Abstract

Research shows that offenders perceive stigma, but the accuracy of these perceptions has not been assessed, nor their impact on successful reintegration. In a longitudinal study, jail inmates (N = 168) reported perceptions of stigma toward criminals and anticipated stigma just prior to release. A diverse college sample completed a parallel survey assessing stigmatizing attitudes toward criminals. Inmates’ perceived stigma was significantly higher than students’ stigmatizing attitudes. Perceived stigma positively predicted post-release employment for African-American inmates, but not for Caucasians. Anticipated stigma negatively predicted arrests for Caucasian inmates, but not for African Americans. Perceived and anticipated stigma may have different implications for reintegration, and these implications may vary across race.

“The distance between a prison and an ex-offender’s home community generally can be traversed by bus. But this conventional form of transportation masks the real distance the ex-offender must travel from incarceration to a successful reintegration into her community” (Thompson, 2004, p. 255).

Inmates face many hardships once they are released into the community, and being stigmatized as an ex-offender is often implicated as a major barrier to successful community reintegration. Offenders are one of the most stigmatized groups in society, yet the large body of research on stigma rarely considers offenders.

According to Link and Phelan (2001), stigma is a process that occurs when “elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination co-occur together in a power situation that allows the components of stigma to unfold (pg. 367).” Stigma exists at three levels in society: structural, social, and self. Stigma is thought to impact individual behavior through interactions between institutional barriers that marginalize groups (structural), stereotypes and discrimination from community members (social), and individual responses to these factors (self) (Link & Phelan, 2001). Therefore, stigma is a multifaceted construct that must be broken down into its specific components and carefully operationalized in research. Many stigma constructs are confounded with each other, making it difficult to conclude how specific aspects of the stigma process affect behavior. At the structural level, the laws and policies that restrict people from participating in society in some way (i.e. housing restrictions, being denied certain employment) are referred to as structural stigma (Corrigan et al., 2005). At the social level, the public’s stigmatizing attitudes and discrimination toward a group of people is commonly referred to as public stigma (Corrigan, Larson, Kuwabara, & Sachiko, 2010), though other construct labels (i.e. social stigma, enacted stigma) exist.

At the self level, individual responses to stigma often fall under the broad category of self-stigma (Corrigan et al., 2010). This encompasses several constructs including perceived stigma, which is most commonly defined as an individual’s perceptions of the public’s stigmatizing attitudes toward their group. In other research, perceived stigma is defined as an individual’s perceptions of the public’s stigma toward the self (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001). Also falling under the umbrella of self-stigma is internalized stigma, defined as the degree to which people accept stereotypes as being true of the self and feel devalued as a result (Corrigan, 1998; Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003). Anticipated stigma, defined as the anticipation of being rejected or discriminated against due to one’s identity, is often confounded with perceived stigma in research, but should be considered conceptually distinct (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009)—it refers to the anticipation of future events, and reflects the stigma people personally expect to experience whereas perceived stigma most commonly refers to the awareness of stigma. Some research on individual responses to stigma also measures previous experiences with being discriminated against or rejected (Markowitz, 1998). Pertinent to this paper are three stigma constructs: public stigma (the public’s attitudes toward a group of people), perceived stigma (individuals’ perceptions of the public’s attitudes toward their group), and anticipated stigma (individuals’ expectations of personally experiencing stigmatization from others). Whereas public and perceived stigma have been researched in multiple groups (Dijker & Koomen, 2007), anticipated stigma has received less empirical attention (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009).

Public Perceptions of Offenders (Public Stigma)

Just how do people in society feel about offenders? There is substantial research on the U. S. public’s perceptions of crime and criminal behavior from public polls as well as empirical studies. Qualitative research shows that people think negatively of “criminals.” People often think of stereotypes such as low socioeconomic status and minority race when thinking of criminals (Madriz, 1997) and associate negative personality traits with the word “criminal” (MacLin & Hererra, 2006). MacLin and Herrera (2006) found that one of the most common words undergraduates associated with the word “criminal” was “bad.”

Research on attitudes toward prisoners has shown that few groups of people, with the exception of police officers, endorse very negative attitudes (Melvin, Gramling, & Gardner, 1985; Sunyoung, 2009; Ortet-Fabrigat, Perez, & Lewis, 1993). So, research is mixed, showing that people associate negative qualities with criminals, but differ in the degree of stigmatizing attitudes they have toward prisoners.

Stigmatized People’s Perceptions of How the Public Views Their Group (Perceived Stigma)

Simply being aware of and perceiving stigma from society members is consistently linked to poor psychological and social functioning. Across non-correctional stigmatized groups (e.g. mental illness, HIV), research has shown that perceived stigma is linked to unemployment and income loss (Link, 1987), depression (Markowitz, 1998; Staring, Van der Gaag, Van den Berge, Duivenvoorden, & Mulder, 2009), poor social functioning (Prince & Prince, 2002; Perlick et al., 2001), low self-esteem (Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen, & Phelan, 2001), and negative coping styles (Perlick et al., 2007; Kleim et al., 2008). Research also shows a link between perceived stigma and lower likelihood of seeking treatment (Corrigan & Rusch, 2002).

In the criminology literature, the impact of stigma has been discussed in labeling theory (Lemert, 1974; Shoemaker, 2005) and in qualitative research (Schneider & Mckim, 2003), but little empirical research has explored perceived stigma among offenders. In one of the few studies assessing perceived stigma with offenders, Winnick and Bodkin (2008) examined how 450 male offenders thought people in society would react to the label of “ex-con.” Offenders perceived a great deal of stigma and reported perceiving the most stigma on items in the domains of employment and childcare. Offenders’ perceived stigma was also related to anticipating the use of negative coping styles. Similarly, Lebel (2012) measured 229 former prisoners’ perceived stigma toward ex-offenders. Participants perceived the highest levels of stigma on items assessing society’s overall negative attitudes and discrimination against ex-offenders. Lebel (2012) also found that having more parole violations was correlated with perceiving more stigma. In sum, these studies show that many offenders agree that the public stigmatizes offenders as a group, which we know is linked with poor psychological health and social functioning in other stigmatized groups.

Public Stigma vs. Perceived Stigma: The Case of People Living with HIV

One study compared a stigmatized groups’ perceived stigma to the public’s stigmatizing attitudes toward that group. Green (1995) assessed perceived stigma toward people with HIV in a sample of 42 people living with HIV/AIDS. A sample of 300 men and women from two cities in Scotland were asked about their attitudes toward people living with HIV/AIDS. Results showed that people living with HIV perceived more stigmatizing attitudes than the public reported on all 15 items of the questionnaire. No such studies have been conducted with offenders.

Stigmatized Peoples’ Expectations of being Discriminated Against (Anticipated Stigma)

Theory suggests that being aware of stigma may not be as important for functioning as one’s personal expectations about experiencing negative consequences from stigma. Research on the impact of anticipated stigma in any stigmatized group is scant. Quinn and Chaudoir (2009) examined psychological distress in people with different concealable stigmatized identities (e.g. mental illness, drug use, criminal actions) and found that participants’ anticipation of future stigma and their anticipated reaction to future stigma were correlated with depression and anxiety. No study has examined anticipated stigma in relation to future indices of psychological or social adjustment. As such, we do not know what outcomes may or may not be uniquely associated with anticipated stigma.

Race Differences

Research shows that there may be differences in how African American and Caucasian people think about stigma. For example, Rao, Pryor, Gaddist, and Mayer (2008) used item response theory to examine differences in HIV stigma (perceived stigma toward the group and the self, disclosure concerns, and negative self-image) in African American and Caucasian people living with HIV/AIDS; African Americans indicated greater stigmatization on items about feeling stigmatized by others whereas Caucasians reported greater stigmatization on items regarding keeping their identity a secret and being afraid of interpersonal rejection. The criminology literature suggests that being labeled an offender may be “redundant” for African Americans because they already manage racial stigma (Harris, 1965). Supporting this idea, Winnick and Bodkin (2009) found that Caucasian prisoners were more likely to endorse secrecy as a strategy for coping with stigma when compared to African American prisoners.

The Implications of Stigma for Subsequent Functioning

Research with mentally ill individuals has shown that perceived stigma predicts subsequent negative psychological and social consequences. Link and colleagues (2001) assessed perceived stigma and withdrawal tendencies in relation to future self-esteem at six and 24 month follow-ups. They found that perceived stigma and withdrawal tendencies predicted low self-esteem at both follow-up points when controlling for baseline levels of self-esteem and depression. Also, in a study of people with bipolar disorder, Perlick and colleagues (2001) found that perceived stigma predicted lower social adjustment with people outside of the family seven months after initial assessment.

Of the few studies that have investigated perceived stigma with offenders, none employed a longitudinal design. This is especially problematic as stigma is theorized to be a substantial barrier to the successful reentry of ex-offenders into society. In the criminology literature, labeling theory proposes that structural and public stigma results in offenders feeling like outsiders, causing them to withdraw from the community, and engage in higher rates of criminal actions. Research comparing officially labeled felons (considered the stigmatized group) to non-labeled felons lends some support to this theory. Chiricos, Barrick, and Bales (2007) found that labeled felons do subsequently engage in more crime than those not labeled felons; however, individuals were not randomly assigned to condition (presumably more serious offenders were labeled felons, whereas less serious offenders were processed as non-felons). Also, as in other studies premised off of labeling theory, offenders’ perceived stigma was not assessed, failing to capture stigma’s role in offenders’ ability/inability to integrate in society.

The Present Study

The present study aims to extend our understanding of the nature and implications of offenders’ stigma by addressing five questions. First, how much stigma do offenders perceive from the public toward their group and how much stigma do they anticipate personally experiencing? We hypothesize that offenders will perceive more stigma from the public toward criminals than they expect to personally experience. Stigmatized people may be aware of stigma, but might not expect to experience it personally; this is the case in other stigma research where perceptions of stigma are unrelated to agreement with stereotypes, application of stereotypes to the self-concept, and low self-esteem (Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006).

Second, how accurate is offenders’ perceived stigma? We expect that offenders will report perceiving more stigma from the public than community members report. Research with people living with HIV suggests that stigmatized people may overestimate the prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes held by the public (Green, 1995).

Third, does perceived stigma predict post-release employment and recidivism? We predict that offenders who perceive more stigma from the public will be more likely to be unemployed after being released from jail/prison relative to offenders who perceive less stigma. Research shows that in other stigmatized groups perceived stigma is linked to withdrawal tendencies (Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989; Perlick et al., 2007), and unemployment (Link, 1987). This withdrawal tendency might lead to the “why try” effect in which people are discouraged from trying to integrate in society (Corrigan et al., 2010). We hypothesize that perceived stigma will be related to subsequent recidivism for similar reasons and note that criminological theories purport that stigma is linked to recidivism through multiple mechanisms (e.g. labeling theory, self-fulfilling prophecy).

Fourth, does anticipated stigma predict post-release employment and recidivism? In parallel to the previous two hypotheses, we think that personally expecting to be discriminated against will also be related to low levels of employment and high rates of recidivism.

Fifth, will race moderate the links between perceived stigma and post-release employment and recidivism, and between anticipated stigma and post-release employment and recidivism? Criminological theory (Harris, 1965) suggests that ethnic minorities are not as affected by stigma as non-minorities. Research also shows that there may be differences in the ways that African Americans and Caucasians think about stigma (Rao et al., 2008). Further, studies on offenders’ perceived stigma have shown race differences in Caucasian and African American prisoner’s levels of perceived stigma and coping strategies (Winnick & Bodkin, 2008; Winnick & Bodkin, 2009).

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Jail Sample

Participants were recruited from June 2002 to May 2007 for a larger longitudinal study (Tangney, Mashek, & Stuewig, 2007) at an urban adult detention center. Data were collected shortly after entry into the jail (Time 1), again just before release (Time 2), and then at one year post-release (Time 3). Inmates were informed that participation was voluntary and that data were confidential, protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from DHHS. Time 1 and Time 2 interviews were conducted in the privacy of professional visiting rooms (used by attorneys), or secure classrooms. Pre-release interviews (Time 2) were collected from 2002-2010, depending on inmates’ release dates. Post-release interviews (Time 3) were collected from 2003 to 2010 by phone or (for those re-incarcerated) in person. Inmates who completed the 4-6 session Time 1 assessment received a $15-18 honorarium. Inmates received a $25 honorarium for completing the single Time 2 assessment, and a $50 honorarium for completing the single Time 3 assessment.

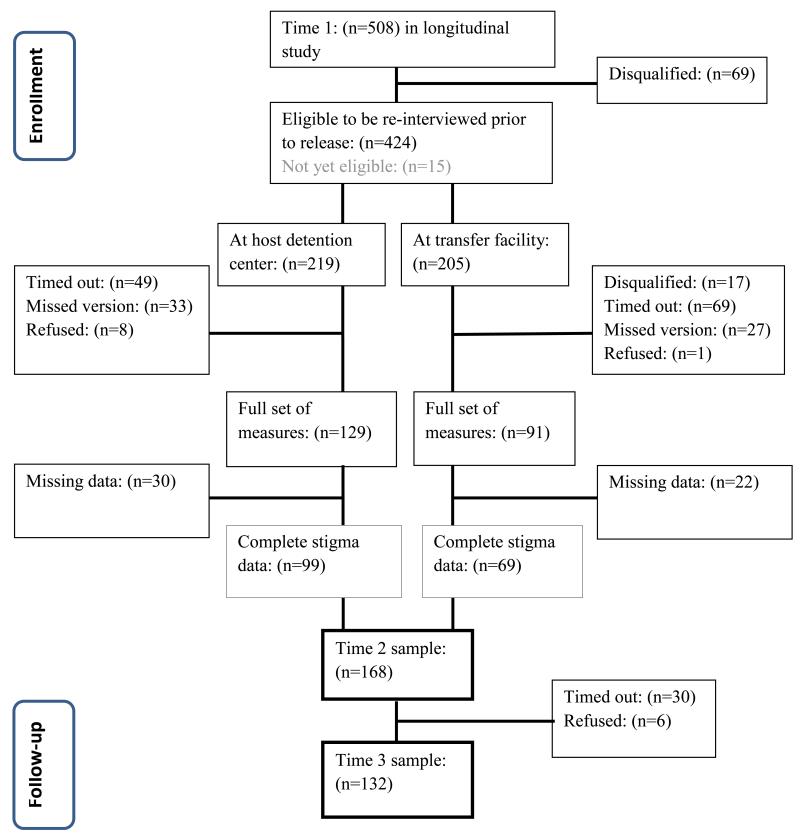

Of the 628 inmates consented at Time 1, 508 completed valid essential portions of the initial assessment (i.e. were not transferred or released to bond before the assessments could be completed) and were followed longitudinally. To be eligible for the Time 2 pre-release assessment, at least 6 weeks must have elapsed between initial assessment and pre-release assessment, a period of time over which meaningful change in key constructs was deemed possible. Many participants did not qualify for the pre-release assessment because they were released prior to the 6 week mark. Sample retention is diagrammed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample Retention.

Of the 508 inmates from Time 1, 424 were eligible to be re-interviewed prior to their release; 219 of these participants stayed at the host adult detention facility and 205 were transferred to other correctional facilities. Every effort was made to conduct pre-release interviews, but this was not always possible due to a lack of timely information on release dates, or because of the distance between the research site and the secondary correctional facility. Many of the participants were not reached in time to receive the full set of measures, yet eventually completed a missed version of the interview. These missed versions, however, did not contain the stigma measures, as they were collected after the participant was released into the community. Among those who completed the pre-release or post-transfer pre-release interview on time, 168 participants had full data for the stigma measures at Time 2, comprising the sample for this study. Out of the 168 participants who completed the perceived and anticipated stigma measure in Time 2, 132 (79%) completed Time 3 data collection (see Figure 1).Of these 132 participants, all had recidivism data and 124 had complete employment data. Demographics for the jail sample at Time 1, 2, and 3 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample Demographics.

| Jail Sample | Community Sample |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Intake (T1) | Pre-release (T2) | One year post- release (T3) |

||

| N | 508 | 168 | 132 | 597 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 68.1% | 72% | 73.5% | 27.3% |

| Female | 31.9% | 28% | 26.5% | 72.7% |

| Race/Ethnicity 1 | ||||

| African American | 44.8% | 46.4% | 49.2% | 10.4% |

| Caucasian | 35.9% | 35.1% | 34.8% | 58.1% |

| Hispanic/Other | 9.2% | 6.5% | 3.8% | 10.2% |

| Other/Mixed | 7.4% | 7.8% | 6.8% | 0.7% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.8% | 4.2% | 5.3% | 23.1% |

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 33 yrs. | 34 yrs. | 34 yrs. | 21 yrs. |

| Standard Deviation | 10.04 | 10.21 | 10.34 | 3.93 |

| Employment Data (N = 124) | ||||

| Employed at any point in year | 86.3% | |||

| Odd Jobs | 6.5% | |||

| Part-time Job | 12.1% | |||

| Full-time Job | 67.7% | |||

| Unemployed entire year | 13.7% | |||

| Recidivism Data (N = 132) | ||||

| Committed Crime | 67.4% | |||

| Did not Commit Crime | 32.6% | |||

Note

Community sample race/ethnicity percentages do not equal 100 percent due to overlapping categories.

Community Sample

Participants were 597 undergraduate students at a large, diverse university which attracts a high percentage of commuter students (many “returning students”) from the community. Thus, relative to other college campuses, this student sample is more representative of the surrounding community in terms of ethnicity/race, than is typically the case, with approximately 60% being Caucasian. The sample ranged in age from 18 to 58; still, the mean age was 21 years and the sample was largely female (see Table 1). Students were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age. Participants, typically non-majors taking introductory psychology as a breadth requirement, received course credit for participation. Questions assessing stigmatizing attitudes toward criminals and other demographics were included in a larger group of measures in an online survey completed from May to December of 2009.

MEASURES

Jail Sample

A battery of measures was given at entry into the jail (Time 1); relevant to these analyses were demographics including gender, age, race, pre-incarceration employment, and years of education completed.

Perceived and Anticipated Stigma

The Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma measure (IPES; Mashek, Meyer, McGrath, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2002) consists of 12 items and was administered at Time 2 before inmates’ release into the community. The instructions for this measure first asked inmates to think of how people in society feel toward criminals, and the second half asked them to think about how they would be treated once released. The items in the second half of the measure were not specific to discrimination about being an offender, but the instructions for this questionnaire emphasized that the inmates should think about discrimination in the context of being an offender. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale from “1” “totally disagree” to “7” “totally agree,” with a higher score reflecting more perceived and anticipated stigma. A principal axis factor analysis using promax rotation extracted two factors. Six items loaded onto the first factor with loadings all above 0.4. This six-item factor accounted for 43.2% of the variance and reliability (Chronbach’s alpha) was 0.83. This factor was labeled “Perceived Stigma” and assessed inmates’ perceptions of how the public feels toward “criminals” (ex. “People on the outside think criminals are bad people”). Four items loaded onto the second factor with loadings all above 0.6. The second factor was labeled “Anticipated Stigma” and assessed inmates’ expectations of personally experiencing discrimination after release into the community (ex. “People in the community will accept me”). This four-item factor accounted for 21% of the variance and reliability (Chronbach’s alpha) was 0.81. Two items (“people on the outside believe criminals are good people who do bad things” and “people on the outside think criminals have good reasons for committing certain crimes”) were removed because they did not load onto either factor (loadings below 0.1). Both scales were normally distributed (see Table 2 for descriptives) and were significantly correlated with each other (r = .36, p = .000).

Table 2. Univariate Statistics.

| Variable | N | Mean | S.D. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Possible Range |

Actual Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVs | |||||||

| Perceived Stigma | 167 | 4.30 | 1.21 | −.36 | .06 | 1.00-7.00 | 1.00-7.00 |

| Anticipated Stigma | 161 | 3.35 | 1.44 | .37 | −.06 | 1.00-7.00 | 1.00-7.00 |

| Public Stigma | 589 | 2.99 | 1.09 | .05 | −.58 | 1.00-7.00 | 1.00-6.00 |

| DVs | |||||||

| Employment Status1 | 124 | 2.56 | .71 | −1.29 | .20 | 1.00-3.00 | 1.00-3.00 |

| Total Hours Employed2 | 122 | 1133.40 | 730.18 | −.36 | −1.43 | 0.00-1920.00 | 0.00-1920.00 |

| Arrest Diversity3 | 132 | .71 | .91 | 1.59 | 3.34 | 0.00-16.00 | 0.00-5.00 |

| Offense Diversity3 | 131 | 1.15 | 1.36 | 1.15 | .548 | 0.00-16.00 | 0.00-5.00 |

| Violent Recidivism4 | 131 | .20 | .40 | 1.53 | .35 | 0.00-1.00 | 0.00-1.00 |

Note.

Categorical variable analyzed with ordinal regression.

Continuous variable analyzed with regular regression.

Count variables analyzed with negative binomial regressions to account for skewness.

Dichotomous variable analyzed with logistic regression.

Employment

Pre-incarceration employment status (Time 1) and one year post-release employment status (Time 3) were assessed by asking participants whether they were unemployed, or had odd jobs, part-time employment, or full-time employment in the year prior to entering the jail (and the year after release from jail). Employment status was categorized with “1” being unemployed for the entire year, “2” having part-time or odd job employment, and “3” having full-time employment. Part-time and odd job employment were combined because of small numbers of participants in the odd jobs category; odd jobs were considered to be most similar to part-time employment in terms of hours. The majority of participants (67.7%) reported having full-time employment in the year after release, causing some restriction of variance in the employment status variable.

In addition to employment status at Time 3, a continuous variable (total hours employed) was created to represent degree of employment in the year after release. Since a typical work week for an average individual living in the United States is about 40 hours, the response “yes, held full-time jobs (35 hours or more per week)” was coded as 40 hours. The response “yes, held part-time jobs (35 hours or less per week)” was coded as 20 hours. The response “yes, did odd jobs (occasional or irregular work)” was coded 5 hours. The number of hours for each participant was then multiplied by the number of weeks they were employed during the year after release. Hours employed ranged from 0 to 1920; the distribution covered the full range, and showed minimal skewness and kurtosis, although there were substantial clusters at the extreme ends of the distributions reflecting unemployed and full-time employed participants (see Table 2).

Recidivism

Participants self-reported whether they had been arrested for or had committed any of 16 types of crime (e.g. theft, assault, drug offenses, etc.) during the year after their release (Time 3). Self-reported recidivism converges with official records (Huizinga & Elliott, 1986), and considerable variance was observed in self-reported offenses in the current study, further attesting to validity. Two variables were created to assess criminal versatility (the number of different types of crimes is used instead of frequency which is confounded with type of crime). The arrest diversity variable measured the number of different types of crimes participants were arrested for and the offense diversity variable measured the number of different types of crimes participants committed, but were not arrested for. The actual range for both of these variables was 0 to 5 types of crimes; because many participants reported committing zero offenses or having zero arrests, both of the criminal versatility variables were positively skewed (see Table 2). Another variable was created to capture violent recidivism. If participants reported committing a violent offense (arrest or undetected offense), they received a “1” and if they did not, they received a “0.”

Community Sample

Public Stigma

The Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma (IPES) measure was reworded to form a parallel 12-item measure entitled Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward Criminals (SATC). For instance, “People on the outside think all criminals are the same” in the IPES was reworded in the SATC to “I think all criminals are the same.” Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale. A principle axis factor analysis with promax rotation yielded one factor with loadings all above 0.5. The same two items that were removed from the IPES were removed from the SATC because neither loaded onto the factor (loadings below 0.3). Additionally, item 12 (“I am proud of people who have served time in jail/prison”) was removed because it did not load onto the factor (loading below 0.1). The remaining 9 items accounted for 47.61% of the variance. The same six items from the IPES Perceived Stigma scale were used for analyses in order to create a parallel scale in the two samples; reliability for these six items was .81 and the variable was normally distributed (see Table 2). The three items of the SATC that were parallel to the second subscale of the IPES, the Anticipated Stigma subscale, were not used in any further analyses.

Results

Inmates’ perceived and anticipated stigma were positively correlated (r = .36, p = .000). There were no significant differences between African Americans’ and Caucasians’ perceived stigma (t(135) = −.94, p = .347) or anticipated stigma (t(129) = −1.51, p = .134) at pre-release. Similarly, there were no significant differences between males and females in their perceived stigma (t(165) = −1.39, p = .168), nor in their anticipated stigma (t(159) = −.18, p = .856). Perceived stigma was unrelated to age (r = −.08, p = .320) and years of education completed (r = −.09, p = .225). Anticipated stigma was also unrelated to age (r = .03, p = .748) and years of education completed (r = −.12, p = .145).

How much stigma do offenders perceive from the public and personally expect to experience?

In general, inmates nearing release into the community perceived considerable public stigma toward offenders. For example, 62.3% agreed somewhat, moderately, or totally with the statement “People on the outside think once a criminal, always a criminal;” 68.3% agreed somewhat, moderately, or totally with the statement “People on the outside think criminals are bad people.” When comparing the overall means of perceived versus anticipated stigma, inmates’ perceived stigma was significantly higher (M = 4.30, SD = 1.22) than their anticipated stigma (M = 3.35, SD = 1.44), t(159) = 7.95, p = .000). Inmates tend to perceive a great deal of stigma being directed at criminals, but do not expect to personally experience such high levels.

How accurate is offenders’ perceived stigma toward “criminals?”

To assess the accuracy of inmates’ perceived stigma, their responses were compared to the parallel measure of college students’ stigmatizing attitudes. Inmates’ perceived stigma was significantly higher (M = 4.30, SD = 1.21) than students’ stigmatizing attitudes toward criminals (M = 2.99, SD = 1.09), t(754) = 13.37, p = .000. Table 3 shows individual item mean differences between the two samples. Across all items, inmates consistently perceived higher levels of stigma than students reported.

Table 3. Item mean differences in perceived and public stigma.

| Jail Sample | Community Sample |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| 1. People on the outside/I think all criminals are the same. |

4.72 | 1.80 | 2.27 | 1.55 | 16.111*** |

| 2. People on the outside/I think criminals can become better people. |

3.21 | 1.36 | 2.90 | 1.35 | 2.60** |

| 3. People on the outside/I think once a criminal, always a criminal. |

4.57 | 1.81 | 3.09 | 1.54 | 9.631*** |

| 4. People on the outside are/I am scared of anyone who has done time. |

4.36 | 1.64 | 3.42 | 1.67 | 6.44*** |

| 5. People on the outside/I think criminals are bad people. |

4.86 | 1.59 | 3.35 | 1.53 | 11.14*** |

| 7. People on the outside/I think criminals are evil. |

4.05 | 1.63 | 2.93 | 1.46 | 8.49*** |

Note. Item 2 was reverse coded.

indicates corrected t-tests for unequal variances

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Stigma and Subsequent Employment

Of the 168 inmates who completed the stigma measures just prior to release (Time 2), 124 reported on their employment at one year post-release (Time 3). The majority of former inmates had full-time employment (67.7%), 18.6% had part-time employment or held odd jobs, and 13.7% were unemployed. Two outcome variables were used to assess post-release employment; employment status at one year post-release and hours employed throughout the first year post-release. Perceived stigma was unrelated to employment status (spearman’s rho = .15, p = .088) and total hours employed (r = .08, p = .378). Anticipated stigma was also unrelated to employment status (spearman’s rho = −.05, p = .613) and total hours employed (r = −.04, p = .672).

Because age, years of education, and previous employment are thought to be predictive of employability, these Time 1 variables were controlled for in multivariate models. Ordinal regressions were conducted for employment status due to the categorical nature of the employment status variable; complementary log-log link functions were used to account for the unbalanced distribution in the higher category (Chen & Hughes, 2004) of full-time employment. Hierarchical regressions were used for the continuous dependent variable (total hours employed). Perceived stigma and anticipated stigma served as the independent variables in separate regressions along with race and the interaction of race with each type of stigma.

For perceived stigma, there was a main effect for age and pre-incarceration employment status (see Table 4). Those who were younger and were previously employed were more likely to be employed during the year post-release. There was no main effect for race. There was a trend for perceived stigma to positively predict employment status one year post-release, which was qualified by a race by perceived stigma interaction. Follow-up analyses indicated that, contrary to our hypothesis, perceived stigma positively predicted employment status for African American inmates (r = .27, p = .031). Among Caucasian inmates, perceived stigma negatively, but not significantly, predicted employment status (r = −.09, p = .573).

Table 4. Multiple regressions predicting post-release employment from perceived and anticipated stigma.

| Perceived Stigma |

Anticipated Stigma |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S. E. | Sig. | B | S.E. | Sig. | |

| Employment Status 1 | ||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | −.04 | .02 | .02* | −.04 | .02 | .04* |

| Years of Education | .14 | .09 | .12 | .08 | .09 | .37 |

| Pre-Incarceration Employment | .50 | .13 | .00** | .54 | .13 | .00** |

| Race | −.15 | .36 | .68 | −.28 | .37 | .46 |

| Type of Stigma | .23 | .12 | .06 | −.17 | .12 | .13 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Race X Type of Stigma | .73 | .26 | .01** | −.23 | .23 | .33 |

| Total Hours Employed 2 | ||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | −9.38 | 6.42 | .15 | −8.41 | 6.72 | .21 |

| Years of Education | 73.99 | 33.60 | .03* | 60.73 | 35.51 | .09 |

| Pre-Incarceration Employment | 255.38 | 56.32 | .00** | 259.19 | 57.68 | .00** |

| Race | −134.49 | 136.42 | .33 | −146.29 | 140.83 | .30 |

| Type of Stigma | 50.06 | 50.03 ΔR2 =.26 |

.32 | −23.07 | 47.19 ΔR2 = .24 |

.63 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Race X Type of Stigma | 286.03 | 101.13 ΔR2 =.06 |

.01** | 67.06 | 95.25 ΔR2 =.00 |

.48 |

Note. Each type of stigma (perceived and anticipated) was used as a predictor for each outcome. Statistics for each type of stigma are reported in the appropriate column in this table. Race was coded as 0-Caucasian, 1-African American.

Ordinal regressions were used due to the categorical nature of the dependent variable (N = 98-103).

OLS regression was used for this continuous outcome (N = 97-102).

p < .05

p < .01

Regarding total hours employed during the first year post-release (see Table 4), there was a main effect for pre-incarceration employment and years of education completed. There was no main effect for race or perceived stigma, however, there was a significant interaction. As with employment status, follow-up analyses indicated that among African Americans, perceived stigma was positively related to hours employed (r = .29, p = .022) and for Caucasians, perceived stigma was negatively, but not significantly, related to total hours employed (r = −.22, p = .178).

Another set of models were run substituting anticipated stigma for perceived stigma (see Table 4). There was a main effect for age and pre-incarceration employment on employment status one year post-release. There was no main effect for race or anticipated stigma and no interaction between the two. Regarding total hours employed in the first year after release, there was a main effect for pre-incarceration employment and a trend for years of education completed. There was no main effect for race or anticipated stigma and no interaction between the two.

Stigma and Subsequent Recidivism

Of the 168 inmates who completed stigma measures at pre-release (Time 2), 132 provided self-reports of recidivism in reference to the first year post-release (Time 3). Of these, 49% reported being arrested for at least one type of crime, and 56% reported committing at least one type of undetected offense, with 67% having one or both. Twenty percent reported committing a violent offense in that year. Perceived stigma was unrelated to arrest diversity (r = .13, p = .128) and offense diversity (r = .05, p = .565), but was positively related to violent offending (r = .21, p = .019). Anticipated stigma was unrelated to arrest diversity (r = −.06, p = .542), offense diversity (r = −.07, p = .439), and violent offending (r = .01, p = .923).

Due to skewness in the dependent variables, negative binomial regressions were conducted for arrest and offense diversity. Logistic regressions were used for the dichotomous violent offense variable. For each dependent variable two regressions were run; one using perceived stigma as the independent variable and a second with anticipated stigma as the independent variable. Perceived stigma and race did not predict arrest diversity (see Table 5). Furthermore the interaction was not significant. Similarly, perceived stigma, race, and the interaction were non-significant when predicting offense diversity. In a logistic regression, perceived stigma positively predicted violent offending in the year after release (b = .45, S.E. = .22, p = .041, OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.02 - 2.42). The more inmates perceived that the public has stigmatizing attitudes toward criminals, the more likely they were to reoffend violently in the first year post-release. These results generalized across Caucasian and African American inmates as there was no interaction with race (b = .17, S. E. = .44, p = .701, OR = 1.18, 95% CI = .50 - 2.78).

Table 5. Negative Binomial regressions predicting recidivism from perceived and anticipated stigma.

| Perceived Stigma |

Anticipated Stigma |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S. E. | Sig. | B | S.E. | Sig. | |

| Arrest Diversity | ||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Race | .02 | .30 | .94 | −.02 | .31 | .96 |

| Type of Stigma | .18 | .13 | .16 | −.10 | .11 | .36 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Race X Type of Stigma | −.35 | .27 | .20 | −.41 | .23 | .08 |

|

| ||||||

| Offense Diversity | ||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Race | .23 | .26 | .39 | .26 | .27 | .34 |

| Type of Stigma | .07 | .11 | .54 | −.08 | .09 | .40 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Race X Type of Stigma | −.05 | .21 | .82 | −.04 | .19 | .82 |

Note. Each type of stigma (perceived and anticipated) was used as a predictor for each outcome. Statistics for each type of stigma are reported in the appropriate column in this table.

Negative binomial regressions were conducted due to positive skewness in arrest and offense diversity variables.

N = 106-111 for arrest diversity and N = 105-110 for offense diversity.

Race was coded as 0-Caucasian, 1-African American.

p < .05

Another set of models were run substituting anticipated stigma for perceived stigma (see Table 5). There was a trend for race to moderate the effect of anticipated stigma on arrest diversity. For African Americans, anticipated stigma positively, but not significantly, predicted arrest diversity (r = .11, p = .377) whereas for Caucasians, anticipated stigma negatively predicted arrest diversity (r = −.29, p = .053). Anticipated stigma and race did not predict offense diversity and there was no interaction between the two. In a logistic regression, anticipated stigma did not predict violent offending (b = −.05, S.E. = .18, p = .767, OR = .95, 95% CI = .67 - 1.34) or interact with race to predict violent offending (b = .33, S. E. = .36, p = .352, OR = 1.39, 95% CI = .69 - 2.80).

Discussion

Inmates’ Perceived and Anticipated Stigma

This study shows that jail inmates perceived a fairly high level of public stigma, replicating findings from other studies of offenders’ perceived stigma (Winnick & Bodkin, 2008; Lebel, 2012). We found that inmates’ perceived stigma was only modestly correlated with anticipated stigma (r = .36) and inmates’ perceived stigma was significantly higher than their anticipated stigma, indicating that they are distinct phenomena with potentially different implications for functioning. This discrepancy between perceived stigma toward the group and variables reflecting stigma toward the self is found in multiple stigmatized groups (Foster & Matheson, 1999). Additionally, this result is consistent with the research showing only modest relationships between perceived stigma and variables reflecting how individuals personally feel about being part of a stigmatized group (Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006). Theory on stigma processes suggests that perceived stigma is the first step in a causal process in which individuals come to anticipate rejection and engage in maladaptive behavior (Link et al., 1989), but that people respond differently to perceived stigma, affecting the consequences they experience.

Future research is needed to clarify what moderates the relationship between perceiving stigma from the public and personally expecting to be discriminated against; relevant variables that may moderate this link could include those that reflect how one cognitively processes stigma (i.e. internalized stigma) (Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006), how one incorporates stigma into one’s identity (Latrofa et al., 2009), attitudes toward one’s stigmatized group, and other individual personality characteristics such as shame-proneness.

Perceived Stigma and Post-release Functioning

This study showed that perceiving stigma from the public is linked to positive and negative outcomes for offenders. The majority of research on perceived stigma has shown that the more individuals report feeling that the public stigmatizes their group, the more likely they are to report negative psychological and social outcomes. Therefore, it was hypothesized that inmates’ perceived stigma before release would predict poorer post-release functioning, but this was only partially supported. Unexpectedly, perceived stigma positively predicted employment status and the amount of time African Americans were employed in the year after release. Though the majority of psychological research links stigma to negative outcomes, there is evidence to suggest that under some circumstances, stigma can lead to positive outcomes; models of the stigma process suggest that negative responses such as internalized stigma are but one response to perceived stigma, and positive responses include indifference as well as becoming involved in social activism (Watson & River, 2005). Other research, though mainly qualitative, shows that some stigmatized individuals feel empowered by their stigmatized identity (Camp, Finlay & Lyons, 2005).

In regards to the interaction by race, this finding may reflect an idea that is prevalent in stigma research concerning the differential impact of stigma for those with an obvious stigmatized identity such as race or gender, and those with a concealable stigmatized identity such as homosexuality, poverty, or having a criminal record; those with concealable identities are shown to experience more negative psychological effects from stigma compared to those with obvious identities (Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998). Along those lines, African American offenders likely have pre-existing knowledge of the hardships in society due to experiences with or knowledge of minority stigma/discrimination, and may be less impacted by public stigma. African Americans may actually be motivated to work harder to attain employment. This idea that African Americans work extra hard to overcome stigma is prevalent in other stigma literature and is sometimes referred to as “John Henryism” (Link & Phelan, 2001). According to Winnick and Bodkin (2009), the fact that African Americans have to manage racial stigma overshadows the management of stigma related to being an offender.

Although the relationship between perceived stigma and employment among Caucasians was non-significant, the relationship was significantly different from African Americans (as per the significant interaction). Research suggests that Caucasians and other majority groups in society may be more negatively impacted by stigma than minority groups. It may be that Caucasians who perceive stigma are more likely to feel ashamed (Winnick & Bodkin, 2009) which may impede their motivation or self-efficacy for obtaining employment.

Perceived stigma generally did not predict recidivism, except in the case of violent recidivism. Inmates who perceived more public stigma were more likely to commit violent offenses in the year after their release. It may be that perceiving more public stigma is cyclically related to more involvement in criminal behavior. For instance, offenders who committed violent crimes after their release may have committed violent offenses prior to the current incarceration; these offenders might be more likely to perceive more stigma toward criminals due to the fact that they more closely fit the stereotype of a typical “criminal.” This idea is supported by Lebel’s (2012) finding that violent felony convictions predicted higher levels of perceived stigma in prisoners. Models of the stigma process show that perceived stigma is linked to a variety of negative outcomes through maladaptive coping; perceived stigma may be related to criminal behavior through maladaptive coping such as withdrawal from the community, which is thought to increase the likelihood of engaging in criminal activities. Similar to coping by withdrawal from the community, perceiving high levels of stigma may increase the distance felt between the self and the conventional community, and may possibly increase closeness felt with a criminal community where more violent crime is perpetrated, often referred to as criminal embeddedness in criminology literature. Two recent studies with offenders showed that criminal embeddedness was positively correlated with perceived stigma; criminal embeddedness measured as normalization of crime and identification with other offenders was positively correlated with perceived stigma (Lebel, 2012), as well as a mixed measure of perceived and anticipated stigma in another study (Benson, Alarid, Burton, & Cullen, 2011). Identification and connectedness with one’s group are not always thought of as ways that people cope with perceived stigma (i.e. “social shelter” from conventional society), but are sometimes thought of as precursors to perceived stigma; regardless of the causal relationship, these variables are likely important when researching how stigma impacts offenders’ criminal behavior (Lebel, 2012).

Anticipated Stigma and Post-release Functioning

Unlike perceived stigma, inmates’ anticipated stigma did not predict post-release employment status or the amount of time inmates were employed. The fact that anticipated stigma did not have more predictive ability was surprising. Stigma theory suggests that once individuals anticipate rejection, they will experience negative consequences; however, because there is likely a great deal of variance in how people respond to stigmatization, anticipated stigma may not consistently predict certain negative outcomes. When people expect to be treated unfairly, some may feel that applying for jobs is pointless, and so remain unemployed. On the other hand, others may feel that they have to try harder to find employment, applying to multiple jobs until they are hired.

Regarding recidivism, anticipated stigma was differentially related to arrest for African Americans and Caucasians. Caucasian inmates who anticipated high levels of stigma were significantly less likely to be arrested for crimes in the year after their release, relative to Caucasians with low anticipated stigma. Among Caucasian inmates, anticipated stigma may be associated with more negative attitudes about crime and criminality, and therefore a lower likelihood of engaging in subsequent criminal behavior. No such effect was observed among African American inmates. It may be that African American inmates expect to experience discrimination for a range of different reasons, which may attenuate the relationship. So, people likely have maladaptive as well as adaptive responses to stigma, even after anticipating rejection. Investigation of the moderators in the relationship between anticipated stigma and outcomes is needed.

In sum, among inmates nearing community re-entry into the community, perceived and anticipated stigma may affect behavior in different ways, both positively and negatively. In some domains, for certain ethnic groups, stigma may have positive implications, possibly because perceiving or anticipating stigma prepares inmates to meet challenges they will face in the community. In other domains and for other inmates, stigma may have negative implications, possibly because perceiving or anticipating stigma leads to shame, discouragement, or anger. It will be helpful to measure emotional and social responses to perceived and anticipated stigma in future research.

Limitations and Future Directions

This sample of jail inmates was drawn from one jail, potentially limiting the generalizability of these findings. For instance, jail inmates in other geographic locations and prison inmates may perceive or anticipate more or less stigma from the community. Also, due to sample size, there was low power for detecting stigma by race interactions. The jail sample stigma data were collected from 2002 to 2010, whereas the students’ stigmatizing attitudes were assessed in 2009; it is possible that the inmates’ perceived stigma may have been more accurate if compared to a community sample that was collected during the same time frame due to changes in economic and social barriers over time. Future comparisons of perceived stigma and public stigma would ideally be done with data collected within the same time frame.

In regards to measurement, the items used to assess anticipated stigma could have been more precise. Though the instructions to inmates were prefaced to think of how others in society feel about “criminals” for the questions regarding perceived stigma and then how others feel about them personally for the anticipated stigma items, the items were not worded to specifically reflect the stigma of being an offender. It is possible that inmates with multiple stigmas (e.g. minority inmates) may have been thinking of stigma more generally instead of focusing on how they expected to be treated considering that they are an offender.

Much more research is needed to understand stigma in correctional populations, especially research focusing on the emotional and cognitive responses to stigma that may mediate and moderate these relationships. According to the stigma literature, internalized stigma, a mental state in which stigmatized people believe that the prejudice and stereotypes against them accurately reflect who they are, seems to be important to assess because of its link to low self-esteem, depression, and social isolation (Corrigan et al., 2010). Other psychological variables worth evaluating are social withdrawal, motivation, shame-proneness, and criminal identity. Criminal identity is likely to affect how people respond to public stigmatization, as people who have committed crimes likely vary in the degree to which they feel like a “criminal” and the frequency with which they associate with others who commit crime. These psychological variables are apt to be important in understanding the relationship between perceiving and expecting stigmatization and subsequent behavior. Further investigation is also needed to understand why there are race differences in the relationship between stigma and functioning. This research could yield important information about how to address stigma with different groups of offenders.

Clinical Implications

Identifying groups of inmates who are apt to respond to stigma in positive and negative ways has practical implications for offender re-entry and community transition planning. In general, the discrepancy between perceived and public stigma may be useful to discredit overly-negative perceptions and combat poor emotional and cognitive responses to perceived stigma. In the context of the present study, inmates who are vulnerable to negative outcomes from perceived and anticipated stigma could be taught to have realistic expectations about re-entering society, cognizant of hardships they may face but aware that rejection is not inevitable. Interpretation of the discrepancy between inmates’ perceived stigma and public stigma in the present study must be made with some caution. The college student sample, although diverse and similar in many ways to the community that inmates are likely to encounter when released from jail, differed in some key respects—notably, the student sample was younger and proportionally more female than the surrounding community.

How can we enhance the good in addition to preventing the bad effects from perceiving and anticipating stigma? Identifying inmates who are more likely to respond positively to stigma will inform interventions with inmates who are vulnerable to the negative effects of stigma. For example, if motivation or optimism are key factors for minorities in reaping positive consequences from perceiving or anticipating stigma, programs for non-minority offenders could focus on increasing motivation despite being stigmatized. A better understanding of the processes and outcomes of stigma can no doubt inform interventions with inmates, ultimately leading to a “shorter distance the ex-offender must travel to a successful reintegration into the community.”

References

- Benson ML, Alarid LF, Burton VS, Cullen FT. Reintegration or stigmatization? Offenders’ expectations of community re-entry. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011;39:385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV Stigma Scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp DL, Finlay WML, Lyons E. Is low self-esteem an inevitable consequence of stigma? An example from women with chronic mental health problems. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Hughes J. Using ordinal regression model to analyze student satisfaction questionnaires. IR Applications. 2004;1:1–13. Retrieved from EBSCOhost (ED504366) [Google Scholar]

- Chiricos T, Barrick K, Bales W. The labeling of convicted felons and its consequences for recidivism. Criminology. 2007;45:547–581. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5:201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Kuwabara SA, Sachiko A. Social psychology of the stigma of mental illness: Public and self-stigma models. In: Maddux JE, Tangney JP, editors. Social Psychological Foundations of Clinical Psychology. Guilford; New York: 2010. pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Heyrman ML, Warpinski A, Gracia G, Slopen N, Hall LL. Structural stigma in state legislation. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:557–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Rusch N. Mental illness stereotypes and clinical care: Do people avoid treatment because of stigma? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills. 2002;6:312–334. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Dijker AJM, Koomen W. Stigmatization, tolerance, and repair: An integrative psychological analysis of responses to deviance. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foster MD, Matheson K. Perceiving and responding to the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1319–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DES, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:909–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G. Attitudes towards people with HIV: Are they as stigmatizing as people with HIV perceive them to be? Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:557–568. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AR. Race, commitment to deviance and spoiled identity. American Sociological Review. 1965;41:432–442. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Elliott DS. Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1986;2:293–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B, Vauth R, Adam G, Stieglitz R, Hayward P, Corrigan P. Perceived stigma predicts low self-efficacy and poor coping in schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health. 2008;17:482–491. [Google Scholar]

- Latrofa M, Vaes J, Pastore M, Cadinu M. “United we stand, divided we fall’! The protective function of self-stereotyping for stigmatised members’ psychological well-being. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2009;58:84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel TP. Invisible stripes? Formerly incarcerated persons’ perceptions of stigma. Deviant Behavior. 2012;33:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lemert JB. Beyond Mead: The societal reaction to deviance. Social Problems. 1974;21:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLin MK, Herrera V. The criminal stereotype. North American Journal of Psychology. 2006;8:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Madriz EI. Images of criminals: A study on women’s fear and social control. Gender and Society. 1997;11:342–356. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39:335–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashek D, Meyer P, McGrath J, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma (IPES) George Mason University; Fairfax, VA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Melvin KB, Gramling LK, Gardner WM. A scale to measure attitudes towards prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1985;12:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ortet-Fabregat G, Perez J, Lewis R. Measuring attitudes toward prisoners: A psychometric assessment. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1993;20:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Link BG, Struening E, Kaczinsky R, Gonzalez J, Manning LN, Wolff N, Rosenheck RA. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:535–536. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, Sirey J, Salahi J, Struening EL, Link BG. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1627–1632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince PN, Prince CR. Perceived stigma and community integration among clients of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2002;25:323–331. doi: 10.1037/h0095005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Pryor JB, Gaddist BW, Mayer R. Stigma, secrecy, and discrimination: Ethnic/racial differences in the concerns of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:265–271. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingham PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, McKim W. Stigmatization among probationers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2003;38:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker DJ. Theories of delinquency: An examination of explanations of delinquent behavior. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Staring ABP, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mulder CL. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyoung P. Doctoral dissertation. Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Indiana, PA: 2009. College students’ attitudes toward prisoners and prisoner reentry. Retrieved from Proquest Research Library (AAI3205399) [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Mashek D, Stuewig J. Working at the social-clinical-community-criminology interface: The George Mason University inmate study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:1–21. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2007.26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AC. Navigating the hidden obstacles to ex-offender reentry. Boston College Law Review. 2004;45:255–306. [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, River PL. A social-cognitive model of personal responses to stigma. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the Stigma of Mental Illness: Practical Strategies for Research and Social Change. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Winnick TA, Bodkin M. Anticipated stigma and stigma management among those to be labeled “ex-con.”. Deviant Behavior. 2008;29:295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Winnick TA, Bodkin M. Stigma, secrecy, and race: An empirical examination of black and white incarcerated men. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2009;34:131–150. [Google Scholar]