Abstract

MYH7 mutations are an established cause of Laing distal myopathy, myosin storage myopathy, and cardiomyopathy, as well as additional myopathy subtypes. We report a novel MYH7 mutation (p.Leu1597Arg) that arose de novo in two unrelated probands. Proband 1 has a myopathy characterized by distal weakness and prominent contractures and histopathology typical of multi-minicore disease. Proband 2 has an axial myopathy and histopathology consistent with congenital fiber type disproportion. These cases highlight the broad spectrum of clinical and histological patterns associated with MYH7 mutations, and provide further evidence that MYH7 is likely responsible for a greater proportion of congenital myopathies than currently appreciated.

Keywords: Congenital myopathies, MYH7, Laing distal myopathy, Axial myopathy

Introduction

MYH7 encodes slow/β-cardiac myosin heavy chain, a class II myosin found in cardiac and type I skeletal myofibers [1]. It is a critical component of the force generation apparatus in both heart and skeletal muscle. Mutations in MYH7 are an established cause of cardiomyopathy [2] and of an expanding range of skeletal myopathies that includes Laing distal myopathy [3,4], myosin storage myopathy [5–8], congenital fiber type disproportion (CFTD) [9,10], myopathy with serpiginous cytoplasmic bodies and myofibrillar changes [11], and core myopathy (including multi-minicore disease) [12,13]. Mostly these disorders follow autosomal dominant inheritance although a family with autosomal recessive myosin storage has been reported [14]. Mutations for the different disorders cluster in different parts of the protein with some overlap. For example, most cardiomyopathy mutations are located in the myosin head and neck domains [15] while skeletal myopathy mutations are usually in the distal regions of the rod domain [16].

Until recently, MYH7 has been an uncommon cause of skeletal myopathy, associated with a narrow range of clinical and histological phenotypes. Recent case reports link MYH7 mutations to several new histological and clinical patterns of disease [9–11,17,18], and it is possible that mutations in MYH7 may be responsible for a significant proportion of a wide range of skeletal myopathies. We present two new cases that support this hypothesis. These two unrelated patients have a previously unreported MYH7 mutation (p.Leu1597Arg) and have strikingly different clinical and histological presentations. These cases thus broaden the known spectrum of MYH7 myopathy and also show that the same mutation can cause highly variable clinical and histological phenotypes that include axial myopathy and multiminicore disease.

Case report

Case 1

This female patient (currently age 32 years old) has prominent and multiple joint contractures and generalized weakness that is most notable in the distal musculature. She presented with toe walking at age 2 years and required multiple Achilles tendon lengthening surgeries between ages 11–14 years. From age 19 years she developed progressive weakness and contractures. At age 32 years, she could walk only short distances and had prominent contractures of the finger flexors (Fig 1A), neck flexors, and tendo-Achilles. There was marked weakness of neck flexion, shoulder abduction, hip flexion and ankle dorsiflexion and moderate weakness of wrist/hand flexors and mild weakness of knee flexion/extension. Facial and ocular muscle function was normal.

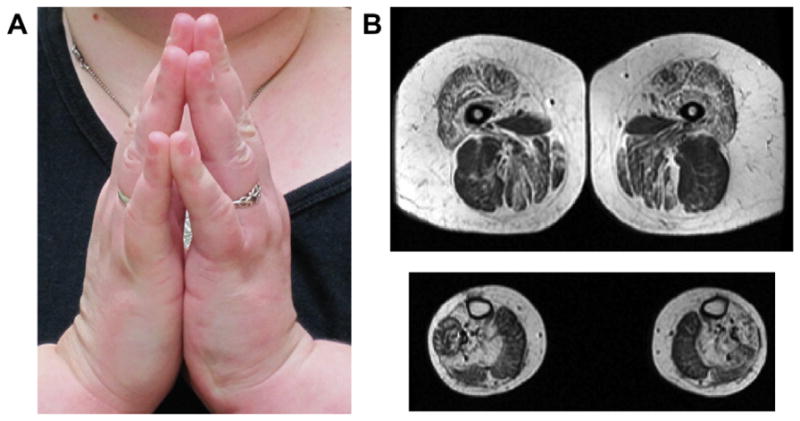

Fig. 1.

Clinical and MRI features of Case 1. (A) Prayer sign, illustrating long finger flexor contractures. (B) Muscle MRI of the thigh (top panel) reveals involvement of many muscles including sartorius, quadriceps, and adductors, with relative sparing of biceps femoris. Muscle MRI of the distal lower extremity shows fatty infiltration in the soleus and lateral gastrocnemius with relative sparing of the medial gastrocnemius.

Electromyography (EMG) showed myopathic features and serum CK was mildly elevated. Cardiac evaluation (via EKG and echocardiogram) was unremarkable. At age 32 years, based on formal pulmonary function testing, she exhibited moderate restrictive lung disease (forced vital capacity [FVC] 63% of predicted). Muscle MRI showed severe fatty replacement in quadriceps and soleus muscles with sparing of biceps femoris and medial gastrocnemius (Fig 1C). A quadriceps muscle biopsy performed at age 11 years showed non-specific myopathic changes while a gastocnemius biopsy performed at age 32 years showed prominent mini-cores, increased internalized nuclei (~40% of fibers), type I fiber predominance, mildly increased endomysial fibrosis and focal fatty replacement (Fig 2). Sanger sequencing was normal for RYR1 (full exonic sequencing), SEPN1, LMNA, and COL6A1/2/3. A heterozygous MYH7 p.Leu1597Arg (c.4790T>G) missense change was detected in the patient and not found in either parent. This change was absent from the NCBI dbSNP database, from the 1000 genomes database (http://www.1000genomes.org/), and from the Exome Variant Server, (NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/).

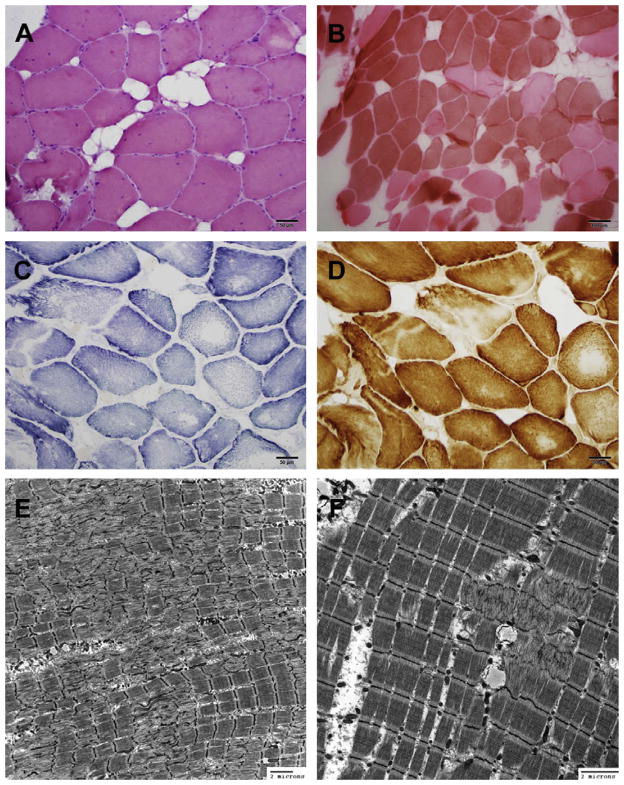

Fig. 2.

Muscle biopsy features of Case 1. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing increased internalized nuclei, variation in fiber size, and focal fatty replacement. (B) ATPase pH 4.2 staining showing type 1 predominance. (C–D) SDH (C), and COX (D) staining show central clearing and absence of staining suggestive of core-like areas. (E–F) Electron micrographs reveal myofibrillar disarray of the sarcomeres with exclusion of mitochondria, ranging from only 4 microns to more than 20 microns in diameter, consistent with the presence of minicores.

Case 2

This female patient (last assessed at age 16 years) has a predominantly axial myopathy phenotype. She presented with toe-walking at age 5 years and required bilateral tendo-Achilles releases at ages 7 and 13 years. A progressive scoliosis required surgical stabilization at age 12 years. At age 13 years neck movements were markedly restricted in all directions except extension, and there were mild flexion contractures at the hips, knees and ankles. There was marked neck flexion weakness, moderate weakness of hip extension and ankle dorsiflexion, and mild weakness of shoulder abduction, hip flexion and knee flexion/extension. While walking her upper body was angled forward, there was external rotation of the feet and mild foot-drop. Of note, the axial involvement in this case largely spares the lumbar musculature and is restricted to the upper thoracic and neck regions.

In terms of diagnostic studies, serum creatine kinase was 308 iu/l (24–215). There was moderate restrictive lung disease (as determined by formal pulmonary function testing) at age 12 years (FVC 55% of predicted). Electromyography, sural nerve biopsy and cardiac investigations (EKG and echocardiogram) were normal. A quadriceps muscle biopsy taken at age 13 years demonstrated congenital fiber type disproportion. There was type 1 fiber predominance (82%), marked type 1 hypotrophy and type 2 fiber hypertrophy (Fig 3A–C). Muscle MRI scan at age 12 years showed selective fatty infiltration of spinalis muscles in the upper thoracic and cervical regions (Fig 3D–I) A heterozygous MYH7 p.Leu1597Arg (c.4790T>G) missense change was found by whole exome sequencing studies, and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This change was absent in parental DNA samples. Unreported heterozygous variants in RYR1 (p.Asn4200Ser), COL6A3 (p.Ser2829Pro) and TTN (p.Gly4604Glu) were also detected, but were all present in a healthy parent. In addition, Sanger sequencing was normal for ACTA1, SEPN1, LMNA, TPM3, TPM2, TNNT1 and MYOZ2.

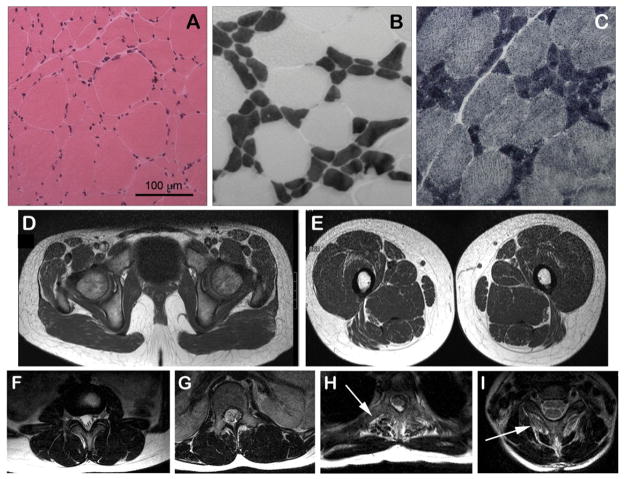

Fig. 3.

Muscle biopsy and muscle MRI images from Case 2. Haematoxylin & eosin stain shows marked fiber size variability with occasional internalized nuclei (A), ATPase (pH 4.2) stain shows typical features of congenital fiber type disproportion (B). Mean diameter of type 1 fibers (dark) was 24.0 μm (normal ~50 μm) and of type 2 fibers (pale) was 83.3 μm (normal ~50 μm). NADH stain shows an absence of cores (C). Muscle MRI shows marked selective fatty infiltration (arrows) of the spinalis muscles of the upper thoracic (H) and cervical (I) spine with only minor fatty marbling of other muscles of the spine in lumbar (F) and lower thoracic (G) regions, pelvis (D) and thighs (E).

Discussion

We present strong evidence that a heterozygous p.Leu1597Arg MYH7 change is the cause of myopathy in two unrelated probands with distinct clinical and histopathological presentations. This evidence includes the fact that the variant is not present in large control datasets and that it arose de novo in both individuals in association with a congenital myopathy phenotype, which is very unlikely to occur by chance. This missense change is located within the light meromyosin (LMM) region, similar to other skeletal myopathy MYH7 mutations [16]. The LMM has been implicated as a mediator of protein– protein interactions between myosin and other known myosin-binding proteins.

The most significant observation to emerge from these cases is the divergent clinical course and histopathological pattern between two unrelated individuals with the same mutation. The most prominent clinical features of Case 1 are progressive joint contractures in the distal upper and lower extremities as well as prominent neck flexor contractures, though with MRI and biopsy features (as well as some clinical features) distinct from either Ullrich CMD or Bethlem myopathy [19,20]. Histopathology showed multi-minicore myopathy. The most striking clinical feature in Case 2 was her axial muscle involvement, and her biopsy revealed congenital fiber type disproportion. Clinical heterogeneity associated with a single mutation has been reported previously for a familial case of myosin storage myopathy due to a pLeu1793Pro mutation, though in this case there was a more extreme difference in clinical severity [18]. Phenotypic variability has also been demonstrated for MYH7 associated cardiomyopathy [21]. One potential theory to explain variable presentation in MYH7 myopathies is that differing phenotypes and severities result from differences in the ratio of mutant to wild type protein. Previous experimentation has documented variable levels of mutant protein in different muscles in an MYH7 patient [22], and this concept has support from studies of ACTA1 mutations [23,24]. Additional future studies are, of course, necessary to support this hypothesis.

In addition to expanding the spectrum of known disease-associated MYH7 mutations, these cases demonstrate that independent clinical and histological features can result from the same mutation. This fact complicates the identification of MYH7 myopathy patients based solely on clinical or histological features. The shared features between the two cases (early onset ankle dorsiflexion and neck flexion weakness) are common in Laing distal myopathy and myosin storage myopathy, and may represent the most consistent clinical indicators of a MYH7 myopathy. Of note, the two histopathologic patterns observed (minicore myopathy and CFTD) in our cases have historically not been commonly associated with MYH7 mutations, though recent case studies suggests that these are likely to be common histopathologic subtypes of MYH7-related myopathies [10,12].

These reports raise the possibility that MYH7 may be an important cause of a wide range of congenital myopathies. Cohort studies are needed required to confirm the full range of clinical and histological patterns and to better establish the overall burden of disease associated with MYH7. However, a high index of suspicion for MYH7 mutations appears warranted in a wide range of clinical and histopathologic contexts in genetically unsolved congenital myopathies.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council grants 1022707 and 1031893 (KN & NC), and 1035828 (NC). It was additionally supported in part through the Taubman Medical Institute and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan. Partial support was also derived from NIH K08AR054835 (JJD) and MDA186999 (JJD).

References

- 1.Engel A, Franzini-Armstrong C. Myology: basic and clinical. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capek PC. Gene symbol: MYH7. Disease: cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic. Hum Genet. 2005;118(3–4):537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamont PJ, Udd B, Mastaglia FL, et al. Laing early onset distal myopathy: slow myosin defect with variable abnormalities on muscle biopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):208–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.073825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meredith C, Herrmann R, Parry C, et al. Mutations in the slow skeletal muscle fiber myosin heavy chain gene (MYH7) cause laing early-onset distal myopathy (MPD1) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):703–8. doi: 10.1086/424760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dye DE, Azzarelli B, Goebel HH, Laing NG. Novel slow-skeletal myosin (MYH7) mutation in the original myosin storage myopathy kindred. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(6):357–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laing NG, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Dye DE, et al. Myosin storage myopathy: slow skeletal myosin (MYH7) mutation in two isolated cases. Neurology. 2005;64(3):527–9. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150581.37514.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pegoraro E, Gavassini BF, Borsato C, et al. MYH7 gene mutation in myosin storage myopathy and scapulo–peroneal myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(4):321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajsharghi H, Thornell LE, Lindberg C, et al. Myosin storage myopathy associated with a heterozygous missense mutation in MYH7. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(4):494–500. doi: 10.1002/ana.10693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muelas N, Hackman P, Luque H, et al. MYH7 gene tail mutation causing myopathic profiles beyond Laing distal myopathy. Neurology. 2010;75(8):732–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee4d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortolano S, Tarrio R, Blanco-Arias P, et al. A novel MYH7 mutation links congenital fiber type disproportion and myosin storage myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21(4):254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tasca G, Ricci E, Penttila S, et al. New phenotype and pathology features in MYH7-related distal myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(7):640–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullup T, Lamont PJ, Cirak S, et al. Mutations in MYH7 cause Multi-minicore Disease (MmD) with variable cardiac involvement. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(12):1096–104. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fananapazir L, Dalakas MC, Cyran F, Cohn G, Epstein ND. Missense mutations in the beta-myosin heavy-chain gene cause central core disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(9):3993–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajsharghi H, Oldfors A, Macleod DP, Swash M. Homozygous mutation in MYH7 in myosin storage myopathy and cardiomyopathy. Neurology. 2007;68(12):962. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257131.13438.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh R, Rutland C, Thomas R, Loughna S. Cardiomyopathy: a systematic review of disease-causing mutations in myosin heavy chain 7 and their phenotypic manifestations. Cardiology. 2010;115(1):49–60. doi: 10.1159/000252808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oldfors A. Hereditary myosin myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(5):355–67. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubourg O, Maisonobe T, Behin A, et al. A novel MYH7 mutation occurring independently in French and Norwegian Laing distal myopathy families and de novo in one Finnish patient. J Neurol. 2011;258(6):1157–63. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uro-Coste E, Arne-Bes MC, Pellissier JF, et al. Striking phenotypic variability in two familial cases of myosin storage myopathy with a MYH7 Leu1793pro mutation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(2):163–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampe AK, Bushby KM. Collagen VI related muscle disorders. J Med Genet. 2005;42(9):673–85. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2002.002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercuri E, Lampe A, Allsop J, et al. Muscle MRI in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15(4):303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marian AJ, Mares A, Jr, Kelly DP, et al. Sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Variability in phenotypic expression of beta-myosin heavy chain mutations. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):368–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nier V, Schultz I, Brenner B, Forssmann W, Raida M. Variability in the ratio of mutant to wildtype myosin heavy chain present in the soleus muscle of patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A new approach for the quantification of mutant to wildtype protein. FEBS Lett. 1999;461(3):246–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng JJ, Marston S. Genotype-phenotype correlations in ACTA1 mutations that cause congenital myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravenscroft G, Jackaman C, Bringans S, et al. Mouse models of dominant ACTA1 disease recapitulate human disease and provide insight into therapies. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 4):1101–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]