Abstract

Objective

Given recent government investigations and media coverage of the controversy regarding mesh surgery, we sought to define patient knowledge and perceptions of vaginal mesh surgery.

Study Design

An anonymous survey was distributed to a convenience sample of new patients at Urogynecology and Female Urology clinics at a single medical center during April–June 2012. The survey assessed patient demographics, information sources, beliefs and concerns regarding mesh surgery. Fisher’s exact test was used to identify predictors of patients’ beliefs regarding mesh. Logistic and linear regressions were used to identify predictors of aversion to surgery and higher concern regarding future surgery.

Results

164 women completed the survey; 62.2% (102/164) indicated knowledge of mesh surgery for prolapse and/or incontinence and were included in subsequent analyses. Mean age was 58.0±12.5 years and 24.5% reported prior mesh surgery. The most common information source was TV commercials (57.8%); only 23.5% of women reported receiving information from a medical professional. Participants indicated the following regarding vaginal mesh: class-action lawsuit in progress (55/102, 54.0%), causes pain (47/102, 47.1%), possibility of rejection (35/102, 34.3%), can cause bleeding and become exposed vaginally (30/102, 29.4%), and should be removed due to recall (28/102, 27.5%). Of these women, 22.1% (19/86) indicated they would not consider mesh surgery. On multivariable logistic regression, level of concern, information from friends/family, and knowledge of class-action lawsuit predicted aversion to mesh surgery.

Conclusion

Nearly two-thirds of new patients had knowledge of vaginal mesh surgery. We identified considerable misinformation and aversion to future mesh surgery among these women.

Keywords: Media, patient counseling, television commercials, vaginal mesh surgery

INTRODUCTION

Midurethral mesh slings and, later, prepackaged transvaginal mesh kits have become increasingly popular surgical treatments for repair of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1,2 Recent work has found that use of mesh-augmented prolapse repairs has increased substantially over the last decade, and this increase was most pronounced from 2004–2007.3

In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a Public Health Notification regarding serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for the repair of POP and SUI including erosion, infection, pain; bowel, bladder, or blood vessel perforation; and failure of the procedure.4 After further review, in July 2011 the FDA released a Safety Notification stating that serious adverse events associated with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of POP are not rare and that transvaginally placed mesh for POP repair does not conclusively improve patient outcomes as compared to traditional non-mesh repair.1

Following the FDA publications, the controversy surrounding the use of transvaginal mesh reached the public through television commercials regarding litigation, news reports, the internet and magazines, including The New York Times and Consumer Reports.5,6,7 The impact of this public controversy on patient knowledge and decision-making remains undefined. With the amount of medical information directly and readily available to patients today, this concept merits study as it may influence decision-making prior to seeking care. We sought to further define patient knowledge and perceptions of vaginal mesh surgery amongst new patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Women presenting as new patients to the Urogynecology and Female Urology clinics at the University of Michigan between April and June 2012 completed an anonymous survey as part of a convenience sample. Survey questions were developed based on the expert consensus of 8 fellowship-trained attending physicians. A pilot questionnaire was developed and tested to determine if questions could be understood and completed accurately. The final questionnaire is included as Appendix 1. This study was reviewed and considered exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

The initial question asked if women had heard anything about vaginal mesh surgery; women who indicated they had not did not complete the rest of the survey. The remaining questions assessed patient demographics, personal history of mesh surgery, and sources of information and existing beliefs about vaginal mesh surgery. As the surveys were anonymous, women could not be contacted if items were incomplete and medical records were not consulted.

For analysis, demographic characteristics and patient beliefs about mesh surgery were described. Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine whether a personal history of mesh surgery, being seen in clinic for a relevant condition (POP or urine leakage), or having received prior information from a medical professional were associated with women’s beliefs regarding mesh surgery.

The primary outcomes of interest were aversion to future surgery and level of concern regarding possible future surgery. Aversion to surgery was defined as a patient indicating “yes” or “maybe” that she would avoid future surgery based on the information she had learned prior to presentation for care. Level of concern was scored on a 0–10-point Likert scale (Appendix 1). First, univariable logistic regression models were used to examine associations of patient age, level of education, personal history of mesh surgery, reason for new patient visit, beliefs regarding mesh surgery, sources of information, and level of concern regarding the possibility of future surgery with aversion to any future surgery and aversion to future mesh surgery, respectively. Variables found to be significantly associated with the outcomes on univariable analyses were then included in multivariable logistic regression. Next, univariable linear regression models were used to examine associations of patient age, level of education, personal history of mesh surgery, reason for new patient visit, beliefs regarding mesh surgery and sources of information with level of concern regarding the possibility of future surgery with mesh. Variables found to be significant on univariable analyses were then included in a multivariable linear regression model. For all analyses, p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0 (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

In this convenience sample, 164 women completed the survey. About two-thirds (102/164, 62.2%) indicated having heard about mesh surgeries for POP and/or SUI and were included in subsequent analyses. The mean age of respondents was 58.0±12.5 years (range 29–94). A quarter of women reported having personally undergone mesh surgery for repair of SUI and/or POP (24.5%, 25/102). The most common source of information about mesh was TV commercials (57.8%); only 23.5% of patients reported receiving information from another medical professional (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population (n=102)

| Mean Age (standard deviation, range) | n=88 | |

| 57.96 (12.5, 29–94) | ||

| Highest level of education completed (n (%)) | n=98 | |

| 8th grade | 4 (4.1) | |

| High school | 37 (37.8) | |

| College | 35 (35.7) | |

| Graduate Degree | 22 (22.5) | |

| Reason for visit (n (%)) | n=99 | |

| Urine leakage | 28 (28.3) | |

| Pelvic organ prolapse | 25 (25.3) | |

| Both urine leakage and pelvic organ prolapse | 30 (30.3) | |

| Neither of these problems | 14 (14.1) | |

| Personal history of mesh surgery for incontinence or prolapse (n (%)) | 25/102 (24.5) | |

| Sources of information about vaginal mesh* (n (%)) | n=102 | |

| Internet | 25 (24.5) | |

| Friends/family | 28 (27.5) | |

| Other medical professional | 24 (23.5) | |

| TV news report | 25 (24.5) | |

| TV commercial | 59 (57.8) | |

Respondents could select more than one option.

Table 2 compares patient beliefs regarding vaginal mesh surgery based on a personal history of prior mesh surgery. Women with a personal history of mesh surgery were more likely to report knowledge of a class action lawsuit (p= 0.009) and that mesh carries a possibly higher surgical success rate (p = 0.024). Most women (83.3%) expressed some level of understanding that different mesh surgeries carry different risks.

Table 2.

Patient beliefs about mesh surgery

| Patient belief | All

study participants (n=102) n (%) |

Participants with no personal history of mesh surgery (n=77) n (%) |

Participants with a personal history of mesh surgery (n=25) n (%) |

P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh has been taken off the market | 24 (23.5) | 18 (23.4) | 6 (24.0) | 0.572 |

| Mesh has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately | 28 (27.5) | 21 (27.3) | 7 (28.0) | 0.566 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 48 (47.1) | 36 (46.8) | 12 (48.0) | 0.548 |

| Mesh can cause cancer | 9 (8.8) | 7 (9.1) | 2 (8.0) | 0.615 |

| All surgeries with mesh have the same risk of problems | 21 (20.6) | 16 (20.8) | 5 (20.0) | 0.590 |

| Mesh can cause bleeding and exposure of mesh in the vagina | 30 (29.4) | 22 (28.6) | 8 (32.0) | 0.463 |

| Mesh can result in a higher success rate after surgery | 11 (10.8) | 5 (6.5) | 6 (24.0) | 0.024 |

| Mesh can result in a lower success rate after surgery | 10 (9.8) | 8 (10.4) | 2 (8.0) | 0.537 |

| My body might reject the mesh material | 35 (34.3) | 27 (35.1) | 8 (32.0) | 0.490 |

| My body might have an allergic reaction to the mesh material | 30 (29.4) | 24 (31.2) | 6 (24.0) | 0.339 |

| There is a class action lawsuit in progress | 55 (53.9) | 36 (46.8) | 19 (76.0) | 0.009 |

Fisher’s exact test comparing beliefs between participants with and without a personal history of mesh surgery

Women who had received prior information from a medical professional were more likely than those who reported other non-medical sources of information to indicate: “my body might reject the mesh material” (p=0.005), there is a risk of bleeding/exposure of mesh in the vagina (p=0.003), and the possibility of a higher success rate of surgery utilizing mesh (p=0.019).

Examining patients’ baseline knowledge regarding indications for mesh surgery, women indicated that a “sling” repairs a dropped bladder (60.8%, 62/102), urine leakage (48.0%, 49/102) and “going to the bathroom too often” (18.6%, 19/102). Individuals who presented for care related to urine leakage/POP were less likely than those presenting for neither of these problems to believe a “sling” repairs a “dropped bladder” (p=0.009).

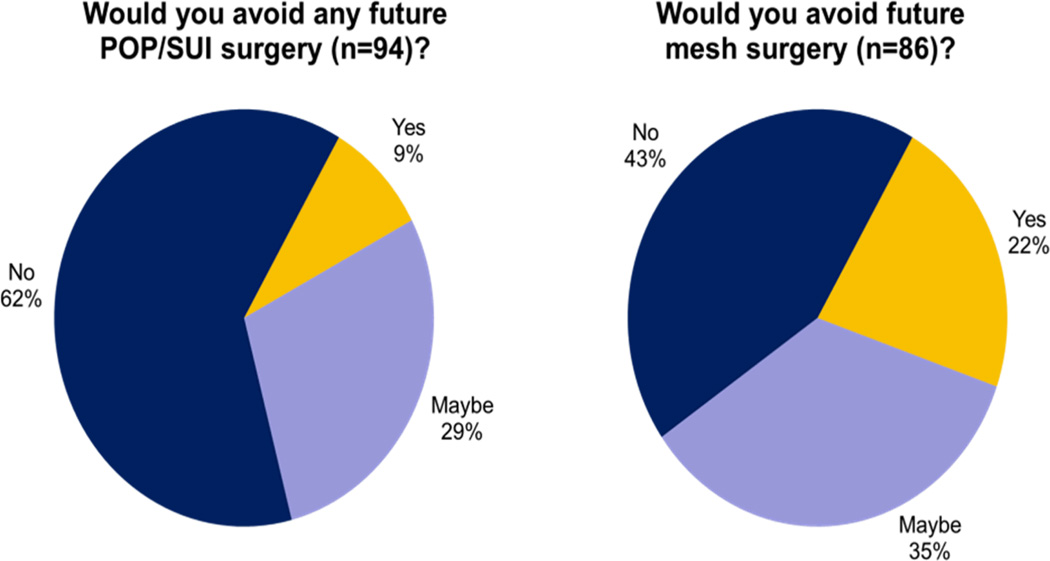

Regarding future care, the mean level of concern regarding possible surgery with mesh was 5.74 ± 3.27 on a 0–10 point Likert scale. Nonetheless, most women (62.8%, 59/94) indicated they would be willing to undergo POP/SUI surgery of any type (Figure 1). Only 8.5% (8/94) said they would refuse all surgery because of their existing knowledge. If future surgery were to involve mesh placement, 22.1% (19/86) indicated a willingness to consider this option, while 43.1% (37/86) of women would refuse.

Figure 1.

Patient aversion to surgery related to mesh beliefs presenting for new appointment

Results of all univariable logistic regression analyses are available in Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression models were then performed including all significant variables. Only a higher level of concern regarding mesh surgery remained significantly associated with aversion to any future surgery (OR 1.26, p=0.012) (Table 4). A higher level of concern regarding mesh surgery (OR 1.47, p=0.002), having heard about mesh surgery from friends/family (OR 10.45, p=0.007) and knowledge of a class-action lawsuit (OR 5.52, p=0.008) remained significantly associated with aversion to future mesh surgery (Table 4).

Table 3.

Results of univariable regression models

| Predictors of wanting to avoid any future surgery | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Odds Ratio*

(95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Mesh has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately | 2.94 (1.17, 7.39) | 0.022 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 2.47 (1.04, 5.83) | 0.040 |

| Mesh can cause cancer | 7.13 (1.39, 36.56) | 0.019 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from a TV news report | 4.78 (1.76, 13.02) | 0.002 |

| Overall level of concern | 1.33 (1.12, 1.58) | 0.001 |

| Predictors of wanting to avoid future mesh surgery | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Odds Ratio*

(95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Mesh has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately | 3.00 (1.05, 8.57) | 0.040 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 3.18 (1.31, 7.75) | 0.011 |

| Mesh can cause bleeding and exposure of mesh in vagina | 2.96 (1.09, 8.04) | 0.034 |

| There is a class-action lawsuit in progress | 4.55 (1.82, 11.40) | 0.001 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from friends/family member | 4.05 (1.34, 12.22) | 0.013 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from TV news report | 5.49 (1.46, 20.63) | 0.012 |

| Overall level of concern | 1.48 (1.22, 1.80) | <0.001 |

| Predictors of level of concern regarding the possibility of surgery with mesh | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Average change from the mean Likert score** (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Heard about mesh surgery from TV news report | +1.73 (0.18, 3.27) | 0.029 |

| Reason for visit is neither leakage or POP | −2.37 (−4.42, −0.33) | 0.023 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | +2.47 (1.17, 3.76) | <0.001 |

| Mesh can cause cancer | +2.57 (0.34, 4.81) | 0.025 |

| Mesh can cause bleeding and exposure of mesh in the vagina | +2.34 (0.93, 3.75) | 0.001 |

| My body might reject the mesh material | +2.33 (0.99, 3.68) | 0.001 |

| My body might have an allergic reaction to the mesh material | +2.54 (1.17, 3.91) | <0.001 |

| There is a class-action lawsuit in progress | +1.94 (0.58, 3.30) | 0.006 |

Model included patient age, level of education, personal history of mesh surgery, reason for new patient visit, beliefs regarding mesh surgery, sources of information, and level of concern regarding the possibility of future surgery with aversion to any future surgery and aversion to future mesh surgery respectively

Model included patient age, level of education, personal history of mesh surgery, reason for new patient visit, beliefs regarding mesh surgery and sources of information with level of concern regarding the possibility of future surgery with mesh

Table 4.

Results of multivariable regression models

| Predictors of wanting to avoid any future surgery | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Mesh has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately | 1.02 (0.26, 3.98) | 0.978 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 1.04 (0.30, 3.68) | 0.947 |

| Mesh can cause cancer | 2.88 (0.46, 17.81) | 0.256 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from a TV news report | 2.42 (0.67, 8.79) | 0.178 |

| Overall level of concern | 1.26 (1.05, 1.51) | 0.012 |

| Predictors of wanting to avoid future mesh surgery | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Mesh has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately | 0.73 (0.13, 4.05) | 0.720 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 0.82 (0.17, 4.00) | 0.805 |

| Mesh can cause bleeding and exposure of mesh in vagina | 2.09 (0.40, 10.80) | 0.380 |

| There is a class-action lawsuit in progress | 5.52 (1.56, 19.50) | 0.008 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from friends/family member | 10.45 (1.89, 57.85) | 0.007 |

| Heard about mesh surgery from TV news report | 1.71 (0.25, 11.49) | 0.582 |

| Overall level of concern | 1.47 (1.15, 1.89) | 0.002 |

| Predictors of overall level of concern about the possibility of surgery with mesh | ||

| Positive belief that: |

Average change from the mean Likert score (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

| Heard about mesh surgery from TV news report | 0.068 (−1.54, 1.68) | 0.933 |

| Reason for visit is neither leakage or POP | −2.54 (−4.49, −0.59) | 0.011 |

| Mesh can cause pain, including with sex | 1.53 (0.03, 3.03) | 0.046 |

| Mesh can cause cancer | 0.92 (−1.29, 3.12) | 0.411 |

| Mesh can cause bleeding and exposure of mesh in the vagina | 0.12 (−1.58, 1.84) | 0.881 |

| My body might reject the mesh material | 1.48 (−0.50, 3.46) | 0.141 |

| My body might have an allergic reaction to the mesh material | 0.06 (0.76, 3.35) | 0.954 |

| There is a class-action lawsuit in progress | 2.05 (2.15, 4.56) | 0.002 |

A multivariable linear regression model including all significant variables as covariates confirmed that believing that transvaginal mesh surgery can cause pain including with sex (p=0.046) and knowledge of a class-action lawsuit (p=0.002) were independent predictors of a higher overall level of concern (Table 4). In contrast, being seen in clinic for problems other than leakage or POP (p=0.011) was significantly associated with a lower level of concern (Table 4).

CONCLUSIONS

About two thirds of new patients presenting for urogynecologic care at our institution reported having previously heard about mesh surgery for POP or SUI, suggesting significant but not universal public awareness. Despite this level of awareness, we noted significant misinformation amongst women, including indications for and the complications that can result from vaginal mesh surgery. We also found that women often got information from sources other than a medical provider.

Importantly, we identified a high level of aversion to both mesh surgery and POP/SUI surgery in general, which predated patients’ presentation for care at our institution. This was most common in patients who had gotten information from non-medical sources and had knowledge of legal action regarding this type of surgery. The impact of these factors on patient decision-making is understudied based on our review of the literature. We also identified multiple instances of misinformation among our new patient population, including women reporting that vaginal mesh can cause cancer, might be rejected from the body, needs to be removed immediately due to a recall, or can cause an allergic reaction. We also found that women tended to consider all vaginal mesh surgery the same surgery, regardless of the indication or type of surgery. These factors represent a significant opportunity to direct patient counseling, as provider awareness of this bias in new patients may provide opportunities for patient education prior to treatment planning. The potential for confusion concerning terminology such as “sling” provides an opportunity to clarify language when speaking to patients as well as with marketing.

Fewer patients in our study reported use of the internet for seeking health information than as previously reported in other work (24.5% in our study vs. 58% in other work) .8 Subjects in the Iverson et al. study indicated that their online research influenced the way they think about their health. Whether women consider television commercials, the most prevalent source of information in our study, as a substitute for active information seeking on the internet, merits further study.

Like any patient survey, our work has limitations. Because there is no validated instrument from which we could base our questions, we composed a survey from expert experience and tested questions for comprehension to make the survey as understandable as possible. As our project was anonymous, we could not review patient records for additional information or verify demographic or medical information. Additionally, we recognize that some of the most concerned women may not have presented for care out of a strong aversion to mesh, and it is possible that our study underestimates the true incidence of patient concern and refusal of mesh surgery. As a tertiary referral center with 24.5% of our sample having previously undergone surgery for incontinence or prolapse using mesh, it is possible our “new patient population” included women who possess a more extensive or uniquely defined knowledge base compared to their counterparts presenting for a true new evaluation for the first time, which may also limit the generalizability of this data. To address this issue, we have stratified some analyses for this variable.

This study is the first of its kind describing patient awareness of vaginal mesh surgery prior to presenting for care. In an era when direct-to-patient advertising is more prevalent and easily accessible than ever, our work highlights important new information, which must inform patient counseling. Future research should be directed at patient education and methods of redirecting patient misperceptions, including printed materials and face-to-face counseling.

CONCLUSION

Public information about the controversy surrounding transvaginal mesh has reached many women prior to presentation for care. We identified misinformation and aversion to surgery in our patient population. Our work highlights the need for accurate, accessible patient information and directed patient counseling efforts.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: None

Study conducted in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Appendix 1

Study Instrument

There are many treatments for urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse, and some involve surgery. That surgery could involve placement of a graft, which can be made of permanent mesh material.

1. Have you heard anything before about mesh surgeries for these conditions? YES

NO

If NO, thank you for completing this survey. Please give it to your doctor.

If YES, please continue:

2. Have YOU personally had surgery before for incontinence or prolapse using mesh?

YES NO

3. Are you here today because of:

a. Urine leakage

b. Pelvic organ prolapse/dropped organs

c. Both urine leakage and pelvic organ prolapse/dropped organs

d. Neither of these problems

4. Please circle anything below that you have heard about mesh surgery:

a. It has been taken off the market.

b. It has been recalled and should be removed from the body immediately.

c. It can cause pain, including with sex.

d. It can cause cancer.

e. All surgeries with mesh have the same risk of problems.

f. It can cause bleeding and exposure of the mesh in the vagina.

g. It can result in a higher success rate after surgery.

h. It can result in a lower success rate after surgery.

i. My body might reject the mesh material.

j. My body might have an allergic reaction to the mesh material.

k. There is a class-action lawsuit in progress.

5. Where did you hear about this issue? (circle any that are true)

a. Internet

b. Friends/family member

c. Other medical professional (doctor, nurse, etc)

d. TV news report

e. TV commercial

6. What problem does a "sling" repair? (circle all that are true)

a. Dropped bladder

b. Urine leakage

c. Going to the bathroom too often

d. Kidney stone

e. All of above

7. How concerned are you about possible surgery with mesh? Please circle a number below.

0--------1--------2-------3-------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10

Not worried Somewhat worried Very

worried

8. Would the information you've already learned mean that you would avoid surgery at all?

Yes No Maybe

9. Would the information you've already learned mean that you would avoid surgery using

mesh at all?

Yes No Maybe

10. What information do you want from your doctor before considering having a mesh

surgery?

______________________________________________________________________

11. Age _________

12. Highest education level you have completed:

a. 8th grade b. High school c. College d. Graduate

degree

13. Comments:

Footnotes

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

This work was accepted for oral poster presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons 39th Annual Scientific Meeting, Charleston, SC, April 8–10, 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.FDA Safety Communication: UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. [accessed 12/29/12]; doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1581-2. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm. Published 7/13/2011, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Funk MJ, Edenfield AL, Pate V, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Wu JM. Trends in use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:79.e1–79.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin M, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, Lu YS, Raz S, Hershman DL, wright JD. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000–2012. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;120(5):1105–1115. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826ebcc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FDA Public Health Notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. [Accessed 12/29/2012]; doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.055. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Issued 10/20/2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rabin RC. Trial of Synthetic Mesh in Pelvic Surgery Ends Early. The New York Times. 10/22/10. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/26/health/research/26complications.html?_r=0. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier B. F.D.A. orders Surgical Mesh Makers to Study Risks. The New York Times. 1/4/12. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/05/health/research/fda-orders-more-study-on-surgical-mesh-risks.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dangerous devices: Most medical implants have never been tested for safety. Consumer Reports. 2012 May;:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iverson SA, Howard KB, Penney BK. Impact of internet use on health-related behaviors and the patient-physician relationship: A survey-based study and review. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008 Dec;108(12):699–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]