Abstract

Stored maternal factors in oocytes regulate oocyte differentiation into embryos during early embryonic development. Before zygotic gene activation (ZGA), these early embryos are mainly dependent on maternal factors for survival, such as macromolecules and subcellular organelles in oocytes. The genes encoding these essential maternal products are referred to as maternal effect genes (MEGs). MEGs accumulate maternal factors during oogenesis and enable ZGA, progression of early embryo development, and the initial establishment of embryonic cell lineages. Disruption of MEGs results in defective embryogenesis. Despite their important functions, only a few mammalian MEGs have been identified. In this review we summarize the roles of known MEGs in mouse fertility, with a particular emphasis on oocytes and early embryonic development. An increased knowledge of the working mechanism of MEGs could ultimately provide a means to regulate oocyte maturation and subsequent early embryonic development.

Keywords: Embryonic development, Maternal factor, Mice, Oocytes, Zygotic gene activation

Introduction

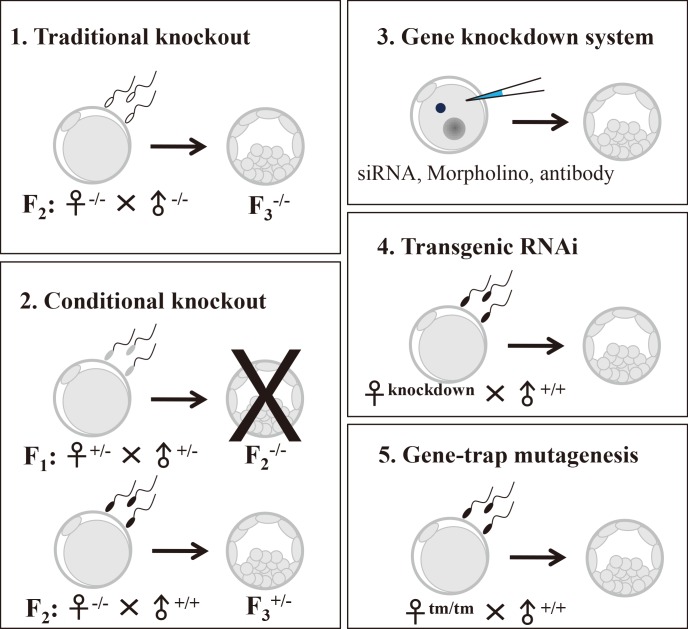

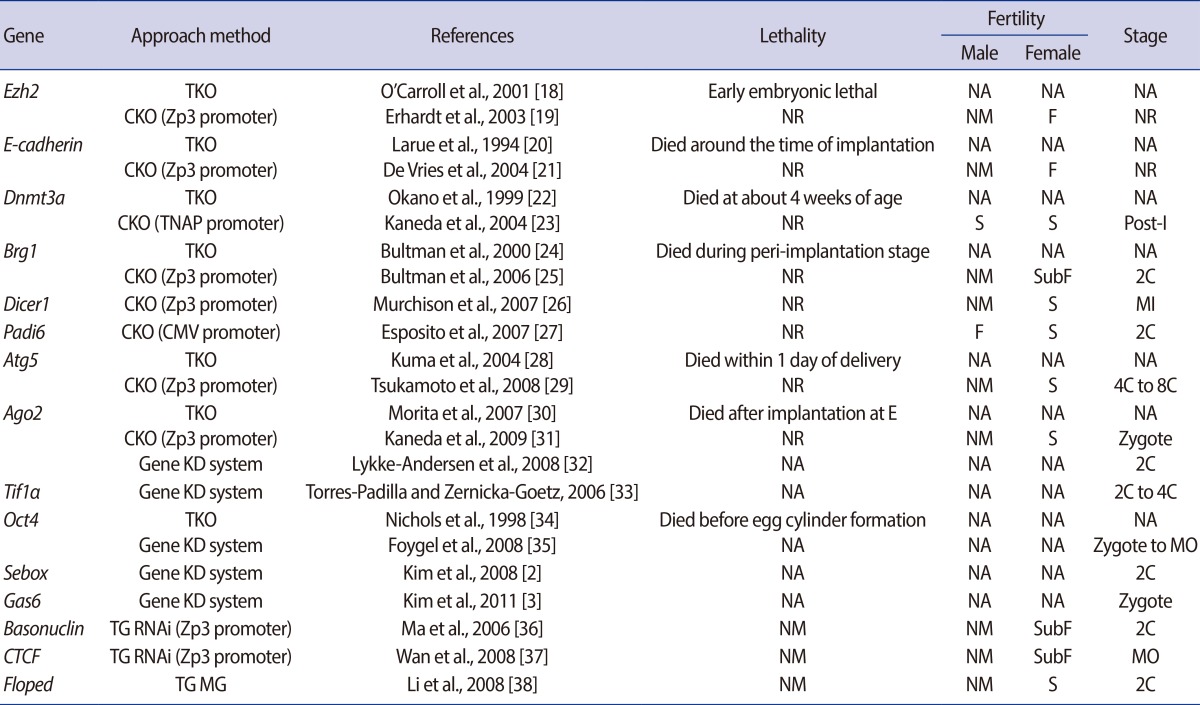

Abundant transcripts and proteins are produced and stored in oocytes during their growth and development to function during completion of meiosis, fertilization, embryonic cell divisions, zygotic gene activation (ZGA), and early embryogenesis until implantation has occurred. Maternal effect genes (MEGs) refer to the genes whose products have little effect on oocyte development, maturation, ovulation, and fertilization, but which activate the embryonic genomes and initial organization of embryonic cell lineages. Accordingly, the absence of MEGs hinders early embryonic development [1]. Currently, increasing numbers of MEGs have been identified using various gene knockout approaches in the mouse (Table 1), including the tissue-specific Cre-loxP system, the gene knockdown system, transgenic ribonucleic acid interference (RNAi), and gene-trap mutagenesis (Table 2).

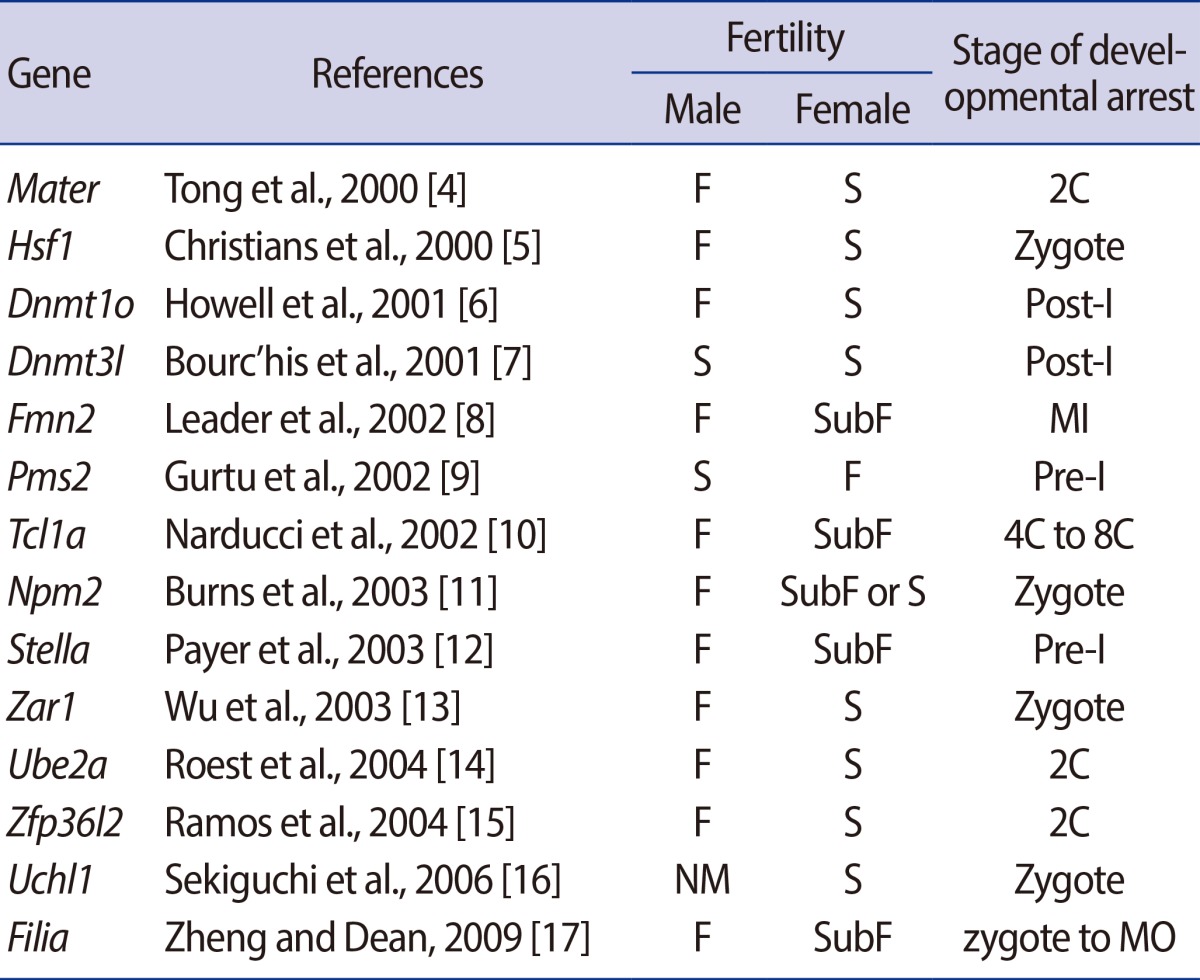

Table 1.

MEGs identifies by using the traditional knockout approach and their resultant reproductive performance with the stage of their embryonic arrest

MOMEGs, maternal effect genes; F, fertile; S, sterile; 2C, two cell stage; Post-I, postimplantation; SubF, subfertile; MI, metaphase I; NM, not mentioned; MO, morula.

Table 2.

MEGs found by using various approaches and their resultant reproductive performance with the stage of their embryonic arrest

MEGs, maternal effect genes; TKO, traditional knockout; NA, not available; CKO, conditional knockout; NR, not related; NM, not mentioned; F, fertile; S, sterile; Post-I, postimplantation; SubF, subfertile; 2C, two cell stage; Gene KD system, gene knockdown system; MI, metaphase I; MO, morula; TG MG, gene-trap mutagenesis; TG RNAi, transgenic RNAi.

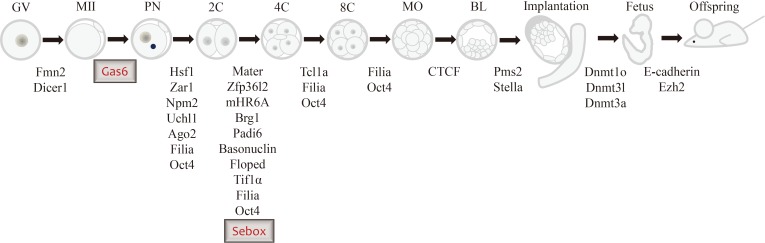

In this mini-review, we summarize the core information regarding each gene by categorizing MEGs according to the biotechnical tools used to uncover their functions (Tables 1, 2). We conclude by discussing skin-embryo-brain-oocyte homeobox (Sebox) and growth arrest-specific protein 6 (Gas6) as new candidates for investigation according to our findings using RNAi [2,3].

Traditional gene knockout

There are 14 MEGs that have been revealed by traditional knockout animals. These are: maternal antigen that embryos require (Mater), heat shock factor 1 (Hsf1), oocyte-specific deoxynucleic acid (DNA) methyltransferase-1 (Dnmt1o), DNA-cytosine-5-methyltransferase 3-like (Dnmt3l), formin2 (Fmn2), postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (Pms2), T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 1a (Tcl1a), nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin 2 (Npm2), germ and embryonic stem cell enriched protein (Stella), zygote arrest 1 (Zar1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2A (Ube2a), zinc finger protein 36, C3H type-like 2 (Zfp36l2), ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (Uchl1), Filia.

1. Mater

MATER was first identified as an oocyte antigen in the mouse model of autoimmune premature ovarian failure and determined as a MEG by analyzing null mutations in mice. Mater transcripts are expressed in the ovary and, in particular, the oocyte but not in other tissues. The MATER protein is encoded by a single-copy gene that is detected in the cytoplasm of growing oocytes and which is expressed until the late blastocyst stages [39,40].

Mater-/- mice deliver pups at an approximately equal sex ratio without phenotypic abnormalities. Mater-/- male mice are fertile, and Mater-/- female mice also exhibit normal folliculogenesis, oogenesis, ovulation, and fertilization. In addition, the first cleavage event is normal during preimplantation embryonic development. However, Mater-/- female mice are sterile because embryonic development is blocked at the two-cell (2C) stage despite normal embryonic morphology. In addition, the number of ovulated oocytes and embryos produced in Mater-/- female mice are similar to that of normal females. These results demonstrate that Mater is essential for embryonic development beyond the 2C stage in mice [4].

The subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) that forms during oogenesis has also been shown to be necessary for embryonic development beyond the 2C stage [38]. Located in the subcortex of oocytes and embryos, the SCMC is composed of MATER, FLOPED, transducin-like enhancer of split 6 (TLE6), and FILIA [17]. MATER, FLOPED, and TLE6 interact directly with each other, while FILIA interacts only with MATER. Therefore, MATER and its oocyte-specific binding partners are necessary for the first embryonic cleavage event.

2. Hsf1

HSF1 is a major transactivator of stress-inducible genes activated by heat and other stress stimuli [41]. Hsf1-/- female mice have normal folliculogenesis and oogenesis [5]. In addition, oocytes from Hsf1-/- female mice are arrested at metaphase II until fertilization, and the zygotes have two pronuclei and a second polar body, indicating that ovulation and fertilization in Hsf1-/- female mice occurs normally. Hsf1-/- females mated with Hsf1+/+ or Hsf1+/- males produce embryos that are unable to develop properly beyond the zygotic stage. Additionally, the ultrastructure of the nuclei of 2C embryos from Hsf1-/- female are abnormal. These findings led Christians et al. [5] to conclude that a 'maternal effect mutation' (i.e., the deficiency of Hsf1 from the mother) controls early post-fertilization development and results in infertile Hsf1-/- females.

3. Dnmt1o

DNMT1 maintains genomic methylation patterns in mammalian somatic cells. Though oocytes and preimplantation embryos lack DNMT1 expression, they do have its variant DNMT1O, which is found in the nuclei of early growing oocytes and in the cytoplasm of mature oocytes. DNMT1O is expressed in the cytoplasm at the 2C and 4C stages, in only the nucleus at the 8C stage, and again only in the cytoplasm at the blastocyst stage. This suggests a spatially diverse expression pattern for DNMT1O throughout the early stages of embryonic development [42]. In a study by Howell et al. [6], Dnmt1o was deleted by elimination of the oocyte-specific promoter and first exon using traditional knockout technology. This deletion mutant is called DnmtΔ1o. Knockout males are fertile, whereas DnmtΔ1o females exhibit a phenotype during gestation. DnmtΔ1o embryos are not affected during early embryonic development; they implant and develop after implantation. However, because of deficiencies in the uterine environment, nearly all DnmtΔ1o embryos die between embryonic days 14 and 21, and rare DnmtΔ1o survivors die within 24 hours after birth [6].

4. Dnmt3l

With sequence similarity to DNMT3A and DNMT3B, DNMT3L has been shown to catalyze de novo methylation of CpG islands. DNA methyltransferases and regulatory factors are involved in the establishment of maternal imprints in growing diplotene oocytes and paternal imprints in perinatal prospermatogonia [43,44].

In a study by Bourc'his et al. [7], Dnmt3lG mice were generated by replacing four exons of the Dnmt3l gene with a β-galactosidase-neomycin phosphotransferase fusion gene under the control of the Dnmt3l promoter. Both sexes of Dnmt3lG/G mice are viable but sterile. In Dnmt3lG/G males, neonatal testes contain a normal component of germ cells, while adult testes contain only Sertoli cells and have severe hypogonadism. Oogenesis in Dnmt3lG/G females is normal, but there is a lethal maternal-effect in that Dnmt3lG/+ embryos from Dnmt3lG/G females fail to develop at mid-gestation due to pericardial edema with exencephaly and other neural tube defects. Furthermore, the paternally imprinted H19 gene is normally methylated in Dnmt3lG/+ progeny from Dnmt3lG/G females, whereas the maternally imprinted genes, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N and paternally expressed gene 1, are unmethylated. These results suggest that Dnmt3l is required for the establishment of maternal imprints during oogenesis, but is not required for the maintenance of paternal imprints. Global genome methylation levels are also not affected by removal of Dnmt3l [7].

5. Fmn2

Fmn2 was identified as a gene that is expressed in the developing and mature central nervous system, including the spinal cord and brain [45]. FMN2 is highly homologous to the Drosophila cappuccino protein, which is a Drosophila MEG required for polarity of the egg and embryo [46]. FMN2 is essential for establishment of cell polarity, cytoskeleton organization, meiotic maturation, and regulation of asymmetrical spindle positioning in mouse oocytes [47,48].

FMN2 was determined to function like a MEG by analyzing Fmn2-/- mice [8]. Fmn2+/- mice are phenotypically normal, and Fmn2-/- mice have normal development of the central nervous system and a normal sex distribution. Fmn2-/- male mice are fertile, but Fmn2-/- female mice are subfertile in that they only give birth to 1-3 offspring of which only a few survive.

In Fmn2-/- mice, emission of the first polar body occurs in only 3% of oocytes, of which the rest are arrested at metaphase of meiosis I. These oocytes have a loss of normal barrel-shape spindles and centrally located chromosomes which cause a parthenogenic cell division. In spite of inaccurate positioning of the metaphase spindle during meiosis I, Fmn2-/- oocytes form the first polar body. These findings suggest that FMN2 is necessary for microtubule-independent chromatin positing. When Fmn2-/- oocytes were microinjected with Fmn2 messenger RNA (mRNA), these oocytes were rescued from meiotic incompetence and showed first polar body formation [8]. Furthermore, because of meiotic incompetence in Fmn2-/- oocytes, embryos from Fmn2-/- oocytes appear polyploidy, such as triploid and pentaploid. Fmn2-/- females have a small number of implantation sites in the uterus and contain embryos with morphological defects, such as developmental delay and placental resorption caused by gross morphological defects. These results led to the conclusion that the deletion of Fmn2 arrests oocytes at metaphase of meiosis I and results in subfertility in Fmn2-/- female mice [8].

6. Pms2

A DNA mismatch repair gene homolog, PMS2 is required for methyl-directed post-replication mismatch repair and was identified as a MEG using null mutation mice [49]. Homologous Pms2 mutations do not affect embryonic or neonatal lethality. Pms2-/- males fail to produce offspring by having a reduced number of normal spermatozoa (<25% that of wild-type males) in the epididymis. Progression of spermatogenesis is first disrupted at the primary spermatocyte stage, and Pms2-/- males have abnormalities in chromosome synapsis at meiotic prophase I. Also, microsatellite instability (MSI) has a frequency of approximately 10% in the sperm from Pms2-/- males, suggesting a role for PMS2 in the differentially methylated region (DMR) [49].

To determine the consequences of maternal Pms2 deficiency on genetic stability, DNA isolated from the tail was analyzed for polymorphisms between maternal and paternal alleles using microsatellite markers [9]. In heterozygous offspring derived from Pms2-/- oocytes, MSIs in the maternal alleles were detected with an average frequency of 9.1%, which is a frequency similar to that observed in Pms2-/- males. However, MSI was not observed in control offspring. Although they have a functionally defective DMR, Pms2-/- females are fertile with a normal pregnancy rate and litter size [49].

7. Tcl1a

TCL1A interacts with AKT to increase AKT kinase activity and plays an important role in the transduction of anti-apoptotic and proliferative signals in T-cells [50]. As a developmental regulator, TCL1A is expressed in the ovary, testis, early developmental stage embryo, fetal thymus, and bone marrow [51]. Tcl1a mRNA and protein are present from germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes up to stage 2C embryos, but their presence is dramatically decreased in later embryonic developmental stages [51].

In a study by Narducci et al. [10], Tcl1a-/- mice were produced by removing exons 2, 3, and 4 of the coding region. Tcl1a-/- males and females are viable and show no discernible histological abnormalities. Tcl1a-/- males are fertile, and the ovaries of Tcl1a-/- females are histological normal. Additionally, Tcl1a-/- females appear to have normal folliculogenesis, oogenesis, oocyte maturation, ovulation, and fertilization. These results indicate that TCL1a does not affect follicle development and concurrent oogenesis. However, Tcl1a-/- embryos fail to develop beyond the 4C-8C stage, and development is slower than that for wild-type embryos, with Tcl1a-/- embryos exhibiting a delayed or arrested blastomere proliferation [10]. Tcl1a-/- females produce fewer offspring than Tcl1a+/- and Tcl1a+/+ females. Moreover, the number of pups from Tcl1a-/- females is smaller. These findings indicate that Tcl1a-/- females are subfertile.

8. Npm2

NPM2, an oocyte-specific nuclear protein, was identified using a polymerase chain reaction suppression-subtraction ovary library [11]. Transcripts of Npm2 are limited in growing oocytes. NPM2 protein is expressed in the nucleus of oocytes before GV breakdown (GVBD) and in the cytoplasm after GVBD. NPM2 is detected in both pronuclei after fertilization, remains in nuclei until the 8C stage, and is barely expressed in the blastocyst stage.

Npm2-/- male mice are normal and fertile, whereas Npm2-/- female mice are subfertile or infertile. The ovaries from Npm2-/- females have normal oogenesis, and Npm2-/- oocytes have normal maturation and fertilization. However, Npm2-/- embryos are not cleaved beyond the 2C stage. Taken together, Npm2-/- female mice have defects in early embryogenesis, such as an absence of coalesced nucleolar structures, loss of heterochromatin formation, and deacetylation of histone H3. The authors of these findings concluded that Npm2 is a MEG that is vital for nuclear and nucleolar organization in oocytes and in embryo development for the specific stages from zygote to 2C transition [11].

9. Stella

STELLA was identified during early embryonic gonadal development in the mouse [52]. Stella is a novel gene expressed in primordial germ cells (PGCs), oocytes, and early developmental stage preimplantation embryos [53]. STELLA protein is expressed in the cytoplasm of oocytes and embryos, and especially in pronuclei of zygotes. Stella-/- mice have a similar number of PGCs to that of normal mice, suggesting no relationship between Stella and development of early gonadal PGCs. Furthermore, testes and ovaries of Stella-/- adult mice have no histological abnormalities, and Stella-/- male mice have normal fertility. Indeed, Stella-/- female mice have follicles at all developmental stages with normal ovulation and no significant differences in the number of oocytes compared to that of wild-type mice. However, it is obvious that Stella-/- female mice have reduced fertility as Stella-/- embryos exhibit developmental failure during early embryogenesis. Stella-/- embryos are arrested at the zygote (49%), 2C (10%), and morula (27%) stages, and only 15% of Stella-/- embryos develop to the blastocyst stage. When Stella-/- females are mated with wild-type males, Stella-/- females produce only a few offspring in a small litter size [12].

10. Zar1

A novel oocyte-specific gene, Zar1 was identified by using subtractive hybridization and screening of a mouse ovarian cDNA library [13]. Zar1 transcripts are detected at high levels from growing oocytes up to zygote embryos, but are markedly reduced in 2C embryos and are not present until the blastocyst stages. The rapid disappearance of Zar1 expression at the 2C stage suggests an essential role in the oocyte-to-embryo transition [13].

Zar1-/- males are fertile, whereas Zar1-/- females are infertile. In Zar1-/- females, all stages of follicle development and corpus lutea formation are detected. In addition, Zar1-/- oocytes resume meiosis and progress to metaphase II and form two pronuclei after fertilization. Hence, the functions of folliculogenesis, oogenesis, fertilization, and the first cleavage event in Zar1-/- females are indistinguishable from that of wild-type mice. However, most Zar1-/- embryos are arrested mainly at the zygote stage, while some are arrested at the 2C stage, and no embryos develop to the 4C stage, which results in sterility of the Zar1-/- female [13].

11. Ube2a

Ube2a, a RAD6-homologous gene, is required for DNA repair and functions as a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme [54]. Ubiquitin-conjugation signaling requires the activity of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes and results in proteolytic degradation of protein. The body weight of Ube2a-/- mice is lighter than their wild-type littermates by 12% [14]. Ube2a-/- male mice are fertile, but Ube2a-/- female mice are not able to produce litters. Ovaries from Ube2a-/- female mice appear to have normal numbers of follicles and corpus lutea, indicating normal follicular development and ovulation. After fertilization, Ube2a-/- embryos contain two pronuclei, which suggests normal fertilization. However, wild-type embryos develop into the hatched blastocyst stage, whereas Ube2a-/- embryos remain at the 2C stage and some embryos are degraded with severe cytoplasmic fragmentation. These results suggest that maternal Ube2a is essential for preimplantation embryonic development [14].

12. Zfp36l2

ZFP36l2 can bind to mRNAs containing class II AU-rich elements, followed by degradation of the target mRNA [55]. Zfp36l2-/- females are completely sterile, whereas Zfp36l2-/- males are fertile. Zfp36l2-/- females exhibit typical estrous cycles, normal sexual behavior, and normal anatomy of their reproductive tracts. Ovaries from Zfp36l2-/- mutant females also appear anatomically and histologically normal with the presence of follicles at all developmental stages. Possible uterine and corpus luteum defects were ruled out by investigating successful pregnancies after transplantation of wild-type embryos into Zfp36l2-/- uteri. By performing classical wild-type ovary transplantation to rescue Zfp36l2-/- female sterility, a potential ovarian etiology for Zfp36l2-/- female infertility was also ruled out. Zfp36l2-/- females were additionally shown to ovulate morphologically normal oocytes, but with an overall reduction in the number of oocytes compared with that from wild-type females. Although the oocytes from Zfp36l2-/- females undergo meiosis and are fertilizable, the embryos do not progress beyond developmental stage 2C. These results indicate that embryonic arrest at stage 2C accounts for the infertility in the Zfp36l2-/- female [15].

13. Uchl1

One of many deubiquitinating enzymes, UCHL1 is expressed in the ovary, testis, placenta, and neuron [56,57,58]. UCHL1 associates with monoubiqutin, prolongs the half-life of ubiquitin in neurons, and resists apoptotic stress in testicular germ cells [58,59]. UCHL1 is expressed in the plasma membranes of oocytes and early embryos, including the outer layer cells of the trophectoderm in blastocyst stage embryos, but not in the cytoplasm of oocytes and embryos [16].

The gracile axonal dystrophy (gad) mouse is an autosomal recessive mutant that shows sensory ataxia at an early stage, followed by motor ataxia at a later stage. The gad mutation is transmitted by the Uchl1 gene on chromosome 5 [60,61]. Because of a deletion of the nucleotide sequences encoded by exons 7 and 8 in Uchl1gad/gad knockout mice, the Uchl1gad allele predicts a truncated UCHL1 protein [62]. Uchl1gad/gad female mice have morphologically normal oocytes, follicles of all developmental stages, and corpus lutea in the ovaries. Additionally, the number of ovulated oocytes is not significantly different between Uchl1gad/gad mice and wild-type mice. These observations suggest that the deletion of Uchl1 does not affect the estrous cycle, oogenesis, folliculogenesis, or ovulation. However, when Uchl1gad/gad female mice were mated with Uchl1gad/gad males, Sekiguchi et al. [16] found that embryos had three or more pronuclei, indicating polyspermic fertilization. Uchl1gad/gad female mice therefore had a significantly decreased litter size. The monoubiquitin level was also lower in oocytes from Uchl1gad/gad females, suggesting that UCHL1 is a fusion protein on the plasma membrane and plays a role in blocking polyspermy.

14. Filia

Filia transcripts are expressed in growing oocytes and is degraded during oocyte maturation, whereas FILIA protein persists during early embryogenesis. FILIA binds to MATER and participates in SCMC formation that is crucial for preimplantation embryo development [38]. In a study by Zheng and Dean [17], Filia was deleted in mouse ESCs, such that the transcriptional and translational start sites as well as the first 2 exons of the cording region were removed. Filia-/- male mice have normal fertility, whereas Filia-/- females have markedly reduced (about 50%) fecundity. There are significantly reduced percentages of Filia-/- embryos that reach the morula and blastocyst stages when compared with wild-type embryos, with Filia-/- embryos being mostly delayed at the 3C to 4C stages.

FILIA is required for placement of MAD2, a crucial component of the spindle assembly checkpoint, at kinetochores. However, AURKA, PLK1, and γ-Tubulin are completely absent in affected embryos from Filia-/- females, and significantly higher rates of hyperploidy with abnormal spindle formation and chromosome misalignment are detected in Filia-/- embryos [17].

Conditional gene knockout

When using traditional knockout technology, F1 heterozygous parents may not produce F2 null mutant offspring, if the F2 null homozygotes die during embryogenesis or are dead at birth. Therefore, another method is required to delete the genes that cause lethality when targeted by traditional knockout methods. This new method is the conditional knockout system. With this system, genes can be deleted using the tissue-specific Cre-loxP system under the control of tissue-specific promoters, such as the Zp3 promoter in the case of oocyte-specific expression. Cre-loxP recombination is frequently used to generate a conditional knockout animal in which a target gene is only deleted in a specific tissue or at a specific time. When cells with loxP sites in their genome express Cre recombinase, the Cre recombinase excises the DNA fragment located between the two loxP sites [63]. As such, the conditional gene knockout technique reduces the risks associated with traditional knockout techniques, such as embryonic lethality and complex phenotypes.

1. Ezh2 (Enhancer of zeste 2)

A SET domain-containing protein, EZH2 and its interacting partner, embryonic ectoderm development (EED), are polycomb group proteins that form an EZH2-EED complex which is crucial for early development control, such as epigenetic regulation of gene expression [64]. EZH2 is mainly expressed in early development and interacts with DNMT1 and DNMT3A, which are DNA methyltransferases that are known MEGs [65]. The EZH2-EED complex is essential for histone H3-K27 methylation during imprinted X inactivation [66]. EZH2 proteins are also expressed in growing oocytes but not in surrounding somatic cells [19].

Ezh2 homozygous null mutations are embryonic lethal mutations [18]. Deletion of maternal Ezh2 by conditional knockout (EzhF/F-Zp3-Cre) was obtained using the combination of Cre-recombinase driven by Zp3 regulatory elements (Zp3-Cre) and the Ezh2 gene (exons 8-11) flanked by loxP sites. When Ezh2-deficient oocytes were fertilized with wild-type sperm, Ezh2DEL/F offspring without maternal Ezh2 displayed severe growth retardation.

The EZH2-EED complex is associated by histone H3-me2-K27 in X inactivation. However, EZH2 depletion disrupts histone H3 methylation, whereby H3-K9 and H3-K27 are almost undetectable either during oocyte development or in the zygote. Therefore, EZH2 interacts with EED and plays an essential role in early development and in pluripotent embryonic stem cells through mechanisms such as methylation of histone H3-K27 and histone H3-K9; however, this essential role does not appear to carry over to differentiated cells [19].

2. E-cadherin

A specific calcium ion-dependent cell adhesion molecule, E-cadherin plays an essential role in determination of cell-cell adhesion and cell shape. The cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin binds to β-catenin, and these proteins form the E-cadherin-catenin adhesion complex with the actin filament network. The transcription of mouse E-cadherin is under the regulation of the transcription factor snail [67]. E-cadherin also contributes to the process of compaction at the 8C stage [21].

Homozygous null mutant mice for E-cadherin show an early embryonic lethality through failure to form an intact trophectoderm cell layer [20]. Using the combination of the oocyte-specific Zp3-Cre transgene and floxed alleles, live-born litters were obtained from maternal E-cadherin-deficient embryos [21,68]. In these studies, low levels of E-cadherin expression from the paternal allele in E-cadherin-deficient embryos were detected at the morula stage, and adhesion did not occur until the morula stage. E-cadherin-deficient embryos had delayed cell division, but progressed compaction of individual blastomeres. β-catenin expression in E-cadherin-deficient embryos is detected only in the pronuclei in zygotes and nuclei at the 2C stage, whereas it is detected at the surface of the 2C and 8C stages of normal embryos. E-cadherin and β-catenin are required for adhesion of individual blastomeres during compaction and trophectoderm formation [21].

3. Dnmt3a (DNA methyltransferase 3a)

DNMT3A plays crucial roles in genomic imprinting, X chromosome inactivation, and mammalian development [69]. Using Northern blot and semi-quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis, Dnmt3a expression was detected as ubiquitous in the fetal testis, fetal ovary, and all adult tissues [70,71]. Dnmt3a-/- mice develop to term and appear to be normal at birth. However, most Dnmt3a-/- mice are runts after birth and die at about 4 weeks of age [22]. Therefore, the function of Dnmt3a was analyzed using the Cre-loxP system. In the early postnatal stage, Dnmt3a2lox/1lox, TNAP-Cre conditional mutant mice appear to have a reduction of about 20% in body weight when compared with wild-type littermates, but survive to adulthood and reach a normal body weight. Dnmt3a-/-, TNAP-Cre conditional mutant female mice are infertile. Embryos are smaller than wild-type embryos at embryonic day (E) 9.5 and exhibit developmental defects, such as a smaller size, open neural tube, a lack of branchial arches, and pale skin at E10.5. In addition, the pattern of maternal methylation at DMRs and other sequences are affected during oogenesis upon disruption of Dnmt3a.

Dnmt3a2lox/1lox, TNAP-Cre conditional mutant male mice are also sterile. The testis weight of mutant male mice is decreased compared with that of wild-type mice due to a reduced number of spermatogonia at postnatal day 11. Mutant male mice that are 11 weeks old have testes that contain only a few spermatocysts and no spermatids or spermatozoa. These observations indicate that Dnmt3a is essential for spermatogenesis and functions as a MEG [23].

4. Brg1 (BRM/SWI2-related gene 1; Smarca4)

BRG1, a catalytic subunit of mammalian SWI/SNF-related chromatin remodeling complexes, regulates transcription and remodeling of nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner [72]. Brg1-/- mice die during the peri-implantation stage [24]. Neither the inner cell mass (ICM) nor trophectoderm survive during blastocyst outgrowth studies. Experiments with other cell types, however, have demonstrated that BRG1 is not a general cell survival factor. Therefore, the function of Brg1 as a MEG was demonstrated using the Brg1Zp3/Cre conditional mutant.

In the study by Bultman et al. [25], Brg1Zp3/Cre females produce normal 2C embryos, suggesting that BRG1 does not affect oocyte growth, maturation, meiosis I, ovulation, fertilization, or the first cleavage event. However, the majority of embryos (78%) from Brg1Zp3/Cre females are arrested at the 2C and 4C stages and only 12% of embryos advance to the blastocyst stage. Furthermore, maternal Brg1 transcripts are degraded and replaced by ZGA in wild-type mice, but not in maternally depleted embryos. It was concluded that BRG1 is essential for ZGA and is linked to histone modification, particularly to histone H3-K4 methylation. Furthermore, transcriptional activity of these embryos is reduced by about 35%. Using Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer analysis, Bultman et al. [25] found that BRG1 is involved in the regulation of transcription, RNA processing, and the cell cycle.

5. Dicer1

A conserved ribonuclease, Dicer1 is required for formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which is composed of Dicer1, EIF2C2/AGO2, and TARBP2. Dicer is required to process precursor microRNAs (miRNAs) to mature miRNAs and then load them onto EIF2C2/AGO2 [73]. In addition, Dicer processes long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into many small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [74]. Through the RNAi pathway, miRNAs and siRNAs regulate turnover of many maternal transcripts in oocytes [26,75].

In a study by Murchison et al. [26], Dicer1 conditional knockout mice were produced by combining a conditional Dicer1-floxed allele with a Cre recombinase transgene expressed from the Zp3 promoter. The normal numbers of GV oocytes are recovered from Dicer1 conditional knockout (Dicer1flox/flox; Zp3-Cre) females. In addition, Dicer1-/- oocytes show a normal structure with a normal shape of the GV. These results suggest that Dicer1 expression in oocytes is not involved in oocyte growth, development, and response to gonodotropins. Most Dicer1-/- oocytes undergo GVBD, but fewer Dicer1-/- oocytes extrude a polar body, revealing an arrest at meiosis I in mature Dicer1-/- oocytes. Dicer1-/- oocytes also have multiple spindles with misaligned chromosomes. These results indicate that Dicer1 is required for completion of oocyte mitotic maturation, spindle organization, and chromosome configuration. The authors of the study concluded that the deletion of Dicer1 in oocytes affects the oocyte transcriptome, which results in meiosis I arrest and infertility in the Dicer1-/- female mouse [26].

6. Padi6 (Peptidyl arginine deiminase 6)

A member of the peptidyl arginine deiminase family, PADI6 is involved in the posttranslational modification of arginine into citrulline through a process called citrullination [76]. PADI6 protein is detected in mammalian sperm, in oocytes at all stages from primordial to ovulatory follicles, and persists in embryos up to the blastocyst stage. PADI6 localizes to the cytoplasmic lattice of oocytes, which is a fibrillar matrix of so-called cytoskeletal sheets [77], and the PADI6 protein is important in ribosome storage in the cytoplasmic lattices of oocytes and the ZGA [78].

In Padi6 conditional knockout mice, the Padi6 gene is disrupted by using loxP and a CMV-Cre transgenic line [27]. Homologous Padi6 mutant mice are viable and born at the expected Mendelian ratio. No phenotypical or histopathological abnormalities are observed in any tissue. Homologous Padi6 mutant male mice are fertile, whereas female mice are infertile. PADI6 appears not to play a role in oocyte growth, maturation, and ovulation. Furthermore, PADI6 is not required for fertilization and pronuclear formation. However, homologous Padi6 mutant zygotes do not progress beyond the 2C stage of development. Therefore, maternally-expressed PADI6 plays an essential role in the organization of the cytoskeletal sheets through citrullination of oocyte-specific keratins. The fertility defect with deficiency of citrullination results in dispersion of the cytoskeletal sheets, and these results indicate that Padi6 is a mammalian MEG [27].

7. Atg5 (Autophagy-related 5)

ATG5 is a crucial component for autophagosome formation and is an acceptor molecule for ATG12 [79]. By the ubiquitin-proteasome system, maternal protein degradation accelerates after fertilization and is apparent at the 2C stage in mammals [80,81]. Autophagy, another important maternal protein degradation system, is a process by which cytoplasmic constituents in the lysosome are degraded. Autophagy plays an essential role during early embryogenesis [29,82]. Although many studies have suggested a possible role for autophagy in development, traditional Atg5-/- knockout mice are born at the expected Mendelian ratio, are normal at birth, but die within 1 day of birth as a consequence of low nutrient status [28].

Atg5 conditional knockout mice (Atg5flox/--Zp3-Cre) were produced by crossing the mouse lines bearing an Atg5flox allele to a Zp3-Cre transgenic line [29]. Despite exhibiting completely defective autophagy, normal ranges of superovulated oocytes are recovered from Atg5flox/--Zp3-Cre female mice and they are fertilized normally. These results suggest that autophagy is not important for oogenesis, oocyte maturation, and fertilization. Atg5flox/--Zp3-Cre female mice also produce smaller pups when mated with wild-type males because the deficiency in autophagy is rescued by zygote-derived ATG5. In contrast, fertilization of Atg5-null oocytes with Atg5-null sperm results in the arrest of early embryonic development. Atg5-null embryos do not develop and remain at the 4C or 8C stage. These results suggest that autophagy deficiency causes arrest of early embryonic development at the 4C or 8C stage [29].

8. Ago2 (Argonaute 2)

AGO2 is a key factor of the RISC complex, which is essential for miRNA- or siRNAs-mediated repression of target genes. The RISC complex targets miRNAs or siRNAs to specific mRNAs that are cleaved or translationally inhibited [83]. Through reducing the polyA tail of mRNA and inhibiting translation, all four members of the AGO family (AGO1 to AGO4) can repress target gene expression [84]. Only AGO2, however, has slicer activity that cleaves the target mRNA [83]. It has been found that Ago2 mRNA is expressed in oocytes and throughout all early embryonic developmental stages [32], and that AGO2 protein is localized to the cytoplasmic P-bodies in oocytes that serve as sites for mRNA destruction and decay [85].

By traditional gene targeting, Morita et al. [30] demonstrated that Ago2-/- mice exhibit embryonic lethality at around E5.5. In another study of Ago2 conditional knockout mice, Ago2 function was disrupted by crossing mice with an Ago2 floxed conditional allele and Zp3-Cre transgenic mice [84]. Ovaries from homologous Ago2 conditional knockout (Ago2F/F-Zp3-Cre) females appear to be normal, and MII oocytes are morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type oocytes in their appearance, maturity, size, and numbers. However, spindle formation and chromosome configuration are abnormal. Moreover, miRNA is decreased by about 80% in Ago2 knockout oocytes as compared with wild-type oocytes. These results indicated that Ago2 is essential for the biogenesis or stability of mRNAs during oogenesis. In addition, mutant embryos fail to undergo the first cleavage event and are fragmented. Therefore, Ago2F/F-Zp3-Cre female mice are infertile [31].

Following the microinjection of Ago2 dsRNA into the cytoplasm of pronuclear embryos, embryonic development arrests at the 2C stage and development does not progress to the blastocyst stage. Specifically, Ago2 dsRNA-injected embryos exhibit a 90% knockdown of Ago2 mRNA [32]. These results led to the conclusion that Ago2 is a mammalian MEG that is essential for degradation of a proportion of maternal transcripts that is mediated by the RNAi pathway.

Gene knockdown system

To assess the function of target genes during oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis, dsRNA, siRNA, antisense morpholino oligonucleotides, or specific antibodies are microinjected into oocytes or zygotes resulting in a loss-of-function for the target gene. This system is a well-established and useful tool for gene function analysis.

1. Tif1α (Transcriptional intermediary factor 1 alpha; Trim24)

A transcriptional regulator of nuclear receptors, TIF1α has been shown to interact with proteins related to chromatin structure [86]. Tif1α transcripts are expressed from GV oocytes to blastocysts. Additionally, Tif1α mRNA is present in all blastomeres, but is restricted to the ICM when blastocysts are formed. TIF1α protein is also expressed in the cytoplasm of oocytes, but it moves to the pronuclei at the zygote stage after fertilization. During embryogenesis, TIF1α protein remains in nucleolar-like bodies and is associated with transcription machinery factors and chromatin remodelers such as Snf2h and Brg1. Therefore, disruption of Tif1α leads to mislocalization of RNA polymerase II, Snf2h, and Brg1. Lastly, TIF1α modulates gene expression during ZGA via Snf2h [33].

Tif1α dsRNA was microinjected into the cytoplasm of zygotes in a study by Torres-Padilla and Zernicka-Goetz [33]. In this study, the majority of embryos injected with Tif1α dsRNA arrest between the 2C and 4C stage upon efficient knockdown of TIF1α protein. In addition, microinjection of antibodies into the cytoplasm of zygotes blocks TIF1α protein, and injected embryos arrest at the 2C to 4C stage of development. These results suggest that Tif1α is essential for early embryogenesis [33].

2. Oct4 (Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; Pou5f1)

The Oct4 gene is expressed in a tissue-specific pattern during early mammalian development [87]. Oct4 expression appears in oocytes and pluripotent early embryos. In mouse blastocysts, Oct4 transcripts and proteins are only present in the ICM but not in the trophectoderm [88]. As one of the Yamanaka factors, Oct4 induces epigenetic reprogramming of a somatic genome to an embryonic pluripotent state [89]. Using a traditional knockout approach, male and female mice that are heterozygous for Oct4 deletion are fertile but have 50% less pups than wild-type mice. Oct4-deficient embryos can develop up to the blastocyst stages, but ICM cells are not pluripotent. Therefore, Oct4 disruption results in peri-implantation lethality before egg cylinder formation and offspring are not produced [34].

Oct4-morpholino was microinjected into the cytoplasm of zygotes by Foygel et al. [35]. The results of this study demonstrate that embryos lacking OCT4 are mainly blocked at the zygote and/or morula stages and do not develop to the blastocyst stage. The embryos are rescued and develop to the blastocyst stage when the embryos are co-injected with Oct4 mRNA and morpholino. These results suggest that Oct4 is important for early embryogenesis [35].

3. Sebox (Skin-embryo-brain-oocyte homeobox)

We recently applied RNAi as a tool for functional analysis of genes expressed in oocytes. To determine the role played by target genes in oocyte maturation and preimplantation embryo development, RNAi was used to knockdown target gene expression in the mouse. While we carried out RNAi for several genes, we could categorize transcripts in oocytes into three groups, with loss-of-function stopping meiosis at GV [90], MI [91,92,93,94,95], and MII [2,3]. Therefore, transcripts in oocytes could be categorized as genes required for embryonic development and for oogenesis, as suggested by Dean [96].

The Sebox gene encodes a protein with a homeodomain motif that binds DNA and regulates gene expression [97]. Sebox transcripts are highly expressed in GV oocytes to stage 2C embryos, but expression is markedly decreased in later embryonic developmental stages [2]. Following the microinjection of Sebox dsRNA into the cytoplasm of GV oocytes, we found that the oocytes develop to the MII stage with normal configurations of spindles and chromosomes without changes in the activity of important kinases, such as maturation-promoting factor (MPF) and mitogen-activated protein kinase. However, when Sebox dsRNA was microinjected into the pronuclear embryos, we found that embryo development is inhibited at the 2C stage. Therefore, we conclude that Sebox is crucial for normal early embryogenesis and propose Sebox as a new mammalian MEG candidate [2].

4. Gas6 (Growth arrest-specific gene 6)

A ligand for AXL, TRYO3, and MERTK receptor tyrosine kinases, GAS6 is a member of the vitamin K-dependent protein family and is implicated in growth arrest, cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival [98,99]. GAS6 plays a pivotal role in thrombosis, hematosis, and spermatogenesis [99,100]. Similar to the expression pattern of other MEGs, expression of Gas6 is constitutive throughout oocyte maturation, gradually decreases from the pronuclear to the 4C-stage embryo, and slightly increases again from 8C to blastocyst-stage embryos [3].

To investigate the role of GAS6 in oocyte maturation and fertilization using RNAi, we microinjected Gas6 dsRNA into the cytoplasm of GV oocytes. Interestingly, despite the marked reduction in Gas6 expression after Gas6 RNAi, nuclear maturation is not affected, including spindle structures and chromosome segregation. However, Gas6 RNAi increases the phosphorylation of Tyr15 in p34cdc2 and MPF reactivation fails after the first polar body emission [3]. To confirm that cytoplasmic maturation was deficient, we evaluated the change in Ca2+ oscillation and cortical granule exocytosis and the rates of sperm penetration and pronuclear formation. Due to insufficient cytoplasmic maturation, Gas6-silenced MII oocytes exhibit markedly decreased cytoplasmic Ca2+ excitability, a lack of cortical granule exocytosis, and fertilization failure, especially pronuclear formation. Therefore, we propose Gas6 as another new candidate MEG vital for oocyte cytoplasmic maturation and normal fertilization [3].

Transgenic RNAi

Basonuclin and CCCTC-binding factor (Ctcf) have been identified as MEGs using an oocyte-specific gene-targeting method. These transcripts have been depleted from growing oocytes using transgenic RNAi under the control of the Zp3 promoter [36,37].

1. Basonuclin

Basonuclin, a zinc-finger protein, regulates rRNA transcription. Basonuclin co-localizes with RNA polymerase I (Pol I) activity in the nucleolus of mouse oocytes, and basonuclin mutation interferes with Pol I transcription [101]. Basonuclin mRNA has been detected in oocytes and zygotes, but its levels rapidly decrease at the 8C stage and disappear at the blastocyst stage. In a study by Ma et al., transgenic basonuclin-RNAi mice have apparently normal morphology, but female mice are subfertile with normal oocyte maturation and ovulation [36]. The ovaries from basonuclin-RNAi transgenic female mice exhibit normal size, weight, and number of follicles. However, some follicles have abnormal morphologies. For instance, basonuclin-deficient oocytes are biochemically abnormal and contain cytoplasmic dark granules, which are not detected in wild-type oocytes. Both RNA Pol I- and Pol II-mediated transcription is perturbed in basonuclin-deficient oocytes. Additionally, basonuclin-deficient embryos fail to develop beyond the 2C stage, which accounts for the observed subfertility. Thus, the authors suggest that basonuclin is a MEG due to the fact that basonuclin deficiency results in phenotypes that are similar to those for previously reported mouse MEGs [36].

2. Ctcf

CTCF is a multifunctional transcription factor with 11 zinc-finger DNA-binding domains. CTCF is proposed to be a candidate trans-acting factor for X chromosome selection in the mouse because CTCF plays an essential role in controlling the epigenetic switch for X inactivation [102]. It is also involved in the regulation of epigenetics and early embryonic development [37]. Using the transgenic RNAi-based approach, Ctcf-deficient oocytes express reduced levels of CTCF with increased methylation of hitsone H19 and decreased competency of embryonic development [103].

The function of Ctcf as a MEG was identified using transgenic mice expressing Ctcf dsRNA under the control of the Zp3 promoter [103]. Ctcf-deficient oocytes are able to undergo delayed GVBD, and are observed in anaphase or telophase of the first meiosis, which reduces the emission of the first polar body. Ctcf-deficient embryos reach the 2C stage, but are developmentally delayed at the 2C to 4C transition. These data suggest that disruption of Ctcf affects the ZGA at the 2C stage, thus arresting embryos at one cell division. Only 7% of cultured Ctcf-deficient embryos develop to the blastocyst stage and almost all of the Ctcf-deficient embryos arrest at the morula stage with high levels of apoptosis.

Gene-trap mutagenesis

Gene-trap mutagenesis is a technique that randomly generates loss-of-function mutations [104]. Gene-trap is introduced using an insertional gene trap cassette that consists of a reporter gene, a selectable genetic marker, and a poly A site or stop codon. When inserted into an intron of an actively expressed gene, the gene trap vector is transcribed from the endogenous promoter of that gene. A fusion transcript is formed such that the expressed inserted reporter and selectable marker are terminated prematurely at the inserted stop codon. This processed fusion transcript encodes a truncated and non-functional cellular protein [104].

1. Floped (oocyte expressed protein, Ooep)

FLOPED is a key component for SCMC that assembles during oogenesis. The SCMC consists of FLOPED, TLE6, Filia, and Mater and is essential for the first embryonic cell division. The expression of Floped transcripts is first detected at E15.5 and peaks 1 week after birth. Floped transcripts do not appear in other tissues including testis, but rather only in growing oocytes in mouse ovaries. During oocyte maturation and ovulation, Floped transcripts are degraded and are no longer detected by the 2C stage of early embryogenesis. FLOPED protein, however, persists during early embryogenesis up to the blastocyst stage [38].

The Floped gene contains three exons, of which a gene trap vector was inserted between exon1 and exon2. Floped mutant animals express a mutant FLOPED-β-galatosidase fusion protein. Flopedtm/tm mice are viable, survive to adulthood, and appear to be normal. Ovaries in Flopedtm/tm female mice show normal histology with follicles at all developmental stages within the corpora lutea. These results suggest that Flopedtm/tm female mice have normal processes of folliculogenesis and ovulation. Oocytes from Flopedtm/tm female mice are also morphologically indistinguishable from their wild-type counterparts, and a comparable number of normal-appearing GV oocytes are recovered from these animals. In Flopedtm/tm female mice, progression from zygotes to 2C embryos is delayed by 6-8 hours, and blastomeres are cleaved into unequal sizes with demonstrable fragmentation. Additionally, Flopedtm/tm female mice produce no offspring and are sterile [38].

Conclusion

The molecular basis for the processes of oocyte maturation, fertilization, and successful early embryo development are mainly dependent on components that are stored in oocytes and encoded by MEGs. Mouse transgenesis plays an essential role in identifying the genes that are important for normal development in mammals. Using this approach, oocytes or embryos derived from mothers that are homozygous null for a given MEG have disrupted genetic expression of that MEG and provide for analysis of the loss-of-function phenotypes. However, the function of some MEGs cannot be addressed by mouse mutagenesis. The functions of these MEGs are studied using gene knockdown systems. Through current studies that use new molecular biological techniques, the working mechanisms by which MEGs regulate early embryo development have been revealed one at a time. In this review, we have summarized the molecular techniques used for the identification of MEGs (Figure 1), findings of the loss-of-function of those genes, and the resulting phenotypes related to male and female fertility and reproduction.

Figure 1.

Summary of the various technical approaches for identifying maternal effect genes.

Although only a small number of mammalian MEGs have been found to date, we believe that there will be an exponential increase in the discovery of other MEGs. Our recent identification of SEBOX and GAS6 as new candidate MEGs through the knockdown of these genes in vitro has added to the short list of known MEGs (Figure 2). Increasing the amount of evidence regarding the molecular mechanisms of MEGs in the mouse provides a better understanding of the regulation of oocyte maturation, fertilization, and normal early embryonic development in human reproduction.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing arrested embryonic stages after interference of maternal effect gene expression by various gene knockout approaches, including the tissue-specific Cre-loxP system, gene knockdown system, transgenic ribonucleic acid interference, and gene-trap mutagenesis in the mouse. GV, germinal vesicle; MII, metaphase II; PN, pronucleus stage; 2C, 2-cell stage; 4C, 4-cell stage; 8C, 8-cell stage; MO, morula stage; BL, blastocyst stage.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2009-0093821).

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Li L, Zheng P, Dean J. Maternal control of early mouse development. Development. 2010;137:859–870. doi: 10.1242/dev.039487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KH, Kim EY, Lee KA. SEBOX is essential for early embryogenesis at the two-cell stage in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:1192–1201. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH, Kim EY, Kim Y, Kim E, Lee HS, Yoon SY, et al. Gas6 downregulation impaired cytoplasmic maturation and pronuclear formation independent to the MPF activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong ZB, Gold L, Pfeifer KE, Dorward H, Lee E, Bondy CA, et al. Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26:267–268. doi: 10.1038/81547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christians E, Davis AA, Thomas SD, Benjamin IJ. Maternal effect of Hsf1 on reproductive success. Nature. 2000;407:693–694. doi: 10.1038/35037669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell CY, Bestor TH, Ding F, Latham KE, Mertineit C, Trasler JM, et al. Genomic imprinting disrupted by a maternal effect mutation in the Dnmt1 gene. Cell. 2001;104:829–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourc'his D, Xu GL, Lin CS, Bollman B, Bestor TH. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science. 2001;294:2536–2539. doi: 10.1126/science.1065848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leader B, Lim H, Carabatsos MJ, Harrington A, Ecsedy J, Pellman D, et al. Formin-2, polyploidy, hypofertility and positioning of the meiotic spindle in mouse oocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:921–928. doi: 10.1038/ncb880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurtu VE, Verma S, Grossmann AH, Liskay RM, Skarnes WC, Baker SM. Maternal effect for DNA mismatch repair in the mouse. Genetics. 2002;160:271–277. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narducci MG, Fiorenza MT, Kang SM, Bevilacqua A, Di Giacomo M, Remotti D, et al. TCL1 participates in early embryonic development and is overexpressed in human seminomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11712–11717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Ren Y, Wang P, DeMayo FJ, Frail DE, et al. Roles of NPM2 in chromatin and nucleolar organization in oocytes and embryos. Science. 2003;300:633–636. doi: 10.1126/science.1081813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payer B, Saitou M, Barton SC, Thresher R, Dixon JP, Zahn D, et al. Stella is a maternal effect gene required for normal early development in mice. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2110–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu X, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ, Bai Y, Fitzpatrick SL, Matzuk MM. Zygote arrest 1 (Zar1) is a novel maternal-effect gene critical for the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Nat Genet. 2003;33:187–191. doi: 10.1038/ng1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roest HP, Baarends WM, de Wit J, van Klaveren JW, Wassenaar E, Hoogerbrugge JW, et al. The ubiquitin-conjugating DNA repair enzyme HR6A is a maternal factor essential for early embryonic development in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5485–5495. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5485-5495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos SB, Stumpo DJ, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Bock CB, Ribeiro-Neto F, et al. The CCCH tandem zinc-finger protein Zfp36l2 is crucial for female fertility and early embryonic development. Development. 2004;131:4883–4893. doi: 10.1242/dev.01336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekiguchi S, Kwon J, Yoshida E, Hamasaki H, Ichinose S, Hideshima M, et al. Localization of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 in mouse ova and its function in the plasma membrane to block polyspermy. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1722–1729. doi: 10.2352/ajpath.2006.060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng P, Dean J. Role of Filia, a maternal effect gene, in maintaining euploidy during cleavage-stage mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7473–7478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900519106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Carroll D, Erhardt S, Pagani M, Barton SC, Surani MA, Jenuwein T. The polycomb-group gene Ezh2 is required for early mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4330–4336. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4330-4336.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erhardt S, Su IH, Schneider R, Barton S, Bannister AJ, Perez-Burgos L, et al. Consequences of the depletion of zygotic and embryonic enhancer of zeste 2 during preimplantation mouse development. Development. 2003;130:4235–4248. doi: 10.1242/dev.00625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larue L, Ohsugi M, Hirchenhain J, Kemler R. E-cadherin null mutant embryos fail to form a trophectoderm epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8263–8267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Vries WN, Evsikov AV, Haac BE, Fancher KS, Holbrook AE, Kemler R, et al. Maternal beta-catenin and E-cadherin in mouse development. Development. 2004;131:4435–4445. doi: 10.1242/dev.01316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneda M, Okano M, Hata K, Sado T, Tsujimoto N, Li E, et al. Essential role for de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in paternal and maternal imprinting. Nature. 2004;429:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature02633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, et al. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bultman SJ, Gebuhr TC, Pan H, Svoboda P, Schultz RM, Magnuson T. Maternal BRG1 regulates zygotic genome activation in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1744–1754. doi: 10.1101/gad.1435106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murchison EP, Stein P, Xuan Z, Pan H, Zhang MQ, Schultz RM, et al. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21:682–693. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esposito G, Vitale AM, Leijten FP, Strik AM, Koonen-Reemst AM, Yurttas P, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) 6 is essential for oocyte cytoskeletal sheet formation and female fertility. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;273:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukamoto S, Kuma A, Murakami M, Kishi C, Yamamoto A, Mizushima N. Autophagy is essential for preimplantation development of mouse embryos. Science. 2008;321:117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1154822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita S, Horii T, Kimura M, Goto Y, Ochiya T, Hatada I. One Argonaute family member, Eif2c2 (Ago2), is essential for development and appears not to be involved in DNA methylation. Genomics. 2007;89:687–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneda M, Tang F, O'Carroll D, Lao K, Surani MA. Essential role for Argonaute2 protein in mouse oogenesis. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lykke-Andersen K, Gilchrist MJ, Grabarek JB, Das P, Miska E, Zernicka-Goetz M. Maternal Argonaute 2 is essential for early mouse development at the maternal-zygotic transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4383–4392. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres-Padilla ME, Zernicka-Goetz M. Role of TIF1alpha as a modulator of embryonic transcription in the mouse zygote. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:329–338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foygel K, Choi B, Jun S, Leong DE, Lee A, Wong CC, et al. A novel and critical role for Oct4 as a regulator of the maternal-embryonic transition. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J, Zeng F, Schultz RM, Tseng H. Basonuclin: a novel mammalian maternal-effect gene. Development. 2006;133:2053–2062. doi: 10.1242/dev.02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan LB, Pan H, Hannenhalli S, Cheng Y, Ma J, Fedoriw A, et al. Maternal depletion of CTCF reveals multiple functions during oocyte and preimplantation embryo development. Development. 2008;135:2729–2738. doi: 10.1242/dev.024539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Baibakov B, Dean J. A subcortical maternal complex essential for preimplantation mouse embryogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong ZB, Nelson LM. A mouse gene encoding an oocyte antigen associated with autoimmune premature ovarian failure. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3720–3726. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong ZB, Nelson LM, Dean J. Mater encodes a maternal protein in mice with a leucine-rich repeat domain homologous to porcine ribonuclease inhibitor. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s003350010053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMillan DR, Xiao X, Shao L, Graves K, Benjamin IJ. Targeted disruption of heat shock transcription factor 1 abolishes thermotolerance and protection against heat-inducible apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7523–7528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H. DNA methyltransferase is actively retained in the cytoplasm during early development. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:25–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kono T, Obata Y, Yoshimzu T, Nakahara T, Carroll J. Epigenetic modifications during oocyte growth correlates with extended parthenogenetic development in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1996;13:91–94. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis TL, Yang GJ, McCarrey JR, Bartolomei MS. The H19 methylation imprint is erased and re-established differentially on the parental alleles during male germ cell development. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2885–2894. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leader B, Leder P. Formin-2, a novel formin homology protein of the cappuccino subfamily, is highly expressed in the developing and adult central nervous system. Mech Dev. 2000;93:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emmons S, Phan H, Calley J, Chen W, James B, Manseau L. Cappuccino, a Drosophila maternal effect gene required for polarity of the egg and embryo, is related to the vertebrate limb deformity locus. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2482–2494. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.20.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeller R, Haramis AG, Zuniga A, McGuigan C, Dono R, Davidson G, et al. Formin defines a large family of morphoregulatory genes and functions in establishment of the polarising region. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s004410051269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuh M, Ellenberg J. A new model for asymmetric spindle positioning in mouse oocytes. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1986–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker SM, Bronner CE, Zhang L, Plug AW, Robatzek M, Warren G, et al. Male mice defective in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 exhibit abnormal chromosome synapsis in meiosis. Cell. 1995;82:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laine J, Kunstle G, Obata T, Sha M, Noguchi M. The protooncogene TCL1 is an Akt kinase coactivator. Mol Cell. 2000;6:395–407. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narducci MG, Virgilio L, Engiles JB, Buchberg AM, Billips L, Facchiano A, et al. The murine Tcl1 oncogene: embryonic and lymphoid cell expression. Oncogene. 1997;15:919–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowles J, Teasdale RP, James K, Koopman P. Dppa3 is a marker of pluripotency and has a human homologue that is expressed in germ cell tumours. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;101:261–265. doi: 10.1159/000074346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sato M, Kimura T, Kurokawa K, Fujita Y, Abe K, Masuhara M, et al. Identification of PGC7, a new gene expressed specifically in preimplantation embryos and germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;113:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jentsch S, McGrath JP, Varshavsky A. The yeast DNA repair gene RAD6 encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Nature. 1987;329:131–134. doi: 10.1038/329131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai WS, Carballo E, Thorn JM, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to Au-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon J, Kikuchi T, Setsuie R, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, Yoshikawa Y. Characterization of the testis in congenitally ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-1 (Uch-L1) defective (gad) mice. Exp Anim. 2003;52:1–9. doi: 10.1538/expanim.52.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sekiguchi S, Yoshikawa Y, Tanaka S, Kwon J, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of protein gene product 9.5, a ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase, during placental and embryonic development in the mouse. Exp Anim. 2003;52:365–369. doi: 10.1538/expanim.52.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osaka H, Wang YL, Takada K, Takizawa S, Setsuie R, Li H, et al. Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 binds to and stabilizes monoubiquitin in neuron. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1945–1958. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwon J, Wang YL, Setsuie R, Sekiguchi S, Sato Y, Sakurai M, et al. Two closely related ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase isozymes function as reciprocal modulators of germ cell apoptosis in cryptorchid testis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1367–1374. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamazaki K, Wakasugi N, Sakakibara A, Tomita T. Reduced fertility in gracile axonal dystrophy (gad) mice. Jikken Dobutsu. 1988;37:195–199. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.37.2_195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamazaki K, Wakasugi N, Tomita T, Kikuchi T, Mukoyama M, Ando K. Gracile axonal dystrophy (GAD), a new neurological mutant in the mouse. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988;187:209–215. doi: 10.3181/00379727-187-42656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saigoh K, Wang YL, Suh JG, Yamanishi T, Sakai Y, Kiyosawa H, et al. Intragenic deletion in the gene encoding ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase in gad mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:47–51. doi: 10.1038/12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sauer B, Henderson N. Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sewalt RG, van der Vlag J, Gunster MJ, Hamer KM, den Blaauwen JL, Satijn DP, et al. Characterization of interactions between the mammalian polycomb-group proteins Enx1/EZH2 and EED suggests the existence of different mammalian polycomb-group protein complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3586–3595. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vire E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439:871–874. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plath K, Fang J, Mlynarczyk-Evans SK, Cao R, Worringer KA, Wang H, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in X inactivation. Science. 2003;300:131–135. doi: 10.1126/science.1084274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Vries WN, Binns LT, Fancher KS, Dean J, Moore R, Kemler R, et al. Expression of Cre recombinase in mouse oocytes: a means to study maternal effect genes. Genesis. 2000;26:110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yanagisawa Y, Ito E, Yuasa Y, Maruyama K. The human DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B have two types of promoters with different CpG contents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:457–465. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, et al. The human DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: coordinate mRNA expression in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2291–2298. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galetzka D, Weis E, Tralau T, Seidmann L, Haaf T. Sex-specific windows for high mRNA expression of DNA methyltransferases 1 and 3A and methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins 2 and 4 in human fetal gonads. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:233–241. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kingston RE, Narlikar GJ. ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2339–2352. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suh N, Baehner L, Moltzahn F, Melton C, Shenoy A, Chen J, et al. MicroRNA function is globally suppressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Curr Biol. 2010;20:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothnagel JA, Rogers GE. Citrulline in proteins from the enzymatic deimination of arginine residues. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:624–631. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wright PW, Bolling LC, Calvert ME, Sarmento OF, Berkeley EV, Shea MC, et al. ePAD, an oocyte and early embryo-abundant peptidylarginine deiminase-like protein that localizes to egg cytoplasmic sheets. Dev Biol. 2003;256:73–88. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yurttas P, Vitale AM, Fitzhenry RJ, Cohen-Gould L, Wu W, Gossen JA, et al. Role for PADI6 and the cytoplasmic lattices in ribosomal storage in oocytes and translational control in the early mouse embryo. Development. 2008;135:2627–2636. doi: 10.1242/dev.016329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Hatano M, Kobayashi Y, Kabeya Y, Suzuki K, et al. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:657–668. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeRenzo C, Seydoux G. A clean start: degradation of maternal proteins at the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsukamoto S, Kuma A, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Autophagy. 2008;4:1076–1078. doi: 10.4161/auto.7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O'Carroll D, Mecklenbrauker I, Das PP, Santana A, Koenig U, Enright AJ, et al. A Slicer-independent role for Argonaute 2 in hematopoiesis and the microRNA pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1999–2004. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:719–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Le Douarin B, Zechel C, Garnier JM, Lutz Y, Tora L, Pierrat P, et al. The N-terminal part of TIF1, a putative mediator of the ligand-dependent activation function (AF-2) of nuclear receptors, is fused to B-raf in the oncogenic protein T18. EMBO J. 1995;14:2020–2033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takeda J, Seino S, Bell GI. Human Oct3 gene family: cDNA sequences, alternative splicing, gene organization, chromosomal location, and expression at low levels in adult tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4613–4620. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palmieri SL, Peter W, Hess H, Scholer HR. Oct-4 transcription factor is differentially expressed in the mouse embryo during establishment of the first two extraembryonic cell lineages involved in implantation. Dev Biol. 1994;166:259–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yoon SJ, Koo DB, Park JS, Choi KH, Han YM, Lee KA. Role of cytosolic malate dehydrogenase in oocyte maturation and embryo development. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoon SJ, Kim EY, Kim YS, Lee HS, Kim KH, Bae J, et al. Role of Bcl2-like 10 (Bcl2l10) in Regulating Mouse Oocyte Maturation. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:497–506. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee HS, Kim EY, Kim KH, Moon J, Park KS, Kim KS, et al. Obox4 critically regulates cAMP-dependent meiotic arrest and MI-MII transition in oocytes. FASEB J. 2010;24:2314–2324. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee HS, Kim EY, Lee KA. Changes in gene expression associated with oocyte meiosis after Obox4 RNAi. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2011;38:68–74. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2011.38.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim E, Yoon SJ, Kim EY, Kim Y, Lee HS, Kim KH, et al. Function of COP9 signalosome in regulation of mouse oocytes meiosis by regulating MPF activity and securing degradation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee SY, Lee HS, Kim EY, Ko JJ, Yoon TK, Lee WS, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein regulates glucose metabolism and affects cytoplasmic streaming in mouse oocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dean J. Oocyte-specific genes regulate follicle formation, fertility and early mouse development. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;53:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cinquanta M, Rovescalli AC, Kozak CA, Nirenberg M. Mouse Sebox homeobox gene expression in skin, brain, oocytes, and two-cell embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8904–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ohashi K, Nagata K, Toshima J, Nakano T, Arita H, Tsuda H, et al. Stimulation of sky receptor tyrosine kinase by the product of growth arrest-specific gene 6. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22681–22684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Manfioletti G, Brancolini C, Avanzi G, Schneider C. The protein encoded by a growth arrest-specific gene (gas6) is a new member of the vitamin K-dependent proteins related to protein S, a negative coregulator in the blood coagulation cascade. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4976–4985. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lu Q, Gore M, Zhang Q, Camenisch T, Boast S, Casagranda F, et al. Tyro-3 family receptors are essential regulators of mammalian spermatogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:723–728. doi: 10.1038/19554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tian Q, Kopf GS, Brown RS, Tseng H. Function of basonuclin in increasing transcription of the ribosomal RNA genes during mouse oogenesis. Development. 2001;128:407–416. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chao W, Huynh KD, Spencer RJ, Davidow LS, Lee JT. CTCF, a candidate trans-acting factor for X-inactivation choice. Science. 2002;295:345–347. doi: 10.1126/science.1065982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fedoriw AM, Stein P, Svoboda P, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Transgenic RNAi reveals essential function for CTCF in H19 gene imprinting. Science. 2004;303:238–240. doi: 10.1126/science.1090934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stanford WL, Cohn JB, Cordes SP. Gene-trap mutagenesis: past, present and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:756–768. doi: 10.1038/35093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]