Abstract

Objectives. We identified to what extent the Department of Defense postdeployment health surveillance program identifies at-risk drinking, alone or in conjunction with psychological comorbidities, and refers service members who screen positive for additional assessment or care.

Methods. We completed a cross-sectional analysis of 333 803 US Army active duty members returning from Iraq or Afghanistan deployments in fiscal years 2008 to 2011 with a postdeployment health assessment. Alcohol measures included 2 based on self-report quantity-frequency items—at-risk drinking (positive Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions [AUDIT-C] screen) and severe alcohol problems (AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher)—and another based on the interviewing provider’s assessment.

Results. Nearly 29% of US Army active duty members screened positive for at-risk drinking, and 5.6% had an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher. Interviewing providers identified potential alcohol problems among only 61.8% of those screening positive for at-risk drinking and only 74.9% of those with AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher. They referred for a follow-up visit to primary care or another setting only 29.2% of at-risk drinkers and only 35.9% of those with AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher.

Conclusions. This study identified missed opportunities for early intervention for at-risk drinking. Future research should evaluate the effect of early intervention on long-term outcomes.

A 2013 Institute of Medicine committee report determined that substance use problems in the military are a public health crisis and recommended that the Department of Defense (DoD) improve the quality of prevention, early intervention, and treatment of substance use problems among service members.1 Population-based studies reported increased binge drinking in the military over the past decade,2 with almost 40% of currently drinking active duty members reporting binge drinking in the past 30 days in the 2011 DoD Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel.3 Furthermore, young service members and those younger than the legal drinking age reported more binge drinking than did their civilian counterparts.4,5

Cost and consequences of alcohol misuse in the military merit further attention. Binge drinkers in the military report higher rates of accidents, criminal justice problems, and military-related job problems compared with their peers,4,6–8 hindering the readiness of US armed forces.1,9–12 US Army and DoD forensic analysis of military suicides has linked alcohol and drug abuse with suicide cases.13,14 In 2011, substance use disorders (alcohol and other drugs) ranked seventh for medical encounter burden in the Military Health System, first for total hospital bed days and among the top 4 conditions for duty days lost as a result of seeking medical care.15 Furthermore, medical encounters associated with acute and chronic alcohol diagnoses were 50% higher in 2010 than in 2001.15

Whether the upward trend in alcohol misuse is directly linked to the decade of conflict in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom is unknown, but alcohol misuse is associated with deployment duration and frequency and combat exposure.16–20 The association of deployment with alcohol misuse may be mediated through combat-related comorbidities, including posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.16,21

One intervention point to address alcohol misuse is through the DoD’s postdeployment health surveillance program, which includes a health assessment (Post-Deployment Health Assessment [PDHA], Form DD 2796) within 30 days after return from deployment and a second health assessment 3 to 6 months postdeployment (Post-Deployment Health Re-Assessment [PDHRA], Form DD 2900).22 Improvements to the program over time have included additional scoring instructions and guidelines for the clinicians who review the self-report assessments23 and revisions to the PDHA and PDHRA in 2008, including the addition of standardized screening items for alcohol consumption.24

Previous studies have reported on self-reported alcohol misuse and mental health problems when older versions of these health assessments were used and have identified overall low referrals postdeployment to specialty alcohol treatment between 2003 and 2005.25,26 Hoge et al.26 examined the PDHA reports of US Army and Marine members returning from Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003 to 2004 and reported that prevalence of mental health–positive screens for those who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom was higher than for those serving in Operation Enduring Freedom, 19.1% and 11.3%, respectively, with low referral rates for mental health problems: only 4.3% (Operation Iraqi Freedom) and 2.0% (Operation Enduring Freedom). Milliken et al.25 studied the PDHRA reports of US Army service members returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2005 to 2006 and reported that 11.8% appeared to have concern about their drinking based on 2 items27; however, only 0.2% overall were referred for specialized treatment to the Army Substance Abuse Program.

This study was intended to provide the DoD with targeted information to improve responsiveness to postdeployment problems among those who have served in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. We used data from the Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study (SUPIC) to update these findings, to examine both at-risk drinking and severe alcohol problems, and in more detail to examine the extent to which the DoD postdeployment health surveillance program identifies at-risk drinking, alone or in conjunction with co-occurring psychological problems, and refers returning service members for additional assessment or care in primary care or elsewhere.25,26 We identify specific factors associated with service members receiving referrals and highlight missed opportunities for early intervention.

METHODS

The SUPIC is a longitudinal, observational study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Rationale, methods, and a description of the SUPIC cohort are provided elsewhere.28 We analyzed cross-sectional PDHA data collected from US Army active duty members within 60 days of their Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom index deployment ending in fiscal years 2008 to 2011.

Data Sources

Data sources include deployment information from the Contingency Tracking System and demographic and military characteristics from the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System.28 Service member self-reported postdeployment symptoms, as well as interviewing provider assessment and report of referrals, were from the PDHA (DD 2796, version 2008).

Sample

From the SUPIC cohort of US Army active duty members with an index deployment ending in fiscal years 2008 to 2011 (n = 434 986), we selected a subsample that had a matched 2008 version PDHA (n = 333 803) with an algorithm described elsewhere.28

Measures

Alcohol measures.

US Army active duty members reported how often they had 6 or more drinks on 1 occasion. We defined binge drinking as any report of drinking 6 or more drinks on 1 occasion and note that a more conservative definition is promoted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.29 Own concern of alcohol misuse was based on endorsement of either item on the Two-Item Conjoint Screen: “Did you use alcohol more than you meant to?” and “Have you felt that you wanted to or needed to cut down on your drinking?”27 At-risk drinking and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions [AUDIT-C] scores of 8 or higher were based on the AUDIT-C, a 12-point scale based on 3 questions (each coded 0–4): (1) How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? (2) How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? and (3) How often do you have 6 or more drinks on 1 occasion? Respondents screen positive for at-risk drinking with scores of 3 or higher for women or 4 or higher for men. The AUDIT-C is a validated screen for at-risk drinking and alcohol use disorders that has been used with military populations, as well as in the Veterans Health Administration.30–35 The US Department of Veterans Affairs/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders36 recommends referral to a specialist for treatment of substance use disorders with an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher, which may be indicative of alcohol dependence or severe alcohol problems.37,38 We also classified AUDIT-C scores into risk zones based on a published gender-specific algorithm that associates the distribution of scores with the probability of current alcohol dependence.39

Provider-assessed alcohol problem.

Interviewing providers report their own assessment of whether the service member has an alcohol problem based on their review of the self-reported alcohol items, AUDIT-C score, and any further assessments they conduct. Their recorded response is either no evidence of alcohol problem, potential alcohol problem, or potential alcohol problem and refer to primary care.

Psychological health, behavioral risk, and traumatic brain injury.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was assessed with the Primary Care-PTSD, a 4-item screen that measures symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and numbing in the past 30 days. Endorsement of 3 or more items was considered a positive screen.40–42 The 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) screened for depression by assessing how emotional problems affected members’ functioning in the past month; a total score of 3 or higher was considered positive.43 We defined harmful thoughts as a “yes” or “unsure” response to either of 2 items that interviewing providers directly administered by asking members if they had been bothered by thoughts in the past month of being “better off dead or hurting yourself in some way” or had “thoughts or concerns that you might hurt or lose control with someone.” A positive screen for traumatic brain injury with postconcussive symptoms was scored consistent with Veterans Health Administration/DoD definitions and was based on self-reported items of an injury event during deployment, accompanied by either an alteration or a loss of consciousness, and at least 1 postconcussive symptom after the event and in the past week (e.g., memory problems, headaches).24,44,45

Demographics, deployment, health status.

Demographics, obtained from the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System, were measured at the beginning of the index deployment and consisted of rank (officer, enlisted), gender, race (Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, other, White), marital status (divorced, other, married), and residence region (North, South, West/Alaska, outside of continental United States, other). Deployment events were based on self-report about the index deployment from the PDHA and included wounded, injured, assaulted, or hurt; seen 4 or more times in sick call; and number of combat exposures (encountered dead bodies or saw people killed or wounded, engaged in direct combat and discharged a weapon, felt in great danger of being killed). Length of index deployment (1–11, 12, or > 12 months) was obtained from the Contingency Tracking System. Health status was assessed from the PDHA by asking members to rate their health in the past month.

Interest in discussing concerns.

Members checked items indicating if they (1) would like a health care visit to discuss a health concern; (2) were interested in information or assistance for stress, emotional, or alcohol problems or for a family or relationship concern; and (3) sought during deployment, or intend to seek, mental health counseling.

Provider referral (dependent variable) and other responses.

From the matched PDHA, we examined the checklist of items where the provider indicated the type of referral made, if any, and whether he or she offered health education or provided information on health care benefits or other resources information. For analysis of behavioral health referrals, the dependent variable was the provider’s check that a referral to be seen within 30 days was made to any of 4 settings: primary care/family practice, behavioral health in primary care/family practice, mental health specialty care, or substance abuse program. We used this broader definition because an appropriate response to a positive screen may be a follow-up assessment conducted in primary care or a specialty program. Providers also indicated if the member declined the interview or refused a referral.

Statistical analysis.

We estimated the prevalence of alcohol problems for each alcohol measure separately and, among those with positive test results, calculated the percentage assessed as having a problem by the interviewing provider. We compared the distribution of deployment events and psychological comorbidities among those who were screened or assessed as positive with those who were screened or assessed as negative. Because of the large sample size, we did not report P values; rather, we emphasized the magnitude of the differences.

We used multivariate logistic regression to model the odds of referral to be seen for care within 30 days. All models were adjusted for demographics, deployment events, health status, and traumatic brain injury. To determine whether a positive alcohol screen or assessment increased the odds of referral when psychological comorbidities were controlled, we fit a series of models including PTSD, depression, and harmful thoughts (separate indicator variables) alone and in combination with a measure of alcohol problems (separate models: AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher; interviewing provider–assessed alcohol problem; and a combination of the 2: positive for AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher only, interviewing provider–assessed alcohol problem only, or both, vs neither).

To estimate the predicted percentage of US Army active duty members who would be referred, with or without alcohol or psychological problems, we calculated the predicted probability from a multivariate logistic regression and expressed the probability as a percentage. The model was adjusted for the characteristics included in the previously discussed models, with the psychological comorbidities replaced with a single yes-or-no variable, and alcohol problems measured with the AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher. Each characteristic was set to the modal value of the sample: enlisted, male, White, married, Southern region, index deployment 1 to 11 months, high combat exposure, no traumatic brain injury, and self-reported health status as excellent or very good.

We compared the demographic and deployment characteristics of US Army active duty members in the analysis sample with those without a matching PDHA who were excluded (23%) to assess possible selection bias. The major difference was that included members were less likely to have a deployment ending in fiscal year 2008 (7.0% vs 64.7%), a likely consequence of our decision to restrict analysis to the version 2008 PDHA. Other differences between included and excluded members, respectively, were age (6.3% vs 10.8% in 40 years and older age group), rank (11.1% vs 16.2% officer), index deployment longer than 12 months (29.8% vs 51.9%), and having an inpatient facility visit during or after the index deployment (0.6% vs 3.6%).

All calculations were performed with SAS/Base and SAS/STAT software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The analysis sample was predominantly younger (aged 17–24 years; 45.9%) and male (89.8%); other demographic and deployment characteristics of the analysis sample were similar to those reported for all US Army active duty members in the SUPIC.28

Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption and Concerns

More than 70% of US Army active duty members were current drinkers, with more than one third (37.6%) reporting binge drinking (Table 1), of whom 43.9% reported binge drinking at least monthly and 19.4% at least weekly. Nearly 29% were positive for at-risk drinking according to gender-specific AUDIT-C cutpoints for which further assessment and brief intervention are recommended.39 About 5.6% had an AUDIT score of 8 or higher. Despite self-report of frequent episodes of excessive drinking, only 3.6% reported concerns about drinking too much or needing to cut down.

TABLE 1—

Self-Reported Postdeployment Alcohol Consumption and Concerns in US Army Active Duty Members With an Index Deployment Ending in Fiscal Years 2008 to 2011, by Interviewing Provider–Assessed Alcohol Problem: Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study

| Interviewing Provider–Assessed Alcohol Problem, No. (%) |

|||

| Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption and Concerns | Total Respondents, No. (%) | Yes | No |

| Total | 333 803 (100) | 62 626 (18.8) | 271 771 (81.4) |

| Binge drinking (≥ 6 drinks on 1 occasion) | |||

| Not a current drinker | 96 734 (29.0) | 768 (0.8) | 95 966 (99.2) |

| Drink but never binge or not marked | 111 542 (33.4) | 4075 (3.7) | 107 467 (96.3) |

| < monthly | 70 374 (21.1) | 22 604 (32.1) | 47 770 (67.9) |

| Monthly | 30 813 (9.2) | 17 771 (57.7) | 13 042 (42.3) |

| Weekly | 21 670 (6.5) | 15 350 (70.8) | 6320 (29.2) |

| Daily | 2670 (0.8) | 2058 (77.1) | 612 (22.9) |

| Any occasion of ≥ 6 drinks | 125 527 (37.6) | 57 783 (46.0) | 67 744 (54.0) |

| Self-reported own concern - TICS positive (1 or 2 “yes” responses)a | 12 164 (3.6) | 9007 (74.0) | 3157 (26.0) |

| AUDIT-C | |||

| Positiveb | 95 974 (28.8) | 59 276 (61.8) | 36 698 (38.2) |

| AUDIT-C or TICS positive | 98 043 (29.4) | 60 562 (61.8) | 37 481 (38.2) |

| Score ≥ 8b | 18 826 (5.6) | 14 101 (74.9) | 4725 (25.1) |

| Risk zones (men only)c | |||

| 0–2 | 184 026 (61.4) | 2298 (1.2) | 181 728 (98.8) |

| 3–4 | 54 553 (18.2) | 15 662 (28.7) | 38 891 (71.3) |

| 5–6 | 33 294 (11.1) | 19 875 (59.7) | 13 419 (40.3) |

| 7–9 | 22 031 (7.4) | 15 289 (69.4) | 6742 (30.6) |

| 10–12 | 5859 (2.0) | 4683 (79.9) | 1176 (20.1) |

| Risk zones (women only) | |||

| 0–1 | 22 367 (65.7) | 171 (0.8) | 22 196 (99.2) |

| 2 | 3883 (11.4) | 80 (2.1) | 3803 (97.9) |

| 3 | 2998 (8.8) | 1593 (53.1) | 1405 (46.9) |

| 4–6 | 3908 (11.5) | 2327 (59.5) | 1581 (40.5) |

| 7–9 | 748 (2.2) | 552 (73.8) | 196 (26.2) |

| 10–12 | 136 (0.4) | 96 (70.6) | 40 (29.4) |

Responses to the Two-Item Conjoint Screen (TICS): indicated drinking more than wanted to or reported needing or wanting to cut down on drinking. The TICS is positive if respondent answers affirmatively to either concern.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) screens for at-risk drinking and is the sum of 3 consumption items with possible scores ranging from 0 to 12; positive for women ≥ 3, for men ≥ 4. Scores of 8 or higher indicate severe alcohol problems.

Risk zones are consistent with those used in Rubinsky et al.39

Almost one fourth (22.9%) of US Army active duty members who reported binge drinking daily were assessed as not having an alcohol problem by the interviewing provider. Similarly, one fourth (25.1%) of those with an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher suggestive of severe alcohol problems were assessed as not having an alcohol problem. Among those with the highest AUDIT-C risk zone scores of 10 to 12, the interviewing provider assessed 20.1% of men and 29.4% of women as not having an alcohol problem.

Self-Reported Combat Experiences and Psychological Comorbidities

Overall, deployment events and psychological comorbidities were more prevalent among those screening positive compared with those screening negative for each alcohol measure shown in Table 2. In particular, those with AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher had the highest prevalence of deployment events and possible psychological comorbidity; 64.9% reported at least 1 deployment event or had a positive psychological screen. Additionally, 22% expressed interest in a health care visit to discuss health concerns, and 10.3% said that they sought help or intended to seek counseling for a mental health concern; a minority was interested in assistance for stress, an emotional problem, or an alcohol concern (7%) or family or relationship problems (4%; data not shown).

TABLE 2—

Self-Reported Deployment Events and Postdeployment Screen Results in US Army Active Duty Members With an Index Deployment Ending in Fiscal Years 2008 to 2011, by Alcohol Status: Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study

| AUDIT-Ca or TICSb |

AUDIT-C Score ≥ 8a |

Interviewing Provider–Assessed Alcohol Problem |

|||||

| Self-Reported Responses | Positive, No. (%) | Negative, No. (%) | Positive, No. (%) | Negative, No. (%) | Positive, No. (%) | Negative, No. (%) | Total Respondents, No. (%) |

| Total | 98 043 (100) | 235 760 (100) | 18 826 (100) | 314 977 (100) | 62 626 (100) | 271 177 (100) | 333 803 (100) |

| Deployment events (during index deployment) | |||||||

| Wounded, injured, or assaulted | 19 482 (19.9) | 37 254 (15.8) | 4350 (23.1) | 52 386 (16.6) | 12 839 (20.5) | 43 897 (16.2) | 56 736 (17.0) |

| Seen by health care provider ≥ 4 times | 20 003 (20.4) | 40 336 (17.1) | 4383 (23.3) | 55 956 (17.8) | 13 033 (20.8) | 47 306 (17.4) | 60 339 (18.1) |

| Postdeployment screen results | |||||||

| TBI with postconcussive symptoms positivec | 6596 (6.7) | 8495 (3.6) | 2072 (11.0) | 13 019 (4.1) | 4589 (7.3) | 10 502 (3.9) | 15 091 (4.5) |

| PC-PTSD positived | 8507 (8.7) | 10 397 (4.4) | 2712 (14.4) | 16 192 (5.1) | 5969 (9.5) | 12 935 (4.8) | 18 904 (5.7) |

| Depression (PHQ-2) positivee | 11 079 (11.3) | 14 524 (6.2) | 3965 (21.1) | 21 638 (6.9) | 7760 (12.4) | 17 843 (6.6) | 25 603 (7.7) |

| Harmful thoughtsf | 2308 (2.4) | 2958 (1.3) | 792 (4.2) | 4474 (1.4) | 1783 (2.8) | 3483 (1.3) | 5266 (1.6) |

| Difficulty with emotional problems in past month (somewhat, very, extremely) | 31 322 (31.9) | 54 985 (23.3) | 8074 (42.9) | 78 233 (24.8) | 21 006 (33.5) | 65 301 (24.0) | 86 307 (25.9) |

| Any deployment event or positive for any postdeployment screens | 52 547 (53.6) | 100 430 (42.6) | 12 226 (64.9) | 140 751 (44.7) | 34 501 (55.1) | 118 476 (43.6) | 152 977 (45.8) |

Note. AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions; PC-PTSD = Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; PHQ-2 = 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire; TBI = traumatic brain injury; TICS = Two-Item Conjoint Screen.

The AUDIT-C screens for at-risk drinking and is the sum of 3 consumption items with possible scores ranging from 0 to 12; positive for women ≥ 3, for men ≥ 4. Scores of 8 or higher indicate severe alcohol problems.

The TICS: indicated drinking more than wanted to or reported needing or wanting to cut down on drinking. The TICS is positive if respondent answers affirmatively to either concern.

Positive screen for TBI with postconcussive symptoms in the past week.

Past-month PTSD, based on the PC-PTSD screen, which is positive if the respondent endorses any 3 items out of 4 about PTSD symptoms.

The PHQ-2 is a screening test for depressed mood or anhedonia in the past month; scores range from 0 to 6, with 3 or higher being positive.

Based on response to 2 items, thinking about either harming self or harming others in the past month when asked by Post-Deployment Health Assessment provider.

Provider Referrals and Other Actions

Overall, 24.5% of US Army active duty service members were referred to be seen within 30 days of the health assessment in primary care/family practice, behavioral health in primary care/family practice, mental health specialty care, or a substance abuse program. Fewer than 1.0% of members declined a provider interview, and fewer than 2.0% refused a referral (data not shown). Having a provider-assessed alcohol problem was associated with an increased likelihood of referral. Among US Army active duty members with AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher, 23.2% were referred if no alcohol problem was identified compared with 40.1% of those with a potential alcohol problem identified. Among those with a positive depression screen, 54.5% were referred for a provider-identified potential alcohol problem compared with 44.3% in those with no alcohol problem (data not shown).

Of US Army active duty members for whom a potential alcohol problem was identified, 1.7% were referred to a substance abuse program, 5.5% to mental health specialty care, 8.2% to behavioral health in primary care/family practice, and 24.4% to primary care/family practice. These referrals were not mutually exclusive, and the reason for referral was unknown. Additionally, among those identified with a provider-assessed alcohol problem (18.8% of the full sample), interviewing providers reported that they provided health education to 69.5% and noted that some were already under care for physical symptoms or a psychological problem, 11.0% and 4.8%, respectively (data not shown).

In terms of those returning service members who expressed interest in further assistance, even though providers were more likely to refer US Army active duty members who requested assistance than those who did not, the majority (51.8%) wanting a health care visit or wanting assistance with a family or relationship problem (50.8%) were not referred, and a large minority (43.0%) wanting assistance with stress, emotions, or an alcohol concern, or wanting to cut down on drinking (43.0%), were not referred (data not shown).

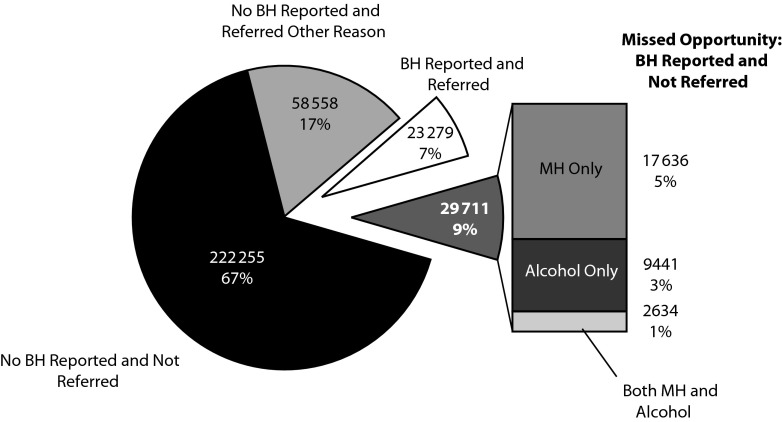

Missed Opportunity Analysis

Figure 1 displays the composition of the US Army active duty sample on both postdeployment screening characteristics and referral disposition, using the stringent criterion of AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher. The majority (67%) of US Army active duty members returning from deployment did not meet any psychological or alcohol self-report screening criteria and did not receive a referral. The second largest group was composed of US Army active duty who received a referral but did not screen positive for any psychological or alcohol problem (17.5%); presumably, the referral was for a physical issue. Seven percent had 1 or more positive psychological or alcohol screens and were referred. The referred group was smaller than the “missed opportunity” group of US Army active duty members with 1 or more positive psychological or alcohol screen(s) and not referred (8.9%). Of the missed opportunity group, 41% had a positive AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher.

FIGURE 1—

Postdeployment behavioral health screening and referral results in US Army active duty members with an index deployment ending in fiscal years 2008 to 2011: Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study.

Note. BH = behavioral health; MH = mental health. Alcohol indicates a score of 8 or higher (severe alcohol problems) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C). BH indicates either MH or alcohol. MH refers to a positive screen for past-month posttraumatic stress disorder, depression (2-item Patient Health Questionnaire), or harmful thoughts. Referred indicates referred to be seen for care within 30 days of postdeployment screen to any of the following: primary care, BH in primary care, MH specialty care, or substance abuse program.

Factors Associated With Referral

In a multivariate regression model that controlled for demographic, deployment, and health status (Table 3), fair or poor health was associated with increased odds of being referred (model 1; adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.22; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.14, 3.30), and traumatic brain injury was associated with increased odds of referral (AOR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.69, 1.82). In model 2, psychological comorbidities were associated with increased odds of referral, particularly harmful thoughts (AOR = 4.47; 95% CI = 4.18, 4.76), and the magnitude of the AORs for combat and physical health measures was slightly reduced.

TABLE 3—

Characteristics Associated With the Odds of Referral to Be Seen for Care Within 30 Days in US Army Active Duty Members With an Index Deployment Ending in Fiscal Years 2008 to 2011: Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study

| Multivariate Logistic Model, AOR (95% CI)a |

|||||

| Characteristics | Referral to Be Seen for Care Within 30 Days, No. (%) | Model 1: Base Model | Model 2: Add Psychological Comorbidities | Model 3: Add Interviewing Provider–Assessed Alcohol Problem | Model 4: Add AUDIT ≥ 8 by Interviewing Provider–Assessed Alcohol Problem |

| Combat exposureb | |||||

| None (Ref) | 40 334 (20.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 20 165 (27.7) | 1.30 (1.28, 1.33) | 1.23 (1.20, 1.25) | 1.21 (1.18, 1.23) | 1.21 (1.18, 1.24) |

| 2 | 12 428 (30.5) | 1.40 (1.36, 1.43) | 1.25 (1.22, 1.29) | 1.22 (1.19, 1.26) | 1.22 (1.19, 1.26) |

| 3 | 8910 (35.2) | 1.56 (1.51, 1.61) | 1.37 (1.33, 1.42) | 1.33 (1.29, 1.37) | 1.33 (1.28, 1.37) |

| Health status, past month | |||||

| Excellent or very good (Ref) | 30 723 (16.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Good | 34 855 (30.4) | 1.92 (1.89, 1.96) | 1.80 (1.77, 1.84) | 1.78 (1.75, 1.82) | 1.78 (1.75, 1.82) |

| Fair or poor | 16 168 (45.8) | 3.22 (3.14, 3.30) | 2.64 (2.57, 2.71) | 2.61 (2.54, 2.68) | 2.61 (2.54, 2.68) |

| Wounded, injured, assaultedc | 22 797 (40.2) | 1.77 (1.73, 1.81) | 1.77 (1.73, 1.80) | 1.76 (1.73, 1.80) | 1.77 (1.73, 1.80) |

| TBI with postconcussive symptoms positived | 7631 (50.6) | 1.75 (1.69, 1.82) | 1.48 (1.42, 1.53) | 1.46 (1.41, 1.52) | 1.46 (1.40, 1.52) |

| PC-PTSD positivee | 10 112 (53.5) | NA | 1.86 (1.80, 1.93) | 1.83 (1.77, 1.89) | 1.83 (1.76, 1.89) |

| Depression (PHQ-2) positivee | 12 128 (47.4) | NA | 1.60 (1.55, 1.65) | 1.56 (1.51, 1.61) | 1.55 (1.51, 1.60) |

| Harmful thoughts positivee | 3766 (71.5) | NA | 4.47 (4.18, 4.76) | 4.36 (4.09, 4.66) | 4.36 (4.08, 4.65) |

| Interviewing provider–assessed alcohol problem | 20 797 (33.2) | NA | NA | 1.46 (1.43, 1.49) | NA |

| AUDIT-C score ≥ 8 by interviewing-provider–assessed alcohol problem | |||||

| AUDIT ≥ 8 positive only | 1095 (23.2) | NA | NA | NA | 0.80 (0.75, 0.86) |

| Interviewing provider–assessed alcohol problem only | 15 141 (31.2) | NA | NA | NA | 1.39 (1.36, 1.43) |

| Both positive | 5656 (40.1) | NA | NA | NA | 1.66 (1.60, 1.73) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; AUDIT-C 8+ = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions score of 8 or higher; CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable; PC-PTSD = Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; PHQ-2 = 2-Item Patient Health Questionnaire; TBI = traumatic brain injury. Referral to be seen for care within 30 days of postdeployment screen to any of the following: primary care, behavioral health in primary care, mental health specialty care, or substance abuse program.

Each model adjusted for demographics (rank group, gender, race, marital status, residence region), length of index deployment, and the characteristics shown in the column.

Self-report of number of types of combat exposures during index deployment: encountered dead bodies or saw people killed or wounded, engaged in direct combat and discharged a weapon, felt in great danger of being killed.

During index deployment.

Positive screen for TBI with postconcussive symptoms in the past week.

PC-PTSD positive if the respondent endorsed any 3 items of 4 past-month PTSD symptoms. Depression: PHQ-2; screening test for depressed mood or anhedonia in past month; scores range from 0 to 6, with 3 or higher being positive. Behavioral risk: based on response to 2 items, thinking about either harming self or harming others in the past month when asked by Post-Deployment Health Assessment provider.

In model 3, members with provider-identified alcohol problems had increased odds of referral (AOR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.43, 1.49). We substituted the provider-identified alcohol problem with an indicator for an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher and found that the odds ratio was smaller in magnitude (AOR = 1.32; 95% CI = 1.28, 1.37; data not shown). Model 4 found that those who had an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher only had reduced odds of referral (AOR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.75, 0.86) relative to those with AUDIT-C scores lower than 8 and for whom the interviewing provider did not assess an alcohol problem. Members with a provider-identified alcohol problem only, or in conjunction with an AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher, had increased odds of referral. Other variables associated with increased odds of referral were enlisted rank, female gender, Black or other race, being married, and an index deployment lasting 1 to 11 months (data not shown).

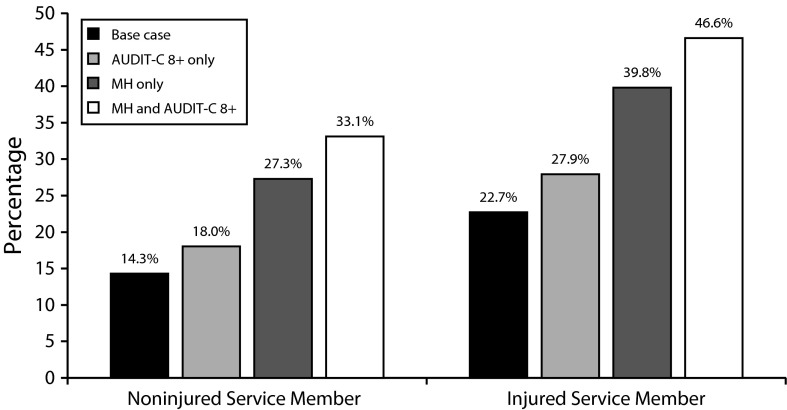

Effect of Alcohol Risk on Referral

To examine the effect of alcohol versus psychological problems on referral, we estimated the proportion of the sample that would be referred if either or both of these problems were present (Figure 2). We reported results separately by injury status for hypothetical US Army active duty members. Of those screening negative for alcohol or psychological comorbidities (i.e., base case), the predicted percentage referred was 14.3% for noninjured and 22.7% for injured. An AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher was associated with a small incremental increase in the proportion referred: less than 4 percentage points for noninjured and about 5 percentage points for an injured US Army active duty member. Screening positive for a psychological comorbidity led to greater increments in referral (13.0 and 17.1 percentage points, respectively). An AUDIT-C score of 8 or higher co-occurring with a psychological comorbidity led to an incremental increase over psychological problems alone of 6 or 7 percentage points, respectively. Importantly, for the scenario of a hypothetical injured US Army active duty member, we estimated that the majority (53.4%) of those returning with psychological and alcohol-related comorbidities were not referred.

FIGURE 2—

Predicted percentage of US Army active duty members with an index deployment ending in fiscal years 2008 to 2011 referred to be seen for care within 30 days: Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study.

Note. AUDIT-C 8+ = severe alcohol problems on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test alcohol consumption questions; MH = mental health. Base case indicates negative screen for AUDIT-C 8+ and negative screens for MH. Injured indicates self-report of being wounded, injured, assaulted, or otherwise hurt during index deployment. MH refers to a positive screen for past-month posttraumatic stress disorder, depression (2-Item Patient Health Questionnaire), or harmful thoughts. Referred indicates referred to be seen for care within 30 days of postdeployment screen to any of the following: primary care, behavioral health in primary care, MH specialty care, or substance abuse program. Predicted percentages were estimated from multivariate logistic regression model of odds of referral and adjusted for demographic, deployment, and combat characteristics and health status. Each characteristic was set to modal value of sample: enlisted rank, male, White, married, residing in southern region, index deployment lasting 1–11 months, high combat exposure (saw wounded, injured, or killed; engaged in combat and discharged weapon; and felt in danger of being killed), and self-reported excellent or very good health in past month.

DISCUSSION

We examined postdeployment at-risk drinking and other alcohol measures in combination with postdeployment screening results for PTSD, depression, and harmful thoughts, all intended to identify service members at increased risk for developing problems when reintegrating into their families and military communities.36,46 We provided an update and refinement of referral estimates previously reported by Hoge et al.26 and Milliken et al.25 by examining newer deployment cohorts and using the revised (2008) PDHA assessment, which includes alcohol quantity and frequency measures. This study examined referral to primary care (and other) settings for further assessment or follow-up care, settings appropriate for early intervention and preventive counseling, reflective of the military’s attempts to destigmatize help seeking for postdeployment psychological concerns.47 Although the DoD’s postdeployment health surveillance program has evolved, our main finding was that interviewing providers referred for a follow-up visit only 29.2% of at-risk drinkers and only 35.9% of those with AUDIT-C scores suggestive of severe alcohol problems. We also confirmed the previously reported low rates of postdeployment referral for other mental health issues, including PTSD and depression.25,26 Multivariate models showed that US Army active duty members with a provider-assessed alcohol problem had increased odds of receiving a referral; however, the odds of referral were greater for those with other psychological issues. Although these low referral rates may be associated with service member refusal or reluctance,48–54 our findings did not confirm this assumption because fewer than 2.0% refused a referral. Furthermore, of those expressing interest in assistance, most were not referred.

Among service members who reported being current drinkers, 23.0% reported binge drinking at least monthly. This estimate is low relative to estimates of binge drinking reported on anonymous DoD surveys, ranging from 40% to 56%,3,8 and likely an underestimate, but this estimate confirms that postdeployment risky drinking is common and should raise concern. Results indicate that inclusion of objective alcohol measures (frequency and quantity of drinking) provides a more troubling picture than members’ own concerns or provider-identified alcohol problems. US Army active duty members appeared unaware or unwilling to express concern about their own alcohol consumption, with only 3.6% reporting concern, a lower estimate than the 11.8% reporting concern on the PDHRA among an earlier cohort in the Milliken et al.25 study, as well as the 31.5% of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Army members reporting concern on an anonymous survey in 2003 to 2006.55 Despite low concern about their alcohol consumption, 6.7% reported interest in assistance with stress, an emotional problem, or an alcohol concern, and 10.3% sought mental health help during deployment or reported intending to seek help. Furthermore, interviewing providers underidentified potential alcohol problems; they identified a problem among only 74.9% of those with AUDIT-C scores of 8 or higher and in 79.9% and 70.6% of men and women, respectively, with the highest AUDIT-C risk zone scores of 10 to 12.39 Although we expect some false-positive results when examining screening data only, these gaps are too large to be explained solely by false-positive results, especially among the highest scores. Thus, the negative consequences of at-risk drinking appear either misunderstood or minimized in the postdeployment health surveillance program, consistent with what was reported previously.25 Most importantly, even for service members returning with indicators of both psychological problems and severe alcohol problems, there was no indication of referral for a follow-up visit.

Limitations of the Study

Several factors limited our findings. First, we excluded members who completed the older version of the PDHA and those with date fields on the deployment record and PDHA form that were a poor match (i.e., outside a 60-day window), which reduced inclusion of many 2008 cohort members. Second, the reliability and validity of the PDHA alcohol measures for Army members have not been established, and 1 study found unsatisfactory reliability among a sample of air force members on a similar instrument56 and poor diagnostic metrics.57 We have concern about the ambiguous time frame of alcohol questions on the PDHA, which may lower the reliability. Furthermore, the PDHA or PDHRA is neither voluntary nor anonymous, and its administration immediately postdeployment has been criticized as not conducive to obtaining honest reports from service members.58–60 Lack of anonymity would contribute to underreporting on these self-report measures, which may have resulted in our lower estimates. Furthermore, if interviewing providers perceive that the screening scores are unreliable, they may hesitate to recommend follow-up appointments; nevertheless, they are trained to administer additional assessments for those screening positive.61 If the provider administers a longer assessment in response to a positive screen or provides a brief intervention, there is no record of these actions or assessment results. Lacking this information, we cannot determine whether the member screened negative on a further assessment or if the provider used his or her own judgment when reporting that a service member did not have a potential alcohol problem.

Other limitations associated with administration of the PDHA affect its usefulness for research purposes. Specifically, the program lacks data about where the PDHA was completed and whether the provider-administered interview actually occurred, duplicate administrations are frequent, and no information is kept on the credentials of the interviewing provider. Whether the PDHA interviewing providers receive enough training to screen and competently advise members or if the environment supports such interaction is unknown. Additionally, the absence of a checkmark is interpreted as a “no” when indeed the provider may have skipped the item.

Despite these limitations, we believe this study identified important missed opportunities to improve health outcomes of service members returning from combat deployments. Focusing on only identifying people with dependence or abuse is a missed opportunity for prevention. Even though excessive drinking is often perceived as a normative behavior in this population, particularly during homecoming celebrations, we know that episodic binge drinking and at-risk drinking immediately postdeployment can lead to problems in readjustment, especially when returnees drink to alleviate symptoms associated with posttraumatic responses or in combination with other psychological problems.7,8 For example, among active duty current drinkers responding to a 2008 anonymous DoD survey, binge drinking at least weekly and screening positive for possible alcohol dependence were each associated with greater negative consequences (e.g., driving while under the influence or being kept from duty for at least a week because of a drinking-related illness).8 Hence we would argue that this time of transition is an opportune time for brief preventive messages in a population known to engage in risky drinking.

It is unknown whether the PDHA identifies postdeployment symptoms that predict future complications.62 We have research under way to examine whether at-risk drinking identified in the postdeployment health surveillance program is associated with negative outcomes. Ample research, however, indicates that alcohol screening followed by brief alcohol counseling in primary care settings reduces at-risk drinking and future alcohol-related problems.63–66 The delivery of health-promoting and harm-reducing messages about alcohol use may be most effective when done early, particularly after a period of enforced abstinence, consistent with current US Department of Veterans Affairs/DoD guidelines and Institute of Medicine recommendations.1,36

Some have expressed caution about universal screening programs in the military.60 One concern is that the best practice in screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for alcohol problems is for the screening and advice to occur in confidential settings, conditions that do not currently exist in the postdeployment program.1,32,57 Because of lack of confidentiality and other program limitations described earlier, the program’s utility for both reliable surveillance estimates and for optimal intervention is hampered. Lack of confidentiality and the timing of the PDHA so close to the deployment end date contribute to underreporting. Because PDHAs are not administered in a health setting with trained providers, there are constraints on opportunities for effective early intervention at the time of completion. To increase clinical value, the postdeployment surveillance program should be redesigned to emphasize confidential reporting of psychological problems in a clinical setting designed to offer brief counseling and advice or follow-up as needed. This program change would be supported by the DoD’s recent instruction that provided guidance to military health providers outlining the types of conversations and counseling about alcohol use and mental health that need not be reported to command.67

In October 2013, the DoD issued DoD Instruction 6490.12 to the services to implement significant changes to the postdeployment health surveillance program.68 Changes included requiring that the assessments be administered by a trained licensed mental health professional or certified health care provider in a private setting to foster openness and trust. Furthermore, the existing timing of the PDHA or PDHRA was to be replaced with 3 assessments to be completed at 90 to 180 days postdeployment, 181 days to 18 months, and 18 to 30 months after return. The instruction requires that providers conduct a brief intervention for those who screen positive for risky drinking and provide referral for treatment, as needed.

Given that improvements are planned for the postdeployment surveillance program, an opportunity exists to study the implementation of these changes, including compliance with provision of brief counseling, and to study the effectiveness of training that supports the providers who will perform the screening and assessments. This implementation research should be accompanied by quality improvement strategies such as providing feedback to provider groups or installations on progress toward compliance with the instruction and problem solving or technical assistance to identify and overcome implementation barriers. Data collection on implementation barriers can be strategic and based on periodic samples. However, improved documentation of the steps taken by providers should include use of standardized protocols for further assessment of positive screens, assessment results, documentation of advice given, and rationale when an indicated referral is not made. The implementation of standardized assessments for positive screens by interviewing providers may increase early identification and intervention rates, as well as standardize the response of military providers across settings and conditions under which assessments are administered. Following these protocols also may destigmatize problems and lead to more returnees seeking counseling and support in future months, perhaps reducing future problems.

Conclusions

These findings point to important considerations for the development of more comprehensive strategies to improve the capability of DoD programs to meet the psychological health needs of service members with disorders or conditions associated with, or aggravated by, deployment into a combat theater. The results identified the vital role of a screening and surveillance program, but other important avenues remain to reach those who will need help. To be comprehensive in addressing alcohol problems, individual-based strategies such as screening should be coupled with environmental policy changes that aim to change the culture of alcohol use in the military69 and should change other aspects of the climate or norms about alcohol use.1 To this end, exploring the effectiveness of new breathalyzer deterrence programs announced by the Navy and Marines would be important.70,71 The results underscore a continued role for military leaders, military unit peers, medical providers, families, and community resources to provide other broad-based, comprehensive efforts when screening programs are 1 component but not the sole response to postdeployment problems.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; grant R01DA030150).

We gratefully acknowledge Kennell and Associates, Inc., for compiling the data used in these analyses, as well as Thomas V. Williams and Diana D. Jeffery, the study’s Defense Health Agency (DHA), Department of Defense (DoD), government project managers.

Note. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs/DHA and the Army’s Office of the Surgeon General of the US DoD provided access to these data. The opinions and assertions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the DoD, NIDA, or the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

This research has been conducted in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Brandeis University’s Committee for Protection of Human Subjects and the Human Research Protection Program at the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs/Defense Health Agency (DHA) conducted the study’s institutional review board. The DHA Privacy and Civil Liberties Office executed annual data use agreements.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Substance Use Disorders in the US Armed Forces. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA. Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Mil Med. 2010;175(6):390–399. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlas FM, Higgins WB, Pflieger JC, Diecker K. 2011 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel. Fairfax, VA: ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS. Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Substance Abuse Research. Military Personnel More Likely to Binge Drink than Household Residents; Largest Discrepancy Seen Among Underage Youth and Young Adults. Vol 182009 Available at: http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/cesarfax/vol18/18-07.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattiko MJ, Olmsted KLR, Brown JM, Bray RM. Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addict Behav. 2011;36(6):608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santiago PN, Wilk JE, Milliken CS, Castro CA, Engel CC, Hoge CW. Screening for alcohol misuse and alcohol-related behaviors among combat veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(6):575–581. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams RS, Larson MJ, Corrigan JD, Ritter GA, Williams TV. Traumatic brain injury among US active duty military personnel and negative drinking-related consequences. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:821–836. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.797995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harwood HJ, Zhang Y, Dall TM, Olaiya ST, Fagan NK. Economic implications of reduced binge drinking among the military health system’s TRICARE Prime plan beneficiaries. Mil Med. 2009;174(7):728–736. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-03-9008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lande RG, Marin BA, Chang AS, Lande GR. Survey of alcohol use in the US Army. J Addict Dis. 2008;27(3):115–121. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams J, Jones SB, Pemberton MR, Bray RM, Brown JM, Vandermaas-Peeler R. Measurement invariance of alcohol use motivations in junior military personnel at risk for depression or anxiety. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252–257. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Army Suicide Prevention Task Force. Army Health Promotion Risk Reduction Suicide Prevention Report. 2010. Available at: http://usarmy.vo.llnwd.net/e1/HPRRSP/HP-RR-SPReport2010_v00.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2011.

- 14.Luxton DD, Osenbach JE, Reger MA DoDSER Department of Defense Suicide Report: Calendar Year 2011 Annual Report. Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury: The National Center for Telehealth & Technology; 2012. Available at: http://www.t2.health.mil/programs/dodser. Accessed January 13, 2013.

- 15. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Absolute and Relative Morbidity Burdens Attributable to Various Illnesses and Injuries, US Armed Forces, 2011. 2012. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report. 2012;19(4):1–9.

- 16.Adams RS, Larson MJ, Corrigan JD, Horgan CM, Williams TV. Frequent binge drinking after combat-acquired traumatic brain injury among active duty military personnel with a past year combat deployment. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012;27(5):349–360. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318268db94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong AL, Joseph AR. Referrals for alcohol use problems in an overseas military environment: description of the client population and reasons for referral. Mil Med. 2008;173(9):871–877. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.9.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spera C, Thomas RK, Barlas F, Szoc R, Cambridge MH. Relationship of military deployment recency, frequency, duration, and combat exposure to alcohol use in the air force. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(1):5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilk JE, Bliese PD, Kim PY, Thomas JL, McGurk D, Hoge CW. Relationship of combat experiences to alcohol misuse among US soldiers returning from the Iraq War. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(1-2):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA. 2008;300(6):663–675. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramchand R, Miles J, Schell T, Jaycox L, Marshall GN, Tanielian T. Prevalence and correlates of drinking behaviors among previously deployed military and matched civilian populations. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):6–21. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.534407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bliese PD, Wright KM, Hoge CW. Preventive mental health screening in the military. In: Adler AB, Bliese PD, Castro CA, editors. Deployment Psychology: Evidence-Based Strategies to Promote Mental Health in the Military. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoge CW. Public health strategies and treatment of service members and veterans with combat-related mental health problems. In: Adler AB, Bliese PD, Castro CA, editors. Deployment Psychology: Evidence-Based Strategies to Promote Mental Health in the Military. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deployment Health Clinical Center. Enhanced Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) Process (DD Form 2796). Available at: http://www.pdhealth.mil/dcs/DD_form_2796.asp. Accessed October 1, 2010.

- 25.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, Papasouliotis O. A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(2):95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson MJ, Adams RS, Mohr BA et al. Rationale and methods of the Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat Study (SUPIC): a longitudinal study of Army service members returning from deployment in FY2008-2011. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(10):863–879. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.794840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. 2005. NIH publication 07-3769. Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Publications/EducationTrainingMaterials/guide.htm. Accessed December 8, 2008.

- 30.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE et al. Measuring performance of brief alcohol counseling in medical settings: a review of the options and lessons from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. Subst Abus. 2007;28(4):133–149. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB et al. The Audit Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisen SV, Schultz MR, Vogt D et al. Mental and physical health status and alcohol and drug use following return from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S66–S73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crawford EF, Fulton JJ, Swinkels CM, Beckham JC, Calhoun PS. Diagnostic efficiency of the AUDIT-C in U.S. veterans with military service since September 11, 2001. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Working Group. DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. 2009. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- 37.Funderburk JS, Possemato K, Maisto SA. Differences in what happens after you screen positive for depression versus hazardous alcohol use. Mil Med. 2013;178(10):1071–1077. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinder LS, Bryson CL, Sun H, Williams EC, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and all-cause mortality in male Veterans Affairs patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(2):253–260. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubinsky AD, Kivlahan DR, Volk RJ, Maynard C, Bradley KA. Estimating risk of alcohol dependence using alcohol screening scores. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(1–2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Cabrera O, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Validating the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(2):272–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calhoun PS, McDonald SD, Guerra VS, Eggleston AM, Beckham JC, Straits-Troster K. Clinical utility of the Primary Care–PTSD Screen among US veterans who served since September 11, 2001. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2-validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. United States Government Accountability Office. VA Health Care: Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Screening and Evaluation Implemented for OEF/OIF Veterans, but Challenges Remain. February 2008; GAO-08-276. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08276.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2009.

- 45.Veterans Health Administration. Screening and Evaluation of Possible Traumatic Brain Injury in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harmon SC, Hoyt TV, Jones MD, Etherage JR, Okiishi JC. Postdeployment mental health screening: an application of the Soldier Adaptation Model. Mil Med. 2012;177(4):366–373. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibbs DA, Rae Olmsted KL. Preliminary examination of the Confidential Alcohol Treatment and Education Program. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. US Army Med Dep J. 2008:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Milliken CS. Access to SUD Care: Confidentiality and Stigma Issues. Committee on SUD, Institute of Medicine; 2011. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/∼/media/Files/Activity%20Files/MentalHealth/MilitarySubstanceDisorders/5-3-11ppt2.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2012.

- 50.Ben-Zeev D, Corrigan PW, Britt TW, Langford L. Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. J Ment Health. 2012;21(3):264–273. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.621468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown MC, Creel AH, Engel CC, Herrell RK, Hoge CW. Factors associated with interest in receiving help for mental health problems in combat veterans returning from deployment to Iraq. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(10):797–801. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822fc9bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibbs DA, Rae Olmsted KL, Brown JM, Clinton-Sherrod AM. Dynamics of stigma for alcohol and mental health treatment among Army soldiers. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greene-Shortridge TM, Britt TW, Castro CA. The stigma of mental health problems in the military. Mil Med. 2007;172(2):157–161. doi: 10.7205/milmed.172.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim PY, Britt TW, Klocko RP, Riviere LA, Adler AB. Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment, and utilization of mental health care among soldiers. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):65–81. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke-Walper K, Riviere LA, Wilk JE. Alcohol misuse, alcohol-related risky behaviors, and childhood adversity among soldiers who returned from Iraq or Afghanistan. Addict Behav. 2014;39(2):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon S, Stewart K, Kloc M, Williams TV, Wilmoth MC. The Reliability of a Mental Health Screening & Assessment Instrument Designed for Deployed Members of the Armed Service. Baltimore, MD: Academy Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skopp NA, Swanson R, Luxton DD et al. An examination of the diagnostic efficiency of post-deployment mental health screens. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(12):1253–1265. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hourani L, Bender R, Weimer B, Larson G. Comparative analysis of mandated versus voluntary administrations of post-deployment health assessments among Marines. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):643–648. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T et al. Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1065–1071. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rona RJ, Hyams KC, Wessely S. Screening for psychological illness in military personnel. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1257–1260. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Department of Defense. Training to administer DoD deployment mental health assessments. In: Office of Force Health Protection & Readiness and the Deployment Health Clinical Center. 2010. Available at: http://www.pdhealth.mil/dcs/dod_training_to_administer_dod_mental_health_assessments.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2011.

- 62.Department of Defense. Implementation and Application of Joint Medical Surveillance for Deployments. Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaner EFS, Dickinson HO, Beyer F et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(3):301–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saitz R. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Polen MR, Whitlock EP, Wisdom JP, Nygren P, Bougatsos C. Screening in Primary Care Settings for Illicit Drug Use: Staged Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 58, Part 1. Rockville, MD: Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-Based Practice Center Under Contract 290-02-0024; January 2008. AHRQ publication 08-05108-EF-s, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [PubMed]

- 66.Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Substance Use Disorders (SUD) Washington, DC: The Management of Substance Use Disorders Working Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Department of Defense. Instruction 6490.08: Command Notification Requirements to Dispel Stigma in Providing Mental Health Care to Service Members. Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Department of Defense. Instruction 6490.12: Mental Health Assessments for Service Members Deployed in Connection With a Contingency Operation. Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larson MJ, Wooten NR, Adams RS, Merrick EL. Military combat deployments and substance use: review and future directions. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2012;12(1):6–27. doi: 10.1080/1533256X.2012.647586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Department of the Navy DoD. Letter of instruction for the Marine Corps Alcohol Screening Program. 2013; 5300 MFC4. Available at: http://www.quantico.marines.mil/Portals/147/Docs/Resources/Alcohol%20Screening%20Program%20ASP%20%20LOI%20(3).pdf. Accessed January 8, 2014.

- 71. Department of the Navy DoD. Use of Hand-Held Alcohol Detection Devices. 2013. OPNAVINST 5350.8. Available at: http://www.public.navy.mil/bupers-npc/support/21st_Century_Sailor/nadap/policy/Documents/OPNAVINST%205350.8.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2014.