Abstract

Nail involvement is an extremely common feature of psoriasis and affects approximately 10-78% of psoriasis patients with 5-10% of patients having isolated nail psoriasis. However, it is often an overlooked feature in the management of nail psoriasis, despite the significant burden it places on the patients as a result of functional impairment of manual dexterity, pain, and psychological stress. Affected nail plates often thicken and crumble, and because they are very visible, patients tend to avoid normal day-to-day activities and social interactions. Importantly, 70-80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail psoriasis. In this overview, we review the clinical manifestations of psoriasis affecting the nails, the common differential diagnosis of nail psoriasis, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index and the various diagnostic aids for diagnosing nail psoriasis especially, the cases with isolated nail involvement. We have also discussed the available treatment options, including the topical, physical, systemic, and biological modalities, in great detail in order to equip the present day dermatologist in dealing with a big clinical challenge, that is, management of nail psoriasis.

Keywords: Biologicals, infliximab, intralesional injections, nail biopsy, nail psoriasis, nail psoriasis severity index, nail psoriasis treatment

Introduction

What was known?

Nail psoriasis is a common condition seen in about 10-78% of patients with psoriasis vulgaris and 70-80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

5-10% cases have isolated nail involvement.

The clinical features of nail psoriasis are extremely variable and depend upon the site affected.

Treatment is often difficult, prolonged, and unsatisfactory.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by T-cell-mediated hyperproliferation of keratinocytes in the skin.[1,2] It affects about 2-3% of the world's population with equal sex incidence.[2] Approximately, 10-78% of patients with psoriasis have concurrent nail psoriasis,[3,4,5] while isolated nail involvement is seen in 5-10% of patients.[1,6] Ghosal et al.,[7] in their study found that the frequency of nail changes in patients with Koebner's phenomenon is 56%, whereas as in those without Koebner's phenomenon it is 29.33%. Nail psoriasis is approximately 10% more common in males than in females and is positively associated with higher bodyweight.[8] Recently, a questionnaire-based survey done by Klaassen et al.,[9] revealed that patients with nail psoriasis are more frequently associated with psoriasis capitis, genital psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. Different studies have shown that up to 30% of patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis of which 70-80% have nail involvement.[10,11] Therefore, being a dermatologist, one should look for early signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in a patient with nail psoriasis in order to avoid progressive joint damage.[11,12,13,14]

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) studies have shown that type 1 psoriasis which usually affects the skin is strongly associated with HLA-Cw6[13] and these patients have an earlier onset of disease which is also more extensive and severe, whereas, type 2 psoriasis that predominantly damages the nails and the joints is not associated with HLA Cw6 suggesting a different immunopathology.[2,15,16]

Burden of Nail Psoriasis: The Impact of Nail Psoriasis on Quality of Life

Nail psoriasis engenders both physical and psychological handicap, leading to significant negative repercussions in the quality of life.[4] Cosmetic handicap in nail psoriasis is sometimes so extensive that the patients tend to hide their hands and/or feet or shy away from social and business interactions.[4,11,17] The burden of nail psoriasis on its sufferers can be imagined from the results of a study done by de Jong et al.,[4] in 1728 patients, which showed that nail psoriasis caused significant cosmetic handicap in 93% of patients, restriction of daily housekeeping and professional activities in 60% patients, and 52% patients described pain as a symptom. In 2009, Ortonne et al.,[18] devised the Nail Psoriasis Quality of Life Scale-NPQ10-to evaluate the impact of nail psoriasis on quality of life. The scale correlated well with the Dermatology Life Quality Index. A valid and reliable questionnaire consisting of 10 questions was prepared with all the questions specifically targeting the impact of nail psoriasis on quality of life. The questionnaire was answered by 1309 patients and showed that 86% patients considered nail psoriasis as bothersome, 87% as unsightly, and 59% as painful. Such an impact of nail psoriasis definitely warrants an insight into its clinical manifestations and treatment options by a present day dermatologist.

Clinical Manifestations

Nail psoriasis affects the fingernails more commonly than the toenails.[1]

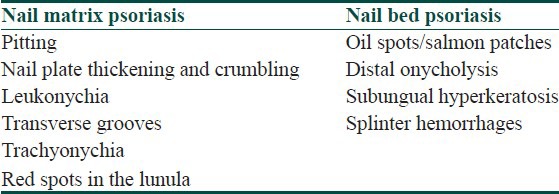

The features of nail psoriasis start predominantly after the onset of cutaneous lesions.[9] A mean delay of 9 and 11.5 years in the onset of nail psoriasis has been reported by van der Velden et al.,[19] and Klaassen et al.,[9] respectively. This time lag, perhaps, is responsible for a lower prevalence of nail psoriasis in children.[9] The clinical manifestations of nail psoriasis depend upon the part of the nail unit affected by nail psoriasis [Table 1].[1]

Table 1.

Clinical signs of nail psoriasis

Common clinical manifestations of nail matrix psoriasis include

Pitting

Pitting is the commonest manifestation of nail psoriasis.[9,20] Pits affect the fingernails more commonly than the toenails.[20] They are superficial depressions in the nail plate that indicate abnormalities in the proximal nail matrix [Figure 1]. Psoriasis affecting the proximal nail matrix disrupts the keratinization of its stratum corneum by parakeratotic cells.[1] These cells are exposed as the nail grows and are sloughed off to form diffuse and coarse pits.[1,21,22] The length of a pit is suggestive of the length of time, the matrix was affected by the psoriatic lesion and a deeper pit is suggestive of involvement of intermediate and ventral matrix along with the dorsal matrix.[21] Pitting may be arranged in transverse or longitudinal rows or it may be disorganized.[21] They may be shallow or large to the point of leaving a punched out hole in the nail plate known as elkonyxis.[22] More than 20 fingernail pits per person are suggestive of a psoriatic etiology and more than 60 pits per person are unlikely to be found in the absence of psoriasis.[23]

Figure 1.

Pitting affecting the fingernails

Transverse grooves are formed in the same way as pits when the psoriatic lesion affects a wider area of the nail matrix [Figure 2].[2]

Figure 2.

Transverse grooves on the nail plate in a patient with psoriasis

Nail plate thickening and crumbling

It suggests an extensive involvement of the entire nail matrix by the psoriatic process [Figure 3].[24]

Figure 3.

Nail plate thickening and crumbling resulting in complete nail dystrophy

Leukonychia

It occurs when psoriasis induced parakeratosis affects only the intermediate and ventral matrices that form the undersurface of a nail plate, as opposed to the dorsal nail matrix. In these situations, the affected area appears leukonychic (whitish) because of the internal desquamation of parakeratotic cells, as opposed to the materialization of pits externally [Figure 4].[1,25]

Figure 4.

Leukonychia in a patient with psoriasis

Clinical manifestations of nail bed psoriasis include

Oil spot or salmon patch

They result from focal nail bed parakeratosis which leads to focal onycholysis, where serum and cellular debris accumulate and become entrapped.[1,26] There is usually a yellowish brown margin visible between the white oily spot or salmon patch lesion and the normal pink nail. Extension of an oil spot to the distal free edge leads to onycholysis [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Onycholysis along with salmon patches on thumbnails in a patient with psoriasis

Onycholysis (separation of nail plate from nail bed)

Results from psoriasis affecting the distal nail bed or hyponychium or extension of oil spots distally. Onycholysis allows air to enter the distal end of the nail plate leading to white color[27] [Figures 5 and 6]. Serum exudates may accumulate and appear yellowish.[28]

Figure 6.

Onycholysis along with pitting and salmon patches in fingernails

Subungual hyperkeratosis

It affects the toenails more frequently than the fingernails.[5] It results from raising of the nail plate off the nail bed as a result of deposition of cells that have not undergone desquamation[1] [Figures 7a and b]. This accumulated tissue is friable and is liable to be infected by Candida and Pseudomonas leading to either yellow/green discoloration.

Figure 7.

(a) Nail plate thickening with discoloration and subungual hyperkeratosis (arrow) of the toenail (b) Subungual hyperkeratosis affecting toenails

Splinter hemorrhages

They are a non specific finding of nail psoriasis and appear as small linear structures, about 2-3 mm long, arranged at the distal end of a nail plate. They reflect the rupture of wide calibre vessels and tracking of extravasated blood down the longitudinal furrows beneath the nail plate.[21]

Other manifestations

Acropustulosis

It is characterized by destructive pustulation of the nail unit which may occur as a part of pustular psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis,[29] and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.[30] The nail plate may be lifted off by sterile pustules in the nail bed and matrix resulting in complete destruction of the nail plate. Usually, there is erythema and discomfort at the end of the digit. Resorptive osteolysis of finger or toes may also occur in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.[31]

Subacute or chronic paronychia

Psoriatic paronychia usually develops when the periungual skin is affected by psoriasis, but it is also commonly seen in psoriatic arthritis with nail involvement. The chronic inflammation causes thickening of the free edge of the proximal nail fold with consecutive loss of cuticle and the attachment of the nail fold's ventral surface to the underlying nail plate. This allows foreign material such as dirt, microorganisms, or allergenic substances to enter the space beneath the nail fold where they may aggravate inflammation.[32]

Psoriatic onychopachydermoperiostitis

It is a very recently described uncommon variant of psoriatic arthritis.[33] It is characterized by psoriatic onychodystrophy or onycholysis, soft tissue thickening over distal phalanx, and periosteal reaction with absence of distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) involvement. Psoriatic onychopachydermoperiostitis may involve nails of any finger or toe. However, nails of great toes are involved in most reported cases in literature.[34]

Assessment of Nail Psoriasis: Nail Psoriasis Severity Index

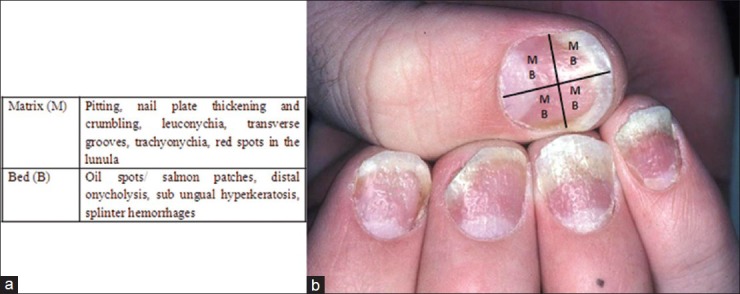

Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), initially described Rich and Scher,[35] is an objective and a reproducible tool for estimating the severity of psoriatic nail involvement and is mainly used to measure the efficacy of various therapeutic interventions. Eight features of nail psoriasis have been identified for the NAPSI score: Four involve the nail matrix (pitting, leukonychia, red spots in the lunula, nail plate crumbling) and four of the nail bed (onycholysis, splinter hemorrhages, subungual hyperkeratosis, oil spot/salmon patch). However, van der Velden et al.,[19] in a case-controlled study on nail psoriasis found that leukonychia was present in 65% of the control population and therefore questioned the position of leukonychia in NAPSI score.

For estimation of NAPSI, each nail is divided into four quadrants Each quadrant is evaluated for the presence of any manifestation of psoriasis in the nail matrix (M) or nail bed (B) [Figure 8]. The lesion(s) of nail matrix and nail bed are given a score of 1 in each quadrant, so that there is nail matrix score of 0-4 and nail bed score of 0-4 per nail with a total maximum score of 8 and a minimum score of 0 per nail. For example, in Figure 8, the presence of onycholysis and salmon patches in three of the four quadrants of the thumbnail gives a nail bed score of 1 to three of the quadrants. Pitting gives all the four quadrants a nail matrix score of 1; therefore, the total NAPSI score of the thumbnail is 7. This method has been used differently by different research workers, some using NAPSI score of all fingers and/or toes (80 and 160, respectively) or often, specific nails are targeted to assess the effects of therapy.[8]

Figure 8.

Estimation of NAPSI-the affected nail is divided into four quadrants and the presence of lesions of the nail matrix (M) and nail bed (B) are given a score of 1 in each quadrant

Diagnosis of Nail Psoriasis

Diagnosis of nail psoriasis can be made easily in a patient with concomitant skin psoriasis. Close examination with a hand lens can help in appreciating the above mentioned changes in a greater detail. However, in cases of isolated nail psoriasis (5-10% of cases) and in patients presenting with a diagnostic dilemma to a dermatologist the following techniques can be used.

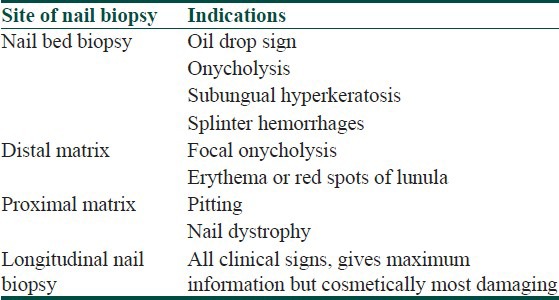

Nail biopsy

The trick behind getting a diagnostic biopsy lies in choosing the area to be biopsied, that is, the area that will show diagnostic histopathological changes. Table 2 summarizes the sites to be biopsied as per the clinical manifestations.[36]

Table 2.

Sites for nail biopsy

Technique of nail biopsy

The selected digit is anesthetized with a proximal ring block or a distal wing block and then exsanguinated. A tourniquet is then applied at the base of the digit to achieve complete hemostasis and a relatively avascular field, keeping in mind that the tourniquet should not be kept in place for more than 15 min at a stretch. Nail biopsy can then be taken as an excision biopsy or punch biopsy or longitudinal nail biopsy. A punch or an excision biopsy can be applied to any individual anatomical part of the nail unit, like the nail bed, nail plate, nail fold, or matrix, whereas with a longitudinal nail biopsy, a part of all the parts of the nail unit are biopsied. The defect is then sutured using 3-0 – 6-0 silk. After completion of biopsy, adequate hemostasis is secured and pressure dressing is done. The sutures are then removed after 10 days.[36,37]

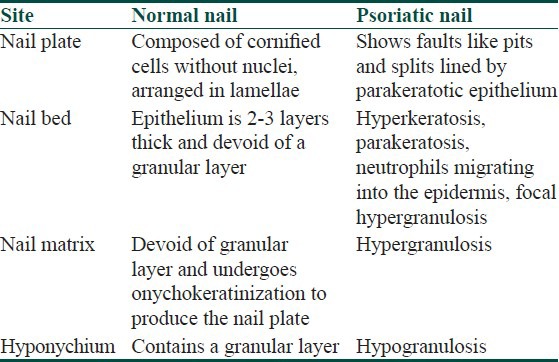

Histopathology of nail psoriasis varies according to the clinical focus of the disease. Table 3 contrasts the important histopathological differences between a normal nail and a nail affected by psoriasis.[38,39,40] Hanno et al.,[40] proposed diagnostic criteria of nail psoriasis in the form of presence of neutrophils in the nail bed epithelium (major criterion), hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis, serum exudates, focal hypergranulosis, and nail bed epithelium hyperplasia (minor criteria).

Table 3.

Histopathology of nail psoriasis in comparison to normal nail

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy is a noninvasive, quickly applied, and inexpensive test that may aid in diagnosis of nail psoriasis in inconclusive cases especially in a resource poor set up.[41] It is performed with manual devices which do not require computer assistance and generally employs ×10 magnifications.[42] Dermoscopic description of common signs of nail psoriasis is as follows:[41]

Pits-appear as irregular depressions surrounded by a whitish halo

Salmon patches-appear as marks that are irregular both in size and shape with coloring that varies from red to orange

Onycholysis-appears as an area that is either homogenously white or composed of multiple longitudinal striations, generally surrounded by a reddish orange stain

Splinter hemorrhages-appear as longitudinal brown, purple or black marks

Blood vessels-appear as dilated tortuous vessels seen in the distal nail bed.

Videodermoscopy

Videodermoscopy represents an evolution of dermoscopy and is performed with a video-camera equipped with lenses providing magnification ranging from ×10 to ×1000.[42,43] The images obtained are visualized on a monitor and can be stored on a personal computer.[42] Iorizzo et al.,[44] showed that using videodermoscopy the capillaries of the hyponychium of nails affected by psoriasis were visible, dilated, tortuous, elongated, and irregularly distributed. The capillary density was different in each patient and positively correlated with disease severity.

Capillaroscopy

Periungual capillaroscopy shows that capillary density in the periungual area is decreased in patients with psoriasis which is even lesser in patients with nail psoriasis.[45] Avascular areas in the periungual area are more common in patients with nail psoriasis.[45] Also, the presence of coiled capillary loops in the periunguium can be appreciated.

New diagnostic techniques

Ultrasound

Ultrasonography of the nails requires a high-resolution ultrasound (US) machine and a high-frequency US probe.[46] In nails affected by psoriatic onychopathy, the nail plates may show hyperechoic parts or loss of definition, which can involve only the ventral plate or both plates.[47] In later stages, a wavy thickened appearance of both plates may be visible. The nail bed is thickened and these changes are associated with an increase in blood flow that can be observed with power Doppler technique.[47]

Optical coherence tomography

It works on the principle that infrared light reflected from nail is measured and the intensity is imaged as a function of position.[48] The optical coherence tomography (OCT) probe is applied directly to the nail and scanning lasts for a few seconds. This technique provides images of tissue pathology in situ with a higher axial resolution as compared to US.[48] Aydin et al.,[49] recently reported high-resolution OCT changes in nail psoriasis which consisted of a grossly dyshomogeneous and eroded ventral nail plate which was irregularly fused with the underlying epidermis.

OCT can also measure the thickness of the nail plate with a greater accuracy in comparison to US. This suggests that OCT has the potential to provide quantitative data regarding psoriatic nails and may become a more accurate and objective surrogate outcome measure for interventional trails in future.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

It is a new noninvasive diagnostic tool which is becoming increasingly popular. It can visualize cell structures of the skin up to a depth of 300 μm in vivo. It works on the principle of increasing the optical resolution and contrast of a micrograph by using a spatial pinhole to eliminate out of focus light.[46] Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) enables reconstruction of three-dimensional images of nails and is a promising tool in the diagnosis of nail psoriasis.[50] Compared with the OCT images, which best allow the measurement of thickness of the entire nail plate and of the different layers of the nail unit, CLSM gives better information on the microscopic structures of the nail plate.[51] Even the borders of the corneocytes can be evaluated and their integrity can also be investigated. For instance, in a patient presenting with leukonychia, Sattler et al.,[51] showed that by using CLSM disturbance of the integrity of the corneocytes of nail plate can be demonstrated.

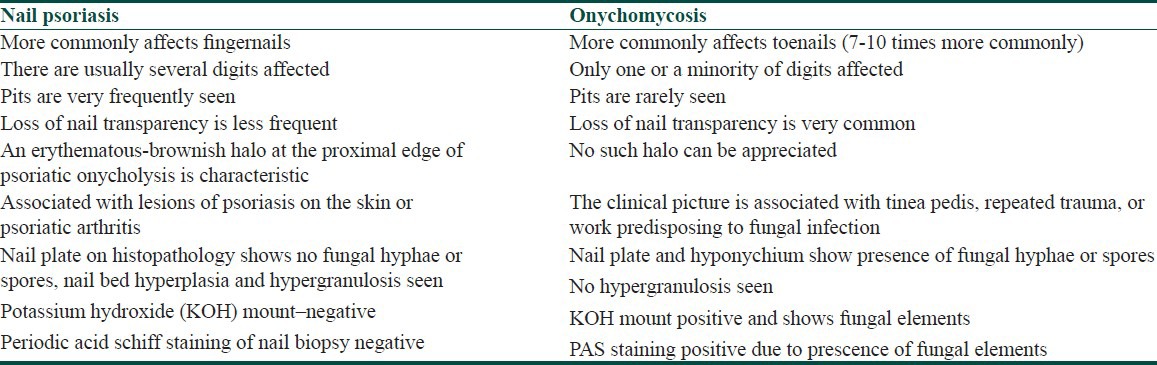

Differential diagnosis

The most frequently encountered differential diagnosis of nail psoriasis is onychomycosis, which usually presents with a diagnostic dilemma.[19,32] Important points of difference between the two have been contrasted in Table 4.[21,36,52] However, onychomycosis can coexist with nail psoriasis as was established by Natrajan et al.,[53] who in a study on 48 patients with nail psoriasis showed that fungal infection coexisted in 47.91% of patients, consisting only of nondermatophytic moulds and yeasts. Lichen planus of nails can be differentiated by absence of pitting and presence of longitudinal grooves, longitudinal fissures, and the presence of dorsal pterygium. Nail pitting in cases of alopecia areata is usually fine and stippled and the diagnosis can be made from clinical observation of hair. Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) also, sometimes presents with thickened and discolored nails but the presence of follicular papules on the dorsum of the fingers and palmoplantar keratoderma favors the diagnosis of PRP. In Darier's disease, characteristic nail changes include red or white longitudinal bands of varying width, often ending in a pathognomonic notch at the free margin of the nail. The nails are often brittle and pits are present on palms and soles. Norwegian scabies is also characterized by the presence of large psoriasis like scales under the nail plate where the mites usually reside and later colonize the skin, first around the nail plate and then proximally. The patient in these cases is usually old, infirm, or mentally ill or has HIV infection.

Table 4.

Differences between nail psoriasis and onychomycosis

Treatment of Nail Psoriasis

Nail disease is usually overlooked in the management of psoriasis, with skin involvement being the primary concern. Also, treatment of nail psoriasis is a big challenge for a dermatologist because of the following reasons:

Poor drug delivery: the matrix pathology is hidden by the proximal nail fold and the nail bed changes are protected against treatment by the overlying nail plate and nail bed hyperkeratosis, making delivery of drug to the affected site very difficult.

Slow rate of nail growth attributes to a longer duration of treatment required, leading to a questionable long-term compliance by the patient.

Keeping in mind the potential significant toxicities of the various systemic agents advocated for psoriasis, the use of systemic agents is not generally advisable for treating nail psoriasis alone and is recommended for cases with coexistent severe skin or joint disease or in patients with extensive or recalcitrant nail psoriasis.

Also, despite the recognized burden of nail psoriasis,[4] there is a dearth of good-quality evidence for the management of nail psoriasis. A recent systematic review on treatment options for nail psoriasis, published in January 2013, highlighted the fact that the quality of trials done so far is generally poor and the data available is insufficient to advocate a consistent treatment approach or algorithm for the management of psoriasis.[54]

Various treatment options, however, have been advocated for the treatment of nail psoriasis depending upon the site of nail involvement and the presence of nail psoriasis in few or many nails.[1,55,56] For example, nail matrix involvement manifesting as pitting, trachyonychia, dystrophy, and leukonychia should be treated with different modalities as compared to nail bed involvement manifested by onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, oil spot/salmon patch and splinter hemorrhages. A therpeutic algorithm has been suggested by Jiaravuthisan et al.:[1]

Psoriatic lesions in a few nails

Topical therapy

-

Nail matrix involvement

- Intralesional steroids

- Tazarotene

- Topical potent steroids

-

Nail bed involvement

- Calcipotriol and steroids

- Tazarotene

- Cyclosporine

Psoriatic lesions in many nails

Systemic therapy

Infliximab

Retinoids

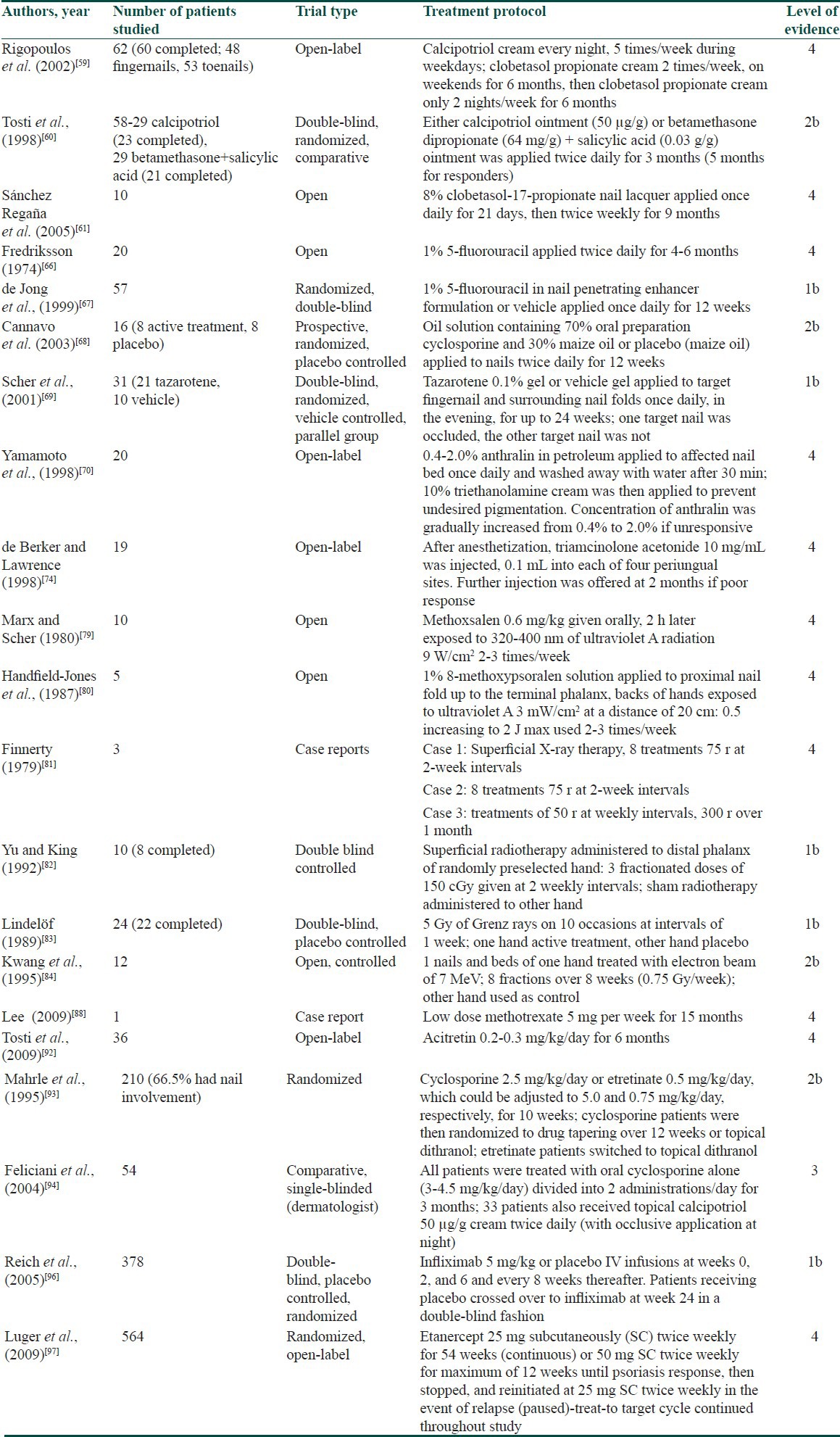

Table 5 gives an account of the work done on various treatment options for nail psoriasis, which will also be discussed below.

Table 5.

Treatments for nail psoriasis including level-of-evidence assignments as used by group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis

General measures

Before starting treatment for nail psoriasis, it is imperative for any dermatologist to allay fear and concern in the patient regarding his/her disease.[56,57] It is also recommended to highlight the need for long-term treatment, and the importance of good treatment compliance by the patient. The importance of simple approaches, as follows, in nail psoriasis should not be underestimated:

Nails should be kept short to avoid exacerbating onycholysis and to avoid the accumulation of exogenous material under the nail.

Trauma of manual removal of exogenous material should be avoided as it may worsen onycholysis and allow entry of pathogens

Protection of nails from injury is important, by wearing gloves and application of emollient creams on the psoriatic skin of hands and nail folds.

Protection against irritants is prudent, and aggressive manicure of the cuticle, which may provoke paronychia, should be avoided.

Cosmetic camouflage: Prosthetic nails are generally inadvisable. Nail buffing and nail varnish may temporarily conceal pitting.

Topical therapies

If nail changes are mild and not bothersome to the patient or if nail psoriasis is the only manifestation of the disease, topical therapies are often an appropriate first choice.[58] The digits in bracket in the text ahead denote the level of evidence for each modality discussed.

Corticosteroids

The most popular preparations for the treatment of nail psoriasis are potent to very potent glucocorticoids like clobetasol propionate 0.05% (4)[59] and betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% (2b).[60] They have been used once or twice a day for up to 9 months.[56] Recently, 8% clobetasol-17-propionate in a colorless nail lacquer vehicle used once daily for 21 days and then twice weekly for 9 months has shown good results (4).[61] If psoriasis affects the nail matrix, the topical agent is often applied to the nail folds, but if psoriasis is derived from the nail bed, nail needs to be trimmed to the hyponychium before treatment is applied.[1] It is often recommended to apply high potency steroids under the covering of an occlusive dressing, such as a pair of plastic gloves to increase the drug penetration.[25,62] The potential side effects of long-term therapy with high potency topical steroids are skin atrophy when the proximal or lateral nail folds are involved, formation of striae and telangiectasia, tachyphylaxis and potential systemic absorption of steroid.[1] Furthermore, with persistent use of very potent topical steroids over years, a number of studies have documented a possible tapering of the treated digit, which can be caused by atrophy of the underlying phalanx and is commonly known as “disappearing digit”.[63,64,65]

Vitamin D analogues

Calcipotriol (50 μg/g) twice daily application for 3-6 months has been evaluated in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Tosti et al.,[60] found calcipotriol twice daily for 6 months to be as effective as topical steroids in treating subungual hyperkeratosis (2b). Rigopoulos et al.,[59] found that combining calcipotriol with clobetasol propionate, led to a 77% improvement in hyperkeratosis of the fingers and toes within 6 months. Side effects like erythema, periungual irritation, burning at the site of application, and diffuse urticaria have been associated with the use of vitamin D analogues.

5-fluorouracil

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in a formulation of 1% solution has been used as a topical treatment in nail psoriasis. A small study showed improvement in pitting and hyperkeratosis after application of 5-FU twice daily for 6 months, although, it was found to worsen onycholysis (4).[66]

A double blind study, however, found no additional benefit from the addition of 1% 5-FU to a nail penetration enhancer containing urea and propylene glycol, applied for 12 weeks (1b).[67]

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine applied in an oil solution containing 70% oral cyclosporine has demonstrated some efficacy in the treatment of nail psoriasis (2b).[68]

Tazarotene

Tazarotene 0.1% gel or cream applied once daily for 12-24 weeks has been shown to improve pitting, onycholysis, and salmon patches on both fingernails and toenails.[56] Scher et al.,[69] showed that 24 weeks of treatment with tazarotene 0.1% gel twice a day for 24 weeks led to significant improvement in onycholysis and pitting in fingernails and the improvement was faster in occluded nails (1b).

Anthralin

Topical anthralin 0.4-2% ointment applied to the nail bed once daily and washed off after 30 min was shown to be effective in nail bed dystrophies (4).[70] Temporary staining of the nail and local irritation were seen as side effects of this therapy.

Combination treatment

Combination treatment has the potential to give quicker responses because of the synergistic action of its constituents. Combined treatment with 8% clobetasol-17-propionate in lacquer applied at the weekend and tacalcitol ointment under occlusion on weekdays for 6 months showed a good and quick response; with 78% improvement in the modified target NAPSI score at the end of therapy along with reduction in nail pain.[71]

Iontophoresis

Iontophoresis is a technique using small electric current to deliver medications or other chemicals through the skin. and Howard,[72] used dexamethasone iontophoresis for the treatment of nail psoriasis. 100 ml of distilled water with 3 ml of dexamethasone solution was taken in a shallow plastic container in which all the fingernails were dipped. Electrodes were placed on dorsum of hands and a current of 4mA was passed through the solution for 20 minutes. The treatment was repeated weekly for atleast 3 months and 81% patients showed improvement in their nails.

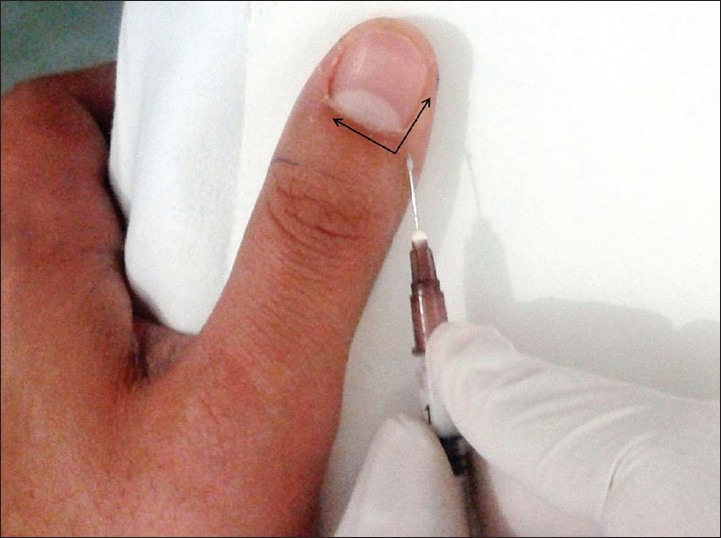

Intralesional treatments

Intalesional corticosteroid injections

This therapy consists of injecting small doses of corticosteroid directly into or near the structure of nail unit that is responsible for the specific nail change [Figure 6]. Triamcinolone acetonide is the most commonly used intralesional steroid in a concentration of 2.5-10 mg/mL. Figure 9 demonstratres the technique of intralesional injections.[73] In a study done by de Berker and Lawrence[74] intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) 0.1 mL was injected at four periungal sites and further injection was given at 2 months if the response was poor. This regimen cleared subungual hyperkeratosis in 19 patients with 46 fingers affected with nail psoriasis (4). Transverse ridging improved in 93%, nail thickening in 83%, and onycholysis improved in 50%. The effect of steroids is not long-lasting and the injections have to be repeated after 2-9 months.[8] Pain is the main side effect of treatment with intralesional corticosteroids. A ring block prior to the injection[74] or mixing the injection with local anesthetic[1] has been advised by some workers.

Figure 9.

Technique of intramatricial corticosteroid injection. Injection is to be given at a point 2.5 mm proximal and lateral to the junction of proximal and lateral nail fold so that the steroid spreads both distally as well as laterally (shown by arrows)

Intralesional methotrexate injections

Intralesional methotrexate (MTX) injections have recently been tried in the treatment of nail psoriasis in a psoriatic patient with pitting and subungual hyperkeratosis of only one nail. MTX 2.5 mg was injected into each side of the proximal nail fold once weekly for 6 weeks.[75] Pain was tolerable. During the 4-month follow-up, the psoriatic nail alterations improved and no clinical or laboratory side effects were noted. No recurrence of the nail lesions was observed in the following 2 years.

Intralesional cyclosporine injections

Although intralesional cyclosporine has shown good effects in the treatment of cutaneous psoriasis,[76,77] there are no reports on the use of intralesional cyclosporine in the treatment of nail psoriasis. However, keeping in mind its efficacy in the treatment of skin psoriasis, it can prove to be a very useful tool in the treatment of nail psoriasis.

Phototherapy and photochemotherapy

Phototherapy in the form of narrow band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) and photochemotherapy in the form of ultraviolet A (UVA) therapy combined with oral or topical photosensitizer (psoralen) known as PUVA (Psoralens + UVA) therapy, have been widely used in management of cutaneous psoriasis. As penetration of NBUVB is rather superficial, targeted NBUVB may not be an appropriate option for palmoplantar lesions or nail psoriasis.[78]

Photochemotherapy, however, appears to be successful in the treatment of psoriasis arising in the nail bed like onycholysis, salmon patches, and subungual but causes little improvement in the nail matrix symptom, that is, pitting (4). Marx and Scher[79] published a prospective study in 1980 in which 10 patients (a total of 26 separate dystrophies), who had generalized psoriasis with nail involvement were treated with oral photochemotherapy. The regimen consisted of methoxsalen, at a dose of 0.6 mg/kg and high-intensity UVA radiation, which was administered 2-3 times a week. Once the patients were 95% clear of psoriasis, the subjects were maintained on a once per week maintenance schedule. Overall, it was found that nail pitting was unaffected by PUVA therapy, whereas proximal nail fold involvement and nail plate crumbling improved the most. Handfield-Jones et al.,[80] explored the use of topical PUVA on psoriatic nail lesions. Nails in two out of five patients cleared completely and the nails of two other patients showed significant improvement. Photo-onycholysis and subungual hemorrhage along with local pigmentation are dreaded complications of photochemotherapy.

Ionizing radiations

Superficial radiotherapy

It is a form of electromagnetic radiation in which the maximum dose of energy is delivered to the surface of skin. The use of superficial radiotherapy (SRT) in nail psoriasis has been infrequent. However, it has been found to achieve clearance of subungual hyperkeratosis, nail cracking, separation, and discoloration in one study (4)[81] and significant reduction in nail thickness in another (1b).[82]

Grenz rays

It is an ultrasoft radiation produced at low enough kilovoltages that it does not penetrate beneath the skin. In 1989, Lindelof[83] experimented with the use of Grenz rays in a double blinded study involving 22 patients who had nail psoriasis on both hands (1b). Only one hand was treated, whereas the other received sham treatment. The protocol consisted of 5 Gy of Grenz rays given in 10 weekly courses at the end of which some subjects showed improvement (one-complete and seven mild), but not if the nails were hyperkeratotic, which may be due to inability of this type of radiation to penetrate thick nail.

Electron beam therapy

Kwang et al.,[84] conducted a prospective study to examine the efficacy of electron beams in treating nail psoriasis (2b). Some degree of improvement was seen in 9 of 12 patients after an 8-week course of weekly treatment with 0.75 Gy of electron beam therapy. However, the improvement was lost in all but one patient after 12 months follow-up.

Adverse effects of ionizing radiations include pigmentation of the treated areas, early local inflammation, and late fibrosis and the potential for development of malignancy years after radiation therapy.[1]

Lasers

As angiogenesis was found to be one of the driving factors in psoriasis pathogenesis, most studies on lasers for nail psoriasis were performed with the pulsed dye laser (PDL), which specifically targets blood vessels. Three recent studies used PDL for nail psoriasis-first in comparison with photodynamic treatment (PDT),[85] the second evaluated the effect of PDL on nail psoriasis[86] and the third study used two different pulse widths and compared their efficacy.[87] All studies used a 595-nm PDL with a spot size of 7 mm. The pulse duration in the first study was 6 ms, in the second one 1.5, and the third one compared the efficacy of 6 ms with 0.45 ms pulse width, fluences were 9, 8-10, and 9 and 6 J/cm², respectively. Both the PDT and the PDL group showed a decrease in the NAPSI score with no difference between the two groups.[85] The second study showed an improvement mainly of the nail bed NAPSI score with use of PDL. In the third study, no difference could be demonstrated in the treatment outcome between the long 6 ms pulse with 9 J/cm² group and the short 0.45 ms pulse duration with 6 J/cm² group; however, pain was significantly more intense in the longer pulse group.[87]

Systemic therapies

A variety of systemic agents have been tried in the treatment of nail psoriasis. MTX, retinoids, and cyclosporine have been the most extensively explored. However, they are usually used when there is coexisting severe skin or joint disease and not for psoriasis affecting nails alone. Other agents like sulfasalazine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, calcipotriol are yet to be fully assessed.

Methotrexate

In one case report MTX low dose therapy, 5 mg per week in two divided doses given 12 h apart, for severe 20-nail psoriasis led to complete clearance of severe nail psoriasis of fingernails and toenails in 9 months and 13 months, respectively.[88] In another study, MTX produced NAPSI score improvements of 7%, 31%, and 35%, respectively, after 12, 24, and 48 weeks (4).[89] A single-blinded, randomized study involving 34 patients also showed that MTX achieved a 43% decrease in NAPSI scores, compared with a 37% reduction for cyclosporine (1b).[90] In this study, it was also seen that the nail matrix lesions did better with MTX, whereas nail bed psoriasis fared better with cyclosporine.

Retinoids

The effects of retinoids, acitretin and etretinate, on nail psoriasis strongly depend on the dosages used because these drugs may produce worsening of nail psoriasis by inducing paronychia and nail fragility when used at dosages recommended for skin psoriasis.[91] However, using them at a lower dosage than that recommended for cutaneous psoriasis can prove to be fruitful without causing any side effects. Tosti et al.,[92] gave low-dose acitretin 0.2-0.3 mg/kg/day for 6 months, at the end of which NAPSI reduced by mean of 41%.

Cyclosporine

Nail lesions usually respond favorably to cyclosporine. In a median dose of 2.5 mg/kg bodyweight daily, cyclosporine effectively reduces skin and nail psoriasis. In a comparative trial, cyclosporine (2.5 mg/kg/day) and etretinate (0.5 mg/kg/day) were given to 210 patients, two thirds of whom had nail involvement. At the end of 10 weeks, both groups showed slight improvement of their nails which continued in the group that continued with tapered cyclosporine (2b).[93] In a retrospective evaluation, cyclosporine was found to improve the NAPSI score after 12, 24, and 48 weeks by 40%, 72%, and 89%, respectively.[89] In a single blind study of 54 patients, oral cyclosporine (3-4.5 mg/kg/day) with and without topical calcipotriol (50 μg/g) twice daily was used for 3 months. Subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and pitting improved in 79% of patients in the combination group compared with only 47.6% of those given oral cyclosporine alone (3).[94]

The advent of new treatment options: Biologic therapy

Overall, the conventional treatment for nail psoriasis appears to be unsatisfactory, tedious, and inconvenient. Most of the treatment options achieve only a moderate efficacy, complete clearance is infrequent and efficacy of conventional therapy decreases with time. This clinical challenge faced by many dermatologists has recently been addressed with the introduction of the biological response modifiers.[95] These agents have demonstrated efficacy in both the skin and nail components of psoriasis.

Infliximab

The best studied biologic agent is infliximab. The best evidence comes from the EXPRESS trial [European Infliximab for Psoriasis (Remicade) Efficacy and Safety Study] which was a phase-3 double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial (1b).[96] A total of 378 patients with moderate to severe plaque type psoriasis with nail involvement were randomly assigned in a ratio of 4:1 to receive infliximab 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6, and every 8 weeks till week 46. Placebo was given at 0, 2, 6, 14, 22 and crossing over to infliximab occurred at week 24. This study showed that infliximab resulted in significant improvement in nail psoriasis as early as week 10 and at week 50 full clearance was evident in 45% of patients.[96]

Etanercept

Etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, has shown efficacy in nail psoriasis in an open-label, randomized trial (CRYSTEL) including 564 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with nail involvement receiving etanercept for 54 weeks (4).[97] Mean NAPSI scores decreased by 28.9% at 12 weeks and continued to decrease by 51% at 54 weeks. Furthermore, at the end of treatment, 30% of patients with nail psoriasis at baseline reported complete clearance.[97]

Adalimumab

In a study done by van den Bosch et al.,[98] 40 mg of adalimumab every other week reduced the mean NAPSI score by 65% after 20 weeks (4).

Ustekinumab

There is a growing interest in the use of ustekinumab in the treatment of nail psoriasis.[99,100] Recently, Patsatsi et al.,[99] conducted an open-label study to evaluate the role of ustekinumab in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Twenty-seven patients were taken and scheduled to receive subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab at a dose of 45 mg at baseline and week 4 and every 12 weeks. NAPSI median score significantly decreased from 73.0 at baseline to 37.0 at week 16, to 9.0 at week 28, and to 0.0 at week 40. The findings of this study suggest that ustekinumab is very effective in nail psoriasis.

Beyond the Skin and the Nail

Nail psoriasis is considered a precursor of a severe inflammatory joint disorder. There is a positive association between nail psoriasis and the severity of joint involvement.[35] Nail psoriasis is also correlated with enthesitis, polyarticular disease, and unremitting progressive arthritis.[101,102] High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging studies have found that psoriatic arthritis related DIP joint inflammatory reaction is very extensive which frequently involves the nail matrix and often extends to involve the nail bed.[102] This is mainly due to the attachment of fibers of ligaments and tendons of DIP joint close to the matrix.[102] The presence of joint or nail symptoms may indicate a severe form of psoriasis, and this will affect how the disease is managed. It is important, therefore, for dermatologists to be aware of the early symptoms of psoriatic arthritis, particularly in patients with nail psoriasis, in order to avoid progressive joint damage.[11,12,13,14]

Conclusion

Nail psoriasis is frequent in psoriatic subjects, with about 10-78% of psoriasis patients having concomitant nail changes at any time and a lifetime prevalence of up to 90%. The most frequent signs of nail matrix disease are pitting, leukonychia, crumbling, and red spots in the lunula, whereas salmon patches or oil spots, subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages represent changes of nail bed psoriasis. The treatment of nail psoriasis is prolonged with both conventional and biologic therapies and the systemic side effects of the various therapies limit their use. Hence, it requires patience both on the part of the treating dermatologist and the patient. The presence of nail disease in a patient with psoriasis may indicate a severe form of the disease and must be taken into account when selecting a treatment option, with an aim to reduce pain, functional impairment as well as emotional distress. By managing the nail disease effectively, a dermatologist can effectively stop the underlying inflammatory process and limit the progression of the disease.

What is new?

Nail psoriasis has a serious impact on the quality of life, interfering with manual work and also being cosmetically disfiguring.

Nail biopsy, dermoscopy, US and recent advances like OCT and CLSM can help in solving the diagnostic dilemma.

Treatment of nail psoriasis can be highly rewarding with early diagnosis and use of intralesional injections of steroid or MTX, and low dose oral MTX, acitretin, and cyclosporine.

Promising results in the management of nail psoriasis have been seen by the use of biologic drugs, which are currently recommended only for severe concomitant nail and skin or joint psoriasis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Jiaravuthisan MM, Sasseville D, Vender RB, Murphy F, Muhn CY. Psoriasis of the nail: Anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature on therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gudjonsson JE, Karason A, Runardsdottir EH, Antonsdottir AA, Hauksson VB, Jonsson HH, et al. Distinct clinical differences between HLA-Cw 0602 positive and negative psoriasis patients: An analysis of 1019 HLA-C- and HLA-B-typed patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:740–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvert HT, Smith MA, Wells RS. Psoriasis and the nails. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:415–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1963.tb13535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jong EM, Seegers BA, Gulinck MK, Boezeman JB, van de Kerkhof PC. Psoriasis of the nails associated with disability in a large number of patients: Results of a recent interview with 1728 patients. Dermatology. 1996;193:300–3. doi: 10.1159/000246274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomon J, Szepietowski JC, Proniewicz A. Psoriatic nails: A prospective clinical study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:317–21. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Berker D. Management of psoriatic nail disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosal A, Gangopadhyay DN, Chanda M, Das NK. Study of nail changes in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 1):15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail Psoriasis: A questionnaire-based survey. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:314–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung YY, Tam LS, Kun EW, Li EK. Psoriatic arthritis as a distinct disease entity. J Postgrad Med. 2007;53:63–71. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.30334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawry M. Biological therapy and nail psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:60–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, Gee BC, Weatherall R, Wordsworth BP. Extended report: Nail disease in psoriatic arthritis: Clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:790–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGonagle D, Tan AL, Benjamin M. The biomechanical link between skin and joint disease in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: What every dermatologist needs to know. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landells I, MacCallum C, Khraishi M. The role of the dermatologist in identification and treatment of the early stages of psoriatic arthritis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2008;13:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elder JT. Genome-wide association scan yields new insights into the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Genes Immun. 2009;10:201–9. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho PY, Barton A, Worthington J, Thomson W, Silman AJ, Bruce IN. HLA-Cw6 and HLA-DRB1*07 together are associated with less severe joint disease in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:807–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.064972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigopoulos D, Korfitis C, Gregoriou S, Katsambas AD. Infliximab in dermatological treatment: Beyond psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:123–33. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortonne JP, Baran R, Corvest M, Schmitt C, Voisard JJ, Taieb C. Development and validation of nail psoriasis quality of life scale (NPQ10) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Velden HM, Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Fingernail psoriasis reconsidered: A case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Berker DA, Baran R. Disorders of Nails. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford: Willey Blackwell; 2010. pp. 65.23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaias N. Psoriasis of the nail unit. Dermatol Clin. 1984;2:493–505. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaias N, editor. 2nd ed. London: Appleton and Lange; 1990. Nail in Health and Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eastmond CJ, Wright V. The nail dystrophy of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38:226–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.38.3.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawcett RS, Linford S, Stulberg DL. Nail abnormalities: Clues to systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1417–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Berker DA, Baran R, Dawber RPR. The nail in dermatological diseases. Diseases of the nail and their management. In: Baran R, Dawber RP, editors. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1991. pp. 172–222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kouskoukis CE, Scher RK, Ackerman AB. The ‘oil drop’ sign of psoriatic nails. A clinical finding specific for psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:259–62. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGonagle D, Palmou Fontana N, Tan AL, Benjamin M. Nailing down the genetic and immunological basis for psoriatic disease. Dermatology. 2010;221(Suppl 1):15–22. doi: 10.1159/000316171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleckman P. Structure and function of the nail unit. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR, editors. Nails: Diagnosis, therapy, surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burden AD, Kemmett D. The spectrum of nail involvement in palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1079–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baran R. Hallopeau‧s acrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:815. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1979.04010070001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller JL, Soltani K, Toutellotte CD. Psoriatic acro-osteolysis without arthritis. A case study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53:371–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haneke E, Nail psoriasis. Soung J, editor. Psoriasis. In Tech. 2012. [Last accessed on 2013 May 17]. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/psoriasis/nail-psoriasis .

- 33.Vasudevan B, Verma R, Pragasam V, Dabbas D. Unilateral psoriatic onychopachydermoperiostitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:499–501. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.98088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahoney JM, Scott R. Psoriatic onychopachydermoperiostitis (POPP): A perplexing case study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99:140–3. doi: 10.7547/0980140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rich P, Scher RK. Nail psoriasis severity index: A useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:206–12. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover C, Chaturvedi UK, Reddy BS. Role of nail biopsy as a diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:290–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.95443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grover C, Reddy BS, Uma Chaturvedi K. Diagnosis of nail psoriasis: Importance of biopsy and histopathology. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1153–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jerasutus S. Histopathology. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR, editors. Nails: Diagnosis, therapy, surgery. 3rd ed. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia; 2005. pp. 37–70. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaias N. Psoriasis of the nail. A clinical-pathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:567–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanno R, Mathes BM, Krull EA. Longitudinal nail biopsy in evaluation of acquired nail dystrophies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farias DC, Tosti A, Chiacchio ND, Hirata SH. Dermoscopy in nail psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:101–3. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, Schwartz RA. Dermatoscopy: Alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Possible applications of videodermatoscopy beyond pigmented lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:430–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iorizzo M, Dahdah M, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy of the hyponychium in nail bed psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:714–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribeiro CF, Siqueira EB, Holler AP, Fabrício L, Skare TL. Periungual capillaroscopy in psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:550–3. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dogra S, Yadav S. What's new in nail disorders? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:631–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.86469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutierrez M, Wortsman X, Filippucci E, De Angelis R, Filosa G, Grassi W. High-frequency sonography in the evaluation of psoriasis: Nail and skin involvement. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1569–74. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.11.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierce MC, Strasswimmer J, Park BH, Cense B, de Boer JF. Advances in optical coherence tomography imaging for dermatology. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:458–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aydin SZ, Ash Z, Del Galdo F, Marzo-Ortega H, Wakefield RJ, Emery P, et al. Optical coherence tomography: A new tool to assess nail disease in psoriasis? Dermatology. 2011;222:311–3. doi: 10.1159/000329434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hongcharu W, Dwyer P, Gonzalez S, Anderson RR. Confirmation of onychomycosis by in vivo confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:214–6. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sattler E, Kaestle R, Rothmund G, Welzel J. Confocal laser scanning microscopy, optical coherence tomography and transonychial water loss for in vivo investigation of nails. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:740–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hay RJ, Ashbee HR. Mycology. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Willey Blackwell; 2010. pp. 3634–5. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Natarajan V, Nath AK, Thappa DM, Singh R, Verma SK. Coexistence of onychomycosis in psoriatic nails: A descriptive study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:723. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.72468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Vries AC, Bogaards NA, Hooft L, Velema M, Pasch M, Lebwohl M, et al. Interventions for nail psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD007633. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007633.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cassell S, Kavanaugh AF. Therapies for psoriatic nail disease. A systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1452–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Handa S. Newer trends in the management of psoriasis at difficult to treat locations: Scalp, palmoplantar disease and nails. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:634–44. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.72455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edwards F, de Berker D. Nail psoriasis: Clinical presentation and best practice recommendations. Drugs. 2009;69:2351–61. doi: 10.2165/11318180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gregoriou S, Kalogeromitros D, Kosionis N, Gkouvi A, Rigopoulos D. Treatment options for nail psoriasis. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2008;3:339–44. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rigopoulos D, Ioannides D, Prastitis N, Katsambas A. Nail psoriasis: A combined treatment using calcipotriol cream and clobetasol propionate cream. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:140. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Cameli N, Kokely F, Plozzer C, Cannata GE, et al. Calcipotriol ointment in nail psoriasis: A controlled double-blind comparison with betamethasone dipropionate and salicylic acid. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:655–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sánchez Regaña M, Martín Ezquerra G, Umbert Millet P, Llambí Mateos F. Treatment of nail psoriasis with 8% clobetasol nail lacquer: Positive experience in 10 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:573–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Berker DA. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolf R, Tur E, Brenner S. Corticosteroid-induced ‘disappearing digit’. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:755–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Requena L, Zamora E, Martin L. Acroatrophy secondary to long-standing applications of topical steroids. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1013–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deffer TA, Goette DK. Distal phalangeal atrophy secondary to topical steroid therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:571–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fredriksson T. Topically applied fluorouracil in the treatment of psoriatic nails. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:735–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Jong EM, Menke HE, van Praag MC, van De Kerkhof PC. Dystrophic psoriatic fingernails treated with 1% 5-fluorouracil in a nail penetration-enhancing vehicle: A double-blind study. Dermatology. 1999;199:313–8. doi: 10.1159/000018281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cannavò SP, Guarneri F, Vaccaro M, Borgia F, Guarneri B. Treatment of psoriatic nails with topical cyclosporin: A prospective, randomized placebo.controlled study. Dermatology. 2003;206:153–6. doi: 10.1159/000068469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scher RK, Stiller M, Zhu YI. Tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of fingernail psoriasis: A double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2001;68:355–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamamoto T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Topical anthralin therapy for refractory nail psoriasis. J Dermatol. 1998;25:231–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sánchez Regaňa M, Márquez Balbás G, Umbert Millet P. Nail psoriasis: A combined treatment with 8% clobetasol nail lacquer and tacalcitol ointment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:963–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le QV, Howard A. Dexamethasone iontophoresis for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:115–9. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Savant SS, Shenoy S. Intramatrix steroid injection. Indian J Dermatol Surg. 2000;2:88–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Berker DA, Lawrence CM. A simplified protocol of steroid injection for psoriatic nail dystrophy. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:90–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarıcaoglu H, Oz A, Turan H. Nail psoriasis successfully treated with intralesional methotrexate: Case report. Dermatology. 2011;222:5–7. doi: 10.1159/000323004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burns MK, Ellis CN, Eisen D, Duell E, Griffiths CE, Annesley TM, et al. Intralesional cyclosporine for psoriasis. Relationship of dose, tissue levels, and efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:786–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ho VC, Griffiths CE, Ellis CN, Gupta AK, McCuaig CC, Nickoloff BJ, et al. Intralesional cyclosporine in the treatment of psoriasis. A clinical, immunologic, and pharmacokinetic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:94–100. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70015-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dogra S, De D. Narrowband ultraviolet B in the treatment of psoriasis: The journey so far! Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:652–61. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.72461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marx JL, Scher RK. Response of psoriatic nails to oral photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1023–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Handfield-Jones SE, Boyle J, Harman RR. Local PUVA treatment for nail psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:280–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Finnerty EF. Successful treatment of psoriasis of the nails. Cutis. 1979;23:43–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu RC, King CM. A double-blind study of superficial radiotherapy in psoriatic nail dystrophy. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:134–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lindelof B. Psoriasis of the nails treated with Grenz rays: A double-blind bilateral trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:80–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555698082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kwang TY, Nee TS, Seng KT. A therapeutic study of nail psoriasis using electron beams. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:90. doi: 10.2340/000155557590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fernández-Guarino M, Harto A, Sánchez-Ronco M, García-Morales I, Jaén P. Pulsed dye laser vs photodynamic therapy in the treatment of refractory nail psoriasis: A comparative pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:891–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oram Y, Karincaoğlu Y, Koyuncu E, Kaharaman F. Pulsed dye laser in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:377–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Treewittayapoom C, Singvahanont P, Chanprapaph K, Haneke E. The effect of different pulse duration in the treatment of nail psoriasis with 595-nm pulsed dye laser: A randomized, double-blind, intrapatient left-to-right study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:807–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee JY. Severe 20-nail psoriasis successfully treated by low dose methotrexate. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sánchez-Regaña M, Sola-Ortigosa J, Alsina-Gibert M, Vidal-Fernández M, Umbert-Millet P. Nail psoriasis: A retrospective study on the effectiveness of systemic treatments (classical and biological therapy) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:579–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gümüsel M, Özdemir M, Mevlitoglu I, Bodur S. Evaluation of the efficacy of methotrexate and cyclosporine therapies on psoriatic nails: A one-blind, randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1080–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baran R. Etretinate and the nails (study of 130 cases) possible mechanisms of some side-effects. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986;11:148–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1986.tb00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tosti A, Ricotti C, Romanelli P, Cameli N, Piraccini BM. Evaluation of the efficacy of acitretin therapy for nail psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:269–71. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mahrle G, Schulze HJ, Färber L, Weidinger G, Steigleder GK. Low-dose short-term cyclosporin versus etretinate in psoriasis: Improvement of skin, nail and joint involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:78–88. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feliciani C, Zampetti A, Forleo P, Cerritelli L, Amerio P, Proietto G, et al. Nail psoriasis: Combined therapy with systemic cyclosporin and topical calcipotriol. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:122–5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Langley RG, Daudén E. Treatment and management of psoriasis with nail involvement: A focus on biologic therapy. Dermatology. 2010;221:29–42. doi: 10.1159/000316179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, Ortonne JP, Evans R, Guzzo C, et al. EXPRESS study investigators. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1367–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luger TA, Barker J, Lambert J, Yang S, Robertson D, Foehl J, et al. Sustained improvement in joint pain and nail symptoms with etanercept therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:896–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van den Bosch F, Reece R, Behrens F, Wendling D, Mikkelsen K, Frank M, et al. Clinically important nail psoriasis improvements are achieved with adalimumab (Humira): Results from a large open-label prospective study (STEREO) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(suppl 2):421. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patsatsi A, Kyriakou A, Sotiriadis D. Ustekinumab in nail psoriasis: An open-label, uncontrolled, nonrandomized study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:96–100. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2011.607796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vitiello M, Tosti A, Abuchar A, Zaiac M, Kerdel FA. Ustekinumab for the treatment of nail psoriasis in heavily treated psoriatic patients. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:358–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Scarpa R, Soscia E, Peluso R, Attento M, Manguso F, Del Puente A, et al. Nail and distal interphalangeal joint in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1315–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tan AL, Benjamin M, Toumi H, Grainger AJ, Tanner SF, Emery P, et al. The relationship between the extensor tendon enthesis and the nail in distal interphalangeal joint disease in psoriatic arthritis: A high-resolution MRI and histological study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:253–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]