857. doi: 10.1021/ja0737927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folmer-Andersen JF, Kitamura M, Anslyn EV. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5652–5653. doi: 10.1021/ja061313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buryak A, Severin K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3700–3701. doi: 10.1021/ja042363v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JW, Lee JS, Chang YT. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:6485–6487. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duarte A, Chworos A, Flagan SF, Hanrahan G, Bazan GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12562–12564. doi: 10.1021/ja105747b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj A, Rana S, Miranda OR, Yawe JC, Jerry DJ, Bunz UHF, rotello VM. Chem Sci. 2010;1:134–138. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Boubbou K, Zhu DC, Vasileiou C, Borhan B, Prosperi D, Li W, Huang XF. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4490–4499. doi: 10.1021/ja100455c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldini L, Wilson AJ, Hong J, Hamilton AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5656–5657. doi: 10.1021/ja039562j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright AT, Anslyn EV. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:14–28. doi: 10.1039/b505518k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.You CC, Miranda OR, Basar Gider B, Ghosh PS, Kim I-B, Erdogan B, Krovi SA, Bunz UHF, Rotello VM. Nat Nanotech. 2007;2:318–323. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Marco M, Shamsuddin S, Razak KA, Aziz AA, Devaux C, Borghi E, Levy L, Sadun C. Int J Nanomed. 2010;5:37–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rana S, Yeh Y, Rotello VM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch I, Dawson KA. Nano Today. 2008;3:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nath S, Ghosh SK, Kundu S, Praharaj S, Panigrahi S, Pal T. J Nanoparticle Res. 2006;8:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan C, Wang S, Bazan GC, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6297–6301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132025100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miranda OR, Creran B, Rotello VM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:7138–736. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bajaj A, Miranda OR, Kim IB, Phillips RL, Jerry DJ, Bunz UHF, Rotello VM. Nat Acad Sci (USA) 2009;106:10912–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900975106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De M, Rana S, Akpinar H, Miranda OR, Arvizo RR, Bunz UHF, Rotello VM. Nat Chem. 2009;1:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nchem.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips RL, Miranda OR, You CC, Rotello VM, Bunz UHF. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2590–2594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu ZJ, Ghosh PS, Miranda OR, Vachet RW, Rotello VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14139–14143. doi: 10.1021/ja805392f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brust M, Walker M, Bethell D, Schiffrin DJ, Whyman R. Chem Comm. 1994:801–802. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Templeton AC, Wuelfing WP, Murray RW. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:27–36. doi: 10.1021/ar9602664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim IB, Phillips R, Bunz UHF. Macromolecules. 2007;40:5290–5293. [Google Scholar]

- 28.De M, Rana S, Rotello VM. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9:174–178. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips RL, Miranda OR, Mortenson DE, Subramani C, Rotello VM, Bunz UHF. Soft Matter. 2009;5:607–612. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SYSTAT11.0. SystatSoftware; Richmond, CA 94804, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu J, Li G, Qiin Y, Freeman WJ. Sensor Actuac B-Chem. 2007;125:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filatov I, Larsson S. Chem Phys. 2002;3:575–591. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurs PC, Bakken GA, McClelland HE. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2649–2678. doi: 10.1021/cr9800964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roan JR. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:248301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.248301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Tian S, Petros RA, Napier ME, Desimone JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11206–11313. doi: 10.1021/ja1043177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.