Abstract

Background and Purpose

Prior work aimed at improving our understanding of human cerebral autoregulation has explored individual physiologic mechanisms of autoregulation in isolation, but none has attempted to consolidate the individual roles of these mechanisms into a comprehensive model of the overall cerebral pressure–flow relation.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed this relation before and after pharmacologic blockade of alpha-adrenergic, muscarinic, and calcium channel-mediated mechanisms in 43 healthy volunteers to determine the relative contributions of the sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic controllers to cerebral autoregulation. Projection pursuit regression was used to assess the effect of pharmacologic blockade on the cerebral pressure–flow relation. Subsequently, analysis of covariance decomposition was used to determine the cumulative effect of these three mechanisms on cerebral autoregulation and whether they can fully explain it.

Results

Sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic mechanisms together accounted for 62% of the cerebral pressure–flow relation (p < 0.05), with significant and distinct contributions from each of the three effectors. ANCOVA decomposition demonstrated that myogenic effectors were the largest determinant of the cerebral pressure–flow relation but their effect was outside of the autoregulatory region where neurogenic control appeared prepotent.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that myogenic effects occur outside the active region of autoregulation, whereas neurogenic influences are largely responsible for cerebral blood flow control within it. However, our model of cerebral autoregulation left 38% of the cerebral pressure–flow relation unexplained, suggesting that there are other physiologic mechanisms that contribute to cerebral autoregulation.

Keywords: autonomic control, cerebral blood flow, stroke

Introduction

The ability of the cerebrovasculature to buffer against swings in blood pressure (i.e, cerebral autoregulation) ensures steady perfusion of neural tissue in the face of hemodynamic challenges. Thus, the integrity of the physiologic mechanisms underlying autoregulation is critical to neural health.1 Accumulating evidence demonstrates that cerebrovascular dysfunction may be behind the morbidity and mortality secondary to pathological conditions ranging from mild traumatic brain injury2 to vascular dementia3 and stroke.4,5 Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the physiologic mechanisms responsible for autoregulation could guide treatment strategies for improving clinical outcomes for conditions that impact a substantial portion of the adult population.

Our past work has demonstrated that cerebral autoregulation requires intact sympathetic,6 cholinergic,7 and myogenic mechanisms.8 However, these data have been considered in isolation, whereas a full understanding of autoregulation requires integrating our knowledge of these physiologic mechanisms. This would reveal the manner and degree to which each of these mechanisms shapes the relationship between arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow, and would identify gaps in current research o the physiologic underpinnings for this relation.

While data derived from animal models has contributed significantly to understanding the physiology of autoregulation,9-12 there are inherent differences in hemodynamic challenges faced by quadrupeds vs. bipeds and so animal data may not be fully reconcilable with that from humans. On the other hand, human research is complicated by the inability to expressly eliminate each potential autoregulatory mechanism iteratively or simultaneously, as blocking more than one controller for cerebral blood flow is potentially dangerous. Hence, distinguishing the unique role of different physiologic mechanisms cannot be achieved through experimental design alone. Alternatively, there are well established statistical techniques that can compensate for this limitation and assess the relative contributions of multiple systems to autoregulation.

The current work employs one of these statistical techniques to determine the relative contributions of several effectors via analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) decompostion.13 This approach can explore each role in an additive fashion when subjects have been randomly assigned to different, possibly unbalanced, treatment groups. While the studies used6-8 in this retrospective analysis were not explicitly designed with ANCOVA decomposition in mind, the minimal overlap in groups essentially fulfils the role of random assignment. Data from alpha-adrenergic,6 muscarinic,7 and calcium channel8 blockade were combined to elucidate the relative contributions of sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic mechanisms to the pressure–flow relation. We then sought to determine whether the cumulative effect of these contributions is sufficient to fully explain autoregulation in healthy individuals.

Methods

A total of 43 volunteers (21-40 years old; 17 females) gave written informed consent before participation. There was no significant difference in subject characteristics (age, sex, and BMI) between the three protocols (p>0.3 for all). Volunteers were healthy non-smokers free of cardiovascular or neurological diseases and not on prescription medications. All participants had abstained from caffeine for twelve hours, and from alcohol and exercise for 24 hours prior to the study. All protocols were approved by the IRB and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. All studies were conducted between ~8 am and ~12 pm.

Experimental Protocols

After inserting a 20-gauge catheter into an antecubital vein for drug infusion, volunteers were instrumented for electrocardiographic lead II (Dash 2000; General Electric), beat-by-beat photoplethysmographic arterial pressures (Finapres; Ohmeda), and oscillometric brachial pressures (DASH 2000; General Electric) as a calibration for the photoplethysmographic measures. A transcranial Doppler ultrasonograph (2 MHz probe; DWL MultiDop T2) was used to measure cerebral blood flow velocity at the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery at a depth of 50-65 mm. Prior work suggest that the diameter of the middle cerebral artery remains relatively constant despite changes in blood pressure induced by lower body negative pressure.14 Thus, flow velocity was used as a surrogate for flow. Expired CO2 was continuously monitored by an infrared CO2 analyzer (Vacuumed) connected to a nasal cannula. All signals were digitized at 1 kHz (PowerLab, ADInstruments).

Data was collected during five minutes of supine rest followed by ten minutes of oscillatory lower body negative pressure (OLBNP) at a moderate level (−30 to −40 mmHg) at 0.03 Hz (i.e., ~30 seconds) oscillations. This level of OLBNP results in pressure oscillations comparable to those that occur within a physiologic range15 and reliably engage cerebrovascular regulatory mechanisms.16,17 The same protocol was repeated after pharmacologic blockade.

Pharmacologic blockades

Data was collected at baseline (n=48; twice in 5 subjects to account for within-subject variability), and after intravenous phentolamine (0.14 μg/kg bolus followed by 0.014 μg/kg/min infusion; sympathetic blockade, n=11), glycopyrrolate (stepwise injections of 0.2 mg over 20B30 minutes to reach a stable mean heart rate >100 beats min−1; cholinergic blockade, n=9), and nicardipine (3 mg bolus infusion over 8 - 10 minutes; myogenic blockade, n=16). At these doses, phentolamine blocks alpha-adrenergic effects on the vasculature,18 glycopyrrolate blocks muscarinic receptors present on the endothelium of the pial arteries19 without central cholinergic impairment, and nicardipine blocks calcium channels on the vascular smooth muscle.20 Seven volunteers did not receive any infusions, and so, only their baseline data is included in subsequent analyses.

Data Analysis

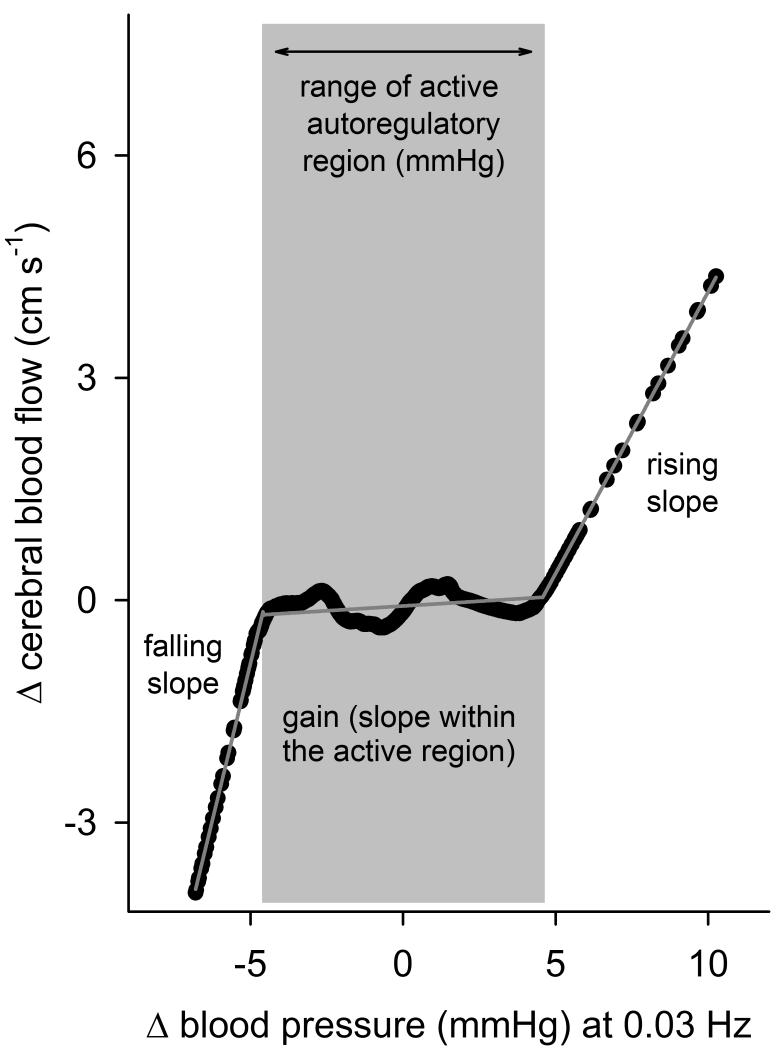

While linear methods are not sufficient to quantify the pressure–flow relation when autoregulation is effective (due to the nonlinear nature of this relation),17, 21 the complexity of most nonlinear approaches precludes simple physiologic interpretation of the observed relationships. To overcome these limitations, we employed projection pursuit regression (PPR; see Supplementary Material).17, 22, 23 Prior work has shown that PPR consistently reveals the dominant nonlinearity in the pressure–flow relation.17 Subsequent parametrization allows identification of points where the relation changes from seemingly more passive regions (i.e., higher slopes) to more active regions (i.e., slopes approaching zero) of autoregulation. The slope of the pressure–flow relation within each region provides a measure of the effectiveness of autoregulation within that region (lower slopes indicate more effective counter-regulation of pressure fluctuations). Therefore, PPR allowed us to define the characteristic nonlinear pressure–flow relation via five markers (falling slope, rising slope, lower and upper pressure limits of the active region, and autoregulatory slope (or Again@); Figure 1) in a way that permits straightforward physiological interpretation of any alteration in this relation under each condition (baseline vs. different blockades).

Figure 1.

Characteristic pressure–flow relation at 0.03 Hz in a representative subject. Black points show the relation revealed by PPR, and grey piecewise linear lines show the result of parametrization.

We used Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) decomposition13 to determine the relative contribution of sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic mechanisms to autoregulation. We asked whether there is a differential change in the characteristic nonlinear pressure–flow relation after blockade of each mechanism. The relation after each blockade would be reflective of the other two (unblocked) mechanisms (in addition to any other mechanism that is unaccounted for). This is analogous to a multiple regression wherein the pressure–flow relations at baseline is predicted from data pooled from (1) cholinergic and myogenic blockades (reflective of sympathetic effect), (2) sympathetic and myogenic blockades (cholinergic effect), and (3) sympathetic and cholinergic blockades (myogenic effect). ANCOVA refines estimates of individual variations in the pressure–flow relation at baseline and adjusts the treatment effects for any differences between the blockade groups that may have existed before the treatments. ANCOVA is routinely used with experimental designs, such as ours, wherein variables of interest are measured both before and after subjects are randomly assigned to different treatment groups (sympathetic, cholinergic, or myogenic blockade in this case). ANCOVA has the advantage that the relative contributions of each mechanism to the overall pressure–flow relation can be teased apart by comparing the residuals of the overall model to those when each treatment group is used alone. This comparison is achieved by decomposing the overall sum of squared errors to that of each treatment group. We relied on Type-III adjusted sum of squares when estimating ANCOVA decomposition to ensure that neither the unbalanced nature of our data, nor any possible dependencies between data sets, biased our estimation.24 The theoretical foundations an implementation details of ANCOVA decomposition are extensively described elsewhere13, 25 (see also Supplementary Materials).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Matlab (version 7.10; Mathworks, Natick, MA) and in R-Language. Normal distribution was confirmed via Q-Q plots, and Box-Cox transformation was applied when necessary. For ease of interpretation, all values presented in the text and tables are in standard units. Comparisons of all variables were made via one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with treatment (before and after blockade) as independent factors, unless indicated otherwise. Conformity of the data to statistical assumptions that underlie ANCOVA were verified via standard statistical tests, and ANCOVA was implemented via BioConductor libraries for R.25

Results

A one-way ANOVA by blockade (Table) showed a significant effect of blockade type on R-R Interval (all blockades p<0.05) and an effect of only sympathetic blockade on expired CO2. Sympathetic and cholinergic blockade had a tendency (p=0.09 and p=0.10 respectively) to cause a physiologically minor increase in blood pressure (3.2 mmHg for both). Calcium channel blockade had a tendency to reduce cerebral blood flow (p=0.06) by roughly 12%.

Table.

| Blockade |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=43) |

Sympathetic (n=11) |

Myogenic (n=16) |

Cholinergic (n=9) |

|

| Sex (male/female) |

26/17 | 7/4 | 9/7 | 5/4 |

| R-R Interval (ms) |

1036±21 | 828±36* | 935±30* | 643±39* |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) |

86.3±1.9 | 89.5±2.5 | 88.2±2.3 | 89.5±2.6 |

| Cerebral Blood Flow (cm s−1) |

61.4±2.8 | 70.1±6.2 | 54±4.1 | 60.8±2.6 |

| End Tidal CO2 (mmHg) |

35.3±0.9 | 31.7±1.5* | 34.6±1.3 | 35.9±1.3 |

p<0.05 vs. Baseline

On an individual level, PPR fit the data very well, explaining a majority of the relationship between pressure and cerebral blood flow (R2=0.60+0.02; >0.50 in 70% of all data sets). Parameterization of each subject’s pressure–flow relation provided the gain and range of the more active region of autoregulation as well as the slope of the relation outside of this region (Figure 1). There was no effect of blockades on the R2 of the pressure–flow relation (repeated measures ANOVA, p=0.86).

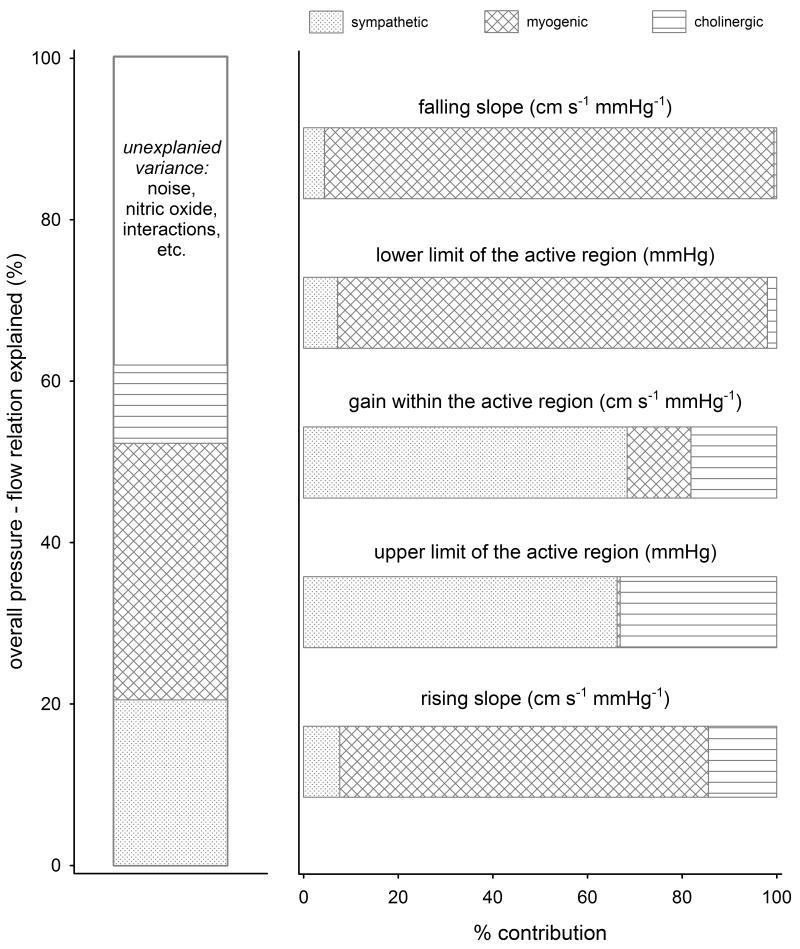

Overall, sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic mechanisms together accounted for 62% of the pressure–flow relation (p<0.05) (Figure 2), with significant contributions from each of the three effectors (partial R2 = 0.20 for sympathetic, 0.11 for cholinergic, and 0.31 for myogenic effectors). ANCOVA decomposition demonstrated that (1) the lower limit of the active region of autoregulation can be attributed primarily to myogenic effectors, while its upper limit depends exclusively on neurogenic mechanisms, (2) effectiveness of autoregulation (i.e., the gain) within the active region primarily depends on sympathetic mechanisms, with some contribution from myogenic and cholinergic effectors, and (3) the slope of the pressure–flow relation outside this region is mostly determined by myogenic effectors.

Figure 2.

Contributions of neurogenic and myogenic mechanisms to cerebral pressure–flow relation. The first panel shows their cumulative contributions (%) to overall relation. The second panel shows the relative contribution of each mechanisms to different parameters of autoregulation.

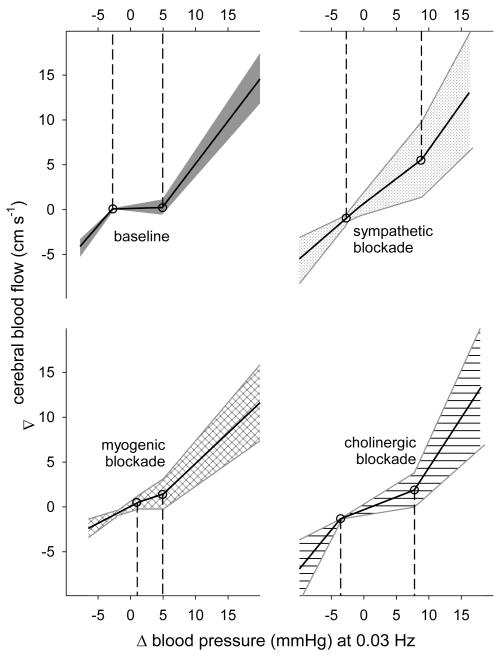

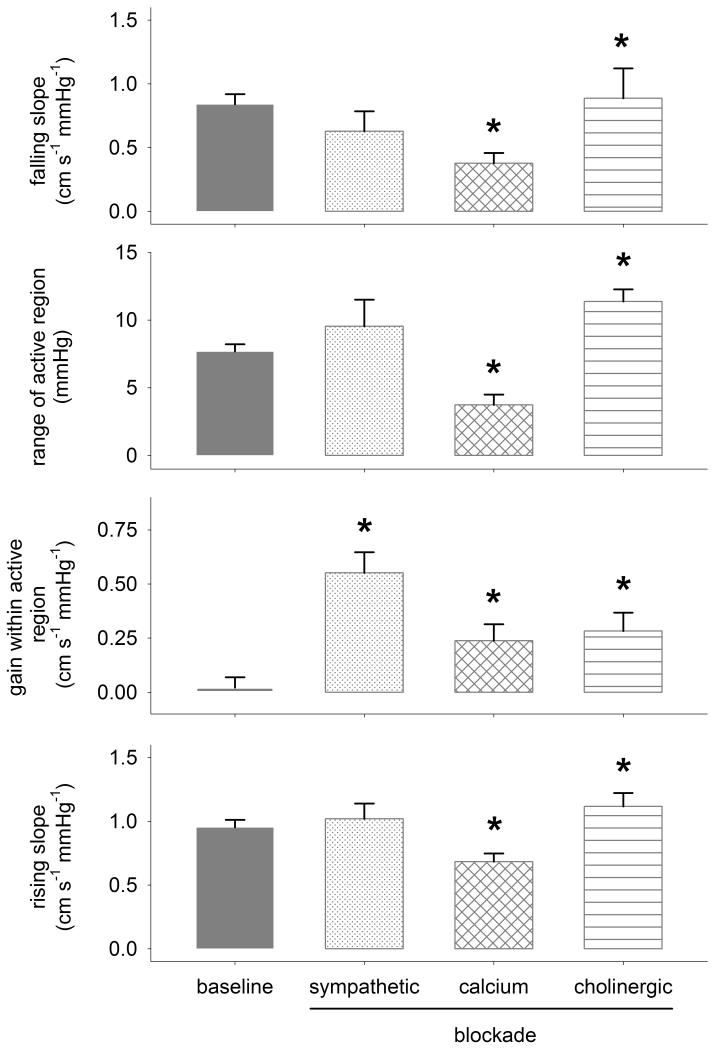

Sympathetic blockade markedly linearized the autoregulatory response by increasing gain within the active region (from 0.02+0.05 (SE) to 0.55+0.09 cm s −1 mmHg−1; p<0.05; Figures 3 and 4). Cholinergic blockade primarily resulted in an overall linearization of autoregulation resulting in an increased range (from 7.7+0.5 to 11.4+0.9 mmHg; p<0.05) and gain (to 0.28+0.08 cm s −1 mmHg−1; p<0.05) within the active region. Both sympathetic and cholinergic blockades tended to increase the slope of the relation between pressure and flow above the active region (i.e., increased the rising slope), though this effect reached significance only in case of cholinergic blockade. Myogenic blockade markedly reduced the pressure range of the active region (to 3.7+0.7 mmHg; p<0.05) primarily by increasing the lower limit of this range, and reduced the pressure-flow relation above and below the active region (i.e., reduced the rising and falling slopes). Both cholinergic and myogenic blockades also increased the gain within the active region of autoregulation, but to a lesser extent compared to sympathetic blockade.

Figure 3.

Characteristic pressure–flow relation at baseline and after blockade of each mechanisms. Solid lines show the mean and patterned regions show 95% C.I..

Figure 4.

Average (+SE) change in parameters of cerebral autoregulation at baseline and after each blockade. *p<0.05 vs. baseline.

Discussion

This study took a comprehensive look at multiple physiologic mechanisms responsible for cerebral autoregulation in humans. Our results suggest that while vascular myogenic control may be the largest determinant of the cerebral pressure-flow relation, those effects occur outside the more active region of autoregulation whereas neurogenic influences are largely responsible for cerebral blood flow control within it. Thus, while several studies have looked at whether or not individual pharmacologic blockades abolish cerebral autoregulation, this work directly addresses how the sympathetic, cholinergic, and myogenic systems work in concert to shape the pressure–flow relation in healthy humans.

Consistent with conventional wisdom, myogenic responses were the largest contributor to the pressure–flow relation. Myogenic effects appeared to be concentrated in the slope of the cerebrovascular response to both rising and falling pressures as well as being the primary determinant of the lower pressure limit of the active region of autoregulation. The sympathetic system represented the second largest contributor, via its effect on the gain and the upper pressure limit of the active region of autoregulation. The cholinergic system contributed in a relatively small but significant fashion, towards the upper end of the active region (i.e., gain and upper limit, and the rising slope). Hence, autonomic control of the cerebral vasculature is concentrated within the active region of autoregulation, with sympathetic and cholinergic reflexes accounting for 86% its gain and 99% of its upper limit. These results are broadly compatible with our previously published transfer function analysis that showed large effects of sympathetic blockade6 and smaller, but qualitatively similar effects of cholinergic blockade.7 Current results provide further evidence for active autonomic control of the cerebral vasculature, and suggest that it may in fact be the most important factor in homoeostatic control of brain blood flow. This role for neurogenic mechanisms fits with their known effects; relatively constant blood flow in response to changes in pressure requires active changes in artery diameter, and sympathetic and cholinergic mechanisms are responsible for vasoconstriction and vasodilation. Thus, their involvement in determining the range and gain within the active region of autoregulation is easy to reconcile with our current understanding of their distinct but complementary effects.

Our recent work has shown that calcium channel blockade also has an effect on the pressure–flow relation.8 The current study extends this finding, and reveals its contribution to this relation relative to that of neurogenic mechanisms. The myogenic response appears to be the main determinant of the lower limit of the active region of autoregulation, and of the slope of the pressure–flow relationship outside this region. This is consistent with the concept of vascular myogenic pathways primarily responding to rapid changes in perfusion pressure and flow.26 Nonetheless, while the effect of myogenic mechanisms was largely outside of the active region, these seemingly passive regions are likely the most important regions in responding to changes in perfusion pressure that would otherwise lead to ischemia or hemorrhage.

Furthermore, the myogenic role in these regions suggests that the “tails” of the pressure-flow relation are not as passive as generally conceived.

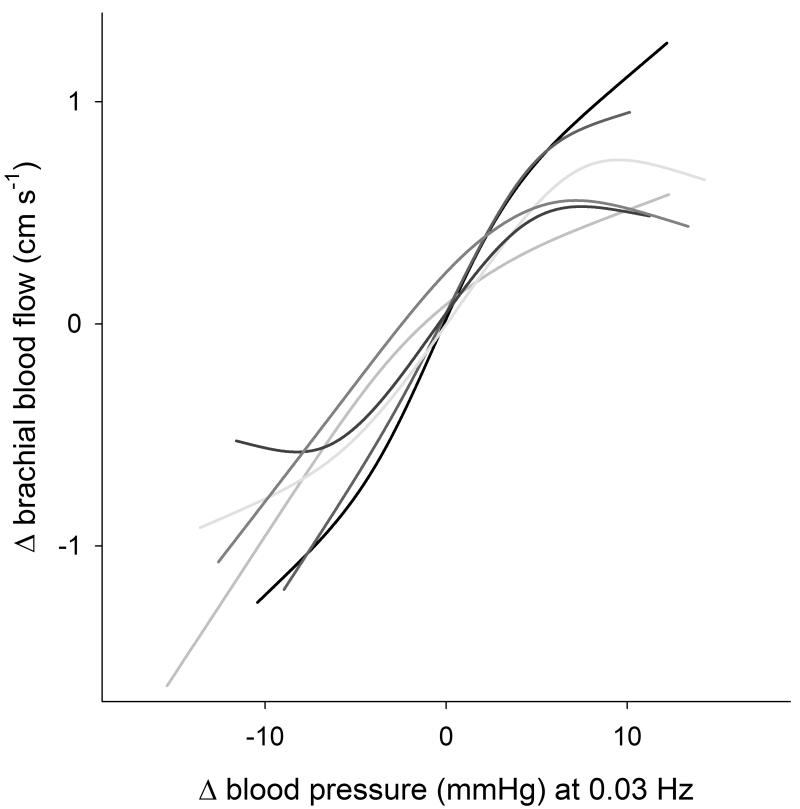

It should be noted that 38% of the pressure–flow relation at baseline remained unexplained after accounting for neurogenic and myogenic effectors, suggesting that there may be other physiologic mechanisms that contribute to cerebral autoregulation. One obvious possibility is that mechanical properties of vasculature can explain the remaining nonlinearity in the characteristic pressure–flow relation. However, data from animals show that denervated middle cerebral artery devoid of myogenic tone responds passively to increasing pressure, though the amount of smooth muscle activation increases somewhat at higher pressures.27 These data suggest that in the absence of physiologic effectors, blood flow should linearly track pressure, perhaps saturating at higher pressures. To verify that this is also the case in human arteries, we explored the relation between arterial pressure and brachial artery fluctuations after alpha-adrenergic blockade in six volunteers during an identical protocol.6 The responses of skeletal muscle resistance arteries to changes in arterial pressure are primarily under sympathetic control,28 and thus, the pressure–flow relation after alpha-adrenergic blockade would mostly reflect intrinsic vessel properties. The brachial pressure–flow relationship after blockade was mostly linear (though some threshold and saturation effects were apparent; Figure 5). Therefore, intrinsic resistance artery properties cannot explain the remaining nonlinearity in the characteristic pressure–flow relation after neurogenic and myogenic blockades.

Figure 5.

The relation between arterial pressure and brachial artery fluctuations after alpha-adrenergic blockade in six volunteers.

Another likely candidate is endothelial nitric oxide (NO). However, studies exploring the possible role of NO in cerebrovascular control have provided inconclusive findings. For example, intravenous infusion of the NO-donor sodium nitroprusside does not impact cerebral autoregulation in response to pressure changes,29 and blockade of NO-mediated pathways has not clarified the importance of this possible regulatory mechanism. Indeed, while NO synthase blockade does not change the relation between spontaneous pressure and flow fluctuations,30 it does blunt the cerebral blood flow responses to ischemic thigh cuff release.31 However it is possible that, much like calcium channel blockade,8 changes in the pressure–flow relation after L-NMMA are not reflected in linear approaches to cerebral autoregulation (e.g., transfer function gain). Thus, the role of NO in cerebral autoregulation in humans remains uncertain, and further investigation is warranted.

A third potential factor that might account for the remaining pressure–flow relation after neurogenic and myogenic blockade is multiplicative, or second-order, interactions between these effectors. Our assumption that the relation after each blockade would be reflective of the other two (unblocked) effectors is a reasonable one, but we cannot account for the fact that blockade might augment (or dampen) the unblocked systems. For example, the cholinergic system might play a permissive role to nitrergic flow regulation rather than acting as a direct mediator of the vasomotor response. Nevertheless, while the exact nature of interactions between the physiologic systems we examined cannot be determined without multiple simultaneous (and possibly dangerous) pharmacologic blockades, our work does establish their individual importance in cerebral autoregulation. Future work should attempt to tease apart possible interactions between the mechanisms of cerebral autoregulation.

A final consideration is that while we used pharmacologic doses reported in the literature to effect complete blockade,18-20 it is nevertheless possible that we did not achieve it in every subject. However, if this is the case, our results suggest that we may have underestimated the ability of the sympathetic, myogenic, and cholinergic systems to explain cerebral autoregulation. This possibility should be noted in case future work is unable to establish an important role for nitric oxide or other mechanisms.

Limitations

While PPR explained a majority of the pressure–flow relation at the individual level, it did not account for the variation in this relation fully. Nevertheless, the purpose of our approach is not to predict cerebral blood flow to its fullest extent but rather to accurately characterize the nature of the pressure–flow relation in a physiologically meaningful way. Another consideration is that the cerebral pressure–flow relation is frequency dependent.16, 17, 21 We examined the relation between fluctuations only at 0.03 Hz because of technical limitations on how slowly OLBNP can cause pressure to fluctuate and because autoregulation is active at this frequency.16, 17 Nonetheless, it is possible that the relative contribution of these physiologic systems may be frequency dependent as well. While frequencies faster than 0.07 Hz are of little interest because they are not counter-regulated against,16 oscillations slower than 0.03 Hz could be important to examine. An additional limitation to this study is that while 48 data sets were analyzed, the number of subjects in each blockade group ranged from 9 to 16. It is possible that with more subjects the marginal p-values (p<0.10) of some of the minor hemodynamic effects of blockade would have achieved significance, but such a change would not alter the interpretation of our main findings. Also note that while we use the term “neurogenic” when referring to the effect of blockade of alpha-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors on the vascular endothelium, it is also possible that the blockade of circulating neuroendocrine factors is playing some role in cerebral autoregulation.

Summary

Our findings suggest that neurogenic control of the cerebrovasculature is largely responsible for responding to pressure changes that occur within the active region of autoregulation, whereas the effects of vascular myogenic control lie mostly outside this region. This suggests that neurogenic control may be responsible for homoeostatic maintenance of cerebral blood flow, whereas myogenic control may be neuroprotective against ischemia and hemorrhage from rapid swings in pressure. However our model of cerebral autoregulation left 38% of the cerebral pressure–flow relation unexplained, suggesting a role for other mechanisms, such as endothelial NO release, in cerebral autoregulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None.

Sources of Funding: NIH grant HL093113.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Purkayastha S, Fadar O, Mehregan A, Salat DH, Moscufo N, Meier DS, et al. [Accessed December 20, 2013];Impaired cerebrovascular hemodynamics are associated with cerebral white matter damage. [published online ahead of print October 16, 2013] J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.180. http://www.nature.com/jcbfm/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/jcbfm2013180a.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Junger EC, Newell DW, Grant GA, Avellino AM, Ghatan S, Douville CM, et al. Cerebral autoregulation following minor head injury. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:425–32. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The LADIS Study Group 2001-2011: a decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) Study: what have we learned about white matter changes and small-vessel disease? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:577–88. doi: 10.1159/000334498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaeger M, Soehle M, Schuhmann MU, Meixensberger J. Clinical Significance of Impaired Cerebrovascular Autoregulation After Severe Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:2097–2101. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons LA, McCallum J, Friedlander Y, Simons J. Risk factors for ischemic stroke: Dubbo Study of the elderly. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1998;29:1341–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.7.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamner JW, Tan CO, Lee K, Cohen MA, Taylor JA. Sympathetic control of the cerebral vasculature in humans. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2010;41:102–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamner JW, Tan CO, Tzeng YC, Taylor JA. Cholinergic control of the cerebral vasculature in humans. The Journal of physiology. 2012;590:6343–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.245100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan CO, Hamner JW, Taylor JA. The role of myogenic mechanisms in human cerebrovascular regulation. J Physiol. 2013;591:5095–105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagawa K, Guyton AC. Pressure-flow relationships in isolated canine cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol. 1961;200:711–4. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.200.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolb B, Rotella DL, Stauss HM. Frequency response characteristics of cerebral blood flow autoregulation in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H432–H438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00794.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyton AC, Sagawa K. Compensations of cardiac output and other circulatory functions in areflex dogs with large A-V fistulas. Am J Physiol. 1961;200:1157–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.200.6.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Alecy LG, Rose CJ. Parasympathetic cholinergic control of cerebral blood flow in dogs. Circ Res. 1977;41:324–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olejnik S, Keselman H. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) In: Kattan M, editor. Encyclopedia of medical decision making. SAGE Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serrador JM, Picot PA, Rutt BK, Shoemaker JK, Bondar RL. MRI measures of middle cerebral artery diameter in conscious humans during simulated orthostasis. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2000;31:1672–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayanan K, Collins JJ, Hamner J, Mukai S, Lipsitz LA. Predicting cerebral blood flow response to orthostatic stress from resting dynamics: effects of healthy aging. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R716–R722. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamner JW, Cohen MA, Mukai S, Lipsitz LA, Taylor JA. Spectral indices of human cerebral blood flow control: responses to augmented blood pressure oscillations. J Physiol. 2004;559:965–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan CO. Defining the Characteristic Relationship between Arterial Pressure and Cerebral Flow. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1194–200. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00783.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halliwill JR, Minson CT, Joyner MJ. Effect of systemic nitric oxide synthase inhibition on postexercise hypotension in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1830–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elhusseiny A, Cohen Z, Olivier A, Stanimirovic DB, Hamel E. Functional acetylcholine muscarinic receptor subtypes in human brain microcirculation: identification and cellular localization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:794–802. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung DG, Gasster JL, Neutel JM, Weber MA. Acute pharmacokinetic and hemodynamic effects of intravenous bolus dosing of nicardipine. Am Heart J. 1990;119:438–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Giller CA, Levine BD. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H233–H241. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.h233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman JH, Tukey JW. A projection pursuit algorithm for exploratory data analysis. IEEE Transactions on Computers. 1974;23:881–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman JH, Stuetzle W. Projection pursuit regression. Am Stat Assoc. 1981;76:817–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doncaster CP, Davey AJH. Analysis of Variance and Covariance: How to Choose and Construct Models for the Life Sciences. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harder DR, Roman RJ, Gebremedhin D, Birks EK, Lange AR. A common pathway for regulation of nutritive blood flow to the brain: arterial muscle membrane potential and cytochrome P450 metabolites. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:527–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1998.tb10702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coulson RJ, Cipolla MJ, Vitullo L, Chesler NC. Mechanical properties of rat middle cerebral arteries with and without myogenic tone. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:76–81. doi: 10.1115/1.1645525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korthius RJ. Skeletal Muscle Circulation. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; Rafael, CA: 2011. Regulation of Vascular Tone in Skeletal Muscle. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavi S, Egbarya R, Lavi R, Jacob G. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: chemoregulation versus mechanoregulation. Circulation. 2003;107:1901–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057973.99140.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Wilson TE, Witkowski S, Cui J, Crandall GG, Levine BD. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase does not alter dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H863–H869. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00373.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White RP, Vallance P, Markus HS. Effect of inhibition of nitric oxide synthase on dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.