Abstract

Efforts to recreate a prebiotically plausible protocell, in which RNA replication occurs within a fatty acid vesicle, have been stalled by the destabilizing effect of Mg2+ on fatty acid membranes. Here, we report that the presence of citrate protects fatty acid membranes from the disruptive effects of high Mg2+ ion concentrations while allowing RNA copying to proceed, while also protecting single-stranded RNA from Mg2+-catalyzed degradation. This combination of properties has allowed us to demonstrate the chemical copying of RNA templates inside fatty acid vesicles, which in turn allows for an increase in copying efficiency by bathing the vesicles in a continuously refreshed solution of activated nucleotides.

The RNA world hypothesis suggests that the primordial catalysts were ribozymes (1, 2), while biophysical considerations suggest that the primordial replicating compartments were membranous vesicles composed of fatty acids and related amphiphiles (3, 4). However, the conditions required for RNA replication chemistry and fatty acid vesicle integrity have appeared to be fundamentally incompatible (5) (Fig S1). Both ribozyme catalyzed and non-enzymatic RNA copying reactions require high (50–200 mM) concentrations of Mg2+ (or other divalent) ions (6), but Mg2+ at such concentrations destroys vesicles by causing fatty acid precipitation.

We developed a screen for small molecules that protect oleate fatty acid vesicles from disruption by Mg2+. We used two assays to monitor the leakage of either a small charged molecule (calcein) or a larger oligonucleotide, allowing us to distinguish between increased membrane permeability (faster calcein release with oligonucleotide retention) and generalized membrane disruption (rapid release of both calcein and the oligonucleotide) (Fig. S2, S3 and S4). We identified several chelators, including citrate, isocitrate, oxalate, NTA and EDTA, that protect oleate vesicles in the presence of at least 10 mM Mg2+ (Fig. S5 and S6). In the presence of chelated Mg2+, oleate vesicles remained intact but exhibited a modest increase in the permeability of a small polar molecule (Fig. 1 and S7) and an even smaller increase in the leakage of an oligonucleotide. In terms of vesicle stabilization, citrate was one of the most effective chelators of Mg2+.

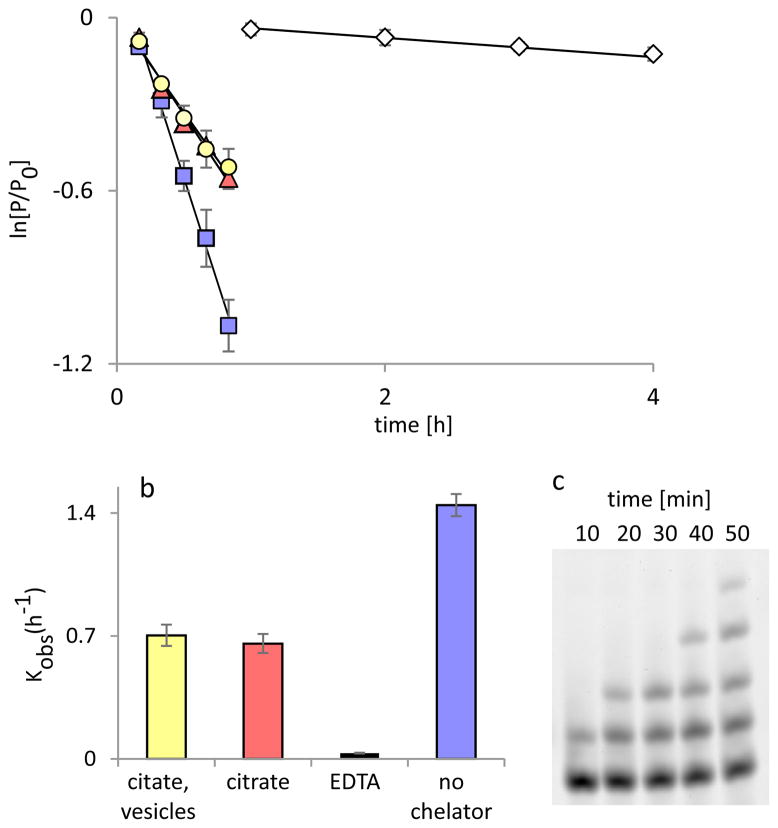

Figure 1. Citrate stabilizes fatty acid vesicles in the presence of Mg2+ ions.

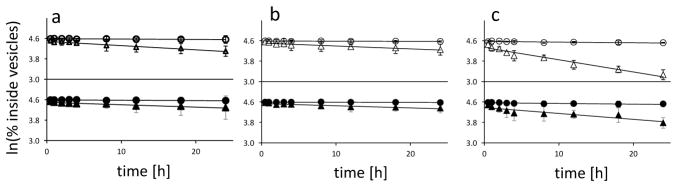

Leakage of a small charged molecule (calcein, open symbols) and a larger 9-mer oligodeoxynucleotide (filled symbols) from fatty acid vesicles. A: oleate vesicles; B: myristoleate: glycerol monomyristoleate 2:1 vesicles; C: decanoate: decanol: glycerol monodecanoate 4:1:1 vesicles. Circles: no MgCl2, no citrate; triangles: 50 mM MgCl2, 200 mM Na+-citrate.

The assay used to obtain this data is described in Figure. Lines are linear fits, R2 ≥ 0.97. All experiments were repeated twice, error bars are mean ±2SE.

We also examined the stability of model protocell membranes made of myristoleic acid: glycerol monomyristoleate 2:1 and from the more prebiotically reasonable decanoic acid: decanol: glycerol monodecanoate 4:1:1. Citrate-chelated Mg2+ caused only a small amount of leakage from these vesicles, and the stabilizing effect of citrate was seen for both calcein and oligonucleotides (Fig. 1 and S8–S13).

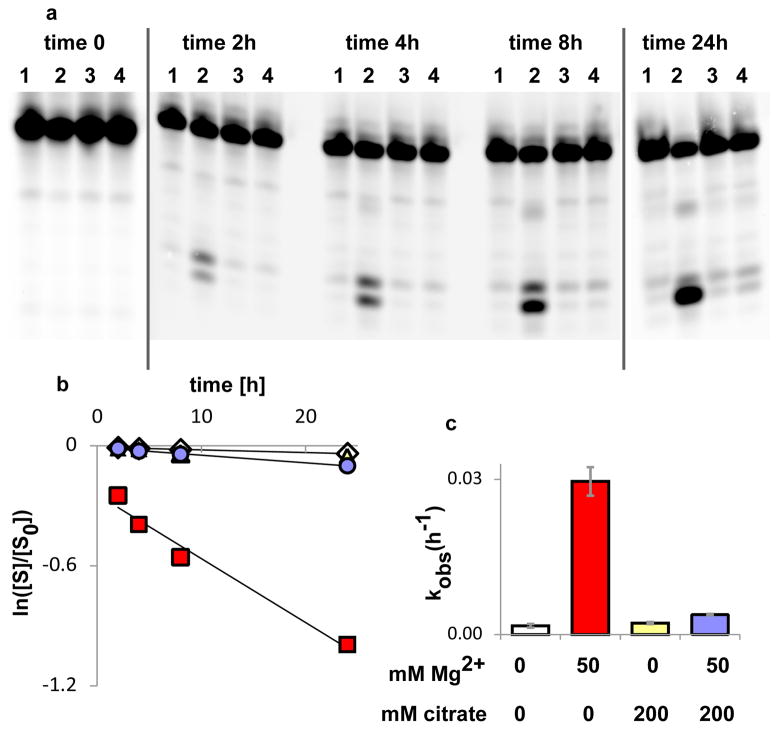

We then asked if these chelators were compatible with the Mg2+ catalysis of non-enzymatic template-directed RNA primer extension. We measured the rate at which an RNA primer was elongated when annealed to an oligonucleotide with a templating region of C nucleotides, in the presence of excess activated G monomer, guanosine 5′-phosphor(2-methyl)imidazolide (2MeImpG) (Fig. 2). We examined citric acid, EDTA, NTA and a weakly stabilizing chelator (isocitric acid). In the presence of 50 mM unchelated Mg2+, the primer-extension reaction proceeded at a rate of 1.4 h1, compared to 0.03 h−1 in the absence of Mg2+ ions. The addition of 4 equivalents of EDTA or NTA resulted in complete abolition of Mg2+ catalysis (Fig. 2 and S14, S15), indicating that the Mg2+ in these samples is chelated in a fashion incompatible with promoting primer extension. In contrast, four equivalents of citrate only decreased the rate of primer extension to 0.67 h−1. For comparison, isocitric acid does not fully protect vesicles (Fig. S16 and S17), but also does not affect the primer extension reaction.

Figure 2. The rate of RNA template-directed primer extension in the presence or absence of Mg2+ chelators and fatty acid vesicles.

A: Time courses of primer extension on a templating region of four C residues, expressed as fraction of un-extended primer remaining vs. time. Squares: no chelators; triangles: 200 mM Na+-citrate; circles: 200 mM Na+-citrate and 100 mM oleate vesicles; diamonds: 200 mM EDTA. Lines are linear fits, R2 ≥ 0.97; the slope is kobs (h−1).

B: Rates of primer extension under the indicated conditions; each kinetic experiment was performed in duplicate and rates are determined as average of the three separate runs. Error bars indicate SEM, n=3.

C: Typical PAGE analysis of a template-directed primer extension experiment. Primer extension was carried out in the presence of 200 mM Na+-citrate.

For the gel analysis of the reactions used to obtain this data, see Supporting Information Figure S15.

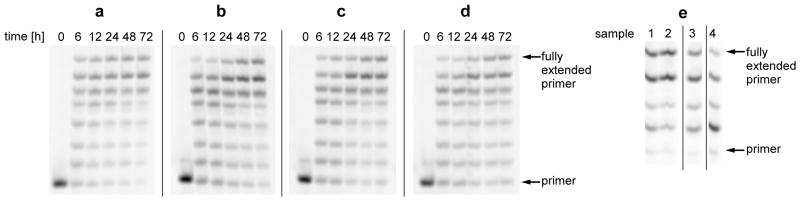

To see if citrate would allow non-enzymatic RNA copying to proceed within fatty acid vesicles, we encapsulated an RNA primer-template complex inside oleate vesicles, added Mg2+ and citrate, and removed unencapsulated RNA by size exclusion chromatography. We then added the activated G monomer 2MeImpG, heated the sample briefly to allow for rapid monomer permeation (7), and then incubated at room temperature for times up to 24 h to allow the monomer to take part in template-copying chemistry inside the vesicles. Analysis of the reaction products showed that after a 24 h incubation most of the primer had been extended by the addition of six G residues, with a smaller fraction extended to full length by the addition of a seventh G residue (Fig. 3). In parallel experiments with vesicles composed of mixtures of shorter-chain lipids, the brief heating step was not necessary, due to the higher permeability of such membranes to nucleotide monomers. It is noteworthy that RNA primer extension occurred efficiently inside vesicles made of decanoic acid: decanol: glycerol monodecanoate 4:1:1 (Fig. 3), since short chain, saturated amphiphilic compounds are more prebiotically plausible than longer chain, unsaturated fatty acids such as oleate or myristoleate. When we encapsulated the RNA primer-template complex inside POPC vesicles, no primer extension was observed, due to the impermeability of phospholipid vesicles to the 2MeImpG monomer (even with a heat pulse) (Fig. S18).

Figure 3. RNA template copying inside model protocell vesicles.

A to D: Primer extension on a templating region of seven C residues. A: control reaction in solution; B: inside oleate vesicles, C: inside myristoleate: glycerol monomyristoleate 2:1 vesicles; D: inside decanoate: decanol: glycerol monodecanoate 4:1:1 vesicles. E: Extension of labeled RNA primer annealed to a mixed base template, templating region sequence GCCG.

Sample 1: reaction inside myristoleate: glycerol monomyristoleate 2:1 vesicles, sample 2: reaction inside decanoate: decanol: glycerol monodecanoate 4:1:1 vesicles, both sample 1 and 2 reactions preformed inside liposome dialyzer (see Supplementary Materials for the description of the liposome dialyzer) with a total of 13 buffer exchanges. Sample 3: control reaction in solution with daily addition of fresh portion of activated monomers, without removing the hydrolyzed monomers. Sample 4: control reaction in solution, without addition of fresh monomer.

The efficiency of non-enzymatic RNA replication can be greatly enhanced by the periodic addition of fresh portions of activated monomer to a primer-extension reaction occurring on templates immobilized by covalent linkage to beads (8). We sought to reproduce this effect by mimicking the flow of an external solution of fresh monomers over vesicles, by periodic dialysis of model protocells against a solution of fresh activated monomers (See Supporting Materials for description of the Liposome Reactor Dialyzer). The control primer-extension reaction in solution shows that the yield of full length primer-extension product from copying a GCCG template is very low, even if fresh monomers are added to the reaction periodically (Figure 3E). In contrast, after repeated exchanges of external solution by dialysis, the proportion of full length product was much greater (Figure 3E).

The high thermal stability of the RNA duplex is a major problem for prebiotic RNA replication (5). Since Mg2+ greatly increases the Tm of RNA duplexes, we asked whether the chelating properties of citrate would prevent the increase in the melting temperature of RNA duplexes caused by the presence of free Mg2+ ions. We observed a small but reproducible decrease in Tm in the presence of citrate when compared to samples containing unchelated Mg2+ (Table S1, Figures S19 and S20). For example, in presence of 50 mM Mg2+ with 4 equivalents of citrate, the Tm of the RNA duplex was 71°C, while in the control sample without citrate the Tm was 75°C.

Citrate also stabilizes RNA by preventing the Mg2+ catalysis of RNA degradation. Incubating a 13-mer oligodeoxynucleotide with one ribo linkage at 75° C, with and without Mg2+ and citrate, results in significant strand cleavage at the site of the single ribo linkage. Four equivalents of citrate, relative to Mg2+, abolished the Mg2+-catalyzed degradation (Fig. 4). The kobs for cleavage at the ribo linkage, at 75 °C in the presence of 50 mM Mg2+ was 0.074 hr−1, while in the presence of a 4-fold excess of citrate, the rate decreased to 0.004 hr−1.

Figure 4. Citrate protects RNA from Mg2+ -catalyzed degradation.

A: PAGE analysis of cleavage of a DNA oligonucleotide at the site of a single internal ribonucleotide, at indicated time points; lanes 1: no Mg2+, no citrate; lanes 2: 50 mM Mg2+, no citrate; lanes 3: no Mg2+, 200 mM citrate; lanes 4: 50 mM Mg2+, 200 mM citrate.

B: Quantitation of strand cleavage, expressed as fraction of intact substrate over total substrate vs. time: diamonds: no Mg2+, no citrate; triangles: no Mg2+, 200 mM citrate; circles: 50 mM Mg2+, 200 mM citrate; squares 50 mM Mg2+, no citrate. Lines are linear fits, R2 ≥ 0.97.

C: Rates of strand cleavage at the ribo linkage with and without Mg2+ and citrate. Error bars indicate SEM, n=3.

The chelation of Mg2+ by citrate exhibits two protective effects in the context of model protocells: protocell membranes based on fatty acids are protected from the disruption caused by the precipitation of fatty acids as Mg2+ salts, and single-stranded RNA oligonucleotides are protected from Mg2+-catalyzed degradation. Based on the known affinity of citrate for Mg2+ (9, 10), it is clear that the RNA synthesis observed in the presence of Mg2+ and citrate cannot be due to residual free Mg2+ (less than 1 mM), and must be due to catalysis by the Mg2+-citrate complex. The crystal structure of Mg2+-citrate (11) shows that the Mg2+ ion is coordinated by the hydroxyl and two carboxylates of citrate, such that three of the six coordination sites of octahedral Mg2+ are occupied by citrate, while the remaining three are free to coordinate with water or other ligands. The clear implication is that coordination of Mg2+ by at most three sites is sufficient for catalysis of template-directed RNA synthesis, but not for catalysis of RNA degradation or for the precipitation of fatty acids. In the absence of a prebiotic citrate synthesis pathway (but see ref. 12 for a recent advance), it is of interest to consider prebiotically plausible alternatives to citrate that could potentially confer similar effects, such as short acidic peptides. We note that just such a peptide constitutes the heart of cellular RNA polymerases, where it binds and presents the catalytic Mg2+ ion in the active site of the enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aaron Engelhart, Christian Hentrich, Aaron Larsen, Neha Kamat and Anders Björkbom for discussions and help with manuscript preparation and Ariella Gifford for help with vesicle leakage experiments.

This work was supported in part by NASA Exobiology grant NNX07AJ09G. J.W.S. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Raw data are presented in the supplementary materials. The instructions for assembling the Liposome Dialyzer are available at http://molbio.mgh.harvard.edu/szostakweb/

References and Notes

- 1.Gilbert W. Origin of life: The RNA world. Nature. 1986;319:618. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joyce GF. RNA evolution and the origins of life. Nature. 1989;338:217. doi: 10.1038/338217a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebicki JM, Hicks M. Ufasomes are stable particles surrounded by unsaturated fatty acid membranes. Nature. 1973;243:232. doi: 10.1038/243232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deamer DW, Dworkin JP. Chemistry and physics of primitive membranes. Top Curr Chem. 2005;1 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szostak JW. The eightfold path to non-enzymatic RNA replication. J Sys Chem. 2012;3 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman JC, Lenz TK, Hud NV, Williams LD. Cations in charge: magnesium ions in RNA folding and catalysis. Curr Opin Struct Bio. 2012;22:262. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansy SS, Szostak JW. Thermostability of model protocell membranes. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805086105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deck C, Jauker M, Richert C. Efficient enzyme-free copying of all four nucleobases templated by immobilized RNA. Nat Chem. 2011;3:603. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covington AK, Danish EY. Measurement of Magnesium Stability Constants of Biologically Relevant Ligands by Simultaneous Use of pH and Ion-Selective Electrodes. J Solution Chem. 2009;38:1449–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walser M. Ion Association V. Dissociation Constants For Complexes of Citrate With Sodium, Potassiun, Calcium, And Magnesium Ions. J Phys Chem. 1961;65:159–161. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson CK. X-Ray Crystal Analysis of the Substrates of Aconitase. V. Magnesium Citrate Decahydrate. Acta Crystallogr. 1965;18:1004. doi: 10.1107/s0365110x6500244x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butch C, et al. Production of Tartrates by Cyanide-Mediated Dimerization of Glyoxylate: A Potential Abiotic Pathway to the Citric Acid Cycle. J Am Chem Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja405103r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce GF, Inoue T, Orgel LE. Non-enzymatic template-directed synthesis on RNA random copolymers. Poly(C, U) templates. J Mol Biol. 1984;176:279. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu TF, Adamala K, Zhang N, Szostak JW. Photochemically driven redox chemistry induces protocell membrane pearling and division. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:9828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203212109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu TF, Szostak JW. Coupled growth and division of model protocell membranes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5705. doi: 10.1021/ja900919c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.