Abstract

IGF-I receptor signaling contributes to the development of endometrial hyperplasia, the precursor to endometrioid-type endometrial carcinoma, in humans and in rodent models. This pathway is under both positive and negative regulation, including S6K phosphorylation of IRS-1 at serine (636/639), which occurs downstream of mTOR activation to inhibit this adapter protein. We observed activation of mTOR with a high frequency in human endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, but an absence of IRS-1 phosphorylation, despite high levels of activated S6K. To explore when during disease progression mTOR activation and loss of negative feedback to IRS-1 occurred, we utilized the Eker rat (Tsc2Ek/+) model, where endometrial hyperplasia develops as a result of loss of Tsc2, a “gatekeeper” for mTOR. We observed mTOR activation early in progression in hyperplasias and in some histologically normal epithelial cells, suggesting that event(s) in addition to loss of Tsc2 were required for progression to hyperplasia. In contrast, while IRS-1 S636/639 phosphorylation was observed in normal epithelium, it was absent from all hyperplasias, indicating loss of IRS-1 inhibition by S6K occurred during progression to hyperplasia. Treatment with an mTOR inhibitor (WAY-129327) significantly decreased hyperplasia incidence and proliferative indices. Since progression from normal epithelium to carcinoma proceeds via endometrial hyperplasia, these data suggest a progression sequence where activation of mTOR is followed by loss of negative feedback to IRS-1 during the initial stages of development of this disease.

Keywords: Endometrial Hyperplasia, Endometrial Cancer, IRS-1, mTOR, WAY-129327, rat

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecological malignancy with 41,100 new cases and 7,470 deaths predicted to occur in the U.S in 2008 (1). The progression of the normal endometrium to Type I (endometrioid) endometrial adenocarcinoma (EC) involves an intermediary state of abnormal proliferation, complex atypical hyperplasia (CAH) (2). Numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that obesity has a strong association to the development of EC (3, 4). While an average woman has a 3% lifetime risk of EC, obese women have a 9–10% lifetime risk (5). Obesity is associated with the development of insulin resistance and compensatory chronic hyperinsulinemia (6). Increased serum insulin levels lead to reduced hepatic synthesis and blood levels of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP’s) and increased bioavailability of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I). Hyperinsulinemia is proposed to increase insulin/IGF signaling in peripheral tissues such as the endometrium of obese women to promote tumorigenesis (6).

The effect of IGF-I is mediated primarily by activation of the IGF-I receptor (IGF-IR), a tyrosine kinase receptor expressed in endometrial stromal and epithelial cells that signals via activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (7). Ligand activation of IGF-IR induces a phosphorylation cascade of the downstream components including Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 and 2 (IRS-1 and IRS-2), Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) to promote cell proliferation and protein translation (8, 9). Canonical IRS signaling is defined by the binding of IRS-1 or IRS-2, via the conserved pleckstrin homology (PH) and phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains, to ligand phosphorylated IGF-IR (10). The IRS-1 and IRS-2 adaptor proteins are major substrates of the IGF-IR(11), and signaling via IRS-1/2 leads to activation of phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase (PI3K) and Akt. Akt in turn signals to other proteins in the PI3K pathway, including tuberin, the protein product of the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) tumor suppressor gene (9). The TSC tumor suppressor comprised of tuberin and hamartin, functions to inhibit activation of mTOR, a serine/threonine protein kinase that acts as an amino acid and ATP sensor to control nutrient availability and cell growth (12). mTOR is part of two distinct multi-protein complexes, TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and 2 (TORC2). TORC1 is a central controller of cell growth while TORC2 signals to the actin cytoskeleton to determine cell shape and polarity (13). The TORC1 mTOR complex is sensitive to rapamycin, which directly inhibits mTORC1 activity by binding of FKBP12-rapamycin to TOR exclusively in TORC1 (14) . Phosphorylation of TSC2 by Akt inactivates the TSC tumor suppressor and relieves repression of mTOR. Activated mTOR then signals via mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation of p70 S6 Kinase (S6K) and 4EBP1, which in turn activate downstream effectors such as the S6 ribosomal protein (S6) to promote protein transcription, translation, ribosome biogenesis and metabolism (12, 13, 15).

IRS-1 and IRS-2 have similar molecular structures, tissue distribution and ligand stimulation, as well as complementary function. IRS-1 and IRS-2 share significant structural homology, with a highly conserved NH-2 terminus with over 20 common tyrosine phosphorylation motifs and more than 20 serine phosphorylation motifs in the COOH-terminal that bind many of the same signaling molecules (10). Tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of IRS-1/2 positively and negatively regulate IGF-IR signaling, respectively (16–18). IRS-1/2 contain multiple tyrosine phosphorylation motifs that serve as docking sites for SH2 domain containing proteins, such as the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K. Serine/threonine phosphorylation motifs cause dissociation of IRS-1/2 from the IGF-IR and PI3K thereby inhibiting IGF-IR signal transduction (16–19). In particular, S6K phosphorylates multiple serine residues of IRS-1/2 resulting in inhibition of IRS activity and promoting proteosomal degradation. Specifically, serine 636/639 of IRS-1 lies close to the Y632 MPM motif implicated in PI3K binding to IRS-1 upon insulin stimulation. Phosphorylation of serine 636/639 by S6K prevents IRS-1 association with IR/IGF-IR and promotes ubiquitin-proteasome mediated degradation of IRS-1 (20). This S6K–dependent negative feedback inhibition of IRS-1 attenuates IGF-IR/Akt signaling in normal insulin-responsive cells (16, 18, 21–24). A proposed mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic tissues such as white adipose tissue (WAT), liver and skeletal muscle of obese individuals is increased negative feedback to IRS-1 (25). Therefore, in the scenario of insulin-resistance, increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 leads to IRS-1 dissociation from the IGF-IR, thereby preventing insulin signaling through the IGF-IR. S6K–dependent negative feedback inhibition to IRS-1 has been studied primarily in metabolic tissues but has not been well-characterized in cancer, particularly those cancers associated with obesity. Here we present the first report of loss of negative feedback inhibition to IRS-1 during progression of hyperplasia and carcinoma with concomitant activation of mTOR.

We observed in the Eker (Tsc2Ek/+) rat model that endometrial hyperplasia associated with activated mTOR signaling occurred in 100% of aged females. Hyperplasias with activated mTOR signaling exhibited loss of inhibitory IRS-1 phosphorylation, whereas histologically normal appearing endometrial glands with mTOR activation exhibited inhibitory S636/639 phosphorylation. Similar data were obtained in human endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, which also exhibited activation of mTOR and loss of inhibitory IRS-1 phosphorylation. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of mTOR signaling in preclinical studies with the rapamycin analogue WAY-129327(26) completely abrogated mTOR signaling and significantly decreased the proliferative index and incidence of endometrial hyperplasias, confirming the dependence on mTOR signaling for development and growth of these lesions.

Materials and Methods

Endometrial Tissue Samples

For Western blot analysis, endometrioid endometrial carcinomas (n=22) from hysterectomy surgical specimens were flash frozen and stored at −80°C. For immunohistochemistry, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections of endometrial complex hyperplasia with atypia (CAH, n=28) and endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 1 (EEC grade 1, n=11) were derived from hysterectomy surgical specimens submitted to the Department of Pathology, MDACC. H&E-stained slides were microscopically evaluated by a gynecological pathologist (R.R.B.) to confirm the diagnosis.

Animals

The care and handling of rats were in accord with National Institutes of Health guidelines and Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facilities. All protocols involving the use of these animals were approved by the M.D. Anderson Animal Care and Use Committee. 15 month old Eker (Tsc-2Ek/+) rats received i.p. injections of either 10 µg (0.5mg/kg) of WAY-129327 in 50µl of TPE (5% Tween 80, 5% PEG-400, and 4% EtOH) per rat per day (WAY-129327 treated; n=8) or 50µl of TPE (vehicle control; n=11) for 2 weeks. Animals were euthanized and right and left uterine horns, ovaries and vagina were FFPE for light microscopic examination (n=19). H&E-stained slides of left and right uterine horns collected from all animals were microscopically evaluated for the presence of endometrial hyperplastic lesions. Microscopic criteria for identifying rat endometrial hyperplasia have been previously published by our group (27).

Protein isolation and Western blot analysis

To prepare lysates, a small portion (0.5 cm3) of tumor was isolated and crushed with a mortar and pestle over dry ice and the resulting pulverized tissues were collected with liquid nitrogen and transferred into a microcentrifuge tube. Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (0.5–1.0 mL; 1% NP40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 0.01mol/L NaPO4, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 200 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 mmol/L activated sodium orthovanadate, and 1X Roche complete protease inhibitor) was added and samples were rotated at 4°C for 2 h. After rotations, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C for future analysis. Lysate protein concentrations were determined with BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

Samples of protein from each sample (30µg) were size separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred overnight at 4°C onto polyvinylidene diflouride membranes (Pierce Biotechnology). Membranes were blocked in a TBST (TBS plus 0.05% Tween 20) + 5% nonfat milk solution for 1h. Membranes were incubated in a primary antibody solution for 2h at room temperature with varying antibody (1:500−1:2,000) and milk (3–5%) concentrations. For both Western analysis and immunohistochemistry, primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling for IRS-1 (#2390), phosphorylated (serine 636/639) IRS-1 (#2388), phosphorylated (serine 235/236) S6 ribosomal protein (#2211) and S6 ribosomal protein (#2317). Primary antibody for GAPDH was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (#sc-25778). Membranes were then washed 3X with TBST solution for 10 min each and then incubated for 1 h with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature. Membranes were washed with the same procedure as previously mentioned and visualized with LumiGLO chemiluminescent reagents (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) or the ECL + kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for more sensitive detection. Membrane immunoreactivity was detected by X-ray film (BioMax, Eastman Kodak). In our hands, the antibody to IRS-2 was useful in immunohistochemistry. However, for Western blots this same antibody resulted in not clearly distinguishable bands, therefore we believe that this antibody is not ideal for Western analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

FFPE tissue sections were deparaffinized and endogenous peroxidases were quenched by incubation in 1% H2O2. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave in 10mmol/liter citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Slides were incubated with primary antibody (1:50) in PBS containing 10% normal goat or horse serum overnight at 4°C. Primary antibody for Ki-67 (#M7248) was purchased from DAKO North America, Inc., Carpenteria, CA. Primary antibody for Tunel (#QIA33) was purchased from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA. A biotin-labeled secondary antibody was conjugated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Sections were stained using avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex from the DAKO Cytomation LSAB2 System (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) reagent plus chromagen (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA) was incubated with sections for up to 30 minutes. Sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Controls that lacked primary antibody were incubated in 1X PBS with 10% goat serum in each experiment. Immunostained sections were examined by light microscopy by two investigators (A.S.M. and R.R.B), one of whom is a gynecologic pathologist (R.R.B.), and scored semiquantitatively according to the intensity of staining on a scale of 0 (no staining) to 3+ (strong staining). Tissues with 2+ or 3+ staining in greater than 10% of cells were considered positive for protein expression. Ki67 and Tunel labeling indices were scored by assessing the percentage of positive cells per 100 epithelial cells evaluated for vehicle and WAY-129327 treated rats.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in means were calculated by unpaired Student’s t-tests, ANOVA or nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Chi–square test (χ2) was used to evaluate the frequency of immunostaining by group. Any correlations were evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis and confirmed by Spearman's and Kendal's tests. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

IRS-1 and IRS-2 expression in human endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma

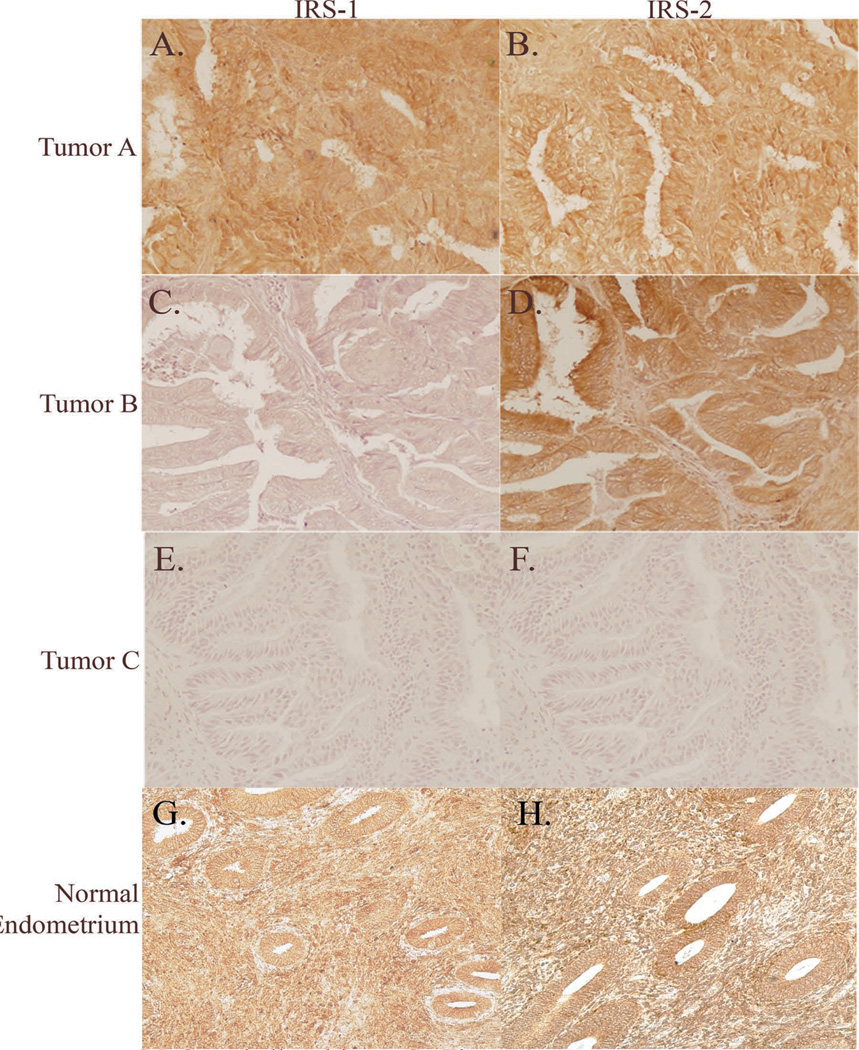

The development of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer are linked to estrogen exposure (28), and we previously reported that neonatal exposure to a synthetic estrogen, DES resulted in IRS-1 overexpression and increased susceptibility to develop endometrial hyperplasias in the rat endometrium (27). To determine if IRS-1/2 were aberrantly expressed in the human disease, we examined expression of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in normal endometrium (n=6), endometrial CAH (n=28) and grade 1 EC (n=11). In the normal endometrium there is abundant expression of IRS-1 (5 out of 6 biopsies evaluated) and IRS-2 (6 out of 6 biopsies evaluated) in both the endometrial stromal cells and glandular epithelial cells (Figure 1G and H). For endometrial CAH and EC, the majority of the cases were clearly positive for IRS-1 and IRS-2 (25/39 positive for IRS-1; 33/39 positive for IRS-2; Figure 1). Importantly IRS-1 and/or IRS-2 were expressed in 25/28 CAH and 10/11 ECs, consistent with a molecular mechanism of endometrial proliferation involving dysregulation of the IGF-IR/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in the majority of tumors. Therefore, for subsequent studies we focused on CAH and grade 1 EC cases that had positive expression of IRS-1 and/or IRS-2.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in normal proliferative phase endometrium and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas from three different patients. Tumor A, positive for both IRS-1 and IRS-2 (A and B). Tumor B, negative for IRS-1 and positive for IRS-2 (C and D). Tumor C, negative for both IRS-1 and IRS-2 (E and F). Normal endometrium (G and H), positive for both IRS-1 and IRS-2. Original magnification 200X.

Loss of inhibitory serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 is associated with progression to hyperplasia

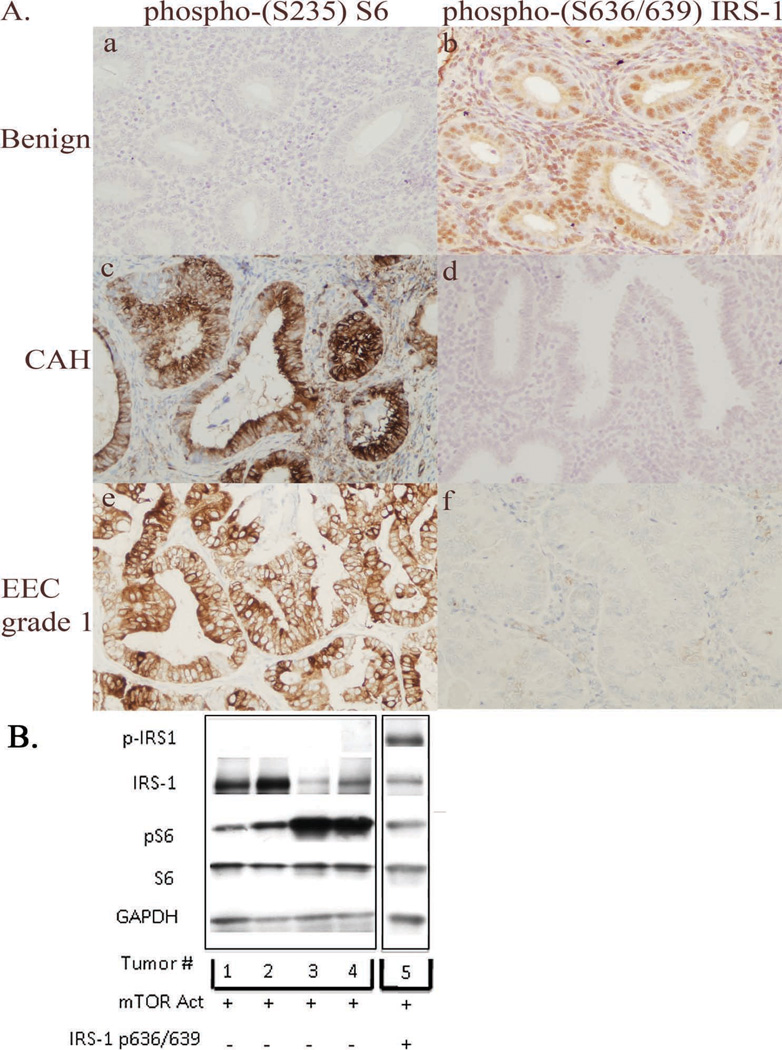

In normal tissues, as a negative feedback mechanism to insulin/IGF stimulation, IRS-1/2 is phosphorylated on multiple serine/threonine residues, for example via S6K phosphorylation at S636/639, promoting its degradation (23). As shown in Figure 2A and Table 1, immunohistochemical expression of serine phosphorylated IRS-1 was high (3+) in the normal endometrial epithelium and stroma. In contrast, serine phosphorylated IRS-1 was absent in the majority of endometrial CAH and EC (Figure 2A (d and f)), despite the fact that these lesions had activated mTOR (Figure 2A (c and e)), demonstrating that activation of mTOR signaling and loss of inhibitory IRS-1 phosphorylation were negatively correlated (p<0.025; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Activation of mTOR signaling (increased phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein) and loss of inhibition of IRS-1 in human endometrial carcinomas. (A) Immunohistochemistry of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (a, c and e) and serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (b, d and f) in normal human endometrium (Benign), CAH, and grade 1 endometrial endometrioid carcinoma (EEC grade 1). Normal endometrium had high expression of phosphorylated (S636/639) IRS-1, with absent expression of phosphorylated (S235) S6. These expression patterns were altered in both CAH and EEC. (B) Western blot analysis of expression of IRS-1, and S6 ribosomal protein and phosphorylation of (S636/639) of IRS-1 and (S235) of S6 in five different grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma lysates. The Western shows 1 tumor expressing phosphorylated (S636/639) IRS-1 and 4 different tumors with absent expression of phosphorylated (S636/639) IRS-1. All 5 tumors shown have high expression of phosphorylated (S235) S6. Original magnification 200X.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical expression of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein and serine phosphorylated IRS-1 in normal proliferative endometrium, endometrial CAH and endometrial endometrioid carcinoma, grade 1. All of these tissues expressed IRS-1 and/or IRS-2. Results are expressed as the number of cases with 2+ or 3+ immunohistochemical expression (n; %). Correlation between expression of phospho-(S235) S6 and phospho-(S636/639) IRS-1 was determined by Pearson’s correlation (p<0.025). * Statistically significant as compared to normal endometrium at the p<0.001 level by χ2-analysis.

| Group | Phospho-(S235) S6 | Phospho-(S636/639) IRS-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=6) | 1 (17%) | 6 (100%) |

| CAH (n=25) | 24 (96%)* | 5 (20%) |

| EEC Grade 1 (n=10) | 9 (90%)* | 2 (18%) |

statistically significant as compared to normal endometrium at the p<0.001 level by x2-analysis.

Western analysis confirmed immunohistochemistry findings and demonstrated an absence of IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in the majority of EC (Figure 2B). Of 20 tumors evaluated by Western, 9/20 tumors had detectable expression of IRS-1. IRS-2 expression was not evaluated as the antibody to IRS-2 used for immunohistochemistry was unsuitable for Western analysis. While only 2/20 tumors exhibited phosphorylation of IRS-1 at S636/639, 18/20 tumors exhibited phospho-(S235) S6 indicative of mTOR activation, and consistent with the high frequency of PI3K activation that is a hallmark of this disease (29). Therefore, despite activation of mTOR signaling in 18 of 20 tumors examined by Western analysis, IRS-1 was phosphorylated at S636/639 in only 2/9 IRS-1 expressing tumors, or 10% of all tumors examined, consistent with what was observed in CAH and EC by immunohistochemistry.

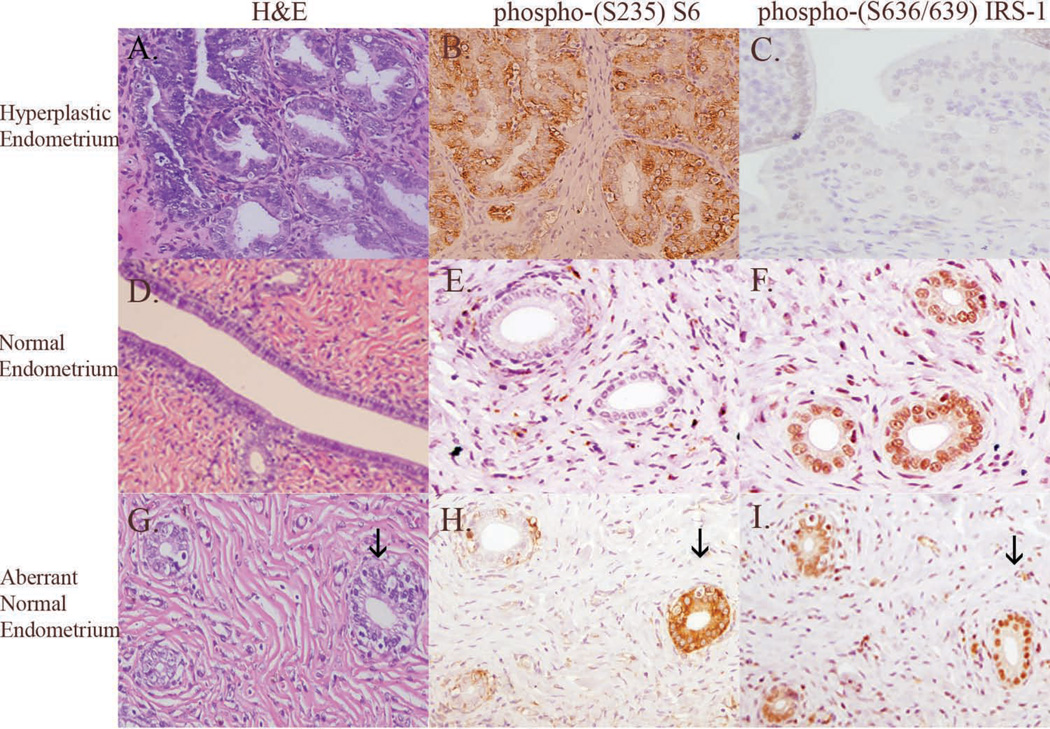

TSC2 is a gatekeeper for mTOR activity, and expression of this tumor suppressor is lost in a significant proportion of EC (13%), identifying loss of TSC2 as a mechanism for mTOR activation in this malignancy (15, 30). Eker (Tsc2Ek/+) rats carry a germline defect in the Tsc2 gene and are susceptible to the development of carcinomas of the kidney and leiomyomas of the reproductive tract (31). To determine if these animals also developed spontaneous endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma, we examined uteri of aged (16 month) females and observed that 100% of these animals had histologically detectable endometrial hyperplasia. Endometrial hyperplasia that developed in female Eker rats was characterized by glandular epithelium with papillary-shaped projections, nuclear stratification, and nuclear enlargement. There was also the presence of glandular proliferation and crowding, similar to that seen in human endometrial complex hyperplasia (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Rat endometrial hyperplasia (A) has increased glandular crowding, increased glandular size, increased glandular complexity, and increased epithelial nuclear atypia compared to normal rat endometrial epithelium (D). Similar to humans, rat endometrial hyperplasia has high immunohistochemical expression of phosphorylated (S235) S6 (B) compared to normal endometrium (E). Similar to humans, rat endometrial hyperplasia has absent immunohistochemical expression of phosphorylated (S636/639) IRS-1 (C), while expression is retained in normal endometrium (F). The majority (94%) of normal endometrial epithelium do not express phospho-(S235) S6 (H) and retain negative feedback to IRS-1 (I). Very few (6%) of “normal” appearing glands (indicated by the arrow; ↓) express phospho-(S235) S6 (H) and retain phospho-(S636/639) (I) suggesting that these glands are “pre-neoplastic”. Data shown in (H and I) suggest that activation of mTOR signaling precedes the loss of negative feedback to IRS-1 in the progression to endometrial hyperplasia. Original magnification 200X.

To determine if similar to human endometrial hyperplasia the development of endometrial hyperplasia in the Eker rat model was associated with activation of mTOR signaling, we evaluated S6 phosphorylation in these lesions by immunohistochemistry. The majority of microscopically normal endometrial glands adjacent to foci of endometrial hyperplasia did not express phosphorylated S6 (Figure 3E), and all exhibited strong immunoreactivity to phosphorylated S636/639 of IRS-1 (Figure 3F). The absence of S6 phosphorylation and the presence of IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in the majority of histologically normal appearing endometrial glands from these rats indicated that the mTOR signaling pathway was not constitutively activated in Tsc2+/- animals and inhibition of the IGF-IR pathway via IRS-1 serine phosphorylation was intact. Similar to what was observed in human endometrial lesions, we found that 90% of individual foci of endometrial hyperplasia that developed in Eker rats showed strong (3+) phosphorylated S6 (Figure 3B) staining and concomitant absent expression of serine phosphorylated IRS-1 (Figure 3C). Histologically normal glands were evaluated for expression of phosphorylated S6 and IRS-1 (n=11 rats; n=844 normal glands). Interestingly, while all of the histologically normal appearing glands exhibited inhibitory IRS-1 phosphorylation at S636/639, occasionally histologically “normal” glands (Figure 3G) were positive for phosphorylated S6 (Figure 3H), with phospho-S6 positivity observed in 51/844 (6%) of histologically “normal” glands. This suggests that activation of mTOR preceds loss of inhibitory IRS-1 phosphorylation, and that loss of IRS-1 inhibition, which was negatively correlated with phospho-S6 positivity in CAH and EC in the human disease, was associated with progression to hyperplasia in this rat model as well.

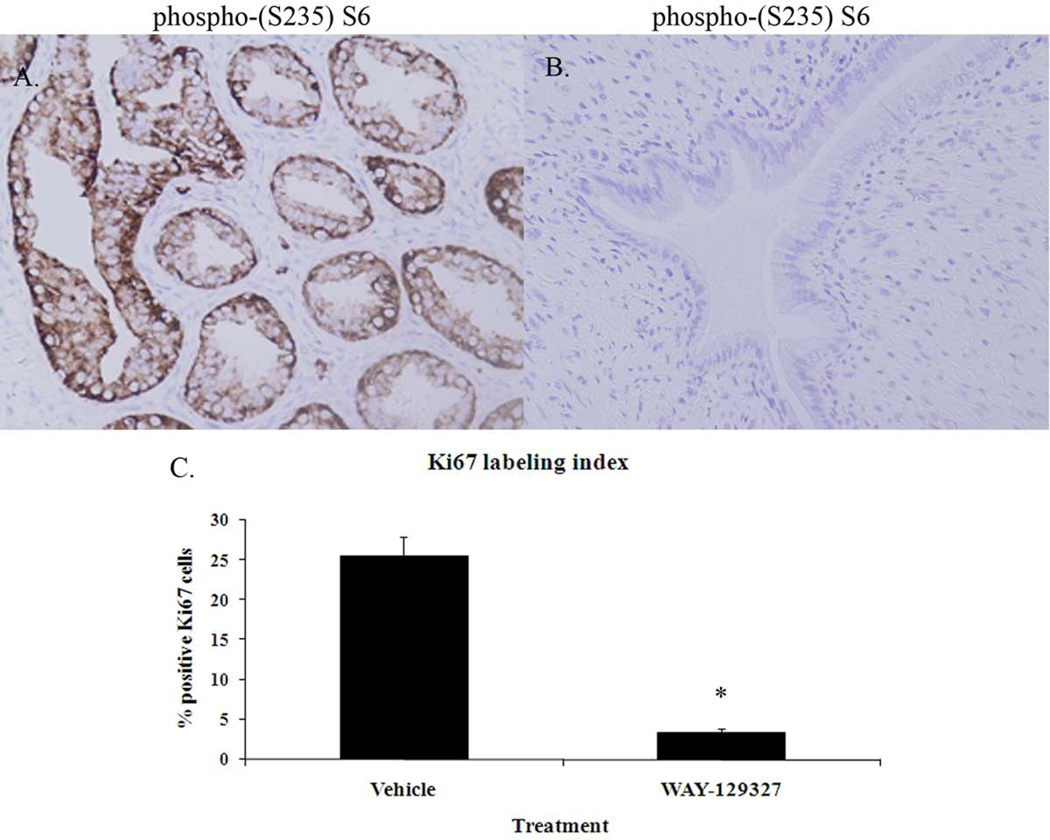

Endometrial hyperplasias are dependent on mTOR signaling for growth

To determine whether mTOR activation directly contributes to the development of endometrial hyperplasia we conducted a series of experiments using an mTORC1 inhibitor, the rapamycin analogue (WAY-129327) (14, 26). Endometrial hyperplasia incidence, proliferation and apoptotic indices, expression of IRS-1 and IRS-2, and mTOR signaling pathway components were evaluated in 15-month old Eker rats following a 2-week treatment with either vehicle or WAY-129327. In the vehicle-treated rats (n=11), endometrial hyperplasias were typically multifocal, with the majority of uterine cross sections examined displaying foci of hyperplasia (54 hyperplastic foci/89 uterine cross sections; 61%) (Table 2). In approximately half of the vehicle-treated rats (6/11), endometrial hyperplasia was more diffuse, with 50% or more of the uterine cross sections from these 6 rats displaying involvement. All hyperplastic lesions in the vehicle-treated rat expressed either IRS-1 and/or IRS-2. In 50/54 hyperplastic lesions from the vehicletreated rats, there was a significant correlation (p<0.001) of high expression of phosphorylated S6 and absent expression of IRS-1 serine phosphorylation (Table 3). As shown in Table 2, the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia was significantly decreased (p<0.001) from 100% in vehicle-treated rats to 50% in WAY-129327-treated rats, with the number of hyperplastic foci decreasing to 6 hyperplastic foci/90 uterine cross sections (7%), with none of the uteri from WAY-129327-treated rats exhibiting diffuse endometrial hyperplasia. Importantly, while 100% of endometrial hyperplasias in vehicle-treated animals exhibited strong phosphorylated S6 expression (Figure 4A), none of the uteri from rats treated with WAY-129327 expressed phosphorylated S6 in the endometrium (Table 3, Figure 4B). Furthermore, in WAY-129327-treated rats, endometrial epithelial proliferation as assessed by the immunohistochemical expression of Ki-67 nuclear antigen was significantly decreased compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 4C). Endometrial apoptotic indices as measured by TUNEL were low in both vehicle and WAY-129327-treated rats (data not shown). Thus, inhibition of mTOR signaling by WAY-129327 resulted in a significant reduction in endometrial hyperplasia incidence and decreased proliferative indices.

Table 2.

Endometrial hyperplasia incidence and immunohistochemical expression of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein and serine phosphorylated IRS-1 in vehicle and WAY-129327-treated Eker (Tsc2+/−) rat endometrium. All rat endometrial sections expressed IRS-1 and/or IRS-2. *, statistical significance was evaluated between the vehicle and WAY-129327-treated groups by χ2 analysis.

| Treatment | # of hyperplastic foci/# uterine cross sections |

% hyperplastic foci (+) for phospho-(S235) S6 |

% hyperplastic foci (+) for phospho-(S636/639) IRS-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle 1 | 2/2 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 2 | 1/1 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 3 | 1/8 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 4 | 7/10 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 5 | 6/12 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 6 | 5/6 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 7 | 3/12 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 8 | 8/9 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 9 | 3/10 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 10 | 8/9 | 100% | 0% |

| Vehicle 11 | 10/10 | 100% | 0% |

| Total | 54/89 (61%) | ||

| WAY-129327 | 1/8 | 0% | 0% |

| WAY-129327 | 1/11 | 0% | 0% |

| WAY-129327 | 1/10 | 0% | 0% |

| WAY-129327 | 0/15 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| WAY-129327 | 0/11 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| WAY-129327 | 0/11 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| WAY-129327 | 0/13 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| WAY-129327 | 3/11 | 0% | 30% |

| Total | 6/90 (7%) | ||

| p-value* | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

statistical significance was evaluated between the vehicle and WAY-129327-treated groups by χ2 analysis.

Not applicable due to lack of endometrial hyperplasia.

Table 3.

Association of strong immunohistochemical expression of phosphorylated S6 with absent expression of serine phosphorylated IRS-1 in hyperplastic Eker (Tsc2+/−) rat endometrium. In hyperplastic foci, strong expression of phosphorylated S6 is significantly associated with absent expression of serine phosphorylated IRS-1.* Correlation between phospho-S6 expression and phospho-(S636/639) expression was evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. *, statistically significant at the p<0.001 level.

| Rat | # of hyperplastic foci with strong phospho-S6 expression and absent phospho-IRS-1 expression/total # hyperplastic foci |

|---|---|

| Vehicle 1 | 2/2 |

| Vehicle 2 | 1/1 |

| Vehicle 3 | 1/1 |

| Vehicle 4 | 6/7 |

| Vehicle 5 | 6/6 |

| Vehicle 6 | 4/5 |

| Vehicle 7 | 3/3 |

| Vehicle 8 | 6/8 |

| Vehicle 9 | 3/3 |

| Vehicle 10 | 8/8 |

| Vehicle 11 | 10/10 |

| Total | 50/54 (93%)* |

statistically significant at the p<0.001 level.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated (S235) S6 ribosomal protein and quantitation of Ki67 labeling indices in vehicle and WAY-129327 treated Eker (Tsc2+/−) rats. WAY-129327 treatment significantly decreased endometrial phosphorylated (S235) S6 immunoreactivity (B) compared to vehicle-treated controls (A).

Immunohistochemistry 200X. WAY-129327 treatment also significantly reduced the endometrial epithelial Ki67 labeling index (C). Cell proliferation was scored by calculating the percentage of Ki67 positive endometrial epithelial cells per 100 epithelial cells for endometrial hyperplastic lesions from vehicle-treated controls (n=54 lesions) and from hyperplastic lesions in the WAY-129327-treated rats (n=6 lesions). Original magnification 200X. Values are the mean ± S.E. *significant at the p < 0.05 level

Discussion

Loss of growth inhibition via receptor tyrosine kinase (IGF-IR) and PI3K activation appears to be an important theme in endometrial cancer pathobiology. PTEN phosphatase negatively regulates IGF-I signaling by dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2, thereby preventing activation of Akt (32). PTEN activity is decreased in 55% of endometrial CAH and up to 83% of EC (33). In a recent study our group identified loss of expression or function of LKB1 and TSC2 in ECs that showed frequent activation of mTOR signaling (30). Our group has shown that for human endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 EC, IGF-IR activation and Akt signaling are critical events (34). We and others have also shown that a large percentage of ECs have defects in PTEN, TSC2, and LKB1 tumor suppressors and a high frequency of activating mutations in PIK3CA (30, 35, 36). These endometrial signaling pathways are also important in rodent models of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, as mice with defects in PTEN (37) and LKB1 (35) exhibit these pathologies. We previously reported that female rats exposed neonatally to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a xenoestrogen, develop endometrial hyperplasia in 60% of exposed animals by 5 months of age (27). We found that dysregulation in IGF-IR signaling pathway components, including activation of AKT and IRS-1, occurs in the hyperplastic lesions that developed in neonatal DES-exposed rats (27). It is therefore clear that IGF-IR signaling is an important event in the majority of ECs. Interestingly, in the present study, we found a small number of EC cases in which both IRS-1 and IRS-2 were lost, implying that pathways independent of IGF-IR may be important in a subset of ECs. It is well known that unopposed estrogen is a risk factor for EC, and that the ERα and IGF-IR pathways crosstalk (28). In addition to crosstalk with IGF-IR, the ERα is also known to crosstalk with the MAPK pathway and this may constitute an alternative pathway in this disease (38).

The Eker rat is a well established model of tumorigenesis of the reproductive tract that has been utilized extensively as a model for the study of uterine leiomyoma (39). In this model, uterine leiomyomas and renal carcinomas develop subsequent to the loss of function of the second TSC2 allele (31). We observed that at 16 months, 100% of Eker rats develop endometrial hyperplasia and that endometrial hyperplasia in these animals was characterized by activation of mTOR signaling. Whether the development of endometrial hyperplasia is due to the loss of TSC2 function is not yet known, but is likely, as activation of mTOR signaling and phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein were identified in 100% of endometrial hyperplastic foci, and TSC2 is known to be an inhibitor of mTOR activation (15). Similar to human endometrial CAH, loss of negative feedback inhibition to IRS-1 was identified in nearly all of the Eker rat endometrial hyperplastic foci indicating that this characteristic of the neoplastic progression from normal endometrium to endometrial hyperplasia is conserved across species, a powerful indicator of its importance in disease progression.

Interestingly, in both the human samples and in the rat model, we occasionally identified endometrial glands that were microscopically normal but expressed phosphorylated S6. This observation was made in both “normal” human and rat endometrial glands. All of the microscopically normal endometrial glands with positive expression of phosphorylated S6 also retained positive expression for serine phosphorylated IRS-1.

This suggests that mTOR activation can occur early in endometrial glands that are microscopically normal (“pre-endometrial hyperplasia”), whereas loss of serine phosphorylated IRS-1 was associated with progression to hyperplasia. Our data suggest a progression sequence in which activation of mTOR (via loss of TSC2 or other events) is followed by loss of the negative feedback to IRS-1 in the early stages of development of endometrial hyperplasia. Mutter et al. have also identified molecular defects in microscopically normal human endometrium, namely loss of PTEN expression (40). Such PTEN-null, microscopically normal endometrial glands persist between menstrual cycles (41), but regress with progestin therapy (42). Importantly, loss of PTEN and upregulation of Akt would also lead to phosphorylation and inactivation of TSC2, resulting in loss of mTOR repression by this tumor suppressor. In our study, treatment with the mTOR inhibitor WAY-129327 was not associated with re-expression of serine phosphorylated IRS-1. This suggests that some early defects in the progression of normal endometrium to endometrial hyperplasia, such as loss of PTEN expression, are potentially reversible, while other molecular defects, such as loss of serine phosphorylated IRS-1, may not be reversible. Alternatively, other pathways not affected by WAY-129327 treatment such as MAPK signaling may be regulating IRS-1 phosphorylation.

In normal metabolic tissues such as WAT, liver and skeletal muscle of both humans and rats the IGF-IR/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is negatively regulated by serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 (17, 22, 23). This negative feedback to IRS-1/2 via S6K normally prevents rampant activation of insulin signaling (19). Numerous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that obesity is strongly associated with an increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and EC; in fact, EC is the cancer most closely associated with obesity (6, 43, 44). Hyperinsulinemia and the insulin resistant state are closely associated with obesity. Using serum adiponectin as a surrogate marker of insulin resistance, a number of groups have documented that insulin resistance is an independent risk factor for EC (45). Despite the link with obesity and insulin resistance, abnormal physiological states that are typically associated with increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, the majority of endometrial hyperplasias and cancers examined in this study had loss of serine phosphorylated IRS-1, irrespective of BMI. The basis for the loss in serine phosphorylated IRS-1 in endometrial hyperplasia and cancer cells is not clear at this point. However, our results from this work and from our previous studies (34) demonstrate that there are at least 2 different molecular mechanisms for increased signaling via the IGF-I receptor pathway in endometrial hyperplasia and cancer – up-regulation of IGF-I receptor and down-regulation of the negative feedback component, serine phosphorylated IRS-1.

Preclinical studies using rapamycin and its analogues have shown decreased growth of tumors, particularly in those that have reduced expression of PTEN or overexpression of AKT (46). Neshat et. al. compared the growth of PTEN(+/+) and PTEN(−/−) tumors either produced by subcutaneous injection of murine embryonic stem cells into immunodeficient nude mice or in androgen-dependent human prostate cancer xenografts in male SCID mice treated with a rapamycin analogue (CCI-779). The growth of PTEN(+/+) tumors was slowed by treatment with a rapamycin analogue but was completely blocked in PTEN(−/−) tumors in both models, showing an enhanced dependence on mTOR for tumor growth in the absence of PTEN expression (46). In addition, decreased neoplasia incidence with treatment with rapamycin analogues has been identified in endometrial hyperplasia in the PTEN(+/−) mouse model, prostate intraepithelial neoplasia in mice expressing Akt1, alveolar epithelial neoplasia induced by oncogenic K-ras, and in a mouse model of ductal carcinoma in situ (47–50). In our study, a 2-week treatment of Eker rats with the rapamycin analogue WAY-129327 resulted in a significant decrease in endometrial hyperplasia incidence, decreased endometrial epithelial proliferative indices, and inhibition of mTOR signaling in the endometrium. These results suggest the possible utility of using analogues of rapamycin as chemopreventive agents for women with endometrial hyperplasia to prevent the development of endometrioid-type endometrial carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NIH Uterine Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence 1P50CA098258-01 (R.R.B., A.S.M., and C.L.W.), NIH ES08263 and HD46282 (C.L.W.), and a post-doctoral fellowship from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Education Program in Cancer Prevention NCI R25-CA57730 (A.S.M). This work was presented in part in abstract form at the AACR 2008 Frontiers in Cancer Prevention Research Meeting, Washington D.C., November 16–19th.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:403–412. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<403::aid-cncr2820560233>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangemi M, Meneghetti G, Predebon O, Scappatura R, Rocco A. Obesity as a risk factor for endometrial cancer. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1987;14:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friberg E, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A. Diabetes and risk of endometrial cancer: a population-based prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:276–280. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SC, Lacey JV, Jr., Brinton LA, et al. Lifetime weight history and endometrial cancer risk by type of menopausal hormone use in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:723–730. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutanen EM. Insulin-like growth factors in endometrial function. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1998;12:399–406. doi: 10.3109/09513599809012842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backer JM, Myers MG, Jr., Shoelson SE, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase is activated by association with IRS-1 during insulin stimulation. Embo J. 1992;11:3469–3479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dearth RK, Cui X, Kim HJ, Hadsell DL, Lee AV. Oncogenic transformation by the signaling adaptor proteins insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 and IRS-2. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:705–713. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun XJ, Miralpeix M, Myers MG, Jr., et al. Expression and function of IRS-1 in insulin signal transmission. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22662–22672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15:807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon LP, Choi KM, Lin TA, Abraham RT, Lawrence JC., Jr. The rapamycin-binding domain governs substrate selectivity by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7428–7438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7428-7438.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Eszterhas A, et al. Tuberin regulates p70 S6 kinase activation and ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation. A role for the TSC2 tumor suppressor gene in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30958–30967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mothe I, Van Obberghen E. Phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on multiple serine residues, 612, 632, 662, and 731, modulates insulin action. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11222–11227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delahaye L, Mothe-Satney I, Myers MG, White MF, Van Obberghen E. Interaction of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: effect of substitution of serine for alanine in potential IRS-1 serine phosphorylation sites. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4911–4919. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, DeFea K, Roth RA. Modulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 tyrosine phosphorylation by an Akt/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9351–9356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tremblay F, Gagnon A, Veilleux A, Sorisky A, Marette A. Activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway acutely inhibits insulin signaling to Akt and glucose transport in 3T3-L1 and human adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1328–1337. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tzatsos A, Kandror KV. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:63–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah OJ, Wang Z, Hunter T. Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1650–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay F, Marette A. Amino acid and insulin signaling via the mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway. A negative feedback mechanism leading to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38052–38060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haruta T, Uno T, Kawahara J, et al. A rapamycin-sensitive pathway down-regulates insulin signaling via phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of insulin receptor substrate-1. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:783–794. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene MW, Sakaue H, Wang L, Alessi DR, Roth RA. Modulation of insulin-stimulated degradation of human insulin receptor substrate-1 by Serine 312 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8199–8211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueno M, Carvalheira JB, Tambascia RC, et al. Regulation of insulin signalling by hyperinsulinaemia: role of IRS-1/2 serine phosphorylation and the mTOR/p70 S6K pathway. Diabetologia. 2005;48:506–518. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crabtree JS, Jelinsky SA, Harris HA, et al. Comparison of human and rat uterine leiomyomata: identification of a dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6171–6178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCampbell AS, Walker CL, Broaddus RR, Cook JD, Davies PJ. Developmental reprogramming of IGF signaling and susceptibility to endometrial hyperplasia in the rat. Lab Invest. 2008;88:615–626. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antunes CM, Strolley PD, Rosenshein NB, Endometrial cancer, estrogen use, et al. Report of a large case-control study. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:9–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197901043000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes MP, Wang H, Espinal-Witter R, et al. PIK3CA and PTEN mutations in uterine endometrioid carcinoma and complex atypical hyperplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5932–5935. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu KH, Wu W, Dave B, et al. Loss of tuberous sclerosis complex-2 function and activation of Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in endometrial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2543–2550. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeung RS, Xiao GH, Everitt JI, Jin F, Walker CL. Allelic loss at the tuberous sclerosis 2 locus in spontaneous tumors in the Eker rat. Mol Carcinog. 1995;14:28–36. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940140107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Senechal K, Neshat MS, Whang YE, Sawyers CL. The PTEN/MMAC1 tumor suppressor phosphatase functions as a negative regulator of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15587–15591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutter GL, Lin MC, Fitzgerald JT, et al. Altered PTEN expression as a diagnostic marker for the earliest endometrial precancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:924–930. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.11.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCampbell AS, Broaddus RR, Loose DS, Davies PJ. Overexpression of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor and activation of the AKT pathway in hyperplastic endometrium. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6373–6378. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Contreras CM, Gurumurthy S, Haynie JM, et al. Loss of Lkb1 provokes highly invasive endometrial adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:759–766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oda K, Stokoe D, Taketani Y, McCormick F. High frequency of coexistent mutations of PIK3CA and PTEN genes in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10669–10673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stambolic V, Tsao MS, Macpherson D, Suzuki A, Chapman WB, Mak TW. High incidence of breast and endometrial neoplasia resembling human Cowden syndrome in pten+/− mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3605–3611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker CL, Hunter D, Everitt JI. Uterine leiomyoma in the Eker rat: a unique model for important diseases of women. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:349–356. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mutter GL, Ince TA, Baak JP, Kust GA, Zhou XP, Eng C. Molecular identification of latent precancers in histologically normal endometrium. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4311–4314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mutter GL, Lin MC, Fitzgerald JT, Kum JB, Eng C. Changes in endometrial PTEN expression throughout the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2334–2338. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng W, Baker HE, Mutter GL. Involution of PTEN-null endometrial glands with progestin therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soliman PT, Oh JC, Schmeler KM, et al. Risk factors for young premenopausal women with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:575–580. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154151.14516.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glade MJ. Food, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research/World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research, 1997. Nutrition. 1999;15:523–526. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soliman PT, Wu D, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Association between adiponectin, insulin resistance, and endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2376–2381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10314–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Namba R, Young LJ, Abbey CK, et al. Rapamycin inhibits growth of premalignant and malignant mammary lesions in a mouse model of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2613–2621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milam MR, Celestino J, Wu W, et al. Reduced progression of endometrial hyperplasia with oral mTOR inhibition in the Pten heterozygote murine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:247. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.872. e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wislez M, Spencer ML, Izzo JG, et al. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin reverses alveolar epithelial neoplasia induced by oncogenic K-ras. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3226–3235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]