Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to investigate the association of mitral annular calcification (MAC), aortic annular calcification (AAC), and aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc) with covert magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-defined brain infarcts.

Background

Clinically silent brain infarcts defined by MRI are associated with increased risk of cognitive decline, dementia, and future overt stroke. Left sided cardiac valvular / annular calcifications are suspected as risk factors for clinical ischemic stroke.

Methods

2,680 Cardiovascular Health Study participants without clinical history of stroke or transient ischemic attack underwent both brain MRI (1992–93) and echocardiography (1994–95).

Results

The mean age of the participants was 74.5 years ± 4.8 and 39.3% were men. The presence of any annular / valvular calcification (either MAC or AAC or AVSc), MAC alone, or AAC alone were significantly associated with a higher prevalence of covert brain infarcts in unadjusted analyses (p < 0.01 for all). In models adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and congestive heart failure, the presence of any annular / valve calcification remained associated with covert brain infarcts [RR 1.24 (95% CI 1.05, 1.47)]. The degree of annular / valvular calcification severity showed a direct relation with the presence of covert MRI findings.

Conclusion

Left-sided cardiac annular / valvular calcification are associated with covert MRI-defined brain infarcts. Further study is warranted to identify mechanisms and determine whether intervening on the progression of annular / valvular calcification could reduce the incidence of covert brain infarcts as well as the associated risk of cognitive impairment and future stroke.

Keywords: Covert Brain Infarcts, Aortic Valve, Mitral Valve, Calcification, Epidemiology

Mitral annular calcification (MAC), aortic annular calcification (AAC), and aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc) are characterized by calcium and lipid deposition on the fibrous skeleton at the base of the heart (mitral and aortic annuli) and on the aortic cusps respectively.(1–4) Clinical precursors of atherosclerosis are also risk factors for MAC and AVSc.(5) MAC and AVSc have been documented to be independent predictors of cardiovascular events,(5,6) although their relationship with clinical ischemic stroke remains less well defined. Not all studies examining the association between MAC and stroke have reported a significant relationship,(7–12) whereas an association between AV disease and overt stroke has only been demonstrated in the presence of AV stenosis and not with AVSc.(13)

With the increased use of MRI imaging, covert brain infarcts and white matter lesions (WMLs) are often seen in elderly people free of prior clinical transient ischemic attacks and stroke. (14–16) These covert MRI findings are not benign since they are associated with cognitive decline and future overt stroke.(17) Covert brain infarcts and WMLs are thought to have a vascular origin possibly related to microembolism along with microvascular ischemia.(18) Data are lacking on prevalence and relevance of these covert MRI findings in people with MAC, AAC and AVSc and without a history of transient ischemic attack and stroke. Whether cardiac annular and valvular calcification is related to prevalent covert brain infarcts and WMLs independent of concurrent clinical predictors remains untested.

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a large community-based study of cardiovascular disease in the elderly that included cranial MRI and echocardiography. We used data from the CHS to investigate the hypothesis that the prevalence of covert brain infarcts and WMLs would be higher in participants with MAC and calcific AV disease (defined as AVSc and AAC) than those without.

Methods

Study Population

Details of the CHS have been published elsewhere.(19,20) Briefly, a random sample of men and women aged 65 years and older were recruited from Medicare eligibility lists in four U.S. communities (Sacramento County, California; Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Between 1989–1990, the original study enrolled 5,201, and between 1992–1993 an additional 687 African Americans were enrolled. Exclusions included the use of a wheelchair, institutionalization, inability to give informed consent, plans to move away from the area within 3 years, or active treatment for malignancy. Each participating center received institutional review board approval, and all participants gave informed consent.

Of the 5888 elderly participants in the CHS, 3101 had both an MRI in 1992–1993 and an echocardiogram in 1994–1995. We excluded 245 participants with a clinical history of stroke or transient ischemic attack before their MRI or echocardiogram. An additional 140 subjects were excluded in whom necessary variables from the MRI or echocardiogram could not be defined, as were 36 participants who were missing covariate information. Thus, our sample size for our primary analysis of covert brain infarcts included 2680 participants. When WMLs were analyzed, our sample size included 2665 participants since 15 participants were further excluded for lack of a WM grade measurement.

Measurements

The baseline examination included a standardized interviews conducted by trained CHS study personnel assessing demographics, plus a variety of risk factors, including smoking, alcohol intake, history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, congestive heart failure, and prior coronary heart disease. The physical examination included standardized measurements of height, weight, and seated blood pressure measured with a random-zero sphygmomanometer. Blood pressure was measured in triplicate 5 minutes apart. All patients were instructed to fast. Diabetes was defined by clinical history of diabetes, fasting glucose levels >126 mg/dL or the use of a diabetic medication. Lipid measurements were made at the Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research and low-density lipoprotein was calculated using the Friedewald equation.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiograms were recorded on videotape using a Toshiba SSH-160A ultrasound machine during the 1994–1995 Cardiovascular Health Study examination as detailed previously.(21,22) The echocardiograms were evaluated at a centralized core laboratory (Georgetown University, Washington, DC) by observers blinded to participants’ clinical history. Definitions of AVSc, MAC, and AAC were the same as in previous CHS studies.(2,23) AVSc was identified as focal or diffuse aortic cusp thickening, stiffness, and/or increased echogenicity (calcification) with normal aortic cusp excursion and a peak trans-aortic valve flow velocity <2.0 m/s. MAC was defined by increased echodensity located at the junction of the atrioventricular groove and posterior mitral leaflet on the parasternal long-axis, short axis, or apical fourchamber view. The presence of AAC was similarly defined as increased echodensity of the aortic root at the insertion of the aortic cusps

MRI

Brain MRI was performed and interpreted without any information about the participant, as previously described.(24) A brain infarct was defined as a low signal intensity area of at least 3 mm on T1-weighted images that was also visible as a hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted images. MRI-defined brain infarcts were categorized as absent or present. WMLs were considered present if visible as hyperintense on proton-density and T2-weighted images, without prominent hypointensity on T1-weighted scans. WMLs were assigned a grade from 0 (best) to 9 (worst) and analyzed as a dichotomous variable with WM grade greater than 4. Covert MRI findings were defined as: (1) high WM grade of 5 or more; (2) presence of infarcts; or (3) both. Infarct location was determined as: cortical infarcts (any infarct involving the cortex or the cerebellar surface) and non-cortical infarcts (any infarct involving basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule, or centrum ovale and sparing the cortical surface). Non-cortical infarcts were almost entirely less than 20 mm.(25)

Secondary Exposure Variables

Echocardiographic left atrial dimensions were defined in the parasternal long-axis view, as described.(26) Measurement of left ventricular internal dimensions in diastole was used to determine left ventricular mass using established validated methodology.(26) Left ventricular mass was normalized for height2.7 according to published guidelines.(26) Left ventricular hypertrophy was defined based on established left ventricular mass cutoffs.(26) Atrial fibrillation as detected on the ECG at the time of examination or by self report at any visit up through the last visit before the MRI. Measurement of NT-pro brain naturetic peptide (BNP) was performed with the commercially available immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics Elescys proBNP Assay, Indianapolis, IN) on the Elescys 2010 instrument. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement was performed using a latex-enhanced reagent (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL). Cystatin C concentration was measured using a BNII nephelometer (N Latex cystatin-C, Dade Behring Inc, Deerfield, IL). NT-proBNP, CRP, and cystatin C were all log transformed and analyzed as continuous variables.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a cross-sectional analysis in participants without a history of clinical transient ischemic attack or stroke. Echocardiographic variables of annular and valvular calcification were our exposure variables to be related to the presence of MRI findings. Because prevalence of brain infarcts was close to 27% in our population, unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by relative risk regression(27) using Poisson regression with robust standard errors. MAC, AAC, and AVSc were analyzed as separate and combined independent variables. Analyses tested whether: 1) MAC was related to brain infarct; 2) MAC was related to high WM grade; and 3) MAC is related to any MRI finding. This analysis was repeated for AAC and AVSc, as well as for combined measures of annular / valvular calcification. Specifically, the variable ‘any annular / valvular calcification’ included the presence of either MAC or AAC or AVSc, whereas the variable ‘all annular / valvular calcification’ included the presence of MAC and AAC and AVSc together; ‘any AV calcification’ included AAC and AVSc. Our primary exposure of interest, specified a priori, was the presence of the combined measures of any annular / valvular calcification. The primary outcome of interest was the presence of covert brain infarcts. All other exposure and outcome measures were secondary. Potential confounders associated with annular / valvular calcification and established stroke risk factors were included in adjusted models: model 1 (age, sex, race adjusted) and model 2 (adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, average systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, and presence of coronary heart disease or congestive heart failure at closest clinic visit prior to MRI). Based on their known association with cerebrovascular events (left atrial enlargement, atrial fibrillation, LV hypertrophy) or their potential role as mediators / confounders (NT-proBNP, CRP, cystatin C), independent predictor variables were analyzed in a priori exploratory models: model 3 (model 1 + left ventricular hypertrophy and left atrial enlargement) and model 4 (model 1 + atrial fibrillation, CRP, NT-proBNP, and cystatin C). We used χ2 and regression analysis to examine associations in strata defined by infarct location: cortical infarct vs. non-cortical infarct. Individuals with multiple infarcts were included in the cortical infarct group if at least one infarct was cortical and in the non-cortical group if all infarcts were non-cortical. In these analyses, those infarcts not of the type being examined in the particular stratum were excluded. STATA 10.1 (College Station, TX: StataCorp) was used for all analyses.

Results

The mean age of the participants in these analyses was 74.5 years (sd = 4.8) and 39.3% were men. MAC was found in 40.1%, AAC in 44.3%, and AVSc in 53.3%. The prevalence of any annular / valvular calcification was 77.0%, whereas the prevalence for all calcification was 16.0%. Age, creatinine level, male sex, white race, history of coronary heart disease, NT-proBNP and cystatin C levels were all associated with annular / valvular calcification (MAC, AAC, or AVSc) in bivariate comparisons (Table 1). Neither total cholesterol nor HDL-cholesterol individually showed a significant association with any annular / valvular calcification (p = 0.08), but the total cholesterol /HDL ratio did (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Total Study Cohort and According to Annular / Valvular Calcification Status

| Risk Factors | Entire cohort (N = 2680) |

Any annular / valve calcification* (n = 2063) |

w/o annular / valve calcification (n = 617) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.53 ± 4.81 | 74.79 ± 4.87 | 73.67 ± 4.52 | <0.0001 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 26.68 ± 4.37 | 26.62 ± 4.31 | 26.86 ± 4.56 | 0.22 |

| Male | 1053 (39.3%) | 842 (40.8%) | 211 (34.2%) | 0.003 |

| White race | 2275 (84.9%) | 1769 (85.8%) | 506 (82.0%) | 0.02 |

| Physical activity (Kcal) | 1620.59 ± 1837.96 | 1621.16 ± 1850.79 | 1618.67 ± 1795.90 | 0.98 |

| Serum Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.03 ± 0.26 | 1.04 ± 0.27 | 1.01 ± 0.22 | 0.003 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 134.22 ± 20.13 | 134.20 ± 19.82 | 134.28 ± 21.15 | 0.93 |

| TC/HDL ratio | 4.09 ± 1.22 | 4.12 ± 1.21 | 3.99 ± 1.24 | 0.027 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dl | 209.31 ± 37.34 | 210.00 ± 37.55 | 207.00 ± 36.56 | 0.081 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 54.40 ± 14.73 | 54.12 ± 14.61 | 55.32 ± 15.07 | 0.076 |

| Smoker | ||||

| Never Smoker | 1224 (45.7%) | 923 (44.7%) | 301 (48.8%) | |

| Former Smoker | 1219 (45.5%) | 963 (46.7%) | 256 (41.5%) | |

| Current Smoker | 237 (8.8%) | 177 (8.6%) | 60 (9.7%) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes | 317 (11.8%) | 247 (12.0%) | 70 (11.4%) | 0.85 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 466 (17.4%) | 380 (18.4%) | 86 (13.9%) | 0.01 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 92 (3.4%) | 77 (3.7%) | 15 (2.4%) | 0.12 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl | 4.68 ± 7.71 | 4.68 ± 8.02 | 4.68 ± 6.57 | 0.99 |

| Natural log of NT-proBNP | 229.08 ± 427.25 | 245.57 ± 466.02 | 171.80 ± 241.27 | 0.0006 |

| Natural log of Cystatin C | 1.07 ± 0.26 | 1.08 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.21 | 0.003 |

| Left atrial size, (cm) | 4.00 ± 0.93 | 4.01 ± 1.01 | 3.94 ± 0.58 | 0.084 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 202 (7.5%) | 173 (8.4%) | 29 (4.7%) | 0.002 |

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophy | 474 (24.4%) | 18 (26.3%) | 91 (18.8%) | 0.001 |

any annular / valve calcification combines presence of MAC, AAC, or AVSc

Continuous data presented as means ± standard deviation, Categorical or binary data as percent prevalence (%)

Abbreviations: HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein

Effects on Covert Brain Infarcts

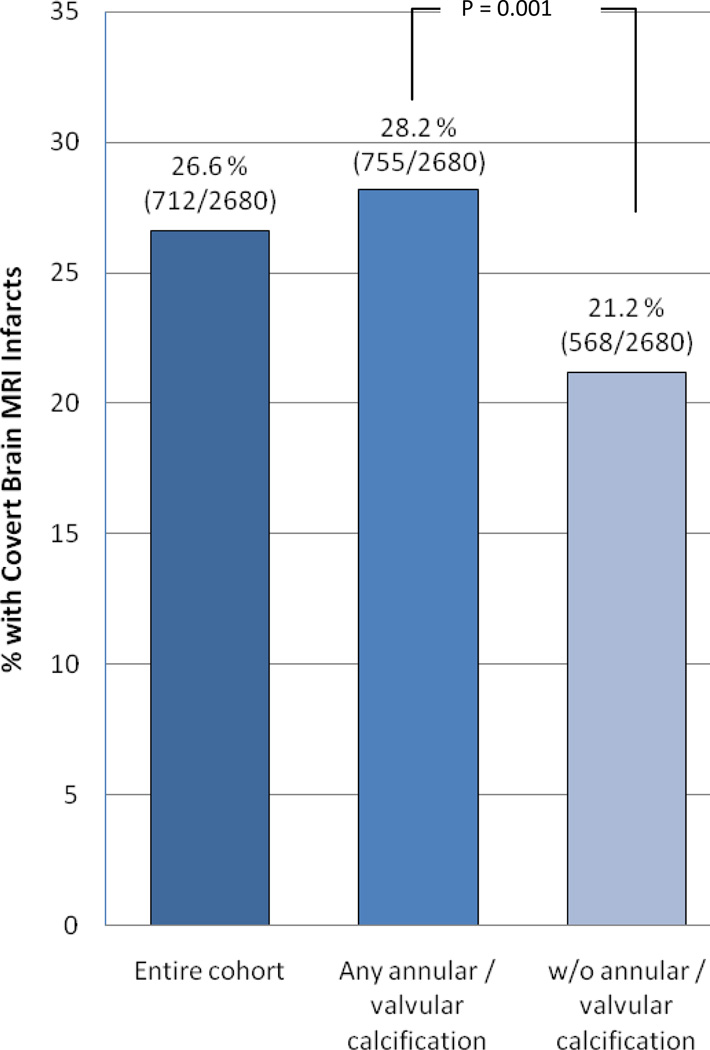

On MRI, 712 (26.6%) participants had 1 or more covert infarcts and 161 (6.0%) had a WM grade >4. The presence of covert brain infarcts was significantly associated with detection of any annular / valvular calcification (p = 0.001) in bivariate comparisons (Figure 1). Relative risk regression analysis showed that any annular / valvular calcification, MAC, AAC and any AV calcification were associated with the presence of covert brain infarcts in unadjusted models (Table 2). In minimally adjusted models, the presence of MAC, any AV calcification and any annular / valvular calcification were associated with covert brain infarcts. In models adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, creatinine, coronary heart disease and congestive heart failure, only the presence of any annular / valve calcification was associated with covert brain infarcts. Additional a priori exploratory models (Models 3 and 4) adjusting for factors such as left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial size, NT-proBNP, CRP, atrial fibrillation, and cystatin C did not meaningfully change the results. (Table 2) When ‘all annular / valvular calcification’ was included as the exposure variable, only unadjusted and minimally adjusted models were statistically significant (data not shown).

Figure 1. Proportion of participants with covert brain infarcts according to annular / valve lesion status.

The prevalence of covert brain infarcts was significantly higher in the annular / valve calcification group (p=0.001).

Table 2.

Risk Ratios (95% CI) describing the Association between Mitral Annular Calcification, Aortic Annular Calcification and Aortic Valve Sclerosis with Covert Brain Infarcts

| Unadjusted | p-val | Model 1 | p-val | Model 2 | p-val | Model 3 | p-val | Model 4 | p-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any annular / valve calcification | 1.33 (1.12, 1.57) | 0.001 | 1.27 (1.08, 1.50) | 0.005 | 1.24 (1.05, 1.47) | 0.011 | 1.24 (1.02, 1.50) | 0.035 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.53) | 0.013 |

| MAC | 1.21 (1.06, 1.37) | 0.003 | 1.15 (1.01, 1.30) | 0.035 | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) | 0.081 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 0.303 | 1.11 (0.97, 1.28) | 0.140 |

| AAC | 1.17 (1.03, 1.33) | 0.014 | 1.11 (0.98, 1.26) | 0.108 | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) | 0.179 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 0.290 | 1.08 (0.94, 1.24) | 0.288 |

| AVSc | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 0.224 | 1.07 (0.94, 1.21) | 0.323 | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) | 0.538 | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) | 0.559 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.24) | 0.313 |

| Any AV Calcification@ | 1.21 (1.05, 1.41) | 0.009 | 1.16 (1.00, 1.35) | 0.044 | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) | 0.075 | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32) | 0.240 | 1.15 (0.98, 1.35) | 0.096 |

Any AV calc = combination of Aortic Annular Calcification or Aortic Valve Sclerosis

Model 1 = Adjusted for age, sex, race (white, non-white)

Model 2 = Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

Model 3 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, LV hypertrophy and left atrial dimension (cm)

Model 4 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, and atrial fibrillation

Effects on High WM grade

With high WM grade as the outcome, the presence of any annular / valvular calcification, any AV calcification, and AAC were significant predictors associated in unadjusted models. Only the presence of any annular / valvular calcification was associated with high WM grade in minimally adjusted and fully adjusted models. The association of any AV calcification with WM grade was only marginally significant. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Risk Ratios (95% CI) describing the Association between Aortic Valve Sclerosis, Mitral Annular Calcification and Aortic Annular Calcification with high WM grade (>4)

| Unadjusted | p-val | Model 1 | p-val | Model 2 | p-val | Model 3 | p-val | Model 4 | p-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any annular / valve calcification | 1.8 (1.17, 2.77) | 0.008 | 1.59 (1.04, 2.45) | 0.033 | 1.61 (1.04, 2.49) | 0.033 | 1.65 (0.98, 2.77) | 0.058 | 1.63 (0.99, 2.70) | 0.055 |

| MAC | 1.34 (0.99, 1.81) | 0.055 | 1.14 (0.85, 1.54) | 0.390 | 1.16 (0.86, 1.57) | 0.334 | 1.13 (0.79, 1.62) | 0.510 | 1.12 (0.80, 1.58) | 0.502 |

| AAc | 1.48 (1.10, 2.00) | 0.010 | 1.25 (0.92, 1.69) | 0.154 | 1.23 (0.91, 1.68) | 0.177 | 1.29 (0.90, 1.85) | 0.173 | 1.23 (0.87, 1.74) | 0.237 |

| AvSc | 1.29 (0.95, 1.76) | 0.099 | 1.25 (0.92, 1.69) | 0.153 | 1.24 (0.91, 1.68) | 0.166 | 1.37 (0.94, 1.99) | 0.097 | 1.39 (0.98, 1.97) | 0.061 |

| Any AV Calc@ | 1.64 (1.13, 2.38) | 0.009 | 1.44 (1.00, 2.10) | 0.053 | 1.45 (1.00, 2.11) | 0.050 | 1.60 (1.01, 2.53) | 0.045 | 1.49 (0.97, 2.28) | 0.068 |

Any AV calc = combination of Aortic Annular Calcification or Aortic Valve Sclerosis

Model 1 = Adjusted for age, sex, race (white, non-white)

Model 2 = Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

Model 3 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, LV hypertrophy and left atrial dimension (cm)

Model 4 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, and atrial fibrillation

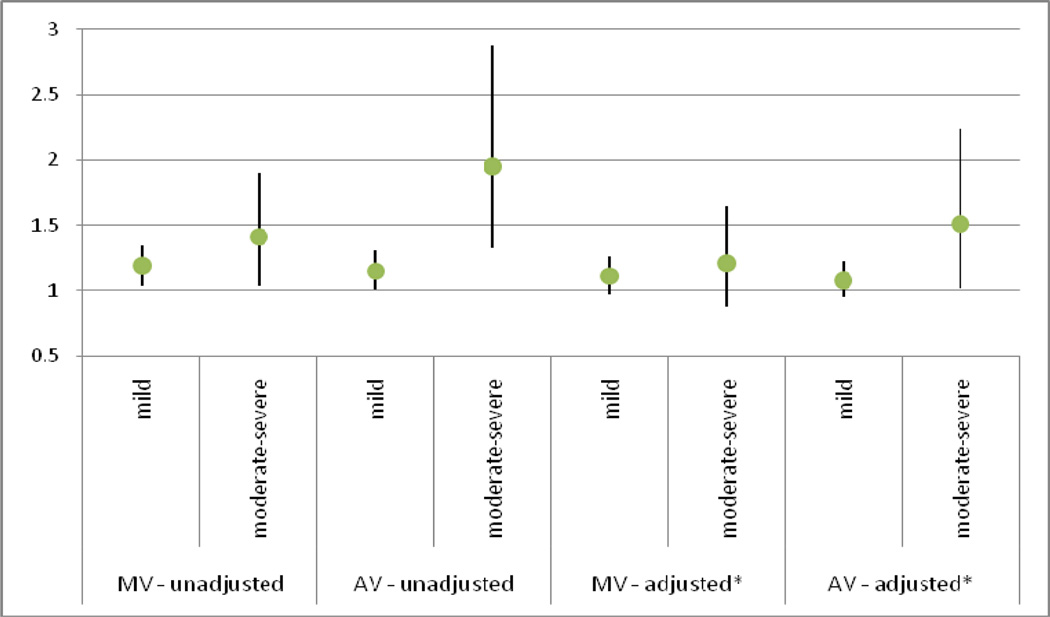

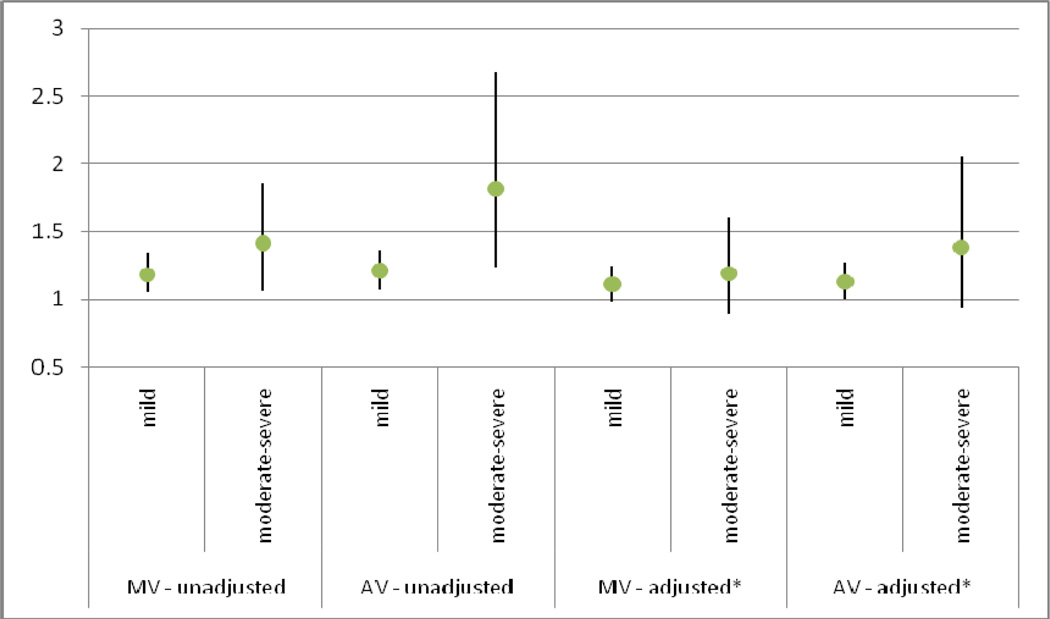

Effects on Covert Brain Infarcts and High WM grade

When high WM grade and brain infarcts were considered as a combined outcome (Table 4), results were consistent with our above models. The presence of any annular / valvular calcification, any AV calcification, MAC and AAC showed significant association with combined outcomes in our unadjusted and minimally adjusted models. In our fully adjusted model and exploratory models, only the presence of any annular / valvular calcification, any AV calcification and AAC were related to the combined outcome. AVSc alone was not associated with any brain MRI finding in any of our models. The degree of valvular calcification showed a direct relation with the presence of covert brain MRI lesions. In fully adjusted models, moderate-to-severe annular / valvular calcification in the mitral and aortic position showed a 21% and 19% higher risk of covert brain infarcts and a 51% and 38% higher risk of covert brain infarcts and/or high WM grade than no valvular lesions, respectively, although the difference was only statistically significant for the relation of AV lesions with covert brain infarcts. (Figures 2 & 3).

Table 4.

Risk Ratios (95% CI) describing the Association between Aortic Valve Sclerosis, Mitral Annular Calcification and Aortic Annular Calcification with either Covert Brain Infarcts and/or high WM grade (>4)

| Unadjusted | p-val | Model 1 | p-val | Model 2 | p-val | Model 3 | p-val | Model 4 | p-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any annular / valve calcification | 1.39 (1.19, 1.64) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.13, 1.56) | 0.001 | 1.31 (1.11, 1.54) | 0.001 | 1.30 (1.07, 1.57) | 0.007 | 1.33 (1.11, 1.59) | 0.002 |

| MAC | 1.20 (1.07, 1.35) | 0.002 | 1.13 (1.00, 1.27) | 0.042 | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) | 0.074 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) | 0.307 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.25) | 0.169 |

| AAc | 1.22 (1.09, 1.38) | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) | 0.021 | 1.14 (1.01, 1.28) | 0.035 | 1.15 (0.99, 1.32) | 0.062 | 1.13 (0.99, 1.29) | 0.072 |

| AvSc | 1.10 (0.97, 1.24) | 0.123 | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) | 0.201 | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | 0.326 | 1.06 (0.92, 1.23) | 0.394 | 1.09 (0.95, 1.24) | 0.212 |

| Any AV Calc@ | 1.28 (1.11, 1.47) | 0.001 | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40) | 0.006 | 1.20 (1.05, 1.39) | 0.009 | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) | 0.043 | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | 0.016 |

Any AV calc = combination of Aortic Annular Calcification or Aortic Valve Sclerosis

Model 1 = Adjusted for age, sex, race (white, non-white)

Model 2 = Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

Model 3 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, LV hypertrophy and left atrial dimension (cm)

Model 4 = Adjusted for age, race, sex, NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, and atrial fibrillation

Figure 2. Risk Ratios by valve calcification severity predicting Covert Brain Infarcts.

The degree of valvular calcification showed a direct relation with the presence of covert brain MRI lesions. In fully adjusted models, moderate-to-severe annular / valvular calcification in the mitral and aortic position showed a 21% and 19% higher risk of covert brain infarcts than no valvular lesions,

MV = mitral valve; AV = aortic valve

* Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

* Comparison group = those with no MV or AV calcification respectively

Figure 3. Risk Ratios by valve calcification severity predicting either Covert Brain Infarcts and/or White Matter Lesions.

The degree of valvular calcification showed a direct relation with the presence of covert brain MRI lesions. In fully adjusted models, moderate-to-severe annular / valvular calcification in the mitral and aortic position showed a 51% and 38% higher risk of covert brain infarcts and/or high WM grade than no valvular lesions,

MV = mitral valve; AV = aortic valve

* Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

* Comparison group = those with no MV or AV calcification respectively

Infarct Location Analysis

Of the 712 participants with covert infarcts, 65 (9%) had any cortical infarcts and 647 (91%) had non-cortical infarcts. The prevalence of cortical infarcts vs. non-cortical infarcts in those with vs. without any annular / valvular calcification was not significantly different (p = 0.51). Relative risk regression analysis of any annular / valvular calcification using model 2 showed that RRs were only slightly stronger for any cortical infarct than for non-cortical infarcts but as expected given the small number of cortical infarcts, the association for this stratum was not significant. Table 5

Table 5.

Covert Brain Infarct Location According to Calcific Annular / Valve Disease Status

| Infarct Location | In Those Without Any annular / valve calcification |

In Those With Any annular / valve calcification |

RR (CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Cortical | 18% (121/647) | 81% (526/647) | 1.23 (1.03, 1.47) |

| Cortical | 15% (10/65) | 85% (55/65) | 1.64 (0.84, 3.21) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, physical activity, creatinine, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes, presence of Coronary Heart Disease or Congestive Heart Failure at closest clinic visit prior to brain MRI

Discussion

In a community-based sample of older adults, we found that the presence of any left-sided cardiac annular / valvular calcification is significantly associated with a 33% greater risk of covert brain infarcts on MRI, namely in participants without a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. This observed association persisted after full adjustment for potential confounders. Similar associations were observed with the presence of high WM grade and when covert brain infarcts and high WM grade were analyzed as a combined MRI-defined outcome. Additionally, we utilized explanatory models with comprehensive adjustment for clinical confounders and echocardiographic / inflammatory covariates. Our findings remained independent of NT-proBNP, CRP, and cystatin C suggesting that the primary association represents more than simply shared risk factors.

Prior studies have reported inconsistent findings with respect to the association between left-sided cardiac annular or valvular calcifications and the risk of clinical stroke. Mitral and aortic annular calcification is characterized by calcium and lipid deposition in the annular fibrosa, whereas AVSc results from similar accumulation involving the AV leaflets.(1,28) Although numerous case reports provide evidence of brain infarction due to calcific emboli from aortic valves,(29–33) an independent association between AV calcification and clinical stroke has only been demonstrated in the presence of hemodynamically significant AV stenosis.(4,13) Several studies(7,9,10) have detailed a relationship between MAC and clinical stroke, but this was not confirmed by a prior report from CHS or by a separate study using a matched control group.(34) (3,8) The weight of the evidence, although varied and seemingly conflicted, favors the presence of some association between mitral and/or aortic calcification with clinical ischemic stroke.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate an association between left-sided cardiac annular or valvular calcifications with covert brain infarcts. Most studies of calcific AV disease do not detail the presence of concomitant AAC and it may be that AAC is an underappreciated exposure in stroke risk. Our results are important because covert MRI-defined brain infarcts and WMLs are associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline and future stroke.(14,16,17) Implications of our findings are that the relationship between left-sided cardiac annular / valvular calcifications with brain infarcts may have been underestimated in prior studies that considered only clinical ischemic stroke. This relationship may be stronger and of greater clinical relevance when both covert and overt brain infarcts are considered.

Several explanations may account for the independent association of annular / valvular calcific lesions with covert brain-MRI defined infarcts. These cardiac lesions may not be just markers of stroke risk based on their association atherosclerotic vascular disease(35,36) but may also play a causative role. Embolization from left-sided cardiac annular or valvular calcifications can vary from friable calcium deposits to non-calcific (thrombus) embolization.(32,37,38) Evidence of systemic embolism to cerebral, coronary, renal, retinal arteries and the peripheral circulation has been found on autopsy in one-third of cases with calcific AV disease (30) with evidence of organized microthrombi observed in 53% of calcified aortic valves.(39) Wilson et al., noted calcific AV disease as the most common cardiac abnormality among patients with central retinal artery occlusion.(32) A potential mechanistic pathway for micothrombi formation on left-sided calcified structures could involve turbulent blood flow at the mitral or aortic position, followed by fragmentation of red cells and release of adenosine diphosphate and thromboplastin, with resulting microthrombus formation and non-calcific embolism.(39,40) The incidence of cerebral thromboembolism from left-sided cardiac annular or valvular calcifications is likely underestimated. Patients may remain asymptomatic in a percentage of cases depending on the size of emboli.(30) In addition, the neurologic symptoms may be attributed to other competing causes such as low cardiac output, small vessel disease or atrial fibrillation. A caveat to this argument is that most infarcts in CHS were non-cortical which are typically not cardioembolic,(25) suggesting that embolism may not be the only explanation for covert infarcts in those with annular / valvular calcification. The number of cortical infarcts in these CHS participants was not sufficient to answer the question of whether or not the risk of covert infarcts with any annular / valvular calcification differs by infarct location.

Regarding WM disease and annular / valvular calcification, the mechanism of association is somewhat unclear. WM disease is found in those with vascular dementia and may be the consequence of microvasculopathy, edema, gliosis, as well as chronic ischemia and small infarcts such as those caused by embolic calcific disease.(41) While it is true that both WM disease and annular / valvular calcification are common conditions in the elderly such that their association may be coincidental, the independent association after adjusting for age and multiple confounders argues against coincidence of common risk factors or residual confounding. Furthermore, the strength of association, as measured by risk ratios, for WM disease was greater than that for covert brain infarcts and annular / valvular calcification.

Strengths of our study include its large sample size and derivation from a well-defined community-based cohort. In the present study, 2-D visualization of annular / valvular calcification may have allowed for more accurate identification of calcification than was possible with M-mode examination performed in earlier published studies. In addition, we were able to adjust our models for markers of inflammation, echocardiographic variables, and other important potential confounders. Our study also has several limitations. First, we obtained brain MRIs one to two year before the echocardiographic examination. Thus, causality cannot be inferred. In doing this as a cross-sectional analyses, we are assuming that change in measures determined on the MRI is slow so that those variables remain close to what they would be had they been obtained at the time of the echocardiographic examination. Although the issue of reverse causality exists, it is not biologically plausible that covert brain infarcts would cause annular / valvular calcification. Moreover, because such covert infarcts would not lead to immediate disability, there would be less of a short-term clinical impact of these lesions than would be observed from clinically apparent overt stroke. Although our statistical models were extensive, unmeasured confounders could potentially explain the observed associations. Lastly, the majority of CHS participants were Caucasian, possibly reducing generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups of older adults.

In conclusion, our results indicate that left-sided cardiac annular / valvular calcification is associated with covert MRI-defined brain infarcts. Prior estimates of the association between calcific annular / valve disease and stroke are likely underestimated since they only accounted for clinical overt stroke. Further study is warranted to identify the mechanisms relating these two sets of findings in the heart and brain and determine whether intervening on the progression of calcific annular / valvular disease can reduce the incidence of these covert MRI findings as well as the associated risk of cognitive decline and future stroke.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported by contract numbers N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, grant number U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

Dr. Rodriguez is partially supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Amos Medical Faculty Development Program and a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23 HL079343-01A3).

ABBREVIATION LIST

- MAC

mitral annular calcification

- AAC

aortic annular calcification

- AVSc

aortic valve sclerosis

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- RR

risk ratios

- WML

white matter lesions

- BNP

brain naturetic peptide

- CRP

C- reactive protein

- HDL

High-Density Lipoprotein

References

- 1.Ashida T, Kiraku J, Takahashi N, Sugiyama T, Fujii J. Experimental study on the pathogenesis of mitral annular calcification: calcium deposits in mitral complex lesions induced by vagal stimulation in rabbits. J Cardiol. 1997;29(Suppl 2):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barasch E, Gottdiener JS, Larsen EK, Chaves PH, Newman AB, Manolio TA. Clinical significance of calcification of the fibrous skeleton of the heart and aortosclerosis in community dwelling elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Am Heart J. 2006;151:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boon A, Cheriex E, Lodder J, Kessels F. Cardiac valve calcification: characteristics of patients with calcification of the mitral annulus or aortic valve. Heart. 1997;78:472–474. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.5.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosmi JE, Kort S, Tunick PA, et al. The risk of the development of aortic stenosis in patients with "benign" aortic valve thickening. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2345–2347. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, et al. Aortic valve sclerosis and aortic atherosclerosis: different manifestations of the same disease? Insights from a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:827–834. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox CS, Vasan RS, Parise H, et al. Mitral annular calcification predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:1492–1496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000058168.26163.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin EJ, Plehn JF, D'Agostino RB, et al. Mitral annular calcification and the risk of stroke in an elderly cohort. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:374–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208063270602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boon A, Lodder J, Cheriex E, Kessels F. Mitral annulus calcification is not an independent risk factor for stroke: a cohort study of 657 patients. J Neurol. 1997;244:535–541. doi: 10.1007/s004150050140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I, Gutstein H. Association of mitral annular calcium with new thromboembolic stroke at 44-month follow-up of 2,148 persons, mean age 81 years. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:105–106. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00854-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kizer JR, Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, et al. Mitral annular calcification, aortic valve sclerosis, and incident stroke in adults free of clinical cardiovascular disease: the Strong Heart Study. Stroke. 2005;36:2533–2537. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190005.09442.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause I, Lev S, Fraser A, et al. Close association between valvar heart disease and central nervous system manifestations in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1490–1493. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morelli S, Bernardo ML, Viganego F, et al. Left-sided heart valve abnormalities and risk of ischemic cerebrovascular accidents in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12:805–812. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu468oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:142–147. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:1401–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056521.67546.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longstreth WT., Jr Brain vascular disease overt and covert. Stroke. 2005;36:2062–2063. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000179040.36574.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeer SE, Hollander M, van Dijk EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2003;34:1126–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000068408.82115.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1215–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, et al. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. Jama. 2004;291:427–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–277. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, et al. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free-living elderly subjects: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:630–634. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novaro GM, Katz R, Aviles RJ, et al. Clinical factors, but not C-reactive protein, predict progression of calcific aortic-valve disease: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1992–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longstreth WT, Jr, Arnold AM, Beauchamp NJ, Jr, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of worsening white matter on serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2005;36:56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149625.99732.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longstreth WT, Jr, Bernick C, Manolio TA, Bryan N, Jungreis CA, Price TR. Lacunar infarcts defined by magnetic resonance imaging of 3660 elderly people: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1217–1225. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sell S, Scully RE. Aging Changes in the Aortic and Mitral Valves. Histologic and Histochemical Studies, with Observations on the Pathogenesis of Calcific Aortic Stenosis and Calcification of the Mitral Annulus. Am J Pathol. 1965;46:345–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brockmeier LB, Adolph RJ, Gustin BW, Holmes JC, Sacks JG. Calcium emboli to the retinal artery in calcific aortic stenosis. Am Heart J. 1981;101:32–37. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holley KE, Bahn RC, McGoon DC, Mankin HT. Spontaneous Calcific Embolization Associated with Calcific Aortic Stenosis. Circulation. 1963;27:197–202. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.27.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira-Filho J, Massaro AR, Yamamoto F, Bustamante L, Scaff M. Stroke as the first manifestation of calcific aortic stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2000;10:413–416. doi: 10.1159/000016099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson JH, Cranley JJ. Recurrent calcium emboli in a patient with aortic stenosis. Chest. 1989;96:1433–1434. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.6.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vernhet H, Torres GF, Laharotte JC, et al. Spontaneous calcific cerebral emboli from calcified aortic valve stenosis. J Neuroradiol. 1993;20:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardin JM, McClelland R, Kitzman D, et al. M-mode echocardiographic predictors of six- to seven-year incidence of coronary heart disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and mortality in an elderly cohort (the Cardiovascular Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karas MG, Francescone S, Segal AZ, et al. Relation between mitral annular calcium and complex aortic atheroma in patients with cerebral ischemia referred for transesophageal echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler Y, Levinger U, Koren A, et al. Relation of nonobstructive aortic valve calcium to carotid arterial atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1102–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rancurel G, Marelle L, Vincent D, Catala M, Arzimanoglou A, Vacheron A. Spontaneous calcific cerebral embolus from a calcific aortic stenosis in a middle cerebral artery infarct. Stroke. 1989;20:691–693. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamon M, Gomes S, Oppenheim C, et al. Cerebral microembolism during cardiac catheterization and risk of acute brain injury: a prospective diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2006;37:2035–2038. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000231641.55843.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein PD, Sabbah HN, Pitha JV. Continuing disease process of calcific aortic stenosis. Role of microthrombi and turbulent flow. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson S. Platelets in hemostasis. In: Seegers W, editor. Blood Clotting Enzymology. New York: Academic Press; 1967. pp. 379–420. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breteler MM, van Swieten JC, Bots ML, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, vascular risk factors, and cognitive function in a population-based study: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1994;44:1246–1252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]