Abstract

The SNARE (Soluble NSF Attachment protein REceptor) complex, which in mammalian neurosecretory cells is composed of the proteins synaptobrevin 2 (also called VAMP2), syntaxin, and SNAP-25, plays a key role in vesicle fusion. In this review, we discuss the hypothesis that, in neurosecretory cells, fusion pore formation is directly accomplished by a conformational change in the SNARE complex via movement of the transmembrane domains.

The SNARE Complex

The mechanisms of vesicle fusion are of ubiquitous importance in cell biology and neuroscience. Such fusion events mediate intracellular trafficking, viral infection, and exocytotic secretion of neurotransmitters, hormones, and many other mediators from a wide variety of cell types. This release occurs from the interior of the secretory vesicle to the outside of the cell via formation of a fusion pore. The mechanism by which this fusion pore is formed is still very poorly understood. The neuronal soluble NSF attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex (49) has three components. The v-SNARE synaptobrevin 2 (syb2 also called VAMP2) is a 116-amino acid protein anchored in the vesicle membrane by a single transmembrane (TM) domain. Syntaxin (stx) is correspondingly anchored in the plasma membrane via a single TM helix. The third component, SNAP-25, has lipid anchors in the plasma membrane. SNAP-25 and stx are called t-SNAREs, being in the target membrane for fusion of secretory vesicles. The key importance of these proteins in the fusion mechanism has been demonstrated by the finding that proteolytic cleavage of the SNARE proteins by specific neurotoxins results in strong inhibition of transmitter release in neurons as well as in chromaffin cells (42, 44). One example for the medical relevance of the SNARE complex is the BoTox treatment, which exerts its function through inhibition of transmitter release by specific cleavage of the SNARE protein SNAP-25.

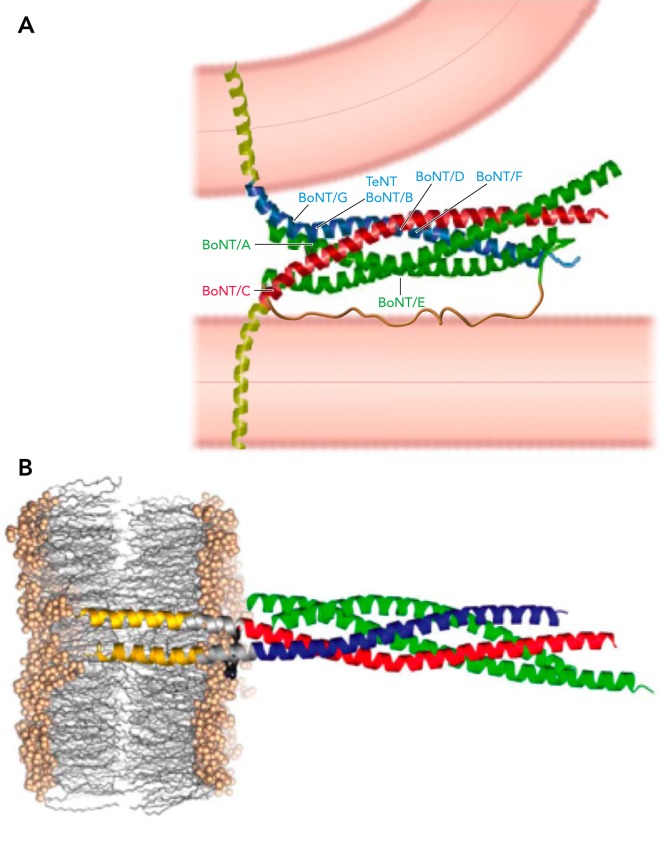

The cytosolic so-called SNARE domains of these three proteins form a coiled coil, which incorporates one helix each from syb2 and stx and two helices (named SN1 and SN2) from SNAP-25. The coiled coil structure of the SNARE domains has been solved by X-ray crystallography several years ago (57). Based on this structure, the configuration shown in FIGURE 1A was proposed for a trans configuration, in which a SNARE complex links the vesicle membrane and plasma membrane. The arrows indicate the cleavage sites for the neurotoxins mentioned above. More recently, a crystal structure of the SNARE complex, including the syb2 and stx TM helices, was solved (56), which shows helical extension from the SNARE domains through the linkers into the TM domains (FIGURE 1B). This structure is thought to resemble a post-fusion state in which all components of the SNARE complex are in a cis configuration, located in the same fused membrane.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the SNARE complex

A: hypothetical model for the structure of the trans SNARE complex as suggested by Ref. 57. The TM domains (yellow) and the SNAP-25 linker (brown) were not part of the crystal structure. B: structure of the post fusion cis SNARE complex, including the TM domains of syb2 and stx, shows helical extension of the SNARE domains into the membrane (56). Figure adapted from Refs. 56 and 57 and used with permission from Nature.

Synaptic vesicles contain ∼70 copies of syb2 (59), but it is unknown and controversial how many of these copies are acting together in the formation of a fusion pore (43). Interestingly, neurosecretory vesicles in PC 12 cells recruit t-SNARE clusters containing a similar number of stx and SNAP-25 molecules (26). It has been shown that in reconstituted systems a single SNARE complex is sufficient to promote lipid vesicle fusion (50, 62). However, at least three SNARE complexes appear to be required for fast membrane fusion kinetics (8, 17, 41, 50). In cultured hippocampal neurons, two copies of syb2 were found to be sufficient for fusion, but the experiments were performed with low time resolution (52).

The Triggering Mechanism

Transmitter release from neurosecretory vesicles is triggered by intracellular Ca2+ ions, and vesicles in the primed state are able to undergo fusion with rapid kinetics in response to stimulation. There is very strong evidence that assembly of the primed state and triggering of rapid fusion are mediated by the proteins synaptotagmin 1 and complexin (12, 37, 47, 53, 60). Synaptotagmin 1 is anchored in the vesicle membrane by a single transmembrane helix, which is connected to a C2A domain through a flexible linker. Another linker connects the C2A domain to its C2B domain (46). The C2 domains bind multiple Ca2+ ions and negatively charged lipids, which also contribute to the Ca2+ binding (5). Complexin is a small cytosolic protein that interacts with the SNARE complex (39).

It is widely believed that, in the primed state, the SNARE complex is assembled in the NH2-terminal part of the SNARE domains, whereas COOH terminal zippering is inhibited (55), possibly through an interaction of the SNARE complex with complexin (30, 33). Structural data suggested that complexin may interact with one SNARE complex via its central helix, whereas its accessory helix interacts with the COOH-terminal part of a second SNARE complex, thereby cross-linking two SNARE complexes. It has been suggested that this cross-linked structure clamps fusion, preventing COOH-terminal zippering of the SNARE complex (30). The clamping of fusion by complexin can then be removed in response to Ca2+ binding by synaptotagmin (28, 37). The vectorial assembly of the SNARE complex, which proceeds from the NH2 terminus to the COOH terminus toward the membranes (23, 54, 55, 65), can now generate a force that is transferred to the apposed membranes, leading to fusion pore formation.

Although there is wide consensus that synaptotagmin 1 is the Ca2+ sensor for triggering of fusion, the mechanism of synaptotagmin function is controversial. Alternative to a function of disinhibition of COOH-terminal zippering as described above, it has been suggested that synaptotagmin promotes fusion by inducing membrane curvature through the shape of its C2 domains (19, 38). Independent of Ca2+, the C2B domain binds to PI(4,5)P2 that is concentrated in t-SNARE clusters on the plasma membrane through the cationic charges of syntaxin's juxtamembrane domain (3, 18, 24). A recent study suggested that this mechanism may be essential for vesicle docking and that Ca2+ binding to the C2B domain may promote simultaneous binding of the C2B domain to phosphatidylserine on the vesicle membrane, pulling the membranes closer together (18). This finding supports the hypothesis that the formation of a trans SNARE complex is enabled only after arrival of the Ca2+ stimulus by cross-linking the vesicle and plasma membranes via the C2B domain (22, 63).

The Force Generation and Force Transfer

The energy barrier for fusion of lipid vesicles is very high, and only very rough estimates exist. Due to this energy barrier, fusion of vesicles is an extremely slow process. It has been estimated that energies roughly in the range of ∼15–50 kBT must be provided by a protein machinery to lower the activation energy such that fusion can occur on a physiological millisecond time scale (14, 27, 51). This energy is likely provided by one or more SNARE complexes and possibly the interaction of synaptotagmin with the membranes. The energy from SNARE complex assembly must be transferred to the membrane via the generation of corresponding forces. The forces that zippering of the SNARE complex could produce have been investigated in a few experiments. Force spectroscopy experiments performed on the SNARE complex yielded rupture forces of ∼250 pN (36), but this value depends on the loading rate. Very recently, optical tweezers were applied to determine the forces and energies of SNARE complex zippering (11). These experiments suggested that zippering of a single SNARE complex may output a free energy of ∼65 kBT. The contributions from the COOH-terminal half of the SNARE domains and those from the linkers connecting the SNARE domains of syb2 and stx to the TM domains were found to be 28 kBT and 8 kBT, respectively, with estimates for the respective maximum force output in the COOH-terminal and linker domain zippering stages of ∼17 pN and ∼12 pN (11). In similar experiments using magnetic tweezers, COOH-terminal unzipping was observed in the same force range (40).

When a force is generated by zippering of the COOH-terminal part of the SNARE complex that pulls the two membranes further together and if this force is doing work to overcome the energy barrier of membrane fusion, then the force transfer must occur via the syb2 and stx TM domains in the vesicle and plasma membrane, generating the structural changes that lead to fusion pore formation. The relation between a force acting on the syb2 TM domain and its position in the membrane has recently been investigated in coarse-grain molecular dynamics simulations (35). From these simulations, the activation energy for tilting the syb2 TM domain through the membrane from its prefusion transmembrane orientation to a position parallel to the membrane plane in the cytoplasmic membrane-water interface was estimated to be ∼27 kBT. It therefore appears that generation of the energy by COOH-terminal SNARE complex zippering will lead to considerable changes in syb2 TM domain orientation.

The COOH-Terminal Part of the SNARE Complex Determines Fusion Pore Properties

The molecular mechanism of fusion pore formation is still highly controversial. In the lipid-stalk-hemifusion hypothesis, the outer and the inner leaflets of the two membranes merge via formation of a hemifusion intermediate in response to forces exerted by proteins surrounding the fusion site (71). An alternative proteinaceous fusion pore model was proposed where the fusion pore is lined by several TM domains of stx (17) and possibly syb2 (21). However, the TM domains of syb2 and stx are hydrophobic, and it is unclear how an aqueous fusion pore, through which transmitter molecules and inorganic ions permeate by electrodiffusion (13), could be formed between them.

When the COOH-terminal SNARE domain interactions are reduced by mutating or deleting the COOH terminus of SNAP-25, or when flexible linkers are introduced between the syb2 TM domain and its SNARE domain, the rate of exocytosis is reduced (6, 7, 25, 67, 69) and the flux of transmitter through the early fusion pore is decreased (9, 25). Chromaffin cells expressing the SNAP-25 mutant named SNAP-25Δ9 (lacking the last nine COOH-terminal residues) display smaller amperometric “foot-current” currents, reduced fusion pore conductances, and lower fusion pore expansion rates. These results suggested that SNARE complexes involving the SNAP-25Δ9 mutant produce a lower force, are less tightly zipped, and therefore generate structurally different fusion pores. These mutant fusion pores are presumably longer, consistent with the observed decrease of fusion pore conductance (9). Based on these findings, a proteolipidic fusion pore structure was proposed that is formed by a molecular complex of both lipids and SNARE proteins (9).

At the extravesicular end of the syb2 TM domain, there are two tryptophans (W89/W90). When these are mutated to alanines in the W89A/W90A double mutant [also named WA mutant (37)], catecholamine release from chromaffin cells measured by carbon fiber amperometry showed a higher flux of catecholamine through the initial fusion pore as well as through the expanded fusion pore (10). From these results, it may be concluded that fusion pores formed by SNARE complexes involving the WA mutant are initially wider or shorter and subsequently expand more readily. Unexpectedly, the number of catecholamine molecules released per vesicle from syb2 WA-expressing chromaffin cells was considerably increased, indicating increased quantal size, although vesicle size measured by capacitance measurements and total transmitter stored per vesicle were unchanged (10). The larger quantal size from syb2 WA mutant-expressing cells was consistent with complete release of the vesicular contents, suggesting that release mediated by wild-type SNARE complexes may be incomplete with fusion pore closure before the vesicle contents are fully discharged. These results suggest that the TM domain of syb2 may have a direct role in determining early fusion pore structure as well as fusion pore expansion.

The Role of SNARE Protein TM Domains in Fusion

The NH2-to-COOH terminal SNARE complex zippering produces a force that is transferred to the apposed vesicle and plasma membranes via the syb2 and stx TM domains. Evidence for the significance of the TM domains in SNARE-mediated fusion events as well as viral fusion events has come from many studies (reviewed in Ref. 32). It has been suggested that tilting of the TM domains may be an essential step in facilitating membrane fusion pore formation or fusion pore expansion by inducing changes in membrane curvature (20, 61). In the prefusion state, the COOH terminus of the syb2 TM domain is located in the intravesicular membrane water interface (FIGURE 1A).

The ability of syb2 to support exocytosis is inhibited by addition of one or two residues to the syb2 COOH terminus, depending on their energy of transfer from water to the membrane interface (45). These results suggested that, following stimulation, the force transfer generated by the SNARE complex pulls the COOH terminus of syb2 deeper into the vesicle membrane and that such a movement of the syb2 COOH terminus may be a prerequisite for fusion pore formation (45). Evidence that penetration of the COOH terminus into the hydrophobic membrane core triggers fusion pore formation was also obtained in CG-MD simulations of a SNARE complex bridging two membranes (48). To investigate more directly how such mutations may inhibit the movement of the syb2 TM domain in the membrane, coarse-grain molecular dynamics simulations were performed using a model of a COOH-terminal fragment of syb2 comprised of residues Q71-T116 (35). These simulations revealed that application of piconewton forces to the TM helix in the simulation pulls the syb2 COOH terminus deeper into the membrane. The energy for this COOH-terminal movement was increased in the syb2-KK construct, with two lysines added at the COOH terminus, which could explain the experimentally observed inhibition of fusion.

The two tryptophans (W89/W90) of syb2 located at the cytoplasmic end of the syb2 TM domain have a particularly low energy in the membrane water interface (68) and thereby stabilize the syb2 TM domain position. Accordingly, the WA mutant showed a decrease of the energy for the TM domain movement in CG-MD simulations (35). Experimentally, the WA mutant increased the rate of spontaneous fusion events and reduced evoked release in neurons (37). Increased spontaneous release and decreased stimulated release were also observed in chromaffin cells expressing the WA mutant, suggesting that the tryptophans W89/W90 act as a fusion clamp, making release stimulation dependent (10). It therefore appears that the WA mutant allows fusion to occur spontaneously with higher frequency, leaving fewer vesicles in a primed state available for rapid release in response to stimulation. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that fusion is facilitated by a movement of the syb2 TM domain. In another study using chromaffin cells, a marked reduction in rapid release following stimulation was also observed, but an increase in spontaneous events was not detected (4). This apparent discrepancy is still to be resolved.

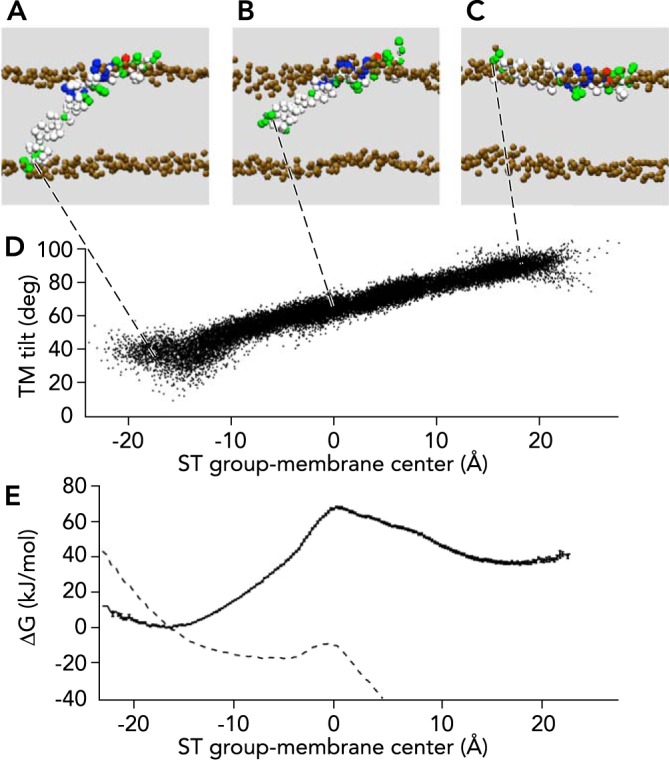

SNARE complex zippering will bring about fusion of the membranes in a transition from a trans state (FIGURE 1A) to a cis state (FIGURE 1B). The syb2 TM domain movement during this transition will likely occur in a tilting motion. Such a tilting motion of the syb2 TM domain through the membrane could be produced in CG-MD simulations by application of forces to the COOH-terminal end of the TM domain (FIGURE 2). The activation energy of tilting the TM domain from the transmembrane orientation (FIGURE 2A) to an orientation parallel to the membrane on the membrane-water interface (FIGURE 2C) was estimated to be ∼27 kBT (FIGURE 2E). Applying a constant 80-pN force to the syb2 COOH terminus lowered the energy barrier to ∼3 kBT (FIGURE 2E, dashed line), and in the simulation this barrier was overcome in ∼300 ns. Based on this result, the energy barrier that would allow the tilting process to occur on the physiological time scale of fusion (∼1 ms) can be estimated (in units of kBT) as

FIGURE 2.

Energetics of syb2 tilting movement in the membrane

Harmonic potentials were applied to S115/T116 (ST group) in state (A), generating directional movement through the hydrophobic core (B) to the extravesicular membrane-water interface (C). D: the change of the ST group position is accompanied by a corresponding change of the TM domain tilt angle. E: the free energy profile shows a maximum when the COOH terminus is located near the membrane center (black dots with error bars). The energy barrier is lowered to ∼3 kBT when an 80-pN force is applied in z direction (broken line). Image adapted from Ref. 35 and used with permission.

This estimate suggests that the SNARE complex zippering needs to lower the activation energy by ∼16 kBT to enable the tilting motion of the syb2 TM domain with a time constant of ∼1 ms. A similar estimate may be expected for the stx TM domain. As mentioned before, experiments measuring the forces and energies of SNARE complex zippering using optical tweezers (11) indicate that the COOH-terminal SNARE complex zippering may output a free energy of ∼28 kBT, which may be close to the value needed to obtain ms kinetics for tilting both the syb2 and the stx TM domains through the membranes.

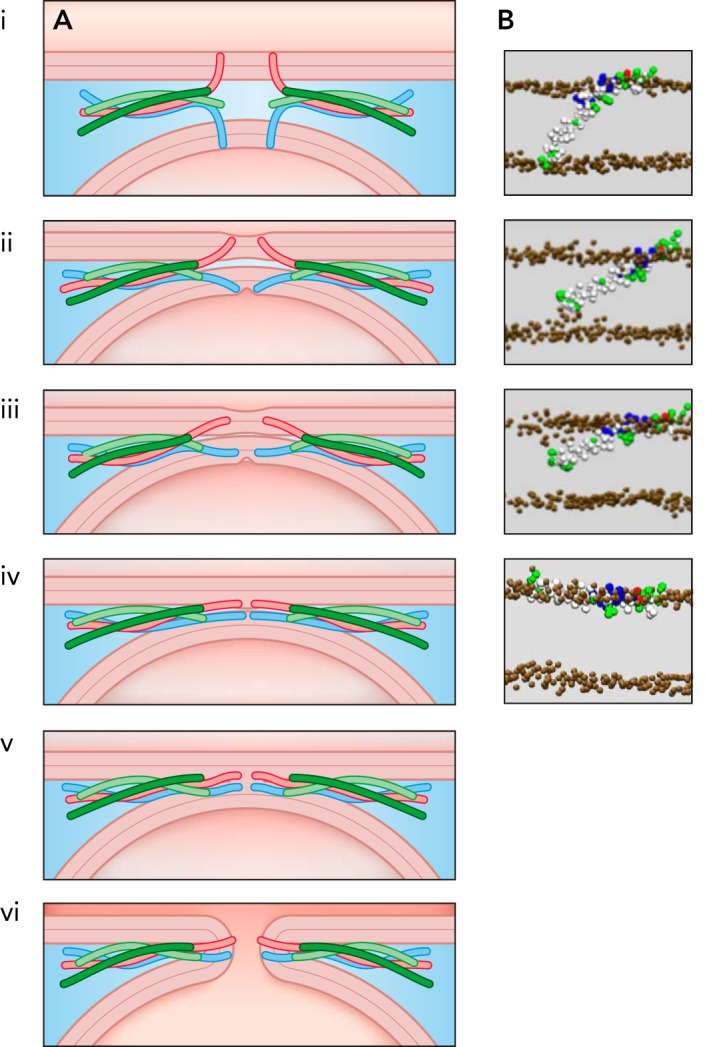

The Mechanism by Which the Force Transfer Leads to Fusion Pore Formation

Based on the experimental results and computational studies, the hypothesis for the molecular mechanism of SNARE-mediated fusion pore opening illustrated in FIGURE 3 has been proposed (35). In this model, fusion pore formation is induced by movement of the charged syb2 COOH terminus within the membrane in response to pulling and tilting forces generated by COOH-terminal zippering of the SNARE complex. From the prefusion state (state i), the SNARE complex pulls the membranes together while the COOH termini of syb2 and presumably syntaxin maintain contact with the exoplasmic membrane leaflet lipid head groups (state ii). Once the COOH termini are detached, they move toward the endoplasmic leaflets (state iii). Rearrangement of the lipids leading to fusion pore formation could be induced directly in state iii, as suggested by CG-MD simulations (48).

FIGURE 3.

Model of TM domain movements

Model of TM domain movements leading to fusion pore formation (A) and corresponding states of the syb2 TM domain from CG-MD simulations (35). The zippering of the SNARE complex will lead to helical extension, leading to force transfer and TM domain, tilt as indicated in states i–iv. Fusion pore formation (state vi) could proceed via the stalk state (state v) or could be induced via the transition from state iii to iv. Image adapted from Ref. 35 and used with permission.

The model of FIGURE 3 proposes an alternative role for the syb2 TM domain that is reminiscent of the role of the hemagglutinin fusion peptide in viral fusion. The viral fusion peptide becomes exposed in response to a decrease in pH and inserts into the apposed leaflet of the endosomal membrane in an inverted V- or boomerang-shaped conformation but essentially parallel to the membrane with a shallow tilt angle (16). It is thought that formation of a fusion pore proceeds from this state with the fusion peptide located between viral and endosomal membrane (15, 34). In the model of FIGURE 3, syb2 and syntaxin assume an extended state parallel to the membranes in state iv, and the TM domains come into contact between the membranes, thereby linking the two membranes. FIGURE 2 shows the energy landscape for TM domain tilting. If forces from SNARE complex zippering can lower the energy of the parallel state such that the state iv is assumed, this is not a low-energy state for the TM domains. A rearrangement of the lipids around the TM domains that leads to a fusion pore reestablishes a low-energy transmembrane orientation of the TM domains (state vi). In this model, the formation of the fusion pore is thus driven by lowering the energy of the TM domains. It has been shown that synthetic SNARE TM domain peptides can act as fusion peptides and drive liposome fusion depending on their conformational flexibility (31). It seems possible that, in such systems, fusion may be mediated by a small population of peptides that translocate to the vesicle surface and can thereby link and fuse the membranes of two vesicles. Alternatively, from state iv, fusion pore formation may occur via a stalk intermediate (state v). Such an intermediate will be unstable due to penetration of the charged syb2 COOH terminus into the hydrophobic membrane core (48), which could trigger fusion pore formation (state vi).

The hypothesis for the fusion mechanism shown in FIGURE 3 is consistent with a large body of experimental findings. Its validity may be tested by comparing the predictions from molecular dynamics simulations with experimental data that show how specific mutations in the syb2 and stx TM domains, the linker regions, and the COOH-terminal part of the SNARE domains affect SNARE complex force generation, the energy of tilting the TM domain through the membrane, and fusion pore formation. However, more direct methods are needed to determine the precise conformational changes in the SNARE complex that lead to fusion pore formation. One method to probe protein conformational changes utilizes fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). In this approach, a FRET donor and a FRET acceptor are incorporated into the protein. For FRET, the emission spectrum of the donor needs to overlap with the absorption spectrum of the acceptor, and the distance between donor and acceptor must be sufficiently small, on the order of a few nanometers. Under these conditions, excitation of the donor leads to fluorescence emission from the acceptor with reduced emission from the donor. The FRET efficiency changes when the distance and/or relative orientation between donor and acceptor change. The fluorescent proteins YFP and CFP (and their derivatives with similar spectra) form a suitable FRET pair and have been incorporated at the NH2-terminal ends of the SNAP-25 SNARE domains (2, 58, 66). Such constructs report formation and conformational changes of the SNARE complex.

In a recent study, imaging of FRET changes using such a FRET-based SNARE complex reporter was combined with electrochemical detection of single fusion events at high time resolution. These experiments revealed a rapid conformational change in SNAP-25 that occurred specifically at the sites of fusion events and preceded fusion pore formation by ∼90 ms (70). This FRET change may result from the formation of trans SNARE complexes that form after cross-linking the vesicle and plasma membranes via the synaptotagmin C2B domain, as recently proposed (22, 63). Alternatively, it could reflect structural changes in preformed trans SNARE complexes that occur in response to stimulation. The development of new fluorescence probes that could monitor movements of the TM domains of syb2 and stx could provide more direct evidence regarding their role in fusion pore formation. However, GFP-derived tags would be much too bulky for such experiments. One approach using a much smaller fluorescent tag involves fluorescent labeling of SNAREs with the biarsenical dye FlAsH using the tetracysteine system (1, 64). Recent progress in the incorporation of fluorescent unnatural amino acids in proteins expressed in mammalian cells (29) suggests that this method may be another possible tool to provide more detailed insight into the conformational changes of the SNARE complex that lead to fusion pore formation. These may also be able to provide direct evidence regarding the controversy if a stable, primed trans SNARE complex exists.

Footnotes

We are grateful for support from National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant No. R01 GM-085808) and the European Research Council (Advanced Grant No. 322699).

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Author contributions: Q.F. and M.L. interpreted results of experiments; Q.F. and M.L. edited and revised manuscript; Q.F. and M.L. approved final version of manuscript; M.L. prepared figures; M.L. drafted manuscript.

References

- 1.Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, Llopis J, Tsien RY. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications. J Am Chem Soc 124: 6063–6076, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An SJ, Almers W. Tracking SNARE complex formation in live endocrine cells. Science 306: 1042–1046, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyagi K, Sugaya T, Umeda M, Yamamoto S, Terakawa S, Takahashi M. The activation of exocytotic sites by the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate microdomains at syntaxin clusters. J Biol Chem 280: 17346–17352, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borisovska M, Schwarz YN, Dhara M, Yarzagaray A, Hugo S, Narzi D, Siu SWI, Kesavan J, Mohrmann R, Bockmann RA, Bruns D. Membrane-proximal tryptophans of synaptobrevin II stabilize priming of secretory vesicles. J Neurosci 32: 15983–15997, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brose N, Petrenko AG, Südhof TC, Jahn R. Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science 256: 1021–1025, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criado M, Gil A, Viniegra S, Gutierrez LM. A single amino acid near the C terminus of the synaptosomeassociated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) is essential for exocytosis in chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7256–7261, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deak F, Shin OH, Kavalali ET, Sudhof TC. Structural determinants of synaptobrevin 2 function in synaptic vesicle fusion. J Neurosci 26: 6668–6676, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domanska MK, Kiessling V, Tamm LK. Docking and fast fusion of synaptobrevin vesicles depends on the lipid compositions of the vesicle and the acceptor SNARE complex-containing target membrane. Biophys J 99: 2936–2946, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Q, Berberian K, Gong LW, Hafez I, Sorensen JB, Lindau M. The role of the C terminus of the SNARE protein SNAP-25 in fusion pore opening and a model for fusion pore mechanics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15388–15392, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang Q, Zhao Y, Lindau M. Juxtamembrane tryptophans of synaptobrevin 2 control the process of membrane fusion. FEBS Lett 587: 67–72, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Y, Zorman S, Gundersen G, Xi Z, Ma L, Sirinakis G, Rothman JE, Zhang Y. Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science 337: 1340–1343, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79: 717–727, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong LW, de Toledo GA, Lindau M. Exocytotic catecholamine release is not associated with cation flux through channels in the vesicle membrane but Na+ influx through the fusion pore. Nat Cell Biol 9: 915–922, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grafmuller A, Shillcock J, Lipowsky R. The fusion of membranes and vesicles: pathway and energy barriers from dissipative particle dynamics. Biophys J 96: 2658–2675, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton BS, Whittaker GR, Daniel S. Influenza virus-mediated membrane fusion: determinants of hemagglutinin fusogenic activity and experimental approaches for assessing virus fusion. Viruses 4: 1144–1168, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X, Bushweller JH, Cafiso DS, Tamm LK. Membrane structure and fusion-triggering conformational change of the fusion domain from influenza hemagglutinin. Nat Struct Biol 8: 715–720, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han X, Wang CT, Bai J, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Science 304: 289–292, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honigmann A, van den Bogaart G, Iraheta E, Risselada HJ, Milovanovic D, Mueller V, Mullar S, Diederichsen U, Fasshauer D, Grubmuller H, Hell SW, Eggeling C, Kuhnel K, Jahn R. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate clusters act as molecular beacons for vesicle recruitment. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 679–686, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui E, Johnson CP, Yao J, Dunning FM, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin-mediated bending of the target membrane is a critical step in Ca2+-regulated fusion. Cell 138: 709–721, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson MB. SNARE complex zipping as a driving force in the dilation of proteinaceous fusion pores. J Membr Biol 235: 89–100, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Fusion pores and fusion machines in Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35: 135–160, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature 490: 201–207, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahn R, Hanson PI. Membrane fusion. SNAREs line up in new environment. Nature 393: 14–15, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James DJ, Khodthong C, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TF. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. J Cell Biol 182: 355–366, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kesavan J, Borisovska M, Bruns D. v-SNARE actions during Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Cell 131: 351–363, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowles MK, Barg S, Wan L, Midorikawa M, Chen X, Almers W. Single secretory granules of live cells recruit syntaxin-1 and synaptosomal associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) in large copy numbers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 20810–20815, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlovsky Y, Kozlov MM. Stalk model of membrane fusion: solution of energy crisis. Biophys J 82: 882–895, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnakumar SS, Radoff DT, Kummel D, Giraudo CG, Li F, Khandan L, Baguley SW, Coleman J, Reinisch KM, Pincet F, Rothman JE. A conformational switch in complexin is required for synaptotagmin to trigger synaptic fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 934–940, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger AT, Imperiali B. Fluorescent amino acids: modular building blocks for the assembly of new tools for chemical biology. Chem Biol Chem 14: 788–799, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kummel D, Krishnakumar SS, Radoff DT, Li F, Giraudo CG, Pincet F, Rothman JE, Reinisch KM. Complexin cross-links prefusion SNAREs into a zigzag array. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 927–933, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langosch D, Crane JM, Brosig B, Hellwig A, Tamm LK, Reed J. Peptide mimics of SNARE transmembrane segments drive membrane fusion depending on their conformational plasticity. J Mol Biol 311: 709–721, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langosch D, Hofmann M, Ungermann C. The role of transmembrane domains in membrane fusion. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 850–864, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Pincet F, Perez E, Giraudo CG, Tareste D, Rothman JE. Complexin activates and clamps SNAREpins by a common mechanism involving an intermediate energetic state. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 941–946, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Han X, Lai AL, Bushweller JH, Cafiso DS, Tamm LK. Membrane structures of the hemifusion-inducing fusion peptide mutant G1S and the fusion-blocking mutant G1V of influenza virus hemagglutinin suggest a mechanism for pore opening in membrane fusion. J Virol 79: 12065–12076, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindau M, Hall BA, Chetwynd A, Beckstein O, Sansom MSP. Coarse-grain simulations reveal movement of the synaptobrevin C-terminus in response to piconewton forces. Biophys J 103: 959–969, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu W, Montana V, Bai J, Chapman ER, Mohideen U, Parpura V. Single molecule mechanical probing of the SNARE protein interactions. Biophys J 91: 744–758, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maximov A, Tang J, Yang X, Pang ZP, Sudhof TC. Complexin controls the force transfer from SNARE complexes to membranes in fusion. Science 323: 516–521, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMahon HT, Kozlov MM, Martens S. Membrane curvature in synaptic vesicle fusion and beyond. Cell 140: 601–605, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMahon HT, Missler M, Li C, Sudhof TC. Complexins: cytosolic proteins that regulate SNAP receptor function. Cell 83: 111–119, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min D, Kim K, Hyeon C, Cho YH, Shin YK, Yoon TY. Mechanical unzipping and rezipping of a single SNARE complex reveals hysteresis as a force-generating mechanism. Nat Commun 4: 1705, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohrmann R, de Wit H, Verhage M, Neher E, Sorensen JB. Fast vesicle fusion in living cells requires at least three SNARE complexes. Science 330: 502–505, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. Mechanism of action of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Mol Microbiol 13: 1–8, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montecucco C, Schiavo G, Pantano S. SNARE complexes and neuroexocytosis: how many, how close? Trends Biochem Sci 30: 367–372, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan A, Burgoyne RD. Common mechanisms for regulated exocytosis in the chromaffin cell and the synapse. Semin Cell Dev Biol 8: 141–149, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ngatchou AN, Kisler K, Fang Q, Walter AM, Zhao Y, Bruns D, Sorensen JB, Lindau M. Role of the synaptobrevin C terminus in fusion pore formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18463–18468, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perin MS, Fried VA, Mignery GA, Jahn R, Südhof TC. Phospholipid binding by a synaptic vesicle protein homologous to the regulatory region of protein kinase C. Nature 345: 260–263, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reim K, Mansour M, Varoqueaux F, McMahon HT, Südhof TC, Brose N, Rosenmund C. Complexins regulate a late step in Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Cell 104: 71–81, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Risselada HJ, Kutzner C, Grubmuller H. Caught in the act: visualization of SNARE-mediated fusion events in molecular detail. Chem Biol Chem 12: 1049–1055, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothman JE. The protein machinery of vesicle budding and fusion. Protein Sci 5: 185–194, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi L, Shen QT, Kiel A, Wang J, Wang HW, Melia TJ, Rothman JE, Pincet F. SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science 335: 1355–1359, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel DP. The Gaussian curvature elastic energy of intermediates in membrane fusion. Biophys J 95: 5200–5215, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinha R, Ahmed S, Jahn R, Klingauf J. Two synaptobrevin molecules are sufficient for vesicle fusion in central nervous system synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 14318–14323, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sorensen JB, Fernandez-Chacon R, Sudhof TC, Neher E. Examining synaptotagmin 1 function in dense core vesicle exocytosis under direct control of Ca2+. J Gen Physiol 122: 265–276, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sorensen JB, Nagy G, Varoqueaux F, Nehring RB, Brose N, Wilson MC, Neher E. Differential control of the releasable vesicle pools by SNAP-25 splice variants and SNAP-23. Cell 114: 75–86, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sorensen JB, Wiederhold K, Muller EM, Milosevic I, Nagy G, de Groot BL, Grubmuller H, Fasshauer D. Sequential N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly drives priming and fusion of secretory vesicles. EMBO J 25: 955–966, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stein A, Weber G, Wahl MC, Jahn R. Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature 460: 525–528, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 395: 347–353, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Okado H, Noguchi J, Ohno M, Kasai H. SNARE conformational changes that prepare vesicles for exocytosis. Cell Metab 12: 19–29, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Gronborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brugger B, Ringler P, Muller SA, Rammner B, Grater F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmuller H, Heuser J, Wieland F, Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell 127: 831–846, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang J, Maximov A, Shin OH, Dai H, Rizo J, Sudhof TC. A complexin/synaptotagmin 1 switch controls fast synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell 126: 1175–1187, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong J, Borbat PP, Freed JH, Shin YK. A scissors mechanism for stimulation of SNARE-mediated lipid mixing by cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5141–5146, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Bogaart G, Holt MG, Bunt G, Riedel D, Wouters FS, Jahn R. One SNARE complex is sufficient for membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 358–364, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van den Bogaart G, Thutupalli S, Risselada JH, Meyenberg K, Holt M, Riedel D, Diederichsen U, Herminghaus S, Grubmuller H, Jahn R. Synaptotagmin-1 may be a distance regulator acting upstream of SNARE nucleation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 805–812, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varlamov O. Detection of SNARE complexes with FRET using the tetracysteine system. Bio Techniques 52: 103–108, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walter AM, Wiederhold K, Bruns D, Fasshauer D, Sorensen JB. Synaptobrevin N-terminally bound to syntaxin-SNAP-25 defines the primed vesicle state in regulated exocytosis. J Cell Biol 188: 401–413, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang L, Bittner MA, Axelrod D, Holz RW. The structural and functional implications of linked SNARE motifs in SNAP25. Mol Biol Cell 19: 3944–3955, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wei S, Xu T, Ashery U, Kollewe A, Matti U, Antonin W, Rettig J, Neher E. Exocytotic mechanism studied by truncated and zero layer mutants of the C-terminus of SNAP-25. EMBO J 19: 1279–1289, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wimley WC, White SH. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat Struct Biol 3: 842–848, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu T, Binz T, Niemann H, Neher E. Multiple kinetic components of exocytosis distinguished by neurotoxin sensitivity. Nat Neurosci 1: 192–200, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao Y, Fang Q, Herbst AD, Berberian KN, Almers W, Lindau M. Rapid structural change in synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25) precedes the fusion of single vesicles with the plasma membrane in live chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 14249–14254, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zimmerberg J, Vogel SS, Chernomordik LV. Mechanisms of membrane fusion. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 22: 433–466, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]