Summary

Background

A standard definition of pulmonary exacerbation based on signs and symptoms would be useful for categorizing cystic fibrosis (CF) patients and as an outcome measure of therapy. The frequently used definition of treatment with intravenous antibiotics varies with practice patterns. One approach to this problem is to use large data sets which include a patient’s signs and symptoms along with their clinician’s decision to treat with antibiotics for the diagnosis of pulmonary exacerbation. Previous analysis of such a data set, the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis (ESCF), found that new crackles, increased cough, increased sputum, and weight decline were the four clinical characteristics most strongly influencing providers to treat young CF patients for a pulmonary exacerbation. The objectives of this study were to confirm that these four characteristics influence the decision to treat with antibiotics for a pulmonary exacerbation in young CF patients; to evaluate their implications for future nutritional status and lung function; and to assess the effect of antibiotic treatment on these characteristic signs and symptoms.

Methods

This was an observational, longitudinal cohort study of clinical care in children less than 6 years old cared for at sites participating in ESCF.

Results

Using data from children not included in the previous ESCF study, we confirmed that these four characteristics were significantly associated with the likelihood of physicians prescribing antibiotics to treat a pulmonary exacerbation. The number of these characteristics present at a single clinic visit before age 6 predicted hospitalization rate over the next year, the weight-for-age z-score, and the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) percent predicted at age 7. Treatment with antibiotics was associated with a greater decrease in the proportion of children with crackles, cough, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa at a follow-up visit within 6 months.

Conclusions

New crackles, increased cough, increased sputum, and decline in weight percentile at a single clinic visit increase the risk of future malnutrition, hospitalization, and airflow obstruction in young children with CF. Treatment with antibiotics mitigates some of these signs and symptoms by the first follow-up visit. The presence of these four characteristic signs and symptoms is useful to define pulmonary exacerbations in young children with CF that respond to antibiotic treatment in the short term and influence long-term prognosis.

Keywords: cough, sputum, weight decline, crackles, cystic fibrosis

Introduction

Patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) follow a course of increasing airway obstruction during which patients experience intermittent acute exacerbations of this obstruction. Treatment of CF patients with antibiotics, especially intravenous (IV) antibiotics, is used in clinical trials as a sentinel event that defines such pulmonary exacerbations.1 Because practice patterns vary, the use of treatment to define a pulmonary exacerbation is likely to be imprecise.2,3 The development of an alternative definition of a pulmonary exacerbation in CF based on signs and symptoms rather than treatment remains a challenge, especially in young children for whom spirometric measurement of airway obstruction is unreliable.4

One approach to this problem is to use large data sets in which patients’ signs and symptoms are recorded along with their clinician’s decision to treat with antibiotics for the diagnosis of a pulmonary exacerbation. Previous analysis of the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis (ESCF)5 by Rabin et al6 found a limited number of signs and symptoms that were most closely associated with a clinical diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation. In the ESCF, when clinicians reported a new course of IV, inhaled, or oral quinolone antibiotics, they indicated whether it was for a “pulmonary exacerbation” or for “prophylaxis.” The patient’s signs and symptoms at the time of this encounter were also recorded. This enabled the determination of which signs and symptoms were most closely and independently related to the clinicians’ decision to treat for a “pulmonary exacerbation.” For CF patients under 6 years old, the major clinical signs and symptoms associated with treatment for a pulmonary exacerbation were 1) new crackles, 2) increased cough, 3) increased sputum, and 4) a relative decline of more than 45% in weight-for-age percentile.

Our objectives for this study were to establish the reproducibility of this association between the presence of these four characteristics and the treatment for the diagnosis of a pulmonary exacerbation in a different sub-population in the ESCF; to evaluate for the first time whether the presence of these characteristic signs and symptoms of pulmonary exacerbation at a single visit in young CF children had implications for future nutritional status, hospitalization, and airflow obstruction; and to assess the short-term effect of antibiotic treatment on these signs and symptoms.

Methods

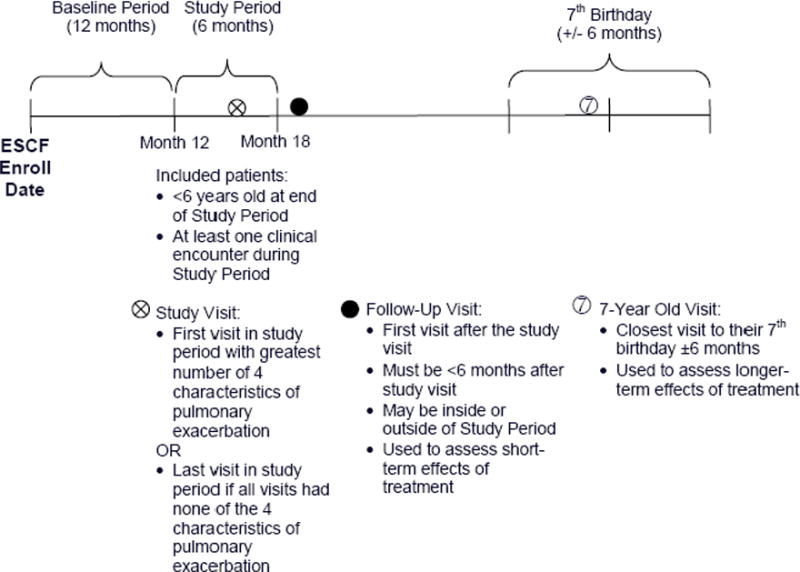

The ESCF is a prospective, longitudinal observational study of the clinical course of patients who received care at CF treatment sites in the United States and Canada.5 The study was approved by local institutional review boards and participants or their guardians provided informed consent. As had been done previously by Rabin et al,6 an 18-month observation period was used, consisting of a 12-month baseline period and a 6-month study period, beginning at the time of the patient’s enrollment into the ESCF (Figure 1). Of the 29,656 patients enrolled as of March 2003, we excluded those with missing or invalid enrollment dates and those for whom less than 30 months of data were available. Of the remaining 23,694 patients, we included patients who were less than 6 years old at the end of the study period, who had one or more clinical encounters between 12 and 18 months after enrollment, and for whom full data were available regarding the four above-mentioned characteristic signs and symptoms of a pulmonary exacerbation.6 To confirm the previously observed association between the number of characteristics present at the clinic visit and the percentage of CF patients less than 6 years old treated with antibiotics for a pulmonary exacerbation, we did a separate analysis on a subset of these CF patients enrolled since the study by Rabin.6

Figure 1.

Study timeline.

In the ESCF case report forms, clinicians recorded cough and sputum (none, occasional, or daily), crackles (present or absent), gender, date of birth, height, weight, and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) (in patients old enough to perform acceptable measurements).5 We evaluated the data from each patient at each clinic visit during the study period for the presence of these four characteristics of a pulmonary exacerbation: 1) new crackles (i.e., crackles present at any visit in the study period that were previously absent during at least one visit in the baseline period), 2) increased cough or 3) sputum (defined by an increase of one or more categories of “none,” “occasional,” and “daily” at any visit during the study period compared with best during the baseline period), and 4) a relative decline of more than 45% in the weight-for-age percentile at any visit during the study period compared with the best weight-for-age percentile in the baseline period. This 45% decline in weight-for-age percentile might seem quite large. For children in this age range, a patient’s absolute weight may actually increase between visits but at such a slow rate such that they drop, for example, from the 50th to the 25th weight-for-age percentile between visits. Rabin’s study showed that CF clinicians associated this amount of decline in weight gain as indicating a pulmonary exacerbation in this age group.6 Patients were categorized as having Pseudomonas aeruginosa if the organism was detected in their respiratory tract (throat, sputum, or bronchoalveolar lavage culture) at any time between enrollment and the study visit.

Patients were categorized into groups according to the presence of zero, one, two, three, or four of these clinical characteristics at any visit during the study period. If individuals had more than one visit during the study period, the first visit with the maximum number of observed characteristics was defined as their study visit. If patients had none of the characteristics, their last visit in the study period was used as their study visit.

Treatment was defined as any newly prescribed IV, inhaled, or oral quinolone antibiotic initiated between 7 days before and 28 days after the study visit. In ESCF, oral quinolone antibiotics were reported separately from other oral antibiotics because of their anti-pseudomonal activity. This antibiotic treatment may or may not have been accompanied by other therapies such as non-quinolone oral antibiotics, dornase alfa, oral or inhaled corticosteroids, or nutritional supplements.

To evaluate the short-term effects of treatment, we determined the proportion of patients with any crackles, cough, sputum, or wheeze (not necessarily as a new symptom or as an increased symptom) and P. aeruginosa at the first visit within 6 months following the study visit (the follow-up visit). We also evaluated the change in weight-for-age z-scores from the study visit to this follow-up visit. For the short-term effect of hospitalizations we determined the proportion of patients hospitalized during the 1-year baseline period and the 1-year follow-up period after baseline. Patients with three or four clinical characteristics were combined for this part of the analysis because the number of patients in these groups was small and their outcomes were similar.

In addition, we examined the association of the number of these clinical characteristics present at the study visit and treatment with the patient’s clinical status, as measured by the weight-for-age z-score and the FEV1 percent predicted, closest to and within 6 months before or after their seventh birthday.

χ2 tests were used to test the associations between categorical variables, and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) tests were used to evaluate trends in variables with multiple measures. The odds ratios for whether the likelihood of treatment differed by gender and by the presence of P. aeruginosa were calculated using logistic regression. Separately for each outcome, we used the CMH test to evaluate whether the change in proportion of patients who had crackles, cough, sputum, wheeze, and P. aeruginosa from study visit to follow-up visit differed by treatment, controlling for the number of clinical characteristics. Similar analysis was performed for hospitalizations for the baseline year and follow-up year. Analysis of variance was used to compare the change in weight-for-age z-score by treatment, controlling for the number of clinical characteristics. Because each of the pre-specified outcome signs and symptoms variables (crackles, cough, sputum, wheeze, P. aeruginosa, hospitalization, weight for age, and FEV1) was considered independently, the reported P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

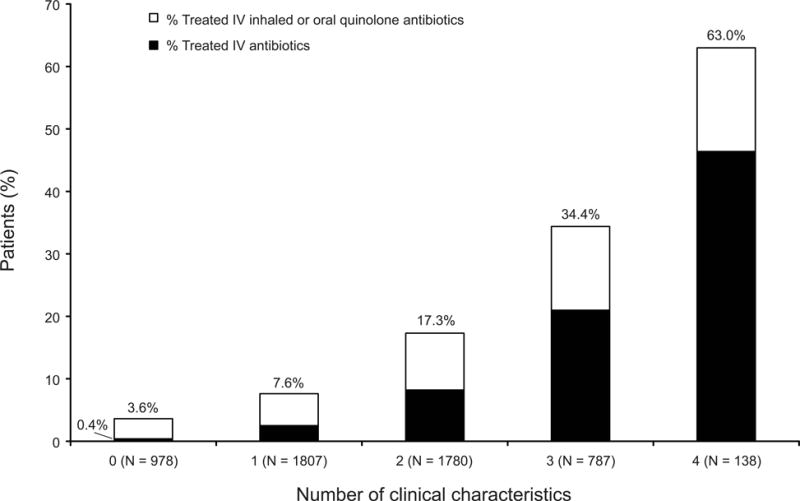

In the analysis cohort of 5490 patients with a mean age of 3 years (SD=1.4) at the study visit, we observed a significant association (P <.001) between the number of the four clinical characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation (new crackles, increased cough, increased sputum, and decline in weight-for-age percentile) present and the initiation of antibiotics around the time of the visit at which the patients showed these characteristics (Fig. 2). This relationship was similar whether or not the patients had a positive culture for P. aeruginosa. This relationship persisted even when limiting the data to the 1072 patients who were not part of the earlier analysis by Rabin et al.6 Of note, even when these young patients experienced all four characteristics, only 63% were treated.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients treated with antibiotics by number of the four characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation present at the study visit.

Among patients with one or more of these clinical characteristics of an exacerbation, many were not treated with IV, inhaled, or oral quinolone antibiotics within 7 days before or up to 28 days after the study visit as shown in Figure 2. Females were more likely than males to receive antibiotic treatment (odds ratio [OR], 1.27; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–1.48). Patients presenting with crackles, cough, or P. aeruginosa were more likely to be treated (P <.001; data not shown). Patients hospitalized during the baseline period were more likely to receive antibiotic treatment (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 2.00–2.69). Age, sputum category, and baseline weight-for-age z-score were not associated with the likelihood of treatment after stratifying by number of these four characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation.

Overall, 92% of patients had one or more respiratory tract cultures obtained and recorded during the baseline and study visit periods. Patients with a greater number of these characteristics of exacerbation were more likely to have respiratory tract cultures at the study visit (88%, 91%, 93%, and 95% for those with zero, one, two, and three or four characteristics, respectively; P <.001). Patients with respiratory tract cultures positive for P. aeruginosa were much more likely to be treated with anti-pseudomonal antibiotics by any route (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 2.59–4.16), including IV antibiotics (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.37–2.46), than those without P. aeruginosa.

The first follow-up visit was about 5 months (median=169 days, mean=148 ± 43 days) after the study visit. As shown in Table 1 the most common of the 4 clinical characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation was increased cough, while new crackles was the least common. The number of clinical characteristics was not significantly associated with gender, age, or diagnosis by newborn screening (Table 1). However, increased morbidity at the follow-up visit was associated with a greater number of clinical characteristics. This was true for all the morbidity outcomes in Table 1 (e.g., crackles, cough, sputum, wheeze, P. aeruginosa infection, hospitalization, and weight-for-age).

Table 1.

Demographics and Frequencies of Signs and Symptoms by the Number of Four Characteristics of Pulmonary Exacerbation Present at the Study Visit

| Number of characteristics*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 or 4 | ||

|

|

||||||

| 5490 | 978 | 1807 | 1780 | 925 | ||

| Characteristics at Study Visit | New crackles | 5490 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 50.6 |

| Increased cough | 5490 | 0.0 | 70.4 | 93.4 | 98.1 | |

| Increased sputum | 5490 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 61.5 | 91.0 | |

| >45% decrease in weight percentile | 5490 | 0.0 | 18.4 | 36.1 | 75.2 | |

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | Percent treated | 5490 | 3.6 | 7.6 | 17.3 | 38.7 |

| Percent female | 5490 | 49.2 | 47.8 | 49.2 | 50.5 | |

| Age in years, mean (range) |

5490 | 3.0 (1.0–5.8) |

2.9 (1.0–5.9) |

2.9 (1.0–5.8) |

2.9 (1.0–5.9) |

|

| Percent diagnosed by screening | 5490 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 14.9 | |

|

| ||||||

| Study Outcomes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Any Crackles (%) | Study visit | 5490 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 50.8 |

| Follow-up visit | 5490 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 7.8 | 14.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| Any Cough (%) | Study visit | 5470 | 27.9 | 84.6 | 99.2 | 100 |

| Follow-up visit | 5434 | 58.4 | 68.1 | 77.5 | 81.9 | |

|

| ||||||

| Any Sputum (%) | Study visit | 5437 | 3.9 | 11.4 | 62.6 | 91.7 |

| Follow-up visit | 5404 | 17.9 | 22.0 | 35.0 | 46.3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Any Wheeze (%) | Study visit | 5490 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 15.0 |

| Follow-up visit | 5490 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 7.1 | |

|

| ||||||

| PA (%) | Study visit | 2298 | 16.2 | 21.6 | 24.2 | 33.6 |

| Follow-up visit | 2258 | 20.4 | 21.5 | 26.5 | 32.1 | |

|

| ||||||

| Hospitalized (%) | Baseline year | 5490 | 22.2 | 28.0 | 37.8 | 51.2 |

| Follow-up year | 5490 | 10.3 | 15.5 | 23.9 | 36.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| Weight-for-age z-score (mean) | Study visit | 5371 | −0.05 | −0.31 | −0.60 | −1.33 |

| Follow-up visit | 5389 | −0.06 | −0.22 | −0.49 | −0.99 | |

PA = Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Characteristics were new crackles, increased frequency of cough, increased frequency of sputum, and decline in weight for age percentile by >45% from best during the baseline period to the study visit (see Methods).

All P <.001 for differences across the number of characteristics, except for percent female, mean age, and percent diagnosed by newborn screening.

Treated patients had significantly greater declines in percentage of patients with any crackles, cough or wheeze, and with P. aeruginosa between the study visit and the follow-up visit than untreated patients (Table 2, see column for adjusted P values). For example, the percentage of patients with crackles dropped from 36.8% to 12.8% in treated patients and from 7.9% to 6.2% in untreated patients. Treatment had no effect on the percentage of patients with sputum, those hospitalized, or change in weight-for-age between the study visit and first follow-up visit. For the P. aeruginosa–positive patients, these relationships were similar, except that the weight-for-age z-score improved significantly in treated patients compared with those not treated (P = .014, data not shown).

Table 2.

Response of Signs and Symptoms Present at Study Visit to Treatment

| N | N | Treated | Not treated |

P value* | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5490 | 837 | 4653 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Any Crackles (%) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

5490 5490 |

36.8 12.8 |

7.9 6.2 |

<.001 <.001 |

<.001 |

| Any Cough (%) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

5470 5434 |

96.3 75.8 |

79.4 71.0 |

<.001 .005 |

.007 |

| Any Sputum (%) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

5437 5404 |

65.1 36.6 |

35.9 28.3 |

<.001 <.001 |

.30 |

| Any Wheeze (%) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

5490 5490 |

18.4 5.7 |

5.6 5.0 |

<.001 .36 |

<.001 |

| PA (%) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

2298 2258 |

44.6 30.3 |

18.6 23.5 |

<.001 .006 |

<.001 |

| Hospitalized (%) | Baseline year Follow-up year |

5490 5490 |

51.0 36.0 |

31.0 18.2 |

<.001 <.001 |

.73 |

| Weight-for-age z-score (mean) | Study visit Follow-up visit |

5371 5389 |

−0.80 −0.56 |

−0.48 −0.38 |

<.001 <.001 |

.19 |

PA = Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Unadjusted P value for treated vs not treated (χ2 for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables).

Adjusted P value for treated vs not treated change from study visit to follow-up visit (or baseline period to first follow-up year for hospitalization), controlling for number of characteristics (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables).

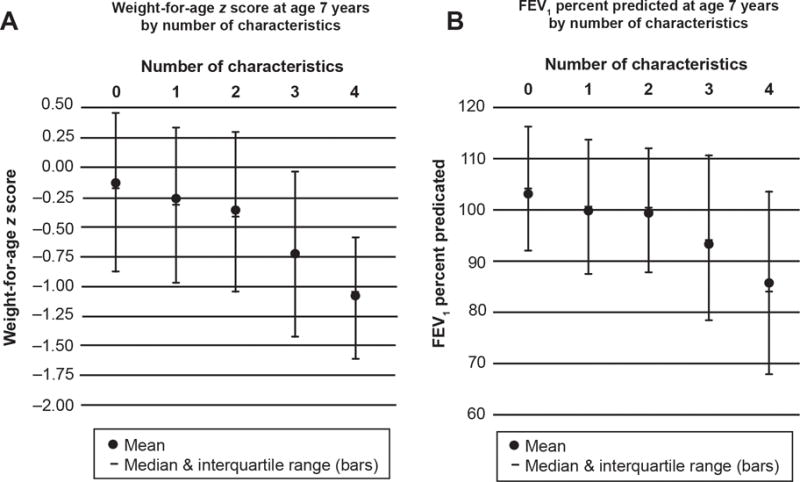

Although number of characteristics at the study visit was associated with weight-for-age z-score and FEV1 percent predicted at age 7 (Figure 3, P <.001 for both), treatment at the study visit was not associated with better weight-for-age z-score or FEV1 percent predicted at age 7.

Figure 3.

The weight-for-age z-score (A) and the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) percent predicted (B) for patients at age 7 by number of the characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation that were present at the study visit. P <.001 for both panels A and B by analysis of variance.

Discussion

One goal of this study was to test a definition of a pulmonary exacerbation of CF, based on signs and symptoms and not on therapy or hospitalization, for reproducibility in children age 6 and younger. The ESCF data set is uniquely suited to this study because information on the clinician’s diagnosis of a pulmonary exacerbation, including signs and symptoms, was recorded. One sentinel event often used to define a pulmonary exacerbation in CF is treatment with IV antibiotics. The current definition using four characteristic signs and symptoms was highly associated in a dose-response manner with the clinicians’ decision to treat with IV antibiotics, both in a group of children enrolled after the study by Rabin6 and in the pooled patient group. The presence of an increasing number of these four characteristic signs and symptoms of a pulmonary exacerbation was also associated with 1) increased percentage of patients with P. aeruginosa detected in airway secretions, and 2) increasing morbidity in the longer term. This fits well with criteria suggested to define a pulmonary exacerbation in CF using signs and symptoms.2 The data do not indicate a clear threshold number of characteristics that resulted in treatment for a diagnosis of a pulmonary exacerbation. Rather the pattern in Fig. 1 suggests that clinicians are more likely to diagnose and treat a pulmonary exacerbation as more of these four characteristics are found during a single visit. A wide variability among clinicians in their threshold for making this diagnosis and prescribing treatment is also apparent.

We used the ESCF data set because it recorded whether a clinician was prescribing antibiotics for “prophylaxis” or for a “pulmonary exacerbation.” This enabled us to define the presenting symptoms and signs most closely associated with this diagnosis and treatment.6 Using the clinical characteristics from the Rabin study,6 our current study confirmed that the proportion of young CF patients who received antibiotic treatment rose with the number of four specific clinical characteristics of a pulmonary exacerbation (new crackles, increased cough, increased sputum, and a relative decline of more than 45% in the weight-for-age percentile) in independent and pooled patient samples.

The increase in proportion treated almost doubled with each additional characteristic present without a clear breakpoint (Fig. 1). Longer-term morbidity also tended to increase with the increasing number of these clinical characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation present at a visit without a clear breakpoint. This suggests that if any of these characteristics of a pulmonary exacerbation are present at a visit, the patient is at increasing risk of subsequent morbidity of a degree proportionate to the number of these characteristics found.

The presence of an increasing number of these characteristics also correlated with other markers of disease progression in CF: the prevalence of P. aeruginosa detected in respiratory secretions increased as the number of these characteristics increased, from about 16% of patients with no characteristic present to about 34% of patients with three or four characteristics; and the weight-for-age z-scores and FEV1 percent predicted at age 7 declined as the number of these characteristics present at a single prior clinic visit about the age of 3 years increased.

Another prospective, population-based study by Rosenfeld et al7 found that in CF patients 6 years and older, the history of increased cough, increased sputum production, and new adventitial sounds on auscultation were predictive of the presence of a pulmonary exacerbation by physician assessment. This was a select group of older CF patients who participated in a therapeutic trial requiring that P. aeruginosa be detected in their respiratory secretions. The ESCF data set included a broader CF population,6 and the current study focused on those under the age of 6 years who generally lack information from spirometry and who often do not harbor P. aeruginosa. The ESCF captured three similar characteristics: increased cough, increased sputum production, and new crackles. Among a total of 10 characteristics evaluated, Rabin et al found that these three, along with decreased weight-for-age percentile, were significantly related to a clinician-diagnosed pulmonary exacerbation.6 We found this association again in this current group of young CF patients not previously studied.

We found that patients showing the same number of characteristics at a study visit were more likely to be treated if P. aeruginosa was detected in their respiratory secretions. Of clinical importance, antibiotic treatment reduced the proportion of these children with P. aeruginosa detected in their respiratory secretions at first follow-up visit.

We found that those treated with antibiotics were more likely to be free of crackles, cough, and wheeze following treatment. Even so, our data showed that a higher proportion of treated patients were hospitalized during follow-up than those not treated. This suggests confounding by indication. The effect of antibiotic treatment upon hospitalization may be confounded by the increased likelihood of treatment of patients with more severe disease not completely accounted for by the presence of new crackles, cough, sputum, decreased weight, or P. aeruginosa. For example, clinicians may treat because of perceived increased risk due to social or environmental factors such as socioeconomic status or their perception of the family’s ability to care for an ill child. Consistent with this possibility, patients selected for treatment had been hospitalized more frequently during the 12-month baseline period. The association of treatment with disease severity makes the detection of the effect of treatment difficult, as has been shown in an examination of inhaled tobramycin use in CF patients.8 As might be expected, longer-term outcomes at age 7 were not improved by this single course of therapy at the study visit. This may reflect the practice pattern at centers that are more likely to treat exacerbations aggressively with antibiotics9 or the bias favoring treatment of patients perceived as having more severe disease. Most likely, the lack of observed improvement in the percent with sputum and in weight-for-age z-score at the follow-up visit and in the outcomes at age 7 reflects the limited impact of a single course of antibiotic therapy on persistent airway infection and inflammation.

Taken together, the results of this observational study support a short-term benefit of a single treatment with IV, inhaled, or oral quinolone antibiotics in young CF patients with characteristics of pulmonary exacerbation (new crackles, increased cough, increased sputum, and decreased weight for age). Similar benefits have been seen in randomized, placebo-controlled trials of these therapies in older patients with pulmonary exacerbations and P. aeruginosa.10,11 Our results demonstrate varying practice patterns among physicians in prescribing antibiotics to young children with CF, even when three or four characteristics associated with a pulmonary exacerbation were evident and P. aeruginosa was detected. When three or more characteristics were evident, 61% were not treated with these antibiotic regimens, and when two characteristics were evident, 83% were not treated. This was similar to the results of Rosenfeld et al7 who found that 47% of their older patients, all of whom had P. aeruginosa, were not treated with oral or IV antibiotics within 14 days of the diagnosis of pulmonary exacerbation.7

Many of these young CF patients with clinical characteristics of a pulmonary exacerbation and positive cultures for P. aeruginosa were not treated with IV, inhaled, or oral quinolone antibiotics despite their demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the density of P. aeruginosa in the airway secretions of CF patients.10,11 Recognition of these four clinical characteristics of an acute deterioration in pulmonary status and appropriate antibiotic treatment present an opportunity to reduce acute respiratory morbidity in these young patients.

We conclude that the presence of one or more of these four clinical characteristics at a single clinic visit identifies young patients having a pulmonary exacerbation whose signs and symptoms are likely to improve with antibiotic treatment. These children are at increased risk for subsequent morbidity directly related to the number of these characteristics present. A single course of antibiotic therapy resulted in greater reduction in some of these characteristics and a reduction in the proportion with P. aeruginosa detected in their subsequent respiratory secretions; however, it did not affect the likelihood of hospitalization in the follow-up year or the outcomes at age 7 years.

Acknowledgments

Mary Ellen B. Wohl, MD, Steven M. Butler, PhD, and Lori S. Parsons, BS, were co-authors of an earlier version of this manuscript. All sources of support for the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis in the form of grants, case report forms, and data analysis were provided by Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA.

All authors contributed to the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. We appreciate the review of the manuscript and constructive comments by Terri Laguna, MD, MSCS and Marilyn Joseph, MD.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

WR, MS, JW, WM, and MK have received honoraria from Genentech, Inc., for serving as members of the Scientific Advisory Group for the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis (ESCF). No compensation was provided to these authors in exchange for production of this manuscript. DP and EE are employees of ICON Late Phase & Outcomes Research, which was paid by Genentech for providing analytical services for this study. JW was previously an employee of Genentech. This study is sponsored by Genentech, Inc.

The decision to submit the manuscript was made by the authors and other members of Scientific Advisory Group and was approved by Genentech, Inc.

References

- 1.Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, Nash ML, Ramsey BW, Rosenstein BJ, Smith AL, Wohl ME. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. The Pulmozyme Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:637–642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goss CH, Burns JL. Exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. 1: Epidemiology and pathogenesis. Thorax. 2007;62:360–367. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall BC. Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis: it’s time to be explicit! Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:781–782. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2401009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld M. An overview of endpoints for cystic fibrosis clinical trials: one size does not fit all. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:299–301. doi: 10.1513/pats.200611-178HT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan WJ, Butler SM, Johnson CA, Colin AA, FitzSimmons SC, Geller DE, Konstan MW, Light MJ, Rabin HR, Regelmann WE, Schidlow DV, Stokes DC, Wohl ME, Kaplowitz H, Wyatt MM, Stryker S. Epidemiologic study of cystic fibrosis: design and implementation of a prospective, multicenter, observational study of patients with cystic fibrosis in the U.S. and Canada. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28:231–241. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199910)28:4<231::aid-ppul1>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabin HR, Butler SM, Wohl MEB, Geller DE, Colin AA, Schidlow DV, Johnson CA, Konstan MW, Regelmann WE. Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis. Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis: Clinical signs and symptoms associated with antibiotic interventions. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:400–406. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Williams-Warren J, Pepe M, Smith A, Montgomery AB, Ramsey B. Defining a pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2001;139:359–365. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothman KJ, Wentworth CE., 3rd Mortality of cystic fibrosis patients treated with tobramycin solution for inhalation. Epidemiology. 2003;14:55–59. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson C, Butler SM, Konstan MW, Morgan W, Wohl ME. Factors influencing outcomes in cystic fibrosis: a center-based analysis. Chest. 2003;123:20–27. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey BW, Pepe MS, Quan JM, Otto KL, Montgomery AB, Williams-Warren J, Vasiljev-K M, Borowitz D, Bowman CM, Marshall BC, Marshall S, Smith AL. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Inhaled Tobramycin Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:23–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regelmann WE, Elliott GR, Warwick WJ, Clawson CC. Reduction of sputum Pseudomonas aeruginosa density by antibiotics improves lung function in cystic fibrosis more than do bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy alone. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(4 Pt 1):914–921. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.4_Pt_1.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]