Preface

Sexual reproduction is a pervasive attribute of eukaryotic species, and is now recognized to occur in many of the most important human fungal pathogens. These fungi utilize sexual or parasexual strategies for a variety of purposes that can impact pathogenesis, such as the formation of drug-resistant isolates, the generation of strains with enhanced virulence, and the modulation of interactions with host cells. Here, we examine the mechanisms regulating fungal sex and the consequences of these programs for human disease.

Despite the prominence of sex in eukaryotic species, the benefits of this reproductive strategy continue to be debated. Current models suggest that the ability of sex to promote genetic variation is important for survival of lineages. Sex can promote adaptation to fluctuating environments, while also limiting the accumulation of deleterious alleles. However, sexual reproduction is associated with increased costs, so that asexual reproduction is predicted to be advantageous under many conditions, particularly as a short-term evolutionary strategy1–3. Moreover, sex carries the risk of genetic conflicts and the breakdown of well-adapted genetic combinations. There is also the two-fold cost of sex, in which only 50% of parental alleles are passed on to any single progeny, as well as two parents are required to make one progeny.

The benefits of sexual versus asexual reproduction are further complicated in pathogenic species. Host-pathogen interactions can lead to cycles of co-adaptation, and may result in species with increased rates of genetic variation. Such an evolutionary arms race between host and pathogen was formulated as the Red Queen hypothesis (BOX 1). In this model, sexual outcrossing in the host promotes adaptation, enabling the host to escape potential destruction by a coevolving pathogen4. Evolution therefore favours faster evolving lineages, allowing such species to stay ahead in the arms race. Conversely, the lack of sex results in the host being unable to outrun the pathogen, leading to extinction. Support for the Red Queen hypothesis has come from two experimental models where sexual populations were found to be more resistant to infection while asexual (self-fertilizing) populations were selected against (BOX 1)5,6.

BOX 1. The Red Queen hypothesis.

This model is an allusion to a scene in Lewis Caroll’s ‘Through the LookingGlass’. The Red Queen’s race illustrates Alice and the Queen constantly running but remaining in the same spot. 'Well, in OUR country,' said Alice, still panting a little, 'you'd generally get to somewhere else--if you ran very fast for a long time, as we've been doing.' 'A slow sort of country!' said the Queen. 'Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!' This model was proposed by Leigh Van Valen in 1973 to indicate that organisms must constantly adapt and evolve to survive a coevolutionary race with other organisms and in an ever-changing environment1. In particular, sex might enable organisms to escape and outrun pathogens. Because adaptation of a species modifies the environment of neighbouring species and imposes selection onto these, cohabiting species play a “null sum game” within their ecosystem. The Red Queen model has received empirical support, underlining that organisms capable of sexual reproduction have better odds of survival under stressful conditions compared to asexual species5,6. One study compared sexual and asexual snail lineages in an environment with natural parasites. Although initially more resistant to infection, the asexual lineage was soon outcompeted and the initial fitness advantage lost. In contrast, sexual lineages persisted throughout the study, supporting the model that sex gives animals an edge in the battle against coevolving parasites5. This was also the case in an interaction between Caenorhabditis elegans and a natural bacterial parasite, as all the obligately selfing populations were driven to extinction while the outcrossing population persisted6.

Studies show that coevolution also drives accelerated evolution rates in the pathogen7,8. While the host persists by keeping one step ahead, the pathogen also adapts by undergoing co-evolutionary fine-tuning9. Moreover, in the case of a fungal plant pathogen, sexual reproduction enabled rapid evolution of the pathogen and infection of a more resistant host10. Thus, co-evolutionary interactions drive adaptive events both in the host and the pathogen, and rapid evolution can be driven by sexual reproduction.

Historically, fungal studies have been used to address key questions concerning the molecular evolution of sex and its role in promoting genetic diversity. Several prominent pathogenic species were long-thought to be clonal and thus restricted to asexual modes of reproduction. This was often due to the inability to observe sexual reproduction under conditions used in the laboratory, or the long time periods required for productive mating. The notion that certain species were asexual was challenged by an increasing body of genomic evidence and, supported by subsequent experimental approaches, has led to the discovery of extant sexual cycles in many clinically relevant species.

In this review, we describe the sexual programs of the most prevalent human fungal pathogens. These species are responsible for a wide variety of diseases, from oral thrush and skin infections to fungal meningitis and bloodstream infections. Although largely clonal, most of these species have retained the molecular machinery and the ability to undergo sex. Sexual or parasexual reproduction is used by these pathogens to shuffle genetic material within the cell, generating recombinant isolates that exhibit altered drug resistance and pathogenicity. Furthermore, we discuss how sexual programs exhibit high plasticity, with novel mechanisms having evolved between species to control this developmental pathway. Overall, studies of sexual reproduction in pathogenic fungi have redefined the paradigms concerning their lifecycles, their evolution, and their ability to adapt to the mammalian host.

Discovery of extant sexual cycles

Among eukaryotes, sexual reproduction is ubiquitous and exclusively asexual lineages are often evolutionary dead ends due to the accumulation of deleterious mutations (termed Muller’s ratchet). It was therefore surprising that prominent fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus were, for many years, considered obligate asexual species. Analysis of genome sequences revealed that these species had retained many genes associated with mating and meiosis. Furthermore, they contained a mating-type locus, a genetic locus encoding the transcription factors that are the master regulators of sexual reproduction11–14. Despite these discoveries, the exclusive use of genome sequences to establish sexual fecundity of a species has proven difficult. While a core set of conserved genes is associated with sexual reproduction in many species (e.g., the ‘meiosis detection toolkit’15), some genes described as being markers of sexual activity (e.g. DMC1, HOP1) are absent in species now known to be sexual13,16. These exceptions have challenged the notion that a set of conserved genes is shared by all sexual species, suggesting significant plasticity in sexual strategies between species.

In the case of the three most important human fungal pathogens - C. albicans, A. fumigatus, and Cryptococcus neoformans – the existence of sexual or parasexual cycles has now been established. Strikingly, each species appears to restrict access to this mode of reproduction, generating largely clonal populations in nature. Why these species have retained the machinery for sex despite the associated fitness costs, and the importance of sexual programs for mediating interactions with the mammalian host, is now beginning to be revealed.

Mating-type loci and mate recognition

Fungi often exhibit bipolar or tetrapolar mating systems that are controlled by transcription factors encoded at the mating-type (MAT) locus (Supplementary information S1a). Bipolar systems have a single biallelic locus and include pathogenic ascomycetes such as C. albicans and A. fumigatus (Supplementary information S2a and c), as well as the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Tetrapolar systems have two unlinked, multiallelic sex loci as exemplified by many basidiomycetes. Bipolar systems allow mating with half of the sibling offspring, thereby enabling both inbreeding (50%) and outbreeding (50%). By contrast, tetrapolar systems favour outbreeding by restricting mating to 25% of the sibling offspring (Supplementary information S1).

Mate recognition occurs through signalling via mating pheromones. For bipolar systems, expression of pheromone and pheromone receptor genes is regulated by MAT-encoded transcription factors17. For tetrapolar systems, one MAT locus encodes regulatory homeodomain transcription factors while the other encodes pheromones and pheromone receptors; the correct combination of pheromone, pheromone-receptor, and transcription factors is necessary for successful mating. Upon stimulation, pheromone receptors turn on a highly conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, resulting in induction of a transcriptional mating response18.

Interestingly, the most prominent human fungal pathogens exhibit bipolar mating-type systems. This is the case for both Cryptococcus gattii and C. neoformans, even though the ancestor to these species had a tetrapolar mating system19. Studies have inferred that the ancestral pheromone locus and transcription factor locus gradually expanded by sequential rounds of gene acquisition, ultimately fusing into a single MAT locus that is >100 kb and encodes >20 genes (Supplementary information S2b)19–21. Recombination at this locus led to the acquisition of several essential genes that restricted further large-scale rearrangements19,22. Recent studies identified recombination hot spots both flanking the C. neoformans MAT locus and within this locus23,24. These observations suggest ongoing gene flow between the two mating types and that gene conversion can occur at genomic regions previously thought to be cold spots for recombination23,24.

The mating-type-like (MTL) locus in C. albicans has also undergone expansion since diverging from the related hemiascomycete, S. cerevisiae. The C. albicans MTL locus includes three genes not present in the S. cerevisiae MAT locus, two of which are essential for growth and have roles unrelated to sex (Supplementary information S2a)13,16,25. C. albicans a1 and α2 transcription factors encoded at the MTL locus control sexual mating by inhibiting a unique phenotypic switch necessary for conjugation (discussed below). Thus, both C. albicans and C. neoformans have evolved mechanisms that may restrict efficient outbreeding.

Studies on the evolution of sex-determining regions in fungi also have implications for the development of sex chromosomes in higher eukaryotes. Analogous to the case in C. neoformans, sex determinants located on one chromosome may have accrued additional sex regulatory genes via genome rearrangements, eventually forming sex chromosomes that are dimorphic between the two sexes3,26.

Homothallism versus heterothallism

Fungal sexual cycles can be heterothallic, in which mating occurs between partners of different sexes and promotes outbreeding, or homothallic, in which organisms are self-fertile promoting inbreeding (Supplementary information S1). Transitions between heterothallic and homothallic lifestyles are common during fungal evolution; the switch from outcrossing to selfing allows expansion of a species to niches where encounters with opposite mating types are rare3.

Limiting outbreeding might be particularly beneficial in human pathogens. Studies in protozoan parasites first indicated that eukaryotic pathogens generate highly clonal populations that undergo limited recombination27. Homothallic reproduction may help preserve genomic configurations that are well adapted for growth in the host, while still allowing strains to undergo occasional recombination and reshuffling of their genomes12.

Studies in the model yeast S. cerevisiae have also shown differences among different populations in their tendency to undergo outbreeding. In particular, human-associated isolates (including clinical and vineyard isolates) showed evidence of sexual outbreeding followed by long periods of clonality28. In this case, the limitation of sexual activity was linked to decreased sporulation and increased pseudohyphal growth. While both responses are stimulated by nutrient limitation, the latter was hypothesized to have a more beneficial response in human-associated environments.

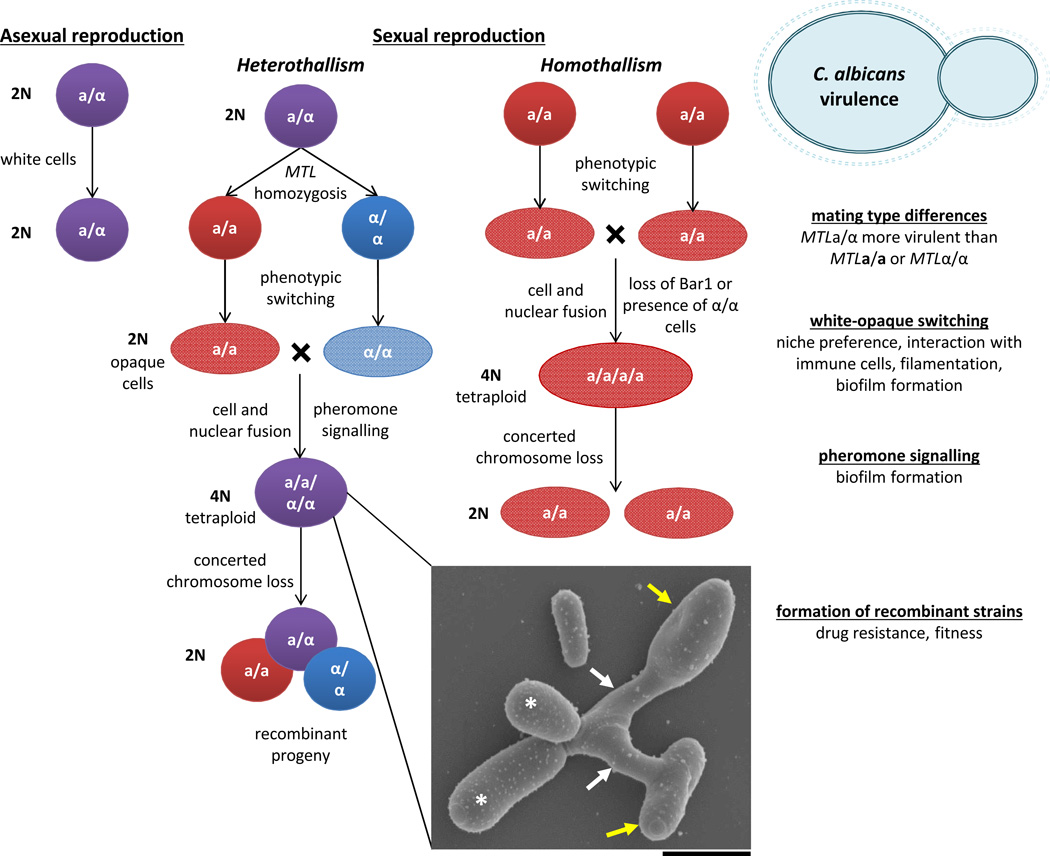

In C. albicans, both heterothallic and homothallic mating has been observed. Heterothallic mating occurs between diploid a and α cells to generate tetraploid a/α products, and is mediated by pheromone signalling between the two mating types (FIG.1). However, in a cells lacking the Bar1 protease same-sex a-a mating can occur29. Bar1 normally acts to degrade α pheromone, but in the absence of this protease a cells do not destroy the α pheromone they produce, and the resulting autocrine feedback loop drives same-sex mating (FIG.1). Homothallic mating is also observed in ‘ménage à trois’ matings in which α pheromone secreted by α cells induces productive mating between two a cells29. C. neoformans has similarly been shown to undergo both heterothallic and homothallic mating. While conventional mating between C. neoformans a and α cells had been well documented30–32, a surprising unisexual mating cycle between C. neoformans α cells has been described33,34 (discussed below and FIG. 2). Unisexual α-α mating is thought to have given rise to highly virulent strains of C. gattii that are the cause of an ongoing outbreak in the Pacific Northwest of the US and Canada35,36.

Figure 1.

Parasexual and asexual reproduction in C. albicans. C. albicans cells are diploid and can divide asexually, or can undergo heterothallic or homothallic mating. MTLa and MTLα cells must switch to opaque to become mating competent (see also BOX 2). Opaque cells secrete pheromones that result in the formation of conjugation tubes, and subsequently cell and nuclear fusion occur to form tetraploid cells. Mating products can be induced to undergo concerted chromosome loss to return to the diploid state. The relationship between virulence and parasexual reproduction is indicated on the right side of the figure. Inset, scanning electron micrograph of a C. albicans mating zygote. Parental opaque cells (yellow arrows) form mating projections (white arrows), and subsequently fuse and generate daughter cells (white asterisk) (taken by M.P. Hirakawa, scale bar = 5 µm).

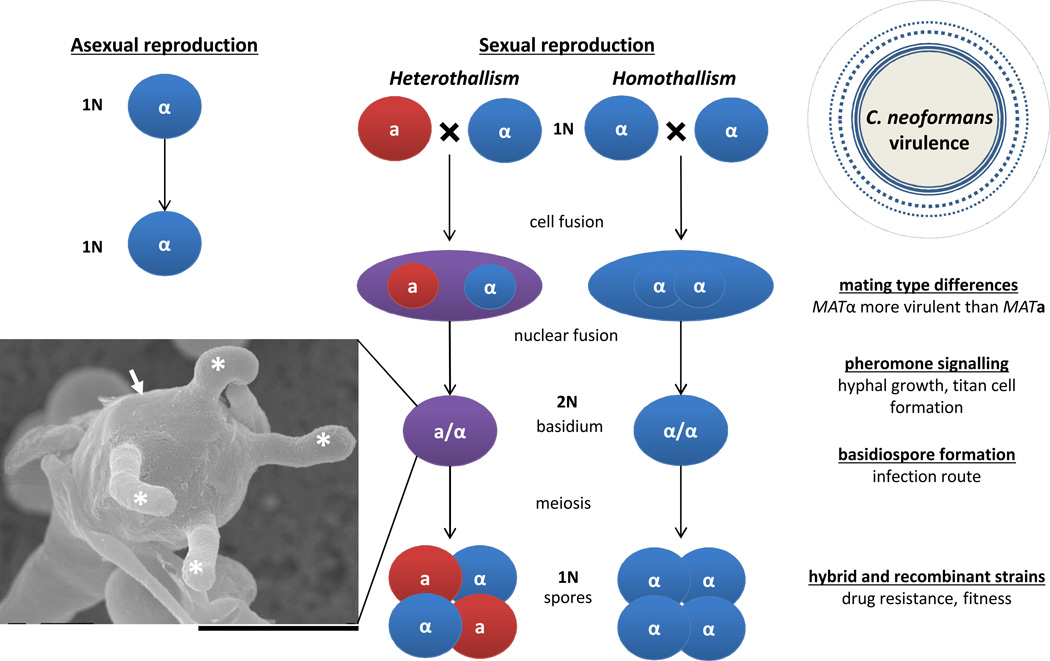

Figure 2.

Sexual and asexual reproduction in C. neoformans. C. neoformans haploid cells can divide asexually or can enter a heterothallic or homothallic mating cycle. In heterothallic mating, pheromone signalling between a and α cells results in cell-cell fusion. Nuclei do not fuse but form a filamentous dikaryon. The tips of the filamentous cells differentiate into basidia within which nuclear fusion and meiosis occur. Additional rounds of mitotic division produce multiple, haploid basidiospores, resulting in four long chains. The consequences of sexual reproduction for virulence in C. neoformans are shown on the right side of the figure. Inset, scanning electron micrograph shows a C. gattii basidium (white arrow) with four emerging basidiospores (white asterisk) (gift of Edmond Byrnes and Joseph Heitman185, scale bar = 5 µm).

What are the benefits of unisexual reproduction? The most obvious is the ability to undergo sex even in the absence of a partner of the opposite mating type. This could be critical for C. neoformans, where the majority of natural isolates are of a single mating type37. Furthermore, ploidy changes can act as capacitors for evolution even in the absence of outbreeding. This was elegantly demonstrated in Aspergillus nidulans, where diploid strains achieved greater fitness than haploid strains during long-term evolution experiments38. The fitter diploid strains had reverted to haploidy via parasexual recombination, and increased fitness was due to the accumulation of recessive deleterious mutations in the diploid state which were beneficial when subsequently unmasked in haploid recombinants38.

Same-sex mating cycles in C. neoformans and C. albicans also promote adaptation due to the formation of chromosome aneuploidies39–41. While aneuploidy often negatively impacts fitness, certain aneuploid chromosomes increase the resistance to antifungal drugs in both species40,42,43. Studies in S. cerevisiae have revealed that aneuploidies can also drive adaptive evolution44,45, and it is therefore likely that karyotypic changes introduced by self-mating provide a diverse pool of isolates upon which selection can act46. Indeed, a recent study by Ni et al. showed that unisexual mating in C. neoformans resulted in phenotypic variants, the majority of which were due to chromosome aneuploidies40. Same-sex mating can provide an additional selective advantage to C. neoformans as hyphal forms induced during mating allow for nutrient foraging over an increased area47.

We also note that similar mechanisms to fungal homothallism are encountered in protozoan parasites. For example, Toxoplasma gondii comprises three highly clonal lineages that have arisen via an ancestral sexual event48, yet this parasite can undergo selfing to generate highly virulent isolates as well as infectious spores49. Similarly, the protozoan Giardia lamblia undergoes a novel type of selfing termed ‘diplomixis’ which involves nuclear fusion analogous to unisexual mating in pathogenic fungi3,50. Both outcrossing and selfing have also been observed in Plasmodium species, whereby a single protozoan can generate both male and female gametes51. It is therefore apparent that unisexual mating is a prevalent mechanism used by eukaryotic microbes to adapt to their environment.

Sex in successful human pathogens

More than 100,000 fungi have been identified to date, but less than 200 are associated with humans and only a minority of these cause disease52. Members of the Candida, Cryptococcus and Aspergillus genera are the most important in clinical settings. Here we compare mating strategies in the three most common human fungal pathogens, C. albicans, C. neoformans, and A. fumigatus. We subsequently consider sexual cycles in other fungal pathogens that impact human health.

Sexual reproduction in Candida albicans

The most clinically relevant Candida species are not found in the environment but are commensals of humans, suggesting co-adaptation with the host. These species are also frequent opportunistic pathogens, with the most commonly isolated species being C. albicans, which is a cause of both mucosal infections (such as thrush and vaginitis) and life-threatening bloodstream infections53. Initially classified as an asexual organism, over the last decade a novel parasexual program has been established for C. albicans54–58. Mating is regulated by a unique phenotypic switch; a and α cells mate efficiently only if they undergo a heritable and reversible transition from the typical ‘white’ state to the mating-competent ‘opaque’ state (BOX 2 and FIG. 1).

BOX 2. A phenotypic switch regulates the parasexual cycle of C. albicans.

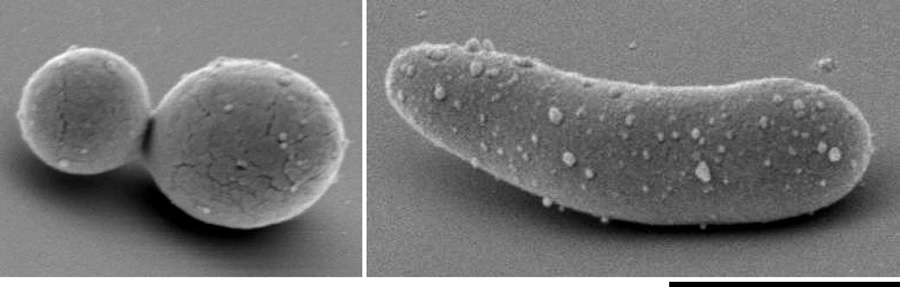

C. albicans cells typically exist as white cells but can transition to an alternative opaque state. The white-opaque switch was originally described in the clinical isolate WO-1 by Soll and colleagues165. White cells are round and generate bright, shiny colonies, while opaque cells are elongate and form greyer, flatter colonies165. The white-opaque transition is reversible and heritable. A complex between MTLa1 and MTLα2 proteins inhibits this switch, so that only a or α cells efficiently switch to the opaque state. Opaque cells are mating competent and secrete and respond to sexual pheromones to undergo efficient conjugation57,66,166. Repression of the switch by the MTL locus is relaxed under certain conditions, allowing a subset of natural a/α isolates to also undergo this transition167.

The transcriptional circuitry regulating the white-opaque switch has been described, and the master regulator of the opaque state is the Wor1 transcription factor. Formation of opaque cells is induced by expression of Wor1, and is stabilized by positive feedback of Wor1 on its own promoter168–171. The a1/α2 heterodimer inhibits Wor1 expression, thus limiting the ability of a/α cells to undergo this phenotypic switch172. Wor1 forms part of an integrated circuit containing transcription factors Wor2, Wor3, Czf1, Efg1, and Ahr1 that act to regulate the bistable switch171,173,174.

In addition to regulating mating, the white-opaque switch influences multiple aspects of C. albicans biology, including filamentation, metabolic regulation, biofilm formation, interactions with immune cells and virulence59,78,81,175,176. Furthermore, strains overexpressing Wor1 hypercolonize the murine gastrointestinal tract, and can undergo a distinct morphological transition to the GUT (gastrointestinally induced transition) phenotype177. It is therefore apparent that Wor1 and phenotypic switching play central role(s) in regulating the C. albicans lifestyle.

A similar phenotypic switch regulates the mating program of C. tropicalis and entry into this program is also Wor1-dependent68,178. However, the transcriptional circuits controlling the white-opaque switch have diverged between Candida species178. In addition, phenotypic switching in C. tropicalis is independent of MTL control, indicating that the switch may play an even broader role in the biology of this species178,179.

Having uncovered a sexual state in C. albicans, additional questions arose. What signals trigger switching to the opaque state? And is this switch regulated by conditions encountered in the host? It is now evident that the white-opaque transition is sensitive to many environmental cues that include starvation, haemoglobin, temperature, CO2, N-acetyl glucosamine (Glc-N-Ac), and genotoxic and oxidative stress (reviewed in 59,60). In the laboratory, opaque cells are unstable at 37°C and rapidly revert to the white state. However, conditions that stabilize the opaque state have been identified, including the presence of CO2 and Glc-N-Ac, suggesting that opaque cells can persist in some niches in the host61,62. Furthermore, high rates of white-to-opaque switching have been observed during passage of a clinical isolate through the mouse intestine, and this may be stimulated by anaerobic conditions in the gastrointestinal tract63. Mating of C. albicans cells has also been demonstrated in several in vivo models including systemic infection, as well as during colonization of the skin or intestine54,59,64,65.

The white-opaque switch evolved relatively recently in the Candida lineage, being limited to C. albicans, Candida dubliniensis and Candida tropicalis66–68. In each of these species, opaque forms are the mating-competent state, but the question arises as to why this switch evolved to regulate mating. It is likely that the requirement for cells to switch to the opaque state limits promiscuous sex and restricts mating to specific niches in the mammalian host69. In addition, the white-opaque switch may promote mating in vivo by regulating the formation of pheromone-induced ‘sexual biofilms’ (discussed below). Sexual reproduction in non-albicans Candida species is discussed in Box 3.

BOX 3. Sex in other pathogenic Candida species.

Genomic and experimental evidence indicates that the regulation of sexual reproduction has been rewired between Candida clade species13,16. In contrast to C. albicans, several Candida species exhibit complete sexual cycles culminating in meiosis and sporulation. For example, both Candida lusitaniae and Candida guilliermondii are heterothallic species that can mate and form meiotic ascospores16, despite lacking conserved genes that are central to meiosis in S. cerevisiae13,16. Moreover, in these Candida species meiosis is no longer under control of the a1/α2 complex as it is in S. cerevisiae, as C. lusitaniae has lost the α2 gene and C. guilliermondii has lost both a1 and α2 during evolution13,16. C. lusitaniae was also recently shown to have coupled mating and meiosis, enabling this pathogen to have only a transitory diploid stage180. These results again exemplify the plasticity in the regulatory mechanisms controlling sex and meiosis in fungal species.

In addition to C. albicans, the white-opaque transition has been observed in Candida dubliniensis67 and Candida tropicalis68,179. As in C. albicans, the Wor1 transcription factor controls phenotypic switching and mating in C. tropicalis, but also regulates other traits associated with pathogenesis including filamentous growth and biofilm formation178. In more distantly related ascomycetes such as S. cerevisiae and Histoplasma capsulatum, orthologs of Wor1 act as transcriptional regulators of filamentation181,182. The ancestral Wor1 protein therefore appears to have been a transcriptional regulator of morphogenesis, with the white-opaque switch having evolved relatively recently in the lineage leading to C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, and C. tropicalis178.

Candida parapsilosis is also a prevalent pathogen and a member of the Candida clade, but has not been shown to exhibit any sexual activity. Isolates are exclusively MTLa/a and the MTLa1 gene is a pseudogene, suggesting that the MTL locus might be degenerating in this species183. Two closely related species to C. parapsilosis are Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis, but only in the latter species is there a mixture of mating types suggesting the presence of an extant sexual cycle183.

Candida glabrata is more closely related to S. cerevisiae than to other Candida clade species, yet is often the second most commonly isolated species after C. albicans53. Despite its close relationship with S. cerevisiae, pheromone genes are not expressed in the majority of C. glabrata isolates and neither a nor α mating types respond to pheromone. Mating and meiosis have not been described for this species and the population structure is mostly clonal and thus it remains to be seen if sex occurs in this species184.

Scanning electron micrograph of white (left-hand panel) and opaque (right-hand panel) C. tropicalis cells courtesy of M. P. Hirakawa, Rhode Island, USA.

Parasex but no meiosis in C. albicans

Despite observations of efficient mating between diploid cells, a conventional meiosis has not been observed in C. albicans. In its place, tetraploid mating products undergo a parasexual process of concerted chromosome loss to generate diploid and aneuploid progeny39,56. Genetic recombination is observed in a subset of parasexual progeny and is dependent on Spo11, a conserved endodeoxyribonuclease required for meiotic recombination in diverse eukaryotes, indicating parallels between the parasexual cycle and a conventional meiosis39.

Could the parasexual cycle have specific benefits for the commensal lifestyle of C. albicans? A classical meiosis would be expected to generate spores, infectious particles that could be highly immunogenic in the host11. By contrast, generation of progeny via the parasexual cycle allows for a reduction in ploidy and recombination between chromosome homologs, yet avoids potentially harmful spore formation. In addition, chromosomal aneuploidies are formed at high frequency by parasex and can generate additional phenotypic diversity, including the potential formation of drug-resistant isolates70–72. It remains to be seen if the parasexual pathway is the only mechanism by which a mating cycle can be completed in C. albicans, or if a cryptic meiosis remains to be discovered.

In a recent development, Hickman et al. reported the surprising isolation of haploid strains of C. albicans73. Long thought to be unable to form a viable haploid state, rare haploid cells were recovered from both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Haploid cells were fully competent to undergo the white-opaque switch and could mate to re-generate diploid cells. Haploid cells were the products of parasexual chromosome loss, and exhibited fitness defects consistent with the unmasking of recessive mutations73. The existence of a haploid state provides a potentially exciting new tool with which to study C. albicans biology, and further underlines the extensive karyotypic plasticity exhibited by this pathogen.

Pheromone signalling, biofilm formation and sex in C. albicans

C. albicans mating appears to be rare in nature, as the population structure is clonal with only limited evidence of recombination74,75. It is possible that stressful conditions (such as oxidative stress or antifungal drugs) stimulate the parasexual cycle, as stressors can promote loss of heterozygosity at the MTL locus, white-to-opaque switching, and concerted chromosome loss70,76. This is also consistent with theoretical models of sex, as organisms are predicted to undergo mating more often when stressed, and stress-induced recombination can facilitate adaptation under stress70. In the case of C. albicans, expression of MTL genes could also be regulated by environmental factors in such a way that a/α cells behave phenotypically as a or α cells; this could enable mating in populations previously thought to be unable to undergo sexual reproduction77. Pheromone signalling could also impact pathogenesis, as C. albicans white cells mount a novel response to mating pheromones secreted by opaque cells. While opaque cells respond to pheromone by forming mating projections and undergoing conjugation (FIG. 1), white cells respond by upregulating genes involved in adhesion and biofilm formation78–81. Such ‘sexual’ biofilms allow for stable formation of pheromone gradients between mating partners, enabling opaque cells to locate one another and mate more efficiently78,82. Since biofilms are important in establishing infections by Candida species83, the formation of sexual biofilms could directly promote infection in the host84.

C. albicans white and opaque cells have also been shown to respond to pheromones from closely related species85. Pheromones from non-albicans Candida species were able to induce biofilm formation in C. albicans white cells, as well as same-sex mating in C. albicans opaque cells85. The pheromone-receptor interaction therefore displays surprising plasticity, further broadening the potential conditions under which pheromone signalling, mating, and/or biofilm formation might occur in nature.

Sexual reproduction in Cryptococcus species

C. neoformans is a basidiomycete yeast associated with soil, trees, and pigeon guano. During infection, Cryptococcus spores or desiccated yeast cells are inhaled and lodge in lung alveoli, from which the organism is either cleared or establishes a latent infection86. Subsequent immunosuppression leads to reactivation of the latent fungus followed by dissemination to the central nervous system (CNS) resulting in meningoencephalitis3,86. Three varieties of Cryptococcus are responsible for cryptococcosis and these have been classified based on their capsular aggregation reactions and genome sequences. The majority of infections (95% worldwide) are due to C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A)87, while <5% of infections are caused by C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D). A hybrid serotype, AD, also exists and may be more pathogenic than serotype D alone88. While these varieties infect predominantly immunocompromised individuals, C. gattii strains (serotypes B and C), found largely in tropical regions, can infect immunocompetent, healthy individuals.

C. neoformans strains are heterothallic, with both a and α mating types capable of causing disease, although the majority of clinical isolates are MATα strains37. Unlike most basidiomycetes where mating is regulated by a tetrapolar mating locus86, the MAT locus of C. neoformans is bipolar and encodes homeodomain proteins, pheromones, and pheromone receptors, which all contribute to cell identity89–91. Mating in C. neoformans and C. gattii was reported almost four decades ago and involves fusion of a and α cells to produce dikaryotic filaments (FIG. 2)30,92. Following nuclear fusion and meiosis, long chains of sexual basidiospores are produced containing recombinant haploid nuclei30,92,93.

Although heterothallic mating of C. neoformans strains was observed in the laboratory, it remained an open question as to how mating could occur in nature where the majority (>98%) of isolates are of the α mating type. For C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A), it became apparent that while MATα strains are distributed worldwide, the a mating type is restricted to sub-Saharan Africa where there is evidence for recent or ongoing sexual recombination94,95. Studies of mating in this serotype have shown that var grubii strains have mating specificity beyond a and α mating types, and this may further promote inbreeding of more highly adapted, pathogenic strains96.

In the case of hybrid AD serotypes, these are the result of mating between intervarietal strains and often contain both mating types (e.g., aADα or αADa)31,32. These hybrids germinate poorly to produce diploid or aneuploid products, suggesting that the sexual cycle is inefficient in crosses between C. neoformans var grubii and var neoformans.

Same-sex mating in Cryptococcus

C. neoformans strains had been known to undergo a program of monokaryotic fruiting, during which cells formed filaments and underwent sporulation97. Originally thought to be an asexual program, Lin et al. demonstrated that fruiting α cells underwent same-sex fusion to form α/α diploids, and that these subsequently sporulated to produce recombinant haploid spores (FIG. 2)33. Progeny formation was dependent on Spo11 and Dmc1, two conserved proteins necessary for the formation and repair of meiotic DNA double-strand breaks in yeasts and mammals33,98.

Analysis of natural isolates of C. neoformans has since confirmed the existence of α/α diploids and αA/Dα hybrids, indicating that same-sex mating occurs in nature34,99,100. This strategy allows for inbreeding and recombination to occur even in geographical regions where only one mating type is present. While both a and α strains of C. neoformans undergo monokaryotic fruiting101, the MATα locus enhances hyphal growth and this ability could further contribute to the prevalence of α isolates in nature102.

Unisexual mating between two closely related α isolates of C. gattii is thought to have produced a highly virulent strain responsible for an ongoing outbreak that initiated on Vancouver Island, British Columbia35,103. The outbreak is associated with high mortality rates (>25%) in both healthy and immunosuppressed individuals, as well as in domestic and wild animals103. Since the first cases were reported, the outbreak has spread into the Pacific Northwest of the US and Canada36,103,104. Numerous genotypes are responsible for these infections but the major genotype, VGIIa, is the presumed product of a homothallic mating event between closely related isolates of the VGII type35. The VGIIa isolates are highly virulent in animal models of infection35,36, yet how this infection emerged from Vancouver Island remains to be determined.

Mating and virulence in Cryptococcus

Do sex and mating type impact pathogenicity? Several lines of evidence suggest there is a close connection between mating type, sexual reproduction and virulence in Cryptococcus. First, sexual specification has been directly linked to virulence in serotype D isolates, with α cells being more virulent than a cells105 (FIG. 2). Genes from outside of the MAT locus interact with genes from within the α locus to direct pathogenesis96,106. The two mating types also differ in their interactions with the mammalian host; C. neoformans var. grubii α isolates are better able to disseminate through the CNS than congenic a isolates107. Moreover, sexual reproduction can generate new variants that are hypervirulent in the host, such as those responsible for the Vancouver Island outbreak. Sexual spores of C. neoformans can also act as infectious particles, leading to high mortality rates in a murine inhalation model of infection108,109. Spores might be more successful at causing infection than yeast cells as they are highly resistant to a variety of environmental stresses110,111.

Another mechanism by which mating can impact virulence is via the pheromone induction of specialized cell types. Pheromone signalling has been shown to promote formation of titan cells by C. neoformans112,113. Titan cells can reach 50–100 µm in diameter, which is 5–10 times larger than that of a typical cryptococcal cell. These giant cells are polyploid (4N–64N), are resistant to phagocytosis by macrophages, and promote the virulence of C. neoformans in a mammalian model of infection114,115. Taken together, it is therefore apparent that mating and virulence are interconnected processes in C. neoformans and C. gattii.

A sexual revolution in Aspergillus

The majority of Aspergillus infections are associated with immunodeficiency and involve pulmonary aspergillosis, which can often develop into infection of the CNS116,117. The most common causative agent for these infections is the ascomycete A. fumigatus, which is widely found in the soil and decaying materials118. The primary mode of reproduction is the formation of conidia (asexual spores) that are easily dispersed in the environment and can survive a wide range of conditions.

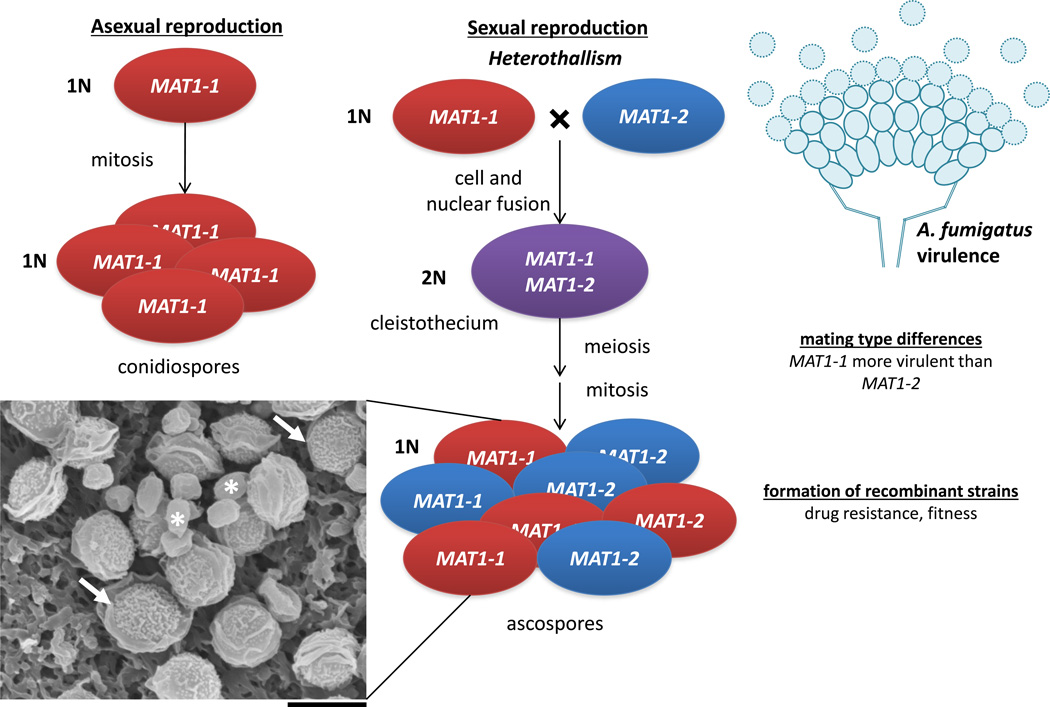

Originally thought to be an asexual fungus, genome sequencing of A. fumigatus revealed the presence of multiple genes implicated in sexual reproduction119–121. Along with the mating type locus, genes encoding putative pheromones, receptors, and pheromone signalling components were identified120–122. The functionality of A. fumigatus MAT-encoded proteins was first demonstrated in complementation assays using A. nidulans, while also revealing significant differences between the two species123,124. A. fumigatus mating types are present in equal ratios in the environment, and there is evidence for recombination in the population, suggesting that mating occurs in nature125,126. However, it was not until 2009 that O’Gorman et al. demonstrated productive mating of A. fumigatus in the laboratory. These experiments involved extended incubation (>6 months) of strains on oatmeal agar medium in the dark127 (FIG. 3). The prohibitive conditions raised the question as to where in the environment A. fumigatus might undergo sexual development and whether it might be evolving into an asexual organism125,128. Follow-up studies showed that A. fumigatus isolates from invasive aspergillosis patients could mate in less stringent conditions (coculture for >6 weeks at 30°C) and a “supermater” pair was subsequently identified129,130. MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs act as master regulators of A. fumigatus mating by controlling the expression of pheromone and pheromone receptor genes129.

Figure 3.

Sexual and asexual reproduction in A. fumigatus. A. fumigatus undergoes asexual reproduction via the mitotic division of haploid cells or the formation of asexual conidiospores. It can also undergo heterothallic mating between MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 mating types. The products of mating are cleistothecia (ascocarps) that contain multiple ascospores. Sexual reproduction and virulence are linked in A. fumigatus as specified on the right side of the figure. Note that sex influences virulence in all three species (see FIGS. 1 and 2) by generating recombinant strains with novel properties or through mating-type differences. However, some traits are species-specific, such as the ability of C. albicans to form pheromone-induced biofilms, or titan cell formation in C. neoformans. Inset, scanning electron micrograph showing A. lentulus cleistothecia (white arrows) with emerging ascospores (white asterisk) (gift of Celine M. O'Gorman and Paul Dyer, scale bar = 5 µm).

Does A. fumigatus mating impact pathogenesis? Similar to C. neoformans, the mating types of A. fumigatus differ in their propensities to cause infection, with the MAT1-1 mating type associated with increased invasive growth and increased virulence131,132. Moreover, the discovery of a sexual cycle implies that recombination could yield progeny with increased virulence and/or altered antifungal resistance (FIG. 3).

Mating in other Aspergillus species

Many aspects of the life cycle of Aspergillus species have been extensively studied using A. nidulans, a species that displays a homothallic life cycle and is usually non-pathogenic133,134. Similar to A. fumigatus, mating is regulated by two MAT genes, MAT1-1 and MAT1-2, encoding an α-box domain protein and an HMG domain protein, respectively133. Overexpression of these genes induced sexual development in A. nidulans, suggesting that the transition from a homothallic to a heterothallic life cycle (or vice versa) can occur by rewiring of MAT regulation alone133,134.

Sexual cycles have also been uncovered in Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. These species are plant pathogens as well as the primary producers of aflatoxin, a mycotoxin posing a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, particularly in Africa and Asia135. A. flavus is also an important human pathogen in its own right, causing both invasive and noninvasive aspergillosis136. MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs are present in both Aspergillus species and are found in equal ratios in the environment, supporting the existence of sexual reproduction in the wild63. A. flavus and A. parasiticus undergo heterothallic mating resulting in the development of ascospore-bearing ascocarps137,138.

A heterothallic mating program has also been uncovered in Aspergillus lentulus, a close sibling of A. fumigatus (FIG. 3)139. A. lentulus is an emerging human fungal pathogen causing invasive aspergillosis with high mortality rates in immunocompromised patients and that exhibits decreased susceptibility to antifungal drugs140. Thus, another supposedly asexual species undergoes a cryptic sexual cycle and hence has the potential to rapidly evolve under selective pressure.

Sex in other human fungal pathogens

Among the ascomycetes, several filamentous species are associated with human disease, including Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Coccidioides posadasii, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Penicillium marneffei, Paraccoccidioides brasilienis, and Sporothrix schenckii (Supplementary information S3). While most of these species grow as moulds in the environment, the increase in temperature experienced during human infection triggers the switch to the pathogenic yeast state141.

Coccidioidomycosis (or Valley Fever) is primarily caused by inhalation of arthroconidia of the ascomycetes C. immitis and C. posadasii. These species are commonly found in the soil of arid regions of the US, Mexico, and Central and South America, and cause progressive pulmonary and disseminated disease in otherwise healthy individuals142. Genomic analysis has revealed a single mating type locus encoding an HMG (high-mobility-group)-box protein, MAT1-2-1, although a complete sexual cycle has not yet been defined for either C. immitis or C. posadasii143. Population genetics suggests that sexual reproduction occurs in both species, but with no interspecies flow between them144.

H. capsulatum is closely related to Coccidioides and is ubiquitous in the soil where it generates asexual microconidia that, when inhaled, cause histoplasmosis145. The sexual cycle of this ascomycete was defined decades ago and mating types (designated as + and −) are found at equal ratios in the environment, supportive of a sexual cycle146,147. In humans only the − mating type causes infection, although the two mating types do not differ in their abilities to cause infection in a murine model148.

Pneumocystis jiroveci is an airborne ascomycete which can drive a lethal pulmonary infection in immunocompromised individuals149. Pneumocystis species have not been cultivated in vitro and thus observations regarding their life cycles have been made based on cells in infected lung tissue. The life cycle is thought to include both a sexual phase and an asexual phase149. Genome sequencing of this organism revealed a cluster of genes potentially involved in pheromone sensing and signalling, which could represent a putative mating type locus in this species150.

Recently, a MAT locus was identified in the ascomycete Blastomyces dermatitidis151. This dimorphic fungal pathogen is the leading cause of blastomycosis, causing severe respiratory and disseminated disease in immunocompetent humans. Distribution of mating types and population genetics studies suggest that B. dermatitidis might reproduce sexually, but the mating-type locus had not been described152,153. The identification of the B. dermatitidis MAT revealed that, unlike the MAT loci of other dimorphic fungi, it contains transposable elements (TEs) that make it unusually large and may increase sequence diversity between the two MAT idiomorphs while decreasing recombination within this region151. It remains unclear, however, if this fungus undergoes sexual reproduction in nature and, if so, whether the resulting sexual spores are infectious.

Among the Penicillium species, P. marneffei stands out as being thermally dimorphic and can cause lethal systemic infections similar to disseminated cryptococcosis. P. marneffei displays a pattern of extreme clonality, being genetically and spatially restricted, and endemically associated with AIDS in Southeast Asia154,155. Two mating loci have been identified in P. marneffei and they seem to be widely distributed among isolates, suggesting that a heterothallic sexual cycle remains to be discovered156. Although there is considerable evidence to suggest sexual recombination in this organism, it appears limited to genetically similar and spatially close mating partners and selfing may occur in this species157.

While most fungal species (~95%) belong to the subkingdom Dikarya (consisting of ascomycetes and basidiomycetes), other fungal phyla also include relevant human pathogens. For example, the phylum of Zygomycota includes Mucor circinelloides, which has defined mating types designated as + and −. These mating types encode SexP and SexM, respectively, the HMG domain sex-determining proteins158. M. circinelloides is an emerging opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised populations. Mating types differ in spore size and virulence with the − mating type producing larger asexual spores that are more virulent in murine infection and more resistant to phagocytosis by macrophages158.

Finally, we note that the phylum of Microspora is also considered to belong to true fungi (or to be a close sister group to his kingdom). Microsporidia are obligate intracellular parasites that infect both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts, and cause gastrointestinal disease in humans, as well as infections of other organs159. In this phlyum evidence for sexual reproduction is again emerging; microsporidia contain a MAT-related locus similar to that in zygomycetes160,161 and some species contain highly heterozygous genomes, potentially arising as a direct consequence of outcrossing162. One recent study also found homozygous isolates, suggestive of selfing in the population163. It therefore appears that diverse sexual strategies can be found across the fungal kingdom.

Fungal sex in the context of disease

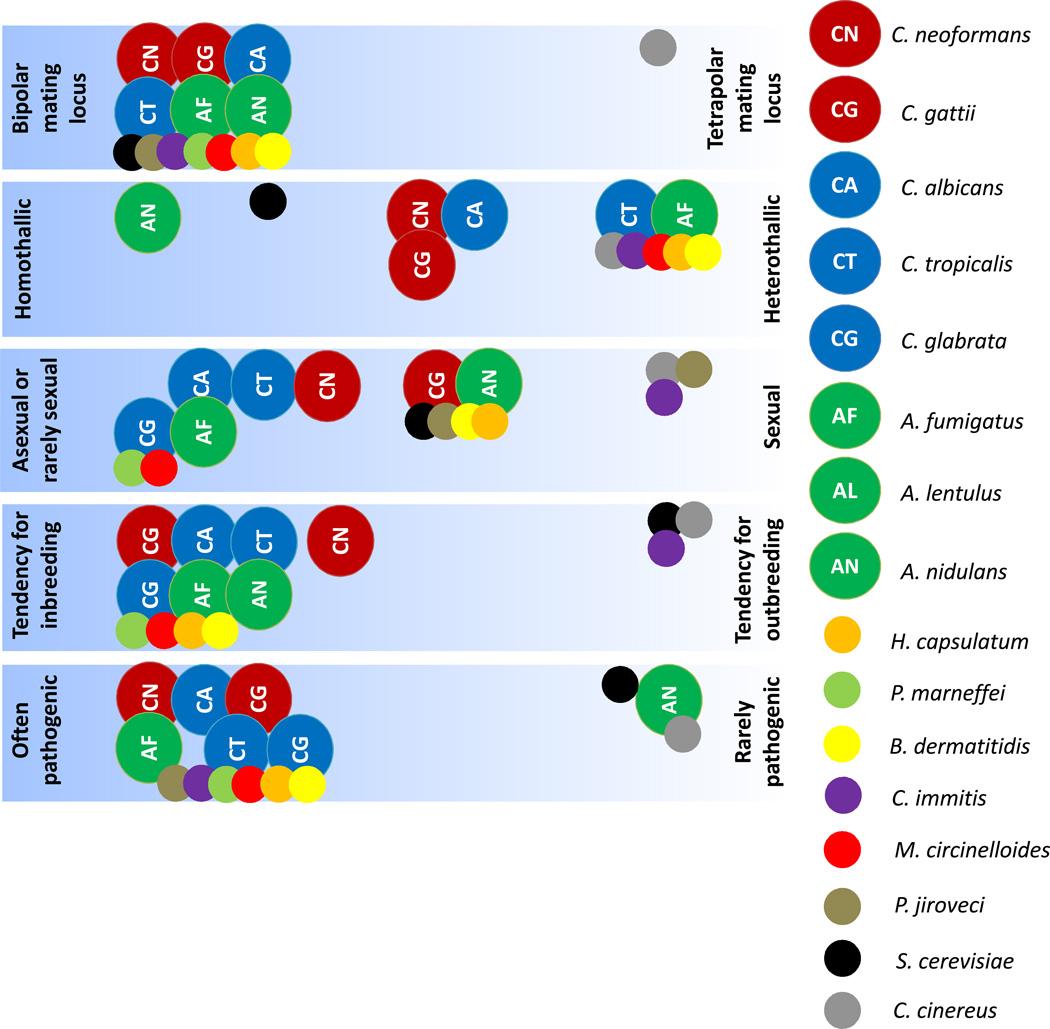

What have we learned from studying sex in human fungal pathogens? Many of the assumed advantages of sex revolve around the ability to increase genetic diversity, despite the associated costs and the fact that recombination can disrupt well-adapted combinations of alleles164. In pathogenic species these costs could prove prohibitive. This perhaps explains why prevalent human fungal pathogens have preserved the apparatus for sexual reproduction, but have restricted the use of these programs. Thus, these species generate largely clonal populations but still have the ability to undergo sexual reproduction if dictated by environmental conditions (FIG. 4). Furthermore, the fact that two major pathogens, C. albicans and C. neoformans, undergo both heterothallic and homothallic mating illustrates a paradigm that has emerged from studies of parasites – microbial pathogens may transition from outbreeding to inbreeding lifecycles as they evolve into prevalent pathogens (FIG. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of sexual reproduction and virulence leads to emerging trends among human fungal pathogens. Some of the most prevalent pathogenic species tend to promote inbreeding, have restricted and highly specialized sexual cycles, contain bipolar mating loci, and often include the potential for homothallic reproduction. S. cerevisiae and C. cinereus have been included as model organisms for ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, respectively. Members of the most commonly isolated genera - Candida, Cryptococcus and Aspergillus - are marked with larger symbols in blue, red and green, respectively. Where possible we have assigned positions for the less well-studied species.

Despite the fact that many of these species appear to limit sexual reproduction, we now recognize that sex and sex-associated programs have important consequences for pathogenesis. Mating types can differ in virulence, as well as in their ability to evade the host immune response; sexual spores can act as infectious particles or can promote persistence by resisting host stresses; recombinant progeny can exhibit increased resistance to antifungal drugs; pheromone signalling can promote formation of biofilms and filamentous growth. Moreover, genetic variation resulting from sex can mediate the formation of hypervirulent strains. Therefore, even when rare, recombination events can dictate shifts in the lifestyles of these species and their effects can persist in subsequent clonal lineages. Indeed, as genetic and genomic tools become increasingly available, sexual cycles are likely to be uncovered in many other ‘asexual’ fungi.

Pressing questions concerning the sex lives of human fungal pathogens remain. How do these species regulate the balance between inbreeding and outbreeding? How often do fungal pathogens mate in nature and what niches support their sexual cycles? How are sexual cycles regulated by host cues? For those species that are human commensals, does their sexual behaviour modulate the balance between commensalism and virulence? What mechanisms underlie the differences in virulence between cell mating types and how do altered ploidy states influence virulence?

Given the diversity of mechanisms found to regulate sex, it is likely that new paradigms remain to be discovered, similar to the white-opaque switch in C. albicans and monokaryotic fruiting (same-sex mating) in C. neoformans. It is therefore apparent that studies of fungal sex will continue to enhance our understanding of these important pathogens, and will uncover novel biological mechanisms that have evolved to regulate entry and passage through the sexual cycle.

Supplementary Material

Online summary.

Sexual reproduction is a common attribute of eukaryotes owing to its potential to generate variability among individuals and provide an advantage over species that are strictly asexual. Human pathogens are in a constant arms race with their hosts and sexual reproductive strategies enable these species to keep up in the evolutionary arms race.

Accumulating genetic evidence suggests that the majority of human fungal pathogens retain sexual reproductive machinery and recent studies into their life cycles have detailed the sexual programs of these fungi. It is becoming evident that most, it not all, of these species undergo cryptic sex.

We discuss the sexual cycles of three of the most prominent human pathogens - C. albicans, C. neoformans and A. fumigatus. While the main tenets of sex are conserved, these species exhibit specialised sexual programs, including transitions from heterothallism to homothallism, and from sexual to parasexual reproduction, rendering an enigmatic aspect to fungal sexual cycles.

While most fungal pathogens have retained the ability to mate, these species appear to promote inbreeding and conservation of highly adapted pathogenic strains, resulting in largely clonal populations.

Sexual reproduction in these species can directly impact pathogenesis, through the generation of genetic variants, the emergence of drug resistant isolates, or the modulation of interactions with host cells. The mechanisms regulating fungal sex, as well as the consequences of these specialized programs for host-pathogen interactions are important as they reveal strategies that allow fungi to survive, mate, colonise and infect the mammalian host.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joseph Heitman for comments and suggestions on the manuscript. We also thank Matthew Hirakawa, Edmond Byrnes, Joseph Heitman, Celine O’Gorman and Paul Dyer for providing scanning electron micrographs. I.V.E. is supported by a Vessa Notchev Fellowship from the SDE-Graduate Women in Science. Work in the author’s laboratory is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant AI081704 and by the National Science Foundation grant 1021120 to R.J.B. R.J.B. also holds an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Glossary

- Aneuploidy

Change in chromosome copy number that does not parallel a change in the entire haploid or diploid genome.

- Ascomycetes

Largest division in the kingdom of Fungi, commonly known as sac fungi. Their name stems from their defining sexual feature ascus (ascocarp or cleistothecium) which is where nuclear fusion and meiosis takes place, resulting in the formation of ascospores.

- Basidiomycetes

One of the two large phyla of Fungi typically referred to as higher fungi. Most commonly they are filamentous fungi that reproduce sexually by forming round-shaped cells termed basidia which bear external basidiospores.

- Biofilm

A complex community of microorganisms that are most commonly found in the host attached to a prosthetic surface. Cells adhere to the surface and to each other and promote the formation of extracellular matrix that protects the biofilm community from external stress (e.g. antifungal drugs).

- Candida clade

In the phylogenetic tree, members of this group share an altered genetic code, in which the CUG codon is translated as leucine as opposed to serine as in the universal genetic code. This group includes most pathogenic Candida species, except for C. glabrata, which is more closely related to S. cerevisiae (Supplementary information S3).

- Commensalism

Close relationship between two organisms where one organism (the commensal) benefits without affecting its host. The term is derived from Medieval Latin, where ‘commensalis’ signifies ‘sharing a table’.

- Dimorphic fungi

Fungi that can exist as single cells (yeast) or in a hyphal/filamentous form. Morphological transitions such as the yeast-hyphal transition are typically driven by an array of environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, pH). Some of the most prominent fungal pathogens employ a dimorphic life style – C. albicans, P. marneffei, C. immitis, B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis etc.

- Extant

Still in existence; not destroyed, lost, or extinct.

- HMG-box

High mobility group-box, protein domain involved in DNA-binding.

- Homeodomain

A 60 amino acid protein domain that folds into a helix-turn-helix compact structure and binds DNA. Homeodomain folds are commonly found in transcription factors and they are exclusively eukaryotic where they induce cellular differentiation.

- Idiomorph

In fungal biology, idiomorphs, rather than alleles, are used to describe distinct mating type genes because they generally lack homology and do not appear to share an obvious ancestry.

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinases or MAP kinases are serine/threonine-specific protein kinases that signal cellular responses to a wide range of stimuli, including pheromones, mitogens, osmotic or heat stress, and proinflammatory cytokines.

- MAT

mating-type

- MTL

mating-type like

- Muller’s ratchet

refers to the accumulation of deleterious mutations in asexual populations which becomes so great that leads to the extinction of the population.

- Zygomycete

Phylum of fungi whose name derives from zygospores, resistant spherical spores formed during mating. Species include Mucor circinelloides and Rhizopus stolonifer, the black bread mold.

Biographies

Iuliana V. Ene is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Brown University. She completed her graduate studies in Molecular Biology at University of Aberdeen, UK and holds a Vessa Notchev Fellowship from the SDE-Graduate Women in Science. She is interested in understanding the impact of niche signalling on the parasexual cycle of C. albicans.

Richard J. Bennett is an Associate Professor at Brown University. He did postdoctoral studies at Harvard University and at the University of California, San Francisco, prior to starting his own laboratory at Brown. He is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in Infectious Disease. His laboratory is focused on studying the mechanisms of sexual reproduction in Candida species and their impact on pathogenesis.

References

- 1. Van Valen L. A new evolutionary law. Evol. Theory. 1973;1:1–30. Proposed the Red Queen Hypothesis.

- 2.Heitman J. Evolution of eukaryotic microbial pathogens via covert sexual reproduction. Cell. Host Microbe. 2010;8:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heitman J, Sun S, James TY. Evolution of fungal sexual reproduction. Mycologia. 2013;105:1–27. doi: 10.3852/12-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lively CM. A review of Red Queen models for the persistence of obligate sexual reproduction. J. Hered. 2010;101(Suppl 1):S13–S20. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jokela J, Dybdahl MF, Lively CM. The maintenance of sex, clonal dynamics, and host-parasite coevolution in a mixed population of sexual and asexual snails. Am. Nat. 2009;174(Suppl 1):S43, S53. doi: 10.1086/599080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morran LT, Schmidt OG, Gelarden IA, Parrish RC, 2nd, Lively CM. Running with the Red Queen: host-parasite coevolution selects for biparental sex. Science. 2011;333:216–218. doi: 10.1126/science.1206360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paterson S, et al. Antagonistic coevolution accelerates molecular evolution. Nature. 2010;464:275–278. doi: 10.1038/nature08798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulte RD, Makus C, Schulenburg H. Host-parasite coevolution favours parasite genetic diversity and horizontal gene transfer. J. Evol. Biol. 2013;26:1836–1840. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyabuga FN, Loxdale HD, Heckel DG, Weisser WW. Coevolutionary fine-tuning: evidence for genetic tracking between a specialist wasp parasitoid and its aphid host in a dual metapopulation interaction. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2012;102:149–155. doi: 10.1017/S0007485311000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhan J, Mundt CC, McDonald BA. Sexual reproduction facilitates the adaptation of parasites to antagonistic host environments: Evidence from empirical study in the wheat-Mycosphaerella graminicola system. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007;37:861–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.03.003. This study explores the Red Queen hypothesis from the point of view of the pathogen.

- 11.Heitman J. Sexual reproduction and the evolution of microbial pathogens. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R711–R725. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen K, Heitman J. Sex and virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Adv. Genet. 2007;57:143–173. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(06)57004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butler G, et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature. 2009;459:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. Genome analysis of multiple species in the Candida clade revealed extensive rewiring of the regulation of mating and meiosis in these species.

- 14.Lee SC, Ni M, Li W, Shertz C, Heitman J. The evolution of sex: a perspective from the fungal kingdom. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:298–340. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schurko AM, Logsdon JM., Jr Using a meiosis detection toolkit to investigate ancient asexual "scandals" and the evolution of sex. Bioessays. 2008;30:579–589. doi: 10.1002/bies.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reedy JL, Floyd AM, Heitman J. Mechanistic plasticity of sexual reproduction and meiosis in the Candida pathogenic species complex. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.058. This investigation established that a complete sexual cycle occurs in Candida lusitaniae, despite lacking conserved genes often considered to be essential for meiosis.

- 17.Fraser JA, Heitman J. Chromosomal sex-determining regions in animals, plants and fungi. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones SK, Jr, Bennett RJ. Fungal mating pheromones: choreographing the dating game. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011;48:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengeler KB, et al. Mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: a step in the evolution of sex chromosomes. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:704–718. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.5.704-718.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser JA, et al. Chromosomal translocation and segmental duplication in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:401–406. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.401-406.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsueh YP, Fraser JA, Heitman J. Transitions in sexuality: recapitulation of an ancestral tri- and tetrapolar mating system in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1847–1855. doi: 10.1128/EC.00271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser JA, Heitman J. Evolution of fungal sex chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:299–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsueh YP, Idnurm A, Heitman J. Recombination hotspots flank the Cryptococcus mating-type locus: implications for the evolution of a fungal sex chromosome. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun S, Hsueh YP, Heitman J. Gene conversion occurs within the mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans during sexual reproduction. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srikantha T, et al. Nonsex genes in the mating type locus of Candida albicans play roles in a/alpha biofilm formation, including impermeability and fluconazole resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002476. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Findley K, et al. Discovery of a modified tetrapolar sexual cycle in Cryptococcus amylolentus and the evolution of MAT in the Cryptococcus species complex. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibayrenc M, Kjellberg F, Ayala FJ. A clonal theory of parasitic protozoa: the population structures of Entamoeba, Giardia, Leishmania, Naegleria, Plasmodium, Trichomonas, and Trypanosoma and their medical and taxonomical consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:2414–2418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magwene PM, et al. Outcrossing, mitotic recombination, and life-history trade-offs shape genome evolution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:1987–1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012544108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alby K, Schaefer D, Bennett RJ. Homothallic and heterothallic mating in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Nature. 2009;460:890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature08252. The first demonstration that C. albicans could undergo same-sex homothallic mating as well as opposite-sex heterothallic mating.

- 30. Kwon-Chung KJ. Morphogenesis of Filobasidiella neoformans, the sexual state of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycologia. 1976;68:821–833. Along with reference 92, these studies provided the initial description of the C. neoformans sexual cycle.

- 31.Lengeler KB, Cox GM, Heitman J. Serotype AD strains of Cryptococcus neoformans are diploid or aneuploid and are heterozygous at the mating-type locus. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:115–122. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.115-122.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cogliati M, Esposto MC, Clarke DL, Wickes BL, Viviani MA. Origin of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans diploid strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:3889–3894. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.3889-3894.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. This paper established that monkaryotic fruiting in C. neoformans actually represents a novel form of unisexual α-α mating in this species.

- 34.Bui T, Lin X, Malik R, Heitman J, Carter D. Isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from infected animals reveal genetic exchange in unisexual, alpha mating type populations. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1771–1780. doi: 10.1128/EC.00097-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fraser JA, et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–1364. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. Demonstrated that the major genotype responsible for an outbreak of C. gattii that initiated on Vancouver Island was due to the formation of a hypervirulent strain produced via same-sex mating.

- 36.Byrnes EJ, 3rd, et al. Emergence and pathogenicity of highly virulent Cryptococcus gattii genotypes in the northwest United States. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. Distribution of alpha and alpha mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans among natural and clinical isolates. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1978;108:337–340. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoustra SE, Debets AJ, Slakhorst M, Hoekstra RF. Mitotic recombination accelerates adaptation in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forche A, et al. The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ni M, et al. Unisexual and heterosexual meiotic reproduction generate aneuploidy and phenotypic diversity de novo in the yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Biol. 2013;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001653. 39, 40 These studies demonstrate that the sexual cycles of C. albicans and C. neorformans result in the generation of recombinant progeny with diverse phenotypes.

- 41.Morrow CA, Fraser JA. Ploidy variation as an adaptive mechanism in human pathogenic fungi. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;24:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selmecki A, Bergmann S, Berman J. Comparative genome hybridization reveals widespread aneuploidy in Candida albicans laboratory strains. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1553–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sionov E, Lee H, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ. Cryptococcus neoformans overcomes stress of azole drugs by formation of disomy in specific multiple chromosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000848. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres EM, et al. Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science. 2007;317:916–924. doi: 10.1126/science.1142210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rancati G, et al. Aneuploidy underlies rapid adaptive evolution of yeast cells deprived of a conserved cytokinesis motor. Cell. 2008;135:879–893. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni M, Feretzaki M, Sun S, Wang X, Heitman J. Sex in fungi. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phadke SS, Feretzaki M, Heitman J. Unisexual Reproduction Enhances Fungal Competitiveness by Promoting Habitat Exploration via Hyphal Growth and Sporulation. Eukaryot. Cell. 2013;12:1155–1159. doi: 10.1128/EC.00147-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howe DK, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma gondii comprises three clonal lineages: correlation of parasite genotype with human disease. J. Infect. Dis. 1995;172:1561–1566. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wendte JM, et al. Self-mating in the definitive host potentiates clonal outbreaks of the apicomplexan parasites Sarcocystis neurona and Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poxleitner MK, et al. Evidence for karyogamy and exchange of genetic material in the binucleate intestinal parasite Giardia intestinalis. Science. 2008;319:1530–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1153752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon MW, Thompson J, Gardiner DL, Trenholme KR. Sex in Plasmodium: a sign of commitment. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu J. In: Sex in fungi. Heitman J, Kronstad JW, Taylor JW, Casselton LA, editors. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2007. pp. 461–475. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;36:1–53. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evidence for mating of the "asexual" yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. Along with reference 55, the first demonstration that C. albicans could undergo sexual mating using strains inoculated into a mouse model of systemic infection.

- 55. Magee BB, Magee PT. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLalpha strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. Together with reference 54, this study showed that C. albicans strains could mate, in this case using strains co-incubated on laboratory agar.

- 56. Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. EMBO J. 2003;22:2505–2515. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg235. Demonstrated that C. albicans tetraploid cells can undergo a parasexual program of chromosome loss in place of meiosis to return to the diploid state.

- 57.Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Mating in Candida albicans and the search for a sexual cycle. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;59:233–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hull CM, Johnson AD. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science. 1999;285:1271–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1271. This study provided the first clue towards the discovery of a C. albicans sexual cycle – identification of a mating type-like locus.

- 59.Morschhauser J. Regulation of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;199:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang G. Regulation of phenotypic transitions in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Virulence. 2012;3 doi: 10.4161/viru.20010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang G, Srikantha T, Sahni N, Yi S, Soll DR. CO(2) regulates white-to-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang G, et al. N-acetylglucosamine induces white to opaque switching, a mating prerequisite in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000806. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramirez-Zavala B, Reuss O, Park YN, Ohlsen K, Morschhauser J. Environmental induction of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000089. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lachke SA, Lockhart SR, Daniels KJ, Soll DR. Skin facilitates Candida albicans mating. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:4970–4976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4970-4976.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dumitru R, et al. In vivo and in vitro anaerobic mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:465–472. doi: 10.1128/EC.00316-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miller MG, Johnson AD. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell. 2002;110:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00837-1. Demonstrated that the mating-type-like locus controlled the white-opaque phenotypic switch in C. albicans, and opaque cells represent the mating-competent form of the species.

- 67.Pujol C, et al. The closely related species Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis can mate. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:1015–1027. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.1015-1027.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Porman AM, Alby K, Hirakawa MP, Bennett RJ. Discovery of a phenotypic switch regulating sexual mating in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:21158–21163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson A. The biology of mating in Candida albicans. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:106–116. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berman J, Hadany L. Does stress induce (para)sex? Implications for Candida albicans evolution. Trends Genet. 2012;28:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Selmecki A, Forche A, Berman J. Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science. 2006;313:367–370. doi: 10.1126/science.1128242. This paper revealed that chromosome aneuploidy drives increased drug resistance in clinical isolates of C. albicans.

- 72.Selmecki A, Gerami-Nejad M, Paulson C, Forche A, Berman J. An isochromosome confers drug resistance in vivo by amplification of two genes, ERG11 and TAC1. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:624–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hickman MA, et al. The 'obligate diploid' Candida albicans forms mating-competent haploids. Nature. 2013;494:55–59. doi: 10.1038/nature11865. The first demonstration of a viable haploid state for C. albicans.

- 74.Graser Y, et al. Molecular markers reveal that population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:12473–12477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tibayrenc M. Are Candida albicans natural populations subdivided? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:253–254. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01068-8. discussion 254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Forche A, et al. Stress alters rates and types of loss of heterozygosity in Candida albicans. MBio. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00129-11. Print 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pendrak ML, Yan SS, Roberts DD. Hemoglobin regulates expression of an activator of mating-type locus alpha genes in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:764–775. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.764-775.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Daniels KJ, Srikantha T, Lockhart SR, Pujol C, Soll DR. Opaque cells signal white cells to form biofilms in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 2006;25:2240–2252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601099. This study demonstrates the role of white and opaque cells in the formation of 'sexual biofilms'.

- 79.Chen J, Chen J, Lane S, Liu H. A conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:1335–1344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soll DR. Candida biofilms: is adhesion sexy? Curr. Biol. 2008;18:R717–R720. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin CH, et al. Genetic control of conventional and pheromone-stimulated biofilm formation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park YN, Daniels KJ, Pujol C, Srikantha T, Soll DR. Candida albicans Forms a Specialized "Sexual" as Well as "Pathogenic" Biofilm. Eukaryot. Cell. 2013;12:1120–1131. doi: 10.1128/EC.00112-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Finkel JS, Mitchell AP. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:109–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soll DR. Why does Candida albicans switch? FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:973–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alby K, Bennett RJ. Interspecies pheromone signaling promotes biofilm formation and same-sex mating in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:2510–2515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017234108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]