Abstract

In the past few decades, many investigations in the field of plant biology have employed selectively neutral, multilocus, dominant markers such as inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), random-amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) to address hypotheses at lower taxonomic levels. More recently, sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers have been developed, which are used to amplify coding regions of DNA with primers targeting open reading frames. These markers have proven to be robust and highly variable, on par with AFLP, and are attained through a significantly less technically demanding process. SRAP markers have been used primarily for agronomic and horticultural purposes, developing quantitative trait loci in advanced hybrids and assessing genetic diversity of large germplasm collections. Here, we suggest that SRAP markers should be employed for research addressing hypotheses in plant systematics, biogeography, conservation, ecology, and beyond. We provide an overview of the SRAP literature to date, review descriptive statistics of SRAP markers in a subset of 171 publications, and present relevant case studies to demonstrate the applicability of SRAP markers to the diverse field of plant biology. Results of these selected works indicate that SRAP markers have the potential to enhance the current suite of molecular tools in a diversity of fields by providing an easy-to-use, highly variable marker with inherent biological significance.

Keywords: biogeography, conservation, dominant markers, hybridization, SRAP, systematics

Ecological and systematic studies often depend on the use of molecular tools to address questions regarding genetic relatedness among individuals, population structure, and phylogenetic relationships, as well as mapping loci and tracking quantitative traits. Molecular systematic studies of plants have frequently depended on chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) sequences as a primary source of data for investigations in delimitation of high-order taxonomic groups (for reviews, see Olmstead and Palmer, 1994; Petit et al., 2005). Some universal primers for noncoding regions have been developed (e.g., trnL-trnF and trnK/matK) and widely applied in such studies. More recently, primers for previously unexploited, fast-evolving cpDNA regions (Small et al., 1998; Shaw et al., 2005, 2007) and nuclear loci have provided increased resolution for taxonomic and systematic investigations. PCR-based dominant marker systems, such as random-amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD; Williams et al., 1990), inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR; Zietkiewicz et al., 1994), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP; Vos et al., 1995), have shown systematic utility in discerning between higher-order relationships as well (Federici et al., 1998; Nair et al., 1999; Smissen et al., 2003; Pang et al., 2007), but are typically used for investigating more shallow taxonomic levels of variation (see Table 1 for marker comparison). Since the 1990s, these multilocus marker systems have been used to estimate genetic variation in plants because they produce numerous amplicons and do not require a priori sequence information for molecular characterization (Fang et al., 1997; Wolfe et al., 1998a; Aggarwal et al., 1999; Culley and Wolfe, 2001; Koopman et al., 2008).

Table 1.

A summary of the attributes of different dominant molecular markers used in plant biology, and a relative comparison of their attributes.

| Marker | PCR protocol | Genomic target | Relative cost | Dominance | Repeatability |

| RAPD | one-step | anonymous | low | dominant | moderate |

| ISSR | one-step | anonymous | low | dominant | high |

| AFLP | multistep | anonymous | moderate | mixed (low) | high |

| SRAP | one-step | coding | low | mixed (moderate) | high |

Note: AFLP = amplified fragment length polymorphism; ISSR = inter-simple sequence repeat; RAPD = random-amplified polymorphic DNA; SRAP = sequence-related amplified polymorphism.

Despite the potential for these dominant markers to produce useful data, some researchers have been hesitant to use them due to technical limitations. In the case of RAPDs, many studies have shown inconsistencies in data replication (Jones et al., 1997; Perez et al., 1998). Although generally thought to produce more repeatable results, ISSRs have been shown to be less productive in terms of polymorphisms detected for some primer combinations (Nguyen and Wu, 2005), and the AFLP technique involves numerous time-demanding steps (Vos et al., 1995). Further drawbacks of these methods include the ambiguity of fragment homology, or whether banding patterns represent heterozygous or homozygous loci. The lack of identified homology between bands of identical length generated by the same primer has also been reason for concern (Rieseberg, 1996; Vekemans et al., 2002; Simmons et al., 2007; Caballero and Quesada, 2010), but there is evidence that fragments of the same calculated size originate from the same locus and are homologous, at least at the intraspecific level (Koopman, 2005; Gort et al., 2006; Ipek et al., 2006). Therefore, the complications of homoplasy should not be a significant factor in dominant marker analyses, if restricted to one species or a group of closely related taxa. Although use of these molecular techniques to resolve phylogenetic relationships at higher taxonomic levels may be considered controversial, corrections for homoplastic fragments have been developed to reduce the rate of fragment incursion (Caballero et al., 2008; Gort et al., 2009; Caballero and Quesada, 2010). Although no single technique is universally applicable (for reviews, see Doveri et al., 2008; Arif et al., 2010), and all molecular marker approaches have inherent strengths and weaknesses, the selection of a particular method ultimately depends on the research question at hand and the degree of resolution needed.

A more recently developed, dominant marker technique, sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP; Li and Quiros, 2001) PCR, is simple, inexpensive, and effective for producing genome-wide fragments with high reproducibility and versatility (Table 1). These markers were originally developed for gene tagging in Brassica oleracea L. to specifically amplify coding regions of the genome with ambiguous primers targeting GC-rich exons (forward primers) and AT-rich promoters, introns, and spacers (reverse primers). The primers are 17 or 18 nucleotides long and consist of core sequences, which are 13 to 14 bases long. The first 10 or 11 bases starting at the 5′ end are “filler” sequences, maintaining no specific constitution. These are followed by the sequence CCGG- (forward) or -AATT (reverse). This core is followed by three selective nucleotides (random) at the 3′ end (see Li and Quiros, 2001, or Budak et al., 2004a, for specific sequence details). PCR amplification techniques (specifically annealing temperatures) have been modified by many to suit specific research needs (for review, see Aneja et al., 2012), but the original protocol was described as a two-phase process. Following an initial 4-min denaturation (94°C), a template generation phase includes five 1-min cycles of denaturation (94°C), low-temperature annealing (∼35°C), and elongation steps (72°C). This template is then amplified over 35 similar cycles employing a higher annealing temperature (∼50°C) and completed with an extended elongation step (2 min, 72°C). The most common approach reported to score fragments has been by simple presence/absence (0,1) via traditional electrophoresis and gel visualization. While this approach has presumably been used to minimize cost, forward primers can be fluorescently labeled and amplicons can be scored through capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Sun et al., 2007; Ahmad et al., 2008; Alwala et al., 2008; Alghamdi et al., 2012).

Like other dominant markers, SRAPs have demonstrated the ability to elucidate genetic variation at a variety of taxonomic levels (Uzun et al., 2009), but are often used for analyses of populations of inter- and intraspecific hybrids (Hale et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008). Analysis of SRAP data has frequently been employed for the construction of linkage maps (LM; Lin et al., 2003, 2009; Yeboah et al., 2007; Levi et al., 2011;D. Guo et al., 2012) and identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL; Chen et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Consequently, this system has been valuable for the improvement of agronomic crops (Zhang et al., 2005; Brown et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2010; Wright and Kelly, 2011). Many comparative studies have found SRAP markers provide comparable levels of variation to AFLP markers, but with significantly less technical effort and cost for similar levels of band-pattern variability and reproducibility (Li and Quiros, 2001; Levi and Thomas, 2007; Liu et al., 2007a; Wang et al., 2007; Lou et al., 2010). Further, codominance has been identified in up to 20% of SRAP markers examined (Li and Quiros, 2001), which is a higher rate than previously described for AFLP (Mueller and Wolfenbarger, 1999). These factors highlight the value of SRAP markers for examination of previously unexplored, nonmodel systems, and also for experimental ventures in developing countries.

Limitations of SRAP markers have not yet been described, as these markers are relatively new and their use is still in its early stages. Similar to other markers scored as dominant, SRAP amplicons cannot yield heterozygosity descriptors such as Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Conclusions made as to taxonomic placement of examined individuals, especially in cultivated taxa, may not be appropriate, as selective pressures (anthropogenic or otherwise) may have directly affected the patterns of diversity elucidated by SRAP markers (e.g., Ferriol et al., 2004a; D. Guo et al., 2012) and not reflect evolutionarily relevant systematic relationships.

Innovations in molecular marker systems are employed by many branches of the plant sciences to elucidate diversity, including both applied and academic pursuits. The distinction between approaches often does not lie in the systems examined, but in the nature of hypotheses addressed on the processes of evolution—natural vs. directed. Over the past decade, application of SRAP markers has gained momentum, especially in the applied plant sciences (for reviews, see Aneja et al., 2012; Wang, 2012). Based on the rapidly growing body of literature, we propose that the SRAP marker system could, and should, be applied to the fields of systematics, conservation, biogeography, and ecology. Here, we review the potential for SRAP markers in these areas of research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a review of the current literature, using all available databases, we surveyed more than 350 peer-reviewed papers utilizing SRAP markers, although there are many more to be found in journals published in languages other than English. The documents examined were predominantly associated with plant breeding, and demonstrated very little exploration of marker utility beyond this field. As many of these articles were directed at developing LM and QTL for agronomic crops, they presented limited descriptive information of amplified SRAP products and measures of diversity between accessions. Examination of these works revealed that only a subset (n = 171; Appendix S1 (63.4KB, docx) and S2 (61.6KB, docx) ) of examined papers provided descriptive data of SRAP loci examined and amplicon polymorphism demonstrating their value to the field of plant biology. We recorded information on taxon, number of individuals, number of loci, number of fragments generated per locus, number of polymorphic fragments generated per locus, and polymorphic fragment rate. Not all data necessary for calculation of these statistics were presented in all 171 references. In some instances, the number of fragments generated was not explicitly described as polymorphic or otherwise. In these cases, we report this value as the total number of bands, as to not overestimate the true rate of polymorphism, though this practice could underestimate the total number of bands generated per locus.

RESULTS AND APPLICATIONS

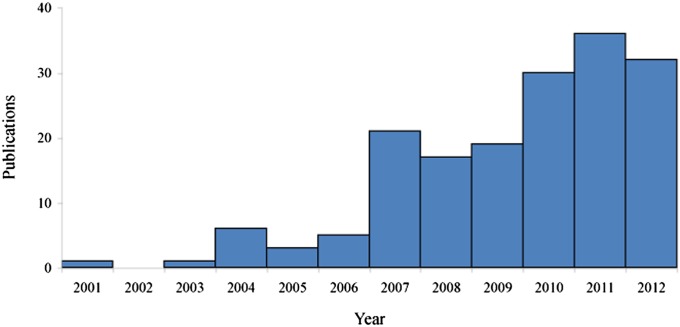

Based on our reviewed papers, it is evident that the application of SRAP markers has increased dramatically since their introduction in 2001, especially in the past few years (Fig. 1). Examination of the taxa evaluated and hypotheses addressed during this upswing in SRAP marker employment indicates a rise in awareness of the utility of these markers and a broadening of diversity in organisms examined. There was considerable variation in the descriptive statistics provided in the manuscripts examined (Appendix S1 (63.4KB, docx) ). The mean number of polymorphisms was 11.8 per locus in the 152 studies reporting this statistic, and of these, 65 (42.8%) reported more than 10 polymorphisms per locus. The rate of polymorphism averaged 68.7% across studies, but of the 118 citations explicitly reporting polymorphic rates, 27 (22.9%) indicated scored bands were over 90% polymorphic, and 56 (47.5%) studies noted over 80%.

Fig. 1.

Subset (n = 171) of publications reviewed in Appendix S1 (63.4KB, docx) employing SRAP markers by year of publication, demonstrating the increase in publication of SRAP use since its inception in 2001.

To further assess and demonstrate the general applicability and value of SRAP, we have highlighted case studies that exemplify the potential of these molecular markers in specific research areas of plant biology: population-level (intraspecific) systematics, hybridization, higher-order (interspecific or higher) systematics, biogeography, conservation genetics, and ecology.

Population-level (intraspecific) systematics

Through examination of models estimating genetic differentiation, studies of variation between populations may shed light on evolutionary processes affecting the relationships of analyzed groups. Due to their high yield of polymorphism examined via distance-based or probabilistic approaches, multilocus, dominant markers have been invaluable for describing relatedness within and among populations (Nybom, 2004).

The vast majority of SRAP studies have focused on intraspecific relations of highly related, cultivated taxa. This has been due to the nature of scoring dominant markers (Wolfe and Liston, 1998; Nybom, 2004), but also to the primary users of SRAP markers—plant breeders—working to enhance the productivity and efficiency of selection through review of variation within populations of elite hybrid progeny (Y. Y. Li et al., 2007; Levi et al., 2011; D. Guo et al., 2012; Y. Li et al., 2012) and germplasm collections (Ferriol et al., 2003, 2004a, 2004b; He et al., 2007; Y. Chen et al., 2010; Amar, 2012). In contrast with phenotypic data, molecular variation has generally decreased with cultivation (for reviews, see Clegg et al., 1984; Duvick, 1984; Sonnante et al., 1994; Lashermes et al., 1996; Sun et al., 2001; Whitt et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2006) because many modern agricultural crops are derived from limited selections of wild progenitors (Ferriol et al., 2004a; Wills and Burke, 2006), although this trend has been reversing in recent years with application of molecular tools (Reif et al., 2005). The majority of SRAP investigations have focused on agronomic applications, and demonstrated the capacity to uncover discrete genetic diversity within advanced hybrid lineages. Such genetic distinction between different cultivated lineages within taxa can be considered analogous to projects interested in describing intraspecific or population-level variation found in wild-collected accessions. SRAP markers have demonstrated their utility by elucidating greater levels of variation within groups of highly related individuals when used in conjunction with other markers for comparative purposes, including RAPD (Zeng et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2010; Comlekcioglu et al., 2010), ISSR (Yeboah et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012), simple sequence repeat (SSR; Wang et al., 2010; Isk et al., 2011; D. Guo et al., 2012), or AFLP (Ferriol et al., 2004b; Zhao et al., 2007; Devran et al., 2011; Youssef et al., 2011), and have proven their utility by elucidating greater levels of variation between examined individuals.

Case studies

Euodia rutaecarpa (A. Juss.) Benth. (Rutaceae) is a woody Asian shrub, the fruit of which has been used in traditional Chinese medicine. Recognized varieties of this species have been cultivated widely, and differentiation between regional populations has been noted (Liang, 2011). Subspecific classifications have been based on macro-level morphology (Miki et al., 1999), although distinguishing traits demonstrate significant variation due to human selection and hybridization, as well as seasonal and environmental effects. This regional differentiation has been confirmed on the molecular level with the internal transcribed spacer (ITS; Huang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009). Although cluster analysis could not effectively distinguish between all taxonomic varieties, E. rutaecarpa var. rutaecarpa appeared distinct from varieties officinalis (Dode) C. C. Huang and bodinieri (Dode) C. C. Huang. To further examine the potential for geographic and varietal genetic variation, Wei et al. (2011) employed AFLP and SRAP to examine the relationship between cultivated accessions of E. rutaecarpa var. rutaecarpa and E. rutaecarpa var. officinalis, and to compare the utility of the two marker systems. SRAP loci produced fewer scorable fragments than AFLP (188 vs. 353), but yielded a higher rate of polymorphism (77.1% vs. 64.6%) and more variety-specific bands. Calculations of Nei’s genetic diversity and Shannon’s information index demonstrated that SRAP revealed higher levels of variation within and between these taxa than AFLP. Examination of genetic distance over populations (accessions grouped by province) suggested a higher level of divergence in populations from SRAP banding patterns than AFLP in both var. rutaecarpa (0.1002 vs. 0.0498) and var. officinalis (0.2086 vs. 0.1231). Similarly, unweighted pair-group method analyses (UPGMA) of both individual accessions and groups clustered by provincial origin yielded nearly identical topologies for both markers, but the SRAP-based tree had slightly higher correspondence to the distance measure (rSRAP = 0.98, rAFLP = 0.94). While both markers successfully distinguished between the varieties of E. rutaecarpa examined, the authors proposed SRAP was the preferred method, due to higher genetic distance and polymorphism.

More widely grown crops have been examined by SRAP analysis as well, including the cultivated grape, Vitis vinifera L. (Vitaceae). Variation in accessions of this species, interspecific hybrids, and other horticulturally important grape taxa was illuminated by SRAP markers by L. Guo et al. (2012). Three primary groups were revealed by SRAP analysis, based on taxonomic status (V. vinifera vs. related taxa) and usage (table grape vs. wine grape within V. vinifera). Of the two V. vinifera subgroups, one included all the table grape varieties, separating two established European cultivars and their known hybrid offspring from clusters of ancient Chinese varieties. The second V. vinifera assemblage demonstrated substructure as well, in the form of two primary subclusters: Euro-American varieties in one, and a second that congregated all of the wine grape accessions. The third distinct group included primarily wild taxa, as well as varieties used as rootstocks for grafting. This clade also demonstrated structure, with two subgroups segregated by geographic origins—species of Euro-American descent in one, and wild taxa from China in the second. SRAP phylogenies demonstrated agreement with previous molecular data describing geographic origin, horticultural use, and hybrid lineage among recently developed Vitis varieties and related species (Arroyo-Garcia et al., 2002; Aradhya et al., 2003).

Representatives from the genus Cucurbita L., along with Zea L., were the earliest domesticated crops in the New World, ca. 9000 yr before present (YBP) (Smith, 1997; Piperno et al., 2009), and are represented by numerous, diverse landraces (Lira-Saade, 1995). Examination of the economically valuable and morphologically diverse C. maxima Duchesne species complexes was carried out by Ferriol et al. (2004a). Germplasm from 50 C. maxima landraces was assessed using SRAP and AFLP markers. Results yielded similar rates of polymorphism, although AFLP yielded a greater number of polymorphic bands. Correlation between the AFLP and SRAP clustering patterns was very low (r = 0.31), potentially due to the differences in nature of the markers’ genetic targets. Principal coordinates analyses (PCoA) of these markers clustered accessions based on different characters. The first two axes in SRAP scatterplots clustered some taxa by morphology, including flesh color, as well as shape, to a lesser degree (e.g., “heart-shaped” varieties), whereas AFLP markers clustered accessions by region of origin. Some groups of morphologically similar accessions, including “turban” and “banana” types, clustered strongly together in both molecular approaches. Furthermore, both marker types indicated greater genetic distance in the nine accessions from the Americas than the 39 from Europe, suggesting a fraction of the C. maxima diversity has been exported and exploited by Old World agriculture. While SRAP results do not mirror the presumed neutral AFLP markers, they provide historical information and insight into the relationships of morphologically distinct lineages of these cultivated cucurbits.

Hybridization

Hybridization is thought to be one of the driving factors behind speciation (Mallet, 2007), and most significant in the genesis of novel taxa when combined with polyploidization (for reviews, see Soltis et al., 2004; Rieseberg and Willis, 2007; Wissemann, 2007; Soltis and Soltis, 2009). Allopolyploid progeny of hybridization events typically exhibit intermediate characters, but in some instances demonstrate either increases or decreases in fitness relative to parental taxa, which may be stabilized or enhanced in subsequent generations (for review, see Rieseberg, 1995). Homoploid hybridization is also an important mechanism for introducing genetic diversity into populations via introgression, and has been evident through examination of dominant markers (Arnold et al., 1991; Ungerer et al., 1998; Wolfe et al., 1998a, 1998b; O’Hanlon et al., 1999). Many different hypotheses of hybridization have been tested using SRAP markers at different taxonomic levels, although most have addressed variation at the population level in intraspecific hybrids (Hale et al., 2006, 2007; Liu et al., 2007b; Xuan et al., 2008). Some have relied on SRAP markers to depict interspecific hybridization as well (Yu et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2010), and even intergeneric hybrids (Hu et al., 2002), but the majority apply these markers to closely related taxa, where they are most unbiased.

Case studies

Selections of Paeonia L. (Paeoniaceae) have been cultivated in Eurasia for nearly three millennia, primarily for medicinal and ornamental purposes (Halda and Waddick, 2004). Thousands of hybrid cultivars exist today, including a significant proportion of interspecific and intersectional hybrids. The taxonomy of the genus is still in contention (Halda and Waddick, 2004; Hong, 2010). To examine the relationships between cultivated, intersectional Itoh hybrids and their parental lines from sections Paeonia (herbaceous) and Moutan (woody), Hao et al. (2008) assessed diversity of a collection of 29 cultivars with SRAP. Although overall banding patterns showed high levels of polymorphism (∼95%), some primers demonstrated robust amplification in sect. Paeonia while yielding no amplicons in sect. Moutan. The UPGMA tree (cophenetic correlation coefficient [CPCC] = 0.86) revealed two primary clusters separating the two taxonomic sections, and allied the examined hybrids with (maternal) sect. Paeonia. Subclusters within the Moutan and Paeonia groups were generally ambiguous, as the origins of the examined cultivars were not known, but there were some loose trends of grouping by flower color. One subcluster of the sect. Moutan taxa was distinct and had high levels of genetic similarity—a group of hybrids arising from the morphologically distinctive P. rockii (S. G. Haw & Lauener) T. Hong & J. J. Li. Similar to UPGMA analysis, PCoA aligned the Itoh hybrids closer to sect. Paeonia than sect. Moutan. The placement of the intersectional hybrids with the Paeonia group may be due to the ploidy level of parental taxa. According to Saunders and Stebbins (1938), hybridization between diploid (sect. Moutan) and tetraploid (sect. Paeonia) species was more fruitful, even across sections, than between homoploids of the same section. Results of SRAP similarity add weight to this finding by demonstrating strong genetic affinity of primary hybrids to the maternal genotypes. A greater maternal contribution has been demonstrated in many hybrids derived from parental types of mixed ploidy (Lashermes et al., 2000; Haw, 2001; Horita et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2003; Inomata, 2006).

Coffea arabica L. (Rubiaceae) is another agriculturally valuable polyploid, grown today under varying regimes on all continents with frost-free agricultural zones. The identification of varieties via morphological and genetic traits is extremely difficult, due to the limited variability of the narrow genetic base of genotypes grown. Coffea arabica is self-fertile, but produces significantly greater yields of larger seeds with outcrossing (Philpott et al., 2006), demonstrating the importance of genetic diversity in Coffea L. spp. seed set in both natural and cultivated environments. Decreases in seed production have been noted due to loss of pollinators (Klein et al., 2003) and the shallow genetic base of widely grown, cultivated varieties (Anthony et al., 2002), underscoring the need for methods to distinguish between plants of common lineage for both ecological and agricultural investigations. To enhance productivity of cultivated C. arabica, Mishra et al. (2011) employed SRAP markers to identify cultivated genotypes and their progeny in commercial hybrids. Selecting four cultivated varieties, researchers produced 60 intervarietal hybrid seedlings from six unique crosses, including two reciprocal crosses. Of the SRAP markers documented, 90 were shared exclusively with the maternal parents, and 48 with the paternal parents. Examination of banding patterns of reciprocal crosses suggested parental contributions varied depending on the direction of the hybrid cross. This result may suggest that SRAP primers amplify some nonnuclear material, or alternatively that there may have been differences in levels of heterozygosity between parental genotypes. Also, a small proportion of the markers scored were hybrid specific, suggesting recombination events.

Approaches of breeding and selecting annual, agronomic crops have evolved in a manner distinct from the methods used for long-lived, perennial species such as Paeonia and Coffea, due to their relatively short generation time. Systematic scoring of quantitative traits molecular markers directed the selection process for seasonal crops away from open-pollinated methods to favor development of multiple, distinct inbred lines to interbreed for enhancement of heterosis and uniformity (Tay, 2002). To assess the effectiveness of this hybridization strategy in production of an F1 cabbage hybrid (Brassica oleracea var. capitata ‘Zaoxia 16’), and the purity of resultant hybrid seed, Liu et al. (2007b) examined 210 F1 seedlings, as well as parental genotypes, with SRAP, RAPD, ISSR, and SSR markers. Results indicated that all tested markers were able to assess the purity of the study population at similar rates (94.3–94.8%). Analysis of SRAP markers indicated that these were the most robust relative to other markers, detecting more maternal- and paternal-specific markers per informative primer. The different molecular assays each flagged either 11 or 12 as putative false hybrids, whereas field observation of morphological characters only exposed seven of these. Nine of the 12 hybrids exhibited nearly identical banding patterns to the female parent, suggesting that they were probably derived from self-pollination.

Higher-order (interspecific) systematics

Higher-order systematic investigations, examining variation at or above the species level, have typically been done through comparison of cytoplasmic DNA sequences or highly conserved regions of the nuclear genome, but dominant markers have demonstrated value in estimating relative distance between taxa. Variation between species has been assessed by the use of dominant markers, including RAPD (Graham and McNicol, 1995; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Sun and Wong, 2001), ISSR (Wolfe et al., 1998a; Wolfe and Randle, 2001; Kumar et al., 2008), RFLP (Federici et al., 1998; Lakshmi et al., 2000), and AFLP (Loh et al., 2000; Sasa et al., 2009). SRAP markers have similarly demonstrated value in detecting interspecific variation in many cases (Fan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Talebi et al., 2011), although like other dominant markers, they are primarily used to address hypotheses involving lower-order systematics.

Case studies

Taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships within Citrus L. (Rutaceae) are unclear at best, due primarily to the promiscuity of related species and genera, centuries of cultivation, and wide geographic dispersion (Nicolosi et al., 2000). It has been proposed that there are only three “true” species of Citrus, and that cultivated varieties are a function of hybridization between closely related genera (e.g., Citrus with Poncirus Raf. or Fortunella Swingle) or spontaneous somatic mutations (Barrett and Rhodes, 1976). Uzun et al. (2009) investigated the systematics of Citrus using SRAP markers, utilizing a diverse group of 83 taxa dominated by cultivated species and interspecific hybrids, but representing all tribes and subtribes within the Rutaceae. Banding patterns demonstrated a very high recovery of rare fragments—over 63% were found in 5% or fewer of the taxa studied. Cluster analysis via UPGMA resulted in a strongly supported dendrogram (CPCC = 0.93) that maintained the arrangement of the currently accepted subtribes (Barrett and Rhodes, 1976), although relation of the “primitive citrus” and “near citrus” groups was less distinct relative to the “true citrus” clade. Intergeneric hybrids were genetically intermediate, but tended to cluster with the maternal parent. The genus Citrus was separated into two primary groups, one of which was subdivided into two distinct clusters, congruent with previous molecular work (Federici et al., 1998; Liang et al., 2007) in supporting proposals of few ancestral species (“three species” concept; Barrett and Rhodes, 1976). Accessions from the genus Fortunella clustered within the Citrus group; this pattern lacks consensus in current literature, although some have suggested that this genus is the closest relative to Citrus (Nicolosi et al., 2000; Barkley et al., 2006).

Following the discovery of SRAP utility in Citrus, SRAP markers were further exploited to address systematic hypotheses within Citrus. Investigations of distinction between groups as defined by the “three species” concept were conceived, involving the citron (C. medica L.; Uzun et al., 2011a), mandarin (C. reticulata Blanco; Uzun et al., 2011b), and pummelo (C. maxima (Burm.) Merr.; Uzun et al., 2011c). To examine the relative value of markers within this group, Amar et al. (2011) compared SRAP, SSR (or microsatellites), and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences from single nucleotide polymorphic (CAPS-SNP) markers in a Citrus germplasm collection. Of the markers, the highest number of total markers and polymorphic markers per locus were produced by SRAP, followed by SSR and CAP-SNP markers. Relative to other markers employed, SRAP primers yielded more than twice the number of polymorphic bands per primer and also demonstrated the highest average polymorphism information content (PIC).

The genus Hedychium L. (Zingiberaceae), known as the ginger lily group, is closely allied to true gingers (genus Zingiber Mill.), and is similarly used in regional, traditional medicine and perfume fragrance, and is also cultivated for its large, boldly colored flowers. Some of the ornamental taxa within Hedychium have become naturalized in regions outside their native ranges, including Australia (Csurhes and Hannan-Jones, 2008) and Hawaii (Funk, 2005), where they are considered aggressive weeds because they displace native flora and/or hybridize with endemic ginger lilies. Although over 100 species have been historically identified in this genus, the definitive number of taxa is still disputed (Wood et al., 2000). Gao et al. (2008) addressed this issue of species delimitation in Hedychium with one of the first molecular phylogenetic analyses, comparing 22 accessions with SRAP markers. Genetic similarities between individuals ranged from 0.08 to 0.97, although most were near 0.5. The similarity coefficient of H. flavescens Carey ex Roscoe and H. chrysoleucum Hook. was 0.97, supporting previous propositions of lumping of both taxa (among others) into the H. coronarium J. Koenig complex (Baker, 1892); although this evaluation has been debated by many (Turrill, 1914), it is not currently accepted (Burtt and Smith, 1972).

The genus Panicum L. is a cosmopolitan group within the Poaceae, comprising more than 450 species (Warmke, 1951; Webster, 1988). Although many of the taxa within this large group have not been subjected to comparative molecular analysis, switchgrass (P. variegatum L.) has been the focus of many groups due to its adaptability and promise for large-scale biomass production (McLaughlin et al., 1999; McLaughlin and Kszos, 2005; Bouton, 2007). To examine genetic diversity in cultivated switchgrass accessions and related taxa, Huang et al. (2011) applied SRAP and expressed sequence tag (EST)–SSR markers to a collection of 91 accessions of Panicum, representing 22 distinct species and 34 samples of P. variegatum. SRAP primers produced more polymorphic bands per combination (18 vs. 11.5), but similar rates of polymorphism (∼95%). Comparison of genetic distance calculated for the two marker systems suggested they were highly similar (Mantel’s r = 0.874, P < 0.01). Concordant with this result, AMOVA results attributed congruent levels of the variation among species with SRAP and EST-SSR markers (70.02% vs. 73.35%). Differentiation between markers was seen in their effectiveness to discover polymorphism, as SRAP markers had a marker index (sensu Powell and Morgante, 1996) almost twice as high as EST-SSR. Phylogenies indicated by UPGMA analysis of a combined data set agreed with recognized systematic arrangement (Aliscioni et al., 2003), as well as geographic origin of accessions. While both SRAP and EST-SSR distinguished Panicum species and related taxa with similar discriminating power, SRAP bands were presumed more efficient than EST-SSR for examining large Panicum collections, due to the higher rate of polymorphic band discovery. Although SRAP markers demonstrated an advantage in terms of polymorphism, it is important to note that the EST-SSR markers were developed specifically for P. variegatum (Kantety et al., 2002; Tobias et al., 2005), and that interspecific variation of SSR flanking regions may have decreased primer affinity at some loci in related taxa.

Biogeography

The distribution of plants examined through molecular analysis of genetic diversity has drastically enhanced our understanding of historical climatic, geographic, and ecological events. Analysis of population-level genetic variation has been examined with dominant markers within many contexts, including the effects of glacial refugia (for reviews, see Soltis et al., 1997, 2006; Schonswetter et al., 2005), systematics (Perrie et al., 2003; Smissen et al., 2003; McKinnon et al., 2008), and exotic plant invasion (Meekins et al., 2001; Ahmad et al., 2008). SRAP markers have been similarly employed to describe variation over broadly distributed populations, though examples are limited. These investigations have typically been undertaken to detect novel variation for breeding purposes (Feng et al., 2009), or in other cases, conservation of genetic resources in taxa threatened by human disturbance or overharvesting (Qian et al., 2009). Still, these studies demonstrate the applicability of SRAP markers to unveil molecular variation correlated to a geographic scale.

Case studies

Some of the earliest applications of SRAP markers beyond the Brassicaceae (Li and Quiros, 2001), for which it was developed, were in buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides (Nutt.) Engelm.). The relative value of SRAP to other commonly employed molecular markers (ISSR, RAPD, and SSR) in this species was examined by Budak et al. (2004a), comparing the ability of these approaches to detect genetic patterns in 15 accessions of buffalograss. SRAP markers produced a significantly greater number of variable fragments per locus (≥1.25 polymorphisms per locus) and rate of polymorphism (>13%) relative to other markers tested. The average genetic similarity was also highest as detected by SRAP markers, which was strongly correlated to RAPD results (r = 0.73). UPGMA dendrograms of SRAP-determined relatedness also had much higher bootstrap support relative to other markers. The authors concluded that SRAP markers “demonstrated better approximations to true variation within and among buffalograss cultivars,” and further pursued examination of this North American endemic herb with a larger germplasm collection of 53 accessions (Budak et al., 2004b). Samples in this study represented a combination of geographically diverse genotypes and cytotypes (2x, 4x, 5x, 6x) selected from both wild and hybrid lineages. Principal components and cluster analysis of SRAP banding patterns created groupings that generally agreed with the ploidy level, more so than geographic association. Due to the general trend of a south-north gradient of increasing ploidy level, and the sampling strategy employed, the relationship of genetic diversity to geographic region was unclear, although there was some support for both patterns. Other examinations of SRAP diversity in taxa with multiple ploidy levels have also found associations with fragment diversity and ploidy (Gulsen et al., 2009).

Celosia argentea L. is a cosmopolitan herb used in traditional Chinese medicine, while the closely allied C. cristata L. has been developed as an ornamental flowering plant. Due to a long history of both natural and artificial selection, and broad natural distribution, notable differentiation has occurred in Celosia L. populations on a geographic scale. Feng et al. (2009) examined 330 plants from 14 natural and two cultivated C. argentea populations as well as six cultivated varieties of C. cristata with SRAP markers. Between populations, diversity indices were high (Nei = 0.375; Shannon = 0.348) relative to other outcrossing annual species (Nybom and Bartish, 2000). Cluster analysis divided accessions into two primary groups by species. Within the C. argentea group, populations collected from geographically proximal regions clustered together, suggesting a relationship between genetic variation and geographic distribution. Additionally, the genetic distances of wild populations of C. argentea are greater relative to cultivated accessions, suggesting human selection and agricultural systems have selected only a fraction of the diversity occurring naturally in C. argentea.

Herbaceous taxa have dominated applications of published SRAP analyses, with only a small fraction investigating woody plant species. Of these, most examine insect-pollinated fruiting taxa, and few investigate wind-pollinated species. In a study of Pinus koraiensis Siebold & Zucc., Feng et al. (2009) used SRAP analysis to examine genetic diversity and gene flow in undisturbed Chinese populations of this conifer. Employing SRAP markers, seedlings derived from 24 provinces were characterized. Genetic diversity indices were low (Nei = 0.1274, Shannon = 0.1937), though predictable based on pollination system (Hamrick and Godt, 1996). Reciprocally, interpopulation similarity indices were very high (0.9590 to 0.9903), and AMOVA indicated that genetic variation primarily originated from intraprovenance differentiation (92.35%). These results, paired with high calculated levels of gene flow (Nm = 2.9), are congruent with other studies utilizing dominant markers in detecting extremely low variation and diversity between geographically distant populations of P. koraiensis (Potenko and Velikov, 1998; Kim et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2006). Other long-lived, temperate conifers have demonstrated similar levels of genetic identity (Latta and Mitton, 1997; Yeaman and Jarvis, 2006; Robledo-Arnuncio, 2011).

Conservation genetics

One critical application of molecular markers is to assess the genetic variation in the context of conservation (Karp et al., 1997). In most cases, anthropogenic impacts have led to the decline of taxa, whether through overharvesting, habitat destruction, or more recently, changes in climate. To develop an effective strategy to protect, promote, and maintain genetic diversity, it must first be quantified. For instances in which only limited protective measures are possible, it is essential to have this information to best direct conservation efforts (Petit et al., 1998). These genetic data provide relevant information for identifying units of conservation and illuminate the genetic processes that take place in the populations such as patterns of genetic flux, bottlenecks, and genetic drift.

Case studies

Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe is a Chinese epiphytic orchid that has been overharvested for medicinal uses (Hu, 1970), and is today very rare in the wild. Although endemic populations of many Dendrobium Sw. have been critically dwindling for decades (Siu, 2001; Chen et al., 2009), the vast majority of studies involving these taxa, including D. loddigesii, are related to commercially valuable, chemical isolates (M. F. Li et al., 1991; Zhang et al., 2003; Lu, 2006; Bai et al., 2007) and production (Zhang et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2010). To assess the genetic diversity in extant populations of D. loddigesii, Cai et al. (2011) collected tissues from 92 individuals across seven populations in southern China. Although the levels of SRAP polymorphism varied significantly between populations (27.71–68.83%), there was no correlation between molecular variation and geographic location. Analysis of molecular variance did suggest that there was genetic variation among populations (GST = 0.304), which is higher than the average outcrossing monocot (Hamrick and Godt, 1996) and member of the Orchidaceae (Forrest et al., 2004), but such diversity indices can vary widely between species.

A closely allied species, D. officinale Kimura & Migo, is a similarly imperiled Chinese endemic, suffering from overharvesting for anthropocentric purposes. Ding et al. (2008) collected 84 individuals from nine selected populations in southeastern China for SRAP analysis. Analysis of molecular variance also indicated that there was significantly higher variation within than between populations (72.95% vs. 27.05%), which is comparable to that reported by Ding et al. (2009) for ISSR (78.84%) and RAPD (78.88%) markers. The amount of variation (GST) among D. officinale populations was comparable to D. loddigesii (0.3484 vs. 0.304), which is not surprising as the taxa are closely related and maintain sympatric distribution and pollination strategies (Rong, 2008). Analysis of Nei’s genetic distance strongly supported two primary clusters, but Mantel’s test revealed that no significant correlation was detected between genetic and geographic distance. The strategies of pollination and seed dispersal of Dendrobium, and many orchids, often lead to this pattern of high levels of variation within and low levels between populations. Wind-mediated dispersal of propagules promotes outbreeding and gene flow between distant populations (Ridley, 1905) as seen in many species of Dendrobium (Arditti and Ghani, 2000), and such traits are associated with high levels of within-population genetic diversity relative to differentiation between populations (Hamrick and Godt, 1996).

Lycium ruthenicum Murray is an endangered species within the Solanaceae, threatened due to habitat depletion and overharvesting for use in traditional medicine (Chen et al., 2008). Liu et al. (2012) examined variation in 174 individuals collected from 14 wild populations in northwestern China using SRAP markers and five environmental variables. Results of AMOVA analysis and Nei’s gene diversity indicated that genetic variation was primarily found within populations (PhiST = 0.155; GST = 0.216). Correlations between genetic measures and ecogeographic variables showed positive relationships between altitude and annual number of sunshine hours with genetic diversity, but showed no relationship between latitude and longitude with genetic diversity. Diversity measures for L. ruthenicum were considerably higher when compared to the average of plants within the Solanaceae (Hamrick and Godt, 1996) and long-lived perennial woody plants (Hamrick et al., 1992). These high measures of population-level diversity were attributed to long lifespan and wind-mediated pollen dispersal.

Ecology

Numerous ecological applications for the SRAP marker system have been explored, although none have been pursued beyond the interests of crop development. For example, SRAP markers have been devoted to the identification of markers for pathogen resistance in agronomic crops (Liu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2010; Saha et al., 2010a, 2010b; Zhao et al., 2010; Devran et al., 2011), as well as variation in those pathogens (Baysal et al., 2009; Pasquali et al., 2010; Devran et al., 2011; Devran and Baysal, 2012; Irzykowska et al., 2012). Such studies suggest the value of SRAP applications in broader, ecological contexts, including description of the evolutionary interactions between microbes and their hosts. Similarly, employment of SRAP markers to distinguish between flower color (Fu et al., 2007; Han et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012) or fruit morphology (Yuan et al., 2008; S. Chen et al., 2010; Han et al., 2012) could be used in conjunction with data of preference or relative behavior of pollinators or seed-dispersing organisms. Some molecular information regarding onset or duration of flowering (Zhang et al., 2011) could be used in studies of pollinator interaction, as well as in analyses examining phenology, and potentially the selective effects of global climate change. Associations of SRAP markers and environmental adaptations have also been discovered, pairing specific banding patterns with increased cold tolerance (Castonguay et al., 2010) and other ecological factors, including seasonal temperature variation, annual rainfall variability, and humidity (Dong et al., 2010). Any and all of the underlying functional genes uncovered by SRAP analysis that control variation in morphology, phenology, or adaptability could also be applied to investigations of ecological niche modeling and, further, ecological speciation.

DISCUSSION

In the past few decades, dominant marker systems have become a standard tool for investigations of genetic variation in plant biology (for reviews, see Westman and Kresovich, 1997; Glaubitz and Moran, 2000; Nybom, 2001, 2004; Agarwal et al., 2008). The presumption that these markers are selectively neutral due to their amplification from random primers has been essential for their use in systematic investigations. Dominant markers have been used to describe population genetic statistics based on scoring amplicons as molecular phenotypes (presence/absence of bands) or genotypic (allelic frequencies) data. Issues arising from the latter approach involve the presumption of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in examined populations, including an outcrossing mating system, and nearly random mating, but such expectations are not appropriate for all studies. Some programs, such as Hickory (Holsinger et al., 2002), have been developed to estimate population-level statistics (e.g., FST) from dominant marker data using a Bayesian approach, and avoiding assumptions about HWE. This method does not yield precise estimates of inbreeding within populations, but does allow for the incorporation of the uncertainty about the degree of inbreeding into estimations of FST.

As dominant marker analyses have been described as a comparison of “molecular phenotypes” (sensu Zhivotovsky, 1999), we propose that use of SRAP markers should be viewed analogous to morphological character states, which have been widely used in the delimitation and assessment of variation within and between individuals. SRAP markers target coding regions of the genome (Li and Quiros, 2001) and therefore have potential beyond more commonly applied multilocus markers, possessing the capacity to elucidate markers with inherent biological significance (e.g., QTL identification). Hypotheses addressing ecological processes including niche adaptation and interspecific interaction could be addressed via SRAP, as well as investigations of taxonomic affinity and conservation genetics. Furthermore, this technique has been shown to robustly distinguish between taxa as well as, or better than, previously developed dominant marker techniques.

SRAP markers may also prove valuable when paired with the large-scale capability of next-generation techniques. Because distinct and polymorphic SRAP loci can be derived from use of a single forward primer with numerous, interchangeable reverse primers, a secondary set of labeled primers could be developed to use primary SRAP fragments with common end-sequences to develop enriched libraries in a secondary amplification step (W. Li et al., 2011). This would be comparable to the commonly used approach of enrichment from template derived from the same restriction enzyme (Cronn et al., 2012). Results from SRAP products in this manner may prove to be invaluable for discovery of polymorphism and development of novel variable loci (e.g., SNP, SSR, QTL) for investigations in plant biology.

Supplementary Material

LITERATURE CITED

- Agarwal M., Shrivastava N., Padh H. 2008. Advances in molecular marker techniques and their applications in plant sciences. Plant Cell Reports 27: 617–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal R. K., Brar D. S., Nandi S., Huang N., Khush G. S. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among Oryza species revealed by AFLP markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 98: 1320–1328 [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad R., Liow P., Spencer D., Jasieniuk M. 2008. Molecular evidence for a single genetic clone of invasive Arundo donax in the United States. Aquatic Botany 88: 113–120 [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi S., Al-Faifi S., Migdadi H., Khan M., El-Harty E., Ammar M. 2012. Molecular diversity assessment using sequence related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers in Vicia faba L. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13: 16457–16471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliscioni S. S., Giussani L. M., Zuloaga F. O., Kellogg E. A. 2003. A molecular phylogeny of Panicum (Poaceae: Paniceae): Tests of monophyly and phylogenetic placement within the Panicoideae. American Journal of Botany 90: 796–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwala S., Kimbeng C. A., Veremis J. C., Gravois K. A. 2008. Linkage mapping and genome analysis in a Saccharum interspecific cross using AFLP, SRAP and TRAP markers. Euphytica 164: 37–51 [Google Scholar]

- Amar M. H. 2012. Comparative analysis of SSR and SRAP sequence divergence in Citrus germplasm. Biotechnology 11: 20–28 [Google Scholar]

- Amar M. H., Biswas M. K., Zhang Z., Guo W. 2011. Exploitation of SSR, SRAP and CAPS-SNP markers for genetic diversity of Citrus germplasm collection. Scientia Horticulturae 128: 220–227 [Google Scholar]

- Aneja B., Yadav N. R., Chawla V., Yadav R. C. 2012. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) molecular marker system and its applications in crop improvement. Molecular Breeding 30: 1635–1648 [Google Scholar]

- Anthony F., Combes M. C., Astorga C., Bertrand B., Graziosi G., Lashermes P. 2002. The origin of cultivated Coffea arabica L. varieties revealed by AFLP and SSR markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 104: 894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aradhya M. K., Dangl G. S., Prins B. H., Boursiquot J. M., Walker M. A., Meredith C. P., Simon C. J. 2003. Genetic structure and differentiation in cultivated grape, Vitis vinifera L. Genetical Research 81: 179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti J., Ghani A. K. A. 2000. Tansley Review No. 110. Numerical and physical properties of orchid seeds and their biological implications. New Phytologist 145: 367–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif I. A., Bakir M. A., Khan H. A., Al Farhan A. H., Al Homaidan A. A., Bahkali A. H., Al Sadoon M., Shobrak M. 2010. A brief review of molecular techniques to assess plant diversity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11: 2079–2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M. L., Buckner C. M., Robinson J. J. 1991. Pollen-mediated introgression and hybrid speciation in Louisiana irises. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 88: 1398–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Garcia R., Lefort F., Andres M. T. D., Ibanez J., Borrego J., Jouve N., Vabello F., Martinez-Zapater J. M. 2002. Chloroplast microsatellite polymorphisms in Vitis species. Genome 45: 1142–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Wang W. Q., Bao Y. H. 2007. Comparative study on tissue structures and content of polysaccharides in stem of Dendrobium loddigesii. Beijing University Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 30: 196 [Google Scholar]

- Baker J. G. 1892. Scitamineae. In J. D. Hooker , The flora of British India (Vol. VI.), 198–257. Reeve & Co., London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley N. A., Roose M. L., Krueger R. R., Federici C. 2006. Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a Citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 112: 1519–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett H., Rhodes A. 1976. A numerical taxonomic study of affinity relationships in cultivated Citrus and its close relatives. Systematic Botany 1: 105–136 [Google Scholar]

- Baysal O., Siragusa M., Ikten H., Polat I., Gumrukcu E., Yigit F., Carimi F., Teixeira da Silva J. A. 2009. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici races and their genetic discrimination by molecular markers in West Mediterranean region of Turkey. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 74: 68–75 [Google Scholar]

- Bouton J. H. 2007. Molecular breeding of switchgrass for use as a biofuel crop. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 17: 553–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. F., Jeffery E. H., Juvik J. A. 2007. A polymerase chain reaction-based linkage map of broccoli and identification of quantitative trait loci associated with harvest date and head weight. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 132: 507–513 [Google Scholar]

- Budak H., Shearman R. C., Parmaksiz I., Gaussoin R. E., Riordan T. P., Dweikat I. 2004a. Molecular characterization of buffalograss germplasm using sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 108: 328–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budak H., Shearman R. C., Parmaksiz I., Dweikat I. 2004b. Comparative analysis of seeded and vegetative biotype buffalograsses based on phylogenetic relationship using ISSRs, SSRs, RAPDs, and SRAPs. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 109: 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtt B. L., Smith R. M. 1972. Tentative keys to the subfamilies, tribes and genera of Zingiberaceae. Notes from the Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh 31: 171–176 [Google Scholar]

- Caballero A., Quesada H., Rolan-Alvarez E. 2008. Impact of amplified fragment length polymorphism size homoplasy on the estimation of population genetic diversity and the detection of selective loci. Genetics 179: 539–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero A., Quesada H. 2010. Homoplasy and distribution of AFLP fragments: An analysis in silico of the genome of different species. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27: 1139–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Feng Z., Zhang X., Xu W., Hou B., Ding X. 2011. Genetic diversity and population structure of an endangered orchid (Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe) from China revealed by SRAP markers. Scientia Horticulturae 129: 877–881 [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay Y., Cloutier J., Bertrand A., Michaud R., Laberge S. 2010. SRAP polymorphisms associated with superior freezing tolerance in alfalfa (Medicago sativa spp. sativa). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 120: 1611–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. K., Pu L. K., Cao J. M., Ren X. 2008. Current research state and exploitation of Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Heilongjiang Agricultural Sciences 5: 155–157 [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Meng H., Chenga Z., Li Y., Shaanxi Y., Chai D. 2010. Identification of two SRAP markers linked to green skin color in cucumber. Acta Horticulturae 859: 351–356 [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zhang Y., Liu X., Chen B., Tu J., Tingdong F. 2007. Detection of QTL for six yield-related traits in oilseed rape (Brassica napus) using DH and immortalized F(2) populations. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 115: 849–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Q., Luo Y. B., Wood J. J. 2009. Dendrobium. In Z. Y. Wu, P. H. Raven, and D. Y. Hong [eds.], Flora of China, vol. 25 (Orchidaceae). Science Press, Beijing, China, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li G., Wang X. L. 2010. Genetic diversity of a germplasm collection of Cucumis melo L. using SRAP markers. Hereditas 32: 744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg M. T., Brown A. H. D., Whitfeld P. R. 1984. Chloroplast DNA diversity in wild and cultivated barley: Implications for genetic conservation. Genetical Research 43: 339–343 [Google Scholar]

- Comlekcioglu N., Simsek O., Boncuk M., Aka-Kacar Y. 2010. Genetic characterization of heat tolerant tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) genotypes by SRAP and RAPD markers. Genetics and Molecular Research 9: 2263–2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronn R., Knaus B. J., Liston A., Maughan P. J., Parks M., Syring J. V., Udall J. 2012. Targeted enrichment strategies for next-generation plant biology. American Journal of Botany 99: 291–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csurhes S., Hannan-Jones M.2008. Pest plant risk assessment: Kahili ginger Hedychium gardnerianum, White ginger Hedychium coronarium, Yellow ginger Hedychium flavescens. The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries Technical Report PR08-3682, The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Brisbane, Australia.

- Culley T. M., Wolfe A. D. 2001. Population genetic structure of the cleistogamous plant species Viola pubescens Aiton (Violaceae), as indicated by allozyme and ISSR molecular markers. Heredity 86: 545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devran Z., Baysal O. 2012. Genetic characterization of Meloidogyne incognita isolates from Turkey using sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP). Biologia 67: 535–539 [Google Scholar]

- Devran Z., Firat A. F., Tör M., Mutlu N., Elekçioğlu I. H. 2011. AFLP and SRAP markers linked to the mj gene for root-knot nematode resistance in cucumber. Scientia Agricola 68: 115–119 [Google Scholar]

- Ding G., Li X., Ding X., Qian L. 2009. Genetic diversity across natural populations of Dendrobium officinale, the endangered medicinal herb endemic to China, revealed by ISSR and RAPD markers. Russian Journal of Genetics 45: 327–334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding G., Zhang D., Ding X., Zhou Q., Zhang W., Li X. 2008. Genetic variation and conservation of the endangered Chinese endemic herb Dendrobium officinale based on SRAP analysis. Plant Systematics and Evolution 276: 149–156 [Google Scholar]

- Dong P., Wei Y. M., Chen G. Y., Li W., Wang J. R., Nevo E., Zheng Y. L. 2010. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) of wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) in Israel and its ecological association. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 38: 1–11 [Google Scholar]

- Doveri S., Lee D., Maheswaran M., Powell W. 2008. Molecular markers: History, features and applications. In C. Kole and A. G. Abbott [eds.], Principles and practices of plant genomics, 17–34. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA [Google Scholar]

- Duvick D. N. 1984. Genetic diversity in major farm crops on the farm and in reserve. Economic Botany 38: 161–178 [Google Scholar]

- Fan H. H., Li T. C., Qiu J., Lin Y., Cai Y. P. 2010. Comparison of SRAP and RAPD markers for genetic analysis of plants in Dendrobium Sw. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 41: 627–632 [Google Scholar]

- Fang D. Q., Roose M. L., Krueger R. R., Federici C. T. 1997. Fingerprinting trifoliate orange germplasm accessions with isozymes, RFLPs, and inter-simple sequence repeat markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 95: 211–219 [Google Scholar]

- Federici C. T., Fang D. Q., Scora R. W., Roose M. L. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships within the genus Citrus (Rutaceae) and related genera as revealed by RFLP and RAPD analysis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 96: 812–822 [Google Scholar]

- Feng F. J., Han S. J., Wang H. M. 2006. Genetic diversity and genetic differentiation of natural Pinus koraiensis population. Journal of Forest Research 17: 21–24 [Google Scholar]

- Feng N., Xue Q., Guo Q., Zhao R., Guo M. 2009. Genetic diversity and population structure of Celosia argentea and related species revealed by SRAP. Biochemical Genetics 47: 521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol M., Pico B., Nuez F. 2003. Genetic diversity of a germplasm collection of Cucurbita pepo using SRAP and AFLP markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 107: 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol M., Pico B., Nuez F. 2004a. Morphological and molecular diversity of a collection of Cucurbita maxima landraces. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 129: 60–69 [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol M., Pico B., Cordova P., Nuez F. 2004b. Molecular diversity of a germplasm collection of squash (Cucurbita moschata) determined by SRAP and AFLP markers. Crop Science 44: 653–664 [Google Scholar]

- Forrest A., Hollingsworth M., Hollingsworth P., Sydes C., Bateman R. 2004. Population genetic structure in European populations of Spirathes romanzoffiana set in the context of other genetic studies on orchids. Heredity 92: 218–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu F. Y., Liu L. Z., Chai Y. R., Chen L., Yang T., Jin M. Y., Zhang Z. S., Li J. N. 2007. Localization of QTLs for seed color using recombinant inbred lines of Brassica napus in different environments. Genome 50: 840–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk J. L. 2005. Hedychium gardnerianum invasion into Hawaiian montane rainforest: Interactions among litter quality, decomposition rate, and soil nitrogen availability. Biogeochemistry 76: 441–451 [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Liu N., Huang B., Hua X. 2008. Phylogenetic analysis and genetic mapping of Chinese Hedychium using SRAP markers. Scientia Horticulturae 117: 369–377 [Google Scholar]

- Glaubitz J. C., Moran G. F. 2000. Genetic tools: The use of biochemical and molecular markers. In A. Young, D. Boshier, and T. Boyle [eds.], Forest conservation genetics: Principles and practice, 39–59. CABI Publishing, New York, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gort G., Koopman W. J., Stein A. 2006. Fragment length distributions and collision probabilities for AFLP markers. Biometrics 62: 1107–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gort G., Van Hintum T., Van Eeuwijk F. 2009. Homoplasy corrected estimation of genetic similarity from AFLP bands, and the effect of the number of bands on the precision of estimation. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 119: 397–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J., McNicol R. J. 1995. An examination of the ability of RAPD markers to determine the relationships within and between Rubus species. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 90: 1128–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen O., Sever-Mutlu S., Mutlu N., Tuna M., Karaguzel O., Shearman R. C., Riordan T. P., Heng-Moss T. M. 2009. Polyploidy creates higher diversity among Cynodon accessions as assessed by molecular markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 118: 1309–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Zhang J., Liu C., Zhang G., Li M., Zhang Q. 2012. Genetic variability and relationships between and within grape cultivated varieties and wild species based on SRAP markers. Tree Genetics & Genomes 8: 789–800 [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Liu X., Liu X., Yang Z., Kong D., He Y., Feng Z. 2012. Construction of genetic map in barley using sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers, a new molecular marker technique. African Journal of Biotechnology 11: 13858–13862 [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Wang X., Yu X., Sun X., Zhou T. 2011. Molecular identification and genetic variation of 13 herbaceous peony cultivars using SRAP markers. Acta Horticulturae 918: 333–340 [Google Scholar]

- Halda J. J., Waddick J. W. 2004. The genus Paeonia. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, USA [Google Scholar]

- Hale A. L., Farnham M. W., Menz M. A. 2006. Use of PCR-based markers for differentiating elite broccoli inbreds. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 131: 418–423 [Google Scholar]

- Hale A. L., Farnham M. W., Nzaramba M. N., Kimbeng C. A. 2007. Heterosis for horticultural traits in broccoli. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 115: 351–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick J., Godt M., Sherman-Broyles S. L. 1992. Factors influencing levels of genetic diversity in woody plant species. In W. T. Adams , Population genetics of forest trees, 95–124. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick J., Godt M. 1996. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 351: 1291–1298 [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Liu G., Chang R., Zhang X. 2012. The sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers linked to the color around the stone (Cs) locus of peach fruit. African Journal of Biotechnology 11: 9911–9914 [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Wang L., Liu Z. A., Jan D. R., Shu Q. 2008. Characterization of sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers analysis of tree peony bud sports. Scientia Horticulturae 115: 261–267 [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q., Liu Z. A., Shu Q. Y., Zhang R. E., De Rick J., Wang L. S. 2008. Studies on Paeonia cultivars and hybrids identification based on SRAP analysis. Hereditas 145: 38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haw S. G. 2001. Tree peonies: A review of their history and taxonomy. New Plantsman 8: 156–171 [Google Scholar]

- He F. F., Yang Z. P., Zhang Z. S., Wang G. X., Wang J. C. 2007. Genetic diversity analysis of potato germplasm by SRAP markers. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology 15: 1001–1005 [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger K. E., Lewis P. O., Dey D. K. 2002. A Bayesian approach to inferring population structure from dominant markers. Molecular Ecology 11: 1157–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D. 2010. Peonies of the world: Taxonomy and phytogeography. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- Horita M., Morohashi H., Komai F. 2003. Production of fertile somatic hybrid plants between Oriental hybrid lily and Lilium formolongi. Planta 217: 597–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. Y. 1970. Dendrobium in Chinese medicine. Economic Botany 24: 165–174 [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Andersen S., Dixelius C., Hansen L. 2002. Production of fertile intergeneric somatic hybrids between Brassica napus and Sinapis arvensis for the enrichment of the rapeseed gene pool. Plant Cell Reports 21: 147–152 [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Li S. X., Cai G. X., Yue C. H., Wei L. J., Zhang P. 2008. Molecular authentication and quality control using a high performance liquid chromatography technique of fructus Evodiae. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 31: 312–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. K., Bughrara S. S., Zhang X. Q., Bales-Arcelo C. J., Bin X. 2011. Genetic diversity of switchgrass and its relative species in Panicum genus using molecular markers. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 39: 685–693 [Google Scholar]

- Inomata N. 2006. Brassica vegetable crops. In R. J. Singh , Genetic resources, chromosome engineering, and crop improvement, vol. 3, Vegetable crops, 115–146. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ipek M., Ipek A., Simon P. W. 2006. Sequence homology of polymorphic AFLP markers in garlic (Allium sativum L.). Genome 49: 1246–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irzykowska L., Weber Z., Bocianowski J. 2012. Comparison of Claviceps purpurea populations originated from experimental plots or fields of rye. Central European Journal of Biology 7: 839–849 [Google Scholar]

- Isk N., Doganlar S., Frary A. 2011. Genetic diversity of Turkish olive varieties assessed by simple sequence repeat and sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers. Crop Science 51: 1646–1654 [Google Scholar]

- Jones C., Edwards K., Castaglione S., Winfield M., Sala F., Van Dewiel C., Bredemeijer G., et al. 1997. Reproducibility testing of RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers in plants by a network of European laboratories. Molecular Breeding 3: 381–390 [Google Scholar]

- Kantety R. V., Rota M. L., Matthews D. E., Sorrells M. E. 2002. Data mining for simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags from barley, maize, rice, sorghum and wheat. Plant Molecular Biology 48: 501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp A., Kresovich S., Bhat K. V., Ayad W. G., Hodgkin T. 1997. Molecular tools in plant genetic resources conservation: A guide to the technologies (No. 2). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy. Website http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACB166.pdf [accessed 30 June 2014].

- Kim Z. S., Hwang J. W., Lee S. W., Yang C., Gorovoy P. G. 2005. Genetic variation of Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis Sieb. & Zucc.) at allozyme and RAPD markers in Korea, China and Russia. Silvae Genetica 54: 235–245 [Google Scholar]

- Klein A.-M., Steffan-Dewenter I., Tscharntke T. 2003. Fruit set of highland coffee increases with the diversity of pollinating bees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 270: 955–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman W. J. 2005. Phylogenetic signal in AFLP data sets. Systematic Biology 54: 197–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman W. J., Wissemann V., De Cock K., Van Huylenbroeck J., De Riek J., Sabatino G. J., Visser D., et al. 2008. AFLP markers as a tool to reconstruct complex relationships: A case study in Rosa (Rosaceae). American Journal of Botany 95: 353–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. A., Sudisha J., Sreenath H. L. 2008. Genetic relation of Coffea and Indian Psilanthus species as revealed through RAPD and ISSR markers. International Journal of Integrative Biology 3: 150–158 [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi M., Senthilkumar P., Parani M., Jithesh M. N., Parida A. K. 2000. PCR-RFLP analysis of chloroplast gene regions in Cajanus (Leguminosae) and allied genera. Euphytica 116: 243–250 [Google Scholar]

- Lashermes P., Andrzejewski S., Bertrand B., Combes M. C., Dussert S., Graziosi G., Trouslot P., Anthony F. 2000. Molecular analysis of introgressive breeding in coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 100: 139–146 [Google Scholar]

- Lashermes P., Trouslot P., Anthony F., Combes M. C., Charrier A. 1996. Genetic diversity for RAPD markers between cultivated and wild accessions of Coffea arabica. Euphytica 87: 59–64 [Google Scholar]

- Latta R., Mitton J. 1997. A comparison of population differentiation across four classes of gene marker in limber pine (Finus flexilis James). Genetics 146: 1153–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi A., Thomas C. E. 2007. DNA markers from different linkage regions of watermelon genome useful in differentiating among closely related watermelon genotypes. HortScience 42: 210–214 [Google Scholar]

- Levi A., Wechter P., Massey L., Carter L., Hopkins D. 2011. An extended genetic linkage map for watermelon based on a testcross and a BC2F2 population. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2: 93–110 [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Quiros C. F. 2001. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: Its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 103: 455–461 [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Ruan C., Teixeira da Silva J., Liu B. 2010. Associations of SRAP markers with dried-shrink disease resistance in a germplasm collection of sea buckthorn (Hippophae L.). Genome 53: 447–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. F., Hirata Y., Xu G. J., Niwa M., Wu H. M. 1991. Studies on the chemical constituents of Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 26: 307–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Zhang J., Mou J., Geng J., McVetty P., Hu S., Li G. 2011. Integration of Solexa sequences on an ultradense genetic map in Brassica rapa L. BMC Genomics 12: 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Y., Shen J. X., Wang T. H., Fu T. D., Ma C. Z. 2007. Construction of a linkage map using SRAP, SSR and AFLP markers in Brassica napus L. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 40: 1118–1126 [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu Z., Wang Y., Yang N., Xin X., Yang S., Feng H. 2012. Identification of quantitative trait loci for yellow inner leaves in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) based on SSR and SRAP markers. Scientia Horticulturae 133: 10–17 [Google Scholar]

- Liang C.2011. Genetic diversity analysis and suitability evaluation and regionalization of Euodia rutaecarpa. Masters thesis, Hunan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Changsha, Hunan, China.

- Liang G., Xiong G., Guo Q., He Q., Li X. 2007. AFLP analysis and the taxonomy of Citrus. Acta Horticulturae 760: 137–142 [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Teng J. B., Lao W. R. 2010. Determination of polysaccharides in Dendrobium loddigesii from different cultivation and growth time. West China Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1: 27–29 [Google Scholar]

- Lim K. B., Ramanna M., Jacobsen E., Van Tuyl J. 2003. Evaluation of BC2 progenies derived from 3.-2. and 3.-4. crosses of Lilium hybrids: A GISH analysis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 106: 568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Zhang X., Nie Y., He D., Wu M. 2003. Construction of a genetic linkage map for cotton based on SRAP. Chinese Science Bulletin 48: 2064–2068 [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Guo X. 2009. A high-density integrative linkage map for Gossypium hirsutum. Euphytica 166: 35–45 [Google Scholar]

- Lira-Saade R. 1995. Estudios taxonómicos y ecogeográficos de las Cucurbitaceae Latinoamericanas de importancia económica. Systematic and Ecogeographic Studies on Crop Genepools, No. 9. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Ma X., Wei J., Qin J., Mo C. 2010. The first genetic linkage map of Luohanguo (Siraitia grosvenorii) based on ISSR and SRAP markers. Genome 54: 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhu X., Gong Y., Song X., Wang T., Zhao L., Wang L. 2007a. Genetic giversity analysis of radish germplasm with RAPD, AFLP and SRAP markers. Acta Horticulturae 760: 125–130 [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Liu G., Gong Y. 2007b. Evaluation of genetic purity of F1 hybrid seeds in cabbage with RAPD, ISSR, SRAP, and SSR markers. HortScience 42: 724–727 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yan H., Yang W., Li X., Li Y., Meng Q., Zhang L., et al. 2008. Molecular diversity of 23 wheat leaf rust resistance near-isogenic lines determined by sequence-related amplified polymorphism. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 41: 1333–1340 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Shu Q., Wang L., Yu M., Hu Y., Zhang H., Tao Y., Shao Y. 2012. Genetic diversity of the endangered and medically important Lycium ruthenicum Murr. revealed by sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 45: 86–97 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Liu Y., Liu S., Ding X., Yang Y. 2009. Analysis of the sequence of ITS1-5.8 S-ITS2 regions of the three species of fructus Evodiae in Guizhou Province of China and identification of main ingredients of their medicinal chemistry. Journal of Computer Science & Systems Biology 2: 200–207 [Google Scholar]

- Loh J. P., Kiew R., Hay A., Kee A., Gan L. H., Gan Y. 2000. Intergeneric and interspecific relationships in Araceae tribe Caladieae and development of molecular markers using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP). Annals of Botany 85: 371–378 [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y., Lin X., He Q., Guo X., Huang L., Fang W. 2010. Analysis on genetic relationship of Puji-bamboo species by AFLP and SRAP. Molecular Plant Breeding 8: 83–88 [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. Y. 2006. Compared analysis of total alkaloids and polysaccharides in tubing shoot and wild plant of Dendrobium loddigesii. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 34: 1606–1607 [Google Scholar]

- Mallet J. 2007. Hybrid speciation. Nature 446: 279–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon G. E., Vaillancourt R. E., Steane D. A., Potts B. M. 2008. An AFLP marker approach to lower-level systematics in Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae). American Journal of Botany 95: 368–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., Kszos L. A. 2005. Development of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) as a bioenergy feedstock in the United States. Biomass and Bioenergy 28: 515–535 [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., Bouton J., Bransby D., Conger B., Ocumpaugh W., Parrish D., Taliaferro C., et al. 1999. Developing switchgrass as a bioenergy crop. In J. Janick , Perspectives on new crops and new uses, 282–299. ASHS Press, Alexandria, Virginia, USA. [Google Scholar]