Abstract

Background

Esophagectomy is a complex operation and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In an attempt to lower morbidity, we have adopted a minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to evaluate the outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) in a large group of patients. Our secondary objective was to compare the modified McKeown minimally invasive approach (videothoracoscopic surgery, laparoscopy, neck anastomosis [MIE-neck]) with our current approach, a modified Ivor Lewis approach (laparoscopy, videothoracoscopic surgery, chest anastomosis [MIE-chest]).

Methods

We reviewed 1033 consecutive patients undergoing MIE. Elective operation was performed on 1011 patients; 22 patients with nonelective operations were excluded. Patients were stratified by surgical approach and perioperative outcomes analyzed. The primary endpoint studied was 30-day mortality.

Results

The MIE-neck was performed in 481 (48%) and MIE-Ivor Lewis in 530 (52%). Patients undergoing MIE-Ivor Lewis were operated in the current era. The median number of lymph nodes resected was 21. The operative mortality was 1.68%. Median length of stay (8 days) and ICU stay (2 days) were similar between the 2 approaches. Mortality rate was 0.9%, and recurrent nerve injury was less frequent in the Ivor Lewis MIE group (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

MIE in our center resulted in acceptable lymph node resection, postoperative outcomes, and low mortality using either an MIE-neck or an MIE-chest approach. The MIE Ivor Lewis approach was associated with reduced recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and mortality of 0.9% and is now our preferred approach. Minimally invasive esophagectomy can be performed safely, with good results in an experienced center.

The incidence of esophageal cancer has been increasing over the past 3 decades.1,2 In the United States and the western world, this profound increase has been due to an increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. This major epidemiologic shift is thought to be related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, and Barrett’s esophagus, the dominant risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma.1, 2

Outcomes after diagnosis of esophageal cancer are suboptimal, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 25%, although an improvement in survival, associated with early-stage disease, was seen in recent surgical series.1–3 Esophagectomy is a primary curative modality for localized esophageal cancer. However, esophagectomy is a complex operation and the mortality of esophageal resection has been significant. Birkmeyer and colleagues4 reported that the mortality of esophagectomy ranged from 8% to 23% in the United States and depended on the hospital volume. The morbidity associated with esophagectomy has raised concerns about the procedure and referral for esophagectomy. This is becoming increasingly important with an emerging interest in nonsurgical options for early-stage disease, such as endomucosal resection, endoscopic ablative strategies such as photodynamic therapy, and for more advanced disease, definitive chemoradiation.3 Frequently, due consideration for surgical resection may not be given because of concerns with regard to the morbidity of open esophagectomy. If we can safely accomplish esophageal resection with a less-invasive approach, this could provide an effective treatment modality—esophagectomy with lesser morbidity for both early-stage disease and for patients with more locally advanced stages, who might be candidates for a lower morbidity resection option. In an effort to decrease the morbidity associated with esophagectomy, we and others have adopted a minimally invasive approach to esophageal resection.5–8

Over the last 2 decades, minimally invasive approaches have been described for the performance of several surgical procedures for the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases.9–12 With the introduction of laparoscopic fundoplication by Dallemagne and coworkers13 in 1991, several esophageal diseases, such as achalasia, paraesophageal hernias, and redo antireflux surgery, have been treated with minimally invasive approaches.9–11,13 A minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy was originally described by Cuschieri et al14 and DePaula et al.15 Since then, MIE has been performed with increasing frequency.5–8,16,17 We had originally adopted a modified McKeown 3-incision MIE and more recently transitioned to a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis approach.5,7

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the outcomes after MIE with a focus on perioperative outcomes in a large group of patients. Our secondary objective was to do a preliminary comparison of the results between the modified McKeown MIE and our current approach, a modified Ivor Lewis MIE.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

All patients undergoing planned MIE at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from August 1, 1996, to March 31, 2011, were reviewed (n = 1033), and patients undergoing nonelective operations (n = 22) were excluded. Patients undergoing a planned hybrid procedure (ie, planned thoracotomy with laparoscopy [n = 79] or planned laparotomy with videothoracoscopic surgery [VATS] [n = 21]) were excluded. Patients undergoing esophagectomy as a component of pharyngolaryngectomy were excluded (n = 2). Patients (n = 1011) were stratified into 2 groups on the basis of the approach and location of the anastomosis (McKeown type 3-incision [MIE-neck], n = 481; Ivor Lewis MIE [MIE-chest], n = 530). This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board.

Operative Approach

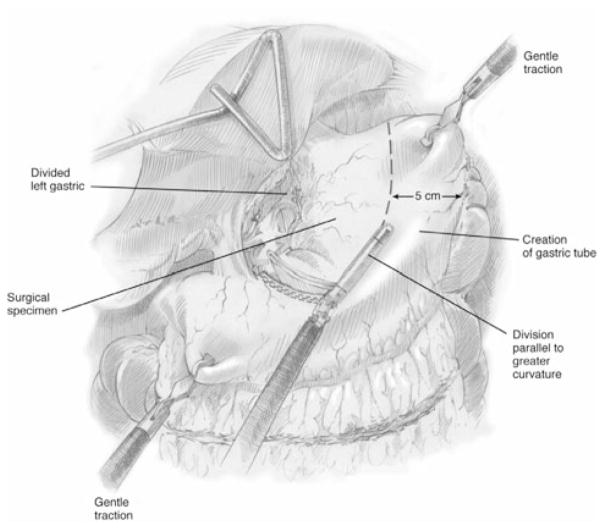

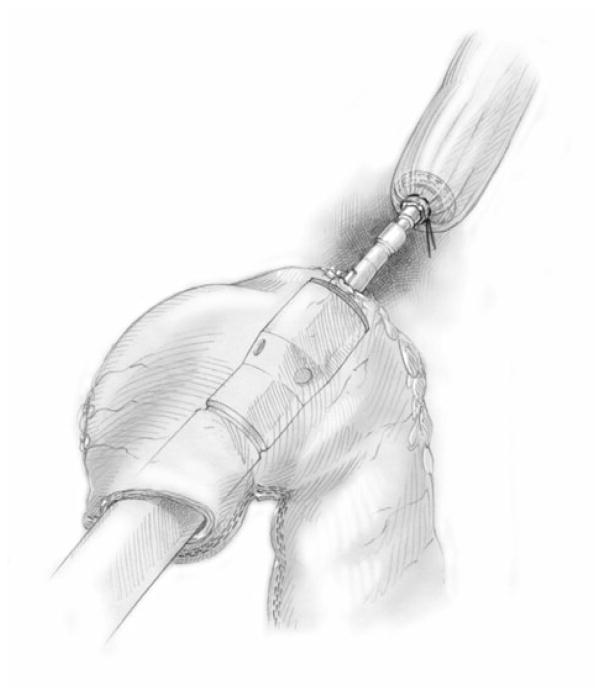

Our approach to MIE has been refined over the study time period and both techniques have been described in detail elsewhere.5,7 Briefly, we defined modifications of the McKeown approach as MIE-neck, consisting of either (1) laparoscopic esophagectomy with gastric-pull through and cervical anastomosis (n = 19) or (2) thoracoscopic esophageal mobilization and intrathoracic lymphadenectomy followed by laparoscopic gastric mobilization and formation of the gastric conduit (Fig. 1), lymph node dissection, and cervical anastomosis. In most cases, a staging laparoscopy was performed in the same setting or as a separate procedure to ensure resectability. We defined modifications of the Ivor Lewis technique as MIE-chest, consisting of laparoscopic gastric mobilization and formation of a gastric conduit (Fig. 1) and lymph node dissection, followed by thoracoscopic esophageal mobilization and intrathoracic lymphadenectomy. An intrathoracic anastomosis was performed thoracoscopically through a non–rib-spreading, mini–access incision (4 to 5 cm), typically using an end-to-end anastomotic (EEA) stapler (Fig. 2). Most of the patients also had placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube (>95%) and a pyloric drainage procedure (>85%).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of construction of the gastric conduit. Reproduced with permission from the UPMC Heart, Lung and Esophageal Surgery Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the construction of minimally invasive Ivor Lewis anastomosis. Reproduced with permission from the UPMC Heart, Lung and Esophageal Surgery Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA.

Esophagectomy Outcomes

Retrospective chart review was performed using a standardized outcome protocol and data were entered into a surgical outcomes database. Patient demographics, preoperative symptoms, laboratory and radiographic studies, operative details, and tumor-specific variables were recorded. Staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition criteria.18 Surgical outcomes were abstracted, including postoperative length of stay, postoperative morbidity, and operative mortality. The primary endpoint of the study was operative (total 30-day) mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were summarized with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median with interquartile range for continuous variables for the entire cohort and then stratified by MIE approach (MIE-neck vs MIE-chest). Chi-Square, Fischer exact, and Student t tests, accounting for unequal variance, were used to describe differences between groups. Survival after MIE was estimated by pathologic stage using the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA SE 10.0 Corp software.19

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Comorbid Conditions

The majority of patients were older than 55 years (75%), male (80%), white (97%), and had malignant disease as the indication for esophagectomy (960/1011, 95%). These demographic characteristics were similar between the 2 operative approaches (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Esophagectomy: Comparing MIE-McKeown and MIE-Ivor Lewis

| Preoperative Patient Characteristics | MIE-Neck, n = 481 (48%) | MIE-Chest, n = 530 (52%) | Total, n = 1011 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (56–72) | 64 (56–72) | 64 (56–72) | 0.450 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 392 (82) | 415 (78) | 807 (80) | 0.210 |

| Race, white, n (%) | 470 (98) | 506 (96) | 976 (97) | 0.052 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28 (25–32) | 28 (25–33) | 28 (25–32) | 0.070 |

| BMI < 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 310 (65) | 321 (61) | 631 (63) | 0.144 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 165 (35) | 207 (39) | 372 (37) | |

| Pretreatment weight loss, n (%) | 200 (44) | 207 (40) | 407 (42) | 0.258 |

| Albumin, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 3.9 (3.7–4.2) | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 0.207 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 13.3 (12.1–14.5) | 13.3 (11.7–14.6) | 13.3 (11.9–14.5) | 0.210 |

| History of tobacco use, n (%) | 365 (77) | 368 (70) | 733 (73) | 0.017 |

| Pack-years, median (IQR) | 40 (20–60) | 30 (20–50) | 33.5 (20–50) | 0.016 |

| Quit >12 months before diagnosis, n (%) | 210 (69) | 226 (66) | 436 (67) | 0.453 |

| Prior gastric or esophageal surgery | 51 (11) | 60 (11) | 111 (11) | 0.715 |

| Previous anti-reflux surgery, n (%) | 23 (5) | 37 (7) | 60 (6) | 0.142 |

| Previous chest surgery, n (%) | 43 (9) | 70 (13) | 113 (11) | 0.030 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Malignant disease, n (%) | 462 (96) | 498 (94) | 960 (95) | 0.130 |

| Age-adjusted, CCI > 3 | 237 (49) | 254 (48) | 491 (49) | 0.690 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 110 (23) | 121 (23) | 231 (23) | 0.999 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 92 (19) | 102 (19) | 194 (19) | 0.950 |

| History of gastroesophageal reflux disease | 335 (71) | 375 (72) | 710 (71) | 0.760 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 46 (10) | 38 (7) | 84 (8) | 0.171 |

| COPD/emphysema, n (%) | 49 (10) | 75 (14) | 124 (12) | 0.054 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency, baseline Cr > 2 mg/dL or HD, n (%) | 12 (3) | 14 (3) | 26 (3) | 0.879 |

| Prior therapy for cancer or Barrett’s esophagusa | ||||

| Use of induction therapy, n(%) | 146 (32) | 151 (30) | 297 (31) | 0.668 |

| Preoperative endoscopic interventions, n (%) | ||||

| Esophageal stent | 14 (3) | 15 (3) | 29 (3) | 0.967 |

| Photodynamic therapy | 28 (6) | 9 (2) | 37 (4) | 0.001 |

| Esophageal dilation | 107 (23) | 65 (13) | 172 (18) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative gastrostomy tube | 8 (2) | 9 (2) | 17 (2) | 0.941 |

| Preoperative feeding jejunostomy tube | 8 (2) | 22 (4) | 30 (3) | 0.018 |

Includes only patients with malignant disease (n = 960).

BMI indicates body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range; Cr, creatinine; HD, hemodialysis

Dysphagia was the most common indication for endoscopic evaluation in patients undergoing esophagectomy for malignant disease (n = 480, 51%). Another 26% of patients (n = 245) were diagnosed after being referred for screening endoscopy for long-standing or medically recalcitrant gastroesophageal reflux disease or during subsequent surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus. The remaining patients presented with occult or overt bleeding, odynophagia, epigastric pain, or as incidental findings while being evaluated for other purposes. Induction chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy was administered in 31% of patients with malignant disease.

Technical Details of MIE and Changes in Approach Over Time

The primary approach we originally used was a 3-incision McKeown MIE, and we began to use the Ivor Lewis MIE approach more frequently in 2005. By 2006, the Ivor Lewis MIE became our preferred approach. The location of the esophagogastric anastomosis is the primary difference between the 2 approaches to MIE (Table 2). Hand-sewn anastomosis was performed in 21% of the MIE-neck group (n = 106) and 1% of the MIE-chest group. Stapled anastomosis, with either an EEA or a gastrointestinal anastomosis stapler, was the preferred approach in the neck group. An EEA stapler was used almost exclusively (99%) in the Ivor Lewis MIE group (P < 0.001) and the size of the EEA stapler used was most commonly a 28-mm EEA. A 25-mm EEA stapler was used significantly less frequently (P < 0.001). The gastric conduit was placed in the esophageal bed in almost all patients. In 6 patients with squamous cell tumors that were abutting the aorta or the airway, the gastric conduit was placed substernally to facilitate postoperative radiation to the tumor bed; anastomosis was performed in the neck in these patients.

TABLE 2.

Technical and Perioperative Aspects of Elective MIE With Either a Cervical (MIE-Neck) or Intrathoracic (MIE-Chest) Anastomosis

| MIE-Neck, n = 481 (48%) | MIE-Chest, n = 530 (52%) | Total, n = 1011 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric conduit, n (%) | 480 (99.8) | 530 (100) | 1010 (99.9) | 0.294 |

| Pyloric drainage procedure, n (%) | 410 (86) | 459 (87) | 869 (86) | 0.59 |

| Feeding jejunostomy, n (%) | 454 (95) | 498 (95) | 952 (95) | 0.829 |

| Stapled anastomosis, n (%) | 375 (79) | 526 (99) | 901 (89) | <0.001 |

| Conversion to open, n (%) | 25 (5) | 20 (4) | 45 (5) | 0.272 |

| Abdomen | 13 (3) | 7 (1) | 20 (2) | 0.528 |

| Chest | 9 (2) | 13 (3) | 22 (2) | 0.115 |

| Both | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | 0.069 |

| Postoperative length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 8 (6–14) | 7 (6–14) | 8 (6–14) | 0.069 |

| ICU length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.877 |

The frequency of conversion to an open operation remained stable with either approach over the period of study (45/1011, 4.5%). The most common reasons to electively convert the thoracoscopic portion of the procedure to an open approach were adhesions (n = 4), persistent bleeding (n = 6), and tumor bulkiness/adherence or a need to better assess the tumor margins (n = 8). Similarly, the most common reasons for conversion of the laparoscopic portion of the procedure to an open approach were adhesions (n = 10), inadequate conduit length/need for more mobilization (n = 2), and tumor bulkiness/adherence or a need to better assess the tumor margins (n = 5). The rate of conversion was similar between the 2 groups (P = 0.27). Emergent open conversion for bleeding occurred rarely.

Postoperative Adverse Events

There were no intraoperative mortalities. The total 30-day (both in-hospital and out-of-hospital) operative mortality was 1.68% (17/1011). This was lower in the Ivor Lewis MIE group at 0.9% (5/530) but did not reach statistical significance when compared with the McKeown-type MIE-neck group (2.5%, 12/481) (Table 3). Of the 17 deaths within 30 days, 16 occurred in-hospital before discharge. There was one patient who was discharged after esophagectomy, and death occurred after discharge but within 30 days. There were 11 additional deaths that occurred in-hospital beyond 30 days; the combined total 30-day and in-hospital mortality for the entire cohort was 2.8% (28/1011) (1.7% in the MIE-Ivor Lewis group and 3.95% in the MIE-neck group).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Postoperative Adverse Outcomes After Elective MIE With Either a Cervical (MIE-Neck) or Intrathoracic (MIE-Chest) Anastomosis

| MIE-Neck, n = 481 (48%) | MIE-Chest, n = 530 (52%) | Total, n = 1011 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major morbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Vocal fold paresis/paralysis | 37 (8) | 5 (1) | 42 (4) | <0.001 |

| Empyema | 31 (6) | 28 (5) | 59 (6) | 0.431 |

| ARDS | 18 (4) | 8 (2) | 26 (3) | 0.026 |

| Myocardial infarction | 9 (2) | 11 (2) | 20 (2) | 0.809 |

| Congestive heart failure | 20 (4) | 10 (2) | 30 (3) | 0.033 |

| Anastomotic leak requiring surgery | 26 (5) | 23 (4) | 49 (5) | 0.439 |

| Gastric tube necrosis | 15 (3) | 9 (2) | 24 (2) | 0.140 |

| Mortality at 30 days, n (%) | 12 (2.5) | 5 (0.9) | 17 (1.7) | 0.083 |

ARDS indicates acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Major unanticipated intraoperative events, including bleeding (1%), need for splenectomy (0.2%), and myocardial infarction (1%), did not differ significantly between groups. The morbidity is summarized in Table 3. The overall incidence of postoperative adverse events did not differ between the groups. However, the Ivor Lewis MIE group was significantly less likely to experience vocal cord paresis/paralysis (1%) (P < 0.001).

Pathologic Findings and Adequacy of Cancer Resection

Adenocarcinoma and nodal metastasis were present significantly more frequently in the Ivor Lewis MIE patients (P < 0.05). The R0 resection rate was 98%, with negative margins on final pathologic review. The median number of lymph nodes resected was 21 and was slightly higher in the MIE-chest group; this may be due to better lymph node dissection with increasing surgeon experience. These are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Pathologic Findings After Elective MIE With Either a Cervical (MIE-Neck) or Intrathoracic (MIE-Chest) Anastomosis

| Tumor Specific Variables, if Malignant Disease | MIE-Neck, n = 462 (48%) | MIE-Chest, n = 498 (52%) | Total, n = 960 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor location, n (%) | ||||

| Proximal or middle esophagus | 44 (10) | 16 (3) | 60 (7) | <0.001 |

| Distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction | 379 (90) | 470 (97) | 849 (93) | |

| Clinical stage before initial therapy (if malignant), n (%) | ||||

| Stage 0 | 71 (18) | 24 (7) | 95 (13) | <0.001 |

| Stage I | 65 (16) | 70 (20) | 135 (18) | |

| Stage IIa | 57 (14) | 75 (21) | 132 (17) | |

| Stage IIb | 67 (17) | 40 (11) | 107 (14) | |

| Stage III | 113 (29) | 127 (35) | 240 (32) | |

| Stage IV | 24 (6) | 24 (7) | 48 (6) | |

| Squamous tumor type, n (%) | 61 (13) | 44 (9) | 105 (11) | 0.030 |

| Adenocarcinoma tumor type, n (%) | 316 (68) | 411 (83) | 727 (76) | <0.001 |

| Tumor invasion at esophagectomy, T3 or T4, n (%) | 180 (39) | 221 (45) | 401 (42) | 0.067 |

| Nodal metastasis at esophagectomy, n (%) | 178 (39) | 239 (49) | 417 (44) | 0.003 |

| Adequacy of cancer resection | ||||

| Negative margins, n (%) | 453 (98) | 486 (98) | 939 (98) | 0.623 |

| Number of lymph nodes examined, median (IQR) | 19 (13–26) | 23.5 (17–31) | 21 (15–29) | <0.001 |

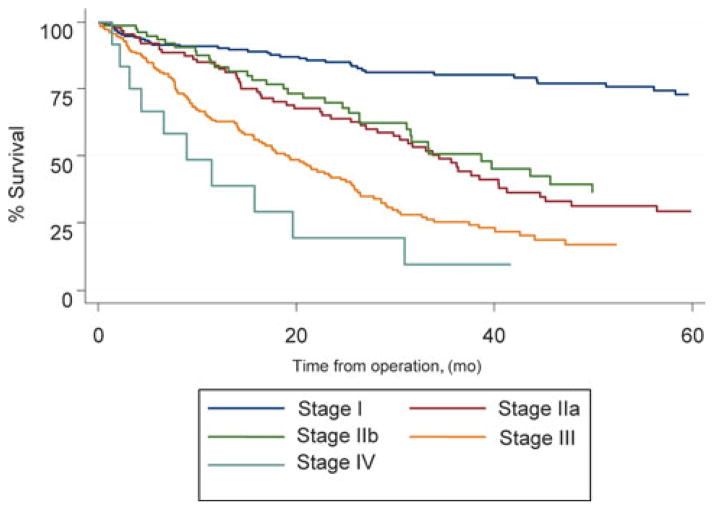

The median follow-up was 20 months. The overall survival rate at 1 year stratified by pathologic stage at esophagectomy was 86% (stage 0), 89% (stage 1), 80% (stage IIa), 76% (stage IIb), 63% (stage III), and 44% (stage IV). Overall survival for cancer patients treated with MIE without induction therapy is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of the estimated overall survival of patients who did not receive induction therapy, stratified by stage.

DISCUSSION

This study of 1011 patients who underwent MIE represents the largest series to date. This experience has demonstrated that MIE can be performed safely with an overall operative mortality of 1.68%, a median ICU stay of 2 days, and a median hospital stay of 8 days. The morbidity of the procedure was acceptable and similar to or better than most published series of open esophagectomy. In our preliminary comparison of outcomes between the MIE-neck and MIE-chest groups, median length of ICU and hospital stay, overall morbidity, and operative mortality seemed to be similar between the 2 approaches. The 30-day mortality was 0.9% in the MIE Ivor Lewis group and 2.5% in the MIE-Neck group. The incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury was significantly lower in the Ivor Lewis MIE-chest group (1%) than in the MIE-Neck group (P < 0.001).

Approaches to Esophagectomy

The optimal approach to esophagectomy, regardless of whether the resection is performed in an open fashion or with minimally invasive techniques, is controversial. The classical open approaches for esophageal resection include a transhiatal resection and transthoracic approaches, such as Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, “3 incision” McKeown-type esophagectomy, and resection with a left thoracotomy or left thoracoabdominal approach.20–26 Each approach has advantages, and there are very few randomized studies comparing these approaches. A large randomized study of 220 patients comparing transthoracic esophagectomy (TTE) and transhiatal esophagectomy (THE) was reported by Hulscher and colleagues.27 Patients who underwent THE had a shorter duration of surgery, less blood loss, and less morbidity; however, there were no differences in perioperative mortality. Significantly, more lymph nodes were resected in patients who underwent TTE. There was a trend toward an improved 5-year disease-free survival and overall survival in the TTE group, although this did not reach statistical significance. On longer follow-up, patients with limited nodal metastases seem to have a survival benefit. Although the open transthoracic approach showed a trend toward better survival, and better lymphadenectomy, there was an increase in morbidity with this approach in comparison with THE.

The extent of lymph node dissection required for patients with esophageal cancer also remains controversial.28–30 However, adequate lymph node sampling is required for accurate staging.29 One of the potential advantages of the transthoracic approach is better exposure and improved lymph node dissection in the mediastinum. In our current series, the median number of lymph nodes that were removed was 21, which is comparable with other open series. Similarly, the rate of complete resection with negative margins in 98% of patients in the current series is comparable with other open series of esophagectomy. However, long-term oncologic efficacy of MIE needs to be evaluated. We currently prefer an Ivor Lewis MIE with a 2-field approach for the lymph node dissection for the treatment of esophageal cancer.

In terms of optimal location for the anastomosis, the potential benefits of a cervical anastomosis are a more proximal resection margin and the potentially lower morbidity associated with a cervical anastomotic leak. An intrathoracic location potentially has reduced tension at the anastomosis, the ability to remove some of the potentially ischemic gastric tip, a lower rate of anastomotic leak, and a lower incidence of RLN injury.30 However, a randomized trial did not show significant differences between these approaches.31 We found a decrease in recurrent nerve injury noted when using the Ivor Lewis approach with an intrathoracic anastomosis compared with the 3-incision McKeown approach with a neck anastomosis. This finding is similar to that reported in one meta-analysis of more than 5000 patients comparing TTE and THE. An increase in RLN injuries and leak were noted with a transhiatal approach with a neck anastomosis.32

There are a few series reporting excellent outcomes with an open esophagectomy.20–28,33 In one of the largest series of 3-incision esophagectomy, Swanson and colleagues23 reported an anastomotic leak in 8% and an operative mortality of 3.6%. In another large study with an Ivor Lewis approach, Visbal and colleagues24 reported an operative mortality of 1.4%, RLN injury in 0.9%, and a median length of stay in the hospital of 11 days, which are similar to our study.

We initially performed the MIE with a transhiatal approach. However, it became apparent that visualization higher up in the mediastinum was difficult. In addition, complete mediastinal lymph node dissection could not be performed. This led to us adopting the 3-incision McKeown-type approach to perform the MIE.5 Our approach has since evolved from this modified McKeown MIE to a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis approach. The shift was prompted by the changing demographics of patients with esophageal cancer and an effort to reduce the morbidity associated with RLN dysfunction. Since the vast majority of tumors that we now encounter are located in the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, the proximal esophageal resection margin is usually adequate with a high intrathoracic anastomosis. Furthermore, in the presence of distal tumor extension onto the gastric cardia, an intrathoracic location of the anastomosis potentially allows for a more extensive resection of the stomach and wider tumor margins distally. These factors, in combination with the minimal neck experience obtained during general surgical and thoracic surgical training, led to a greater degree of comfort in performing and teaching this operation as an Ivor Lewis MIE.

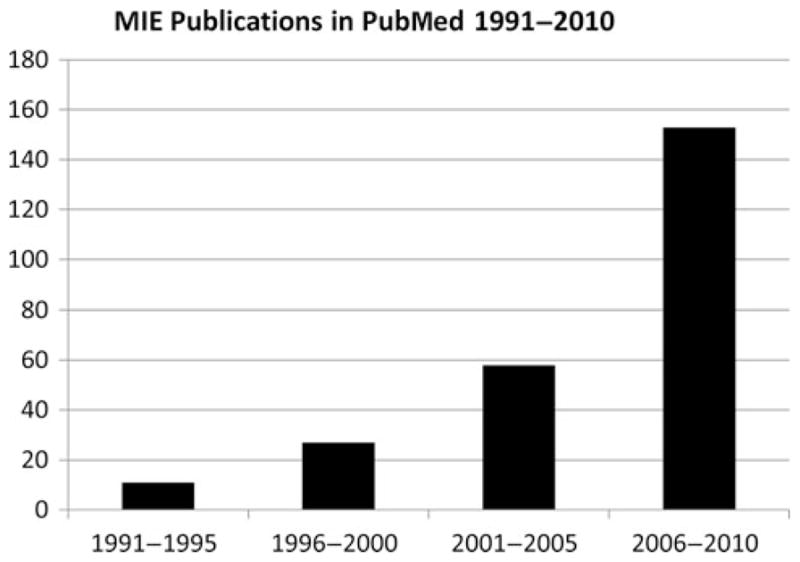

The use of minimally invasive approaches to esophagectomy is increasing and improved outcomes have been reported by other investigators after MIE.6,8,17 In our recent review of the medical literature using the US National Library of Medicine service, PubMed, to identify MIE-related reports, we noted a minimal number of publications on this topic less than a decade ago, and this has risen exponentially over the last few years (Fig. 4). In a recent study evaluating the trends in utilization and outcomes of MIE and open esophagectomy, Lazzarino et al17 reported an exponential increase in the performance of MIE in England and there was a trend toward better 1-year survival in patients undergoing MIE.17 In a systematic review of more than 1100 patients evaluating MIE and open esophagectomy, MIE was associated with decreased morbidity and a shorter hospital stay compared with open esophagectomy.34

FIGURE 4.

The rise in minimally invasive esophagectomy publications in United States National Library of Medicine service, PubMed.

Reducing the Risks of Surgery

There are several factors that are associated with a decrease in the risks of esophagectomy. These include hospital volume with mortality being significantly lower in high-volume centers.4 Orringer et al,35 in an important study of THE, reported the results in more than 2000 patients with the operative mortality rate that had steadily decreased with increasing hospital volume and surgeon experience from 10% to 1%. Similarly, these investigators demonstrated that complications, such as RLN injury, decreased with increased volume from 32% in the period of 1978 to 1982 to 1% to 2% in current era. These data point to the steep learning curve that general- and thoracic-trained surgeons will likely experience if the neck approach is chosen. Few surgeons or centers are likely to ever reach the excellent results of the neck approach in Orringer’s more recent series. Esophagectomy is a complex and technically challenging operation, and other factors that have an impact on outcomes include surgeon volume and specialty training of the surgeon. In addition, the daily participation of critical care specialists in the care of the patient is associated with improved outcomes.36–37 All of these factors may have contributed to our successful outcomes after MIE.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are that it is the largest to date investigating MIE, with more than 1000 patients, and that it is one of the first comparisons of the Ivor Lewis and modified McKeown MIE procedures. There are several confounding factors, however, in this retrospective analysis, which include differences in patient characteristics, the performance of the Ivor Lewis MIE in the more recent era, increasing surgeon experience, expertise in postoperative management and critical care, and other factors in evolution over time. Further work is needed to analyze the factors contributing to differences in outcomes. The other limitations of this study include those that are common to retrospective studies, including selection bias. In addition, longer follow-up is required to fully evaluate the oncologic results of MIE.

Future Directions

Recently, the preliminary results of a phase II multi-institutional study (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ECOG 2202) to evaluate the results of MIE in a multi-institutional setting were reported.6 In this multi-center cooperative group trial, we acted as the principal investigator center, and a total of 106 patients were enrolled. Morbidity was acceptable and the mortality was 2%. The long-term results of this trial are awaited. In addition, a randomized study, coordinated elsewhere, comparing MIE with open esophagectomy has also been initiated.38

CONCLUSIONS

In this largest series to date of MIE, we have shown that MIE is safe, with low mortality, acceptable morbidity, and a short length of stay. It must be noted that these results were obtained in a center with significant open and minimally invasive experience in esophageal surgery. Our current approach in patients with resectable esophageal cancer is a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with a 2-field lymph node dissection. The potential advantages of this approach include the potential for improved lymph node dissection in the mediastinum and potential for lower rates of anastomotic and RLN complications. Minimally invasive esophagectomy can be performed safely with good results in an experienced center.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shannon L. Wyszomierski, PhD, for her excellent editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Presented at American Surgical Association, 131st Annual Meeting, April 14–16, 2011, at Boca Raton, Florida.

References

- 1.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennathur A, Luketich JD. Resection for esophageal cancer: strategies for optimal management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:S751–S756. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennathur A, Farkas A, Krasinskas AM, et al. Esophagectomy for T1 esophageal cancer: outcomes in 100 patients and implications for endoscopic therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.060. Discussion 1054–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EVA, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luketich JD, Alvelo-Rivera M, Buenaventura PO, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;238:486–494. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089858.40725.68. Discussion 494–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Catalano PJ, et al. Results of a phase II multicenter study of MIE (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E2202) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl):15s. Abstract 4516. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennathur A, Awais O, Luketich JD. Technique of minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:S2159–S2162. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palanivelu C, Prakash A, Rangaswamy S, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenectomy in prone position. An experience of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuchert MJ, Luketich JD, Landreneau RJ, et al. Minimally-invasive esophagomyotomy in 200 consecutive patients: factors influencing postoperative outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1729–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgenthal CB, Shane MD, Stival A, et al. The durability of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: 11-year outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luketich JD, Nason KS, Christie NA, et al. Outcomes after a decade of laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onaitis MW, Petersen RP, Balderson SS, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is a safe and versatile procedure: experience with 500 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:420–425. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234892.79056.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, et al. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Percut Tech. 1991;1:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Banting S. Endoscopic oesophagectomy through a right thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1992;37:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depaula AL, Hashiba K, Ferreira EA, et al. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy with esophagogastroplasty. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percut Tech. 1995;5:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanstrom LL, Hanson P. Laparoscopic total esophagectomy. Arch Surg. 1997;132:943–949. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazzarino AI, Nagpa K, Bottle A, et al. Open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy. trends of utilization and associated outcomes in England. Ann Surg Ann Surg. 2010;252:292–298. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dd4e8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene FL American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.StataCorp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10.1. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, et al. Curative resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma: analysis of 100 en bloc esophagectomies. Ann Surg. 2001;234:520–530. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00011. Discussion 530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Transhiatal esophagectomy: clinical experience and refinements. Ann Surg. 1999;230:392–400. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00012. Discussion 400–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altorki N, Skinner D. Should en bloc esophagectomy be the standard of care for esophageal carcinoma? Ann Surg. 2001;234:581–587. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200111000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson SJ, Batirel HF, Bueno R, et al. Transthoracic esophagectomy with radical mediastinal and abdominal lymph node dissection and cervical esophagogastrostomy for esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1918–1924. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03203-9. Discussion 1924–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visbal AL, Allen MS, Miller DL, et al. Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1803–1808. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, Wilkins E, Jr, et al. Transthoracic esophagectomy: a safe approach to carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altorki N. En-bloc esophagectomy–the three-field dissection. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hulscher JBF, van Sandick J, de Boer AGEM, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerut T, Nafteux P, Moons J, et al. Three-field lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction in 174 R0 resections: impact on staging, disease-free survival, and outcome: a plea for adaptation of TNM classification in upper-half esophageal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:962–972. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000145925.70409.d7. Discussion 972–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizk N, Venkatraman E, Park B, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. The prognostic importance of the number of involved lymph nodes in esophageal cancer: implications for revisions of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennathur A, Zhang J, Chen H, et al. The “best operation” for esophageal cancer? Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:S2163–S2167. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F, et al. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:803–812. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098624.04100.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rindani R, Martin CJ, Cox MR. Transhiatal versus Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy: is there a difference? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O’Brien SM, et al. Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.042. Discussion 596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verhage RJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boone J, et al. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open procedures in esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Chang AC, et al. Two thousand transhiatal esophagectomies: changing trends, lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2007;246:363–372. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814697f2. Discussion 372–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dimick JB, Goodney PP, Orringer MB, et al. Specialty training and mortality after esophageal cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Heitmiller RE, et al. Intensive care unit staffing is associated with decreased length of stay, hospital cost, and complications after esophageal resection. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:904–905. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biere SS, Maas KW, Bonavina L, et al. Traditional invasive vs. minimally invasive esophagectomy: a multi-center, randomized trial (TIME-trial) BMC Surg. 11:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]