Abstract

Hair cycling is modulated by factors both intrinsic and extrinsic to hair follicles. Cycling defects lead to conditions such as aging associated alopecia. Recently we demonstrated that mouse skin exhibits regenerative hair waves, reflecting a coordinated regenerative behavior in follicle populations. Here, we use this model to explore the regenerative behavior of aging mouse skin. Old mice (>18 months) tracked over several months show that with progressing age hair waves slow down, wave propagation becomes restricted, and hair cycle domains fragment into smaller domains. Transplanting aged donor mouse skin to a young host can restore donor cycling within a 3mm range of the interface, suggesting that changes are due to extra-cellular factors. Therefore, hair stem cells in aged skin can be re-activated. Molecular studies show that extra-follicular modulators Bmp2, Dkk1, and Sfrp4 increase in early anagen. Further, we identify follistatin as an extra-follicular modulator which is highly expressed in late telogen and early anagen. Indeed follistatin induces hair wave propagation and its level decreases in aging mice. We present an excitable medium model to simulate the cycling behavior in aging mice and illustrate how the inter-organ macro-environment can regulate the aging process by integrating both “activator” and “inhibitor” signals.

Keywords: hair cycling, hair follicle stem cell, alopecia, macro-environment, intra-dermal adipose tissue

Introduction

Aging is a physiological process associated with a progressive deterioration in the ability of tissues to repair and regenerate. As hair follicles (HFs) undergo repetitive cyclic regeneration under physiological conditions during an organism's life cycle (Chuong et al., 2012), they represent an excellent model in which to study changes in stem cell activity throughout the aging process. Single HF regenerative cycling can be divided into 4 consecutive phases: anagen (growth phase), catagen (regression phase), telogen (resting phase), and exogen (when hair filaments dislodge) (Paus and Foitzik, 2004). The HF stem cell activation process culminates with canonical WNT signaling induction (Huelsken et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2001; Lowry et al., 2005). Within the HF micro-environment (or niche), cyclic stem cell activation can be regulated by a competitive balance between activators and inhibitors within the bulge (Kandyba et al., 2013), or between the dermal papilla and epithelia (Botchkarev et al., 1999).

Thousands of HFs within a localized area can cycle independently, synchronously, or in a coordinated fashion. When we examined hair cycling behavior in a HF population, a collective, population-level regenerative behavior emerged. In mouse skin, this coordinated regeneration is manifest as a wave of hair growth; initiating at one point and traversing a skin domain or the whole skin.

The regenerative hair wave was initially observed in a classical study (Chase, 1954). We now non-invasively monitor regenerative hair waves over long periods of time by clipping pigmented mouse hairs and following skin pigmentation pattern changes over time (Plikus et al., 2008, 2009, 2011). We pursued these studies further by analyzing wave patterns and their molecular basis. Analysis of these wave patterns revealed that cyclic β-catenin signaling in the HF and cyclic BMP signaling in the intra-dermal adipose layer oscillate out of phase, thuse dividing telogen into two functional phases, refractory (R) and competent (C). Anagen is also divided into two phases, propagating (P) and autonomous (A) (Plikus et al., 2008). BMP and Sfrps are known inhibitors of the mouse hair cycle telogen to anagen transition. In rabbits, hair waves propagate in more complex fractal-like patterns, in part due to their compound follicle configuration. In transgenic K14-Wnt7a mice with elevated canonical WNT signaling levels, hair waves propagate faster than in controls. In humans, coordinated hair waves exist only during fetal development and adult hair can only be activated by intrinsic signals (Plikus et al., 2011).

Alopecia is one manifestation of aging in humans and mice. Alopecia may be caused by defects intrinsic to stem cells or by extrinsic environmental factors (Li et al., 2013). Recently, alopecic human scalp HFs were shown to maintain their stem cell compartment but the principle defect in hair regeneration is due, instead, to a deficiency of hair germ progenitors (Garza et al., 2011). Here, we found, that in aging mice, hair cycle domains become smaller and the telogen period becomes extended. At the molecular level, we found that the macro-environmental modulators Dkk1 and Sfrp4 (Wnt pathway inhibitors) are abnormally expressed during the propagating anagen phase of aging mice. In addition, we find that the BMP inhibitor, follistatin, works as a macro-environmental modulator.

In early studies, transplanting rat skin from different aged donors was used to evaluate the effect of local and systemic factors on hair regeneration (Ebling, 1976). Here our skin transplantation experiments suggest that hair regeneration of aging skin can be affected by extra-follicular macro-environmental modulators secreted by adjacent young skin. Finally, we simulate hair cycling behavior in the regeneration of aging mouse skin using an excitable medium hair cycling mathematical model (Murray et al., 2012).

Results

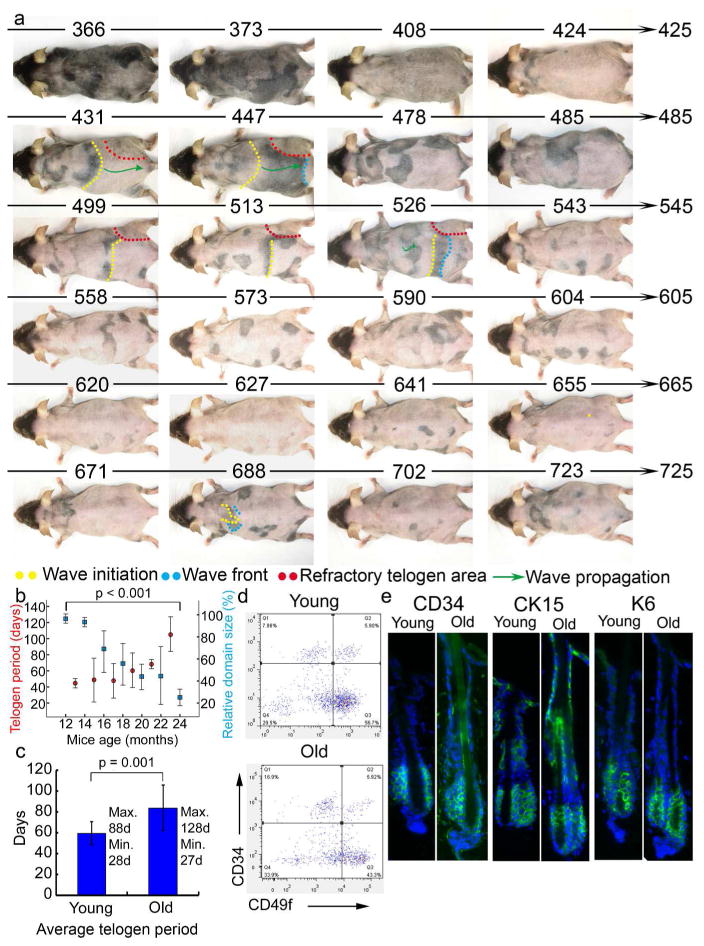

Aging mice exhibit altered regenerative hair wave patterns but HF stem cells appear to maintain normal molecular expression

To compare hair growth dynamics between young and old mice, we studied mice at varying ages (12, 18, 20, 22, 24 and 26 months) (Fig. 1a, S1, S2). We found that the hair cycle domains become fragmented, progressing from big domains at postnatal day 382 (P382) to smaller domains by days P478 - 550. Eventually, HFs enter extended telogen (day 613 to 655, Fig. 1a, 1b, S1, S2). Moreover, we identified a general trend in which the hair wave propagation distance and speed decreased with advancing age beyond 12 months. The propagation distance and speed decreased from 18mm and 2.6mm/day in one year old adult (day 431 to 454) to 10mm and 1.4mm/day in aged mice (day 513 to 526) and 5mm and 0.7mm/day in very old mice (day 681 to 688). In fact, almost no propagation occurs in very old mice. Smaller hair cycle domains in older mice have a longer average telogen period than that found in 6 month old young adult mice, as previously described (73.8 days vs. 59.6 days) (Plikus et al., 2008) (Fig. 1c, S3). While in young adult mice, 88 days was the longest telogen period observed, here we observed that the telogen period in some hair cycle domains on old mice can exceed 128 days (Fig. 1b, 1c). The elongated telogen period phenomenon is known as “telogen retention”.

Figure 1. Aging mice show altered regenerative hair wave patterns: longer telogen and smaller domains.

a. Twelve month old mouse was photographically documented for 358 days until it died. Mouse age (days) is indicated above each photograph. b. The telogen period (red dot) increases and the hair cycle domain (blue square) size decreases with advancing age. Error bar is shown. c. Average telogen period is longer in older compared to younger mice (n=5). d. Representative FACS scatterplots and summarized CD34+/CD49f + cell percentages are similar for young and old mouse epidermis. e. Immunostaining (green) of three exemplary hair follicle stem cell markers in 2 and 22 month old mouse dorsal skin sections. Few differences in cell number and expression levels are seen. DAPI staining (blue).

We think there are two possible defects that may lead to both telogen retention and small hair cycle domains (caused by shortening of propagating distance) in aging mice. 1) A defect in the stem cell compartment - HF is not able to respond to a signal. 2) A defect in the anagen activating signal – HF stem cells are normal. In order to evaluate whether the observed aging-induced phenomena are due to the depletion of stem cells, FACS analysis was performed using hair stem cell markers (N=3). We did not observe significant differences between young and old mice in the overall CD34+/CD49f+ populations (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, we immunostained with additional HF stem cell markers, K6, CD34, and Krt15, in the back skin of 22 month old mice. Our data show that the number of HF stem cells and the expression of the above markers are similarly expressed in aging mice (Fig. 1e) and can be activated to enter anagen (see below). With this background we focused on identifying extra-follicular changes in aging skin and their roles in prolonging telogen. While our results are consistent with the finding that aging associated human alopecia is due to a failure to activate hair stem cells (Garza et al., 2011), our work does not rule out that stem cells are altered during the aging process (Keyes et al., 2013).

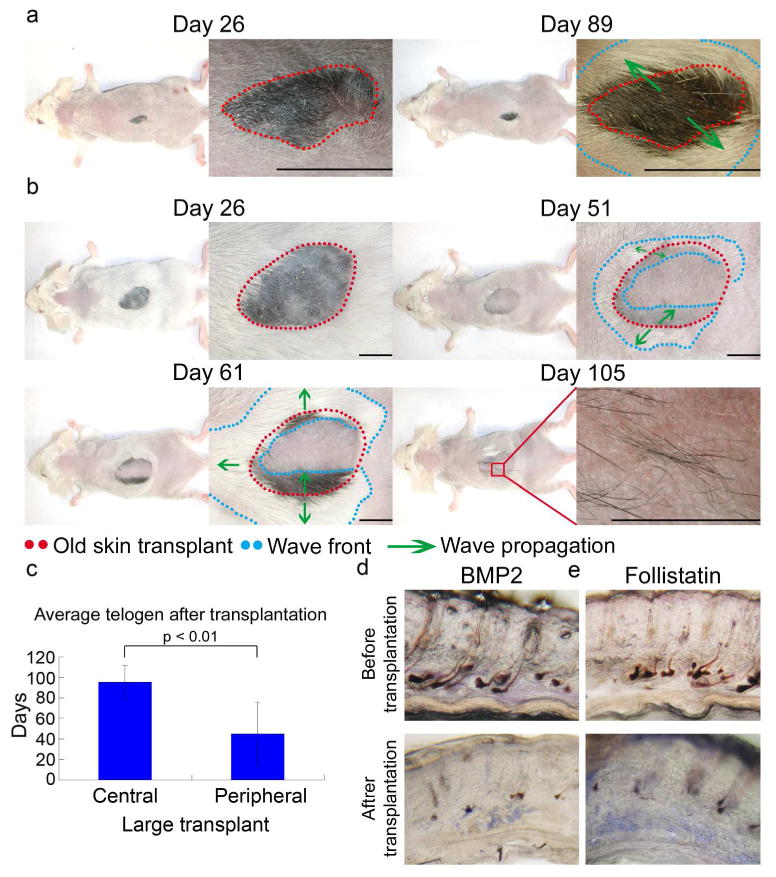

Transplantation experiments show telogen retention in old mice is partially rescued by a young macro-environment

To evaluate the hypothesis that aging of HFs is primarily mediated by environmental factors, we transplanted full-thickness skin that displayed telogen retention from 24 month old mice onto 3-6 month old young adult SCID mice. After a two month observation period, we found that, for a small donor skin (5×3 mm), hair growth was rescued and telogen retention was lost in the transplanted tissue. Twenty-six days after transplantation, the entire old skin graft enters the first regeneration cycle, initiated by transplantation-induced trauma. Surprisingly, the hair wave starting in the mature adult (day 89 post-transplantation) was initiated from the boundary of the transplant. It not only propagated across the entire old skin graft but also through the surrounding young skin (Fig. 2a, S4). However, transplanting a large skin graft (15×10 mm) only partially rescued hair growth and telogen retention in peripheral parts (3mm within the transplantation margin) of the transplant. The telogen phase in peripheral regions of the old transplant becomes shorter through interactions with the younger host (Fig. 2b, 2c, S5, S6). In contrast, the central part (3mm away from the transplantation margin) of the transplant did not respond to the young host and retained “telogen retention” status (Fig. 2c, S5, S6).

Figure 2. Young mouse skin macro-environment partially rescues hair cycling in aging skin.

a. Young SCID mouse dorsum rescued hair growth and telogen retention of small, old skin transplants. Hair wave propagated throughout the graft and surrounding younger host skin in the next cycle (day 89 post-transplantation). b. Telogen retention was partially rescued for large transplants. During the secondary cycle (days 51, 61), hair wave propagated ∼3mm inward from the explant border; not reaching the graft center. Later (day 105), hairs formed toward the graft center, did not propagate to surrounding areas. c. Telogen remains long in the central, large, old skin graft but becomes shorter in the periphery (n = 3). d, e, Grafting older skin to younger mice decreased Bmp2 and increased follistatin. Size bar: 5mm.

Trauma induced the entire large (15×10 mm), old skin graft to regenerate by 26 days in the first hair cycle after transplantation. However, in the second post-transplantation hair cycle, the hair wave only propagated a short distance from the transplant border and did not reach the center of the graft (day 51 and 61). Moreover, the center hair cycle domain was reduced in size and could not propagate to the surrounding area (day 105), retaining characteristics of the old donor tissue (Fig. 2b, S5). Together, these data reveal that the host skin could only affect a limited spatial region at the periphery of the transplanted older skin. Our data suggest that when the transplant is too large, hair cycling of the central region is not influenced by the host.

We evaluated molecular changes during aging and found that macro-environmental Bmp2 is increased and follistatin (Fst) is reduced in the skin of aging mice (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). When a small piece of old mouse skin was transplanted onto young SCID mice, we observed that Bmp2 was down-regulated and Fst expression level was elevated (Fig. 2d, 2e, S14b). Thus, our results imply that the transplantation experiment allows old and surrounding young skin to interact through molecular signaling. The young skin provided an environment favoring hair regeneration and restored this ability to the old skin. Transplanting 6 month old young skin onto 24-month-old mice prolongs the telogen period further confirming that the environment can regulate the hair regeneration process (Fig. S7).

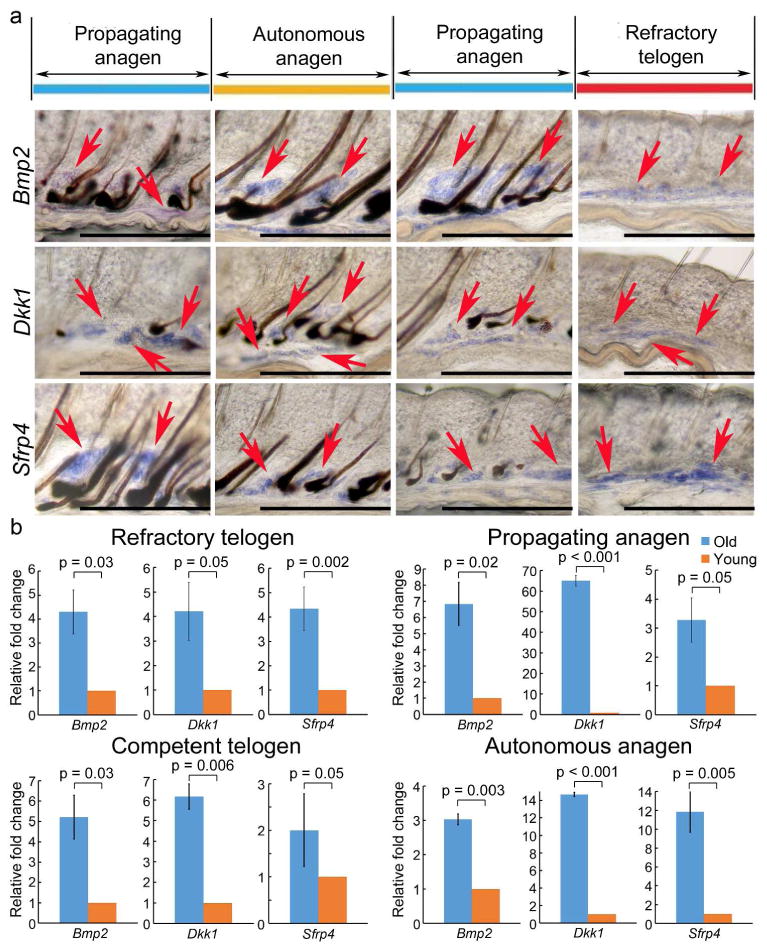

Figure 3. Macro-environment extra-follicular modulators, Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4, are up-regulated in old mice.

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) of dorsal skin stripes taken from 24 month old mice. Hair cycle stages are estimated based on propagating hair waves. a. Bmp2 and Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, including Dkk1 and Sfrp4, should have been negative in the propagating anagen in the normal adult (e.g., 6 month old) mice. But they are expressed during this stage in the 24 month old mice. b. Quantitative RT-PCR from intra-dermal adipose tissues revealed of the skin from 24 months old mice show an overall up-regulation of inhibitors in all hair cycling phases, comparing to 6 month old young mice.

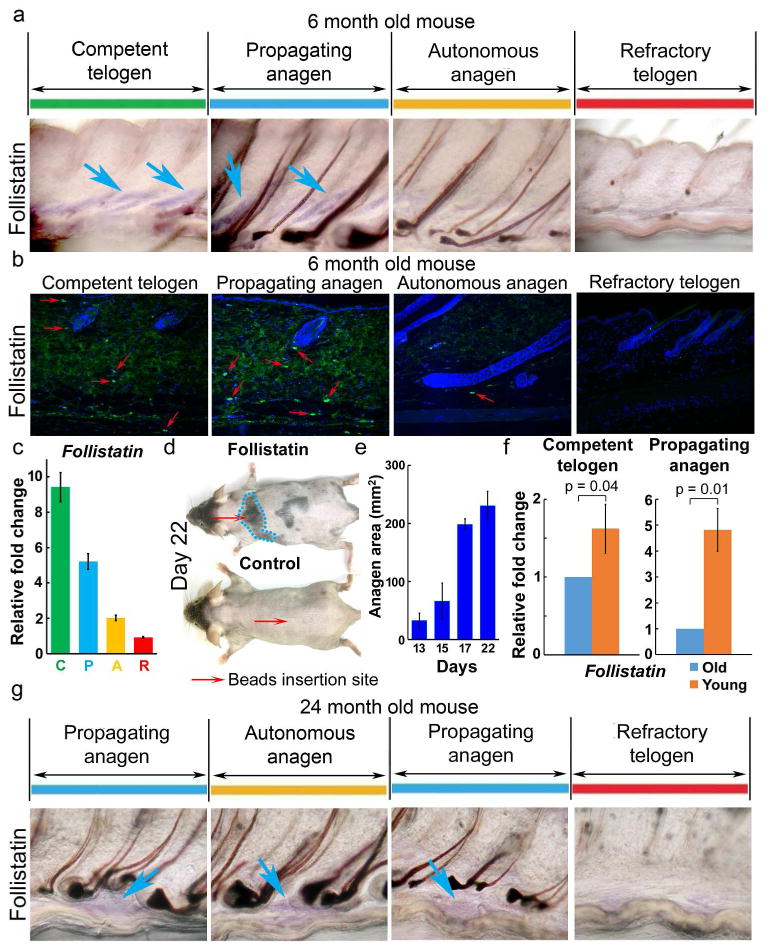

Figure 4. Extra-follicular follistatin promotes hair wave propagation in young mice, but levels decrease in older mice.

a-e. Follistatin in young adult (6 month) mouse skin. a, Follistatin WMISH shows expression in competent telogen (C) and propagating anagen (P), but not in refractory telogen (R) nor autonomous anagen (A). Confirmation by (b) immunostaining and (c) RT-PCR. Red arrows, follistatin positive cells. d, e. Follistatin soaked beads induce precocious anagen re-entry (day 13) which propagates to surrounding HFs (day 17), to a maximum area (∼ 250 mm2, day 22; n=3). Control BSA soaked beads show no effect. f. RT-PCR shows follistatin is decreased in C and P phases of old (24 months) mice. g. WMISH confirms decreased follistatin levels in 24 month old mouse P phase.

Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4 are up-regulated in 24 month old mice during the propagating anagen phase

Stem cell activation in the HF system is regulated by periodic Wnt/β-catenin activity (Huelsken et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2001; Lo Celso et al., 2004; Lowry et al., 2005). To determine whether the Wnt signaling pathway (intrinsic factors) is altered during aging, we evaluated Wnt ligand expression in 24 month old mice and found that Wnt5a, Wnt6 and β-catenin are activated in the hair germ and outer root sheath during propagating and autonomous anagen but not during refractory telogen. These Wnts are expressed in similar patterns as seen in 6 month old adult mice (Fig. S8, S9).

Our previous studies showed that telogen HFs in the refractory phase are prevented from entering anagen because high inhibitor levels (e.g. Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4), are present in the surrounding skin macro-environment (Plikus et al., 2011). Hence, the duration of telogen is dependent on inhibitor expression levels. By evaluating inhibitor expression patterns in 24 month old mice, we found that Bmp2 and Wnt antagonists, such as Dkk1 and Sfrp4, are expressed not only during autonomous anagen and refractory telogen phases, as is the case for 6 month old adult mice, but, surprisingly, these inhibitors are also present during propagating anagen (Fig. 3a, S10). To confirm this, intra-dermal adipose tissue was dissected and tested for gene expression using quantitative RT-PCR. Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4 are highly up-regulated in 24 month old mice during refractory telogen, propagating anagen, competent telogen and autonomous anagen phases (Fig. 3b).

Extra-follicular follistatin signaling promotes hair wave propagation

Competent telogen HFs are characterized by low inhibitor levels. It is thought that HFs can enter anagen when total activator levels, from within or outside of the follicle, reach a threshold level (Chen and Chuong, 2012; Kandyba et al., 2013). In addition to the above candidates, we screened for additional extra-follicular modulators and found that follistatin is expressed in propagating anagen and competent telogen, but not in refractory telogen in 6 month old adult mice (Fig. 4a, 4b, S11a). RT-PCR from intra-dermal adipose tissues further confirms that follistatin is highly expressed during propagating anagen and competent telogen phases (Fig. 4c, S11a, S12a). Double staining of follistatin and perilipin A demonstrated that adipocytes are responsible for follistatin secretion (Fig. S12b).

Interfollicular adipocyte precursor cells were recently found to secrete PDGFA and induce anagen re-entry (Festa et al., 2011). We found, using synchronized anagen induction experiments (Fig. S13), that PDGFA was not activated until the initiation of early anagen, 4 days after waxing (Fig. S14a). However, follistatin expression is increased 12 hours after waxing; much earlier than PDGFA (Fig. S14a). Together with the observation that follistatin is expressed cyclically in the interfollicular macro-environment and out-of-phase with BMP (Fig. S12a), these data imply that follistatin plays a role in hair wave propagation in early anagen.

To further evaluate the function of follistatin, mouse recombinant follistatin protein coated beads were inserted into the dorsal telogen skin of 6 month old adult mice. We found that 13 days after beads were inserted into competent telogen skin, HFs re-entered anagen. At 17 days, the regenerative wave propagated to the surrounding skin and reached the maximum propagating area (about 247.7 mm2) by 22 days (Fig. 4d, 4e, S15a). In the control study, albumin containing PBS-soaked beads showed no anagen re-entry even after 42 days (Fig. 4d, S15b). These data indicate that follistatin participates in facilitating anagen re-entry and promotes hair wave propagation.

Extra-follicular follistatin is down-regulated in 24 month old mice

We next analyzed the expression of follistatin in 24 month old mice and found, using whole mount in situ hybridization, that it is down-regulated during competent telogen and propagating anagen phases (Fig. 4g). RT-PCR from intra-dermal adipose tissues further substantiates this finding (Fig. 4f). We think the initiation and propagation of the regenerative hair wave is dependent upon a combination of different activator and inhibitor levels, originating both within follicles and in the extra-follicular macro-environment. Reduced follistatin expression in older mice raises the required threshold for combined activator levels needed for anagen initiation and wave propagation. Interestingly, this change is not irreversible; in the transplantation experiment, follistatin levels are raised through interactions with younger skin (Fig. 2e, S14b).

Integrating observations at the molecular, single follicle, and multi-follicle scales using a mathematical model of hair follicle growth

In this study, we examined the effects of aging on mouse hair cycling at three different scales and observed that 1) at the follicle population scale, propagating waves travel slower, 2) at the single follicle scale, telogen is extended, and 3) at the molecular scale, inhibitors are over-expressed and the activator, follistatin, is down-regulated. As it is technically difficult to show causality between these observations, we used mathematical modeling to investigate how observations made at these disparate scales might be related.

In a recent study, we proposed that the functional phases of the HF cycle (i.e. P, A, R, C) emerge from an excitable medium mathematical model containing HF growth activators and inhibitors (Plikus et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2012). Moreover, by coupling neighboring follicles, the model can naturally simulate the phenomena of wave propagation and stochastic excitation. Such a model is therefore ideally suited to placing the multi-scale observations made in this study in a single theoretical framework.

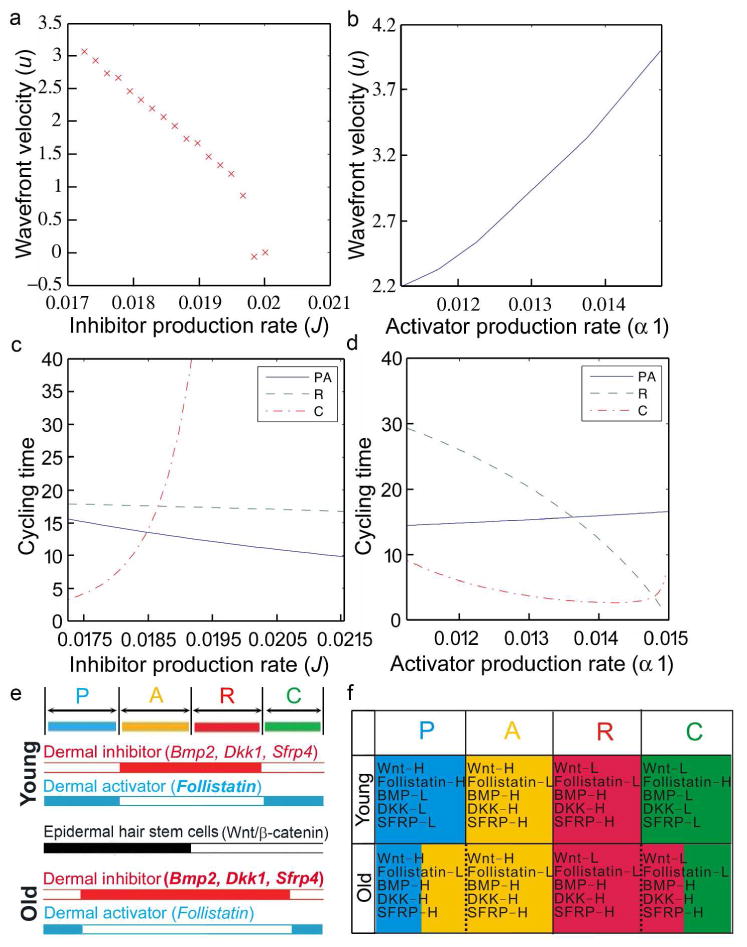

In Figure 5a and 5b, we demonstrate how in the excitable medium model, the speed of the propagating wave front decreases both as the inhibitor production rate increases and the activator production rate decreases. Hence, the model supports the hypothesis that the increased inhibitor and decreased activator activities observed in older mice would give rise to reduced wave speeds and, hence, smaller domain sizes.

Figure 5. Decreased wavefront velocity in aging mouse skin revealed by the excitable medium model.

a-d. Wavefront velocity decreases in an excitable medium description of the HF cycle. Plots of a. wavefront velocity, u, vs inhibitor production rate, J. b. wavefront velocity, u, vs activator production rate, α1. c. Cycling times vs inhibitor production rate, J. d. Cycling times vs activator activation rate α1.

Time spent by an individual follicle in propagating anagen (P), autonomous anagen (A), refractory telogen (R) and competent telogen (C).

e. Summary. Epidermal hair stem cell activation is regulated by intra-follicular and extra-follicular dermal activators / inhibitors. Dermal macro-environmental inhibitor levels increase in aging skin. f. Extra-follicular modulators in different hair cycle stages of young and old mouse skin. In old mice, decreased activators and increased inhibitors shorten the P phase and lengthen the R phase.

Moreover, the model predicts (Figs. 5c and 5d) that the increased inhibitor production and/or decreased activator production rates result in follicles that are more difficult to excite, and hence, have longer telogen phases. Therefore, by decreasing inhibitor production rates and increasing activation rates, the phenomena of smaller wave speeds and longer telogen durations can be rescued. A full description of the model is provided in the Supplement.

Discussion

Tissue aging is characterized by declining regenerative and homeostatic capacities. It has previously been hypothesized that the loss of stem cells plays a key role in the aging–dependent functional decline of tissue regeneration (Jones and Rando, 2011; Liu and Rando, 2011; Nishimura et al., 2005). However, the number of stem cells in a tissue does not necessarily decrease significantly with age (Booth and Potten, 2000; Brack and Rando, 2007; Giangreco et al., 2008). Deterioration of the regenerative ability can be due to a signaling defect intrinsic to stem cells, the niche, or both. Due to its cyclic regeneration (under physiological conditions) throughout life (Chuong et al., 2012), the HF system is an excellent model by which to understand aging in stem cells, the stem cell niche, and their interactions.

Here we found that HFs in old skin cycle more slowly and the wave stays in the resting phase for a much longer time than in younger skin. Moreover, the hair wave propagates at a reduced velocity and the hair domains fragment into smaller sized regions. There are five possible explanations for the effects of aging on hair regeneration: 1) hair inducing signals, such as Wnt pathway proteins may become down-regulated with aging, 2) propagating signals or activators secreted from neighboring anagen follicles or macro-environments are down-regulated, 3) old HFs cannot respond effectively to propagating signals or activators, 4) the stem cells are depleted, and 5) Wnt signal inhibitors, such as DKK and SFRP or BMP, are activated in old mice and inhibit anagen re-entry and hair wave propagation.

Our study reveals that HF stem cells appear to show normal expression of several molecular markers, suggesting that environmental factors play a more dominant role in controlling stem cell activation. It has been proposed that there are two kinds of bulge stem cells, basal (CD34+/CD49f+) and suprabasal (CD34+/CD49f-) (Blanpain et al., 2004). However, our FACS analysis showed that the number of suprabasal bulge stem cells was not consistent. So we just focused on the basal population of CD34+/CD49f+ expressing cells. We found that their expression levels are comparable in young and aging hair stem cells. To test if the aging related delay of the hair regeneration cycle was associated with extrinsic factors, we transplanted old skin onto young SCID mice. To our surprise the effects of aging could be reversed upon stimulation by factors from a young environment. This suggests that macro-environmental factors must play an important role in the alopecic phenotypes of aging mice.

Our molecular data showed that the extra-follicular macro-environment periodically expresses both activators (follistatin, etc) and inhibitors (Bmp2, Dkk1, Sfrp4, etc) and coordinates with intra-follicular Wnt/β-catenin signaling to regulate the hair regeneration cycle (Fig. 5e). In aging mice, the activator is down-regulated resulting in small hair cycle domains because hair wave propagation is not favored. Meanwhile, increased inhibitor expression in aging mice leads to telogen retention because anagen re-entry was inhibited (Fig. 5f).

A recent study demonstrated that nuclear factor of activated T-cell c1 (NFATc1) can orchestrate aging in HF stem cells. They report that parabiosis can't rescue aging HF regeneration and conclude that the systemic environment is not a major factor delaying hair stem cell activation (Keyes et al., 2013). However, our transplantation experiments illustrate hair stem cells can be regulated by signals emitted by the local but not systemic environment. Furthermore, we demonstrate that an aging environment can alter the regeneration response even though a stem cell is still capable of regeneration. This inference was further supported by their result which showed that dermal adipocyte BMP2 levels rise in aging mice and impacts hair stem cell activation (Keyes et al., 2013). The effect of aging on hair regeneration is likely to be mediated by signals both intrinsic and extrinsic to hair stem cells.

Several lines of evidence suggest follistatin promotes ectodermal organ growth. Follistatin knockout mice were shown to exhibit delayed HF development while the application of exogenous follistatin to wild type mouse skin culture stimulated HF development (Nakamura et al., 2003). Follistatin-like 1 (Fstl1) expression in hair bulge stem cells affects HF cycling (Yucel et al., 2013). The local application of follistatin to chick embryos induced ectopic feather buds in interbud regions (Patel et al., 1999), possibly by repressing lateral inhibition. Moreover, injecting the combination of follistatin and Wnt can stimulate hair regrowth in humans (Zimber et al., 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that follistatin is a crucial signal participating in hair wave propagation. Down-regulation of follistatin in older wild type mice further supplies a good explanation for why the hair wave propagation distance diminishes and hair cycle domains become smaller as mice age.

How does follistatin function? Follistatin is a well-known antagonist of activin. However, since both over-expression and knock-down of activin slowed hair morphogenesis (Nakamura et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2011), it is unlikely that follistatin's positive effect on the regeneration cycle was caused by antagonizing activin. In fact activin was shown to play a more important role during skin development than in adult murine skin (Bamberger et al., 2005). Activin may not be involved in the adult hair regeneration cycle because activin protein coated beads do not induce regeneration (our unpublished data). Follistatin also antagonizes Bmp2, 4, 7, and 11 activity (Fainsod et al., 1997; Iemura et al., 1998; Gamer et al., 1999). Here, follistatin is expressed periodically in the interfollicular dermis. The timing of its expression is out of phase with that of BMP2/4 during the hair cycle. Thus it may serve as an activator to facilitate anagen re-entry and wave propagation.

These results suggest that “telogen retention” in old mice is a consequence of the summed activities of all activators and inhibitors. The prolonged expression of these inhibitors could lead to “telogen retention” in old mice. The shorter competent telogen can result in fewer initiation sites of regenerative hair waves. The presence of inhibitors in propagating anagen can shorten the wave propagation distance, leading to smaller hair cycle domains. The longer refractory telogen can also contribute to the observed enlarged refractory telogen domains, which prevent hair wave propagation. Thus, through the integration of both activator and inhibitor signals, the extra-follicular macro-environment can regulate the regenerative cycling behavior, as is nicely illustrated in the mathematical simulation.

Our results show that, in aged mouse skin, inhibitors residing in the extra-niche macro-environment keep stem cells in a relatively dormant state. This is consistent with the human study showing that hair stem cells from the balding region of androgenic alopecia patients had a similar gene expression profile as those from non-balding regions (Garza et al., 2011). Opposing expression patterns of these macro-environment activators and inhibitors in the dermis can modulate the hair regeneration cycle. Aging can affect these macro-environments readily, but these changes can be rescued when the “old” macro-environment is surrounded by a “young” macro-environment. We envisage that the results presented in this study will aid the development of a strategy for the treatment of aging related degenerative disorders via improving the macro-environment.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Young (6-12 months), middle-aged (12-18 months), and old (18-24 months) C57BL/6 mice were used in this study. All procedures were performed on anaesthetized animals with protocols approved by the USC IACUC. Young SCID mice (3-6 months) served as hosts in skin grafting studies.

Hair cycle observation

Melanogenesis starts at anagen IIIa, becomes prominent in anagen IIIb, and continues until catagen (Muller-Rover et al., 2001). Therefore, HFs during most of anagen appear gray or black, while HFs in telogen have no pigment and the skin becomes pink. By shaving the hairs, one can observe the cycling stages of HFs in living mice (Chase, 1954; Plikus et al., 2008).

Protein administration experiment

Affi-gel blue gel beads (Biorad) were suspended in 5 μl protein solution (recombinant mouse follistatin 1 mg ml−1, R&D Systems). Approximately 100 beads were introduced to adult telogen mouse skin through a 30 g insulin syringe. Subsequent doses of 1.5 μl protein solution were microinjected to the bead implantation site daily for 10 days.

Histology, in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence

Tissues were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 to 6 μm. Whole mount samples were fixed and dehydrated according to the standard protocol. Tissues were then cut into thin strips.

For in situ hybridization, tissues were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled probes. Signals were detected using an anti-digoxigenin antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase. Sfrp4 (nt 183-755), Follistatin (nt 409-1075), and Fgf7 (nt 486-1088) probes were obtained as follows: Wnt5a (nt 74-1156) (Dr. Sharpe, King's College London), Dkk1 (nt 112-942) (Dr. Millar, University of Pennsylvania), Lef-1 (1176-1905) (Dr. Thesleff, University of Helsinki).

Immunofluorescence staining was performed with anti-follistatin (mouse, 1:50, Abcam) and anti-perilipin A (rabbit, 1:100, Abcam) antibodies followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa-488 and Alexa-568.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

RNA was prepared using TRI Reagent BD (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) following the manufacturer's recommendations. The protocol includes differential lysis of intra-dermal adipose tissues and isolates total RNA. RNA was quantified by quantitative RT-PCR, based on SYBR Green technology and StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene control and the primer sequences were listed in the supplementary table 1. StepOnePlus™Software v2.1 was used to quantify the gene fold change.

Flow Cytometry

Isolation of HFSCs and staining from young and old mice were done as follow. Subcutaneous fat was removed from skins with a scalpel, and skins were placed dermis side down on trypsin (Gibco) at 37 °C for 30 min. Scraping the skin to remove the epidermis and HFs from the dermis was performed to obtain single-cell suspensions. 70-mm and then 40-mm strainers were used to filter the cells. Cell suspensions were incubated with the appropriate antibodies for 30 min on ice. The following antibodies were used for FACS: CD49f (R&D, APC-conjugated) and CD34 (eBiosciences, FITC-conjugated). FACS analyses were performed using FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. The hair regeneration cycle is altered as mice age. A 12 month old mouse was photographically documented for 358 days until it died naturally. Mouse age (days) is indicated above each photograph. The hair wave propagation distance in 12 month old mice reduces with age from young (14 months, from day 431 to 454) to “middle aged” status (17 months, from day 513 to 526) to almost no propagation in old mice (24 months, day 681 to 688), which results in smaller hair cycle domains.

Figure S2. Hair regeneration cycle in 24-26 month old mice. The hair regeneration cycle of 24 month old mice was followed until the mice died naturally 57 days later. Most hair cycle domains remained in telogen. Even though some anagen initiation can occur, the regeneration cycle domains are all small (n=5).

Figure S3. Hair regeneration cycle in young mice. In young mice, the telogen period is short and the regeneration cycle domains are big.

Figure S4 “Telogen retention” in old mice is rescued when small skin grafts were transplanted onto a young macro-environment. When a small skin graft (5×3 mm) from an old mouse was transplanted onto young SCID skin, hair growth and telogen retention were rescued. The hair wave in the secondary cycle (day 89 post transplantation) propagated into the surrounding young skin as well as throughout the skin graft.

Figure S5. “Telogen retention” persisted in the central part of a large skin graft from an old mouse. When a large skin graft (15×10 mm) from an old mouse was transplanted to a young SCID mouse, the HFs from the graft regenerated completely during the first cycle (from day 26 post transplantation). However, this round of regeneration may be due to wound healing in response to engraftment surgery. In the secondary cycle (from day 51 post transplantation), hair growth and telogen retention were partially rescued in peripheral parts of the transplant, which showed a shortened telogen period as seen in young adult mice, while the central part of the transplant remained unchanged from that of the donor skin. We also found that the hair wave of the secondary cycle propagated only into the host tissue but not to the center of the donor tissue (day 51 and 61 post transplantation). Moreover, at later times (day 107 post transplantation), the small central hair cycle domain could not propagate to the surrounding area. This is similar to what was seen for the original donor mouse skin.

Figure S6. Only peripheral part can be rescued when large old skin was transplanted. Another example demonstrates that large old skin transplant can totally regenerated during the first cycle after transplantation (day 25 post transplantation). However, during the 2nd (day 69 post transplantation) and 3rd (day 127 post transplantation) regeneration cycle, only peripheral part of the transplants can enter anagen phase and central part of the transplant remains in “telogen retention” status.

Figure S7. Old environment inhibits hair regeneration of young skin. One small piece of young skin taken from 6-month-old mouse was transplanted onto the back of 24-month-old mouse. The regeneration response of the young skin was inhibited and the telogen period was prolonged. (red circle: the transplant area)

Figure S8. The expression pattern of Wnt signaling pathway members, Bambi, Sostdc1, and Fgf-7, in 6 month old adult C57BL/6 mice. In situ hybridization showed that Wnt family members were expressed as follows: Wnt3a, inner root sheath; Wnt5a, both inner and outer root sheath; Wnt6, mainly in outer root sheath; Lef-1, dermal papilla as well as both the inner and outer root sheath. Bambi is located in the dermal papilla and outer root sheath area; Sostdc1 and Fgf-7 are only expressed in the dermal papilla.

Figure S9. The expression pattern of the Wnt signaling pathway in 24 month old mice is not altered. Whole mount in situ hybridization of skin samples taken from a 24 months old mouse containing different phases of the hair regeneration cycle revealed that the Wnt signaling pathway, including Wnt5a, Wnt6, and β-catenin, are activated in the hair germ and outer root sheath during propagating and autonomous anagen phases but not during refractory telogen phase.

Figure S10. Dermal inhibitors Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4 are highly expressed in 24-month-old mice Whole mount in situ hybridization of skin samples taken from 24 month old mice shown as a skin strip (a) and magnification of follicles (b). Different phases of the hair regeneration cycle are shown in colored boxes. Bmp2 and Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, including Dkk1 and Sfrp4, were negative during the propagating anagen phase of young mice (Plikus et al., 2011). They are expressed in old mice here. c. d. No staining can be identified in all stages when sense probes of Bmp2, Dkk1, Sfrp4 were used on the skin samples taken from the same 24 month old mice. Panel b is also shown in Fig. 3a.

Figure S11. Hair wave propagator follistatin is down-regulated in 24 month old mice a. Whole mount in situ hybridization in 6 month old mouse shows that, outside of the follicle, follistatin is expressed in P and C phases but not R and A phases. Different phases of the hair regeneration cycle are shown in colored boxes. b. The expression of follistain is down-regulated in 24 month old mouse even during propagating phase. Panel a is also shown in Fig. 4a and panel b is also shown in Fig. 4g.

Figure S12. Periodic expression of cyclic follistatin is out of phase with the BMP cycle. a. Whole mount in situ hybridization of a skin strip from 6 month old mouse containing different stages of the hair cycle revealed that follistatin was up-regulated during propagating anagen and competent telogen but not during autonomous anagen and refractory telogen. This expression pattern is out of phase with the BMP cycle which is expressed only during autonomous anagen and refractory telogen but not during propagating anagen and competent telogen. b. Double staining of follistaitn and perilipin-A.

Figure S13. Histological morphology of the hair follicles after waxing. H&E staining of the skin sample taken from 6 month old young mice at different time points after hair waxing revealed that HFs starts to extend and anagen is initiated 4 days after waxing.

Figure S14. Expression of follistatin and PDGFA after synchronized waxing. a. After waxing-induced hair regeneration, macro-environmental follistatin is highly upregulated at 12 hours but PDGFA is not induced until 4 days, when anagen is initiated. b. Hairs that regenerate from the transplantation margin could propagate in both directions, to the old skin transplant and to the young host. Compared to the increased expression of follistatin in old skin transplants, the expression of BMP-2 is down-regulated. Panel b is also shown in Fig. 2d.

Figure S15. Follistatin can initiate anagen and induce hair wave propagation. a. Anagen occurs 13 days after insertion of follistatin soaked beads and propagated to surrounding skin at day 17, reaching its maximum area of about 250 mm2 at day 22. b. albumin containing PBS-soaked beads showed no anagen re-entry even after 42 days. (red arrow: beads insertion area). Panel a and b are also shown in Fig. 4d and 4e.

Table S1. Primer Pairs Used for Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Table 1.

A table of measurements used to parameterise the PARC phase structured model of a single follicle.

| Mouse model | TP | TA | TR | TC | Units | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Wild-type | 4 | 10 | 28 | 0-60 | d | [4] |

| KRT14-Wnt 7a | 14 | 0 | 12 | 0-15 | d | [5] |

| KRT14-Nog | 4 | 10 | 6 | 0-5 | d | [4] |

Table 2.

A table of parameter values used in the calculation of numerical solutions. L represents interfollicular distance and d days.

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| a | Natural decay rate | d−1 | 0.015 |

| b | Inhibition rate | d−1 | 0.015 |

| c | Activation rate | d−1 | 0.015 |

| d | Natural decay rate | d−1 | 0.015 |

| α1 | Production rate | d−1 | 0.014 |

| α2 | Production rate | d−1 | 0.02 |

| I | Background activator production rate | d−1 | 0.015 |

| J | Background inhibitor production rate | d−1 | 0.017 |

| ν0 | Activator threshold | Nondim | 0.00 |

| ν1 | Activator threshold | Nondim | 0.65 |

| ε | Time scale separation constant | Nondim | 0.0005 |

| Γ | Noise strength | d−1 | 1.2e−5 |

| DA | Diffusion coefficient | L2d−1 | 0.0004 |

| N | Lattice dimension | Nondim | 75 |

Acknowledgments

CMC, TXJ, RBW are supported by US grants from NIH NIAMS RO1-AR42177 and AR60306. CCC is supported by Taiwan NSC 100-2314-B-075-044, NSC 101-2314-B-075 -008 -MY3, Taipei Veterans General Hospital (Industry-Government-Academic Cooperation projects, grant R11004), and Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation. We wish to thank Dr. Han Nan Liu and Dr. Jaw-Ching Wu of Yang Ming University / Taipei Veterans General hospital for their support. We thank Dr. Ruth Baker and Dr. Philip Maini of Oxford University for help in developing the excitable media mathematical model. We thank Dr. Erin Weber for help in manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Bamberger C, Schärer A, Antsiferova M, et al. Activin controls skin morphogenesis and wound repair predominantly via stromal cells and in a concentration-dependent manner via keratinocytes. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:733–47. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, et al. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Roth W, et al. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:158–64. doi: 10.1038/11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, Potten CS. Gut instincts: thoughts on intestinal epithelial stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1493–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Rando TA. Intrinsic changes and extrinsic influences of myogenic stem cell function during aging. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:226–37. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-9000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase H. Growth of the hair. Physiol Rev. 1954;34:113–26. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1954.34.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Chuong CM. Multi-layered environmental regulation on the homeostasis of stem cells: the saga of hair growth and alopecia. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;66:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Randall VA, Widelitz RB, et al. Physiological regeneration of skin appendages. Physiology. 2012;27:61–72. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00028.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJ. Hair. J Invest Dermatol. 1976;67:98–105. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12512509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fainsod A, Deissler K, Yelin R, et al. The dorsalizing and neural inducing gene follistatin is an antagonist of BMP-4. Mech Dev. 1997;63:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa E, Fretz J, Berry R, et al. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell. 2011;146:761–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer L, Wolfman NM, Celeste AJ, et al. A novel BMP expressed in developing mouse limb, spinal cord, and tail bud is a potent mesoderm inducer in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 1999;208:222–32. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza LA, Yang CC, Zhao T, et al. Bald scalp in men with androgenetic alopecia retains hair follicle stem cells but lacks CD200-rich and CD34-positive hair follicle progenitor cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:613–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI44478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco A, Qin M, Pintar JE, et al. Epidermal stem cells are retained in vivo throughout skin aging. Aging Cell. 2008;7:250–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco V, Chen T, Rendl M, et al. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:155–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, et al. beta-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iemura S, Yamamoto TS, Takagi C, et al. Direct binding of follistatin to a complex of bone-morphogenetic protein and its receptor inhibits ventral and epidermal cell fates in early Xenopus embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9337–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Rando TA. Emerging models and paradigms for stem cell ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:506–12. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandyba E, Leung Y, Chen YB, et al. Competitive balance of intrabulge BMP/Wnt signaling reveals a robust gene network ruling stem cell homeostasis and cyclic activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1351–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121312110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes BE, Segal JP, Heller E, et al. Nfatc1 orchestrates aging in hair follicle stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4950–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang TX, Chuong CM. Many paths to alopecia via compromised regeneration of hair follicle stem cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1450–2. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Rando TA. Manifestations and mechanisms of stem cell aging. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:257–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso C, Prowse DM, Watt FM. Transient activation of beta-catenin signalling in adult mouse epidermis is sufficient to induce new hair follicles but continuous activation is required to maintain hair follicle tumours. Development. 2004;131:1787–99. doi: 10.1242/dev.01052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry WE, Blanpain C, Nowak JA, et al. Defining the impact of beta-catenin/Tcf transactivation on epithelial stem cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1596–611. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Plikus MV, Maini PK, et al. Modelling hair follicle growth dynamics as an excitable medium. PLoS Comp Bio. 2012;8:e1002804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Matzuk MM, Gerstmayer B, et al. Control of pelage hair follicle development and cycling by complex interactions between follistatin and activin. FASEB J. 2003;17:497–499. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0247fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura EK, Granter SR, Fisher DE. Mechanisms of hair graying: incomplete melanocyte stem cell maintenance in the niche. Science. 2005;307:720–724. doi: 10.1126/science.1099593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Foitzik K. In search of the “hair cycle clock”: a guided tour. Differentiation. 2004;72:489–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07209004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K, Makarenkova H, Jung HS. The role of long range, local and direct signalling molecules during chick feather bud development involving the BMPs, follistatin and the Eph receptor tyrosine kinase Eph-A4. Mech Dev. 1999;86:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus M, Chuong CM. Making waves with hairs. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:vii–ix. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Mayer JA, de la Cruz D, et al. Cyclic dermal BMP signaling regulates stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Nature. 2008;451:340–44. doi: 10.1038/nature06457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Widelitz RB, Maxson R, et al. Analyses of regenerative wave patterns in adult hair follicle populations reveal macro-environmental regulation of stem cell activity. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:857–68. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072564mp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Baker RE, Chen CC, et al. Self-organizing and stochastic behaviors during the regeneration of hair stem cells. Science. 2011;332:586–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1201647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Li X, Tang H, et al. Conditional activin receptor type 1B (Acvr1b) knockout mice reveal hair loss abnormality. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1067–76. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S, Andl T, Bagasra A, et al. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucel G, Altindag B, Gomez-Ospina N, et al. State-dependent signaling by Cav1.2 regulates hair follicle stem cell function. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1217–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.216556.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimber MP, Ziering C, Zeigler F, et al. Hair regrowth following a Wnt- and follistatin containing treatment: safety and efficacy in a first-in-man phase 1 clinical trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1308–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The hair regeneration cycle is altered as mice age. A 12 month old mouse was photographically documented for 358 days until it died naturally. Mouse age (days) is indicated above each photograph. The hair wave propagation distance in 12 month old mice reduces with age from young (14 months, from day 431 to 454) to “middle aged” status (17 months, from day 513 to 526) to almost no propagation in old mice (24 months, day 681 to 688), which results in smaller hair cycle domains.

Figure S2. Hair regeneration cycle in 24-26 month old mice. The hair regeneration cycle of 24 month old mice was followed until the mice died naturally 57 days later. Most hair cycle domains remained in telogen. Even though some anagen initiation can occur, the regeneration cycle domains are all small (n=5).

Figure S3. Hair regeneration cycle in young mice. In young mice, the telogen period is short and the regeneration cycle domains are big.

Figure S4 “Telogen retention” in old mice is rescued when small skin grafts were transplanted onto a young macro-environment. When a small skin graft (5×3 mm) from an old mouse was transplanted onto young SCID skin, hair growth and telogen retention were rescued. The hair wave in the secondary cycle (day 89 post transplantation) propagated into the surrounding young skin as well as throughout the skin graft.

Figure S5. “Telogen retention” persisted in the central part of a large skin graft from an old mouse. When a large skin graft (15×10 mm) from an old mouse was transplanted to a young SCID mouse, the HFs from the graft regenerated completely during the first cycle (from day 26 post transplantation). However, this round of regeneration may be due to wound healing in response to engraftment surgery. In the secondary cycle (from day 51 post transplantation), hair growth and telogen retention were partially rescued in peripheral parts of the transplant, which showed a shortened telogen period as seen in young adult mice, while the central part of the transplant remained unchanged from that of the donor skin. We also found that the hair wave of the secondary cycle propagated only into the host tissue but not to the center of the donor tissue (day 51 and 61 post transplantation). Moreover, at later times (day 107 post transplantation), the small central hair cycle domain could not propagate to the surrounding area. This is similar to what was seen for the original donor mouse skin.

Figure S6. Only peripheral part can be rescued when large old skin was transplanted. Another example demonstrates that large old skin transplant can totally regenerated during the first cycle after transplantation (day 25 post transplantation). However, during the 2nd (day 69 post transplantation) and 3rd (day 127 post transplantation) regeneration cycle, only peripheral part of the transplants can enter anagen phase and central part of the transplant remains in “telogen retention” status.

Figure S7. Old environment inhibits hair regeneration of young skin. One small piece of young skin taken from 6-month-old mouse was transplanted onto the back of 24-month-old mouse. The regeneration response of the young skin was inhibited and the telogen period was prolonged. (red circle: the transplant area)

Figure S8. The expression pattern of Wnt signaling pathway members, Bambi, Sostdc1, and Fgf-7, in 6 month old adult C57BL/6 mice. In situ hybridization showed that Wnt family members were expressed as follows: Wnt3a, inner root sheath; Wnt5a, both inner and outer root sheath; Wnt6, mainly in outer root sheath; Lef-1, dermal papilla as well as both the inner and outer root sheath. Bambi is located in the dermal papilla and outer root sheath area; Sostdc1 and Fgf-7 are only expressed in the dermal papilla.

Figure S9. The expression pattern of the Wnt signaling pathway in 24 month old mice is not altered. Whole mount in situ hybridization of skin samples taken from a 24 months old mouse containing different phases of the hair regeneration cycle revealed that the Wnt signaling pathway, including Wnt5a, Wnt6, and β-catenin, are activated in the hair germ and outer root sheath during propagating and autonomous anagen phases but not during refractory telogen phase.

Figure S10. Dermal inhibitors Bmp2, Dkk1 and Sfrp4 are highly expressed in 24-month-old mice Whole mount in situ hybridization of skin samples taken from 24 month old mice shown as a skin strip (a) and magnification of follicles (b). Different phases of the hair regeneration cycle are shown in colored boxes. Bmp2 and Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, including Dkk1 and Sfrp4, were negative during the propagating anagen phase of young mice (Plikus et al., 2011). They are expressed in old mice here. c. d. No staining can be identified in all stages when sense probes of Bmp2, Dkk1, Sfrp4 were used on the skin samples taken from the same 24 month old mice. Panel b is also shown in Fig. 3a.

Figure S11. Hair wave propagator follistatin is down-regulated in 24 month old mice a. Whole mount in situ hybridization in 6 month old mouse shows that, outside of the follicle, follistatin is expressed in P and C phases but not R and A phases. Different phases of the hair regeneration cycle are shown in colored boxes. b. The expression of follistain is down-regulated in 24 month old mouse even during propagating phase. Panel a is also shown in Fig. 4a and panel b is also shown in Fig. 4g.

Figure S12. Periodic expression of cyclic follistatin is out of phase with the BMP cycle. a. Whole mount in situ hybridization of a skin strip from 6 month old mouse containing different stages of the hair cycle revealed that follistatin was up-regulated during propagating anagen and competent telogen but not during autonomous anagen and refractory telogen. This expression pattern is out of phase with the BMP cycle which is expressed only during autonomous anagen and refractory telogen but not during propagating anagen and competent telogen. b. Double staining of follistaitn and perilipin-A.

Figure S13. Histological morphology of the hair follicles after waxing. H&E staining of the skin sample taken from 6 month old young mice at different time points after hair waxing revealed that HFs starts to extend and anagen is initiated 4 days after waxing.

Figure S14. Expression of follistatin and PDGFA after synchronized waxing. a. After waxing-induced hair regeneration, macro-environmental follistatin is highly upregulated at 12 hours but PDGFA is not induced until 4 days, when anagen is initiated. b. Hairs that regenerate from the transplantation margin could propagate in both directions, to the old skin transplant and to the young host. Compared to the increased expression of follistatin in old skin transplants, the expression of BMP-2 is down-regulated. Panel b is also shown in Fig. 2d.

Figure S15. Follistatin can initiate anagen and induce hair wave propagation. a. Anagen occurs 13 days after insertion of follistatin soaked beads and propagated to surrounding skin at day 17, reaching its maximum area of about 250 mm2 at day 22. b. albumin containing PBS-soaked beads showed no anagen re-entry even after 42 days. (red arrow: beads insertion area). Panel a and b are also shown in Fig. 4d and 4e.

Table S1. Primer Pairs Used for Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR