Abstract

This is the first study to evaluate adding emotionally focused therapy for couples (EFT) to antidepressant medication in the treatment of women with major depressive disorder and comorbid relationship discord. Twenty-four women and their male partners were randomized to six months of medication management alone (MM) or medication management augmented with EFT (MM+EFT). Medication management followed the Texas Medication Algorithm Project guidelines. Fifteen EFT sessions were delivered following the EFT treatment manual. The primary outcome was severity of depressive symptoms (assessed by the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rated version [IDS-C30] administrated by evaluators blinded to cell assignment). Secondary outcome was relationship quality as assessed by the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI). Results from assessments at intake, termination, and two post-treatment follow-ups were analyzed using growth analysis techniques. IDS-C30 scores improved over six months of treatment, regardless of treatment assignment, and women receiving MM+EFT experienced significantly more improvement in relationship quality compared to women in MM. Since relationship discord after depression treatment predicts worse outcome, interventions improving relationship quality may reduce depression relapse and recurrence. Testing this hypothesis in larger samples with longer follow-up could contribute to knowledge on the mechanisms involved in determining the course of depressive illness.

Too few patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) achieve remission of symptoms after monotherapy with either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy. In the STAR*D study - the largest prospective randomized clinical trial of the treatment of MDD conducted in community settings - only about a third of patients reached remission in the first step after up to 14 weeks of treatment with citalopram [remission defined as a score ≤ 7 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17) (Hamilton, 1960)] (Trivedi et al., 2006). In another study, after 16 weeks of treatment only 46% of patients receiving antidepressant medication and 40% of patients receiving cognitive therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) had reached remission (definition of remission including a score ≤ 7 on the HRSD17) (DeRubeis, et al., 2005). In a sample of patients with chronic depression (at least two years of symptom duration) remission rates were 29% for patients treated with nefazodone, 33% for patients receiving the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (McCullough, 2000), and 48% for patients receiving both treatments (Keller, et al., 2000). Remission in this study was defined as a score ≤ 8 on the 24-item HRSD. Rates of remission from depressive symptoms are often less than 50% regardless of treatment.

Failure to reach and sustain remission from depression is associated with a host of complications including increased risk of recurrence (Judd, et al., 2000; Paykel, et al., 1995), functional impairment (Hirschfeld, et al., 2002; Miller, et al., 1998), and mortality (Judd, Akiskal, & Paulus, 1997). Although some published guidelines recommend antidepressant medication monotherapy as an appropriate first phase treatment for a major depressive episode in adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Depression Guideline Panel, 1993) others argue for the benefits of starting combination medication and psychotherapy, even as a first-step treatment, due to the low remission rates from monotherapy, particularly in patients with various comorbidities (Fava & Rush, 2006; Hollon, et al., 2005; Rush, 2007).

For clinicians wishing to utilize combination treatment, there is currently limited research to guide them in determining what treatments to combine and for whom (Hollon, et al., 2005). Models of psychotherapy studied in combination with antidepressant medication have included cognitive therapy (Beck, et al., 1979; Thase, et al., 2007), the Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (Keller, et al., 2000; McCullough, 2000), and interpersonal psychotherapy (Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984; Thase, et al., 1997). Whisman and Uebelacker (1999) suggested that it might be beneficial to combine antidepressant medication with couple therapy. Other than one study with inconclusive results (Friedman, 1975), there have not been any studies which have evaluated antidepressant medication in combination with couple therapy. In this paper we report results of a randomized clinical trial comparing antidepressant medication alone to antidepressant medication combined with emotionally focused therapy for couples (Johnson, 2004; Johnson & Denton, 2002) in the treatment of women with comorbid major depressive disorder and relationship discord who are in a committed, heterosexual relationship.

Emotionally focused therapy for couples (EFT) is a brief, focused, and directive experiential model of psychotherapy for couples that is a synthesis of family systems (e.g., Fisch, Weakland, & Segal, 1983) and experiential approaches to psychotherapy (e.g., Perls, Hefferline, & Goldman, 1951; Rogers, 1951). Drawing from attachment theory (e.g., Bowlby, 1969; Hazan & Shaver, 1987), it is assumed in EFT that adults form relationships to meet attachment needs and that much of relationship distress can be understood as attachment distress (Johnson, 2004). The EFT approach has been summarized as “…a focus on the circular cycles of interaction between people, as well as on the emotional experiences of each partner during the different steps of the cycle” (Johnson & Denton, 2002, pp. 223–224). The goal of treatment is to use emotional experience to help the partners engage in addressing their repetitive negative interaction cycles and, in doing so, help the couple break the negative interaction cycles and strengthen their attachment bond.

There is both empirical and theoretical support for targeting relationship discord in the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder. Major depressive disorder has been reliably shown to be associated with relationship discord (Whisman, 2001a). Relationship discord is a predictor of future major depressive episodes in the community (Whisman & Bruce, 1999) and of poor response to treatment with either medication, psychotherapy, or their combination (Addis & Jacobson, 1996; Bromberger, Wisner, & Hanusa, 1994; Denton, et al., 2010; Hickie & Parker, 1992; Miller, et al., 1998; Rounsaville, Weissman, Prusoff, & Herceg-Baron, 1979). Adults who do not respond to treatment for major depressive disorder have greater levels of relationship discord than do treatment responders (Denton, et al., 2010; Vittengl, Clark, & Jarrett, 2004; Whisman, 2001b). Even after recovery from a depressive episode, patients continue to report more relationship problems than controls (Herr, Hammen, & Brennan, 2007; Merikangas, Prusoff, Kupfer, & Frank, 1985) and demonstrate negative interpersonal behaviors with their partner (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997).

Available evidence suggests that couple therapy is as efficacious as pharmacotherapy or individual psychotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder and is more efficacious in treating comorbid relationship discord (all treatments as monotherapies) (Barbato & D'Avanzo, 2006; Denton, Golden, & Walsh, 2003). In the one published study in which couple therapy was combined with antidepressant medication for the treatment of depression (Friedman, 1975), 196 participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups which included either amitriptyline or pill placebo combined with either marital therapy (unspecified model) or minimal physician contact. The criteria for a diagnosis of depression were (a) agreement between two screening clinicians that the primary diagnosis was “depression” and (b) a score ≥ 7 on the Raskin Depression Rating Scale (Raskin, Schulterbrandt, Reatig, & McKeon, 1969). Unfortunately, results directly comparing the four treatment cells were not reported making interpretations difficult. Data from the two marital therapy groups were combined and compared to the two minimal contact groups and data from the two amitriptyline groups were combined and compared to the two placebo groups. There were no differences at the end of treatment between these groupings (Friedman, 1975).

The purpose of the current pilot study was to compare the relative efficacy of antidepressant medication (bupropion XL, escitalopram, sertraline, or venlafaxine XR) augmented with couples therapy (EFT) to antidepressant medication alone in reducing depressive symptoms in women diagnosed with comorbid major depressive disorder and relationship discord. We used emotionally focused therapy for couples (EFT) as the model of couple therapy (Johnson, 2004; Johnson & Denton, 2002). Emotionally focused therapy has been found to improve dyadic discord relative to wait-list control groups (Denton, Burleson, Clark, Rodriguez, & Hobbs, 2000; Goldman & Greenberg, 1992; James, 1991; Johnson & Greenberg, 1985; Walker, Johnson, Manion, & Cloutier, 1996) and is considered an empirically supported treatment of relationship discord (Baucom, Shoham, Mueser, Daiuto, & Stickle, 1998). Prior research found that EFT alone reduced depressive symptoms in women with major depressive disorder and relationship discord as much as pharmacotherapy alone (Dessaulles, Johnson, & Denton, 2003). Six months following termination of treatment, women treated with EFT had significantly less depressive symptomatology than when they completed treatment (Zimmerman, Coryell, Corenthal, & Wilson, 1986) while women in the pharmacotherapy group had no further improvement (pharmacotherapy was discontinued at the end of treatment) (Dessaulles, et al., 2003). The current report fills a gap in the literature since the efficacy of EFT (or other models of couple therapy) combined with antidepressant medication has not yet been adequately evaluated.

This study evaluated the primary hypothesis that antidepressant medication management augmented with EFT (MM+EFT) would reduce depressive symptoms significantly more than medication management alone (MM) for women with comorbid major depressive disorder and dyadic discord. The secondary hypothesis was that MM+EFT would reduce relationship discord significantly more than MM.

Method

All procedures were IRB approved before the study began and annually.

Participants

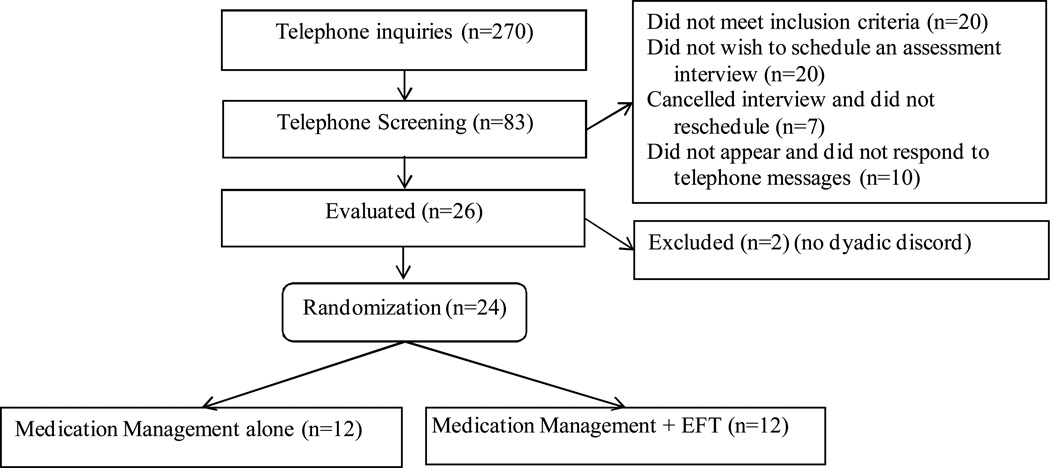

Participants were 24 women and their male spouses/partners recruited between March, 2006 and August, 2007. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1 along with their rationale. Participant flow is shown in Figure 1. The public learned of the research study through radio and newspaper advertising, flyers posted at public places, and word-of-mouth. Male and female prospective participants called the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Family Studies Center to receive information about the study. If interested, the female partners participated in a telephone screening interview during which they were as+ked about: their mood, whether they were in mental health treatment, marital status, if they were currently living with their partner, the general status of the couple’s relationship, whether there was intimate partner violence, if either partner had an active problem with alcohol or drug abuse, whether the woman was currently taking antidepressant medication, whether she had ever taken one of the study medications and, if so, what her experience was with that medicine. The 30-item clinician-rated version of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C30; Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett, & Trivedi, 1996) and the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983) were then administered.

Table 1.

Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, established using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) | The condition under study |

| Scored 24 or more on the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Clinician Rated Version (IDS-C30) (Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett, & Trivedi, 1996) | Corresponds to a moderate or greater level of depressive symptoms |

| Scored 29 or less on the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI) (Norton, 1983) | Criterion for dyadic discord |

| Female | Insufficient statistical power to evaluate gender differences |

| Spoke and read English | Most instruments were available only in English, clinicians were not bilingual |

| Legally married and living with spouse or in a committed relationship and cohabiting at least one year | EFT is a treatment for established, committed couples |

| Agreed to taper ineffective antidepressant medications (if on any) and begin protocol pharmacotherapy | To have consistency in the pharmacologic treatment |

| Aged 18–70 | Patients outside of this range might need other interventions |

| Exclusion | Rationale |

| Husband/partner unwilling to participate in research | EFT requires both partners to be part of treatment |

| In a same-sex relationship | Insufficient statistical power to evaluate gender differences |

| Intimate partner violence defined as a score of 3 on any items of the Partner Abuse Interview (Pan, Ehrensaft, Heyman, & Scwartz, 1997) | Intimate partner violence is a contraindication to EFT |

| Either partner currently involved in an extra-marital/relationship affair | Extra-marital/relationship affairs are a contraindication to EFT |

| Either partner has an active substance use disorder | An active substance use disorder is a contraindication to EFT |

| Active suicidal ideation with possible intent or probable risk | Would require immediate crisis management |

| Either partner had a diagnosis of organic mental disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder | Would require different interventions, would pose special issues in the use of EFT |

| Currently receiving other mental health treatment | Would confound interpretation of results |

| Previous failure with 2 or more of the 4 study medications | Protocol called for use of up to 3 medications which not be possible if there had already been failure with 2 of the 4 available medications |

| Pregnant or planning to become pregnant in next 12 months | All study medications carried a pregnancy risk factor of C (No adequate studies in humans) |

| One or both partners has decided to separate within the next 12 months | Would need a different couple intervention than EFT |

| Presence of a concurrent medical condition that could cause depression | Would require different intervention |

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

If the woman appeared to meet inclusion and exclusion criteria, and her partner was willing, they were scheduled for a face-to-face assessment at the Family Studies Center. At this session informed consent was obtained. The couple was then separated to complete the study questionnaires, an intimate partner violence interview assessment, and the mood module of the SCID. The partners were then reunited. If they did not qualify for study inclusion they were given referrals for community care. If all inclusion and exclusion criteria were satisfied, their interest in participation was re-affirmed and they received their randomized group assignment. Randomization was stratified based on whether the male partner met criteria for a major depressive episode. The randomization schedule was prepared prior to the start of study enrollment. Slips of paper indicating the group assignment were sealed in numbered, opaque envelopes and opened by the research assistant in sequence for each successive enrolled and eligible participant couples.

Treatment

Treatment lasted six months for all participants.

Medication management

All women were treated with one of four antidepressant medications approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for this indication: sertraline, escitalopram, bupropion XL, and venlafaxine XR. Treatment was delivered by a board-certified psychiatrist and followed the major depressive disorder treatment algorithm of the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) (Suehs, et al., 2008) and a manual for conducting medication management sessions (Fawcett, Epstein, Fiester, Elkin, & Autry, 1987). Initial medication was selected clinically (e.g., participant or physician choice, side effect profile, past medication treatment experience, etc.). Medication management sessions were scheduled flexibly following the TMAP protocol (Suehs, et al., 2008). Medication dosages were adjusted based on scores on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Rush, et al., 2003) (administered at each medication management session) following the TMAP protocol (Suehs, et al., 2008). Medication could be changed for nonresponse or intolerability as per the TMAP protocol (Suehs, et al., 2008).

The medications the women received as their final medication (if more than one used) and mean dosages by treatment group included: bupropion XL (3 women in the medication alone group; mean dose 250 mg/day), venlafaxine XR (one women in the medication alone group; dose was 150mg/day), escitalopram (two women in each group; daily dose of 20 mg), and sertraline (6 women in medication alone group; mean dose of 92 mgs/day and 6 women in combined treatment group; mean dose of 83 mgs/day). The remaining women never started on medication or withdrew from the study before establishing a final dose.

Emotionally focused therapy for couples and medication management

Emotionally focused therapy for couples (EFT) was delivered following the EFT treatment manual (Johnson, 2004) by four couple therapists (two women and two men) who were licensed as Marriage and Family Therapists. Two therapists were master’s prepared and two held doctoral degrees. All therapists participated in a week-long externship conducted by Dr. Susan Johnson, co-founder of the EFT approach, at the Ottawa Couple and Family Institute. They had at least three practice cases and obtained and sustained a score of 40 or better on the Emotion Focused Therapy-Therapist Fidelity Scale (Denton, Johnson, & Burleson, 2009). Weekly supervision was held throughout the duration of the study with participation by expert EFT supervisors. Videorecordings of selected therapy sessions were reviewed by the supervisor and team weekly.

EFT is a synthesis of family systems and experiential approaches to psychotherapy that is carried out applying nine steps across three stages of treatment ( Johnson, 2004; Johnson, et al., 2005). There were 15 sessions: the first 10 sessions were weekly while the last five were biweekly. Sessions were 50 minutes, were videorecorded, and were held in the private offices of three of the therapists located in the Dallas, Texas metropolitan area and at the medical-school based Family Studies Center for the fourth. Couples randomly assigned to receive combination therapy were assigned to a couple therapist based on therapist availability and the couple’s geographic location in the Dallas metroplex relative to the four treatment locations.

Additionally, women in the combination treatment group received medication management following the same format as the women in the medication management alone group. Medication management visits were held separately from couple therapy sessions and were not attended by husbands/partners.

Instruments

Demographic information

The following demographic information was collected: age, gender, duration of current relationship, number of times married, divorced and widowed, years of education, race and ethnicity, and family income.

Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rated 30-item version

The 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rated version (IDS-C30) was used as the primary outcome measure to assess severity of the signs and symptoms of depression (Rush, et al., 1996). Items assess all nine criterion symptoms of a major depressive episode and commonly associated symptoms such as anxiety. Each item is rated on a 0 to 3 scale (higher scores represent greater symptom severity). Twenty-eight of the 30 items contribute to the total score (range from 0–84) as only appetite increase or decrease and only weight increase or decrease are rated. A score less than 12 represents the absence of depressive symptoms while a score greater than 23 represents moderate depressive severity. The IDS-C30 has good internal consistency (ά = 0.90) and item-total correlations (Trivedi, et al., 2004). The IDS-C30 is highly correlated with the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Vittengl, Clark, Kraft, & Jarrett, 2005) and has been used in numerous clinical studies (Rush, First, & Blacker, 2007).

Quality of Marriage Index

Dyadic discord was assessed with the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983). Research supports the validity and reliability of the QMI (Norton, 1983; Schumm, et al., 1986) and it is recommended as a global assessment of marital satisfaction (Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000). The QMI is a six-item self-report inventory. The first five items utilize a 7-point Likert scale while the sixth item utilizes a 10-point Likert scale with lower scores representing greater dyadic discord (range of 6–45). A score of 28 or less corresponds to a score of 97 or less on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Heyman, Sayers, & Bellack, 1994; Spanier, 1976) and was the criterion for relationship distress.

Commitment Inventory

Commitment to the relationship was assessed with four items from the Commitment Inventory (Stanley & Markman, 1992) which are in the form of statements to which the respondents indicated their degree of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale. These four items have been used previously as a separate scale (Stanley, Markman, & Whitton, 2002). Higher scores represent a greater level of commitment to the relationship (range 4–20). As there are no norms for this scale, the median intake score of the women in the present sample – 14.5 – was used to divide the women into groups of “low” and “high” commitment.

Procedure

Study assessments

All participants (patients and partners) received nine study assessments (intake, after each of the six months of treatment, and at 3 and 6 month post-treatment completion). At the conclusion of month six (the end of treatment) the couple returned to the Family Studies Center to repeat the study questionnaires. Interviewers unaware of treatment group assignment administered the IDS-C30 and QMI over the telephone. The first assessment occurred between the intake assessment interview and the first clinical visit. Subsequent assessments were at the end of each of the first six months and at 9 and 12 months after beginning the study. There were two interviewers at any given time and over the course of the study four interviewers were utilized. The interviewers were graduate students in clinical psychology or marriage and family therapy. All interviewers received training in administering the assessment instruments from the first author. During the course of the study, the first author met weekly with the raters and a research assistant to jointly rate audiorecordings of the interviews for quality control. Discrepancies in ratings were discussed and resolved although the original rating of the interviewer was used as the official rating. Participants were instructed not to reveal their treatment group assignment to the interviewers. In one instance, a study participant inadvertently revealed their group. That interviewer was not utilized for subsequent assessments of that participant.

Data Analysis

Growth analysis techniques were employed using Mplus statistical software (version 5; Múthen & Múthen, 2007). Mplus utilizes full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedures which allows for the inclusion of respondents with missing data. Due to the small sample size in the current pilot study, several strategies were employed to retain power and limit the probability of committing a Type II error (failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false) (Cohen, 1988). First, IDS-C30 and QMI scores were not included in the same model, but were instead modeled separately. Second, while the outcome variables were assessed monthly, only data from pre-intervention, post-intervention, and both follow-up assessments were used in the current analysis. Both of these strategies simplified the analyses by utilizing fewer variables. Third, while data from both partners were collected in the current study, models were fit examining data from the female participants (the IP) only. Examining responses of both partners would have required the practice of dyadic data analytic procedures, or fitted models using linked data, because independence of data could not be assumed (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Unfortunately models of this level of sophistication could not be fit with the current sample size.

A series of growth models was fit to the data to examine the trajectories of change in the primary domains of interest (depressive severity and relationship quality). We first examined whether systematic change existed in the outcome variables (IDS-C30 and QMI). Next, we determined the nature of growth (linear or curvilinear). We then fit growth models for each outcome (IDS-C30 and QMI) to the data and added group membership as a predictor. After adding the predictor (treatment group membership) to each model, the significance of group membership on the growth parameters in both models was determined by fitting a reduced model and conducting a delta-chi square difference test. Reduced models were formulated by constraining the parameters from the predictor being tested on the growth parameters to zero (Keiley, Martin, Liu, & Dolbin-MacNab, 2005; Singer & Willett, 2003). Months were used as the time metric in the current analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The 24 female participants were randomized to medication management alone (MM) (n = 12) or to medication management augmented with EFT couple therapy (MM+EFT) (n = 12). Demographic characteristics of the female participants are presented in Table 2. The only baseline difference between the groups was that the women randomized to MM had a higher commitment to the relationship at intake than did the women randomized to MM+EFT (16.3 vs. 13.8, respectively, t (22) = 2.66, p = .01). Mean scores for the IDS-C30 and QMI at each assessment are presented in Table 3 along with the number of participants who completed each assessment.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Treatment Group (Female Index Patients)

| Participant Character | MM (n = 12) |

MM+EFT (n = 12) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 0.60a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34.0 (11.5)† | 31.7 (8.7) | |

| Range | 20 to 57 | 22 to 48 | |

| Education in years | 0.84a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 14.6 (2.8)† | 14.8 (1.8) | |

| Range | 12 to 22 | 12 to 18 | |

| IDS-C30 Scoreat Base line | 0.87a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.3 (9.6) | 39.6 (10.2) | |

| Range | 26 to 55 | 26 to 56 | |

| QMI Score at Baseline | 0.16a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 20.4 (8.1) | 15.9 (7.1) | |

| Range | 6 to 30 | 6 to 26 | |

| Commitment Level Score at Baseline | 0.01a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (2.3) | 13.7 (2.2) | |

| Range | 13 to 20 | 11 to 19 | |

| Marital Status, N (%) | 0.81b | ||

| Married | 9 (75.0) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Not Married | 3 (25.0) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Race, N (%) | 0.64b | ||

| White | 8 (66.7) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Income, N (%) | 0.68c | ||

| ≤ $50,000 | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| > $50,000 | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

n = individual participants per group; Not Married = cohabitating.MM = pharmacotherapy; MM+EFT = pharmacotherapy augmented with EFT.

t statistic (two-tailed test) was used to test for mean difference between the two treatment groups.

Fisher's Exact Test (two-sided) was used to test for differences between the two treatment groups.

Chi-square test was used to test for differences between the two treatment groups.

1 missing observation.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for the IDS-C30 and QMI at each analyzed assessment

| IDS-C30 |

QMI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM | MM+EFT | MM | MM+EFT | |||||

| n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | |

| Intake | 12 | 40.3 (9.6) | 12 | 40.0 (10.2) | 12 | 20.4 (8.1) | 12 | 15.9 (7.1) |

| Month 6 | 9 | 16.9 (17.0) | 4 | 3.5 (1.9) | 9 | 26.2 (10.8) | 4 | 36.0 (4.5) |

| Month 9 | 7 | 17.1 (20.2) | 3 | 10.3 (11.9) | 7 | 28.7 (10.9) | 3 | 21.0 (12.5) |

| Month 12 | 7 | 27.0 (20.0) | 4 | 17.8 (13.2) | 7 | 23.6 (10.7) | 4 | 27.0 (14.2) |

n = number of observatins for that assessment period

Attrition Rates and Reasons

In the medication management alone group, ten of 12 women (83%) completed treatment. Two women dropped out immediately after randomization. One of these said that she thought her marriage was “too far gone” and she was moving out-of-state to where her family lived. The second stated that she felt irritable and cranky each time she had talked with the research staff, had difficulty knowing how to answer the questions, and was afraid she would harm the study results.

Of the 12 women randomized to medication management plus EFT, couples completed an average of 10.6 sessions (out of 15). Six (50%) completed all treatments (i.e., participated in medication management sessions for the six months of the study and completed all of their couple therapy sessions). One woman dropped out of EFT after three visits (deciding not to continue in the relationship) but completed MM. Three women dropped out of both treatments after completing over half of the sessions: one woman said the EFT sessions were too stressful (attended 12 of 15 couple therapy sessions); one couple was having continuing conflict and the man accused the woman of having an affair (attended 11 of 15 couple therapy sessions); one couple cited problems with childcare; however, later reported that the woman moved out shortly after leaving the study (attended 11 of 15 couples therapy sessions). Two women attended 2 MM visits and then dropped out without attending the first couple therapy session for unknown reasons. The difference in drop-out rates between groups was not statistically significant.

Relationship Terminations During the Study

Seven of the 24 women (29%) experienced a separation from their partner during the study. Two of the seven were in the medication alone group while five were receiving the combination of medication management and EFT. While this difference was not statistically significant, we explored the phenomenon of separations further by dividing the sample into “low relationship commitment” and “high relationship commitment” based on the median score of 14.5 in this sample on the Commitment Inventory (Stanley & Markman, 1992). As seen in Table 4, 6 of the separations occurred in the low commitment group – 1 receiving medication management alone and 5 receiving medication management + EFT. In the high commitment group, there was only 1 separation which was in the medication management alone group. There was not a statistically significant difference in IDS-C scores when comparing the women who experienced a separation (x̄=13.0) and the women who did not (x̄=19.8).

Table 4.

Separations during study by treatment group and woman's relationship commitment level

| Medication Alone |

EFT + Medication |

|

|---|---|---|

| Low Commitment | 1 | 5 |

| High Commitment | 1 | 0 |

Are Patients Less Depressed if Pharmacotherapy is Augmented with EFT?

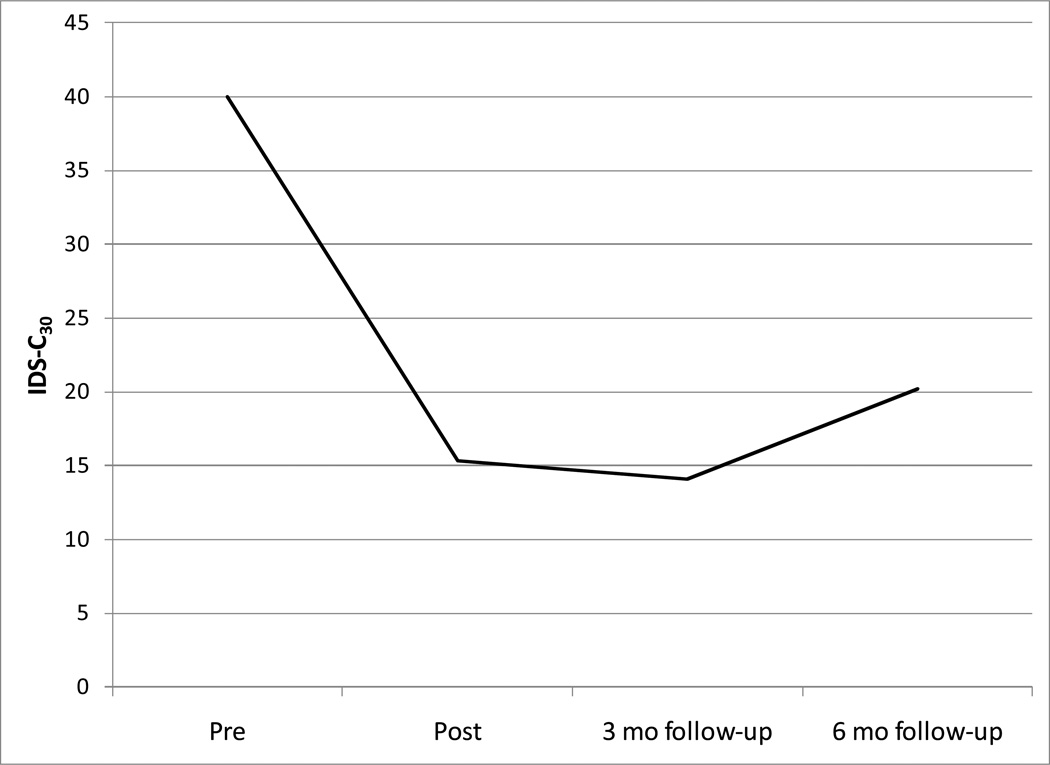

A growth model was fit to examine the trajectory of curvilinear change in depression over time. Group membership was added as a predictor, but was not found to contribute to the model (Δ χ2 = 1.27, Δ df = 1, Critical χ2 = 3.84). Therefore, the final fitted model examined change in IDS-C30 scores for all participants over time. The fit statistics demonstrate good model fit, χ2(4)= 2.84, p = .59 (comparative fit index=1.00). The mean parameter estimates for the final model indicated that the intercept (40.02, p < .00), slope (−78.96, p < .00), and quadratic acceleration (59.12, p < .00) were all significantly different from zero (See Table 4). This denotes that, on average, IDS-C30 scores were significantly above zero at intake and decreased significantly over the treatment interval with a significant concomitant acceleration in scores after treatment ended. On average, regardless of group membership, IDS-C scores significantly declined after 6 months of treatment and increased minimally six months after termination. Figure 2 depicts a fitted depression trajectory from a prototypical female participant in the sample.

Figure 2.

Fitted depression trajectory (IDS-C30) for a prototypical female over time

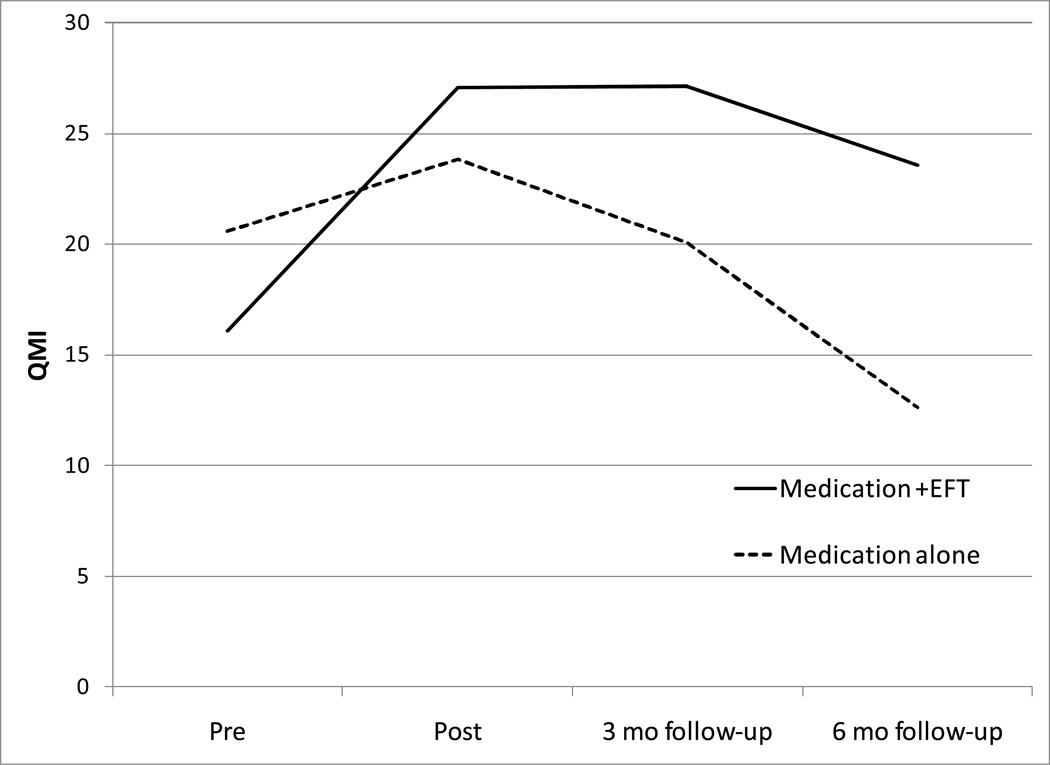

Do Patients Experience a Greater Level of Relationship Quality if Pharmacotherapy is Augmented with EFT?

A growth model was fit to examine curvilinear change in relationship quality over time. Group membership was added to the model to determine whether differences existed in growth trajectories among the treatment groups. Group membership significantly contributed to the model (Δχ2 = 4.62, Δdf = 1, Critical χ2 = 3.84) and was, therefore, the best-fitting model of relationship quality. The fit statistics demonstrate adequate model fit, χ2(5)= 7.86, p = .16 (comparative fit index=.93). The mean parameter estimates for the final fitted model indicated that the intercept (20.56, p < .00), slope (20.97, p < .00) and quadratic (−15.23, p < .00) were significantly different from zero. Group membership was a significant predictor of the average rate of true change (15.38, p < .03) and rate of acceleration (−13.66, p < .00), but had no effect on the average initial status (−4.46, p < .14). This indicates that the treatment groups did not significantly differ on symptomatology at intake. The MM+EFT females reported significantly more improvement in relationship quality over time in comparison to MM females. In addition, on average, the relationship quality of females in the MM group declined rapidly following treatment termination, while MM+EFT participants’ experienced less of a decline. Figure 3 illustrates a fitted relationship quality trajectory for prototypical members of the MM and MM+EFT treatment conditions.

Figure 3.

Fitted relationship quality (QMI) trajectory for a prototypical female in the control and treatment group over time.

Discussion

This is the first study to compare antidepressant medication alone to antidepressant medication augmented with emotionally focused couple therapy for women with comorbid major depressive disorder and relationship discord. Independent evaluators blinded to cell assignment rated fewer depressive symptoms in both groups of women after six months of treatment compared to intake. Women with EFT plus medication reported more improvement in relationship satisfaction than did women who received medication alone.

Improving relationship satisfaction is likely to be important in advancing long-term management of depression. Poor relationship satisfaction predicts increases in depressive symptoms. For example, in the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, lower marital adjustment after treatment with imipramine, interpersonal psychotherapy, or cognitive therapy predicted a worse outcome on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Depression Scale (Hamilton, 1960) at 6, 12, and 18 months post-treatment (Whisman, 2001b). Marital discord was associated with the return of depressive symptoms one year after completing a study in which patients had reached remission with fluoxetine treatment (Reimherr, Strong, Marchant, Hedges, & Wender, 2001). Marital distress and perceived criticism from the spouse were associated with relapse of unipolar depression in 39 patients completing inpatient hospital treatment (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989). While, the present study did not include continuation phase treatment and only included a six month follow-up, we hypothesize that interventions which improve relationship quality may also prevent, delay, or ameliorate relapses and recurrences of major depressive disorder. This hypothesis requires rigorous testing in a well-powered randomized controlled trial with sufficient durations of acute and continuation phase treatment and follow-up through the period of risk.

About a quarter of the women experienced a separation from their partner during this study. Five of these women were in the group receiving EFT. Although the difference in separations was not statistically significant between the groups, we had to consider whether separation could be an adverse event predicated by EFT. Relationship termination is usually considered an adverse event in studies where the primary outcome is relationship quality. All five of the women who separated during the course of EFT were in the lower half of pretreatment commitment to the relationship. Among those women in the upper half of relationship commitment who received EFT, there were no separations. We also note that the women assigned to EFT reported a lower intake commitment to their relationships, yet their relationship satisfaction improved after MM plus EFT. In addition, the primary aim of this pilot study was to compare reductions in depressive symptoms in the two arms. At the end of treatment, there was no significant difference in the severity of depressive symptoms in women who did and did not separate from their partners. Although no conclusive clinical recommendations can be drawn from this small sample, it may be that low relationship commitment is a risk factor for separation among depressed women receiving EFT – even when they have no plans for separation upon entering treatment.

Limitations of this preliminary study include the absence of fidelity assessments of the couple therapists’ adherence to the EFT model. Weekly supervision with expert EFT therapists and monitoring of select video-recordings of therapy sessions increased the likelihood that EFT was delivered properly. Nonetheless, it is desirable in assess to assess systematically fidelity to the EFT model with a valid and reliable instrument. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the results. Approximately 10% of individuals calling to inquire about the study eventually were randomized. While such a relatively low yield is not uncommon in clinical research, challenges to recruitment in this study included the refusal of some male partners to participate and women who were not willing to be randomized to medication alone.

Another limitation is that the index patients were all female. Although six of the 24 (25%) male partners met the criteria for major depressive disorder, this was not enough to analyze their results separately. Approximately 1 in 3 people diagnosed with major depressive disorder is male (Blazer, Kessler, McGonagle, & Swartz, 1994; Kessler, et al., 2003) and men may experience depression in somewhat different ways than women (Chuick, et al., 2009). These statistics highlight the importance of including men as index patients in future studies. Finally, the sample did not include same-sex couples further limiting the generalizability of the results.

In conclusion, while the addition of EFT to antidepressant medication did not incrementally reduce depressive symptoms, EFT did improve relationship quality. Whether EFT for couples contributes to improved long-term depression outcomes is an intriguing yet untested question with relevance for the identification of the mechanisms involved in the onset and maintenance of depressive illness.

Table 5.

Fit Statistics and growth parameters for IDS-C30 and QMI final fitted models for pre, post, 3 month follow-up, and 6 month follow-up.

| Mean | Effect of Group Membership on

Growth Parameters |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | χ2 | df (p) | CFI | Intercept Growth Parameter (SE) |

Slope Growth Parameter (SE) |

Quadratic Growth Parameter (SE) |

Intercept Growth Parameter (SE) |

Slope Growth Parameter (SE) |

Quadratic Growth Parameter (SE) |

||

| IDS Quadratic | 2.84 | 4 (.59) | 1.00 | 40.02** (1.93) | −78.96** (12.69) | 59.12** (9.49) | - | - | - | ||

| QMI Quadratic with Predictor (Group) | 7.86 | 5 (.16) | .93 | 20.56** (2.11) | 20.97** (3.95) | −15.23** (2.01) | −4.46 (2.98) | 15.38* (7.13) | −13.66** (3.32) | ||

p<.05

p<.00l|

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant K23MH063994 (Denton). Portions were presented at the 49th Annual NCDEU Meeting, Hollywood, Florida, June, 2009 and at the annual conference of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, Sacramento, California, October, 2009. Medication was provided by Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Appreciation is expressed to colleagues who contributed to this research: Brent Bradley, Anna Brandon, Effie Clewis, Fallon Cluxton-Keller, Adam Coffey, Connie Cornwell, Clyde Hicks, Robin Jarrett, Susan Johnson, Tara Lehan, Gloria Martin, Gail Palmer, Alyssa Parker, and Douglas Tilley.

Contributor Information

Wayne H. Denton, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas

Andrea K. Wittenborn, Department of Human Development, Virginia Tech

Robert N. Golden, Department of Psychiatry and Dean’s Office, University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine and Public Health

References

- Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Reasons for depression and the process and outcome of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1417–1424. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(Supplement 4):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato A, D'Avanzo B. Marital therapy for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004188.pub2. Issue 2. Art. No.: CD004188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Volume 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:964–980. [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH. Marital support and remission of treated depression: A prospective pilot-study of mothers of infants and toddlers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182:40–44. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuick CD, Greenfeld JM, Greenberg ST, Shepard SJ, Cochran SV, Haley JT. A qualitative investigation of depression in men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2009;10:302–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton WH, Burleson BR, Clark TE, Rodriguez CP, Hobbs BV. A randomized trial of emotion-focused therapy for couples in a training clinic. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2000;26:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton WH, Carmody TJ, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Arnow BA, et al. Dyadic discord at baseline is associated with lack of remission in the acute treatment of chronic depression. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:415–424. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton WH, Golden RN, Walsh SR. Depression, marital discord, and couple therapy. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2003;16:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Denton WH, Johnson SM, Burleson BR. Emotion-Focused Therapy-Therapist Fidelity Scale (EFT-TFS): Conceptual development and content validity. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy. 2009;8:226–246. doi: 10.1080/15332690903048820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline number 5: Depression in primary care. Volume 2. Treatment of major depression. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Policy and Research; 1993. AHCPR Publication 93-0550. [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaulles A, Johnson SM, Denton WH. Emotion-focused therapy for couples in the treatment of depression: A pilot study. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2003;31:345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ. Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: A literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2006;75:139–153. doi: 10.1159/000091771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Epstein P, Fiester SJ, Elkin I, Autry JH. Clinical management imipramine/placebo administration manual. NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1987;23:309–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisch R, Weakland JH, Segal L. The tactics of change: Doing therapy briefly. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AS. Interaction of drug therapy with marital therapy in depressive patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:619–637. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760230085007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman A, Greenberg L. Comparison of integrated systemic and emotionally focused approaches to couples therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:962–969. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr NR, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Current and past depression as predictors of family functioning: A comparison of men and women in a community sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:694–702. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Hickie I, Parker G. The impact of an uncaring partner on improvement in non-melancholic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1992;25:147–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90077-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM, Dunner DL, Keitner G, Klein DN, Koran LM, Kornstein SG, et al. Does psychosocial functioning improve independent of depressive symptoms? A comparison of nefazodone, psychotherapy, and their combination. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Trivedi M, Rush AJ. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: Which monotherapy or combined treatment? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:455–468. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Teasdale JD. Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:229–235. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James PS. Effects of a communication training component added to an emotionally focused couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1991;17:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM. The practice of emotionally focused couple therapy: Creating connection. 2nd ed. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Bradley B, Furrow J, Lee A, Palmer G, Tilley D, et al. Becoming an emotionally focused couple therapist: The workbook. New York: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Denton W. Emotionally focused couple therapy: Creating secure connections. In: Gurman AS, Jacobson NS, editors. Clinical handbook of couple therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Greenberg LS. Differential effects of experiential and problem-solving interventions in resolving marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:175–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Paulus MP. The role and clinical significance of subsyndromal depressive symptoms (SSD) in unipolar major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;45:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Paulus MJ, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Endicott J, Leon AC, et al. Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1501–1504. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Martin NC, Liu T, Dolbin-MacNab ML. Multi-level modeling in the context of family research. In: Sprenkle DH, Piercy FP, editors. Research methods in family therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 405–431. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, Arnow B, Dunner DL, Gelenberg AJ, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough JP. Treatment for chronic depression: Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Prusoff BA, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Marital adjustment in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1985;9:5–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Keitner GI, Schatzberg AF, Klein DN, Thase ME, Rush AJ, et al. The treatment of chronic depression, part 3: Psychosocial functioning before and after treatment with sertraline or imipramine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:608–619. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Múthen LK, Múthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5th Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Múthen & Múthen; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A. Residual symptoms after partial remission: An important outcome in depression. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:1171–1180. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perls F, Hefferline R, Goldman P. Gestalt therapy. New York: Dell; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin A, Schulterbrandt J, Reatig N, McKeon JJ. Replication of factors of Psychopathology in interview, ward behavior, and self-report ratings of hospitalized depressives. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1969;148:87–98. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimherr FW, Strong RE, Marchant BK, Hedges DW, Wender PH. Factors affecting return of symptoms 1 year after treatment in a 62-week controlled study of fluoxetine in major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Herceg-Baron RL. Marital disputes and treatment outcome in depressed women. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1979;20:483–490. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(79)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ. Limitations in efficacy of antidepressant monotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm WR, Paffbergen LA, Hatch RC, Obiorah FC, Copeland JM, Meens LD, et al. Concurrent and Discriminant Validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Whitton SW. Communication, conflict, and commitment: Insights on the foundations of relationship success from a national survey. Family Process. 2002;41:659–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suehs B, Argo TR, Bendele SD, Crismon ML, Trivedi MH, Kurian B. [Retrieved August 31, 2009];Texas Medication Algorithm Project procedural manual: Major depressive disorder algorithms. 2008 from http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/pdf/TIMA_MDD_Manual_080608.pdf.

- Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Luther JF, et al. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:739–752. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, Reynolds CF, III, Pilkonis PA, Hurley K, et al. Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1009–1015. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Jarrett RB. Improvement in social-interpersonal functioning after cognitive therapy for recurrent depression. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:643–658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Kraft D, Jarrett RB. Multiple measures, methods, and moments: A factor-analytic investigation of change in depressive symptoms during acute-phase cognitive therapy for depression. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:693–704. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JG, Johnson S, Manion I, Cloutier P. Emotionally focused marital intervention for couples with chronically ill children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1029–1036. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. The association between depression and marital dissatisfaction. In: Beach SRH, editor. Marital and family processes in depression: A scientific foundation for clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001a. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital adjustment and outcome following treatments for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001b;69:125–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Bruce ML. Marital dissatisfaction and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:674–678. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA. Integrating couple therapy with individual therapies and antidepressant medications in the treatment of depression. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 1999;6:415–429. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Coryell W, Corenthal C, Wilson S. A self-report scale to diagnose Major Depressive Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:1076–1081. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800110062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]