Abstract

Salmonella has a natural ability to target a wide range of tumors in animal models. However, strains used for cancer therapy have generally been selected only for their avirulence rather than tumor-targeting ability. To select Salmonella strains that are avirulent and yet efficient in tumor-targeting, a necessary criteria for clinical applications, we measured the relative fitness of 41,000 Salmonella transposon insertion mutants growing in mouse models of human prostate cancer and melanoma. Two classes of potentially safe mutants were identified. Class 1 mutants showed reduced fitness in normal tissues and unchanged fitness in tumors (e.g., mutants in htrA, SPI-2, and STM3120). Class 2 mutants showed reduced fitness in tumors and normal tissues (e.g., mutants in aroA and aroD). In a competitive fitness assay in human PC3 tumors growing in mice, class 1 mutant STM3120 had a fitness advantage over class 2 mutants aroA and aroD, validating the findings of the initial screening of a large pool of transposon mutants and indicating a potential advantage of class 1 mutants for delivery of cancer therapeutics. In addition, an STM3120 mutant successfully targeted tumors after intragastric delivery, opening up the oral route as an option for therapy administration.

Introduction

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is a facultative anaerobic bacterium that infects a wide variety of animal hosts and naturally accumulates in most solid murine tumors versus normal murine tissues at a ratio of 1000:1 (1). Avirulent Salmonella mutant strains have been used to directly kill tumors (2–4) or to deliver constitutively expressed therapeutic proteins to tumors in mouse models (5–7). The use of Salmonella promoters preferentially active in tumors (8) should further increase the specificity and hence the safety of therapeutic systems. Avirulent Salmonella mutants used in cancer therapy have typically impaired biosynthesis of aromatic compounds, purines, or amino acids and were generally selected for their avirulence. For example, an aroA aroD double mutant was used to deliver the Flt3 ligand to treat melanoma in mice and resulted in 50% tumor regression (7). It is possible that a different avirulent mutant that grows better in tumors might have resulted in more complete tumor regression. The mutant A1-R deficient in leucine and arginine biosynthesis was effective against breast, pancreatic cancer, and osteosarcoma in nude mice (4, 9, 10), yet AI-R mutation that contribute to tumor killing are unknown. Another Salmonella strain, VNP20009, has mutations in the purI and msbB genes resulting in modified purine biosynthesis and reduced septic shock potential. VNP20009 is widely used for delivery of cancer therapeutics in mice (11). However, it showed only moderate tumor-targeting when tested in clinical trials of human patients with metastatic melanoma (12). While some of these mutants have shown a therapeutic value in cancer, the true potential of Salmonella may fully be explored if all Salmonella mutants were tested individually; however this would be practically impossible, and prohibitively expensive. Here we describe a high-throughput fitness screening of Salmonella mutants in all non-essential genes to determine which mutants were the best at accumulating in tumors while being disabled for growth in normal tissues. Mutants with reduced fitness in normal tissues but unchanged fitness in tumors were identified and have potential use as cancer therapeutics.

Results and Discussion

Microarray analysis to determine fitness in normal tissues and tumors

A library of 41,000 Salmonella mutants containing mini-Tn5 transposon insertions was constructed and pooled. The pool was injected into six human prostate (PC3) and six melanoma (MDA-MB-435) tumors growing subcutaneously in nude mice, and injected intravenously into three tumor-free mice. Bacteria were recovered after two days from tumors and spleens, livers, and lungs of tumor-free mice.

During in vivo selection, defective mutants in genes contributing to fitness in the selective environment are lost from the pool. Differences in the mutant pool composition before (input pool) and after selection (output pool) can be detected using microarray hybridization: Transposons were used that carry the T7 promoter sequence, allowing the specific amplification of genomic sequences adjacent to each insertion, which are then mapped on the Salmonella genome using a gene microarray (Appendix-2A, 2B). The present study revealed two distinct classes of mutant phenotypes (Table 1 and Appendix-1).

Table 1. Microarray results indicating relative fitness.

Microarray analysis measured the relative fitness of each mutant in subcutaneous prostate tumors (PC3), melanoma tumors (MDA) and normal tissues (spleen, liver, and lung). Numbers reported are the log2 of intensity ratio experiment vs control. The loss of fitness is indicated in grey set at a log2 ratio of −1.5, unchanged fitness is white. Candidates in grey have a signal intensity that is at least 3-fold reduced in the output library compared to the input library.

| Class 1 mutants | Spleen | Liver | Lung | PC3 | MDA | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STM3118 | Operon located in SPI-3 | −2.2 | −2.4 | −1.8 | −1.6 | −1.7 | −1.8 | −2.6 | −2.2 | −3.4 | 1.1 | −1.0 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −2.1 | −0.4 | −0.7 | −1.1 | −0.9 |

| STM3119 | −1.5 | −2.3 | −2.6 | −2.4 | −0.6 | −1.7 | −2.2 | −2.8 | −3.1 | −1.5 | 0.3 | −0.3 | −1.3 | −1.5 | 1.2 | −0.3 | −1.0 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −0.8 | 0.8 | |

| STM3120 | −0.4 | −1.1 | −1.6 | −1.6 | −1.2 | −0.9 | −3.3 | −1.1 | −2.7 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.3 | −0.6 | 2.1 | −0.4 | −0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | −0.3 | |

| STM3121 | −1.3 | −0.8 | −0.9 | −2.3 | −2.8 | −1.7 | −2.9 | −1.9 | −2.8 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.0 | −1.1 | −0.4 | −0.2 | −1.4 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −0.7 | −0.8 | −0.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ssrA | SPI-2 Type III Secretion system | −2.1 | −1.8 | −3.4 | −2.1 | −3.0 | −2.7 | −2.9 | −3.6 | −4.0 | 1.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | −0.2 | −0.4 | −0.7 | −0.3 | −1.1 | 0.4 | −0.2 |

| ssaB | −1.7 | −1.9 | −1.9 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −2.5 | −3.0 | −0.4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | −0.7 | −0.6 | −0.9 | −1.3 | −1.0 | −0.8 | −1.3 | −0.8 | |

| ssaC | −2.6 | −3.3 | −3.5 | −2.5 | −2.8 | −3.1 | −3.7 | −4.7 | −4.0 | −0.5 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −0.3 | −1.2 | −2.0 | −0.6 | −1.6 | −0.9 | −0.6 | |

| ssaD | −2.9 | −3.4 | −3.9 | −2.6 | −2.9 | −3.3 | −3.3 | −3.9 | −3.6 | −0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −0.2 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.2 | 0.0 | −0.6 | −2.4 | 0.5 | −0.2 | |

| sseB | −2.7 | −2.5 | −3.0 | −2.7 | −2.2 | −2.8 | −2.8 | −3.8 | −3.7 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.4 | −2.5 | −0.9 | −0.1 | |

| sscA | −2.3 | −2.3 | −3.6 | −1.9 | −2.6 | −1.6 | −3.1 | −4.5 | −4.2 | 1.2 | −1.0 | −0.5 | −0.8 | 1.2 | −0.2 | −1.5 | −1.4 | −0.1 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −0.1 | |

| sseC | −1.9 | −2.4 | −3.1 | −1.9 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −2.4 | −3.6 | −2.2 | −0.9 | −0.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 | −0.3 | −0.7 | −0.2 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 1.4 | −0.1 | |

| sseE | −1.1 | −1.7 | −2.7 | −1.2 | −0.8 | −1.7 | −1.8 | −2.3 | −3.7 | −0.6 | 1.1 | −0.2 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −1.6 | −0.7 | −0.9 | |

| ssaJ | −3.1 | −3.3 | −3.6 | −3.2 | −2.9 | −2.7 | −3.7 | −5.1 | −4.8 | −0.4 | 0.7 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.7 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −2.0 | −1.9 | −0.1 | |

| STM1410 | −2.6 | −2.8 | −2.8 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −2.1 | −4.4 | −5.6 | −5.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.5 | 0.4 | −0.2 | −0.9 | −0.1 | −1.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| ssaK | −2.4 | −2.8 | −3.5 | −2.1 | −3.1 | −2.3 | −3.3 | −3.4 | −4.6 | NA | −1.4 | 0.7 | −0.9 | −1.2 | −0.4 | −1.1 | −1.6 | −0.7 | −1.7 | −2.0 | −0.4 | |

| ssaL | −2.8 | −3.3 | −2.7 | −2.5 | −3.5 | −2.8 | −3.1 | −4.8 | −4.4 | −0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | −0.5 | −1.0 | −0.3 | −0.6 | −1.1 | −1.2 | −0.8 | −1.3 | −1.0 | |

| ssaM | −2.1 | −2.5 | −2.6 | −2.4 | −2.7 | −2.0 | −2.7 | −3.0 | −4.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | −0.4 | 0.3 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −1.5 | −0.6 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −0.5 | |

| ssaV | −3.0 | −3.1 | −4.0 | −2.8 | −3.3 | −3.5 | −3.4 | −4.4 | −4.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | −0.2 | −0.7 | −2.1 | −0.7 | −3.6 | 0.1 | −0.1 | |

| ssaN | −3.2 | −3.3 | −4.3 | −3.5 | −3.2 | −3.7 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 | −0.1 | 0.2 | −0.7 | −2.4 | −0.5 | 1.5 | −1.4 | −0.2 | |

| ssaP | −2.6 | −3.1 | −3.9 | −2.8 | −2.6 | −3.1 | −3.4 | −4.7 | −4.7 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.7 | 0.1 | −1.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

| ssaQ | −1.8 | −2.6 | −3.5 | −3.1 | −3.3 | −4.1 | −3.1 | −4.3 | −4.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −1.8 | 0.1 | −0.8 | 0.9 | −0.3 | |

| yscR | −1.6 | −2.0 | −2.4 | −1.8 | −1.8 | −1.2 | −2.8 | −3.2 | −3.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.9 | 0.1 | |

| ssaT | −3.2 | −2.9 | −3.1 | −2.8 | −3.5 | −2.5 | −3.5 | −4.3 | −4.3 | 0.7 | −1.3 | −1.3 | 0.2 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −1.4 | −2.1 | −2.1 | −1.0 | −2.0 | −1.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| htrA | Others | −1.6 | −2.3 | −1.5 | −1.8 | −2.1 | −1.3 | −1.8 | −2.1 | −1.0 | −0.5 | −1.0 | −0.4 | −0.9 | 0.5 | −0.7 | −1.0 | −1.1 | −0.3 | −1.4 | 0.0 | −0.5 |

| STM0278 | −2.2 | −0.7 | −1.9 | −1.2 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −1.5 | −2.2 | −3.2 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −1.1 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −1.2 | −0.7 | −0.9 | 0.1 | −0.8 | −0.4 | ||

| cyoA | −0.7 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −0.7 | −1.5 | −0.9 | −2.1 | −1.9 | −2.0 | −0.6 | −1.6 | −0.2 | −0.4 | −0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −1.0 | 0.8 | |

| sdhA | −0.6 | −0.8 | −1.3 | −1.6 | −1.5 | −0.7 | −2.4 | −3.7 | −2.1 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 1.8 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | −0.3 | 1.8 | |

| sifA | −1.4 | −1.9 | −2.0 | −1.2 | −1.8 | −1.6 | −1.9 | −2.3 | −1.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | −0.7 | −0.3 | −0.8 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −1.3 | −0.7 | −3.4 | −0.7 | −0.5 | |

| phoP | −3.0 | −4.1 | −4.2 | −4.0 | −4.7 | −3.7 | −4.7 | −5.2 | −5.2 | −0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | −1.3 | 1.8 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −2.4 | −0.9 | −1.4 | 0.2 | −0.6 | |

| sufA | −0.2 | −0.9 | −1.9 | −1.6 | −1.8 | −1.8 | −0.1 | −2.1 | −2.0 | −1.5 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −1.4 | −1.1 | 1.8 | −1.3 | 1.5 | −0.6 | 0.1 | −1.2 | 0.6 | |

| yebC | −1.9 | −1.2 | −2.6 | −0.4 | −2.4 | −1.2 | −0.6 | −2.1 | −2.0 | −0.8 | −0.4 | 0.0 | −1.4 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.7 | 3.6 | −0.8 | −1.0 | |

| srlR | 0.0 | −0.5 | −0.9 | −2.1 | −1.9 | 0.0 | −1.8 | −2.0 | −2.3 | NA | 0.3 | −0.9 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.2 | −0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | −0.2 | 0.4 | |

| purH | 0.5 | −0.3 | −1.4 | −2.0 | −2.6 | −0.7 | −2.5 | −1.6 | −3.9 | 0.2 | −0.3 | −0.5 | −1.0 | 1.1 | −2.0 | −1.4 | −0.9 | −0.8 | 2.2 | 0.1 | −0.3 | |

| STM4262 | −0.6 | −0.7 | −1.6 | −1.6 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −1.7 | −1.9 | −2.2 | −0.9 | −0.6 | −1.2 | −0.3 | −0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 | −0.8 | −0.5 | |

| mgtC | −2.4 | −1.7 | −2.4 | −2.3 | −1.4 | −1.6 | −2.2 | −1.8 | −2.3 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −1.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.8 | −1.2 | −1.1 | 0.2 | −1.3 | −1.7 | −0.6 | |

| wzzE | −1.8 | −1.0 | −3.0 | −2.0 | −2.6 | −0.8 | −2.6 | −2.3 | −3.4 | NA | −2.2 | −1.1 | −2.0 | −0.2 | −2.0 | −1.2 | −1.3 | 1.8 | −0.9 | −1.0 | −1.4 | |

| trkH | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −1.4 | −1.9 | −0.9 | −1.7 | −2.3 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −1.9 | −1.0 | −1.4 | −1.2 | −0.9 | −0.4 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| asmA | −0.9 | −1.7 | −1.8 | −1.5 | −2.7 | −2.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −0.8 | −1.2 | −0.1 | −1.1 | −1.5 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −0.8 | −0.7 | 0.2 | −0.5 | −0.2 | |

| sixA | −0.3 | −0.9 | −1.7 | −1.9 | −1.4 | −1.0 | −1.6 | −2.5 | −2.1 | −0.1 | −1.3 | −1.0 | −0.5 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.6 | −1.0 | |

| ubiB | −1.8 | −2.4 | −1.9 | 4.2 | −2.9 | −3.1 | −3.4 | −2.3 | −1.6 | −0.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −1.5 | 0.0 | −1.9 | −0.7 | −1.1 | −2.6 | −1.3 | |

| STM4258 | −2.1 | −1.6 | −1.7 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −1.1 | −1.8 | −1.9 | −2.3 | −0.8 | 0.8 | −2.4 | −0.6 | −0.8 | −0.9 | −1.2 | −0.8 | −1.7 | −0.5 | −1.5 | −1.1 | |

| Class 2 mutants | Spleen | Liver | Lung | PC3 | MDA | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tatA | Tat Operon | −2.6 | −2.6 | −2.5 | −2.3 | −3.0 | −1.0 | −3.3 | −3.5 | −3.2 | −1.8 | −1.4 | −2.7 | −1.8 | −0.8 | −1.5 | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.5 | −0.5 | −1.9 | −1.9 |

| tatB | −2.1 | −2.8 | −2.4 | −2.6 | −3.3 | −2.2 | −3.9 | −3.0 | −4.8 | −2.0 | −2.5 | −2.4 | −1.6 | −1.8 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −1.9 | −1.4 | −0.9 | −1.5 | |

| tatC | −1.8 | −1.9 | −2.1 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −2.0 | −2.4 | −3.3 | −3.1 | −1.6 | −2.0 | −1.5 | −1.2 | −1.5 | −0.6 | −1.6 | −0.9 | −1.7 | −0.3 | −1.8 | −0.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| rfbM | LPS | −2.9 | −3.3 | −3.6 | −3.1 | −3.8 | −2.4 | −3.9 | −4.3 | −4.0 | −2.7 | −3.2 | −3.2 | −3.1 | −2.6 | −3.1 | −2.6 | −1.5 | −2.2 | −1.8 | −2.5 | −2.2 |

| rfbK | −3.3 | −3.4 | −3.0 | −2.7 | −2.7 | −2.8 | −2.9 | −3.0 | −2.8 | −2.3 | −3.3 | −2.5 | −0.8 | −2.9 | −1.9 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −2.7 | −2.4 | ||

| rfbC | −3.0 | −0.9 | −0.6 | −2.6 | −1.9 | −1.9 | −3.0 | −2.1 | −4.0 | −3.4 | −3.7 | −3.6 | −2.3 | −1.9 | −1.0 | −0.8 | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.3 | 0.3 | −1.7 | |

| rfbA | −2.2 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −2.5 | −1.9 | −1.3 | −2.4 | −2.0 | −3.1 | −2.5 | −1.2 | −2.1 | −1.4 | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.7 | −1.1 | −0.9 | −0.4 | −1.1 | −1.7 | |

| rfbI | −1.5 | −1.3 | −2.0 | −1.7 | −2.3 | −1.3 | −2.6 | −2.5 | −2.8 | −1.5 | −1.8 | −1.8 | −1.3 | −1.8 | −1.3 | −1.0 | −0.3 | −1.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | −0.7 | |

| rfbD | −0.9 | −2.2 | −0.1 | −2.3 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −2.3 | −1.5 | −3.6 | −1.7 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −1.7 | −2.8 | −0.7 | −1.7 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −1.2 | 1.4 | −0.8 | |

| rfaB | −2.9 | −3.6 | −3.8 | −1.9 | −2.4 | −2.9 | −3.1 | −3.5 | −2.9 | −0.8 | −2.1 | −1.9 | −0.5 | −0.9 | −1.2 | −0.8 | −1.7 | −0.9 | −2.5 | −2.0 | −1.5 | |

| rfaJ | −0.5 | −1.4 | −0.7 | −1.8 | −1.8 | −0.6 | −2.2 | −2.5 | −2.4 | −1.9 | −1.0 | −1.8 | −1.2 | −0.9 | −0.3 | −0.8 | 1.2 | −0.5 | 2.2 | 0.6 | −0.5 | |

| rfaQ | −1.7 | −2.4 | −2.4 | −1.3 | −1.6 | −1.5 | −0.7 | −0.8 | −2.8 | −2.9 | −3.1 | −2.6 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −1.6 | −2.4 | −1.4 | −1.9 | −1.7 | −2.7 | −1.9 | |

| rfaI | −1.1 | −1.1 | −1.8 | −1.5 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −3.1 | −2.0 | −3.0 | −1.5 | −1.4 | −2.0 | −1.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.0 | −0.4 | 0.4 | −0.8 | −0.7 | |

| rfaK | −2.6 | −2.4 | −1.2 | −1.7 | −1.5 | −1.4 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −1.5 | −1.3 | −3.1 | −0.3 | −0.8 | −1.4 | −0.8 | −2.1 | −1.3 | −0.7 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| aroD | Others | −3.7 | −3.4 | −3.4 | −3.4 | −3.3 | −3.3 | −2.1 | −1.7 | −2.8 | −0.8 | −1.7 | −2.0 | −3.0 | −2.8 | −3.2 | −3.2 | −2.8 | −1.9 | −3.2 | −3.2 | −2.8 |

| aroA | −2.6 | −2.3 | −2.8 | −2.7 | −3.5 | −2.8 | −3.4 | −4.1 | −3.9 | −2.1 | −2.7 | −1.5 | −2.1 | −1.9 | −1.7 | −1.6 | −0.5 | −0.9 | −1.0 | −1.4 | −1.6 | |

| sapA | −1.9 | −1.6 | −2.1 | −1.3 | −2.0 | −0.7 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −0.8 | −0.3 | −2.2 | −1.4 | −1.2 | −2.0 | −1.4 | −1.9 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.7 | −1.9 | −1.3 | |

| yhbT | −1.6 | −1.7 | −1.9 | −1.7 | −0.3 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −1.9 | −0.8 | −0.6 | −1.9 | −2.1 | −1.5 | −1.8 | −2.0 | −0.9 | −1.8 | −1.4 | −0.4 | −2.0 | ||

| STM3357 | −2.2 | −0.9 | −2.2 | −1.5 | −0.9 | −2.0 | −0.4 | −1.6 | −0.9 | −2.0 | −4.5 | −1.9 | −1.6 | −2.5 | −1.8 | −0.8 | −1.4 | −1.8 | 0.4 | −2.9 | −1.7 | |

| mtlD | −1.0 | −1.3 | −2.0 | −1.1 | −2.2 | −1.7 | −0.3 | −2.1 | −1.9 | −2.2 | −1.8 | −2.7 | −2.4 | −0.8 | −1.2 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −1.5 | −0.1 | −2.2 | −1.8 | |

| pfkA | −1.8 | −2.1 | −1.8 | −2.1 | −2.7 | −1.2 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −0.7 | −2.5 | −2.7 | −2.3 | −2.0 | −1.8 | −0.7 | −1.0 | −1.8 | −0.9 | −1.7 | −1.3 | ||

| trxA | −1.9 | −2.7 | −2.9 | −1.7 | −2.3 | −0.9 | −3.8 | −4.1 | −3.4 | −1.7 | −2.2 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −1.4 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.0 | −1.4 | −0.6 | −2.1 | −1.7 | |

| manA | −2.4 | −2.8 | −2.4 | −3.1 | −3.3 | −1.7 | −2.6 | −3.6 | −2.4 | −0.9 | −1.4 | −3.0 | −2.5 | −2.0 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −0.1 | −1.6 | −2.1 | −1.5 | ||

Class 1 mutants

This class contains mutants with reduced fitness in normal tissues (spleen, liver and lung) and unchanged fitness in tumors. We identified mutants affecting at least 19 distinct genes within the SPI-2 island (i.e., ssrA, ssaB, ssaC, ssaD, sseB, sscA, sseC, sseE, ssaJ, STM1410, ssaK, ssaL, ssaM, ssaV, ssaN, ssaP, ssaQ, yscR and ssaT). In addition, mutants in genes involved in a number of cellular functions were identified (Table 1). These include htrA, phoP, sifA and a hypothetical operon composed of a putative acetyl-CoA hydrolase (STM3118), a putative monoamine oxidase (STM3119) and two putative transcriptional regulators (STM3120 and STM3121). Many of these mutants have previously been observed to be associated with fitness in spleen (13, 14). The observation of a similar effect on fitness in liver and lung is new but not unexpected. The fact that these mutants remain fit in tumors relative to other mutants is of potential practical importance for Salmonella use as a therapeutic delivery vector.

Class 2 mutants

This class contains mutants with reduced fitness both in normal and tumor tissues. Three mutants of the same operon involved in the synthesis of aromatic compounds were identified: aroM, aroD and aroA. Previous reports describe the use of aroA and aroD mutants in cancer therapy (7, 15, 16). Mutants in genes related to lipopolysacharide biosynthesis were also identified in this class (e.g., rfbK, rfbM, rfbC, rfaQ). While class 2 mutants are either avirulent or of reduced virulence, their impaired growth in tumors relative to class 1 mutants make them less suitable for cancer therapy. The ability of mutants to directly kill tumors was not tested because our screen was designed only to identify mutants with reduced fitness in spleen but unchanged or improved fitness in tumors. Regardless of any ability to kill tumors, such mutants will be able to deliver and express therapeutics under the control of tumor-specific promoters.

Virulence assay of specific knockout mutants in immuno-competent mice

We constructed individual gene knockouts of class 1 and class 2 Salmonella genes using the Lambda-Red recombination technique (17). These deletion mutants were tested for virulence in immuno-competent mice. Each mutant was injected (105 cfu) intravenously into five C57BL/6 mice, which are particularly sensitive to Salmonella infection, and are thus a stringent test of virulence. Additional deletions were made in three genes that had no observable fitness phenotype in our microarray screen and used as controls (STM1459, ybjN and feoB). Each mutant strain was assigned to one of three categories based on virulence level: virulent, mildly attenuated, or severely attenuated (Table 2). Virulent strains cause distress, dehydration and death within 2 days post inoculation, which was observed with all three control mutants. In contrast, class 1 and class 2 mutants were either mildly or severely attenuated. Exposure to the mildly attenuated mutants STM3119, rfbI, rfaQ, rfbK, rfbM, sifA and phoP caused signs of distress 2 to 6 days post inoculation (Table 2). The C57BL/6 strain of mouse also presents similar symptoms within 2 days following the same dose of wild-type Salmonella administration (data not shown). All other mutants were severely attenuated and did not cause any distress during the 2-week experiment. These strains include SPI-2, htrA, STM3120, aroA and aroD (Table 2). Assays with SPI-2 and STM3120 mutants were repeated three times, each with five mice. No signs of distress or death were observed for four weeks, after which all mice were sacrificed.

Table 2. Virulence of Salmonella mutants in C57BL/6 mice.

Sixteen mutants (class 1 and class 2) were selected by the microarray data and evaluated for virulence in immuno-competent mice. Microarray phenotype: NT = reduced fitness in normal tissues; TUM = reduced fitness in tumors.

| Panel A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella mutant strains | Microarray phenotype | Mouse survival time | In vivo virulence |

| STM1459 | Unchanged fitness | 1–2 days | Virulent |

| ybjN | Unchanged fitness | ||

| feoB | Unchanged fitness | ||

| STM3119 | NT | 2–6 days | Mildly attenuated |

| rfbI | NT / TUM | ||

| rfaQ | NT / TUM | ||

| rfbK | NT / TUM | ||

| rfbM | NT / TUM | ||

| phoP | NT | ||

| sifA | NT | ||

| SPI-2 | NT | Survival | Severely attenuated |

| htrA | NT | ||

| STM3120 | NT | ||

| aroA | NT / TUM | ||

| aroD | NT / TUM | ||

| Panel B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class of mutants | Fitness in tumors | Fitness in normal tissues | Examples |

| Class 1 | Unchanged | Reduced | STM3120, STM3119, SPI-2, htrA, phoP, sifA |

| Class 2 | Reduced | Reduced | aroA, aroD, aroM, rfbK, rfbM, rfaQ, rfbI |

| Control mutants | Unchanged | Unchanged | STM1459, ybjN and feoB |

In summary, fitness assays on pools of mutants can be used as a primary screen for candidate attenuated mutants while simultaneously monitoring the relative ability to survive in tumors. The ability to screen thousand of candidates and evaluate individual mutants in parallel using arrays and, in the future, high-throughput sequencing, offers a clear advantage over conventional screening methods.

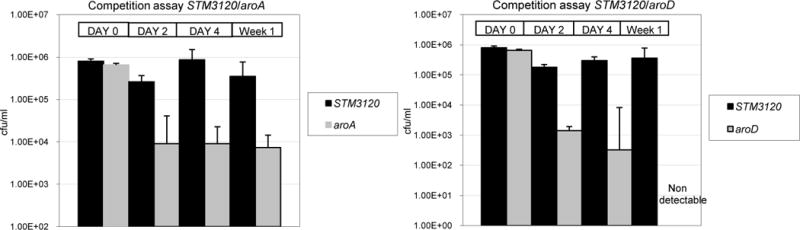

Competitive fitness assay in nude mice bearing human prostate tumors

The competitive fitness of the class 1 mutant STM3120 in the tumor environment was tested in vivo against the class 2 mutants aroD and aroA. Input bacterial mixes were prepared in an approximately 1:1 ratio of STM3120 to aroD or aroA. Approximately 106 cfu of the mixture were injected into human PC3 tumors growing subcutaneously in nude mice. Input ratios were compared with output ratios recovered from tumor biopsies 2, 4, and 7 days after injection.

Two days after injection, the level of viable aroD mutants was 2 logs lower than that of STM3120. After 1 week, aroD was undetectable whereas STM3120 counts increased slightly. When STM3120 was competed against aroA, the aroA count was initially reduced by about two logs 2 days following injection but maintained the same level 1 week after injection (1 to 2 logs less than STM3120). These results suggest that STM3120 outcompeted aroD to a greater extent than it outcompeted aroA (Figure 2), consistent with the microarray data showing that aroA is more fit in tumors than aroD, but not as fit as STM3120 (Table 1).

Tumor-targeting of STM3120 mutants using syngeneic orthotopic 4T1 breast tumors

The tumor-targeting capability of STM3120 was tested into five 6-week old BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 breast tumors grown orthotopically for 10 days. Mice were gavaged with 7 × 108 cfu of STM3120, tumor biopsies were taken 2, 5, 7 and 9 days later (http://www.gallinimedical.com) and bacterial counts determined. Bacteria were detected in three mice 7 days after administration. At day 9, bacterial counts ranged from 2 × 104 to 9 × 105 cfu per biopsy in all 5 mice (Table 3).

Table 3. Growth of STM3120 mutant in orthotopic 4T1 breast tumors after intragastric delivery.

Numbers represent cfu per biopsy per mouse taken at different days following injection. Dash indicates a level of bacteria below detection.

| mouse | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | |||||

| 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | – | 2.00E+05 | 1.25E+02 | 4.00E+05 | – |

| 9 | 3.00E+04 | 7.50E+05 | 5.00E+04 | 9.00E+05 | 2.00E+04 |

These results suggest that intragastric delivery of STM3120 allows a sufficient number of bacteria (~107 – 5 × 108 cfu per tumor) to target and multiply in the tumor environment to levels previously shown to effectively reduce tumor size after intratumoral or intravenous injection (11). This is of importance because intragastric delivery of a therapeutic strains may offer improved safety over intravenous delivery. A similar finding was recently made by Jia and coworkers (18), showing a significant anticancer effect of orally administered VNP20009 to mice bearing syngeneic subcutaneous B16F10 melanoma and Lewis lung carcinoma. Tumor-targeting after oral delivery to BALB/c mice is likely due to the ability of Typhimurium to produce a typhoid-like systemic infection in this mice strain. The ability to efficiently enter the bloodstream of humans after oral delivery may require additional engineering or the use of strains that are naturally efficient at this transition such as Typhi strain Ty21.

The original screenings lasted only 2 days, time necessary to ensure sufficient complexity in the mutant library without random loss of mutants that would confound the high-throughput analysis. As a result mutant such as STM3120 were selected based on the fitness phenotype not the tumor killing targeting. Nevertheless, we did occasionally see necrosis in tumors, likely associated with the injection of STM3120.

We have shown that high-throughput screening of a pool of transposon mutants allows the identification of novel Salmonella mutants with potential therapeutic value and the re-evaluation of those previously used in cancer therapy. Mutants that retain tumor-targeting while being poor colonizers of normal tissue are candidates for delivery of cancer therapeutics. However, mutants will need to be tested in the intended host before the best candidates can be determined. Such approaches can be adapted to any host and tumor model and a wide variety of bacterial species.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

Specific knockout mutants described in Table 2 were generated in the S. typhimurium strain 14028 background using the Lambda-Red recombination method, with modifications (14). A transposon library in 14028 was constructed using the EZ-Tn5™ <T7/KAN-2> kit (Epicenter). The library had ~41,000 kanamycin-resistant mutants.

Animal experiments

PC3 human prostate and human MDA-MB-435 recently redefined as melanoma, were grown in nude mice by injecting ~106 cancer cells subcutaneously. In the 4T1 breast syngeneic model, 4T1 tumors were grown in BALB/c immuno-competent mice by injecting 2 × 106 cells at the second mammary gland on the right side.

Sample preparation for the microarray and data analysis

A frozen aliquot of the initial library was used to inoculate 100 ml of LB. After overnight growth, bacteria (input library) were pelleted, washed three times with PBS and 107 cfu injected intratumorally into twelve 6-week old nude mice (six mice bearing subcutaneous human PC3 prostate, six mice bearing subcutaneous human MDA-MB-435 melanoma) and intravenously into three tumor-free nude mice. Two days after injection, tumors and normal tissues (spleen, liver and lung) from tumor-free mice were recovered and homogenized in PBS. An aliquot was plated on kanamycin-containing LB plates to determine the cfu. The remainder of the sample was added to kanamycin-containing LB and incubated overnight at 37°C (output libraries). The DNA adjacent to transposon insertions in library samples was amplified as described (14), with the following modifications: PCR amplifications were carried out using primers DOPR2 (CAACGCAGACCGTTCCGTGGCA) and CCT24VN (CCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTVN). Nested PCR amplifications were carried out using primers CCT24VN and KAN2FP1-B (GTCCACCTACAACAAAGCTCTCATCAACC). Further details of the experimental method and data analysis are presented in Appendix-2A, 2B.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Competitive fitness assays in human PC3 tumors.

In panel A, STM3120 was competed against aroD. In panel B, STM3120 was competed against aroA. Numbers represent cfu per tumor per mouse taken at different days following injection; three biological replicates were used for cfu counting at each time point.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by NIH grants R01AI034829, R01AI052237, R21AI057733 to MM, TRDRP 16KT-0045 to NA, and DOD grant W81XWH-06-1-0117 to MM. CAS is supported by grant ADI-08/2006 from PBCT-CONICYT (Chile) and The World Bank. We thank Steffen Porwollik, Brian Ahmer, and Helene Andrews-Polymenis for helpful discussions, Rocio Canals for help with library construction, and Charlene Cooper for her support and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors are pursuing the commercial application of engineered infectious agents to cancer therapeutics.

Accession numbers: microarray hybridization data are accessible as GSE19609 at the GEO depository of the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

References

- 1.Pawelek JM, Low KB, Bermudes D. Tumor-targeted Salmonella as a novel anticancer vector. Cancer research. 1997;57(20):4537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avogadri F, Martinoli C, Petrovska L, et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on killing of Salmonella-infected tumor cells. Cancer research. 2005;65(9):3920–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett SJ, Soto LJ, 3rd, Sorenson BS, Nelson BW, Leonard AS, Saltzman DA. Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium invades and decreases tumor burden in neuroblastoma. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005;40(6):993–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.015. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao M, Yang M, Ma H, et al. Targeted therapy with a Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer research. 2006;66(15):7647–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weyel D, Sedlacek HH, Muller R, Brusselbach S. Secreted human beta-glucuronidase: a novel tool for gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Gene therapy. 2000;7(3):224–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galen JE, Zhao L, Chinchilla M, et al. Adaptation of the endogenous Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi clyA-encoded hemolysin for antigen export enhances the immunogenicity of anthrax protective antigen domain 4 expressed by the attenuated live-vector vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA. Infection and immunity. 2004;72(12):7096–106. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7096-7106.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon WS, Choi WC, Sin JI, Park YK. Antitumor therapeutic effects of Salmonella typhimurium containing Flt3 Ligand expression plasmids in melanoma-bearing mouse. Biotechnology letters. 2007;29(4):511–6. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrach N, Zhao M, Porwollik S, Hoffman RM, McClelland M. Salmonella promoters preferentially activated inside tumors. Cancer research. 2008;68(12):4827–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi K, Zhao M, Yamauchi K, et al. Systemic targeting of primary bone tumor and lung metastasis of high-grade osteosarcoma in nude mice with a tumor-selective strain of Salmonella typhimurium. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2009;8(6):870–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagakura C, Hayashi K, Zhao M, et al. Efficacy of a genetically-modified Salmonella typhimurium in an orthotopic human pancreatic cancer in nude mice. Anticancer research. 2009;29(6):1873–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bermudes D, Zheng LM, King IC. Live bacteria as anticancer agents and tumor-selective protein delivery vectors. Current opinion in drug discovery & development. 2002;5(2):194–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toso JF, Gill VJ, Hwu P, et al. Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):142–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan K, Kim CC, Falkow S. Microarray-based detection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium transposon mutants that cannot survive in macrophages and mice. Infection and immunity. 2005;73(9):5438–49. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5438-5449.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santiviago CA, Reynolds MM, Porwollik S, et al. Analysis of pools of targeted Salmonella deletion mutants identifies novel genes affecting fitness during competitive infection in mice. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5(7):e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentschev I, Fensterle J, Schmidt A, et al. Use of a recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain expressing C-Raf for protection against C-Raf induced lung adenoma in mice. BMC cancer. 2005;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paglia P, Terrazzini N, Schulze K, Guzman CA, Colombo MP. In vivo correction of genetic defects of monocyte/macrophages using attenuated Salmonella as oral vectors for targeted gene delivery. Gene therapy. 2000;7(20):1725–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(12):6640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia LJ, Wei DP, Sun QM, Huang Y, Wu Q, Hua ZC. Oral delivery of tumor-targeting Salmonella for cancer therapy in murine tumor models. Cancer science. 2007;98(7):1107–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.