Abstract

Increasing interdependence in an intimate relationship requires engaging in behaviors that risk rejection, such as expressing affection and asking for support. Who takes such risks and who avoids them? Although several theoretical perspectives suggest that self-esteem plays a crucial role in shaping such behaviors, they can be used to make competing predictions regarding the direction of this effect. Six studies reconcile these contrasting predictions by demonstrating that the effects of self-esteem on behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence depend on relational self-construal— i.e., the extent to which people define themselves by their close relationships. In Studies 1 and 2, participants were given the opportunity to disclose negative personal information (Study 1) and feelings of intimacy (Study 2) to their dating partners. In Study 3, married couples reported the extent to which they confided in one another. In Study 4, we manipulated self-esteem and relational self-construal and participants reported their willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. In Studies 5 and 6, we manipulated the salience of interpersonal risk and participants reported their willingness to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. In all six studies, self-esteem was positively associated with behaviors that can increase interdependence among people low in relational self-construal but negatively associated with those behaviors among people high in relational self-construal. Accordingly, theoretical descriptions of the role of self-esteem in relationships will be most complete to the extent that they consider the degree to which people define themselves by their close relationships.

Keywords: Self-esteem, Relational self-construal, Interdependence, Intimacy, Romantic Relationships, Behavior

Developing and maintaining intimacy in a close relationship requires engaging in behaviors that increase interdependence. For example, partners in close relationships regularly disclose their intimate thoughts and feelings to one another, express affection for one another, request and provide support to one another, and forgive one another. Indeed, engaging in such behaviors tends to increase the closeness, intimacy, and satisfaction that intimates feel in their relationships (e.g., Collins, & Miller, 1994; Laurenceau, Barett, & Pietromonaco, 1998; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998; Reis & Shaver, 1988; Tsang, McCullough, & Fincham, 2006).

Nevertheless, there is a risky side to these behaviors—they provide the partner with an opportunity to behave in an undesirable or rejecting manner. For example, partners may be critical of self-disclosures, not reciprocate expressions of affection, ignore requests for support, and continue to transgress after being forgiven. These responses can be quite painful, leaving intimates feeling hurt and unsatisfied (e.g., Gable, Reis, Impett, & Asher, 2004; Luchies, Finkel, McNulty, & Kumashiro, 2010; Maisel & Gable, 2009). Consequently, many behaviors that increase interdependence present individuals with a dilemma—the need to choose between risking rejection by engaging in these behaviors to meet their connection goals and risking a less fulfilling relationship by avoiding these behaviors to meet their self-protection goals.

Who takes the risks necessary to increase interdependence in their relationships and who avoids them? Various theoretical perspectives suggest that self-esteem plays a crucial role in shaping such behaviors. However, these perspectives can be used to make competing predictions regarding the direction of this influence. The overarching goal of the current research is to reconcile these contrasting predictions by considering individuals' levels of relational self-construal—i.e., the extent to which they define themselves by their close relationships (Cross, Bacon, & Morris, 2000). To this end, the remainder of this introduction is organized into four sections. The first section reviews theoretical and empirical work that suggests low self-esteem individuals (LSEs) should be more motivated than high self-esteem individuals (HSEs) to avoid behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. The second section, in contrast, reviews theoretical and empirical work that can be used to argue that LSEs should be more motivated than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. The third section attempts to reconcile these two perspectives by describing theoretical and empirical evidence consistent with the possibility that whether self-esteem promotes or undermines behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence depends on individuals' levels of relational self-construal. Finally, the fourth section describes two observational studies of dating couples, one survey study of newlyweds, and three experimental studies of individuals in dating relationships that tested this possibility.

Low Self-Esteem May Discourage Behaviors that Increase Interdependence

Murray and colleagues' (2006) risk-regulation model provides one perspective for considering the role of self-esteem in individuals' decisions to engage in or avoid behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. According to that model, whether people engage in or avoid behaviors that can increase interdependence depends on their appraisal of the likelihood that those behaviors will result in rejection; people protect themselves from the emotional pain of rejection by engaging in behaviors that increase interdependence when rejection appears relatively unlikely and avoiding such behaviors when rejection seems relatively likely. With respect to self-esteem, the risk regulation model specifically posits that LSEs should be more likely than HSEs to expect rejection from their partners and thus be more motivated than HSEs to prioritize their self-protection goals over their connection goals by avoiding behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence (see, Murray et al., 1998, 2006).

Existing research provides support for both ideas (e.g., Baldwin & Sinclair, 1996; Bellavia & Murray, 2003; Cavallo, Fitzsimons, & Holmes, 2009; Gaucher, et al., in press; Leary et al., 1995; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000; Murray et al., 1998, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2009a). Regarding the idea that LSEs are more likely to anticipate rejection, Leary and colleagues (1995, Study 5) demonstrated that LSEs reported feeling more excluded than did HSEs. Likewise, Bellavia and Murray (2003) demonstrated that LSEs were more likely than HSEs to report feeling rejected when they imagined their romantic partner was in bad mood for an unknown reason. Regarding the idea that LSEs should be more likely than HSEs to avoid behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence, Murray and colleagues (2009a) demonstrated that, compared to HSEs, LSEs made fewer efforts to (a) increase their partner's investment into the relationship and (b) satisfy their partner's needs when rejection was salient. Similarly, Gaucher and colleagues (in press) demonstrated that LSEs were less likely than HSEs to disclose their true feelings to a friend, unless they were led to feel secure in that friend's regard, suggesting that LSEs' expectations of rejection motivate them to avoid behaviors that risk rejection to promote interdependence.

Low Self-Esteem May Encourage Behaviors that Increase Interdependence

Yet, another theoretical perspective can be used to argue that LSEs may be more motivated than HSEs to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. According to Leary and colleagues' sociometer theory (e.g., Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995), the function of self-esteem is to help people monitor their relational value. Whereas high self-esteem indicates that one has been accepted and will likely continue to be accepted by others, low self-esteem indicates that one's social standing is in jeopardy. In this way, sociometer theory is similar to the risk-regulation model—both theories suggest LSEs should be more likely to anticipate rejection. Nevertheless, sociometer theory differs from the risk-regulation model in that, whereas the risk-regulation model emphasizes the implications of low self-esteem for individuals' self-protection goals, sociometer theory emphasizes the implications of low self-esteem for individuals' connection goals. Specifically, sociometer theory states that given that individuals have a basic need for connection (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the negative emotions that result from anticipating rejection should “motivate behaviors that help to maintain or enhance one's relational value” (Leary & MacDonald, 2003, p. 402). Given that LSEs are more likely to anticipate rejection than are HSEs, LSEs may thus be more motivated than HSEs to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence.

Several lines of research provide support for this possibility (Heaven, 1986; Janis, 1954; Murray et al., 2009b; Romer, 1981; Santee & Maslach, 1982; Wolfe, Lennox, & Cutler, 1986). For example, several studies (e.g., Heaven, 1986; Janis, 1954; Murray et al., 2009b; Romer, 1981; Wolfe, Lennox, & Cutler, 1986) demonstrate that LSEs are more likely to conform to social norms than are HSEs. Likewise, compared to HSEs, LSEs report being less likely to express disagreement with others (Santee & Maslach, 1982). Finally, LSEs are more likely to respond to exchange norms by engaging in behaviors that increase interdependence, such as making themselves indispensible to their partners and narrowing their partner's social networks (Murray et al., 2009b).

The Moderating Role of Relational Self-construal

Nevertheless, although sociometer theory posits that LSEs should be more motivated than HSEs to engage in behaviors that increase their relational value, research has yet to demonstrate that they will actually engage in behaviors that risk rejection to meet this goal. In fact, the growing body of research in support of the risk-regulation model suggests otherwise. Yet, that work has ignored an important individual difference variable that may be crucial to understanding whether LSEs will prioritize the self-protection goals emphasized by the risk-regulation model or the goal to increase their relational value emphasized by sociometer theory. Specifically, people vary in the extent to which they define themselves by their close relationships, an individual difference known as relational self-construal (Cross et al., 2000). Whereas people who are low in relational self-construal tend to define themselves by their independent qualities, people who are high in relational self-construal tend to define themselves by their close relationships. Not surprisingly, people who are high in relational self-construal tend to place more value on connection and interdependence than do individuals low in relational self-construal (see Gore, Cross, & Morris, 2006). Accordingly, whether LSEs prioritize their self-protection goals or their goal to increase their relational value may depend on their levels of relational self-construal.

An expectancy-value approach (e.g., Atkinson, 1957; Feather, 1982) can help elucidate this potential interaction. According to expectancy-value theory, people decide whether or not to engage in a particular behavior by considering not only the likelihood that the behavior will produce a particular outcome but also the value they place on that outcome. Accordingly, intimates should decide whether or not to engage in behaviors that can increase interdependence by considering not only on their perceptions of the likelihood that such behaviors will lead to acceptance versus rejection, which is partially determined by self-esteem, but also the value they place on interdependence, which should be partially determined by relational self-construal (for a similar discussion, see Anthony, Wood, & Holmes, 2007). Specifically, given that LSEs who are relatively low in relational self-construal should place a relatively lower value on increasing their relational value than LSEs who are higher in relational self-construal, they should prioritize their self-protection goals over their connection goals. Given that those self-protection goals should be stronger than the self-protection goals of equivalent HSEs, as suggested by the risk-regulation model, LSEs who are low in relational self-construal should be less likely than equivalent HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. But given that LSEs who are high in relational self-construal should place a relatively higher value on increasing their relational value than LSEs who are lower in relational self-construal, they may prioritize that goal over their self-protection goals. Given that this relationship-enhancing goal should be stronger than that of equivalent HSEs, as suggested by sociometer theory, LSEs who are high in relational self-construal should be more likely than equivalent HSEs to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence— even if they risk rejection. Put another way, the risk regulation model posits that LSEs have stronger self-protection goals than HSEs, sociometer theory can be used to argue that LSEs also have stronger goals to increase their relational value than HSEs, and relational self-construal should function to determine which of these goals gets prioritized and thus whether LSEs are more or less likely than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence.

Some empirical evidence is consistent with this predicted interaction. For example, people diagnosed with dependent personality disorder tend to have low self-esteem (Overholser, 1992) and tend to consider their close relationships to be very important— i.e., may have high relational self-construal (Pincus & Gurtman, 1995). Consistent with the idea that this combination of low self-esteem and high relational self-construal should predict a greater likelihood of engaging in behaviors that increase intimacy, individuals with dependent personality disorder often engage in behaviors intended to increase intimacy (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), such as complying with requests (e.g., Lowe, Edmundson, & Widiger, 2009), asking for assistance (Shilkret & Masling, 1981), seeking more physical contact with a partner (Hollender, Luborsky, & Harvey, 1970; Sroufe, Fox, & Pancake, 1983), and avoiding physical distance with a partner (Birtchnell, 1988). Similarly, research on Lee's (1973) love styles demonstrates that individuals high in mania, the love style characterized by an intense preoccupation with relationships— i.e., high relational self-construal, also tend to have low self-esteem (Mallandain & Davies, 1994) and, compared to individuals low in mania, report investing more in their relationships (Morrow, Clark, & Brock, 1995) and feeling more emotionally dependent on their partners (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Palarea, Cohen, & Rohling, 2000). Finally, research on ostracism (e.g., Williams & Sommer, 1997) demonstrates that women, who tend to be relatively higher than men in relational self-construal (Cross & Madson, 1997), respond to threats to self-esteem by cooperating, whereas men, who tend to be relatively lower in relational self-construal than women, respond to threats to self-esteem by withdrawing.

Nevertheless, these findings provide only indirect support for the role of relational self-construal in moderating the link between self-esteem and behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Although the people in these studies had traits that tend to be correlated with self-esteem and relational self-construal, none of the studies actually measured self-esteem or relational self-construal, and many of the behaviors examined (e.g., cooperation) do not necessarily risk rejection. Thus, it remains unclear whether relational self-construal actually moderates the effects of self-esteem on the emotionally risky behaviors required to promote interdependence in a close relationship.

Overview of the Current Studies

We conducted six studies to test this possibility. In the first three studies, we assessed participants' self-esteem, relational self-construal, and their willingness to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence in their relationships. We operationalized such behaviors differently across those three studies. In Study 1, we observed whether or not participants in dating relationships chose to disclose their weaknesses to their partners. In Study 2, we observed whether or not participants in dating relationships chose to disclose high levels of affection that we led them to believe they felt for their partners. In Study 3, married couples reported on their naturally-occurring tendencies to confide in one another. In the last three studies, we used experimental methods to rule out alternative explanations and ensure the effects that emerged in the first three studies replicated under conditions of risk. In Study 4, we crossed manipulations of self-esteem and relational self-construal and subsequently assessed participants' resultant desires to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence in their relationships. In Studies 5 and 6, we assessed participants' self-esteem and relational self-construal, manipulated the salience of rejection, and subsequently assessed participants' willingness to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. In all studies, we predicted that the effects of low self-esteem on behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence would depend on relational self-construal, such that low self-esteem would be negatively associated with the likelihood of engaging in these behaviors among individuals low in relational self-construal but positively associated with the likelihood of engaging in these behaviors among individuals high in relational self-construal. In other words, we expected relational self-construal to function to increase the probability that LSEs will engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Given these predictions were driven by the expectation that relational self-construal determines whether LSEs prioritize their relatively high self-protection goals or their relatively high goal to increase their relational value, we did not expect relational self-construal to be associated with such behaviors among HSEs.

Study 1

Study 1 was a laboratory study of dating couples. First, participants were separated and reported on their self-esteem and relational self-construal. Next, in an ostensibly unrelated study, they were (a) told that they would take a personality test and be given feedback about the negative aspects of their personality, (b) told that sharing such information with a partner is beneficial for relationships, and then (c) asked if they wanted to share the feedback with their partner. We chose to have intimates disclose negative aspects of their personality because intimates frequently perceive that such disclosures are risky (Nelson-Jones & Strong, 1976), yet disclosures of vulnerabilities often increase intimacy in close relationships (Rubin, Hill, Peplau, & Dunkel-Schetter, 1980). Based on our theoretical analysis, we predicted that intimates' levels of relational self-construal would moderate the association between their self-esteem and whether or not they disclosed the information to their partners. Specifically, we predicted that low self-esteem would be associated with a lower likelihood of disclosure among those low in relational self-construal but a higher likelihood of disclosure among those high in relational self-construal, and that relational self-construal would increase the probability of disclosure among LSEs, but not HSEs.

Method

Participants

Participants were 61 undergraduate dating couples at a large university in the southeastern United States. Seven individuals were removed from analyses because they identified that their decision to disclose information was the outcome variable.1 The remaining 113 participants had a mean age of 18.64 years (SD = 3.61). All participants had been involved in the romantic relationship for at least three months (M = 15.71, SD = 13.73). One hundred (90%) identified as White or Caucasian, 3 (3%) identified as Black or African American, 2 (2%) identified as Asian American, 2 (2%) identified as Hispanic or Latino(a), 1 (1%) identified as American Indian, and 5 (5%) identified as another race/ethnicity or as two or more races/ethnicities.

Procedure

Primary participants received partial course credit for participating with their romantic partner. Upon arriving at the laboratory, members of the couple were split into two rooms where they gave informed consent and remained for the entire session. All participants were told that they would be participating in two different studies. They were then told that the first study involved filling out several questionnaires and were then left alone to complete the questionnaires (described in the next section). After completing the questionnaires, participants were told that the first study was over, that the goal of that study had been to examine partner similarity and relationship satisfaction, and that this goal was the reason they had been instructed to bring their partner. Participants were informed that the purpose of the second study did not involve romantic relationships and that their partners would be completing a different task. All participants were then told that the goal of the second study was to examine how people respond to negative feedback and thus they would be taking a personality test and would be given feedback about their personality flaws. Offhandedly, the researcher told participants that sharing information about personality flaws tends to benefit close relationships and that the researcher could provide their partner with a summary of their personality flaws if they signed a release form. Whether or not participants signed the form served as the dependent variable. To reduce the chance that participants would sign the form due to various social pressures, (a) participants were told that their partners would not know of participants' option to provide the information if they decided not to reveal it and (b) the experimenter left the room before participants had the opportunity to sign the form. After five minutes, the experimenter reentered the room, recorded whether or not participants signed the release form, informed them that the study was over, debriefed them, probed for suspicion, and then thanked them for participating.

Measures

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. This measure requires individuals to report agreement with 10 items that assess self-esteem (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) using a 4-point Likert response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Appropriate items were reversed and all items were summed. Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha was .89.)

Relational self-construal

Relational self-construal was assessed with the Relational-Interdependent Self-construal Scale (Cross et al., 2000). This measure requires individuals to report agreement with 11 items that assess the extent to which they define themselves by their close relationships (e.g., “My close relationships are an important reflection of who I am,” “In general, my close relationships are an important part of my self-image”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Appropriate items were reversed and all items were summed. Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .84.)

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. As the table reveals, men and women reported self-esteem and relational self-construal scores that were above the midpoint, suggesting that these intimates had relatively high self-esteem and considered their relationships to be an important part of their identity, on average. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Cross & Madson, 1997), a paired-samples t-test revealed that women reported greater relational self-construal than did men, t(52) = -2.56, p = .01. Men and women did not differ in their levels of self-esteem, however, t(52) = .81, p = .42. Thirty-nine (70%) men and 45 (79%) women chose to reveal their personality flaws to their partners. Men and women did not differ regarding their choice to reveal this information, t(111) = 1.17, p = .25.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables in Study 1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | .01 | .23 | -.32* | 32.02 | 4.88 |

| 2. Relational self-construal | .30* | .32* | -.10 | 61.85 | 7.75 |

| 3. Self-disclosure | .20 | .38** | .09 | 79% | |

|

| |||||

| M | 32.79 | 58.00 | 70% | ||

| SD | 4.79 | 8.90 | |||

Note. Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented above the diagonal for women and below the diagonal for men; correlations between men and women appear on the diagonal.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations among the independent variables are also presented in Table 1. Among men, relational self-construal was positively associated with self-esteem and with the decision to disclose their personality flaws. Interestingly, among women, self-esteem was negatively associated with the decision to disclose their personality flaws. Finally, men and women's relational self-construal scores were positively associated with one another.

Did Relational Self-construal Moderate the Association between Self-esteem and the Disclosure of Personality Flaws?

To examine whether relational self-construal moderated the association between self-esteem and the decision to disclose one's personality flaws to the partner, we estimated a two-level model using the HLM 6.08 computer program (Bryk, Raudenbush, & Congdon, 2004). In the first level of the model, the decision to reveal personality flaws (1 = yes, 0 = no) was regressed onto mean-centered self-esteem scores, mean-centered relational self-construal scores, the Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction, and a dummy-code of participant sex. Because the dependent variable was binary, we specified a Bernoulli outcome distribution. The non-independence of couples' data was controlled in the second level of the model that allowed for a randomly varying intercept.

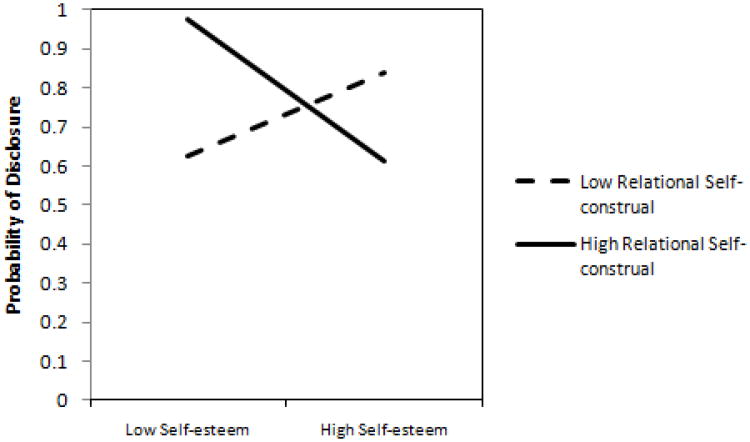

Results are presented in Table 2. As can be seen there, neither self-esteem nor relational self-construal was associated with the disclosure of personality flaws to the partner, on average. Nevertheless, as predicted, the Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction was significantly negatively associated with disclosure. The significant interaction is plotted in Figure 1. Tests of the simple slopes revealed that self-esteem was negatively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on relational self-construal, t(108) = -3.07, p < 0.01, but trended toward being positively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on relational self-construal, t(108) = 1.34, p = 0.18. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal functions to determine whether LSEs are more or less likely than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Relational self-construal was positively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on self-esteem, t(108) = 2.88, p = 0.01, but not associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on self-esteem, t(108) = -1.44, p = 0.15. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal would increase the probability that LSEs, but not HSEs, would engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Notably, subsequent analyses indicated the interaction was not moderated by participant sex, t(107) = -.47, p = 0.64, and remained significant when participant sex was dropped from the model, t(109) = -3.02, p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Effects of Self-esteem, Relational Self-construal, and their Interaction on Willingness to Disclose Personality Flaws in Study 1.

| Self-disclosure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effect size | ||

| B | r | |

| Sex | .29 | .06 |

| Self-esteem (SE) | -.10 | .15 |

| Relational self-construal (RSC) | .06 | .14 |

| SE X RSC | -.02** | .28 |

Note. For the t-test, df = 108.

= p < .01.

Figure 1.

Interactive Effects of Self-Esteem and Relational Self-Construal on Probability of Disclosing Personality Flaws in Study 1.

Discussion

Study 1 provides preliminary evidence that self-esteem interacts with relational self-construal to predict behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Specifically, LSEs who were high in relational self-construal were more likely than equivalent HSEs to disclose their personality flaws to their partners whereas LSEs who were relatively low in relational self-construal trended toward being less likely than equivalent HSEs to disclose their personality flaws.

Nevertheless, it remains possible that self-esteem and relational self-construal differentially interact to predict disclosing positive and negative information (see Critelli & Neumann, 1978). To ensure that the interactive effects of self-esteem and relational self-construal that emerged in Study 1 were not unique to negative self-disclosures, we conducted a second study to examine whether the same interactive pattern emerged to predict self-disclosure of positive information—a desire for intimacy.

Study 2

Study 2 was a laboratory study of dating couples that was similar to Study 1. First, participants were photographed and then completed a bogus implicit priming task that involved those photographs (to set up the dependent variable). Next, they reported on their self-esteem and relational self-construal. Finally, they were given false feedback based on the bogus associative priming task that they desired a high level of intimacy with their partner and were given the option to share their desires for intimacy with their partner. Although disclosing feelings of intimacy is an important way for intimates to increase interdependence (Surra, 1987), it is risky because it can lead to feelings of rejection if such feelings are not reciprocated. Based on our theoretical analysis and the results from Study 1, we predicted that intimates' levels of relational self-construal would moderate the effects of their self-esteem on whether or not they disclosed their high desire for intimacy to their partner. Specifically, we predicted that low self-esteem would be associated with a lower likelihood of disclosing their strong desire for intimacy among those low in relational self-construal but with a higher likelihood of disclosing that desire among those high in relational self-construal, and that relational self-construal would increase the probability of disclosure among LSEs, but not HSEs.

Method

Participants

Participants were 38 undergraduate dating couples at a large university in the southeastern United States who had a mean age of 18.68 years (SD = 2.36). All participants had been involved in a romantic relationship for at least three months (M = 13.18, SD = 11.50). Seventy-one participants (93%) identified as White or Caucasian, 4 (5%) identified as Black or African American, and 1 (1%) identified as Asian American.

Procedure

Primary participants received partial course credit for participating with their romantic partner. Upon arriving at the laboratory, researchers photographed each member of the couple and then separated them into two rooms where they gave informed consent and remained for the entire session. All participants were then informed that they would first engage in a computer task—actually an associative priming procedure (see Olson and Fazio, 2003) designed to set-up the false feedback that they desired a high amount of intimacy with their partner. For this task, participants were asked to indicate as quickly as possible whether 96 words (e.g., awesome, terrible), presented one at a time, were positive or negative using one of two keys on the computer keyboard. Before each word appeared, participants were briefly exposed (300 ms) to pictures of themselves, their partner, and 4 random opposite-sex others. Pictures were presented one at a time and in random order. Following the computer task, participants were instructed to complete various questionnaires, including the same self-esteem and relational self-construal questionnaires used in Study 1. After completing the questionnaires, participants were told that the computer task they had completed was a new psychological measure that assesses unconscious feelings of intimacy people desire for their partners. Consistent with the logic of the associative priming task, they were told that people who desire a lot of intimacy identify positive words faster and negative words slower after seeing their partner's face whereas people who desire less intimacy identify positive words slower and negative words faster after seeing their partner's face. All participants were then given false feedback that they scored in the 89th percentile on the measure, indicating that they desired a high level of intimacy with their partner. Similar to Study 1, the research assistant offhandedly told participants that sharing such information with the partner can benefit relationships and then offered them the opportunity to share a printout of the results with their partner by signing a release of feedback form. Whether or not they did so served as the dependent variable. As in Study 1, the research assistant (a) informed participants that the partner was involved in an unrelated task and would not learn of their option to provide the information if they decided not to reveal it and (b) left the room before participants indicated their response. After five minutes, the research assistant then reentered the room and recorded whether or not participants signed the form, debriefed them, and thanked for their participation.

Measures

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was again assessed with the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .90.)

Relational self-construal

Relational self-construal was again assessed with the Relational-Interdependent Self-construal Scale (Cross et al., 2000). Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha was .81.)

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 3. As in Study 1, men and women reported self-esteem and relational self-construal scores that were above the midpoint, suggesting that these intimates had relatively high self-esteem and considered their relationships to be an important part of their identity, on average. Also as in Study 1, a paired-samples t-test revealed that women reported higher levels of relational self-construal than did men, t(37) = -3.51, p < .01. Men trended toward reporting higher levels of self-esteem than did women, t(37) = 1.69, p = .10. Twenty-nine (76%) men and twenty-five (66%) women chose to disclose their ostensibly high desires for intimacy to their partners. Men and women did not differ in their choice to reveal this information, t(74) = -1.02, p = .32.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables in Study 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | .05 | .03 | .03 | 31.26 | 4.95 |

| 2. Relational self-construal | -.02 | .14 | .49** | 64.47 | 7.78 |

| 3. Self-disclosure | -.28† | .64** | -.01 | 66% | |

|

| |||||

| M | 33.13 | 58.21 | 76% | ||

| SD | 4.94 | 8.94 | |||

Note. Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented above the diagonal for women and below the diagonal for men; correlations between men and women appear on the diagonal.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations among the independent variables are also presented in Table 3. Among both men and women, relational self-construal was positively associated with the disclosure of feelings of intimacy. Among men, self-esteem trended toward being negatively associated with the disclosure of feelings of intimacy. The primary analyses examined whether the association between self-esteem and disclosure varied across levels of relational self-construal.

Did Relational Self-construal Moderate the Association between Self-esteem and Willingness to Reveal Feelings of Intimacy?

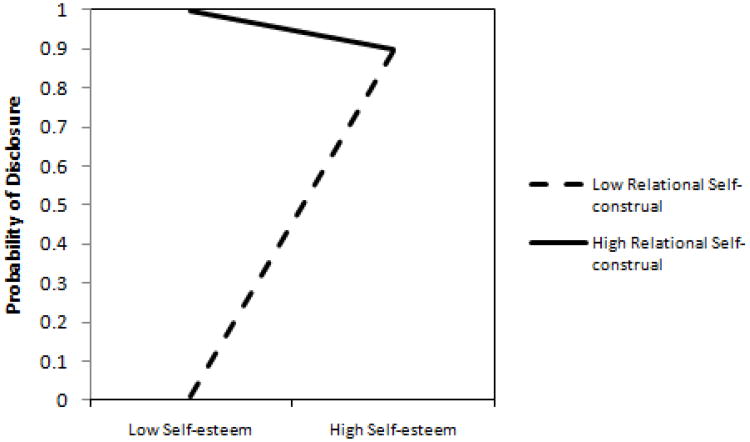

To examine whether relational self-construal moderated the association between self-esteem and the disclosure of desired intimacy, we used the same analysis strategy described in Study 1. Results are presented in Table 4. As can be seen there, relational self-construal was positively associated with the disclosure of feelings of intimacy. However, this main effect was qualified by a significant Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction. The significant interaction is plotted in Figure 2. Tests of the simple slopes revealed that self-esteem was negatively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on relational self-construal, t(71) = -3.17, p < 0.01, but was positively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on relational self-construal, t(71) = 4.10, p < 0.01. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal functions to determine whether LSEs are more or less likely than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Relational self-construal was positively associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on self-esteem, t(71) = 4.17, p < 0.01, but was not associated with disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on self-esteem, t(71) = 0.05, p = 0.96. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal would increase the probability that LSEs, but not HSEs, would engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Notably, subsequent analyses indicated the interaction was not moderated by participant sex, t(70) = 0.44, p = 0.66, and remained significant when participant sex was dropped from the model, t(72) = -3.26, p < 0.01.

Table 4.

Effects of Self-Esteem, Relational Self-Construal, and their Interaction on Willingness to Disclose Feelings of Intimacy in Study 2.

| Self disclosure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effect size | ||

| B | r | |

| Sex | -2.94** | .31 |

| Self-esteem (SE) | .09 | .17 |

| Relational self-construal (RSC) | .33** | .41 |

| SE X RSC | -.06** | .43 |

Note. For the t-test, df = 71.

= p < .01.

Figure 2.

Interactive Effects of Self-Esteem and Relational Self-Construal on Probability of Disclosing Feelings of Intimacy in Study 2.

Discussion

Study 2 provides further evidence that self-esteem interacts with relational self-construal to predict behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence in intimate relationships. Specifically, as predicted, LSEs who were high in relational self-construal were more likely than equivalent HSEs to disclose their high feelings of intimacy to their partners, whereas LSEs who were relatively low in relational self-construal were less likely than equivalent HSEs to disclose their high feelings of intimacy. Taken together, these two studies provide fairly compelling evidence for our prediction.

Study 3

Study 3 attempted to extend these findings in two important ways. First, Study 3 used recently-married couples' self-reports of self-esteem, relational self-construal, and self-disclosure to examine whether the effects that emerged on intimates' behavior in Studies 1 and 2 extended to reports of the behaviors they engage in during naturally-occurring interactions in marriages, relationships that should be relatively important. As noted earlier, although self-disclosure tends to increase interdependence between partners (e.g., Collins, & Miller, 1994; Laurenceau, Barett, & Pietromonaco, 1998; Reis & Shaver, 1988), it is risky because such disclosures can be met with an unfavorable response (e.g., Gable, Reis, Impett, & Asher, 2004). Second, Study 3 controlled for attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, each of which may account for the interactive effects of self-esteem and relational self-construal on behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Specifically, people who are high in attachment anxiety tend to have low self-esteem and value closeness (i.e., may be high in relational self-construal) (e.g., Feeney & Noller, 1990), and tend to be particularly likely to engage in behaviors intended to increase interdependence (e.g., Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). People who are high in attachment avoidance also tend to have low self-esteem but value independence (i.e., may be low in relational self-construal) (e.g., Feeney & Noller, 1990), and tend to avoid behaviors that increase interdependence. Accordingly, attachment anxiety may account for positive effect of self-esteem among people who are high in relational self-construal and attachment avoidance may account for the negative effect of self-esteem among people who are low in relational self-construal. Study 3 assessed and controlled for participants' reports of their attachment anxiety and avoidance to rule out these alternative interpretations. Once again, we predicted that intimates' levels of relational self-construal would moderate the effects of self-esteem on self-disclosure, such that low self-esteem would be negatively associated with self-disclosure among those low in relational self-construal but positively associated with self-disclosure among those high in relational self-construal, and that relational self-construal would be positively associated with self-disclosure among LSEs, but not among HSEs.

Method

Participants

Participants were 89 couples who had completed the fourth wave of data collection in a broader study of 135 newlywed couples. Data from this fourth wave were used here because it was first to assess all relevant variables. The couples not included in the current analyses had either (a) divorced (n = 12, 9%), (b) dropped from the study (n = 7, 5%), (c) been widowed (n = 1, 1%), or (d) did not complete all measures during the fourth phase of data collection (n = 26, 19%).

At baseline, participants were recruited through advertisements placed in community newspapers and bridal shops and through invitations sent to eligible couples who had applied for marriage licenses in counties near the study location. Couples who responded were screened in a telephone interview to ensure that they met the following eligibility criteria: (a) they had been married for less than 6 months, (b) neither partner had been previously married, (c) they were at least 18 years of age, (d) they spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires), and (e) did not yet have children (because a larger aim of the study was to examine the transition to parenthood).

At their baseline assessment, the husbands examined here were on average 26.06 years old (SD = 4.17) and had received 16.85 years (SD = 2.53) of education. Ninety percent were Caucasian and 74% were Christian. Sixty-nine percent were employed full time and 30% were full-time students. The wives examined here were 24.11 years old (SD = 3.43) at baseline and had received 19.91 years (SD = 2.29) of education. Ninety-five percent were Caucasian and 83% were Christian. Fifty-three percent were employed full time and 28% were full-time students. Participants who did not complete the fourth wave of data collection were not different from those that did complete it on any of these variables, except that husbands who completed the fourth wave had received more education than did the husbands who did not complete the fourth wave, t(134) = 3.90, p < .01.

Procedure

At the fourth wave of data collection, couples were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete at home and return by mail. This packet included measures of self-esteem, relational self-construal, self-disclosure, and attachment insecurity, as well as a letter instructing couples to complete all questionnaires independently of one another. Couples received $50 for participating in this phase of data collection.

Measures

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was again assessed with the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha was .90 for husbands and was .89 for wives.)

Relational self-construal

Relational self-construal was again assessed with the Relational-Interdependent Self-construal Scale (Cross et al., 2000). Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha was .87 for husbands and was .89 for wives.)

Self-disclosure

Self-disclosure was assessed with one face-valid item from the Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959). This item asked participants to report the extent to which they tend to “confide in their mate” using a 4-point Likert response scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (in everything).

Romantic attachment

Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were assessed with the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). The attachment anxiety subscale requires individuals to report agreement with 18 items (e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The attachment avoidance subscale requires individuals to report agreement with 18 items (e.g., “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Appropriate items were reversed and all items were summed. Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha for attachment anxiety was .94 for husbands and was .94 for wives and for attachment avoidance was .95 for husbands and .93 for wives.)

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 5. As the table reveals, as in Studies 1 and 2, husbands and wives reported self-esteem and relational self-construal scores that were above the midpoint, suggesting that these spouses had relatively high self-esteem and considered their relationships to be an important part of their identity, on average. Paired samples t-tests revealed that husbands reported greater attachment avoidance than did wives, t(81) = 2.71, p = .01, and that wives reported greater tendencies to confide in their partner than did husbands, t(82) = -2.16, p = .03. However, husbands and wives did not differ in their reports of self-esteem, t(82) = -.82, p = .42, relational self-construal, t(82) = -.04, p = .97, or attachment anxiety, t(81) = -1.02, p = .31.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables in Study 3.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | .19† | .03 | .03 | -.51** | -.30** | 34.66 | 5.02 |

| 2. Relational self-construal | .09 | .13 | -.01 | -.11 | -.06 | 57.03 | 10.75 |

| 3. Self-disclosure | .18 | .14 | .25* | -.23* | -.46** | 3.45 | .55 |

| 4. Attachment anxiety | -.50** | -.05 | -.20 | .37** | .54** | 37.55 | 20.31 |

| 5. Attachment avoidance | -.44* | -.45** | -.39** | .62** | .45** | 32.43 | 14.12 |

|

| |||||||

| M | 34.16 | 57.01 | 3.29 | 35.05 | 37.70 | ||

| SD | 5.73 | 10.97 | .62 | 19.53 | 18.84 | ||

Note. Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented above the diagonal for wives and below the diagonal for husbands; correlations between husbands and wives appear on the diagonal.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations among the independent variables are also presented in Table 5. Among both husbands and wives, self-esteem was negatively associated with both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. Further, among both husbands and wives, attachment avoidance was negatively associated with self-disclosure and positively associated with attachment anxiety. Among husbands, but not wives, relational self-construal was negatively associated with attachment avoidance. Among wives, but not husbands, attachment anxiety was negatively associated with self-disclosure. Self-esteem was unrelated to self-disclosure among both husbands and wives. Finally, husbands' and wives' reports of self-disclosure, attachment anxiety, and attachment avoidance were correlated with one another.

Did Relational Self-construal Moderate the Association between Self-esteem and Self-disclosure?

To examine whether relational self-construal moderated the association between self-esteem and self-disclosure, we again estimated a two-level model using the HLM 6.08 computer program. Specifically, self-disclosure scores were regressed onto mean-centered self-esteem scores, mean-centered relational self-construal scores, the Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction, a dummy-code of participant sex, and mean-centered attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance scores. The non-independence of husbands' and wives' reports was controlled in the second level of the model that allowed for a randomly varying intercept.

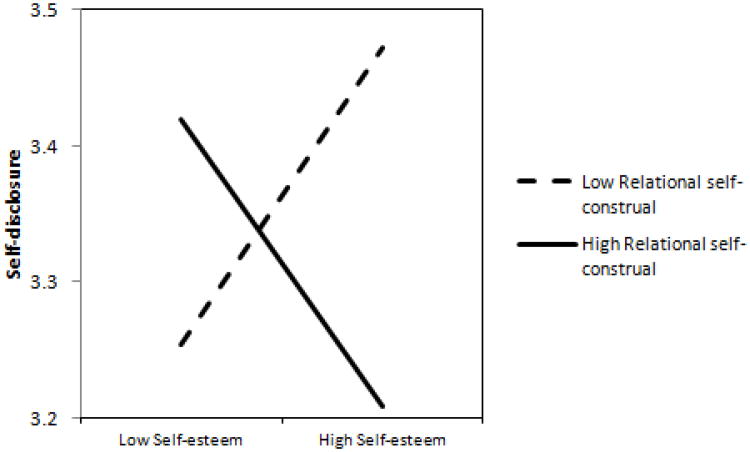

Results are presented in Table 6. As can be seen there, attachment avoidance was negatively associated with self-disclosure. Further, as predicted, the Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction was significantly associated with self-disclosure. The significant interaction is plotted in Figure 3. Tests of the simple slopes revealed that self-esteem was marginally negatively associated with self-disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on relational self-construal, t(156) = -1.83, p = 0.07, but was marginally positively associated with self-disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on relational self-construal, t(156) = 1.70, p = 0.09. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal functions to determine whether LSEs are more or less likely than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Relational self-construal was not associated with self-disclosure among people who were one standard deviation below the mean on self-esteem, t(156) = 1.29, p = 0.20, but was negatively associated with self-disclosure among people who were one standard deviation above the mean on self-esteem, t(156) = -2.24, p = 0.03. This pattern contrasts our prediction that relational self-construal would increase the probability that LSEs, but not HSEs, would engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Notably, subsequent analyses indicated the interaction was not moderated by participants' sex, t(155) = 0.06, p = 0.95, and remained significant when participant sex and both types of attachment insecurity were dropped from the model, t(161) = -3.13, p < .01. Also notably, subsequent analyses indicated that the Self-esteem X Relational Self-construal interaction remained marginally significant when controlling for the Self-esteem X Attachment Anxiety and Self-esteem X Attachment Avoidance interactions, t(154) = -1.93, p = .06.

Table 6.

Effects of Self-Esteem, Relational Self-Construal, and their Interaction on Self-Disclosure in Study 3.

| Self-disclosure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effect size | ||

| B | r | |

| Sex | .06 | .07 |

| Attachment anxiety | .02 | .03 |

| Attachment avoidance | -.27** | .38 |

| Self-esteem (SE) | .00 | .00 |

| Relational self-construal (RSC) | -.03 | .05 |

| SE X RSC | -.20** | .22 |

Note. For the t-test, df = 156.

= p < .01.

Figure 3.

Interactive Effects of Self-Esteem and Relational Self-Construal on Self-Disclosure in Study 3.

Discussion

Study 3 extended the effects of Studies 1 and 2 in several ways. First, Study 3 demonstrates that, in addition to interacting to predict self-disclosure in an artificial lab setting, self-esteem and relational self-construal interact to predict a single-item measure of the extent to which spouses confide in one another in marriage, a naturally-occurring behavior that can risk rejection to increase interdependence. Specifically, self-esteem was marginally negatively associated with reports of the tendency to confide in the partner among spouses who were relatively high in relational self-construal but marginally positively associated with reports of the tendency to confide in the partner among spouses who were relatively low in relational self-construal. Unexpectedly, however, relational self-construal was not associated with self-disclosure among LSEs, but was negatively associated with self-disclosure among HSEs. This interactive effect emerged independent of a strong correlate of both self-esteem and behaviors that increase interdependence—attachment insecurity. Further, although the single-item measure could be construed as a liability in the absence of Studies 1 and 2, the fact that this one-item measure replicated the results of those studies is impressive.

Study 4

In Study 4, we sought to extend the effects of self-esteem and relational self-construal to behaviors other than self-disclosure and to demonstrate the causal nature of these effects. Specifically, we experimentally manipulated self-esteem and relational self-construal and measured intimates' willingness to risk rejection by engaging in various behaviors that increase interdependence. We also again measured and controlled for attachment anxiety and avoidance. Once again, we predicted that intimates' levels of relational self-construal would moderate the effects of their self-esteem on their willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence, such that low self-esteem would predict less willingness to engage in such behaviors among those low in relational self-construal but more willingness to engage in such behaviors among those high in relational self-construal. One again, we also expected that relational self-construal would increase the probability that LSEs, but not HSEs, would be willing to increase interdependence.

Method

Participants

Participants were 182 undergraduate students (91 men, 90 women, 1 did not report sex) at a large university in the southeastern United States. Participants had a mean age of 19.78 years (SD = 2.71). All participants were required to have been involved in a romantic relationship for at least three months to participate in the study. One hundred and fifty (82%) identified as White or Caucasian, 15 (8%) identified as Black or African American, 6 (3%) identified as Asian American, 3 (2%) identified as Hispanic or Latino(a), 1 (1%) identified as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and 7 (4%) identified as another race/ethnicity, two or more races/ethnicities, or did not report race/ethnicity.

Procedure

Participants received partial course credit for completing the study online at surveymonkey.com. First, participants completed measures of romantic attachment and the Big Five Personality Inventory (Goldberg, 1999), which was intended to set up the manipulation of self-esteem. Next, to manipulate participants' relational self-construal, half of the participants were randomly assigned to read a story that primed relational self-construal and half were randomly assigned to read a story that primed independent self-construal (Trafimow, Triandis, & Goto, 1991). Specifically, all participants read a story about a military general who is trying to decide who to promote. Those randomly assigned to the relational self-construal condition read a version of the story in which the general eventually decides to promote a warrior who is a member of his family. In contrast, those randomly assigned to the independent self-construal condition read a version of the story where the general eventually decides to promote a warrior who is best qualified for the position. Prior research demonstrates that reading each version of the story successfully makes relational and individual aspects of the self more cognitively accessible (Trafimow, Triandis, & Goto, 1991, Study 2). Next, participants were told that the computer had scored the results of Big Five Personality Inventory and that they would be seeing those results. To manipulate participants' self-esteem, half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive positive feedback about their relational appeal and half were randomly assigned to receive negative feedback about their relational appeal. Specifically, participants randomly assigned to experience high self-esteem were told: “Based on the results from the questionnaires, we have determined that you are the kind of person who is rarely rejected by other people. For example, friends would rather spend time with you than with others, romantic partners choose to be with you easily, and you may receive a lot of approval from your family.” In contrast, participants randomly assigned to experience low self-esteem were told: “Based on the results from the questionnaires, we have determined that you are the kind of person who is often rejected by other people. For example, friends would rather spend time with others than with you, romantic partners may break up with you easily, and you may receive a lot of disapproval from your family.” Next, we refreshed the self-construal prime by having participants read a story about going on a trip downtown and count the pronouns in it (Gardner, Gabriel & Lee, 1999). Participants originally assigned to the relational self-construal condition read a version of a story that contained mostly plural pronouns (e.g., “We,” “our”), whereas those who were in the independent self-construal condition read a version of the story that contained mostly singular pronouns (e.g., “I,” “me”). Finally, participants completed self-esteem and relational self-construal manipulation checks and a measure of their willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence in their relationship.

Measures

Self-construal manipulation check

To determine whether our self-construal manipulation led participants to experience higher versus lower levels of relational self-construal, we administered one item from the Relational-Interdependent Self-construal Scale (i.e., “In general, my close relationships are an important part of my self-image”; Cross et al., 2000).

Self-esteem manipulation check

To determine whether our manipulation of self-esteem led participants to experience higher versus lower levels of self-esteem, we administered one item from the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale (i.e., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”).

Behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence

We developed a measure that assessed participants' willingness to engage in various behaviors that can risk rejection to increase interdependence in their current relationship. This measure required individuals to report their agreement with 33 behaviors that tend to strengthen close relationships (Stafford & Canary, 1991), yet may be met with rejection, such as expressing affection (e.g., “Show your love to a partner”), making sacrifices (e.g., “Give up activities you enjoy to strengthen your relationship”), self-disclosure (e.g., “Discuss with your partner problems you might have with him or her”), seeking support (e.g., “Request help from your partner”), and providing support (e.g., “Cheer up your partner when he or she is down”) using a 5-point Likert response scale from 1 (not at all willing) to 5 (very willing). All items were summed. Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .97.)

Romantic attachment

Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were again assessed with the ECR (Brennan et al., 1998). Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha for attachment anxiety was .94 and for attachment avoidance was .95.)

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 7. As the table reveals, participants reported being relatively willing to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. Furthermore, participants reported attachment anxiety and avoidance scores that were below the midpoint, suggesting that most participants experienced relatively secure attachment. Willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence was positively associated with our manipulation of relational self-construal, negatively associated with attachment avoidance, and marginally negatively associated with attachment anxiety.

Table 7.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables in Study 4.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. Relational self-construal | .05 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. Interdependence behaviors | .03 | .21** | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. Attachment anxiety | -.01 | .05 | -.14† | -- | -- |

| 5. Attachment avoidance | -.02 | .00 | -.30** | .51 | -- |

|

| |||||

| M | -- | -- | 129.86 | 45.51 | 48.82 |

| SD | -- | -- | 23.34 | 19.26 | 20.89 |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Manipulation checks

Confirming the effectiveness of our two manipulations, participants in the high self-esteem condition (M = 3.30, SD = 0.69) reported greater self-esteem than did the participants in the low self-esteem condition (M = 2.73, SD = 1.01), t(179) = 4.48, p < .01, and participants in the relational self-construal condition (M = 5.37, SD = 1.41) reported greater relational self-construal than did participants in the independent self-construal condition (M = M = 4.63, SD = 1.96), t(179) = 2.96, p < .01.

Did Relational Self-construal Moderate the Association between Self-esteem and Willingness to Increase Interdependence?

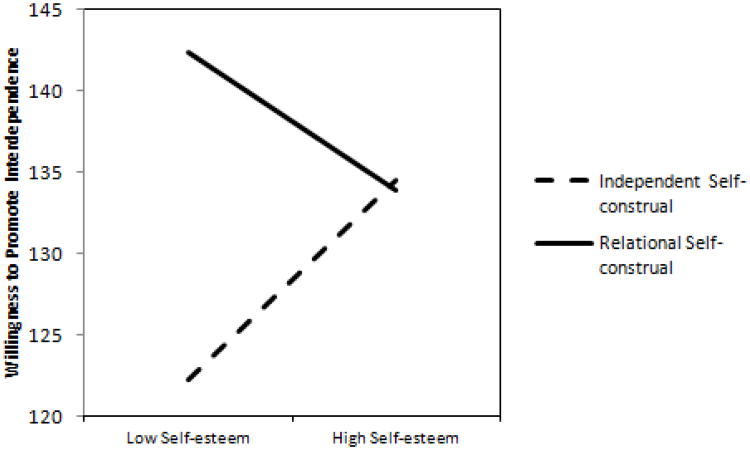

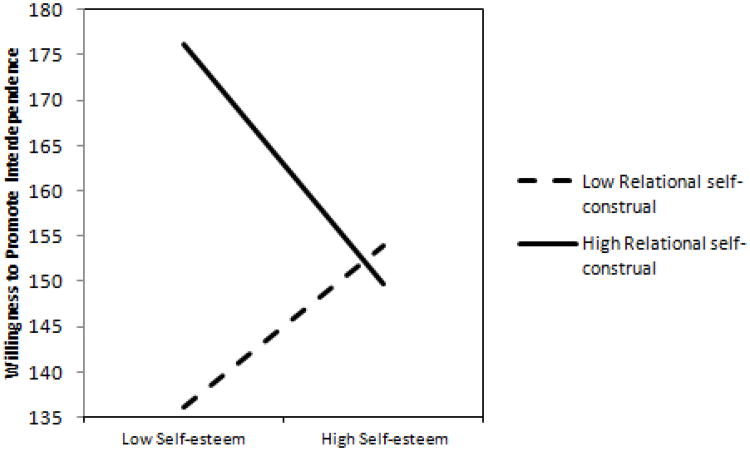

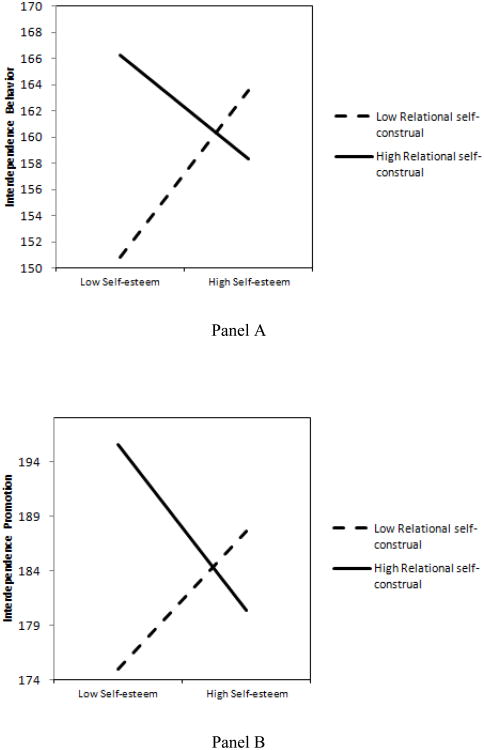

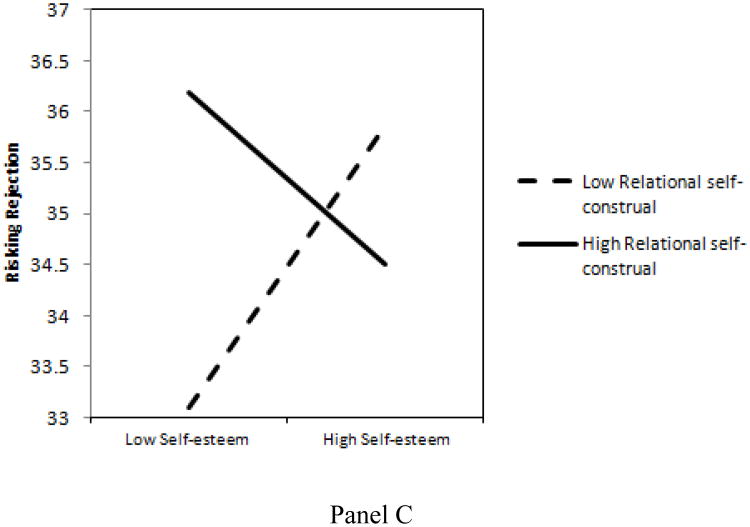

To examine whether relational self-construal moderated the association between self-esteem and willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence, we regressed willingness scores onto a dummy-code of the self-esteem manipulation, a dummy-code of the relational self-construal manipulation, the Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction, mean-centered attachment anxiety and avoidance scores, and a dummy-code of participant sex. Results are presented in Table 8. As in Study 3, attachment avoidance was negatively associated with participants' reports of their willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. Further, the relational self-construal and self-esteem manipulations were positively associated with willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. However, as predicted, these main effects were qualified by a significant Self-Esteem X Relational Self-Construal interaction. The significant interaction is plotted in Figure 4. Consistent with the findings of Studies 1-3, leading participants to feel high levels of self-esteem predicted a decreased willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence among those exposed to the relational self-construal manipulation, t (174) = -1.97, p = 0.05, but an increased willingness to engage in such behaviors among those exposed to the independent self-construal manipulation, t (174) = 2.53, p = 0.01. This pattern supports our prediction that relational self-construal functions to determine whether LSEs are more or less likely than HSEs to engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Leading participants to have higher levels of relational self-construal predicted a higher willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence among those who were led to feel low levels of self-esteem, t (174) = 4.39, p < 0.01, but did not affect willingness to engage in such behaviors among those who were led to feel high levels of self-esteem, t (174) = -0.13, p = 0.90. This pattern is consistent with the prediction that relational self-construal would increase the probability that LSEs, but not HSEs, would engage in behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Notably, subsequent analyses indicated the interaction was not moderated by participants' sex, t(171) = 0.50, p = 0.62, and remained significant when participant sex and both forms of attachment insecurity were removed from the model, t(177) = -2.60, p = .01. Furthermore, subsequent analyses indicated that the Self-esteem X Relational Self-construal interaction remained significant when controlling for the Self-esteem X Attachment Anxiety and Self-esteem X Attachment Avoidance interactions, t(172) = -3.28, p < .01.

Table 8.

Effects of Self-esteem, Relational Self-construal, and their Interaction on Willingness to Promote Interdependence in Study 4.

| Willingness to Promote Interdependence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effect size | ||

| B | r | |

| Sex | -2.47 | .06 |

| Attachment anxiety | .01 | .01 |

| Attachment avoidance | -.37** | .30 |

| Self-esteem (SE) | 12.26* | .19 |

| Relational self-construal (RSC) | 20.13** | .32 |

| SE X RSC | -20.73** | .23 |

Note. For the t-test, df = 174.

= p < .05,

= p < .01.

Figure 4.

Interactive Effects of Self-Esteem and Relational Self-Construal on Willingness to Promote Interdependence in Study 4.

Discussion

Study 4 substantially extended the effects of Studies 1-3 in several ways. First, whereas Studies 1-3 demonstrated that the interaction between self-esteem and relational self-construal was associated with behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence, Study 4 provided evidence for the causal effects of this interaction. Second, whereas Studies 1-3 demonstrated evidence that relational self-construal moderates the association between self-esteem and self-disclosure, Study 4 demonstrated that relational self-construal moderates the effect of self-esteem on intimates' willingness to engage in other behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence, such as sacrificing for a partner and seeking support from the partner.

Nevertheless, the consistent evidence provided by Studies 1-4 is limited in two important ways. First, it remains possible that these effects are limited to situations in which the risk of rejection is relatively low. Indeed, other research has demonstrated that LSEs frequently engage in behaviors that increase interdependence in situations that pose a relatively low risk of rejection (e.g., Murray et al., 2008), and (a) participants in Studies 1 and 2 were specifically told that their disclosures may benefit their relationships and (b) participants in Studies 3 and 4 may have believed the behaviors we assessed posed little risk of rejection. Second, Studies 1-4 did not examine whether indicators of relationship quality may moderate the association between self-esteem and behaviors that increase interdependence. In particular, it remains possible that variables that capture the importance of participants' relationships, such as relationship satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, or closeness either account for the observed results or similarly moderate the effects of self-esteem on behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Study 5 addressed both remaining issues.

Study 5

In Study 5, we followed procedures used by Murray and colleagues (2008) to experimentally manipulate the salience of rejection in order to determine whether the interactive effects of self-esteem and relational self-construal on behaviors that can increase interdependence emerge even when the risk of rejection is salient. Specifically, after reporting self-esteem and relational self-construal, but before reporting their willingness to engage in behaviors that can increase interdependence, participants described either an episode of rejection or an innocuous event. Additionally, we measured several other variables, i.e., relationship satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, and closeness, and examined whether those variables also moderated the effect of self-esteem on behaviors that risk rejection to increase interdependence. Notably, we assessed such behaviors using the same measures used by Murray and colleagues (2008), in an attempt to replicate the positive main effects of self-esteem that they observed on these measures. We expected participants' relational self-construal and self-esteem to interact to predict their willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence in the same manner observed in Studies 1-4, even when the risk of rejection was salient.

Method

Participants

Participants were 196 undergraduate students (59 men, 137 women) at a large university in the southeastern United States. Participants had a mean age of 19.38 years (SD = 2.77). All participants were required to have been involved in a romantic relationship for at least three months to participate in the study. One hundred and seventy (82%) identified as White or Caucasian, 13 (6%) identified as Black or African American, 5 (2%) identified as Asian American, 3 (1%) identified as Hispanic or Latino(a), and 5 (2%) identified as another race/ethnicity or two or more races/ethnicities.

Procedure

Participants received partial course credit for completing the study online at surveymonkey.com. First, participants completed measures of self-esteem, relational self-construal, relationship satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, closeness, and romantic attachment. Next, we manipulated the salience of interpersonal risk by randomly assigning half of the participants to describe a time when they were hurt or rejected by a significant other and half to describe their commute to school. Murray and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that this manipulation indeed leads participants to feel more versus less vulnerable to interpersonal rejection. Finally, participants completed a manipulation check and the same measures of willingness to engage in behaviors that can increase interdependence used by Murray and colleagues (2008).

Measures

Risk manipulation check

A measure of fear of disclosure served as an indirect measure of the success of our manipulation. This measure required individuals to report agreement with 7 items that assess their fear of disclosure (e.g., “I feel uncomfortable expressing my true feelings to my partner,” “I might be afraid to confide my innermost feelings to my partner”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All items were summed and higher scored indicate greater fear of disclosure. Internal consistency was adequate. (Coefficient alpha was .85.)

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was again assessed with the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .93.)

Relational self-construal

Relational self-construal was again assessed with the Relational-Interdependent Self-construal Scale (Cross et al., 2000). Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .91.)

Willingness to increase interdependence

Participants' willingness to increase interdependence was assessed with Murray and colleagues' (2008) interdependent situations and activities scales. These measures require individuals to report their willingness to put themselves in 17 situations of interdependence (e.g., ask the partner to “give me advice about problems”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (not at all willing) to 7 (very willing) and to prioritize 15 interdependent activities (e.g., “making my partner happy”) using a 7-point Likert response scale from 1 (not at all actively) to 7 (extremely actively). Following Murray et al. (2008), we reversed all appropriate items and summed all items to create one index of intimates' willingness to engage in behaviors that enhance interdependence. Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha was .92.)

Romantic attachment

Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were again assessed with the ECR (Brennan et al., 1998). Internal consistency was high. (Coefficient alpha for attachment anxiety was .93 and for attachment avoidance was .93.)

Alternative moderators

To identify whether relationship satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, and closeness also moderated the effects of self-esteem on behaviors that increase interdependence, participants also completed a version of the Quality Marriage Index (Norton, 1983) that was modified to ask about the “relationship” rather than the marriage (Coefficient alpha was .86.), Rusbult and colleagues' commitment scale (Rusbult, Kumashiro, Kubacka, & Finkel, 2009; Coefficient alpha was .95.), the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (Schaefer & Olson, 1981; Coefficient alpha was .94.), and the Relationship Closeness Inventory (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, 1989; Coefficient alpha was .84.).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 9. As the table reveals, participants reported being relatively willing to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. Furthermore, participants reported self-esteem and relational self-construal scores that were above the midpoint, suggesting that most participants had relatively high in self-esteem and considered their relationships to be an important part of their identity, on average. Notably, women (M = 59.68, SD = 11.07) reported considerably higher relational self-construal scores than did men (M = 53.21, SD = 14.93), t(194) = -3.37, p < .01. Participants reported attachment anxiety and avoidance scores that were below the midpoint, suggesting that most participants experienced relatively secure attachment. Finally, participants reported relationship satisfaction, commitment, and intimacy scores that were above the midpoint, suggesting that most participants believed that their relationships were relatively high in quality, yet relationship closeness scores that were slightly below the midpoint.

Table 9.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables in Study 5.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-esteem | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. Relational self-construal | .21** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. Interdependence-promotion | .26** | .51** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. Attachment anxiety | -.42** | -.09 | -.30** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5. Attachment avoidance | -.32** | -.39** | -.53** | .52** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6. Relationship satisfaction | .21** | .31** | .38** | -.54** | -.59** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7. Relationship commitment | .10 | .44** | .52** | -.22** | -.58** | .51** | -- | -- | -- |

| 8. Relationship intimacy | .29** | .37** | .44** | -.46** | -.66** | .66** | .56** | -- | -- |

| 9. Relationship closeness | -.19** | -.02 | .16* | -.10 | -.14 | .14* | ** | -.01 | -- |

|

| |||||||||

| M | 31.85 | 57.93 | 154.65 | 42.58 | 42.43 | 37.51 | 87.87 | 142.66 | 105.36 |

| SD | 6.18 | 12.64 | 26.62 | 20.13 | 19.50 | 6.54 | 23.57 | 21.92 | 20.36 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations among the independent variables are also presented in Table 9. Importantly, replicating prior work (e.g., Gaucher, et al., in press; Murray et al., 1998, 2002, 2009a), self-esteem was positively associated with willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence. Nevertheless, this main effect was moderated by participant sex, t(192) = -2.10, p = .04, such that self-esteem was positively associated with willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence among men, t(192) = 4.04, p < .01, but only trended toward predicting such behaviors among women, t(192) = 1.46, p = .11. Willingness to engage in behaviors that increase interdependence was also positively associated with relational self-construal and negatively associated with attachment anxiety and avoidance. Furthermore, self-esteem was positively associated with relational self-construal, relationship satisfaction, and intimacy, and negatively associated with attachment anxiety and avoidance and relationship closeness. Finally, relational self-construal was positively associated with relationship satisfaction, commitment, and intimacy, and negatively associated with attachment avoidance.

Manipulation check

Participants who were primed with rejection (M = 17.41, SD = 8.00) were marginally more afraid of disclosure than were participants who were not primed with rejection (M = 15.25, SD = 8.45), t(195) = 1.83, p = .07, providing some support for the effectiveness of our manipulation.

Did Relational Self-construal Moderate the Association between the Self-esteem and Willingness to Increase Interdependence?