Abstract

Objectives. We assessed whether community health workers (CHWs) could improve glycemic control among Mexican Americans with diabetes.

Methods. We recruited 144 Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes between January 2006 and September 2008 into the single-blinded, randomized controlled Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH) and followed them for 2 years. Participants were assigned to either a CHW intervention, delivering self-management training through 36 home visits over 2 years, or a bilingual control newsletter delivering the same information on the same schedule.

Results. Intervention participants showed significantly lower hemoglobin A1c levels than control participants at both year 1 Δ = −0.55; P = .021) and year 2 (Δ = −0.69; P = .005). We observed no effect on blood pressure control, glucose self-monitoring, or adherence to medications or diet. Intervention participants increased physical activity from a mean of 1.63 days per week at baseline to 2.64 days per week after 2 years.

Conclusions. A self-management intervention delivered by CHWs resulted in sustained improvements in glycemic control over 2 years among Mexican Americans with diabetes. MATCH adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of CHWs to reduce diabetes-related health disparities.

The growing prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults in the United States is well documented, with adverse impact strongest among ethnic minorities and low-income populations. The age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes is 12.6% among non-Hispanic Blacks, 11.8% among Hispanics, and only 7.1% among non-Hispanic Whites.1 Mexican Americans, who make up almost two thirds of US Hispanics,2 have an even higher diabetes prevalence of 13.3%.3 Disparities also persist in both processes of care and clinical outcomes. Mexican Americans with diabetes are significantly less likely than non-Hispanic Whites with the disease to be aware of and treated for comorbid hypertension or dyslipidemia.4 Mexican Americans are less likely to receive recommended clinical services, such as regular ophthalmologic and foot exams,5 and are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to have well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and cholesterol levels. In this context, it is not surprising that they are more than twice as likely as non-Hispanic Whites to be hospitalized for uncontrolled diabetes or long-term complications of diabetes5 and that they experience higher diabetes mortality rates.6–8 Although non-Hispanic Whites have experienced reductions in diabetes-related mortality in the past decades, Hispanics have not.8 Thus, unless effective public health strategies are identified and implemented, gaps in health outcomes are likely to grow.

Community health workers (CHWs) are frontline public health workers who serve as liaisons between providers and community members, facilitate access to services, and improve both quality and cultural competence of service delivery.9,10 Several characteristics suggest that they may be well suited to addressing diabetes disparities. Because CHWs share culture, language, and knowledge of the community, they engage minority populations more effectively than the formal health care system can.11,12 Living and working in the same community as the people they serve, CHWs are able to provide individualized attention, focus on behavior-related tasks, and deliver regular feedback on the completion of those tasks.13 These qualities should lead to improved diabetes self-management and clinical outcomes. Although much has been written about CHWs in the past decade, few rigorous randomized controlled trials have tested this hypothesis,14–18 and the efficacy of CHWs in improving clinical outcomes in diabetes is not established. Of 6 published randomized controlled trials,19–25 only 2 demonstrated improvements in HbA1c levels among intervention participants, and both of these studies followed participants for only 6 months.19,24 Methodological limitations led the authors of a 2009 Agency for Health Care Research and Quality review to rate the published evidence as fair at best.15

The Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH) sought to address these limitations of the literature through a rigorously designed behavioral randomized controlled trial with outcomes measured at 1 and 2 years. The primary study hypothesis was that the CHW intervention, compared with an attention control, would result in improvement in short-term physiological outcomes (mean HbA1c levels and percentage with controlled blood pressure). A secondary hypothesis was that the CHW intervention would improve adherence to self-management behaviors, such as daily self-monitoring of blood glucose, medication taking, and adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations.

METHODS

Eligible participants in MATCH were Mexican Americans in metropolitan Chicago with type 2 diabetes, aged 18 years or older, who were being treated with at least 1 oral hypoglycemic agent. We defined ethnic identity as having been born in Mexico or having at least 1 parent or 2 grandparents born in Mexico. To ensure that lack of access to care did not pose a barrier to diabetes self-management, we required participants to have health insurance or to receive primary care through a free clinic or public facility at the time of enrollment. Exclusions for participation were active treatment of schizophrenia, inability to provide informed consent, previous major end-organ complications of diabetes such as end-stage renal disease or stroke, or another household member already participating in MATCH. To reduce the possibility of interruption in the intervention, we excluded participants with plans for extended travel in the next 12 months or who had lived in Mexico for more than 4 months in the 2 years prior to enrollment. Recruitment strategies for the study are described elsewhere,26 and consisted of direct mailings, outreach at community events and churches, partnerships with primary care clinics, and direct outreach by the CHWs themselves, conducted between January 2006 and September 2008. We randomized 144 participants and followed them for 2 years. The study was powered at 80% to detect a difference of 1% in HbA1c level between the intervention and placebo group, allowing for a 20% dropout rate in each arm at α = 0.025 to adjust for 2 primary outcomes. Participants were told that the study was comparing 2 forms of diabetes education and were blinded to the study hypothesis.

After obtaining informed consent, bilingual research assistants collected baseline evaluations in 2 separate encounters, approximately 30 days apart. At the second visit, research staff collected electronic pill caps and audited glucose monitors for adherence. We conducted most evaluations in participants' homes; 12 participants completed examinations in an alternative community setting or at Rush University Medical Center. After the full initial evaluation was completed, we randomized participants 1 to 1 to receive either the CHW visits (intervention arm) or the newsletter (control arm). Randomization used a permuted block design with block sizes of 4 and 6 in a single randomization scheme. The Rush Preventive Medicine Data Management Center generated randomization lists. Research assistants blinded to participants’ group assignments collected outcome data at 12 and 24 months after randomization.

To enhance retention in this vulnerable population, we obtained multiple contacts for each participant, and research assistants called every 3 months to update this information. If a participant could not be reached, we implemented an aggressive lost–to–follow-up procedure. When participants relocated, we obtained outcome interviews by telephone, physical measures from physicians in their new community, and HbA1c results through a national reference laboratory. As a result of these methods, 121 participants (84%) completed at least 1 follow-up examination within 2 years. We obtained follow-up HbA1c measurements for 79.5% of participants in the intervention arm and 85.9% in the control arm (P = .306). Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows the CONSORT diagram, documenting flow of participants from recruitment through final data collection.

Intervention and Control

CHWs delivered behavioral self-management training during 36 home visits over 2 years. We selected this frequency and duration of visits because self-management theory indicates that skill mastery occurs slowly with multiple repetitions.27–29 The CHWs were bilingual Mexican Americans who lived in the target community and worked for a local nonprofit agency; they did not themselves have diabetes. None of the CHWs had postsecondary education. Prior to starting the intervention, 10 CHWs received more than 100 hours of training on diabetes, behavioral self-management support, and home visiting; the training curriculum is described in detail elsewhere.30 From those who demonstrated acquisition of the needed knowledge and skills to the investigators, we hired 3 to be CHWs for MATCH. Over the 4.5-year study period, the 3 CHWs delivered 1647 home visits lasting an average of 99 minutes, not including the time involved in transportation, missed appointments, and follow-up telephone calls. The median number of visits delivered by a full-time CHW each week was 7; the 75th percentile for visits was 10 per week. We audiotaped study visits, and the study psychologist (C. M. T. L) reviewed them to ensure intervention fidelity.

MATCH emphasized knowledge and skills in diabetes self-management, with repeated opportunities to practice goal setting and self-management. We derived the curriculum from the 7 core diabetes self-management behaviors recommended by the American Academy of Diabetes Educators, the AADE 7.31 To help participants implement these behaviors, the CHWs taught 5 general self-management skills: brainstorming and problem solving, using a journal or written record, modifying the home environment to support behavior change, seeking social support from family or friends, and managing stress. CHWs taught in the participant’s preferred language and used culturally appropriate examples or metaphors. Theoretical framework, intervention components, and strategies to assure fidelity are described in detail elsewhere.32 Beyond this behavioral intervention, participants received no other resources during the trial, such as glucose meters, test strips, or medications.

Participants randomized to the control arm received a bilingual newsletter called DiabetesAction. Thirty-six mailed newsletters covered the AADE 7 topics and the 5 general self-management skills, providing control participants with the same number of contacts as received by those in the intervention arm and comparable diabetes self-management education. We adopted this behavioral control experience, rather than usual care alone, for both ethical and scientific reasons. Because this population receives low rates of diabetes education, we sought to ensure that all participants had access to some form of self-management training. In addition, the relatively intensive newsletter control sought to reduce the risk that any differences would be attributable to a Hawthorne effect, in which attention, rather than the specific intervention, produces change.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures for MATCH were serum HbA1c level and blood pressure control (defined as blood pressure < 130/8033) over 24 months. Research assistants collected blood by venipuncture for HbA1c in participants’ homes, and a commercial reference laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Madison NJ) analyzed the samples. Trained research assistants recorded seated resting blood pressure measurements 3 times; blood pressure was reported as the average of the second and third measurement. CHWs conducted interviews in the participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish). The interviews incorporated validated translations of the Diabetes Empowerment Scale,34 the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities,35 the 4-item Morisky Adherence Scale,36 Personal Resource Questionnaire,37,38 Beck Depression Inventory,39 Perceived Stress Scale,40 and the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory.41 We assessed medication adherence with a medication bottle containing 1 of the participant’s oral diabetes medications fitted with a MEMS electronic monitoring pill cap (MEMS 6 Track Cap, AARDEX Ltd, Sion, Switzerland). Research assistants reviewed participants’ glucose meter to determine the number of days of the preceding 10 days participants had measured their glucose at least once. We assessed patient acculturation with the Marin instrument, a 12-item questionnaire with subscales for language use, media use, and preferences for social relations.42,43 We collected all measures at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months; details regarding measures are described elsewhere.32 Two physicians blinded to participant identity and group allocation reviewed all records of hospitalizations, deaths, and other possible adverse events.

Data Analyses

The Data Management Center processed the data, and we used SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. Comparisons of categorical variables used χ2 tests. Comparisons of continuous variables used the 2-sample t-test except where small sample sizes or skewed distributions warranted use of the Wilcoxon rank sum test. We used the intent-to-treat principle and all available data in outcome analyses. We considered differences statistically significant at P < .05.

For the 2 primary outcomes of HbA1c and blood pressure control measured over time, we used a mixed-effects linear model analysis with fixed effects only and time (baseline, 12 months, 24 months), treatment arm, and a time–by–treatment arm interaction. We ran mixed models with PROC mixed with the compound symmetry covariance structure. We included baseline HbA1c as a covariate in the HbA1c model, because HbA1c is integrally related to change in HbA1c over time. We assessed the influence of prespecified covariates on both outcomes with backward elimination that retained only variables achieving a P value of less than .2 at each iteration. The prespecified baseline covariates were age, gender, marital status, education, economic hardship, acculturation, body mass index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters), perceived stress, social support, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms. We also included all covariates that approached significant difference (P < .1) between the 2 treatment arms at baseline. We investigated the impact of missing data with multiple imputation techniques.44

A priori secondary outcomes were medication adherence, glucose self-monitoring, self-management behaviors, as determined by the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities, and self-efficacy, measured by the Diabetes Empowerment Scale. We assessed medication adherence by pill cap openings over 30 days. Each day, the cap calculated the proportion of the participant’s regimen that was taken. We determined the medication adherence score as the average of daily proportion of regimen taken. We categorized participants as adherent for scores of 0.80 or higher. If participants reported no medication adherence problems on the Morisky scale, we considered them to be self-reported medication adherent. We similarly categorized participants as glucose self-monitoring adherent if their glucose meter showed monitoring of glucose on 8 or more of the previous 10 days. We assessed self-reported adherence to diet, physical activity, and other self-management behaviors through subscales of the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities and the Diabetes Empowerment Scale. We analyzed these categorical outcomes of adherence with the same mixed-effects linear models described for primary outcomes.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the population appear in Table 1. Intervention and control arms did not differ in demographic characteristics, although they had modest differences in 3 clinical measures. At baseline, diastolic blood pressure was higher in the intervention than the control arm, with a mean difference of 3.3 millimeters of mercury (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.0, 6.7); intervention participants were less likely than control participants to have been taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) at baseline (odds ratio [OR] = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.3, 1.1). Anxiety symptom scores, as measured by the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory, were lower in the intervention than the control arm, with a mean difference of −2.1 (95% CI = −3.9, −0.1).

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics of Participants With Diabetes Mellitus: Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers, Chicago, IL, 2006–2008

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 144), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Intervention Arm (n = 73), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Control Arm (n = 71), No. (%) or Mean ±SD |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age, y | 53.7 ±12.2 | 53.7 ±11.7 | 53.6 ±12.7 |

| Primary and secondary education, y | |||

| ≤ 6 | 82 (56.9) | 42 (57.5) | 40 (56.3) |

| 7–11 | 25 (17.4) | 13 (17.8) | 12 (16.9) |

| > 11 | 37 (25.7) | 18 (24.7) | 19 (26.8) |

| College completed | |||

| None | 106 (73.6) | 56 (76.7) | 50 (70.4) |

| Trade school | 26 (18.1) | 12 (16.4) | 14 (19.7) |

| Some college/associate degree/bachelor's degree | 11 (7.7) | 4 (5.6) | 7 (9.9) |

| Female | 97 (67.4) | 47 (64.4) | 50 (70.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/common law marriage | 94 (65.3) | 44 (60.3) | 50 (70.4) |

| Separated/divorced | 19 (13.2) | 12 (16.4) | 7 (9.9) |

| Widowed | 12 (8.3) | 6 (8.2) | 6 (8.5) |

| Never married | 19 (13.2) | 11 (15.1) | 8 (11.3) |

| Difficulty paying for basics | |||

| Very hard | 19 (23.8) | 7 (16.3) | 12 (32.4) |

| Somewhat hard | 38 (47.5) | 21 (48.8) | 17 (46.0) |

| Not hard at all | 23 (28.8) | 15 (34.9) | 8 (21.6) |

| Preferred language | |||

| English | 14 (9.7) | 6 (8.2) | 8 (11.3) |

| Spanish | 130 (90.3) | 67 (91.7) | 63 (88.7) |

| Acculturation scorea | 1.6 ±0.8 | 1.6 ±0.8 | 1.6 ±0.8 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Hemoglobin A1c (continuous) | 8.3 ±2.0 | 8.5 ±2.2 | 8.1 ±1.6 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (categorized) | |||

| < 7 | 41 (29.5) | 23 (32.9) | 18 (26.1) |

| 7–9 | 52 (37.4) | 22 (31.4) | 30 (43.5) |

| > 9 | 46 (33.1) | 25 (35.7) | 21 (30.4) |

| Hypertension control (< 130/80), mmHg | 61 (42.7) | 34 (47.2) | 27 (38.0) |

| Systolic | 131.7 ±14.9 | 133.6 ±16.5 | 129.7 ±12.9 |

| Diastolic | 70.8 ±10.2 | 72.5 ±8.5 | 69.2** ±11.5 |

| BMI (continuous), kg/m2 | 33.4 ±8.5 | 32.7 ±7.4 | 34.2 ±9.5 |

| BMI (categorized), kg/m2 | |||

| Normal (< 25) | 20 (14.1) | 10 (13.7) | 10 (14.5) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 35 (24.7) | 20 (27.4) | 15 (21.7) |

| Obese, class 1 & 2 (30–39.9) | 61 (42.4) | 32 (42.4) | 29 (40.8) |

| Obese class 3 (≥ 40) | 26 (18.3) | 11 (15.1) | 15 (21.7) |

| Adherence and medication usage | |||

| Adherent to drug regimenb | 44 (30.6) | 24 (32.9) | 20 (28.2) |

| Adherent ≥ 80% to drug regimenc | 63 (44.1) | 32 (44.4) | 31 (43.7) |

| Medications, total no. | 4.8 ±2.9 | 4.5 ±2.7 | 5.1 ±3.0 |

| Taking ACE inhibitor or ARB | 67 (46.5) | 29 (39.7) | 38* (53.5) |

| Taking aspirin | 51 (35.4) | 25 (34.3) | 26 (36.6) |

| Check glucose ≥ 8/10 d | 47 (36.4) | 22 (33.9) | 25 (39.1) |

| Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities, d/wk | |||

| General diet | 3.6 ±2.7 | 3.4 ±2.7 | 3.8 ±2.8 |

| Diabetes-specific diet | 3.9 ±1.9 | 3.4 ±2.7 | 3.8 ±2.8 |

| Exercise | 1.8 ±1.9 | 1.6 ±1.7 | 1.9 ±2.1 |

| Blood-glucose testing | 2.8 ±3.0 | 2.5 ±3.1 | 3.2 ±3.0 |

| Foot care | 5.1 ±2.7 | 4.8 ±3.0 | 5.5 ±2.4 |

| Psychosocial factors | |||

| Depressiond | 9.9 ±9.6 | 9.4 ±9.3 | 10.5 ±10.0 |

| Social supporte | 137.7 ±18.2 | 137.2 ±17.7 | 138.3 ±18.7 |

| Perceived stressf | 7.9 ±3.4 | 7.5 ±3.2 | 8.3 ±3.6 |

| Anxietyg | 14.8 ±5.9 | 13.8 ±5.3 | 15.9** ±6.3 |

| Self-efficacyh | 4.4 ±0.6 | 4.4 ±0.6 | 4.3 ±0.5 |

Note. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI = body mass index.

Marin language subscale; range = 1–5; higher score indicates greater acculturation.

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale; 4 = adherence.

Monitored with electronic pill cap.

Beck Depression Inventory; range = 0–63; higher score indicates greater depression.

Personal Resource Questionnaire; range = 25–175; higher score indicates greater social support.

Perceived Stress Scale; range = 4–20; higher score indicates greater perceived stress.

Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; range = 9–36; higher score indicates greater anxiety.

Diabetes Empowerment Scale; range = 1–5; higher score indicates greater self-efficacy.

*P ≤ .10; **P ≤ .05.

Mean age at enrollment was 53.7 years, and the majority of participants were women. Participants in general showed low acculturation to mainstream US culture; 93% were born in Mexico, and 90% chose Spanish as their preferred language. Participants had low socioeconomic status, with more than 70% reporting difficulty paying for basic needs and 74% of participants reporting that they had not completed high school (or equivalent). The population was characterized by relatively poor rates of glycemic and blood pressure control. Only 30% had HbA1c levels of less than 7.0, and 42.7% had blood pressure at target levels, below 130/80. Self-reported glucose self-monitoring at baseline was infrequent (mean = 2.8 days/week), as was physical activity (mean = 1.8 days/week).

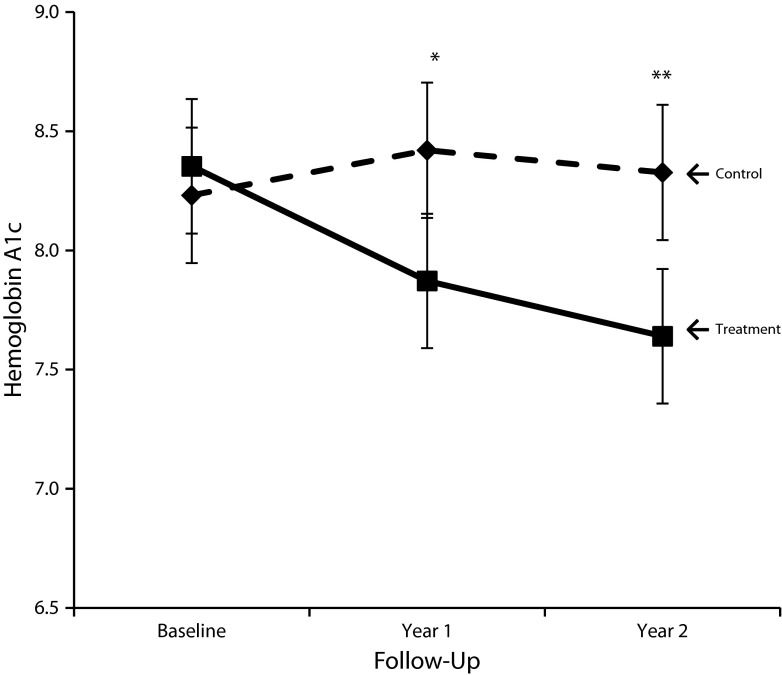

Results of the primary analysis on HbA1c are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. At year 1, the HbA1c level of participants in the intervention arm was 0.55 points lower than among control participants (P = .021). At year 2, the difference increased to 0.69 points (P = .005). Of the prespecified covariates, age, marital status, education, economic hardship, depressive symptoms, and taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB medication trended toward significance at P < .2, but including them in the model did not change the estimate of the treatment effect.

FIGURE 1—

Mixed-effects linear model analysis with fixed effects only and time, treatment arm, time–by–treatment arm interaction, and baseline hemoglobin A1c among participants with diabetes mellitus: Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers, Chicago, IL, 2006–2008.

Note. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

*P = .02; **P = .005.

TABLE 2—

Primary Outcomes From Mixed Models of Continuous Hemoglobin A1c and Blood Pressure Control Among Participants With Diabetes Mellitus: Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers, Chicago, IL, 2006–2008

| Model | Intervention | Control |

| 1: Continuous HbA1c, estimated mean (95% CI) | ||

| Baseline | 8.35 (8.07, 8.64) | 8.23 (7.95, 8.52) |

| Follow-up year 1* | 7.87 (7.59, 8.16) | 8.42 (8.13, 8.70) |

| Follow-up year 2** | 7.64 (7.36, 7.92) | 8.33 (8.04, 8.61) |

| 2: Blood pressure control (< 130/80), estimated proportion (95% CI) | ||

| Baseline | 0.39 (0.28, 0.51) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.58) |

| Follow-up year 1 | 0.59 (0.46, 0.70) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.63) |

| Follow-up year 2 | 0.42 (0.30, 0.55) | 0.58 (0.45, 0.70) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; Hb = hemoglobin. Mixed-effects linear model analysis with fixed effects only and time (baseline, 12 mo, 24 mo), treatment arm, and a time–by–treatment arm interaction. Baseline HbA1c was included as a covariate in Model 1.

*P < .05; **P < .01, comparing treatment arms.

Results of the primary analysis of blood pressure control are presented in Table 2. We found no significant difference between treatment arms at either follow-up year in the percentage of participants achieving blood pressure control. In the adjusted model, age, gender, BMI, and taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB medication were the only significant covariates. Women were more likely to have blood pressure in the controlled range; greater age, higher BMI, and taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB medication decreased the likelihood of controlled blood pressure. Inclusion of the covariates did not change the estimate of treatment effect.

We conducted per-protocol analyses to determine whether the number of CHW encounters (intervention dose) affected outcomes. Although 31.5% of participants in the intervention arm received all 36 visits, 34.2% received less than half of the prescribed intervention. We detected no dose–response relationship for overall number of visits and final outcome.

We investigated the impact of missing data with multiple imputation techniques. Baseline characteristics related to missingness were age, treatment arm, and taking ACE or ARB medication. We used these variables to create 5 imputations. Estimates and P values from mixed and generalized linear models that incorporated imputed data were similar to the results presented here, indicating that missing data did not influence model outcomes.

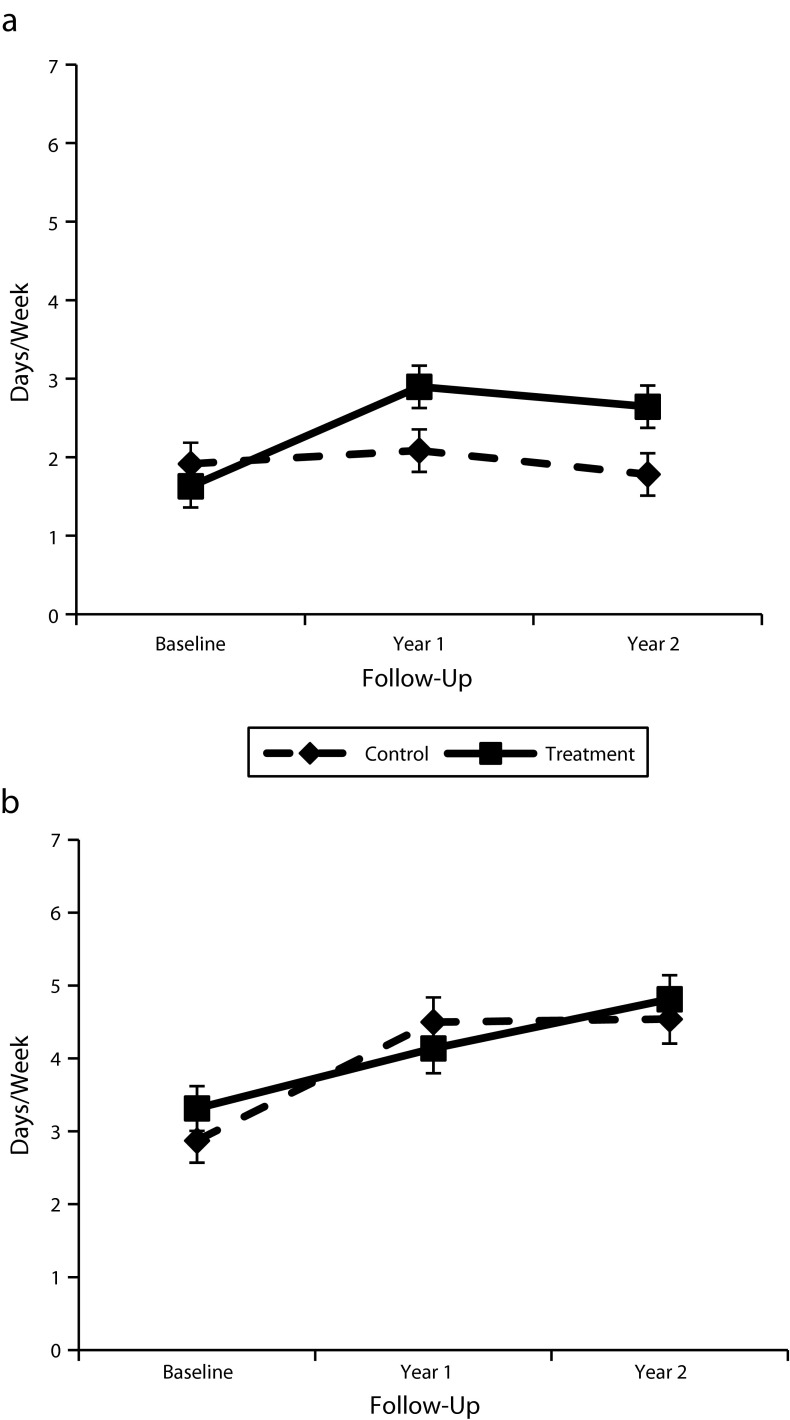

Secondary measures (Figure 2) showed no significant differences between arms for medication adherence or daily glucose self-monitoring. Glucose self-monitoring increased significantly from baseline to year 2 in both arms; medication adherence did not change over time for either group.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of participants with diabetes mellitus who (a) adhered ≥ 80% to drug regimen and (b) checked glucose ≥ 8/10 days: Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers, Chicago, IL, 2006–2008.

Note. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

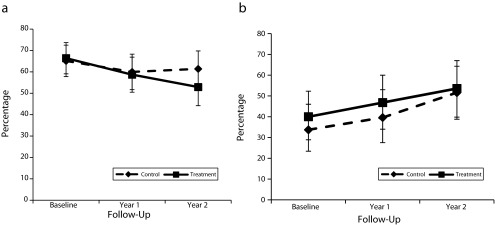

Intervention participants reported increased physical activity, from a mean of 1.63 days per week at baseline to 2.64 days per week after 2 years; the control participants had decreased self-reported physical activity at year 2. Self-efficacy increased significantly for both study arms, and we documented improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption, with no significant between-group differences (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3—

Number of days/week that participants with diabetes mellitus (a) self-reported exercise and (b) consumed fruits and vegetables: Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers, Chicago, IL, 2006–2008.

Note. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Weight loss was significantly different between the 2 arms. Weight among participants in the control arm did not change over 2 years, but intervention participants weighed 4.82 pounds less at year 1 (P = .041) and 5.02 pounds less at year 2 (P = .036) than at baseline.

Significant adverse events were infrequent in both groups. We observed no differences in emergency department or hospital utilization between the 2 arms. Study withdrawal rates were comparable, as shown in Figure A.

DISCUSSION

The MATCH study found a significant benefit of a CHW intervention over written educational material in improving glycemic control in an ethnic minority population. Although previous studies showed the benefit of such interventions for much shorter periods,19,24 MATCH demonstrated for the first time that a CHW intervention can help individuals with diabetes achieve and maintain improvements in glycemic control over 2 years.

The benefit of lowered HbA1c levels has recently been called into question by findings from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes), ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease—Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation), and Veterans Affairs Diabetes trials.45–50 All 3 trials emphasized aggressive medication management; in ACCORD, these efforts toward approximating normal glucose control were associated with significant increases in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. These increases may be associated with increased frequency of hypoglycemic episodes. Unlike these drug trials, the MATCH intervention employed CHWs to emphasize self-management behaviors. This behavioral intervention produced decreases in hemoglobin HbA1c comparable to those promoted by many pharmaceutical companies on Web sites and in package inserts.51,52 Unlike with medications, we detected no adverse effects from the CHW intervention, and no study participants were hospitalized for hypoglycemia. MATCH had no significant difference in study dropout rates between its 2 arms, suggesting that the time and effort involved in the CHW intervention were well tolerated by participants.

Our analysis did not determine the pathways by which CHWs improved glycemic control. The CHW model empowers community members to identify their own needs and implement their own solutions, leading to improved community and personal self-efficacy.53-56 Although social support (total Personal Resource Questionnaire score) showed significant improvements over 2 years (baseline to 1 year, 6.7 points; P = .015; baseline to 2 years, 12.7 points; P < .001), we found no significant difference between the intervention and control arms. This may be a limitation of the measure used, which was not specifically designed for this population.

The lack of change in medication adherence over time in either group suggests that improved medication adherence was not the primary mechanism. Participants in the CHW arm may have made more frequent visits for primary medical care or been more persistent in seeking medication from their physicians. The modest increase in self-reported physical activity in the CHW arm may also have improved outcomes, especially in light of the demonstrated weight loss in this group; the use of more precise measures of physical activity (e.g., accelerometry) or diet (e.g., food frequency questionnaires) might have captured behavior changes that contributed to improvements in glycemic control and weight.

Although physicians often voice skepticism about patients’ ability to significantly change behavior,57,58 MATCH participants working with CHWs achieved HbA1c reduction after 1 and 2 years. Although some may argue that 36 intervention visits are cost prohibitive, the average salary and benefits of CHWs were $85 per participant per month. In comparison with the 730 doses of a once-daily medication taken for 2 years, 36 CHW visits may be viewed as a relatively modest investment. Future studies may also help determine whether fewer visits can achieve comparable clinical improvements at lower cost.

The lack of benefit in blood pressure control from the CHW intervention may reflect several factors. MATCH emphasized glycemic control in its curriculum but did not specifically promote dietary sodium restriction. We measured adherence with pill caps for oral diabetic medication but not for blood pressure medication. We coached participants to use glucose self-monitoring to identify behaviors that affected glycemic control; because we did not offer home blood pressure monitoring, participants had no opportunity to similarly track and observe the impact of their medication adherence, diet, and physical activity on blood pressure.

Limitations

MATCH used a rigorous randomized controlled design to ensure high internal validity. We conducted the study in a single population in a single location, raising questions of external validity and generalizability. Because MATCH tested the efficacy of the CHW intervention, we went to great lengths in the selection and training of the CHWs, and we provided participants with a high number of contacts. Multisite randomized controlled trials should be conducted to determine whether this intervention can be delivered with high fidelity and efficacy across multiple communities under more typical clinical conditions. In light of the importance of cultural sensitivity in the MATCH intervention, caution must be used in generalizing these findings to other racial and ethnic groups.

The study design did not allow us to answer the question of sustainability of benefits after the end of the intervention. As with medications, stopping the CHW intervention may result in a cessation of benefits. Future studies should allow for long-term follow-up after the end of the intervention.

Finally, as with so much of the CHW literature, we cannot define a specific mechanism for CHW effectiveness. Modest self-reported improvements in physical activity may have played a role. It is possible, however, that the improved glycemic control was the result of increased perceived social support and an improved sense of well-being that were not measured.

Conclusions

MATCH adds a rigorous randomized controlled trial to the growing body of literature showing the benefits of CHW interventions in improving the health of persons with chronic disease. The maintenance of a benefit in HbA1c levels over a 2-year period is particularly important, because transient improvements followed by return to baseline behaviors are unlikely to reduce long-term complications and mortality. Future studies are needed to strengthen the study’s impact on behavioral intermediate steps, clarify the necessary dose and duration of the CHW intervention, assess the specific mechanisms by which CHWs improve self-care, and evaluate maintenance of treatment effect.

Although some questions remain unanswered, MATCH affirms the benefits and safety of CHW interventions. Had this been a drug trial, regulatory approval for CHWs would likely be forthcoming, with insurers paying for such a safe and effective medication. Widespread acceptance of CHWs as an important part of the health care team to enhance patient outcomes is long overdue and should be considered a priority by policymakers seeking to reduce health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Mexican American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH) was funded by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant R01-DK061289).

DeJuran Richardson, PhD, provided invaluable feedback during the writing of this article. The design, development, and implementation of the MATCH study, and the work described in this article, would not have been possible without the efforts of the community health workers (promotoras) Pilar Gonzalez, Susana Leon, and Maria Sanchez, and the staff of Centro San Bonifacio, Chicago. Estamos agradecidos.

Human Participant Protection

MATCH was approved by the institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center.

References

- 1.Beckles GL, Zhu J, Moonesinghe R. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diabetes—United States, 2004 and 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(suppl):90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG, editors. 2011. The Hispanic population in the US: 2011. US Census Bureau. Available at http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Ferrario CM. Diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Quality and Improvement. 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. AHRQ publication 11-0005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt KJ, Gonzalez ME, Lopez R, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Gonzalez-Villalpando C. Diabetes is more lethal in Mexicans and Mexican-Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(12):899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt KJ, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hazuda HP, Haffner SM, Stern MP. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among diabetic participants in the San Antonio heart study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(9):1557–1563. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2317–2324. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):403–408. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulton-Kehoe D, Hamman RF, Baxter J, Marshall J. A case-control study of physical activity and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). The San Luis Valley diabetes study. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(5):320–327. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis JN, Weigensberg MJ, Shaibi GQ et al. Influence of breastfeeding on obesity and type 2 diabetes risk factors in Latino youth with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):784–789. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinneen SF, Bjornsen SS, Bryant SC et al. Towards an optimal model for community-based diabetes care: design and baseline data from the Mayo Health System Diabetes Translation Project. J Eval Clin Pract. 2000;6(4):421–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson S, Baron RB, Cooper B, Janson S. Does health service use in a diabetes management program contribute to health disparities at a facility level? Optimizing resources with demographic predictors. Popul Health Manag. 2009;12(3):139–147. doi: 10.1089/pop.2008.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):247–259. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B et al. Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2009 (181):1–144, A1–2, B1–14, passim. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):544–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lujan J, Ostwald SK, Ortiz M. Promotora diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(4):660–670. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corkery E, Palmer C, Foley ME, Schechter CB, Frisher L, Roman SH. Effect of a bicultural community health worker on completion of diabetes education in a Hispanic population. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):254–257. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gary TL, Batts-Turner M, Yeh HC et al. The effects of a nurse case manager and a community health worker team on diabetic control, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations among urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1788–1794. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gary TL, Batts-Turner M, Bone LR et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of nurse case manager and community health worker team interventions in urban African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(1):53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckham S, Bradley S, Washburn A, Taumua T. Diabetes management: utilizing community health workers in a Hawaiian/Samoan population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(2):416–427. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer EC et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2253–2260. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babamoto KS, Sey KA, Camilleri AJ, Karlan VJ, Catalasan J, Morisky DE. Improving diabetes care and health measures among Hispanics using community health workers: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):113–126. doi: 10.1177/1090198108325911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin MA, Swider SM, Olinger T et al. Recruitment of Mexican American adults for an intensive diabetes intervention trial. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(1):7–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swider SM, Martin M, Lynas C, Rothschild S. Project MATCH: training for a promotora intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(1):98–108. doi: 10.1177/0145721709352381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Association of Diabetes Educators. AADE 7™ self-care behaviors: American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) position statement. 2011 Available at: http://www.diabeteseducator.org/ProfessionalResources/Library/PositionStatements.html. Accessed November 24, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothschild SK, Martin MA, Swider SM et al. The Mexican-American Trial of Community Health Workers (MATCH): design and baseline characteristics of a randomized controlled trial testing a culturally tailored community diabetes self-management intervention. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, Marrero DG. The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: a measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(6):739–743. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinert C, Brandt P. Measuring social support with the PRQ. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1987;9:589–602. doi: 10.1177/019394598700900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinert C. Measuring social support: Revision and further development of the personal resource questionnaire. Measurement of Nursing Outcomes. In: Waltz C, Strickland O, editors. New York: Springer; 1988. pp. 309–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for beck depression inventory II (BDI-II). San Antonio (TX): Psychology Corporation. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983 December 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spielberger CD. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marin G, Marin B, editors. Applied Social Research Methods Series Research With Hispanic Populations. Vol. 23. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. 2nd edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nilsson PM. ACCORD and risk-factor control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1628–1630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1002498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riddle MC. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial. Circulation. 2010;122(8):844–846. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riddle MC, Ambrosius WT, Brillon DJ et al. Epidemiologic relationships between A1C and all-cause mortality during a median 3.4-year follow-up of glycemic treatment in the ACCORD trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):983–990. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lund SS, Vaag AA. Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association: response to Skyler et al. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):e90–e91. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dluhy RG, McMahon GT. Intensive glycemic control in the ACCORD and ADVANCE trials. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2630–2633. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0804182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoogwerf BJ. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Does intensive therapy of type 2 diabetes help or harm? Seeking accord on ACCORD. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(10):729–737. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.10.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merck. Januvia (sitagliptin) prescribing information. Available at: http://www.januvia.com/sitagliptin/januvia/consumer/prescribing-information-for-januvia/index.jsp. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- 52.Novartis. Starlix (nateglinide) tablets prescribing information. Available at: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/Starlix.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2011.

- 53.Berman PA, Gwatkin DR, Burger SE. Community-based health workers: head start or false start towards health for all? Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(5):443–459. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koch E, Thompson A, Keegan P, editors. Community Health Workers–A Leadership Brief on Preventive Health Programs. Washington, DC: Civic Health Institute at Codman Square Health Center, Harrison Institute for Public Law at Georgetown University Law Center, and Center for Policy Alternatives; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witmer A, Seifer SD, Finocchio L, Leslie J, O’Neil EH. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8 pt 1):1055–1058. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pérez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):11–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein MG, DePue J, Kazuira A. Models for provider-patient interaction: applications to health behavior change. In: Shumaker SA, Schon EB, Ockene JK, McBeem WL, editors. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 1998. pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orleans CT, George LK, Houpt JL, Brodie KH. Health promotion in primary care: a survey of U.S. family practitioners. Prev Med. 1985;14(5):636–647. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(85)90083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]