Abstract

Objective

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with high rates of depression. This study compared the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to supportive non-directive therapy (SNDT) in treating youth with comorbid IBD and depression.

Method

Depressed youth (51% female; ages 9–17 years; mean age 14.3 years) with Crohn’s disease (n=161) or ulcerative colitis (n=56) were randomly assigned to a 3-month course of CBT or SNDT. The primary outcome was comparative reduction in depressive symptom severity; secondary outcomes were depression remission, increase in depression response, and improved health-related adjustment and IBD activity.

Results

178 participants (82%) completed the 3-month intervention. Both psychotherapies resulted in significant reductions in total Children’s Depression Rating Scale Revised score (37.3% for CBT and 31.9% for SNDT), but the difference between the two treatments was not significant (p=0.16). There were large pre-post effect sizes for each treatment (d=1.31 for CBT and d=1.30 for SNDT). Over 65% of youth had a complete remission of depression at 3 months with no difference between CBT and SNDT (67.8% and 63.2%, respectively). Compared to SNDT, CBT showed a greater reduction in IBD activity (p=0.04) but no greater improvement on the Clinical Global Assessment Scale (p=0.06) and health-related quality of life (the IMPACT-III scale) (p=0.07).

Conclusion

This is the first randomized controlled study to suggest improvements in depression severity, global functioning, quality of life, and disease activity in a physically ill pediatric cohort treated with psychotherapy. Clinical trial registration information—Reducing Depressive Symptoms in Physically Ill Youth; URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT00534911.

Keywords: depression, quality of life, physical illness, psychotherapy, inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Youth with chronic physical illnesses suffer from a disproportionate burden of depression associated with worse medical outcomes and poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL).1,2 With a U.S. prevalence of 71/100,000, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a life-long illness involving episodic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.3,4, The treatment of IBD, which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), often requires immunosuppressive medication and/or surgical resection for severe disease.5

Compared to healthy youth and those with other physical illnesses,6–8 youth with IBD have elevated rates (10–25%) of depression and poorer quality of life.9,10 Findings suggest that depression in pediatric IBD is a heterogeneous condition with etiologically different subtypes (mild–low-grade symptoms, somatic–IBD-related symptoms, and cognitive–cognitive despair symptoms),11 making psychiatric treatment challenging.

While psychotherapies for depression are relatively effective for improving mood and HRQoL in adults with IBD, such treatments are understudied in youth with IBD.12 Studies have shown that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) reduced depressive symptoms and improved functioning in pediatric IBD compared to standard medical treatment.13,14 The CBT used in these studies was Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness (PASCET-PI),15 which is based upon the concept that perceived control and attention to physical illness narrative can mediate the relationship between disease and psychological outcomes.15,16,17 Attention to illness narrative in PASCET-PI was based on adult IBD studies showing that pessimistic illness perceptions were related to poorer psychological adjustment.18,19

This study compared CBT to supportive non-directive therapy (SNDT) in treating depression (primary outcome) and enhancing HRQoL and reducing disease activity (secondary outcomes) in comorbid pediatric IBD and depression after 3 months of treatment. This study explored the change in depression over time in treatment groups. Shown to reduce negative affectivity in other physically illnesses,20 SNDT was chosen to control for the non-specific aspects of psychotherapy (i.e., time and contact with an empathic and skilled therapist).21,22 Although both interventions were hypothesized to reduce depression, improve HRQoL, and diminish IBD activity, it was expected that these effects would be greater in youth receiving PASCET-PI.

METHOD

Participants

Participants with IBD as determined by gastroenterologists using the Porto Criteria,23 ages 9–17 years, were recruited from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and Boston Children’s Hospital. Each site was approved by its institutional review board. Parents provided informed consent, and youth provided assent.

Participants were screened for depression with the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI).24 CDI scores ≥10 on either child or parent rating were considered to be associated with clinically significant depressive symptoms7 and led to assessment with the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Children, Present Version (KSADS-PL) within two weeks.25 Study inclusion required a DSM-IV-TR26 diagnosis of major/minor depression on the KSADS-PL. Exclusion criteria included: 1) lifetime episode of bipolar or psychotic disorder; 2) eating disorder requiring hospitalization during lifetime; 3) suicide attempt within 1 month of assessment; 4) depression requiring psychiatric hospitalization within 3 months of assessment; 5) antidepressant medications within 1 month of baseline assessment; 6) substance abuse by history or iatrogenic opiate use within 1 month of assessment; and 7) current psychotherapy.

Design

Participants (N=217) were randomized to receive a 12-week course of CBT or SNDT. Sample size was based on two-tailed tests of hypotheses with size α=0.05 using a repeated measures design with estimated correlation between the time points of 0.6. Large effect sizes for CBT (Cohen’s d>0.8) were used based on previous CBT trials.14 Small/medium effect sizes for SNDT (Cohen’s d=0.2–0.4) were used. Using our achieved sample size of N=217 and the estimated effects, we computed post hoc power estimates ranging from 91–99%. Participants were assessed with identical measures at baseline and at intervention completion (3 months) by trained and blinded assessors. Data management and statistical analysis occurred in Pittsburgh.

Assessment Instruments

Depression

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) is a 27-item self-report measure that assesses depression symptom severity.24 This well-validated psychometric measure has child and parent versions (CDI-Child and CDI-Parent) and has been used to reliably diagnose depression in those with physical illnesses, including IBD.27–29

Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present Version (K-SADS-PL) is a validated, semi-structured diagnostic interview of youth and parents that assesses the presence of DSM-IV-TR psychiatric disorders.25 Based upon randomly selecting 20% of the youth, inter-rater reliability for depression diagnosis was 0.60 at pre-treatment and 0.70 at 3 months.

Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) is a 17-item validated, semi-structured clinician-rated instrument for depression severity.30 ompleted by blinded evaluators trained in its administration, scores ≤28 indicate remitted depression. The CDRS-R was chosen as the primary emotional outcome because it differentiates depressive from physical symptoms31 and because it is sensitive to treatment effects.15

Health-related Adjustment

IMPACT-III questionnaire is a validated 35-item self-report HRQoL measure for pediatric IBD.32,33 It has the following domains: bowel symptoms, extra-intestinal symptoms, emotional functioning, social functioning, body image, and treatment/interventions. The maximum score is 175, with higher scores associated with better HRQoL.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)34 is a clinician-rated numeric scale used to access psychosocial functioning. The CGAS is stratified by degrees of impairment. A blinded assessor rated degree of functional impairment due to depression and/or IBD activity

Disease Activity

Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) is a well-validated scale used to determine CD activity35 by measuring the following domains: 1) self-report of pain and stool consistency; 2) functional disability; and 3) objective physical/laboratory data (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], hematocrit, albumin, growth, and physical examination). Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) is a validated symptom-based score used for UC activity,36 and is based on self-ratings of abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, stool consistency, stool frequency, presence/absence of nocturnal stooling, and activity level.

PCDAI >30 and PUCAI >35 are consistent with at least moderate disease activity and correlate with gastrointestinal inflammation.35,36 Both measures were rated by a blinded gastroenterologist. Because the PCDAI and PUCAI yield different indices, both measures were separately converted to z-scores to combine them into one disease activity variable.11

Medical history (including IBD onset, presentation, course, and disease location using the Paris classification schema,37 medication use (e.g., steroids, biologics, and/or immunomodulators), surgical history, and ostomy status) was obtained from parents and medical records. Systemic inflammatory biomarkers (C-reactive protein and ESR) were obtained from the medical record by a blinded gastroenterologist. IBD course was divided into acute (diagnosis ≤6 months), chronic (diagnosis >6 months with <1 month in remission defined by inactive PCDAI/PUCAI score), and chronic intermittent (diagnosis >6 months with at least 1 month of remission).

Demographic information was obtained using an information sheet (age, race, gender, household income) and an occupation-based measure.38 Socioeconomic status was defined as household income divided by the number of household individuals.

Interventions

Interventions (up to twelve 45-minute sessions over 3 months) were provided by therapists (n=10) experienced in treating physically ill youth (master’s-level counselors, social workers, psychology interns, psychologists, child psychiatry fellows, and psychiatrists). Each therapist underwent a 3-day training program with the PASCET-PI and SNDT therapy manuals with didactic and practice components as well as an 8-hour PASCET-PI training video. Each therapist received weekly supervision with at least master’s-level therapists expert in the interventions. Each session was audiotaped. The therapist filled out a key skill checklist form for each PASCET-PI session. If key CBT skills were lacking in supervision, therapists were directed to cover missed content during the flexible therapy sessions (9–12).

While key intervention skills remained the same, treatment was tailored to a youth’s individual developmental level. For participants aged 9–13 years receiving CBT, handouts and practice assignments were simplified, pictures were used to illustrate concepts, skills became part of games, and parents were involved after each individual session to review practice assignments. In SNDT, conversations with participants aged 9–13 years were conducted during games, and parents were involved after each session to review their child’s progress. Given the wide geographic areas for participants at each site, >62% of the CBT and >70% of the SNDT sessions were completed by telephone with results similar to other studies evaluating phone therapy for depression.39 Three parent sessions were provided in each therapy; for CBT this was to reinforce skills, and for SNDT it was to listen empathically to parent concerns (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outline of Cognitive Behavioral (CBT) and Supportive (SNDT) Therapy Sessions for Youth and Parents

| PASCET-PI (CBT) | SNDT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Session number | Skill Focus | Session Goals | Session Goals |

| 1 | Activities | Introduce PASCET model; build alliance; explore illness narrative; learn problem-solving approach. | Introduce that therapy is chance for child to talk to empathic expert; explore illness narrative. |

| 2 | Activities – Problem Solving | Choose enjoyed activities and decision-making for problems. | Encourage child to speak; Demonstrate empathic and reflective listening |

| 3 | Calm | Learn relaxation techniques to counter pain and anxiety in social situations and about illness. | Same as above |

| 4 | Confident | Show positive self; improve social skills. | Same as above |

| 5 | Talents | Develop talents and skills. | Same as above |

| 6 | Think positive | Address negative cognition distortions. | Same as above |

| 7 |

Help from friend Identify silver lining No replaying bad thoughts |

Evaluate validity of pessimistic cognitions with others; learn different techniques of positive reframing with less negative counter-thoughts. | Same as above |

| 8 | Keep trying | Develop several cognitive behavioral plans using skills above to address current and future problems. | Same as above |

| 9–12 |

ACT/THINK Review |

Review personalized skills learned. | Same as above |

| Parent 1 |

ACT/THINK Introduce skills |

Understand parent perspective of child’s depression and illness experience; introduce PASCET model. | Understand parent’s perspective of child’s experience. |

| Parent 2 |

ACT Review skills |

Understand parents’ view of child’s progress; review ACT skills and how parents can best reinforce practice. | Same as above |

| Parent 3 |

THINK Review Skills |

Understand parents’ view of child’s progress; review THINK skills and how parents can best reinforce practice. | Same as above |

Note: PASCET-PI = Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training – Physical Illness SNDT= supportive non-directive therapy.

Participants were randomly assigned to CBT or SNDT and balanced with regard to age (9–13 versus 14–17), IBD type (CD versus UC) and depressive severity (minor versus major) using a block design randomization schema. Randomization was completed separately at each site to achieve balance across covariates within each site. The randomization scheme was designed using an adaptive procedure in which the probability of assignment depended on the balance of previous assignments within a strata so that no more than 2 participants could be successively assigned to one treatment.

Illness Narrative Probe

In Session 1 of both interventions, therapists conducted an open-ended, semi-structured interview consisting of 10 questions exploring illness representation and experience. The questions covered domains identified in theoretical illness perception models: 1) identity – the personal label and symptoms as part of participants’ illness; 2) cause–personal ideas about the etiology of their illness; 3) timeline–beliefs on how long their illness will last; 4) consequences – patient-anticipated effects of their illness; and 5) cure/control – perceived recovery from or control over their illness.40 These domains were used as topics in SNDT and as potential problems to target in CBT.

CBT

PASCET-PI14,17 focused on teaching new ways of behaving and thinking by recognizing and challenging automatic negative thoughts, particularly related to IBD symptoms (see Table 1). Weekly practice assignments were focused on behavioral activation and cognitive reframing. Three parent sessions focused on parent coaching and encouraging their children to use the CBT skills.

SNDT

Sessions focused on establishing/maintaining rapport, providing social/emotional support via reflective listening, providing empathy, and encouraging youth to seek out resources for help.21 In contrast to CBT, therapists refrained from teaching specific skills, and there were no inter-session practice assignments. The three parent sessions consisted of listening to parental concerns.

Intervention fidelity

A total of 21% of participants (n=23 per group) were randomly selected and rated by a separate assessor using adherence checklists.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic and clinical measures for the entire cohort and each treatment group. T-tests and chi-square tests were used where appropriate to assess differences in these variables between treatment groups. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences between treatments in treatment responders (≤28 on CDRS-R post-treatment, secondary) and depression remission (defined as no longer meeting KSADS-PL criteria for a depressive diagnosis post-treatment, secondary).

Main analyses were performed using linear mixed models which allowed missing data under the assumption of missing at random. In addition, a completer analysis was performed restricting the analyses to those who completed both time points (n=178), and the results remained similar. No data imputations were performed, and all available data points were used.

Linear mixed-effects models assessed the treatment impact (CBT versus SNDT) on CDRS-R (primary outcome), CGAS, IMPACT-III, and pooled IBD activity (secondary outcomes) over time (baseline to 3 months) in intent-to-treat analyses controlling for site. Change from baseline of these continuous scores was modeled as a function of time and the interaction of treatment and time. Because participants were randomized into each treatment group, baseline scores for each treatment were set to be equal in the model by not including the main effect of treatment. For outcomes with statistically significant baseline group differences, we fit an additional model allowing baseline scores to be different by including the main effect of treatment. Effect sizes for the treatment impact were computed for CDRS-R scores using a pre-post design based on Cohen’s d estimate.

Statistical significance was determined using Wald tests (t-tests) from the linear mixed models using α=.05 (two-sided). All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.41 For secondary depressive outcomes (responder and remission), Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used because the outcomes are related. For the secondary outcomes of health-related adjustment and disease activity, no such correction was made, as these outcomes probe different domains, and because this is a unique study of a comorbid psychiatric-medical cohort, we wanted to retain its heuristic, hypothesis-generating potential by reporting all findings.

RESULTS

Sample and Intervention Characteristics

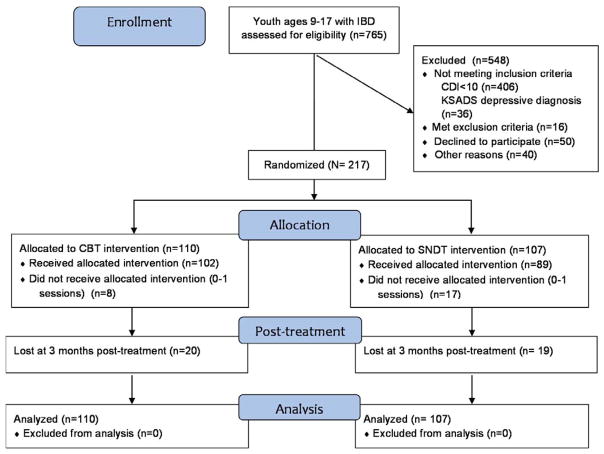

A total of 765 youths were screened with 217 meeting randomization criteria; 161 with CD and 56 with UC (Figure 1 and Table 2). At baseline, one potential participant was excluded for severe depression, and 6 for being on antidepressants. The treatment groups were significantly different only for Caucasian race (CBT 94.6%; SNDT 84.1%), surgical resection rate (CBT 5.6%; SNDT 14.2%), and raw mean baseline CDRS-R scores (CBT 45.1; SNDT 48.9). There were no significant differences in levels of medical adherence at baseline (Total 88%: CBT 92%; SNDT 85%).

Figure 1.

Recruitment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for randomized efficacy trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and supportive non-directive therapy (SNDT) for depression. Note: CDI = Child Depression Inventory; KSADS = Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Children.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Youth With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Depression by Psychotherapy Type

| Measure | CBT (n=110) | SNDT (n=107) | Test Statistic (p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | ||

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age | -- | 14.3 (2.5) | -- | 14.3 (2.3) | t=−0.16 (0.87) |

|

| |||||

| Gender (Male) | 54 (49.1) | -- | 48 (44.9) | -- | χ2=0.39 (0.53) |

|

| |||||

| Site (Pittsburgh) | 65 (59.1) | -- | 65 (60.8) | -- | χ2=0.06 (0.80) |

|

| |||||

| Race (White) | 104 (94.6) | -- | 90 (84.1) | -- | χ2=6.23 (0.01)a |

|

| |||||

| SES | -- | 1.3 (0.6) | -- | 1.1 (0.6) | t=1.42 (0.16) |

|

| |||||

| Depression | |||||

|

| |||||

| CDI Child | -- | 12.7 (6.3) | -- | 13.8 (6.7) | t=−1.21 (0.23) |

|

| |||||

| CDI Parent | -- | 14.0 (6.1) | -- | 14.8 (7.3) | t=−0.84 (0.40) |

|

| |||||

| CDRS-R | -- | 45.1 (12.1) | -- | 48.9 (12.8) | t=−2.26 (0.02)a |

|

| |||||

| Major Depression (versus Minor Depression) | 68 (61.8) | -- | 69 (64.5) | -- | χ2=0.17 (0.68) |

|

| |||||

| Health-related Adjustment | |||||

|

| |||||

| CGAS | -- | 58.6 (4.8) | -- | 58.8 (4.6) | t=−0.22 (0.83) |

|

| |||||

| IMPACT-IIIb | -- | 118.9 (20.8) | -- | 113.7 (22.9) | t=1.57 (0.12) |

|

| |||||

| Disease Activity | |||||

|

| |||||

| Months since IBD diagnosis (between diagnosis & screen) | -- | 22.8 (30.4) | -- | 23.7 (28.5) | t=−0.23 (0.82) |

|

| |||||

| PUCAI (ulcerative colitis) | 27 | 23.3 (24.9) | 26 | 25.8 (23.8) | t=−0.36 (0.72) |

|

| |||||

| PCDAI (Crohn’s disease) | 79 | 21.0 (16.2) | 74 | 22.4 (16.9) | t=−0.53 (0.60) |

|

| |||||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | -- | 21.9 (16.1) | -- | 24.3 (19.0) | t=−0.93 (0.35) |

|

| |||||

| C-reactive protein | -- | 1.4 (2.8) | -- | 1.4 (2.1) | t=0.13 (0.90) |

|

| |||||

| IBD Medications | |||||

| Systemic steroids | 27 (24.6) | -- | 28 (26.2) | -- | χ2=0.08 (0.78) |

| Biologics | 27 (24.6) | 34 (31.8) | χ2=1.40 (0.24) | ||

| Immunomodulators | 52 (47.3) | 51 (47.7) | χ2=0.003 (0.95) | ||

|

| |||||

| Surgery (yes versus no) | 6 (5.6) | -- | 15 (14.2) | -- | χ2=4.47 (0.04)a |

|

| |||||

| Ostomy (yes versus no) | 2(1.8) | -- | 6(5.6) | -- | χ2=2.15 (0.14) |

Note: Demographic information is given by portion of whole, where gender is broken down by male and female, site by Pittsburgh v. Boston, and race by white v. black. CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; PCDAI = Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; PUCAI = Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; SES = socioeconomic status; SNDT = supportive non-directive therapy.

Indicates statistical significance.

IMPACT-III is a health-related quality of life assessment.

DSM-IV-TR psychiatric comorbidities included: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; 21.7%), specific phobia (15.2%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 11.6%), separation anxiety (SAD; 9.7%), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD; 8.9%), social anxiety (8.8%), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; 1.9%), dysthymia (1.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 1.4%), anorexia nervosa (0.9%), panic (0.5%), and conduct disorder (0.5%). There were no significant differences in comorbid diagnoses between treatment groups.

There were no significant differences between therapy arms in mean number of individual sessions (CBT 9.1; SNDT 8.6), mean individual treatment minutes (CBT 374.1; SNDT 331.4), mean parent treatment minutes (CBT 93; SNDT 72), and mean percentage of phone sessions (CBT 62.8; SNDT 70.4). Though not significantly different, at least 6 sessions were completed by 91% of the CBT group compared to 74% of the SNDT.

For CBT, the percentage of participants where core CBT skills covered ranged from 70% – 100%. For SNDT, the percentage of participants with CBT skill contamination was <6%. SNDT was rated highly (>50% of participants) for the following content/processes: discusses physical/health symptoms (74%); encourages to talk (74%); clarifies or restates communication (89%); is sensitive to feeling (99%); and asks for information (99%). Together, these results demonstrate adequate fidelity.

Intervention Effects on Depression, Health-related Adjustment and Disease Activity

As the primary aim, CDRS-R improved over time in both treatment groups with no statistical differences (raw means at month 3 were 29.11 for CBT mean 29.11 versus SNDT mean 32.18) (Table 3). Because there were baseline differences with CDRS-R, we fit an additional model allowing the baseline scores for treatment group to be different, and results were similar to the original analysis. There were large pre-post effect sizes for each treatment over time (d=1.31 for CBT and d=1.30 for SNDT).

Table 3.

Results of the Linear Mixed Models: Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Versus Supportive Therapy Over Time for Depression Severity, Psychosocial Functioning, Quality of Life and Disease Activity in Youth With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Depression

| Outcome | N | Treatment effect coefficient (β) | 95% CI | Test Statistic (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | ||||

|

Depression severity CDRS-R |

217 | 2.55 | 0.96, 6.06 | z =1.42 (.16) |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

|

Psychosocial functioning CGAS |

217 | −1.46 | −2.96, 0.04 | z = −1.90 (.06) |

|

IBD Quality of Life IMPACT-IIIa |

184 | −6.42 | −13.28, 0.45 | z = −1.83 (.07) |

|

IBD Activity PCDAI/PUCAI (Pooled activity Z scores |

210 | 0.31 | 0.008, 0.62 | z = 2.01 (.04)b |

Note: CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; PCDAI = Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; PUCAI = Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; SNDT = supportive non-directive therapy.

IMPACT-III is a health-related quality of life assessment.

Indicates statistical significance CBT>SNDT

For secondary analyses, at 3-month, 50.3% (n=178) were found to have CDRS-R scores ≤ 28. Those who received CBT had a non-significant higher percentage of treatment response (53.5% versus 47.1%) and showed a 29% increased odds of response (OR=1.29, 95% CI=0.71–2.36) compared to SNDT. At 3-month, 65.5% of the total sample (N=217) no longer met DSM-IV-TR criteria for depression. There was no significant difference in remission rates between therapies (CBT 67.7% versus SNDT 63.2%). The CBT group had a non-significant 22% increased odds (OR=1.22, 95% CI=0.66–2.28) of remitting compared to SNDT. In comparing those whose depression remitted versus those who did not remit, there were greater percentages of youth with social anxiety (p=.03) and dysthymia (p=.04) in those whose depression did not remit. Those with non-remitting depression also had more IBD activity at 3 months (p=.02).

Although both therapies demonstrated improvement in HRQoL and psychosocial functioning at 3months, there were no significant differences between treatments (Table 3). Mean IMPACT-III scores (CBT 142.52 versus SNDT 133.85) were consistent with a moderately good quality of life. Mean CGAS scores (CBT 65.82 versus SNDT 64.30) were consistent with minimal impairment. Controlling for surgery and race had no significant impact.

IBD activity improved over time in both treatment groups (raw means [SD] at baseline to month 3: PCDAI = CBT 21.0 [16.2] to 9.49 [2.48] and SNDT 25.8 [3.8] to 15.30 [12.11] and PUCAI = CBT 23.3 [24.9] to 11.39 [12.7] and SNDT 22.4 [16.9] to 11.47 [16.56]). Pooled PCDAI and PUCAI z-scores showed a statistically significant difference in reducing disease activity favoring CBT over time (Table 3, p=0.04).

DISCUSSION

This study represents the largest randomized controlled trial of two psychotherapy interventions for youth with comorbid IBD and depression. Both the CBT and SNDT were associated with reduced depression severity, improved health-related adjustment, and lessened IBD activity over time. In comparing PASCET-PI to SNDT, there were no significant differences between treatments in the primary outcome, depressive severity, and in the secondary outcomes, only the difference in reduction of IBD activity reached significance, favoring CBT.

While it is possible that the improvements in the primary and secondary outcomes measures for each intervention might have been related to passage of time,42 this seems unlikely given our previous randomized trial showing that CBT was better than treatment as usual in improving depression and functioning in subsyndromal adolescent depression.14 SNDT is a recognized active therapy for childhood depression as evidenced by improvement in depression and suicidality, and in some circumstances (e.g., history of abuse), it has been found to be more efficacious than CBT.21,43 We cannot rule out factors common to both therapies (e.g., empathic attention, social support, probing the illness narrative, and family component) as contributing to the improvements. Having the same therapists providing both therapies is both a methodological strength in that there is control for a large number of therapist characteristics that could impact outcomes as well as a potential limitation, as using the same therapists for both interventions may reduce treatment differences. Fidelity rating showed good fidelity for CBT and little therapist drift toward CBT in the SNDT group. In the context of the long-standing controversy in psychotherapy research between those who believe psychotherapy works through the influence of specific theory-linked skills44 and those who believe therapy works through “common factors,”45,46 our findings suggest that the specific modality-linked skills may be less important for the improvement of overall depression.

In secondary analyses of depression, almost 66% of our sample achieved remission of their depression, with 78.4% having <3 residual depressive symptoms. These rates are higher than those seen in treatment of physically healthy youth with depression.47 Certainly, the higher remission rates in our study may be explained by many factors including less severe depression, lower comorbidity, higher treatment adherence, and/or strong support from the gastroenterologists. Yet, in another comparison of CBT and supportive therapy in adolescent depression without physical illness, a 64% CBT remission rate versus only 39% for supportive therapy was found.21 Both PASCET-PI and SNDT had large pre-post effect sizes (d=1.3), which are comparable to those calculated to this adolescent depression psychotherapy trial (d=1.68 for CBT and 1.58 for supportive therapy).21 Together, these findings provide further support for premise that both CBT and SNDT were beneficial.

While both therapies had a favorable impact on disease activity, CBT had a more favorable impact than SNDT. Baseline adherence with IBD medications was high and thus unlikely to be a reason for improved IBD activity. Given a mean 2-year IBD duration combined with participants’ improved HRQoL and psychosocial functioning, the findings are commensurate with reduced depression after psychotherapy, suggesting these treatments provided additional benefit over and above standard medical treatment. Psychosocial interventions may enhance the brain’s capacity to regulate immune response in patients with IBD.48 In this context, it is possible that for illness-specific processes (e.g., systemic inflammation), a more specific psychotherapy skill modality (e.g., CBT) may prove more helpful. However, these preliminary findings should be interpreted cautiously given the pooling of IBD subtypes to measure disease activity, the significant number of participants with mild illness ratings, and the possibility of type I error without correcting for multiple comparisons.

It is possible that factors that were significantly different between the two groups (more minorities, depression severity differences, and higher surgery rates were found in those treated with SNDT) may have influenced outcomes. Depression is frequently considered a heterogeneous condition with different subtypes and unique etiologies. The presence of different depressive symptom clusters may have further confounded the unique therapeutic effects of CBT versus SNDT.11 Finally, while CD and UC are subtypes of IBD, they have different pathogeneses and thus may be affected differently by psychotherapy,3 as other treatments such as systemic steroids have differential behavioral and cognitive effects in youth with CD versus UC.49 It will be important to explore the effects of psychotherapy in more homogeneous subsets of youth in order to better understand mechanisms that underlie effective psychotherapy in these illnesses.

Unfortunately, one-third of the youth continued to have persistent depressive illness despite psychotherapy, suggesting a need for alternative treatments. This subset had higher rates of social anxiety (n=8 versus n=5) and dysthymia (n=3 versus n=0) and more IBD activity at 3 months compared to those who achieved remission of depression, suggesting these three conditions may be treatment moderators. As there are no randomized controlled trials of antidepressants in youth experiencing both IBD and depression,50,51 future studies are needed to investigate the potential benefits and risks of psychotropic medication when added to the medical treatment.

Major strengths of this study are being the largest randomized treatment trial and showing that two different types of psychotherapy may be useful in treating depression in youth with high morbidity chronic physical disease such as IBD. Potential study limitations include possible selection bias by recruiting participants with only mild to moderate depression. However, only 7 participants were excluded due to more severe depression (with 6 of these being on antidepressants), thus any bias appears slight. While our results would be strengthened by analyses of possible moderators (e.g., age, IBD type), the study was not designed to accomplish this goal. The relatively short follow-up period represents another potential limitation. While over 50% of the sessions were conducted by phone in both groups, possibly improving treatment adherence, we did not design the study to compare their efficacy.

Depression in those with chronic physical illness is a significant public health problem that is common, disrupts normal development, and causes substantial functional impairment. This study provides evidence that active psychotherapy may be a useful adjunct to medical treatment in youth with IBD during a developmental period in which patients are early in the course of a life-long illness and vulnerable to increased psychopathology. It underscores the importance of integrating behavioral health strategies directly into pediatric medical homes. Our findings in IBD may be applicable to youth struggling with depression in other chronic illnesses and thus may offer significant promise for a better quality of life for physically ill youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) through grants R01 MH077770, and NCT00534911.

Drs. Youk and Fairclough served as the statistical experts for this research.

The authors thank F. Nicole McCarthy, BA, and David Rizzo, LCSW, from University of Pittsburgh, and Jennifer Holland, BA, from Harvard University for their support as research specialists. Both psychotherapy treatment manuals are available from Dr. Szigethy, from University of Pittsburgh.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Szigethy has received research grant funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, has served as a consultant for Merck Advisory Board, has received an honorarium from the Gastrointestinal Health Foundation to develop a CME supplement for the American Journal of Gastroenterology on Narcotic Bowel Syndrome, and is coeditor of the book Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents, from APPI Press. Dr. Weisz is coeditor of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents. Dr. Fairclough has received 5% salary support from Biogen for an investigator innovative grant in Multiple Sclerosis patients. Dr. Gonzalez-Heydrich has received grant support from the Tommy Fuss Fund, the Al Rashed Family, Glaxo-SmithKline, and Johnson and Johnson. He has served as a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer Inc., Johnson and Johnson (Janssen, McNeil Consumer Health), Novartis, Parke-Davis, Glaxo-SmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Seaside Therapeutics. He has been a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer Inc., Novartis, and Bristol-Meyers Squibb. He has received grant support from Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer Inc., Johnson and Johnson (Janssen, McNeil Consumer Health), Akzo-Nobel/Organon, and the NIMH. Dr. Kupfer has served as consultant to the American Psychiatric Association (as Chair of the DSM-5 Task Force), has held joint ownership of copyright for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), has received an honorarium for manuscript submission to Medicographia (Servier), has been a stockholder in AliphCom and Psychiatric Assessments, Inc., and a member of the Advisory Board of Servier International. Drs. Bujoreanu, Youk, Benhayon, Keljo, Srinath, Bousvaros, DeMaso and Mr. Ducharme, and Mss. Kirshner and Newara report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Eva Szigethy, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Simona I. Bujoreanu, Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Ada O. Youk, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. John Weisz, Harvard University.

Dr. David Benhayon, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Diane Fairclough, Colorado School of Public Health.

Mr. Peter Ducharme, Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Joseph Gonzalez-Heydrich, Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. David Keljo, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Arvind Srinath, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Athos Bousvaros, Boston Children’s Hospital.

Ms. Margaret Kirshner, University of Pittsburgh.

Ms. Melissa Newara, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. David Kupfer, University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. David R. DeMaso, Boston Children’s Hospital.

References

- 1.Blackman JA, Conaway MR. Developmental, emotional and behavioral co-morbidities across the chronic health condition spectrum. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2013 Jan 1;6(2):63–71. doi: 10.3233/PRM-130240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhoof E, Maurice-Stam H, Heymans H, Grootenhuis M. Health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression in young adults with disability benefits due to childhood-onset somatic conditions. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regueiro MD, Swoger JM. Clinical Challenges and Complications of IBD. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007 Dec;5(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michail S, Ramsy M, Soliman E. Advances in inflammatory bowel diseases in children. Minerva Pediatr. 2012 Jun;64(3):257–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke P, Meyer V, Kocoshis S, et al. Depression and anxiety in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and cystic fibrosis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;28(6):948–951. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szigethy E, Levy-Warren A, Whitton S, et al. Depressive symptoms and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2004 Oct;39(4):395–403. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenley RN, Hommel KA, Nebel J, et al. A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2010 Sep;35(8):857–869. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Disease activity, behavioral dysfunction, and health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011 Jul;17(7):1581–1586. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan JL, Mellon MW, Junger KW, et al. The clinical utility of health-related quality of life screening in a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease clinic. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2013 Nov;19(12):2666–2672. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182a82b15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szigethy EM, Youk AO, Benhayon D, et al. Depression Subtypes in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013 Dec 16; doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The Efficacy and Methodological Challenges of Psychotherapy for Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2013 Jul 10; doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318296ae5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szigethy E, Whitton SW, Levy-Warren A, DeMaso DR, Weisz J, Beardslee WR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004 Dec;43(12):1469–1477. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142284.10574.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szigethy E, Kenney E, Carpenter J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;46(10):1290–1298. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6341f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisz JR, Thurber CA, Sweeney L, Proffitt VD, LeGagnoux GL. Brief treatment of mild-to-moderate child depression using primary and secondary control enhancement training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997 Aug;65(4):703–707. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisz JR, Francis SE, Bearman SK. Assessing secondary control and its association with youth depression symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010 Oct;38(7):883–893. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9440-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szigethy E, Thompson R, Turner S, Delaney P, Beardslee W, JRW . Cognitive behavioral therapy for general medical conditions. In: ES, Weisz JR, Findling RL, editors. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012. pp. 331–382. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles SR, Wilson JL, Connell WR, Kamm MA. Preliminary examination of the relations between disease activity, illness perceptions, coping strategies, and psychological morbidity in Crohn’s disease guided by the common sense model of illness. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011 Dec;17(12):2551–2557. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorrian A, Dempster M, Adair P. Adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease: the relative influence of illness perceptions and coping. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009 Jan;15(1):47–55. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahler OJ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Apr;73(2):272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of general psychiatry. 1997 Sep;54(9):877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luborsky L, McLellan AT, Woody GE, O’Brien CP, Auerbach A. Therapist success and its determinants. Archives of general psychiatry. 1985 Jun;42(6):602–611. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290084010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis--the Porto criteria. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005 Jul;41(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000163736.30261.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997 Jul;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on D-I. . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson RD, Craig AE, Mrakotsky C, Bousvaros A, Demaso DR, Szigethy E. Using the Children’s Depression Inventory in youth with inflammatory bowel disease: support for a physical illness-related factor. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(8):1194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannakopoulos G, Kazantzi M, Dimitrakaki C, Tsiantis J, Kolaitis G, Tountas Y. Screening for children’s depression symptoms in Greece: the use of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a nation-wide school-based sample. European child & adolescent psychiatry. 2009 Aug;18(8):485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji L, Lili S, Jing W, et al. Appearance concern and depression in adolescent girls with systemic lupus erythematous. Clinical rheumatology. 2012 Dec;31(12):1671–1675. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) Manual. Los Angeles: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison KM, Goli A, Van Wagoner J, Brown ES, Khan DA. Depressive Symptoms in Inner-City Children With Asthma. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;4(5):174–177. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otley A, Smith C, Nicholas D, et al. The IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2002 Oct;35(4):557–563. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths AM, Nicholas D, Smith C, et al. Development of a quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: dealing with differences related to age and IBD type. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1999 Apr;28(4):S46–52. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Archives of general psychiatry. 1983 Nov;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loonen HJ, Griffiths AM, Merkus MP, Derkx HH. A critical assessment of items on the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2003 Jan;36(1):90–95. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007 Aug;133(2):423–432. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011 Jun;17(6):1314–1321. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakao K. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores (General Social Survey Methodological Report No 74) Chicago University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang PS, Simon GE, Avorn J, et al. Telephone screening, outreach, and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007 Sep 26;298(12):1401–1411. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumann LJ, Cameron LD, Zimmerman RS, Leventhal H. Illness representations and matching labels with symptoms. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1989;8(4):449–469. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 [computer program] College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otley AR, Griffiths AM, Hale S, et al. Health-related quality of life in the first year after a diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006 Aug;12(8):684–691. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barbe RP, Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Kolko DJ, Brent DA. Lifetime history of sexual abuse, clinical presentation, and outcome in a clinical trial for adolescent depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2004 Jan;65(1):77–83. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeRubeis RJ, Brotman MA, Gibbons CJ. A conceptual and methodological analysis of the nonspecifics argument. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:174–183. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wampold BE. Establishing specificity in psychotherapy scientifically: Design and evidence issues. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2005;C12:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich F, Benson K, Ahn H-N. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “all must have prizes”. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, et al. Remission and Residual Symptoms After Short-Term Treatment in the Treatment of Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1404–1411. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242228.75516.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144(1):36–49. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mrakotsky C, Forbes PW, Bernstein JH, et al. Acute cognitive and behavioral effects of systemic corticosteroids in children treated for inflammatory bowel disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013 Jan;19(1):96–109. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mikocka-Walus AA, Gordon AL, Stewart BJ, Andrews JM. The role of antidepressants in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a short report on a clinical case-note audit. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2012 Feb;72(2):165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goodhand JR, Greig FI, Koodun Y, et al. Do antidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? A retrospective case-matched observational study. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012 Jul;18(7):1232–1239. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]