Abstract

Limitations of current clinical methods for bone repair continue to fuel the demand for a high strength, bioactive bone replacement material. Recent attempts to produce porous scaffolds for bone regeneration have been limited by the intrinsic weakness associated with high porosity materials. In this study, ceramic scaffold fabrication techniques for potential use in load-bearing bone repairs have been developed using naturally derived silk from Bombyx mori. Silk was first employed for ceramic grain consolidation during green body formation, and later as a sacrificial polymer to impart porosity during sintering. These techniques allowed preparation of hydroxyapatite (HA) scaffolds that exhibited a wide range of mechanical and porosity profiles, with some displaying unusually high compressive strength up to 152.4 ± 9.1 MPa. Results showed that the scaffolds exhibited a wide range of compressive strengths and moduli (8.7 ± 2.7 MPa to 152.4 ± 9.1 MPa and 0.3 ± 0.1 GPa to 8.6 ± 0.3 GPa) with total porosities of up to 62.9 ± 2.7% depending on the parameters used for fabrication. Moreover, HA-silk scaffolds could be molded into large, complex shapes, and further machined post-sinter to generate specific three-dimensional geometries. Scaffolds supported bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell attachment and proliferation, with no signs of cytotoxicity. Therefore, silk-fabricated HA scaffolds show promise for load bearing bone repair and regeneration needs.

1.0 Introduction

It is estimated that by the year 2020 approximately 6.6 million orthopedic surgeries will be performed annually [1]. Many of these operations will aim to repair “critical-sized” bone defects that result from traumatic fracture, osteosarcoma, or congenital malformation, and have lost regenerative capacity [2]. Growing concerns over the complications of autografting (e.g. donor site morbidity, infection) and allografting (e.g. graft rejection), as well as the limited availability of these tissue repair options has prompted the development of porous scaffolds for bone defect repair [3–5].

Calcium phosphates (CaP), particularly hydroxyapatite (HA), have drawn attention for orthopedic applications due to their close semblance to the mineral phase and crystalline structure of bone [6, 7]. Owing to their biocompatibility and ability to be resorbed by the body, advancement in CaP scaffolding has accelerated over the past decade. Attempts at generating resorbable scaffolds for bone replacement have focused on achieving high porosity to promote cell infiltration and maintain oxygen and nutrient diffusion throughout the graft. Despite encouraging results, these efforts have been limited by the inherent weakness associated with increased porosity, which remains the fundamental limitation of bone tissue engineering [8]. Typical compressive strengths of porous ceramic scaffolds range from 5–40 MPa, which surpass the strength of human trabecular bone (2–10 MPa) but cannot match that of cortical bone (170–200 MPa), thereby restricting these scaffolds to non-load bearing bone repairs [7, 9–12]. Thus, there is an urgent need in the field of bone tissue engineering for ceramics fabrication techniques that can produce grafts to match load-bearing requirements. Ideally, fabrication methods should have flexible processing parameters to control mechanical and porosity profiles of the scaffold, and allow for the production of high strength grafts with complex geometry for patient-specific needs.

Recent advances in ceramics fabrication have employed a variety of synthetic (e.g. poly(lactide-co-glycolide), poly(methyl methacrylate), polycaprolactone) and natural (e.g. chitosan, alginate, starch, cellulose) binders and porogens to generate CaP scaffolds by methods such as foam casting, direct foaming, porogen burnout, freeze drying, slip casting, and gel casting [8, 13–20]. While each of these methods has unique benefits, significant disadvantages include the use of toxic initiators in solvent-based gel casting, low ceramic density in direct foaming or foam casting, or the use of harsh chemicals and organic solvents in fabricating synthetic porogens [18]. After molding, many of these techniques involve high-temperature sintering of the green body, the ceramic structure prior to sintering, to harden and densify the finished scaffold. Although sintering naturally decreases total pore volume, porosity can be maintained in a controlled manner with the introduction of a sacrificial polymer in the green body that burns off during sintering [21].

Over the past decade, the incorporation of polymeric additives in ceramic formulations has received much attention due to the fine control that porogens afford over the final scaffold properties [22]. Since total porosity and strength of a ceramic scaffold is a function of both macroporosity, from the addition of porogens, as well as microporosity, from the spaces between adjacent ceramic grains, optimal ceramic fabrication should involve ceramic grain consolidation during green body formation [9, 23]. This allows for greater contact between ceramic grains and improved grain fusion during sintering, resulting in high scaffold density in regions between macropores [24]. Since relative density is a critical determinant of mechanical performance in ceramics, grain consolidation during green body formation is imperative for the creation of high strength, load-bearing scaffolds [25, 26].

In this study we investigated the potential of silk as a biocohesive agent and a porogen in the fabrication of hydroxyapatite ceramic scaffolds. The aim of this work was to leverage the adhesive nature of the silk protein [27], its exceptional thermal stability [28, 29], and ability to form irreversible beta-sheet conformations in response to localized dehydration [30] to produce robust ceramic structures. We further assessed the potential of silk to generate hydroxyapatite scaffolds with a wide range of porosity and mechanical profiles.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Silkworm cocoons from B. mori were obtained from Tajima Shoji Co., LTD (Yokohama, Japan. Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), penicillin and streptomycin (Pen–Strep), Fungizone, nonessential amino acids (NEAA, consisting of 8.9 mg/l L-alanine, 13.21 mg/l L-asparagine, 13.3 mg/l L-aspartic acid, 14.7 mg/l L-glutamic acid, 7.5 mg/l glycine, 11.5 mg/l L-proline, 10.5 mg/l L serine), and trypsin were from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). All other chemicals of pharmaceutical grade were obtained from Sigma.

2.2 Preparation of B. mori silk fibroin

Bombyx mori silk fibroin solution was prepared as previously described [31]. Briefly, five grams of silk cocoons were boiled in two liters of an aqueous solution of 0.02 M sodium carbonate for either 20 or 60 minutes, rinsed with deionized water, and dried. The dry silk fibers were dissolved in a 9.3 M lithium bromide solution (25% wt/v) at 60°C for 4 to 6 hours, and the resulting solution was dialyzed against deionized water using 3500 Dalton molecular weight cut off dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) to remove the lithium bromide. The final concentration of the aqueous silk solution after dialysis was 6–8% wt/v, which was determined by massing the remaining silk solid after drying a known volume.

2.3 Preparation of concentrated silk solution, soluble silk powder, and silk macroporogens

Concentrated silk solution was prepared by dehydrating the 8% wt/v aqueous silk solution from 20-minute boiled silk fibroin in Slide-a-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (MWCO 3500) (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL) by air-drying for 4 to 6 hours with mixing by inversion of the cassette. The final concentration of the concentrated silk solution was 15% wt/v. The concentrated solution was stored at 4°C until further use. Soluble silk powder was prepared by freezing the 8% wt/v aqueous silk solution from 60-minute boiled silk fibroin for 24 hours at −20°C, and lyophilizing (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) at a pressure of 0.020 Torr for 24 to 48 hours. After lyophilization, the resulting silk foams were ground and blended on high setting for two minutes in a conventional kitchen blender (Model KSB560, KitchenAid, Inc., St. Joseph, MI) with a cup size of approximately 1 L and stored at ambient conditions until further use. Silk macroporogens were prepared in the same manner as the soluble silk powder, except that, after lyophilization, the resulting silk foams were blended for only 30 seconds in a conventional kitchen blender to obtain larger silk particles. The particles were then placed in an open stage, closed-top sealed desiccator and solvent annealed by vapor from a separate 100% methanol source (approximately 200 mL) beneath the open stage for 24 hours. The resulting insoluble silk macroporogens (SMPs) were separated according to size using stainless steel particle sieves with mesh sizes of 800 μm and 300 μm (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) to generate a small particle fraction (less than 300 μm) and a large particle fraction (300 μm to 800 μm). SMPs were stored at ambient conditions until further use.

2.4 Preparation of hydroxyapatite scaffolds

Silk Solvent (SS) Method

Silk solution (15% wt/v) was mixed with HA powder in HA/silk mass ratios of 99/1, 90/10, and 80/20. Additional deionized (DI) water (approximately 1 mL per gram of HA-silk material) was added to the mixture to obtain a moldable HA-silk paste. The HA-silk mixture was kneaded by hand into a homogenous paste and subsequently molded into silicone molds (Dragon Skin, Smooth-On, Inc., Easton, PA) of any shape or geometry. For materials evaluation, small cylinders (ø = 10 mm, h = 10 mm) were formed. Molded green bodies were incubated at 60°C for 24 hours to render the silk insoluble in aqueous environments by inducing beta sheet formation. After 24 hours, the HA-silk green bodies were sintered in a Lindberg Blue-M Tube furnace (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 1300°C or 1400°C for 3 hours at maximum temperature with linear heating and cooling rates of 8°C per minute. Sintered scaffolds were stored at ambient conditions until testing.

Silk Powder (SP) Method

Soluble silk powder was mixed with HA powder in HA/silk mass ratios of 99/1, 90/10, and 80/20. Additional DI water (approximately 1 mL per gram of HA-silk material) was added to the mixture to obtain a moldable HA-silk paste. The HA-silk mixture was kneaded by hand into a homogenous paste and molded into silicone molds (ø = 10 mm, h = 10 mm). Molded green bodies were incubated in a 60°C oven for 24 hours to induce silk stabilization to render the silk insoluble in aqueous environments by inducing beta sheet formation. After 24 hours, the HA-silk green bodies were sintered in a Lindberg Blue-M Tube furnace at 1300°C or 1400°C for 3 hours at maximum temperature with linear heating and cooling rates of 8°C per minute. Sintered scaffolds were stored at ambient conditions until testing.

Silk Freeze-Drying (SFD) Method

Silk solution (15% wt/v) was mixed with HA powder in HA/silk mass ratios of 99/1, 90/10, and 80/20. Additional DI water (approximately 1 mL per gram of HA-silk material) was added to the mixture to obtain a moldable HA-silk paste. The HA-silk mixture was kneaded by hand into a homogenous paste and molded into silicone molds (ø = 10 mm, h = 10 mm). The molded green bodies were frozen at −20°C for 24 hours and then lyophilized at a pressure of 0.020 Torr for 24 to 48 hours to induce silk stabilization. After lyophilization, the HA-silk green bodies were sintered in a Lindberg Blue-M Tube furnace at 1300°C or 1400°C for 3 hours at maximum temperature with linear heating and cooling rates of 8°C per minute. Sintered scaffolds were stored at ambient conditions until testing.

Silk Macroporogens (SMPs)

SMPs could be added to any of the three silk-based fabrication methods (SS, SP, SFD). A 60% HA/40% silk ratio using the Silk Solvent Method was chosen in which 50% of the silk material by mass was replaced with SMPs. The SMPs were first mixed with the 15% wt/v concentrated 20-minute boiled aqueous silk solution. HA powder was then mixed into the silk-SMP mixture and additional DI water (approximately 1 mL per gram of HA-silk material) was added to the mixture to obtain a moldable HA-silk paste. The paste was kneaded by hand to achieve a homogenous paste and packed into silicone molds (ø = 10 mm, h = 10 mm). The green bodies were incubated in a 60°C oven for 24 hours to induce silk stabilization and then sintered in a Lindberg Blue-M Tube furnace at 1300°C or 1400°C for 3 hours at maximum temperature with linear heating and cooling rates of 8°C per minute. Sinter ed scaffolds were stored at ambient conditions until testing.

2.5 Characterization of ceramic scaffolds

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Phase composition of the sintered scaffolds (n = 2) was analyzed using a Scintag PAD-X powder x-ray diffractometer (Scintag, Inc., Cupertino, CA). X-rays were generated using a sealed glass Cu-Kα x-ray source (wavelength 1.54 Å; Advanced Technical Products & Services, Inc., Douglassville, PA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 45 kV and a beam current of 40 mA, using 1 mm divergent and 2 mm scatter slits, respectively. Diffracted intensities were measured using a Peltier cooled Si(Li) solid state detector with a 0.5 mm scatter slit and a 0.2 mm receiving slit. Samples were positioned on top of a zero background single crystal quartz plate (Gem Dugout, State College, PA) using wooden shims outside of the beam path to adjust sample height, and scanned at a rate of two degrees per minute.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Structural morphology of the sintered scaffolds (n = 3) was visualized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM Ultra55, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Dry samples (ø = 5 mm, h = 5 mm) were carefully fractured with a chisel and mallet, and the inner surfaces of the scaffolds were sputter coated (SC7620 mini sputter coater, Quorum Technologies, Kent, UK) with gold and imaged at a voltage of 5 kV.

Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT)

Sintered scaffolds (n = 1) were imaged using an X-Tek Micro-CT (Xtek, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV and a beam current of 135 mA with a one second exposure and 25X magnification.

Total porosity and mean pore size

Total porosity of the sintered scaffolds was measured with three different methods. Liquid displacement was used with 100% ethanol as the displacement medium because it easily penetrates the pores of the scaffold and does not induce shrinking or swelling. Samples (n = 6) were first thoroughly dried at 60°C overnight. A dry sample of mass (M) was immersed in a graduated cylinder containing a known volume (V1) of ethanol. The samples were subjected to a series of evacuation-depressurization cycles to completely displace any entrapped air with ethanol. The total volume of the ethanol with the submerged scaffold was recorded (V2). The volume of the scaffold skeleton was determined as the volume difference V2−V1. The ethanol-soaked scaffolds were then removed from the graduated cylinder and the residual ethanol in the cylinder was recorded (V3). The total volume (Vtot) of the scaffold was calculated using the following expression:

The fraction of open pores (δ) in the scaffold was then determined using the expression:

Scanning electron microscopy imaging was used as a second method to analyze porosity. SEM imaging of fractured CaP samples (n = 3) was performed as described above. ImageJ software analysis was used to measure both mean pore diameter and total porosity. The diameter of five randomly selected pores was measured in three separate regions of the scaffold interior and averaged for each sample (n = 3). Total porosity was measured using the particle size analyzer macroinstruction in ImageJ. The macro detects particles by intensity thresholding, applying size and shape exclusion criteria, and calculating the area fraction of porosity (both macropores and micropores) within the image area. Three images at the same magnification taken in three different regions of the sample were analyzed for each scaffold (n = 3). Micro-computed tomography was the final method used to analyze porosity. Imaging was carried out as described above. Histograms of the grey scale values associated with each voxel in the image were analyzed to calculate and confirm the total percentage of air in each sample (n = 1).

Mechanical testing

Large hand-molded cylindrical green bodies (ø = 30 mm, h ≈ 15 mm) were sintered and cut using a 500 Watt 7″ × 16″ variable speed lathe (MicroLux True-Inch, Micro-Mark, Inc., Berkeley Heights, NJ) with a carbide-tipped tool bit to obtain smooth cylindrical samples for mechanical testing (n = 6). The specimens were machined to a diameter-to-height aspect ratio of 1:2. Each end of a blank was faced to a smooth finish and a final height of 20 mm ± 0.1 mm, and the diameter was turned down to 10 mm ± 0.1 mm. Compression tests were performed using an Instron 3366 (Instron, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) testing frame equipped with a 10 kN load cell. The dry sintered samples were not pre-conditioned prior to testing. Tests were conducted at a crosshead speed of 2 mm/min and load was applied until a strain of 10% was reached or until fracture occurred. The compressive modulus was calculated as the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curve.

2.6 Mesenchymal stem cell isolation and expansion

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMCSs) were isolated from fresh bone marrow aspirate (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) obtained from a single healthy, non-smoking male donor. Whole bone marrow cell isolate was plated at a density of 200,000 cells/cm2 in 175 cm2 flasks (Corning, Corning NY, USA). Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 ng/mL, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 ng/mL fungizone (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) was used for expansion. Flasks containing a total volume of 20 mL were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO 2, and low oxygen (5%), and rocked daily to keep hemopoietic cells in suspension and allow stromal cells to adhere to the flask. The adherent cells were allowed to reach 90% confluence at which point they were trypsinized, suspended in FBS containing 10% DMSO, frozen at −80°C, and later stored in liquid nitrogen. Prior to experimentation, cells were thawed, re-plated, and passaged one more time before use.

2.7 Cell culture

Cell adherence and proliferation assay

Sintered HA scaffolds (n = 5) approximately 5 mm height and 5 mm diameter were sterilized by autoclaving, and soaked in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin overnight prior to cell seeding. Passage 2 hMSCs were seeded at a density of 150,000 cells per scaffold in a volume matching the void volume of the scaffolds as measured by liquid displacement using 100% ethanol (approximately 10–30 μL). Samples were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C in 5% CO 2 before media was added, and then cultured over a 14-day period. Cell proliferation was monitored using Alamar blue assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol at specified time points of 1, 4, 8, and 12 days post-seeding. SMP-fabricated scaffolds were seeded in the presence of a fibrin gel. Fibrin was prepared by mixing human fibrinogen (10 mg mL−1) (EMD Millipore Chemicals, Billerica, MA) with human thrombin (5 U mL−1) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in a 4:1 volume ratio.

Cell viability and confocal microscopy

The viability of hMSCs in the scaffolds was examined by live/dead assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Scaffolds seeded with cells were washed with PBS (1X), cut in half, using gentle hammering and a razor blade, to image the scaffold center, incubated in 2 μM calcein AM to stain live cells and 4 μM ethidium homodimer to stain dead cells for 45 minutes at room temperature, and washed again prior to imaging. Fluorescent images of both the surface and interior of the stained samples were obtained using a Leica DMIRE2 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with Argon (488 nm) and HeNe (543 nm) lasers (Leica Microsystems Inc., Wetzlar, Germany). Calcein AM was excited at 488 nm and images were collected at 501–530 nm emission, and ethidium homodimer was excited at 543 nm and images were collected at 595–643 nm emission.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by either one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey procedure for post hoc comparison using Graph Pad Prism. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and significance levels were indicated in the figures as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001.

3.0 Results

3.1 Silk as a biocohesive sacrificial binder in ceramics fabrication

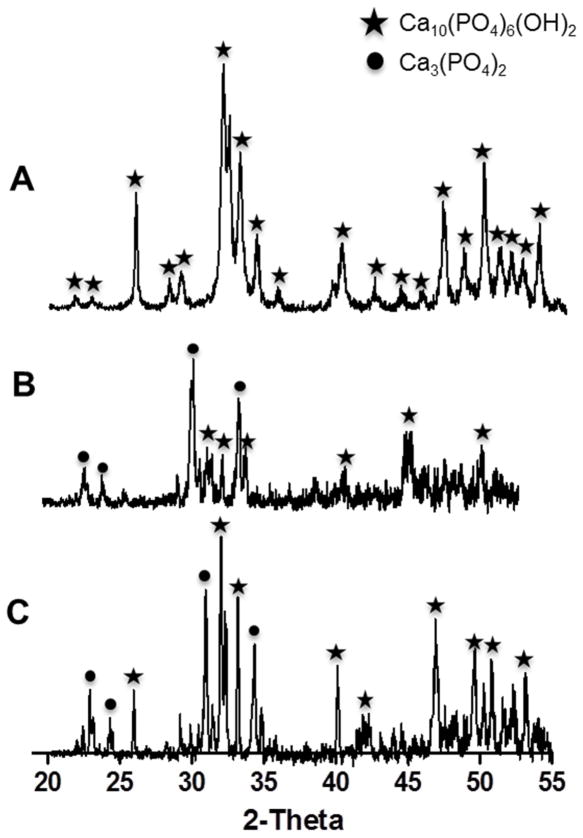

Three techniques were developed to leverage the unique properties of natural silk protein in hydroxyapatite scaffold fabrication. Each technique involved combining reconstituted silk protein with hydroxyapatite (HA) to form HA-silk composite green bodies (Figure 1A). HA was mixed with silk in either concentrated aqueous form in the Silk Solvent (SS) and Silk Freeze Drying (SFD) methods or as a water soluble powder in the Silk Powder (SP) method to generate different mass ratios of HA to silk (Figure 1A). HA dispersed easily in the silk solution to form a homogenous HA-silk paste, which could be hand molded into silicone molds of any diverse shape or configuration (i.e. stars, threaded bolts, human teeth) (Figure 1B–D). The adhesive nature of the silk protein induced ceramic grain consolidation in the green body, which was stabilized by exposing it to mild heat (SS and SP) or freeze-drying (SFD) prior to sintering. The consolidated, stable nature of the green bodies allowed casting HA scaffolds into both large and intricate structures that maintained their shape prior to sintering (Figure 1B–D). The green bodies were sintered at either 1300°C or 1400°C to fuse HA particles and generate high strength scaffolds. As no significant differences in scaffold properties (morphological, mechanical, cell interactions) were observed between the two sintering temperatures, we only present data on 1300°C for clarity. Scaffolds prepared from green bodies of up to 20% silk by mass fabricated by any of the three silk-based methods were machinable using carbide-tipped cutting tools. Despite the significant mass loss during sintering and chalk-like consistency of SFD scaffolds, they could still be cut without fracturing to create parts with a smooth finish (Figure 1F). A significant decrease in scaffold volume and mass was observed following sintering (Figure 1E and Figure 2) in all fabrication methods. While the decrease in scaffold volume was not affected by the HA-silk ratio (~70% decrease), the scaffold mass loss increased with higher silk content in the green body (Figure 2), suggesting that silk was lost during the sintering process and acted as a sacrificial porogen, resulting in higher porosity in scaffolds with higher silk content. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) of both the surface and center of the sintered scaffolds confirmed the complete removal of silk protein from the HA-silk green body following sintering as evidenced by the absence of major characteristic silk peaks (peaks (100) at 19.5°, (101) at 22.6°, and (102) at 27.1°) [32] (Figure 3B–C). The diffraction analysis also revealed a phase transition from hydroxyapatite into alpha-tricalcium phosphate indicated by the loss of several major characteristic HA peaks (peaks (002) at 25.9°, (211) at 31.8°, (300) at 32.9°, (310) at 39.8°, and (213) at 49.5°) (JCPDS 0 9–0432) seen in the initial hydroxyapatite powder (Figure 3A) and the appearance of characteristic alpha-TCP peaks (peaks (162) at 22.8°, (132) at 22.9°, (261) at 24.1°, and (034) at 30.7°) (JCPDS 29–0359) observed only in the sintered material (Figure 3B–C). Based on these observations, the final sintered scaffolds were biphasic, containing a mixture of both HA and alpha-TCP. No effect of fabrication method or HA/silk ratio on phase change was observed.

Figure 1.

Silk-based processing methods for fabrication of HA scaffolds. A. Silk protein is used in the form of a concentrated aqueous solution in the Silk Solvent (SS) and Silk Freeze Drying (SFD) Methods or as a soluble silk powder, made by freeze-drying silk solution followed by blending, in the Silk Powder (SP) Method to bind ceramic particles together into complex geometry green bodies (B–D). The silk later acts as a sacrificial polymer during sintering to induce porosity in the final scaffolds (E), which can then be machined into any three-dimensional shape using standard machining techniques (F). Scale bars are 10 mm in B and E, and 5 mm in C, D, and F.

Figure 2.

Shrinkage of silk-fabricated HA scaffolds during sintering. Shrinking of HA-silk green bodies during sintering at 1300°C was associated with a loss of both volume and mass as shown for green bodies with varying silk content (1% to 20% by mass) for A) Silk Powder Method, B) Silk Solvent Method, and C) Silk Freeze Drying (***p<0.001 and n.s. p>0.05, n = 10). Differences in mass loss with consistent decreases in volume for the three HA/silk ratios were observed, suggesting differences in final scaffold porosity.

Figure 3.

Phase analysis of HA material and sintered silk-fabricated HA scaffolds. a) X-ray diffraction patterns of HA powder used for scaffold fabrication confirmed the presence of a single phase of HA and no trace of secondary phases or contaminating residues. b) XRD patterns of the sintered scaffold surface and c) sintered scaffold center confirmed the complete removal of silk protein during sintering based on the absence of characteristic silk peaks, and also revealed biphasic composition of the post-sintered material containing a mixture of both HA and alpha-tricalcium phosphate. Phase compositions were similar for scaffolds sintered at either 1300°C or 1400°C. A star denotes a peak corresponding to HA, and a circle denotes a peak corresponding to alpha-TCP.

3.2 The effect of HA-silk processing on scaffold morphology, porosity, and density

Processing of HA with silk involved several controllable parameters that affected the final properties of the sintered scaffolds. Scaffold morphology, porosity, and pore size were influenced by both the HA-silk fabrication method (SP, SS, SFD) and silk content in the green body (1–20% by mass). The highest overall porosity, regardless of silk content, was observed in the SFD method, where the green body was stabilized by freeze-drying rather than mild heating (SS and SP methods) (Figure 4A–B). For each HA/silk ratio (99/1, 90/10, 80/20), HA scaffolds fabricated by the SFD method displayed significantly higher overall porosity (p<0.0001) compared to the matching scaffold fabricated by the SP or SS method. Scaffolds fabricated by the SS method displayed higher porosity (p<0.0001) compared to those fabricated by the SP method at 90/10 and 80/20 HA/silk ratios, but not at 99/1. A significant increase in porosity was observed with increased silk content for all fabrication methods (p<0.0001 in SS and SFD and p<0.01 in SP), except in SP, where an increase in silk content from 90/10 to 80/20 did not result in a significant increase in scaffold porosity (Figure 4C). Interestingly, even at lowest silk content (99/1), scaffolds fabricated by the SFD method displayed significantly higher porosity compared to higher silk content scaffolds fabricated by the other two methods (p<0.0001 compared to SS90/10, SP90/10 and SP80/20). Scaffold porosity ranged between 2.7 ± 1.4% for SS99/1 and 50 ± 2.6% for SFD80/20. Porosity results in Figure 4C are from liquid displacement measurements, however, both SEM and micro-CT analysis confirmed these trends (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Silk-fabricated HA scaffold morphology and porosity. a) Micro-computed tomography imaging at 25X magnification of both the surface and cross-section of silk-fabricated HA scaffolds made by SP, SS, and SFD methods with varying silk content (1% to 20% by mass) and sintered at 1300°C. Scale bars are 0.75 mm. b) Scanning electron microscopy images taken at 200X magnification of the fracture inner surface of HA scaffolds sintered at 1300°C made wit h 1% to 20% silk by mass using SP, SS, and SFD methods. c) Liquid displacement was used to measure the total porosity of HA scaffolds made from green bodies with HA/silk ratios of 99/1, 90/10, and 80/20 and sintered at 1300°C (error bars = s.d., n = 6). d) Mean macropore diameter was measured from SEM micrographs using ImageJ (error bars = s.d., n = 30). Macropores were not always circular in shape, so pore diameter was measured in the plane normal to the long axis of elongated pores. Scale bars are 100 μm in all SEM images.

SFD80/20 scaffolds displayed mean pore size of 107.7 ± 13.5 μm, significantly larger than all other conditions. The trends observed in scaffold porosity did not translate to pore diameter, with pore sizes for most scaffolds (other than SFD80/20) ranging between 39.1 ± 15.1 μm (SP99/1) and 65.9 ± 13.5 μm (SS80/20) (Figure 4D). SEM images of the fractured samples and cross-sectional micro-CT scans revealed qualitative differences in HA scaffold morphology based on fabrication method and HA/silk ratio. SFD scaffolds were characterized by large interconnected macropores, homogenous pore distribution, and a high degree of microporosity with distinct grain boundaries (Figure 4A–B). Scaffolds made by the SS and SP methods displayed smaller pores and more grain fusion resulting in lower microporosity. Micro-CT images for SS and SP fabricated scaffolds still showed homogenous pore distribution, but much lower pore interconnectivity, especially for SP scaffolds (Figure 4A).

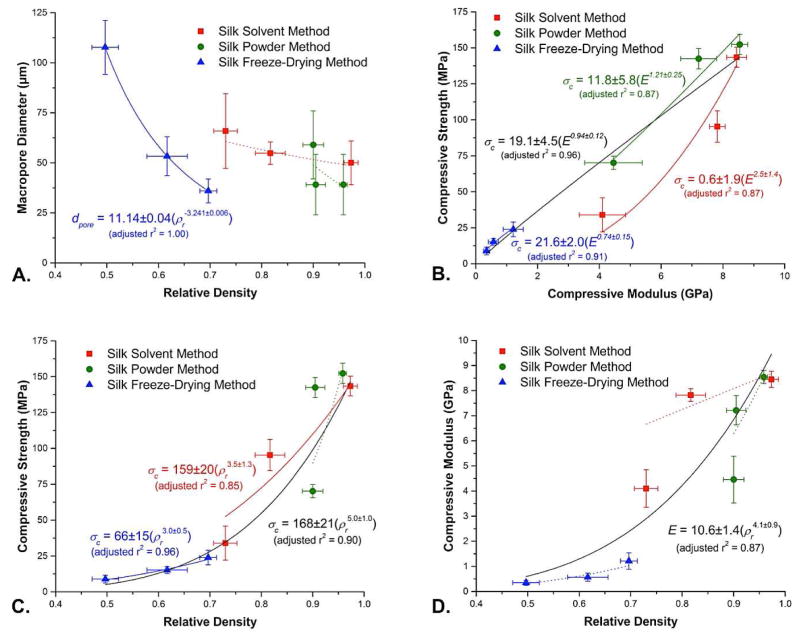

Relative density of the sintered scaffolds, defined as the density of the porous body divided by skeletal density and calculated in practice as [1 − (porosity/100)], also varied according to silk fabrication method. SFD scaffolds exhibited the lowest relative densities (0.697, 0.617, and 0.497 for SFD99/1, 90/10, and 80/20, respectively) compared to samples prepared via the SS (0.973, 0.817, and 0.73) and SP methods (0.958, 0.905, and 0.9) (Figure 6A). In the SFD scaffolds, macropore diameter increased as relative density decreased, with the trend fit very closely by a power law dependence (adjusted r2 = 1.00). This observation is consistent with a situation where ice crystallization is responsible for defining the macropore structure, with the HA/silk ratio providing a means of controlling this process. In contrast, the lack of any significant variations in macropore size as a function of relative density for scaffolds prepared via the SS and SP methods implies that the macropore size of materials produced via these methods is independent of porosity and HA/silk ratio. (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Mechanical and structural properties correlation plots. a) Macropore diameter (μm, n = 3) vs. relative density (error bars = s.d., n = 5). b) Compressive strength vs. compressive modulus (error bars = s.d., n = 5). c) Compressive modulus vs. relative density (error bars = s.d., n = 5). d) Compressive strength vs. relative density (error bars = s.d., n = 5). All lines shown represent error-weighted two-parameter power law fits determined using OriginLab Origin 8.5; solid curves indicate fits with adjusted r2 ≥ 0.85, while dotted curves indicate fits with lower levels of correlation. Variables used include dpore (macropore diameter), ρr (relative density), σc (compressive strength) and E (compressive modulus).

3.3 Silk consolidation casting of high strength HA scaffolds

The mechanical properties of sintered HA scaffolds under compression were assessed to determine the effects of HA/silk ratio and silk fabrication method on scaffold strength and stiffness. Overall, SP fabricated scaffolds displayed the highest and SFD fabricated scaffolds the lowest compressive strengths, regardless of the HA/silk ratio (Figure 5A). SP fabricated scaffolds were significantly stronger than their HA/silk ratio matched SS and SFD counterparts (p<0.0001), except SP99/1 and SS99/1, which displayed similar compressive strengths. SS fabricated scaffolds also displayed significantly higher compressive strength compared to their SFD counterparts (p<0.0001) (Figure 5A). The highest and lowest compressive strength were observed for SP99/1 and SFD80/20 scaffolds, with 152.4 ± 9.1 MPa and 8.7 ± 2.7 MPa respectively. Compressive strength of HA scaffolds decreased with increased silk content, with significant differences (p<0.0001) observed between all HA/silk ratios in SP and SS conditions, except SP99/1 and SP90/10. In SFD fabricated scaffolds, 99/1 scaffolds were significantly stronger (p<0.05) compared to 80/20, but not 90/10 scaffolds (Figure 5A). As expected for cellular solids, a strong power law dependence of compressive strength on relative density was observed for scaffolds produced via two of the three silk fabrication methods (SS, adjusted r2 = 0.85, and SFD, adjust r2 = 0.96), as well as for the overall dataset (adjusted r2 = 0.90) (Figure 6C). A smaller power law exponent for the SFD method indicates less severe decreases in compressive strength as relative density decreases, implying better skeletal connectivity in the SFD scaffolds. The SFD power law pre-factor, representing the extrapolated compressive strength of the 100% dense HA material, was approximately 2.5-fold lower in the SFD scaffolds than in the SP and SS scaffolds, however, implying that the SFD scaffolds consist of an inherently weaker material, perhaps due to a lessor degree of consolidation. Finally, the overall power law fit of all of the data indicates an average compressive strength of 168 MPa for the fully dense material (Figure 6C), appreciably less than the compressive strength measured for sintered hydroxyapatite (509 MPa) [33] confirming that the silk-fabricated HA scaffolds do not consist of fully dense skeletal material.

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties of silk-fabricated HA scaffolds. a) Compressive strength (MPa) and b) compressive modulus (GPa) of sintered (1300°C) scaf folds made with varying silk content (1% to 20% by mass) by SP, SS, and SFD methods (error bars = s.d., n = 6). Sintered scaffolds were machined to a final height of 20 mm ± 0.1 mm and a diameter of 10 mm ± 0.1 mm for mechanical testing. C. Comparison of silk-fabricated HA scaffold compressive strength and porosity to that of human bone. Average compressive strength (MPa) and porosity (%) values for each of the three silk-based ceramic fabrication methods (SS, SFD, SP) were compared to literature values for human cortical bone (170–200 MPa, 5–40% porosity) [8, 54] and trabecular bone (2–10 MPa, 25–80% porosity) [11, 12]. Silk-fabricated HA scaffolds can span virtually the entire range of porosity values for cortical and trabecular bone, and exhibit mechanical properties that also span the full compressive strength range of native bone. Thus, silk-based ceramic fabrication can provide the ideal porosity and mechanical profile for a wide variety of bone replacement needs.

Compressive modulus followed similar trends, with very high compressive moduli (GPa) observed in all scaffold fabrication methods, and in particular in SP and SS (Figure 5B). No significant differences in scaffold modulus were observed between SP and SS methods at matched HA/silk ratios, but both techniques resulted in significantly stiffer scaffolds compared to the SFD method (p<0.0001). The highest and lowest compressive moduli were observed for SP99/1 and SFD80/20 scaffolds, with 8.6 ± 0.3 GPa and 0.3 ± 0.1 GPa respectively. Like compressive strength, compressive modulus decreased with increased silk content for SP and SS fabrication methods, but differences were not significant for the SFD method (Figure 5B). As expected, comparisons of compressive modulus with relative density for the three methods again revealed a power law dependence for the overall data set. Consistent with previous discussions of compressive strength vs. relative density, here too a smaller power law exponent was observed for the SFD scaffolds, as well as an extrapolated modulus approximately 2.5-fold lower than that of SP and SS methods (Figure 6D). This further supports the supposition that the SFD scaffolds consist of a material that has experienced less complete consolidation compared to the SS and SP scaffolds. Even in the latter scaffolds, however, the implied compressive moduli for 100% dense samples remain low as compared to sintered hydroxyapatite (81 GPa) [33], again consistent with the idea that none of these samples consists of fully consolidated skeletal material. Nevertheless, as in the case of strength, the modulus of these materials is sufficient for the application of interest.

Finally, as implied by these discussions, a plot of compressive strength versus compressive modulus exhibits linear relationships between stiffness and strength for the SP (adjusted r2 = 0.87) and SFD (adjusted r2 = 0.91) methods, as well as the overall fit of the data (adjusted r2 = 0.96) (Figure 6B). Scaffolds made by the SS method follow a more pronounced power law curve (adjusted r2 = 0.87), on the other hand, implying a more pronounced loss in strength as the modulus drops.

While more study is needed to fully understand the cause of some of the observed variations, these results as a whole nevertheless allow us to distinguish between the three major processing approaches from the standpoint of both macroporous structure and mechanical performance. In particular, the SFD method provides more flexibility as far as macropore structure is concerned, while the SS and SP methods provide consistent macropore sizes regardless of relative density. The SS and SP methods produce scaffolds consisting of more robust material, while the SFD method is the most effective at producing low density scaffolds. Overall, all three approaches have promise, depending on the nature of the need.

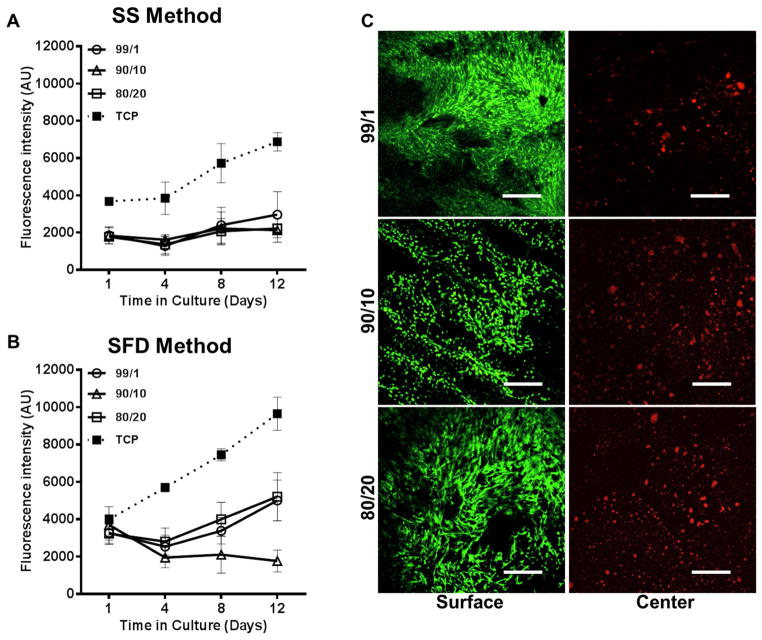

3.4 Response of human mesenchymal stem cells to silk-fabricated HA scaffolds

hMSCs were used to investigate cell interactions with silk-fabricated HA scaffolds. Cell interactions with SS fabricated scaffolds were investigated first using Alamar blue proliferation assay and live/dead cell staining. The cells adhered to the scaffolds without the need for peptide surface modification, and Alamar blue results confirmed cell survival and a degree of proliferation over a 12 day period, with a 1.6-, 1.2- and 1.3-fold increase in cell metabolic rate (i.e. cell number) for SS99/1, 90/10 and 80/20 scaffolds, respectively (Figure 7A). Live/dead cell imaging and confocal microscopy at day 12 showed a continuous, confluent layer of live cells on the scaffold surface, but no cells were observed in the scaffold center (data not shown). As this lack of cell infiltration was likely the result of small pore size and inadequate pore interconnectivity observed in SS method fabricated scaffolds, cells were seeded on SFD fabricated scaffolds, where significantly higher porosity and large pore size were observed. Alamar blue analysis of cells seeded on SFD99/1, 90/10 and 80/20 scaffolds showed 1.6-, 1.8- and 1.7-fold higher fluorescence intensities at day 1 post-seeding compared to SS seeded scaffolds (when corrected for differences in TCP intensity), indicating improve cell seeding on SFD fabricated scaffolds (Figure 7B). While the overall cell numbers on SFD fabricated scaffolds were higher compared to SS scaffolds, cell proliferation rate on 99/1 and 80/20 scaffolds was similar to that on SS scaffolds, with a 1.5- and 1.6-fold increase at day 12 compared to day 1 (Figure 7B). SFD90/10 scaffolds showed a slight downward trend in cell proliferation, which could not be explained in the current study and is not likely due to scaffold properties. Live/dead staining and confocal imaging of SFD scaffolds at 14 days post-seeding again revealed excellent cell attachment and monolayer formation on the scaffold surface. Some cells were found in the scaffold center although they were not viable, likely due to poor mass transport within the bulk of the material (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Human mesenchymal stem cell interaction on silk-fabricated HA scaffolds. Bone marrow-derived hMSCs cultured on sintered HA scaffolds (1300°C) ma de by a) SS method and b) SFD method were measured over 12 days for metabolic activity using Alamar Blue assay. No significant differences were observed between SS scaffolds made from HA/silk green bodies fabricated with 1%, 10%, and 20% silk by mass (p>0.05), but all scaffolds displayed slight increases in proliferation between days 1 and 12 (error bars = s.d., n = 5). SFD scaffolds demonstrated greater retention of seeded cells on day 1 compared to SS scaffolds (error bars = s.d., n = 5) but similar proliferation over 12 days. c) Confocal microscopy imaging of both the surface and center of HA scaffolds stained with calcein AM (live stain) and ethidium homodimer (dead stain) at 12 day post-seeding revealed excellent cell interaction and monolayer formation on the scaffold surface. Cells within the SFD scaffold interior did not survive.

3.5 Incorporation of silk macroporogens in HA scaffold formation

Despite the high porosity and large pore size in SFD fabricated scaffolds, cells that were able to infiltrate into the scaffold center did not survive. To address this, large insoluble Silk Macroporogens (SMPs) were incorporated into green bodies to introduce larger interconnected pores after sintering. SMPs were made from silk sponges that were ground into large particles, stabilized by methanol annealing, and separated with molecular sieves to create small (< 300 μm) and large (300 μm–800 μm) SMP size fractions (Figure 8A). SMPs could be combined with silk solution prior to mixing with HA powder, as in the SS and SFD methods, or mixed with soluble silk powder prior to the addition of HA powder and water, as in the SP method. SMPs maintained their shape and did not dissolve during HA/silk paste formation. One iteration of a high porosity HA scaffold was fabricated using the SS method by incorporating SMPs into a 60/40 HA/silk green body, which was then sintered at 1300°C. Sintering resulted in a similar volume loss compared to other fabrication methods, but a higher mass loss, reflecting higher silk content lost in this fabrication technique (Supplementary Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy images of the fractured scaffolds revealed large connected macropores in scaffolds consisting of small or large SMPs, but not in those prepared without SMPs (Figure 8B). Average macropore diameter in scaffolds prepared with large SMPs was 309 ± 21.2 μm, which was significantly higher than scaffolds made without SMPs (83.7 ± 18.9μm, p<0.05) (Figure 8C). Total porosity also increased from 54.4 ± 3.7% and 54.9 ± 3.5% for no SMP scaffolds and small SMP scaffolds, respectively to 62.9 ± 2.7% for large SMP scaffolds (Figure 8D). Micro-CT imaging confirmed enhanced pore connectivity in scaffolds made with SMPs (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

Silk macroporogens (SMPs) for increased scaffold porosity and macropore size. a) Production of SMPs involved freeze-drying of aqueous silk solution, blending or grinding of the lyophilized silk foam, and stabilization of large silk particles by methanol annealing. b) SEM images show that combining either large (300–800 μm) or small (<300 μm) SMPs with the SS method during green body formation resulted in large interconnected pores in +SMP scaffolds compared to −SMP scaffolds. c) Mean macropore diameter was measured from SEM micrographs using ImageJ. Macropores in +SMP scaffolds made with large SMPs were significantly larger than pores in −SMP scaffolds (error bars = s.d., *p<0.05, n = 30). d) Total porosity as measured by liquid displacement was significantly higher for +SMP scaffolds made with large SMPs compared to +SMP scaffolds made with small SMPs and −SMP scaffolds (error bars = s.d., ***p<0.001, n = 6). e) Micro-computed tomography imaging at 25X magnification of both the surface and cross-section of −SMP and +SMP scaffolds, made with either small or large SMPs, confirms pore interconnectivity. Scale bars are 200 μm for all SEM images and 0.75 mm for micro-CT images.

hMSCs were seeded on SMP fabricated scaffolds to characterize cell interactions with these new constructs (Figure 9A). Cells were seeded in the presence of a fibrin gel to help retain cells within the scaffold during the seeding process. No fibrinolytic inhibitor was added to the media to prevent the fibrin gel from degrading over the culture period. No difference in cell attachment at day 1 was observed between the three different HA scaffolds. Cell proliferation rate was improved on these scaffolds, compared to previous fabrication methods, with a 2.3-, 2.5- and 2.7- fold increase in cell numbers at day 12 compared to day 1 on no SMP, small and large SMP fabricated scaffolds respectively. A 2.1- and 2.5- fold increase was observed on TCP and cell seeded fibrin gel. Significantly more cells were observed on small and large SMP fabricated scaffolds at day 12 post-seeding compared to no SMP scaffolds (p<0.0001) (Figure 9A). Live/dead staining and confocal microscopy of the surface and center of SMP fabricated scaffolds revealed excellent cell proliferation on the scaffold surface as well as improved cell infiltration and survival within the scaffold center (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

Human mesenchymal stem cell response to +SMP scaffolds. a) Bone marrow-derived hMSCs seeded in fibrin gel on +SMP and −SMP scaffolds (1300°C) were measured over 12 days for metabolic activity using Alamar Blue assay. Significantly more cells were observed on small and large SMP fabricated scaffolds at day 12 post-seeding compared to no SMP scaffolds (error bars = s.d., ***p<0.0001, n = 5). b) Confocal microscopy on both the surface and center of +SMP and −SMP scaffolds stained with calcein AM (live stain) and ethidium homodimer (dead stain) revealed excellent cell proliferation on the scaffold surface as well as improved cell infiltration and survival within the scaffold center.

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Biocohesive consolidation of hydroxyapatite by silk

The fundamental weakness associated with high porosity biomaterials has hindered advancement in bone regeneration and left the demand for a porous yet mechanically competent bone replacement graft wholly unmet. We demonstrated the use of silk protein as a tool in ceramic fabrication, specifically as a biocohesive agent and sacrificial polymer, to generate high strength, porous HA ceramics. Unlike HA scaffolds fabricated using polymers such as collagen, alginate, agarose, starch, polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), or polycaprolactone (PCL), silk-fabricated scaffolds exhibited mechanical and morphological properties well suited for repair of bones that experience a wide range of mechanical stress, including load-bearing cortical bone. The majority of HA scaffolds previously fabricated using other polymers, via methods such as porogen burn-out, foam casting, slip casting, direct foaming, exhibited low compressive strengths on the order of 5 to 40 MPa, thereby limiting them to non-load bearing application [7, 10, 34–39]

The unique ability of silk protein to bind and consolidate ceramic grains leads to the formation of high density, high strength scaffolds of any shape or size. In particular, the thermal stability of the silk protein, evidenced by its high degradation temperature (230°C) and ability to withstand several autoclave cycles [28], as well as the protein’s tendency to form insoluble beta-sheet conformations [29], permits the formation of dense, stable HA-silk green bodies. The adhesive nature of the silk further maintains the three-dimensional shape of the green bodies after molding [27]. Previous studies on polymer-based ceramic fabrication using other natural and synthetic polymers lack the flexibility to produce complex shape scaffolds, and are limited to simple geometric shapes (i.e. cylinders, rectangles, triangles) [8, 14, 40–43]. Lastly, the inexpensive, environmentally-friendly aqueous-based processing [31, 44] of silk fibroin from B. mori cocoons makes silk a superior alternative for ceramics processing over other natural or synthetic polymers that typically involve the use of harsh chemicals and organic solvents [45, 46].

In these methods silk protein was combined with HA as a concentrated aqueous solution, dry soluble powder, or in the form of large insoluble macroparticles; however alternative forms of silk (i.e. hydrogels, microfibers, and nanospheres) can be substituted. The versatility of silk-based ceramic fabrication lies in the large number of tunable processing parameters, including silk method (SP, SS, SFD), green body silk content (% by mass), and green body stabilization (mild heat vs. freeze drying). Silk processing factors, such as protein molecular weight and silk fibroin concentration, provide added flexibility to these protocols. In the SS and SFD methods, a high molecular weight (20-minute boil) silk was used due its superior stabilization of the green body after exposure to mild heat or lyophilization. For the SP method, a low MW (60-minute boil) silk was chosen for the soluble silk powder, which greatly enhanced solubility (data not shown). We discuss later how differences in silk MW may have contributed to observed differences in sintered scaffold properties. Once green bodies were cast into the desired size and shape they were stabilized by inducing a conformational change in the silk protein from amorphous random coil to crystalline beta-sheet. Silk consolidation of ceramic grains is dictated by a physical, non-specific binding mechanism that is facilitated by drying of the silk protein, which allows application of this technique to other calcium phosphates (i.e. TCP, MCPA, DCPA, OCP) or reactive calcium phosphate cements.

4.2 Silk method and green body composition influence morphology, porosity, density, and cell interaction

Scaffold porosity and pore size play a critical role in osteogenesis in vivo and in vitro. For ceramic materials, both macroporosity (>50 μm) and microporosity (<10 μm) are required for good osteogenic outcomes, with the former being important for cell infiltration and mass transport and the latter contributing to surface area and surface roughness [47]. Previous studies have shown that the minimum porosity and pore size needed for vascularization and new bone formation fall in the range of 40–60% with at least 100 μm pores [48, 49]. Ice crystal sublimation in SFD green bodies during lyophilization, in addition to the silk porogens that burned off during sintering, gave SFD scaffolds the highest total porosity and largest mean pore size of the three silk methods, surpassing optimal literature-defined pore criteria. Both the SS and SP methods exhibited lower porosities and pore sizes than the SFD method, with SP scaffolds displaying the lowest porosity of the three methods. Even with adequately sized macropores, SP method scaffolds lacked sufficient total pore volume, suggesting either low pore connectivity or a low degree of microporosity. Despite the identical stabilization treatment of the SS and SP method green bodies, differences in porosity between these two methods are likely due to the use of two different MW silk proteins rather than differences in the physical state of the silk (aqueous solution vs. soluble powder). The silk protein chains, interspersed throughout the green body, glue the structure together and leave behind voids after sintering. Low MW protein chains, as in the SP method, possibly allow tighter packing of ceramic grains leading to a denser, less porous scaffold after silk removal. However, since silk processing variables were not directly addressed in this work, the effect of these factors on scaffold morphology can only be speculated upon until further investigation.

Differences in cell interactions on silk-fabricated HA scaffolds depended on fabrication method rather than green body composition. We observed improved cell seeding on SFD compared to SS scaffolds, which was likely a result of enhanced capillary fluid absorption due to higher porosity. Although cell proliferation rates were similar on SFD and SS scaffolds over 12 days, cells were unable to penetrate into SS scaffold center and, instead, proliferated to cover the scaffold surface. Confocal microscopy confirmed the presence of cells in the center of SFD scaffolds, however, it is uncertain whether these cells were simply drawn in by capillary action during seeding, or migrated from the scaffold surface over the 12-day culture period. Regardless of their means of entry, these cells were unable to survive, likely due to insufficient mass transport. To improve cell viability in the scaffold bulk, silk macroporogens were incorporated into green bodies and burned off during sintering resulting in significantly higher porosity and pore size than SS, SP, or SFD alone. Cells that infiltrated into the center of scaffolds prepared with either small or large SMPs remained viable over 12 days. Despite the relatively few cells observed in the SMP scaffold center compared to the number that were seeded, we hypothesize that the natural degradation of the HA scaffold over time, when implanted in vivo, would facilitate further cell integration and, eventually, complete graft resorption. In addition, while only static culture conditions were tested in these studies, we expect that providing dynamic perfusion to these scaffolds would greatly enhance cell viability within the scaffold center.

4.3 Silk-fabricated HA scaffolds are mechanically suited for load bearing cortical and trabecular bone repair

Only a small fraction of bioactive bone replacement materials currently available on the orthopedic market are suitable for load bearing bone repair. The majority of injectable CaP cements (CPCs) used in bone regeneration do not exceed a maximum compressive strength of 40–50 MPa, falling far short of the mechanical requirements of cortical bone (170–200 MPa under longitudinal compression), and limiting them to non-load bearing application (i.e. cranio-maxillofacial repair, periodontal surgery, and inner ear ossicle repair) [7, 50–54]. In this work, silk-ceramic fabrication was used to generate robust HA scaffolds with exceptionally high strength that maintained excellent cellular interaction in vitro. The highest strength silk-fabricated HA scaffolds (152.4±9.1 MPa) matched more than 75% of the maximal strength of human cortical bone with porosity values comparable to that of cortical bone (5–40%) (Figure 5C). Mechanical properties of silk-fabricated HA scaffolds were unusually high for a porous bioceramic material, and few other solvent-based ceramic fabrication methods have produced HA scaffolds with comparable strength [8]. As expected, mechanical strength decreased substantially as porosity increased with higher silk content (1% to 20% by mass), however SS and SP scaffolds made from 20% silk by mass still maintained strengths greater than that of trabecular bone (2–10 MPa) (Figure 5C). SFD scaffolds were comparatively weaker than both SS and SP due to additional porosity imparted by freeze-drying that gave the SFD scaffolds significantly higher porosity within the range of trabecular bone (25–80%) (Figure 5C). Although the compressive strength of SFD scaffolds was substantially lower than that of cortical bone, both SFD99/1 and SFD90/10 exceeded the compressive strength of trabecular bone with SFD80/20 matching the high end of this range (Figure 5C). Therefore, both SS and SP scaffolds are suited for load-bearing cortical bone repair in regions of lower porosity, whereas SFD scaffolds may be useful for non-load bearing trabecular bone repair, particularly in regions where a high porosity scaffold is desired.

4.4 Limitations of the technique

The use of silk for biocohesion and pore formation in ceramics fabrication offers controllable processing to generate a range of scaffold morphologies and mechanical properties. However, limitations of these silk-based methods restrict the range of scaffolds that can be produced. While the adhesive nature of silk makes it an excellent ceramic consolidation agent in green body formation, the inherent stickiness of the silk protein hinders the production of green bodies that contain greater than 60% silk by mass. Above this threshold, the HA-silk paste becomes difficult to handle and cast into molds. Post-sinter machining of HA scaffolds is also limited by these techniques. Although HA scaffolds prepared from up to 20% silk by mass using any of the three silk methods (SS, SP or SFD) were machinable, we anticipate a cap on the silk content used to fabricate porous HA scaffolds that can still be machined without breaking. As with any bone scaffold material, there is an upper functional limit to pore size and porosity that renders the graft inappropriate for use in load bearing applications.

4.5 Potential application in bone repair

Silk-based ceramics processing methods are useful in fabricating HA scaffolds with a wide range of properties, from high strength for load bearing bone repair, to high porosity when rapid cell integration is needed in non-load bearing regions. Each of the three silk methods presented in this work applied the same underlying principle of silk-aided ceramic consolidation followed by subsequent silk burn-off. The large number of tunable parameters in these protocols provided fine control over sintered scaffold properties (i.e. porosity, pore size, mechanics), and the adhesive nature of the silk protein allowed the scaffolds to be molded into any three-dimensional shape. A comparison of compressive strength with porosity for each fabrication method revealed the broad range of achievable properties for silk-fabricated HA scaffolds. Across the porosity spectrum, SS and SP scaffolds made from 1–20% silk by mass fell within the literature-defined range of porosity values for cortical bone (5–40%) [8, 54], and SFD scaffolds displayed higher porosities comparable to that of trabecular bone [11, 55]. Across the range of mechanical strength, silk-fabricated scaffolds matched or exceeded the strength of trabecular bone, with some silk-fabricated scaffolds made by SS and SP falling only 10% short of the low-end range compression strength for cortical bone (170–200 MPa) (Figure 5C). Thus, silk-fabricated HA scaffolds can span virtually the entire range of porosity values for cortical and trabecular bone, and exhibit mechanical properties that also span the full compressive strength range of native bone.

Due to the exceptionally high compressive strength of these silk-fabricated ceramics, scaffolds prepared by any of the three silk methods with up to 20% silk by mass could be cut using standard machining techniques. This machinability sets silk-fabricated HA ceramics apart from weaker scaffolds made by other polymer-based ceramics fabrication methods that cannot withstand even the lowest cutting forces [34]. Moreover, the unusual stability of the silk protein when subjected to elevated temperature and pressure or high shear force [28] gives the silk protein a rare potential to be used in protein-ceramic injection molding, compression molding, or dry powder pressing to manufacture high strength, selectively porous ceramic orthopedic implants (i.e. bone plates, screws, pins). Thus, given the reproducibility of these techniques, tunable processing parameters, optional manufacturing techniques, exceptionally high scaffold strength, controllable porosity, and machinability for post-processing, silk-based ceramics fabrication offers limitless potential in patient-specific grafting for the regeneration of a defect of any geometry in any bone.

5.0 Conclusion

We report the fabrication of hydroxyapatite scaffolds using natural silk protein for ceramic grain consolidation in green body formation and later for inducing porosity during sintering. Silk is an optimal alternative to synthetic polymeric binders and porogens due to its natural adhesive properties, high stability, and ease of production using environmentally friendly aqueous-based processing. By leveraging the unique properties of silk, stable, complex geometry scaffolds with controlled porosity and mechanical profiles can be formed for any bone replacement application. Moreover, we demonstrate the machinability of these silk-fabricated bioceramics, which offers the potential for patient specific bone grafting. By combining HA and silk in various formats we can generate scaffolds with exceptionally high strength comparable to that of load bearing cortical bone, as well as scaffolds with high porosity that support and encourage cell ingrowth within the scaffold. The power of these silk fabrication methods lies in the many tunable parameters that can be modified during processing to achieve a desired set of scaffold properties tailored to clinical need. Silk-based bioceramics fabrication holds exciting promise for the future of load bearing bone replacement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH (DE017207, EB002520 and 2R01DE016525-06A1) for support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Epidemiology: major orthopedic surgery - on the rise as the global elderly population continues to grow. Datamonitor Reports. 2011:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gugala Z, Lindsey RW, Gogolewski S. New approaches in the treatment of critical-size segmental defects in long bones. Macromol Symp. 2007;253:147–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurencin CT, Ambrosio AMA, Borden MD, Cooper JA. Tissue Engineering: orthopedic applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:19–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichte P, Pape HC, Pufe T, Kobbe P, Fischer H. Scaffolds for bone healing: concepts, materials, and evidence. Injury. 2011;42:569–73. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruskin E, Doll BA, Futrell FW, Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO. Demineralized bone matrix in bone repair: history and use. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2012;64:1063–77. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorozhkin SV. Calcium orthophosphate-based biocomposites and hybrid biomaterials. J Mater Sci. 2009;44:2343–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellucci D, Sola A, Gazzarri M, Chiellini F, Cannillo V. A new hydroxyapatite-based biocomposite for bone replacement. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013;33:1091–101. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deville S, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. Freeze casting of hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5480–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorozhkin SV. Bioceramics of calcium orthophosphates. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1465–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Lorenzo LM, Vallet-Regi M, Ferreira JMF, Ginebra MP, Aparicio C, Planell JA. Hydroxyapatite ceramic bodies with tailored mechanical properties for different applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2001;60:159–66. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramay HR, Zhang M. Biphasic calcium phosphate nanocomposite porous scaffolds for load-bearing bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson LJ. The mechanical behavior of cancellous bone. Biomechanics. 1985;18:317–28. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choong C, Triffitt JT, Cui ZF. Polycaprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Food Bioprod Process. 2004;82:117–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valente JFA, Valente TAM, Alves P, Ferreira P, Silva A, Correia IJ. Alginate based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2012;32:2596–603. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahl D, Czernuszka J. Collagen-hydroxyapatite composites for hard tissue repair. Eur Cells Mater. 2006;28:43–56. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v011a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Dogan F, Bal BS. Freeze casting of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds. I. Processing and general microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 2008;86B:125–35. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potoczek M. Hydroxyapatite foams produced by gel casting using agarose. Mater Lett. 2008;62:1055–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyckfeldt O, Ferreirab JMF. Processing of porous ceramics by ‘starch consolidation’. J Eur Ceram Soc. 1998;18:131–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregorová E, Pabst W. Process control and optimized preparation of porous alumina ceramics by starch consolidation casting. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2011;31:2073–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorová E, Pabst W, Bohacenko I. Characterization of different starch types for their application in ceramic processing. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2006;26:1301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevalier E, Chulia D, Pouget C, Viana MN. Fabrication of porous substrates: A review of processes using pore forming agents in the biomaterial field. J Pharm Sci. 2007;97:1135–54. doi: 10.1002/jps.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yunos DM, Bretcanu O, Boccaccini AR. Polymer-bioceramic composites for tissue engineering scaffolds. J Mater Sci. 2008;43:4433–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Oliveira JF, De Aguiar PF, Rossi AM, Soares GA. Effect of process parameters on the characteristics of porous calcium phosphate ceramics for bone tissue scaffolds. Artif Organs. 2003;27:406–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2003.07247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Champion E. Sintering of calcium phosphate bioceramics. Acta biomater. 2013;9:5855–75. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. The mechanics of three-dimensional cellular materials. Proc R Soc B. 1982;382:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. Cellular solids: structure and properties. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahni V, Blackledge T, Dhinojwala A. A review on spider silk adhesion. J Adhesion. 2011;87:595–614. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunniff P, Fossey S, Auerbach M, Song J, Kaplan D, Adams W, et al. Mechanical and thermal properties of dragline silk from the spider nephila clavipes. Polym Advan Technol. 2003;5:401–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu X, Shmelev K, Sun L, Gil E, Park S, Cebe P, et al. Regulation of silk material structure by temperature-controlled water vapor annealing. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:1686–96. doi: 10.1021/bm200062a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto A, Chen J, Collette AL, Kim U, Altman GH, Cebe P, et al. Mechanisms of silk fibroin sol-gel transitions. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:21630–8. doi: 10.1021/jp056350v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockwood DN, Preda RC, Yucel T, Wang X, Lovett ML, Kaplan DL. Materials fabrication from bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1612–31. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valluzzi R, Gido SP, Zhang W, Muller WS, Kaplan DL. Trigonal crystal structure of bombyx mori silk incorporating a threefold helical chain conformation found at the air-water interface. Macromolecules. 1996;29:8606–14. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akao M, Aoki H, Kato K. Mechanical properties of sintered hydroxyapatite for prosthetic applications. J Mater Sci. 1981;16:809–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian J, Tian J. Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite. J Mater Sci. 2001;36:3061–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almiralla A, Larrecqa G, Delgadoa JA, Martinezb S, Planella JA, Ginebra MP. Fabrication of low temperature macroporous hydroxyapatite scaffolds by foaming and hydrolysis of an α-TCP paste. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3671–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.del Reala RP, Wolkeb JGC, Vallet-Regia M, Jansen JA. A new method to produce macropores in calcium phosphate cements. Biomaterials. 2002;23:3673–80. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramay HR, Zhang M. Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds by combination of the gel-casting and polymer sponge methods. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu DM. Influence of porosity and pore size on the compressive strength of porous hydroxyapatite ceramic. Ceram Int. 1997;23:135–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawata M, Uchida H, Itatani K, Okada I, Koda S. Development of porous ceramics with well-controlled porosities and pore sizes from apatite fibers and their evaluations. J Mater Sci. 2004;15:817–23. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000032823.66093.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SS, Sun Park M, Jeon O, Yong Choi C, Kim BS. Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kucharska M, Butruk B, Walenko K, Brynk T, Ciach T. Fabrication of in-situ foamed chitosan/β-TCP scaffolds for bone tissue engineering application. Mater Lett. 2012;85:124–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin L, Wang Z, Zhou L, Hu Q, Fang M. The influence of prefreezing temperature on pore structure in freeze-dried beta-TCP scaffolds. Proc Inst Mech Eng H J Eng Med. 2013;227:50–7. doi: 10.1177/0954411912458739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezaei A, Mohammadi MR. In vitro study of hydroxyapatite/polycaprolactone (HA/PCL) nanocomposite synthesized by an in situ sol-gel process. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013;33:390–6. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim U, Park J, Kim H, Wad M, Kaplan DL. Three-dimensional aqueous-derived biomaterial scaffolds from silk fibroin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2775–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Astete CE, Sabliov CM. Synthesis and characterization of PLGA nanoparticles. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2012;17:247–89. doi: 10.1163/156856206775997322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian H, Tang Z, Zhuang Z, Chen X, Jing X. Biodegradable synthetic polymers: preparation, functionalization and biomedical application. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:237–80. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan H, Kurashina K, de Bruijn JD, Li Y, de Groot K, Zhang X. A preliminary study on osteoinduction of two kinds of calcium phosphate ceramics. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1799–806. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karageorgious V, Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hulbert SF, Young FA, Mathews RS, Klawitter JJ, Talbert CD, Stelling FH. Potential of ceramic materials as permanently implantable skeletal prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res A. 1970;4:433–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820040309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramay HR, Zhang MQ. Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds by combination of the gel-casting and polymer sponge methods. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landi E, Celotti G, Logroscino G, Tampieri A. Carbonated hydroxyapatite as bone substitute. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2003;23:2931–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fukase Y, Eanes ED, Takagi S, Chow LC, Brown WE. Setting reactions and compressive strengths of calcium phosphate cements. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1852–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690121201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sariibrahimoglu K, Wolke JGC, Leeuwenburgh SCG, Jansen JA. Characterization of alpha/beta-TCP based injectable calcium phosphate cement as a potential bone substitute. In: Ishikawa K, Iwamoto Y, editors. Bioceramics. Key Eng Mater. Trans Tech Publications; 2013. pp. 157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin RB, Burr DB, Sharkey NA. Skeletal tissue mechanics. New York: Spring Science and Business Media; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibson LJ. The mechanical behavior of cancellous bone. J Biomech. 1985;18:317–28. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.