Abstract

Background

Emotional blunting is a major clinical feature of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). Assessing the change in emotional blunting may facilitate the differential diagnosis of this disorder and can quantify a major source of distress for patients' caregivers and families.

Methods

We evaluated investigator ratings on the Scale for Emotional Blunting (SEB) for 13 patients with bvFTD vs. 18 patients with early-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). The caregiver also performed SEB ratings for both the patients' premorbid behavior (“before” dementia-onset) and the patients' behavior on clinical presentation (“after”).

Results

Before dementia-onset, caregivers for both dementia groups reported normal SEB scores. After dementia-onset, both caregivers and investigators reported greater SEB scores for the bvFTD patients than AD patients. The bvFTD caregivers rated the patients as much more emotionally blunted than did the investigators. A change of ≥15 in caregiver SEB ratings of emotional blunting suggests bvFTD. The change in caregiver SEB ratings was positively correlated with bifrontal hypometabolism on FDG PET scans.

Conclusions

Changes in caregiver assessment of emotional blunting with dementiaonset can distinguish patients with bvFTD from those with AD, and they may better reflect the impact of emotional blunting than similar assessments made by clinicians/investigators.

Keywords: Scale for Emotional Blunting, Dementia, Caregiver

Introduction

Emotional blunting is a major aspect of bvFTD and underlies symptoms such as apathy and lack of empathy [1]. Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by behavioral disinhibition, apathy, lack of empathy, compulsive behaviors, changes in eating behavior, and a dysexecutive neuropsychological profile [2]. Investigators have characterized emotional blunting in bvFTD as “inappropriate emotional shallowness with unconcern and loss of emotional warmth, empathy, and sympathy, and an indifference to others” [3]. This symptom also contributes to the interpersonal disengagement and decreased social tact observed in these patients [4]. On neuropathology, emotional blunting may result from fronto-limbic involvement [5,6] and may be particularly associated with tau-positive neuropathological findings in bvFTD[7,8]. Boone and colleagues (2003) identified emotional blunting as a negative dementia symptom that differentiated individuals with FTD from Alzheimer's disease [9].

Although the presence of emotional blunting is helpful in the differential diagnosis of bvFTD patients [1,10], its clinical assessment poses several challenges. The construct is difficult to define and to accurately assess [2]. First of all, there are intra- individual differences in emotional blunting. Clinicians must consider differences in culture, degree of interpersonal affiliation, social milieu, and presumed premorbid functioning in determining what constitutes pathologic expression of affect [11,12]. Second, the accurate appraisal of emotional warmth or empathy requires a degree of relatedness that may be difficult for a clinician in an initial or brief medical evaluation to witness. For these two reasons, assessment by a close caregiver-informant may offer a more accurate appraisal of emotional blunting in patients, compared to clinician impressions alone [13,14]. In general, caregiver-based questionnaires of behavioral changes among patients with bvFTD have yielded relatively high sensitivities and specificities for discriminating bvFTD patients from those with AD [15,16]. Finally, this study differs in not just evaluating emotional blunting at one point in time, which is subject to individual differences in baseline emotional reactivity and expression, but in evaluating the individual's change in emotional blunting with the development of dementia.

In the present study, the primary goal is to compare changes in emotional blunting in bvFTD patients compared to AD patients. This study examines caregiver-informant ratings of emotional blunting before and after dementia-onset in a group of patients with bvFTD, compared to age-matched patients with AD. We further compare these caregiver ratings with those performed by a neuropsychologist after dementia-onset. We predict larger changes in emotional blunting among the bvFTD patients compared to the AD patients and that, given the greater personal relatedness; caregiver-informers will report greater emotional blunting than the clinician-researcher.

Methods

Participants

On approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Los Angeles and Veterans Administration Healthcare Center, Greater Los Angeles, participants were recruited from the UCLA Behavioral Neurology Program and Clinic. The participants were community-based, mild to moderately impaired dementia patients who underwent a clinical neurobehavioral evaluation. Patients unable to respond to basic neuropsychological testing or presenting with evidence of cortical infarction, other cortical or significant subcortical lesion on MRI of brain were excluded, i.e., all subcortical lesions except for mild white matter capping of the lateral ventricles (based on Fazekas scale lesion stage 1-3 [17]). In addition, for each participant the study enrolled a caregiver-informant who lived with the patient or interacted in person with the patient several times each week.

The bvFTD participants (n=13) in this study presented with progressive behavioral changes including declines in social interpersonal conduct, impairment in regulation of personal conduct, emotional blunting, and loss of insight into their disease, and they met criteria for ‘probable bvFTD’ based on the International Consensus Criteria for bvFTD [2]. The clinical diagnosis of probable bvFTD was confirmed by the presence of predominant frontal and anterior temporal hypometabolism on fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging.

The comparison group consisted of 18 patients with early-onset AD (age of onset < 65 years). These patients met the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for clinically probable AD after completing a diagnostic evaluation [18]. In order to match bvFTD patients, the AD group was matched according to demographic factors relevant to dementia course including age, gender, years of education, and ethnicity. The groups were not significantly different on clinical characteristics including disease duration, gross cognition on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and neuropsychological measures of executive functioning (See Table 1).

Table 1. Patient-Caregiver Characteristics: Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia vs. Early-Onset Alzheimer's Disease.

| bvFTD (n=13) | AD (n=18) | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.29 (11.22) | 58.56 (4.56) | n.s. |

| Gender – Male | 7 (53.8%) | 7 (38.8%) | n.s. |

| MMSEA | 22.92 (3.50) | 24.18 (3.94) | n.s. |

| Ethnicity White | 11(84.6%) | 17 (94.4%) | n.s. |

| Education (years) | 15.15 (2.47) | 15.94 (2.23) | n.s. |

| Disease duration | 3.38(1.26) | 3.94(2.23) | n.s. |

| Trail Making Part A (time sec) | 65.36 (50.91) | 66.82 (59.26) | T(22) = -0.06, p=.95 |

| Trail Making Part B (time sec) | 236.46 (96.29) | 194.44 (94.59) | T(20) = 0.98, p=.34 |

| Digits Forward (span length) | 8.27 (2.28) | 7.82 (2.78) | T(20) = 0.42, p=.68 |

| Digits Backward (span length) | 3.18 (2.31) | 3.73 (2.20) | T(20) =-0.57, p=.58 |

| Caregiver | bvFTD (n=13) | AD (n=18) | Sig |

| Age (years) | 58.91(15.7) | 62.75(11.3) | n.s. |

| Gender – Male | 4 | 9 | n.s. |

| Zarit Caregiver Burden total score | 45.0 (19.1) | 26.9 (16.6) | T(29)=2.8, p=.008 |

| Relationship (Spouse) | 12 (92.3%) | 15 (83.3%) | n.s. |

| Cohabiting with patient | 11(84.6%) | 17 (94.4%) | n.s. |

Missing data bvFTD n=1 and AD n=1

S.D or N% in parenthesis

Measures

The Scale for Emotional Blunting (SEB)[1,19], which was initially developed to characterize negative symptoms in schizophrenia [19,20], has proven to be an effective instrument in assessing the presence of blunting in bvFTD [1,9]. The SEB takes approximately 15-30 minutes to administer. Each behavioral symptom is scored on a 3- point scale where 0 is ‘condition absent’, 1 is ‘slightly present or doubtful’, and 2 is ‘clearly present.’ Items are summed into three domains: absence of pleasure-seeking behavior (Behavior), affective blunting (Affect), and cognitive blunting (Thought). The behavior subscale has seven items (e.g. ‘reclusive, avoids social contact’), whereas the affect subscale has four items (e.g. lacks warmth, empathy). The thought subscale has five items (e.g., lacks plans, ambition, desires, drive). In the initial validation sample, interrater reliability was 0.83, with a reliability coefficient of 0.77 (Kendall's coefficient of concordance) (p < 0.01) [19].

Demographic differences are provided for the MMSE [21] and on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-Q) [22]. Caregiver burden was assessed with the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-22) [23] and caregivers also provided information on Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) for the patients. Group differences were presented on cognitive measures of executive functioning including the Trail Making Test (TMT), Parts A and B [24] and a digit span-task (maximum span forward and backward). For the bvFTD patients, clinical PET scan reports from a variety of scanners were rated for regional hypometabolism as absent, mild, moderate, or severely present (0-3 point scale) for each of left frontal, right frontal, left anterior temporal, and right anterior temporal regions.

Procedure

Data regarding emotional blunting was collected during one of three onsite research visits. The SEB was completed by the neuropsychologist subsequent to a neuropsychological testing session. The neuropsychologist engaged in rapport-building conversation and observed patients' verbal and nonverbal responses to the testing environment. This interview was designed to elicit emotional responses on the 16 items of the SEB and was in accordance with original SEB administration guidelines [19]. The caregivers completed an identical version of the SEB as the rater. The SEB was completed twice by caregivers for two different time points (1) once for before dementiasymptom onset (before-onset), and (2) again for present day functioning (after-onset). The scale items were identical to that completed by the neuropsychologist. It was administered aurally to the caregiver by a research assistant, and the patient was not present during data collection. Clarification of terminology was provided if requested.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20 (IBM Inc.). Independent sample t-tests were computed to assess group differences on demographics (patient and caregiver), FAQ and the NPI. Chi-square test was performed to assess group differences on categorical variables as appropriate. Repeated measures ANOVA compared group differences before dementia-onset and after dementia-onset on SEB caregiver ratings. Repeated measures ANOVA also compared group differences between caregiver and researcher post-dementia-onset SEB ratings.

We computed a difference score between after dementia-onset and before dementia-onset on caregiver SEB ratings. An independent sample t-test assessed the difference score between diagnostic groups. Separate ANCOVAs examined the contribution of caregiver burden and the functional assessment questionnaire (FAQ) score on the caregiver SEB ratings difference scores. A binary logistic regression model investigated before and after dementia-onset difference score as a predictor of the dementia diagnosis. Further ROC analysis determined the optimal cut-off scores. A correlation analysis evaluated the association between regional hypometabolism indicated on PET scans and caregiver SEB difference scores. Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied for correction of multiple comparisons.

Results

Demographics

No significant differences were observed on age, gender, education, or ethnicity of the participants across the two groups. Participants also did not differ on age of disease onset, disease duration, gross cognition (MMSE), or executive functioning (TMT, digit-span task) (See Table 1). No significant differences were observed in the age or gender of the caregivers. The caregivers were primarily spouses (n=27). Non-spouse caregivers (n=4) included two parents, one sibling, and one child of the patient. No significant difference was observed in cohabitation of caregivers with patients across the two groups: 2 bvFTD patients and 1 AD patient did not live with the caregiver. However, the caregivers of the bvFTD group reported significantly higher caregiver burden on ZBI-22 as compared to the caregivers of the AD group (p < 0.05) (See Table 1).

On the FAQ, the bvFTD caregivers reported more impairment in functional activities of their patient, as compared to the AD group (p = 0.002). On the NPI, the bvFTD caregivers reported greater presence of apathy, elation, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior and eating symptoms than the AD caregivers (p < 0.05). In contrast, the AD caregivers reported greater presence of depression in their patients as compared to bvFTD caregivers (p < 0.05) (See Table 2).

Table 2. Neuropsychological characteristics of patients based on NPI-Q.

| bvFTD (n=13) | AD (n=18) | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPI Apathy | 12 (92.3%) | 8 (44.4%) | χ2=7.5; p=.006 |

| NPI Delusions | 2 (15.3%) | 2 (11.1%) | n.s. |

| NPI Hallucination | 2 (15.3%) | 0 | n.s. |

| NPI Agitation | 7 (53.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | n.s. |

| NPI Depression | 2 (15.3%) | 9 (50%) | χ2=3.9; p=.04 |

| NPI Anxiety | 3 (23.0%) | 9 (50%) | n.s. |

| NPI Elation | 6 (46.1%) | 0 | χ2=9.8; p=.002 |

| NPI Disinhibition | 12 (92.3%) | 3 (16.6%) | χ2=17.2; p=.00 |

| NPI Irritation | 5 (38.4%) | 7 (38.8%) | n.s. |

| NPI Aberrant Motor Behavior | 13 (100%) | 5 (27.7%) | χ2=16.1; p=.00 |

| NPI Nighttime behavior | 4 (30.7%) | 5 (27.7%) | n.s. |

| NPI Eating behavior | 13(100%) | 3 (16.6%) | χ2=20.9; p=.00 |

| FAQ | 19.0 (5.1) | 12.0 (6.0) | T(29)=3.3, p=.002` |

Caregiver SEB analysis

The repeated measures ANOVA to assess the effect of diagnosis/group (FTD or AD) on caregiver ratings of total SEB score (before dementia onset vs. post dementia onset) showed a significant group*diagnosis interaction (F(1, 29) = 52.93, p = 0.001). No significant group differences were observed in caregiver rating at the before dementia onset time point, but the bvFTD caregivers reported higher total SEB scores as compared to AD caregivers after dementia-onset as compared to before dementia-onset (p < 0.001) (See Table 3). There were similar results of separate repeated measures ANOVAs for each after-onset subscale score. The caregivers of the bvFTD group reported greater emotional blunting on subscales measuring affect (F(1,29) = 35.21, p = 0.001), behavior (F(1,29) = 32.7, p = 0.001) and thought content (F(1,29) = 67.8, p = 0.001) (See Table 3).

Table 3. “Before Dementia” and “After Dementia” Scores on the Caregiver-Informant Ratings on the Scale for Emotional Blunting (SEB).

| SEB Caregiver | bvFTD Before (n=13) | bvFTD After (n=13) | Diff. score | AD Before (n=18) | AD After (n=18) | Diff. score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2.31 | 23.0 | 20.7 | 2.61 | 6.67 | 4.6 |

| (1.8) | (7.9) | (6.8) | (4.3) | (6.0) | (5.8) | |

|

| ||||||

| Affect | 0.62 | 6.23 | 5.6 | 1.11 | 2.00 | 0.8 |

| (1.0) | (2.7) | (2.7) | (1.9) | (2.2) | (1.7) | |

|

| ||||||

| Behavior- | 1.46 | 10.08 | 8.6 | 1.11 | 3.17 | 2.0 |

| (1.3) | (4.1) | (3.4) | (1.8) | (3.13) | (2.9) | |

|

| ||||||

| Thought | 0.23 | 6.77 | 6.5 | 0.39 | 1.50 | 1.1 |

| (0.4) | (1.7) | (1.6) | (0.6) | (1.79) | (1.9) | |

S.D. in parenthesis

We calculated a SEB difference score by subtracting caregivers' SEB ratings before dementia-onset from those after dementia-onset. A binary logistic regression model examined caregiver SEB difference scores as a predictor of diagnostic group (bvFTD vs. AD). The caregiver SEB difference scores were a significant predictor of diagnostic group (χ2 = 24.39, p = < 0.001 with df = 1) (See Table 4) and correctly classified 90.3 percent of the sample (11 out of 13 bvFTD, and 17 out of 18 AD). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) showed that degree of caregiver burden (ZBI-22) did not predict caregivers’ SEB difference score (F(1,28) = 1.7, p = 0.19).

Table 4. Summary of Binary Logistic Regression Model with Difference in Pre-Post-/Disease Scale of Emotional Blunting Total Score on The Scale for Emotional Blunting Predicting Diagnostic Group in bvFTD (n=11) and AD (n=17).

| B | (SE) | Wald's χ2 | df | p | Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.42 | 1.15 | 8.84 | 1 | .003 | 30.62 |

| SEB Diff. Score | −0.26 | 0.08 | 10.41 | 1 | .001 | 0.77 |

| Test | χ2 | |||||

| Overall Model | 24.39 | 1 | .000 |

Note. Overall Model R2 = .54 (Cox & Snell), .73 (Nagelkerke), -2 Log likelihood = 17.78.

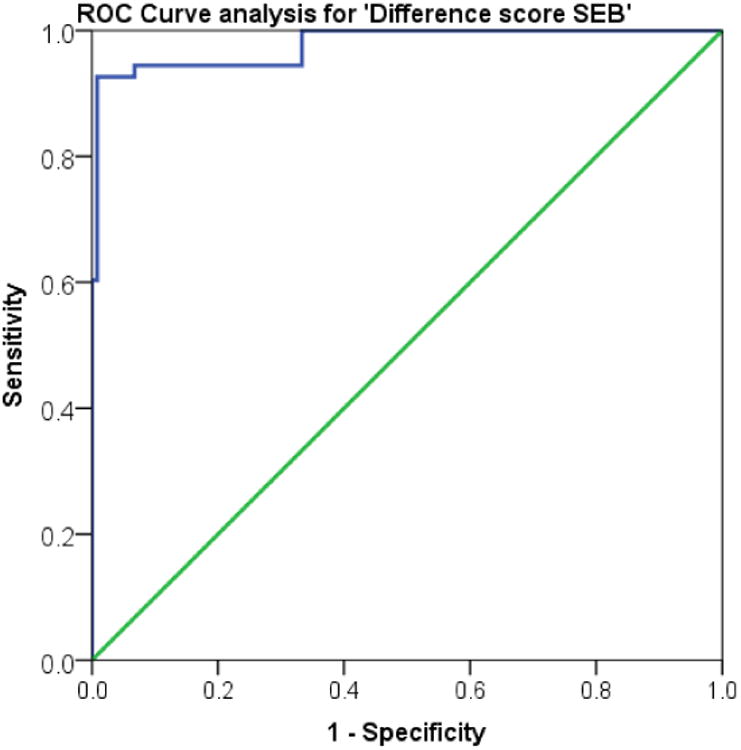

We performed receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analysis in order to obtain optimal cut-off scores. The study plotted the ROC curve (sensitivities vs. false positives [1-specificity]) for the caregiver SEB difference scores and identified potential cut-off scores for distinguishing bvFTD patients from AD patients (AUC = .978, p < 0.001) (see Figure 2). The SEB difference had an optimal cutoff of ≥15 with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 80% for bvFTD compared to AD. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 84.6% and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 94.4%. In this small series, two bvFTD patients and one AD patient would have been misclassified based on the SEB difference score. In comparison, researchers rated six of the FTD patients as mild on the SEB (<12, 12 is optimal cut-off for the researcher SEB), hence resulting in a higher percentage of misclassifications.

Figure 2.

Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) Curve for the difference score on Caregiver Scale for Emotional Blunting (SEB). The figure represents a plot of (sensitivities vs. false positives [1-specificity]) with different cut-off scores.

Correlation analysis

A correlation analysis examined the relationship between caregiver SEB ratings after dementia-onset and the ZBI-22 scores. The ZBI-22 total score had a positive correlation with caregiver SEB Total score (r(31) =.467, p =.008) as well as Affect (r(31) =.461, p = 0.009), Behavior (r(31) =.380, p = 0.035), and Thought content (r(31)= .510, p = 0.003) subscores. Another correlation analysis further validated the association between caregiver SEB ratings after dementia-onset and the NPI items. There was a significantly positive correlation between caregiver SEB ratings after dementia-onset and Elation (r(30) =.546, p = 0.002), Apathy (r(31) =.694, p < 0.01), Disinhibition r(31) =.632, p < 0.01), Aberrant Motor Behavior (r(31) =.605, p < .01) and Eating Behaviors (r(31) =.666, p < 0.01).

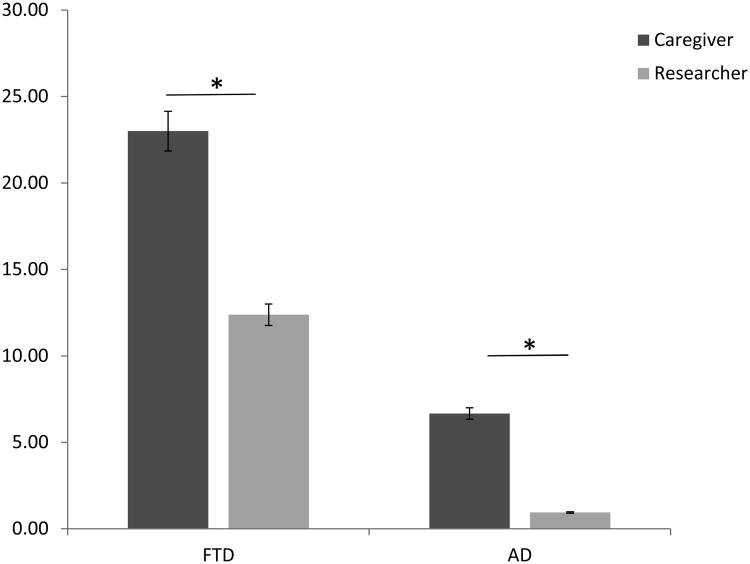

Comparison of Caregiver vs. Investigator SEB Ratings

A repeated measure ANOVA analyzed the effect of rater (researcher or caregiver) on SEB total scores after dementia-onset. There were no significant observer*group interactions. A main effect of observer occurred for the after dementia- onset ratings, i.e., caregiver SEB ratings were higher as compared to researcher SEB ratings (F(1,29) = 26.9, p < 0.01) (See Fig 1). There were similar results when sub- scores were analyzed: Affect (F(1,29) = 24.5, p < 0.01), Behavior (F(1,29) = 22.0, p < 0.01), Thought (F(1,29) = 26.9, p < 0.01) (See Table 5).

Figure 1.

Comparison of SEB score (after dementia-onset) reported by observers.

Table 5. “After Dementia” Scores on the Clinician-Researcher vs. Caregiver-Informant Ratings on Scale of Emotional blunting (SEB).

| SEB | bvFTD – Researcher (n=13) | bvFTD – Caregiver (n=13) | AD – Researcher (n=18) | AD – Caregiver (n=18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12.38 (11.5) | 23.0 (7.9) | 0.94 (0.9) | 6.67 (6.0) |

| Affect | 3.00 (3.21) | 6.23 (2.7) | 0.17(0.5) | 2.00 (2.2) |

| Behavior | 5.46 (5.1) | 10.08 (4.1) | 0.39 (0.6) | 3.17 (3.1) |

| Thought | 3.92 (3.7) | 6.77 (1.7) | 0.28 (0.5) | 1.50 (1.7) |

S.D. in parentheses

PET scan analysis

A correlation analysis investigated the association between caregiver SEB difference ratings and regional hypometabolism on PET scans. There was a significant positive correlation between the SEB difference ratings and both right frontal lobe hypometabolism (r(29) =.536, p = 0.003), left frontal lobe hypometabolism (r(29) =.434, p = 0.01) and a significant negative correlation with right parietal (r(29) = −.558, p = 0.001) and left parietal hypometabolism (r(29) = −.564, p = 0.001). There were no significant correlations with temporal lobe hypometabolism.

Discussion

In this study, dementia caregivers reported more severe changes in emotional blunting among patients with bvFTD compared to those with AD. Both bvFTD and AD groups had similar SEB ratings before dementia onset, and significantly higher SEB ratings after dementia-onset; however, the extent of change was considerably greater among those with bvFTD. In a logistic regression model, the degree of change in emotional blunting was an excellent diagnostic marker that correctly discriminated bvFTD patients from AD patients with 90 percent accuracy. A change score cut-off of ≥15 on the SEB (caregiver rated before and after dementia-onset) provided 92% sensitivity and 80% specificity in distinguishing FTD and AD groups. The current results support prior findings that emotional blunting is a key syndromic feature in bvFTD [10], and that caregiver report of this feature can accurately differentiate individuals with bvFTD versus early-onset AD [1].

In the current study, caregivers from both dementia groups reported higher SEB scores compared to the researcher. In line with recent research, bvFTD caregivers exhibited more severe burden than AD caregivers [25-27], which was positively associated with patient emotional blunting and apathy (NPI) [28]. The greater degree of caregiver burden in bvFTD appears to be related to neuropsychiatric symptoms as well as deficits in adherence to social norms and emotional reciprocity [29,30]. Despite the potential for bvFTD caregiver distress to color the ratings from caregivers, the degree of caregiver burden did not predict emotional blunting scores in the sample, indicating that the caregiver SEB difference ratings were not primarily due to caregiver distress.

There was a significant positive correlation between caregiver SEB difference score (subtracting before dementia-onset from after dementia-onset) and the presence of right and left frontal hypometabolism on PET imaging. Our previous work had noted right frontal hypoperfusion on SPECT imaging in patients with bvFTD patients was associated with apathy and loss of insight [31]. Other investigators have found that bvFTD patients with greater right-sided frontotemporal hypoperfusion on SPECT exhibited greater emotional blunting on the SEB, than those with bilateral or left-sided prominent hypoperfusion [9]. This study supports the association of both right and left frontal metabolism and emotional blunting in bvFTD patients.

There was also a significant negative correlation between caregiver SEB difference score and the presence of right and left parietal hypometabolism. A potential explanation for the association between lower emotional blunting and parietal hypometabolism is dysfunction in frontoparietal networks. Recent studies suggest that frontal and parietal regions work together in a networks that control appraisal and responsiveness to social emotions[32]. It is possible that decreased frontal functions in the presence of maintained parietal functions results in a failure in frontal-parietal control processes for socially-based cognitive, affective and behavioral expression.

The current findings suggest caregivers are uniquely poised to provide an assessment of patients' emotional blunting. Despite the fact that caregiver SEB scores are positively correlated with caregiver burden scale, their distress does not impair their ability to objectively report socioemotional symptoms in a family member. Pathologic emotional expression is most likely to be detected by someone close to the patient who observes them over time and across a variety of settings, whereas clinicians typically assess patients in a relatively brief timeframe and in situations where patients are likely to put their best foot forward. Therefore, caregivers are at a greater advantage in providing an assessment of the patient's behavior.

The study has several potential limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small. Nevertheless, the repeated measures design and other analyses revealed significant group differences on the SEB ratings. The validity of the SEB difference score cut- off needs further assessment with a larger sample size in a future study. Second, the caregivers were primarily spouses. The study did not have professional caregivers, children, siblings or others as primary caregiver; thus the generalizability of these results may be limited. The spouses, however, were the most likely to know the patients well and to most effectively rate their degree of emotional blunting.

The study affirms emotional blunting as a hallmark feature of bvFTD. The structured assessment of this symptom can help aid in the differential diagnosis of bvFTD. Specifically, caregiver-based ratings of emotional blunting are essential in the early detection of bvFTD [33]. Clinicians will improve their accuracy in discriminating neurodegenerative disease by obtaining caregiver before and after dementia-onset ratings on the SEB, similar to other caregiver-based measures[34,35]. SEB scores from both clinician and caregiver ratings in this study can be used for clinical comparison (Table 3). Caregiver report of SEB differences quantifies the level of impairment in emotional reactivity and expression among bvFTD patients and could be used for management and longitudinal follow-up of disease progression.

In conclusion, caregiver reported emotional blunting can help clinicians to differentiate between bvFTD and other dementias during early stages of the disorder. Future work can profitably focus on additional areas of discrepancy between caregiver and clinician rating and evaluate the diagnostic utility of the caregiver perspective.

Acknowledgments

NIA Grant #R01AG034499-04 and the VA GRECC Advanced Fellowship in Geriatrics Award to J. Barsuglia. We acknowledge Dr. Natalie Wolcott for neuropsychological evaluations.

References

- 1.Mendez MF, McMurtray A, Licht E, Shapira JS, Saul RE, Miller BL. The scale for emotional blunting in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase. 2006;12:242–246. doi: 10.1080/13554790600910375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, van Swieten JC, Seelaar H, Dopper EG, Onyike CU, Hillis AE, Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Kertesz A, Seeley WW, Rankin KP, Johnson JK, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen H, Prioleau-Latham CE, Lee A, Kipps CM, Lillo P, Piguet O, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD, Fox NC, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Black SE, Mesulam M, Weintraub S, Dickerson BC, Diehl-Schmid J, Pasquier F, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, Pijnenburg Y, Chow TW, Manes F, Grafman J, Cappa SF, Freedman M, Grossman M, Miller BL. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134:2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurtray AM, Ringman J, Chao SZ, Licht E, Saul RE, Mendez MF. Family history of dementia in early-onset versus very late-onset alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:597–598. doi: 10.1002/gps.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paradiso S, Ostedgaard K, Vaidya J, Ponto LB, Robinson R. Emotional blunting following left basal ganglia stroke: The role of depression and fronto-limbic functional alterations. Psychiatry Res. 2013;211:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietersen CY, Bosker FJ, Doorduin J, Jongsma ME, Postema F, Haas JV, Johnson MP, Koch T, Vladusich T, den Boer JA. An animal model of emotional blunting in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumfor F, Piguet O. Disturbance of emotion processing in frontotemporal dementia: A synthesis of cognitive and neuroimaging findings. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012;22:280–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez MF, Joshi A, Tassniyom K, Teng E, Shapira JS. Clinicopathologic differences among patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2013;80:561–568. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182815547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boone KB, Miller BL, Swartz R, Lu P, Lee A. Relationship between positive and negative symptoms and neuropsychological scores in frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:698–709. doi: 10.1017/S135561770395003X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathias JL, Morphett K. Neurobehavioral differences between alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia: A meta-analysis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:682–698. doi: 10.1080/13803390903427414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherer KR, Clark-Polner E, Mortillaro M. In the eye of the beholder? Universality and cultural specificity in the expression and perception of emotion. Int J Psychol. 2011;46:401–435. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.626049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sollberger M, Neuhaus J, Ketelle R, Stanley CM, Beckman V, Growdon M, Jang J, Miller BL, Rankin KP. Interpersonal traits change as a function of disease type and severity in degenerative brain diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:732–739. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.205047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naglie G, Hogan DB, Krahn M, Black SE, Beattie BL, Patterson C, Macknight C, Freedman M, Borrie M, Byszewski A, Bergman H, Streiner D, Irvine J, Ritvo P, Comrie J, Kowgier M, Tomlinson G. Predictors of family caregiver ratings of patient quality of life in alzheimer disease: Cross-sectional results from the canadian alzheimer's disease quality of life study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:891–901. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182006a7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gifford KA, Liu D, Lu Z, Tripodis Y, Cantwell NG, Palmisano J, Kowall N, Jefferson AL. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pijnenburg YA, Mulder JL, van Swieten JC, Uitdehaag BM, Stevens M, Scheltens P, Jonker C. Diagnostic accuracy of consensus diagnostic criteria for frontotemporal dementia in a memory clinic population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25:157–164. doi: 10.1159/000112852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooten WM, Lyketsos CG. Differentiating Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia: Receiver operator characteristic curve analysis of four rating scales. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9:164–174. doi: 10.1159/000017042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. Mr signal abnormalities at 1.5 t in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the national institute on aging-alzheimer's association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrams R, Taylor MA. A rating scale for emotional blunting. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:226–229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berenbaum SA, Abrams R, Rosenberg S, Taylor MA. The nature of emotional blunting: A factor-analytic study. Psychiatry Res. 1987;20:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(87)90123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein M, Folstein S. Invited reply to “the death knoll for the mmse: Has it outlived its purpose? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;23:158–159. doi: 10.1177/0891988710375213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitan RM, W D. The halstead–reitan neuropsycholgical test battery: Therapy and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychological Press.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mioshi E, Foxe D, Leslie F, Savage S, Hsieh S, Miller L, Hodges JR, Piguet O. The impact of dementia severity on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:68–73. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318247a0bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mioshi E, Bristow M, Cook R, Hodges JR. Factors underlying caregiver stress in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000193626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riedijk SR, De Vugt ME, Duivenvoorden HJ, Niermeijer MF, Van Swieten JC, Verhey FR, Tibben A. Caregiver burden, health-related quality of life and coping in dementia caregivers: A comparison of frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:405–412. doi: 10.1159/000095750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George M. Association between apathy and the caregiver burden in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2013;84:e1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh S, Irish M, Daveson N, Hodges JR, Piguet O. When one loses empathy: Its effect on carers of patients with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0891988713495448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sturm VE, McCarthy ME, Yun I, Madan A, Yuan JW, Holley SR, Ascher EA, Boxer AL, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Mutual gaze in alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal and semantic dementia couples. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6:359–367. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMurtray AM, Chen AK, Shapira JS, Chow TW, Mishkin F, Miller BL, Mendez MF. Variations in regional spect hypoperfusion and clinical features in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66:517–522. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197983.39436.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wessing I, Rehbein MA, Postert C, Furniss T, Junghofer M. The neural basis of cognitive change: Reappraisal of emotional faces modulates neural source activity in a frontoparietal attention network. Neuroimage. 2013;81:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jicha GA. Medical management of frontotemporal dementias: The importance of the caregiver in symptom assessment and guidance of treatment strategies. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45:713–723. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9558-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malloy P, Grace J. A review of rating scales for measuring behavior change due to frontal systems damage. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2005;18:18–27. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000152232.47901.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grace J, Malloy P. Frontal systems behavior scale (frsbe): Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological assessment resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]