Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is expressed in human bladder tumors. A phase II study was conducted to assess the VEGF inhibitor pazopanib in patients with metastatic, urothelial carcinoma. Nineteen patients with one prior systemic therapy were enrolled. No objective responses were observed and median progression-free survival was 1.9 months. The role of anti-VEGF therapies in urothelial carcinoma remains to be determined.

Background

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is produced by bladder cancer cell lines in vitro and expressed in human bladder tumor tissues. Pazopanib is a vascular endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with anti-angiogenesis and anti-tumor activity in several preclinical models. A 2-stage phase II study was conducted to assess the activity and toxicity profile of pazopanib in patients with metastatic, urothelial carcinoma.

Methods

Patients with one prior systemic therapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma were eligible. Patients received pazopanib at a dose of 800 mg orally for a 4-week cycle.

Results

Nineteen patients were enrolled. No grade 4 or 5 events were experienced. Nine patients experienced 11 grade 3 adverse events. Most common toxicities were anemia, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, and fatigue. For stage I, none of the first 16 evaluable patients were deemed a success (complete response or partial response) by the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors criteria during the first four 4-week cycles of treatment. Median progression-free survival was 1.9 months. This met the futility stopping rule of interim analysis, and therefore the trial was recommended to be permanently closed.

Conclusions

Pazopanib did not show significant activity in patients with urothelial carcinoma. The role of anti-VEGF therapies in urothelial carcinoma may need further evaluation in rational combination strategies.

Keywords: Pazopanib, Urothelial cancer, VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Introduction

Urothelial carcinoma is an angiogenesis sensitive disease as shown by preclinical and clinical studies.1-3 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are produced by several bladder cancer cell lines in vitro and are expressed in tumor tissue of patients.4 In addition, preclinical studies have shown that bladder cancer cell lines express VEGF receptors 1 and 2 on the surface membrane.4 Therefore, treatment with a VEGF receptor inhibitor may not only target the endothelial cells in this disease but may also have some direct antitumor activity.

Pazopanib is a potent and selective, orally available, small molecule inhibitor of VEGF receptors 1, 2, and 3, PDGF-α, PDGF-β, and c-kit tyrosine kinases (TKs) that is approved for the treatment of advanced kidney cancer.5 The agent selectively inhibits proliferation of endothelial cells stimulated with VEGF, but not with basic fibroblast growth factor. In nonclinical angiogenesis models, pazopanib inhibited VEGF-dependent angiogenesis in a dose-dependent manner; and in xenograft models, twice daily administration of pazopanib significantly inhibited tumor growth in mice implanted with various types of human tumor cells.6

In view of the role of angiogenesis in urothelial cancer progression and that the positive rate of VEGF gene expression has been shown to significantly increase with the progression of tumor grade and clinical staging, treatment with pazopanib may have an inhibitory effect of tumor growth and induce delayed tumor progression in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer. In this phase II clinical trial, pazopanib was administered to patients who were previously treated with 1 prior chemotherapy regimen for metastatic urothelial cancer. The objectives of this trial were to assess the antitumor activity and toxicity profile of oral pazopanib and to evaluate the pre- and post-treatment changes in angiogenesis-related factors.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium/bladder, with the predominant histologic component being transitional cell carcinoma, were eligible. Prior adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy was permitted, as well as prior palliative radiation to metastatic lesion(s) provided there was at least one measurable or evaluable lesion that had not been radiated. Inclusion criteria included age ≥ 18 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 2; life expectancy ≥ 12 weeks; blood pressure < 140 mm Hg (systolic) < 90 mm Hg (diastolic); measureable disease with at least one lesion with the longest diameter > 1.0 cm; at least 4 weeks elapsed since prior radiation therapy; a maximum of one prior chemotherapy regimen for metastatic disease; and adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. This included absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1500/mm3, platelets ≥ 100,000/mm3, white blood cell count ≥ 3000 cells/mm3, measured creatinine clearance ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, total bilirubin equal to or less than normal institutional limits, prothrombin time (PTT)/international normalized ratio/activated PTT ≤ 1.2 times the upper limit of normal, and aspartate aminotransferase (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase) or alanine aminotransferase (serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase) ≤ 2.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal.

Patients were excluded if they had surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy less than 4 weeks before registration; prior or current treatment with any other investigational agents; history of allergic reactions attributed to compounds of similar chemical or composition to pazopanib; ≥ +1 proteinuria on 2 consecutive dipsticks taken at least 1 week apart; cytochrome P450 enzymes interactive concomitant medications; any condition that impaired the ability to swallow and retain pazopanib tablets; any serious or nonhealing wound, ulcer, or bone fracture; history of abdominal fistula, gastrointestinal perforation, or intra-abdominal abscess within 28 days of registration; any history of cerebrovascular accident within the last 6 months before registration; current use of therapeutic warfarin; history of myocardial complications or venous thrombosis in the 12 weeks before registration; an active second malignancy; pregnant or lactating women, known brain metastases, uncontrolled intercurrent illness that would limit compliance with study requirements; or human immunodeficiency virus positive on combination antiretroviral therapy. Written informed consent approved by the investigator's institutional review board was obtained from all patients.

Dosage

The dosing schedule was once daily oral administration of 800 mg of pazopanib for 28 consecutive days (1 cycle).

Safety and Efficacy Measures

At study entry, history, physical examination, laboratory studies (complete blood count, serum chemistries, liver function tests, and urinalysis), computed tomography scan, chest x-ray, and electrocardiography were performed. Clinical assessments, including a physical examination and adverse event evaluation, were conducted at each follow-up. Adverse events were graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0).

The primary end point of the trial was tumor response. A confirmed tumor response was defined to be a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) (by the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors [RECIST] criteria) documented on 2 consecutive evaluations 8 weeks apart.

Correlative Analyses

Analyses were performed to determine the pharmacodynamic effect of pazopanib on circulating VEGF. Serial sampling of venous blood was obtained at the following time points: cycle 1 (day 1 pre-treatment, day 8 pre-treatment), before each subsequent cycle (pre-treatment), and at the time of progression or end of active treatment. Blood samples were collected in citrated tubes for plasma extraction and processed by centrifugation at 2000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Serum was collected from red top Vacutainer (Burlington, NC) tubes and processed by centrifugation at 2000g at room temperature for 15 minutes. All samples were stored at –80°C until analysis. VEGF concentrations in serum and plasma were measured by ELISA assay (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Tumor Analysis

Whole formalin-fixed paraffin blocks for each patient were obtained. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using CD34 (endothelial cells), VEGF, and hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1a primary antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Considerations

A single-arm, 2-stage phase II clinical trial design was chosen so that at a 10% significance level there was a 91% chance of detecting a tumor response rate of at least 20% (vs. 5%) with pazopanib among patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. During the first stage, if none of the first 16 eligible patients enrolled achieved a PR or CR, then enrollment was terminated and the regimen was considered inactive in this patient population. At the end of the second stage, if at least 4 of the 32 eligible patients enrolled were successes without excessive toxicity, this regimen could be recommended for further testing in this patient population.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, efficacy in tumor response, and safety data. A Kaplan curve was used to summarize duration of response, overall survival, and progression-free survival. The 90% confidence interval (CI) for the true proportion of confirmed tumor responses was constructed using Duffy and Santner's7 approach.

Results

General

During the period of 36 months, 19 patients were enrolled in the study. One patient withdrew consent before beginning treatment; thus, 18 patients were evaluable. The median age was 66 years, with > 89% of patients presenting poorly differentiated bladder cancer (Table 1). The majority of patients had ≥ 2 metastatic sites.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patients Evaluable (N = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | No. | % |

| Age, years | ||

| Median 65.6 | ||

| Range 42-80 | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 | 72.2 |

| Female | 5 | 27.8 |

| Race | ||

| White | 13 | 72.2 |

| Black or African American | 1 | 5.6 |

| Asian | 3 | 16.7 |

| Not reported | 1 | 5.6 |

| Performance Score | ||

| 0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| 1 | 13 | 72.2 |

| 2 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Primary Tumor Site | ||

| Bladder | 16 | 88.9 |

| Urothelial tract | 2 | 11.1 |

| Differentiation | ||

| Well | 1 | 5.6 |

| Poor | 17 | 94.4 |

| Status of Primary Tumor | ||

| Resected with residual | 5 | 27.81 |

| Unresected | 2 | 1.1 |

| Recurrent | 11 | 61.1 |

| No. of Metastatic Sites | ||

| 1 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 2 | 3 | 16.7 |

| 3 | 5 | 27.8 |

| 4 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Previous Systemic Cancer Therapy | ||

| Yes | 18 | 100 |

| Previous Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 5 | 27.8 |

| No | 13 | 72.2 |

Toxicities

Adverse event data were available on 18 patients. The treatment with pazopanib in this patient population was well tolerated overall (Table 2). No grade 4 or 5 events were experienced. Nine patients experienced 11 grade 3 adverse events, of which 7 were deemed at least possibly related to treatment. Most common toxicities were anemia, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, fatigue, and hypertension.

Table 2.

Toxicities

| Adverse Events at Least Possibly Related | Grade |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | 1N | 2N | 3N | |

| Body No. System | ||||

| Hematology | Anemia | 8 | 2 | |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Platelet count decreased | 6 | 2 | ||

| Leukopenia | 8 | |||

| Hemorrhage | Epistaxis | 2 | ||

| Oral hemorrhage | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hematuria | 1 | |||

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 1 | |||

| Urostomy site bleeding | ||||

| Hepatic | Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 3 | 1 | ||

| Bilirubin | 1 | |||

| Metabolic/Laboratory | Hypocalcemia | 1 | ||

| Hypernatremia | 1 | |||

| Ocular/Visual | Vision-photopsia | 1 | ||

| Pain | Abdominal pain | 2 | ||

| Back pain | 1 | 1 | ||

| Myalgia | 1 | |||

| Pharyngolaryngeal pain | 1 | |||

| Stomach pain | ||||

| Pulmonary | Voice alteration | 1 | ||

| Renal/Genitourinary | Creatinine increased | 1 | ||

| Proteinuria | 3 | 2 | ||

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Coagulation | Activated partial thromboplastin time prolonged | 1 | ||

| Constitutional symptoms | Fatigue | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| Weight loss | 1 | |||

| Dermatology/Skin | Alopecia | 1 | ||

| Skin reaction-hand/foot | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rash | 4 | |||

| Skin hypopigmentation | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | Anorexia | 3 | 3 | |

| Constipation | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| Mucositis oral | 5 | 1 | ||

| Nausea | 2 | |||

| Taste | 6 | |||

| Vomiting | ||||

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 3+ adverse events | 7 | 39 |

| Grade 4+ adverse events | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 5+ adverse events | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 3+ heme adverse events | 1 | 6 |

| Grade 4+ heme adverse events | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 3+ non-heme adverse events | 6 | 33 |

| Grade 4+ non-heme adverse events | 0 | 0 |

| Obs | Data Center ID | Cycle | Body System | Toxicity | Grade | Relationship Study Medications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PH1235 | 1 | Dermatology/skin | Skin reaction-hand/foot | 3 | Definite |

| 2 | PH1235 | 2 | Dermatology/skin | Skin reaction-hand/foot | 3 | Definite |

| 3 | PH1270 | 2 | Gastrointestinal | Diarrhea | 3 | Possible |

| 4 | PH1354 | 1 | Pain | Back pain | 3 | Possible |

| 5 | PH1373 | 4 | Constitutional symptoms | Fatigue | 3 | Possible |

| 6 | PH1397 | 2 | Gastrointestinal | Mucositis oral | 3 | Probable |

| 7 | PH1399 | 1 | Cardiovascular | Hypertension | 3 | Probable |

Tumor Responses

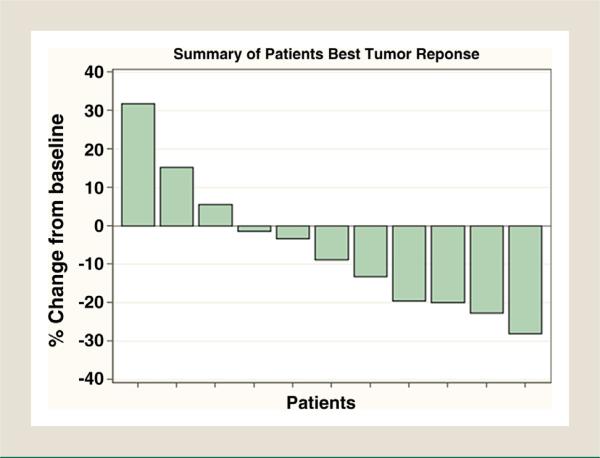

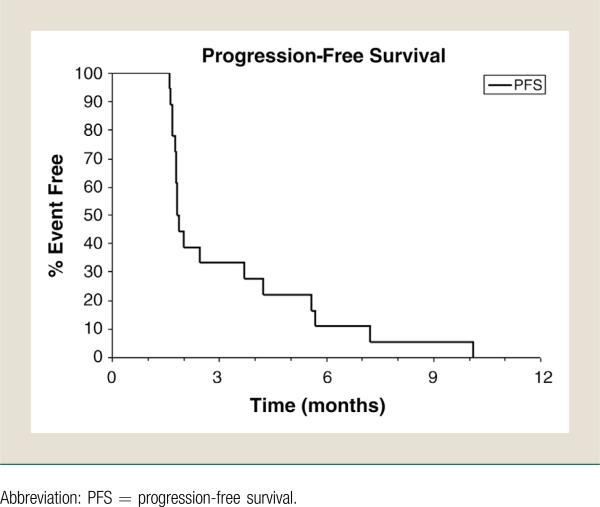

For stage 1, none of the first 16 evaluable patients were deemed a success (CR or PR) by the RECIST criteria during the first four 4-week cycles of treatment (Fig. 1). This met the futility stopping rule of interim analysis; therefore, the trial was recommended to be permanently closed. Although some patients achieved tumor shrinkage as shown in Figure 1, the median progression-free survival was only 1.9 months (Fig. 2). The median follow-up was 3.4 months (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Efficacy: Best Response. The Best Tumor Response of Each Patient is Shown, With 11 of the 18 Patients Shown Having at Least 2 Tumor Measurements. Percent Change From Baseline = (Minimum Sum Tumor Measurement - Baseline Sum Tumor Measurement)/(Baseline Sum Tumor Measurement) * 100. Best Response: 8 With Stable Disease and 10 With Progressive Disease

Figure 2.

Efficacy: Progression-Free Survival of Patients. Median Progression-Free Survival: 1.86 Months (95% CI, 1.77-3.71)

Table 3.

Patient Follow-Up

| Patients Evaluable (N = 18) | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Progression Status | ||

| No progression | 2 | 11.1 |

| Progression | 16 | 88.9 |

| Follow-up Status | ||

| Alive | 12 | 66.7 |

| Dead | 6 | 33.3 |

| Months of Follow-up (Alive Patients) | ||

| Median | 3.4 | |

| Range | 0.0-13.0 | |

| Last Cycle | ||

| Median | 2.0 | |

| Range | 0.0-8.0 | |

| Reason for End of Treatment | ||

| Disease progression | 17 | 94.4 |

| Missing | 1 | 5.6 |

Correlative Studies

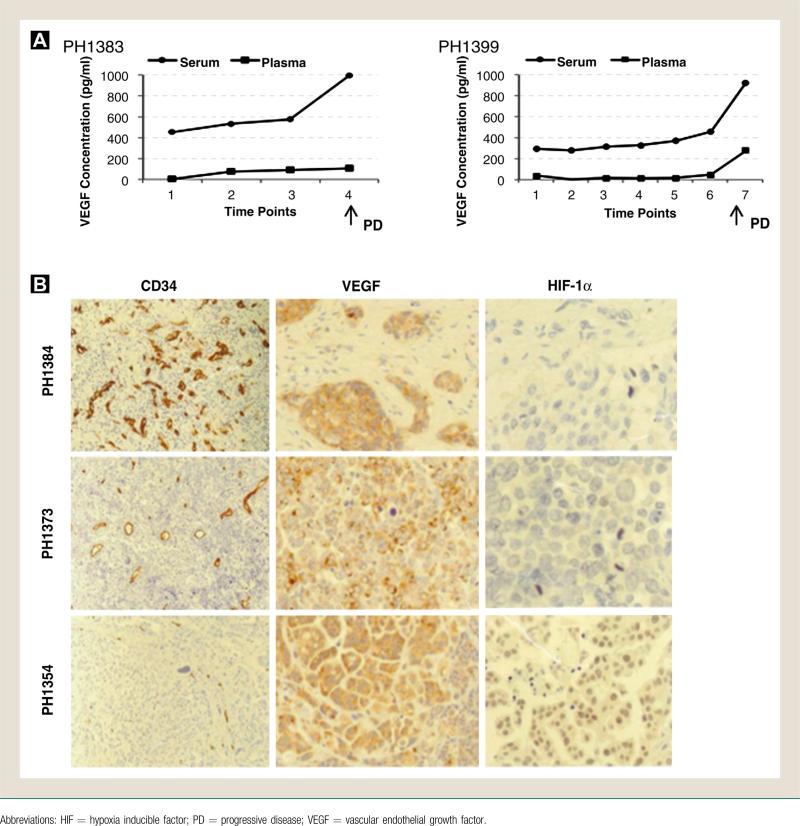

Measurements of VEGF and HIF-1α levels in archived tissues and blood were performed in a limited number of patients. VEGF levels were higher in serum compared with plasma as a reflection of VEGF accumulation in platelets (Fig. 3A). Of note, VEGF serum levels appeared to remain relatively stable during treatment but increased significantly at the time of progression. VEGF staining was consistently positive in the primary cystectomy specimens compared with variable microvessel density (CD34 staining) and HIF-1α expression (Fig. 3B). No association among CD34, VEGF, and HIF-1α expression with time to tumor progression was observed.

Figure 3.

Correlative Studies A, VEGF Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Analysis. Representative Plasma and Serum Levels of VEGF (Picograms/Milliliters) Measured in 2 Patients During the Course of Treatment With Pazopanib at Different Time Points (1 = Baseline, ≥ 2 = Subsequent Cycles). B, Immunohistochemical Analysis. Representative Stainings for CD34, VEGF, and HIF-1αin Archived Tumor Tissues From the Original Cystectomy of 3 Different Patients are Depicted

Discussion

Recurrent urothelial carcinoma remains an orphan disease. The therapeutic options available for patients with metastatic disease are limited to cisplatin-based regimens.8 To date, there is no approved drug/regimen in the second-line setting. Development of novel and effective targeted therapies for urothelial carcinoma represents an unmet need.

The testing of anti-VEGF therapies in urothelial carcinoma has shown mixed results. Single-arm phase II studies with the VEGF-receptor TK inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib have not shown significant clinical benefit.9,10 A recent report by Necchi et al.11 has showed the results of a similar phase II clinical trial with pazopanib in 41 patients with recurrent urothelial carcinoma. Seven patients had a confirmed objective response (17.1%; 95% CI, 7.2-32.1), all of which were PRs. The most frequent treatment-related grade 3 adverse events were hypertension (7%), fatigue (5%), and gastrointestinal and vaginal fistulizations (5%). One patient died as a result of duodenal fistulization that was related to tissue response of bulky tumor masses.

The different results in terms of clinical benefit noticed between the 2 studies may be due to lack of 2-stage design in the study by Necchi and colleagues, consequently the opportunity to treat a larger number of patients and higher chance to observe clinical responses. Necchi et al.11 also used positron emission tomography/computed tomography European criteria to report the responses. We cannot rule out the possibility of differences in the patient populations treated in the two studies. In our study, despite the lack of objective responses and consequently the need to terminate the trial, we observed clinical signs of activity as suggested by the degree of tumor shrinkage in some of the patients treated with pazopanib (Fig. 1). These modest anatomic responses did not have a significant impact on the progression-free survival. The limited number of patients and samples available for correlative studies in the absence of objective responses did not provide a meaningful signal to predict response to pazopanib. Despite the high VEGF levels in both serum and tumor tissues, the intensity of microvessel density, VEGF, or HIF-1α in the original cystectomy specimens correlated with response. Of note, serum VEGF levels had an increase at the time of progression in 2 patients who remained on treatment for 4 and 6 cycles.

Identification of predictors of response remains a major goal in the development of biological therapies for cancer, including urothelial carcinoma. In the study by Necchi et al.,11 preliminary data would suggest a potential role for interleukin (IL)-8. This observation seems to confirm a previous study designed to assess the activity of sunitinib as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer ineligible for cisplatin.12 Low IL-8 baseline levels were significantly associated with increased time to tumor progression. In view of the variability of response to pazopanib monotherapy among patients with kidney cancer, a recent study tested the hypothesis that this variability is dependent in part on germline genetic variants.13 Three polymorphisms in IL-8 and 5 polymorphisms in HIF-1α and VEGF-A showed an association with progression-free survival and response rate, respectively. Germline variants in angiogenesis-related genes, if validated prospectively, may predict the response to anti-angiogenics in patients with cancer, including those with urothelial carcinoma.

Conclusion

The results of our study did not suggest a significant clinical activity of pazopanib, as a single agent, in patients with recurrent urothelial carcinoma. However, tumor angiogenesis remains a valid therapeutic target in urothelial carcinoma. The combination of VEGF inhibitors with chemotherapy represents a valid therapeutic strategy in urothelial cancer.14,15 Clinical trials of pazopanib in combination with vinflunine or paclitaxel are currently ongoing. A recent combination study with cisplatin, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab (CGB) has demonstrated a promising response rate (72%) and median overall survival (19 months).16 The full risk/benefit profile of CGB in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma will be determined by an ongoing phase III intergroup trial. It is conceivable that the identification of potential biomarkers that may predict a response to anti-VEGF therapies in this disease will lead to novel rational combination strategies to be tested in future clinical trials with enriched patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Nadu (Mayo Clinic) for assistance in the statistical analyses, the Pathology Core for the immunohistochemistry studies (Roswell Park Cancer Institute), and all participating patients and their families, investigators, and study staff. This work was supported in part by the Phase 2 Consortium through its N01 contract with the National Cancer Institute (N01-CM62205).

Footnotes

Presented in abstract form at: the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 3-7, 2011, Chicago, IL

Disclosure

Dr. Roberto Pili has been a paid consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and rest of the authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bochner BH, Cote RJ, Weidner N, et al. Angiogenesis in bladder cancer: relationship between microvessel density and tumor prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1603–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.21.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roudnicky F, Poyet C, Wild P, et al. Endocan is upregulated on tumor vessels in invasive bladder cancer where it mediates VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1097–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimada K, Fujii T, Tsujikawa K, et al. ALKBH3 contributes to survival and angio-genesis of human urothelial carcinoma cells through NADPH oxidase and tweak/Fn14/VEGF signals. A-induced angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5247–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu W, Shu X, Hovsepyan H, et al. VEGF receptor expression and signaling in human bladder tumors. Oncogene. 2003;22:3361–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R, Knick VB, Rudolph SK, et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation from mouse to human with pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor with potent antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2012–21. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy DE, Santner TJ. Confidence intervals for a binomial parameter based on multistage tests. Biometrics. 1987;43:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonpavde G, Sternberg CN, Rosenberg JE, et al. Second-line systemic therapy and emerging drugs for metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:861–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreicer R, Li H, Stein M, et al. Phase 2 trial of sorafenib in patients with advanced urothelial cancer: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Cancer. 2009;115:4090–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher DJ, Milowsky MI, Gerst SR, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1373–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Necchi A, Mariani L, Zaffaroni N, et al. Pazopanib in advanced and platinum-resistant urothelial cancer:anopen-label, singlegroup, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:810–6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellmunt J, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Prior C, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib as first-line treatment of urothelial cancer patients ineligible to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy: baseline interleukin-8 and tumor contrast-enhancement as potential predictive factors of activity. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2646–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu CF, Bing NX, Ball HA, et al. Pazopanib efficacy in renal cell carcinoma: evidence for predictive genetic markers in angiogenesis-related and exposure-related genes. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2557–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonpavde G, Jian W, Liu H, et al. Sunitinib malate is active against human urothelial carcinoma and enhances the activity of cisplatin in a preclinical model. Urol Oncol. 2009;27:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choueiri TK, Ross RW, Jacobus S, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial of docetaxel plus vandetanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in platinum-pretreated metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:507–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn NM, Stadler WM, Zon RT, et al. Phase II trial of cisplatin, gemcitabine and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Hoosier Oncology Group GU 04-75. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1525–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]